Abstract

Membrane nanotubes, also known as membrane tethers, play important functional roles in many cellular processes, such as trafficking and signaling. Although considerable progresses have been made in understanding the physics regulating the mechanical behaviors of individual membrane nanotubes, relatively little is known about the formation of multiple membrane nanotubes due to the rapid occurring process involving strong cooperative effects and complex configurational transitions. By exerting a pair of external extraction upon two separate membrane regions, here, we combine molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical analysis to investigate how the membrane nanotube formation and pulling behaviors are regulated by the separation between the pulling forces and how the membrane protrusions interact with each other. As the force separation increases, different membrane configurations are observed, including an individual tubular protrusion, a relatively less deformed protrusion with two nanotubes on its top forming a V shape, a Y-shaped configuration through nanotube coalescence via a zipper-like mechanism, and two weakly interacting tubular protrusions. The energy profile as a function of the separation is determined. Moreover, the directional flow of lipid molecules accompanying the membrane shape transition is analyzed. Our results provide new, to our knowledge, insights at a molecular level into the interaction between membrane protrusions and help in understanding the formation and evolution of intra- and intercellular membrane tubular networks involved in numerous cell activities.

Introduction

Biological membranes, essential for the compartmentalization of cells and organelles, could form tubular structures and membrane networks in cellular environments and play functional roles in a variety of cellular activities such as intra- or intercellular transport and signaling (1, 2, 3, 4). Understanding how membrane nanotubes are formed and evolve is important for revealing the biophysical mechanism underlying these biological processes. For example, tubular membrane structures were constructed and served as a biomimetic nanoscale environment for measuring the confined enzyme reaction kinetics and the transport of biomolecules therein (5, 6). In cellular environment, membrane nanotubes are formed by a pulling force exerted by actin polymerizing toward the membrane or motor proteins grabbing the membrane and moving along microtubules (7). Such processes can be reproduced by in vitro experiments in which tubular membrane protrusions were generated by the application of external forces using micropipettes (8, 9, 10), optical tweezers (11), and by the cooperative movement of motor proteins (12) and polymerizing microtubules (13) on an in vitro minimal system based on vesicles. Moreover, the mechanical manipulation of the membrane nanotube can be employed to measure the bending rigidity of plasma membranes (14, 15), investigate coupling between lipid sorting and membrane curvature (16, 17), and analyze the tube pearling instability (18, 19). Because of substantial research effort combining experimental, theoretical, and computational studies, the underlying mechanism of individual membrane nanotube formation has become relatively well understood (8, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24).

In biological conditions, membrane nanotubes are rarely isolated and could form branched networks or interacting tubules as widely observed in the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, intracellular tunnels, and actin-based protrusive organelles (1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 25, 26, 27). For example, cells rely on an elaborate tubular membrane network in Golgi apparatus to transport proteins inside the cell. Neighboring filopodia at the leading edge of migrating cells experience attractive interactions and could merge to form a larger filopodium (25). A three-way Y-shaped nanotube junction could be formed connecting three murine macrophage cells, with the angles between adjacent lipid branches at 120° (26). Similar networks of membrane nanotubes have also been constructed in artificial vesicle networks with bio-nanotechnological implications such as the directed transport of colloidal particles and membrane components between vesicles (9, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32). In these in vitro experiments, the coalescence of membrane nanotubes as well as a subsequent V to Y membrane shape transition has been observed (9, 28, 29) and quantitatively described (29, 31, 32). However, in these experiments, the nanotubes were extracted successively from separate regions of a giant vesicle and then slid over the vesicle surface to coalesce (9, 28, 29, 31). Therefore, the interaction between two early membrane protrusions before tubulation could not be captured in these in vitro experiments. Compared to the extensive quantitative studies on the underlying physics of the individual tether formation, only few theoretical and experimental studies (20, 29, 31) and no simulations at a molecular level have been performed to investigate the formation of multiple membrane protrusions or nanotube bundles as well as the subsequent nanotube interaction as a function of the protrusion separation. These fundamental but still elusive issues call for dedicated studies aimed at understanding and explicitly modeling the mechanical behaviors and configurational evolution of interacting membrane protrusions.

In this study, we presented the first, to our knowledge, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and theoretical modeling to reveal the physics of the formation and interaction of membrane protrusions pulled from a lipid membrane. We investigated how the pulling behaviors and membrane configurations are regulated by the separation between pulling forces and how the lipid molecules flow during the significant membrane deformation. Depending on the pulling displacement and the separation between two pulling regions, we found several representative membrane configurations, such as the membrane with protruding precursors, an individual tubular protrusion, V-shaped nanotubes on the top of a weakly deformed protrusion, a Y-shaped nanotube configuration through coalescence, and weakly interacting tubular protrusions. We also theoretically estimated the energy profile and the associated membrane configuration evolution as a function of the pulling separation, consistent with our MD simulations.

Methods

Pulling multiple tethers from a single membrane requires a large membrane patch and long simulation time which, however, are difficult to be achieved using the regular coarse-grained (CG) method involving explicit water molecules (23, 33). To tackle this problem, some CG solvent-free simulation models have been proposed for the study of membrane remodeling at larger scales (34, 35). Here, we used the dry Martini CG force field (36), which is an implicit solvent variant of the wet Martini and inherits some basic features of the standard version (33). Because considerable computational efforts on calculating interactions involving solvent molecules are excluded, using the dry Martini CG method permits simulations to be performed for studying the mechanical behaviors of a lipid membrane of 105–107 lipid molecules and in a long simulation period of time. In our simulations, the initial structure of the membrane was constructed by arranging 6.55 × 104 dioleoylphosphatidylcholine molecules in a lipid bilayer of a lateral size 150 × 150 nm2 (Fig. S1 a) via VMD (37).

All simulations were performed using the second-order stochastic dynamics integrator with the consideration of the friction force in the Langevin equation. The temperature was fixed at 310 K with a friction constant of 0.25 ps−1. The Parrinello-Rahman barostat was used to control the pressure in the bilayer systems simulated with the semi-isotropic pressure coupling (38). The simulation box was fixed in the direction normal to the bilayer surface by setting the vertical compressibility to be 0 bar−1. The membrane was made tensionless by setting the reference pressure in the bilayer plane to be 0 bar with a time constant τp = 4.0 ps. The lateral compressibility of the membrane was 3 × 10−4 bar−1. The dry Martini simulations used the same interaction cutoff scheme as the standard Martini simulations with explicit solvent (33). A cutoff of 1.2 nm was used for van der Waals interactions. The Lennard-Jones potential was smoothly shifted to zero between 0.9 and 1.2 nm. The Coulomb potential with a cutoff of 1.2 nm was smoothly shifted to zero from 0 to 1.2 nm. No bond constraints were used in the simulations. After energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm, the system was relaxed for 1.0 ns with the NVT ensemble and then relaxed for another 50 ns with the NPT ensemble. It is found that the lipid area rapidly increased from 0.6 to 0.67 nm2 in less than 5 ns and kept nearly unchanged in the rest simulation time (Fig. S2 a). The membrane tension kept fluctuating around zero (Fig. S2 b), suggesting that the membrane has reached an equilibrium tensionless state (Fig. S2 c). The time step of simulations was 20 fs, and the neighbor list was updated every 10 steps. Note that the update frequency of 10 was commonly used in membrane simulations to increase the computational efficiency. However, it should be noted that choosing different neighbor list update frequencies may influence simulation results especially when treating systems containing pores and channels to avoid an artificial unidirectional flow (39). Besides, lipid molecules are more mobile in MD simulations with implicit solvent, thus requiring caution to choose the appropriate value of the update frequency. To check whether the frequency of 10 used in our simulations is sufficient, we choose one representative case and repeat the simulations at a smaller frequency of five. All simulations were performed using GROMACS 4.6.7 (40). Snapshots were rendered by VMD (37). More details of our simulation system setup and method can be found in Supporting Materials and Methods, Section 1.

In addition to the MD simulations, we performed quasistatic theoretical estimate to analyze the mechanical behaviors and configurational transitions of the membrane protrusion at the adjacent and intermediate separations of the pulling regions. By adopting the Helfrich membrane theory (41), the membrane configuration at a certain pulling displacement was determined by minimizing the membrane energy E, depending on the membrane bending rigidity κ, membrane tension σ, local mean curvature H, and membrane surface area S. Similar numerical schemes have been employed to investigate the size-dependent membrane extraction (24) and the cellular packing of one-dimensional nanomaterials (42, 43, 44). Details on the energy calculation and model assumptions can be found in Supporting Materials and Methods, Section 3.

Results and Discussion

Membrane protrusion induced by a single pulling force

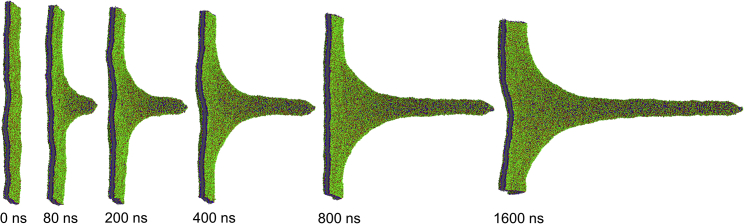

We first examined the formation of an individual membrane nanotube by exerting a pulling constant force of 200 kJ/mol/nm on a circular lipid patch of r = 6 nm in radius in the central region of a tensionless dioleoylphosphatidylcholine membrane (Fig. S1 b). Fig. 1 depicts the process of individual tether formation on a microsecond timescale (the corresponding dynamic process can be found in Video S1). Combining evolutions of both the tether length and the pulling velocity (Fig. S3), the membrane evolved from the configuration of a shallow protrusion adopting a linearized catenoidal shape with an almost zero mean curvature and transformed to a tubular configuration undergoing elongation with its base connecting a catenoid-like outer membrane region, in agreement with previous experimental results, theoretical prediction, and simulations (20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 42, 43).

Figure 1.

Pulling an individual membrane tether from the lipid membrane by exerting a constant force of 200 kJ/mol/nm on a circular lipid patch of r = 6 nm in radius. To see this figure in color, go online.

Force barriers exist for the formation of tethers, as measured experimentally and confirmed with theoretical calculations and simulations (11, 12, 20, 21, 22, 24). Our simulations manifested the force barriers because the pulling force below a threshold value failed to generate membrane tethers, and only a cone-shaped membrane protrusion was formed (Fig. S4). A further shape transformation of the membrane from the weakly deformed configuration to a cylindrical nanotube requires overcoming a finite force barrier arising from both the membrane bending and the membrane stretching. Once a tubular structure was generated, it could elongate smoothly and almost linearly (Fig. S3), suggesting that the external pulling force was balanced by the membrane resistance force.

From a theoretical point of view, the tubular membrane structure can be approximated as a long bilayer tubular structure. For a cylindrical tensionless lipid membrane tube of radius r0, the axial force F under the condition of a fixed area obeys a simple relation as , where κ is the bending rigidity of the fluid-phase lipid membrane (15, 20, 21, 45). Based on this simple relation, κ can be successfully determined from an analysis of the membrane thermal undulation modes in MD simulations (15, 45). Moreover, the membrane bending rigidity κ can also be estimated by simulating the buckling of a membrane stripe (46, 47). Note that, unlike the fluid-phase counterparts, gel-phase lipid membranes could exhibit quite different mechanical behaviors that cannot be well captured by the Helfrich membrane theory (48).

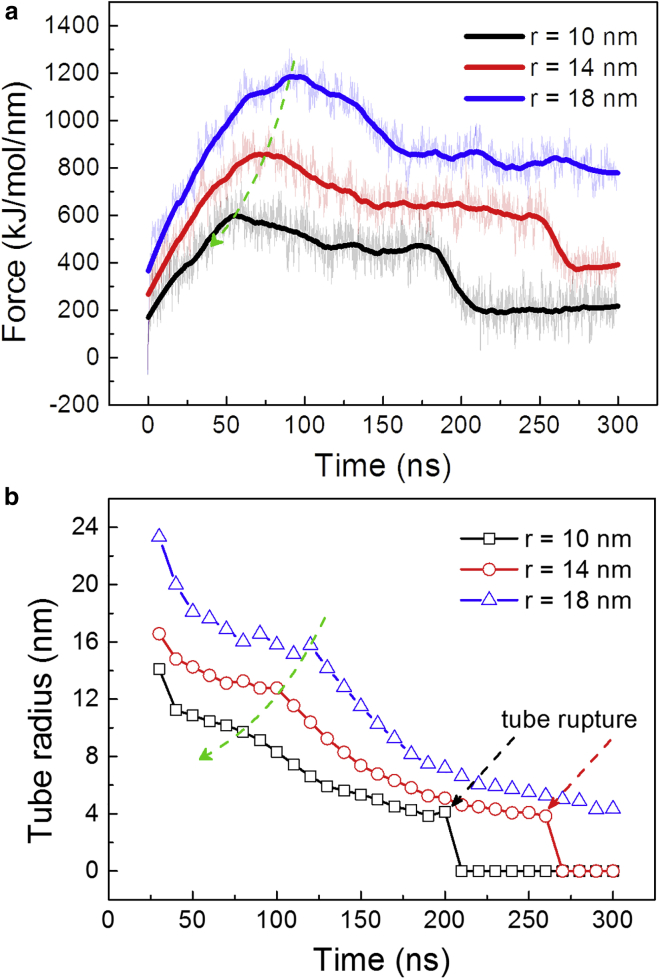

To investigate size effect of the pulling regions on the formation of individual membrane tethers, we performed simulations at three different region sizes (r = 10, 14, and 18 nm). A constant pulling velocity of 0.5 nm/ns was imposed by setting the force constant as 1000 kJ/mol/nm2. Shown in Fig. 2 a are the force-time curves at different values of r. The pulling force first increases almost linearly with the pulling displacement in the early extraction stage and then gradually reaches to a peak followed by a drop to a steady-state value upon the formation of a membrane nanotube.

Figure 2.

Effect of the patch radius on the tether formation. (a) Time evolutions of the pulling force on the membrane protrusion at different sizes r of the pulling region are shown. (b) The shortest tube radius as a function of the simulation time depicting the tether development is shown. The force constant was fixed at 1000 kJ/mol/nm2, and the pulling velocity was 0.5 nm/ns. To see this figure in color, go online.

The difference between the force peak and the steady-state force was defined as the overshoot force. Previous theoretical analysis on the tether formation in the quasistatic modeling indicated that the force peak in the case of a localized point pulling force was around 13% larger than the steady-state force (20, 21), and the relative difference increased with the size of the regions on which the pulling force was exerted (22, 24). These results were consistent with our MD simulations, which indicated that the ratio between the overshoot force and the steady-state force became larger as r increased (Fig. 2 a). Moreover, the force peak was achieved earlier for pulling a smaller membrane region. As shown in Fig. S5, both the force peak and the steady-state force increased linearly with the pulling region size, in agreement with the experimental measurement, indicating that pulling larger regions costs higher membrane bending and stretching energies (22).

Note that the pulling velocity plays an important role in regulating the evolution of the pulling force. At a much smaller pulling velocity of 0.1 nm/ns, the membrane has more time to respond to the pulling action, and the pulling force decreases significantly (Fig. S6 a). Moreover, the effect of the pulling region size on the pulling force evolution becomes minor (Fig. S6 b) in comparison with the results in Fig. 2 a at the pulling velocity of 0.5 nm/ns. On the other hand, lipids in the selected membrane patch could freely diffuse, especially along the vertical direction, thus allowing the finite patch deformation under the external pulling force. By analyzing the evolution of the patch deformation in terms of the difference between the highest and lowest positions of the patch, we found that in the case of a given patch size, the nanotube length exhibited a linear relation with the time, and the thickness of the selected lipid patch increased linearly first and then saturated at a certain value (Fig. S7 a). This behavior suggests that the finite patch deformation mainly affected the tether formation and force evolution in the early extraction stage. Similar behaviors of the patch deformation were observed at a lower pulling velocity of 0.1 nm/ns, except that the patch thickness increased more slowly and reached a steady value later (Fig. S7 b).

Upon the formation of the membrane nanotubes, the tube elongation is accomplished via a flow of lipids from the basal membrane into the tether structure. At a high pulling velocity, the overstretching would increase the local membrane tension and consequently lead to a large force barrier (Fig. 2 a). A tube shrinkage was observed helping release the membrane surface energy (Fig. 2 b). If the increase of the local membrane surface energy cannot be compensated by the tube shrinkage, the shrinking tube would undergo rupture at its tip. As shown in Fig. S8, the tube rupture was initiated by a transformation from a tubular to a micellar structure, resembling the fission of vesicles. By decreasing the pulling velocity to 0.1 nm/ns, the force barrier was reduced, and no tube rupture was observed in a microsecond timescale simulation (Fig. S9). In experimental systems, the contribution of tension increase is less important because of the lower pulling velocity being applied and the presence of lipid reservoirs helping regulate the membrane tension (49). Note that no apparent difference in either the pulling force or the tube radius was observed when a smaller neighbor list update frequency of five was used in the simulations (Fig. S10), suggesting that the frequency of 10 used in our simulations is sufficient to reproduce the mechanics and dynamics of the membrane nanotube formation.

Membrane protrusion and configurational transformation by two pulling forces

As demonstrated in Fig. 1 and in previous studies in the literature (20, 21, 22, 23, 24), the outer region of the membrane subject to an external pulling force adopted a curved catenoid-like shape with a strong local deformation in the vicinity of the pulling region. In the case of two parallel external pulling forces approaching one another, such local membrane deformation gave rise to indirect curvature-mediated interactions between them. Consequently, these two pulling forces jointly affected both the force barrier and the final equilibrium tubular network structures as demonstrated below by our simulations (Fig. 3). Different from existing experimental studies on the evolution of tubular networks in which membrane nanotubes were formed before measuring their mechanical responses to external mechanical manipulation, in our simulations, there were no preexisting membrane nanotubes, and we focused on the integrated process involving the formation, evolution, and interaction of membrane protrusions by exerting two pulling forces on an initially flat lipid membrane, mimicking tubular structure formation and interaction occurring ubiquitously in cell activities such as cellular transport and communications.

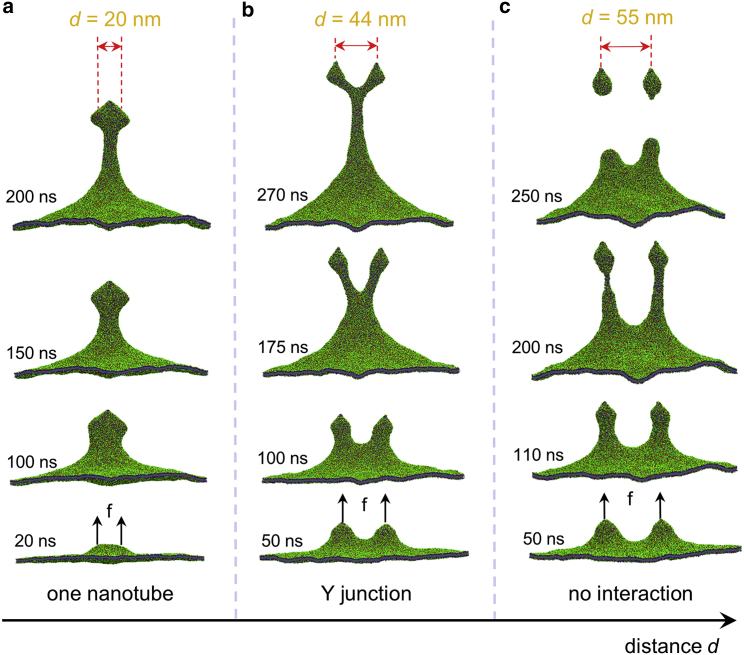

Figure 3.

Structural evolution of the membrane protrusion at different separation d between two pulling forces f (side view). d = 20 nm (a), 44 nm (b), and 55 nm (c). The radius r of each pulling region was 10 nm, and the pulling velocity was 0.5 nm/ns with a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Here, two groups of lipids belonging to different circular patches of radii r = 10 nm were selected and pulled at a constant velocity of 0.5 nm/ns (Fig. S1 c). The distance d between centers of these two circular pulling regions varied from 20 to 55 nm (Fig. 3). At a limiting case of d = 20 nm, two circular pulling regions were adjacent to each other, and only a single membrane tether was induced (Fig. 3 a), resembling pulling the membrane upon a larger region. Because the entire circumference of two adjacent pulling regions had a noncircular shape, the cross section of the early protruding structure at the middle height was elliptic, which gradually transited to a circular shape to reduce the membrane elastic bending energy (Fig. S11 a). In comparison with the case of a single pulling region (Fig. 2 a), we found that the overshoot force on one pulling region in the case of two adjacent pulling regions (d = 20 nm) was reduced by 50 kJ/mol/nm and delayed by 15 ns (Fig. S11 b). This is consistent with the quasistatic analysis on the formation of a single membrane tether in Fig. S11, c and d, which indicated that the peak force in the case of a larger circular pulling region, approximately mimicking the two adjacent regions in the simulations, was delayed to a larger pulling displacement and the corresponding force per pulling area was smaller (Fig. S11 c).

Another limiting case was that the two pulling regions were far apart from one another, and their interaction mediated by the membrane deformation was inconsiderable, leading to two individual membrane protrusions. In our case study at d = 55 nm, two individual membrane nanotubes were generated (Fig. 3 c), and the evolution of the pulling force on each pulling region almost coincides with that in the case of a single pulling region except the segments around peak forces (Fig. S12). As shown in Fig. 3 c, the membrane portion between these two protrusions exhibited a height significantly higher than that of the remote membrane boundary, which indicated that these two membrane nanotubes were stretched vertically in a smaller extent than that upon a single pulling force. Therefore, a smaller peak force could be expected at d = 55 nm (Fig. S12). These results implied that there existed the interaction between membrane protrusions around d/r = 5.5, but it played a negligible role in regulating the membrane nanotube formation.

At the intermediate separation (d = 44 nm; Figs. 3 b and 4), the membrane-mediated interaction played a key role in regulating the process of the membrane protrusion, including coalescence of tubular structures, a V- to Y-shape transition of the lipid nanotubes, and the Y-junction propagation with a zipper-like mechanism (the corresponding dynamic process can be found in Video S2). As lipid molecules underwent free lateral movement in the membrane, the membrane nanotube formation and interaction at a molecular level were expected to be accompanied with directed lipid flow. To gain insight into the underlying physics of that complex process at a molecular level, MD simulations were performed not only demonstrating the nanotube interaction (Fig. 3 b) but also enabling us to reveal the membrane protrusion dynamics (Fig. 4).

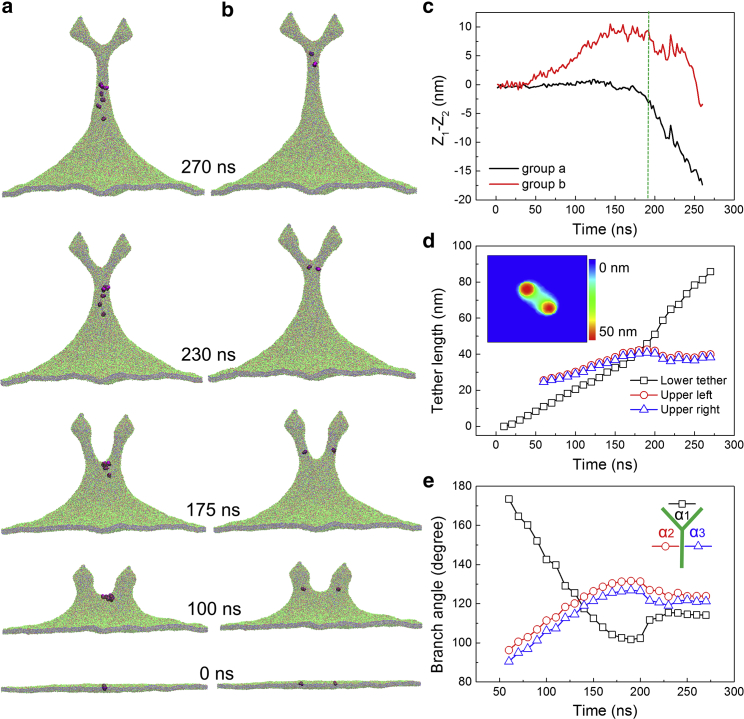

Figure 4.

Dynamics of the membrane protrusion at the pulling force separation d = 44 nm. Serving as tracer particles to determine the direction of lipid flow during the membrane protrusion, two groups of lipid molecules were selected: (a) lipids belonging to the membrane region between two pulling patches and (b) lipids close to the two circular patches. (c) Time evolutions of the position of tracer lipids (Z1) relative to the top of the saddle membrane surface (Z2). (d and e) Time evolutions of the lengths of three lipid branches formatting the Y junction (d) and the intersecting angles (e) are shown. The inset in (d) represents the membrane height contour at 50 ns. To see this figure in color, go online.

As shown in Fig. 3 b, two protruding precursors first emerged upon the pulling forces (50 ns) and then elongated into short tubular structures (100 ns) between which the membrane adopted a saddle-like shape (Fig. 4 d, inset). Upon further pulling, the catenoidal outer membrane region and these two tubular structures became slender radically and elongated vertically (175 ns). Meanwhile, the size of the saddle region decreased, and two tube bases gradually approaching one another merged. Consequently, two lipid branches were observed to form a V-shaped configuration (175 ns). Further merging of the lipid nanotubes resulted in a shape transition from a V to Y configuration in which the upper two nanotubes connected with a newly formed branch linking to the basal membrane. The three-way Y junction immediately after its formation was unstable and propagated toward an equilibrium state (270 ns; Fig. 3 b) via the downward lipid flow from the upper branches through the junction to the lower elongating branch, as the movement of the tracer particles in Fig. 4, a and b indicated. That downward lipid flow was directly reflected by a sudden decrease of the position of tracer particles relative to the top of the saddle membrane surface (Fig. 4 c) and induced respectively a decrease of the upper nanotube length and an increase of the lower branch (Fig. 4 d). Eventually, the Y junction reached its equilibrium state and all the angles between the three cylindrical lipid branches approached 120° (Fig. 4 e). Note that the whole process of configurational transformation of two interacting nanotubes being accomplished via directional flow of lipids is quite similar to the membrane fusion with vesicles (50, 51, 52) in terms of the stress relaxation occurring at the junctional region.

Time evolution of the averaged force on each pulling region could be found in Fig. S13. It shows that the cooperative effect of pulling two tethers manifested as a reduction of the pulling force and the overshoot force was delayed by 20 ns in comparison with the case of a single pulling region. The V- to Y-shape transition and the zipper dynamics of nanotube merging as demonstrated in our simulations were consistent with experimental observations (29, 31). Note that in the experimental studies on the coalescence of two membrane nanotubes, the nanotubes were pulled successively from separate regions of a giant vesicle and then slid over the vesicle surface to coalesce by moving the vesicle away (9, 28, 29, 31). Therefore, in the case of Y-junction formation (Fig. 3), the membrane protrusion interaction in the early stage of the membrane extraction before the nanotube formation was not captured in experiments.

As demonstrated in Figs. 3 and 4, a and b and indicated in Fig. 4 e, a three-way nanotube Y junction was formed at a large pulling displacement and intermediate separation, with the intersecting angles between nanotube branches at 120°. Similar Y-shaped junctions with angles at 120° were widely observed in the artificial vesicle system and biological conditions (3, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 53). Different from the Y junction in the simulations whose nanotube branches did not adopt an ideal cylindrical shape because of the boundary effect and limited numbers of lipid molecules, in experiments, tubular branches forming the Y junction are of lengths ranging from several to tens of micrometers and can be regarded as cylindrical membrane nanotubes of a uniform radius r0. For a cylindrical membrane nanotube of bending rigidity κ, membrane tension σ, radius r, and length l, its elastic membrane energy is . Minimizing with respect to r leads to the equilibrium radius (20, 21, 54). Because the deformation energy is linearly proportional to the tube length, the Y junction in equilibrium shall correspond to a configuration of the shortest total tube length. In the case of three vesicles interconnected by a nanotube network, the Y-junction point coincides with the Fermat point of a triangle, a point such that the sum of the distances from this point to each of the three vertices is a minimum. In a given triangle with all angles less than 120°, angles between the line segments connecting the Fermat point to vertices are all 120°. This was observed in the Y junction of the membrane nanotube network (3, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 53). If the triangle has one angle greater than 120°, then the Fermat point lies at the obtuse angled vertex. This has been reflected in the orthogonal pulling of a suspended lipid nanotube, which was first distorted into a V-shaped configuration forming an obtuse triangle with the Fermat point coinciding with the pulling apex (53). At further pulling, a new branch emerged from the apex as the obtuse angle became less than 120°, and a Y junction was formed with its triple point corresponding to the Fermat point (53). For the nanotube network interconnecting more than three vesicles, the optimal network with a minimal elastic energy or the shortest total branch length corresponds to a Steiner minimal tree in geometry (55). Multiple locally optimal configurations could be achieved because the number of the connected vesicle is five or more (53). The Steiner’s minimal tree structure has also been observed in the transportation network of Physarum polycephalum, a slime mold capable of finding the shortest route to locate multiple separate food sources (56).

Theoretical analysis

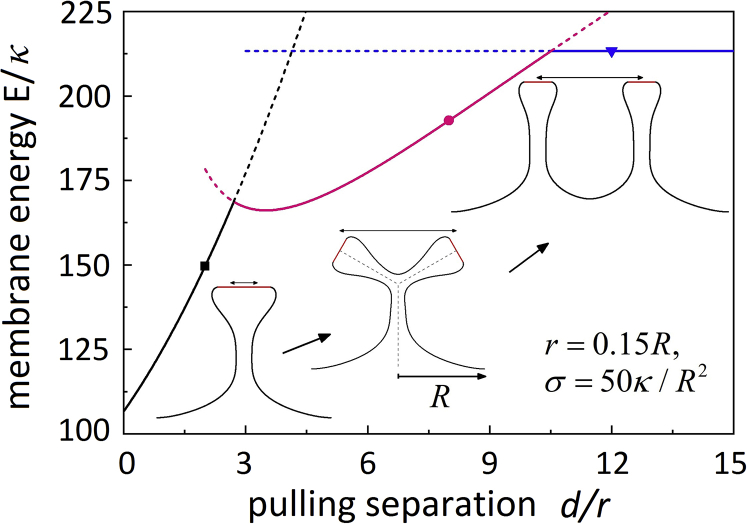

In addition to the MD simulations, we have also performed theoretical analysis at a large pulling displacement to estimate the membrane energy E as a function of the pulling separation d and determine the associated membrane configurational evolution. As shown in Fig. 5, at relatively small d, the configuration of an individual tubular protrusion (black line segment) is adopted. Here, the shape of the pulling region was approximated by a circle of an effective radius r + d/2, and an axisymmetric configuration was assumed as discussed in Supporting Materials and Methods, Section 3. As the separation d increases to an intermediate value, the membrane configuration with a Y junction (pink segment) becomes more energetically favorable than the tubular protrusion. In the Y junction, we assumed that nanotube branches adopted axisymmetric configurations and they connected to a portion of a spherical surface smoothly. The branch radii at the connections were taken to be , the radius of a cylindrical membrane nanotube in equilibrium. The radius of the spherical portion at the junction was taken to be to enable its smooth connections with three branches, and its area is . Therefore, the bending energy of the spherical portion is , and the membrane tension energy is . Adopting the same numerical optimization scheme, the membrane energy of each branch could be determined. Summation of the energy of the branches and spherical portion gives rise to the total energy at an intermediate d. Further increase in d results in two weakly interacting tubular protrusions, with the total energy as twice the energy at d = 0 as assumed. This quantitative approximation at large d is supported by numerical studies on the interaction between two parallel filopodia protruding a membrane vertically (57). Note that in the case of filopodial protrusion, the Y-junction formation is prohibited because of the existence of the enveloped actin bundles beneath the membrane, and the energy profile consists of only the black and blue lines in Fig. 5. A similar energy profile and configurational transition from an individual tubular protrusion to two weakly interacting tubular protrusions have been indicated in (57) on the filopodial interaction. Here, the membrane tension was taken as σ = 50κ/R2. At a smaller membrane tension (σ = 25κ/R2), the two configurational transition points are shifted to slightly larger d (Fig. S14). The shift at the smaller d is confirmed by experimental observations that nanotube coalescence leading to the -junction occurred at a shorter pulling displacement as the membrane tension increased (29). The theoretical estimation in Figs. 5 and S14 consistent with our MD simulations quantitatively present the energy evolution as a function the separation.

Figure 5.

The membrane energy and configurational transition as a function of the separation d at a pulling displacement L/R = 1.5. The insets represent corresponding configurations at the symbols. The configuration in the case of two weakly interacting tubular protrusions (d = 12r) is a schematic plot, whereas the other two are from numerical calculations. The dashed line segments represent the membrane energy of the energetically unstable configurations. Double-headed arrows represent the separation d. Here, the radius of each pulling region is r = 0.15R with R as the radius of the basal membrane, and we assumed that the membrane tension is σ = 50 κ/R2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

In summary, we have performed both MD simulations and theoretical analysis to uncover the underlying mechanism for the formation and interaction of membrane protrusions pulled from a lipid membrane. We demonstrated that a single membrane nanotube could be formed by exerting an external force beyond a critical value proportional to the size of pulling region. Further increase of either the force or the pulling velocity causes the nanotube rupture. By exerting a pair of external extraction, we found that the separation between the pulling forces plays a key role in regulating the membrane nanotube formation and pulling behaviors. At large extraction, the membrane configuration evolves as the separation increases from an individual tubular protrusion to a Y-shaped nanotube configuration then to two weakly interacting tubular protrusions. The corresponding energy profile has been determined. Moreover, the directional flow of lipid molecules accompanying the membrane shape transition was determined. Our results shed light on the physical mechanisms underlying the formation and evolution of tubular networks involved in many cellular processes. In biological environment, a variety of curvature-generating membrane proteins and cytoskeletal filaments exist to modulate the mechanical properties of the cell membrane and affect the membrane nanotube formation and evolution. Further studies on the mechanical behaviors of cell membrane protrusion could take these aspects into account.

Author Contributions

T.Y., X.Y., and X.Z. designed the research. S.L. and Z.Y. performed MD simulations. X.Y. and T.Y. performed theoretical analysis. S.L., Z.Y., Z.L., Y.X., F.H., X.Z., X.Y., and T.Y. analyzed data. S.L, X.Y., and T.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31871012 and 11872005) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (no. ZR2018MC004). Computational resources supported by the High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University is acknowledged. MD simulations were performed at the National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen.

Editor: Ana-Suncana Smith.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, fourteen figures, and two videos are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(19)30082-7.

Contributor Information

Xin Yi, Email: xyi@pku.edu.cn.

Tongtao Yue, Email: yuett@upc.edu.cn.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Terasaki M., Chen L.B., Fujiwara K. Microtubules and the endoplasmic reticulum are highly interdependent structures. J. Cell Biol. 1986;103:1557–1568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustom A., Saffrich R., Gerdes H.H. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science. 2004;303:1007–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1093133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upadhyaya A., Sheetz M.P. Tension in tubulovesicular networks of Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2923–2928. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74343-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watkins S.C., Salter R.D. Functional connectivity between immune cells mediated by tunneling nanotubules. Immunity. 2005;23:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sott K., Lobovkina T., Orwar O. Controlling enzymatic reactions by geometry in a biomimetic nanoscale network. Nano Lett. 2006;6:209–214. doi: 10.1021/nl052078p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jesorka A., Stepanyants N., Orwar O. Generation of phospholipid vesicle-nanotube networks and transport of molecules therein. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:791–805. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee C., Chen L.B. Dynamic behavior of endoplasmic reticulum in living cells. Cell. 1988;54:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derényi I., Koster G., Prost J. Membrane Nanotubes. In: Linke H., Månsson A., editors. Controlled Nanoscale Motion. Springer; 2007. pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans E., Bowman H., Tirrell D. Biomembrane templates for nanoscale conduits and networks. Science. 1996;273:933–935. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shao J.Y., Hochmuth R.M. Micropipette suction for measuring piconewton forces of adhesion and tether formation from neutrophil membranes. Biophys. J. 1996;71:2892–2901. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z., Anvari B., Brownell W.E. Membrane tether formation from outer hair cells with optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1386–1395. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75493-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leduc C., Campàs O., Prost J. Cooperative extraction of membrane nanotubes by molecular motors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:17096–17101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406598101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fygenson D.K., Marko J.F., Libchaber A. Mechanics of microtubule-based membrane extension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79:4497–4500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waugh R.E., Hochmuth R.M. Mechanical equilibrium of thick, hollow, liquid membrane cylinders. Biophys. J. 1987;52:391–400. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83227-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmandaris V.A., Deserno M. A novel method for measuring the bending rigidity of model lipid membranes by simulating tethers. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:204905. doi: 10.1063/1.2372761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roux A., Cuvelier D., Goud B. Role of curvature and phase transition in lipid sorting and fission of membrane tubules. EMBO J. 2005;24:1537–1545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrich M., Tian A., Baumgart T. Dynamic sorting of lipids and proteins in membrane tubes with a moving phase boundary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7208–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913997107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campelo F., Hernández-Machado A. Model for curvature-driven pearling instability in membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:088101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.088101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue T., Zhang X., Huang F. Molecular modeling of membrane tube pearling and the effect of nanoparticle adsorption. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:10799–10809. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01201a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derényi I., Jülicher F., Prost J. Formation and interaction of membrane tubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers T.R., Huber G., Goldstein R.E. Fluid-membrane tethers: minimal surfaces and elastic boundary layers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2002;65:041901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.041901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koster G., Cacciuto A., Dogterom M. Force barriers for membrane tube formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:068101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.068101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baoukina S., Marrink S.J., Tieleman D.P. Molecular structure of membrane tethers. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1866–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian F., Yue T., Zhang X. Size-dependent formation of membrane nanotubes: continuum modeling and molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:3474–3483. doi: 10.1039/c7cp06212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svitkina T.M., Bulanova E.A., Borisy G.G. Mechanism of filopodia initiation by reorganization of a dendritic network. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:409–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Önfelt B., Nedvetzki S., Davis D.M. Cutting edge: membrane nanotubes connect immune cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:1511–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vignjevic D., Kojima S., Borisy G.G. Role of fascin in filopodial protrusion. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:863–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlsson M., Sott K., Orwar O. Formation of geometrically complex lipid nanotube-vesicle networks of higher-order topologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11573–11578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172183699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuvelier D., Derényi I., Nassoy P. Coalescence of membrane tethers: experiments, theory, and applications. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2714–2726. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurtig J., Gustafsson B., Orwar O. Electrophoretic transport in surfactant nanotube networks wired on microfabricated substrates. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5281–5288. doi: 10.1021/ac060229i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobovkina T., Dommersnes P., Orwar O. Zipper dynamics of surfactant nanotube Y junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:188105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.188105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobovkina T., Dommersnes P.G., Orwar O. Shape optimization in lipid nanotube networks. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter. 2008;26:295–300. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2007-10325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooke I.R., Deserno M. Solvent-free model for self-assembling fluid bilayer membranes: stabilization of the fluid phase based on broad attractive tail potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:224710. doi: 10.1063/1.2135785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noguchi H. Solvent-free coarse-grained lipid model for large-scale simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:055101. doi: 10.1063/1.3541246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnarez C., Uusitalo J.J., Marrink S.J. Dry Martini, a coarse-grained force field for lipid membrane simulations with implicit solvent. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:260–275. doi: 10.1021/ct500477k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong-ekkabut J., Karttunen M. The good, the bad and the user in soft matter simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2529–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. B. J. Chem. Sci. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu W., von dem Bussche A., Gao H. Nanomechanical mechanism for lipid bilayer damage induced by carbon nanotubes confined in intracellular vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12374–12379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605030113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou G., Yi X., Gao H. Packing of flexible nanofibers in vesicles. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2018;19:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi X., Zou G., Gao H. Mechanics of cellular packing of nanorods with finite and non-uniform diameters. Nanoscale. 2018;10:14090–14099. doi: 10.1039/c8nr04110e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiba H., Noguchi H. Estimation of the bending rigidity and spontaneous curvature of fluid membranes in simulations. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2011;84:031926. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.031926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noguchi H. Anisotropic surface tension of buckled fluid membranes. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2011;83:061919. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.061919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu M., Diggins P., IV, Deserno M. Determining the bending modulus of a lipid membrane by simulating buckling. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:214110. doi: 10.1063/1.4808077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diggins P., IV, McDargh Z.A., Deserno M. Curvature softening and negative compressibility of gel-phase lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12752–12755. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipowsky R., Sackmann E. Volume 1. Elsevier; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 1995. Structure and Dynamics of Membranes (Handbook of Biological Physics) pp. 521–602. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shillcock J.C., Lipowsky R. Tension-induced fusion of bilayer membranes and vesicles. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:225–228. doi: 10.1038/nmat1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grafmüller A., Shillcock J., Lipowsky R. Pathway of membrane fusion with two tension-dependent energy barriers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:218101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.218101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grafmüller A., Shillcock J., Lipowsky R. The fusion of membranes and vesicles: pathway and energy barriers from dissipative particle dynamics. Biophys. J. 2009;96:2658–2675. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontes B., Viana N.B., Nussenzveig H.M. Structure and elastic properties of tunneling nanotubes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008;37:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans E., Yeung A. Hidden dynamics in rapid changes of bilayer shape. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1994;73:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilbert E.N., Pollak H.O. Steiner minimal trees. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1968;16:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakagaki T., Kobayashi R., Ueda T. Obtaining multiple separate food sources: behavioural intelligence in the Physarum plasmodium. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004;271:2305–2310. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atilgan E., Wirtz D., Sun S.X. Mechanics and dynamics of actin-driven thin membrane protrusions. Biophys. J. 2006;90:65–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.