Abstract

Analysis of the glycosylation of proteins is a challenge that requires orthogonal methods to achieve separation of the diverse glycoforms. A combination of reversed phase chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (RP-LC-MS/MS) is one of the most powerful tools for glycopeptide analysis. In this work, we developed and compared RP-LC and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) in nanoscale on a chip combined with MS/MS in order to separate glycoforms of two peptides obtained from the tryptic digest of hemopexin. We observed reduction of the retention time with decreasing polarity of glycans attached to the same peptide backbone in HILIC. The opposite effect was observed for RP-LC. The presence of sialic acids prolonged the retention of glycopeptides in both chromatographic modes. The nanoHILIC method provided higher selectivity based on the composition of glycan, compared to nanoRP- LC but a lower sensitivity. The nanoHILIC method was able to partially separate linkage isomers of fucose (core and outer arm) on bi-antennary glycoform of SWPAVGDCSSALR glycopeptide, which is beneficial in the elucidation of the structure of the fucosylated glycoforms.

Keywords: Glycoproteomics, Hemopexin, Hydrophilic interaction liquid, chromatography, LC–MS/MS, Reversed phase chromatography

1. Introduction

Analysis of glycoproteins presents substantial analytical challenges because of different ionization efficiency of glycopeptides compared to peptides, micro- and macro-heterogeneity of glycoproteins, and lower fragmentation recovery of peptide moieties of the glycopeptides in the CID tandem mass spectrometry. RP- LC is typically used for the analysis of protein digests but typically does not adequately resolve glycoforms of peptides [1]. RP-LC is driven mainly by physical-chemical properties of the peptide backbone with additional influence of the glycan moiety [2]. Several papers documented that the addition of neutral monosaccharide units to the glycan decreases retention of the glycopeptides [3–5] and that the addition of sialic acid increases retention [4,6]. HILIC is suitable for the analysis of polar analytes which are inadequately retained in RP-LC [1]. HILIC was successfully applied to glycopeptide enrichment [7,8], released glycan analysis [9,10], and separation of different glycoforms of peptides [11]. Although the directed analysis of glycoproteins provides site-specific information on glycans, the common approach to characterize glycans in HILIC is their enzymatic or chemical releas LC/MS analysis [12]. There are only few papers that describe nano scale HILIC separations of glycopeptides. Takegava et al. used ZIC-HILIC nano column for the separation of glycopeptides of erythropoietin and showed that the addition of N-acetyl-lactosamines increases the retention of glycopeptides under HILIC conditions while acetylation of sialic acids reduces retention [13]. Zauner et al. showed separation of N-and O-linked glycopeptides of asialofetuin and fetuin in HILIC on a nano amide column [14]. Wohlgemuth et al. used nano ZIC-HILIC to separate glycopeptides which co-eluted in RP-LC by their glycan composition and showed that efficient separation of the glycopeptides is achieved even in absence of any additives like salt or formic acid [15].

Alteration of glycosylation, in general, and enhanced fucosylation, in particular, have been suggested as a marker for monitoring of liver disease [16]. In our recent study, we described a glycosidase assisted LC-MS approach for the analysis of site specific fucosylated glycoforms. We documented quantitative changes of the site-specific linkage isoforms of fucosylated hemopexin in liver disease [16]. Although MS/MS is a powerful analytical tool of gly-coproteomics analysis, the chromatographic separations provide complementary information useful for the assignments of the site- specific glycoforms of proteins and for their quantification. The advantage of LC separation of isomeric glycopeptide structure represents direct analysis without the need for additional glycosidase treatment. NanoLC is essential to achieve sensitivity sufficient for the analysis of low amounts of target analytes in biological samples. In this study, two commercially available nano columns on a chip representing different stationary phases (C18 and HALO HILIC) were compared in order to demonstrate the features of these two chromatographic modes for the analysis of N-linked glycopeptides of hemopexin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Acetonitrile (ACN, LC-MS grade), acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (LC-MS grade), water (LC-MS grade), water with 0.1% formic acid (LC-MS grade), ammonium bicarbonate (purity ≥ 99%, LC-MS grade), and iodoacetamide (purity ≥99%) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dithiothreitol (ultrapure grade) and ammonium formate (LC-MS grade) were purchased from Thermo-Fischer Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts). Trypsin Gold for MS was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). α(2–3,6,8)- neuraminidase, a1–2 and a1–3,4 fucosidase with GlycoBuffer 1 (5 mM calcium chloride, 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5) were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Hemopexin from human plasma was supplied by Athens Research and Technology (Athens, Georgia,).

2.2. Sample preparation

Stock solution of hemopexin at a concentration of 10 μg/μL was prepared by dissolving the compound in water. 10 μL (100 μg) of hemopexin was diluted in 190 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and reduced with 5mM dithiothreitol at 60 °C for 60 min, alkylated with 15 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark, and residual iodoacetamide was quenched with 5 mM dithiothreitol. Trypsin digestion was carried out at 37 °C overnight, with an enzyme/protein ratio of 1:25 (w/w). Trypsin was subsequently inactivated for 10 min at 99 °C. An aliquot (100 μL) of the mixture was desialylated by the addition of 11 μL of GlycoBuffer 1 and 4 μL of neuraminidase overnight at 37 °C. Digests were desalted using solid phase extraction (SPE) on a Sep-Pak Vac C18 cartridge (Waters. Milford). Cartridges were first activated by rinsing 2 mL of 100% acetonitrile and 2 mL of 1% acetic acid. After loading step cartridges were rinsed with 1 mL of 1% acetic acid and glycopeptides were eluted with 0.5 mL of 65% acetonitrile. Eluates were evaporated using a vacuum concentrator (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) and reconstituted in a solution of 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile. 30 μL of the desialylated sample (30 μg) was evaporated and reconstituted in 82 μL of water, mixed with 10 μL of GlycoBuffer 1, and digested with 4 μL of each fucosidase overnight at 37°C. Sample was cleaned by SPE and reconstituted in a solution of 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile. Desialylated and sialylated samples were mixed, diluted to the final concentration of 0.02 μg/μL (Sample solvents were 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile for RP-LC and HILIC, respectively), centrifuged and transferred into a LC vial.

2.3. Instrumentation and the experimental conditions

The nanoLC experiments were performed using a Tempo Capillary LC equipped with cHiPLC-nanoflex (Eksigent, Framingham, MA) interfaced with 6500 Q-TRAP (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). The Analyst software (Sciex, Framingham, MA) was used for data acquisition. PeakView software (Sciex, Framingham, MA) was used to process LC-MS data. Several gradient programs were tested for separation of glycopeptides in the RP-LC and HILIC modes. The mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile (Solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in 100% acetonitrile (Solvent B). The flow rate of the mobile phase was maintained at 0.5 μL/min. The injection volume was 500 nL, samples were thermostated at 15 °C and column temperature was 30 °C. NanoRP-LC used cHiPLC column ChromXP C18-CL (3 μm, 75 μm x 150mm) from Eksigent (Framingham, MA) and the optimized gradient program [(min)/% B] was 0/3,45/35,48/95,50/3,60/3. HILIC used cHiPLC column HALO HILIC (2.7 μm, 75 μm × 150 mm) from Eksigent (Framingham, MA) and the optimized gradient program [(min)/% B] was 0/85,40/55,45/20, 46/85, 60/85. MS analysis was performed in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode. The SRM transitions of targeted glycopeptides with collision energies and declustering potentials are listed in Supporting Information Table S1. The ion source was set as follows: curtain gas, 25 for RP and 20 for HILIC; ion spray voltage, 2300V; ion source gas, 15 for RP and 11 for HILIC; interface heater temperature, 180°C; entrance potential, 10V; and collision exit potential, 13.

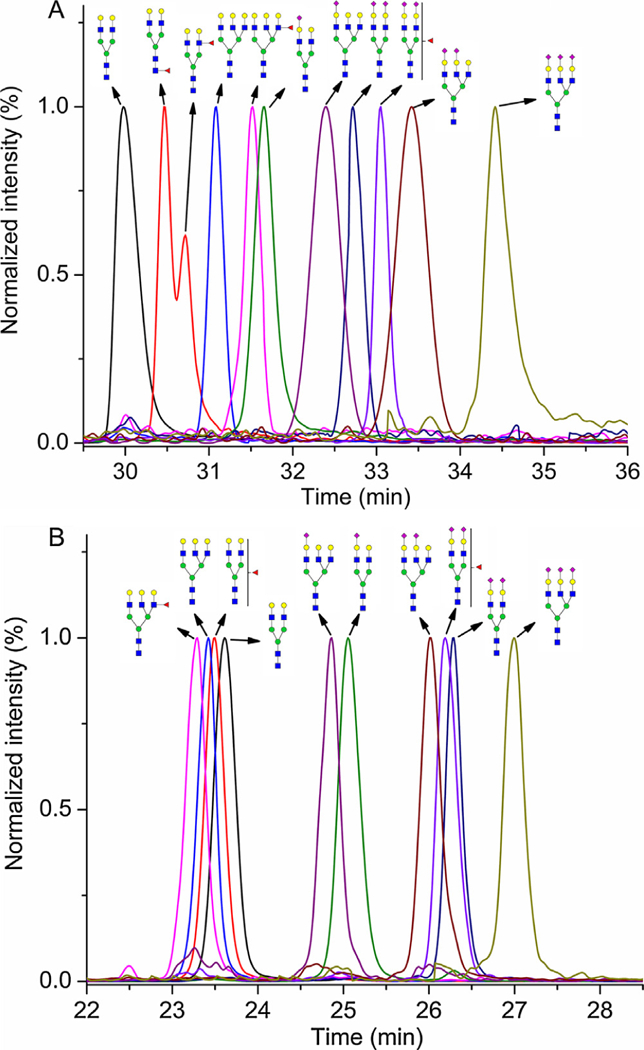

Glycan abbreviations used in this study were adopted from the NIBRT GlycoBase, where A2G2 means bi-antennary glycan terminated with two galactoses, A3G3 tri-antennary glycan terminated with three galactoses, F - fucose, and S - sialic acid. Gaussian smoothed SRM chromatograms were exported as text files to OriginPro 8.5.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) for the visualization presented in Fig. 1; each SRM chromatogram was normalized to the target glycopeptide and all target glycopeptide SRM chromatograms were overlaid and zoomed to the appropriate retention time window.

Fig. 1.

Overlay of the normalized SRM chromatograms of all the analyzed gly-coforms of the SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide of hemopexin under the optimized nanoHILIC (A) and nanoRP-LC (B) conditions. Symbols:  N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc);

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc);  , Galactose (Gal);

, Galactose (Gal);  , Fucose (Fuc);

, Fucose (Fuc);  , Mannose (Man);

, Mannose (Man);  , Sialic acid.

, Sialic acid.

3. Results and discussion

It has previously been described that different neutral oligosaccharide units of glycopeptides influence the retention time under the RP-LC [4,5] and HILIC [1,14,15] conditions. Fig. 1 shows the HILIC and the RP separations of N-glycoforms of the SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide under our optimized conditions. The elution order of gly-copeptides with neutral oligosaccharides is based on polarity of the molecule. In HILIC, A2G2 elutes as a first peak and the addition of oligosaccharide units makes the glycopeptide more hydrophilic and, therefore, extends its retention time. Similar trends were described in the analysis of different glycopeptides by nanoHlLlC [13–15]. In RP-LC, the elution order is the opposite and the addition of neutral oligosaccharide units causes a glycopeptide to elute earlier. HlLlC compare to RP-LC provided higher resolution of glycopeptides with neutral glycans; however, HILIC provided worse peak symmetry (except A3G3). For instance, asymmetric factor (As) of A2G2 in HILIC is 2.00 versus 1.02 in RP-LC (See Table 1). The presence of sialic acid on the glycan chain results in a substantial increase in the retention time of glycopeptides in RP-LC as well as in HlLlC. This effect is mostly due to the presence of active sites on the stationary phases, which interact with sialic acids more strongly [4,17]. RP-LC was able to separate (almost baseline separation Rs = 1.37) glycopeptides with neutral glycans (the last eluting peak - A2G2) from the glycopeptides with sialic acid (the first eluting peak - A3G3S1). Compared to RP-LC, poor resolution Rs = 0.15 was obtained between the last eluting glycopeptides with neutral glycan (A3G3F1) and the first eluting glycopeptides with sialic acid (A2G2S1) in HILIC. Peak symmetry of sialylated glycopeptides was similar for both chromatographic modes except the A3G3S3 glycopeptide, which showed strong tailing (As = 2.11) in HILIC (See Table 1). Similar retention behavior was also observed for the glycoforms of ALPQPQNVTSLLGCTH peptide (Supporting Information Fig. S1, and Table S2). The retention of studied hemopexin glycopeptides in the HILIC was driven mainly by the glycan composition and in the RP-LC mainly by the peptide backbone. Therefore the HlLlC was not able to separate completely the glycoforms of SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide, which eluted in the retention time window 29.5–35.5 min, from the glycoforms of ALPQPQNVTSLLGCTH peptide, which eluted in the retention time window 31.5–36.0 min. On the other hand the RP-LC showed full separation of SWPAVGD- CSSALR glycopeptides (the retention time window 22.5–27.5 min) from ALPQPQNVTSLLGCTH glycopeptides (the retention time window 29.5–34.0 min).

Table 1.

Chromatographic parameters: tR, retention time; EO, elution order; α, selectivity; Rs, resolution; As, assymetric factor; S/N, signal to noise. The parameters were determined for the nanoHlLIC and nanoRP separation of all the analyzed glycoforms of the SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide of hemopexin (SD - standard deviation for n=3; for mathematic formula of α, Rs, and As see Supporting Information).

| Analyte | nanoHILIC |

nanoRP-LC |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tR (SD) | EO | α | Rs | As | S/N (SD) | tR (SD) | EO | α | Rs | As | S/N (SD) | |

| SWPAVGNCSSALR | ||||||||||||

| A2G2 | 29.97 (0.14) | 1. | 1.016 | 0.60 | 2.00 | 3500 (180) | 23.61 (0.09) | 4. | 1.053 | 1.37 | 1.02 | 13540 (390) |

| A2G2F1 (core) | 30.46 (0.12) | 2. | 1.009 | 0.44 | – | 50 (7) | 23.52 (0.10) | 3. | 1.004 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 350 (20) |

| A2G2F1 (outer arm) | 30.72 (0.13) | 3. | 1.012 | 0.60 | – | 30 (3) | ||||||

| A3G3 | 31.08 (0.16) | 4. | 1.014 | 0.73 | 1.05 | 50 (6) | 23.42 (0.08) | 2. | 1.004 | 0.10 | 0.89 | 210 (18) |

| A3G3F1 | 31.52 (0.14) | 5. | 1.004 | 0.15 | 0.66 | 16(2) | 23.32 (0.09) | 1. | 1.004 | 0.12 | 0.94 | 65 (3) |

| A2G2S1 | 31.65 (0.09) | 6. | 1.023 | 0.68 | 1.36 | 95 (8) | 25.06 (0.12) | 6. | 1.038 | 1.04 | 1.30 | 415 (28) |

| A3G3S1 | 32.39 (0.11) | 7. | 1.010 | 0.37 | 1.06 | 18 (2) | 24.86 (0.13) | 5. | 1.008 | 0.21 | 1.05 | 72 (6) |

| A2G2S2 | 32.72 (0.17) | 8. | 1.010 | 0.49 | 1.26 | 17 (1) | 26.30 (0.11) | 9. | 1.027 | 0.84 | 1.26 | 70 (5) |

| A2G2S2F1 | 33.05 (0.16) | 9. | 1.011 | 0.35 | 1.32 | 19(2) | 26.19 (0.09) | 8. | 1.004 | 0.14 | 1.50 | 71 (6) |

| A3G3S2 | 33.41 (0.19) | 10. | 1.030 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 13(1) | 26.02 (0.10) | 7. | 1.007 | 0.21 | 1.43 | 46(3) |

| A3G3S3 | 34.41 (0.18) | 11. | – | – | 2.11 | 8 (1) | 27.01 (0.14) | 10. | – | – | 1.08 | 29 (2) |

The partially resolved peaks (Rs = 0.44) in the HILIC for A2G2F1 glycoform (See Fig. 1A) with the same SRM transition suggests that these peaks result from chromatographic separation of linkage isoforms. The location of fucosylation sites was studied by fucosidase digestion. We used treatment of the desialylated tryptic hemopexin sample with α1–2 and α1–3, 4 fucosidase, which leave intact the core fucose linked to GlcNAc through α1–6 linkage. The analysis of the sample showed that the minor fucosylated bi-antennary peak disappeared. By comparing ratio of retention times (A2G2/targeted peak) we found that the first eluting peak corresponded to the core fucosylated glycopeptide and the second to the one with outer arm fucose (Supporting Information Fig. S2.). It was also revealed that major part of the A3G3F1 peak contains outer arm linked fucose. High column temperature and presence of buffer as solvent A were tested to obtain better separation of core and outer arm fucosylated glycoforms of the A2G2F1 glycopeptide. lncreased retention times of the glycopeptides with worse resolution of core and outer arm glycoforms of A2G2F1 were obtained at 60 °C compared to 30°C (Supporting Information Fig. S3). The retention mechanism of HlLlC is a combination of partitioning and adsorption processes. Increased retention times can be related to changes of the amount of water adsorbed onto the stationary phase [18]. However, adsorption processes may play an important role in resolution of core and outer arm glycoforms of A2G2F1 at 30 °C and the influence of partitioning may decrease resolution at increasing column temperature. More detailed studies are needed for a better understanding of the impact of column temperature on chromatographic behavior of glycopeptides in HlLlC. 20 mM ammonium formate pH 4.00 as solvent A showed increased retention times of the glycopeptides with coelution of the core and outer arm fucosylated glycoforms in one broad peak. 50 mM ammonium formate pH 4.00 as solvent A prolonged retention times of the glycopeptides without improvement in the separation (Supporting Information Fig. S4.). Presumably, high concentration of ACN in the mobile phase causes salt to partition preferentially into the water-rich layer on the stationary phase, which would increase its volume, potentially leading to stronger retention of glycopeptides and worse resolution of core and outer arm glycoforms.

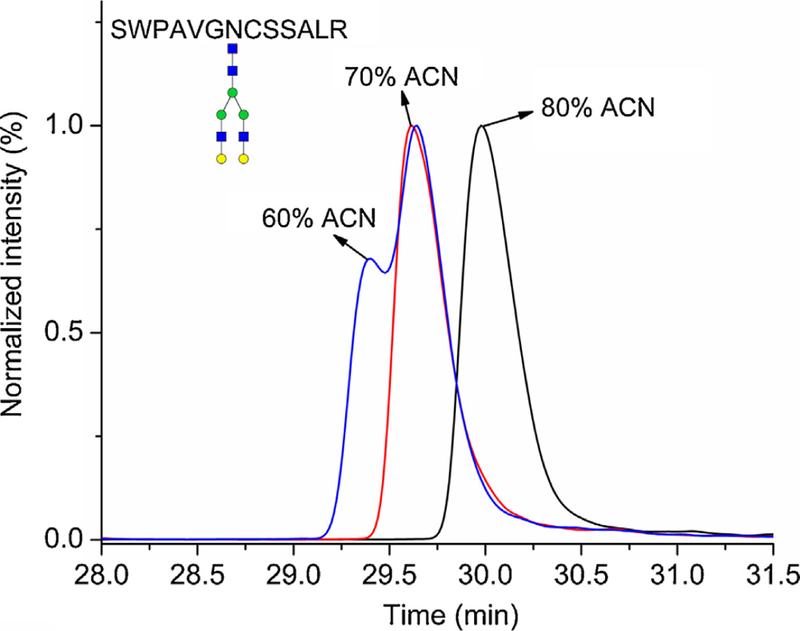

Table 1 shows rather low sensitivity (signal to noise; S/N) of the studied glycopeptides in HILIC compared to RP-LC. It might be caused by different ionization efficiency of glycopeptides in dif-ferent composition of the mobile phase, different matrix effects, different chromatographic efficiency or a solubility problem of glycopeptides in high ACN concentration in the sample solvent; we did not study which of these parameters has the major influence. Zauner et al. explained rather low intensities of N-glycopeptides compared to O-glycopeptides by lower solubility [14]. Although higher water content in sample solvent can help to increase the solubility of glycopeptides, it can have an effect on HlLlC chromatography. Fig. 2. shows the influence of ACN content in the sample solvent on the peak shape of the A2G2 glycoform in HILIC. Reduction of ACN in sample solvent from 80% to 70% caused retention time shift of all glycoforms and co-elution of the A2G2F1 glycoforms with the core or outer arm linkage. Reduction to 60% caused peak splitting. Similar behavior was observed for all the glycopeptides and further optimization of these separation conditions is essential.

Fig. 2.

The influence of the ACN content in the sample solvent on chromatographic behavior of the A2G2 glycoform of the SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide of hemopexin analyzed underthe optimized nanoHlLIC conditions. Symbols - see Fig. 1.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we optimized and compared nanoRP-LC and nanoHlLIC separations of the glycopeptides of hemopexin on a chip. We showed the influence of composition of the glycans on the retention behavior of studied glycopeptides in RP-LC and HILIC modes. The influence of different chromatographic conditions on retention and separation of studied glycopeptides in nanoHlLlC, especially on the core and outer arm fucose of A2G2 glycoform was shown. The results offer an opportunity for the adjustment of the nanoHlLlC separations by tuning chromatographic conditions for an optimal retention and separation of specific glycopeptides.A drawback of our HlLlC method is a lower sensitivity compared to the RP-LC method and high susceptibility of the separations to the sample solvent composition. The HlLlC method showed the potential to separate fucose linkage isomers (core and outer arm) on A2G2 glycoform of the SWPAVGDCSSALR peptide, which would be beneficial in direct analysis of site-specific linkage isoforms of fucosylated hemopexin in liver disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the National Institutes of Health Grants UO1 CA168926, UO1 CA171146, and RO1 CA135069 (to R.G.) and CCSG Grant P30 CA51008 (to Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center supporting the Proteomics and Metabolomics Shared Resource).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jxhroma.2017.08.066

References

- [1].Gilar M, Yu YQ, Ahn J, Xie HW, Han HH, Ying WT, Qian XH, Characterization of glycoprotein digests with hydrophilic interaction chromatography and mass spectrometry, Anal. Biochem. 417 (2011) 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bruderer R, Bernhardt OM, Gandhi T, Reiter L, High-precision iRT prediction in the targeted analysis of data-independent acquisition and its impact on identification and quantitation, Proteomics 16 (2016) 2246–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sanda M, Zhang LH, Edwards NJ, Goldman R, Site-specific analysis of changes in the glycosylation of proteins in liver cirrhosis using data-independent workflow with soft fragmentation, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409(2017)619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ozohanics O, Turiak L, Puerta A, Vekey K, Drahos L, High-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry methodology for analyzing site-specific N-glycosylation patterns,J. Chromatogr. A 1259 (2012) 200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kozlik P, Goldman R, Sanda M, Study of structure-dependent chromatographic behavior of glycopeptides using reversed phase nanoLC, Electrophoresis (2017), 10.1002/elps.201600547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Medzihradszky KF, Kaasik K, Chalkley RJ, Characterizing sialic acid variants at the glycopeptide level, Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 3064–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alagesan K, Khilji SK, Kolarich D, lt is all about the solvent: on the importance of the mobile phase for ZIC-HILIC glycopeptide enrichment, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409 (2017) 529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zacharias LG, Hartmann AK, Song EH, Zhao JF, Zhu R, Mirzaei P, Mechref Y, HILIC and ERLIC Enrichment of Glycopeptides Derived from Breast and BrainCancerCells,J. Proteome Res. 15 (2016)3624–3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mancera-Arteu M, Gimenez E, Barbosa J, Sanz-Nebot V, ldentification and characterization ofisomeric N-glycans ofhuman alfa-acid-glycoprotein by stable isotope labelling and ZlC-HlLlC-MS in combination with exoglycosidase digestion, Anal. Chim. Acta 940 (2016) 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang YW,Zhu JH, Yin HD,Marrero J, Zhang XX, Lubman DM, ESl-LC-MS method for haptoglobin fucosylation analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma and livercirrhosis,J. Proteome Res. 14 (2015) 5388–5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang Y, Nie Y, Boyes B, Orlando R, Resolving isomeric glycopeptide glycoforms with hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HlLlC), J. Biomol. Tech. 27(2016) 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zauner G, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M, Recent advances in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HlLlC) for structural glycomics, Electrophoresis 32 (2011) 3456–3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Takegawa Y, Ito H, Keira T, Deguchi K, Nakagawa H, Nishimura S.l., Profiling of N- and O-glycopeptides of erythropoietin by capillary zwitterionic type of hydrophilic interaction chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, J. Sep. Sci. 31 (2008) 1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zauner G, Koeleman CAM, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M, Protein glycosylation analysis by HILIC-LC-MS of proteinase K-generated N- and O-glycopeptides,J. Sep. Sci. 33 (2010) 903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wohlgemuth J, Karas M, Jiang W, Hendriks R, Andrecht S, Enhanced glyco-profiling by specific glycopeptide enrichment and complementary monolithic nano-LC (ZlC-HlLlC/RP18e)/ESl-MS analysis,J. Sep. Sci. 33 (2010) 880–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu XE, Desmyter L, Gao CF, Laroy W, Dewaele S, Vanhooren V, Wang L, Zhuang H, Callewaert N, Libert C, Contreras R, Chen C, N-glycomic changes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with liver cirrhosis induced by hepatitis B virus, Hepatology 46(2007) 1426–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Benicky J, Sanda M, Pompach P,Wu J, Goldman R, Quantification of fucosylated hemopexin and complement factor H in plasma of patients with liver disease, Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 10716–10723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vreeker GCM, Wuhrer M, Reversed-phase separation methods forglycan analysis, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409 (2017) 359–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dong LL, Huang JX, Effect of temperature on the chromatographic behavior of epirubicin and its analogues on high purity silica using reversed-phase solvents, Chromatographia 65 (2007) 519–526. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.