Abstract

Purpose

Adolescents’ increased use of social networking sites (SNS) coincides with a developmental period of heightened risk for alcohol use initiation. However, little is known regarding associations between adolescents’ SNS use and drinking initiation, nor the mechanisms of this association. This study examined longitudinal associations among adolescents’ exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS postings, alcohol-favorable peer injunctive norms, and initiation of drinking behaviors.

Methods

Participants were 658 high-school students who reported on posting of alcohol-related SNS content by self and friends, alcohol-related injunctive norms, and other developmental risk factors for alcohol use at two time points, one year apart. Participants also reported on initiation of three drinking behaviors: consuming a full drink, becoming drunk, and heavy episodic drinking (three or more drinks per occasion). Probit regression analyses were used to predict initiation of drinking behaviors from exposure to alcohol-related SNS content. Path analyses examined mediation of this association by peer injunctive norms.

Results

Exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content predicted adolescents’ initiation of drinking and heavy episodic drinking one year later, controlling for demographic and known developmental risk factors for alcohol use (i.e., parental monitoring, peer orientation). In addition, alcohol-favorable peer injunctive norms statistically mediated the relationship between alcohol-related SNS exposure and each drinking milestone.

Conclusions

Results suggest that social media plays a unique role in contributing to peer influence processes surrounding alcohol use, and highlight the need for future investigative and prevention efforts to account for adolescents’ changing social environments.

Keywords: Adolescent, Social Media, Alcohol, Peer Influence, Drinking, Social Networking Sites, Peer Norms, Internet, Initiation, Onset

Adolescent’s use of social networking sites (SNS) has increased drastically within the last decade, with 89% of adolescents using at least one SNS in 2015 [1]. Such sites allow adolescents to create public profiles and connect with networks of “friends” through text, photos, and video. Adolescents’ interactions via SNS may provide an important context for the development of risk behaviors [2], particularly as adolescents share and view peer-generated content about alcohol use [3]. Adolescence is the highest risk period for initiation of drinking [4] and early-onset alcohol use prospectively predicts neurological, social, cognitive, and mental health impairments, as well as increased risk for problematic substance use [5,6]. Despite coinciding increases in risky alcohol-related behaviors and use of SNS where youth may share alcohol-related content, little is known regarding associations between adolescents’ SNS use and initiation of alcohol use.

SNS have become an essential aspect of adolescents’ social lives, with traditional peer interactions often occurring within such environments [1]. Using SNS, adolescents can engage with their peers in a variety of alcohol-related activities. Prior research indicates that individuals may use SNS to post photos or text that explicitly reference their own drinking behaviors, as well as to display more implicit references to alcohol, such as those contained in song lyrics, websites, and music videos [7–9]. On SNS, adolescents may view peers’ postings related to alcohol [10] and the feedback that such postings receive from others. Research suggests that these portrayals of alcohol use are largely positive in nature [7,8]. There are many theoretical reasons to suspect that these alcohol-related aspects of SNS use have implications for adolescents’ drinking behaviors.

Behavioral theories such as social cognitive theory [11] and the theory of planned behavior [12] emphasize the ways in which individuals’ behaviors are shaped via observation of others and the development of subjective norms. Such theories have informed models of both media and peer influences on risk behavior. For example, adolescents may adopt behaviors that are modeled via mass media, depending on their beliefs and expectations regarding those behaviors [11]. Indeed, portrayals of alcohol use via media channels have been shown to influence adolescents’ likelihood of consuming alcohol, particularly when adolescents perceive those portrayals to be desirable, realistic, and similar to them [13]. Furthermore, peer substance use has been shown to be among the strongest correlates of adolescents’ drinking initiation and escalation [4], with peer alcohol use longitudinally predicting early-onset drinking behaviors [14] and progression to heavy drinking [15]. Social media provides both the vast quantities of digitally mediated information characteristic of mass media and the personalized, reciprocal engagement characteristic of traditional peer interactions. It may thus represent a synthesis of peer and media influences on adolescents’ behavior.

These theories suggest that peer and media influences contribute to adolescents’ perceived social norms around drinking, which impact their own drinking behaviors. Descriptive norms, or beliefs about the extent to which one’s peers are drinking alcohol, and injunctive norms, or beliefs about peers’ approval or disapproval of drinking alcohol, have both been shown to influence drinking behaviors [16]. On SNS, experimental evidence suggests that youth who view Facebook profiles portraying alcohol use report greater descriptive norms of alcohol use and willingness to drink [17]. The unique context of social media may also influence adolescents’ injunctive norms around peers’ alcohol use. Some adolescents may engage in selective self-presentation on these platforms, sharing experiences with alcohol and engaging with alcohol-related messages as a means of portraying an “intoxigenic social identity,” which supports drinking as normative among youth [9] and emphasizes positive, rather than negative, aspects of alcohol use [7]. These adolescents will likely be viewed as approving of alcohol use, perhaps contributing to misperceptions of peers’ beliefs about alcohol [18]. Furthermore, as adolescents’ SNS often represent large networks of peers, accessible any time, anywhere, [1] an incredible volume of alcohol-related social information may be accessible and the posts of just a few alcohol-using peers can have wide influence. Thus, adolescents exposed to alcohol-related SNS activity may be uniquely positioned to develop biased perceptions of injunctive norms around alcohol, and may be at risk for early initiation of alcohol use and progression to problematic drinking behaviors.

Despite theoretical reasons to suggest that exposure to alcohol-related SNS use may be associated with adolescents’ alcohol use, little empirical work has examined these associations longitudinally, with existing work primarily cross-sectional and/or limited to college student samples. The lack of research is problematic as adolescence is a critical time period for the development of alcohol use beliefs [19] and self-schemas involving future oriented self-cognitions related to alcohol [20]. Initial descriptive work suggests that adolescents’ exposure to alcohol-related postings on SNS is frequent. According to a 2012 national survey, 45% of adolescents reported seeing pictures posted of peers drinking, passed out, or using drugs, [10].

Only a few studies have examined associations between exposure to alcohol-related SNS activity and alcohol use and norms in teenagers, and these largely support a positive association. Cross-sectional findings indicate that adolescents reporting more frequent exposure to SNS alcohol content, including other teens getting drunk or passed out, report more alcohol-favorable injunctive norms and greater likelihood of having used alcohol [10,21]. A longitudinal study of tenth graders found that those with more close friends who posted pictures of “partying or drinking alcohol” on SNS were at increased risk of drinking alcohol six-months later [22], but a study from the same authors using stochastic actor-oriented models found no direct association between exposure to friends’ postings and subsequent alcohol use [23]. Finally, one study of seventh and eighth-grade students demonstrated that media exposure to alcohol or drugs, including SNS content, was both predictive of greater alcohol use one-year later and predicted by prior-year alcohol use [24].

Building on this literature, the current study offers a unique opportunity to examine adolescents’ exposure to alcohol-related SNS content and development of favorable injunctive norms using longitudinal data from a sample of secondary school students. In addition, by following a sample of initially alcohol-abstinent adolescents, this study allows for the prospective prediction of initiation of alcohol use behaviors. Thus, the primary goal of this study was to conduct a prospective longitudinal investigation of the effects of exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS postings on adolescent initiation of drinking milestones, controlling for known developmental risk factors for alcohol use (e.g., parental monitoring, peer orientation). In addition, the study sought to examine whether injunctive norms mediate the longitudinal association between exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content and initiation of drinking milestones.

Methods

Participants

Participants were taken from a ongoing prospective study on alcohol initiation and progression among adolescents [25,26]. Participants were 59.0% female and 21.3% non-White (4.6% Black, 3.2% Asian, 1.5% American Indian, 5.5% mixed race; 6.6% other) and 10.6% Hispanic; 36.1% of students received free or reduced price school lunch. Procedures were approved by the university IRB.

Procedure

Students were recruited from six Rhode Island middle schools in rural, suburban, and urban areas. Data were collected from 1,023 sixth, seventh, and eighth graders in five school cohorts (enrolled at six-month intervals). Study information was disseminated through schools; interested participants with parental consent for study participation were scheduled to attend a two-hour in-person baseline orientation session. Thereafter, participants completed a series of web surveys initially administered semi-annually and then quarterly (change in design due to new funding; 802 of the 1,023 were re-enrolled at this point). Data on SNS usage was collected on two occasions separated by one year, which were administered between the fourth and sixth years of the study, depending on school cohort. Thus, present study participants were between grades 9 and 12 at the first administration (“Time 1” or T1; MT1Age = 15.8) and between grades 10 and 12 at the second administration one year later (“Time 2” or T2).

A total of 791 participants completed the T1 assessment and 602 participants (76.1% of 791) completed T2; attrition from T1 to T2 was due to participants graduating from high school (ending study participation; n=137, 17.3% of 791) or otherwise failing to complete the survey (n=52; 6.6% of 791). Those who did not complete T2 were more likely to be older, t(304.28)= −18.95, p<.001, white, χ2=10.33, p<.01, have used a SNS, χ2=4.50, p=.034, and engaged in drinking behaviors, χ2=28.64, p<.001. There were no differences by sex or SNS alcohol content posting or exposure. The current study sample was limited to participants who reported using a SNS in the past, resulting in a final sample size of 658 (83.2% of the 791), inclusive of participants missing data on T2 outcomes and/or SNS content variables. For each drinking milestone, samples were limited to those who had not engaged in that drinking milestone by T1 in order to establish directionality. Of the 658, a total of 495 (75.2%) reported having never engaged in drinking by T1, 584 (88.8%) reported having never become drunk by T1, and 573 (87.1%) reported having never engaged in heavy episodic drinking by T1.

Measures

Exposure to Friends’ SNS Alcohol Content

To assess whether participants had been exposed to alcohol-related content posted by friends on SNS, two binary items asked participants whether a friend had ever: 1) posted a picture of themselves with alcohol, or 2) posted a status, picture, or link about drinking alcohol. Items were combined, with endorsement of either item coded as “1” and endorsement of neither as “0,” to create a binary indicator of exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS postings.

SNS Alcohol Content Posted by Self

Five items asked whether participants themselves had ever posted alcohol-related content on a SNS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Means, frequencies, and bivariate correlations among study variables

| M (SD) | % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Extreme Peer Orientation |

2.11 (1.07) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| 2. T1 Parental Monitoring | 3.76 (0.98) | -- | −.33*** | -- | |||||||

| 3. T1 Peer Injunctive Norms | 4.19 (2.06) | -- | .24*** | −.28*** | -- | ||||||

| 4. T2 Peer Injunctive Norms | 4.44 (2.14) | -- | .23*** | −.25*** | .47*** | -- | |||||

| 5. T1 Average Daily Time on Facebook |

2.56 (1.91) | -- | .05 | −.19*** | .05 | .00 | -- | ||||

| 6. T1 Exposure to Friends’ SNS Alcohol Content |

-- | 20.85 | .15*** | −.11** | .26*** | .24*** | .03 | -- | |||

| 7. T1 Self Posting of SNS Alcohol Content |

-- | 7.52 | .25*** | −.25*** | .16*** | .13** | .14** | .32*** | -- | ||

| 8. T2 Initiation of Drinking | -- | 10.54 | .03 | −.02 | .07† | .14*** | −.03 | .08† | −.04 | -- | |

| 9. T2 Initiation of Becoming Drunk |

-- | 7.20 | .06 | −.07* | .16*** | .24*** | −.04 | .08* | −.02 | .53*** | -- |

| 10. T2 Initiation of HED | -- | 4.88 | .07† | −.06 | .15*** | .27*** | −.02 | .13** | .01 | .41*** | .52*** |

Note: For associations between binary variables, phi coefficients are reported. “Initiation” refers to engaging in each drinking behavior for the first time between T1 and T2.

p < .07;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Time on Facebook

One item assed the average time that participants spent on Facebook per day rated on a 7-point scale (1=less than 10 minutes, 7=4 or more hours).

Alcohol use Outcomes

At each wave of the larger study, participants reported whether they had ever consumed a full drink of alcohol, had ever been drunk, and had ever engaged in heavy episodic drinking (HED; defined for adolescents as consuming three or more drinks per occasion). T1 and T2 alcohol involvement were determined based on whether there was any report of a given drinking outcome at any of the intermediate assessments up to that wave. Binary variables were created for each drinking outcome indicating event occurrence or not.

Extreme Peer Orientation

The 4-item Extreme Peer Orientation Scale [27] assessed adolescents’ willingness to conform to problematic peer behavior to gain acceptance to one’s peer group (e.g., “How much does the amount of time you spend with your friends keep you from doing the things you ought to do?”). A mean was taken across items assessed on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater peer orientation (α=.75).

Parental Monitoring

The 9-item Parental Monitoring Scale [28] assessed the extent to which participants’ parents/guardians monitored adolescents’ daily activities (e.g., "Do your parents or guardians know what you do during your free time?"). Items were rated on a 5-point scale, from 1=No/never (0%) to 5=Yes/Always (100%). A mean score was computed, with higher scores indicating greater parental monitoring (α=.93).

Peer Injunctive Norms

Two items from a measure of passive social influence [29] assessed perceived peer injunctive norms regarding alcohol use, with language adapted for age-appropriateness. Items were: “How do most of your close friends feel about kids your age drinking alcohol?” and “How do most of your close friends feel about kids your age getting drunk?” Response options ranged from 1=Strongly Disapprove to 5=Strongly Approve. A sum of items was taken, with higher values indicating more alcohol-favorable norms (α=.95).

Data Analytic Plan

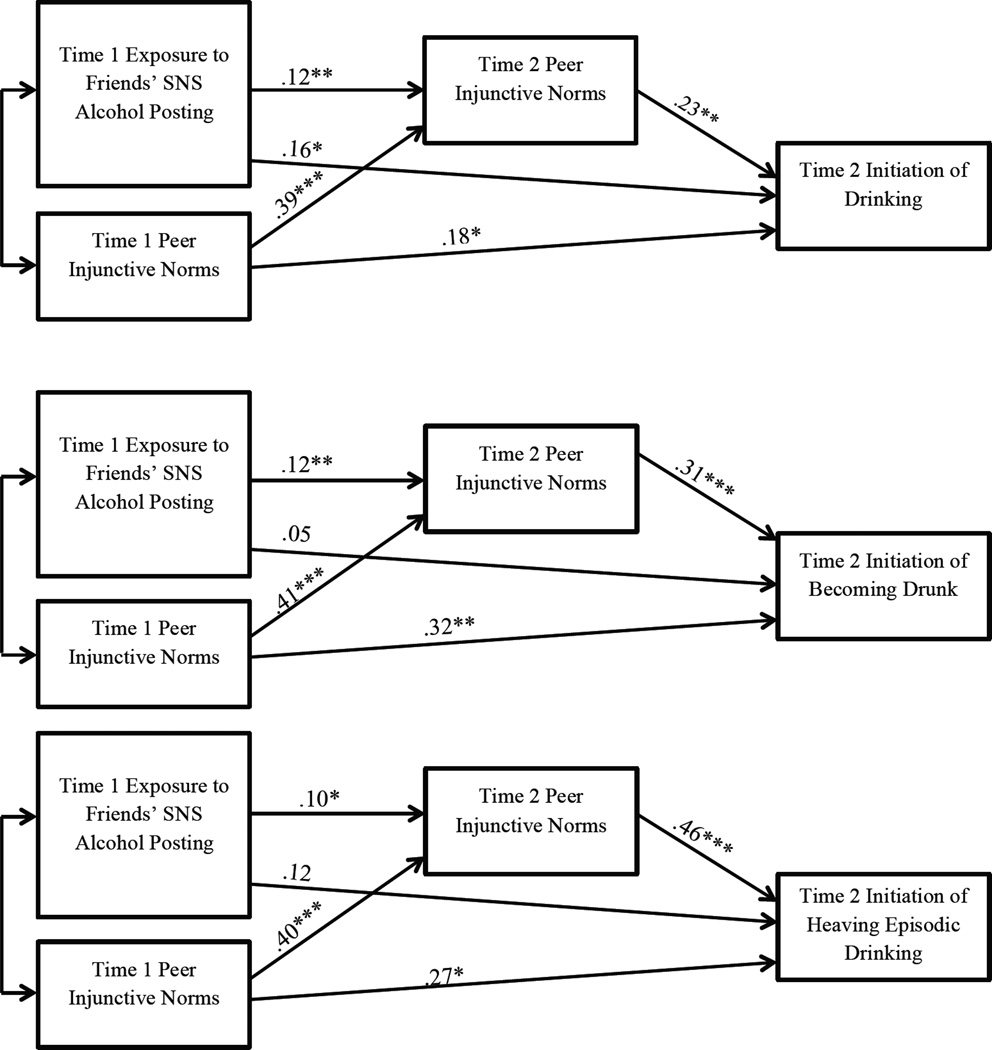

To examine whether exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content predicted initiation of drinking milestones one-year later, multivariate probit regression analyses were run to predict each of the three T2 drinking outcomes. Data met all assumptions necessary for probit regression, which was utilized to ensure adequate modeling of error variances and conservative tests of hypotheses. Then, to examine injunctive norms as a mediator of the association between exposure to friends’ SNS alcohol content and initiation of drinking milestones, path analyses were conducted separately for each of the three alcohol outcome variables (see Figure 1). Indirect effects were estimated from T1 exposure to friends’ SNS posting to T2 drinking milestones via T2 injunctive norms. Robust weighted least squares estimation (in MPlus 7.0) was used to account for categorical variables and to handle missing data on T2 outcomes and/or SNS alcohol content; sensitivity analyses using list-wise deletion did not substantively change model results. All models included relevant control variables regressed on outcomes and correlated with one another (sex, age, race, and time on Facebook).

Figure 1.

Path models testing mediation of pathway from exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS posting to initiation of drinking milestones (drinking, becoming drunk, and heavy episodic drinking) by peer injunctive norms. Models also include relevant control variables (sex, age, race, and time on Facebook) regressed on drinking outcomes (not shown here). Standardized effects reported.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Results

Descriptives

Means, frequencies, and correlations among study variables can be found in Table 1, with results describing participants' SNS use in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rates of Adolescent Endorsement of Social Networking Site Behaviors at Time 1

| Social Networking Site Behavior | Rate of Endorsement | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Any Exposure to Alcohol-Related Content Posted by Friends on SNS | 122 | 20.7% |

| Friend has posted status, picture, or link about alcohol | 85 | 14.5% |

| Friend has posted pictures of themselves with alcohol | 110 | 18.7% |

| Any Alcohol-Related Content Posted by Self on SNS | 44 | 7.5% |

| Have posted status, picture, or link about alcohol | 38 | 6.5% |

| Have posted picture of self with alcohol | 26 | 4.4% |

| Have tagged friends in photos with alcohol | 18 | 3.1% |

| Have posted picture of self passed out or vomiting as result of alcohol | 7 | 1.2% |

| Have posted picture of friend passed out or vomiting as result of alcohol | 6 | 1.0% |

Note: A total of 587 participants (out of the total sample of 658) completed items related to SNS alcohol content. Percentages reported here are out of 587.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Hypothesis Testing

Probit Models

Results of probit regression analyses (Table 3) indicated that adolescents who reported having been exposed to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content at T1 were significantly more likely to have had their first drink by T2 and to have engaged in their first episode of HED by T2, above and beyond the effects of extreme peer orientation, parental monitoring, injunctive norms, and demographic factors at T1. In addition, more alcoholfavorable peer injunctive norms at T1 were associated with greater likelihood of engagement in each of the three drinking milestones by T2. Exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content was not associated with an increased likelihood of adolescents becoming drunk by T2.

Table 3.

Probit Regression Analyses Predicting Adolescent Initiation of Drinking Behaviors

| First Drink by T2 | First Time Drunk by T2 | First HED by T2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | OR | β (SE) | OR | β (SE) | OR | |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Sex | −0.12 (0.09) | 0.67 | −0.15 (0.08) | 0.60 | −0.17 (0.10) | 0.50 |

| Race | 0.22 (0.10)* | 2.84 | 0.20 (0.09)* | 2.63 | 0.17 (0.10) | 2.36 |

| Age | 0.10 (0.09) | 1.19 | −0.01 (0.09) | 0.98 | −0.14 (0.11) | 0.78 |

| Daily Time on Facebook | −0.03 (0.10) | 0.98 | −0.12 (0.09) | 0.90 | −0.09 (0.10) | 0.92 |

| Time 1 Predictors | ||||||

| Exposure to Friends' SNS Alcohol Content | 0.18 (0.07)* | 2.36 | 0.08 (0.08) | 1.41 | 0.16 (0.07)* | 2.03 |

| Peer Injunctive Norms | 0.24 (0.08)** | 1.24 | 0.42 (0.09)*** | 1.45 | 0.43 (0.10)*** | 1.46 |

| Extreme Peer Orientation | −0.02 (0.08) | 0.97 | −0.03 (0.09) | 0.95 | −0.03 (0.09) | 1.01 |

| Parental Monitoring | −0.16 (0.09) | 0.74 | −0.18 (0.08)* | 0.71 | −0.15 (0.09) | 0.76 |

Note: OR = "Odds Ratio”; For Sex, female = 0 and male =1; for Race, non-white = 0 and white = 1. Odds ratios calculated by multiplying raw probit parameters by 1.7 (converting to logit parameters) and exponentiating the resulting coefficients.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Mediation Models

In path analyses, significant direct effects indicated that T1 exposure to friends’ SNS alcohol content was associated with more alcohol-favorable T2 injunctive norms, and that more alcohol-favorable peer norms at T1 and T2 were associated with initiation of drinking behaviors at T2 (Figure 1). Paths from T1 exposure to friends’ SNS posting to T2 initiation of becoming drunk and HED were not significant, indicating no direct effects on these drinking milestones in mediation models. Indirect effects were estimated (Table 4). Results indicated that peer injunctive norms were a significant mediator of the relationship between exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS postings and initiation of drinking, becoming drunk, and HED at T2. Indirect effects comprising a percentage of the total effects of exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content were 14.6% for drinking, 41.7% for becoming drunk, and 28.0% for HED.

Table 4.

Total and Indirect Effects of Exposure to Friends’ SNS Alcohol Content on Drinking Milestones

| Estimate | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2 Initiation of Drinking | |||

| Total Effect | 0.19 | 0.07 | .007 |

| Indirect Effect via T2 Peer Injunctive Norms | 0.03 | 0.01 | .046 |

| Percent Mediated | 14.6% | ||

| T2 Initiation of Becoming Drunk | |||

| Total Effect | 0.08 | 0.08 | .272 |

| Indirect Effect via T2 Peer Injunctive Norms | 0.04 | 0.02 | .028 |

| Percent Mediated | 41.7% | ||

| T2 Initiation of First Heavy Episodic Drinking | |||

| Total Effect | 0.15 | 0.07 | .017 |

| Indirect Effect via T2 Peer Injunctive Norms | 0.05 | 0.02 | .037 |

| Percent Mediated | 28.0% |

Note: Models were estimated using robust weighted least squares estimation. Standardized effects reported. Percent Mediated refers to the percent of the total effect that was mediated by T2 Peer Injunctive Norms

Discussion

This study fills a key gap in the literature by prospectively examining adolescents’ initiation of drinking behaviors following exposure to friends’ alcohol-related content on SNS and testing one potential mechanism, changing peer injunctive norms, by which this may occur. Results suggest that adolescents exposed to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content reported stronger alcohol-favorable peer injunctive norms and were more likely to initiate drinking. Two key findings highlight the unique role that social media may play in contributing to peer influence processes surrounding youth alcohol use initiation and progression.

First, exposure to peers’ alcohol-related SNS content predicted adolescent’s initiation of drinking one year later. Findings remained significant controlling for known developmental risk factors for initiation of alcohol use, suggesting that exposure to such SNS content may have an important impact on drinking behaviors among youth. SNS, where adolescents can access an immense volume of mediated content in the virtual presence of peers, may combine elements of traditional mass media and offline peer environments. As such, it may represent a synthesis of peer and media influences, both of which have critical implications for adolescents’ alcohol consumption [4,30].

Social cognitive theory suggests that adolescents’ behaviors are shaped by observation and cognitive interpretations of the behaviors of peer and media models [11]. Two mechanisms that may account for this effect are described by the Message Interpretation Process (MIP) model and Deviancy Training model. The MIP model of media influence [31] suggests that adolescents’ decision-making around alcohol is influenced by positive affect induced by a media message’s perceived desirability and similarity to adolescents’ own experiences [13]. Within SNS, where adolescents encounter alcohol references displayed by their own close friends and peers, these messages are likely seen as highly personally relevant, desirable, and realistic. Deviancy training models, drawn from the peer influence literature, suggest that adolescents reinforce one another’s delinquency through positive communication about antisocial behaviors [32]. Large, public SNS audiences may amplify this positive reinforcement, and associated social learning, gained by alcohol-related posting. These mechanisms represent two areas for future research to examine the interface of peer interaction and media-based influences on adolescent risk behaviors.

A second key finding is that adolescents’ beliefs that peers approve of alcohol use may act as one mechanism by which exposure to friends’ alcohol-related SNS content leads to initiation of drinking behaviors. The theory of planned behavior [12] suggests that subjective norms have a tangible impact on behavior, and the specific role of injunctive norms in increasing the likelihood of adolescents’ alcohol use is well-documented [33]. SNS represents a particularly potent context for the development of such norms. Existing models suggest that social norms are developed through observation of behavior and peer communication [34]. On SNS, adolescents can observe the behaviors and communications of a wide range of their peers, by viewing posted photos, text, and links. However, some adolescents purposefully post positive portrayals of alcohol use, approval, and enjoyment on SNS [7,9] in order to present a desired identity and gain social acceptance [35]. Given that the SNS environment is more “disembodied” than offline environments [36], with fewer interpersonal cues available to inform adolescents’ perceptions of their peers’ beliefs about alcohol, they may be more likely to misperceive (and overestimate) pro-drinking social norms [18]. Thus, powerful injunctive norms may be created via SNS and such norms may impact offline behavior.

Although this study provides a unique opportunity to prospectively examine alcohol use initiation and adolescent SNS use, several limitations should be addressed in future work. First, the study used adolescents’ own reports of exposure to friends’ SNS content, which may be biased due to poor recall or projection of their own drinking behavior onto peers; observational coding of SNS alcohol references has shown promise in work with college students [3,7,8] and should be employed with adolescents. Second, although our measure of alcohol exposure asks about SNS use more broadly, we control only for time spent on Facebook; future work should examine whether time spent on other SNS impacts revealed associations. Third, we were unable to control for peers’ actual drinking behavior in our analyses, which limits the strength of our conclusions regarding the unique impact of peers’ SNS posts, versus “offline” drinking behavior, on adolescents’ alcohol use.

The study’s two-wave longitudinal model provides a critical improvement over previous, cross-sectional studies. However, because data on SNS use were collected at only two time points, formal examination of mediation was not possible. It is possible that initiation of drinking preceded changes in Time 2 injunctive norms or that SNS use changed considerably over the course of the study. Similarly, selection effects, a common confound in the peer influence literature whereby adolescents who are interested in experimentation with alcohol choose to interact with drinking peers, remain a possibility. Future studies, examining short-term associations among SNS exposure, norms, and drinking behaviors across multiple time points are needed to clarify this timeline.

Our findings suggest that adolescents’ perceptions of their “close friends’” beliefs about alcohol use were informed by the activity of “friends” on SNS. Prior work suggests that the majority of adolescents SNS “friends” are peers known offline [37]. However, our measures do not capture which SNS “friends” participants were describing, and it is possible that these “friends” are older individuals or peers not known offline. Interestingly, the percentage of adolescents reporting that “friends” posted alcohol-related content (20.7%) was much greater than the percentage reporting their own posting (7.5%). Although this may indicate social desirability, it may also reflect adolescents’ interpretation of “friends” to include a wider network of online peers. Future work should investigate the role of different SNS “friends” in shaping norms, and whether this differs from offline peer reference groups.

This study has several important implications. Although past studies have indicated cross-sectional associations between SNS alcohol content exposure and peer norms [21], and longitudinal associations with susceptibility to alcohol use [22], this study is the first to examine initiation of various drinking milestones following exposure to alcohol content. Initiation of alcohol use is an important prevention target, as age of drinking onset is highly correlated with adverse outcomes. Furthermore, results may inform future intervention efforts around youth substance use. Previous work indicates the utility of “media literacy” training in teaching youth to critically evaluate media messages around alcohol [38], and such programs may benefit from adaptation to fit the social media context. Similarly, prevention programs that address peer influence and norms around substance use [39] are shown to reduce adolescent alcohol use behaviors. Such programs could explicitly address the role that SNS content plays in creating perceptions of peer norms around drinking. Finally, by examining the role of SNS in contributing risk for alcohol use, findings contribute to a growing literature [40] indicating potential for SNS to serve as a unique platform for digital intervention efforts that explicitly target adolescents.

Implications and Contribution.

These results demonstrate that adolescents’ exposure to friends’ alcohol-related posts on social networking sites longitudinally predicts initiation of drinking behaviors. This exposure may lead adolescents to develop alcohol-favorable peer injunctive norms. Further research should examine how and for whom peer influence via social media occurs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from NIAAA (R01 AA016838; PI Jackson and K02 AA13938; PI Jackson). This work was also supported in part by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1144081 awarded to Jacqueline Nesi. We wish to sincerely thank the project staff and research participants who made this study possible.

List of Abbreviations

- SNS

Social Networking Sites

- HED

Heavy Episodic Drinking

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIAAA or NSF.

Submission Declaration. This work has not been published previously, nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere. All authors approve of its publication; if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere.

Preliminary results were presented as a poster, Exposure to friends’ alcohol-related social networking site posts predicts adolescents’ initiation of drinking behaviors, at the Society for Research on Adolescence biennial meeting in Baltimore, Maryland (Rothenberg, Nesi, & Jackson, April 2016).

References

- 1.Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015. Pew Res Cent Internet Sci Tech. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingstone S, Smith PK. Annual Research Review: Harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: the nature, prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:635–654. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno MA, Cox ED, Young HN, et al. Underage College Students’ Alcohol Displays on Facebook and Real-Time Alcohol Behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson KM, Sartor CE. The Natural Course of Substance Use and Dependence. Oxf Handb Fo Subst Use Subst Use Disord. 2014;1 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bava S, Tapert SF. Adolescent Brain Development and the Risk for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010;20:398–413. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beullens K, Schepers A. Display of Alcohol Use on Facebook: A Content Analysis. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:497–503. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, et al. A Content Analysis of Displayed Alcohol References on a Social Networking Web Site. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths R, Casswell S. Intoxigenic digital spaces? Youth, social networking sites and alcohol marketing: Intoxigenic digital spaces? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Survey on American Attitudes on Substance Abuse XVII: Teens. National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. Media Psychol. 2001;3:265–299. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin EW, Chen M-J, Grube JW. How does alcohol advertising influence underage drinking? The role of desirability, identification and skepticism. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly AB, Chan GCK, Toumbourou JW, et al. Very young adolescents and alcohol: Evidence of a unique susceptibility to peer alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2012;37:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Getting drunk and growing up: trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and Injunctive Norms in College Drinking: A Meta-Analytic Integration. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:331. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litt DM, Stock ML. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: The roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:708–713. doi: 10.1037/a0024226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, et al. Real Use or “Real Cool”: Adolescents Speak Out About Displayed Alcohol References on Social Networking Websites. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Age and drinking-related differences in the memory organization of alcohol expectances in 3rd-, 6th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:579–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corte C, Szalacha L. Self-Cognitions, Risk Factors for Alcohol Problems, and Drinking in Preadolescent Urban Youths. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2010;19:406–423. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2010.515882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beullens K, Vandenbosch L. A Conditional Process Analysis on the Relationship Between the Use of Social Networking Sites, Attitudes, Peer Norms, and Adolescents’ Intentions to Consume Alcohol. Media Psychol. 2016;19:310–333. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, et al. Peer Influences: The Impact of Online and Offline Friendship Networks on Adolescent Smoking and Alcohol Use. J Adolesc Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang GC, Soto D, Fujimoto K, et al. The interplay of friendship networks and social networking sites: longitudinal analysis of selection and influence effects on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e51–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker JS, Miles JNV, D’Amico EJ. Cross-Lagged Associations Between Substance Use- Related Media Exposure and Alcohol Use During Middle School. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson KM, Roberts ME, Colby SM, et al. Willingness to Drink as a Function of Peer Offers and Peer Norms in Early Adolescence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:404–414. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson KM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sipping alcohol in a prospective middle school sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29:766–778. doi: 10.1037/adb0000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuligni AJ, Eccles JS. Perceived parent^child relationships and early adolescents’ orientation toward peers. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:622–632. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, et al. Do Parents Still Matter? Parent and Peer Influences on Alcohol Involvement Among Recent High School Graduates. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, et al. Impact of Alcohol Advertising and Media Exposure on Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin EW, Meili HK. Effects of interpretations of televised alcohol portrayals on children’s alcohol beliefs. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1994;38:417–435. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, et al. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behav Ther. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elek E, Miller-Day M, Hecht ML. Influences of personal, injunctive, and descriptive norms on early adolescent substance use. J Drug Issues. 2006;36:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller DT, Prentice DA. The construction of social norms and standards. In: Higgins FT, Kruglanski AW, editors. Soc. Psychol. Handb. Basic Princ. New York, NY: Guilford; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nadkarni A, Hofmann SG. Why do people use Facebook? Personal Individ Differ. 2012;52:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subrahmanyam K, Šmahel D. Digital youth: the role of media in development. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reich SM, Subrahmanyam K, Espinoza G. Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:356–368. doi: 10.1037/a0026980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown JD, Witherspoon EM. The mass media and American adolescents’ health. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:153–170. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry CL, Williams CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, et al. Project Northland: outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:956–965. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno MA, Grant A, Kacvinsky L, et al. College Students’ Alcohol Displays on Facebook: Intervention Considerations. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60:388–394. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.663841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]