A minigenome system for HAZV, closely related to CCHFV, was used to study its genome replication. HAZV genome ends, like those of other sNSV, such as peribunyaviruses and arenaviruses, are highly complementary and serve as promoters for genome synthesis. These promoters are composed of two elements: the extreme termini of both 3′ and 5′ strands that are initially bound to separate sites on the polymerase surface in a sequence-specific fashion and the following sequences with the potential to anneal but whose sequence is not important. Nairovirus promoters differ from the other sNSV cited in that they contain a short single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) region between the two elements. The single-stranded nature of this region is an essential element of the promoter, whereas its sequence is unimportant. The sequence of the following complementary region is unexpectedly also important, a possible rare example of sequence-specific dsRNA recognition.

KEYWORDS: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Hazara nairovirus, L protein, RNA synthesis, genomic promoter

ABSTRACT

Hazara nairovirus (HAZV) is a trisegmented RNA virus most closely related to Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) in the order Bunyavirales. The terminal roughly 20 nucleotides (nt) of its genome ends are highly complementary, similar to those of other segmented negative-strand RNA viruses (sNSV), and act as promoters for RNA synthesis. These promoters contain two elements: the extreme termini of both strands (promoter element 1 [PE1]) are conserved and virus specific and are found bound to separate sites on the polymerase surface in crystal structures of promoter-polymerase complexes. The following sequences (PE2) are segment specific, with the potential to form double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), and the latter aspect is also important for promoter activity. Nairovirus genome promoters differ from those of peribunyaviruses and arenaviruses in that they contain a short single-stranded region between the two regions of complementarity. Using a HAZV minigenome system, we found the single-stranded nature of this region, as well as the potential of the following sequence to form dsRNA, is essential for reporter gene expression. Most unexpectedly, the sequence of the PE2 dsRNA appears to be equally important for promoter activity. These differences in sNSV PE2 promoter elements are discussed in light of our current understanding of the initiation of RNA synthesis.

IMPORTANCE A minigenome system for HAZV, closely related to CCHFV, was used to study its genome replication. HAZV genome ends, like those of other sNSV, such as peribunyaviruses and arenaviruses, are highly complementary and serve as promoters for genome synthesis. These promoters are composed of two elements: the extreme termini of both 3′ and 5′ strands that are initially bound to separate sites on the polymerase surface in a sequence-specific fashion and the following sequences with the potential to anneal but whose sequence is not important. Nairovirus promoters differ from the other sNSV cited in that they contain a short single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) region between the two elements. The single-stranded nature of this region is an essential element of the promoter, whereas its sequence is unimportant. The sequence of the following complementary region is unexpectedly also important, a possible rare example of sequence-specific dsRNA recognition.

INTRODUCTION

Hazara nairovirus (HAZV) is a member of the family Nairoviridae in the order Bunyavirales, whose genomes consist of three segments of single-stranded RNA of negative polarity designated S (small; encoding nucleoprotein [N]), M (medium; glycoprotein [Gc and Gn]), and L (large; RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [RdRp]) (1). HAZV was isolated in 1954 from Ixodes ticks collected in Pakistan (2, 3). It is closely related to Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) and shares the same serogroup (4–6). CCHFV is responsible for severe hemorrhagic fever in humans associated with elevated mortality (up to 30%) and is a biosafety level 4 (BSL4) agent. In contrast, HAZV is nonpathogenic to humans and can be handled in a BSL2 laboratory (7–9). HAZV and CCHFV exhibit the same pathology in virus-inoculated immune-deficient animals (8, 9) and share susceptibility to ribavirin (7, 10, 11). The N protein of HAZV structurally resembles that of CCHFV (12), and both proteins interact with heat shock protein 70 family members for efficient viral growth (13). HAZV, then, may be a suitable model to examine the molecular basis of pathogenic-nairovirus replication.

Segmented negative-strand RNA viruses (sNSV) are divided into families with either two (Arenaviridae, e.g., Lassa virus), three (Bunyaviridae, e.g., CCHFV and La Crosse virus [LACV]), or six to eight (Orthomyxoviridae, e.g., influenza virus) genome segments. sNSV genome segments are each packaged with multiple copies of N into separate worm- or rod-like particles (RNPs), on which RNA synthesis occurs via the viral RdRp. All NSV RdRps are structurally similar (14). They contain the canonical RdRp fold with palm, finger, and thumb domains arranged in a right-handed configuration, forming an enclosed cavity within the polymerase core in which RNA synthesis occurs. Four channels communicate between the synthesis chamber and the RdRp surface (15). A unique feature of sNSV is that they form pseudocircular RNPs with both genome ends bound to the polymerase. Furthermore, these ends are highly complementary, so that the antigenome ends can make RdRp interactions similar to those of the genome. The crystal structures of influenza virus and LACV polymerase-promoter complexes show that at least the first 8 nucleotides (nt) of the 5′ and 3′ extremities (within the virus-specific promoter element 1 [PE1]) are bound, not as a panhandle, but as single strands in distinct, positively charged binding sites (16, 17). Remarkably, in neither structure does the 3′ end enter the synthesis chamber in the RdRp core. Instead, they are bound in a sequence-specific manner on the polymerase surface.

The complementarity of bunyavirus genome ends extends beyond the 10 or so nucleotides of PE1. LACV and the prototype Bunyamwera virus (BUNV) (family Peribunyaviridae) genome ends have the potential to form an almost perfect double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) around 20 bp long. This 2nd region of complementarity (PE2) is segment rather than virus specific. For BUNV, the 3′-5′ complementarity within positions 12 to 19 from the ends is also essential for RNA synthesis (18, 19). Moreover, the minimal requirement for BUNV transcription is localized within the terminal 32 nt of the S segment (19). Quasiperfect 19-bp dsRNA genome ends are in fact found in LACV virions and infected cells, but they are now thought to be dead-end replication products that do not participate in viral RNA synthesis, in part because LACV genome ends, as dsRNA, bind very poorly to LACV RdRp (17). However, these dsRNAs may play a role in other aspects of the viral life cycle (20, 21). For influenza A virus, the genome ends bind sequence specifically as single strands to distinct sites on the polymerase but then come together to form a short duplex of about 4 bp (16).

NSV minigenome systems are based on the expression of genome-like reporter RNAs flanked by viral untranslated regions (UTRs), which are encapsidated by N protein and recognized as a template by viral RdRp. These systems can explore specific aspects of the virus life cycle, such as gene expression and genome replication. In this report, we describe a HAZV minigenome system to study the contributions of promoter elements within the genomic ends for nairoviral RNA synthesis.

RESULTS

Analysis of genomic promoter strength in the HAZV minigenome system.

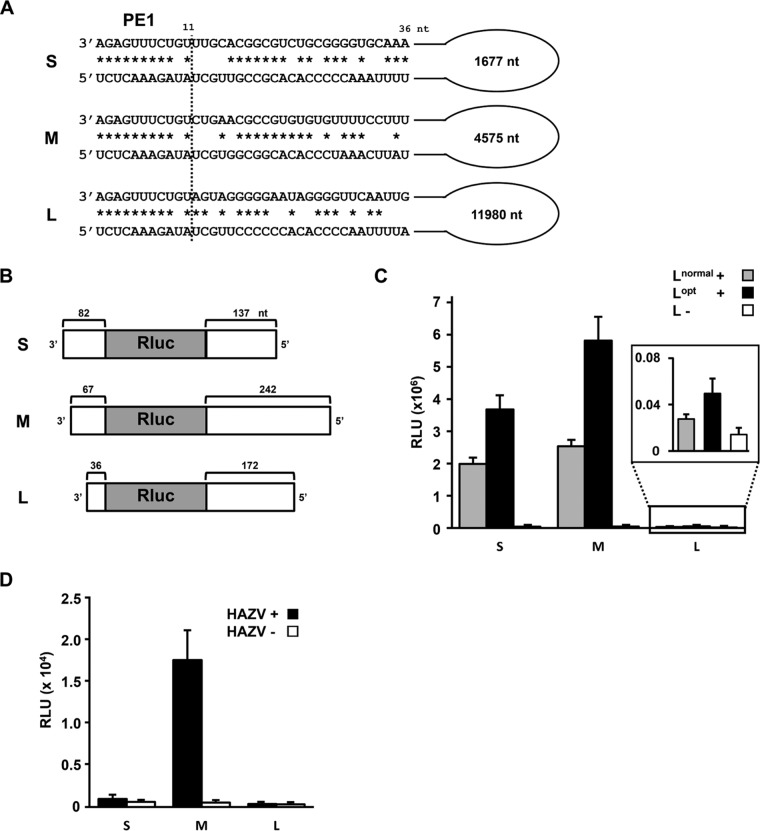

The first 36 nt of the 3′ and 5′ genome ends of the three HAZV segments are shown in Fig. 1A. For all three segments, the first 11 nt are conserved and perfectly complementary, except for a G:U wobble base pair at position 10 of the genome (and an A:C non-base pair in the antigenome). The subsequent sequences are segment specific. We constructed plasmids expressing a HAZV negative-sense minigenome [(−) minigenome] encoding Renilla luciferase (Rluc) flanked by 3′ and 5′ UTRs of their S, M, and L segments under the control of a T7 promoter. The three HAZV minigenomes contained both 3′ and 5′ UTRs of different lengths (Fig. 1B). The plasmids were transfected into BSR T7/5 cells, which constitutively express T7 DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (DdRp) (22), along with pTM1 plasmids expressing the HAZV N and L genes. We additionally prepared pTM1-L, whose codons are optimized for mammalian cell expression (Lopt). The T7-driven HAZV minigenome can be encapsidated by HAZV N, and this RNP can act as a template for HAZV L, resulting in Rluc mRNA transcription. The minigenome is also replicated, generating positive-sense antiminigenomes [(+) antiminigenomes], which further generate (−) minigenomes. As shown in Fig. 1C, Rluc was clearly expressed from the S and M minigenomes using either pTM1-Lnormal or pTM1-Lopt, compared to the L-minus control. Reporter expression driven by Lopt was approximately 2-fold higher than that driven by Lnormal, suggesting that L protein is limiting; Lopt was therefore used for further experiments. The M segment-based minigenome was the most active (Fig. 1C), and similar patterns of Rluc expression were observed when supported by bona fide HAZV infection in place of pTM1 plasmids (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Analysis of promoter strength in the HAZV minigenome system. (A) Schematic of the HAZV S, M, and L genomic promoters. The first 36 nt of both the 3′- and 5′-terminal regions of the HAZV segments are shown. Potential to form Watson-Crick base pairs is indicated by asterisks. The first 11 nt of both the 3′ and 5′ ends are conserved among all segments and are referred to as the virus-specific promoter element (PE1). (B) Schematic of the HAZV S, M, and L minigenomes. The nucleotide lengths of the 3′ and 5′ UTRs flanking the Rluc gene are indicated. (C) HAZV minigenome promoter activities driven by plasmids pTM1-HAZV N and Lnormal or Lopt. No L (L−) served as a negative control. (D) HAZV minigenome promoter activity driven by HAZV infection. The relative light units (RLU) calculated with a luminometer are shown. The data represent means and standard deviations of the results from three separate experiments.

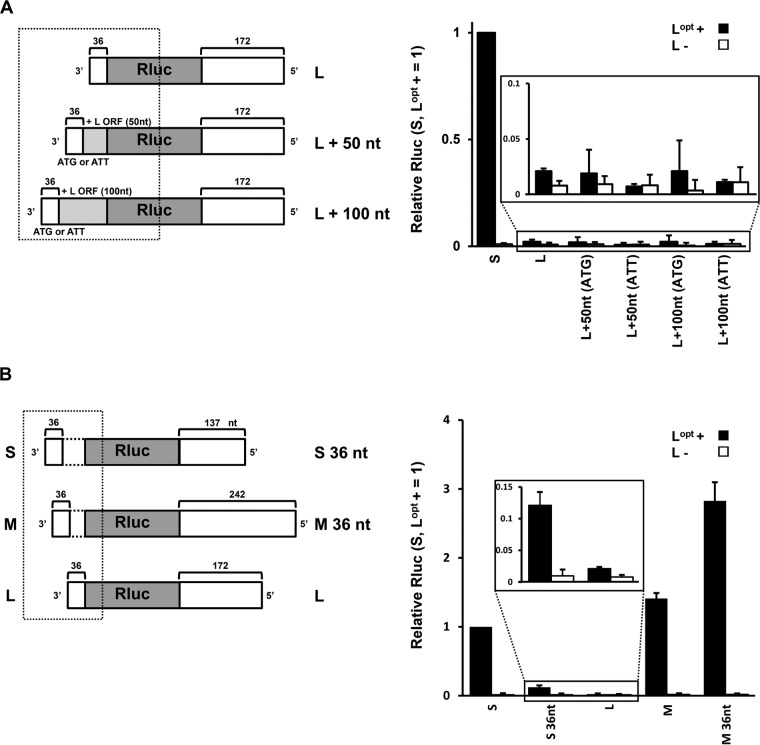

The L segment minigenome, with by far the lowest activity, has a relatively short 3′ UTR, (36 nt) (Fig. 1B). To examine whether the first 36 nt of the HAZV L 3′ UTR is insufficient as a promoter, we prepared L minigenomes whose 3′ nucleotides were extended with the subsequent L open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 2A). To prevent effects due to initiation codons for Rluc translation, mutant (ATG to ATT) minigenomes were also prepared. However, none of these minigenomes showed obvious Rluc expression (Fig. 2A). To further investigate whether the shortness of the 3′ UTR affects HAZV promoter strength, we generated S and M minigenomes whose 3′ UTRs had been reduced to 36 nt and examined them in our minigenome system (Fig. 2B). The S minigenome with a 36-nt-long 3′ UTR (S 36 nt) showed approximately 7-fold lower Rluc expression than the normal S minigenome (Fig. 2B, inset). In contrast, Rluc expression from the M 36-nt minigenome was approximately 2-fold higher than that from the normal M minigenome. Thus, we found no evidence that the shortness of the L segment 3′ UTR is responsible for its low activity. Further, the manner in which the 36 nt of each 3′ UTR affects minigenome expression appears to depend on its coupling with the various 5′ UTRs.

FIG 2.

Analysis of the HAZV 3′ UTR length for Rluc expression. (A) Schematic of the HAZV L minigenomes and relative Rluc activities of the minigenome system. Fifty or 100 nt with or without the initiation codon (ATG or ATT) mutation was added following the L 3′ UTR. (B) Schematic of the HAZV S, M, and L minigenomes and their relative Rluc activities. S 36 nt and M 36 nt are S and M minigenomes whose 3′ UTRs are only 36 nt in length. The Rluc expression from minigenomes was normalized to an internal control, Fluc expression, and relative values are shown (S minigenome with Lopt+ = 1). The data represent means and standard deviations of the results from three separate experiments. The boxed areas in the schematics represent the 3′ regions that were extended or reduced. The scales of the boxed areas in the graphs are expanded in the insets for clarity.

The segment-specific promoter element (PE2).

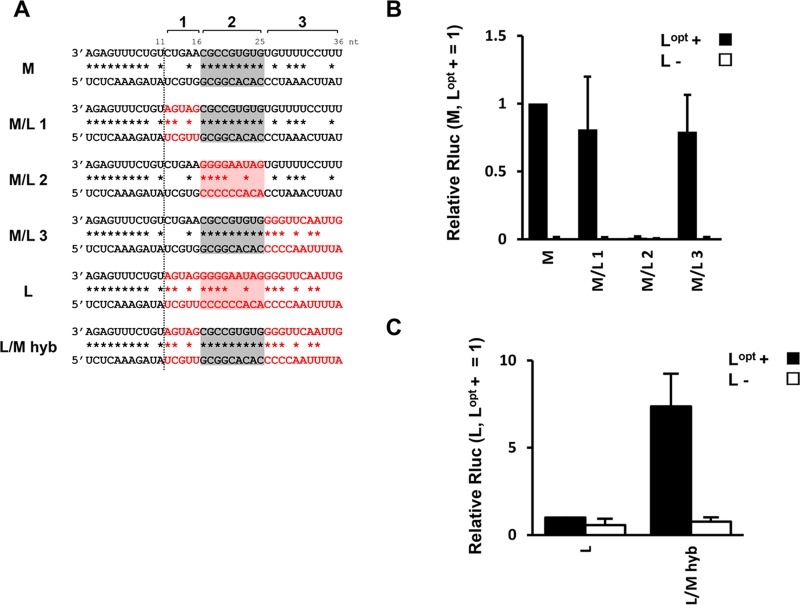

There is a region of noncomplementarity for the S and M segments (positions 12 to 15 or 16 from the genome ends) following PE1, followed again by regions of perfect complementarity (positions 16 to 22 and 17 to 25; 7 and 9 bp in length, respectively) (Fig. 1A). To examine the importance of these sequences following positions 1 to 11, M minigenomes whose sequences between positions 12 and 36 were partially exchanged with those of the L segment were generated (Fig. 3A). Positions 12 to 16, positions 17 to 25, and positions 26 to 36 of M were exchanged to generate M/L 1, M/L 2, and M/L 3, respectively (Fig. 3A). M/L 1 and M/L 3 exhibited Rluc expression levels comparable to those of the M minigenome control. However, that of M/L 2, in which the 9-bp double-stranded region was reduced to the 4 bp of L (positions 17 to 20), was abolished (Fig. 3B). We next generated an L-derived minigenome whose positions 17 to 25 were exchanged with those of the M UTR (L/M hyb) (Fig. 3A). This modification resulted in a 7-fold upregulation of Rluc expression from this L segment-based minigenome (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the dsRNA potential of positions 17 to 25 (which is also elongated to 12 bp in this hybrid construct) is critical for Rluc expression in our minigenome system.

FIG 3.

Importance of a unique promoter structure for HAZV polymerase activity. (A) Schematic of the M/L and L/M chimeric genome promoters. The first 36 nt of both the 3′- and 5′-terminal regions are shown. Sequences following conserved positions 1 to 11 are divided into regions 1 (positions 12 to 16), 2 (positions 17 to 25), and 3 (positions 26 to 36) as shown at the top. Potential to form Watson-Crick base pairs is indicated by asterisks. The gray and light-red shading indicates region 2 of the M and L segments, respectively, and highlights the region's base-pairing possibilities. The red letters indicate positions 12 to 36 of the L segment. (B) Relative Rluc expression from the M/L chimeric minigenomes. The minigenomes used in the experiment were derived from M 36 nt (Fig. 2B). The Rluc expression from minigenomes was normalized to an internal control, Fluc expression, and relative values are shown (M minigenome with Lopt+ = 1). (C) Relative Rluc expression from the L/M chimeric minigenomes. The Rluc expression from minigenomes was normalized to an internal control, Fluc expression, and relative values are shown (L minigenome with Lopt+ = 1). The data represent means and standard deviations of the results from three separate experiments.

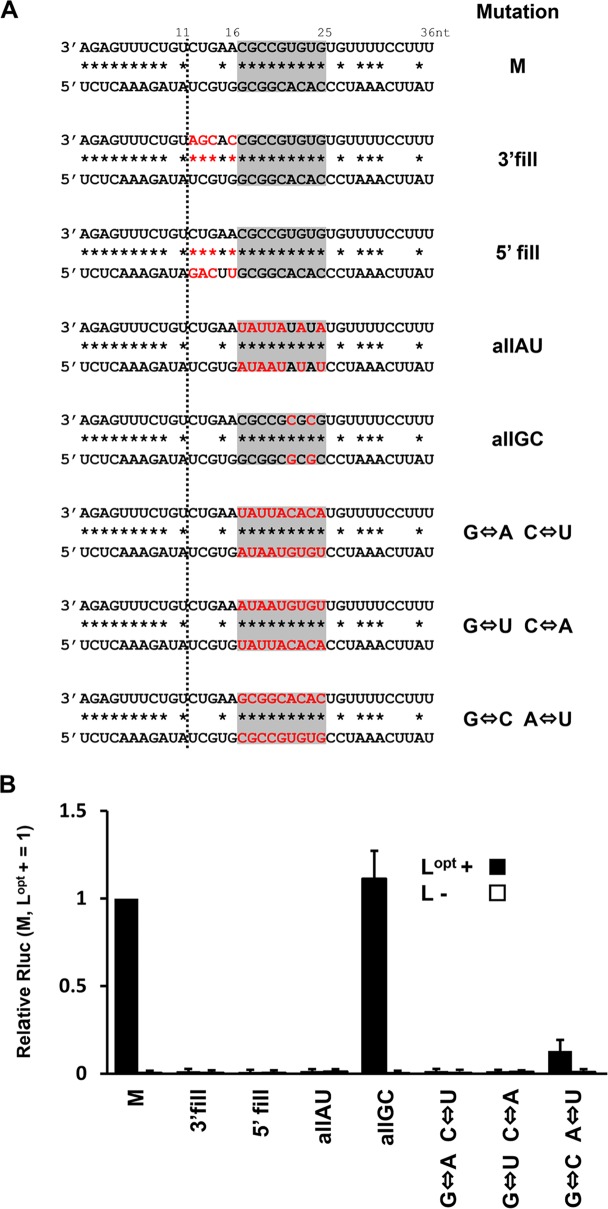

To examine the importance of the mismatch region, positions 12 to 16 of M, M minigenomes were created that filled in the complementarity of the position 12 to 16 gap by modifying either the 3′ or 5′ end so that complementarity extended to position 25 (Fig. 4A, 3′ fill and 5′ fill). In both cases, these minigenomes had lost detectable activity (Fig. 4B). There appears to be no sequence requirement here, only that the region remain unable to form dsRNA. We next examined the importance of the sequence of M positions 17 to 25, which contain 7 G:C and 2 A:U base pairs (positions 22 and 24). Five patterns of nucleotide substitution were performed, all maintaining perfect complementarity: allAU (substitutions, G to A and C to U); allGC (substitutions, A to G and U to C); G↔A C↔U (sequence scramble; substitutions, G to A, A to G, C to U, and U to C); G↔U C↔A (another sequence scramble; substitutions, G to U, U to G, C to A, and A to C); and finally, G↔C A↔U (substitutions, G to C, C to G, A to U, and U to A), which maintained but inverted the 3′ and 5′ sequences. Remarkably, only allGC, in which the two A:U base pairs were replaced by G:C base pairs, showed normal levels of Rluc expression (Fig. 4B). The only other hybrid that showed any activity was G↔C A↔U, in which the same potential dsRNA with 7 G:C and 2 A:U base pairs is present but whose 3′ and 5′ strand sequences are inverted. However, this activity was only ∼10% that of M or allGC. All the other constructs were inactive. Thus, besides the potential of positions 17 to 25 to form dsRNA, the sequence itself also appears to be important.

FIG 4.

Importance of the ssRNA (positions 12 to 16) and dsRNA (positions 17 to 25) regions of the M segment-specific promoter element. (A) Schematic of the mutant M genome promoters. The first 36 nt of both the 3′- and 5′-terminal regions are shown. The gray shading indicates the potential to form Watson-Crick base pairs (asterisks). The sequence changes are indicated by font color and are described in the text. (B) Relative Rluc expression from the mutant minigenomes, all derived from M 36 nt (Fig. 2B). Their Rluc expression levels were normalized to an internal control, Fluc expression, and relative values are shown (M minigenome with Lopt+ = 1). The data represent means and standard deviations of the results from three separate experiments.

Sequence recognition of M position 17 to 25 dsRNA.

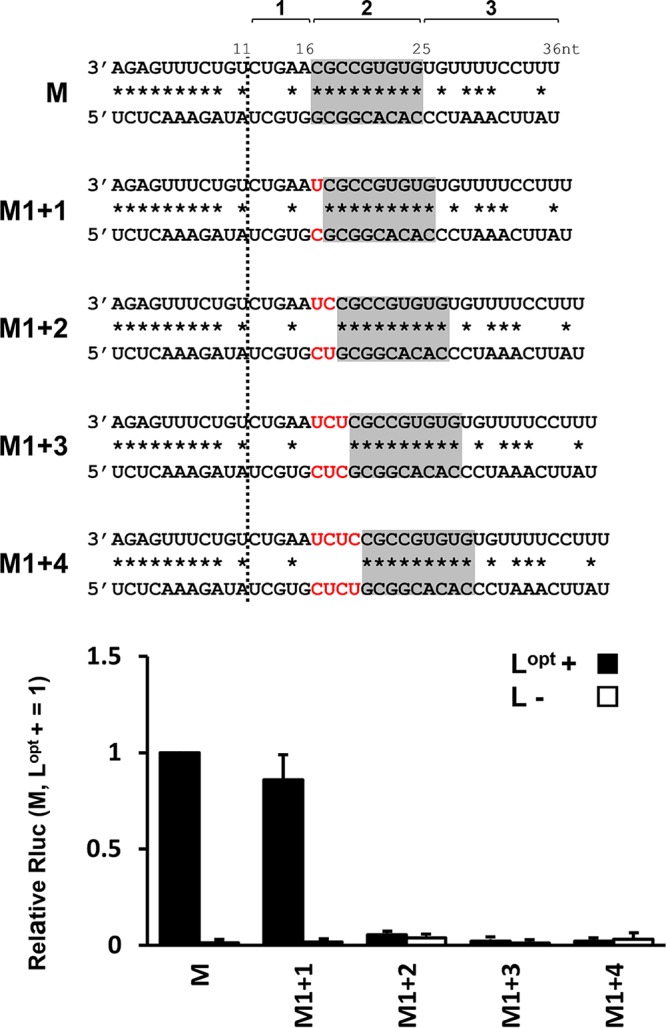

If the sequence of positions 17 to 25 of the M segment-specific promoter element (PE2), as well as its ability to form dsRNA, is important for promoter activity, this dsRNA sequence presumably needs to be recognized by something associated with the RNA synthesis initiation complex. We therefore examined whether the distance between PE1 (positions 1 to 11) and the potential 9-bp dsRNA of PE2 was important for promoter activity. One to four noncomplementary nucleotides were added on each strand after position 16 so that the single-stranded gap was widened and the potential 9-bp PE2 dsRNA was moved progressively downstream of PE1 (Fig. 5). When these constructs were tested, the leeway for the position of this dsRNA was found to be very limited; movement of the 9-bp PE2 dsRNA by one position downstream was well tolerated, whereas further movement resulted in a nearly total loss of activity (Fig. 5). The precise position of the potential 9-bp dsRNA relative to PE1 is thus clearly important for promoter activity.

FIG 5.

Precise position of the dsRNA region of the M segment-specific promoter element. The wild-type M segment promoter is shown at the top. One to four U:C base pairs (M1 + 1 to M1 + 4) (red) were added after position 16, which maintained the single-stranded character of the region and progressively displaced the 9-bp dsRNA (shaded) from the genome ends, as shown. The relative Rluc expression levels are shown in the bar graph below. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

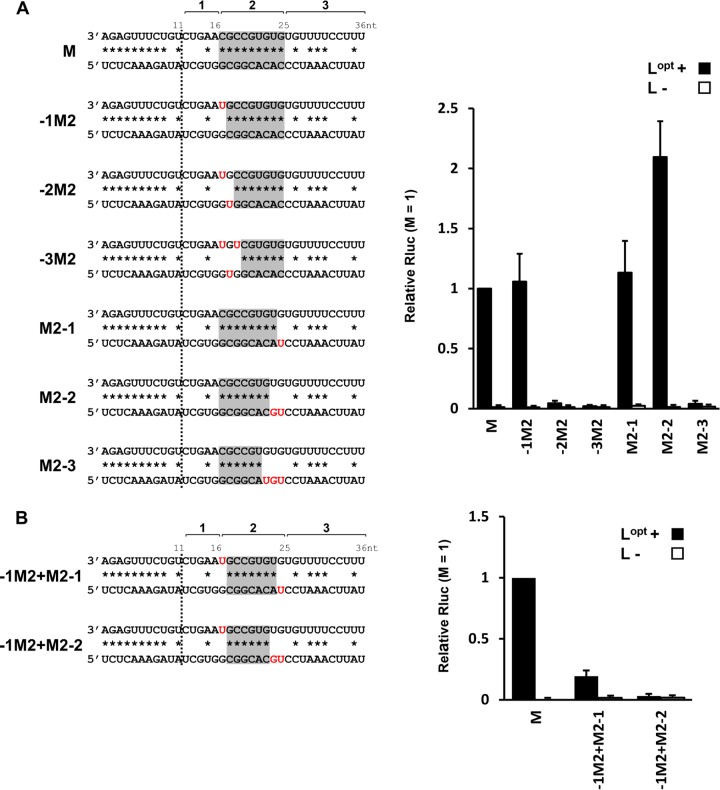

We also examined whether the entire 9-bp dsRNA was required by progressively eliminating complementarity at either end of positions 17 to 25 (Fig. 6A). Elimination of a single base pair at the near end (position 17) was well tolerated, but further elimination at position 18 or at positions 18 and 19 resulted in a nearly total loss of activity (Fig. 6A). Similarly, elimination of either 1 or 2 bp at the far end (positions 25 and 24) was again well tolerated, but elimination of a further base pair (position 23) ablated all activity (Fig. 6A). This suggests that the minimum dsRNA required for activity is 6 bp in length (positions 18 to 23). However, when constructs with losses of complementarity at both ends were examined, those missing complementarity at positions 17 and 25 had nevertheless lost 80% of their activity, and those missing complementarity at position 17 as well as at positions 25 and 24 had virtually no activity (Fig. 6B). One interpretation of these results is that the presumed base-specific interactions of PE2 with the initiation complex include positions 18 to 23 and that the extended complementarity of positions 17 to 25 simply increases the probability that positions 18 to 23 form dsRNA.

FIG 6.

Minimum dsRNA region of the M segment-specific promoter element for promoter activity. (A) The wild-type M segment promoter is shown at the top. The dsRNA character of positions 17 to 25 was progressively shortened from either the PE1-proximal side (−1M2 to −3M2) or the PE1-distal side (M2-1 to M2-3) by converting the G:C base pair to G:U and the A:U base pair to A:C, as shown. (B) Two constructs in which base-pairing possibilities were simultaneously removed from both ends (−1M2+M2-1) and (−1M2+M2-2) were also examined. Their relative Rluc expression levels are shown in the bar graphs on the right. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

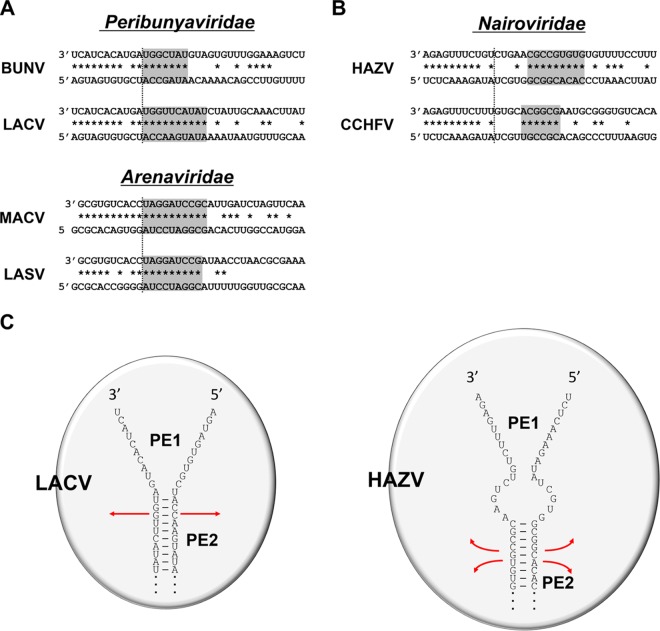

The nucleotide sequences at the ends of sNSV RNA genomes are highly complementary and can often form dsRNA structures (panhandles) ca. 20 bp in length as free RNA. sNSV RNP genome segments are also quasicircular. Their ends are held together both by the binding of the first 8 to 11 nt at each end (the virus-specific promoter elements [PE1]) in a sequence-specific manner to separate sites on the RdRp surface, which prevents their annealing to each other. dsRNA formation due to the extended complementarity of the subsequent sequences (the segment-specific promoter elements [PE2]) may also contribute to this quasicircularity. For peribunyaviruses, like BUNV and LACV, and arenaviruses, like LASV and MACV, these two promoter elements are mostly contained within a single region of nearly perfect end complementarity that extends over approximately the first 20 positions. Only the complementarity of this 2nd element of the above-mentioned sNSV appears to be important for promoting RNA synthesis, independent of their sequences (23).

The need for this 2nd region of complementarity has become more evident with the realization that the initial stage of promoter recognition, i.e., the interaction of RdRp with PE1, is insufficient for promoter activity, as the 3′ end still has to relocate from the L surface to its synthesis chamber for RNA synthesis to begin. Either RdRp must undergo significant conformational changes that allow direct access of the 3′ end to the active site, or the 3′ end must be guided there via the template entry channel. During this 3′ end translocation, the 5′ end of PE1 presumably remains bound to RdRp and tethers the genome template to the initiation complex. dsRNA formation due to the complementarity of PE2 is presumably important for all sNSV, because in its absence, the 3′ end that is no longer bound to the RdRp surface would be free to diffuse away from the vicinity of the polymerase. This tethering of the unbound 3′ end to the initiating RdRp is thus essential for promoter activity, presumably by helping the 3′ end to relocate to the RdRp active site.

Nairovirus promoters appear to differ from those of peribunyaviruses and arenaviruses in two important respects. First, the virus-specific and segment-specific promoter elements are separated by a short region of noncomplementarity, and the inability of this region to form dsRNA appears to be essential for promoter activity. Mutations that made this region of the 3′ strand complementary to that of the 5′ strand, or vice versa, simply ablated all activity (Fig. 4). The single-stranded nature of this region on both 5′ and 3′ strands would allow relatively free movement of the segment-specific dsRNA relative to RdRp-bound PE1 (positions 1 to 11). In the absence of this single-stranded region, the segment-specific dsRNA would be part of a larger duplex, which could form immediately after the base-specific interactions of PE1 with RdRp and restrict its freedom of movement across the RdRp surface (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Cartoon of LACV and HAZV promoter interactions with RdRp. (A and B) Schematic of the genomic promoters of M segments of representative peribunyaviruses and arenaviruses (A) compared to those of nairoviruses (B). The first 36 nt of the 3′- and 5′-terminal regions are shown. Potential to form Watson-Crick base pairs is indicated by the asterisks. The gray shading indicates potential dsRNA formation of the segment-specific promoter element PE2. (C) LACV and HAZV RdRps are depicted as circles; that of HAZV (3,923 amino acids [aa]) is significantly larger than that of LACV (2,263 aa). For topological reference, the path that the LACV ssRNA genome is proposed to follow through the RdRp would accommodate approximately 25 nt (17). The viral genome ends are shown as splayed straight lines, starting with positions 1 to 11 at the top, to indicate their binding to separate sites on RdRp, and as close parallel lines at the bottom to indicate their presence as dsRNA. In both cases, this dsRNA would tether the 3′ positions 1 to 11 to RdRp when it is no longer bound to its surface binding site. A major difference between these sNSV is that whereas the LACV subsequent sequences are fully complementary and could form a single dsRNA stack with limited mobility relative to the RdRp surface (straight red lines), those of HAZV have short ssRNA regions (positions 12 to 16, indicated by dotted lines) preceding the dsRNA (positions 17 to 25). This single-stranded region would allow maximum mobility of positions 17 to 25 dsRNA relative to the RdRp surface (curved red lines), allowing positions 17 to 25 to sample a larger area of the surface to find its proposed sequence-specific dsRNA-binding site.

The second difference is that, whereas only the complementarity of segment-specific PE2 is important for peribunyavirus and arenavirus promoters, the sequence of HAZV M PE2 dsRNA also appears to be important for reporter gene expression. Permutation of the G:C-rich M position 17 to 25 sequence (Fig. 4) showed that few changes were tolerated; only allGC, where the two A:U base pairs at positions 22 and 24 were changed to G:C, had maintained activity. Replacing the 7 G:C base pairs with A:U, which diminishes the thermal stability of the dsRNA, led to the loss of all activity, suggesting that the propensity to form a more stable dsRNA is needed for promoter activity. However, the ability to form a more stable dsRNA alone cannot be the only determinant of promoter activity, as G↔C A↔U, which contains the same number and kind of base pairs as M and whose melting temperature (Tm) would be very similar to that of M, had still lost 90% of its activity.

We assume that recognition of a specific promoter sequence, whether ssRNA of PE1 or dsRNA of PE2, can only be carried out by interacting with protein. Although the sequence-specific recognition of dsRNA is relatively rare compared to that of dsDNA, there is now one clear example of the former, RNase Mini-III from Bacillus subtilis, which carries out sequence-dependent cleavage of long dsRNA (24). Applying Occam’s razor, this possible PE2-protein interaction could be due to a 3rd RNA-binding site on RdRp, as there is no viral protein other than N known to be associated with the RNA synthesis initiation complex. This 3rd interaction could place the PE2 dsRNA at a precise site on the RdRp surface, presumably one that is particularly efficient in helping translocate the PE1 3′ end so that RNA synthesis can initiate. The requirement for an ssRNA gap that uncouples the two complementary regions of the promoter and increases the mobility of position 17 to 25 dsRNA relative to the RdRp surface, is consistent with the need for a specific dsRNA-binding site. The sequences of the various segment-specific PE2s are not conserved, nor are their potentials to form dsRNA, and these differences presumably affect their relative promoter strengths. The efficiency with which 3′ end transfer takes place would of course be a central element of segment promoter strength.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

SW13 cells and BSR T7/5 cells, which constitutively express T7 DdRp (22), were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The HAZV stock (strain JC280; GenBank accession no. [S, M, and L, respectively] M86624.1, DQ813514.1, and DQ076419.1) was prepared using SW13 cells as described previously (8).

Plasmid construction.

To obtain cDNA for the HAZV genome, total RNA from HAZV-infected SW13 cells was isolated by using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out using the SuperScript first-strand cDNA synthesis system (Invitrogen) with random-hexamer primers. To construct HAZV N and L expression plasmids (pTM1-N and pTM1-Lnormal), N and L ORFs were amplified and cloned into the pTM1 vector, which contains a T7 promoter and an encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site. The HAZV minigenomes, designed as schematically outlined in Fig. 1B, were constructed by modifying a human parainfluenza virus type 2 Rluc-expressing minigenome (25, 26). The 3′ and 5′ UTRs of HAZV S, M, and L genomes were cloned and combined with Rluc. All the minigenomes were expressed as the negative-sense RNA under the control of a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. All the modified minigenomes were constructed by using standard PCR mutagenesis. The cDNA for the codon-optimized HAZV L ORF was synthesized (GeneArt, Ratisbonne, Germany) and cloned into the pTM1 vector (pTM1 HAZV Lopt). The firefly luciferase (Fluc) gene was cloned into the pTM1 vector as described previously (25). The nucleotide sequences of all the plasmids were confirmed by a DNA-sequencing method. Primer information used for plasmid construction is available in the supplemental material.

HAZV minigenome assay.

One hundred thousand BSR T7/5 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate. Plasmids (HAZV minigenome, 0.5 μg; pTM1-N, 0.4 μg; and pTM1-L or empty vector, 0.2 μg) and pTM1-Fluc (0.1 μg) were transfected using XtremeGene HP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). At 48 h posttransfection, the Rluc and Fluc activities were measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the results obtained for Rluc were normalized by the expression levels of Fluc.

HAZV minigenome expression driven by HAZV infection.

One hundred thousand BSR T7/5 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate. Plasmids (HAZV minigenome, 0.5 μg) were transfected with XtremeGene HP. At 24 h posttransfection, the culture medium was removed and the cells were infected with HAZV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 1 h. After washing out the inoculum, the cells were cultured in DMEM without FCS for 48 h. The Rluc activity was measured with a Renilla luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Accession number(s).

The codon-optimized HAZV L sequence is available in GenBank under accession number LC420025.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roger Hewson (Public Health England) and Jiro Yasuda (Nagasaki University) for providing HAZV and SW13 cells.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (16K19143) and the Takeda Science Foundation.

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02118-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elliott RM, Schmaljohn C. 2013. Bunyaviridae, p 1244–1282. In Knipe DM, Howley PM. Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begum F, Wisseman CL, Traub R. 1970. Tick-borne viruses of west Pakistan. I. Isolation and general characteristics. Am J Epidemiol 92:180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darwish MA, Imam IZE, Omar FM, Hoogstraal H. 1978. Results of a preliminary seroepidemiological survey for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in Egypt. Acta Virol 22:77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop DH, Calisher CH, Casals J, Chumakov MP, Gaidamovich SY, Hannoun C, Lvov DK, Marshall ID, Oker-Blom N, Pettersson RF, Porterfield JS, Russell PK, Shope RE, Westaway EG. 1980. Bunyaviridae. Intervirology 14:125–143. doi: 10.1159/000149174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foulke R, Rosato R, French G. 1981. Structural polypeptides of Hazara virus. J Gen Virol 53:169–172. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-53-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casals J, Tignor GH. 1974. Neutralization and hemagglutination-inhibition tests with Crimean hemorrhagic fever-Congo virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 145:960–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flusin O, Vigne S, Peyrefitte CN, Bouloy M, Crance J-M, Iseni F. 2011. Inhibition of Hazara nairovirus replication by small interfering RNAs and their combination with ribavirin. Virol J 8:249. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto Y, Ohta K, Nishio M. 2018. Lethal infection of embryonated chicken eggs by Hazara virus, a model for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Arch Virol 163:219–222. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowall SD, Findlay-Wilson S, Rayner E, Pearson G, Pickersgill J, Rule A, Merredew N, Smith H, Chamberlain J, Hewson R. 2012. Hazara virus infection is lethal for adult type I interferon receptor-knockout mice and may act as a surrogate for infection with the human-pathogenic Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J Gen Virol 93:560–564. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.038455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts DM, Ussery MA, Nash D, Peters CJ. 1989. Inhibition of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever viral infectivity yields in vitro by ribavirin. Am J Trop Med Hyg 41:581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mardani M, Jahromi MK, Naieni KH, Zeinali M. 2003. The efficacy of oral ribavirin in the treatment of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Iran. Clin Infect Dis 36:1613–1618. doi: 10.1086/375058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surtees R, Ariza A, Punch EK, Trinh CH, Dowall SD, Hewson R, Hiscox JA, Barr JN, Edwards TA. 2015. The crystal structure of the Hazara virus nucleocapsid protein. BMC Struct Biol 15:24. doi: 10.1186/s12900-015-0051-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surtees R, Dowall SD, Shaw A, Armstrong S, Hewson R, Carroll MW, Mankouri J, Edwards TA, Hiscox JA, Barr JN. 2016. Heat shock protein 70 family members interact with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Hazara virus nucleocapsid proteins and perform a functional role in the nairovirus replication cycle. J Virol 90:9305–9316. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00661-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Te Velthuis AJW. 2014. Common and unique features of viral RNA-dependent polymerases. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:4403–4420. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reguera J, Gerlach P, Cusack S. 2016. Towards a structural understanding of RNA synthesis by negative strand RNA viral polymerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 36:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pflug A, Guilligay D, Reich S, Cusack S. 2014. Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature 516:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerlach P, Malet H, Cusack S, Reguera J. 2015. Structural insights into bunyavirus replication and its regulation by the vRNA promoter. Cell 161:1267–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr JN, Wertz GW. 2004. Bunyamwera bunyavirus RNA synthesis requires cooperation of 3´- and 5´-terminal sequences. J Virol 78:1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohl A, Dunn EF, Lowen AC, Elliott RM. 2004. Complementarity, sequence and structural elements within the 3′ and 5′ non-coding regions of the Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus S segment determine promoter strength. J Gen Virol 85:3269–3278. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raju R, Kolakofsky D. 1989. The ends of La Crosse virus genome and antigenome RNAs within nucleocapsids are base paired. J Virol 63:122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolakofsky D. 2016. dsRNA-ended genomes in orthobunyavirus particles and infected cells. Virology 489:192–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchholz UJ, Finke S, Conzelmann K-K. 1999. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J Virol 73:251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hass M, Westerkofsky M, Müller S, Becker-Ziaja B, Busch C, Günther S. 2006. Mutational analysis of the Lassa virus promoter. J Virol 80:12414–12419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01374-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Głów D, Pianka D, Sulej AA, Kozłowski ŁP, Czarnecka J, Chojnowski G, Skowronek KJ, Bujnicki JM. 2015. Sequence-specific cleavage of dsRNA by Mini-III RNase. Nucleic Acids Res 43:2864–2873. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto Y, Ohta K, Goto H, Nishio M. 2016. Parainfluenza virus chimeric mini-replicons indicate a novel regulatory element in the leader promoter. J Gen Virol 97:1520–1530. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto Y, Ohta K, Kolakofsky D, Nishio M. 2017. A point mutation in the RNA-binding domain of human parainfluenza virus type 2 nucleoprotein elicits an abnormally enhanced polymerase activity. J Virol 91:e02203-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02203-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.