Abstract

Background:

Zirconia has emerged as a versatile dental material due to its excellent aesthetic outcomes such as color and opacity, unique mechanical properties that can mimic the appearance of natural teeth and decrease peri-implant inflammatory reactions.

Objective:

The aim of this review was to critically explore the state of art of zirconia surface treatment to enhance its biological and osseointegration behavior in implant dentistry.

Materials and Methods:

An electronic search in PubMed database was carried out until May 2018 using the following combination of key words and MeSH terms without time periods: “zirconia surface treatment” or “zirconia surface modification” or “zirconia coating” and “osseointegration” or “biological properties” or “bioactivity” or “functionally graded properties”.

Results:

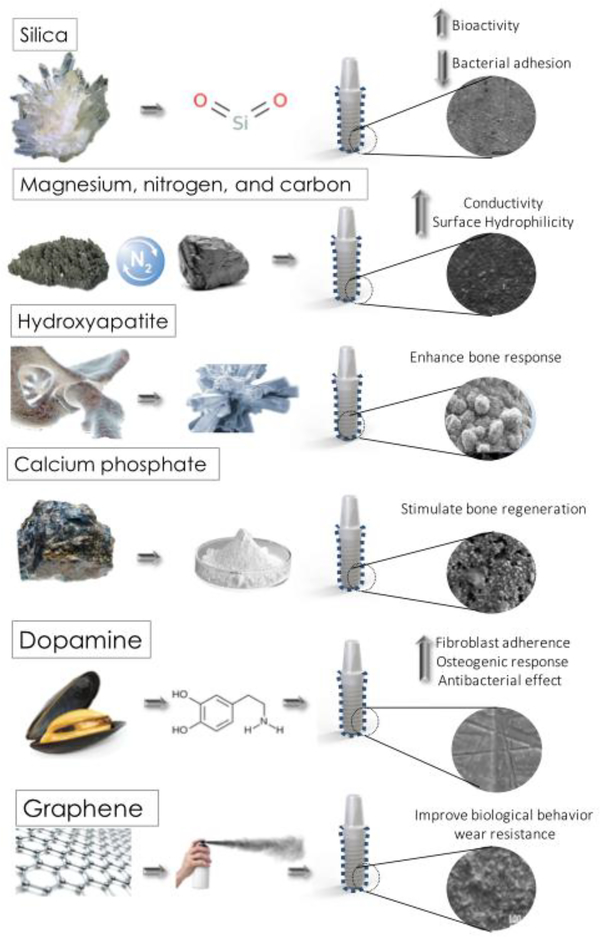

Previous studies have reported the influence of zirconia-based implant surface on the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblast and fibroblasts at the implant to bone interface during the osseointegration process. A large number of physicochemical methods have been used to change the implant surfaces to improve the early and late bone-to-implant integration, namely: acid etching, gritblasting, laser treatment, UV light, CVD, and PVD. The development of coatings composed of silica, magnesium, graphene, dopamine, and bioactive molecules has been assessed although the development of a functionally graded material for implants has shown encouraging mechanical and biological behavior.

Conclusion:

Modified zirconia surfaces clearly demonstrate faster osseointegration than that on untreated surfaces. However, there is no consensus regarding the surface treatment and consequent morphological aspects of the surfaces to enhance osseointegration.

Keywords: zirconia, surface modification, implant surface, zirconia surface treatment, bioactivity, osseointegration, functionally graded materials

1. INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal (Y-TZP) has emerged in dentistry as a promising material for various applications such as multi-unit, crowns, onlays, inlays, and implant structures, due to its aesthetic outcomes such as color and opacity that mimic a natural teeth appearance [1]. Zirconia-based materials have been claimed as a biomaterial with a high chemical stability that avoid the release of toxic products to the surrounding tissues [2,3]. Y-TZP provides stimulation of osteogenic cells during osseointegration in combination with unique mechanical characteristics such as high fracture toughness, fatigue resistance, high bending strength, high corrosion resistance, and radiopacity, as well as a higher affinity to bone tissue than most alternative biocompatible ceramics [4,5]. Additionally, some studies have shown that zirconia decrease bacteria adhesion and biofilm accumulation leading to low risk of inflammatory reactions in adjacent peri-implant tissues [6–8]. Moreover, recent in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that zirconia implants have similar results regarding osseointegration indexes when compared to titanium implants [9–15]. Nevertheless, corrosion and the greyish color of titanium are both considered as disadvantage since that can affect health state and appearance of the peri-implant tissues, causing aesthetic drawbacks [16,17].

In implant dentistry, osseointegration is a biological dynamic process described as the direct contact of bone tissue to the implant surface that depends on factors related to the implant, surgical site, bone type, and patient conditions [9,18–20]. The bone to implant contact (BIC) can be measured by histomorphometric analyses at different time points over the period of osseointegation [10,19–22]. Previous studies have reported similar results for bone healing surrounding zirconia or titanium implants [6,13,15,23]. However, zirconia-based surfaces have revealed lower number of bacteria when compared to implant surfaces regarding microbiological assays [24,25]. Despite the favorable findings recorded for zirconia-based surfaces, clinical long-term results are still lacking and some controversies towards zirconia osseointegration are still being debated. Some previous studies have reported high failure rates and zirconia peri-implant crestal bone loss in human studies [8]. Also, zirconia has been claimed as an inert biomaterial [2,3] although the adsorption of blood protein, platelets and migration of cells suggest a biological interaction with zirconia-based surfaces. That should be further studied considering chemical bonding and the deterioration of zirconia. Even though zirconia implants offer aesthetic benefits over titanium implants, titanium-based materials still possess higher mechanical strength over zirconia and it is currently the first-choice material for dental implants. Nevertheless, implant technology has devoted significant efforts to modify zirconia regarding morphological and bioactive aspects that is desirable for an appropriate cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation during the surrounding bone healing [3,26]. On improving zirconia surfaces, several physicochemical methods have been used such as: grit blasting [27], laser treatment [28], micro-machining, CVD, and PVD. The development of coatings composed of silica, magnesium, graphene, dopamine, and bioactive molecules has been assessed although the development of a functionally graded material for implants has shown an enhancement in mechanical behavior and biological response face [28].

Thus, the aim of this review was critically explore the state of the art of surface treatments to enhance the biological and osseointegration behavior of zirconia-based implants in dentistry.

2. SEARCH STRATEGY

A literature review was performed on PUBMED database to identify relevant studies regarding zirconia surface treatment to enhance osseointegration. The electronic search was performed using the following combination of key words and MeSH terms: “zirconia surface treatment” OR “zirconia surface modification” OR “zirconia coating” AND “osseointegration” OR “biological properties” OR “bioactivity” AND “mechanical properties” OR “functionally graded properties”. The inclusion criteria used for this review involved clinical trials, meta-analyses, in vivo, and in vitro studies written in English language up to May 2018. Three of the authors (BH, MEG, FHS) independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant previous studies. Selected studies were individually read and analyzed concerning the focus of the present review, which was to discuss and summarize important key publications regarding zirconia surface modifications for dental implants. Author names, journal, publication year, objectives, methods, and main outcomes were retrieved from the selected relevant articles.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Investigations have suggested that zirconia surface modification influences on osteoblast and fibroblasts adhesion, proliferation, morphology, and differentiation leading to the osseointegration of implant surfaces and fit to the soft peri-implant tissue [29,30]. The understanding of surface physicochemical modifications on biocompatibility and osseointegration measured by histomorphometric analyses have been copiously evaluated to predict the clinical outcome and peri-implant tissue stability over time [31,32]. Accordingly, a large number of methods have been developed to change dental implants physicochemical properties to accelerate and improve the early and late bone-to-implant response [19] as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematics and SEM images on different zirconia surface modifications: machined [33], acid etched [34], grit blasted [33], ZLA [25], and multi-layered coatings [35–38].

Table 1.

BIC percentage and roughness values among machined surface, grit blasted surface, acid etched surface, laser, and UV light modified zirconia surface after different time points.

| Author | In Vivo Study | Surface Treatment | Roughness (μm) | BIC (%) | Weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scarano et al. 2003 [6] | Rabbit | Machined | - | 68.4 ±6 2.4 | 4 |

| Kim et al. 2017 [41] | Rabbit | Machined | - | 32.15 ±10.8 | 4 |

| Aboushelib et al. 2013 [42] | Rabbit | Machined | - | 62.14 ±2.8 | 6 |

| Han et al. 2016 [18] | Rabbit | Machined | 0.788 | 78.9 | 8 |

| Hoffmann et al. 2012[43] | Rabbit | Machined | - | 33.74 ±14.5 | 12 |

| Koch et al. 2010 [44] | Dog | Machined | - | 59.11 ±7.5 | 4 |

| Montero et al. 2015[45] | Dog | Machined | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 57 ±15.2 | 20 |

| Thoma et al. 2015 [40] | Dog | Machined | - | 87.7 ±25.1 | 24 |

| Hoffmann et al. 2012 [43] | Rabbit | Sandblasted | - | 41.350 ±15.8 | 12 |

| Schliephake et al. 2010 [46] | Minipig | Sandblasted | 0.98 | 54.6 ±17.6 | 13 |

| Schliephake et al. 2010 [46] | Minipig | Sandblasted and Acid etched | 1.162 | 57.6 ±23.7 | 13 |

| Kohal et al. 2004 [13] | Monkey | Sandblasted | - | 67.4 ±17 | 36 |

| Bacchelli et al. 2009 [27] | Sheep | Sandblasted | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 75.1 ± 4.2 | 12 |

| Gahlert et al. 2012 [10] | Pig | Acid Etched | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 63 ±21.5 | 12 |

| Depprich et al. 2008 [9] | Minipigs | Acid Etched | 0.598 | 71.4 ±17.8 | 12 |

| Liñares et al. 2016 [47] | Minipigs | Sandblasted and Acid Etched | - | 86.24 ±9.7 | 8 |

| Janner et al. 2018 [48] | Dog | Sandblasted and Acid Etched | - | 71.15 ±7 | 16 |

| Kubasiewicz-Ross et al. 2018 [11] | Minipigs | Sand Blasted Acid Etched Sand Blasted & Etched |

- | 66.75 72.9 68.8 |

8 |

| Cavo-Guirado JL et al. 2015 [49] | Dogs | Laser modified | - | 47.9 | 12 |

| Delgado-Ruiz et al. 2015 [50] | Dogs | Laser modified (femtosecond laser) | - | 60.34 ±4.3 | 8 |

| Delgado-Ruiz et al. 2014 [51] | Dogs | Sandblasted Laser Modified (femtosecond laser) | 2.83 ± 0.2 9.6 ± 0.62 |

48 ±3 78 ±5 |

8 |

| Cavo-Guirado et al. 2014 [52] | Dogs | Laser Modified | - | 65 ± 4.4 | 12 |

| Hoffmann et al. 2012 [43] | Rabbit | Laser Modified | - | 43.87 ±14.5 | 12 |

| Brezavscek et al. 2016[53] | Rat | UV light (15 min) machined UV light (15 min) rough |

0.12 ± 0.02 0.21 ± 0.08 |

52.7 86.5 |

4 |

(−) absent data in the study

3.1. Machined zirconia implants

Implant dentistry chronological records have reported the success and favorable histologic outcomes of titanium machined dental implants over a period of 50 years [3]. As follows, machined zirconia implant have been studied showing promising results on the enhancement of osseointegration and an additional antibacterial activity. Scarano et al. examined BIC of machined zirconia implants fort 4 weeks and reported BIC values of around 68.4% without the presence of inflammatory or multinucleate cells claiming that machined zirconia implants can be highly biocompatible and osseointegrated [6]. Hafezeqoran et al. compared in a systematic the BIC percentage of machined zirconia and titanium dental implant from previous studies. Such previous review article reported statistically equivalent BIC% values for machined zirconia (33.74% - 84.17%) compared to machined titanium implants (31.8% - 87.95%). Consequently, the study concluded that machined zirconia implants can be as osseointegrated as machined titanium implants [39]. The BIC percentage range of machined zirconia implants analyzed in histological studies that range from can be seen in Table 1. The highest BIC percentage value corresponded to a study [40] which evaluated zirconia implants for 6 months while the lowest BIC values (32%) were related to evaluation for 4 weeks after surgery[41]. Thoma et al. (2015) showed that non-modified zirconia implants had a statistically similar BIC percentage and peri-implant soft tissue dimensions to acid etched-sandblasted titanium implants although zirconia implants exhibited a considerable fracture rate after 6 months of loading [40].

Considering antibacterial response, Roehling et al. investigated multi-species biofilm adherence on zirconia machined (ZrO2-M) surface compared to titanium machined (Ti-M) surface. A statistically significant decrease in the biofilm thickness was noticed on zirconia-based surfaces when compared with titanium machined surfaces [25].

3.2. Grit blasted and acid etched zirconia surface treatment

Previous studies have reported that airborne particle abrasion known as grit blasted surface treatment followed by acid-etching (SLA treatment) to increase the surface area of zirconia implants for osseointegration [13,54,55] (Table 1). The grit blasting process with 50–110μm Al2O3 particles, has been shown as an alternative to increase the surface area for osteoblasts attachment and then to speed up the osseointegration process. For Gahlert et al. (2007) [33] and Bacchelli et al. (2009), grit blasting zirconia implant surfaces significantly improved the peri-implant osteogenesis and osseintegration when compared to machined titanium surfaces [10,27]. Gahlert et al. (2007) recorded the removal torque on 64 implants, including zirconia grit blasted with Al2O3 particles, machined zirconia, and grit blasted titanium (with 0.2–0.5 μm Al2O3) structures. The results showed significantly higher removal torque values for grit blasted zirconia (40.5 N/cm) and titanium (105.2 N/cm) than those recorded on machined zirconia (25.9 N/cm) surfaces [33].

Other studies have shown different results, Kohal et al (2004) investigated the osseointegration on unloaded zirconia implants compared to titanium implants five months after tooth extraction. The titanium implant surfaces were grit blasted with Al2O3 and acid etched (H2O2/HF) while zirconia implants were only grit blasted with 50 μm Al2O3/50μm. The results showed that the mean height of the soft peri-implant tissue cuff was 5 mm around the titanium implants and 4.5 mm around the zirconia implants. The BIC was around 72.9% on titanium implants and 67.4% on zirconia implants. With these results, the mentioned study concluded that grit blasted zirconia implants revealed similar integration to bone and peri-implant soft tissue dimensions when compared to SLA titanium implants [13].

Moreover, grit blasting has been performed with additional chemical treatments such as: hypo-phosphorous acid, mixture of KOH, and NaOH to improve BIC of zirconia. Though, hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching appears to be the first choice to enhance bone apposition resulting in higher implant removal torque values [34,56]. The incorporation of fluoride at the ceramic surface could enhance osteoblastic differentiation and interfacial bone formation, as found for fluoridated titanium surfaces [57–59]. A commercially zirconia implant treated with HF etching showed BIC at 81% [60].

Besides, other studies have reported the effect of acid etching treatment on zirconia surfaces and its impact on biofilm adhesion. Depprich et al. (2008) compared the BIC percentage for 24 Y-TZP acid-etched implants (Ra=0.598μm) with 24 acid etched titanium implants (Ra=1.77μm). The peri-implant tissues were histologically inspected after 1, 2, and 4 weeks. A significant BIC increase was observed on acid etched zirconia implants compared to titanium implants [9]. Also, when Roehling et al. (2017) reported a decrease in biofilm growth on grit blasted and acid etched zirconia surface (ZrO2-ZLA) when compared with titanium grit blasted titanium surface (Ti-SLA) [25].

In another study, zirconia disks were acid etched in 5%, 20% and 40% HF for 30 min, 1h and 2h (Flamant et al., 2016). The concentration and time that had the most uniform and faster roughening were 40% and 60 min, but no strength or fatigue tests were performed. In this study, the etching at 40% HF dissolved zirconium and yttrium oxide producing fluoride, and hydroxide complexes. Yttrium oxides have very low solubility in 40% HF leading to the precipitation of yttrium trifluoride octahedral crystals on the surface. Yet, zirconium oxides are partially soluble an bonded to yttrium, zirconium and fluoride precipitates, probably because the saturation threshold for zirconium fluoride complexes [34]. Oh et al. (2017) tested HF in two different concentrations (10% and 20%) and in different time points (1, 2, 10, and 60 min) in pure zirconia, porcelain, and in bioactive glass that was infiltrated into pre-sintered zirconia. The roughness of zirconia was not affected by the etching time or the concentration of the acid although etched bioactive glass-infiltrated zirconia revealed similar surface topographic aspect when compared to grit blasted/acid-etched titanium [61].

Hempel et al. (2010) cultured osteoblasts SAOS-2 cells on grit blasted, grit blasted/etched zirconia and compared with grit blasted/etched titanium. The findings showed an increase in adhesion, spreading, and differentiation of SAOS-2 cells when compared with titanium. However, there was no significant differences between zirconia surface treatments [62]. Additionally, Bergenmann et al. compared the human primary osteoblasts osteogenic marker gene modulation on different zirconia surfaces: machined, grit blasted, acid etched/grit blasted and acid etched/sandblasted/heated with machined titanium implants. The present study showed that both acid etched surfaces with Ra roughness values of around 1.3 μm had a drastically increase of osteocalcin expression and cell adherence when compared with machined titanium (Ra: 0.54 μm) and machined zirconia (Ra at 0.59 μm). In fact, higher roughness values corresponded to acid etched surfaces with a more favorable area for osteoblasts adhesion [63]. The roughness values recorded in the previous studies corresponded to the moderate rough titanium implants that has been claimed to promote high BIC percentage and successful osseointegration in previous in vivo studies[64].

An in vivo study reported the BIC percentage around zirconia implants after surface conditioning in different solutions. HF acid etching and immersion in NaOH and KOH was compared regarding the enhancement of osseointegration and therefore the BIC percentage was higher for the etched surfaces in HF. Those surface treatments induced the proliferation of multinucleated giant cells around the implant surfaces [65]. Liñares et al (2016) compared nine different zirconia or titanium implants considering the following surface treatment to bone integration in minipig mandibles: grit blasting with large grits of 250–500 μm and acid etched with HCl/ H2SO4. BIC percentage of the titanium implants was around 84% while zirconia revealed a BIC around 86.2%. Additionally, gingival tissue around zirconia implants presented higher organization of collagen fibers and lower sulcus depth measurements than that inspected around titanium. That suggested a more mature and organized peri-implant soft tissue around zirconia implant surfaces [47].

Even though the described surface treatments have provided surface topographic and biological advantages, the mechanical properties of treated zirconia can change affecting the clinical long performance of the implant. The strength and phase transformation of grit blasted zirconia has been questioned by previous studies [54,66,67]. Grit blasting can induce stress concentration and consequently a transition from tetragonal to monoclinic phase. Thus, this phase transition can improve zirconia mechanical properties due to the introduction of compressive stress, but can also cause degradation of zirconia affecting its density and mechanical stability [54,68]. A systematic review reported that the flexural stress of grit blasted yttria-stabilized zirconia increased, regardless abrasion factors and aging effect [67]. Studies have also reported that grit blasting decrease the fatigue resistance of zirconia [66]. A study showed that grit blasting zirconia with 105 μm alumina, HF acid etching, and 1h of heat treatment is a reliable process to increase zirconia roughness to 1.2 μm which is comparable to the standard titanium roughness (1.5 μm) that can support a successful osseointegration rate [64]. That study showed an increase if the zirconia flexural strength after grit blasting, nevertheless the fatigue strength was not assessed [54,64]. As a matter of fact, the strength of zirconia might be reduced by particle abrasion, since that can cause deep micro-cracks. At first, any compression caused by particle abrasion can strengthen and inhibit micro-crack extension due to zirconia phase transformation supporting the results from previous studies on the benefits of grit blasting [54,67]. Nevertheless, Zhang et al. have shown in their study that the compressive stresses caused by grit blasting are not enough to counteract the strength loss caused by micro-cracks specially under high static load and fatigue tests which resemble real clinical conditions [66]. Clinically, zirconia implants should be grit blasted with soft and round particles, avoiding the use of sharp particles to decrease the formation of micro-cracks. More studies involving fatigue tests are needed to evaluate which grit blasting parameters are proper to attain a desired roughness and to decrease microcrack formation [54,66].

Other studies have also revealed that heat and acid treatment can decrease zirconia flexural strength due to tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation and low temperature degradation conditions[69,70]. In a recent study, Xie et al. evaluated the effects of three types of acid treatments on zirconia. Hydrofluoric (HF), acetic, and citric acid were tested at different concentrations. HF acid was the most efficient to increase roughness, however, 40%HF treatment at room temperature decreased considerably the surface hardness and flexural strength of the samples. As follows this study concluded that the acid concentration should be maximum 5% to avoid any potential damage to zirconia mechanical structure [55]. Fischer et al. showed that after 4 h of HF etching, zirconia strength decreased after 4h HF etching while 1h etching was recommended although a short time of etching could not improve the morphological aspects of zirconia implants [54]. Even though acid etched zirconia has been claimed as a promising material that enhances osseointegration, further studies are needed to determine which etching conditions would not affect the mechanical behavior of zirconia.

3.3. Ultraviolet light treated zirconia

Regarding in vitro and in vivo studies, UV light treatment has been claimed to be an effective zirconia surface treatment to enhance the attachment, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblast without affecting zirconia mechanical properties [53,71]. UV light can induce electron excitation, increasing zirconia surface energy. Henningsen et al. reported an increase in wettability of zirconia surfaces treated by UV light to an ultra-hydrophilic state. The water contact angle of grit blasted zirconia surfaces decrease from 51° down to 9.4° after UV light treatment, as seen in Table 2 [71]. The fact that UV treatment increases zirconia wettability was also supported by another previous study testing only 15 min UV light [56]. Additionally, histomorphometric analysis revealed that UV treated zirconia specimens had a faster osseointegration process and higher BIC percentage (86.5%) when compared to untreated zirconia after 2 and 4 weeks of implantation. After 4 weeks, untreated samples had still fibrous connective tissue at the implant-bone interface while UV treated samples were almost entirely surrounded by bone (Table 1). Another study showed that UV treated zirconia became super-hydrophilic and increase human alveolar bone-derived osteoblasts attachment and spreading after 21 days when compared to untreated samples concluding that UV treatment can induce faster healing and higher BIC percentage [72]. Even though, some studies have suggested that UV surface treatment is a promising strategy to promote bone morphogenesis around zirconia implants, additional in vivo studies are needed to validate this concept [53,71,73].

Table 2–

Water Contact angle and wettability measured in several studies for different types of zirconia surface treatments

| Author | Materials | Treatment | Contact angle | Wettability | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Radha, 2012 [79] | Titanium | Polished titanium | 74.32 ± 1.34° | Hydrophilic | Sandblasting: Zirconia powders with particle size ≤44 μm; 4.5 bar; 3 cm distance acid etching: 0.2 wt.% hydrofluoric acid for 1.5 min |

| Titanium blasted with zirconia | 87.3 ± 5.00° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Titanium blasted with zirconia/acid etched | 131.51 ± 1.50° | Hydrophobic | |||

| ZrO2-TZP-A-HIP | Polished | 82.79 ± 2.10° | Hydrophilic | ||

| Y, Cho. 2015 [80] | (Y, Nb)-TZP and (Y, Ta)-YZP | HA-coated surfaces (after sandblasting) | 63.72 ± 2.55° | Hydrophilic | Sandblasting: 50 μm Al2O3 at 2 bar and 1 bar HA Film by Aerosol Deposition: ~10 μm |

| Non-coated zirconia surfaces (sandblasted) | 95.0 ± 3.21° | Hydrophobic | |||

| Liu, M. 2015 [32] | Y-ZrO2 (Zenostar) | Polished + Polydopamine coating | 64 ± 1° | Hydrophilic | Zirconia: Zenostar, Wieland Dental, German dopamine solution: (2 mg/mL in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) and gently shaken for 24 h at room temperature |

| Uncoated (Polished) | 78 ± 4° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Yang Y. 2015 [75] | Y-ZrO2 (Zenostar) | Polished + UV light treatment | 33.76° | Hydrophilic | Zirconia: Zenostar, Wieland Dental, German UV light; 24 h; 10-W bactericidal lamp; 17 mW/cm2 Sandblasting: (Al2O3) particles (25 μm) from a distance of about 20 mm at 0.2 MPa |

| Polished | 51.98° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Sandblasted + UV light treatment | 36.15° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Sandblasted | 63.87° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Moura, CG. 2017 [28] | 3Y-TZP | As sintered | 46.9 ± 5° | Hydrophilic | Sandbasting: Al2O3; 100 μm particles; 6 bar; 10 mm distance Etching: hydrofluoridine acid (48%) for 30 min; Laser: Nd: YAG laser |

| Sandblasting and etching treatment | 44.6 ± 3° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Laser irradiation (0.9W) | 38.2 ± 1° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Laser irradiation (1.8W) | 36.4 ± 1° | Hydrophilic | |||

| Henningsen A, 2018 [71] | Titanium grade IV | Sandblasted + acid etched | 111° | Hydrophobic | Sandblasting: ZrO2 particles UV light at λ=360nm (0.05mWcm−2) and λ =250nm (2 mW cm−2) Non-thermal plasma of either Argon and oxygen using a non-thermal plasma reactor |

| UV | 12.8° | Super-Hydrophilic | |||

| O2-Plasma | 0 | Super-Hydrophilic | |||

| Ar-Plasma | 0 | Super-Hydrophilic | |||

| 5Y-TZP | Zirconium dioxide blasted | 51° | Hydrophilic | ||

| UV | 9.4° | Super-Hydrophilic | |||

| O2-Plasma | 4.2° | Super-Hydrophilic | |||

| Ar-Plasma | 2.9° | Super-Hydrophilic |

3.4. Zirconia laser modification

Laser treatment is a promising alternative to modify and enhance zirconia osseointegration [71,73–76]. Hoa et al. used a CO2 laser to modify Y-TZP surfaces and possibly achieve a higher osseointegration index. The defocused CO2 laser beam was traversed in single time across the Y-TZP surface at different intensities, namely 1.80 and 2.25 kW/cm2. The CO2 laser treatment decrease the roughness of the samples from 0.35 μm down to 0.2 μm although that increased the surface energy and consequent wettability [77].

Moura et al. investigated the influence of surface texturing on Y-TZP by using laser treatment compared to different surface treatments: as sintered sample (AS), grit blasting and acid etching treatment (SE), laser irradiation using two output power of 0.9 W (LI) and 1.8 W (LII). The surface was analyzed by SEM/EDS analyses, water contact angle, friction test by bone plates and by roughness analysis. The water angle contact of laser treated Y-TZP was 36.4° (LI) and 38.2° (LII) while the AS and SE groups presented higher water contact angle values (46.9° ± 5° for AS and 44.6° ± 3° for SE) that showed a lower hydrophilicity. In fact other in vitro studies have shown that CO2 laser modified zirconia increases osteoblast (hFOB) adherence when compared to untreated samples [77]. It is important to take in consideration that material water contact angles lower than 90° are considered hydrophilic, and less than 20° are super-hydrophilic. As follows, lower contact angles mean the material has a higher wettability, which is biologically a more attractive surface for osteoblast proliferation, protein adsorption, and osseointegration [78]. The contact angle and wettability measured in several studies for different types of zirconia surface treatments are shown in Table 1.

Furthermore, laser treatment has been applied to create micro-grooved surfaces in zirconia implants. The microtexture could change collagen fiber organization, peri-implant bone architecture, and human cell metabolism. Studies have shown that surfaces with a regular geometry in the micro-range can increase osteoblast proliferation, adhesion, spreading and matrix protein synthesis [49,50]. Delgado-Ruiz et al. treated zirconia through femtosecond laser to create a uniform micro-grooved surface with symmetric microstructures. An animal study showed that laser treated microogroved zirconia implants had a high number of transverse collagen fibers and an increased bone remodeling when compared to grit blasted zirconia implants which had parallel collagen fibers and SLA titanium implants which had parallel and transverse fibers but low bone remodeling rates. The difference among bone remodeling rates after 4 months of loading could be explained by the presence of blood vessels and bone cells that penetrated in micro-grooved zirconia surfaces which accelerated the osseointegration rate. Also the presence of transverse collagen fibers create a favorable stress distribution environment in loaded implants favoring bone metabolism[50]. Laser treated microgrooved zirconia implants show promising results, however further studies involving humans are required to validate that.

3.5. Coatings on zirconia

Implant dentistry innovations face the primordial challenge of enhancing biological and mechanical implant properties through approaches like implant coating. Different coatings on zirconia surfaces have been developed to enhance biocompatibility, antibacterial potential, and bioactivity. Bioactive coatings on zirconia have demonstrated advantages for bioactivity, since they have the ability to induce hydroxyapatite formation in a biological environment, which is essential for subsequent bone proliferation. In literature, different coating materials with favorable biologic properties have been described, such as: silica, magnesium, nitrogen, carbon, calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, dopamine, and graphene [26,37,61,81–85].

Laranjeira et al. compared the in vitro behavior of fibroblast adherence and antibacterial effect on different types of silica-coated micropatterned zirconia surfaces. The study results showed that silica coated zirconia samples with different surface morphological aspects reduced bacterial adhesion. Microstructured bioactive coating can also be an efficient strategy for fibrin network formation, cell growth, and improved soft tissue adherence since it reduces biofilm adherence and enhances the adsorption of proteins and cell migration [35]. Additionally, Kirsten et al. analyzed a novel glass composition (PC-XG3) zirconia coating and its in vitro bioactivity using the simulated body fluid (SBF) immersion test. Smooth and microstructured glass coatings were applied on zirconia implants, which showed a strong adhesion to the zirconia substrate and a significant increased in vitro bioactive behavior after SBF immersion [86]. Consequently, silica coatings can increase the zirconia bioactivity promoting hydroxyapatite formation when in contact with body fluids which will stimulate osteoblast proliferation on the implant surface[87], accelerating osseointegration.

Magnesium, nitrogen, and carbon coatings

Studies have reported that magnesium (Mg) coatings favor osteoblast proliferation, increasing the zirconia bioactivity [88]. Pardun et al. [26] reported the influence of Mg addition to zirconia-calcium phosphate and found that Mg containing coatings promoted a higher cell proliferation and differentiation in comparison to pure zirconia-calcium phosphate coatings. Microstructure tests confirmed a porous and a stable coating adhesion not hampered by its composition. Other studies have shown that magnesium-calcium coatings increase the bioactive potential of zirconia. That showed a multilayered hydroxyapatite (HA) precipitate revealing a “cauliflower” morphology after 7 days of SBF immersion[36,89]. Moreover, the addition of other elements like nitrogen and carbon have improved the biological and mechanical properties of zirconia [90]. Another study showed a high hydrophilicity, bioactivity, and antibacterial potential for zirconia containing a nitrogen-doped hydrogenated amorphous carbon (a-C:H:N) layer. Schienle et al. tested the bacterial adherence to 3Y-TZP with a carbon (a- C:H:N) coating and quantified the adherent microorganisms by estimating the colony-forming unit analysis (CFUs). The a-C:H:N coated Y-TZP surfaces revealed a low adhesion of bacteria on the surface compared to uncoated surfaces [83]. Other studies have also coated zirconia with functionalized multiwalled carbon nano-tubes increasing the roughness, wettability, and cell adhesion of this material favoring zirconia´s osseintegration properties [90,91].

Hydroxyapatite and calcium phosphate based coatings

Hydroxyapatite (HA) has a similar mineral composition to that of bone, and thus shows bioactive properties favoring tissue response that enhances osseointegration. HA has been used to coat zirconia in order to convert highly stable implant surface into a bioactive one, thus enhancing its osseointegration features. Porous zirconia scaffolds coated with HA have been used as a drug delivery vehicle to enhance bone response and assure good osseointegration [80,92,93]. Aboushelib and Shawky evaluated the osteogenesis ability of CAD/CAM porous zirconia scaffolds enriched with HA. Results revealed a significantly higher volume of new bone formation (33 ±14%) on HA enriched zirconia scaffolds compared to the scaffolds free of HA (21 ±11%), therefore, demonstrating the HA coating enhanced osteogenesis ability of porous zirconia scaffolds [94]. Pardun et al. obtained coatings by mixing Y-TZP and HA in various ratios. The experiments revealed that the HA dissolution stimulated the adhesion and proliferation of osteoblasts. However, an increasing content of calcium phosphate resulted in a decrease of its mechanical and chemical stability, while the bioactivity increased after immersion in simulated body fluid. As follows, the author demonstrated excellent interfacial bonding, mechanical strength, and the bioactivity potential of coatings with higher tetragonal zirconia contents [84].

Calcium phosphate (CP) is also considered bioactive and thus stimulate bone regeneration due to their chemical composition close to that of the mineral phase of bone commonly named biological apatite. However, pure calcium phosphate coatings exhibit a poor stability and provide a weak bonding strength to the substrate. To overcome these drawbacks of pure CP coatings, studies used tricalcium phosphate reinforced hydroxyapatite (HA/TCP) coatings over zirconia surfaces, with open pores larger than 100 μm, a bonding strength of 24 MPa showing a high interfacial bonding between coating and substrate. Additionally, those coatings exhibited bioresorbable and osteoconductive properties [95,96].

Dopamine

Dopamine, precursor of 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (L-DOPA), was found to be an important component in the adhesive structure of mussels as it can self-cure and adhere strongly to a wide range of organic and inorganic materials [97]. Polydopamine (PDA) coatings can enhance antimicrobial properties and facilitate the protein adsorption and cell adhesion, accelerating biological processes such as osseointegration [98]. The influence of novel PDA coating on zirconia disks regarding soft-tissue integration and antibacterial effect was explored by a previous study [38]. Such study evaluated modified surface zirconia with PDA. The surface topography of zirconia coated with PDA can be seen by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and SEM inspection as shown in Figure 1 and 2. The polydopamine coating decreased significantly the bacterial activity and enhanced fibroblasts adherence, which has an important role in peri-implant soft-tissue integration. Therefore, that surface modification approach holds great potential for improving soft-tissue integration around zirconia abutments, which is another important clinical application in implant dentistry. Additionally, another study reported the coating of zirconia with L-DOPA which was a dopamine-derived residue secreted by marine mussels to promote zirconia biocompatibility and osteogenic response. The preliminary results of this study showed that L-DOPA coated specimens had a higher osteoblast proliferation and spreading when compared to uncoated specimens [99].

Figure 2.

Zirconia coatings showing biological advantages in terms of bioactivity, osseointegration, and antibacterial effects

Graphene coatings

Graphene has been the precursor of a novel multifunctional material that can act as a biocompatible surface coating to improve implant tribological properties and reduce wear [100–102]. Li et al. [37] prepared zirconia/graphene (ZrO2/GNs) composite coatings with a thickness of 5 – 20 nm using an atmospheric plasma spray system. It was noticed that the wear behavior rate of ZrO2/GNs reduced to 1.17×10−6 mm3/N m on 100 N normal loading, which resembled to a 50% decrease compared with the control group (ZrO2 specimens). Moreover, the results indicated that the ZrO2/GNs composite coating exhibited excellent wear resistance and low friction coefficient with the addition of GNs. A GNs-rich transfer layer protected the ZrO2/GNs composite coatings from severe wear by brittle microfracture, which significantly improved its tribological behavior [37]. Further studies should consider graphene to improve zirconia mechanical performance mainly regarding wear resistance in implant dentistry.

2.5. Bioactive graded zirconia-based structures

As previously referred, zirconia-based materials have a high elastic modulus, high chemical stability in human body, and desirable optical properties for esthetic outcomes. Nevertheless, the high elastic modulus results in stress shielding of the hard tissue, leading to local bone resorption. Bioactive ceramics (e.g. calcium phosphate ceramics, bioactive glasses) are reactive to the surrounding medium and stablish chemical bonds with adjacent tissues[103]. Also, those bioactive materials exhibit comparable modulus to hard tissues (bone, enamel, or dentin), which mitigates the stress shielding problems. Unfortunately, bioactive ceramics are relatively weak and thus structurally unstable, which hinders their use in load bearing applications (e.g. dental and orthopedic implants)[104].

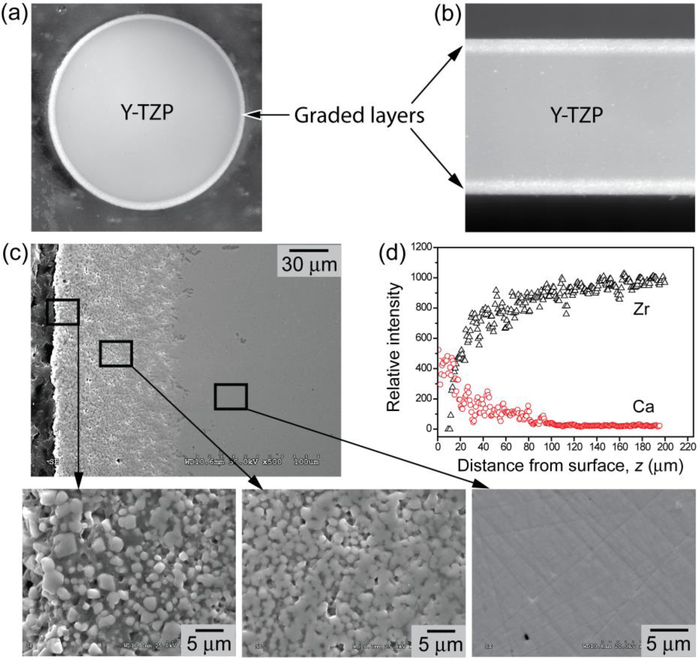

Attempts have been made to produce bioactive glass coatings on zirconia substrates but with limited success. These coatings often undergo delamination and fracture caused by the coating/substrate bonding issue, mismatch in coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), and the abrupt changes in physical properties at the coating/substrate interface. To overcome such issues, Zhang et al [105,106] proposed a bio-inspired strategy regarding transition in chemical composition and properties, as seen in Figure 6 [107–109]. That strategy relies on a functionally graded calcium phosphate-based glass/zirconia (CPG/Y-TZP) system with a low elastic modulus and a flexural strength similar to, or even higher than that recorded for Y-TZP [4,110,111].

Figure 6:

Optical micrographs of graded CPG/Y-TZP (a) rod (2 mm in radius) and (b) plate (1.2 mm thick) sections consisting of (c) CPG infiltrated Y-TZP (SEM image); (d) Energy dispersive X-ray line mapping from surface to interior, revealing a gradual transition in Ca and Zr contents. Higher magnification SEM images, insets of (c), showing: gradual transition from the surface residual CPG layer (left) to the graded CPG/Y-TZP structure (center) and to dense Y-TZP interior (right), modified from Zhang et al. US8703294 B2 – Bioactive graded zirconia-based structures, 2014.

The osteoconductive CPG coating can speed up the osteointegration process and prevents micromotion at the implant/tissue interface [4,105,112] In addition, the residual outer surface CPG layer acts as an encapsulation layer, preventing hydrothermal degradation of the Y-TZP interior, and can be further transformed to a carbonate apatite (CHA) layer by immersing in mineral precipitate solution or simulated body fluid (SBF) since the newly formed bone is directly attached to a CHA layer. Despite the aforementioned advantages of this system, there is only a few studies on CPG/Y-TZP, contrasting to a vast literature on glass infiltrated zirconia structures [4,104,107–114].

4. CONCLUSIONS

The current challenge in implant dentistry is to develop a surface treatment or zirconia-based structure that can have bioactive, mechanical, and osteogenic properties guarantying favorable early and long time clinical results. The present review analyzed and explored the techniques currently reported for zirconia surface treatment and concludes important key points depicting desirable osseointegration, mechanical, and antibacterial properties as follow:

Osseointegration depends on time and bone quality, heterogeneous in vivo studies involving different animal models, healing and loading periods, and diferent surgical sites limit an objective comparison among bone to implant contact results. Standard guidelines in methods, materials and surfaces are recommended to compare results among scientific studies;

Machined zirconia implants have shown an adequate osseointegration when compared to machined titanium implants, however, treated zirconia implants have shown higher bone to implant contact indexes. An increase in roughness and improvement of surface morphological aspects can speed up the osseointegration process for both zirconia or titanium implants;

-

No surface treatment has been claimed as first choice to increase zirconia osseointegration potential, however surface modifications that increase roughness, wettability, and surface energy in which osteoblasts can proliferate, adhere and spread are recommended to accelerate this dynamic process. Bioactive based graded structures and coatings are recommended to increase zirconia´s bioactivity and osseointegration.

Grit blasting, acid etching, and heat treatment on zirconia should not decrease its mechanical properties such as flexural strength and fracture load. Smooth and round particles for grit blasting are recommended to avoid micro-crack formation.

Studies have shown that high acid concentrations, over etching time and heat is not recommended since it can increase the degradation of zirconia;

Functionally bioactive graded zirconia can improve the mechanical strength (e.g., flexural strength and fracture toughness) and biological properties of zirconia. Bioactive materials added on the surface can improve osseointegration and decrease biofilm accumulation;

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that machined and acid etched zirconia decrease the adhesion of bacterial when compared to titanium. The low affinity of zirconia to biofilm and a favorable soft tissue adaptation is an essential aspect since it could reduce peri-implantitis rates which is the major current issue and cause of failure of titanium implant dentistry;

Modified zirconia-based surfaces should be evaluated in clinical studies to provide realistic point view of how oral biofilms, loading, and other patient conditions may affect the properties of zirconia. To date most studies are in vitro or animal studies, which do not provide realistic results.

5. OUTLOOK AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Bioengineering advances have modified zirconia implant surfaces in various ways to improve and accelerate bone healing response and clinically decrease the patient´s edentulous period. Moreover, zirconia has been coated with bioactive particles and multifunctional molecules which can induce an osteogenic stimulus, fibroblast adherence, and an additional antibacterial effect. In this way, zirconia can change from a “criticized bioinert” surface to a “bioactive” and multifunctional one pursuing the most favorable biologic and mechanical peri-implant tissue responses. Current studies show that zirconia can be converted into a bioactive system embedding diverse biomolecules that can mimic in a more realistic way bone tissue structure in a macro- and micro molecular level being able to induce various cell responses that favor implant treatment outcome. However, mechanical failure and crestal bone loss occurring around zirconia implants due to technical and biological complications converts the indication of zirconia as “first choice” implant material in a controversial issue [40,115,116]. Still, future in vitro, in vivo, and long term clinical studies are needed to evaluate success rates of treated zirconia implants in function. These studies should evaluate zirconia implants over time in terms of peri-implant bone stability, absence of inflammation, infection, mobility, and mechanical complications which will give a clearer panorama of which zirconia surface should be indicated.

Highlights.

Machined zirconia and titanium implants have shown an adequate osseointegration

Treated zirconia implants have shown improved BIC% over machined ones

No surface treatment has been claimed as first choice for zirconia’s osseointegration

Bioactive graded structures can improve zirconia´s bioactivity and osseointegration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by FCT-Portugal (UID/EEA/04436/2013, NORTE-01–0145-FEDER-000018 – HAMaBICo, FCT/02/SAICT/2017/3103-LaserMULTICER), CNPq-Brazil (PVE/CAPES/CNPq/407035/2013–3; CNPq/421229/2018–7) and by the United States National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant numbers R01DE017925, R01DE026772, and R01DE026279).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Stadlinger B, Hennig M, Eckelt U, Kuhlisch E, Mai R, Comparison of zirconia and titanium implants after a short healing period. A pilot study in minipigs, Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 39 (2010) 585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Piconi C, Maccauro G, Zirconia as a ceramic biomaterial, Biomaterials. 20 (1999) 1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yin L, Nakanishi Y, Alao A, Song X, A review of engineered zirconia surfaces in biomedical applications, Procedia CIRP. 65 (2017) 284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2017.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang Y, Overview: Damage resistance of graded ceramic restorative materials., J. Eur. Ceram. Soc 32 (2012) 2623–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bona A. Della, Pecho OE, Alessandretti R, Zirconia as a Dental Biomaterial, Materials (Basel). 8 (2015) 4978–4991. doi: 10.3390/ma8084978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scarano A, Di Carlo F, Quaranta M, Piattelli A, Bone Response to Zirconia Ceramic Implants: An Experimental Study in Rabbits, J. Oral Implantol 29 (2003) 8–12. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rupp F, Liang L, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Scheideler L, Hüttig F, Surface characteristics of dental implants: A review, Dent. Mater 34 (2018) 40–57. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kohal RJ, Schwindling FS, Bächle M, Spies BC, Peri-implant bone response to retrieved human zirconia oral implants after a 4-year loading period: A histologic and histomorphometric evaluation of 22 cases, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 104 (2016) 1622–1631. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Depprich R, Zipprich H, Ommerborn M, Naujoks C, Wiesmann H-P, Kiattavorncharoen S, Lauer H-C, Meyer U, Kübler NR, Handschel J, Osseointegration of zirconia implants compared with titanium: an in vivo study, Head Face Med 4 (2008). doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-4-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gahlert M, Roehling S, Sprecher CM, Kniha H, Milz S, Bormann K, In vivo performance of zirconia and titanium implants : a histomorphometric study in mini pig maxillae, Clin. Oral Implants Res 23 (2011) 281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kubasiewicz-Ross P, Hadzik J, Dominiak M, Osseointegration of zirconia implants with 3 varying surface textures and a titanium implant: A histological and micro-CT study., Adv. Clin. Exp. Med (2018). doi: 10.17219/acem/69246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mostafa D, Aboushelib M, Bioactive – hybrid – zirconia implant surface for enhancing osseointegration : an in vivo study, Int. J. Implant Dent 4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kohal RJ, Weng D, Bächle M, Strub JR, Loaded Custom-Made Zirconia and Titanium Implants Show Similar Osseointegration: An Animal Experiment, J. Periodontol 75 (2004) 1262–1268. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.9.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Albrektsson T, Hansson H, Ivarsson B, Interface analysis of titanium and zirconium bone implants, Biomaterials. 6 (1985) 97–101. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(85)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dubruille JH, Viguier E, Le Naour G, Dubruille MT, Auriol M, Le Charpentier Y, Evaluation of combinations of titanium, zirconia, and alumina implants with 2 bone fillers in the dog., Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 14 (1999) 271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Karoussis IK, Salvi GE, Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Bragger U, Hämmerle CHF, Lang NP, Long-term implant prognosis in patients with and without a history of chronic periodontitis: a 10-year prospective cohort study of the ITI Dental Implant System., Clin. Oral Implants Res 14 (2003) 329–339. doi:934 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mareci D, Trincă LC, Căilean D, Souto RM, Corrosion resistance of ZrTi alloys with hydroxyapatite-zirconia-silver layer in simulated physiological solution containing proteins for biomaterial applications, Appl. Surf. Sci 389 (2016) 1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Han J, Hong G, Lin H, Shimizu Y, Wu Y, Zheng G, Zhang H, Sasaki K, Biomechanical and histological evaluation of the osseointegration capacity of two types of zirconia implant, Int. J. Nanomedicine Volume 11 (2016) 6507–6516. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S119519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Albrektsson T, Wennerberg A, Oral implant surfaces: Part 1--review focusing on topographic and chemical properties of different surfaces and in vivo responses to them., Int. J. Prosthodont 17 (2004) 536–543. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Han JM; Hong G; Matsui H; Shimizu Y; Zheng G; Lin H; Sasaki K, The surface characterization and bioactivity of NANOZR in vitro., Dent Mater J. 33 (2014) 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bosshardt DD, Chappuis V, Buser D, Osseointegration of titanium, titanium alloy and zirconia dental implants: current knowledge and open questions, Periodontol. 2000 73 (2017) 22–40. doi: 10.1111/prd.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brånemark PI, Adell R, Breine U, Hansson BO, Lindström J, Ohlsson A, Intra-osseous anchorage of dental prostheses. I. Experimental studies., Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 3 (1969) 81–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manzano G, Herrero LR, Montero J, Comparison of Clinical Performance of Zirconia Implants and Titanium Implants in Animal Models: A Systematic Review, Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 29 (2014) 311–320. doi: 10.11607/jomi.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Scarano A, Piattelli M, Caputi S, Favero GA, Piattelli A, Bacterial Adhesion on Commercially Pure Titanium and Zirconium Oxide Disks: An In Vivo Human Study, J. Periodontol 75 (2004) 292–296. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Roehling S, Astasov-Frauenhoffer M, Hauser-Gerspach I, Braissant O, Woelfler H, Waltimo T, Kniha H, Gahlert M, In Vitro Biofilm Formation on Titanium and Zirconia Implant Surfaces, J. Periodontol 88 (2017) 298–307. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pardun Karoline, 1, Treccani Laura, 1, Volkmann Eike, 1, Streckbein Philipp, 2, Heiss Christian, 4 3, Gerlach Juergen W, 5, Maendl Stephan, 5, and Rezwan Kurosch, Magnesium-containing mixed coatings on zirconia for dental implants: mechanical characterization and in vitro behavior, (n.d.). http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0885328215572428 (accessed September 11, 2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [27].Bacchelli B, Giavaresi G, Franchi M, Martini D, De Pasquale V, Trirè A, Fini M, Giardino R, Ruggeri A, Influence of a zirconia sandblasting treated surface on peri-implant bone healing: An experimental study in sheep, Acta Biomater. 5 (2009) 2246–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moura CG, Pereira R, Buciumeanu M, Carvalho O, Bartolomeu F, Nascimento R, Silva FS, Effect of laser surface texturing on primary stability and surface properties of zirconia implants, Ceram. Int (2017) 0–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.08.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sanon C, Chevalier J, Douillard T, Cattani-Lorente M, Scherrer SS, Gremillard L, A new testing protocol for zirconia dental implants, Dent. Mater 31 (2015) 15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Altmann B, Rabel K, Kohal RJ, Proksch S, Tomakidi P, Adolfsson E, Bernsmann F, Palmero P, Fürderer T, Steinberg T, Cellular transcriptional response to zirconia-based implant materials, Dent. Mater 33 (2017) 241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Coelho PG, Jimbo R, Tovar N, Bonfante EA, Osseointegration: Hierarchical designing encompassing the macrometer, micrometer, and nanometer length scales, Dent. Mater 31 (2015) 37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu M, Zhou J, Yang Y, Zheng M, Yang J, Tan J, Surface modification of zirconia with polydopamine to enhance fibroblast response and decrease bacterial activity in vitro: A potential technique for soft tissue engineering applications, 136 (2015) 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gahlert M, Gudehus T, Eichhorn S, Steinhauser E, Kniha H, Erhardt W, Biomechanical and histomorphometric comparison between zirconia implants with varying surface textures and a titanium implant in the maxilla of miniature pigs, Clin. Oral Implants Res 18 (2007) 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Flamant Q, Marro F. García, Rovira J.J. Roa, Anglada M, Hydrofluoric acid etching of dental zirconia. Part 1: Etching mechanism and surface characterization, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc 36 (2016) 121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Laranjeira MS, Carvalho Â, Pelaez-Vargas A, Hansford D, Ferraz MP, Coimbra S, Costa E, Santos-Silva A, Fernandes MH, Monteiro FJ, Modulation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cell and human gingival fibroblast behavior by micropatterned silica coating surfaces for zirconia dental implant applications., Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 15 (2014) 025001. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/15/2/025001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pardun K, Treccani L, Volkmann E, Streckbein P, Heiss C, Gerlach JW, Maendl S, Rezwan K, Magnesium-containing mixed coatings on zirconia for dental implants: mechanical characterization and in vitro behavior., J. Biomater. Appl 30 (2015) 104–18. doi: 10.1177/0885328215572428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li H, Xie Y, Li K, Huang L, Huang S, Zhao B, Microstructure and wear behavior of graphene nanosheets-reinforced zirconia coating, Ceram. Int 40 (2014) 12821–12829. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.04.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liu M, Zhou J, Yang Y, Zheng M, Yang J, Tan J, Colloids and Surfaces B : Biointerfaces Surface modification of zirconia with polydopamine to enhance fibroblast response and decrease bacterial activity in vitro : A potential technique for soft tissue engineering applications, 136 (2015) 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hafezeqoran A, Koodaryan R, Effect of Zirconia Dental Implant Surfaces on Bone Integration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Biomed Res. Int 2017 (2017). doi: 10.1155/2017/9246721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thoma DS, Benic GI, Muñoz F, Kohal R, Martin I. Sanz, Cantalapiedra AG, Hämmerle CHF, Jung RE, Histological analysis of loaded zirconia and titanium dental implants: an experimental study in the dog mandible, J. Clin. Periodontol 42 (2015) 967–975. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kim H, Shon W, Ahn J, Cha S, Park Y, Sciences MD, Comparison of peri-implant bone formation around injection- molded and machined surface zirconia implants in rabbit tibiae, Dent. Mater. J 34 (2017) 508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Aboushelib MN, Salem NA, El Moneim NMA, Influence of Surface Nano-Roughness on Osseointegration of Zirconia Implants in Rabbit Femur Heads Using Selective Infiltration Etching Technique, J. Oral Implantol 39 (2013) 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hoffmann O, Angelov N, Zafiropoulos G-G, Andreana S, Osseointegration of zirconia implants with different surface characteristics: an evaluation in rabbits., Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 27 (2012) 352–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Koch FP, Weng D, Krämer S, Biesterfeld S, Jahn-Eimermacher A, Wagner W, Osseointegration of one-Piece zirconia implants compared with a titanium implant of identical design: A histomorphometric study in the dog, Clin. Oral Implants Res 21 (2010) 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Montero J, Bravo M, Guadilla Y, Portillo M, Blanco L, Rojo R, Rosales-Leal I, López-Valverde A, Comparison of Clinical and Histologic Outcomes of Zirconia Versus Titanium Implants Placed in Fresh Sockets: A 5-Month Study in Beagles, Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 30 (2015) 773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schliephake H, Hefti T, Schlottig F, Gédet P, Staedt H, Mechanical anchorage and peri-implant bone formation of surface-modified zirconia in minipigs, J. Clin. Periodontol 37 (2010) 818–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Linares A, Grize L, Muñoz F, Pippenger BE, Dard M, Domken O, Blanco-Carrión J, Histological assessment of hard and soft tissues surrounding a novel ceramic implant: A pilot study in the minipig, J. Clin. Periodontol 43 (2016) 538–546. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Janner SFM, Gahlert M, Bosshardt DD, Roehling S, Milz S, Higginbottom F, Buser D, Cochran DL, Bone response to functionally loaded, two-piece zirconia implants: A preclinical histometric study, Clin. Oral Implants Res 29 (2018) 277–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Calvo-guirado L, Gargallo-albiol J, Delgado-ruiz RA, Satorres-nieto M, Zirconia with laser-modified micro- grooved surface vs. titanium implants covered with melatonin stimulates bone formation. Experimental study in tibia rabbits, Clin. Oral Implants Res 26 (2015) 1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/clr.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Delgado-Ruiz RA, Abboud M, Romanos G, Aguilar-Salvatierra A, Gomez-Moreno G, Calvo-Guirado JL, Peri-implant bone organization surrounding zirconia-microgrooved surfaces circularly polarized light and confocal laser scanning microscopy study, Clin. Oral Implants Res 26 (2015) 1328–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Delgado-ruiz RA, Calvo-guirado JL, Histologic and Histomorphometric Behavior of Microgrooved Zirconia Dental Implants with, Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res 16 (2014) 856–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Calvo-Guirado JL, Aguilar-Salvatierra A, Gomez-Moreno G, Guardia J, Delgado-Ruiz RA, de Val J.E. Mate-Sanchez, Histological, radiological and histomorphometric evaluation of immediate vs. non-immediate loading of a zirconia implant with surface treatment in a dog model, Clin. Oral Implants Res 25 (2014) 826–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Brezavšček M, Fawzy A, Bächle M, Tuna T, Fischer J, Att W, The Effect of UV Treatment on the Osteoconductive Capacity of Zirconia-Based Materials., Mater. (Basel, Switzerland) 9 (2016). doi: 10.3390/ma9120958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fischer J, Schott A, Märtin S, Surface micro-structuring of zirconia dental implants, Clin. Oral Implants Res. 27 (2016) 162–166. doi: 10.1111/clr.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xie H, Shen S, Qian M, Zhang F, Chen C, Tay FR, Effects of Acid Treatment on Dental Zirconia: An In Vitro Study, PLoS One. 10 (2015) e0136263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gahlert M, Röhling S, Wieland M, Eichhorn S, Küchenhoff H, Kniha H, A Comparison Study of the Osseointegration of Zirconia and Titanium Dental Implants. A Biomechanical Evaluation in the Maxilla of Pigs, Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res 12 (2010) 297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2009.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vu VT, Oh G-J, Yun K-D, Lim H-P, Kim J-W, Nguyen TPT, Park S-W, Acid etching of glass-infiltrated zirconia and its biological response, J. Adv. Prosthodont 9 (2017) 104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Thompson JY, Stoner BR, Piascik JR, Smith R, Adhesion/cementation to zirconia and other non-silicate ceramics: Where are we now?, Dent. Mater 27 (2011) 71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cooper LF, Zhou Y, Takebe J, Guo J, Abron A, Holm??n A, Ellingsen JE, Fluoride modification effects on osteoblast behavior and bone formation at TiO2 grit-blasted c.p. titanium endosseous implants, Biomaterials. 27 (2006) 926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Oliva J, Oliva X, Oliva JD, Five-year success rate of 831 consecutively placed Zirconia dental implants in humans: a comparison of three different rough surfaces., Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 25 (2010) 336–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Oh G, Yoon J, Vu VT, Ji M, Kim J, Kim J, Yim E, Bae J, Park C, Yun K, Lim H, Park S, Fisher JG, Surface Characteristics of Bioactive Glass-Infiltrated Zirconia with Different Hydrofluoric Acid Etching Conditions, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 17 (2017) 2645–2648. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2017.13323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hempel U, Hefti T, Kalbacova M, Wolf-Brandstetter C, Dieter P, Schlottig F, Response of osteoblast-like SAOS-2 cells to zirconia ceramics with different surface topographies, Clin. Oral Implants Res 21 (2010) 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bergemann C, Duske K, Nebe JB, Schöne A, Bulnheim U, Seitz H, Fischer J, Microstructured zirconia surfaces modulate osteogenic marker genes in human primary osteoblasts., J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 26 (2015) 5350. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5350-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wennerberg A, Albrektsson T, Effects of titanium surface topography on bone integration: a systematic review, Clin. Oral Implants Res 20 (2009) 172–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Saulacic N, Erdösi R, Bosshardt DD, Gruber R, Buser D, Acid and Alkaline Etching of Sandblasted Zirconia Implants: A Histomorphometric Study in Miniature Pigs, Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res 16 (2014) 313–322. doi: 10.1111/cid.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhang Y, Lawn BR, Malament KA, Van Thompson P, Rekow ED, Damage accumulation and fatigue life of particle-abraded ceramics., Int. J. Prosthodont 19 (n.d.) 442–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17323721 (accessed November 14, 2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Aurélio IL, Marchionatti AME, Montagner AF, May LG, Soares FZM, Does air particle abrasion affect the flexural strength and phase transformation of Y-TZP? A systematic review and meta-analysis, Dent. Mater. 32 (2016) 827–845. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pereira GKR, Guilardi LF, Dapieve KS, Kleverlaan CJ, Rippe MP, Valandro LF, Mechanical reliability, fatigue strength and survival analysis of new polycrystalline translucent zirconia ceramics for monolithic restorations, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 85 (2018) 57–65. doi: 10.1016/J.JMBBM.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Sriamporn T, Thamrongananskul N, Busabok C, Poolthong S, Uo M, Tagami J, Dental zirconia can be etched by hydrofluoric acid., Dent. Mater. J 33 (2014) 79–85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24492116 (accessed November 14, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sato H, Yamada K, Pezzotti G, Nawa M, Ban S, Mechanical Properties of Dental Zirconia Ceramics Changed with Sandblasting and Heat Treatment, 2008. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/dmj/27/3/27_3_408/_pdf/-char/en (accessed November 14, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [71].Henningsen A, Smeets R, Heuberger R, Jung OT, Hanken H, Heiland M, Cacaci C, Precht C, Changes in surface characteristics of titanium and zirconia after surface treatment with ultraviolet light or non-thermal plasma, Eur. J. Oral Sci (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Tuna T, Wein M, Altmann B, Steinberg T, Fischer J, Att W, Effect of ultraviolet photofunctionalisation on the cell attractiveness of zirconia implant materials., Eur. Cell. Mater 29 (2015) 82–94; discussion 95–6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25612543 (accessed November 12, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Tuna T, Wein M, Swain M, Fischer J, Att W, Influence of ultraviolet photofunctionalization on the surface characteristics of zirconia-based dental implant materials, Dent. Mater 31 (2015) e14–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Liu D, Matinlinna JP, Tsoi JK-H, Pow EHN, Miyazaki T, Shibata Y, Kan C-W, A new modified laser pretreatment for porcelain zirconia bonding, Dent. Mater 29 (2013) 559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Yang Y, Zhou J, Liu X, Zheng M, Yang J, Tan J, Ultraviolet light-treated zirconia with different roughness affects function of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro: The potential surface modification developed from implant to abutment, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 103 (2015) 116–124. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Parry JP, Shephard JD, Hand DP, Moorhouse C, Jones N, Weston N, Laser micromachining of zirconia (Y-TZP) ceramics in the picosecond regime and the impact on material strength, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol 8 (2011) 163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7402.2009.02420.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hao L, Lawrence J, Chian KS, Osteoblast cell adhesion on a laser modified zirconia based bioceramic, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 16 (2005) 719–726. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-2608-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hotchkiss KM, Reddy GB, Hyzy SL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD, Olivares-Navarrete R, Titanium surface characteristics, including topography and wettability, alter macrophage activation, Acta Biomater. 31 (2016) 425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Al-Radha ASD, Dymock D, Younes C, O’Sullivan D, Surface properties of titanium and zirconia dental implant materials and their effect on bacterial adhesion, J. Dent 40 (2012) 146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cho Y, H. J, Ryoo H, Kim D, Park J, Han J, Osteogenic responses to zirconia with hydroxyapatite coating by aerosol deposition, J. Dent. Res 94 (2015) 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wang G, Meng F, Ding C, Chu PK, Liu X, Microstructure, bioactivity and osteoblast behavior of monoclinic zirconia coating with nanostructured surface, Acta Biomater. 6 (2010) 990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Chen Y, Zheng X, Xie Y, Ding C, Ruan H, Fan C, Anti-bacterial and cytotoxic properties of plasma sprayed silver-containing HA coatings, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 19 (2008) 3603–3609. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Schienle S, Al-Ahmad A, Kohal RJ, Bernsmann F, Adolfsson E, Montanaro L, Palmero P, Fürderer T, Chevalier J, Hellwig E, Karygianni L, Microbial adhesion on novel yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia (Y-TZP) implant surfaces with nitrogen-doped hydrogenated amorphous carbon (a-C:H:N) coatings, Clin. Oral Investig (2015) 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Pardun K, Treccani L, Volkmann E, Streckbein P, Heiss C, Destri GL, Marletta G, Rezwan K, Mixed zirconia calcium phosphate coatings for dental implants: Tailoring coating stability and bioactivity potential, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 48 (2015) 337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Liu YT, Lee TM, Lui TS, Enhanced osteoblastic cell response on zirconia by bio-inspired surface modification, Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 106 (2013) 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Kirsten A, Hausmann A, Weber M, Fischer J, Fischer H, Bioactive and Thermally Compatible Glass Coating on Zirconia Dental Implants, J. Dent. Res 94 (2015) 297–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034514559250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Catauro M, Bollino F, Papale F, Ciprioti S. Vecchio, Investigation on bioactivity, biocompatibility, thermal behavior and antibacterial properties of calcium silicate glass coatings containing Ag, J. Non. Cryst. Solids 422 (2015) 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2015.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Mushahary D, Wen C, Kumar JM, Lin J, Harishankar N, Hodgson P, Pande G, Li Y, Collagen type-I leads to in vivo matrix mineralization and secondary stabilization of Mg–Zr–Ca alloy implants, Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 122 (2014) 719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Ewais EMM, Amin AMM, Ahmed YMZ, Ashor EA, Hess U, Rezwan K, Combined effect of magnesia and zirconia on the bioactivity of calcium silicate ceramics at C\S ratio less than unity, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 70 (2017) 155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Garmendia N, Bilbao L, Muñoz R, Imbuluzqueta G, García A, Bustero I, Calvo-Barrio L, Arbiol J, Obieta I, Zirconia coating of carbon nanotubes by a hydrothermal method., J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 8 (2008) 5678–83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19198288 (accessed November 9, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kou W, Akasaka T, Watari F, Sjögren G, An In Vitro Evaluation of the Biological Effects of Carbon Nanotube-Coated Dental Zirconia, ISRN Dent. 2013 (2013) 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/296727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Reproducibility of ZrO2-based freeze casting for biomaterials, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 61 (2016) 105–112. doi: 10.1016/J.MSEC.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Lavos-Valereto IC, König B, Rossa C, Marcantonio E, Zavaglia AC, A study of histological responses from Ti-6Al-7Nb alloy dental implants with and without plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coating in dogs., J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 12 (2001) 273–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Aboushelib MN, Shawky R, Osteogenesis ability of CAD/CAM porous zirconia scaffolds enriched with nano-hydroxyapatite particles, Int. J. Implant Dent 3 (2017) 21. doi: 10.1186/s40729-017-0082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Le Ray A, Gautier H, Bouler J, Weiss P, Merle C, A new technological procedure using sucrose as porogen compound to manufacture porous biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics of appropriate micro- and macrostructure, 36 (2010) 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2009.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Yang J, Sultana R, Ichim P, Hu X, Huang Z, Micro-porous calcium phosphate coatings on load-bearing zirconia substrate : Processing, property and application, Ceram. Int 39 (2013) 6533–6542. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.01.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB, Mussel-Inspired Surface Chemistry for Multifunctional Coatings, 318 (2008) 426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241.Mussel-Inspired. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Xu M, Zhai D, Xia L, Li H, Chen S, Fang B, Chang J, Wu C, Hierarchical bioceramic scaffolds with 3D-plotted macropores and mussel-inspired surface nanolayers, Nanoscale. 12 (2016) 13790–13803. doi: 10.1039/c6nr01952h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Liu Y, Lee T, Lui T, Colloids and Surfaces B : Biointerfaces Enhanced osteoblastic cell response on zirconia by bio-inspired surface modification, Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 106 (2013) 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Priyadarsini S, Mukherjee S, Mishra M, Nanoparticles used in dentistry: A review., J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res 8 (2018) 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Xie Y, Li H, Ding C, Zheng X, Li K, Effects of graphene plates’ adoption on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and in vivo biocompatibility of calcium silicate coating., Int. J. Nanomedicine 10 (2015) 3855–63. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S77919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Cho BH, Ko WB, Preparation of graphene-ZrO2 nanocomposites by heat treatment and photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes., J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 13 (2013) 7625–30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24245304 (accessed November 7, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Ferraris S, Miola M, Surface modification of bioactive glasses, in: Surf. Tailoring Inorg. Mater. Biomed. Appl, Bentham Science Publishers Ltd., Applied Science and Technology Department - DISAT, Politecnico di Torino, C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129, Torino, Italy, 2012: pp. 392–405. doi: 10.2174/978160805462611201010392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Zhang Y, Kim JW, Graded zirconia glass for resistance to veneer fracture., J. Dent. Res 89 (2010) 1057–62. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Zhang Y, Legeros R, Kim J, US8703294 B2 - Bioactive graded zirconia-based structures, 2014.

- [106].Zhang Y, Kim J, Thompson VP, US7858192 B2 - Graded glass/ceramic/glass structures for damage resistant ceramic dental and orthopedic prostheses, 2010.

- [107].Fabris D, Souza JCM, Silva FS, Fredel M, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Zhang Y, Henriques B, Thermal residual stresses in bilayered, trilayered and graded dental ceramics, Ceram. Int 43 (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Fabris D, Souza JCM, Silva FS, Fredel M, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Zhang Y, Henriques B, The bending stress distribution in bilayered and graded zirconia-based dental ceramics, Ceram. Int 42 (2016) 11025–11031. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.03.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Henriques B, Fabris D, Souza JCM, Silva FS, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Zhang Y, Fredel M, Influence of interlayer design on residual thermal stresses in trilayered and graded all-ceramic restorations, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 71 (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Zhang Y, Chai H, Lawn BR, Graded structures for all-ceramic restorations., J. Dent. Res (2010). doi: 10.1177/0022034510363245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Zhang Y, Sun M-J, Zhang D, Designing functionally graded materials with superior load-bearing properties., Acta Biomater. 8 (2012) 1101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Kim JW, Liu L, Zhang Y, Improving the resistance to sliding contact damage of zirconia using elastic gradients, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 94 (2010) 347–352. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Zhang Y, Kim J, Graded structures for damage resistant and aesthetic all-ceramic restorations, Dent. Mater 25 (2009) 781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Zhang Y, Ma L, Optimization of ceramic strength using elastic gradients, Acta Mater. 57 (2009) 2721–2729. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Mihatovic I, Golubovic V, Becker J, Schwarz F, Bone tissue response to experimental zirconia implants, Clin. Oral Investig 21 (2017) 523–532. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Kohal R-J, Patzelt SBM, Butz F, Sahlin H, One-piece zirconia oral implants: one-year results from a prospective case series. 2. Three-unit fixed dental prosthesis (FDP) reconstruction, J. Clin. Periodontol 40 (2013) 553–562. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]