Mini-Abstract:Among board-certified surgeons, we measured associations between participation in ≥1 year of research during general-surgery residency and each of full-time academic-medicine faculty appointment and federal-research award. In multivariable logistic regression models, research participation predicted a greater likelihood of faculty appointment (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.790) and federal-research award (AOR 4.596).

Abstract

Objective:

We examined associations between participation in ≥1 year of research during general surgery residency and each of full-time academic-medicine faculty appointment and mentored-K and/or Research Project Grant (RPG, including R01 and other) awards.

Summary Background Data:

Many surgeons participate in ≥1 year of research during residency; however, the relationship between such dedicated research during general surgery residency and surgeons’ career paths has not been investigated in a national study.

Methods:

We analyzed de-identified data through August 2014 from the Association of American Medical Colleges, American Board of Medical Specialties, and the National Institutes of Health Information for Management, Planning, Analysis, and Coordination II grants database for 1997–2004 US medical-school graduates who completed ≥5 years of general surgery graduate medical education (GME) and became board-certified surgeons. Using multivariable logistic regression models, we identified independent predictors of faculty appointment and K/RPG award, reporting adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) significant at P <.05.

Results:

Of 5,328 board-certified surgeons, there were 1,848 (34.7%) GME-research participants, 1,658 (31.1%) faculty appointees, and 58 (1.1%) K/RPG awardees. Controlling for sex, debt, MD/PhD graduation, and other variables, GME-research participants were more likely to have received faculty appointments (AOR 1.790; 95% CI 1.573–2.037) and federal K/RPG awards (AOR 4.596; 95% CI 2.355–8.969).

Conclusions:

Nationally, general surgery GME-research participation was independently associated with faculty appointment and K/RPG award receipt. These findings serve as benchmarks for general surgery residency programs aiming to prepare trainees for careers as academicians and surgeon-scientists.

INTRODUCTION

Graduate medical education (GME) residency programs may offer opportunities for their trainees to participate in one or more years of dedicated research during residency. According to results of a national survey of general surgery program directors in 2006, 36% of general surgery residents participated in ≥1 year of dedicated research during general surgery training.1 Single-institutional follow-up studies of general surgery training-program graduates’ career paths have been conducted by several university programs in which most residents had participated in dedicated research year(s), with follow-up survey data obtained from surgeons after training-program completion.2–4 In these three studies, program-specific proportions of survey respondents who had participated in ≥1 year of dedicated research during general surgery GME ranged from 72–99% and about 40–65% of survey respondents had pursued academic-medicine careers.2–4 However, there have been no national studies comparing characteristics and career paths of general surgery trainees who had and had not participated in ≥1 year of dedicated research during residency. We therefore conducted a retrospective, national study to identify variables associated with participation in ≥1 year of dedicated research during general surgery residency among US Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)-accredited medical-school graduates who had completed at least 5 years of general surgery training and became board-certified by one or more of the following American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS)-member boards: American Board of Surgery (ABS), American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) and American Board of Thoracic Surgery (ABTS). We examined the relationship between ≥1 year of dedicated research during general surgery residency and each of full-time academic-medicine faculty appointment and federal mentored, career-development awards (K01, K08 and K23) and/or Research Project Grants (RPGs) among these board-certified surgeons.

METHODS

Our database included individual, de-identified records for the cohort of US LCME-accredited medical-school matriculants in academic years 1993–1994 through 2000–2001, including 119,906 graduates in calendar years 1997–2004, with follow-up through August 2014. Washington University School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board approved this study as non-human subjects research. Based on the literature,1,3–12 we included several variables potentially associated with our outcomes of interest.

Measures

In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) provided us with de-identified data from various sources, including the AAMC’s Student Records System,13 Graduation Questionnaire,14 GME Track,15 and Faculty Roster,16 the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile,17 and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Information for Management, Planning, Analysis, and Coordination (IMPAC) II federal grants database.

Student Records System variables included graduation year, degree program at graduation (categorized as MD/PhD vs. all other MD), sex and race/ethnicity; we created a 4-category race/ethnicity variable for analysis, including Asian/Pacific Islander, underrepresented minorities in medicine (URM; including, Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native), other/unknown (including “Other” or none reported), and white.

From the Graduation Questionnaire, we created a 4-category variable for total debt at graduation (No debt, $1–$99,999, ≥$100,000, and “missing”), and a 3-category variable for career intention at graduation (“research-related careers” [including full-time faculty research/teaching and non-university research scientist], “non-research-related careers” [including clinical practice, other, and undecided], and “missing”). The category “missing” for these two variables included individuals who completed at least part of the Graduation Questionnaire but did not respond to this item or who did not respond to the Graduation Questionnaire.

The AAMC provided first-attempt United States Medical Licensing Examination Step l scores, used with permission from the National Board of Medical Examiners. We included Step 1 scores because many general surgery program directors use this measure in selecting program applicants to interview and to rank,18 although such use is considered secondary to its purpose. Step l score is associated with US medical students’ success in gaining entry into their preferred GME programs,19,20 faculty appointment,10,11 and each of federal F32 post-doctoral research fellowship, mentored-K (K01/K08/K23), and R01 awards among graduates.9

Using AAMC GME Track data,15 we created a dichotomous variable (yes vs. no) for graduates who initially entered and remained in general surgery training for ≥5 years after graduation. We created a dichotomous variable (yes vs. no) for completion of ≥1 year of dedicated research during the first 5 years of general surgery residency (“GME-research participation”), as reported by each program director on the National GME Census for residents named in their general surgery programs.

ABMS-member-board certification records were provided to the AAMC by Medical Marketing Services (MMS) Inc., a licensed AMA Physician Masterfile vendor, for our research through a data-licensing agreement with the ABMS. We included individuals in our study certified by one or more of the ABS, ABPS, and ABTS (referred to hereafter as “board-certified surgeons”). Using AAMC Faculty Roster data, we created a dichotomous variable (yes vs. no) for medical-school graduates who had subsequently received a full-time academic-medicine faculty appointment in a US LCME-accredited medical school (referred to hereafter as “faculty appointees”).

Publicly available NIH IMPAC II data were obtained for all active and inactive federal records of individual research grants awarded to graduates in our cohort. The NIH and AAMC contracted with Net ESolutions Corporation in Bethesda, Maryland to conduct the record match on our behalf. Multiple identifiers shared between the AAMC and the NIH (e.g., name, sex, medical school, graduation year, and 2–3 unique identifiers) were used to minimize the possibility of false-positive record matches.21 The AAMC provided us with the de-identified, linked data. We created dichotomous variables (yes vs. no) for F32 post-doctoral research fellowship, mentored-K (K01/K08/K23), and RPG awards, including R01s and other RPGs received after medical-school graduation.

Statistical analysis

We used chi-square tests to describe associations among categorical variables and analysis of variance to describe between-groups differences in continuous variables by GME-research participation, full-time faculty appointment, and mentored-K and RPG awards. Using multivariable logistic regression models, we identified independent predictors of each outcome of interest and report adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each predictor.

RESULTS

Of all 1993–1994 to 2000–2001 matriculants in our database, 119,906 graduated in calendar years 1997–2004, including 5,336 who entered and completed ≥5 years of general surgery residency training and subsequently became board-certified surgeons. Of these 5,336 surgeons, all but 8 missing data for sex were included in our final sample of 5,328 surgeons (ABS-certified only: 4,518 [84.8%]; ABS- and ABTS-certified: 383 [7.2%]; ABS- and ABPS-certified: 260 [4.9%]; ABPS-certified only: 106 [2.0%]; ABTS-certified only: 61 [1.1%]).

Of these 5,328 surgeons, 1,848 (34.7%) participated in ≥1 year of GME research, 1,658 (31.1%) were faculty appointees, 86 (1.6%) received F32 awards, and 58 (1.1%) received mentored-K and/or RPG awards (36 mentored-K, 18 RPG, and 4 both). Due to the small numbers of mentored-K and RPG awards, we created a dichotomous variable (yes vs. no) for receipt of any mentored-K and/or RPG (K/RPG) award.

Among all 119,906 medical-school graduates in calendar years 1997–2004 in our larger database, there were 521 (0.4%) F32 awardees, including 86 (1.6%) of the 5,328 surgeons in our sample and 435 (0.4%) of the 114,578 graduates excluded, and there were 2,368 (2.0%) K/RPG awardees, including 58 (1.1%) of the 5,328 surgeons in our sample and 2,310 (2.0%) of the 114,578 graduates excluded (chi-square for each comparison, P < 0.001).

Table 1 shows our study sample characteristics, grouped by GME-research participation, faculty appointment and K/RPG award. In bivariate analyses, surgeons who were Asian/Pacific Islander, indicated research-related career intentions at graduation, were F32 awardees, and had higher Step l scores were significantly over-represented among GME-research participants. Surgeons who were women, Asian/Pacific Islander, graduated from medical school in earlier years, were MD/PhD graduates, indicated research-related career intentions at graduation, reported no debt, had higher Step l scores, were GME-research participants, and were F32 awardees were significantly over-represented among faculty appointees. Surgeons who had graduated from medical school in earlier years, were MD/PhD graduates, indicated research-related career intentions at graduation, had higher Step 1 scores, were GME-research participants, and were F32 awardees were significantly over-represented among K/RPG awardees.

Table 1.

Characteristics of board-certified surgeons who had graduated from LCME-accredited US medical schools in 1997–2004 grouped by each of ≥1 year GME research, full-time faculty appointment and federal mentored-K and/or RPG award receipt (N = 5328).a

| Total N = 5328b | ≥1 year GME research n = 1848b | No GME research, n = 3480b | P-value | Full-time faculty appointment n = 1658b | No full-time faculty appointmentn = 3670b | P-value | K/RPG award n = 58b | No K/RPG award n = 5270b | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .478 | .014 | .965 | |||||||

| Men | 3872 (72.7) | 1332 (72.1) | 2540 (73.0) | 1168 (70.4) | 2704 (73.7) | 42 (72.4) | 3830 (72.7) | |||

| Women | 1456 (27.3) | 516 (27.9) | 940 (27.0) | 490 (29.6) | 966 (26.3) | 16 (27.6) | 1440 (27.3) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | .014 | .083 | |||||||

| White | 3515 (66.0) | 1165 (63.0) | 2350 (67.5) | 1054 (63.6) | 2461 (67.1) | 37 (63.8) | 3478 (66.0) | |||

| Other/unknown | 78 (1.5) | 28 (1.5) | 50 (1.4) | 25 (1.5) | 53 (1.4) | 2 (3.4) | 76 (1.4) | |||

| URM | 710 (13.3) | 225 (12.2) | 485 (13.9) | 217 (13.1) | 493 (13.4) | 3 (5.2) | 707 (13.4) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1025 (19.2) | 430 (23.3) | 595 (17.1) | 362 (21.8) | 663 (18.1) | 16 (27.6) | 1009 (19.1) | |||

| Medical-school graduation year | .051 | <.001 | .015 | |||||||

| 1997 | 721 (13.5) | 248 (13.4) | 473 (13.6) | 212 (12.8) | 509 (13.9) | 17 (29.3) | 704 (13.4) | |||

| 1998 | 649 (12.2) | 235 (12.7) | 414 (11.9) | 199 (12.0) | 450 (12.3) | 8 (13.8) | 641 (12.2) | |||

| 1999 | 669 (12.6) | 228 (12.3) | 441 (12.7) | 236 (14.2) | 433 (11.8) | 9 (15.5) | 660 (12.5) | |||

| 2000 | 645 (12.1) | 220 (11.9) | 425 (12.2) | 228 (13.8) | 417 (11.4) | 6 (10.3) | 639 (12.1) | |||

| 2001 | 611 (11.5) | 245 (13.3) | 366 (10.5) | 217 (13.1) | 394 (10.7) | 7 (12.1) | 604 (11.5) | |||

| 2002 | 608 (11.4) | 202 (10.9) | 406 (11.7) | 198 (11.9) | 410 (11.2) | 4 (6.9) | 604 (11.5) | |||

| 2003 | 706 (13.3) | 248 (13.4) | 458 (13.2) | 211 (12.7) | 495 (13.5) | 4 (6.9) | 702 (13.3) | |||

| 2004 | 719 (13.5) | 222 (12.0) | 497 (14.3) | 157 (9.5) | 562 (15.3) | 3 (5.2) | 716 (13.6) | |||

| Degree program | .102 | .029 | <.001 | |||||||

| MD | 5285 (99.2) | 1828 (98.9) | 3457 (99.3) | 1638 (98.8) | 3647 (99.4) | 55 (94.8) | 5230 (99.2) | |||

| MD/PhD | 43 (0.8) | 20 (1.1) | 23 (0.7) | 20 (1.2) | 23 (0.6) | 3 (5.2) | 40 (0.8) | |||

| Career intention | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||

| Research- related | 2100 (39.4) | 1078 (58.3) | 1022 (29.4) | 937 (56.5) | 1163 (31.7) | 42 (72.4) | 2058 (39.1) | |||

| Other | 2384 (44.7) | 494 (26.7) | 1890 (54.3) | 481 (29.0) | 1903 (51.9) | 8 (13.8) | 2376 (45.1) | |||

| Missing | 844 (15.8) | 276 (14.9) | 568 (16.3) | 240 (14.5) | 604 (16.5) | 8 (13.8) | 836 (15.9) | |||

| Total debt | .098 | .003 | .067 | |||||||

| None | 802 (15.1) | 304 (16.5) | 498 (14.3) | 289 (17.4) | 513 (14.0) | 15 (25.9) | 787 (14.9) | |||

| $1 – $99,999 | 1817 (34.1) | 632 (34.2) | 1185 (34.1) | 570 (34.4) | 1247 (34.0) | 21 (36.2) | 1796 (34.1) | |||

| ≥ $100,000 | 1840 (34.5) | 633 (34.3) | 1207 (34.7) | 558 (33.7) | 1282 (34.9) | 13 (22.4) | 1827 (34.7) | |||

| Missing | 869 (16.3) | 279 (15.1) | 590 (17.0) | 241 (14.5) | 628 (17.1) | 9 (15.5) | 860 (16.3) | |||

| ≥1 year GME research | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

| No | 3480 (65.3) | --- | --- | 851 (51.3) | 2629 (71.6) | 12 (20.7) | 3468 (65.8) | |||

| Yes | 1848 (34.7) | --- | --- | 807 (48.7) | 1041 (28.4) | 46 (79.3) | 1802 (34.2) | |||

| F32 research fellowship awardc | <.001 | <.001 | .001 | |||||||

| No | 5242 (98.4) | 1770 (95.8) | 3472 (99.8) | 1612 (97.2) | 3630 (98.9) | 53 (91.4) | 5189 (98.5) | |||

| Yes | 86 (1.6) | 78 (4.2) | 8 (0.2) | 46 (2.8) | 40 (1.1) | 5 (8.6) | 81 (1.5) | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| USMLE Step l score | 218.3 (19.0) | 223.5 (18.8) | 215.5 (18.5) | <.001 | 221.0 (19.2) |

217.0 (18.8) |

<.001 | 230.0 (16.6) | 218.2 (19.0) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: GME = graduate medical education; RPG = research program grant; URM = underrepresented race/ethnicity in medicine; USMLE = United States Medical Licensing Examination; SD = standard deviation.

Values are frequencies (percentages) or means (SD), as noted. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Includes F32 research fellowship awards received at any time after medical-school graduation, not only during general surgery residency training.

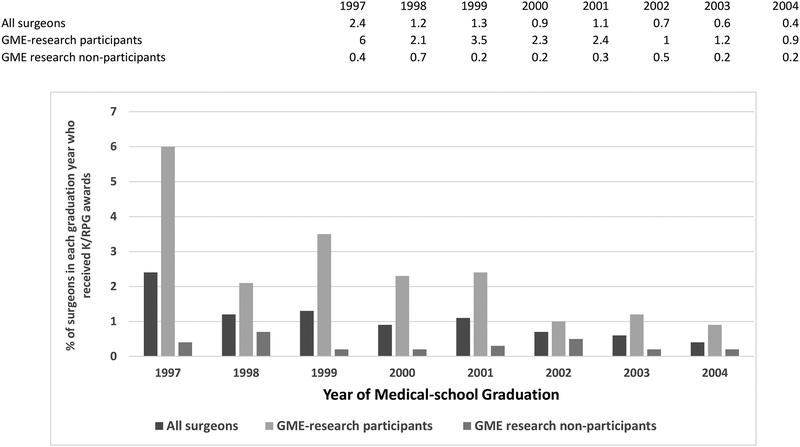

Figure 1 shows the percentage of surgeons within each graduation year who were K/RPG awardees. The percentage of surgeons who received K/RPG awards was highest among surgeons who graduated in 1997 and declined in more recent graduation years. The percentage of surgeons in each graduation year who subsequently received K/RPG awards was higher among GME-research participants than non-participants.

Figure 1.

K/RPG awardees among surgeons.

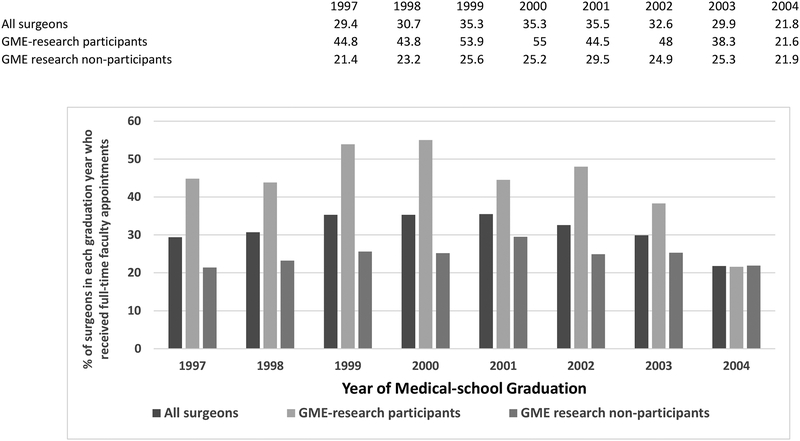

Figure 2 shows the percentage of surgeons within each graduation year who subsequently were appointed to academic-medicine faculty positions. The percentage of surgeons who became faculty was lowest among surgeons in the most recent graduation year. The percentage of surgeons in each graduation year who became faculty was higher among GME-research participants than non-participants except for graduates in 2004.

Figure 2.

Full-time faculty appointees among surgeons.

Table 2 shows results of multivariable logistic regression models that identified independent predictors of each of GME-research participation, faculty appointment, and K/RPG award. In the first model, surgeons who were Asian/Pacific Islander, reported research-related career intentions at graduation, and had higher Step l scores were more likely to have been GME-research participants. Sex, graduation year, degree program and debt were not independently associated with GME-research participation.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression models identifying variables independently associated with each of ≥1 year GME research, faculty appointment and federal mentored-K and/or RPG award receipt among board-certified surgeons who had graduated from LCME-accredited US medical schools in 1997–2004 (N = 5328).a

| ≥1 year GME research (yes vs. no) AOR (95% CI) | P-value | Faculty appointment (yes vs. no) AOR (95% CI)b | P-value | K/RPG award receipt (yes vs. no) AOR (95% CI)b | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| Women | 1.011 (0.883 – 1.157) | .878 | 1.147 (1.002 – 1.314) | .047 | 1.271 (0.697 – 2.317) | .434 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| Other/unknown | 1.006 (0.616 – 1.643) | .981 | 0.952 (0.578 – 1.570) | .848 | 1.898 (0.423 – 8.510) | .402 |

| URM | 1.106 (0.917 – 1.334) | .292 | 1.069 (0.886 – 1.289) | .486 | 0.579 (0.173 – 1.932) | .374 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.317 (1.130 – 1.535) | <.001 | 1.072 (0.917 – 1.253) | .381 | 1.168 (0.634 – 2.154) | .618 |

| Medical-school graduation yearc | 0.980 (0.954 – 1.006) | .126 | 0.964 (0.939 – 0.990) | .008 | 0.765 (0.670 – 0.874) | <.001 |

| Degree program | ||||||

| MD | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| MD/PhD | 1.017 (0.544 – 1.902) | .957 | 1.385 (0.746 – 2.573) | .302 | 8.956 (2.445 – 32.807) | .001 |

| Career intention at graduation | ||||||

| Not research-related | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| Research-related | 3.483 (3.043 – 3.987) | <.001 | 2.529 (2.197 – 2.910) | <.001 | 2.679 (1.206 – 5.952) | .016 |

| Missing | 2.245 (1.475 – 3.417) | <.001 | 1.926 (1.256 – 2.953) | .003 | 1.233 (0.242 – 6.286) | .801 |

| Total debt at graduation | ||||||

| None | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| $1 – $99,999 | 0.960 (0.798 – 1.156) | .669 | 0.842 (0.700 – 1.013) | .068 | 0.651 (0.327 – 1.297) | .223 |

| ≥ $100,000 | 0.948 (0.787 – 1.142) | .575 | 0.817 (0.678 – 0.984) | .033 | 0.518 (0.239 – 1.120) | .094 |

| Missing | 0.746 (0.484 – 1.149) | .184 | 0.629 (0.406 – 0.975) | .038 | 1.136 (0.250 – 5.155) | .869 |

| ≥1 year GME research | ||||||

| No | ---- | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| Yes | ---- | 1.790 (1.573 – 2.037) | <.001 | 4.596 (2.355 – 8.969) | <.001 | |

| F32 research fellowship award | ||||||

| No | ---- | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | |||

| Yes | ---- | 1.413 (0.906 – 2.203) | .128 | 1.990 (0.744 – 5.318) | .170 | |

| USMLE Step l scored | 1.019 (1.016 – 1.023) | <.001 | 1.004 (1.001 – 1.008) | .011 | 1.027 (1.010 – 1.044) | .002 |

Abbreviations: GME = graduate medical education; RPG = research program grant; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; URM = underrepresented race/ethnicity in medicine; USMLE = United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Each model fit the data (each Hosmer and Lemeshow Test P >.05)

AOR < 1.000 indicates a lower likelihood of outcome with each more-recent graduation year.

AOR >1.000 indicates a greater likelihood of outcome with each point increase in Step l score.

In the second model, surgeons who were women, had research-related career intentions at graduation, were GME-research participants, and had higher Step l scores were more likely to have held faculty appointments, whereas surgeons who graduated more recently and reported debt of ≥ $100,000 at graduation were less likely to have held faculty appointments. Race/ethnicity, degree program and F32 award were not independently associated with faculty appointment.

In the third model, surgeons who had research-related career intentions at graduation, were MD/PhD graduates, were GME-research participants, and had higher Step l scores were more likely to be K/RPG awardees, whereas surgeons who graduated more recently were less likely to be K/RPG awardees. Sex, race/ethnicity, debt and F32 award were not independently associated with K/RPG award.

DISCUSSION

In our national sample, 34.7 % of surgeons had participated in ≥1 year of research during general surgery residency, a prevalence closely aligned with results of a national survey of general surgery program directors administered in 2006 in which 36% of all general surgery residents had reportedly participated in ≥1 year of research.1 Our findings regarding independent predictors of GME-research participation, faculty appointment, and K/RPG awards have implications for academic surgery and the federally funded, surgeon-scientist workforce.

Lack of racial/ethnic diversity among physician-scientists and academic surgeons are issues of national concern.7,22,23 In our study, URM surgeons were as likely as white surgeons to have participated in ≥1 year of GME research, and to have received faculty appointments and K/RPG awards. Thus, efforts to increase entry and retention of URM medical-school graduates in general surgery training programs should ultimately serve to increase diversity of the academic surgery23 and the federally funded surgeon-scientist workforces.

Women comprised 27.3% of surgeons in our study and remain underrepresented among general surgery residents compared to their proportions among all US LCME-accredited medical-school graduates.24,25 However, we did not observe a sex difference in GME-research participation. Our observation that women were more likely than men to be faculty appointees aligns with other national studies of US medical-school graduates across all specialties.10,26

That surgeons with research-related career intentions at graduation had been more likely to participate in GME research could be due, in part, to choice as medical students of residency-training programs to rank and choice as residents to participate in optional dedicated GME-research year(s). In models adjusting for GME-research participation, surgeons with research-related career intention at graduation also were more likely to receive faculty appointments and K/RPG awards. These findings underscore the critical importance of interventions during medical school to stimulate interest in research-related careers among students considering general surgery. Surgery Interest Groups may provide such opportunities for students, as the American College of Surgeons reported that nearly half of all medical schools have such groups.27

In our study, MD/PhD graduates were 9 times more likely than MD graduates to receive K/RPG awards; MD/PhD graduation was the single strongest independent predictor of K/RPG award. These observations are consistent with other reports that MD/PhD-program participation can be a particularly successful path to federally funded research careers in general.9,28 Although MD/PhD-program graduates have comprised only about 2% of all US LCME-accredited medical-school graduates,29 MD/PhD dual-degree holders have comprised about one third of physician applicants for mentored-K and R01 awards; funding success rates are reportedly similar for MD/PhD dual-degree and MD degree-holders.8,30 In recent years, there has been a shift in MD/PhD-program graduates’ specialties away from “traditional” MD/PhD-program graduates’ choices (i.e., medicine, neurology, pathology, and pediatrics), towards surgery and other specialties.28,31,32 Thus, our findings regarding MD/PhD graduates should be of interest to medical schools and federal agencies that fund MD/PhD programs.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to examine the relationship between surgeons’ GME-research participation and faculty appointment. Our findings extend previous single institutional findings of general surgery training-program graduates’ career paths2–4 and a national survey of general surgery residents’ career intentions.23 That graduation year was negatively associated with faculty appointment in our sample was not unexpected as faculty appointees continue to accrue among US medical school graduates for 15 years after graduation.33 We have not yet followed the surgeons in our study beyond initial faculty appointment to determine if GME-research participation is associated with a greater likelihood of academic-medicine retention and promotion, which will be additional long-term indicators of success as academicians, beyond initial appointment.

Our study is also the first national study to describe an independent association between surgeons’ GME-research participation and federal K/RPG awards. The prevalence of federal K/RPG awards among surgeons in our national sample was lower than NIH-award rates observed in two older single-university program survey studies of surgeons who had completed their general surgery training at programs in which most trainees were GME-research participants.3,4 Differences in study design, sample composition, duration of follow-up, and NIH-award measures likely contributed to the disparate prevalence of awards noted across the three studies. Mentored-K and RPG awards should be considered long-term outcomes for medical-school graduates. Mentored-K applications typically are submitted 3–5 years after graduation for K01 and 7–9 years for K08 and K23 awards;34 the average time from medical-school graduation to first RPG is 17 years for MD graduates and 13 years for MD/PhD graduates.7 Importantly, most mentored-K and R01 physician applicants’ and awardees’ departmental affiliations are in specialties with shorter required years of GME training for general certification in the specialty (e.g., 3 years for internal medicine and pediatrics compared with 5 years for surgery).34,35 Thus, the average duration from medical-school graduation to mentored-K and RPG awards should be expected to be even longer for surgeons. Our findings regarding K/RPG awards among surgeons should be considered preliminary; with longer follow-up after GME completion, K/RPG awardees in our sample should continue to accrue.9 This accrual may be limited by the increasingly challenging environment for surgeon-scientists, characterized by a 27% decline in recent years in the proportion of NIH funding to surgical departments relative to total NIH funding, increasing pressures on academic surgeons to be clinically productive, and excessive administrative responsibilities.36

A strong positive association between mentored-K awards and future R01 awards has been observed among physicians in general,7,9,34 and a 46% conversion rate of mentored-K awards to R01s was recently reported among surgeon-scientists in particular.37 In addition, a longitudinal survey study of 957 clinician-researcher K08 and K23 awardees found that those in surgical (vs. medical) specialties were more likely to report career success (i.e., any one [vs. none] of >$1 million in funding or R01 award as principal investigator, ≥35 peer-reviewed publications, and holding a leadership position as dean, department chair, or division chief).38 Thus, the value of mentored-K award program participation for surgeons extends to multiple measures of career success.

As we received only publicly available award data under the Freedom of Information Act,39 our findings regarding variables associated with K/RPG awards may reflect differences in grant application rates and/or funding success rates among applicants. Future research with applicant-level data is warranted to inform the design of interventions that promote greater participation in the biomedical-research workforce among US medical-school graduates pursuing surgical careers.

Debt has been cited as a potential deterrent to medical-school graduates’ engagement in research-related careers in general,6 and pursuit of research during or after surgery residency, in particular.40 Surgeons in our study with ≥ $100,000 in debt at graduation were less likely to receive faculty appointments. Our finding regarding a negative association between debt and academic-medicine career aligns with results of a national general surgery resident survey, which reported that high debt (>$150,000) among senior residents was associated with a lower likelihood of academic-medicine career plans.23 Our findings underscore the importance of promoting awareness about NIH Loan Repayment Programs among highly indebted general surgery residents who might otherwise consider pursuing research-related careers.41

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first national study to examine independent associations between GME-research participation during general surgery training and long-term outcomes of faculty appointment and federal K/RPG awards. We also explored numerous variables not previously included in general surgery GME-research studies (e.g., career intention at graduation, race/ethnicity, Step 1 score and debt).

Our study also has limitations. Because our study is a retrospective, observational study, causality cannot be inferred from the associations we observed. We did not have information regarding whether GME-research participants in our study had been engaged in basic or clinical research. In a national survey of general surgery program directors, 72% of residents in their programs who completed ≥1 year of dedicated research did so in basic sciences.1 Similarly, according to a 2015 survey of members of the Association of Academic Surgery and the Society of University Surgeons, 66% of those who reported doing research during surgical training indicated that the primary focus was basic science.36 We also did not have information regarding program type (e.g., university, university-affiliated or independent) in which surgeons in our study trained; outcomes for trainees of specific types of programs may differ, especially with regard to emphasis on training for academic-medicine and/or research careers. Our GME-research participation variable was based on information reported by general surgery program directors on the annual National GME Census, which is administered jointly by the AMA and the AAMC and contains information about Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited training programs and the trainees in these programs. In the academic years from 2001–2002 through 2012–2013,42,43 data for an average of about 95% of active trainees were provided annually by program directors across all specialties; the percentage of active trainees with data during these years ranged from 97.3% in 2004–200544 to 92.5% in 2009–2010.45 We also lacked information regarding whether GME-research participation was required or optional; currently, most general surgery programs do not require ≥1 year of dedicated GME research. In 2016–2017, of 256 general surgery program directors (94% of all 273 general surgery programs) who provided information on the National GME Census, only 22 (8.6%) reported requiring ≥1 year of GME research (Sarah Brotherton, PhD, American Medical Association, personal communication, email dated January 29, 2018).

Our findings may not be generalizable to graduates of non-US-LCME-accredited medical schools (e.g., Doctor of Osteopathy or international medical schools), who comprise about 20% of general surgery trainees.24 The degree-program variable may have under-counted MD/PhD-program graduates among medical-school graduates who initially matriculated in the earliest years in our study period,46 and MD/PhD-program graduates who matriculated during our study period may be underrepresented in our sample as they take, on average, 8 years to complete the dual-degree program requirements.31

Finally, we examined federal funding records for F32, mentored-K and RPG awards to principal investigators in our national cohort; we did not receive information about individuals in our cohort who may have been engaged in federally funded research as co-investigators. It is also important to note that many surgeons have non-federal, extramural funding for their research. According to results of a recent survey of 2,504 Association for Academic Surgery and Society of University Surgeons members, 47% of the 757 faculty respondents had extramural funding, including 69% of those faculty respondents who were engaged in basic science research. Among faculty respondents conducting extramurally funded basic science research, funding sources included NIH (51%), other federal agencies (19%), foundations (29%), surgical societies (18%), and other extramural sources (21%); some respondents reported multiple funding sources.36 However we did not have access to information about non-federal sources of funding, such as industry and private foundations, which have been less publicly available than federal grants data.37

Nonetheless, our findings inform the evidence base regarding variables associated with general surgery GME-research participation and whether such participation is associated with full-time faculty appointment and with K/RPG awards. Our findings can serve as national benchmarks for studies evaluating new models of training for surgeon-scientists47 and of research training during residency, such as the NIH R38 StARR program.48 Dedicated research year(s) at the end of, rather than during, general surgery training for surgeons pursuing academic careers might facilitate new faculty appointees’ ability to continue their research and better position them to seek funding earlier in their careers. Our observations also might be of interest to general surgery program directors in selecting applicants to interview and rank for their training programs, especially those programs intending to train academicians and surgeon-scientists.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Paul Jolly, PhD (retired)at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), for provision of the data and assistance with coding; the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) for permission to use de-identified Step 1 scores; and James Struthers, BA, and Maria Pérez, MA, in the Division of General Medical Sciences at Washington University School of Medicine for assistance with data management and administrative support. The American Medical Association (AMA) is the source for the raw Physician Masterfile data. Tabulations of the data were prepared by the authors with the AMA Masterfile data. The board certification information presented herein is proprietary data maintained in a copyrighted database compilation owned by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).

Funding/Support:Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM085350).

Conflicts of interest and source of funding:Drs. Andriole and Jeffe received funding support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (2R01 GM085350) for this study. For the remaining authors, no sources of funding were declared. Dr. Klingensmith served as a volunteer, uncompensated member of the Board of Directors of the American Board of Surgery when this study was completed. For the remaining authors, no conflicts of interest were declared.

Footnotes

Other disclosures:Mary E. Klingensmith served as a volunteer, uncompensated member of the Board of Directors of the American Board of Surgery when this work was completed.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University School of Medicine as non-human subjects research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers:The conclusions of the authors are not necessarily those of the AAMC, NBME, AMA, ABMS, NIH, or their respective staff members. The funding agency was not involved in the design or conduct of the study; in collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dorothy A. Andriole, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

Mary E. Klingensmith, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

Ryan C. Fields, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

Donna B. Jeffe, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

References

- 1.Robertson CM, Klingensmith ME, Coopersmith CM. Prevalence and Cost of Full-Time Research Fellowships During General Surgery Residency: A National Survey. Annals of Surgery. 2009;249(1):155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur A, Thakur V, Fonkalsrud EW, Singh S, Buchmiller TL. The outcome of research training during surgical residency. J Surg Res. 2000;90:10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson CM, Klingensmith ME, Coopersmith CM. Long-term outcomes of performing a postdoctoral research fellowship during general surgery residency. Annals of Surgery. 2007;245(4):516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya SD, Williams JB, de la Fuente SG, Kuo PC, Seigler HF. Does protected research time during general surgery training contribute to graduates’ career choice? Am Surg. 2011;77(7):907–910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall AK, Mills SL, Lund PK. Clinician-investigator training and the need to pilot new approaches to recruiting and retaining this workforce. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1382–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrison HH, Deschamps AM. NIH research funding and early career physician scientists: continuing challenges in the 21st century. The FASEB Journal. 2014;28:1049–1058. PMCID: PMC3929670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group Report. Available at: http://acd.od.nih.gov/reports/PSW_Report_ACD_06042014.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2018 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science. 2008;322:1472–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. Prevalence and Predictors of U.S. Medical Graduates’ Federal F32, Mentored-K, and R01 Awards: A National Cohort Study. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2018;66:340–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andriole DA, Jeffe DB. The road to an academic medicine career: A national cohort study of male and female U.S. medical graduates. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1722–1733. PMCID: PMC3631320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffe DB, Yan Y, Andriole DA. Do research activities during college, medical school, and residency mediate racial/ethnic disparities in full-time faculty appointments at U.S. medical schools? Acad Med. 2012;87:1582–1593. PMCID: PMC3592974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Board of Medical Specialties. Report of the special committee on physician-scientist & continuing certification. June 2016. Available at: http://www.abms.org/media/119931/abms_physicianscientists_report.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2018.

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges. Student Records System (SRS). Available at: https://www.aamc.org/services/srs/. Accessed May 15, 2017.

- 14.Association of American Medical Colleges. Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/gq/. Accessed May 15, 2017.

- 15.Association of American Medical Colleges. GME Track. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/services/gmetrack/. Accessed May 15, 2018.

- 16.Association of American Medical Colleges. Faculty Roster. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster/. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 17.American Medical Association (AMA). AMA Physician Masterfile. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/life-career/ama-physician-masterfile. Accessed December 29, 2017.

- 18.National Resident Matching Program. Data Release and Research Committee: Results of the 2014 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC: 2014. Available at http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/PD-Survey-Report-2014.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szenas P, Jolly P. Charting outcomes in the match: characteristics of applicants who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2007 NRMP main residency match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program and Association of American Medical Colleges; Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/data/chartingoutcomes2007.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2009; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Resident Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of Applicants Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2014 Main Residency Match. 5th Edition, August 2014. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC: 2014. Available at http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Charting-Outcomes-2014-Final.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillestad R, Bigelow JH, Chaudhry B, et al. IDENTITY CRISIS: An Examination of the Costs and Benefits of a Unique Patient Identifier for the US Health Care System (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2008). Available at: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2008/RAND_MG753.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017. In. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler PD, Longaker MT, Britt LD. Major deficit in the number of underrepresented minority academic surgeons persists. Annals of Surgery. 2008;248:704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julien JS, Lang R, Brown TN, et al. Minority underrepresentation in academia: factors impacting careers of surgery residents. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2014;1:238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate Medical Education, 2015–2016. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2291–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-4: Total U.S. Medical School Graduates by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2012–2013 through 2014–2015. 11/25/2015. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/321536/data/factstableb4.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 26.Nonnemaker L Women physicians in academic medicine: New insights from cohort studies. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Surgeons. Surgical Interest Group. Available at: https://www.facs.org/education/resources/medical-students/sigs. Accessed October 6, 2017.

- 28.Harding CV, Akabas MH, Andersen OS. History and outcomes of 50 years of physician-scientist training in Medical Scientist Training Programs. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1390–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andriole DA, Whelan AJ, Jeffe DB. Characteristics and career intentions of the emerging MD/PhD workforce. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1165–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginther DK, Haak LL, Schaffer WT, Kington R. Are race, ethnicity, and medical school affiliation associated with NIH R01 type l award probability for physician investigators? Acad Med. 2012;87:1516–1524. PMCID: PMC3485449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. A national cohort study of MD-PhD graduates of medical schools with and without funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences’ Medical Scientist Training Program. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):953–961. PMCID: PMC3145809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahn J, Watt CD, Man L, Greeley SAW, Shea JA. Educating future leaders of medical research: analysis of student opinions and goals from the MD-PhD SAGE (Students’ Attitudes, Goals, and Education) survey. Acad Med. 2007;82(7):633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison E, Liu C. How long does it take to proceed from an MD degree to a medical school faculty appointment? Analysis in Brief Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges; July 2015. Available at https://www.aamc.org/download/438092/data/july2015aib_proceedingtofacultyappointment.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institutes of Health. Individual Mentored Career Development Awards Program Evaluation Working Group. National Institutes of Health Individual Mentored Career Development Awards Program. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, August 29, 2011. Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/training/K_Awards_Evaluation_FinalReport_20110901.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2018 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Board of Medical Specialties. 2013–2014 ABMS Board Certification Report. Available at: http://www.abms.org/media/84770/2013_2014_abmscertreport.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2017.

- 36.Keswani SG, Moles CM, Morowitz M, et al. The future of basic science in academic surgery: identifying barriers to success for surgeon-scientists. Annals of surgery. 2017;265(6):1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narahari AK, Mehaffey JH, Hawkins RB, et al. Surgeon Scientists Are Disproportionately Affected by Declining NIH Funding Rates. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2018;226(4):474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones RD, Stewart A, Ubel PA. Factors associated with success of clinician–researchers receiving career development awards from the National Institutes of Health: A longitudinal cohort study. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1429–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institutes of Health. NIH Grants Policy Statement. Section 2.3.11.2.2 The Freedom of Information Act, 2013. Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/nihgps_2013/nihgps_ch2.htm. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 40.Suliburk JW, Kao LS, Kozar RA, Mercer DW. Training future surgical scientists: realities and recommendations. Annals of Surgery. 2008;247:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program Evaluation Working Group. NIH LRP evaluation: Extramural loan repayment programs fiscal years 2003–2007. April, 2009. Available at: http://www.lrp.nih.gov/pdf/LRP_Evaluation_Report_508final06082009.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 42.Brotherton SE, Simon FA, Etzel SI. US graduate medical education, 2001–2002. JAMA. 2002;288:1073–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2012–2013. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2328–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brotherton SE, Rockey PH, Etzel SI. US graduate medical education, 2004–2005: trends in primary care specialties. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1255–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. In reply to Akabas and Brass and to Mittwede. Acad Med. July 2014;89(7):959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore HB, Moore EE, Nehler MR, et al. Bridging the gap from T to K: integrated surgical research fellowship for the next generation of surgical scientists. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2014;218(2):279–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Department of Health and Human Services. Stimulating Access to Research in Residency (StARR) (R38). Available at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HL-18-023.html. Accessed November 1, 2017.