Abstract

Although 11C-labelled sulfur-containing amino acids (SAAs) including L-methyl-[11C]methionine and S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine, are attractive tracers for glioma positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, their applications are limited by the short half-life of the radionuclide 11C (t1/2 = 20.4 min). However, development of 18F-labelled SAAs (18F, t1/2 = 109.8 min) without significant structural changes or relying on prosthetic groups remains to be a great challenge due to the absence of adequate space for chemical modification.

Methods: We herein present 18F-trifluoromethylated D- and L-cysteines which were designed by replacing the methyl group with 18F-trifluoromethyl group using a structure-based bioisosterism strategy. These two enantiomers were synthesized stereoselectively from serine-derived cyclic sulfamidates via a nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation reaction followed by a deprotection reaction. Furthermore, we conducted preliminary in vitro and in vivo studies to investigate the feasibility of using 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines as PET tracers for glioma imaging.

Results: The two-step radiosynthesis provided the desired products in excellent enantiopurity (ee > 99%) with 14% ± 3% of radiochemical yield. In vitro cell study demonstrated that both enantiomers were taken up efficiently by C6 tumor cells and were mainly transported by systems L and ASC. Among them, the D-enantiomer exhibited relatively good stability and high tumor-specific accumulation in the animal studies.

Conclusion: Our findings indicate that 18F-trifluoromethylated D-cysteine, a new SAA tracer, may be a potential candidate for glioma imaging. Taken together, our study represents a first step toward developing 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines as structure-mimetic tracers for PET tumor imaging.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation, 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteine, 18F-labelled sulfur-containing amino acid, glioma imaging

Introduction

Amino acids (AAs) enter cells via transport mediated by specific plasmatic membrane proteins 1, 2, also known as AA transporters that are highly up-regulated in various malignant tumors in comparison to normal tissues (e.g., systems L, ASC, and A) 3-9. Targeting the elevated expression of AA transporters is an effective way to design the radiolabelled AAs as tumor-specific imaging tracers. No surprise, positron-labelled AAs have been an important class of radiopharmaceuticals for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of cancer (e.g., prostate, breast, and brain cancer) 10-17.

Initial applications and studies mainly focused on the naturally occurring AAs, because carbon-11 (11C) can be easily incorporated into AAs without any effects on biological properties 18-21. Sulfur-containing AAs (SAAs) play many physiological and metabolic roles in living systems, such as protein synthesis, methylation of DNA, and biosynthesis of glutathione 22. L-methyl-[11C]methionine ([11C]MET, Figure S1A), an essential SAA labelled with 11C, has been extensively used for brain tumor imaging 23-27. Compared with clinically used 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose ([18F]FDG), [11C]MET accumulates preferentially in tumor cells but poorly in normal brain cells, thus providing a higher sensitivity to detect brain tumors 26, 28, 29. However, [11C]MET is taken up not only by tumors but also by other inflammatory lesions, leading to low tumor specificity 30-33; additionally, it is susceptible to in vivo metabolism 34, complicating kinetic analysis. To address these deficiencies, S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine 1L (S-[11C]CH3-L-CYS) and S-[11C]-methyl-D-cysteine 1D (S-[11C]CH3-D-CYS), a pair of 11C-labelled S-methylcysteine enantiomers (Figure 1A and Figure S1B), were successively developed via 11C-isotopic substitution in our previous studies 35-38. Preliminary studies indicated that the tracers were superior to [18F]FDG and [11C]MET in the differentiation of tumor from inflammation 35, 36, 38-40. Nevertheless, the short half-life of 11C (t1/2 = 20.4 min) restricts the widespread application of these tracers, resulting in an urgent demand for 18F-labelled SAA tracers (18F, t1/2 = 109.8 min).

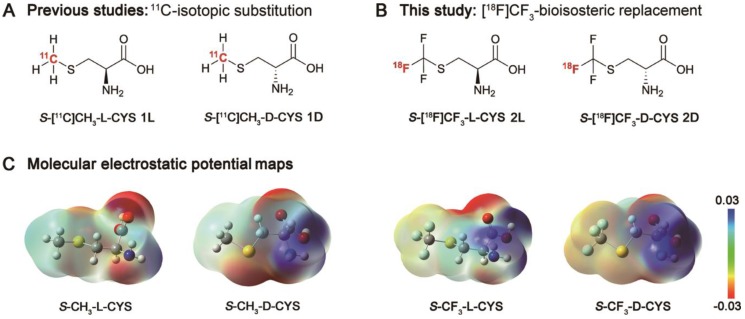

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of S-[11C]CH3-L-CYS 1L and S-[11C]CH3-D-CYS 1D using isotopic substitution of -CH3 with -[11C]CH3 in our previous studies; (B) Chemical structures of S-[18F]CF3-L-CYS 2L and S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS 2D using bioisosteric replacement of -CH3 with -[18F]CF3 in this study; (C) Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps of S-CH3-L-CYS, S-CH3-D-CYS and their mimics were carried out at the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level using the Gaussian® 09W computational package in the water phase (the blue indicates the distribution of positive charge, and the red indicates the distribution of negative charge). As shown, S-CF3-L-CYS and S-CF3-D-CYS are nearly identical in structural arrangement and charge distribution pattern to S-CH3-L-CYS and S-CH3-D-CYS, respectively.

To date, most previous studies on the 18F-labelled SAA tracers (Figure S1B) have concentrated on molecular scaffolds which can be readily radiolabelled by linking with a prosthetic group, such as S-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-homocysteine 41, 42, S-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)-L-homocysteine 43, S-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)-D-homocysteine 43, 44. For the structure-sensitive SAA molecules, however, even minor side-chain alterations caused by the prosthetic groups (S-ethyl and S-propyl) may lead to significant changes in biological properties. More recently, to avoid affecting the biological activity, 18F-B-MET (a methionine boramino acid derivative; Figure S1B) was developed as a potential substitute of [11C]MET by isosteric substitution of carboxylate (-CO2-) group with trifluoroborate (-BF3-) group 45. 18F-B-MET shared the same AA transport systems with [11C]MET owing to the nearly identical charge distribution patterns. But these groups (-BF3- and -CO2-) differ considerably in chemical structure and properties, which may cause potential differences in metabolism of the tracers in vivo. Therefore, despite these undeniable successes, the development of 18F-labelled SAA tracers without significant structural changes or relying on prosthetic groups remains to be a great challenge, highlighting the importance of research on a structure-mimetic tracer.

Trifluoromethyl (-CF3), the smallest symmetrical multi-fluorine group, has captured intense attention in the fields of chemistry and pharmacy, because of its ability to increase chemical and metabolic stability, to improve bioavailability and lipophilicity, and to enhance binding selectivity 46-50. Given these advantages of -CF3 and our interest in 18F-labelled SAA tracers, in this work, we aimed to develop a couple of 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteine enantiomers for PET imaging of glioma. As shown in Figure 1B, S-[18F]CF3-L-CYS 2L and S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS 2D were designed by replacement of methyl (-CH3) group with -[18F]CF3 group according to a structure-based bioisosterism strategy. Encouragingly, this proposal received great support from the calculated molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps of the S-methylcysteines and their mimics (Figure 1C). Herein, we report the synthesis of enantiopure 2L and 2D starting from serine-derived cyclic-sulfamidates via a nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation reaction, and also describe preliminary in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation.

Results and Discussion

Radiochemistry

Although the development of the 18F-trifluoromethylated SAA tracers is conceptually straightforward, it is actually quite challenging due to the difficulty of introducing fluorine-18 into the radiolabelled -SCF3 group. The most efficient synthetic routes toward non-labelled trifluoromethylated SAAs involve direct trifluoromethylation of thiols using electrophilic trifluoromethylating reagents, such as the Togni's 51, 52 and Umemoto's 53 reagents. However, until recently, only one such radiolabelled reagent (18F-Umemoto's reagent) was successfully developed for electrophilic 18F-trifluoromethylation 54. In addition, Liang and Xiao reported a nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation of α-bromo carbonyl compounds and aliphatic halides with difluorocarbene (generated from Ph3P+CF2CO2-; PDFA) in the presence of 18F-fluoride and elemental sulfur (S8) 55, 56. Cahard and Ma recently developed a straightforward method for the synthesis of β- and γ-SCF3 α-AA derivatives through nucleophilic trifluoromethylthiolation of cyclic sulfamidates 57. Moreover, serine-derived cyclic sulfamidates have been widely used as configurationally stable chiral building blocks for the synthesis of enantiopure β-substituted α-AAs 57-59. Inspired by these studies, we envisioned that the 18F-trifluoromethylated SAAs 2L and 2D could be synthesized stereoselectively from serine-derived cyclic sulfamidates via a nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation reaction followed by a deprotection reaction.

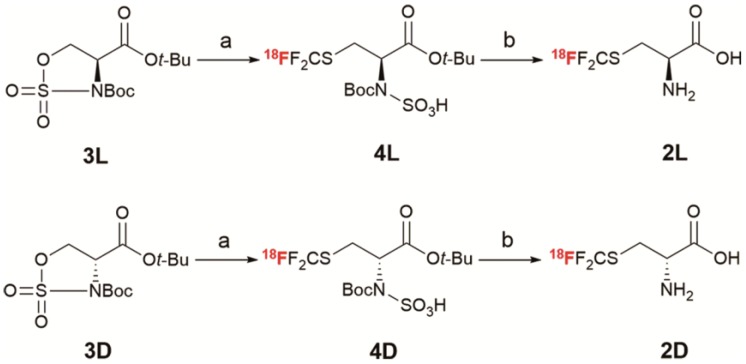

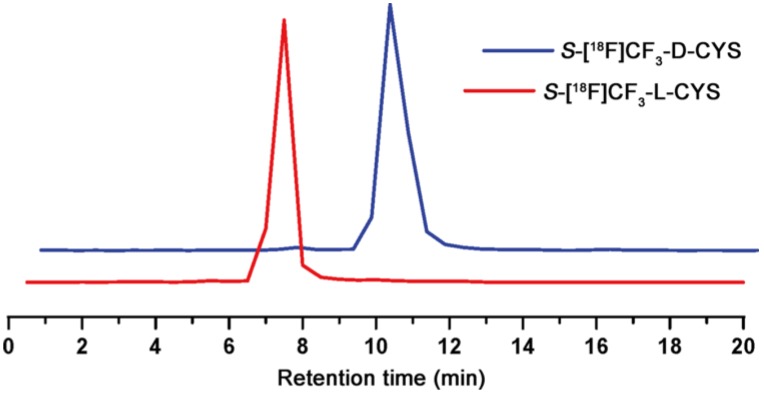

The initial step in our work was to synthesize the cyclic sulfamidates 3L and 3D via a four-step reaction (Scheme S1), according to the reported methods 12, 58, 60-62. With the desired cyclic-sulfamidates in hand, we set out to optimize the reaction conditions (Table S1) and to explore the synthesis of 2L and 2D. As shown in Scheme 1, the 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation of cyclic-sulfamidates 3L and 3D (2 mg, 6 μmol) with PDFA (1.5 mg, 6 μmol) and S8 (3.0 mg, 12 μmol) in the presence of heating-block-dried K2.2.2/K18F was carried out at 70 oC for 5 min to give the radiolabelled intermediates 4L and 4D which were subsequently purified by the C18 cartridge and eluted with ethanol. Then, the solution was evaporated and hydrolyzed in 4N HCl aq. at 90 oC for 10 min 61, 62. Finally, the desired products 2L and 2D were neutralized (pH ≈ 6) and isolated using solid phase extraction to obtain 14% ± 3% RCY (n = 6) in 35 min. The radiochemical purity was higher than 98%, as determined by radio-TLC (Figure S2-3) 63. Similar to a previous report about the synthesis of non-radiolabelled L-trifluoromethylcysteine 64, the harsh hydrolysis conditions failed to lead to a β-elimination side reaction, suggesting a good stability of 2L and 2D in acidic conditions. 2L and 2D had logP values of -2.75 and -2.22, respectively, and were > 95% stable in PBS at 37 oC for up to 2 hours (Figure S5). According to the chiral radio-HPLC analysis, almost no racemization was detected during the synthesis of 2L and 2D (optical purity: ee > 99%; Figure 2 and Figure S4), which forcefully confirmed the feasibility of this nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation protocol (Scheme S2) for synthesizing enantiopure 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 18F-trifluoromethyl cysteine enantiomers 2L and 2D via nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation. Reagents and conditions: a. PDFA, S8, K2.2.2/K18F, CH3CN, 70 oC, 5 min; b. 4N HCl aq., 90 oC, 10 min.

Figure 2.

Chiral radio-HPLC analysis of 2L and 2D (test tube method#).

In vitro cell research

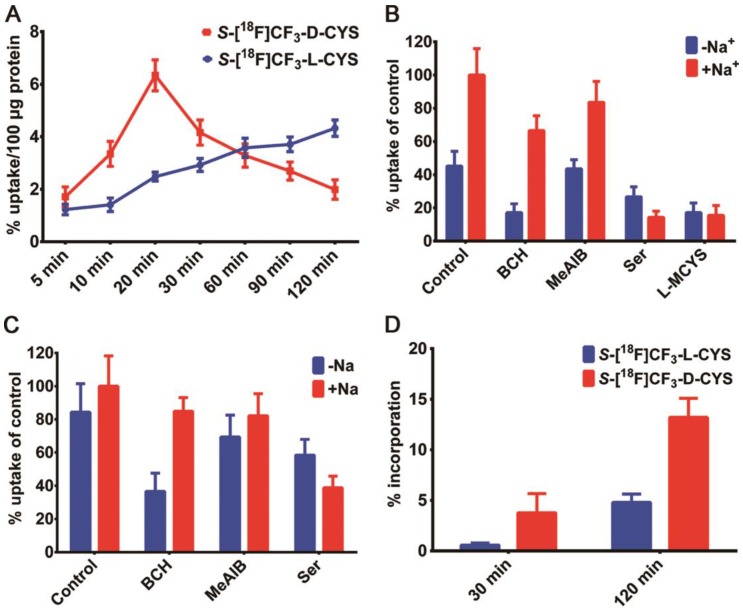

Encouraged by the successful synthesis of 2L and 2D, we conducted in vitro cell uptake study to explore the specificity of each enantiomer. As shown in Figure 3A, the uptake of 2L in C6 cells increased steadily in a time-dependent manner, and the maximal value (4.33% uptake/100 μg protein) appeared at the 120 min. 2D rapidly accumulated in the cells within a short time and reached a maximum of about 6.34% uptake/100 μg protein after incubation for 20 min, but then declined slowly afterward. One possible reason for the above situation was that 2D was being transported into/out of the C6 cells at a higher rate compared with 2L. Thus, the uptake of 2L was higher than that of 2D in C6 cells after approximately 60 min, and the uptake difference was gradually enlarged with the prolonged incubation time. In vitro cell uptake studies indicated that cysteines functionalized with an [18F]CF3 moiety could be taken up efficiently by C6 cells, but there was an obvious distinction between different chiral isomers on the cellular uptake efficiency.

Figure 3.

(A) Time-dependent cell uptake assays with 2L and 2D in C6 cells; (B) Competitive inhibition of C6 cell uptake of S-[18F]CF3-L-CYS 2L after co-incubation with each inhibitor or L-MCYS for 15 min; (C) Competitive inhibition of C6 cell uptake of S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS 2D after co-incubation with each inhibitor for 15 min; (D) The comparison of protein incorporation of 2L and 2D in C6 tumor cell line after incubation for 30 min and 120 min.

Although mammalian cells generally tend to employ L-enantiomer for the biological basic needs, both the enantiomers of AAs can be transported 44. In order to investigate the uptake mechanism of each enantiomer, a competitive inhibition study was performed using C6 glioma cells in the presence of AA transporter inhibitors (Figure 3B-C). After 15 min of incubation in choline chloride solution (-Na+), the cellular uptake of 2L and 2D was obviously decreased by BCH (2-amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid), a classical inhibitor for system L transporters. Additionally, the transportation of 2L and 2D in saline solution (+Na+) was effectively blocked by L-serine (Ser), a non-specific inhibitor for system ASC transporters 36, 65. By contrast, MeAIB (2-aminoisobutyric acid), a system A inhibitor, exerted almost no significant effect on the transportation of 2L and 2D into the cells in either choline chloride or saline solution. Similar to 11C-methyl-cysteines 1L and 1D 35, 36, we found that the cellular uptake of both enantiomers of 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteine in C6 cells mainly relied on the systems L and ASC, however, the system A did not contribute to the radioactive accumulation. Remarkably, the cellular uptake of 2L was significantly suppressed by L-MCYS (S-methyl-L-cysteine) in both choline chloride and saline solution (Figure 3B), strongly suggesting that L-MCYS and its mimic 2L shared the same AA transport systems.

Next, we examined the extent of protein incorporation of each enantiomer in C6 tumor cells, according to the similar reported method 66. After precipitation with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), the protein incorporation of 2L in C6 cells was 0.6% and 4.5% at 30 and 120 min incubation times (Figure 3D), respectively. Thus, there was almost no incorporation of 2L into protein. In comparison, a markedly higher percentage of 2D incorporated into protein, with about 5% and 13% at 30 and 120 min, respectively, implying that there were some interactions between 2D and intracellular macromolecules (perhaps enzymes). Overall, the in vitro cell studies fully demonstrated that cellular uptake of 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines was mainly associated with their AA transport systems across the cell membrane rather than with the protein incorporation.

In vivo biodistribution studies

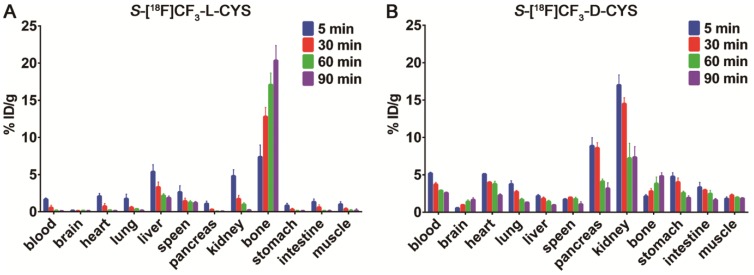

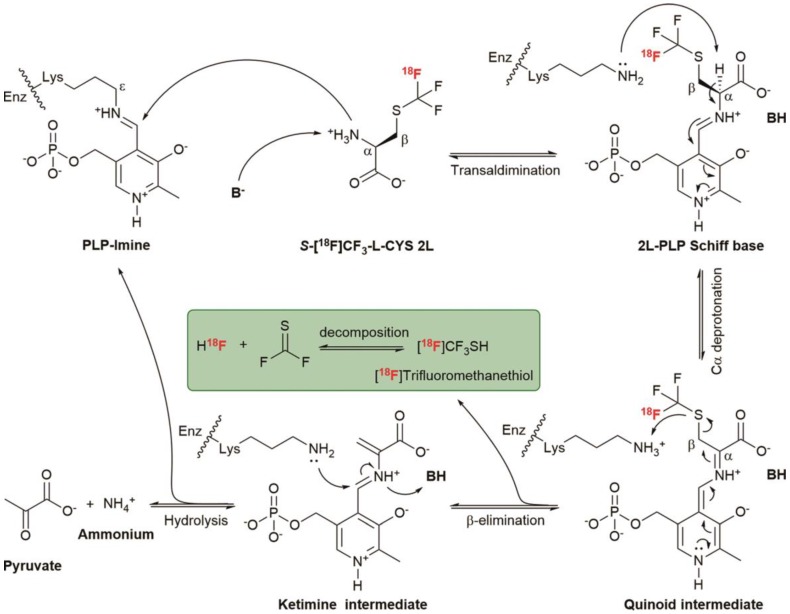

To explore the in vivo biodistribution of each enantiomer, we subsequently performed the studies by dissection on normal Kunming mice (n = 4 per group). Surprisingly, a rapid and progressive accumulation of radioactivity was observed in the bone from 5 to 90 min after injection of 2L (Figure 4A). But for 2D, the bone uptake only slightly increased over time (Figure 4B), suggesting a slow defluorination or a bone marrow uptake. Even though both 2L and 2D were stable in vitro, there was a marked difference in stability between the two enantiomers in vivo. One reasonable explanation is that 2L might serve as a preferential substrate for cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases and underwent an enzyme-catalyzed β-elimination reaction 67, 68. Structurally, 2D is also a cysteine S-conjugate but showed relatively good in vivo stability, presumably because the β-elimination reaction proceeded with high L-stereoselectivity. On the basis of these analyses, a possible mechanism was proposed to explain the surprising in vivo instability of 2L. As illustrated in Scheme 2, the deprotonated base (B-) abstracts a proton from 2L and initiates transaldimination of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP)-imine with the deprotonated α-amino group to form the 2L-PLP Schiff base 69, 70. The Schiff base is then α-deprotonated by the ε-amino group of the lysine residue to give a quinoid intermediate 71, 72. Subsequent elimination of [18F]trifluoromethanethiol ([18F]CF3SH further decomposes to release 18F-fluoride; please see the green box in Scheme 2) from the β-carbon position produces a ketimine intermediate which is finally hydrolyzed to afford PLP-imine, pyruvate and ammonium 69, 73.

Figure 4.

(A) The biodistribution of 2L in normal Kunming mice at 5, 30, 60 and 90 min post-injection; (B) The biodistribution of 2D in normal Kunming mice at 5, 30, 60 and 90 min post-injection.

Scheme 2.

Possible mechanism of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases catalyzed β-elimination of S-[18F]CF3-L-CYS 2L. PLP, the biologically active cofactor, is bound to the enzyme (Enz) at the ε-amino group of the lysine residue.

In addition, biodistribution studies by dissection indicated that 2D was primarily excreted via the kidneys (urinary system) and to a minor extent via the hepatic route. Fast washout of radioactivity from the main tissues and organs (e.g., blood, heart, lung, pancreas, and stomach) was observed during the entire experimental process (Figure 4B), revealing that 2D has advantages of rapid in vivo clearance. Similar to 1L and 1D 35, 36, 39, low accumulation of 2D in the brain was found in the biodistribution data, which could be considered as an advantage or a disadvantage. It was an advantage because the tracer with low brain uptake would contribute to providing a low background activity for PET imaging of brain tumors. On the other hand, it could also be a disadvantage for the tracer, as the uptake in any cranial tumor would be low due to a low availability of the tracer after transport through the blood-brain barrier. Moreover, we also performed a comparison between [18F]FDG and 2D in Kunming mice (n = 4 per group) with turpentine-induced acute inflammation. The preliminary results (data obtained by dissection) showed that 2D had significantly lower inflammation/muscle and inflammation/blood ratios than [18F]FDG at 60 min post-injection (Table S2), which was similar to our previous report on 1D 40.

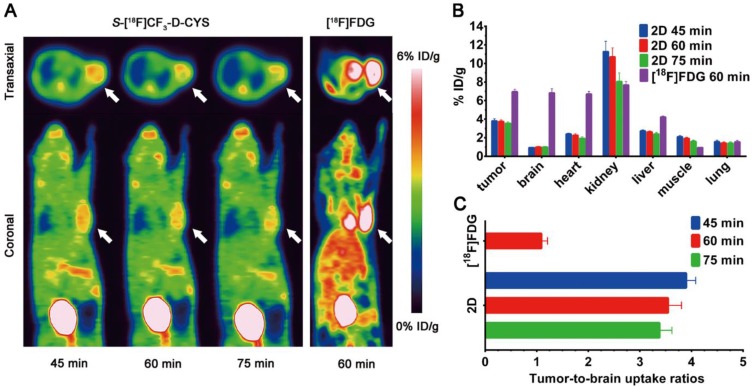

In vivo PET imaging of S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS

The promising results from in vitro cell uptake studies and in vivo biodistribution studies, such as specific tumor-targeting properties and favourable pharmacokinetic characteristics, inspired us to further investigate the feasibility of 2D as an amino acid tracer for glioma PET imaging. As shown in Figure 5A, the D-enantiomer selectively accumulated in C6 tumor tissues to give a good tumor-to-background contrast, which was predominantly cleared by renal excretion with moderate liver accumulation. The average uptake values of 2D in the tumor were 3.81 ± 0.23, 3.74 ± 0.18, 3.56 ± 0.15% ID/g (n = 3) at 45, 60 and 75 min after injection, respectively. Compared with [18F]FDG, 2D exhibited relative less tumor radioactivity accumulation but much lower uptake in most major organs (except of pancreas, kidney and bladder), particularly in normal brain tissue (Figure 5A-B). Hence, the tumor-to-brain uptake ratio of 2D was substantially higher than that of [18F]FDG (Figure 5C). In addition, a slightly high 2D uptake was observed in the muscle tissues, which might restrict the application of the D-enantiomer in regions beyond the brain.

Figure 5.

(A) Static micro-PET images of C6 glioma-bearing mice scanned at 45, 60 and 75 min after injection of S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS 2D and at 60 min after injection of [18F]FDG (the white arrow indicates the tumor); (B) Image-derived biodistribution data of 2D (at 45, 60 and 75 min post-injection) and [18F]FDG (at 60 min post-injection) in most major organs and tumor; (C) Comparison of tumor-to-brain uptake ratios between 2D and [18F]FDG at different time points post-injection.

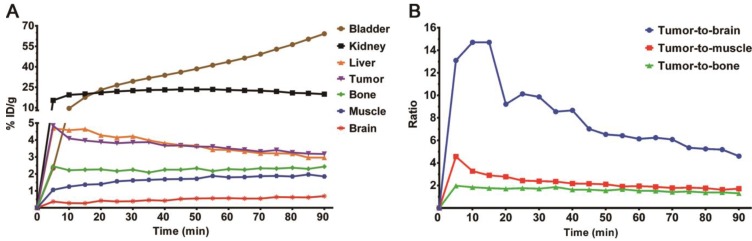

To further determine the distribution patterns of 2D, a 90 min dynamic micro-PET scan was performed in other C6-bearing mice (Figure S6). The time-activity curves were obtained from dynamic images after drawing regions of interest (Figure 6A). Relative uptake ratios of tumor-to-brain, tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-bone at different time points were then calculated and illustrated in Figure 6B. During the first 30 min, 2D reached its maximum uptake value and exhibited a long-term retention in the C6 tumor, then declined slowly. The highest tumor-to-brain uptake ratio of 14.70 was achieved at 15 min after injection of 2D. It was also noteworthy that the bone uptake increased slightly as time went on, which was consistent with the results of the biodistribution studies. Even so, several competing factors should be considered synthetically in the process of defining PET images, such as tumor tissue uptake, in vivo defluorination or bone marrow accumulation, and pharmacokinetic characteristics 74. Additional investigations are warranted in the future to ascertain in vivo metabolic fate of the 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines as well as their stability in vitro in the presence of the cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases. Taken together, these results showed that S-[18F]CF3-D-CYS 2D, an [18F]CF3-functionalized SAA tracer, might be a potential candidate for glioma imaging.

Figure 6.

(A) Time-activity curves of brain, muscle, bone, tumor, liver, kidney and bladder uptake in BALB/c nude mice bearing C6 tumor after injection of 2D; (B) Relative uptake ratios of tumor-to-brain, tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-bone at different time points (0 to 90 min) after injection of 2D.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully designed and synthesized a couple of 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteine enantiomers (2L and 2D) according to a structure-based bioisosterism strategy. In vitro study indicated that cellular uptake of the two enantiomers was primarily associated with AA transport systems L and ASC. Notably, in vivo biodistribution and PET imaging studies demonstrated that 2D was characterized with relatively good stability and high tumor-specific accumulation. Our results suggest that 18F-trifluoromethylated D-cysteine, a new SAA tracer, may be a potential candidate for PET imaging of glioma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to synthesize enantiopure 18F-trifluoromethylated cysteines and to evaluate their feasibility as “structure-mimetic” AA tracers for tumor imaging. Also, a more detailed biological evaluation is underway.

Materials and Methods

Radiochemistry

18F-fluoride was trapped on a QMA light cartridge and subsequently eluted by a H2O/CH3CN (1:9, 1.0 mL) mixed solution of K2CO3 (3 mg) and K2.2.2 (13 mg) into a sealed penicillin bottle (10 mL). The K2.2.2/K18F solution was evaporated at 95 oC for 10 min under a N2 flow and resolubilized in anhydrous CH3CN (1.0 mL). The resulting solution of K2.2.2/K18F in anhydrous CH3CN was entirely transferred into a 10 mL volumetric penicillin bottle (sealed by a rubber cap) containing the cyclic-sulfamidate precursor (3L or 3D; 2 mg, 6 μmol), PDFA (1.5 mg, 6 μmol) and S8 (3.0 mg, 12 μmol). The nucleophilic 18F-trifluoromethylthiolation reaction was carried out at 70 oC for 5 min without electromagnetic stirring. After the reaction completed, the reaction mixture was diluted by 5% AcOH aqueous solution (10 mL) and passed through a C18 plus short cartridge. After washed by sterilized water (10 mL), the 18F-labelled intermediate 4L or 4D was eluted from C18 cartridge by ethanol (1.5 mL) into another sealed penicillin bottle. The solvent was removed by evaporation at 85 oC for 5 min under a N2 flow. 4 N HCl aq. (0.8 mL) was added to the residue and heated for 10 min at 90 °C. Finally, the product (2L or 2D) was purified by passing serially through an AG 11 A8 ion retardation resin column, a Sep-Pak alumina N plus light cartridge, a C18 plus short cartridge, and a sterile Millipore 0.22 μm filter with 0.9% NaCl aq. solution (2 mL) into a final product vial (pH ≈ 6).

A detailed descriptions of all experimental procedures, including organic chemistry synthesis, radiochemistry synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation experiments, can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information, figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 81571704 to G. Tang), the Science and Technology Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nos. 2016B090920087, 2014A020210008 to G. Tang), the Science and Technology Planning Project Foundation of Guangzhou (No. 201604020169 to G. Tang), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 81703343 to G. Yang), a General Financial Grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin-China (No. 16JCQNJC13300 to G. Yang), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities to G. Yang, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (CPSF) (No. 2018M631029 to S. Liu).

Author Contributions

S. Liu designed the study, synthesized the compounds and wrote the original manuscript. S. Liu, H. Ma, Z. Zhang, L. Lin, and G. Yuan conducted the cell and animal experiments. X. Tang, D. Nie, and S. Jiang discussed the results and analysed the data. G. Yang supervised the studies in synthetic chemistry, discussed the results and revised the paper. G. Tang supervised the project, discussed the results, analysed the data and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AAs

Amino acids

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SAAs

Sulfur-containing amino acids

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- [11C]MET

L-methyl-[11C]methionine

- [18F]FDG

2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- S-[11C]CH3-L-CYS

S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine

- S-[11C]CH3-D-CYS

S-[11C]-methyl-D-cysteine

- MEP

Molecular electrostatic potential

- S-CF3-L-CYS

S-trifluoromethyl-L-cysteine

- S-CF3-D-CYS

S-trifluoromethyl-D-cysteine

- -CO2-

Carboxylate group

- -BF3-

Trifluoroborate group

- -CF3

Trifluoromethyl group

- -CH3

Methyl group

- -SCF3

Trifluoromethylthio group

- PDFA

Difluoromethylene phosphobetaine (Ph3P+CF2CO2-)

- S8

Elemental sulfur

- aq.

Aqueous

- RCY

Radiochemical yield

- TLC

Thin-layer chromatography

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- BCH

2-amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid

- Ser

L-serine

- MeAIB

2-aminoisobutyric acid

- L-MCYS

S-methyl-L-cysteine

- TCA

Trichloroacetic acid

- B-

Deprotonated base

- PLP

Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate

- [18F]CF3SH

[18F]Trifluoromethanethiol

- Enz

Enzyme.

References

- 1.Christensen HN. Role of amino acid transport and countertransport in nutrition and metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:43–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fotiadis D, Kanai Y, Palacin M. The SLC3 and SLC7 families of amino acid transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:139–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagida O, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Segawa H, Nii T. et al. Human L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): Characterization of function and expression in tumor cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1514:291–02. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: Partners in crime? Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:254–66. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi K, Ohnishi A, Promsuk J, Shimizu S, Kanai Y, Shiokawa Y. et al. Enhanced tumor growth elicited by L-type amino acid transporter 1 in human malignant glioma cells. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:493–03. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000316018.51292.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganapathy V, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD. Nutrient transporters in cancer: Relevance to Warburg hypothesis and beyond. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu K, Kaira K, Tomizawa Y, Sunaga N, Kawashima O, Oriuchi N. et al. ASC amino-acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) as a novel prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2030–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhutia YD, Babu E, Ramachandran S, Ganapathy V. Amino Acid transporters in cancer and their relevance to "glutamine addiction": Novel targets for the design of a new class of anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1782–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormerais Y, Massard PA, Vucetic M, Giuliano S, Tambutte E, Durivault J. et al. The glutamine transporter ASCT2 (SLC1A5) promotes tumor growth independently of the amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5) J Biol Chem. 2018;293:2877–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laverman P, Boerman OC, Corstens FH, Oyen WJ. Fluorinated amino acids for tumour imaging with positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:681–90. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0716-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mcconathy J, Goodman MM. Non-natural amino acids for tumor imaging using positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography. Cancer Metast Rev. 2008;27:555–73. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McConathy J, Yu WP, Jarkas N, Seo W, Schuster DM, Goodman MM. Radiohalogenated nonnatural amino acids as PET and SPECT tumor imaging agents. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:868–905. doi: 10.1002/med.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong FL, Yang DJ. Amino acid transporter-targeted radiotracers for molecular imaging in oncology. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3271–81. doi: 10.2174/092986712801215946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C, McConathy J. Radiolabeled amino acids for oncologic imaging. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1007–10. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.113100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langen KJ, Watts C. Neuro-oncology: Amino acid PET for brain tumours - ready for the clinic? Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:375–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langen KJ, Galldiks N, Hattingen E, Shah NJ. Advances in neuro-oncology imaging. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:279–89. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun A, Liu X, Tang G. Carbon-11 and fluorine-18 labeled amino acid tracers for positron emission tomography imaging of tumors. Front Chem. 2017;5:124. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1501–16. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott PJ. Methods for the incorporation of carbon-11 to generate radiopharmaceuticals for PET imaging. Angew Chem. 2009;48:6001–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotstein BH, Liang SH, Placzek MS, Hooker JM, Gee AD, Dolle F. et al. 11C=O bonds made easily for positron emission tomography radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:4708–26. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00310a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pekosak A, Filp U, Poot AJ, Windhorst AD. From carbon-11-labeled amino acids to peptides in positron emission tomography: the synthesis and clinical application. Mol Imaging Biol. 2018;20:510–32. doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-1163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. The sulfur-containing amino acids: An overview. J Nutr. 2006;136(Suppl 6):S1636–40. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1636S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herholz K, Hölzer T, Bauer B, Schröder R, Voges J, Ernestus RI. et al. 11C-methionine PET for differential diagnosis of low-grade gliomas. Neurology. 1998;50:1316–22. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung JK, Yu K, Kim S, Yong L, Paek S, Yeo J. et al. Usefulness of 11C-methionine PET in the evaluation of brain lesions that are hypo- or isometabolic on 18F-FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:176–82. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber WA, Wester HJ, Grosu AL, Herz M, Dzewas B, Feldmann HJ. et al. O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine and L-methyl-[11C]methionine uptake in brain tumours: initial results of a comparative study. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:542–9. doi: 10.1007/s002590050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaudemans AW, Enting RH, Heesters MA, Dierckx RA, van Rheenen RW, Walenkamp AM. et al. Value of 11C-methionine PET in imaging brain tumours and metastases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:615–35. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herholz K. Brain Tumors: An update on clinical PET research in gliomas. Semin Nucl Med. 2017;47:5–17. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terakawa Y, Tsuyuguchi N, Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Higashiyama S, Takami T. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 11C-methionine PET for differentiation of recurrent brain tumors from radiation necrosis after radiotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:694–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ullrich RT, Kracht L, Brunn A, Herholz K, Frommolt P, Miletic H. et al. L-methyl-[11C]methionine PET as a diagnostic marker for malignant progression in patients with glioma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1962–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasukawa T, Yoshikawa K, Aoyagi H, Yamamoto N, Tamura K, Suzuki K. et al. Usefulness of PET with 11C-methionine for the detection of hilar and mediastinal lymph node metastasis in lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:283–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubota K. From tumor biology to clinical PET: A review of positron emission tomography (PET) in oncology. An Nucl Med. 2001;15:471–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02988499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki M, Kuwabara Y, Yoshida T, Nakagawa M, Koga H, Hayashi K. et al. Comparison of MET-PET and FDG-PET for differentiation between benign lesions and malignant tumors of the lung. An Nucl Med. 2001;15:425–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02988346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda Y, Oguni H, Saitou Y, Mutoh A, Imai K, Osawa M. et al. Rasmussen syndrome: multifocal spread of inflammation suggested from MRI and PET findings. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1118–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.67602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishiwata K. Metabolic fate of L-methyl-[11C]methionine in human plasma. Eur J Nucl Med. 1989;15:665–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00251681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng HF, Tang XL, Wang HL, Tang GH, Wen FH, Shi XC. et al. S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine: A new amino acid PET tracer for cancer imaging. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:287–93. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang TT, Tang GH, Wang HL, Nie DH, Tang XL, Liang X. et al. Synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation of S-[11C]-methyl-D-cysteine as a new amino acid PET tracer for cancer imaging. Amino Acids. 2015;47:719–27. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1899-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang GH, Tang XL, Deng HF, Wang HL, Wen FH, Yi C. et al. Efficient preparation of [11C]CH3Br for the labeling of [11C]CH3-containing tracers in positron emission tomography clinical practice. Nucl Med Commun. 2011;32:466–74. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283438f9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao BG, Tang CH, Tang GH, Hu KZ, Liang X, Shi XC. et al. Human Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine using whole-body PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:e470–4. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parente A, Waarde AV, Shoji A, Faria DDP, Maas B, Zijlma R. et al. PET imaging with S-[11C]-methyl-L-cysteine and L-methyl-[11C]methionine in rat models of glioma, glioma radiotherapy, and neuroinflammation. Mol Imaging Biol. 2017;20:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11307-017-1137-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang TT, Wang HL, Tang GH, Liang X, Nie DH, Yi C. et al. A comparative uptake study of multiplexed PET tracers in mice with turpentine-induced inflammation. Molecules. 2012;17:13948–59. doi: 10.3390/molecules171213948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang GH, Wang MF, Tang XL, Luo L, Gan MQ. Fully automated synthesis module for preparation of S-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-methionine by direct nucleophilic exchange on a quaternary 4-aminopyridinium resin. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:509–12. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourdier T, Fookes CJR, Pham TQ, Greguric I, Katsifis A. Synthesis and stability of S-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-homocysteine for potential tumour imaging. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 2008;51:369–73. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bourdier T, Shepherd R, Berghofer P, Jackson T, Fookes CJ, Denoyer D. et al. Radiosynthesis and biological evaluation of L- and D-S-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)homocysteine for tumor imaging using positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1860–70. doi: 10.1021/jm101513q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denoyer D, Kirby L, Waldeck K, Roselt P, Neels OC, Bourdier T. et al. Preclinical characterization of 18F-D-FPHCys, a new amino acid-based PET tracer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:703–12. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-2017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang XY, Liu ZB, Zhang HM, Li Z, Munasinghe JP, Niu G. et al. Preclinical evaluation of an 18F-trifluoroborate methionine derivative for glioma imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:585–92. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:320–30. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagmann WK. The many roles for fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4359–69. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meanwell NA. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2529–91. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu LL, Qing FL. Oxidative trifluoromethylation and trifluoromethylthiolation reactions using (trifluoromethyl)trimethylsilane as a nucleophilic CF3 source. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:1513–22. doi: 10.1021/ar4003202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kieltsch I, Eisenberger P, Togni A. Mild electrophilic trifluoromethylation of carbon- and sulfur-centered nucleophiles by a hypervalent iodine(III)-CF3 reagent. Angew Chem. 2007;46:754–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Capone S, Kieltsch I, Flögel O, Lelais G, Togni A, Seebach D. Electrophilic S-trifluoromethylation of cysteine side chains in α- and β-peptides: Isolation of trifluoro-methylated Sandostatin® (octreotide) derivatives. Helv Chim Acta. 2008;91:2035–56. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Umemoto T, Ishihara S. Power-variable electrophilic trifluoromethylating agents. S-, Se-, and Te-(trifluoromethyl)dibenzothio-, -seleno-, and -tellurophenium salt system. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2156–64. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verhoog S, Kee CW, Wang Y, Khotavivattana T, Wilson TC, Kersemans V. et al. 18F-trifluoromethylation of unmodified peptides with 5-18F-(trifluoromethyl)dibenzothiophenium trifluoromethanesulfonate. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:1572–5. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng J, Wang L, Lin JH, Xiao JC, Liang SH. Difluorocarbene-derived trifluoromethylthiolation and [18F]trifluoromethylthiolation of aliphatic electrophiles. Angew Chem. 2015;54:13236–40. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng J, Cheng R, Lin JH, Yu DH, Ma L, Jia L. et al. An unconventional mechanistic insight into SCF3 formation from difluorocarbene: Preparation of 18F-Labeled α-SCF3 carbonyl compounds. Angew Chem. 2017;56:3196–200. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng JL, Chachignon H, Ma JA, Cahard D. Nucleophilic trifluoromethylthiolation of cyclic sulfamidates: Access to chiral β- and γ-SCF3 amines and α-amino esters. Org Lett. 2017;19:1974–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baldwin JE, Spivey AC, Schofield CJ. Cyclic sulphamidates: New synthetic precursors for β-functionalised α-amino acids. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1990;1:881–4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halcomb SBCaRL. Application of serine- and threonine-derived cyclic sulfamidates for the preparation of S-linked glycosyl amino acids in solution- and solid-phase peptide synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2534–43. doi: 10.1021/ja011932l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu WP, McConathy J, Williams L, Camp VM, Malveaux EJ, Zhang ZB. et al. Synthesis, radiolabeling, and biological evaluation of (R)- and (S)-2-amino-3-[18F]fluoro-2-methylpropanoic acid (FAMP) and (R)- and (S)-3-[18F]fluoro-2-methyl-2-N-(methylamino)propanoic acid (NMeFAMP) as potential PET radioligands for imaging brain tumors. J Med Chem. 2010;53:876–86. doi: 10.1021/jm900556s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McConathy J, Martarello L, Malveaux EJ, Camp VM, Simpson NE, Simpson CP. et al. Radiolabeled amino acids for tumor imaging with PET: Radiosynthesis and biological evaluation of 2-amino-3-[18F]fluoro-2-methylpropanoic acid and 3-[18F]fluoro-2-methyl-2-(methylamino)propanoic acid. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2240–9. doi: 10.1021/jm010241x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu WP, Williams L, Camp VM, Olson JJ, Goodman MM. Synthesis and biological evaluation of anti-1-amino-2-[18F]fluoro-cyclobutyl-1-carboxylic acid (anti-2-[18F]FACBC) in rat 9L gliosarcoma. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:2140–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pippin AB, Voll RJ, Li YC, Wu H, Mao H, Goodman MM. Radiochemical synthesis and evaluation of 13N-labeled 5-aminolevulinic acid for PET imaging of gliomas. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017;8:1236–40. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gadais C, Saraiva-Rosa N, Chelain E, Pytkowicz J, Brigaud T. Tailored approaches towards the synthesis of L-S-(trifluoromethyl)cysteine- and L-trifluoromethionine-containing peptides. Eur J Org Chem. 2017;2017:246–51. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu ZH, Zha ZH, Li GX, Lieberman BP, Choi SR, Ploessl K. et al. (2S,4S)-4-(3-[18F]Fluoropropyl)glutamine as a tumor imaging agent. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2014;11:3852–66. doi: 10.1021/mp500236y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urakami T, Sakai K, Asai T, Dai F, Tsukada H, Oku N. Evaluation of O-[18F]fluoromethyl-D-tyrosine as a radiotracer for tumor imaging with positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Bio. 2009;36:295–03. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cooper AJ, Pinto JT. Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases. Amino Acids. 2006;30:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cooper AJ, Krasnikov BF, Pinto JT, Bruschi SA. Measurement of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity. In: Maines MD, Ed. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2010;44:4.36.1–4.36.18. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx0436s44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cooper AJ, Younis IR, Niatsetskaya ZV, Krasnikov BF, Pinto JT, Petros WP. et al. Metabolism of the cysteine S-conjugate of busulfan involves a β-Lyase reaction. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1546–52. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clausen T, Huber R, Messerschmidt A, Pohlenz H-D, Laber B. Slow-binding inhibition of escherichia coli cystathionine β-lyase by L-aminoethoxyvinylglycine: A kinetic and X-ray study. Biochem. 1997;36:12633–43. doi: 10.1021/bi970630m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Metzler CM, Harris AG, Metzler DE. Spectroscopic studies of quinonoid species from pyridoxal 5'-phosphate. Biochem. 1988;27:4923. doi: 10.1021/bi00413a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clausen T, Huber R, Laber B, Pohlenz HD, Messerschmidt A. Crystal structure of the pyridoxal-5'-phosphate dependent cystathionine β-lyase from escherichia coli at 1.83 Å. J Mol Biol. 1996;262:202–24. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cooper AJL, Krasnikov BF, Niatsetskaya ZV, Pinto JT, Callery PS, Villar MT. et al. Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases: Important roles in the metabolism of naturally occurring sulfur and selenium-containing compounds, xenobiotics and anticancer agents. Amino Acids. 2011;41:7–27. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ploessl K, Wang LM, Lieberman BP, Qu WC, Kung HF. Comparative evaluation of 18F-labeled glutamic acid and glutamine as tumor metabolic imaging agents. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1616–24. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.101279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information, figures and tables.