Abstract

The International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) M7 guideline allows the use of in silico approaches for predicting Ames mutagenicity for the initial assessment of impurities in pharmaceuticals. This is the first international guideline that addresses the use of quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models in lieu of actual toxicological studies for human health assessment. Therefore, QSAR models for Ames mutagenicity now require higher predictive power for identifying mutagenic chemicals. To increase the predictive power of QSAR models, larger experimental datasets from reliable sources are required. The Division of Genetics and Mutagenesis, National Institute of Health Sciences (DGM/NIHS) of Japan recently established a unique proprietary Ames mutagenicity database containing 12140 new chemicals that have not been previously used for developing QSAR models. The DGM/NIHS provided this Ames database to QSAR vendors to validate and improve their QSAR tools. The Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project was initiated in 2014 with 12 QSAR vendors testing 17 QSAR tools against these compounds in three phases. We now present the final results. All tools were considerably improved by participation in this project. Most tools achieved >50% sensitivity (positive prediction among all Ames positives) and predictive power (accuracy) was as high as 80%, almost equivalent to the inter-laboratory reproducibility of Ames tests. To further increase the predictive power of QSAR tools, accumulation of additional Ames test data is required as well as re-evaluation of some previous Ames test results. Indeed, some Ames-positive or Ames-negative chemicals may have previously been incorrectly classified because of methodological weakness, resulting in false-positive or false-negative predictions by QSAR tools. These incorrect data hamper prediction and are a source of noise in the development of QSAR models. It is thus essential to establish a large benchmark database consisting only of well-validated Ames test results to build more accurate QSAR models.

Introduction

Presently, more than 140 million chemical substances are listed in the CAS registry (https://www.cas.org/), and this number is increasing at a rate of approximately 4000 chemical substances/day. Among these chemicals, approximately 100000 are industrially produced and present in our living environments, and some of these may have adverse effects on human health. These toxic chemical substances are generally identified and evaluated by toxicological tests in animals and other organisms. For assessing the safety of all common chemical substances, however, individual toxicological testing is not feasible considering labour, time, cost and animal welfare issues. Given the rapid expansion in the number of industrial chemicals, international organisations and regulatory authorities involved in the regulation of chemical substances have expressed the need for effective screening tools to promptly and accurately identify chemical substances with potential adverse effects without conducting actual toxicological studies.

Quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) is one promising area of computational toxicology that attempts to predict the potential adverse effects of a chemical based on its chemical structure. Predictions from QSAR can be useful for prioritising chemical substances for actual toxicological studies, thereby minimising the need for animal studies. In fact, various QSAR tools are currently used for screening lead compounds at the search stages of pharmaceutical development and for predicting the toxicity of industrial chemicals, agrochemicals, food additives and cosmetic materials. Much effort has been invested in the development of QSAR models for predicting Ames mutagenicity, among other toxicological endpoints, owing to the significant amount of the necessary Ames test data that have already been accumulated (1). The Ames test, developed by Bruce Ames is a short-term bacterial reverse mutation assay specifically designed to detect a wide range of chemical substances that can cause genetic damage leading to gene mutations (2). The Ames test is globally used as an initial screening method to determine the mutagenic potential of new chemicals and drugs. The test is also used for submission of data to regulatory agencies for registration or acceptance of many chemicals. QSAR models for predicting Ames mutagenicity are generally divided into two classes according to the mode of operation: rule-based (expert system) and statistical-based (QSAR system). In rule-based systems, qualitative prediction is based on the presence of structural features (termed alerts) of the test chemicals. Early systems were based on the work of James and Elisabeth Miller (3) and the subsequent work of John Ashby and Raymond Tennant, who systemised the relationship between chemical structures and the observed toxic outcomes (4–6). Alternatively, statistical-based prediction is based on physicochemical properties expressed in terms of molecular descriptors or structural fragments that are known to correlate with biological activities (7–9). The quantitative relationship between biological activity and the molecular descriptors is calculated by a machine learning algorithm.

The International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) M7 guideline for the assessment and control of mutagenic impurities in pharmaceuticals to limit potential carcinogenic risk was recently established (10). This guideline permits the use of QSAR tools for predicting Ames mutagenicity for the initial assessment of impurities in pharmaceuticals. This in silico approach is reasonable for this purpose because impurities in pharmaceuticals are usually present at very low levels and sometimes impossible to isolate and purify for actual toxicological study. The ICH-M7 is the first international guideline that addresses the use of QSAR models instead of actual toxicological study for human health assessment. Thus, QSAR is no longer merely a prediction or screening tool, but can be regarded as a mutagenicity test under ICH-M7. The guideline requires two QSAR prediction methodologies, one rule-based and one statistical-based, for acceptance. Negative prediction from both QSAR methodologies is sufficient to conclude that the impurity is not of mutagenic concern, while a positive prediction from either methodology can be regarded as a positive indication of mutagenic risk. Expert review is also recommended to support conclusions on the biological relevance of any positive, negative, conflicting or inconclusive QSAR prediction. Thus, the full QSAR approach under ICH-M7 (using the two QSAR methodologies and the expert review) is designed to maximise the sensitivity for identifying mutagenic chemicals (11–14). However, accurate prediction by QSAR (i.e. the ability to distinguish mutagenic from non-mutagenic) is more important in practice.

Over the last two decades, many QSAR tools for predicting Ames mutagenicity have been developed. Some are commercially available, whereas others were developed as freeware by international organisations or academia (1). All of these QSAR tools have been validated to define predictive power and establish fitness for use. Sensitivity (the ability to detect mutagens) and specificity (the ability to detect non-mutagens) are routinely evaluated as performance metrics. Other statistical measures include accuracy (proportion of correct predictions), negative predictivity (true Ames negatives among all negative predictions), positive predictivity (true Ames positives among all positive predictions), and chemical coverage. From a regulatory perspective, QSAR tools that display a high sensitivity, high negative predictivity and wide coverage are the most desirable as they minimise false-negative outcomes and maximise chemical space in prediction.

Several reports have evaluated the performance of commercial QSAR tools for the prediction of Ames mutagenicity (15–19). In general, these QSAR tools demonstrate high sensitivity when analysing publicly available datasets. This is predicted because the QSAR models were initially built and trained using public data, so there is substantial overlap of chemical space between the training chemicals and the query chemicals. Therefore, validation of QSAR tool performance using public datasets may be overly optimistic. To perform fair validation of these tools, a proprietary dataset that has not been used for building the QSAR model should be employed (external validation). Such evaluations would reflect true performance to predict the Ames mutagenicity of new chemical substances. Also, integrating the proprietary dataset as training data (after validation) further expands the chemical space in prediction, leading to increased performance of QSAR tools. Thus, proprietary datasets are of value both to validate and improve QSAR predictions.

The Division of Genetics and Mutagenesis, National Institute of Health Sciences of Japan (DGM/NIHS) recently established a unique proprietary Ames database consisting of 12140 new chemical substances. The Ames test reports were submitted to the Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare (MHLW) in accordance with the Industrial Safety and Health Act in Japan since 1979. These test reports were originally undisclosed but the outcomes (positive or negative) were made available to DGM/NIHS for validation, development and improvement of QSAR tools. The Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project was started in 2014 in collaboration with 12 QSAR vendors from the USA, UK, Italy, Spain, Bulgaria, Sweden and Japan (Table 1). Based on the hypothesis that expansion of training data enhances the predictive power of QSAR tools, a three-phase challenge was designed. This report details the outcomes for all stages of the Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project.

Table 1.

Participants in Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project

| QSAR vendor | QSAR tool | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Lhasa Limited (UK) | a. Derek Nexus | Rule |

| b. Sarah Nexus | Statistical | |

| 2. MultiCASE Inc (USA) | c. CASE Ultra statistical-based | Statistical |

| d. CASE Ultra rule-based | Rule | |

| 3. Leadscope Inc (USA) | e. Leadscope statistical-based | Statistical |

| f. Leadscope rule-based | Rule | |

| 4. Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS (Italy) | g. CAESAR | Statistical |

| h. SARPY | Rule | |

| i. KNN | Statistical | |

| 5. LMC - Bourgas University (Bulgaria) | j. TIMES_AMES | Rule |

| 6. Istituto Superiore di Sanita (Italy) | k. Toxtree | Rule |

| 7. Prous Institute (Spain) | l. Symmetry | Statistical |

| 8. Swedish Toxicology Science Research Center (Sweden) | m. AZAMES | Statistical |

| 9. Fujitsu Kyushu Systems Limited (Japan) | n. ADMEWORKS | Statistical |

| 10. IdeaConsult Ltd. (Bulgaria) | o. AMBIT | Statistical |

| 11. Molecular Networks GmbH and Altamira LLC (USA) | p. ChemTune•ToxGPS | Statistical |

| 12. Simulations Plus, Inc (USA) | q. MUT_Risk | Statistical |

Materials and Methods

Proprietary dataset

The Ames dataset for this project was obtained from the list of 20761 chemical compounds subject to the Industrial Safety and Health Act (ANEI-HOU) of Japan. The Ames test by ANEI-HOU initiated in 1979 (20). The purpose of the ANEI-HOU is to secure safety and health in the workplace. For chemical substances to be newly manufactured or imported in excess of 100 kg per year, ANEI-HOU stipulates that producers conduct hazard investigations in advance and to notify the MHLW of the results. As part of the hazard investigation, the Ames test or its equivalent (e.g. rodent carcinogenicity testing) is required. The Chemical Hazards Control Division, Industrial Safety and Health Department, Labor Standards Bureau, MHLW of Japan is responsible for monitoring industries under the ANEI-HOU. They summarised the Ames test results of 20761 chemical compounds that were subjected to ANEI-HOU from 1979 to 2014 and provided the list to DGM/NIHS for this project. The Ames tests were conducted by chemical companies, pharmaceutical companies and contract research organisations under GLP compliance according to the ANEI-HOU test guideline (20). The test guideline basically requires five Ames strains, ‘S. thyphimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA1537 and E. coli WP2 uvrA’, which is similar to the requirement of the OECD guideline TG471 (21). ANEI-HOU classifies the Ames test results into three classes:

Class A: Strongly positive. The chemical generally induces more than 1000 revertant colonies per mg of at least one Ames test strain in the presence or absence of rat S9.

Class B: Positive. The chemical induces at least a 2-fold increase in revertant colonies (but less than for Class A compounds) compared to the negative control in at least one Ames strain in the presence or absence of rat S9.

Class C: Negative, no revertants increased (<2-fold) (neither Class A nor B).

The study reports of the Ames tests were peer reviewed by the ANEI-HOU committee comprising several Ames test experts from academia and National Institutes, and the results (A, B or C) were authorised. The list provided for this project included the chemical name and the Ames result (A, B or C). Other information concerning Ames tests such as bacterial strain, presence or absence of rat S9, solvent, cytotoxicity and dose−response were not provided. The results of the Ames tests for these chemical compounds subject to ANEI-HOU are confidential and cannot be disclosed except for those designated as Class A. Class A chemicals are disclosed according to the Guidelines for Preventing Health Impairment by Chemical Substances in the ANEI-HOU. Class A chemicals are published on the MHLW website http://anzeninfo.mhlw.go.jp/user/anzen/kag/ankgc03.htm.

Data curation

The DGM/NIHS carefully investigated the chemical compounds on the list and selected chemicals for which Ames test results could be appropriately incorporated into QSAR models. Mixtures, polymers, metals and condensates were excluded from this study. Counter-ions were removed after neutralisation, and acidic/basic groups were neutralised. Duplicate structures were also removed. Finally, 12140 chemical substances were included in the dataset for this project (Table 2). Each chemical is identified by serial ID, ANEI No., chemical name and simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES), and the result of the Ames test is appended (Class A, B or C). Among 12140 chemicals, 7788 also have a CAS registry number (64%), which was added to the list. For at least 85% of the included chemicals, there is no available Ames test result in either public domain databases or the databases of the QSAR vendors (Dr. R. Saiakhov, MultiCASE Inc., personal communication). Thus, these chemicals have not been included in training sets for pre-existing QSAR model development.

Table 2.

Number of Chemicals in Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project

| Class | Phase I (2014–2015) | Phase II (2015–2016) | Phase III (2016–2017) | Total (2014–2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A | 183 (4.7%) | 253 (6.6%) | 236 (5.4%) | 672 (5.5%) |

| Class B | 383 (9.8%) | 309 (8.1%) | 393(8.9%) | 1085 (8.9%) |

| Class C | 3336 (85.5%) | 3267 (85.3%) | 3780 (85.7%) | 10383 (85.6%) |

| Total | 3902 | 3829 | 4409 | 12140 |

| Only chemicals with >800 mw | ||||

| Class A | 3 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.3) |

| Class B | 16 (9.7) | 1 (2.4) | 9 (3.8) | 26 (5.8) |

| Class C | 146 (88.5) | 39 (95.1) | 229 (95.4) | 414 (92.8) |

| Subtotal | 165 | 41 | 240 | 446 |

Project design

The Ames/QSAR International Challenge Project was first announced at the QSAR 2014 Conference, Milan, Italy, in June 2014. Twelve QSAR vendors from seven countries responded to the announcement and participated in the project. Some QSAR vendors challenged multiple QSAR models differing by methodology or version (Table 1). The challenge project was conducted in three phases from 2014 to 2017. The DGM/NIHS provided a list of about 4000 chemicals in each phase without their Ames test results to the QSAR vendors. The QSAR vendors predicted the Ames mutagenicity using their QSAR tools and reported the results to the DGM/NIHS. The DGM/NIHS validated the performance of the QSAR tools (sensitivity, specificity and other criteria) and disclosed the Ames results. Some QSAR tools were improved or adjusted by using the Ames results as training data before the next phase. Table 2 summarises the number of chemicals in each Ames mutagenicity class for each phase. A confidential agreement not to disclose the chemical names and Ames results except for Class A chemicals was obtained from all participating vendors before starting the project. The Class A chemicals in this project are available at the AMES/QSAR website (http://www.nihs.go.jp/dgm/amesqsar.html).

QSAR tools

In total, 12 QSAR vendors using 17 different tools participated in this project (Table 1). The detailed features of each QSAR tool are described in Supplement 1, available at Mutagenesis Online.

Analysis of QSAR tool performance

The Ames mutagenicity predictions of all QSAR tools were compared to the actual Ames test results (Class A−C). Class A and B were combined for calculating all performance metrics except sensitivity (the ability to detect mutagens). For binary classifiers, performance metrics can be generated by drawing values from a 2 × 2 contingency table of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN) and true negatives (TN) (Table 3). Sensitivity, specificity (ability to detect non-mutagens), positive and negative predictivity (correctly predicted mutagens and non-mutagens, respectively), accuracy, balanced accuracy and coverage were calculated for these tables. Sensitivity-A (ability to detect strong mutagens) was separately calculated by excluding Class B predictions. Furthermore, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) was derived for each tool. The MCC measures the quality of binary classifications by accounting for true and false positives and negatives as well as the difference in the sizes of the positive and negative classes. A coefficient of 1 represents a perfect prediction, while −1 indicates total disagreement between the prediction and observation. An MCC of 0 indicates a prediction no better than random selection (22). The performance metrics and their calculation formulae are shown in Table 4. Additionally, the TP rate (sensitivity) against the FP rate (1-specificity) was plotted. The resulting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) graph allows a visual comparison of the performance of each QSAR tool.

Table 3.

2 × 2 (2 × 3) contingency matrix for Ames mutagenicity classification

| Experimental Ames mutagenicity class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A (Strong positive) | Class B (Positive) | Class C (Negative) | ||

| QSAR Prediction Class | Positive | True Positive (A) (TPA) | True Positive (B) (TPB) | False Positive (FP) |

| Negative | False Negative (FN) | True Negative (TN) | ||

| True Positive (TP) = TPA + TPB | ||||

Table 4.

Performance metrics used to evaluate classifiers

| Performance metric | Calculation and description |

|---|---|

| A-Sensitivity (A-SENS) |

TPA/(TPA + FN) Measures the ability of a QSAR tool to detect strong Ames positives compounds correctly. |

| Sensitivity (SENS) |

TP/(TP + FN) Measures the ability of a QSAR tool to detect Ames positives compounds correctly. |

| Specificity (SPEC) |

TN/(FP + FN) Measures the ability for a QSAR tool to detect negatives compounds. |

| Accuracy (ACC) |

(TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) Assesses a QSAR tool’s overall performance by returning the fraction of compounds which were correctly predicted. |

| Balanced Accuracy (BA) |

(SENS + SPEC)/2

Assesses the overall model performance, giving each class equal weight. |

| Positive Prediction Value (PPV) |

(TP)/(TP + FP) Indicates how frequently positive predictions are correct. |

| Negative Prediction Value (NPV) |

TN/(TN + FN) Indicates how often negative predictions are correct. |

| Mathews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) |

Assesses the overall performance of the model. Values can range from −1 to 1, which is in contrast to the other metrics in this table which range from 0 to 1. |

| Coverage (COV) |

(TP + TN + FP + FN)/Total

Evaluates the proportion of compounds for which the model can make a positive or negative prediction. |

Results and Discussion

The predictions of each QSAR tool are described and discussed in Supplement 2, available at Mutagenesis Online. Some participants have published their own papers related to the AMES/QSAR project in this special issue where they discuss individual QSAR tool performance in detail. Here, we describe the general results and discuss the overall predictive performance of these QSAR tools.

The Ames test data

The 12140 Ames test results in our dataset were selected from the ANEI-HOU database provided by MHLW for this challenge project. The database is confidential and not in the public domain except for Class A chemicals. Although all the Ames studies were peer reviewed by genotoxicity experts, we were not allowed to access the study reports. Rather, only the test result (Class A, B or C) was provided. Thus, information on experimental conditions (i.e. the Ames strain showing positive results, whether metabolic activation was required) was not available to the study participants.

The list of 12140 chemical substances was made available in three phases from 2014 to 2017 (Table 2). Among 12140 chemicals, all 7788 chemicals possessing a CAS registry number (64%) were evaluated by the QSAR models in Phase I or II, while almost all chemicals in Phase III had no CAS registration. Interestingly, while we arbitrarily split the chemicals into phases without considering the proportions of Class A, B and C, the proportions were roughly constant in each phase (approximately 5% Class A, 10% Class B and 85% Class C). Matsushima et al. previously reported the proportion of Ames mutagens among 4000 new chemical substances subject to ANEI-HOU until 1990 in Japan (23) and observed proportions of 3% Class A, 10% Class B and 87% Class C. At the DGM/NIHS, of the 305 commercial chemicals evaluated for Ames mutagenicity from 1978 to 1991, including food additives, industrial chemicals, experimental reagents, pharmaceuticals, environmental chemicals, dyes, flavourings and natural products, 13 (4.3%) were Class A, 36 (11.8%) Class B and 256 (83.9%) Class C (24). Therefore, the proportions in the three Ames classes have been relatively constant over time, with 13−16% of new agents deemed strongly positive or positive, likely reflecting the proportion of mutagenic commercial chemicals used in Japan, although the ANEI-HOU data included highly reactive synthetic intermediates, which are not final commercial products. However, in a survey of the US National Toxicology Program (NTP) database (25), the overall proportion of Ames mutagens was 35% (522/1497), while in the US EPA Gene-Tox database that summarised published Ames studies, 56% (603/1078) of the chemicals were positive (26). Many of the NTP chemicals were tested due to suspicion of carcinogenicity or mutagenicity or because they were structural analogues of known mutagens. The high proportion of Ames-positive chemicals in the EPA Gene-Tox database, which mainly consists of chemicals evaluated in published articles, presumably reflects publication bias for mutagens over non-mutagens (i.e. positive results over negative results). Thus, the NTP database and the EPA Gene-Tox database may not reflect the actual proportion of commercial chemicals with mutagenic properties. Zeiger and Margolin investigated the proportion of Ames mutagens among 100 randomly selected chemicals identified by the US National Academy of Science (1984) from a subset of all chemicals in commerce and determined that 22% were Ames mutagens (27). Overall, it appears that roughly 15−20% of chemicals in commerce are Ames mutagens. This statistical information is valuable for quality control of Ames mutagenesis datasets and for appropriate allocation of resources to assure the safety of commercial chemicals.

Strong mutagens

In this challenge, 672 strong Ames mutagens (Class A) were included (available at http://www.nihs.go.jp/dgm/amesqsar.html). These compounds must be publicly disclosed in advance according to the ANEI-HOU to protect workers from exposure. Ames tests are generally used for screening carcinogens because there is a strong correlation between Ames mutagens and rodent carcinogens. Indeed, approximately 87% of Ames mutagens are carcinogenic in rats or mice (28,29). However, the correlation between the quantitative results of the Ames test (number of revertants) and the strength of rodent carcinogenicity is generally poor (30). In other words, Class A chemical substances producing >1000 revertants /mg in the Ames test do not necessarily have strong carcinogenic activity. Mono-functional alkyl halides, certain aromatic amines and aromatic nitro derivatives are representative strong mutagens in Ames tests and are known to show weak carcinogenicity in rodents (31,32). Therefore, it may be better to regard Class A compounds as certainly mutagenic but not necessarily as strongly carcinogenic. Class A compounds can be thought of as having an alert structure strongly related to mutagenicity. Regulatory authorities have a vested interest in the ability of QSAR tools to identify strong mutagens. However, despite being Ames Class A, 8 compounds in Phase I, 4 in Phase II and 6 in Phase III (Supplement 3, available at Mutagenesis Online) were not predicted as positive by all QSAR tools used in this study. In addition, 11 Class A compounds in Phase I, 5 in Phase II and 10 in Phase III (Supplement 4, available at Mutagenesis Online) were predicted as Ames-positive by only one QSAR tool. These compounds are thus regarded as false negative for all other QSAR tools. Such novel mutagens may possess new alerts related to Ames mutagenicity that have not been reported and are thus important training items for QSAR tools. Accumulating data on mutagenic substances with novel and unique structures not only expands the chemical space of mutagenic chemicals but may also facilitate further improvements to the predictive power of QSAR tools.

Predictive power of QSAR tools

There are many reports evaluating the predictive power of QSAR tools for Ames mutagenicity (15–19). Hansen et al. built a benchmark dataset consisting of 6512 chemicals with Ames mutagenicity information from published literature (54% positive) and evaluated the performance of three commercial QSAR tools, including DEREK and MultiCASE, and four non-commercial machines leaning QSAR models (16). DEREK and MultiCASE demonstrated good predictive power, with sensitivity values of 73 and 78%, respectively. Hillebrecht and his colleagues at F. Hoffmann-La Roche evaluated the predictive power of 4 QSAR tools (DEREK, Toxtree, MultiCASE and Leadscope) using a large high-quality dataset comprised of both published results and Roche’s proprietary data (17). Satisfactory performance metrics were demonstrated for the public data (Accuracy: 66.4−75.4%, Sensitivity: 65.2−85.2%, Specificity: 53.1−82.9%), whereas a marked decrease in sensitivity was found for predictions using Roche’s proprietary data (Accuracy: 73.1−85.5%, Sensitivity: 17.4−43.4%, Specificity: 77.5−93.9%). Similarly, Cariello at GlaxoSmithKline used DEREK and TOPKAT to predict company proprietary data, and found sensitivity values of only 46.3 and 25.6%, respectively (33). One factor contributing to the poor sensitivity of QSAR tools for predicting proprietary pharmaceutical compounds is the low proportion of positives (12.9 and 20% positive in Roche and GlaxoSmithKline proprietary datasets, respectively) compared to public databases (e.g. 54% positive in the Hansen dataset), as this decreases the probability of correctly predicting Ames positives by chance. Another possible contributing factor is the unique molecular structure of many new pharmaceutical compounds compared to compounds in public domain datasets.

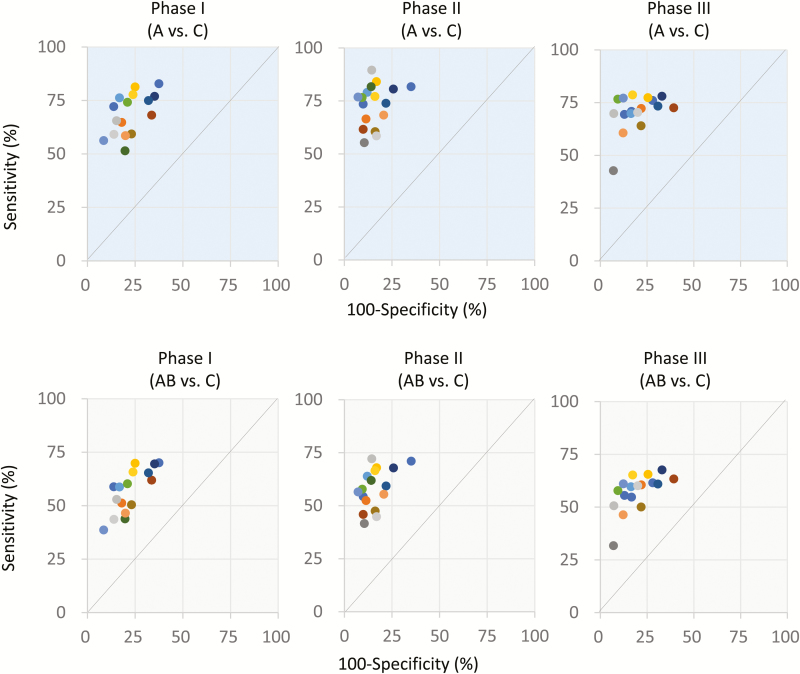

The Ames test data used in the AMES/QSAR challenge project were also from a proprietary dataset (ANEI-HOU) and the proportion of positives was similarly low (14.5%; Table 2). However, most of the QSAR tools exhibited relatively high sensitivity in Phase I, in which a substantial proportion of compounds had CAS registry numbers (Table 5). The average A-Class sensitivity and overall sensitivity in Phase I were 68.7 and 56.7%, respectively (Table 8). This relatively high sensitivity may be due to the types of Ames-positive chemicals included in the ANEI-HOU database, most of which are industrial chemicals produced or used by many companies. Most of these Ames-positive chemicals are also of low molecular weight (Table 2) (15) and probably have few well-described reactive groups, such as alkylating agents, aromatic nitro group compounds and epoxides. Another possible reason for this high sensitivity in Phase I is the quality of data. Ames tests submitted to ANEI-HOU are conducted strictly under GLP, and the results are peer reviewed by an ANEI-HOU committee. Further, positive results are reviewed by genotoxicity experts. Therefore, test results could be easily predicted for the ANEI-HOU compounds. Although some QSAR tools sacrificed sensitivity to increase specificity (Figure 1), most showed a good balance between sensitivity and specificity, resulting in high accuracy. The average sensitivity and accuracy for all QSARS tools in Phase I were 77.7% and 74.7%, respectively, values comparable to previous QSAR performance results using a public dataset (17).

Table 5.

Summary of the performance metrics of QSAR tools in Phase I challenge with 3902 chemicals

| Vendors | QSAR tools (module) | A-SENS (%) | SENS (%) | SPEC (%) | ACC (%) | BA (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | MCC | COV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lhasa Limited | *Derek_Nexus v.4.0.5 | 72.1 | 58.8 | 86.2 | 82.2 | 72.5 | 41.9 | 92.5 | 0.39 | 100.0 |

| *Sarah Nexus v. 1.2 (model v.1.1.2) | 64.7 | 51.2 | 82.0 | 77.6 | 66.6 | 32.3 | 91.0 | 0.28 | 80.0 | |

| MultiCASE Inc | *BM_PHARMA v1.5.2.0 (Statistical approach; SALM/ ECOLI consensus) | 65.5 | 52.9 | 84.7 | 80.1 | 68.8 | 37.1 | 91.3 | 0.33 | 90.5 |

| *GT_EXPERT v1.5.2.0 (Rule based) | 81.3 | 69.8 | 75.0 | 74.2 | 72.4 | 32.8 | 93.4 | 0.34 | 91.0 | |

| Leadscope Inc | *Statistical-based (QSAR) | 76.2 | 58.7 | 83.2 | 79.8 | 71.0 | 35.8 | 92.6 | 0.34 | 86.0 |

| *Rule-based (alerts) | 74.1 | 60.2 | 79.0 | 76.3 | 69.6 | 32.0 | 92.3 | 0.31 | 94.3 | |

| Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS | *CAESAR (training set based on Katius et al.) | 76.9 | 69.5 | 64.8 | 65.5 | 67.2 | 25.1 | 92.6 | 0.25 | 99.6 |

| *SARPY (training set based on Katius et al.) | 68.1 | 61.9 | 66.3 | 65.7 | 64.1 | 23.8 | 91.1 | 0.20 | 99.6 | |

| LMC-Bourgas University | TIMES-AMES (in domain TIMES model) | 79.4 | 49.5 | 88.8 | 81.8 | 68.9 | 46.1 | 89.7 | 0.37 | 14.5 |

| *TIMES-AMES (including out of domain) | 59.3 | 50.4 | 76.9 | 73.0 | 63.7 | 26.9 | 90.1 | 0.22 | 99.9 | |

| Istituto Superiore di Sanita | *ToxTree 2.6.6 | 74.9 | 65.3 | 68.0 | 67.6 | 66.7 | 25.7 | 92.0 | 0.24 | 99.9 |

| Prous Institute | *Symmetry S. typhimurium (Ames) |

51.4 | 43.8 | 80.3 | 75.0 | 62.1 | 27.4 | 89.4 | 0.20 | 99.9 |

| Swedish Toxicology Science Research Center | *Swetox AZAMES | 56.2 | 38.6 | 91.5 | 83.9 | 65.1 | 43.1 | 89.9 | 0.32 | 97.1 |

| Fujitsu Kyushu Systems Limited | *ADMEWORKS/Predictor Ames-V71 | 58.5 | 46.5 | 80.1 | 76.0 | 63.3 | 24.2 | 91.6 | 0.20 | 57.7 |

| IdeaConsult Ltd. | *Ambit consensus model | 59.1 | 43.6 | 86.1 | 80.0 | 64.9 | 34.4 | 90.1 | 0.27 | 93.6 |

| Molecular Networks GmbH and Altamira LLC | *ChemTune•ToxGPS Ames | 77.7 | 65.7 | 76.1 | 74.5 | 70.9 | 32.9 | 92.6 | 0.33 | 90.3 |

| Simulations Plus, Inc | *MUT_Risk-0 | 82.8 | 70.0 | 62.5 | 63.6 | 66.3 | 24.8 | 92.2 | 0.23 | 83.6 |

| MUT_Risk-1 | 62.0 | 48.0 | 84.3 | 78.9 | 66.2 | 35.1 | 90.2 | 0.29 | 83.6 |

Table 8.

Averages and ranges of the performance metrics of QSAR tools in the Ames/QSAR challenge project

| Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Sensitivity (%) | 68.7 (51.4–82.8) | 73.2 (55.3–89.5) | 70.2 (42.7–78.6) |

| Sensitivity (%) | 56.7 (38.6–70.0) | 58.0 (41.6–72.1) | 57.1 (31.7–67.6) |

| Specificity (%) | 77.7 (62.5–91.5) | 84.2 (64.9–92.8) | 79.9 (60.7–93.0) |

| Accuracy (%) | 74.7 (63.6–83.9) | 80.3 (65.8–87.7) | 76.7 (61.1–87.3) |

| Balanced accuracy (%) | 67.2 (62.1–72.5) | 71.1 (64.0–78.9) | 68.5 (62.0–74.4) |

| MCC | 0.28 (0.20–0.39) | 0.37 (0.24–0.50) | 0.31 (0.17–0.44) |

| Coverage (%) | 91.4 (57.7–100) | 89.1 (22.7–100) | 92.3 (74.5–100) |

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) graph of Ames mutagenicity prediction for the QSAR tools evaluated in this study. Sensitivity to Class A or Class A + B chemical and specificity to class C chemicals are presented. Each dot represents a QSAR tool used.

In the Phase II challenge, the predictive power of almost all QSAR tools was much improved (Table 6, Figure 1) and the averages of all performance metrics were higher than in Phase I (Table 8). Theoretically, this is expected due to the additional training data supplied during Phase I. However, not all QSAR tools were updated by incorporating Phase I data as a training dataset (Table 6). Rather, some vendors improved their QSAR tools by other means and used these updated versions in subsequent phases. The details on the updated information used by some QSAR tool vendors are presented in Supplement 2, available at Mutagenesis Online. On the other hand, no significant improvements in overall performance metrics were observed from Phase II to Phase III (Tables 7 and 8). This may be due to the unique molecular structures of Phase III chemicals. Phase III chemicals consisted mainly of non-CAS# compounds and the proportion of high molecular weight chemicals (800 mw or more) was greater than in Phase II. The greater proportion of larger more complex chemicals may explain the lower than expected predictive power. Nonetheless, almost all QSAR tools were considerably improved over the course of this challenge project, demonstrating higher predictive power than before Phase I (Figure 1). In fact, some QSAR tools exhibited 85% accuracy or higher for the predicted compounds.

Table 6.

Summary of the performance metrics of QSAR tools in Phase II challenge with 3829 chemicals

| Vendors | QSAR tools (module) | A-SENS (%) | SENS (%) | SPEC (%) | ACC (%) | BA (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | MCC | COV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lhasa Limited | *Derek_Nexus v.4.2.0 | 73.5 | 54.3 | 90.1 | 84.8 | 72.2 | 48.4 | 92.0 | 0.42 | 100.0 |

| Sarah Nexus v. 1.2 (model v.1.1.2) | 61.0 | 46.0 | 88.2 | 82.2 | 67.1 | 39.0 | 90.9 | 0.32 | 82.9 | |

| Sarah Nexus v. 2.0.1 (model v.1.1.19) | 63.7 | 48.3 | 89.0 | 83.4 | 68.7 | 41.4 | 91.5 | 0.35 | 84.1 | |

| *Sarah Nexus v. 2.0.1 (model v.1.1.19)+NIHS1 | 66.5 | 52.4 | 88.6 | 83.5 | 70.5 | 42.7 | 92.0 | 0.38 | 83.3 | |

| MultiCASE Inc | *BM_PHARMA v1.5.2.0 (Statistical approach; SALM/ECOLI consensus) | 89.5 | 72.1 | 85.6 | 83.5 | 78.9 | 48.4 | 94.2 | 0.50 | 65.3 |

| *GT_EXPERT v1.5.2.0 (Rule based) | 84.1 | 67.9 | 83.1 | 80.8 | 75.5 | 42.1 | 93.5 | 0.43 | 89.4 | |

| Leadscope Inc | *Statistical-based QSAR (rebuild I) | 79.0 | 63.9 | 88.0 | 84.5 | 76.0 | 47.2 | 93.6 | 0.46 | 90.7 |

| *Rule-based (Alerts) | 76.6 | 57.8 | 90.6 | 85.8 | 74.2 | 51.6 | 92.6 | 0.46 | 93.8 | |

| Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS | *CAESAR (training set based on Katius et al.) | 80.6 | 67.8 | 74.2 | 73.3 | 71.0 | 31.2 | 93.1 | 0.32 | 99.9 |

| *SARPY (training set based on Katius et al. + Phase I) | 61.6 | 45.9 | 90.1 | 83.7 | 68.0 | 44.0 | 90.7 | 0.35 | 97.7 | |

| *KNN (training set based on Hansen et al. + Phase I) | 55.3 | 41.6 | 89.5 | 82.4 | 65.5 | 40.7 | 89.8 | 0.31 | 98.8 | |

| LMC-Bourgas University | TIMES-AMES (In domain TIMES model) | 80.0 | 51.0 | 93.5 | 87.1 | 72.3 | 58.2 | 91.5 | 0.47 | 18.0 |

| *TIMES-AMES (Including out of domain) | 60.5 | 47.5 | 83.8 | 78.4 | 65.7 | 33.4 | 90.3 | 0.27 | 98.0 | |

| Istituto Superiore di Sanita | *ToxTree 2.6.6 | 73.9 | 59.3 | 78.1 | 75.3 | 68.7 | 31.7 | 91.8 | 0.30 | 100.0 |

| Prous Institute | *Symmetry S. typhimurium (Ames) |

81.7 | 61.9 | 85.9 | 82.4 | 73.9 | 43.0 | 92.9 | 0.41 | 99.9 |

| Swedish Toxicology Science Research Center | *Swetox AZAMES | 76.8 | 56.5 | 92.8 | 87.7 | 74.7 | 56.3 | 92.9 | 0.49 | 93.1 |

| Fujitsu Kyushu Systems Limited | *ADMEWORKS/Predictor Ames-V71 | 68.3 | 55.4 | 79.3 | 74.7 | 67.4 | 39.1 | 88.1 | 0.31 | 22.7 |

| IdeaConsult Ltd. | *Ambit consensus model | 58.5 | 44.8 | 83.1 | 77.5 | 64.0 | 31.4 | 89.8 | 0.24 | 100.0 |

| Molecular Networks GmbH and Altamira LLC | ChemTunes•ToxGPS Ames (original) | 70.5 | 56.9 | 91.6 | 86.5 | 74.3 | 54.4 | 92.4 | 0.48 | 96.2 |

| *ChemTunes•ToxGPS Ames (enhanced) | 77.1 | 66.5 | 83.9 | 81.3 | 75.2 | 42.3 | 93.4 | 0.42 | 92.7 | |

| Simulations Plus, Inc | *MUT_Risk-0 | 81.7 | 71.0 | 64.9 | 65.8 | 68.0 | 27.4 | 92.3 | 0.27 | 89.9 |

Table 7.

Summary of the performance metrics of QSAR tools in Phase III challenge with 4409 chemicals

| Vendors | QSAR tools (module) | A-SENS (%) | SENS (%) | SPEC (%) | ACC (%) | BA (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | MCC | COV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lhasa Limited | *Derek Nexus v. 5.0.1 | 70.8 | 54.7 | 83.3 | 79.2 | 69.0 | 35.2 | 91.7 | 0.32 | 100.0 |

| Sarah Nexus v. 2.0.1 (model v. 1.1.19) | 59.1 | 44.0 | 82.3 | 77.3 | 63.2 | 27.7 | 90.6 | 0.22 | 80.2 | |

| Sarah research prottype prediction | 83.1 | 70.4 | 74.4 | 73.8 | 72.4 | 32.7 | 93.4 | 0.34 | 67.7 | |

| *Sarah Nexus v. 2.0.1 (model v. 1.1.19)+ NIHS1 & NIHS2 | 72.2 | 60.5 | 78.1 | 75.7 | 69.3 | 30.5 | 92.6 | 0.30 | 79.5 | |

| MultiCASE Inc | *Statistical approach; SALM/ECOLI consensus | 69.8 | 50.6 | 92.8 | 87.3 | 71.7 | 51.0 | 92.7 | 0.44 | 85.9 |

| *RULE BASED (GT_EXPERT) | 77.3 | 65.5 | 74.5 | 73.1 | 70.0 | 31.5 | 92.3 | 0.31 | 86.4 | |

| Leadscope Inc | *Statistical-based QSAR (rebuild II) | 69.8 | 59.6 | 83.6 | 80.3 | 71.6 | 36.4 | 92.9 | 0.36 | 87.3 |

| *Rule-based (alerts; Bacterial mutagenicity v2) | 69.4 | 55.5 | 87.1 | 82.8 | 71.3 | 40.5 | 92.5 | 0.38 | 88.4 | |

| Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS | *CAESAR (training set based on Katius et al.) | 78.0 | 67.6 | 67.0 | 67.1 | 67.3 | 25.4 | 92.5 | 0.25 | 100.0 |

| *SARPY (training set based on Katius et al.) | 72.5 | 63.3 | 60.7 | 61.1 | 62.0 | 21.1 | 90.9 | 0.17 | 100.0 | |

| *KNN batch (training set based on Hansen et al.+ Phase I & II) | 42.7 | 31.7 | 93.0 | 84.3 | 62.4 | 43.3 | 89.1 | 0.28 | 92.9 | |

| LMC-Bourgas University | TIMES AMES mutagenicity v.14.14. (In domain TIMES model) | 85.7 | 47.0 | 87.3 | 81.0 | 67.2 | 40.3 | 90.0 | 0.32 | 9.7 |

| *TIMES AMES mutagenicity v.14.14. (Including out of domain) | 64.0 | 50.0 | 78.2 | 74.2 | 64.1 | 27.6 | 90.4 | 0.23 | 99.9 | |

| Istituto Superiore di Sanita | *ToxTree 2.6.6 | 73.3 | 60.9 | 69.2 | 68.0 | 65.1 | 24.7 | 91.4 | 0.22 | 100.0 |

| Swedish Toxicology Science Research Center | *SwetoxAZAMES v2 | 77.1 | 61.0 | 87.7 | 83.9 | 74.4 | 44.5 | 93.3 | 0.43 | 91.2 |

| Fujitsu Kyushu Systems Limited | *ADMEWORKS AMES ver7.1.0 |

60.6 | 46.3 | 87.8 | 82.2 | 67.1 | 37.1 | 91.3 | 0.31 | 74.5 |

| IdeaConsult Ltd. | *Ambit consensus model | 70.3 | 60.1 | 80.0 | 77.1 | 70.1 | 33.6 | 92.3 | 0.32 | 99.1 |

| Molecular Networks GmbH and Altamira LLC | *ChemTunes•ToxGPS Ames (enhanced) | 78.6 | 65.2 | 82.7 | 80.3 | 74.0 | 38.2 | 93.6 | 0.39 | 95.4 |

| Simulations Plus, Inc | *MUT_Risk-8.5 | 76.0 | 61.5 | 72.0 | 70.5 | 66.8 | 27.1 | 91.7 | 0.25 | 96.4 |

Further improvement of prediction power

According to the survey of Ames test data from NTP, estimated inter-laboratory reproducibility of Ames tests is around 85% (34,35), equivalent to the predictive power of the better QSAR tools in this project. Further improvement in the predictive power of QSAR tools requires not only accumulation of additional Ames test data, but also enhanced quality, including re-evaluation of older Ames test results. As with other in vitro toxicological studies, the Ames test results are influenced by the methodologies employed and materials used (2). Such information is important for interpreting Ames test results in different laboratories and for building QSAR models. Another important factor is inconsistency in classification criteria, which leads to discrepancies among laboratories and to false-positives or false-negatives by QSAR prediction. According to the 1983 OECDTG471 guidelines (revised in 1997) (21) ‘There are several criteria for determining a positive result, such as a concentration-related increase over the range tested and/or a reproducible increase at one or more concentrations in the number of revertant colonies per plate in at least one strain with or without metabolic activation. Biological relevance of the results should be considered first. Statistical methods may be used as an aid in evaluating the test results. However, statistical significance should not be the only determining factor for a positive response.’ However, the 2-fold rule for determining a positive result in the Ames test has been generally applied to the ANEI-HOU and other test guidelines (36–38). A chemical can be classified as mutagenic if it induces a 2-fold or greater increase in revertant colonies compared to the negative control for at least one Ames strain in the presence or absence of rodent S9. The use of the 2-fold rule in Ames tests is widely accepted by regulatory agencies for registration or acceptance of chemicals despite criticism (39). In applying the 2-fold rule, biological relevance, statistical significance and reproducibility are sometimes ignored. In some cases, QSAR tools can accurately predict Ames mutagenicity based on the molecular mechanism, but the experimentally observed mutagenic response may be weak.

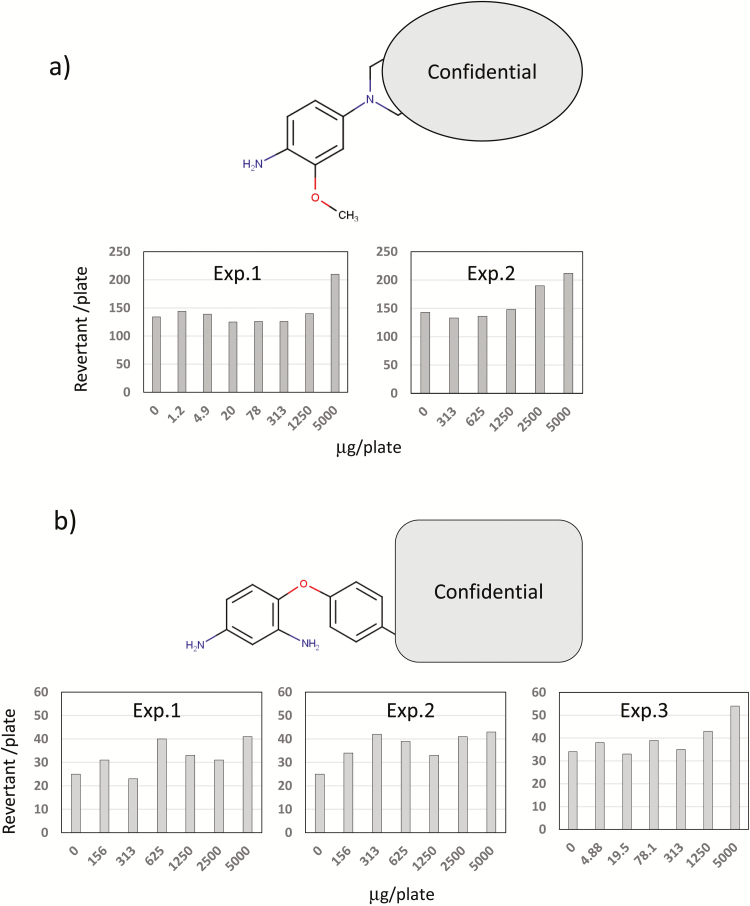

Figure 2a and b shows two aromatic amines predicted to be positive by most QSAR tools in this study but that are actually negative (Class C) in the Ames test. While listed as negative, chemical (i) weakly induced TA100 colonies and chemical (ii) weakly induced TA98 colonies, both in the presence of S9. Despite weak responses, the results were reproducible across two or three experiments, so the response could be biologically meaningful. Many QSAR tools have incorporated a structural alert for aromatic amines. The methoxy group at the ortho position and the amino group at the meta position are known to enhance the mutagenicity of aromatic amines (40). Therefore, QSAR results can support Ames mutagenicity. According to the reproducible positive response on the Ames test and the structural alerts suggested by QSAR, the two chemicals could be judged as positive. The inclusion of QSAR prediction can both support the Ames test results and provide impetus for re-evaluation. In turn, integrating more detailed Ames results will increase the predictive power of QSAR tools, leading to more accurate evaluation based on biological relevance and molecular mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Two aromatic amines predicted as Ames-positive by almost all QSAR tools, but negative in the actual Ames test (class C). Two Ames test results for chemical (a) using strain TA100 in the presence of S9, and three Ames test results for chemical (b) using strain TA98 in the presence of S9 are shown.

Poor quality Ames test data significantly decreases the predictive power of QSAR tools. Many Ames tests available in the public domain were conducted more than 30 years ago, and most QSAR vendors have used these datasets to develop their QSAR models. The Ames tests conducted in the 1980s were frequently not in compliance with the current OECD guidelines under GLP. For instance, Ames tests performed with excess cytotoxicity, high concentration (>5 mg/plate) and (or) non-standard Ames strains are more likely to be positive. These positive results should not be accepted by regulatory agencies because of doubtful biological relevance and data reliability.

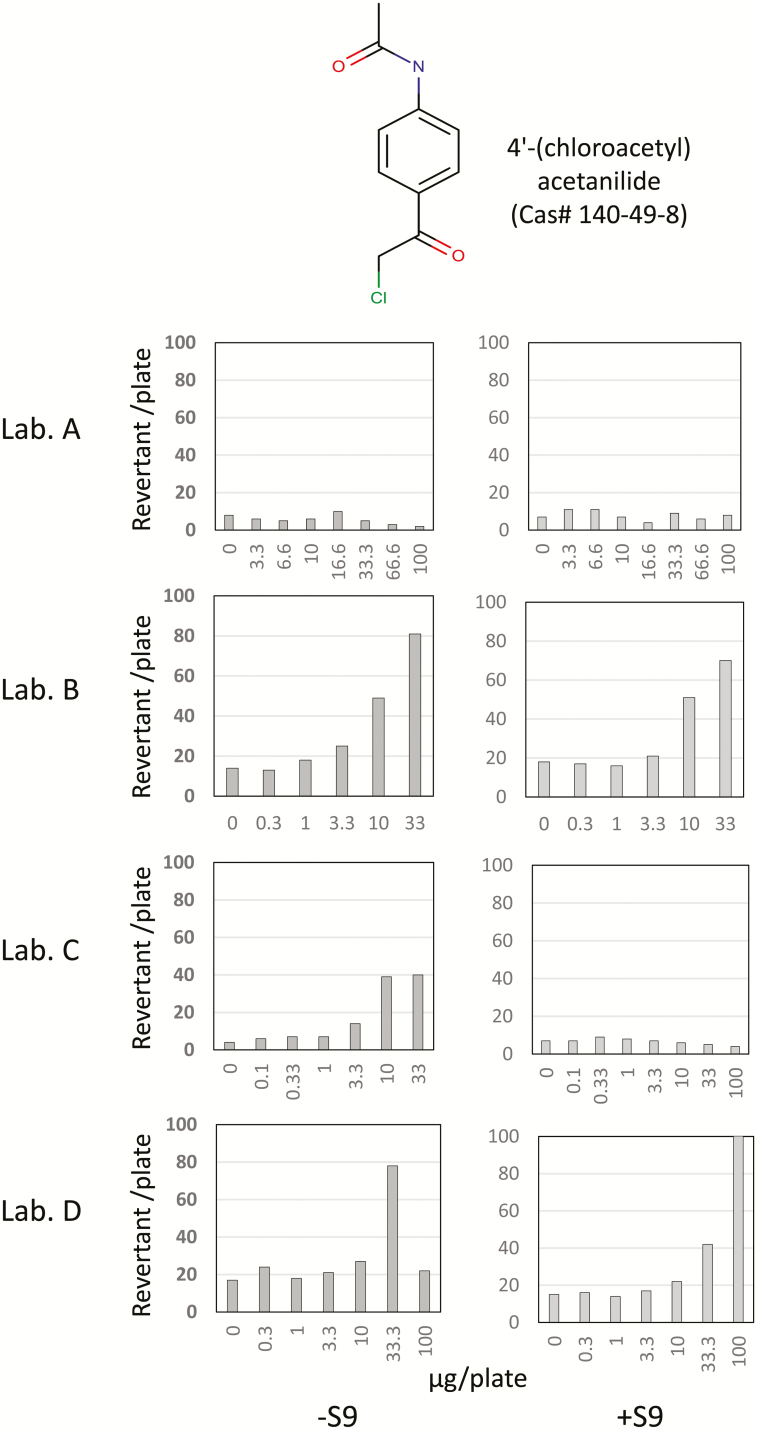

Some chemicals in the NTP list have been examined by several laboratories for Ames mutagenicity to evaluate inter-laboratory reproducibility and to provide confirmation of test results. For instance, 4′-(chloroacetyl) acetanilide was examined for Ames mutagenicity by four laboratories in an NTP validation program (Figure 3) (41). Inconsistent positive responses were observed using strain TA1537 both in the absence and presence of rat S9, no laboratory reported mutagenic responses using TA100, TA1535 or E. coli in either the absence or presence of rat S9. In spite of these equivocal results, the chemical was labelled as a mutagen in the NTP dataset, reflecting the generally conservative bias of regulatory authorities. Derek Nexus and CASE Ultra (statistical-based) predicted 4′-(chloroacetyl) acetanilide to be inactive and negative, respectively, due to the absence of a structural alert for Ames mutagenicity. Alternatively, CASE Ultra (rule-based) judged it as known-positive as NTP data was used as part of the training dataset. There is no other Ames test result for this chemical, so we cannot judge it conclusively as a non-Ames mutagen based solely on QSAR prediction. However, the positive judgement in the NTP database is doubtful, and thus causes a false negative prediction by the QSAR tools. Incorrect experimental data is not only useless for QSAR prediction, but adds noise and hinders development and improvement of QSAR models. Doubtful Ames test results should be deleted from the databases used for building QSAR models and reconsidered or re-examined for improved safety and management practices by regulatory authorities.

Figure 3.

Ames test results for 4′-(chloroacetyl) acetanilide, which was examined by four laboratories as part of an NTP validation program using the TA1537 strain with or without rat S9.

It is also known that some chemicals used in the Ames tests (e.g. vehicles for test compounds) can cause artificially positive results by generating by-products through interaction with the test compound. For instance, acyl halides are structural alerts for Ames mutagenicity (42,43) as the carbonyl group bound to the halogen atom could potentially attack DNA directly. However, Amberg et al. demonstrated that 15 of 18 chemicals with acyl/sulfonyl halides yielding positive results in the Ames test using DMSO as a vehicle were negative using another vehicle (44). The Ames-positive results were likely due to generation of halomethyl sulfide, which presumably arises from the acylation of DMSO by acyl or sulfonyl halides (via the Pummerer rearrangement). Alternatively, acyl/sulfonyl halides are generally hydrolysed in water to non-mutagenic carbonic acid and hydrogen halides or sulfonic acid and hydrogen halides, respectively. Thus, positive Ames mutagenicity of some acyl/sulfonyl halides may be an artefact of the test system. More than 300 chemicals with acyl/sulfonyl halides were included in the challenge project, 40% of which were listed as Ames-positive (Class A or B). However, we cannot speculate on whether this positive status is true or artifactual because there was no information available on the vehicle used. The results of QSAR prediction varied among models, possible because only some QSAR vendors had incorporated the results of Amberg et al. (44).

Impurities are also potential sources of false-positive responses in any toxicological test. Supplements 3 and 4, available at Mutagenesis Online, present the list of Class A chemicals that were not accurately predicted by all or almost all QSAR tools in the study. Many Class B chemicals were also predicted incorrectly by almost all QSAR tools (although specific compounds cannot be revealed). QSAR vendors, chemists and genotoxicity experts have expressed skepticism about the Ames-positivity of some Class A and B chemicals, and we suggest that these false results are due, at least in some instances, to the presence of impurities. This may be especially the case for chemicals subject to ANEI-HOU regulations as the Ames tests are mainly conducted for new agents used in manufacturing with a high probability of worker exposure. These chemicals are tested before marketing and may contain high levels of impurities. QSAR may help to identify such compounds, thereby improving the models and reducing the number of false alarms. It could also help manufacturers by highlighting cases wherein they could improve safety by modifying their manufacturing process to reduce the levels of mutagenic impurities. Therefore, data on the purity of test chemicals and vehicles used in Ames tests are critical for proper interpretation of positive results and reduction of false negative by QSAR prediction. The DGM/NIHS will disclose this information to QSAR vendors in the near future to facilitate further improvement of QSAR tools.

Conclusion

A three-phase AMES/QSAR International Challenge Project was conducted from 2014 to 2017. Seventeen QSAR tools from 12 QSAR vendors were challenged to predict the Ames mutagenicity of 12140 new chemicals in a proprietary Ames dataset that has never been used for developing QSAR tools. All QSAR tools demonstrated improved predictive power after the study compared to the original versions, indicating that this project successfully fulfilled the principal aim of enhancing QSAR performance. Some QSAR tools demonstrated greater than 80% accuracy for predicting Ames mutagenicity, which is almost equivalent to inter-laboratory reproducibility of Ames test results. To further improve the predictive power of QSAR tools, both new Ames test data and re-evaluation of previous test data are required as some chemicals may be incorrectly classified due to non-standard laboratory practices, reactions between the test compound and vehicle, and impurities in the test sample among other factors. These equivocal data hamper predictive power, add noise and hinder development of more accurate QSAR models. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a benchmark dataset consisting only of reliable Ames test results with sufficient information to build accurate QSAR models. QSARs built on such a dataset may ultimately be good enough to make it possible to resolve ambiguities in the borderline assay data, thereby reducing the number of false alarms.

Funding

This work was supported by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (H27-Chemistry-Designation-005, H28-Food-General-001 and H30-Chemistry-Destination-005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Chemical Hazards Control Division, Industrial Safety and Health Department, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan for providing the ANEI-HOU Ames dataset and allowing us to use the data in this project.

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1. Serafimova R., Gantik M. and Worth A (2010)Review of QSAR models and software tools for predicting genotoxicity and carcinogenicity. JRC Scientific and Technical Reports. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mortelmans K. and Zeiger E (2000)The Ames Salmonella/microsome mutagenicity assay. Mutat. Res., 455, 29–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller A. and Miller E. C (1977)Ultimate chemical carcinogen as reactive mutagenic electorophiles. In Hiatt H. H., Watson J. D. and Winsten, J. A (eds.), Origin of Human Cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 605–627. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ashby J. (1988)The value and limitations of short-term genotoxicity assays and the inadequacy of current cancer bioassay chemical selection criteria. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 534, 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashby J. (1991)Determination of the genotoxic status of a chemical. Mutat. Res., 248, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ashby J. and Tennant R. W (1988)Chemical structure, Salmonella mutagenicity and extent of carcinogenicity as indicators of genotoxic carcinogenesis among 222 chemicals tested in rodents by the U.S. NCI/NTP. Mutat. Res., 204, 17–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klopman G. and Rosenkranz H. S (1984)Structural requirements for the mutagenicity of environmental nitroarenes. Mutat. Res., 126, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klopman G., Tonucci D. A., Holloway M. and Rosenkranz H. S (1984)Relationship between polarographic reduction potential and mutagenicity of nitroarenes. Mutat. Res., 126, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klopman G., Frierson M. R. and Rosenkranz H. S (1990)The structural basis of the mutagenicity of chemicals in Salmonella typhimurium: the gene-tox data base. Mutat. Res., 228, 1–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ICH-M7 (R1)(2017)ICH Harmonized Guideline. Assessment and Control of DNA Reactive (Mutagenic) Impurities in Pharmaceuticals to Limit Potential Carcinogenic Risk. Current Step 4 version dated 31 March 2017 https://www.ich.org/home.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dobo K. L., Greene N., Fred C., et al. (2012)In silico methods combined with expert knowledge rule out mutagenic potential of pharmaceutical impurities: an industry survey. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 62, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sutter A., Amberg A., Boyer S., et al. (2013)Use of in silico systems and expert knowledge for structure-based assessment of potentially mutagenic impurities. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 67, 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greene N., Dobo K. L., Kenyon M. O., et al. (2015)A practical application of two in silico systems for identification of potentially mutagenic impurities. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 72, 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barber C., Amberg A., Custer L., et al. (2015)Establishing best practise in the application of expert review of mutagenicity under ICH M7. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 73, 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayashi M., Kamata E., Hirose A., Takahashi M., Morita T. and Ema M (2005)In silico assessment of chemical mutagenesis in comparison with results of Salmonella microsome assay on 909 chemicals. Mutat. Res., 588, 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hansen K., Mika S., Schroeter T., Sutter A., ter Laak A., Steger-Hartmann T., Heinrich N. and Müller K. R (2009)Benchmark data set for in silico prediction of Ames mutagenicity. J. Chem. Inf. Model., 49, 2077–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hillebrecht A., Muster W., Brigo A., Kansy M., Weiser T. and Singer T (2011)Comparative evaluation of in silico systems for Ames test mutagenicity prediction: scope and limitations. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 24, 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Snyder R. D. (2009)An update on the genotoxicity and carcinogenicity of marketed pharmaceuticals with reference to in silico predictivity. Environ. Mol. Mutagen, 50, 435–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ford K. A., Ryslik G., Chan B. K., Lewin-Koh S. C., Almeida D., Stokes M. and Gomez S. R (2017)Comparative evaluation of 11 in silico models for the prediction of small molecule mutagenicity: role of steric hindrance and electron-withdrawing groups. Toxicol. Mech. Methods, 27, 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutagenicity Test in under the Industrial Safety and Health Act(1991)Test Guideline and GLP (in Japanese). Japan Industrial Safety & Health Association (JISHA), Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD(1997)Guideline for Testing of Chemicals. Test Guideline No. 471: Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test. OECD, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matthews B. W. (1975)Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 405, 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsushima T. (1990)Genotoxicity of new Japanese chemicals. Mutation and environment, part E. In Mendelsohn M. L. and Albertini, R. J (eds.), Environmental Genotoxicity, Risk and Modulation. Wiley-Liss Inc, Hoboken, NJ, pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishidate M., Nohmi T. and Matsui M (1991)Data Book of Ames Mutagenicity Tests (in Japanese). Life-Science Information Center (LIC), Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeiger E. (1997)Genotoxicity database. In Gold L. S. and Zeiger, E (eds.), Handbook of Carcinogenic Potency and Genotoxicity Databases. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 687–729. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kier L. D., Brusick D. J., Auletta A. E., et al. (1986)The Salmonella typhimurium/mammalian microsomal assay. A report of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Gene-Tox Program. Mutat. Res., 168, 69–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeiger E. and Margolin B. H (2000)The proportions of mutagens among chemicals in commerce. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 32, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zeiger E. and Stokes W. S (1998)Validating new toxicology tests for regulatory acceptance. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 27, 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirkland D., Aardema M., Henderson L. and Müller L (2005)Evaluation of the ability of a battery of three in vitro genotoxicity tests to discriminate rodent carcinogens and non-carcinogens I. Sensitivity, specificity and relative predictivity. Mutat. Res., 584, 1–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fetterman B. A., Kim B. S., Margolin B. H., Schildcrout J. S., Smith M. G., Wagner S. M. and Zeiger E (1997)Predicting rodent carcinogenicity from mutagenic potency measured in the Ames Salmonella assay. Environ. Mol. Mutagen, 29, 312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Galloway S. M., Vijayaraj Reddy M., McGettigan K., Gealy R. and Bercu J (2013)Potentially mutagenic impurities: analysis of structural classes and carcinogenic potencies of chemical intermediates in pharmaceutical syntheses supports alternative methods to the default TTC for calculating safe levels of impurities. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 66, 326–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bercu J. P., Galloway S. M., Parris P., et al. (2018)Potential impurities in drug substances: compound-specific toxicology limits for 20 synthetic reagents and by-products, and a class-specific toxicology limit for alkyl bromides. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 94, 172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cariello N. F., Wilson J. D., Britt B. H., Wedd D. J., Burlinson B. and Gombar V (2002)Comparison of the computer programs DEREK and TOPKAT to predict bacterial mutagenicity. Deductive estimate of risk from existing knowledge. toxicity prediction by komputer assisted technology. Mutagenesis, 17, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kamber M., Flückiger-Isler S., Engelhardt G., Jaeckh R. and Zeiger E (2009)Comparison of the Ames II and traditional Ames test responses with respect to mutagenicity, strain specificities, need for metabolism and correlation with rodent carcinogenicity. Mutagenesis, 24, 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Piegorsch W. W. and Zeiger E (1991)Measuring intra-assay agreement for the Ames Salmonella assay. In Hothorn, L (ed.), Lecture Notes inMedical Informatics, Vol. 43 Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chu K. C., Patel K. M., Lin A. H., Tarone R. E., Linhart M. S. and Dunkel V. C (1981)Evaluating statistical analyses and reproducibility of microbial mutagenicity assays. Mutat. Res., 85, 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grafe A., Mattern I. E. and Green M (1981)A European collaborative study of the Ames assay. I. Results and general interpretation. Mutat. Res., 85, 391–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Red Book II(1993)Toxicological Principles for the Safety Assessment of Direct Food Additives and Color Additives Used in Food Redbook II Draft Guidance. U.S. Food & Drug; https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/IngredientsAdditivesGRASPackaging/ucm078717.htm [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cariello N. F. and Piegorsch W. W (1996)The Ames test: the two-fold rule revisited. Mutat. Res., 369, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ahlberg E., Amberg A., Beilke L. D., et al. (2016)Extending (Q)SARs to incorporate proprietary knowledge for regulatory purposes: a case study using aromatic amine mutagenicity. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 77, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dunkel V. C., Zeiger E., Brusick D., McCoy E., McGregor D., Mortelmans K., Rosenkranz H. S. and Simmon V. F (1985)Reproducibility of microbial mutagenicity assays: II. Testing of carcinogens and noncarcinogens in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Environ. Mutagen., 7 (Suppl 5), 1–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benigni R. and Bossa C (2011)Mechanisms of chemical carcinogenicity and mutagenicity: a review with implications for predictive toxicology. Chem. Rev., 111, 2507–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Benigni R. and Bossa C (2008)Structure alerts for carcinogenicity, and the Salmonella assay system: a novel insight through the chemical relational databases technology. Mutat. Res., 659, 248–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amberg A., Harvey J., Czich A., Spirkl H. P., Robinson S., White A. and Elder D. P (2015)Do carboxylic/sulfonic acid halides really present a mutagenic and carcinogenic risk as impurities in final drug products?Org. Process Res. Dev., 19, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.