Abstract

Introduction

Task shifting interventions have been implemented to improve health and address health inequities. Little is known about how inequity and vulnerability are defined and measured in research on task shifting. We conducted a systematic review to identify how inequity and vulnerability are identified, defined and measured in task shifting research from high-income countries.

Methods and analysis

We implemented a novel search process to identify programs of research concerning task shifting interventions in high-income countries. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and CENTRAL to identify articles published from 2004 to 2016. Each program of research incorporated a “parent” randomized trial and “child” publications or sub-studies arising from the same research group. Two investigators extracted (1) study details, (2) definitions and measures of health equity or population vulnerability, and (3) assessed the quality of the reporting and measurement of health equity and vulnerability using a five-point scale developed for this study. We summarized the findings using a narrative approach.

Results

Fifteen programs of research met inclusion criteria, involving 15 parent randomized trials and 62 child publications. Included programs of research were all undertaken in the United States, among Hispanic- (5/15), African- (2/15), and Korean-Americans (1/15), and low socioeconomic status (2/15), rural (2/15) and older adult populations (2/15). Task shifting interventions included community health workers, peers, and a variety of other non-professional and lay workers to address a range of non-communicable diseases. Some research provided robust analyses of the affected populations’ health inequities and demonstrated how a task shifting intervention redressed those concerns. Other studies provided no such definitions and measured only biomedical endpoints.

Conclusion

Included studies vary substantially in the definition and measurement of health inequity and vulnerability. A more precise theoretical and evaluative framework for task shifting is recommended to effectively achieve the goal of equitable health.

Keywords: Systematic review, Noncommunicable diseases, Lay health workers, Vulnerable populations

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), task shifting involves the rational redistribution of health care tasks within health workforce teams. Any diagnostic, therapeutic, health promotion or other health care tasks are reassigned from highly trained workers such as physicians, to workers with shorter training or fewer qualifications, such as nurses or community health workers, to make better use of limited health human resources or to improve access to essential care (World Health Organization, 2007, Chen et al., 2004).

Though task shifting is not a new approach to health human resources shortages, the term “task shifting” was coined in the context of the HIV/AIDS crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa (Callaghan et al., 2010, Heller, 1978, Sidel, 1972). This approach has received substantial attention from policymakers, health authorities, clinicians, and researchers in low- and middle-income countries for increasing health services and access to timely care, and in high-income countries for enhancing access to care, especially for vulnerable or underserved populations (Chen et al., 2004, World Health Organization, 2007).

By improving access to care for critical population health problems, task shifting interventions can enhance population health by delivering essential care, and can also enhance health equity by making care more accessible to underserved populations. The clinical and epidemiological effectiveness of many task shifting interventions has been well demonstrated. Systematic reviews demonstrate that task shifting can reduce morbidity and mortality and deliver essential care for infectious diseases, chronic and non-communicable diseases, maternal-child health, and emergency care (Kim et al., 2016, Lewin et al., 2010, Joshi et al., 2014). Task shifting from physicians to nurses and other providers has also been widely studied in high-income countries, especially to increase access to primary care interventions (World Health Organization, 2007, World Medical Association, 2009; Maier and Aiken, 2016).

Less is known about the effects of task shifting on health equity. Though WHO Director-General Margaret Chan has described task shifting as “the vanguard for the renaissance of primary health care”, WHO guidelines also caution that task shifting may threaten health equity if improved access to care arrives at the expense of quality, comprehensiveness, and patient-centeredness (World Health Organization, 2007, PLOS Medicine Editors, 2012). Task shifting can redress inequities by reducing reliance on the most trained and potentially least accessible professionals, but can have paradoxical effects on health equity by reducing or stratifying quality of care (World Medical Association, 2009). In this context, it is reasonable to ensure that task shifting interventions achieve their intended goals to reduce health inequity by assessing effects on health equity when studying or evaluating task shifting interventions (Orkin et al., 2018).

It is only possible to determine whether task shifting interventions are effective at improving health equity if the inequities of interest are defined and measured. The World Health Organization and Cochrane Collaboration call for clarity and rigour in research on health equity and equity-related outcomes (Lewin et al., 2010, Welch et al., 2016, Marmot et al., 2008). For most health conditions addressed through task shifting interventions, measures of clinical effectiveness are well established (World Health Organization, 2007, Kim et al., 2016, Lewin et al., 2010). However, consistent definitions and outcome measures with respect to inequity and population vulnerability are relatively limited (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006, Dixon-Woods et al., 2005, Flaskerud and Winslow, 1998). If task shifting interventions are intended to redress inequities, research on task shifting should offer a justified and robust evaluative approach suited to understand the effects of task shifting on health equity.

We conducted a systematic review to identify how inequity and population vulnerability is defined and evaluated in programs of research that incorporated a randomized control trial on task shifting in high-income countries. Our review questions were: (1) Among task shifting interventions that have been studied in high-income countries using randomized trials, how are health inequity or population vulnerability identified and defined? (2) What methods and indicators are used to (a) describe, characterize and measure the target population’s baseline status and (b) the intervention’s impacts on the target population’s vulnerability and inequity?

Methods

We published a review protocol based on the PRISMA Statement and registered our protocol through the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Orkin et al., 2018; Welch et al., 2016; Moher et al., 2016).

Health equity and vulnerability

We defined health inequities as disparities in health or health care that are “unnecessary, avoidable, unfair and unjust” (Marmot et al., 2008, Whitehead, 1992). We defined vulnerability as an individual or population with an increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater wrong (Hurst, 2008). Since vulnerabilities predispose an individual to wrongs or unjustifiable disparities, vulnerability is effectively a precondition for inequity. These definitions emphasize obligations to compress inequities, protect from harm, and respond to the needs of those who are vulnerable (Clark & Preto, 2018).

Review strategy

Our review was designed to identify programs of research concerning task shifting interventions that incorporate a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We limited our review to programs of research incorporating a RCT to focus our attention on interventions that had been studied using methods that benefit from randomisation and relatively high internal validity. Programs of research may incorporate multiple studies, methodologies, products and outputs concerning a unified theory, concept, intervention, or investigator. Investigators conducting a RCT on task shifting interventions may consider inequity and vulnerability concepts in detail, but may not report those concepts in the trial publication itself. Searching for programs of research rather than individual studies is therefore better suited to reveal concepts that may not appear in the RCT publication.

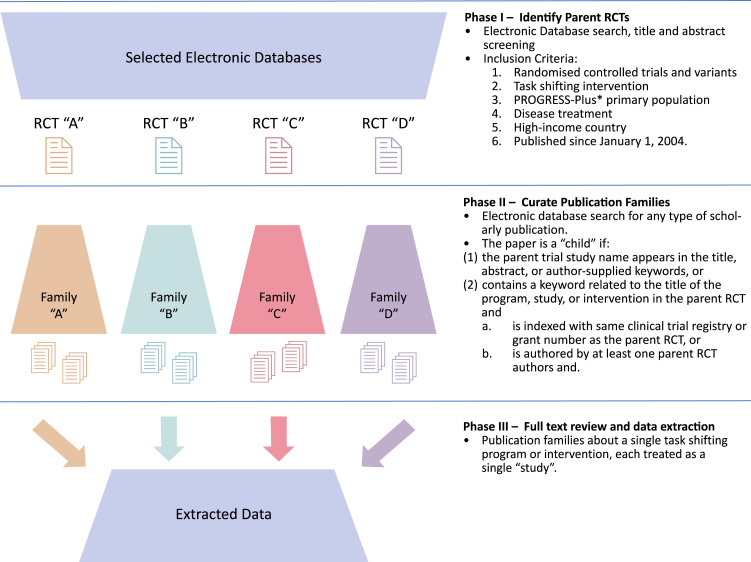

Our search and data extraction process followed three phases. Phase I retrieved all RCTs or RCT variants concerning task shifting interventions, which we refer to as “parent trials”. In Phase II, we identified non-RCT publications related to the parent trials, which we refer to as “child” publications. These child publications were reports from the same research program as the parent trial, including process evaluations, embedded studies, and secondary analyses. We then bundled parent RCTs and child papers into publication collections, which we refer to as “families”. For example, if an investigator group’s research program on a task shifting intervention included a RCT, a qualitative study, an economic evaluation, a scale-up study, and a quality improvement paper, we first retrieved the parent RCT and then identified and include the other child publications all as a single “publication family”. Phase III involved data extraction, treating each family as the unit of analysis (Fig. 1) (Orkin et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

Search strategy schematic and inclusion criteria.

Phase I – randomized controlled trial identification

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. We retrieved publications concerning in-progress trials using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

We used a two-concept search strategy intended to identify papers containing at least one search term from each of the “randomized trial” and “task shifting” concepts. We collected and validated our search terms from reviews on task shifting (Kim et al., 2016, Lewin et al., 2010, Joshi et al., 2014). We adapted the final MEDLINE search strategy to each database. Search terms are published elsewhere (Orkin et al., 2018).

We screened the references of relevant systematic reviews, WHO recommendations and guidelines on task shifting, and the studies identified through database searching (World Health Organization, 2007, Kim et al., 2016, Lewin et al., 2010, Joshi et al., 2014). Other forms of grey literature, such as conference proceedings, clinical trial registrations and theses, were not included unless found through reference list scanning as detailed above. We corresponded with two study authors to request further information as required. We updated the MEDLINE search following the study selection and data extraction process to 6 December 2016.

Study inclusion/exclusion

Studies were included in the review if they met all of the following criteria (Fig. 1):

-

(1)

Randomized Controlled Trials and Variants: This includes completed RCTs or variants such as cluster-randomized trials.

-

(2)Task Shifting Interventions: We used the WHO definition for “task shifting”:Task shifting involves the rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Specific tasks are moved, where appropriate, from highly qualified health workers to health workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications in order to make more efficient use of the available human resources for health (World Health Organization, 2007).

Task shifting implies the transfer of existing health interventions to new workers, and is distinguished from introducing new workers with new tasks. We excluded trials comparing a usual care control with an intervention involving usual care plus a new cadre of health worker, unless the intervention worker assumed tasks generally undertaken in the usual care system.

-

(3)

PROGRESS-Plus primary population: We included studies undertaken in any population that may face health disadvantage as defined by the PROGRESS-Plus framework (place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, social capital, socioeconomic position, age, disability, sexual orientation, other vulnerable groups) (O’Neill et al., 2014, Kavanagh et al., 2008).

-

(4)

Disease Treatment: We included studies of interventions that provide treatment of already diagnosed or symptomatic disease. For example, studies concerning interventions such as cancer screening programs in asymptomatic individuals, case-finding or public awareness campaigns without integrated disease treatment interventions were excluded.

-

(5)

High-Income Countries: We included studies undertaken in high-income countries according to the 2016 World Bank classification system (World Bank, n.d.). We restricted the review to high-income countries because inequity and vulnerability are relative concepts that have fundamentally different meanings in low- and middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. In settings with more limited health professional workforces, task shifting often takes on the form of developing health systems and health workforce teams de novo, rather than shifting tasks away from existing professions.

Date: We included studies published after 2004 to avoid anachronistic assessments of studies published before sentinel events in the scholarly history of task shifting and health equity, including the 2007 WHO Global Recommendations and Guidelines on Task Shifting, the 2008 PROGRESS-Plus Framework, the 2008 Lancet Commission on the Social Determinants of Health and the 2010 Lancet Commission on Health Professionals for a New Century (World Health Organization, 2007, Welch et al., 2016, Marmot et al., 2008, Relevo, 2011, Frenk et al., 2010).

There were no language restrictions or exclusion criteria.

Information management, selection of studies

De-duplicated bibliographic data were uploaded to a data management interface developed using Google Sites (Orkin et al., 2016). Reviewers trained on a set of 100 citations, including 10 studies meeting some or all inclusion criteria. Titles and abstracts were assessed by at least two reviewers. Discrepancies were addressed by the lead investigator. Studies deemed eligible at this stage were considered parent trials.

Phase II – Curate publication families

Parent trials from Phase I advanced to Phase II, in which we identified and retrieved child papers from the same research program. For each RCT, we extracted author names, study identifiers, and used these terms to retrieve related publications from the same research program. MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science were searched to identify potential child papers, including abstracts and conference presentations, for each of the included parent RCTs with individually designed search strategies using bibliographic and study identifiers of the parent RCT. Search strategies retrieved child papers indexed with the same study name, trial registry or grant number, or authored by the same investigators as the parent trial (Fig. 1). We used “related studies” and “cited by” functions in bibliographic databases to curate these families. If a Phase II search revealed multiple RCT publications in a research program, the most appropriate RCT for the scope of this review was reassigned as the parent trial. No date limiter was placed for child papers and searches were extended to December 2017.

Phase III – Full text review and data extraction

Two reviewers assessed the full text of all studies included at Phase II. Disagreements were resolved through the consensus of two reviewers and a lead investigator. Two reviewers independently extracted data from the parent RCT in each family:

-

(1)

bibliographic information;

-

(2)

study aim/question;

-

(3)

study characteristics (design, sample size, number of arms);

-

(4)

intervention and control (type and characteristics of interventions and control);

-

(5)

study setting (country, region, community/level of health service), health condition, and patient population (age, gender, ethnicity, language, other PROGRESS-Plus categories);

-

(6)

outcome measures (type and definition of outcome, time of assessment); and

-

(7)

results.

Outcome measures were sorted on the basis of their relevance to disease or health equity and vulnerability. For each publication family, we collected data on the types of studies in the family and study objectives. Across each publication family, we extracted definitions of health inequity/vulnerability being addressed through the intervention.

Quality: Individual studies and across studies

Two reviewers assigned each study a score on a 5-point scale corresponding to the extent with which equity and vulnerability were defined and assessed in each program of research (Supplement A). The first score, Definition of Health Equity or Vulnerability, was intended to capture the extent to which the family of studies identified a population facing health inequities or vulnerabilities, and whether those inequities and vulnerabilities were fully explored and theorized. A score of 1 for this first measure was prohibited, given that inclusion criteria captured parent trials involving a population characterized by the PROGRESS-Plus framework. The second score, Equity-Relevant Outcome Measure, was designed to capture whether the program of research evaluated the intervention’s effects on population equity (Marmot et al., 2008). We tested the internal validity of the tool using 15 RCTs meeting inclusion criteria and found that the tool did not offer the inter-rater reliability needed to permit a single reviewer to assign scores, so we proceeded with a consensus score involving two reviewers (Supplement B).

We summarized the included studies’ characteristics and findings using a narrative and tabular approach (Popay et al., 2006).

Results

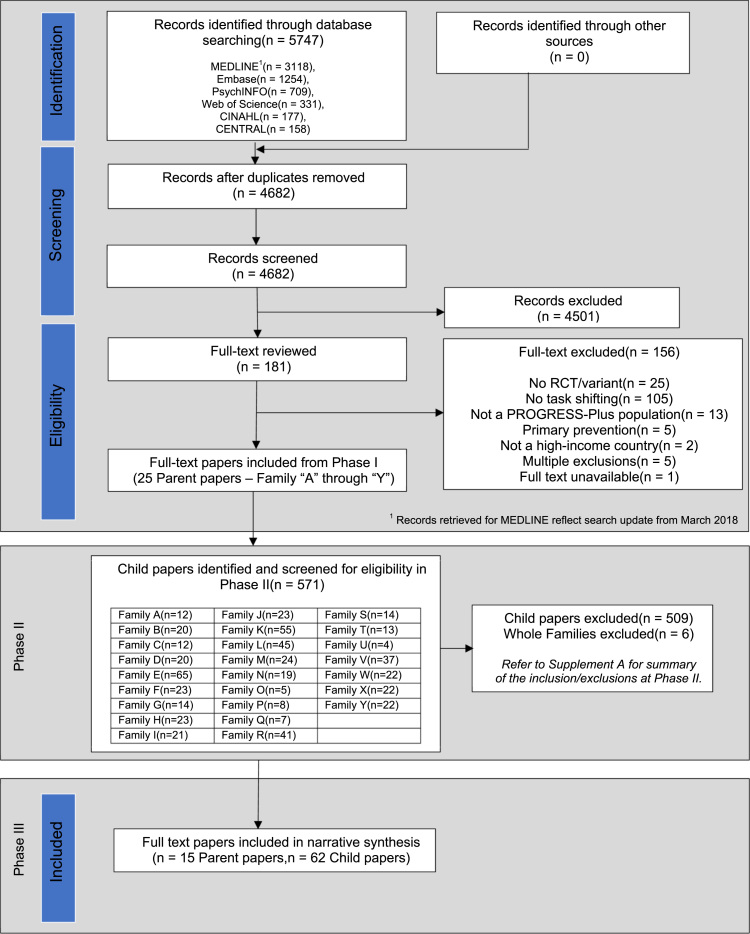

Phase I of our search revealed 4682 unique citations, of which 25 met eligibility criteria as parent trials. Phase II of our search identified 571 child papers. Following full-text review, 15 families met eligibility criteria composed of 15 parent trials and 62 child papers (Fig. 2 and Supplement C: PRISMA Flowchart Extension for Phase II).

Fig. 2.

Modified PRISMA flowchart.

We refer hereafter to families as “F[n]”, where n is the family number identified in Table 1. For example, F1 refers to family 1, and F3b refers to “family 3, child paper b”. Citations for parent and child papers are in Supplement D: Annotated Bibliography.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included families of papers.

|

|

ACG (Attention Control Group); CAD (Coronary artery disease); CG (Control Group); CHF (Congestive Heart Failure); CHW (Community Health Worker); CI (Confidence Interval); DSME (Diabetes Self-Management Education); DSMS (Diabetes Self-Management Support); HbA1c (Glycated hemoglobin level); HRQoL (Health-related quality of life); HTN (Hypertension); ICS (Inhaled corticosteroid); IG (Intervention Group); KCCQ (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire); NA (Not available); NY (New York); RCT (Randomized Controlled Trial); RD (Risk difference); RN (Registered Nurse); RR (Relative risk); SBP (Systolic blood pressure); SE (Standard error); SES (Socioeconomic status); SW (Southwestern); T2DM (Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus); USA (United States of America)

Studies retrieved

Table 1 provides a summary of the included families of research. Parent trials were predominantly 2-arm parallel RCTs with randomization conducted at the individual level (10/15 families; F2/3/5/6/7/8/9/10/11/13). Four of the parent trials were 3-arm RCTs (F1/4/14/15), and there was one cluster RCT with analysis conducted at the individual level (F12). Sample sizes ranged from 75 to 360 participants.

Child papers included pilot studies, study protocols, cross-sectional and post-hoc analyses, embedded cohort and qualitative studies, descriptive studies, bioethical and conceptual analyses, and commentaries (Supplement D). Families ranged in size from 2 (1 parent, 1 child paper) to 14 papers (1 parent, 13 child papers).

The families of research included in the review were all undertaken in the United States. Parent trials mostly involved populations facing health inequities characterized by ethno-cultural minority status, including Hispanic, Latino, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, African American, Korean American or multiethnic and diverse communities. Other vulnerable populations included people with low socioeconomic status, rural populations, or older unpartnered adults.

All of the included families of research concerned the management of chronic non-communicable diseases. Eight families concerned initiatives to improve the management of diabetes among minority populations. Other families of papers addressed task shifting interventions for hypertension (2/15), asthma (2/15), heart failure (1/15), coronary artery disease (1/15) and chronic insomnia (1/15).

Nine of the families of papers tested an intervention involving community health workers (CHWs). Other task shifting interventions involved peer workers (2/15), non-professional health coaches (2/15), lay health educators (2/15), faith community nurses (1/15) or advanced practical nurses (1/15). Control groups received usual (3/15), standard (1/15) or enhanced usual care (1/15), attention (2/15) or waitlist controls (2/15), informational mailings (4/15), physician interventions (1/15), or interventions involving health coaches (1/15), CHWs (2/15) or lay health workers (1/15).

Table 1 provides a summary of the parent trials’ primary and secondary endpoints and reported effect sizes. Most of the primary endpoints in the included parent trials concerned disease-oriented outcomes. For example, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was the primary endpoint in all trials concerning diabetes. Some parent trials assessed primary endpoints that lend themselves to equity-related analyses, such as self-efficacy for recovery behaviours among older unpartnered adults with coronary artery disease (F14) or asthma self-management skills among rural children with asthma and their parents (F12). Eight of the included parent trials incorporated secondary outcomes that were directly relevant to a proposed theory of inequity for the target population (8/18 families; F2/3/4/6/9/10/12/13). For example, one study proposed that diabetes might place an inequitable social burden on people with low socio-economic status and measured the effect of a home-based CHW intervention on a social burden subscale (F2).

Definition of health inequity and population vulnerability

The included studies scored between 2 and 5 for the definition of the study population’s health equity concerns or vulnerability (Table 2). For example, F1 is a family of studies on the effectiveness of CHWs to treat type 2 diabetes among Hispanic Americans. The authors describe the study population:

[In New York City (NYC)], Hispanics comprise 28.6% of the population and are the third largest ethnic group in NYC with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Thus, disease prevention and management strategies clearly are a priority for the Hispanic population in NYC. (F1) (Aponte, Jackson, Wyka, & Ikechi, 2017).

Table 2.

Equity and vulnerability definitions and measures scores.

|

Family |

Definition of health equity/vulnerabilitya |

Equity-relevant outcome measureb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Parent citation | Score | Notes | Score | Notes |

| 1 | Aponte, Jackson, Wyka, & Ikechi (2017) | 2 | This study was undertaken in a population characterized through the PROGRESS-Plus framework (Hispanics). However, their vulnerability was not explicitly identified. | 1 | All outcomes were disease-related. There was no discussion on the equity implication of these outcomes. |

| 2 | Nelson et al. (2017) | 4 | The link between low income, ethnic/minority populations and high disease burden is clearly identified. However, this link is not theoretically driven and grounded as a guiding framework in the design of this study. | 3 | Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and healthcare utilization are potentially equity-relevant, but it is not clearly established as such. |

| 3 | Lutes et al. (2017) | 5 | Inequity/vulnerability of this study’s population is fully theorized (using a culturally-delivered Small Changes lifestyle approach) in their protocol publication. | 4 | Some outcomes were equity-relevant (self-reported empowerment, self-efficacy and self-care) and relevant to alleviating or redressing health inequities faced by the population of interest. |

| 4 | Kim et al. (2016) | 4 | This family clearly defines the Korean American population’s vulnerability to diabetes, diabetes self-management and other sociocultural barriers. | 3 | Some outcomes relevant to health equity includes self-efficacy, diabetes-related quality of life, depression and self-care. |

| 5 | Palmas et al. (2014) | 3 | Increased incidence of T2DM in Hispanic Americans relative to white population is recognized but is not clearly defined as an inequity. | 1 | All outcomes were disease-related. There was no discussion on the equity implication of these outcomes. |

| 6 | Rothschild et al. (2014) | 4 | Study describes burden of disease in target population, and implicitly theorizes that relationship as related to cultural, linguistic and educational barriers. | 3 | Self-efficacy may be relevant to alleviating health effects of PROGRESS-Plus variables, but this is not explicitly characterized in the study. |

| 7 | Tang et al. (2014) | 2 | This study was undertaken in a low-income, Latino population. However, inequity was not clearly recognized and established. | 1 | All outcomes were disease-related. There was no discussion on the equity implication of these outcomes. |

| 8 | Gary et al. (2009) | 4 | This paper defines and explores the vulnerability of Baltimore’s African American population with diabetes, and offers some theoretical analysis, however the program of research was not sufficiently theorized to connect vulnerability of the targeted population with interventional design (and outcomes by extension). | 3 | Health care utilization (emergency department visits and hospitalizations) is a primary outcome for this study, which is relevant to alleviating impact of vulnerability in this population. Food frequency questionnaire and access to/use of computers are also potentially equity-relevant variables. However, the implications of these outcomes were not explicitly characterized as relevant in measuring effects of health inequity/reducing vulnerability for this population. |

| 9 | Margolius et al. (2012) | 2 | Although this study serves a low-income predominantly minority population, their vulnerability/inequity is not identified. The research program does place emphasis on population-wide health resource shortages in primary care medicine. | 1 | All outcomes were either related to disease or clinician acceptability of the intervention. |

| 10 | Baig, Mangione, Sorrell-Thompson, & Miranda (2010) | 3 | Family of papers identify that low-income, faith communities may face health inequities due to inadequate access to care and support with adherence to care. | 3 | Physician visits, hypertension knowledge and self-care have equity implications, but were not specifically characterized as such. |

| 11 | Martin et al. (2015) | 4 | The parent paper only identifies the epidemiological burden of asthma in Puerto Rican youth in Chicago and does not clearly establish the vulnerability of this population. Subsequent child papers describe the relationships between sociodemographic factors, including poverty, lack of health insurance, language and cultural differences and other community experiences on the burden of disease and outcomes for asthma in this population. | 3 | Most outcomes are disease-related. However, the relationship between caregiver depressive symptoms and asthma control in this population is thoroughly explored in one of the child papers (Martin et al., 2013). |

| 12 | Horner and Fouladi (2008) | 5 | The asthma health education model was used as an underlying theory for the study and included many variables including SES, environment, family risk factors, etc. that contribute to asthma. | 3 | The secondary outcomes (asthma self-efficacy) are effectively presented as equity-relevant outcomes due to the underlying theory but is not explicitly characterized as such in the primary study. There are no outcomes specifically designed to measure the interventions’ effect on health inequities experienced by rural children. |

| 13 | Dickson et al. (2014) | 5 | This research program utilizes the situation specific theory of HF self-care. This model provides a robust theory for how sociocultural factors including ethnicity, culture and economic factors would generate inequities in HF care and outcomes. | 3 | The study outcomes were self-care and HRQoL. In the context of the study's theoretical model, these may be relevant to alleviating health inequities, but it wasn’t characterized or analyzed as such. |

| 14 | Carroll and Rankin (2006) | 4 | The papers within this research program draw attention to the mechanisms through which being unpartnered would lead to reduced post-MI self-care and self-efficacy (mostly related to a truncated social network). The authors do not, however, deliver a fully theorized model of the relationship between post-MI management and unpartnered older adult. | 3 | Self-efficacy is effectively presented as an equity-relevant outcome due to the underlying theory but is not explicitly characterized as such in the primary study. |

| 15 | Alessi et al. (2016) | 3 | The primary trial concerns older veterans with chronic insomnia. Vulnerability/inequity with respect to this population is not theorized. However, a child paper from this family discusses PTSD and how this may affect sleep patterns. | 1 | Outcomes were all related to sleep and were not equity-relevant. |

PROGRESS-Plus: place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, social capital, socioeconomic position, age, disability, sexual orientation, other vulnerable groups.

Definition of Health Equity/Vulnerability: 1=No definition; 2=Study undertaken in a population/setting characterized through the PROGRESS-Plus framework, but vulnerability/inequity not clearly defined or theorized; 3=Study undertaken in a population/setting characterized through the PROGRESS-Plus framework, but not clearly defined or theorized; 4=Targeted inequity and/or population vulnerability defined and explored; and 5=Targeted inequity and/or population vulnerability defined and theorized explicitly.

Equity-Relevant Outcome Measure: 1=No relevant outcome measure; 2=No relevant outcome measures. Discussion of equity implications of other measures; 3=Outcomes relevant to alleviating or redressing health effects of PROGRESS-Plus variables, but not explicitly characterized as relevant to equity; 4=Some outcomes relevant to alleviating or redressing health effects of PROGRESS-Plus variables; and 5=Study specifically designed to measure effects on health inequity or reducing vulnerability.

This definition identifies a disparity of disease prevalence, but does not define or theorize that difference, nor hypothesize how a task shifting intervention might serve to correct or redress the disparity. The family received a definition score of 2.

On the other end of the spectrum, F3 is a parent trial assessing the impact of a CHW-delivered intervention designed to treat Type 2 Diabetes among African American Women, with child papers including a design and rationale paper, a doctoral dissertation, and three cross-sectional studies. F3 offers a rigorous theorization of the population and intervention:

Many African American women in the southeastern U.S.[A.] live in isolated, impoverished, rural communities without state-of-the-art diabetes care. In these settings there is urgent need for new community-based approaches that are tailored to the behavioral and psychosocial challenges known to be twice as common among African Americans with T2DM. Addressing these is critical because such problems and challenges are associated with poor glycemic control, increased risk of complications, premature mortality, and persistent disparities. (F3a) (Cummings et al., 2013).

The paper theorizes that the observed difference in health status is due in part to behavioural and psychosocial challenges, and posits that the intervention might correct an inequity by interrupting the relationship between the population under study and the health disparity observed. The family of papers was assigned a definition score of 5.

Measurement of health inequity and population vulnerability

The included families received scores ranging from 1 to 4 for equity-relevant outcome measures (Table 2). No studies were designed specifically to measure effects on health inequity or vulnerability to receive a score of 5. Some families of studies offered little or no evaluation of the intervention’s effect on health equity. For example, F9 involved a parent trial designed to evaluate the impact of equipping health coaches to titrate blood pressure medications in a low-income minority population. All outcomes were biomedical or relate to physician acceptability of the intervention.

[B]lood pressure control was achieved without added physician time; in fact, the number of physician visits for study patients dropped in the 6 months during and after the intervention. With these interventions, blood pressure can thus be improved without increasing demand on physician time. (F9) (Margolius et al., 2012).

The study measured outcomes on blood pressure and on reducing physician visits but did not assess whether the intervention interrupted any relationship between the population’s income status, minority status, and hypertension. The family was assigned an equity-related outcome score of 1.

Other studies offered a robust evaluation of the task shifting intervention’s effects on health equity and vulnerability. Having established a relationship between African American women, behavioural and psychosocial challenges, and poor diabetes care, F3 then established secondary outcome measures that were relevant to those inequities, including participant empowerment, self-efficacy, and self-care:

These complex behavioral changes may impact role functioning, a concern among African American women who often care for others in their family, often with limited social and financial support. Due to this increasing complexity and burden of self-care behaviors, many female patients experience increased emotional distress that has been reported in more than 40% of patients with T2D. This emotional distress related to diabetes has been associated with inadequate self-care behaviors, medication non-adherence, and poor glycemic control (F3b) (Cummings et al., 2017).

The family of papers characterized the relationship between self-efficacy, empowerment and the health inequities faced by the population under study, and then measured the intervention’s impact on the hypothesized relationships. No parent trial or family of studies was explicitly designed to evaluate the impact of a task shifting intervention on alleviating or redressing health inequity or vulnerability as identified.

Supplement E provides quotes from each family of studies to support the assigned scores.

Discussion

This review exposes a disconnect between the stated purpose of task shifting initiatives and the approach to their development and evaluation. Some programs of research engage with health equity through rich theoretical models and apply new cadres of workers with the explicit goal of addressing those inequities or disrupting the pathway between a vulnerable subpopulation and its poorer health outcomes. Other task shifting enterprises make no such connection and are focused exclusively on biomedical outcomes among the patients receiving care. The definition, measurement, and conceptual consideration of health equity and population vulnerability all vary profoundly across different task shifting interventions.

This review process exposes theoretical and conceptual gaps in the working definitions of task shifting. We found that the accepted WHO definition for task shifting lacked specificity because it is prone to the unhelpfully broad inclusion of any intervention that engages new or different cadres of workers, volunteers, peers or patients in health service delivery. We focused our definition on the intent of the program rather than the workers involved. We classified programs as “task shifting” when workers with less training were engaged with the intent to redistribute or reassign health care tasks away from existing professions with more training. For example, we see training CHWs to independently alter prescription anti-hypertensives as a task shifting intervention, and included such a project (F9) (Margolius et al., 2012). In contrast, we excluded a project where CHWs were added to an interdisciplinary team managing cardiac risk factors without empowering or authorizing the new worker to take on tasks generally restricted to other professionals (Dennison et al., 2007). In this latter example, the new worker provides an additive, shared, or complementary service, rather than overtly “shifting” a task generally restricted to existing professionals. Other reviews have not made this distinction based on intent, and defined task shifting as any involvement of non-professional, lay, or paraprofessional actors in any capacity (Lewin et al., 2010).

While an inclusive definition for task shifting may have benefits, referring to all new health care collaborations — ranging from peer navigation to patient self-management — as task shifting may be unhelpful. Terms such as “task sharing” may broaden definitions even further. Such an inclusive approach also under-recognizes health care as both a profession and widespread civic function that always engages a range of professional and non-professional collaborators and relationships. Centering a definition of task shifting on the involvement of workers with less training, rather than on the intent to move tasks and redesign health care delivery, may also detract from task shifting’s origins in health equity, community empowerment, and access to care. As a concept for healthcare service delivery and inquiry, more work is needed to bring robust conceptual frameworks and a more specific definition to task shifting.

Our review has limitations. We restricted our search to high-income countries to assess the conceptual treatment of health equity in settings with established workforces of health professionals. Our results are not generalizable to low- or middle-income countries, which merit independent analysis. Although our search yielded only studies concerning non-communicable chronic diseases based in the United States, our search strategy was not restricted to specific disease domains or regions. Eligible programs of research from other jurisdictions or involving acute or communicable conditions may use terminology not captured by our search. Finally, the scoring tool we developed did not have strong inter-rater reliability. Although this is a limitation of the tool itself, scores were applied by consensus of the review team to overcome inter-rater reliability concerns.

The strength of this review is its broad search strategy. This novel multi-phase methodology elicited programs of research rather than singular papers. This approach yielded a deeper appreciation of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks involved in empirical research enterprises, and may have a role in other reviews of conceptual topics in health research. Though other scholars have pointed to the need for an improved theoretical basis and evaluative approach for task shifting and health equity, this review offers a systematic analysis of these concerns (Callaghan et al., 2010, Shah et al., 2013).

We recommend that program designers and evaluators define and describe the purpose of their task shifting interventions explicitly with respect to the affected population. Where the goals of task shifting interventions include redressing a health inequity or population vulnerability, the inequities faced by target populations should be clearly identified and theorized. Interventions should be evaluated not only on the basis of their biomedical impacts, but also on their equity-related effects. Health equity impact assessments and other emerging frameworks provide suitable methods for these evaluations (PLOS Medicine Editors, 2012, Povall et al., 2014, Asada, 2005).

Conclusions

Task shifting is an important strategy to deliver essential health services and redress health inequity among vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. Ideally, task shifting interventions should deliver both clinically effective interventions to reduce disease burden as well as reductions in health inequity or population vulnerability. Some programs of research concerning task shifting interventions offer a thorough conceptualization and evaluation of effects on health equity, but often these concepts go undertheorized and under-evaluated in the resulting program development and research. Task shifting may merit a more precise definition and conceptual framework to guide program development, implementation and evaluation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Camryn R. Rohringer, André McDonald and Emma Mew for their help with establishing the study database and initial title and abstract screening. We also thank Sylvia Lyons for her help with figures and manuscript formatting.

Acknowledgments

Project funding

Orkin is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Program (#358790), the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine, and the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute (Toronto, Canada). Martiniuk is salary funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Fellowship.

Declarations of interest

None.

Ethics approval statement

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100366

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Alessi C., Martin J.L., Fiorentino L., Fung C.H., Dzierzewski J.M., Rodriguez Tapia J.C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in older veterans using nonclinician sleep coaches: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(9):1830–1838. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte J., Jackson T.D., Wyka K., Ikechi C. Health effectiveness of community health workers as a diabetes self-management intervention. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research. 2017;14(4):316–326. doi: 10.1177/1479164117696229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada Y. A framework for measuring health inequity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(8):700–705. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.031054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig A.A., Mangione C.M., Sorrell-Thompson A.L., Miranda J.M. A randomized community-based intervention trial comparing faith community nurse referrals to telephone-assisted physician appointments for health fair participants with elevated blood pressure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(7):701–709. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1326-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan M., Ford N., Schneider H. A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Human Resources for Health. 2010;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D.L., Rankin S.H. Comparing interventions in older unpartnered adults after myocardial infarction. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;5(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Evans T., Anand S., Boufford I., Brown H., Chowdhury M., Wibulpolprasert S. Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. The Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark B., Preto N. Exploring the concept of vulnerability in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2018;190:E3089. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D.M., Lutes L.D., Littlewood K., DiNatale E., Hambidge B., Schulman K. EMPOWER: A randomized trial using community health workers to deliver a lifestyle intervention program in African American women with type 2 diabetes: Design, rationale, and baseline characteristics. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36(1):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D.M., Lutes L.D., Littlewood K., Solar C., Hambidge B., Gatlin P. Impact of distress reduction on behavioral correlates and A1C in African American women with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: Results from EMPOWER. Ethnicity Disease. 2017;27(2):155–160. doi: 10.18865/ed.27.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison C.R., Post W.S., Kim M.T., Bone L.R., Cohen D., Blumenthal R.S., Hill M.N. Underserved urban african american men: Hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. American Journal of Hypertension. 2007;20(2):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson V.V., Melkus G.D., Katz S., Levine-Wong A., Dillworth J., Cleland C.M. Building skill in heart failure self-care among community dwelling older adults: Results of a pilot study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2014;96(2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M., Cavers D., Agarwal S., Annandale S., Arthur A., Harvey J., Sutton A.J. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M., Kirk, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, T., Harvey, J., … Sutton, A. (2005). Vulnerable groups and access to health care: A critical interpretive review. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization Research and Development (NCCSDO). Retrieved from 〈http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1210-025_V01.pdf〉.

- Flaskerud J.H., Winslow B.J. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nursing Research. 1998;47:69–78. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J., Chen L., Bhutta Z.A., Cohen J., Crisp N., Evans T.E., Zurayk H. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet. 2010;376:1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary T.L., Batts-Turner M., Yeh H.C., Hill-Briggs F., Bone L.R., Wang N.Y. The effects of a nurse case manager and a community health worker team on diabetic control, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations among urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(19):1788–1794. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R. Officiers de santé: The second-class doctors of nineteenth-century France. Medical History. 1978;22:25–43. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300031732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner S.D., Fouladi R.T. Improvement of rural children’s asthma self-management by lay health educators. Journal of School Health. 2008;78(9):506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst S.A. Vulnerability in research and health care; Describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics. 2008;22(4):191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Alim M., Kengne A.P., Jan S., Maulik P.K., Peiris D., Patel A.A. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries – A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, J., Oliver, S., Lorenc, T. (2008). Reflections on developing and using progress-plus. Equity Update. Retrieved from 〈http://www.cgh.uottawa.ca/assets/documents/Equity_Update_Vol2_Issue1.pdf〉.

- Kim K., Choi J.S., Choi E., Nieman C.L., Joo J.H., Lin F.R., Han H. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(4):E3–E28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.B., Kim M.T., Lee H.B., Nguyen T., Bone L.R., Levine D. Community health workers versus nurses as counselors or case managers in a self-help diabetes management program. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(6):1052–1058. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S., Munabi‐Babigumira S., Glenton C., Daniels K., Bosch‐Capblanch X., van Wyk B.E., Scheel I.B. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;3:CD004015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutes L.D., Cummings D.M., Littlewood K., Dinatale E., Hambidge B. A community health worker-delivered intervention in African American women with type 2 diabetes: A 12-month randomized trial. Obesity. 2017;25(8):1329–1335. doi: 10.1002/oby.21883. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier C.B., Aiken L.H. Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: A cross-country comparative study. European Journal of Public Health. 2016;26:927–934. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolius D., Bodenheimer T., Bennett H., Wong J., Ngo V., Padilla G., Thom D.H. Health coaching to improve hypertension treatment in a low-income, minority population. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(3):199–205. doi: 10.1370/afm.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M., Friel S., Bell R., Houweling T.A., Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M.A., Mosnaim G.S., Olson D., Swider S., Karavolos K., Rothschild S. Results from a community-based trial testing a community health worker asthma intervention in Puerto Rican youth in Chicago. Journal of Asthma. 2015;52(1):59–70. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.950426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K., Taylor L., Silverman J., Kiefer M., Hebert P., Lessler D. Randomized controlled trial of a community health worker self-management support intervention among low-income adults with diabetes, Seattle, Washington, 2010–2014. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2017;14:E15. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J., Tabish H., Welch V., Petticrew M., Pottie K., Clarke M., Tugwell P. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin A.M., Curran J.C., Fortune M., McArthur A., Mew E.J., Ritchie S.D., VanderBurgh D. Systematic review protocol: Health effects of training laypeople to deliver emergency care in underserviced populations. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010609. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin A.M., McArthur A., McDonald A., Mew E.J., Martiniuk A., Buchman D.Z., Kouyoumdjian F., Rachlis B., Strike C., Upshur R. Defining and measuring health equity effects in research on task shifting interventions in high-income countries: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021172. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmas W., Findley S.E., Mejia M., Batista M., Teresi J., Kong J. Results of the Northern Manhattan diabetes community outreach project: A randomized trial studying a community health worker intervention to improve diabetes care in hispanic adults. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):963–969. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLOS Medicine Editors Bringing clarity to the reporting of health equity. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9:e1001334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). . Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Retrieved from 〈http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?Doi=10.1.1.178.3100&rep=rep1&type=pdf〉.

- Povall S.L., Haigh F.A., Abrahams D., Scott-Samuel A. Health equity impact assessment. Health Promotion International. 2014;29(4):621–633. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relevo B.H. AHRQ; Bethesda, MD: 2011. Finding evidence for comparing medical interventions. Agency for healthcare research and quality. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild S.K., Martin M.A., Swider S.M., Lynas C.M.T., Janssen I., Avery E.F. Mexican American trial of community health workers: A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(8):1540–1548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301439. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M., Kaselitz E., Heisler M. The role of community health workers in diabetes: Update on current literature. Current Diabetes Reports. 2013;13(2):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0359-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidel V.W. The barefoot doctors of the People’s Republic of China. New England Journal of Medicine. 1972;286:1292–1300. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197206152862404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T.S., Funnell M., Sinco B., Piatt G., Palmisano G., Spencer M.S. Comparative effectiveness of peer leaders and community health workers in diabetes self-management support: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1525–1534. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch V., Petticrew M., Petkovic J., Moher D., Waters E., White H., PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016;70:68–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity in health. International Journal of Health Services. 1992;22:429–445. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank(n.d.). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Retrieved from 〈https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519〉.

- World Health Organization (2007). Task shifting: Rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2016, from 〈http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf〉.

- World Health Organization (2007). Task shifting to tackle health worker shortages. Retrieved 20 December 2018, from 〈https://www.who.int/healthsystems/task_shifting_booklet.pdf〉.

- World Medical Association . World Medical Association; Ferney-Voltaire, France: 2009. Resolution on task shifting from the medical profession. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material