With the widespread emergence of NAI-resistant influenza virus strains, continuous monitoring of mutations that confer antiviral resistance is needed. Laninamivir is the most recently approved NAI in several countries; few data exist related to the in vitro selection of viral mutations conferring resistance to laninamivir. Thus, we screened and identified substitutions conferring resistance to laninamivir by random mutagenesis of the NA gene of the 2009 pandemic influenza [A(H1N1)pdm09] virus strain followed by deep sequencing of the laninamivir-selected variants. We found several novel substitutions in NA (D199E and P458T) in an A(H1N1)pdm09 background which conferred resistance to NAIs and which had an impact on viral fitness. Our study highlights the importance of continued surveillance for potential antiviral-resistant variants and the development of alternative therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: influenza A virus, laninamivir, neuraminidase, pandemic H1N1 virus, resistance, viral fitness

ABSTRACT

Neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (NAIs) are widely used antiviral drugs for the treatment of humans with influenza virus infections. There have been widespread reports of NAI resistance among seasonal A(H1N1) viruses, and most have been identified in oseltamivir-exposed patients or those treated with other NAIs. Thus, monitoring and identifying NA markers conferring resistance to NAIs—particularly newly introduced treatments—are critical to the management of viral infections. Therefore, we screened and identified substitutions conferring resistance to laninamivir by enriching random mutations in the NA gene of the 2009 pandemic influenza [A(H1N1)pdm09] virus followed by deep sequencing of the laninamivir-selected variants. After the generation of single mutants possessing each identified mutation, two A(H1N1)pdm09 recombinants possessing novel NA gene substitutions (i.e., D199E and P458T) were shown to exhibit resistance to more than one NAI. Of note, mutants possessing P458T—which is located outside of the catalytic or framework residue of the NA active site—exhibited highly reduced inhibition by all four approved NAIs. Using MDCK cells, we observed that the in vitro viral replication of the two recombinants was lower than that of the wild type (WT). Additionally, in infected mice, decreased mortality and/or mean lung viral titers were observed in mutants compared with the WT. Reverse mutations to the WT were observed in lung homogenate samples from D199E-infected mice after 3 serial passages. Overall, the novel NA substitutions identified could possibly emerge in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses during laninamivir therapy and the viruses could have altered NAI susceptibility, but the compromised in vitro/in vivo viral fitness may limit viral spreading.

IMPORTANCE With the widespread emergence of NAI-resistant influenza virus strains, continuous monitoring of mutations that confer antiviral resistance is needed. Laninamivir is the most recently approved NAI in several countries; few data exist related to the in vitro selection of viral mutations conferring resistance to laninamivir. Thus, we screened and identified substitutions conferring resistance to laninamivir by random mutagenesis of the NA gene of the 2009 pandemic influenza [A(H1N1)pdm09] virus strain followed by deep sequencing of the laninamivir-selected variants. We found several novel substitutions in NA (D199E and P458T) in an A(H1N1)pdm09 background which conferred resistance to NAIs and which had an impact on viral fitness. Our study highlights the importance of continued surveillance for potential antiviral-resistant variants and the development of alternative therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses remain a global public health concern. The previously circulating oseltamivir-resistant seasonal A(H1N1) viruses, which have caused more than a million deaths worldwide, were replaced in 2010 by the emergence of a novel 2009 pandemic influenza [A(H1N1)pdm09] virus strain, a double-reassortant swine virus first isolated and declared by the WHO to be the cause of a new human pandemic in 2009 (1, 2). Thus, antiviral drugs play a major role in the control of influenza epidemics, providing both chemoprophylactic and therapeutic advantages in times of unexpected pandemics. However, antiviral drug resistance has recently emerged due to the continuous genetic evolution of the influenza viruses, as in the case of most H3N2 viruses after 2005 and all A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, which have been shown to be resistant to adamantanes (M2 blockers, amantadine, and rimantadine) (3). Since all influenza viruses circulating in humans are M2 blocker resistant, only one class of antiviral drugs—the neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (NAIs; e.g., oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir, and, most recently, laninamivir)—are approved and commercially available for the treatment and prevention of influenza virus infections.

Like the hemagglutinin (HA) protein, the neuraminidase (NA) surface antigen of influenza viruses contains a highly conserved catalytic site consisting of 8 functional and 11 framework residues, making it an attractive target for antiviral therapy (4). In the initial phase of viral replication, the HA protein attaches to the sialic acid receptors of host cells, while in the budding phase, the active site of the NA surface antigen cleaves the terminal N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) on the sialic acid moieties, releasing the progeny virions from the host cell, further facilitating viral spread (4). Thus, the structure of NAIs has been designed based on the 2,3-didehydro analog of the N-acetylneuraminic acid (DANA), which mimics the natural substrate of the NA enzyme and competes for binding to the NA active site by possessing a higher binding affinity than Neu5Ac. This structure therefore prevents cleavage of the natural substrate, resulting in failure of the progeny virions to be released from the cell surface and aggregation on the infected cell surface.

However, since the widespread use of oral oseltamivir, oseltamivir-resistant variants have recently emerged and have been reported to involve NA substitutions in A(H1N1) viruses, consisting of H275Y (the N1 numbering is used throughout) (5–7), and in A(H3N2) viruses, consisting of E119V and R293K (8); importantly, these mutants remain susceptible to zanamivir (9). Other substitutions in the NA catalytic sites (e.g., Q136K, D151E/V, D199G, I223R/V/T, S247N, N295S, R368K) identified during surveillance or by reverse genetics (rg) in different influenza virus subtypes conferred reduced susceptibility to several NAIs (e.g., oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir) (9). Laninamivir (commercially available in Japan as Inavir [Daiichi Sankyo]), which is a recent addition to the NAI armamentarium, confers a significant advantage over other NAIs in terms of its (i) activity against oseltamivir-resistant A(H5N1) and A(H1N1) variants (8, 10) and (ii) long-acting effect as postexposure prophylaxis (11). However, various amino acid substitutions within the NA gene found in clinical A(H1N1)pdm09 variants were shown to confer resistance to one or more NAIs, including laninamivir (8, 9, 12). Thus, continuous surveillance is important to increase our understanding of the clinical usefulness of NAIs against emerging cross-resistant influenza virus variants, particularly those with mutations that occur subsequent to treatment with NAIs (13–16), which were reproduced in vitro by successive passages on MDCK cells in the presence of the NAIs (17). This study evaluated the impact of novel substitutions in the NA gene of the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus after passaging with laninamivir pressure on its in vitro and in vivo viral fitness.

RESULTS

Substitutions selected by laninamivir and the susceptibility of the mutants to NAIs.

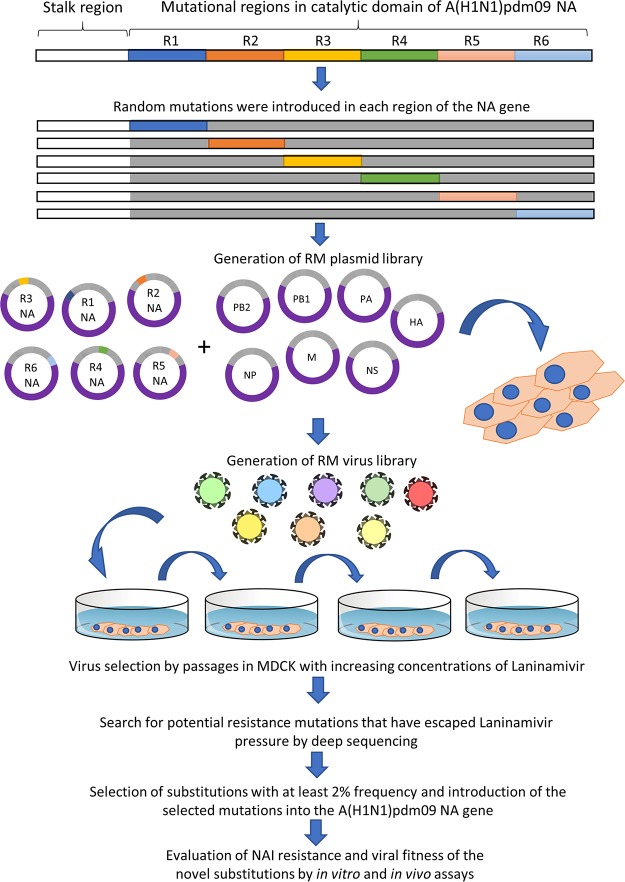

We first introduced random mutations into six individual regions of the NA gene of an A/California/04/2009 [A(H1N1)pdm09] virus to generate random mutant virus libraries. The virus libraries were blind passaged in increasing concentrations of laninamivir in MDCK cells three times, wherein the viruses in the supernatants from the last passage were subjected to deep-sequencing analysis to identify and select mutant viruses that escaped laninamivir pressure and that had potential NAI resistance (Fig. 1). After deep sequencing analysis, we selected mutant viruses that had at least a ≥2% frequency in the viral population for further study, which included testing for susceptibility to NAIs (Table 1). Substitutions in the N1 amino acid residue, which are known to confer resistance to NAIs (e.g., E119D, E119G, Q136K, and R152K), were also identified in this study and escaped the laninamivir selection pressure, with the proportions of the viral populations with these substitutions ranging from 8% to 12% (Table 1). In addition to these known substitutions, we identified by deep sequencing other substitutions in N1 genes at a more than 2% frequency in the viral population (e.g., D199E [7.35%], N200S [18.95%], N248D [17.70%], V264I [17.97%], N270K [17.90%], I321V [18.22%], N369K [18.69%], N386K [17.83%], K432E [17.54%], and P458T [4.08%]). Therefore, as shown in Table 1, wild-type (WT) and mutant viruses possessing these substitutions were generated in the genetic background of an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, using reverse genetics, to verify and further assess the effect of these changes on susceptibility to NAIs (i.e., oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir, and laninamivir).

FIG 1.

Schematic overview of in vitro and in vivo library screening methodology and characterization. A random mutant plasmid library was generated after introducing mutations in the six regions of the catalytic domain of A(H1N1)pdm09 NA. A reverse genetics technique was used to generate the random mutagenesis virus library, followed by passaging in MDCK cells with laninamivir selective pressure three times. The NA genes of the viruses that escaped the laninamivir selective pressure were analyzed by high-throughput sequencing. Selected mutations were introduced into the A(H1N1)pdm09 NA gene individually, and the impact of these substitutions on NAI susceptibility and viral fitness was evaluated.

TABLE 1.

Profiles of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 virus susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitorsf

| Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virusa | Frequencyb (%) | Mean IC50 ± SDc (nM) |

Susceptibility phenotyped (fold changee) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | ZA | PER | LAN | OS | ZA | PER | LAN | ||

| rg-WT | NA | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.001 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | S (1) | S (1) | S (1) | S (1) |

| rg-E119D | 12.76 | 21.47 ± 0.02 | 382.4 ± 29.5 | 24.14 ± 0.16 | 84.43 ± 0.49 | RI (93.3) | HRI (2731.4) | HRI (402.3) | HRI (649.4) |

| rg-E119G | 10.39 | 1.27 ± 0.20 | 40.96 ± 36.14 | 4.73 ± 0.04 | 14.6 ± 0.18 | S (5.5) | HRI (292.5) | RI (78.8) | HRI (112.3) |

| rg-Q136K | 8.88 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 14.72 ± 4.96 | 5.29 ± 0.22 | 5.02 ± 0.19 | S (1.9) | HRI (105.1) | RI (88.1) | RI (38.6) |

| rg-R152K | 10.69 | 9.80 ± 2.29 | 1.67 ± 0.19 | 0.44 ± 0.001 | 2.02 ± 0.24 | RI (42.6) | RI (11.9) | S (7.3) | RI (15.5) |

| rg-D199E | 7.35 | 6.06 ± 0.75 | 1.15 ± 0.38 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | RI (26.3) | S (8.2) | S (3) | S (2.3) |

| rg-N200S | 18.95 | 1.65 ± 1.14 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | S (7.1) | S (1.64) | S (1.3) | S (0.53) |

| rg-N248D | 17.70 | 1.65 ± 1.07 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | S (7.1) | S (0.73) | S (1) | S (0.38) |

| rg-V264I | 17.97 | 1.74 ± 0.98 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | S (7.5) | S (1.5) | S (1.5) | S (0.53) |

| rg-N270K | 17.90 | 1.90 ± 1.03 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | S (8.2) | S (1.2) | S (1.5) | S (1) |

| rg-I321V | 18.22 | 1.56 ± 0.98 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | S (6.7) | S (1.1) | S (1.3) | S (0.53) |

| rg-N369K | 18.69 | 1.52 ± 0.98 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | S (6.6) | S (1.57) | S (1.8) | S (0.84) |

| rg-N386K | 17.83 | 1.48 ± 0.96 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | S (6.4) | S (2) | S (1.8) | S (0.84) |

| rg-K432E | 17.54 | 1.77 ± 0.706 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | S (7.7) | S (2.1) | S (2.3) | S (0.92) |

| rg-P458T | 4.08 | 61.49 ± 4.38 | 113.10 ± 7.10 | 8.88 ± 0.62 | 27.38 ± 4.53 | HRI (280) | HRI (807.8) | HRI (148) | HRI (210.6) |

The amino acid position of the substituted residue in the NA gene sequence is based on the N1 numbering system. The mutant and wild-type viruses were generated using reverse genetics.

Mutation frequency obtained from high-throughput sequencing (Illumina) of the random virus library after the third passage in MDCK cells with laninamivir selective pressure.

Values are means ± standard deviations from two independent experiments.

WHO guidelines were followed when interpreting the phenotype of susceptibility to NAIs: S, susceptible or normal inhibition (<10-fold increase in the IC50 over that for the WT); RI, reduced inhibition (10- to 100-fold increase in the IC50 over that for the WT); HRI, highly reduced inhibition (>100-fold increase in the IC50 over that for the WT).

Ratio relative to the mean IC50 for the WT.

WT, wild type; NA, not applicable; OS, oseltamivir; ZA, zanamivir; PER, peramivir; LAN, laninamivir.

In NAI susceptibility tests, the E119D mutation conferred reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (a 95-fold increase in the 50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]) and highly reduced inhibition by zanamivir, peramivir. and laninamivir (2,660-fold, 460-fold, and 651-fold increases in the IC50s, respectively). The E119G and Q136K mutations conferred mainly reduced to highly reduced inhibition by zanamivir, peramivir, and laninamivir, but the viruses with these mutations remained susceptible to oseltamivir. The R152K mutant remained susceptible to peramivir, but the R152K mutation conferred reduced inhibition by other NAIs. Although viruses with most of the other substitutions (N200S, N248D, V264I, N270K, I321V, N369K, N386K, and K432E) showed normal inhibition by all NAIs, those with the D199E and P458T substitutions—which have not been previously reported—were resistant to more than one of NAIs tested (Table 1). The D199E mutant virus remained susceptible to most of the NAIs, with only reduced inhibition of the virus by oseltamivir being seen. Notably, the novel substitution P458T conferred multidrug resistance to all NAIs, with highly reduced inhibition being seen (Table 1). From these results, further studies focused on the two novel substitutions (i.e., D199E and P458T).

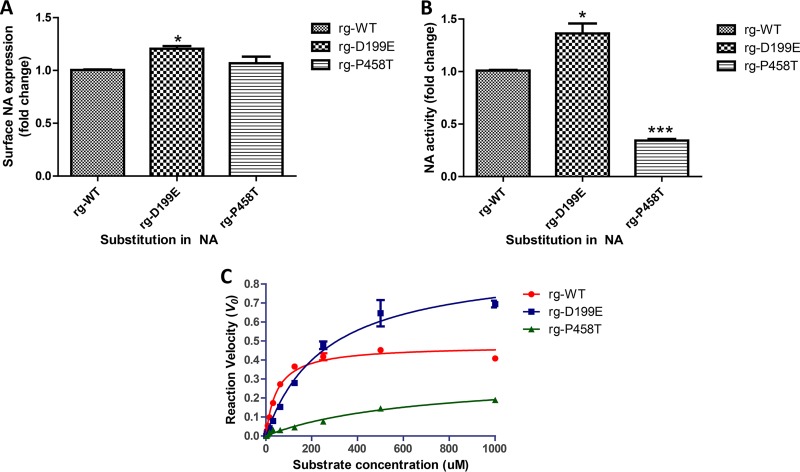

NA protein expression and activity.

MDCK cells were infected with mutant viruses at similar infection doses to assess the impact of the D199E and P458T substitutions on NA protein expression. While the D199E mutation resulted in increased protein expression by 20% compared with that for the WT (P < 0.01), the P458T mutation did not significantly impact NA protein expression (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, NA activity assays revealed that the D199E mutation was associated with increased NA activity (P < 0.02), while the P458T mutation was associated with a significant reduction of NA activity (P < 0.0001) compared with that in the WT (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

NA protein expression and activity and enzyme kinetics of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. (A) The NA protein from recombinant virus-infected MDCK cells was evaluated using Western blot analysis. (B) NA activity was determined using a fluorogenic substrate (MUNANA)-based NA assay. (C) NA enzyme kinetic curves of the three mutant viruses at final MUNANA concentrations ranging from 0 to 1,000 μM. Fluorescence was quantified every 60 s for 60 min at 37°C with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 460 nm, respectively. *, P < 0.05 compared with the value for the WT; ***, P < 0.001 compared with the value for the WT.

NA enzyme kinetics.

Enzyme kinetics were analyzed to evaluate the impact of the NA mutations on neuraminidase activities. The enzyme kinetics of our mutant viruses generated by reverse genetics (rg-mutants) were compared with that of the WT virus generated by reverse genetics (rg-WT virus) (Fig. 2C). The D199E and P458T substitutions were associated with increased values of Km compared with the value for the WT (Km values, 259.45, 645.8 μM, and 49 μM, respectively) (Table 2), which indicated the weak binding of the mutants to the substrate. However, increased enzyme activity was observed in the D199E mutant (Vmax, 0.918 μM/min) and decreased activity was observed in the P458T mutant (Vmax, 0.314 μM/min) compared with that in the WT (Vmax, 0.478 μM/min).

TABLE 2.

Neuraminidase enzymatic properties of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses

| Mutant virus | Mean Kma ± SD (μM) | Mean Vmaxa ± SD (μM/min) | Vmax ratio (% of the value for the WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rg-WT | 49 ± 1.39 (1) | 0.478 ± 0.005 (1) | 100 |

| rg-D199E | 259.45 ± 10.35 (5.3)b | 0.918 ± 0.05 (1.9)c | 192 |

| rg-P458T | 645.8 ± 41.3 (13)b | 0.314 ± 0.16 (0.66)b | 66 |

Parameters indicate mean Km and relative Vmax (NA activity) values from two independent experiments. Values in parentheses are the ratio of the Vmax value of each virus versus the Vmax value of the WT.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

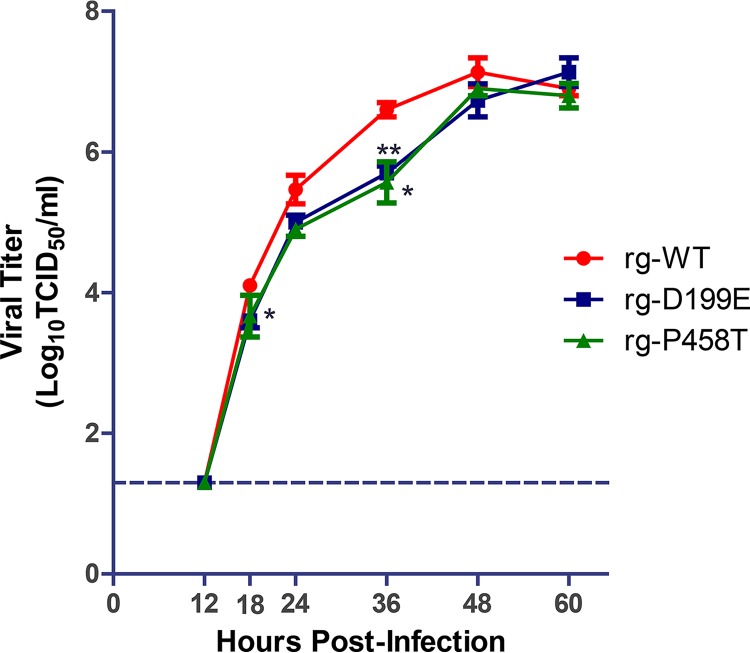

Virus replication kinetics in MDCK cells.

To assess the impact of the single D199E and P458T mutations on viral fitness, the viral replication kinetics of the individual mutants in MDCK cells were characterized. The peak viral titers were obtained at 48 h postinfection (hpi) for all three viruses (Fig. 3). Notably, there was a significant reduction in the viral titers observed at 36 hpi for the D199E and P458T mutants (5.7 and 5.5 log10 50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50]/ml, respectively) compared with the titer for the WT (6.6 log10 TCID50/ml). Although growth was not significantly reduced, there was also a slight delay in the growth of the mutant viruses until 48 hpi, suggesting that these single mutations can alter viral growth and, thus, viral fitness.

FIG 3.

In vitro replication kinetics of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. MDCK cells were infected with mutant viruses at an MOI of 10−4. Cell culture supernatants were harvested at 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h postinfection, and the titers were determined using TCID50 assays in MDCK cells. *, P < 0.05 compared with the value for the WT; **, P < 0,001 compared with the value for the WT.

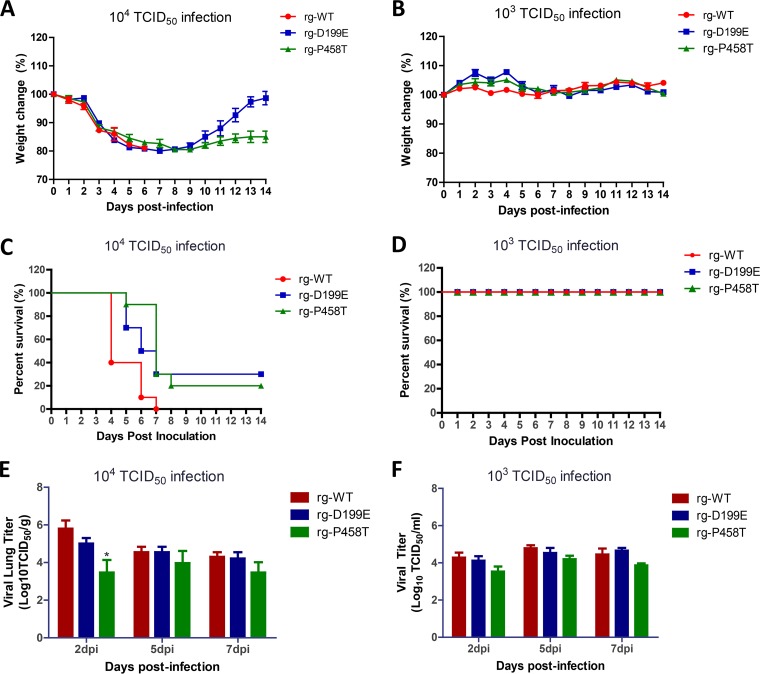

Virus pathogenicity in mice.

To evaluate the impact of the single D199E and P458T substitutions on virus pathogenicity in mice, the lethality and viral replication efficiency of mutant viruses were compared to those of a rg-WT virus using a BALB/c mouse model. As shown in Fig. 4A, while all mice inoculated with 104.0 TCID50 of the WT virus expired within 7 days, those infected with the same amount of single D199E and P458T mutant viruses showed lower mortality rates (70% and 80%, respectively). On the other side, all mice infected with a lower dose of the viruses (103.0 TCID50) showed a 100% survival rate (Fig. 4C) with no significant weight change (Fig. 4B). Viral titers from lungs harvested at 2, 5, and 7 days postinfection (dpi) were higher for the group infected with the WT (5.8, 4.5, and 4.3 log10 TCID50/ml at each dpi, respectively) than for the groups infected with the D199E mutant (5.0, 4.5, and 4.2 log10 TCID50/ml at each dpi, respectively) or the P458T mutant (3.4, 3.9, and 3.4 log10 TCID50/ml at each dpi, respectively) after infection with 104.0 TCID50 (Fig. 4E). Additionally, a significant difference in lung viral titers was observed between mice infected with the rg-P458T and WT viruses at 2 dpi (4.8 and 3.4 log10 TCID50/ml, respectively), clearly indicating that viral growth in the lungs and pathogenicity are quite impaired when the P458T NA substitution is present. Similar observations were seen for mice infected with a lower dose (103.0 TCID50), in which the viral titers from the lungs harvested at 2 and 5 dpi were higher for the group infected with the WT virus than for the groups infected with the mutant viruses and in which mice infected with the P458T virus continued to have the lowest titers among the mice infected with the different viruses (Fig. 4F).

FIG 4.

Pathogenicity of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses in mice. Groups of BALB/c mice (n = 10/group) were infected with 104.0 TCID50 (A, C, and E) and 103.0 TCID50 (B, D, and F) of recombinant and wild-type virus. Mean body weight loss (A and B) and mortality (B and C) were monitored for 14 dpi. (C and D) Lung viral titers were determined at 2, 5, and 7 dpi using TCID50 assays in MDCK cells. *, P < 0.01 compared with the value for the WT.

Genetic stability.

To evaluate genetic stability, single D199E and P458T mutants were passaged in MDCK cells and naive mice, followed by sequencing of supernatants and lung tissue homogenates, respectively, to check for reversion to the WT. After three serial passages in vitro and in vivo, no partial or complete reversion to the WT was observed in the P458T mutant viruses (Table 3). Notably, a partial E199D reversion occurred in 2 out of 3 lung tissue homogenate samples from mice infected with the D199E mutant virus; however, no partial or complete reversions to the WT were observed after three serial passages in MDCK cells (Table 3). These observations could, in part, help explain the low incidence of the D199E substitution in clinical samples.

TABLE 3.

Genetic stability of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in vitro in in vivo after three passages

| Influenza A(H1N1) pdm09 virus | Residue 199a |

Residue 458a |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In vitrob |

In vivoc |

In vitrob |

In vivoc |

|||||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| rg-WT | D | D | D | D | D | D | P | P | P | P | P | P |

| rg-D199E | E | E | E | E/D | E | E/D | P | P | P | P | P | P |

| rg-P458T | D | D | D | D | D | D | T | T | T | T | T | T |

Amino acid residue in N1 numbering. S1, sample 1; S2, sample 2; S3, sample 3.

Passaging of the viruses in MDCK cells in triplicate.

Passaging of the viruses in BALB/c mice in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Most of the recently reported NA substitutions conferring resistance to NAIs are in the active site of the NA enzyme and can be found in either (i) the functional residues (e.g., R118, D151, R152, R224, E276, R292, R371, and Y406), which are associated with alterations of the NA catalytic site, leading to reductions in binding ability, or (ii) the framework residues (e.g., E119, R156, W178, D198, I222, E227, H274, and E425), which are associated with stabilization of the active-site structure (8). Although subtype-specific NA mutations conferring resistance to NAIs and oseltamivir-resistant variants (the H275Y mutation in NA) have been reported previously (6, 18–20), no laninamivir-resistant mutations from clinical samples have been reported (8, 10, 21). However, some viruses, generated by reverse genetics, containing (i) known NA mutations in an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (e.g., E119G, E119V, and Q136K) conferring reduced to highly reduced inhibition by laninamivir (8, 22, 23) and (ii) novel mutations (e.g., I427T [24], I436N [25], and E119D [26]) conferring various degrees of inhibition by NAIs have been described. Nevertheless, the possible emergence of laninamivir resistance should be considered, making the identification of amino acid substitutions conferring resistance to NAIs from in vitro studies valuable in helping elucidate the mechanisms of resistance and predicting clinical cases of resistance to this class of antivirals.

In this study, we generated random mutations in the NA gene of A(H1N1)pdm09 and passaged it in MDCK cells with increasing concentrations of laninamivir. Using this model along with high-throughput sequencing, we identified a number of amino acid substitutions that resulted in escape from laninamivir pressure. Accordingly, some known NA mutations associated with NAI resistance were also identified in this study, namely, E119D, E119G, Q136K, and R152K, and these mutations seemed to retain their properties for conferring NAI resistance even after laninamivir pressure, as described in this study. In previous reports, some of these NAI resistance mutations, particularly R292K in H3N2, were identified in in vitro studies (27). On the other hand, E119D/G has been identified in H3N2, H1N9, H5N1, and influenza B virus variants that were selected through in vitro passages in the presence of zanamivir (8, 10, 28). The naturally occurring Q136K substitution has been associated with resistance to zanamivir in A(H1N1) (29) and A(H3N2) (30) viruses and has also emerged under in vitro zanamivir pressure in A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses (31). Interestingly, H275Y—another important amino acid substitution conferring resistance to certain NAIs in N1 subtype viruses and predominantly found to confer oseltamivir resistance to recently circulating A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses—was not identified in this or related studies after passaging with laninamivir pressure (10). This is likely due to the susceptibility of the oseltamivir-resistant H1N1-H275Y virus to laninamivir, as reported previously (32, 33). Thus, as there were a number of studies evaluating the viral fitness (e.g., drug resistance, enzymatic activity, and viral replication capacity) of mutants with these known substitutions in their respective subtypes, we focused on the two novel substitutions identified during the screening of the escape mutants from laninamivir pressure (i.e., the D199E and P458T NA substitutions). The former is located at the active site of NA, while the latter falls outside of this domain (34).

Amino acid position 199 in the NA gene is of considerable interest because of its previous association with increased resistance to oseltamivir resistance in both seasonal and H5N1 virus strains (35, 36). This position is within the active site of the NA enzyme and, more specifically, serves as a framework residue which, when altered, may compromise active-site stabilization, thus impacting susceptibility to NAIs (8). Interestingly, relatively rare substitutions, such as D199E in previous seasonal H1N1 viruses (36) and D199N in H1N1pdm09 viruses (35, 37), were also detected. An rg-generated A(H1N1)pdm09 virus with D199G was also observed to have resistance to NAIs (23), and the same substitution in an rg-generated A(H5N1) virus and a virus selected under zanamivir pressure also conferred resistance to NAIs (28). Of note, D199N/E were commonly detected substitutions conferring resistance to oseltamivir in influenza type B viruses (9, 13, 14). Apparently, a novel mutation at this position, D199E in NA of A(H1N1)pdm09, was identified in this study after deep sequencing of mutants passaged under laninamivir pressure. Similar to what has been reported with other mutations at this position in other subtypes, changes in susceptibility to NAIs, NA activity, and viral fitness (10, 23, 28) compared to those for the WT were also observed. In this study, the D199E substitution conferred reduced inhibition by oseltamivir; however, susceptibility to other NAIs was maintained. Although this amino acid change results in higher NA activity, kinetics, and expression compared with those for the WT, other fitness parameters seem to be compromised (e.g., replicative capacity, pathogenicity, and genetic stability). The results of the lung viral titration showed titers similar to those of the WT, and further passaging of the D199E mutant virus in mice has shown partial reversion to the WT, suggesting some genetic instability. This instability may help explain the absence of this single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the influenza virus databases (Table 4) and a lack of evidence of circulating human, swine, and avian A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with the D199E substitution. Importantly, there was only one isolate of the H1N1 virus in birds, isolated in 2007, containing the D199E mutation (Table 4); however, no such mutation was detected in swine or humans, which suggests that the fitness of the virus with the amino acid mutation at this position is altered.

TABLE 4.

NA sequence variations of the NAI resistance-associated substitutions identified in human, avian, and swine influenza viruses of N1 subtypes

| Influenza A virus subtype | Amino acid change in NAa | Avian viruses |

Swine viruses |

Human viruses |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism(s) in databaseb (frequency [%]) | No. of sequences | Polymorphism(s) in database (frequency [%]) | No. of sequences | Polymorphism(s) in database (frequency [%]) | No. of sequences | ||

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | D199E | D (100) | 11 | D (100) | 577 | D (99.46), N (0.44), G (0.03), Y (0.03), A (0.003), X (0.04) | 31,188 |

| P458T | P (100) | 11 | P (100) | 577 | P (99.93), S (0.05), A (0.006), X (0.01) | 31,188 | |

| H1N1 | D199E | D (99.8), E (0.1) | 784 | D (99.97), X (0.03) | 3,274 | D (99.89), N (0.04), G (0.04), X (0.02) | 4,606 |

| P458T | P (100) | 784 | P (99.97), S (0.03) | 3,274 | P (100) | 4,606 | |

| H5N1 | D199E | D (99.80), N (0.07), G (0.04), X (0.02) | 4,078 | D (100) | 27 | D (100) | 434 |

| P458T | P (99.80), A (0.7), S (0.04) | 4,078 | P (100) | 27 | P (100) | 434 | |

The amino acid position of the substituted residue in the NA gene sequence is based on the N1 numbering system.

Analysis of data obtained from two influenza databases: the Influenza Research Database and the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data.

Aside from known NAI resistance mutations located in either the catalytic or the framework residues of the NA active site, resistance mutations outside the NA active site—which, although rare, impact susceptibility to some NAIs—have recently been identified [e.g., S467N/G in seasonal H1N1 (38) and H1N1(pdm09) (39) viruses, I427T (24), and I436N (25)]. Interestingly, we identified a novel substitution conferring resistance to multiple NAIs following escape from in vitro laninamivir pressure in A(H1N1)pdm09. The P458T substitution seemingly altered the enzyme’s ability to bind its substrate (as depicted by the enzyme kinetic parameter the Michaelis constant [Km]) compared with that of the WT. However, aside from a decreased affinity of the P458T mutant for its substrate, the P458T mutation also significantly decreased the velocity (Vmax), or NA enzyme activity, compared with that of the WT. This observation may help explain the noted compensatory effect (i.e., decreased viral replication in the lungs compared to that of the WT). It should also be noted that the P458T substitution affected the activity but not the expression of the NA enzyme at the cell surface. Furthermore, our in vivo study showed that the impact of the P458T mutation on viral fitness, which was confirmed in experimentally infected mice, did not cause a higher rate of mortality compared with that caused by the WT. Thus, viral fitness is altered, as shown by reduced NA activity, enzyme kinetics, replication in vitro, and pathogenicity in mice. However, due to some limitations of our study, the precise mechanism behind its multiple-NAI resistance should be verified by a structural crystallography study. Although there is no evidence of naturally circulating influenza virus with the P458T substitution in A(H1N1)pdm09 and H1N1 viruses (Table 4), its escape from in vitro passaging with laninamivir pressure is still unclear, and its potential occurrence cannot be ruled out, based on in vitro and in vivo genetic stability tests, which revealed no reversion after sequential passages in MDCK cells and mice. Additionally, some of the results from this study may also help explain the absence of such mutations in the field, specifically, the significant decrease in NA activity; however, further studies (e.g., transmissibility in animal models) could be beneficial.

Although viruses with other mutations identified in this study (e.g., N200S, N248D, V264I, N270K, I321V, N369K, N386K, and K432E) were sensitive to all NAIs, these substitutions have been previously reported and characterized in other studies. In particular, it has been previously noted that these changes may serve as permissive mutations with potentially synergistic effects in oseltamivir drug resistance by enhancing (i) the expression of NA, (ii) in vitro activity, and (iii) viral fitness (40–42). Specifically, the substitutions N200S, I321V, N369K, N386K, and K432E were previously identified in some oseltamivir-sensitive strains; these substitutions, in conjunction with H275Y or alone, impacted the pattern of binding to and affinity for oseltamivir (41). Relatively slight increases in the level of inhibition (but inhibition that was still normal, based on WHO resistance criteria) by oseltamivir (a 6.0- to 8.0-fold change from that for the WT) were observed in our study of reverse genetics-generated single mutants with these previously reported permissive mutations (Table 1). Thus, further study of these permissive mutations in association with the viral fitness of the resistant variants may also be of interest.

In conclusion, the novel mutations D199E and P458T may confer an oseltamivir-resistant and multidrug-resistant phenotype, respectively, in A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, thus potentially threatening public health. However, the reported results of the altered overall viral fitness of mutants with these mutations may support the absence of these variants in the A(H1N1)pdm09 strains in the SNP analysis of the viruses in influenza virus databases (Table 4). Thus, this study highlights the importance of continuous monitoring for antiviral resistance in both in vitro studies and clinical samples to identify potential markers for multidrug resistance and to develop new antiviral drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and compounds.

MDCK cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM; Corning, Allendale, NJ, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% vitamin, and 1% antibiotics. HEK-293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The NAIs used in this study {i.e., oseltamivir carboxylate [ethyl(3R,4R,5S)-4-acetamido-5-amino-3-(1-ethylpropoxy)-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate], zanamivir (2,4-dideoxy-2,3-didehydro-4-guanidineosialic acid)} were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc. (Toronto, Canada). Peramivir [(1S,2S,3R,4R,1S)-3-(1-acetylamino-2-ethyl) butyl-4(aminoiminomethyl) amino-2-hydroxycyclopentane-1-carboxylic acid] was provided by GreenCross Corp. (South Korea), and laninamivir {5-(acetylamino)-4-[(aminoiminomethyl)amino]-2,6-anhydro-3,4,5-trideoxy-7-O-methyl-d-glycero-d-galacto-non-2-enonic acid} was purchased from BOC Sciences (Shirley, NY, USA). All compounds were dissolved in distilled water and stored in aliquots at −20°C until use.

In vitro identification of laninamivir-selected substitutions and generation of recombinant A(H1N1)pdm09 variants.

Random mutations were introduced within the catalytic domain of the NA plasmid of the A/California/04/2009 (H1N1)pdm09 virus using a GeneMorph II random mutagenesis kit (La Jolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A random mutant plasmid library was generated from six individual regions (size range, 110 to 470 nucleotides) of the NA gene as previously described (43, 44), and 2 random mutant virus libraries were generated using the random mutant plasmid libraries. Briefly, 2 μg of the plasmid harboring NA containing either random mutations or the wild-type sequence and 1 μg of the seven remaining plasmids (harboring PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, M, or NS of the A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 virus) were transfected into an HEK-293T cell–MDCK cell mixture (3:1) in six-well plates using the TransIT-LT1 reagent (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI, USA). The supernatant was replaced with serum-free Opti-MEM medium with antibiotics at 18 h posttransfection, followed by the addition of Opti-MEM medium with tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (1 μg/ml) at 40 h posttransfection. Supernatants were collected at 4 days posttransfection and used to inoculate MDCK cells that had been grown to confluence. After three blind passages of the variant libraries in MDCK cells with increasing concentrations (1 to 5 μM) of laninamivir, the NA gene of the passaged viruses was deep sequenced to identify any substitutions and to select the resistant variants present at a ≥2% frequency in the viral population that had escaped the laninamivir pressure. Substitutions identified within the NA genes were introduced into the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus to generate recombinant viruses using a reverse genetics (rg) technique. The resulting recombinant viruses were subsequently sequenced to confirm that no additional mutations were present.

Measurement of NA protein expressed in virus-infected cells.

NA protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (45), with slight modifications. MDCK cells that had been grown to confluence in 6-well plates were infected with mutant or WT viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. At 18 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed using cell lysis buffer. Following centrifugation of the lysates, SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added and the mixtures were boiled. To ensure that equal amounts of protein were loaded for SDS-PAGE, the abundance of protein in each lysate was quantified using a Bradford assay. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gels) and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The specific NA proteins were identified by Western blot analysis using H1N1 NA rabbit polyclonal (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) antibodies. The target NA protein was detected with horseradish peroxidase (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and quantified using ImageJ software (developed by NIH and the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation, University of Wisconsin).

NA activity assay.

The neuraminidase assay was performed as described by Eichelberger et al. (46) with slight modifications, and NA activity was measured using a fluorescence-based assay leveraging the fluorogenic substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt hydrate (MUNANA) (47, 48). Briefly, MDCK cells that had been grown to confluence in 96-well plates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then infected with 50 μl of virus that had been 2-fold serially diluted to MOIs of 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625, 0.0312, and 0.0156. At 18 h after incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were washed twice with PBS and treated with 75 μl of enzyme buffer and 75 μl of 200 μM MUNANA substrate, and the plate was covered to protect it from light. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, 100 μl of the supernatant was transferred to a black 96-well plate and fluorescence was assessed using a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader with excitation and emission at wavelengths of 360 nm and 460 nm, respectively. The NA activity values obtained from an MOI of 0.5 were normalized by the values from NA protein expression described above.

NA enzyme kinetics assay.

The NA enzymatic properties of the recombinant viruses were determined using a fluorometric assay (48). The recombinant viruses were first standardized based on standard dilution selection as described by Marathe et al. (48), in which the virus dilution for each virus was determined based on the following conditions: (i) the number of relative fluorescence units (RFU) generated was within the range of the plate reader, (ii) the amount of MUNANA substrate converted to product was 10%, and (iii) the signal-to-noise ratio of the number of RFU during the reaction was greater than 10. Briefly, the recombinant viruses were 2-fold serially diluted up to 1:1,024 to identify the virus dilutions that generated a proportional increase in the concentration of 4-methylumbelliferone after incubation with the MUNANA substrate (48). The enzymatic reactions were performed in 96-well flat-bottom black plates, incubated at 37°C, in a total volume of 100 μl (25 μl appropriately diluted virus, 25 μl enzyme buffer, 50 μl MUNANA per well) with different final concentrations of MUNANA ranging from 0 to 1,000 μM. The reaction plates were shaken for 30 s and transferred to a prewarmed Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader. The fluorescence was monitored every 60 s for 60 min at 37°C, using excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 460 nm, respectively. To determine the maximum velocity (Vmax) and the Michaelis constant (Km), enzyme kinetic data were calculated by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression (GraphPad Prism [version 5.0] software).

NAI susceptibility testing.

Drug resistance phenotypes were identified using NA inhibition assays as previously reported (48). Briefly, recombinant viruses were standardized to an NA enzyme activity 10-fold higher than the background and then incubated with 3-fold serial dilutions of oseltamivir carboxylate, zanamivir, peramivir, and laninamivir at 37°C for 30 min. The final concentrations of drugs ranged from 5 × 10−7 μM to 50 μM. The mixtures were further incubated with the fluorogenic substrate MUNANA for another 30 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 150 μl stop solution to halt the reaction. The fluorescence of the resultant 4-methylumbelliferone was measured using a prewarmed Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 460 nm, respectively. The drug concentration that inhibited 50% of the NA enzymatic activity (IC50) was calculated from the dose-response curve using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) software. The susceptibility of the recombinant viruses to NAIs was categorized using the criteria recommended by the WHO Antiviral Working Group and based on the fold change in the IC50 compared with that for the wild-type (WT) NAI-susceptible virus. A mutant showing a <10-fold IC50 increase was considered to be normally inhibited by the NAIs. However, viruses with a 10- to 100-fold IC50 increase were considered to have reduced inhibition by the NAI, while viruses with a >100-fold IC50 increase were considered to have highly reduced inhibition, as previously described (49).

Virus replication kinetics in MDCK cells.

The infectivity of the recombinant stock viruses recovered by rg was determined in MDCK cells by calculating the number of 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) per milliliter. Briefly, MDCK cells prepared in 96-well plates at 24 h prior to infection were infected with 10-fold serially diluted viruses. Cytopathic effects were observed after 60 h, and the supernatants were tested using the hemagglutination assay with 0.5% turkey erythrocytes. To determine the viral replication efficiency in MDCK cells, viruses were inoculated onto confluent MDCK cells that had been seeded onto 6-well plates containing 1 × 106 cells/well at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.0001 and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The supernatants were removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS and overlaid with infection medium containing 1 μg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin. At 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h postinfection (hpi), supernatants were harvested for virus titration. The titers were determined using the TCID50 assay in MDCK cells.

Virus pathogenicity in BALB/c mice.

Groups of 10 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane by use of a gas anesthetic delivery system and then inoculated intranasally with 30 μl of 104.0 TCID50 and 103.0 TCID50 of recombinant or wild-type viruses. The animals were weighed daily and monitored for clinical signs of disease and survival for 14 days after infection. Mice that lost more than 20% of their initial body weight were euthanized. An additional 9 mice per group were inoculated with a dilution of the viruses similar to that described above, and then the lungs were harvested from 3 mice per group at 2, 5, and 7 dpi. The viral titers from the lung tissue samples were determined using the TCID50 assay in MDCK cells.

Assessing the genetic stability of recombinant viruses in vitro and in vivo.

To assess the genetic stability of the conferred mutations in the mutant viruses, all viruses were serially passaged in MDCK cells and mouse lungs. Briefly, confluent MDCK cells in 6-well plates were washed twice with PBS and then inoculated with the mutant viruses at an MOI of 0.001. After adsorption (1 h at 37°C), the infection mixture was replaced with fresh infection medium with TPCK-treated trypsin. At 3 days postinfection, the supernatants were harvested, diluted 10-fold, and used to inoculate newly prepared MDCK cells; this step was repeated for 3 total passages. The genetic stability of the viruses was also evaluated in vivo after three passages in mouse lungs, as follows. First, homogenates of samples of lung tissue collected at 5 dpi from mice subjected to the viral pathogenicity experiment were mixed with 1% antibiotics. Next, the supernatants from the lung tissue homogenates were inoculated intranasally at the maximum virus titer into naive mice for a total of three passages. All virus groups were passaged in triplicate. The NA genes from the serially passaged mutant viruses harvested from MDCK cell supernatant samples and mouse lungs were amplified by reverse transcription-PCR and sequenced to identify any potential reverse mutations.

Ethical statement.

All animal experiments (CBNUA-1133-17-02) and the experimental protocol (16-RDM-028) were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and Institutional Biosafety Committee of Chungbuk National University and conducted in accordance with and adherence to the relevant policies on animal handling mandated in the guidelines for animal use and care of Chungbuk National University, Republic of Korea. Tests with all NAI-resistant viruses were performed in an animal biosafety level 3 facility approved by the South Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (K-CDC).

Statistical analyses.

Data for the NA activity assay and NAI assay and in vitro/in vivo viral titers are expressed as the means for duplicates and triplicates. The NA activity differences, viral titers, and mouse survival and mortality rates were compared between the wild-type and mutant viruses using a t test and were analyzed using the Prism (version 5.0) program (GraphPad Software). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the South Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (no. 2016M3A9B6918676, no. 2018R1A2B2005086, and no. 2018R1A1A3A04077961).

We appreciate the Influenza Research Database and the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data database for sharing the genetic information on the influenza A viruses used in this study.

We declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pada S, Tambyah PA. 2011. Overview/reflections on the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Microbes Infect 13:470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2009. Influenza-like illness in the United States and Mexico. 24 April 2009. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/index.html. Accessed 8 April 2018.

- 3.Bright RA, Medina MJ, Xu X, Perez-Oronoz G, Wallis TR, Davis XM, Povinelli L, Cox NJ, Klimov AI. 2005. Incidence of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause for concern. Lancet 366:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusell R, Gamblin S, Skehel JJ. 2013. Influenza glycoproteins: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase In Webster RG, Monto AS, Braciale TJ, Lamb RA (ed), Textbook of influenza. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang MZ, Tai CY, Mendel DB. 2002. Mechanism by which mutations at his274 alter sensitivity of influenza a virus n1 neuraminidase to oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3809–3816. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3809-3816.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moscona A. 2009. Global transmission of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. N Engl J Med 360:953–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baek YH, Song MS, Lee EY, Kim YI, Kim EH, Park SJ, Park KJ, Kwon HI, Pascua PN, Lim GJ, Kim S, Yoon SW, Kim MH, Webby RJ, Choi YK. 2015. Profiling and characterization of influenza virus N1 strains potentially resistant to multiple neuraminidase inhibitors. J Virol 89:287–299. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02485-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samson M, Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2013. Influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Antiviral Res 98:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen HT, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. 2012. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther 17:159. doi: 10.3851/IMP2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samson M, Abed Y, Desrochers F-M, Hamilton S, Luttick A, Tucker SP, Pryor MJ, Boivin G. 2014. Characterization of drug-resistant influenza A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) variants selected in vitro with laninamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5220–5228. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03313-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashiwagi S, Watanabe A, Ikematsu H, Uemori M, Awamura S. 2016. Long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate as post-exposure prophylaxis for influenza. Clin Infect Dis 63:330–337. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abed Y, Boivin G. 2017. A review of clinical influenza A and B infections with reduced susceptibility to both oseltamivir and zanamivir. Open Forum Infect Dis 4:ofx105. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferraris O, Lina B. 2008. Mutations of neuraminidase implicated in neuraminidase inhibitors resistance. J Clin Virol 41:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ison MG, Gubareva LV, Atmar RL, Treanor J, Hayden FG. 2006. Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. J Infect Dis 193:760–764. doi: 10.1086/500465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, Reisinger KS, Young N, Dutkowski R, Ipe D, Mills RG, Ward P. 2001. Oral oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 20:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Shiraishi K, Kawakami C, Kimura K, Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Kawaoka Y. 2004. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet 364:759–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gubareva LV. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Virus Res 103:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bronson J, Dhar M, Ewing W, Lonberg N. 2011. To market, to market. Annu Rep Med Chem 46:433–502. [Google Scholar]

- 19.James S, Whitley R. 2017. Influenza viruses, p 1465–1471. In Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM (ed), Infectious diseases, 4th ed, vol 2 Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands. doi: 10.1016/C2013-1-00044-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC. 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis—North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 58:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Society for Influenza and other Respiratory Virus Diseases (ISIRV). Clinical overview. https://isirv.org/site/index.php/clinical-overview. Accessed 20 September 2018.

- 22.Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Rhéaume C, Bouhy X, Boivin G. 2013. Evaluation of recombinant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses harboring zanamivir resistance mutations in mice and ferrets. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1784–1789. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02269-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizzorno A, Bouhy X, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2011. Generation and characterization of recombinant pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors. J Infect Dis 203:25–31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu V, Abed Y, Barbeau X, Carbonneau J, Fage C, Lagüe P, Boivin G. 2017. The I427T neuraminidase (NA) substitution, located outside the NA active site of an influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 variant with reduced susceptibility to NA inhibitors, alters NA properties and impairs viral fitness. Antiviral Res 137:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon JJ, Choi WS, Jeong JH, Kim EH, Lee OJ, Yoon SW, Hwang J, Webby RJ, Govorkova EA, Choi YK, Baek YH, Song MS. 2018. An I436N substitution confers resistance of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses to multiple neuraminidase inhibitors without affecting viral fitness. J Gen Virol 99:292–302. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abed Y, Bouhy X, L’Huillier AG, Rhéaume C, Pizzorno A, Retamal M, Fage C, Dubé K, Joly M-H, Beaulieu E, Mallett C, Kaiser L, Boivin G. 2016. The E119D neuraminidase mutation identified in a multidrug-resistant influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 isolate severely alters viral fitness in vitro and in animal models. Antiviral Res 132:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr J, Ives J, Kelly L, Lambkin R, Oxford J, Mendel D, Tai L, Roberts N. 2002. Influenza virus carrying neuraminidase with reduced sensitivity to oseltamivir carboxylate has altered properties in vitro and is compromised for infectivity and replicative ability in vivo. Antiviral Res 54:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurt AC, Holien JK, Barr IG. 2009. In vitro generation of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in A (H5N1) influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00334-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurt AC, Holien JK, Parker M, Kelso A, Barr IG. 2009. Zanamivir-resistant influenza viruses with a novel neuraminidase mutation. J Virol 83:10366–10373. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dapat C, Suzuki Y, Saito R, Kyaw Y, Myint YY, Lin N, Oo HN, Oo KY, Win N, Naito M, Hasegawa G, Dapat IC, Zaraket H, Baranovich T, Nishikawa M, Saito T, Suzuki H. 2010. Rare influenza A (H3N2) variants with reduced sensitivity to antiviral drugs. Emerg Infect Dis 16:493. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaminski MM, Ohnemus A, Staeheli P, Rubbenstroth D. 2013. Pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza A virus carrying a Q136K mutation in the neuraminidase gene is resistant to zanamivir but exhibits reduced fitness in the guinea pig transmission model. J Virol 87:1912–1915. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02507-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamashita M. 2010. Laninamivir and its prodrug, CS-8958: long-acting neuraminidase inhibitors for the treatment of influenza. Antivir Chem Chemother 21:71–84. doi: 10.3851/IMP1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiso M, Shinya K, Shimojima M, Takano R, Takahashi K, Katsura H, Kakugawa S, Le MT, Yamashita M, Furuta Y, Ozawa M, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Characterization of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001079. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colman PM, Varghese JN, Laver WG. 1983. Structure of the catalytic and antigenic sites in influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature 303:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghedin E, Laplante J, DePasse J, Wentworth DE, Santos RP, Lepow ML, Porter J, Stellrecht K, Lin X, Operario D, Griesemer S, Fitch A, Halpin RA, Stockwell TB, Spiro DJ, Holmes EC, St George K. 2011. Deep sequencing reveals mixed infection with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus strains and the emergence of oseltamivir resistance. J Infect Dis 203:168–174. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deyde VM, Sheu TG, Trujillo AA, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten R, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. 2010. Detection of molecular markers of drug resistance in 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses by pyrosequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1102–1110. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01417-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lackenby A, Besselaar TG, Daniels RS, Fry A, Gregory V, Gubareva LV, Huang W, Hurt AC, Leang SK, Lee RTC, Lo J, Lollis L, Maurer-Stroh S, Odagiri T, Pereyaslov D, Takashita E, Wang D, Zhang W, Meijer A. 2018. Global update on the susceptibility of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and status of novel antivirals, 2016-2017. Antiviral Res 157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten RJ, Xu X, Bright RA, Butler EN, Wallis TR, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. 2008. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3284–3292. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00555-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurt AC, Lee RT, Leang SK, Cui L, Deng YM, Phuah SP, Caldwell N, Freeman K, Komadina N, Smith D, Speers D, Kelso A, Lin RT, Maurer-Stroh S, Barr IG. 2011. Increased detection in Australia and Singapore of a novel influenza A(H1N1)2009 variant with reduced oseltamivir and zanamivir sensitivity due to a S247N neuraminidase mutation. Euro Surveill 16(23):pii=19884 10.2807/ese.16.23.19884-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tandel K, Sharma S, Dash PK, Parida M. 2018. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus associated with high case fatality, India 2015. J Med Virol 90:836–843. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu SS, Jiao XY, Wang S, Su WZ, Jiang LZ, Zhang X, Ke CW, Xiong P. 2017. Susceptibility of influenza A(H1N1)/pdm2009, seasonal A(H3N2) and B viruses to oseltamivir in Guangdong, China between 2009 and 2014. Sci Rep 7:8488. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08282-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler J, Hooper KA, Petrie S, Lee R, Maurer-Stroh S, Reh L, Guarnaccia T, Baas C, Xue L, Vitesnik S, Leang SK, McVernon J, Kelso A, Barr IG, McCaw JM, Bloom JD, Hurt AC. 2014. Estimating the fitness advantage conferred by permissive neuraminidase mutations in recent oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004065. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song MS, Marathe BM, Kumar G, Wong SS, Rubrum A, Zanin M, Choi YK, Webster RG, Govorkova EA, Webby RJ. 2015. Unique determinants of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among N3, N7, and N9 avian influenza viruses. J Virol 89:10891–10900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01514-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi WS, Jeong JH, Kwon JJ, Ahn SJ, Lloren KKS, Kwon HI, Chae HB, Hwang J, Kim MH, Kim CJ, Webby RJ, Govorkova EA, Choi YK, Baek YH, Song MS. 2018. Screening for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance markers among avian influenza viruses of the N4, N5, N6, and N8 neuraminidase subtypes. J Virol 92:e01580-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01580-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Catchpole A, Mingay L, Fodor E, Brownlee G. 2003. Alternative base pairs attenuate influenza A virus when introduced into the duplex region of the conserved viral RNA promoter of either the NS or the PA gene. J Gen Virol 84:507–515. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18795-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eichelberger MC, Hassantoufighi A, Wu M, Li M. 2008. Neuraminidase activity provides a practical read-out for a high throughput influenza antiviral screening assay. Virol J 5:109. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potier M, Mameli L, Belisle M, Dallaire L, Melancon S. 1979. Fluorometric assay of neuraminidase with a sodium (4-methylumbelliferyl-α-d-N-acetylneuraminate) substrate. Anal Biochem 94:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marathe BM, Lévêque V, Klumpp K, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2013. Determination of neuraminidase kinetic constants using whole influenza virus preparations and correction for spectroscopic interference by a fluorogenic substrate. PLoS One 8:e71401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization. 2012. Meetings of the WHO Working Group on Surveillance of Influenza Antiviral Susceptibility—Geneva, November 2011 and June 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 87:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]