Abstract

As social media use becomes increasingly widespread among adolescents, research in this area has accumulated rapidly. Researchers have shown a growing interest in the impact of social media on adolescents’ peer experiences, including the ways that the social media context shapes a variety of peer relations constructs. This paper represents Part 2 of a two-part theoretical review. In this review, we offer a new model for understanding the transformative role of social media in adolescents’ peer experiences, with the goal of stimulating future empirical work that is grounded in theory. The transformation framework suggests that the features of the social media context transform adolescents’ peer experiences by changing their frequency or immediacy, amplifying demands, altering their qualitative nature, and/or offering new opportunities for compensatory or novel behaviors. In the current paper, we consider the ways that social media may transform peer relations constructs that often occur at the group level. Our review focuses on three key constructs: peer victimization, peer status, and peer influence. We selectively review and highlight existing evidence for the transformation of these domains through social media. In addition, we discuss methodological considerations and key conceptual principles for future work. The current framework offers a new theoretical perspective through which peer relations researchers may consider adolescent social media use.

Keywords: Adolescents, Social media, Review, Peer influence, Peer status, Cyber victimization

Introduction

Recent years have seen a significant rise in research examining adolescent social media use. As these digital tools become nearly ubiquitous among adolescents (Lenhart 2015a), individuals—from investigators to the general public—have shown increasing interest in the impact of social media on adolescent peer relationships. For over 50 years, studies of peer relationships have identified the far-reaching influence of adolescents’ offline peer experiences on a variety of critical psychological, educational, behavioral, and physical outcomes (Almquist 2009; Almquist and Östberg 2013; Menting et al. 2016; Modin et al. 2011). Peer relations researchers have examined numerous peer processes, relationship types, behaviors, and reputations with implications for adolescents’ development and wellbeing (Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein 2014; Furman and Rose 2015; Prinstein and Giletta 2016; Rubin et al. 2015). However, as social media becomes a central feature of adolescents’ lives, it is essential to better understand the ways that these peer experiences are shaped by the social media environment. Despite tremendous growth in studies of social media during the past few years, research on adolescent peer relations has lacked an integrative, theoretical framework to organize and stimulate future research.

In the first installment of this two-part theoretical review (Part 1), we outlined a transformation framework for understanding the mechanisms by which social media may impact adolescent peer experiences, and we examined these potential mechanisms within the domain of adolescents’ dyadic friendship processes. However, it is likely that, beyond dyadic interactions, social media has unique implications for adolescent’s experiences of group-based peer processes. Thus, in the current paper (Part 2), we expand on our prior work by applying the transformation framework to three broad peer relations constructs with critical implications for adolescent adjustment: peer victimization; peer status, acceptance, and rejection; and peer influence (Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein 2014; Furman and Rose 2015; Prinstein and Giletta 2016; Rubin et al. 2015). Although these processes and behaviors may occur within dyadic relationships, they are especially relevant to understanding adolescents’ experiences within the larger peer network. In addition, these group processes may be uniquely affected by the features of the social media environment.

It should be noted that the current paper is not meant to serve as a comprehensive review of the literature on adolescent social media use and peer relations. For example, it does not offer detailed discussions of the growing literatures on online dating applications, online gaming, sexting, or specific social media sites. Rather, this paper serves to present an organizing framework to synthesize prior findings related to peer victimization, status, and influence; and to inform future research in the field of social media use and peer relations. Note that in the current paper, we define social media in the broadest possible sense, as any media used for social interaction, including digital applications or tools where users may share content and communicate with others (Moreno and Kota 2013). This includes social networking apps and Web sites (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram), as well as platforms allowing for messaging and/ or photograph sharing.

Overview of the Transformation Framework

Drawing on recent conceptualizations of social media as a unique interpersonal context that shapes individuals’ thoughts, behaviors, and relationships (boyd 2010;1 McFarland and Ployhart 2015; Peter and Valkenburg 2013; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel 2011), we developed the transformation framework as a means of understanding how social media impacts adolescent peer relations (see Part 1 of this series). The transformation framework represents an effort to synthesize prior work across disciplines, including theories of computer-mediated communication (CMC), media effects, and organizational and developmental psychology, highlighting work that is most relevant for understanding social media’s role in adolescent peer relationships. Furthermore, it offers a theory-driven, organizing framework to stimulate future adolescent peer relations research. In particular, it builds on McFarland and Ployhart’s (2015) contextual framework of social media, which argues that “ambient stimuli” of social media comprise a discrete context that shapes behavior within organizational settings. We extend this framework by integrating prior models of adolescent social media use, and by identifying features of the social media context with particular implications for adolescents’ peer experiences. While prior work has often relied on a “mirroring” framework of social media, or the idea that social media merely reflects the same peer interactional processes that occur offline, our transformation framework proposes that social media fundamentally transforms adolescent peer experiences. We argue that this occurs across a range of both dyadic and group-based domains, and we identify five conceptual categories of transformation. We believe this represents a critical effort for advancing the field of adolescent peer relations, which aims to better understand a generation where social media use has become the norm. Indeed, a recent nationally representative survey suggests that 89% of teenagers belong to a social networking site, 71% belong to more than one, and 88% have access to a cell phone (Lenhart 2015a).

The transformation framework integrates prior cross-disciplinary work (e.g., boyd 2010; McFarland and Ployhart 2015; Peter and Valkenburg 2013; Walther 2011) to highlight features of social media that differentiate it from traditional, offline social contexts. In particular, this framework outlines seven features of social media that are critical to understanding adolescents’ online peer experiences: asynchronicity, permanence, publicness, availability, cue absence, quantifiability, and visualness. These features are discussed in detail in Part 1, and a brief description of each can be found in Table 1 of this paper. Notably, we suggest that these features should be considered on a continuum for any given social media platform (e.g., Facebook) or functionality (e.g., posting a public photograph, sending a private message), with different social media tools representing higher or lower levels of each feature. Overall, however, we suggest that social media tools show higher levels of each feature than do adolescents’ traditional, in-person peer contexts.

Table 1.

Examples of social media features transforming adolescents’ traditional group-level peer experiences

| Social media feature | Definition | Peer victimization | Peer status | Peer influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asynchronicity | Time lapse between aspects of communication | • Perpetrators cannot see immediate effects on victims • More time to plan specific victimization acts |

• Can carefully craft content to increase appearance of status | • Can optimize appearance of conformity |

| Permanence | Permanent accessibility of content shared via social media | • Possibility of saving or sharing damaging content; victimization can be repeated by perpetrator and others • Provides permanent “evidence” of victimization |

• Allows for peer surveillance and monitoring • Evidence of rejection from social events more obvious |

• Can return to same messages repeatedly, allowing for repeated influence over time |

| Publicness | Accessibility of information to large audiences | • Victimization more visible to others; theoretically “infinite” audience for victimization • May draw in bystanders • May create “drama” with public conflict |

• Opportunity to amplify status beyond school boundaries • Access to information about and potential comparison with wide network of peers • Encourages efforts to “curate” one’s image in the pursuit of status |

• Access to broader peer network creates exposure to new behaviors • Opportunities for larger contagion effects • Can view other peers’ support of posted behaviors |

| Availability | Ease with which content can be shared, regardless of physical location | • Victims cannot “escape” perpetrators, as victimization can take place anywhere | • Pressure of constant accessibility to maximize status and social opportunities • Possibility for low-status youth to find online community |

• Influential content and messages spread more quickly • Immediate reinforcement of content posted |

| Cue Absence | Degree to which physical cues absent | • Disinhibition may create harsher victimization • Ambiguous comments may be interpreted as aggressive |

• Low-status youth may “compensate” for social difficulties in more comfortable context • Opportunities to experiment with identity • Atmosphere of selective self-presentation amplifies social comparison |

• Disinhibition creates potential for more deviant behavior • Peers’ approval of behaviors may be misinterpreted; potential for distorted peer norms |

| Quantifiability | Allowance for countable social metrics | • Perpetrators may be reinforced by likes, comments, or views • Bystanders may observe quantifiable reinforcement and replicate the victimization |

• Information about social status (likes, comments, number of friends) can be counted and compared • Increase salience and concern about status |

• Reinforcement for behaviors is directly observable in numbers of likes, comments, views, retweets, etc. |

| Visualness | Extent to which photographs and videos are emphasized | • Opportunities for different types of victimization in the form of photographs and videos | • Focus on attractiveness and displayed material goods as status measures • Motivation to post photographs of “high-status” activities • Contribute to selective self-presentation that increases upward comparisons |

• Potential for powerful, reinforced visual displays of risk behavior |

Many examples of transformed peer experiences are likely to be the result of multiple social media features. For ease of presentation, peer experiences are listed in relation to the social media feature believed to be most relevant in transforming that experience

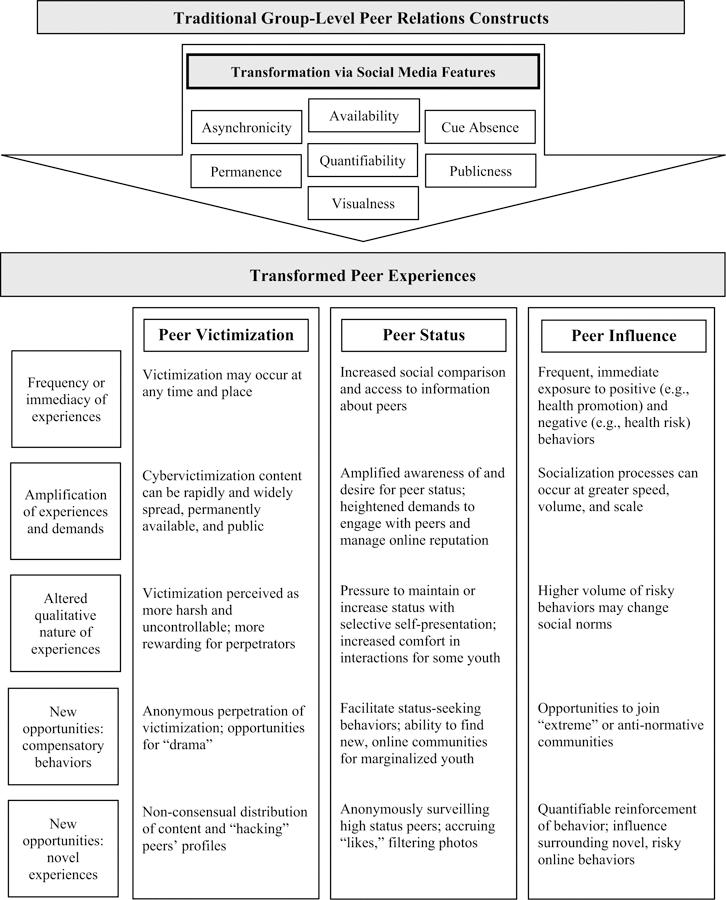

We offer five broad categories of transformation as a means of conceptualizing the numerous ways that social media transforms peer experiences. First, social media may transform these experiences by changing the frequency or immediacy of those interactions. Second, social media may amplify peer experiences and demands by increasing their intensity and scale. Third, social media may alter the qualitative nature of peer experiences, offering interactions that may be higher or lower in their levels of positive qualities or negative qualities. Fourth, social media may transform peer experiences by creating new opportunities for compensatory behaviors—i.e., behaviors that would have been less likely or more challenging offline. Finally, it may create opportunities for entirely novel behaviors, or behaviors that would have been impossible offline. In applying the transformation framework to the constructs of peer victimization, peer influence, and peer status, we structure our discussion to highlight each of these forms of transformation. Figure 1 illustrates the application of the transformation framework, and its five categories of transformation, to these three peer relations constructs.

Fig. 1.

The transformation framework with examples of transformation of three group-level peer constructs

Application of the Transformation Framework to Peer Relations Constructs

The current review applies the principles of the transformation framework to three domains of peer relations shown to have critical implications for adolescent development and well-being: peer victimization, peer status, and peer influence (Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein 2014; Furman and Rose 2015; Prinstein and Giletta 2016; Rubin et al. 2015). The social media environment may be particularly influential in shaping these group-based peer processes. In the upcoming sections, we outline how the features of social media may transform each of these domains, reviewing existing evidence and offering theory-driven hypotheses (see Table 1). In some cases, studies are available that directly compare offline and online processes. However, only a small number of these types of studies exist. Indeed, although numerous CMC studies have examined differences between online and offline communication—typically among adults and often specific to organizational settings—the literature examining adolescents’ peer experiences on social media remains surprisingly limited. Thus, where studies are not available that directly compare behaviors in the online and offline spheres, we draw on descriptive and experimental work. Although they do not directly examine the unique effects or predictors of social media experiences, over and above offline experiences, such studies offer rich descriptive data on the ways in which adolescents’ peer experiences are fundamentally different in the context of social media, illuminating the role of specific social media features (e.g., publicness and cue absence). In addition, where studies of adolescents are not available, we review work conducted with adult samples and offer theory-based speculations regarding how similar processes may unfold among adolescents. Overall, we offer a growing body of theoretical and empirical evidence to suggest that social media transforms adolescents’ peer experiences, with such evidence highlighting the critical need for future investigative efforts into these processes.

Peer Victimization

For decades, researchers have studied the nature, correlates, and outcomes of peer victimization. As adolescents’ peer interactions increasingly occur via social media, a growing interest has developed in peer victimization as it occurs in this new context. In fact, online victimization (i.e., cyber victimization, cyber aggression, or “cyberbullying”) has been one of the most heavily researched topics in the field of adolescent social media use and peer relations. Additionally, the potentially devastating effects of cyber victimization have captured the attention of the general public, such as through news stories about teen suicides (e.g., Leung and Bascaramurty 2012). However, an implicit debate has arisen about cyberbullying within the scientific literature. Specifically, some scholars (e.g., Olweus 2012) have proposed that online victimization is simply traditional bullying that occurs online—i.e., that technology provides a new context for old behaviors, and that adolescent cyberbullying can be understood by studying traditional, offline bullying. Over the course of the past decade, however, other scholars have begun to examine cyberbullying as its own, unique construct, involving behaviors, correlates, and outcomes that are distinct from those of traditional victimization. It is critical to consider the ways in which experiences of victimization may be transformed within the context of social media. Notably, in this section, we use the term cyber victimization as an umbrella term to capture the broad range of intentional acts of aggression and victimization that occur through social media.

Increased Frequency and Immediacy of Victimization

Social media may transform the experience of victimization in a number of ways, beginning with the potential for increased frequency and immediacy of victimization episodes. The availability of social media means adolescents can never fully escape the potential for victimization, perhaps leading to feelings of powerlessness (Dooley et al. 2009). Whereas most traditional bullying experiences occur during school hours, cyberbullying is more likely to occur outside of school (Smith et al. 2008). Qualitative work suggests that whereas adolescents may have once perceived the home environment as a “sanctuary” from bullying, the availability of social media means that this is no longer the case (Slonje and Smith 2008). Additionally, the ability to aggress against peers at night, outside of adult supervision is especially notable (Runions 2013).

Altered Qualitative Nature of Victimization

In addition, social media may transform victimization by creating different qualitative experiences, with cyber victimization perceived as more harsh and uncontrollable by victims and more rewarding for perpetrators. Theoretical and empirical work offer evidence that the asynchronicity and cue absence of social media may alter the qualitative nature of bullying by encouraging harsher forms of victimization. Within the CMC and media effects literature, considerable evidence has accumulated for the “online disinhibition effect” (Suler 2004)—the idea that the features of the online environment create a context in which individuals are more likely to say or do things that they would not in the “offline world.” Perpetrators may not receive immediate feedback from peers, and likely cannot observe the verbal or facial cues of victims. Thus, they may engage in more extreme or aggressive forms of victimization or acting out online—a phenomenon known as “toxic disinhibition” (Suler 2004). Indeed, prior research suggests that online disinhibition increases aggressive and threatening behavior (Lapidot-Lefler and Barak 2012), and that adolescents who experience greater cues from victims (e.g., Smith et al. 2008). “Excitation transfer” from online gaming and internet pornography (i.e., anger resulting from broader arousal) has also been proposed as a possible contributor to the drive for cyber aggression, although this possibility has not been empirically tested (Runions 2013). These processes are compounded by the fact that perpetrators often feel anonymous online, and thus may be less concerned about being discovered by parents or teachers (Ehrenreich and Underwood 2016). Furthermore, experimental work has demonstrated that online “flaming,” or extreme harassment or aggressive behavior, is more likely when participants are unable to make eye contact with conversation partners in electronic communication (Lapidot-Lefler and Barak 2012).

Whether extreme or not, the experience of being victimized by an anonymous perpetrator may additionally change victims’ qualitative experience by exacerbating feelings of hopelessness and fear, given the sense that anyone could potentially be the bully (Smith et al. 2008; Sticca and Perren 2013). The anonymous perpetrator could be a stranger on another continent, or one’s best friend sitting in the same room (White et al. 2016). Furthermore, adolescents are less likely to report cyberbullying to parents and teachers, compared to traditional bullying (Agatston et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2008). This may be due in part to perceptions that adults are ill-equipped to help with cyberbullying (Smith et al. 2008), as well as fears that parents will revoke online privileges (Agatston et al. 2007).

The asynchronicity and quantifiability of social media may also transform the qualitative experience of perpetrators by creating a different reinforcement structure, compared to traditional bullying. On the one hand, the asynchronicity of social media means that perpetrators are unable to immediately see the impact of their behavior—a notable difference between cyberbullying and traditional bullying, given that victims’ responses have been documented as a powerful reinforcement for traditional bullies (Olweus 1993). On the other hand, however, the quantifiability of social media may create a new and potent reinforcement structure for perpetrators, with the possibility of large audiences represented through likes and followers. Additionally, asynchronicity may increase the likelihood of victims’ retaliating disinhibition are more likely to victimize others online (Udris 2014). Adolescents attribute “entertainment” as a key motivator for cyberbullies, further noting that perpetrators may lack concern about their behaviors due to an absence of empathy-inducing against their bullies. Whereas traditional bullying typically involves a power differential in which the victim is less able than the bully to fight back (Olweus 1993), the asynchronicity of social media allows victims the space and time to carefully plan their response (Runions 2013).

New Opportunities: Compensatory Behaviors in Cyber Victimization

Social media may further transform victimization experiences by creating new behaviors. In some cases, these behaviors may be “compensatory”—that is, possible but unlikely in an offline context. For example, the cue absence of social media creates new opportunities to perpetrate victimization without revealing one’s identity. Indeed, some adolescents have reported spreading damaging content about a close friend anonymously (e.g., during a fight) without ever being caught; in some cases, the perpetrating “friend” even comforted the victim through the ensuing pain (White et al. 2016). A longitudinal study of US middle schoolers provides further support for the importance of social media’s permanence and cue absence in encouraging some youth to perpetrate anonymous victimization. Over a one-year period, increased engagement in anonymous cyber aggression was predicted by adolescents’ beliefs that their digital content would be impermanent, that they could remain anonymous, and that they would not be caught (Wright 2014). This may help to explain why one study found that 27% of adolescents reported they did not know the perpetrator of their cyber victimization or that this person was a “stranger” (Waasdorp and Bradshaw 2015)—a striking difference from experiences of traditional bullying, which overwhelmingly involve experiences with known peers (Olweus 1993).

Social media use may also transform adolescent peer relations by creating new opportunities for interpersonal conflict or “drama,” which is related to but distinct from cyber victimization (Marwick and boyd 2011a, 2014). Adolescents often use the term “drama” to capture a broad range of conflicts on social media. Whereas drama may have always been possible offline, social media creates new opportunities for this experience as a “compensatory” behavior—one that some adolescents may not have engaged in without the affordances of social media. Marwick and boyd (2014) studied the construct of “drama” through unstructured interviews with adolescents about peer relationships, in which teens often spontaneously discussed this concept. Based on qualitative analysis, the authors ultimately defined “drama” as “performative, interpersonal conflict that takes place in front of an active, engaged audience, often on social media” (p. 1191). One motivation adolescents described for engaging in social media “drama” is that its visible and public nature creates entertainment, attention, and heightened impact (Marwick and boyd 2014). For example, adolescents reported peers may publicly air grievances with friends or classmates to gain attention and/or support; peers who would not normally be involved in the argument then weigh in and “take sides” through social media comments, thereby “fostering drama” (Marwick and boyd 2014). Note that the performative nature of social media drama capitalizes on the publicness of the sphere (Marwick and boyd 2014). Importantly, adolescents differentiated between drama and the related but distinct concepts of cyber victimization and aggression. However, the authors noted that teens may conceptualize social media conflicts as “drama” in order to psychologically protect themselves from experiences that adults may consider to be “bullying” (Marwick and boyd 2014). Several adolescents commented that much of this drama would not be possible without social media, noting specific aspects of social media that are central to the transformation framework. For example, youth noted that the availability and publicness of social media provide unprecedented access to content about peers’ lives, as well as the ability to communicate to broad networks of peers outside of school, anywhere and anytime (Marwick and boyd 2014).

New Opportunities: Novel Experiences in Cyber Victimization

In addition to creating new opportunities for “compensatory behaviors” in the realm of cyber victimization, social media may also create opportunities for entirely novel victimization behaviors, which would not have been possible outside of social media. For example, Willard (2007) has identified unique forms of cyber victimization that include “impersonation,” in which a perpetrator may “hack” a victim’s social media account to gain access to private information or post damaging messages while impersonating the victim; and “outing and trickery,” in which a perpetrator publicly shares messages or photographs that a victim had privately sent. Social media’s cue absence and permanence allow a perpetrator to impersonate a victim and to access private information, while the availability and publicness of social media allow such content to be shared quickly with large groups of people.

Social media’s visualness, permanence, publicness, availability, and quantifiability collectively contribute to the possibility that photographs depicting embarrassing or illegal behaviors can be distributed without a victim’s consent. For example, although a full discussion of the phenomenon of “sexting” is beyond the scope of this review, the nonconsensual distribution of sexual images is one example of how social media transforms peer victimization by creating opportunities for new behaviors. Specifically, some episodes of cyber victimization involve the nonconsensual distribution of sexually suggestive or explicit images of peers. For example, adolescents may share nude images of themselves on Snapchat, believing this is “safe” because the images will “disappear”—but peers can in fact take screenshots of the images and then distribute them (Vaterlaus et al. 2016). Other cases have been documented in which an adolescent privately shares a nude photograph with a friend or romantic partner, who then widely distributes the photograph to classmates (Lorang et al. 2016). In extreme cases, youth have posted or live-streamed videos of sexual assault (e.g., Stelloh 2017), and cases have been documented in which the nonconsensual distribution of sexual images has led to felony charges or suicide (Lorang et al. 2016).

As with other forms of cyber victimization, the availability, visualness, publicness, permanence, and quantifiability of social media have also transformed adolescents’ experiences of dating aggression within romantic relationships. For example, qualitative evidence suggests that some adolescents may search or monitor their dating partners’ phones to track their communications with members of the opposite sex—behaviors that are only possible due to the availability and permanence of social media (Baker and Carreño 2016). Youth also describe using social media to publicly post aggressive, harassing, and humiliating messages about one’s current or former partner (Draucker and Martsolf 2010). In extreme cases, victimization on social media may take the form of tracking a partner’s physical location via smart phone applications, breaking a partner’s phone to prevent communication with members of the opposite sex, or logging into a partner’s profile to “defriend” people or send damaging messages (Baker and Carreño 2016; Draucker and Martsolf 2010).

Amplification of Victimization Experiences

In combination with the increased frequency and immediacy of victimization experiences, harsher nature of victimization, and opportunities for new behaviors, multiple features of social media may amplify peer victimization processes online. For example, the availability, publicness, and permanence of social media may increase the likelihood that cyber victimization content will be rapidly and widely spread. Due to these interrelated features of social media, adolescents can perpetrate cyberbullying anywhere, from any place, and then “repeat the harm over and over again with the click of a button” (Kowalski et al. 2014), allowing large audiences to view the victimization (White et al. 2016; Wigderson and Lynch 2013). Furthermore, this audience may even become an expanding (potentially infinite) set of perpetrators (Dooley et al. 2009). For example, qualitative evidence suggests that adolescents may reproduce harmful messages or images of peers and transmit them widely (e.g., Slonje and Smith 2008). Such public attacks may feel acutely harmful to adolescents, given the centrality of social status to their identity and sense of self-worth (Sticca and Perren 2013). The permanence of social media content—in combination with visualness—may further amplify the experience of victimization. Traditional bullying can create lasting harm, but the experience itself is often temporary. On many social media sites, however, content is permanently visually displayed, such that evidence of cyber victimization may be available indefinitely. Even on social media sites that allow individuals to remove unwanted content from their own profiles, content may rapidly spread and be permanently available through other channels. Further complicating these dynamics, a peer (or stranger) can digitally alter a teen’s text or photograph before distributing it, thereby creating false but permanent content that may be embarrassing and harmful (White et al. 2016).

Several studies of adolescents’ perceptions of and beliefs about cyber victimization provide further evidence for the amplification of victimization experiences. For example, a mixed methods study highlighted the intersecting role of visualness and quantifiability in exacerbating the impact of cyber victimization. Specifically, adolescents reported perceiving cyber victimization involving photographs and videos as being more severe than traditional victimization (e.g., Smith et al. 2008). Swedish adolescents also described photo/video victimization as having a stronger negative impact than traditional victimization (as well as text-based cyber victimization), noting the publicness and visualness of such episodes as being especially powerful (Slonje and Smith 2008). A study with an experimental design provides further direct evidence for role of social media’s publicness and cue absence in cyber victimization (Sticca and Perren 2013). Swiss adolescents rated the severity of hypothetical episodes of bullying, which were experimentally manipulated to compare the type (cyber vs. traditional victimization), publicness (public vs. private episode), and anonymity (anonymous vs. non-anonymous bully) of the episode. Results suggested that cyber victimization was perceived as more severe than traditional victimization; notably the specific features of publicness and anonymity impacted the perceived severity of a bullying episode more than did the medium (traditional vs. cyber; Sticca and Perren 2013).

Theoretical work also highlights the ways in which social media’s features amplify the experience of victimization. For instance, Runions (2013) has proposed a conceptual model for understanding motive and self-control in cyber aggression, noting that the specific features of social media may predict different types of victimization. For example, impulsive aggression through social media may be fueled by the perception of a “perpetual peer audience” (i.e., due to publicness and availability) which may increase thrill-seeking and risk-taking behaviors; impulsive aggression also may be exacerbated by cue absence and the possibility for misinterpreting ambiguous peer messages (Runions 2013). On the other hand, controlled and planned forms of aggression may be nurtured by the asynchronicity and permanence of social media—i.e., by allowing adolescents to engage in hostile rumination while revisiting permanent content—as well as by the anonymity and lack of cue presence involved in cyber aggression, which decreases the likelihood of negative consequences for the perpetrator (Runions 2013).

In addition to amplifying peer victimization processes more broadly, the social media context may specifically transform the processes of bystander intervention. As discussed above, a unique characteristic of cyber victimization is the large audience of peers involved, who may reinforce the behavior with quantifiable indices (e.g., “likes”). Given the specific characteristics of social media, the role of bystanders in cyber victimization is complex. On the one hand, if an episode of victimization is visible to a broad network of peers, the number who could potentially intervene is much greater than in a traditional bullying context. On the other hand, cue absence may create a sense of anonymity that decreases each peer’s likelihood to intervene. Furthermore, the high number of audience members may (paradoxically) decrease the likelihood that adolescents will assist or stand up for victims. This possibility is based on extensive research from social psychology on the (traditionally offline) bystander effect, which indicates that as the number of bystanders increases, the probability of any individual bystander’s intervening decreases (Fischer et al. 2011). Interestingly, a meta-analysis found the bystander effect to be attenuated when individuals perceived physical danger and/ or the possibility of physical support from other bystanders (Fischer et al. 2011)—neither of which are relevant in the typical social media victimization episode. These findings suggest that the bystander effect may be amplified in the social media context, reducing the likelihood that witnesses will help victims. Providing support for this idea, in a Pew Research Center survey adolescents reported that the most common response to cruel online behavior was to ignore it (Lenhart et al. 2011). Additionally, the availability, publicness, and cue absence of social media may encourage adolescents to endorse aggressive or harassing content that they might not support offline (see Bastiaensens et al. 2014), due to toxic disinhibition processes (Suler 2004). Strikingly, 67% of the Pew respondents said they had witnessed others joining in cruel online behavior and 21% reported that they had personally joined in at some point (Lenhart et al. 2011).

Discriminant Associations: Cyber Versus Traditional Victimization

Evidence has begun to accumulate that cyber victimization represents a distinct experience from traditional victimization, showing discriminant associations with predictors and outcomes. A comprehensive meta-analytic review found that traditional bullying explained only 20% of the variance in reports of cyberbullying (Kowalski et al. 2014). Furthermore, a large study of over 28,000 adolescents found that 71% of participants reported being cyberbullied by an individual who had not also bullied them in-person, and cyber victims were significantly more likely to report externalizing and internalizing symptoms, compared to teens who reported only traditional victimization (Waasdorp and Bradshaw 2015). Several other studies have found that cyber victimization experiences are associated with increased internalizing symptoms and lower academic performance, after accounting for the effects of traditional victimization (Bonanno and Hymel 2013; Fredstrom et al. 2011; Wigderson and Lynch 2013). In addition, a recent meta-analysis of 90,877 youth found that cyber victimization was uniquely associated with increased internalizing symptoms, controlling for traditional victimization (Gini et al. 2017).

Peer Status

Peer status has long been known to play a significant role in adolescents’ adjustment (Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein 2014; Prinstein and Giletta 2016). Within the peer relations field, two distinct types of peer status have been described: likeability (i.e., sociometric popularity or peer acceptance; Coie et al. 1982) and peer-perceived popularity (based on an individual’s reputation of visibility and dominance in the peer hierarchy; Parkhurst and Hopmeyer 1998). Notably, peer-perceived popularity takes on increasing importance during adolescence, when young people are particularly attuned to peer feedback and status (Harter et al. 1996). In this review, we primarily focus on peer-perceived popularity, given that the social media context may be particularly conducive to heightening adolescents’ orientation to this kind of status (Nesi and Prinstein 2018).

Amplified Peer Status Experiences and Demands

The features of social media may amplify the experience of peer status. In particular, adolescents may experience heightened awareness of their own and others’ popularity, as well as concern about their status among peers. Within the context of social media, information regarding social status is readily available. The quantifiability of social media provides, for the first time, numerical indicators of status in the form of friend lists, comments, and likes, which can be easily counted and compared (Chua and Chang 2016; Madden et al. 2013). The publicness and permanence of this environment also creates an opportunity for adolescents to view the status indicators of a wide range of their peers, with cue absence providing an invisible wall from behind which adolescents can view the activities of their high-status peers (Marwick 2012).

The very concept of popularity, and what is considered to represent “high status,” may be amplified in the social media environment, where ethnographic work suggests that a “micro-celebrity” culture pervades (Marwick 2013). The publicness and availability of social media platforms create the potential for any user to amass thousands of followers. Although the attainment of such high status is uncommon, its possibility encourages practices of “self-branding,” or attracting online attention through the use of techniques traditionally associated with consumer brands (Marwick 2013, 2015). Any teenager can in theory become a “celebrity” on social media and, in fact, some of them do. In a series of case studies of individuals who have become “Instagram famous,” Marwick (2015) highlights one seemingly average high school student with over 30,000 followers. Based on the photographs of parties and football games she posts, the author suspects that this Instagram user must be popular within her high school; the features of social media, however, allow her to expand her popularity beyond the bounds of her physical location. In addition, the emphasis on photographs on social media sites like Instagram may amplify the importance of visual representations in conferring peer status—with attractive self-presentations often accruing more attention and “likes” online (Marwick 2015). Although such depictions of status may seem effortless, together the visualness and asynchronicity of social media sites encourage the careful engineering of photographs (Kasch 2013).

Within an environment of heightened possibilities for status and rejection, demands around adolescents’ management of peer relationships also may be amplified. In qualitative studies, young people describe feeling “tethered” to social media, with significant pressure to manage social connections and keep up with relationships (Fox and Moreland 2015). Similarly, publicness and availability may exacerbate adolescents’ experiences of “fear of missing out,” defined by researchers as the experience of apprehension that one may be missing out on rewarding social activities (Przybylski et al. 2013). Indeed, one study suggests that this “fear of missing out” mediated the association between Facebook use and greater need for popularity among adolescents (Beyens et al. 2016), and that adolescents with greater fear of missing out used Facebook more intensely. Furthermore, visualness, publicness, and permanence create an environment where photographs of social events, often carefully crafted or chosen, serve as clear evidence of rejection for adolescents who were not present at these events (Underwood and Ehrenreich 2017). As social media allows adolescents greater access to the activities and relationships of their peers, it is likely to increase the sense that they are missing out on social opportunities, conversations, and events. Indeed, in a recent national survey, 53% of adolescent social media users reported having seen posts on social media about events to which they were not invited (Lenhart 2015b). Some adolescents thus engage in “uncertainty reduction” strategies online, using social media to gather information about peers’ personalities, opinions, and behaviors (Courtois et al. 2012). In addition, this may heighten pressure to remain “in the loop” via social media, leading adolescents to engage in increased peer surveillance and monitoring behaviors, so as not to miss out on important social information, events, or gossip. Emerging research with adults on the phenomenon of “phantom phone signals” suggests that the pressure to remain constantly accessible via social media may even cause some individuals to experience the false sensation of receiving a cell phone notification (Tanis et al. 2015). Interestingly, results suggest that adults reporting higher need for popularity were more likely to experience phantom phone signals (Tanis et al. 2015).

The visualness of social media may also amplify adolescents’ social comparison processes by increasing the focus on physical appearance, particularly among girls. While historically, peer popularity has always been associated with physical attractiveness (LaFontana and Cillessen 2002), social media platforms that reward attractive photographs in the form of quantifiable status indicators may intensify this link between appearance and peer status. Adolescents may engage in greater appearance-based upward comparisons with popular peers, and feel pressure to match the appearance standards of these peers in order to maintain their own status. Qualitative work suggests that adolescent girls are highly aware of their peers’ appearances in photographs, and that some may use quantifiable metrics (e.g., likes, complimentary comments) as measures of comparison to their own attractiveness (Chua and Chang 2016). Indeed, numerous studies suggest a positive association between social media activities and body image concerns, and the initial evidence highlights appearance-based comparisons as a mechanism of this association (for a review, see Holland and Tiggemann 2016). Preliminary evidence suggests that upward appearance comparisons made via social media may have a unique impact on negative outcomes, including appearance dissatisfaction and negative mood, compared to such comparisons made in-person (Fardouly et al. 2017). In line with the transformative features of social media, this discrepancy may be due to the heightened salience of appearance comparisons in the presence of quantifiable likes and comments on photographs.

Social media may even intensify efforts to maintain or increase peer status by impacting adolescents’ offline behavior. Specifically, while the publicness, availability, and permanence of social media may lead individuals to carefully manage their online reputations (known as the online “chilling effect”; Marwick and boyd 2011b), these features may also transform adolescents’ offline behaviors by intensifying expectations and demands. In a study of adults, Marder et al. (2016) found qualitative and experimental evidence of an “extended chilling effect,” whereby, when the potential audience of social media is made salient, individuals change their offline behavior to avoid negative self-presentations online. Another recent study found that college women reported frequently experiencing offline concerns about how their bodies would appear to a social media audience (Choukas-Bradley et al. 2017). Given the emphasis on peer approval and reputation during adolescence, it seems likely that adolescents also shape their offline behaviors to maximize the appearance of status online.

Altered Qualitative Nature of Peer Status

The features of social media may change the qualitative nature of the experience of peer status, specifically creating a “high stakes” environment in which online interactions may be more careful or calculated. Preliminary evidence suggests that social media creates a context in which social identities and status indicators are carefully managed and constructed. Scholars have long considered the role of the “imagined audience” in adolescence (Elkind 1967), or the belief that peers are observing and scrutinizing one’s behavior. Within the literature on social media, researchers have suggested that social media allows for the “imagined audience come-to-life” (boyd 2014; Underwood and Ehrenreich 2017), as the publicness of many platforms allows for an actual audience of adolescents’ peers to observe their behaviors and interactions. Furthermore, the asynchronicity of many platforms creates an opportunity for careful, deliberate construction of one’s posts. Indeed, qualitative work suggests that teens often take steps to “curate” their social media content, with the majority of adolescents reporting that they have deleted and/or edited posts on their profiles made by themselves or others (Madden et al. 2013). A qualitative study of adolescents receiving mental health services further highlights young people’s desire to present a “safe and socially acceptable” version of themselves online, so as to manage their reputations by ensuring positive feedback and avoiding negative feedback from peers (Singleton et al. 2016). Similarly, in a national survey, 40% of adolescent social media users reported feeling pressure to post only content that “makes them look good to others” (Lenhart 2015b). Qualitative work suggests that adolescents are well aware of the quantifiable, public markers of peer status that are available on social media, such as numbers of followers, comments, likes, and even the time it takes to accrue those markers (Chua and Chang 2016; Madden et al. 2013). According to one survey, as many as 39% of adolescent social media users report feeling pressure to post content that will “be popular and get lots of comments and likes” (Lenhart 2015b). Importantly, within this environment of selective self-presentation, online social comparison processes may increase in frequency and intensity (Manago et al. 2008) and can have unique effects, over and above general tendencies toward social comparison, on rumination and depressive symptoms (Feinstein et al. 2013).

Whereas certain photographs and posts can increase an individual’s perceived attractiveness or status, deviations from socially acceptable online behavior can have negative repercussions for an adolescent’s status. For example, research suggests that adolescents risk negative feedback online if they friend, message, or comment on the online content of peers whom they do not know well (Koutamanis et al. 2015). With such negative feedback publicly and permanently available, the reputational repercussions may be significant, increasing adolescents’ desire to carefully manage their online reputations. Furthermore, as social media norms continue to develop, it may be difficult for some adolescents to navigate which online behaviors will be beneficial versus detrimental to their peer status. The example of sexualized online self-presentations represents this difficulty well and highlights important role of social media’s visualness. In one study, high school students who engaged in online sexual self-presentations (e.g., photographs of themselves in a sexual pose) reported higher perceived peer norms for these behaviors and stronger need for popularity, suggesting that they viewed these behaviors as a means to maintain or increase status. However, when participants evaluated mock social media pages, they rated individuals of the same sex more negatively (i.e., less cool, less popular)—but peers of the opposite sex more positively—when they believed those individuals had posted sexualized self-images (Baumgartner et al. 2015). Other studies suggest that individuals who post sexualized images receive more negative feedback from peers in general (Koutamanis et al. 2015). Yet qualitative work with college students highlights the balance that young people—and women in particular—must strike between posting sexual images that are viewed as desirable versus being labeled promiscuous (Manago et al. 2008). The emphasis on public and permanent visual displays may thus complicate the experience of reputation management online, particularly as adolescents begin to navigate the status implications of their sexual identities.

New Opportunities: Compensatory Status Behaviors

The features of social media may facilitate adolescents’ engagement in status-seeking behaviors. For example, as previously discussed, qualitative work has identified the construct of “drama” among adolescents (Marwick and boyd 2011a), or the performative practice of conflict and gossip that often plays out within the social media context. Participants reported that “drama” online increases individuals’ visibility and status in the larger peer group, attracting a participatory audience that would have been unlikely offline. Similarly, one longitudinal study found that engagement in cyber victimization, but not traditional victimization, resulted in increases in adolescents’ peer status over time—which was especially notable given the overall stability of popularity (Wegge et al. 2016). This suggests the unique role that social media environments may play in contributing to status—and the possibility that adolescents may engage in cyber victimization as a means of increasing their popularity. In addition to participating in drama and victimization online, adolescents may use the publicness and visualness of social media to enhance popularity through showcasing connections with high-status peers, or highlighting status-related activities such as parties (Marwick and boyd 2011b). While these behaviors may have been possible offline, social media may make them especially easy or enticing.

New Opportunities: Novel Status Behaviors

Social media also may create new opportunities for status-related behaviors that may have been impossible outside of this context. The publicness and availability of social media provide adolescents with unprecedented access to information about popular peers, perhaps heightening “upward” social comparison processes, particularly among low-status adolescents (Nesi and Prinstein 2015). Scholars have identified new online “surveillance” behaviors (Manago et al. 2008), such as “Facebook stalking,” or “cyberstalking”—in which adolescent social media users (often of lower status) systematically gather digital information about their peers (often of higher status; Marwick 2012). These behaviors may serve to maintain and reinforce social status hierarchies (Marwick 2012). Among adults, research suggests that those who perceive that they are more anonymous in their social media interactions (i.e., through cue absence) are more likely to engage in surveillance behaviors (Jung et al. 2012), and that such behaviors may increase feelings of envy (Tandoc et al. 2015).

In addition, evidence suggests that adolescents encounter new opportunities to engage in behaviors that will increase their appearance of status online. For example, research suggests that adolescents may attempt to maximize the number of “likes” and comments received on their photographs by posting at times of day when peers are more likely to be online (Nesi and Prinstein 2018), taking down or untagging photographs that do not receive enough likes or comments (Dhir et al. 2016; Nesi and Prinstein 2018), and filtering photographs in order to appear more attractive (McLean et al. 2015; Underwood and Faris 2015). The publicness and availability of social media also allow adolescents to add high numbers of “friends” to their profiles, even if they do not know them well, in order to increase the size of their friends lists (Zywica and Danowski 2008). Offering evidence for the unique role of these new behaviors in contributing to adolescent adjustment, one study found that, over and above the effects of adolescents’ actual, “offline” peer status, online status-seeking behaviors were longitudinally associated with adolescents’ increased substance use and sexual risk behavior (Nesi and Prinstein 2018).

Social Compensation Effects: Qualitative Communication Differences and Opportunities for Compensatory Behaviors for Rejected Youth

Within the media and communications fields, two major hypotheses have emerged to address how online communication may interact with offline peer status, acceptance, and rejection (Valkenburg and Peter 2007). The social enhancement hypothesis (i.e., “rich-get-richer” hypothesis) posits that extraverted and popular adolescents are more likely to benefit from online communication, as it serves to enhance their popularity and social connections (Kraut et al. 2003). The social compensation hypothesis, on the other hand, suggests that individuals with poorer offline social resources—such as those who are socially anxious, lonely, or unpopular—benefit more from Internet communication because they gain greater social support and connection online (Ellison et al. 2007; McKenna and Bargh 2000). Both of these hypotheses have garnered some evidence in the literature (Valkenburg and Peter 2007). Importantly, however, both support the primary proposition of the transformation framework—that social media changes adolescents’ peer experiences.

Many of the studies discussed above support the social enhancement hypothesis, providing evidence for the idea that social media—and in particular the publicness, availability, and quantifiability of this context—may increase opportunities for popular adolescents to connect with peers and amplify their high social status. However, the studies discussed below fall in line with the social compensation hypothesis, suggesting that social media features create compensatory opportunities for low status or rejected youth to communicate more anonymously and safely. In particular, these studies suggest that the cue absence and asynchronicity of social media platforms may change the qualitative nature of online experiences, making them more “safe” or comfortable. Adolescents with interpersonal difficulties report that social media allows for greater levels of controllability over what, when, and how they communicate, and many find that this allows for greater reciprocity or responsiveness from their communication partners (Peter and Valkenburg 2006; Schouten et al. 2007; Young and Lo 2012). As such, Valkenburg and Peter (2009) introduced the “Internet-enhanced self-disclosure hypothesis” to describe the phenomenon by which the cue absence of the online environment leads adolescents to engage in higher levels of self-disclosure when using social media. Indeed, adolescents with higher levels of social anxiety report finding it easier to communicate about secrets and feelings online (i.e., using Instant messaging tools) compared to in-person (Valkenburg and Peter 2007; Wang et al. 2011). Furthermore, studies with adults suggest that shy or socially anxious individuals prefer to communicate via channels with fewer interpersonal cues (i.e., email vs. face-to-face; Hertel et al. 2008) and lower synchronicity (i.e., social networking sites versus instant messaging; Chan 2011). Preliminary evidence from longitudinal studies suggests that the sense of social comfort provided by the online environment can result in increases in well-being and decreases in internalizing symptoms (Szwedo et al. 2012; Valkenburg and Peter 2009); however, few studies have controlled for the influence of offline social interactions in contributing to these positive outcomes, thus limiting these conclusions.

Social media may also provide new, compensatory opportunities for less popular adolescents in that these new media can provide an “escape” from the offline social hierarchies of their schools and communities. For marginalized or rejected adolescents, social media may provide a sense of belonging. Experimental work provides evidence for this compensatory effect, showing that even communicating with an unknown peer online can help adolescents restore a sense of self-esteem and reduce negative affect following a “cyberball” social exclusion task (Gross 2009). Further evidence comes from descriptive work outlining new opportunities for an entirely novel online behavior known as “identity experiments,” where the cue absence of the social media environment allows rejected adolescents to pretend to be someone else or present unrealistic or exaggerated versions of themselves online (Harman et al. 2005; Michikyan et al. 2014; Valkenburg and Peter 2008). The consequences of such behaviors are not yet clear; however, preliminary evidence suggests that engaging in online “identity experiments” can confer benefits for the development of social competence, particularly among lonely adolescents (Valkenburg and Peter 2008). Furthermore, social media can help connect youth to similar peers across wide distances, creating a sense of connection and community. For example, youth who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) can connect with other sexual and gender minority peers across the world, which can provide critically important social support for adolescents who might otherwise feel alone (Ybarra et al. 2015). The availability and cue absence of social media may present opportunities for LGBT youth to explore aspects of their identities and attraction in a community of similar peers (Hillier and Harrison 2007; Hillier et al. 2012).

Peer Influence

One of the most consistent findings across the peer relations literature has been that adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors are similar to those of their peers (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011). Research suggests that adolescents are especially susceptible to peer influence effects, perhaps due to the developmental characteristics of this period, including greater identity exploration, increased unsupervised time spent with peers, and valuing of peer approval (Prinstein and Giletta 2016). Research and theory regarding mechanisms of peer influence propose that adolescents may engage in behaviors to match the social norms of valued and desired groups, to receive social rewards in the peer hierarchy, and to foster positive self-identity (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011). Extensive research suggests that children tend to choose friends who are similar to themselves in behaviors and attitudes (i.e., selection effects) and also become more similar to their friends in behaviors and attitudes over time [i.e., socialization effects; Kandel (1978); see also Prinstein and Dodge (2008)]. Recently, researchers have posited that the unique features of the social media environment may produce a particularly powerful context for adolescent peer influence (Ehrenreich and Underwood 2016). In this section, we discuss numerous mechanisms by which social media transforms peer influence processes.

Amplification of Socialization Effects Via Social Media

In terms of socialization processes, the features of social media may amplify the speed, volume, and scale with which peer influence effects can occur. The publicness of the social media environment allows for content to be shared with a wide network of individuals, and for adolescents to view content posted by individuals outside of their immediate peer group (Ehrenreich and Underwood 2016). In addition, the availability of social media allows this content to be accessed with increased frequency and immediacy, at any time of day, from any location, with social media’s permanence ensuring that such content can be accessed repeatedly and shared over an extended period of time. Thus, within the social media context, the potential for information to spread quickly and widely exceeds that of traditional, offline environments (Berger 2014). Indeed, the power of social media “contagion,” or the rapid dissemination of content across social networks, has been the focus of some recent work. For example, large-scale studies employing data mining techniques have suggested the possibility for “emotional contagion” on social media, showing that users are more likely to post content matching the emotional valence of posts they have viewed on Facebook (Kramer et al. 2014) and Twitter (Ferrara and Yang 2015), thus influencing the affect of individuals across the social network. Other work provides evidence for the amplification of socialization processes by highlighting the speed with which content can be spread. A quasi-experimental study of social influence regarding college students’ joining Facebook groups, for example, emphasizes the “r-curve shaped diffusion process” by which information spreads at an exponential rate on social media (Kwon et al. 2014). Content is often described as “going viral”—a phrase that did not exist before the advent of social media—to exemplify the incredible speed and broad reach of influence processes occurring online (Berger and Milkman 2012).

While much of the research regarding peer influence processes via social media has focused on risk behaviors (as outlined below), it is important to highlight that the same amplified processes have the potential to aid in the spread of health promotion and risk prevention behaviors. The features of social media provide unique opportunities to rapidly spread health promotion messages, to create positive norms regarding behavior, and to reach adolescents who might not otherwise receive such information. A full discussion of social media-based intervention and prevention efforts is beyond the scope of this review; however, social media-based interventions have targeted a range of health behaviors among youth (Cushing and Steele 2010), including physical activity (Lau et al. 2011), smoking (Buller et al. 2008), asthma control (Joseph et al. 2007), and sexual health (Bull et al. 2012).

New Opportunities: Novel Experiences of Peer Influence

Peer influence processes may be transformed within the context of social media through opportunities for novel behaviors, such as accruing “likes,” sexting, and posting public and permanent risky content. The quantifiability of social media is likely to play an important role in creating new opportunities for reinforcement of behavior. For the first time, adolescents can receive measurable indicators of approval of their behavior (e.g., in the form of likes and comments), which is likely to be particularly reinforcing, and to encourage similar posts in the future. Relatedly, adolescents can view this measurable peer engagement on their peers’ posts and photographs, creating a clear indicator of which behaviors and attitudes are sanctioned within the peer network. Insight into the mechanisms by which this may occur is found in the first study to apply an fMRI paradigm to adolescent social media use. Through a simulation of the social media site Instagram, Sherman et al. (2016) found that when adolescents viewed photographs with higher numbers of likes, they were influenced to “like” those photographs as well. When viewing photographs with more likes, compared to fewer likes, adolescents showed greater activation in the precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus, which are areas relevant to social cognition and social memories, as well as the inferior frontal gyrus, which is important for imitation. Notably, these effects occurred whether photographs contained either neutral or risky (e.g., photographs depicting alcohol or drugs) content. In addition, these effects occurred despite the fact that participants were viewing photographs of individuals who were not known offline. It is possible that on adolescents’ actual social media networks, where adolescents view friends’ and acquaintances’ photographs, the reinforcing value of quantifiable indicators might be even greater, given the desire to engage in behaviors that match the social norms of valued or high-status individuals within a known, offline peer hierarchy (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011).

Peer influence processes may also be transformed through new opportunities for socialization around behaviors specific to the online context, as adolescents adopt the online behaviors of their peers. For example, longitudinal studies suggest that young people’s decisions about online privacy settings are shaped by norms about peers’ privacy settings (Saeri et al. 2014), as well as their peers’ actual privacy settings (Hofstra et al. 2016). More concerning, perhaps, is the tendency for adolescents to imitate the online behavior of their peers in posting risky online content. Studies indicate that adolescents are significantly more likely to “sext” and to post sexually suggestive content online when their peers have done the same (Rice et al. 2012). In addition, evidence suggests that adolescents who report a greater number of friends sharing alcohol references on social media are more likely to post such references themselves (Geusens and Beullens 2017). Interestingly, in this cross-sectional study, perceptions of peers’ posts were a stronger predictor of adolescents’ alcohol-related posting than were self-reports of their own drinking behavior. Similarly, a cross-sectional study of college students found that individuals reporting greater desire to adhere to alcohol-related social norms were more likely to post alcohol-related content, but not necessarily to consume more alcohol (Thompson and Romo 2016). These findings, though preliminary, point to the strong incentive for adolescents to match the online behavior of their peers, and the potential for social media to create biased norms surrounding offline risk behavior engagement.

Altered Qualitative Nature of Peer Influence: Increased Risky Content and Effects on Offline Risk Behaviors

In addition to amplifying and creating new opportunities for socialization processes, social media may also transform the domain of peer influence by changing the qualitative nature of this experience—specifically, by featuring a higher volume of risky behaviors, as compared to offline interactions. This may create qualitative differences in norms surrounding risk behaviors, including alcohol use and sexual risk behavior. One national survey indicates that as many as 68% of 16- to 17-year olds report having seen pictures online of their peers drinking, passed out, or using drugs (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University 2012). As indicated by social presence theory (Short et al. 1976), it may be that social media’s cue absence and asychronicity contribute to feelings of disinhibition that encourage posting risky content. As such, a growing body of work has examined the ways in which peer influence processes on social media contribute to adolescents’ health risk behaviors, with a particular focus on alcohol use and sexual risk behavior.

Evidence has accumulated to suggest that adolescents and young adults who are exposed to peers’ alcohol-related content on social media are longitudinally more likely to initiate and escalate drinking behaviors (Geusens and Beullens 2016; Nesi et al. 2017) and, in experimental studies, to show increased willingness to drink (Litt and Stock 2011). One possible mediator of this peer influence process is adolescents’ development of more alcohol-favorable descriptive and injunctive norms following exposure to alcohol content. Indeed, studies have shown that adolescents exposed to alcohol content on social media are more likely to endorse favorable alcohol norms (Beullens and Vandenbosch 2016; Fournier et al. 2013), and that these norms serve as a mediator of the associations between exposure and alcohol intentions and use (Geusens and Beullens 2016; Nesi et al. 2017). Furthermore, reflecting the potency of social media’s visualness in contributing to peer influence effects, studies have highlighted the role of alcohol-related photographs in changing norms and increasing use, particularly when photographs contain older or more popular peers (Litt and Stock 2011). One study found that exposure to peers’ alcohol-related photographs, but not text, longitudinally influenced adolescents’ use of alcohol (Huang et al. 2013).

It is important to note that many studies of alcohol-related influence processes via social media do not control for offline influence processes or behavior, thus precluding conclusions regarding discriminant associations between social media versus offline influence and alcohol use. However, evidence is beginning to accumulate to suggest that social media does, in fact, contribute additive effects to the peer influence process, thus providing further evidence for the transformation framework. For example, in a study of first-year college students, exposure to peers’ alcohol-related content on social media (i.e., text or pictures of their peers drinking, being drunk or hung-over) predicted one’s own drinking behavior six months later—above and beyond the effects of friends’ actual alcohol use (Boyle et al. 2016). Furthermore, a study of high school students found that exposure to friends’ online posts related to partying or drinking alcohol online were longitudinally associated with adolescents’ increases in alcohol use, controlling for the actual drinking behavior of those same friends (Huang et al. 2013). Taken together, these findings support the idea that the features of social media create a unique environment for the enactment of peer influence processes related to alcohol use, over and above such processes offline.

Peer influence processes on social media may alter the qualitative nature of peer influence by heightening the socialization of other risk behaviors as well. In terms of sexual activity, preliminary experimental results suggest that viewing sexually suggestive photographs on social media may influence norms around sex, highlighting the visualness of many social media sites. In a study of college students, those who viewed sexually suggestive Facebook photographs estimated that a greater percentage of their peers engaged in risky sexual behavior (e.g., having unprotected sex, having sex with strangers) and were more likely to report that they would be willing to engage in these behaviors (Young and Jordan 2013). Other work supports the idea that norms and beliefs about peers’ sexual beliefs may uniquely develop on social media, compared to other types of media. In a prospective longitudinal study of adolescents (van Oosten et al. 2017), researchers found that adolescents who were exposed to peers’ sexually provocative self-presentations on social media reported more favorable descriptive norms and prototypes of peers who engage in casual sex. Compared to other forms of media examined in this study (i.e., online pornography, sexually oriented television), exposure to peers’ sexualized social media images may have uniquely created perceptions of casual sex as both normative and desirable. This may be due to the publicness and availability of social media, which allow for frequent exposure to seemingly realistic portrayals of a range of peers. Beyond sexual activity, initial work suggests that exposure to peers’ risky social media content can influence other behaviors as well, including young peoples’ smoking attitudes and intentions (Yoo et al. 2016), actual smoking behavior (Huang et al. 2013), eating and weight-related beliefs and behaviors (for review, see Holland and Tiggemann 2016), and criminal activity (McCuddy and Vogel 2015).

Despite evidence to suggest the unique role that social media plays in influencing risky behaviors, however, the relationship between the social media environment and the development and reinforcement of social norms remains complex. On the one hand, theories of online disinhibition (Suler 2004) suggest that the cue absence and asynchronicity of the online environment may alter the qualitative nature of influence processes online by encouraging individuals to more freely express individual opinions and engage in more disinhibited behaviors than they might offline (Christopherson 2007). As such, we might expect adolescents to feel more comfortable posting content—even risky content—that falls outside of offline peer norms. On the other hand, as previously discussed, the publicness, availability, and permanence of the social media environment may actually amplify peer influence processes by creating and enforcing strong norms prescribing the types of content sanctioned in adolescents’ online peer groups. An experimental study of adults provides evidence for this dichotomy between the potential for stronger and weaker peer norms online (Woong Yun and Park 2011). In an online forum designed for discussion of polarizing social issues, individuals were equally likely to express their opinions whether or not they perceived those opinions to be popular offline—in other words, they were willing to post “anti-normative” opinions. However, individuals were less likely to post opinions that went against the majority opinion within the online forum at any given time, suggesting that norms within social media sites are likely to influence online behavior. Similarly, studies of online forums suggest that individuals are likely to match the style of other forum users who have posted before them (Welbers and de Nooy 2014). As such, social media may create an environment where some adolescents feel more comfortable posting risky content, with others then encountering strong incentives to mimic such online behavior.

New Opportunities: Compensatory Behaviors Through “Extreme Communities”

These increased opportunities for peer influence effects around risky behaviors may extend to include behaviors that, traditionally, have been considered “anti-normative” or extreme within the offline context. The availability and publicness of the social media environment may create compensatory opportunities for adolescents to seek out a wide range of peers with similar interests or concerns with whom they might not have the opportunity to connect offline. In many cases, this selection effect may be relatively harmless—for example, with online interest groups and pages devoted to specific music preferences or games (Subrahmanyam and Šmahel 2011). However, the potential for young people to seek out others engaged in risky, damaging, or otherwise “anti-normative” behaviors, such as disordered eating and self-injury, is equally possible (Reid and Weigle 2014).

Indeed, a growing body of the literature has identified the potential for both socialization and selection effects around “extreme communities” online (Bell 2007). For example, research has examined young people’s use of social media to promote eating disorders, i.e., through pro-anorexia blogs or communities within social networking sites (Juarascio et al. 2010; Levine and Chapman 2011), and studies are beginning to explore the role of social media in spreading suicidal and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (Dyson et al. 2016). Social media’s cue absence and asynchronicity may encourage adolescents with mental health difficulties to share their experiences with disordered eating or self-injury online as a means of receiving social support. Simultaneously, the features of social media may create a context in which these behaviors are reinforced, imitated, and made to feel “normative” within certain online communities—thus reinforcing and encouraging such behaviors (for a review, see Reid and Weigle 2014). A qualitative study of pro-anorexia bloggers, for example, suggests that the stigma associated with eating disorders offline is what drives many individuals to such sites; once there, however, powerful norms regarding language and behavior may reinforce individuals’ eating disorder identities (Yeshua-Katz 2015). Studies also highlight the ease and scale with which such content can be socialized, indicating that many pro-eating disorder Twitter accounts have hundreds of followers, approximately half of whom have also posted pro-eating disorder tweets (Arseniev-Koehler et al. 2016).