Summary

Migraine is an extremely common but poorly understood nervous system disorder. We conceptualize migraine as a disorder of sensory network gain and plasticity, and we propose that this framing makes it amenable to the tools of current systems neuroscience.

Introduction: considering migraine as a systems neuroscience problem

Two characteristics of migraine make it a very interesting systems neuroscience problem. First, the migraine attack is not only an anatomically specific pain state, but also - at least phenotypically - it is a paroxysmal disorder of pan-sensory gain. Second, the transition from acute to chronic migraine appears to represent a multi-site, dysfunctional plasticity of sensory, autonomic, and affective circuits.

In order to understand the migraine attack from a systems neuroscience perspective, we need to understand how a sensory and autonomic network can switch, within a few minutes, from a state of relative equilibrium to one in which there is both spontaneous pain and amplification of percepts from multiple senses. We also need to understand how the sensory changes that occur in a migraine attack become a near constant experience in chronic migraine.

Because migraine is a whole nervous system disease, any attempt to summarize it entirely can be daunting. Though we refer to the clinical migraine literature as a reference point, our primary focus is on how the disease (in particular the migraine attack and chronic migraine) can be approached mechanistically in animal model systems. Our overall goal is to increase awareness of this under-studied disease in the neuroscientfic community, by trying to view it through the lens of modern systems neuroscience. Finally, we apologize in advance for citing only selected original research and reviews, rather than the more extensive primary literature.

Characteristics of migraine

Migraine affects 12% of the world population(Jensen and Stovner, 2008; Lipton et al., 2007). It is commonly thought of as a disorder of episodic, severe headache, but this understates both its pathophysiological complexity and its human impact. Migraine attacks are often incapacitating, and they primarily affect people in their working and child-rearing years. Chronic migraine - migraine more than 15 days of the month - affects 2% of the world population(May and Schulte, 2016). The economic costs of migraine, driven mainly by chronic migraine, range between $20 and $30 billion a year in the US(Stewart et al., 2003). The true societal costs of this stigmatized, poorly understood disease are hard to calculate.

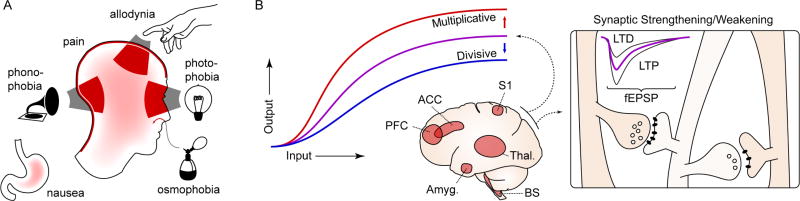

Migraine is a disorder primarily affecting the sensory nervous system(Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2013). It is punctuated by attacks, which generally last a few hours, and include a throbbing, unilateral head pain that can range from mild to excruciating. However the headache is only one element of a larger whole. In addition to head pain, there is often pain in the neck and shoulders. Nausea and vomiting, representing interoception and autonomic outflow from the gut, are prominent features. There can also be autonomic phenomena in the face, typically reddening of the eyes, tearing, flushing or pallor(Goadsby et al., 2002). Finally, the majority of migraine attacks feature sensory amplifications: photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, and cutaneous allodynia – the perception of light, sound, smell and normal touch as amplified or painful(Burstein et al., 2015). Thus, the migraine attack is not so much a simple headache as it is a paroxysmal alteration in gain, or input-output modulation (Haider and McCormick, 2009), of multiple sensory systems (Figure 1).

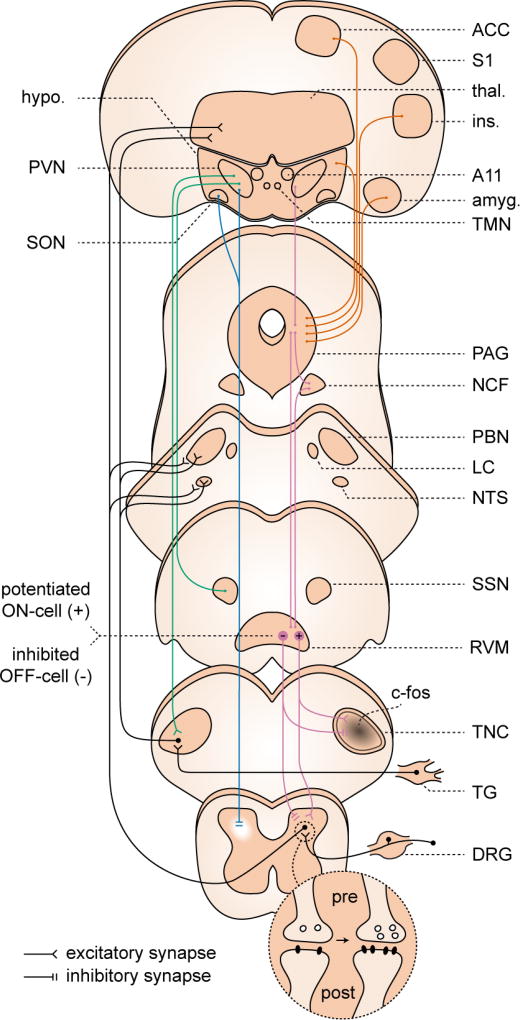

Figure 1. Characteristics of migraine.

A. The migraine attack involves changes in multiple sensory percepts. Head and neck pain are the prototypic features, but migraine attacks are nearly always accompanied by some combination of photophobia, phonophobia, and/or allodynia (the perception of light, sound, and touch as painful, respectively). Osmophobia - a heightened, often aversive sensitivity to smell - is another frequent feature. Finally, nausea - an aversive viscerosensation - affects most migraineurs during an attack. These changes can become constant in chronic migraine. B. Conceptualizing migraine as a short- and long-term disruption of network gain. Widely distributed sensory, homeostatic/autonomic, and affective networks are likely involved. The amplitude (or salience) of percepts to the same stimulus is increased, potentially consistent with a change in circuit gain. These changes are temporary when associated with the migraine attack, but in chronic migraine they can be constant, suggesting entrainment of plasticity processes. PFC: prefrontal cortex; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; S1: primary sensory cortex; Thal.: thalamus; Amyg.: amygdala; BS: brain stem nuclei; LTP, LTD: long term potentiation, depression; fEPSP: field excitatory postsynaptic potential.

The migraine attack is the most visible element of a larger disease continuum. In up to a third of patients, the attack is heralded by an aura: this is a typically sensory hallucination, with visual or somatic percepts that do not exist in the environment. It can also affect speech function, indistinguishably from the aphasia seen in stroke, except that it is reversible. Up to 72 hours before an attack, some patients experience premonitory symptoms - cognitive changes, hunger/thirst, euphoria or irritability. Following the attack, sensory function typically does not immediately return to normal: milder pain and sensory amplifications can persist for hours to days(Goadsby et al., 2002; Olesen et al., 2013).

Between attacks, there are alterations in sensory physiology that appear to vary in time with the attack profile, suggesting an underlying cyclicity in sensory gain that culminates in the attack (de Tommaso et al., 2014). One of the most important problems in clinical migraine is the progression from an intermittent, self-limited inconvenience to a life-changing disorder of chronic pain, sensory amplification, and autonomic and affective disruption. This progression, sometimes termed chronification in the migraine literature, is common, affecting 3% of migraineurs in a given year, such that 8% of migraineurs have chronic migraine in any given year(May and Schulte, 2016). The chronification process results in a persistent alteration in the way the sensory network responds to the environment; that is, at least phenomenologically, a dysfunctional plasticity of the sensory network.

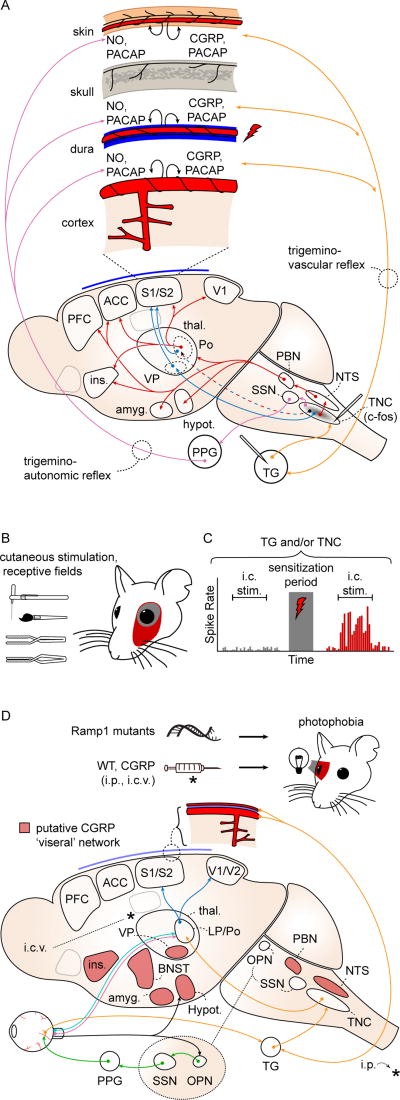

Migraine-relevant pain networks

Craniofacial nociceptive afferents have their cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglion (TG), and the dorsal root ganglia of cervical roots C1–3. Like nociceptive afferents in the rest of the body, they are thinly myelinated A delta or unmyelinated C fibers, often immunoreactive for calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) and substance P. Their central processes terminate in the trigeminocervical complex, which includes the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (TNC) and dorsal horn of the first cervical segments, and is the first central nervous system relay in the craniofacial nociceptive circuit. For simplicity we will use the term TNC to refer to all trigeminocervical complex structures. TNC neurons send glutamatergic processes to the ventroposteriomedial (VPM) and posterior (Po) nuclei of the thalamus; VPM neurons project primarily to somatosensory cortex while Po neurons project more broadly, including sensory cortices, insula, and association cortex. TNC neurons also connect to affective/motivational circuits through the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and parabrachial nucleus (PBN), which send projections diffusely to hypothalamus, thalamic nuclei, amygdala, insular cortex, and frontal cortex. Finally TNC neurons project directly to output structures effecting pain modulation and autonomic outflow: hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray, superior salivatory nucleus, and rostral ventromedial medulla (Reviewed in Noseda and Burstein, 2013; Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2013) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Migraine relevant pain and photophobia networks in animal models.

A. Craniofacial structures are innervated by nociceptors whose cell bodies are in the trigeminal ganglion (TG) and dorsal root ganglia of C1–3 (orange arrows; C1–3 not shown). The first central relay for craniofacial nociception is the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC). TNC projects, directly and indirectly, to structures involved in the sensory/discriminative (blue arrows) and affective/motivational (red arrows) aspects of the pain percept. The trigeminovascular (orange arrows) and trigemino-autonomic (purple arrows) reflexes are activated by stimulation of nociceptive afferents (red lightning bolt), causing release of peptides and nitric oxide (black curved arrows) and generating a sustained nociceptive response that is used to model a migraine attack. ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; Amyg: amygdala; CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide; Hypot: hypothalamus; Ins: insula; NO: nitric oxide; NTS: nucleus tractus solitarius; PACAP: pituitary adenylate cyclase activated peptide; PBN: parabrachial nucleus; PFC: prefrontal cortex; Po: posterior nucleus of thalamus; S1/S2: primary, secondary somatosensory cortices; SSN: superior salivatory nucleus; Thal: thalamus; VP: ventroposterior nuclei of thalamus. B. Activation of craniofacial afferents results in persistent sensitization to sensory stimulation via von Frey filament, brush, pressure, or pinch; and expansion of cutaneous receptive fields (red) after application of intracranial inflammatory mediators. C. Schematized trigeminal ganglion or trigeminal nucleus caudalis neuron response to intracranial stimulation. Mechanosensive afferents show a potentiated response consistent with mechanical intracranial hypersensitivity after application of intracranial inflammatory mediators. D. Photophobia circuits. The photophobia that accompanies the migraine attack has been modeled in animals. Retinal ganglion cells project to the olivary pretectal nucleus (OPN; black arrows). OPN projections activate superior salivatory nucleus (SSN), which via the pterygopalatine ganglion (PPG; green), cause ocular vasodilation and activation of trigeminal afferents (orange) which densely innervate ocular blood vessels. These afferents, with cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglion, project to TNC, thalamus and cortex. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (IPRGCs; pink) and cone cell-associated retinal ganglion cells (light blue) project directly to posterior thalamic neurons (primarily in lateral posterior and posterior nuclei; LP, Po) that also receive intracranial nociceptive afferents (orange). Retinal ganglion cells also project to hypothalamus (black). Posterior thalamic neurons fire in response to both light and pain stimuli, and their output projects diffusely to sensory and association cortices (dark blue; association cortex not shown). CGRP-overexpressing mice (Ramp1 mutants) are photophobic compared to littermates, and both intraperitoneal (i.p.) and intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) CGRP injections cause photophobia in wild type mice. Red shading: putative CGRP 'visceral network.' BNST: bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. References in text.

In summary, craniofacial afferents that synapse in the TNC project, directly or indirectly, to structures involved in the sensory/discriminatory, salience/alerting, and affective/motivational aspects of pain, as well as to structures involved in the response to pain – reflex autonomic and descending facilitatory/inhibitory modulation. For historical reasons, craniofacial pain circuits have acquired a distinct nomenclature: the term trigeminovascular reflex (and the related trigemino-autonomic reflex) arose because it was noted that activation of craniofacial nociceptive afferents resulted in vasodilation and inflammatory mediator release over the dura(Moskowitz, 1984). This process of nociception-related reflex outflow was important in the development migraine-relevant pain models (Figure 2a). However in its essence the trigeminovascular response resembles the neurogenic inflammation(Xanthos and Sandkühler, 2014), seen on activation of pain afferents throughout the body.

Altered network gain and plasticity in models of the migraine attack

It is unclear how a typical migraine attack is triggered - this is one of the most important unanswered questions in migraine neuroscience. It is likely that the triggers vary between and within subjects(Kelman, 2007), depending on pre-existing network characteristics that might be quite individual. When designing animal models it is important to consider that, whatever the trigger, it should result in a sustained, self-perpetuating response, comparable in duration to a migraine attack, and incorporating all of its features, including pain, autonomic outflow, and sensory amplifications. At this point it is not known whether any migraine model fully meets these criteria.

Inflammatory and nociceptive mediators generate potentiation-like activity in pain relays

The primary approaches to modeling the craniofacial nociceptive response involve stimulation and recording of trigeminal afferents – these are called trigeminovascular models in the migraine literature(Moskowitz, 1984; Noseda and Burstein, 2013) (Figure 2a,b,c). A typical preparation involves applying either electrical stimulation or inflammatory mediators (usually a combination of potassium, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, ATP, and low pH), to pain-sensitive intractranial structures (e.g. dural sinus or middle meningeal artery; both are densely innervated with trigeminal afferents). After stimulation, the response to innocuous and noxious extra- and intracranial stimulation is measured with electrophysiology or imaging, with the rationale that sensitization of these responses is representative of the migraine headache state (Romero-Reyes and Akerman, 2014). More recently, substances known to induce migraine in humans, including nitroglycerin (NTG), CGRP, and others, have been applied in trigeminovascular models, to increase translational relevance (Ashina et al., 2017; Romero-Reyes and Akerman, 2014).

Most trigeminovascular models show either persistent increases in TG and TNC firing, c-fos immediate early gene activation, or both, after stimulation(Noseda and Burstein, 2013; Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2013; Romero-Reyes and Akerman, 2014)(Figure 2a,b,c). The findings are similar to what is seen in non-headache pain models: an increase in response to both nociceptive and non-nociceptive stimuli that persists beyond the sensitization protocol. In inflammatory and injury-based pain models (e.g. carrageenan paw injection, sciatic nerve ligation) this kind of change in response properties is associated with long-term potentiation (LTP; a persistent strengthening of synaptic activity) in dorsal horn principal cells(Kuner and Flor, 2016; Sandkühler and Gruber-Schoffnegger, 2012). As the TNC is functionally continuous with the dorsal horn of spinal cord, similar plastic changes might be expected, but they remain to be demonstrated.

Altered behavior and network gain in models of allodynia and photophobia

Trigeminovascular models have been used to explore allodynia, one of the sensory amplifications of migraine (Figures 1,2). Cutaneous allodynia is seen in approximately two thirds of migraine attacks in humans(Lipton et al., 2008): it is most prominent on the side of the head where pain is most severe; however spread of allodynia to the contralateral head, to ipsilateral and contralateral arms, and even to the legs can occur. These sensory findings have been replicated in animal models, and are used as evidence for central sensitization. The rationale is that while hyperalgesia in the same territory as the head pain could be caused by peripheral sensitization (an increase in the firing rate of peripheral nociceptors to a given stimulus), allodynia (a pain response generated by light touch) cannot be explained without central nervous system modulation (Noseda and Burstein, 2013). Both peripheral and central sensitization are phenotypes that, in non-headache pain models, are associated with synaptic plasticity (Costigan et al., 2009). However the underlying mechanisms have not been investigated in migraine models.

Another sensory amplification that has been explored in migraine-focused models is photophobia (Figure 2d). Several migraine-relevant interventions, including NTG, CGRP infusion, and mice engineered to overexpress CGRP receptors, generate photophobic behavior in mice during light/dark box testing (Kaiser et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2017; Recober et al., 2009; Sufka et al., 2016). As photophobia is a sustained sensory amplification, it is reasonable to hypothesize that like allodynia it reflects an underlying gain or plasticity process. While this has not been explicitly tested, the neural circuitry underlying the phenomenon has been examined. Two potentially interacting circuits may both be associated with photophobia(reviewed in Digre and Brennan, 2012): 1. retinal ganglion cells project to the olivary pretectal nucleus, which in turn projects to the superior salivatory nucleus, mediating parasympathetic outflow and dilation of intra-ocular arterioles that are densely innervated with trigeminal afferents(Okamoto et al., 2010). 2. light-sensitive neurons in the posterior thalamus (mostly in the lateral posterior and posterior nuclei; LP, Po) receive monosynaptic, convergent input from retinal ganglion cells and trigeminal afferents in the dura, and send projections to several cortical areas including primary and secondary visual cortex (V1, V2) (Noseda et al., 2010a, 2016). The elucidation of specific circuitry allows hypothesis testing on whether the percept of photophobia results from synaptic plasticity, and if so from what synapse in the circuit.

Infusion of CGRP in humans triggers migraine in migraineurs but not normal subjects(Ashina et al., 2017), and CGRP antagonists are a major new class of drugs currently in development for migraine(Russo, 2015). Mice overexpressing the CGRP receptor subunit RAMP1 have significantly increased photophobia compared to littermates(Kaiser et al., 2012; Recober et al., 2009). Injection of CGRP - either intraperitoneally or in the cerbral ventricles - generates photophobia in wild type mice(Mason et al., 2017). While the response to peripheral injection might be expected due to expression and response patterns in primary nociceptors(Russo, 2015), the response to cerebroventricular injection is more surprising. Interestingly, the CGRP receptor is also expressed in the central nervous system - indeed structures expressing the CGRP receptor are proposed as a 'visceral network' in the brain (de Lacalle and Saper, 2000)(red shading in Figure 2d). This putative network has not been explored in terms of migraine physiology, but it may provide an anatomical framework to test, and might help explain photophobic responses to intracerebral injections where no nociceptive fibers are present.

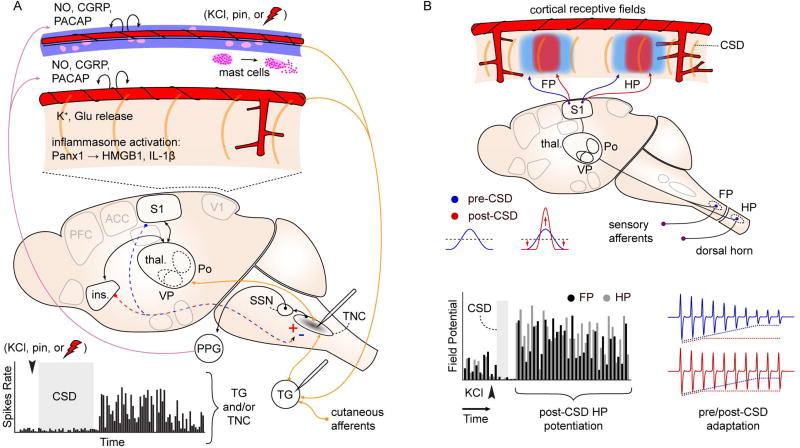

Cortical spreading depression changes the spontaneous firing rate of trigeminal afferents

Cortical spreading depression (CSD), a massive concentric depolarization of neurons, glia, and vessels(Leao, 1944), is now recognized as the phenomenon underlying migraine aura (Charles and Brennan, 2009; Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2014). CSD passes through the cortex, but has network effects that are far-ranging. The massive depolarization of CSD results in a cascade of events at the cortical surface that could trigger trigeminal nociception. Unlike the cortex itself, pial vessels and the dura are innervated with nociceptive afferents. CSD causes neuronal and glial depolarization; initiation of a parenchymal inflammatory cascade triggering release of inflammatory mediators from glia limitans and dural mast cell degranulation; constriction and dilation of surface vessels on which trigeminal afferents are located; and direct depolarization of nociceptive afferents through release of K+ and other mediators into the extracellular space(Charles and Brennan, 2009; Karatas et al., 2013; Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2014). The net result is a minutes-hours increase in the spontaneous firing rate of both TG and TNC neurons(Burstein et al., 2015; Noseda and Burstein, 2013) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Effects of CSD on network activity.

A. Spontaneous firing rate of TG and TNC neurons increases after experimentally-induced CSD (graph at bottom). Recording sites indicated on schematic. c-fos immediate early gene activation is also observed in TNC after CSD (gray shading). These changes are intepreted as consistent with activation of craniofacial nocieptive circuits. Schematic shows possible mechanisms: CSD is associated with release of K+ and glutamate, inflammosome activation (Panx1: neuronal Pannexin-1 receptor activation; HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; Il-1β; interleukin 1-beta), and mast cell degranulation, leading to activation of nociceptive afferents on pial and dural vessels. In addition to direct activation of peripheral nociceptive fibers, CSD can act through central, corticofugal pathways to affect evoked TNC firing. CSD in insula is associated with increased stimulus-evoked TNC firing, while CSD in somatosensory cortex is associated with a decrease (red/blue dashed arrows, +/−). This bi-directional modulation suggests complex effects of CSD on sensory networks. B. CSD alters cortical sensory mapping. Schematic shows sharpening of sensory map generated by potentiation at receptive field center and depression of response in surround regions. Graph: Summed evoked potential responses (sEP) are potentiated at receptive field center for up to 1.5 hrs after CSD passage. FP, HP: forepaw, hindpaw. Red,blue traces: Blunting of sensory adaptation after CSD. References in text.

This minutes-hours duration of increased spontaneous activity suggests either a very long-lasting activation of nociceptive fibers, or a potentiation process. Immediate early genes are used as indicators of LTP(Holtmaat and Caroni, 2016), and c-fos expression is increased in TNC after CSD(Bolay et al., 2002; Moskowitz et al., 1993), likely consistent with potentiation of synapses onto TNC neurons by the event. There is also evidence that CSD can modulate evoked TNC activity after the event, which is also potentially consistent with plasticity induction: CSD depolarizes the whole thickness of the cortex, and corticofugal processes from layer 5 of insula and primary somatosensory cortex (S1) connect directly to TNC. Interestingly, CSD can induce opposite effects on evoked TNC firing, depending on whether it was induced in insula (potentiation) or S1 (suppression) – this bimodal modulation of trigeminal evoked activity is unlikely to have been effected through trigeminal afferents alone(Noseda et al., 2010b) (Figure 3a). In summary, CSD appears sufficient to activate trigeminal nociception, and sustain it for durations consistent with the migraine attack, possibly through plasticity mechanisms within the TNC. Moreover, cortical activity driven by CSD can modulate these TNC effects bidirectionally. However, a direct demonstration of potentiation in the trigeminal dorsal horn – e.g. via generation or occlusion of LTP - has not been performed.

CSD alters cortical sensory mapping

The aura is typically just the beginning of the migraine attack; usually lasting tens of minutes, it is followed by a much longer period of pain and sensory amplification. Beyond the effects of the depolarizing wave, CSD causes persistent changes in cortical function: there is a significant decrease in spontaneous neuronal activity, and a long-lasting depolarization that coincides with cortical hypoperfusion after wave passage(Chang et al., 2010; Lindquist and Shuttleworth, 2017; Piilgaard and Lauritzen, 2009; Sawant-Pokam et al., 2016). The evoked cortical sensory response is also altered during this time period. Both forepaw- and hindpaw-stimulated field potential maps are sharpened after CSD, with receptive field center responses potentiated, and surround responses suppressed. Moreover, there is a significant reduction in adaptation to repetitive sensory stimulation after CSD. All of these responses are long-lasting – persisting ~70 minutes after wave passage(Theriot et al., 2012) (Figure 3b).

The changes in cortical sensory response after CSD are suggestive of known plasticity mechanisms: potentiation and suppression of evoked field potential responses for over an hour could be consistent with LTP and long-term depression (LTD), respectively(Malenka and Bear, 2004). Changes in adaptation are seen during arousal, and represent a mechanism of cortical gain modulation(Castro-Alamancos, 2004). Finally, sensory map sharpening is observed during training and environmental enrichment(Polley et al., 2004). Relevant to migraine, the hypothesis is that CSD-induced sensory map changes contribute to an altered sensory response in the cortices they affect: e.g. photophobia in visual cortex or allodynia in somatosensory cortex. Interestingly, magnetoencephalographic recordings in migraineurs show potentiation of visual evoked responses during attacks(Chen et al., 2011a). Though subjective sensory responses (e.g. photophobia) were not measured, these results clearly suggest that CSD-induced sensory map changes can occur in humans. These combined animal and human data represent a translational opportunity: e.g. to characterize the post-CSD/aura behavioral and physiological response in humans, while determining the mechanisms of the response in animals.

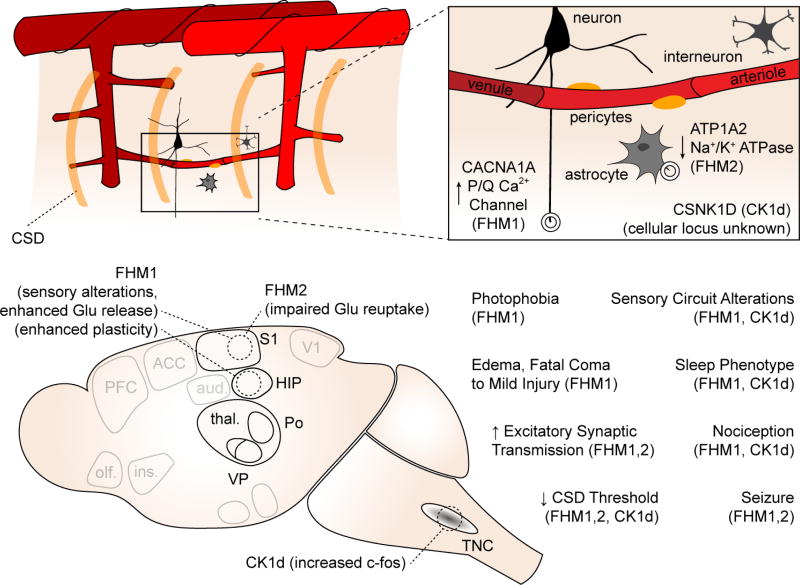

Genetic models of migraine support altered gain and plasticity in sensory and hippocampal circuits

The vast majority of migraineurs likely have a polygenic inheritance(Ferrari et al., 2015). Though genome wide association studies provide increasing insight into the common genetic variants associated with migraine(Gormley et al., 2016), this kind of work does not allow mechanistic dissection. In contrast, much rarer monogenic migraine syndromes can provide such insight because they allow the development of animal models. There are three mouse models expressing genes identified from patients with severe monogenic migraine: familial hemiplegic migraine 1 and 2 (FHM1,2) mice, and casein kinase 1 delta mutant mice; all three show an increased susceptibility to CSD evoked in sensory cortex, and evidence suggesting increased sensory circuit gain(Brennan et al., 2013; Capuani et al., 2016; Chanda et al., 2013; Leo et al., 2011; van den Maagdenberg et al., 2004; Tottene et al., 2009). In FHM1 mice, gain of function of the P/Q Ca++ channel subunit (CaV2.1) results in larger presynaptic calcium currents, and increased synaptic release in pyramidal cells (but not inhibitory interneurons) of the somatosensory cortex, pointing to impaired regulation of cortical excitatory-inhibitory balance. The enhanced glutamate release at cortical excitatory synapses can explain the increased susceptibility to CSD in FHM1 mice (Tottene et al., 2009) (Figure 4). Increased synaptic output selective for excitatory populations also likely has effects on circuit gain and plasticity: hippocampal LTP is enhanced in FHM1 mice, though spatial learning is actually impaired (Dilekoz et al., 2015). And while neuronal calcium responses are attenuated in response to sensory stimulation under anesthesia (Khennouf et al., 2016), behavioral measures of pain and photophobia are increased(Chanda et al., 2013).

Figure 4. Genetic models of migraine and their circuit disruptions.

Top schematic shows genes involved and cellular loci (if known) of gene product. Bottom schematic shows key phenotypes observed in transgenic animals compared to wild type littermates.

FHM2 mice have a loss of function mutation in an astrocytic Na+/K+ ATPase, and reduced rates of K+ and glutamate clearance during neuronal activity(Capuani et al., 2016; Leo et al., 2011). The reduced rate of glutamate clearance contributes to an increased CSD susceptibility (Capuani et al., 2016), but may also lead to altered circuit function and impaired regulation of cortical excitatory-inhibitory balance, e.g. due to differential distribution of the mutant Na+/K+ ATPase near glutamatergic vs GABAergic synapses(Cholet et al., 2002). The actual mechanisms by which the casein kinase 1 delta mutation (CSNK1D) exerts its effects are more obscure; however in addition to CSD susceptibility, mice expressing this mutation show reduced mechanical sensory thresholds, and increased TNC c-fos expression compared to wild type littermates, after treatment with the migraine trigger NTG(Brennan et al., 2013). Thus they show evidence of both cortical excitability and sensitivity of nociceptive circuits (Figure 4). The fact that migraine mutations in CaV2.1 channels, alpha2 Na, K ATPases and casein kinase 1 all lead to facilitation of CSD and hence facilitation of trigeminovascular activation might explain why these widely expressed mutant proteins are specifically involved in migraine headache and not other pain conditions.

Clearly much work remains to be done in the systems biology of all three genetic migraine models - however for all three one predicts circuit dynamics that might contribute to migraine, and two of the three show migraine-relevant pain behaviors. It will be important to clarify what specific synaptic alterations occur, and in which circuits, and to be open to the possibility that gain may be bidirectionally altered: e.g. potentiated glutamatergic synapses contacting interneurons could reduce the gain of affected circuits.

Migraine chronification as a progressive sensory dysplasticity

Along with understanding how the migraine attack starts, understanding how episodic migraine becomes chronic is one of the most important challenges in migraine neuroscience. The vast majority of the clinical, financial, and emotional burden of migraine is from chronic migraine(May and Schulte, 2016). There is also psychophysical and physiological evidence that sensory processing is altered in chronic migraine. For example, cutaneous allodynia is more common as disease duration increases (Lipton et al., 2008), and indeed is associated with chronification(Louter et al., 2013). Visually-evoked magnetoencephalographic potentials show higher amplitudes in chronic migraine(Chen et al., 2011b), and return to sizes seen in episodic migraine when patients are effectively treated(Chen et al., 2012).

From the neuroscientific perspective, understanding how an episodic neurologic disorder becomes chronic (and remits) could offer deep insights into sensory learning and plasticity as well as pain progression. Animal models of chronic migraine provide foundations for mechanistic understanding. Both inflammatory mediators and NTG, when dosed repeatedly over 1–2 weeks, cause long-lasting reductions in mechanical withdrawal threshold, as well as reduced time spent in the light portion of a light/dark box(Oshinsky and Gomonchareonsiri, 2007; Pradhan et al., 2014; Sufka et al., 2016). Importantly, these changes in sensory response persist after the migraine-relevant stimulus has stopped, suggesting that a persistent sensitization has been entrained.

A frequent comorbidity of chronic migraine is medication overuse. This has been modeled with the migraine abortive sumatriptan, which dosed repeatedly over several days causes a reduction in sensory threshold similar to inflammatory mediators and NTG (De Felice et al., 2010). Even after sumatriptan discontinuation and reversion to a normal sensory response, a single dose of sumatriptan is capable of reestablishing the threshold reduction. This is interpreted as a migraine-specific instance of latent sensitization(Marvizon et al., 2015), a phenomenon described in the pain literature. Repetitive dosing of sumatriptan has also been associated with hyperalgesic priming (Araldi et al., 2016), a second messenger-dependent process in which the response to inflammatory mediators is potentiated. Both latent sensitization and hyperalgesic priming could represent plasticity processes in sensory and nociceptive circuits.

Repetitive CSD might be intuitive as a model of chronic migraine with aura. However to our knowledge it has not been pursued. A study focusing on potential harmful long-term effects did induce CSD repetitively over 2 weeks(Sukhotinsky et al., 2011), and interestingly found a decreased susceptibility to CSD over time. However, sensory physiology and behavior were not examined.

Possible loci of circuit modulation in the migraine attack and chronic migraine

As migraine is a disorder of the whole neuraxis, an exhaustive accounting of potential circuits and mechanisms is beyond the scope of this Perspective. We instead focus on regions of particular significance, based on evidence from migraine models, or phenotypes of the disease itself.

Spinal cord and brainstem

Peripheral and central sensitization are implicated in the hyperalgesia and allodynia that accompany migraine (Noseda and Burstein, 2013)(see above). Peripheral and central sensitization are phenomenological terms, originally used to describe findings for which mechanisms were not yet known. Advances in non-migraine pain neuroscience can provide testable mechanisms for the spread of hyperalgesia and allodynia beyond the territory of immediate head pain. Both inflammatory and injury pain models in the limb induce LTP in the dorsal horn(Sandkühler and Gruber-Schoffnegger, 2012), that correlates with hyperalgesia and allodynia (Figure 5). In limb pain models, primary hyperalgesia (amplified pain referable to the stimulated region) has been attributed to homosynaptic LTP (potentiation of the same synapses that were stimulated during LTP induction). Heterosynaptic potentiation (potentiation of non-stimulated synapses on the same cell) occurs in both principal cells and interneurons of the dorsal horn and may account for secondary hyperalgesia (amplified pain outside the stimulated territory) Similar processes may occur in the TNC, though the extent to which they can explain the full range of migraine-associated hyperalgesia and allodynia (e.g. lower limb allodynia from activation of TNC neurons) is debatable.

Figure 5. Circuits of potential relevance to migraine: spinal cord, brainstem, hypothalamus.

Dorsal horn and TNC. Both pre- and post-synaptic forms of LTP have been demonstrated in dorsal horn. These changes have not been conclusively demonstrated in TNC; however c-fos expression, which has been used as a proxy for LTP, has been observed in TNC to migraine-relevant stimuli. Descending modulation from periaqueductal gray (PAG), nucleus cuneiformis (NCF), and rostroventromedial medulla (RVM). Under cortical and hypothalamic control (orange traces) these structures contribute to widespread, bi-directional modulation of incoming signal from the dorsal horn (purple traces), and are implicated in sensitization in pain models. Potentiation (+) of RVM ON-cell and suppression (−) of OFF-cell activity has been observed in a migraine model. Hypothalamic descending modulation. There are direct projections from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of hypothalamus to the TNC, which increase TNC activation in a migraine model (green traces). More widespread projections from a small population of oxytocin-expressing (OT) neurons in PVN suppress dorsal horn wide dynamic range neuron firing (blue traces). This population is also responsible for reduction suppression of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) activity, via humoral release of OT (not shown). References in text.

Descending modulation from brainstem structures can have widespread effects on pain processing. Periaqueductal gray (PAG), nucleus cuneiformis (NCF) and rostroventromedial medulla (RVM) exert both excitatory and inhibitory effects on dorsal horn neurons (Ossipov et al., 2010)(Figure 5). In migraineurs, an increased allodynia score during the headache is associated with reduced volume of brainstem structures that include PAG and NCF(Chong et al., 2017), and interictal migraineurs show hypoactivation of NCF in response to noxious stimuli compared to controls(Moulton et al., 2008). Consistent with prior work in pain models(Fields, 2004), PAG stimulation suppresses the TNC neuronal response to noxious trigeminal input (Knight and Goadsby, 2001). It is possible that long-term changes in PAG/NCF output reduce descending pain inhibition in migraine, increasing the response to algesic stimuli.

RVM is the primary output structure mediating descending pain modulation. In RVM, ON and OFF cells fire on nociceptive stimulus onset and offset, and are thought to be associated with pain facilitation and suppression, respectively(Fields, 2004). Increased ON cell and decreased OFF cell activity has been observed in non-migraine pain models(Carlson et al., 2007); similar work has been extended to a migraine model. Rats acutely exposed to inflammatory mediators on the dura showed facial and hindpaw allodynia lasting several hours, associated with increased ON- and decreased OFF cell activity (Edelmayer et al., 2009). Moreover, inactivation of putative ON cells in RVM reduced the allodynia. These results suggest that changes in RVM output may be sufficient for the generation of the widespread allodynia associated with the migraine attack. Whether it is sufficient for other sensory amplifications is not known.

Hypothalamus

Another source of potentially widespread integration and descending modulation is the hypothalamus. Migraine has several characteristics which suggest hypothalamic involvement, including autonomic outflow, circadian phenotypes, and in some patients a premonitory phase prior to the attack that can include hunger and thirst, increased or decreased arousal, and affective changes(Alstadhaug, 2009).

Given the myriad, coordinate roles of hypothalamus in homeostasis, it is unlikely that only one nucleus is involved. However several lines of evidence suggest a role for the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Direct reciprocal connections exist between PVN and TNC, and PVN activity facilitates dura-evoked TNC firing. PVN neurons also send processes to the SSN and LC, potentially mediating headache related autonomic outflow, and to other brainstem structures involved in pain processing, including PAG and PBN) (Robert et al., 2013) (Figure 5). Finally, the PVN integrates sensory, autonomic, and affective information from across the nervous system – this is especially relevant to the integrated stress response(Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). The PVN is thus in a position to sense potential triggers of headache from brainstem and spinal cord, as well as the filtered output of higher sensory (somatosensory cortex, insula) and affective/interoceptive (anterior cingulate, central amygdala, insula) centers. Importantly, its outflow is broad enough, both by anatomy and by modality (sensory, autonomic, affective/stress) to hypothetically generate multiple gain phenotypes of the migraine attack.

On a related note it has been suggested that the hypothalamus, particularly PVN, might potentially serve as an endogenous triggering center for migraine attacks(Burstein et al., 2015; Robert et al., 2013). Potentially consistent with this, hypothalamic signal increases have been observed in the premonitory phase of NTG-triggered attacks with 15O PET, and in response to trigeminal stimulation in the pre-ictal phase of spontaneous attacks with fMRI (Maniyar et al., 2014; Schulte and May, 2016). However, these studies cannot determine whether hypothalamic activity in migraine is causal, or consequence of a preceding trigger. Moreover, in the case of NTG-triggered attacks, one cannot rule out that the observed increase in hypothalamic signals originates from sensitivity of hypothalamic neurons to NTG that is unrelated to migraine.

Recent work underlines the far-reaching, pain-specific effects of hypothalamus: a small set of parvocellular oxytocin neurons in PVN and supraoptic nucleus reduce the firing rate of dorsal horn neurons to inflammatory (but not neuropathic or heat) pain stimuli(Eliava et al., 2016) (Figure 5). The anatomical reach of these projections suggests an ability to broadly modulate nociception. Their specificity (and opposite polarity to the facilitatory effects of PVN in TNC above(Robert et al., 2013)) suggest the existence of multiple modules that could potentially influence migraine sensory gain. Functional circuit mapping and manipulation of PVN inputs and outputs, combined with known migraine triggers (CSD, NTG, CGRP, PACAP) could provide insight into the role of PVN in migraine, and the multisensory gain modulation of migraine attacks.

Other hypothalamic nuclei could also be relevant to migraine - in addition to PVN, lateral hypothalamic, perifornical, retrochiasmatic, and A11 nuclei project to TNC(Abdallah et al., 2013). The dopaminergic A11 nucleus of the posterior hypothalamus has been tested in migraine models. (Charbit et al., 2009), with activation of A11 neurons reducing the dura-evoked firing rate of TNC cells. A11 neurons project broadly, including to Po/LP thalamic neurons that integrate photic and dural nociceptive input – thus they are potentially in a position to alter the gain of multiple sensory modalities (Kagan et al., 2013). Finally, histaminergic cells of the tuberomamillary nucleus project across the nervous system; their activity is associated with arousal, immunity, and the stress response(Alstadhaug, 2009). Antihistamines are used in migraine treatment, and prevent mast cell degranulation, which amplifies dural nociception (Levy et al., 2007). It is unknown whether central histaminergic projections are involved in migraine pain or sensory amplification; however their role in the coordinated stress response suggests this is possible (Panula and Nuutinen, 2013). Moreover, as with the A11 nucleus, the tuberomamillary nucleus projects to Po/LP thalamic neurons that integrate pain and light (Kagan et al., 2013). An overall hypothesis that emerges is that the homeostatic and gain-setting features of the hypothalamus may be altered in migraine, with either greater sensitivity to homeostatic fluctuations like sleep or food intake, amplified response to the fluctuations, or both. Given hypothalamic roles in descending pain modulation, autonomic control, and stress response, altered hypothalamic gain could have far-reaching effects, either favoring or potentially triggering attacks. The fact that many hypothalamic nuclei, including PVN, are under tonic inhibitory control(Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009) brings up the possibility of disinhibitory gating in hypothlalamus as a mechanism of gain (dys)regulation in migraine.

The hypothalamus is a plastic structure – this has been amply demonstrated in PVN. Corticotropin-releasing parvocellular neuroendocrine cells of the PVN, involved in the release of corticosterone in mice (cortisol in humans) undergo both short- and long-term changes in both glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses in response to acute stress(Bains et al., 2015). There is also evidence of stress-induced plasticity in migraine-relevant models - the inhibitory effect of PVN-injected muscimol on TNC firing rate is reduced after acute stress (Robert et al., 2013). Given the profound effect of stress on migraine(Borsook et al., 2012) and the new tools available to study PVN-related circuitry(Bains et al., 2015; Eliava et al., 2016), further work along these lines in chronic migraine models could be very promising.

Thalamus and thalamocortical networks

The thalamus controls the flow of information to the cortex, and the neural networks that interconnect the thalamus and the neocortex are central to sensory information processing. With its broad connectivity, as well as its role in state changes and cortical gain modulation, the thalamus is a potentially key node in migraine network (dys)function. A potentially integrative role of posterolateral thalamus has been demonstrated for photophobia (see above and Figure 2). Posterolateral (Po, LP) thalamus has also been implicated in allodynia in both rat and human models(Burstein et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). Neurons of posterolateral thalamus send particularly broad projections to several cortical areas, including V1, V2, auditory and parietal association cortices; this pattern of direct projection to multiple cortices might be a distinct feature of the trigeminovascular pathway, given the limited cortical projections of nociceptive thalamic neurons that respond to somatic skin stimulation(Noseda et al., 2011). In addition, posterolateral nuclei and other higher order (Figure 6) thalamic nuclei participate in cortico-thalamo-cortical (transthalamic) circuits and are involved cortico-cortical communication(Sherman, 2016). Interestingly, though thalamus does not receive afferents from the olfactory bulb, it is reciprocally connected to piriform (olfactory) cortex via the mediodorsal nucleus(Courtiol and Wilson, 2015) The transthalamic circuits and the specific broad direct projection pattern to multiple cortices of dura-sensitive Po/LP neurons may provide an anatomical substrate for the global dysfunction in multisensory information processing and integration that characterizes migraineurs in the interictal period(Schwedt, 2013). Potentiation of posterolateral thalamic neuron synapses might provide a circuit mechanism for long-lasting photophobia and allodynia during the attack and in chronic migraine; by virtue of the broad cortical projections, other sensory gain phenotypes are possible.

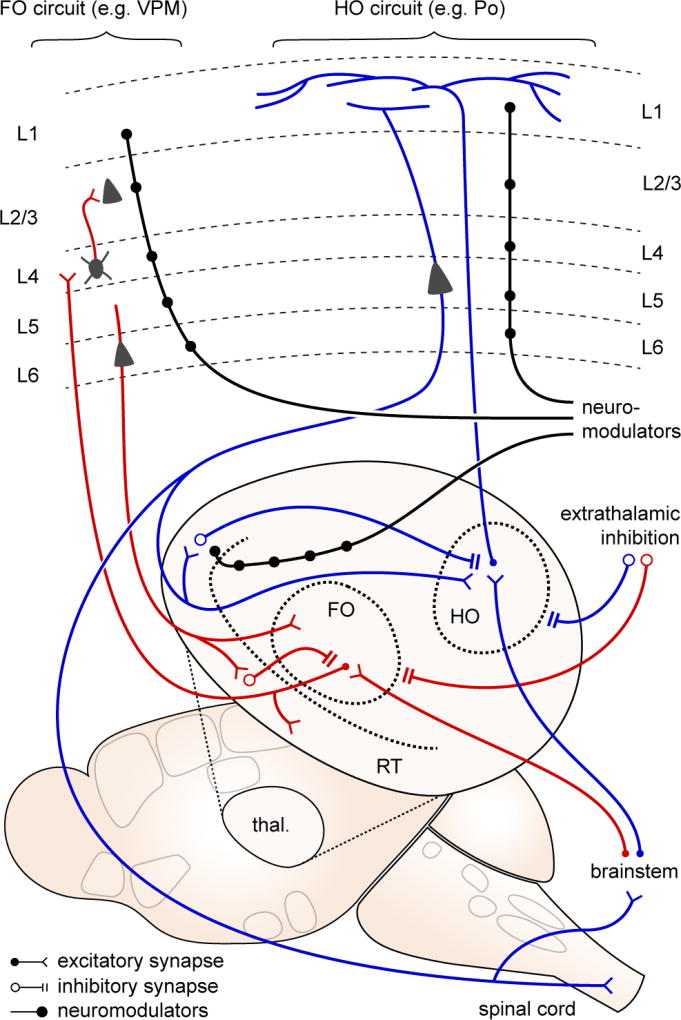

Figure 6. Circuits of potential relevance to migraine: thalamus and thalamocortical.

Thalamic relay nuclei are classified as first order (FO; red traces), where the primary (driver) input is from brainstem and spinal cord afferents; and higher order (HO; blue traces), where a significant proportion of driver input is from layer 5 of cortex. FO nuclei serve as sensory relays from the periphery, projecting primarily to cortical layer 4. HO nuclei may serve a more integrative role, projecting more diffusely thoughout the cortex, especially within layer 1. Thalamic activity is constrained by two sources of inhibition - local inhibition from the reticular nucleus (RT), and extrathalamic inhibition from zona incerta, basal ganglia, pretectal nucleus, and pontine reticular formation. ETI is suppressed in neuropathic pain models, leading to significantly increased activity in posterior (Po) thalamus, a HO relay. Both FO and HO circuits are susceptible to neuromodulation (black traces), at the thalamic and cortical levels.

In addition to their cortical targets, thalamic relay neurons project to inhibitory neurons in the reticular nucleus, which provide feedback inhibition (Figure 6). This inhibition provides a precise temporal ‘window’ for thalamocortical and corticothalamic information flow(Fogerson and Huguenard, 2016), that can be quite selective. For example, a switch in attention from visual to auditory stimuli coincides with with a selective activity increase in a visually-associated sector of reticular nucleus, rapidly decreasing the gain of visual information while attention shifts to auditory stimuli(Wimmer et al., 2015). Pathological amplification of cortico-reticulo-thalamic activity is seen in absence epilepsy(Fogerson and Huguenard, 2016). A more subtle dysrhythmogenesis, termed ‘thalamocortical dysrhythmia,’ has been proposed for pain and tinnitus, on the basis of increased coherence between gamma and theta activity observed in patients with these conditions(Llinás et al., 1999). Similar phenotypes have been observed in migraine (Coppola et al., 2007). A potential underlying hypothesis is that the gating function of reticulothalamic circuits is impaired, perhaps contributing to multimodal sensory amplification.

The gain of thalamic activity can also be dramatically altered by extrathalamic inhibition of higher order nuclei(Halassa and Acsády, 2016). A network of GABAergic nuclei (zona incerta (ZI), basal ganglia, pretectal nucleus, pontine reticular formation) project directly and with high fidelity onto higher order neurons, mediating rapid and profound inhibition. Of potential relevance to migraine is a circuit centered on Po. Po receives excitatory input from both cortical (layer 5 of S1) and subcortical (trigeminal) afferents. Both layer 5 and trigeminal inputs send collaterals to ZI, mediating a fast feedforward inhibition so potent that sensory-induced activity in Po is normally very sparse(Lavallée et al., 2005; Trageser and Keller, 2004). However, this inhibitory circuit is subject to disinhibition – either via convergent L5 and trigeminal inputs, or via cholinergic neuromodulation - resulting in significant increases in gain. Disinhibition of the trigeminal-ZI-Po-S1 circuit has been observed in chronic pain models(Masri et al., 2009), and might also be predicted in migraine models.

Neuromodulatory inputs on thalamus are a major contributor to thalamocortical activity (McCormick, 1992; Varela, 2014). Both cholinergic and noradrenergic stimulation depolarize thalamocortical cells; however they have opposite effects on reticular nucleus neurons: hyperpolarization to cholinergic and depolarization to adrenergic stimuli(Hirata et al., 2006). Thus the net effects are different, with cholinergic stimulation increasing evoked thalamocortical cell activity, and broadening their receptive fields, and noradrenergic stimulation decreasing activity and increasing signal-to-noise. Speculatively, both might be relevant to migraine, with cholinergic outflow mediating broad increases in gain, and noradrenergic activity increasing signal-to-noise ratio, e.g. as seen in sensory map sharpening after CSD(Theriot et al., 2012).

Cortex and corticofugal networks

The cortex is where the migraine attack reaches conscious awareness. Consistent with other pain conditions, functional imaging in migraineurs during the attack shows activity in multiple cortical regions – a so-called ‘pain matrix’ which is now recognized as part of a broader salience network (Legrain et al., 2011; Tracey and Mantyh, 2007). Primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, insula, anterior cingulate, and temporal pole/amygdala are prominent sites of activation, consistent with the somatosensory, interoceptive, and affective nature of the percepts (Schwedt et al., 2015; Sprenger and Borsook, 2012). In interictal migraineurs, increased activation in response to noxious stimulation is seen in these same regions, and is also observed in areas involved in cognitive aspects of pain processing and top-down modulation of pain (e.g. orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex)(Schwedt et al., 2015; Sprenger and Borsook, 2012). There is electrophysiological evidence of increased response to sensory stimulation in interictal migraineurs: evoked potentials show either larger responses or decreased habituation to repetitive stimuli(de Tommaso et al., 2014); and transcranial magnetic stimulation phosphene (evoked visual percept) threshold is lower in most studies(Brigo et al., 2012). A final prominent cortical phenotype in migraine is the passage of CSD through broad regions of cortex, concomitant with the migraine aura (Charles and Brennan, 2009; Pietrobon and Moskowitz, 2014).

Cortical gain mechanisms are of potential relevance to migraine. Gain can be modulated quite rapidly – within 50–100ms in the case of UP- and DOWN-states, quasi-periodic changes in local network activity seen during sleep and also during quiet restfulness(Haider and McCormick, 2009). Cholinergic and noradrenergic neuromodulatory activity can rapidly mediate behaviorally-relevant gain increases in visual cortex; (Fu et al., 2014; Polack et al., 2013). Specialized feedback and feedforward inhibitory microcircuits exist within multiple cortical regions for gain modulation and maintenance of the excitatory-inhibitory balance necessary for the transfer of information while preventing runaway excitation(Tremblay et al., 2016). The coordinated action of layer 6 pyramidal neuron intracortical projections to superficial layers and and deep projections to thalamus is also important in cortical gain modulation(Bortone et al., 2014). Finally, disinhibitory circuits have been identified in visual(Fu et al., 2014), somatosensory(Lee et al., 2013), auditory and medial prefrontal cortex(Pi et al., 2013), and amygdala(Wolff et al., 2014). All of these circuit mechanisms appear to be important for gain control by behavioral states; none have been explicitly tested in migraine models.

Synaptic plasticity mechanisms – both LTP and LTD – have been demonstrated in most excitatory and some inhibitory synapses of primary sensory cortex(Feldman and Brecht, 2005; Hübener and Bonhoeffer, 2014). These are of interest because the synaptic assemblies of primary sensory cortex are thought to underlie discriminative sensation and sensory learning – functions that appear dysfunctionally amplified in migraine. LTP and LTD can also be induced in brain slices from both anterior cingulate cortex and insula, and changes consistent with synaptic plasticity (increased NMDA receptor subunit expression, AMPA subunit phosphorylation) are correlated with the behavioral pain response in both regions(reviewed in Bliss et al., 2016). Insula integrates interoceptive information from the whole body and couples it to autonomic outflow and salience network activation (Uddin, 2015). Anterior cingulate is broadly connected to the salience network, and both anterior cingulate and insula project to PAG, RVM, and dorsal horn(Shackman et al., 2011; Tracey and Mantyh, 2007). Plasticity in either or both of these regions could have broad effects on migraine-relevant perception and its valence.

Fear learning as a migraine-relevant example of valence-mediated sensory tuning

The amygdalar complex (amygdala) is a set of heterogeneous cortically- and striatally-derived nuclei with diverse roles; an important function is the integration of sensory and affective input(Swanson and Petrovich, 1998). It contains populations of CGRP-expressing neurons relevant to viscerosensation (Figure 2d), and is an integral part of descending modulation through PAG and RVM (Figure 5)(Ossipov et al., 2010). Functional imaging evidence suggests increased amygdalar activity in migraineurs vs. controls, with larger stimulus- and headache-evoked responses, and increased functional connectivity to pain and salience network structures(Schwedt et al., 2015). Together with anterior insula, prefrontal cortex and the entorhinal complex, the amygdala is one of the critical regions involved in exacerbation of pain by its anticipation(Tracey and Mantyh, 2007). Though there is little objective characterization of the phenomenon, there is overwhelming anecdotal evidence from clinical practice that negative anticipation of attacks is a major part of the burden of migraine.

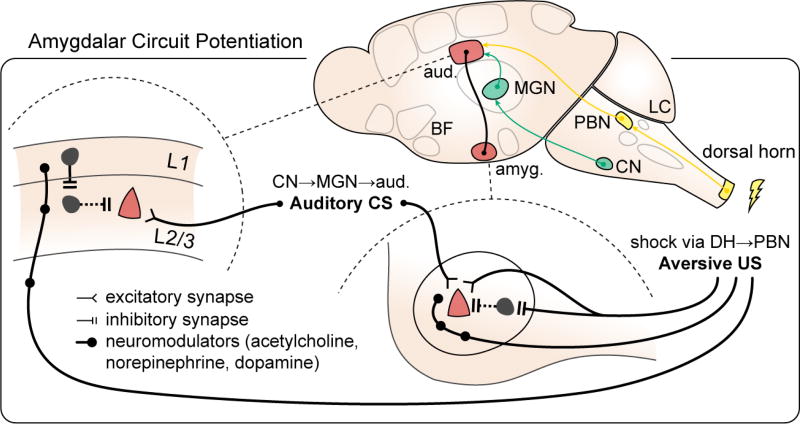

The amygdala is a plastic structure, most clearly demonstrated with fear conditioning(Herry and Johansen, 2014). Fear conditioning is commonly construed as a paradigm for fear memory; however it can just as easily be interpreted as a pain memory, one that can be remarkably quickly established(Neugebauer, 2015). Foot shock (the most commonly used unconditioned stimulus) is a painful event, and presumably the fear/avoidance behavior generated is a response to the pain. Fear learning is also an interesting example of multisensory integration, as an innocuous sensory input (the conditioned stimulus; typically auditory) becomes linked to a nociceptive input. In fear learning paradigms, a combination of conditioned and unconditioned stimulus input, disinhibition, and neuromodulator release result in potentiation of pyramidal neuron synapses in both lateral and central nuclei of the amygdala. Importantly however, layer 2/3 pyramidal cell synapses in primary somatosensory cortex are also potentiated in fear learning paradigms, via nociception-induced, neuromodulator-mediated disinhibition(Herry and Johansen, 2014) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Amygdalar circuit potentiation.

in fear learning paradigms. Fear learning provides a potentially migraine-relevant example of distributed circuit changes during an aversive event. Synaptic potentiation (red) occurs not only on pyramidal cell synapses in amygdala (right; lateral nucleus of amygdala shown) but also in the auditory cortex, the recipient region for the conditioned stimulus (CS, US: conditioned, unconditioned stimulus, pathways delineated in green and yellow, respectively; L1, L2/3: layers 1, 2/3; aud.: auditory cortex; amyg.: amygdala; CN: cochlear nucleus; MGN: medial geniculate nucleus; DH: dorsal horn; PBN: parabrachial nucleus; LC: locus ceruleus; BF: basal forebrain; adapted from Herry and Johansen, 2014).

Specific synaptic changes in both amygdala and sensory cortex thus mediate the transformation of an innocuous sensory stimulus into an aversive one, with amplification of its emotional salience and changes in sensory tuning to better identify it. The integration of multisensory information in lateral nucleus and output control in central nucleus suggest the amygdala as a possible network hub in generating rapid multi-sensory amplifications in acute and chronic migraine.

An integrative view: making sense of multisensory gain from a network perspective

The above section touched on locations that are likely relevant to the migraine attack and chronification. But how are they bound? What are the potential circuit substrates of pan-sensory amplification in migraine?

Both the migraine attack and the chronic migraine state are intrinsically multisensory, involving vision (photophobia), somatosensation (allodynia), audition (phonophobia), olfaction (osmophobia) and interoception (head pain, nausea). Such broad, temporally synchronous sensory amplification, presumably occurring in diverse brain regions, is difficult to explain in the absence of coordinated activity. We hypothesize that migraine must take advantage of pre-existing circuit mechanisms that bind and amplify multiple sensory modalities. These mechanisms must be capable of increasing the gain of the sensory response over potentially all modalities, within tens of minutes.

The migraine attack

It may be useful to 'work backward', considering a hypothetical scenario where a migraine attack with all its sensory ampifications is entrained. In this scenario, we posit that pyramidal neurons in visual, somatosensory, auditory, olfactory, and insular cortex (among others) experience an increase in the slope of their input-output function (or an increase in gain; Figure 1; Haider and McCormick, 2009). How might this occur, within a tens-of-minutes time frame and persist for the duration of the attack? Multiple, potentially summating mechanisms could contribute, including altered intrinsic properties, increases in synaptic efficacy, and/or disinhibition(Letzkus et al., 2015; Malenka and Bear, 2004; McCormick, 1992). Synaptic plasticity and disinhibition could be effected by long-range glutamatergic cortico-cortical or cortico-thalamo-cortical projections. This could be envisioned as a 'daisy-chained' process(Sandkühler and Gruber-Schoffnegger, 2012), whereby one activated region triggers another region, or one that is coordinated by hub regions (e.g. thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate, amygdala, hypothalamus). The process is likely complemented by the activation of neuromodulatory centers, which have the ability to enact intrinsic modulation, favor synaptic plasticity, and effect disinhibition(McCormick, 1992; Zagha and McCormick, 2014). Given their close association with nociceptive network activity and their ability to effect cortical as well as subcortical gain changes, locus ceruleus, basal forebrain, and dorsal raphe are possible candidate nuclei(Aston-Jones et al., 1986; Samuels and Szabadi, 2008).

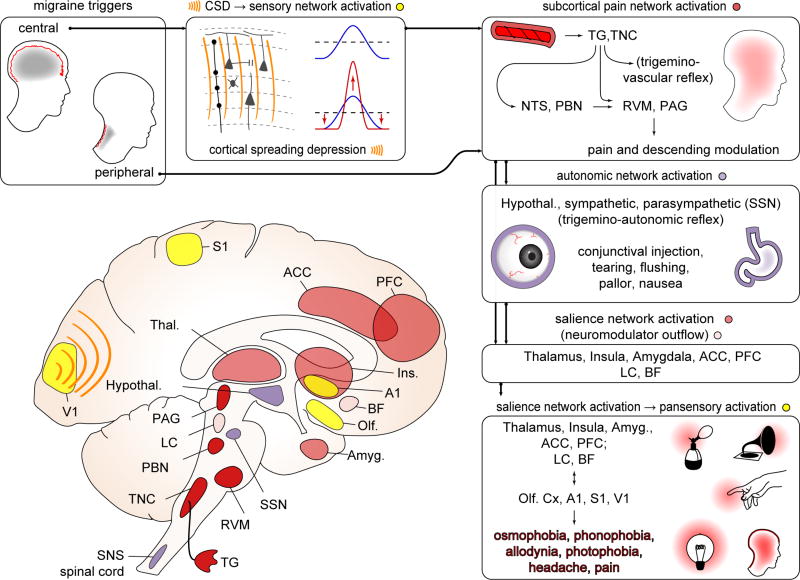

There are thus potential (though undemonstrated) mechanisms to explain a widespread increase in cortical gain in migraine. What might trigger this change in circuit function in many regions simultaneously? We hypothesize that the full sensory phenotype of the migraine attack is generated by the activation of broadly ramified pain/salience networks, whose output in turn modulates the gain of sensory (and other) cortices (Figure 8). The process likely begins with activation of peripheral nociceptors, since central (CSD) and peripheral (nociceptive mediator) models of migraine both act through this common pathway. However nociceptive activity could be pre-conditioned or facilitated via descending projections (e.g. from hypothalamus, PAG, NCF, and RVM; Figure 5) - such activity might also help explain premonitory symptoms that can precede the attack by hours to days. Once a nociceptive signal is entrained, amplifying mechanisms occur both in the periphery and centrally (e.g. CGRP release from nociceptors, autonomic outflow from superior salivatory nucleus; Figure 2), generating a sufficiently large algesic signal to activate brainstem pain/salience network nodes (PBN, NTS), whose output activates both descending (hypothalamus, LC, PAG, NCF, RVM) and ascending (hypothalamus, LC) modulatory activity. Activation of this ensemble of subcortical structures constitutes a major salience signal.

Figure 8. An integrative view: from migraine triggers to pansensory gain.

Boxes clockwise from top left, referring to diagram. Triggers can be central (e.g. CSD) or peripheral (e.g. NTG, CGRP infusion; unknown natural stimuli). Both central and peripheral triggers likely act through the common pathway of the craniofacial pain network (trigeminovascular system; see also Fig 2). CSD can trigger activation of trigeminal afferents. It can also directly modulate cortical network activity - for example through sensory map sharpening. In subcortical pain network activation (dark red structures), whether activated by CSD or peripheral triggers, trigeminal ganglion (TG) and trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC) neurons fire, leading to activation of higher pain/visceral network relays (nucleus tractus solitarius: NTS; parabrachial nucleus: PBN) and regions mediating descending modulation (periaqueductal gray: PAG; rostroventromedial medulla: RVM; locus ceruleus: LC). Depolarization of cranial nociceptive afferents can generate a pain percept, but the sustained pain of a migraine attack may require more extensive circuit activation (e.g. NTS, PBN and their multiple downstream structures), amplification (e.g. feed-forward effects of trigeminovascular reflex) and/or descending modulation (e.g. from PAG, RVM). Subcortical pain network activates autonomic centers: (purple structures) hypothalamus (Hypothal.), superior salivatory nucleus (SSN), LC, and brainstem and spinal cord sympathetic nuclei (SNS). SSN activation is likely responsible for conjunctival injection and tearing that can accompany migraine; broader autonomic network activation likely mediates nausea. Salience network activation (light red structures): Exteroceptive and interoceptive, first order and higher order nuclei in thalamus (Thal.) are activated, and relay to primary (S1) and secondary sensory cortices, insula (Ins.), and regions that encode the negative valence of pain: anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala (Amyg.). Conscious awareness of headache likely requires activation of this distributed salience network. We hypothesize that this pain/salience network activation, likely in concert with neuromodulatory activity (pink structures; locus ceruleus (LC) and basal forebrain (BF) shown) is required for gain alteration in multiple sensory cortices (yellow structures) - primary visual cortex (V1) primary auditory cortex (A1), S1, olfactory cortex (Olf) - generating the sensory amplifications (photophobia, phonophobia, allodynia, osmophobia) that accompany the migraine attack. These amplifications, representing widely distributed cortical regions, are difficult to explain without network coordination.

Proceeding rostrally, the activation of peripheral and brainstem nociceptive networks also results in activation of thalamus, somato- and viscerosensory cortices (S1, S2, insula) and cortical regions involved in the affective/valence response to pain (insula, anterior cingulate, amygdgala). The direct projections of higher order thalamic nuclei involved in the processing of noxious stimuli from the meninges to multiple (sensory and associative) cortices and their involvement in transthalamic circuits mediating cortico-cortical communication make the thalamus a likely candidate node for alteration of multisensory gain. Meanwhile, amygdala likewise has access to all primary sensory cortices(Herry and Johansen, 2014; Price, 2003). The 'nodal' function of thalamus and amygdala likely relies on coordination with neuromodolatory activity for gating of sensory information (Fast and McGann, 2017; Hirata et al., 2006), just as co-ordinate neuromodulatory, glutamatergic, and disinhibitory input are required for plasticity associated with fear learning(Herry and Johansen, 2014) (Figure 7). Similar co-ordinate function could be involved in each cortical region where mechanisms of gain and plasticity are activated.

To a first approximation, this scenario is compatible with human imaging data (with the caveat that imaging does not have the resolution to distinguish certain brainstem structures): the earliest changes associated with the migraine attack occur in TNC, rostral dorsal pons (an area which contains locus ceruleus, nucleus cuneiformis, and parabrachial nucleus) and hypothalamus. During the attack proper, when sensory amplifications are present, activation is consistently seen in the rostral dorsal pons, thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate, sensory cortex, and temporal pole/amygdala. Importantly, the response to diverse sensory stimuli (brush, painful heat, visual checkerboard, ammonia inhalation) is increased in multiple sensory cortices (somatosensory, insula, visual, auditory, secondary sensory and visual) during the attack(Maniyar et al., 2014; Schulte and May, 2016; Schwedt et al., 2015; Sprenger and Borsook, 2012).

Nociceptive and pan-sensory circuit activation is almost surely not linear or one-way. Feed-forward and feed-back gain modulation through corticocortical and corticofugal output could perpetuate and amplify salience network activation and thus pansensory gain. It is also important to emphasize that the full nociceptive, sensory, and affective spectrum of the migraine attack cannot be explained without recourse to widespread cortical as well as subcortical network activation. The migraine attack appears necessarily to be a coordinate, whole-nervous-system event.

Transition to chronic migraine

Long lasting and/or repetitive pain over years leads to profound functional as well as structural changes in the brain networks, reflecting maladaptive plasticity at several levels of the neuraxis and especially the cortex(Tracey and Mantyh, 2007). Reorganization of brain circuitry as a consequence of repeated migraine attacks is suggested by correlations between functional imaging abnormalities in chronic pain-relevant regions and either number of migraine attacks, or number of years with migraine(Schwedt et al., 2015; Sprenger and Borsook, 2012). Interestingly, in chronic migraineurs the electrophysiological changes in sensory cortices are similar to those in episodic migraineurs during migraine attacks; thus, from the electrophysiological point of view chronic migraine indeed resembles a never-ending migraine attack(Coppola and Schoenen, 2012). This may be consistent with the idea that the transition from episodic to chronic migraine may involve a shift from the transient sensory amplifications of the migraine attack to a persistent state of sensitization and sensory amplification.

Gain modulation and plasticity go hand in hand; if we can understand the mechanisms that underlie the sensory changes of the migraine attack, an understanding of chronification may follow straightforwardly from plasticity-based consolidation of the network phenotypes. Different forms of plasticity are well established in chronic pain models, from spinal cord to the primary sensory cortices whose function is presumably affected during sensory amplification(Kuner and Flor, 2016; Sandkühler and Gruber-Schoffnegger, 2012). Comparatively less work has been done on potential hypothalamic and thalamic plasticity as regards either pain or migraine, though work from the stress field demonstrates that plasticity occurs in potnentially migraine-relevant hypothalamic nuclei(Bains et al., 2015), and work in non-migraine pain models suggests long-term changes in extrathalamic inhibition(Masri et al., 2009). Demonstrated plasticity in anterior cingulate in chronic peripheral pain models might be relevant to the affective/motivational pain phenotypes seen in chronic migraine(Bliss et al., 2016). Finally, the robust literature on amygalar plasticity in fear conditioning models(Herry and Johansen, 2014) could inform the significant aversion that accompanies chronic migraine.

While it is easy to propose plasticity in distributed migraine-relevant circuits as a mechanism of chronification, almost no work has been done in this regard, and the field would benefit from the further development of chronic migraine models with both face and construct validity. The most developed so far are models of chronic inflammatory mediator and NTG exposure(Oshinsky and Gomonchareonsiri, 2007; Pradhan et al., 2014), which typically measure trigeminovascular nociceptive outcomes. The long-term circuit effects of CSD (to model migraine with aura), and analgesic exposure(De Felice et al., 2010) (to model medication overuse) are also of interest.

Modulating gain, co-opting plasticity: circuit modulation in migraine

The widely distributed network activation we propose in migraine has implications for treatment. Its diffuse nature means that it may be resistant to single-point perturbation; on the other hand it offers multiple points of entry.

Intercepting the migraine process before it fully entrains itself is appealing, but is likely not necessary. Triptans (5HT1b/d serotonin receptor agonists used in acute treatment) are more effective early in the attack, potentially because these peripherally-active agents have less effect once central sensitization has occurred(Burstein and Jakubowski, 2004; Burstein et al., 2004). However they are not ineffective when given later in the attack. In general, techniques that are presumed peripherally active - e.g. botulinum toxin (Ramachandran and Yaksh, 2014) and CGRP antagonists (Russo, 2015) - are quite effective even in chronic migraine, arguing that addressing migraine triggers at the peripheral nociceptor level is a viable approach at all stages of migraine.

However, the coordinate network activity of the migraine attack can be difficult to disrupt once entrained. Thought it is certainly not a universal phenomenon, for some patients one of the most effective treatments for acute migraine is sleep(Brennan and Charles, 2009) - it is possible that the transient but profound change in network activity during sleep is sufficient to disrupt gain and plasticity mechanisms induced during the attack. 'Induced state change' via infusion of ketamine (an NMDA antagonist) has been used in chronic pain (Niesters et al., 2014), and propofol (a short-acting GABAergic anesthetic) is occasionally used in severe chronic migraine(Dhir, 2016). Perhaps similarly, electroconvulsive therapy is used for refractory depression(UK ECT Review Group, 2003). These treatments are meant for the sickest patients, and they carry nontrivial risks. But from a conceptual point of view the forced disruption of a 'dysfunctional' network could make sense. Less extreme and more focal network disruption may be occuring with techniques such as peripheral nerve stimulation and blockade, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation(Ambrosini et al., 2015).

The 'resetting' of network function assumes there is a 'normal' network to return to. In chronic migraine, this may not be the case - through plastic changes, the network may be biased toward increased gain. In this scenario the idea of co-opting plasticity mechanisms becomes appealing. For the sickest migraine patients, while medications and procedures are helpful, the most long-lasting effects are seen when these are combined with with multimodal management including exercise, behavioral retraining, and attention to affective symptoms(May and Schulte, 2016). The emphasis is slow, progressive change in behavioral patterns; potentially consistent with learning or plasticity processes. Whether this kind of therapy can be 'reverse engineered' without more precise knowledge of the circuit is not known.

Techniques like deep brain stimulation are commonly used in neurologic disease, and the advent of closed loop modulation in brain-machine interfaces in epilepsy and central nervous system injury (Moxon and Foffani, 2015) allows the contemplation of such interventions in migraine. A critical difference in disorders where these techniques are in place is that loci of circuit dysfunction (e.g. seizure or injury focus) are known to at least some precision. This is usually not the case with migraine - though the closed-circuit interruption of a consistent aura focus(Hansen et al., 2013) could be contemplated. It is also argued that migraine is not severe enough to justify such interventions. Clearly a balance of risk and reward is necessary, but often the public is naive to how severely migraine affects the lives of sufferers and their families.

Looking forward, it is appealing to contemplate the use of less-invasive techniques such as functional ultrasound(Legon et al., 2014) to access network locations that are not immediately under the skull. In the longer term, closed loop opto- or chemogenetic techniques(Grosenick et al., 2015) could offer immense precision in circuit modulation. However here again precise circuit delineation is imperative.

Questions for further research

The central argument of this manuscript is that the migraine attack and chronic migraine can be usefully understood as disruptions in sensory gain and plasticity.. Though likely oversimplified, it is an overall hypothesis that we believe is accessible to the tools of current systems neuroscience. However it is almost completely untested.

An important priority is to refine our conception of the 'migraine circuit.' To what extent do migraine-relevant pathways converge with circuits from other pain disorders, and how are they different? On a related note, if nociceptive network activation is common to migraine and other pain disorders, why are sensory amplifications more prominent in migraine? Modern tracing techniques, including combinatorial genetics, activity-based and transsynaptic tracing(Beier et al., 2015), and tissue clearing(Richardson and Lichtman, 2015), can help delineate what are likely complex, parallel networks.

It is also critical to reliably model sensory amplifications in animal models, at the circuit level. There are robust models for CSD and trigeminovascular sensitization including allodynia, and models of photophobia and chronic migraine are developing; however there are no migraine-centered models of phonophobia or osmophobia, or the combined multisensory changes that occur in migraine. Here current techniques for functional circuit mapping and interrogation (Sakurai et al., 2016; Tonegawa et al., 2015), coupled with migraine-relevant stimuli, could again be useful.

It is a near-complete mystery how a migraine attack starts. For attacks that begin with migraine aura, how can such a massive depolarization arise from apparently normal brain? For migraine without aura, what changes in network function allow the initiation of a perpetuated pain process? How does a migraine attack stop? On longer time scales, how does episodic migraine become chronic?

For even the 'established' phenomena in migraine research (e.g. CSD, trigeminovascular sensitization) there is an almost complete lack of synaptic, let alone cellular/molecular understanding (a rare exception is the monogenic migraine syndromes(Brennan et al., 2013; Capuani et al., 2016; Leo et al., 2011; van den Maagdenberg et al., 2004, 2004). Do CSD or trigeminovascular stimulation induce (or occlude subsequent induction of) LTP? By what membrane and cellular mechanisms?

Migraine research was once described by an NIH leader as 'primitive.' This is not inaccurate, though it is also fair to characterize migraine neuroscience as a field in its infancy, with tremendous opportunity. It is a disease that is being increasingly recognized by society as significant and worthy of investigation. And it could benefit immensely from the skills of trained neuroscientists.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Luis Villanueva, Matt Wachowiak, Jason Shepherd, Maggie Waung, and the members of the Headache Physiology lab for helpful comments, and Jeremy Theriot for assistance with figures. Funding: NIH/NINDS NS085413, NS102978 (KCB); Telethon GGP14234 (DP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: KCB, DP; Investigation, KCB, DP; Writing - Original Draft: KCB; Writing: Review & Editing: KCB, DP; Funding Acquisition: KCB, DP.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abdallah K, Artola A, Monconduit L, Dallel R, Luccarini P. Bilateral descending hypothalamic projections to the spinal trigeminal nucleus caudalis in rats. PloS One. 2013;8:e73022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstadhaug KB. Migraine and the hypothalamus. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:809–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini A, D’Alessio C, Magis D, Schoenen J. Targeting pericranial nerve branches to treat migraine: Current approaches and perspectives. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:1308–1322. doi: 10.1177/0333102415573511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Gi-protein-coupled 5-HT1B/D receptor agonist sumatriptan induces type I hyperalgesic priming. Pain. 2016;157:1773–1782. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashina M, Hansen JM, À Dunga BO, Olesen J. Human models of migraine - short-term pain for long-term gain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017;13:713–724. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]