Abstract

We report on 499 patients with severe aplastic anemia aged ≥50 years who underwent hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched sibling (n=275), or HLA-matched (8/8) unrelated donors (n=39187) between 2005 and 2016. The median age at HCT was 57.8 years; 16% of patients were 65–77 years old. Multivariable analysis confirmed higher mortality risks for patients with performance score less than 90% (HR 1.41 (1.03–1.92), p=0.03) and after unrelated donor transplantation (HR 1.47 (1–2.16), p=0.05). The 3-year probabilities of survival for patients with performance score 90–100 and less than 90 after HLA-matched sibling transplant were 66% (57–75%) and 57% (47–76%), respectively. The corresponding probabilities after HLA-matched unrelated donor transplantation were 57% (48–67%) and 48% (36–59%). Age at transplantation was not associated with survival but grade II-IV acute GVHD risks were higher for patients aged 65 years or older (sHR 1.7 (1.07–2.72), p=0.026). Chronic GVHD was lower with GVHD prophylaxis regimens calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) + methotrexate (sHR 0.52 (0.33–0.81), p=0.004) and CNI alone or other agents (sHR 0.27 (0.14–0.53), p<0.001) compared to CNI + mycophenolate. While donor availability is modifiable only to a limited extent, choice of GVHD prophylaxis and selection of patients with good performance scores are key for improved outcomes.

Introduction

Treatment algorithms for severe aplastic anemia (SAA) are not well characterised for older patients. For older patients, treatment decisions are based not only on disease factors but also on their health and functional ability, in order to reduce the risk of treatment-related toxicity that may contribute to morbidity and mortality 1. For these reasons, HCT in older patients with SAA is usually only considered as second line treatment 2.

Existing data on outcomes after HCT or immunosuppressive therapy (IST) have examined different age groups, > 40 years for HCT 5–7 and > 60 years for IST 6–8. First line IST using horse anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine (CSA) in patients aged > 60 years is associated with a similar response that in younger patients but survival is worse in older patients 3,4,5. Although HLA-matched related and unrelated donor transplantation are offered to patients who are fit, and as first line treatment for matched related or those who fail first line IST for matched unrelated donor HCT, increasing age at transplantation (> 40 years) remains a concern 6–8. However, a recent report on 115 adults failed to show a difference in survival after HLA-matched sibling transplantation 9. A second course of IST is effective in only a third of cases and it increases the risk of later progression to myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) 10,11. The recent use of eltrombopag for refractory SAA is effective in 40% of patients although 19% of patients reported early onset of abnormal cytogenetic clones (most commonly monosomy 7) 12.

A retrospective natural history study of aplastic anemia covering the whole of Sweden has highlighted the significantly worse survival for patients aged ≥ 60 years compared to younger patients where less than 40% were alive after 5 years and with a relative 5-year survival (excess mortality) of 45% 13. Hence there is an unmet need to improve the management of this older group of patients with aplastic anemia. However, there are no data specifically addressing HCT outcomes in a relatively large cohort of SAA patients older than 50 years. Herein we report for the first time a cohort of 538 SAA patients older than 50 years at transplantation and reported to the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplant (EBMT) or the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR).

Methods

Patients

Data on patients were obtained from two international transplant registries; the CIBTMR and the EBMT. Both registries collect data on consecutive transplantations performed at participating sites and patients are followed longitudinally until death or lost to follow up. Transplantations occurred between 2005 and 2016 in Europe or North America. Ethical approval for studying transplantations reported to the EBMT was granted by the EBMT SAA Working Party. The Institutional Review Board of the National Marrow Donor Program approved studying transplantations reported to the CIBMTR and this study.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients were aged 50 years or greater, with SAA and transplanted from a HLA matched sibling or adult matched unrelated donor (8/8 reported or 8/8 high resolution). Patients transplanted from a haplo-identical donor, umbilical cord blood or those who reported a prior HCT were excluded.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint was overall survival. Death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at 36 months, based on the median follow-up for this study: 42 (37–49) months. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥0.5 × 109/L for two consecutive days, before day 28. Platelet recovery was defined as achieving an unsupported platelet count of ≥20 × 109/L for 7 days, before day 100. Engraftment failure included primary and secondary graft failure captured through day 100 and defined as failing to achieve ANC ≥0.5 × 109/L, donor chimerism <5%, subsequent loss of ANC to less than 0.5 × 109/L, or second infusion. Grade II-IV acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was defined according to standard criteria 14,15.

Statistical analysis

The probability of overall survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimation method, and differences in subgroups were assessed by the Log-Rank test. All estimates of overall survival are provided at 36 months post-transplant, and are reported with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Median follow-up was determined using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess the impact of potential risk factors on mortality in multivariable analyses, providing hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence intervals. The incidences of hematopoietic recovery, acute and chronic GVHD and primary and secondary graft failure were calculated in a competing risks framework. Competing events for each outcome include mortality, no engraftment, relapse and second transplant. Subgroup differences were assessed by Gray’s test. Multivariable Fine & Gray regression was used to study risk factors associated with acute and chronic GVHD, providing sub-distribution HRs (sHR) with 95% confidence intervals. All p-values were two-sided and p≤0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed in SPSS 23 (Armonk, NY, USA) and in R 3.3.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) using packages “survival”, “prodlim” and “cmprsk”.

Results

Patient and transplant characteristics

Patient and transplant characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes between EBMT and CIBMTR registries are summarised in Supplemental File. The median age at transplantation was 57.8 years (range 50–77.7). Out of 499 patients, most (n=420; 84%) were aged 50–64 years and only 16% (n=79) were 65 years or older. Fifteen patients were 70 years or older accounting for only 3% of the patient population. Performance scores (Karnofsky) of 90 or 100 were observed in 49% of patients. Sixty seven percent of patients were cytomegalovirus seropositive and 38.5% of transplantations occurred at least a year after diagnosis (median 10, range <1–357). Of the patients with available IST information, 89.6% received at least one course of prior immune suppressive treatment. Fifty-five percent of patients received their graft from an HLAmatched sibling, and 38% from an HLA-matched unrelated donor. For the remaining 7%, the degree of mismatching was unknown. Approximately equal numbers of patients received bone marrow (53%) and peripheral blood (47%) grafts. Cyclophosphamide with ATG alone or with ATG and fludarabine were the predominant conditioning regimens for HLA-matched sibling HCT, whereas for unrelated donor HCT, cyclophosphamide with total body irradiation (TBI) 200 cGy and ATG or with the inclusion of fludarabine, were mostly used. Most patients received calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) containing GVHD prophylaxis. Among the 117 patients who received CNI + mycophenolate, 53 (45%) received ATG-containing and 5 (4%) received alemtuzumab-containing conditioning regimen. Similarly, 101 of 246 (41%) patients who received CNI + methotrexate received ATG-containing and 7 (3%), alemtuzumab-containing conditioning regimen. Forty seven of 110 (43%) patients who received CNI alone or other agents for GVHD prophylaxis received alemtuzumab-containing and 33 of 110 (30%), received ATG conditioning regimen. As unrelated donor transplants were more recent, the median follow up was 38 (36–45) months and that after HLA-matched sibling transplants, 49 (38–58) months. The median follow-up of the combined population was 42 (37–49) months and outcomes were censored at 36 months to accommodate differential follow up.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Registry | CIBMTR | 194 | 38.9 |

| EBMT | 305 | 61.1 | |

| Age | ≥65 | 79 | 15.8 |

| 50–64 | 420 | 84.2 | |

| Patient sex | Female | 245 | 49.1 |

| Male | 254 | 50.9 | |

| Performance score | <90% | 190 | 38.1 |

| 90–100% | 243 | 48.7 | |

| Missing | 66 | 13.2 | |

| Patient CMV | Negative | 126 | 25.3 |

| Positive | 335 | 67.1 | |

| Missing | 38 | 7.6 | |

| Interval diag-Tx | ≤12 | 307 | 61.5 |

| >12 | 192 | 38.5 | |

| Donor | Matched unrelated | 187 | 37.5 |

| HLA-identical sibling | 275 | 55.1 | |

| Missing | 37 | 7.4 | |

| Graft source | Bone marrow | 266 | 53.3 |

| Peripheral blood | 233 | 46.7 | |

| Regimen | Cy + ATG | 91 | 18.2 |

| Cy + Flud ± ATG | 92 | 18.4 | |

| TBI 200 + Cy + Flud + ATG | 57 | 11.4 | |

| TBI 200 + Cy ± ATG | 28 | 5.6 | |

| Alkylating agent + Flud ± ATG | 65 | 13 | |

| Alemtuzumab | 60 | 12 | |

| Flud + Cy + Alemtuzumab | 40 | ||

| Alemtuzumab + Other | 20 | ||

| Other non-TBI regimen | 73 | 14.6 | |

| Other TBI regimens | 18 | 3.6 | |

| Missing | 15 | 3 | |

| GvHD prophylaxis | CNI + MMF | 117 | 23.4 |

| CNI + MTX | 246 | 49.3 | |

| CNI ± other drug | 67 | 13.4 | |

| Other | 43 | 8.6 | |

| Missing | 26 | 5.2 | |

| HSCT year | 2005–2009 | 191 | 38.3 |

| 2010–2014 | 308 | 61.7 | |

| Age | Median (range) | 499 | 57.8 (50–77.7) |

| Interval diag-Tx (yrs) | Median (range) | 499 | 0.8 (<1–29.7) |

| Follow-up | Median (95% CI) | 42.4 (37.2 – 48.9) |

Hematologic recovery

The incidence of primary graft failure at 100 days was 10% (7–12%). The incidence of secondary graft failure at 36 months after transplantation among patients with initial engraftment was 7% (4–10%). Day 28 cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was 82% (79–86%). Multivariable analysis for risk factors associated with neutrophil recovery is shown in Table 2. Neutrophil recovery was higher in patients receiving peripheral blood grafts compared to bone marrow (sHR = 1.74 (1.38–2.2), p<0.001) and lower in patients receiving CNI + methotrexate compared to CNI + mycophenolate as GVHD prophylaxis (sHR = 0.59 (0.44–0.8), p<0.001).

Table 2:

Risk factors for overall survival and neutrophil recovery

| Overall Survival | N | N-event | HR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 424 | 164 | |||

| Registry | EBMT | 246 | 88 | ||

| CIBMTR | 178 | 76 | 0.98 (0.71 – 1.36) | 0.918 | |

| Age | 50–64 | 354 | 132 | ||

| >=65 | 70 | 32 | 1.21 (0.81 – 1.81) | 0.343 | |

| Patient sex | Male | 216 | 88 | ||

| Female | 208 | 76 | 0.82 (0.6 – 1.12) | 0.205 | |

| Performance score | <90% | 189 | 83 | ||

| 90–100% | 235 | 81 | 0.71 (0.52 – 0.97) | 0.03 | |

| GvHD prophylaxis | CNI + MMF | 99 | 39 | ||

| CNI + MTX | 223 | 91 | 1.22 (0.82 – 1.81) | 0.319 | |

| Other | 102 | 34 | 0.86 (0.54 – 1.38) | 0.537 | |

| Donor | Identical sibling | 221 | 78 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 203 | 86 | 1.47 (1 – 2.16) | 0.05 | |

| Regimen | non-TBI regimen | 321 | 122 | ||

| TBI regimen | 103 | 42 | 0.76 (0.49 – 1.19) | 0.226 | |

| Graft source | Bone marrow | 229 | 90 | ||

| Peripheral blood | 195 | 74 | 0.96 (0.7 – 1.32) | 0.813 | |

| Interval diag-Tx (yrs) | 424 | 0.99 (0.94 – 1.05) | 0.818 | ||

| Neutrophil recovery | N | N-event | sHR (95% CI) | p | |

| Total | 406 | 368 | |||

| Registry | EBMT | 232 | 210 | ||

| CIBMTR | 174 | 158 | 1.32 (1.06 – 1.65) | 0.014 | |

| Age | 50–64 | 337 | 307 | ||

| >=65 | 69 | 61 | 0.95 (0.7 – 1.3) | 0.76 | |

| Performance score | <90% | 181 | 158 | ||

| 90–100% | 225 | 210 | 1.24 (0.99 – 1.54) | 0.062 | |

| Patient CMV | negative | 114 | 105 | ||

| positive | 292 | 263 | 1.13 (0.91 – 1.41) | 0.27 | |

| GvHD prophylaxis | CNI + MMF | 98 | 92 | ||

| CNI + MTX | 210 | 188 | 0.59 (0.44 – 0.8) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 98 | 88 | 0.78 (0.55 – 1.1) | 0.15 | |

| HSCT period | 2005–2009 | 133 | 119 | ||

| 2010–2014 | 273 | 249 | 1.14 (0.89 – 1.45) | 0.29 | |

| Donor | Identical sibling | 210 | 189 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 196 | 179 | 0.99 (0.79 – 1.24) | 0.92 | |

| Graft source | Bone marrow | 223 | 199 | ||

| Peripheral blood | 183 | 169 | 1.74 (1.38 – 2.2) | <0.001 | |

Overall survival

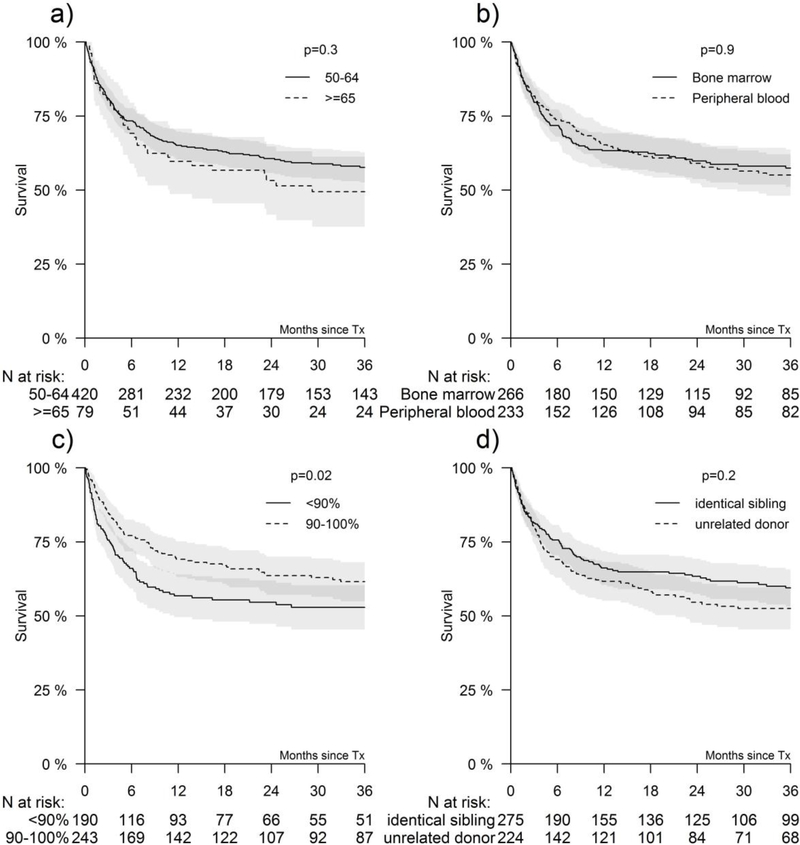

The 3-year probability of overall survival for the entire cohort was 56% (52–61%) and 59% (53–66%) and 52% (45–60%) for matched related and matched unrelated donor HCT, respectively. The 3-year probabilities of survival for patients with performance score 90–100 and less than 90 after HLA-matched sibling transplant were 66% (57–75%) and 57% (4776%), respectively (Figure 1). The corresponding probabilities after unrelated donor transplantation were 57% (48–67%) and 48% (36–59%) (Figure 1). None of the other variables tested including age at HCT, CMV serostatus, graft type, interval between diagnosis and HCT and transplant period attained the level of significance set for this study.

Figure 1. Factors affecting overall survival.

Figure 1A shows OS by age <65 vs. ≥65 years, Figure 1B by stem cell source, Figure 1C performance status, and Figure 1D by donor type. The shaded regions indicate the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Reported p-values are based on the log-rank test.

Multivariable analysis confirmed higher mortality risks for patients with a performance score of less than 90% and recipients of unrelated donor HCT (Table 2). The effects of performance score and donor type on overall survival were independent of each other.

There was no significant difference in mortality risk for older patients aged 65–78 years compared to those aged 50–64 years (HR = 1.20, 0.81–1.81, p=0.343). There were 215 deaths; infection was the predominant cause of death, accounting for 40% of deaths followed by GVHD (13%), multi-organ failure (10%) and graft failure (9%). Other causes included malignancy, including EBV associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (5%), interstitial pneumonitis (1%) and other toxicities (7%). The cause of death was not reported for 15% of patients.

Graft versus host disease

The day 100 incidence of acute GVHD in patients aged 50 – 64 years was 20% (16–24%) and those aged 65 years and older, 35% (24–46%), p=0.006. The corresponding incidence for patients who received CNI + mycophenolate was 33% (24–42%), CNI + methotrexate 24% (18–29%), CNI alone or other GVHD prophylaxis regimens were 13% (7–20%), respectively (Figure 1C). The results of multivariable analysis for risk factors associated with acute and chronic GVHD are shown in Table 3. Risk for grade II-IV acute GVHD was higher for patients aged 65 years and older, and lower for those who received CNI alone or other agents compared to CNI + mycophenolate (sHR 0.48 (0.26–0.88), p=0.018).

Table 3:

Risk factors for acute and chronic GVHD

| Acute GvHD | N | N-event | sHR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 404 | 95 | |||

| Registry | EBMT | 229 | 36 | ||

| CIBMTR | 175 | 59 | 2.39 (1.55 – 3.67) | <0.001 | |

| Age | 50–64 | 337 | 71 | ||

| >=65 | 67 | 24 | 1.7 (1.07 – 2.72) | 0.026 | |

| Patient sex | Male | 208 | 52 | ||

| Female | 196 | 43 | 0.86 (0.56 – 1.32) | 0.49 | |

| Performance score | <90% | 180 | 41 | ||

| 90–100% | 224 | 54 | 1.2 (0.78 – 1.85) | 0.41 | |

| GvHD prophylaxis | CNI + MMF | 96 | 32 | ||

| CNI + MTX | 210 | 47 | 0.69 (0.43 – 1.11) | 0.13 | |

| Other | 98 | 16 | 0.54 (0.29 – 1.01) | 0.054 | |

| Regimen | non-TBI regimen | 303 | 62 | ||

| TBI regimen | 101 | 33 | 0.96 (0.55 – 1.67) | 0.87 | |

| Donor | Identical sibling | 209 | 35 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 195 | 60 | 2.01 (1.18 – 3.42) | 0.011 | |

| Graft source | Bone marrow | 220 | 53 | ||

| Peripheral blood | 184 | 42 | 0.94 (0.62 – 1.42) | 0.78 | |

| Interval diag-Tx (yrs) | 404 | 1.06 (1 – 1.12) | 0.033 | ||

| Chronic GvHD | N | N-event | sHR (95% CI) | p | |

| Total | 315 | 98 | |||

| Registry | EBMT | 143 | 38 | ||

| CIBMTR | 172 | 60 | 1.3 (0.85 – 2.01) | 0.23 | |

| Age | 50–64 | 261 | 77 | ||

| >=65 | 54 | 21 | 1.2 (0.74 – 1.97) | 0.46 | |

| Patient sex | Male | 155 | 54 | ||

| Female | 160 | 44 | 0.84 (0.56 – 1.26) | 0.4 | |

| Performance score | <90% | 142 | 42 | ||

| 90–100% | 173 | 56 | 1.11 (0.72 – 1.7) | 0.64 | |

| GvHD prophylaxis | CNI + MMF | 76 | 38 | ||

| CNI + MTX | 166 | 48 | 0.52 (0.33 – 0.81) | 0.004 | |

| Other | 73 | 12 | 0.27 (0.14 – 0.53) | <0.001 | |

| Regimen | non-TBI regimen | 229 | 70 | ||

| TBI regimen | 86 | 28 | 0.94 (0.51 – 1.75) | 0.85 | |

| Donor | Identical sibling | 158 | 47 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 157 | 51 | 1.11 (0.65 – 1.88) | 0.71 | |

| Graft source | Bone marrow | 179 | 49 | ||

| Peripheral blood | 136 | 49 | 1.31 (0.85 – 2) | 0.22 | |

| Interval diag-Tx (yrs) | 315 | 1.03 (0.96 – 1.1) | 0.46 | ||

The 3-year incidence of chronic GVHD were 49% (39–59%) with CNI+MMF, 31% (24–38%) with CNI+MTX and 18% (9–26%) with CNI alone or other GVHD prophylaxis (p<0.001), see Figure 1D. The only risk factor associated with chronic GVHD was GVHD prophylaxis regimen. Risks were lower with CNI + MTX (sHR 0.52 (0.33–0.81), p=0.004) and CNI alone or other agents (HR 0.27 (0.14–0.53), p<0.001) compared to CNI + mycophenolate.

Discussion

Reported here is the first global study evaluating outcomes after matched related and matched unrelated donor HCT for SAA patients aged ≥ 50 years including 79 patients who were aged between 65–77 years. Patients undergoing second transplant were excluded from this study, making the data more specific, and providing more accurate interpretation of graft failure, especially late graft failure. The current analyses support allogeneic transplantation as an acceptable treatment option for older adults who fail IST with careful attention to patient selection. The upper age limit for upfront matched related HCT has been steadily rising over time as outcomes continue to improve. A cut-of 35–50 years has been recommended, depending on patient co-morbidities 2, although more recently for patients aged 41–60 years it has been suggested that upfront transplantation might be carefully considered in selected patients who are medically fit 8. Otherwise first line treatment for older patients is IST. In older patients who lack a HLA-matched related donor, HLA-matched unrelated donor HCT is only offered after failure to respond to IST.

We have shown that the 3-year survival exceeds 50% after related and unrelated donor HCT. Although unrelated donor HCT was independently associated with worse survival the availability of a matched sibling is not a modifiable factor. Optimizing patient selection by considering referral after failure of one course of IST, and initiation of donor search at diagnosis, for those who are “fit” with good performance score may mitigate mortality risks. We were not able to assess HCT-CI scores due to a lack of available data. We also examined for any interaction between performance status and age on clinical outcomes, to demonstrate their separate effects (See Supplemental File). Both acute and chronic GVHD were exceptionally low with alemtuzumab-containing conditioning regimens. Although patient numbers are small (60 patients received alemtuzumab-containing regimens), considering transplant strategies that include alemtuzumab may help lower the burden of morbidity and perhaps late mortality although mortality within the first three years after HCT was not associated with use of alemtuzumab. The other potential benefits of alemtuzumab instead of ATG, are that addition of methotrexate to a CNI is not required thus eliminating the risk of mucositis, reducing the risk of hepatotoxicity and avoiding TBI containing regimens even for unrelated donor HCT. Additionally, PBSC can be used with alemtuzumab due to very low GVHD with the added benefit of a higher incidence of engraftment 16,17.

Other studies that have studied the effect of donor type (younger unrelated donor or older sibling) have limited the unrelated donor transplant recipients to those who received grafts from a young unrelated donor 18. With the additional limitation of the unrelated donor transplant recipients to HLA-matched transplants the study population was not adequately powered to detect differences in survival based on donor age.

The question of one versus multiple prior courses of IST was not addressed in the current analyses, since these data, along with number of prior transfusions, are not routinely captured in this registry-based retrospective study. Survival after IST is age dependent with worse survival among older patients compared to younger patients. A retrospective EBMT study of 242 patients aged >50 years reported 5-year survival of 57% for patients aged 50–59 years and 50% for ≥60 years 3. A subsequent prospective randomised EBMT study of first line ATG and cyclosporine with or without GCSF showed that for patients aged >60 years the 3 and 6-year overall survival was 65% and 56%, respectively 19. In a national study from Sweden, 5-year survival for patients aged ≥60 years treated with IST from 2000–2011 was 52% 13. Thus, the survival after HLA-matched related HCT is comparable to that following IST therapy in this older age group. Other factors to consider with IST in older patients are, for example, that unlike in a younger population, use of ATG in older patients is associated with arrhythmia, cardiac failure and sudden cardiac ischaemic events all of which adds to the burden of morbidity and mortality 5. The next question is how survival after HLA-matched HCT compares to a second course of IST with ATG and CSA or other IST such as alemtuzumab. Hematologic response occurs in only 30–40% of patients of all age groups following a second course of IST given for refractory SAA 10, 20. We are not aware of any published data on response or survival after two or more courses if IST among older patients, although the retrospective EBMT study found that repeat courses of IST had no significant impact on survival 3. Additionally, MDS/AML and solid tumours may occur in 15% and 11% of patients, respectively at 10 years after IST, and multiple courses of ATG increase the risk of developing MDS/AML 11,21,22.

Others have used CSA as mono-therapy but response rates are lower than with the addition of ATG 23,24. The use of eltrombopag for refractory SAA has improved response rates to 40% but the early risk of clonal cytogenetic abnormality is 19% (median time to cytogenetic abnormality was 3 months) and monosomy 7 was the most common 12. Taken together, in fit older patients with a suitable HLA-matched sibling or unrelated donor, transplantation after failure of one course of IST may be an alternative treatment option. Long-term survival after HCT for SAA is excellent and the predominant cause of late mortality was GVHD-associated death, which in the recent era may be mitigated with alemtuzumab containing regimens 17,18.

The incidence of, and indication for, allogeneic HCT in older patients with hematologic disorders are increasing worldwide 25, concurrent with improved clinical outcomes, an increased risk of hematologic malignancies 26, and a rising aged population globally. This is mirrored by a steady increase in the number of transplants being performed for SAA over the last decade, especially unrelated donor HCT (Figure 2). The question as to whether patient age remains relevant has been recently debated for hematologic malignancies 27. Although we failed to detect a significant difference in survival between those aged 50 – 64 and 65 years or older this should be interpreted with caution as the latter group accounted for only 16% of transplantations in the current analyses.

Figure 2. Factors affecting GVHD.

Figure 2A shows acute GVHD incidence by age and Figure 2B chronic GVHD incidence by age. Figure 2C shows acute GVHD incidence by GVHD prophylaxis, and Figure 2D shows chronic GVHD incidence by GVHD prophylaxis. The shaded regions indicate the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Reported p-values are based on Gray’s test. Of 116 patients who received CNI + other, 50 (43%) received alemtuzumab-based conditioning

A further consideration is that, for any patient age group, if HCT is deferred until after the development of MDS/AML, outcome of HCT are inferior 28,29. Prior to consideration of HCT in older patients with SAA, and at time of diagnosis, it is important to exclude hypocellular MDS, that may frequently mimic SAA on morphological grounds 30. MDS is far more common than SAA in older patients, with a median age of onset of MDS is 62 years. A diagnosis of MDS instead of SAA would impact on choice of conditioning regimen for HCT. Metaphase cytogenetics may not be discriminating as up to 12% of SAA patients have an abnormal cytogenetic clone at diagnosis 31. Even the presence of an acquired somatic mutation that is recurrent for MDS/AML such as ASXL1 or DNMT3A does not necessarily prove a diagnosis of hypocellular MDS instead of SAA, as small clones can be found in some SAA patients 10,32 as well as in normal older individuals as part of age-related clonal hematopoiesis 33–35.

We conclude that HCT deserves consideration as an option in older patients with SAA who have failed first line IST. Better survival in patients with good performance score emphasizes the critical importance of pre-assessment of patients in terms of co-morbidities. This will aid discussions with the patient about a potentially curative disease approach rather than disease-free survival associated with non-transplant options.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3. Number of transplants.

Number of transplants performed each year of the study by donor type: HLAidentical sibling and unrelated donor

Highlights.

The first global study of HCT for SAA in older patients

Age does not impact on survival

Choice of GVHD prophylaxis and performance score impact on outcomes

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); grants N00014-15-1-0848 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Artz AS. Biologic vs physiologic age in the transplant candidate. Hematology. 2016; 99:105–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Killick SB, Brown N, Cavenagh J, et al. British Society for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Brit J Haematol. 2016;172(2):187–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tichelli A, Socie G, Henry-Amar M, et al. Effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy in older patients with aplastic anemia. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 130(3):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tichelli A, Marsh JC. Treatment of aplastic anaemia in elderly patients aged >60 years. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013; 48(2):180–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao SY, Xu W, Brandwein JM, et al. Outcomes of older patients (> or = 60 years) with acquired aplastic anaemia treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Brit. J. Haematol. 2008; 143(5): 738–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta V, Eapen M, Brazauskas R, et al. Impact of age on outcomes after bone marrow transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia using HLA-matched sibling donors. Haematologica. 2010; 95(12): 2119–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sangiolo D, Storb R, Deeg HJ, et al. Outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings for severe aplastic anemia in patients over 40 years of age. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16(10):1411–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacigalupo A How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017; 129(11): 1428–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin SH, Jeon YW, Yahng SA, et al. Comparable outcomes between younger (≤40 years) and older (> 40 years) adult patients with severe aplastic anemia after HLA-matched sibling stem cell transplantation using fludarabine-based conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016; 51(11): 1456–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulasekararaj AG, Jiang J, Smith AE, et al. Somatic mutations identify a subgroup of aplastic anemia patients who progress to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2014; 124(17): 2698–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socié G, Henry-Amar M, Bacigalupo A, et al. Malignant tumors occurring after treatment of aplastic anemia. European Bone Marrow Transplantation Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(16):1152–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desmond R, Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, et al. Eltrombopag restores tri-lineage hematopoiesis in refractory severe aplastic anemia which can be sustained on discontinuation of drug. Blood. 2014; 123(12): 1818–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaht K, Göransson M, Carlson K, et al. Incidence and outcome of acquired aplastic anemia: real-world data from patients diagnosed in Sweden from 2000–2011. Haematologica. 2017; 102(10):1683–1690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flowers ME, Kansu E, Sullivan KM. Pathophysiology and treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;(5):1091–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh JC, Gupta V, Lim Z, et al. Alemtuzumab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide reduces chronic graft versus host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011; 118(8): 2351–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh JC, Pearce RM, Koh MB, et al. , on behalf of the British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (BSBMT) Clinical Trials Committee (CTCR 09–03). Retrospective study of alemtuzumab versus ATG based conditioning without irradiation for unrelated and matched sibling donor transplants in acquired severe aplastic anaemia: a study from the British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (BSBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014; 49(1):42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollman C, Spellman SR, Zhang MJ, et al. The effect of donor characteristics on survival after unrelated donor transplantation for hematologic malignancy Blood. 2016; 127(2): 260–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tichelli A, Schrezenmeie H, Socie G, et al. A randomized controlled study in patients with newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia receiving antithymocyte globulin (ATG), cyclosporine, with or without G-CSF: a study of the SAA Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2011; 117(17), 4434–4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, Scheinberg P, Wu CO, Young NS. Activity of alemtuzumab monotherapy in treatment-naive, relapsed, and refractory severe acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2012; 119(2): 345–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenfeld S, Follmann D, Nunez O, Young NS. Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for severe aplastic anemia: association between hematologic response and long-term outcome. JAMA. 2003; 289(9):1130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frickhofen N, Heimpel H, Kaltwasser JP, Schrezenmeier H. German Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Antithymocyte globulin with or without cyclosporin A: 11-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing treatments of aplastic anemia. Blood. 2003; 101(4):1236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsh J, Schrezenmeier H, Marin P et al. Prospective randomized multicenter study comparing cyclosporin alone versus the combination of antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporin for treatment of patients with nonsevere aplastic anemia: a report from the European Blood and Marrow Transplant (EBMT) Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party. Blood. 1999; 93(7), 2191–2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gluckman E, Esperou-Bourdeau H, Baruchel A, et al. Multicenter randomized study comparing cyclosporine-A alone and antithymocyte globulin with prednisone for treatment of severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 1992; 79(10):2540–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muffly L, Pasquini MC, Martens M, et al. Increasing use of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients aged 70 years and older in the United States. Blood. 2017;130(9):1156–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, et al. HAEMACARE Working Group. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood. 2010; 116(19):3724–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuckerman T Allogeneic transplant: does age still matter? Blood. 2017; 130(9): 1079–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussein AA, Halkes CM, Socié G, et al. ; Severe Aplastic Anemia and Chronic Malignancies Working Parties of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients transformed to myelodysplastic syndrome or leukemia from severe aplastic anemia: a report from the MDS Subcommittee of the Chronic Malignancies Working Party and the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(9):1448–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SY, Le Rademacher J, Antin JH, et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome evolving from aplastic anemia treated with immunosuppressive therapy: efficacy of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2014; 99(12):1868–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett JM, Orazi A Diagnostic criteria to distinguish hypocellular acute myeloid leukemia from hypocellular myelodysplastic syndromes and aplastic anemia: recommendations for a standardized approach. Haematologica. 2009; 94(2), 264–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanley N, Olson TS, Babushok DV. Recent advances in understanding clonal haematopoiesis in aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2017; 177(4):509–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anaemia. N. Eng. J. Med 2015; 373(1):35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med 2014:25;371(26):2488–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2015; 126(1): 9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bono E, McLornan DP, Travaglino E, et al. Hypoplastic myelodysplastic syndrome: combined clinical, histopathological and molecular characterization. Blood. 2017; 130 (suppl 1):588 Annual Scientific Meeting of American Society Hematology abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.