Abstract

Objective

To assess the effects of marital conflict on parenting practices for mothers and fathers and to examine whether these effects differ for within-person and cross-person links in parental dyads.

Background

Existing findings are mixed regarding the nature and magnitude of the association between marital conflict and childrearing behaviors. Little is known about parental role differences in this regard between fathers and mothers and the mutual influence on the other’s responding.

Method

A sample of 235 families (fathers, mothers, and their kindergarten children) participated in the study over a 2-year period. Fathers and mothers independently reported on constructive and destructive marital conflict tactics, as well as on their parenting behaviors in scenarios of children experiencing negative emotions.

Results

Results indicated cross-person and within-person relations. For example, fathers’ destructive conflict predicted mothers’ distress reactions to children’s negative emotions, supporting a spillover hypothesis. Mothers’ destructive conflict behaviors predicted less unsupportive maternal parenting, supporting a compensatory hypothesis.

Conclusion

Fathers’ and mothers’ marital conflict behaviors may have different implications for their own and their spouse’ parenting.

Implications

Intervention and prevention programs that target improving marital conflict interactions may also help promote positive parenting. The findings also support that both fathers and mothers should be included in these programs to increase the beneficial effects on parenting practices.

Keywords: marital conflict, parenting, spillover, parent gender, family systems theory

Marital quality is widely recognized as a cornerstone of adaptive family functioning; disturbances in the marital relationship may negatively influence parents’ behaviors in parent–child relationships (Cox, Paley, & Harter, 2001; Erel & Burman, 1995) and affect children’s socioemotional outcomes. Marital conflict, as an index of aversive marital relationship behaviors, is consistently related to negative parenting and children’s adjustment problems (e.g., Benson, Buehler, & Gerard, 2008; Klausli & Owen, 2011). However, studies testing the marriage–parenting link have often been focused on destructive marital conflict (e.g., hostility and aggression) and have neglected constructive conflict in which the married dyads work cooperatively to solve problems or disagreements. In addition, despite the interdependent nature of family relationships, a dynamic, interpersonal perspective on testing the association between marital conflict and parenting, such as the mutual influence between fathers and mothers, has been rarely employed. In this study, we investigated the influence of constructive and destructive marital tactics on parenting behaviors, with a particular interest in the dyadic cross-person influences.

Family systems theory conceptualizes the family unit as an organized collection of relationships and behaviors, with interactions in one family subsystem influencing other family subsystems (Cox & Paley, 1997). The marital subsystem, in particular, is considered to be a driving force of other family subsystems, such as the parent–child subsystem. Negative qualities of marital relationships may be mirrored in aspects of parent–child relationships (Engfer, 1988; Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000): Parents’ repeated experience of marital discord and the negative affect associated with it in the marital subsystem may undermine their caregiving abilities in the parent–child subsystem. Referred to as the spillover effect, the interrelatedness of poor marital functioning and parenting difficulties has received substantial supporting evidence via different research designs. For example, Davies and colleagues (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Woitach, & Cummings, 2009; Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2006) found that interparental conflict, indicated by high levels of hostility or withdrawal, was related to parents’ emotional unavailability, parental insensitivity, and psychological control for children in kindergarten or middle-childhood over a 2-year time span. Deleterious effects of marital hostility are evidenced by reduced warmth in family-wide interactions (father, mother, and child) and decreased responsiveness (especially fathers’ responsiveness) in parent–child interactions (Stroud, Durbin, Wilson, & Mendelsohn, 2011). In a meta-analytic review of the association between overt interparental conflict and parenting, Krishnakumar and Buehler (2000) found the association to be moderately strong, supporting the spillover effect. It could be that marital problems may in some cases lead to parental irritability, which may drain parents’ emotional resources necessary to patiently interact with the child (Grych, 2002). It could also be that parents with distressed marital relationships may model dysfunctional relationship behaviors, thus producing problems in parent–child interactions (Emde & Easterbrooks, 1985).

In contrast to the notion of spillover, several studies suggest a negative association, or compensatory relation, between marital distress and parenting difficulties (e.g., Belsky, Youngblad, Rovine, & Volling, 1991; Engfer, 1988; Mahoney, Boggio, & Jouriles, 1986). That is, parents may be less harsh and more involved in parenting to compensate for marital distress and conflict. For example, Brody, Pillegrini, and Sigel (1986) found that mothers in disharmonious relationships with their spouse were more involved with their young children, compared with mothers in harmonious relationships. Consistent with the compensatory hypothesis, parents may attempt to gain a supportive and affectionate connection with their children by engaging in positive parenting behaviors toward their child in the face of marital discord. This compensatory link between marital and parent–child subsystems, however, has received limited empirical support (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000).

Questions remain about why parenting practices in some families are more resistant and others are more vulnerable to the spillover of marital quality (Grych, 2002). The present study was designed to better understand the interrelatedness between marital and parent–child subsystems in two respects: (a) clarification of marital quality and parent–child relationship as multidimensional constructs and (b) differentiation of the links between marital and parent–child subsystems for mothers and fathers. A common approach in studies of marital quality is to form a composite variable based on multiple aspects of the marital relationship, including marital satisfaction, interparental hostility, and interaction negativity (Davies, Sturge-Apple, & Cummings, 2004; Davies et al., 2009; Pedro, Ribeiro, & Shelton, 2012). Although composite measures of the marital relationship may be informative, this approach may obscure variabilities in different aspects of the marital subsystem and their implications for parenting. For example, those who have the same level of marital satisfaction can exhibit either high or low frequency or severity of marital conflict. In the present study, we focused on examining the influence of marital conflict, which is a well-defined dimension of marital quality that is strongly associated with child adjustment (e.g., Barletta & O’Mara, 2006; Buehler et al., 1997; Cummings & Davies, 2002; Emery, 1982; Fincham, 1994; Harold, Fincham, Osborne, & Conger, 1997; Kaczynski, Lindahl, Malik, & Laurenceau, 2006).

In an effort to offer greater clarity to the operational definition of marital conflict, we differentiated constructive and destructive conflict. Because disagreements often bring quarrels and hostility, marital conflict has typically been considered a negative construct that involves behaviors such as physical aggression, verbal aggression, and withdrawal (Buehler et al., 1997; Burman, Margolin, & John, 1993). Meta-analytical studies examining associations between marital conflict and parenting behaviors have typically defined marital conflict as overt negative conflict styles, including the frequency or intensity of aggressive behaviors in the marital dyad (Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Conversely, constructive marital conflict has received less research attention, despite its common existence in daily life (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2003). In fact, many couples may handle their disagreement by employing constructive strategies, such as validation and reasoning with one another (Kerig, 1996). Whereas destructive marital conflict can lead to disruptive parenting, use of constructive conflict strategies may promote positive parenting practices, leading to greater availability and warmth in parent–child relationships (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006). Therefore, another goal of the present study is to disentangle the effects of constructive and destructive conflict tactics on parenting, by examining constructive and destructive marital conflict behaviors separately.

In terms of parenting behaviors, in the present study we focused on parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions. Multiple dimensions of parenting are theorized to be affected by marital conflict, including parental involvement in parent–child activities (Brody et al., 1986), parental responsiveness, and demandingness (Ponnet et al., 2013). Some dimensions of parenting may be more likely than others to be affected by the spillover processes from marital conflict. For example, emotional vulnerabilities stemming from parents’ repeated experience of destructive marital conflict may manifest particularly in parenting difficulties under emotionally challenging contexts posed by their children. As a result, individual differences in parenting that occur in the wake of marital conflicts may be particularly likely to emerge in situations where children are displaying high levels of negative affect. Therefore, in the present study we targeted parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions as indicators of parenting practices. In general, parents react to children’s display of emotions in two ways. Supportive responses by parents help invite children to explore their feelings by encouraging them to express emotions (i.e., expressive encouragement reactions) or by helping the child understand (i.e., emotion-focused reactions) and cope with (i.e., problem-focused reactions) an emotion-eliciting situation. These responses positively influence children’s emotional and social competence (Eisenberg et al., 2001). By contrast, unsupportive responses, including minimizing the child’s emotional experience, punishing the child, or becoming distressed by the child’s emotional displays, are theorized to undermine children’s ability to regulate their emotions and behaviors (Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, & Martin, 2001).

The second direction to enlighten understanding of the link between marital and parent–child subsystems involves differentiating maternal and paternal behaviors. Fathers and mothers may experience marital and parent–child relationships differently and vary in their ways of dealing with marital conflict and parenting their child. When faced with marital conflict, men tend to be less emotionally expressive, more defensive, and use more withdraw and stonewalling behaviors than women (Gottman & Levenson, 1988). Meanwhile, fathers are more likely to exhibit punitive responses, rather than problem-solving strategies, compared with mothers under contexts in which children display sadness (Cassano, Perry, Parrish, & Zeman, 2007). In light of these differences between fathers’ and mothers’ behavior in family subsystems, it is necessary to include fathers and differentiate their roles from that of mothers to empirically examine the effect of marital conflict on parenting practices (Cummings, Merrilees, & George, 2010). Few empirical studies have simultaneously investigated fathers’ and mothers’ marriage–parenting links, and available findings have indicated inconsistent conclusions. On the one hand, some studies have reported that father–child relationships are more vulnerable to marital conflict than mother–child relationships (e.g., Cummings et al., 2010; Davies & Lindsay, 2001; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). For example, Stroud et al. (2011) observed parent–child dyadic interactions in laboratory tasks and found that marital functioning was related to fathers’, but not mothers’, responsiveness to children’s signals for attention. Longitudinal studies corroborated cross-sectional results, in that pathways between interparental conflict and parenting difficulties were only evident for fathers but not mothers (Davies et al., 2009). On the other hand, other studies did not find such gender differences. For example, Erel and Burman’s (1995) meta-analysis of the literature reported no difference between fathers’ and mothers’ link between marital relationship and parent–child relationship. Similarly, Ponnet et al. (2013) reported that the strength of the association between family subsystems was similar for both fathers and mothers.

Previous studies on the influence of the marital subsystem on the parent–child subsystem have rarely considered the cross-person transfer from one parent to the other (Cox & Paley, 1997; White, 1999). Fathers’ and mothers’ parenting is likely to be affected by each other’s level of stress (e.g., marital disharmony) in addition to their own. Only a handful of studies, to our knowledge, have addressed reciprocal influence within the married dyad or investigated the buffering effect of one dyad member on the other member across subsystems. For example, Katz and Gottman (1996) found that father’s withdrawal from the marriage was associated with mother’s rejection of the preschool-age child. Margolin, Gordis, and Oliver (2004) reported in their observational study that wife’s marital hostility was linked to the husband’s negative affect toward the child, for families with husband-to-wife aggression history. Despite the inclusion of fathers in the sample, the preceding studies have simply correlated one parent’s behaviors/emotions in the marital subsystem with the other parent’s behaviors/emotions in the parent–child subsystem, without acknowledging the influence of the other parent’s own behaviors/emotions in marriage. Therefore, results obtained from these studies may not be a precise reflection of important family dynamics; understanding of both the within-person and cross-person associations simultaneously is an important gap in the literature.

In summary, focusing on the interdependent nature of family relations, the main aim of this study was to assess the effect of marital conflict on parenting practices for both fathers and mothers over a 2-year period. Both constructive and destructive aspects of marital conflict were examined to investigate how one parent’s marital conflict behaviors influenced his or her own, as well the spouse’s, reactions in response to children’s negative emotions. More specifically, we addressed the following research questions and hypotheses. First, we examined within-person effect of constructive and destructive marital conflict on each parent’s parenting practices. On the basis of previous findings in two meta-analyses (i.e., Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000), we expected associations between frequent engagement in destructive marital conflict behaviors and high levels of specific dimensions of unsupportive parenting, as well as between greater use of constructive marital behaviors and specific dimensions of supportive parenting, for both fathers and mothers across a 2-year time span. Second, we examined the cross-person effect in which one parent’s engagement in marital conflict behaviors were associated with the other parent’s parenting practices, above and beyond the effects of the other parent’s own marital conflict behaviors. However, no cross-person hypothesis was specified because of the general lack of empirical work to inform any plausible hypothesis. Third, we tested whether within-person and cross-person associations were different for fathers and mothers. Consistent with existing empirical findings, we expected stronger effects of marital conflict on parents’ responses to child negative emotions for fathers than for mothers. With regard to the gender differences in cross-person associations, no specific hypothesis was made.

Method

Participants

The data for this study were drawn from a larger project focusing on linkages between family processes and child coping and adjustment. The original sample consisted of 235 kindergarten children and their parents from the Midwest and Northeast areas of the United States. Families were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (a) The participating child was in kindergarten, (b) the two primary caregivers participating in the study had lived with the kindergarten child for at least 3 years, and (c) all family members were fluent in English. Twenty families (8.5%) dropped out of the study over the 2-year period, resulting in a final sample of 215 kindergarten children (106 girls and 99 boys; mean age at Time 1 = 6.0 years, SD = 0.5; range 5–8) and their parents (mothers’ mean age = 34.9 years, SD = 5.5; fathers’ mean age = 36.9 years, SD = 6.1). The majority of the couples and families (95%) participating at Time 2 were still living together, with the two participating caregivers co-parenting. Analyses revealed no meaningful differences between the families in the present sample (n = 215) and the remaining families (n = 20) on variables examined at Time 1.

Families were recruited via letters sent to local schools, sign-ups at community events, postcard mailings, and referrals of other families. Families were told that participation in the study would require two visits to the research laboratory where they would watch videos, fill out questionnaires, and play together as a family; they were also informed that they would earn $130 for their participation. We made targeted efforts to recruit families of low socioeconomic status and of racial and ethnical diversity to obtain a sociodemographically diverse sample representative of the households in the counties from which our sample was drawn (i.e., one county from the Midwest and one county from the Northeast). A large proportion of the sample was White (77.3%), and smaller percentages were Black (15.9%), Hispanic (4.0%), Asian American (1.1%), Native American (0.2%), and other races (1.5%). The median annual family income of participants fell between $40,000 and $54,999, and 13.4% of the sample reported annual household income below $23,000. These sample characteristics indicated good demographic representativeness of the two local areas. The U.S. Census Bureau (2000) data for the time the sample was recruited indicated that the Midwest county was made up of 82.4% European American, 11.5% African American, and 4.7% Hispanic (numbers for the county from the Northeast were 79.1%, 13.7%, and 5.3%, respectively); median household incomes were $49,653 and $55,900 for two counties, respectively.

Procedure

The study procedure was approved by the university’s institutional review board, and parent consent and assent from children were obtained. Data for this study were collected from two measurement occasions spaced 2 years apart. At each measurement occasion, multiple members of the family (i.e., both parents and the child in first visit and the mother and the child in the second visit) visited the laboratory at one of the research sites and independently completed questionnaires about family relationships and child functioning in individual interview rooms. The present study only used self-reported responses from both parents about their marital conflict tactics and emotion socialization practices.

Measures

Constructive conflict

The Managing Affect and Differences Scale (Arellano & Markman, 1995) was used to assess constructive communication tactics (i.e., editing, love and affection) employed by couples during conflict discussions. For the Love and Affection subscale, participants rated on a 5-point Likert scale about how much they agreed or disagreed with the six items that involved the love and affection expressed toward their partner (e.g., “I’m affectionate toward my partner”). Similarly, both fathers and mothers completed the 12-item Editing subscale, where participants reported the extent to which they controlled their reactions to the partner’s message (e.g., “I try to phrase things positively,” “I express appreciation for partner’s help despite his/her unsuccess”). Adequate internal consistencies of both the Editing and the Love and Affection subscale were obtained for mothers (αs = .82 and .81, respectively) and fathers (αs = .81 and .86, respectively).

Destructive conflict

The Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales (CPS; Kerig, 1996) were used to assess couples’ destructive tactics in handling conflict. Mothers and fathers each completed the six-item Stonewalling scale (e.g., “sulk, refuse to talk, give the ‘silent treatment’”), eight-item Verbal Aggression scale (e.g., “name-calling, cursing, insulting”), and seven-item Physical Aggression scale (e.g., “push, pull, shove, grab partner”). For each item, parents rated on a 4-point scale ranging from never (scored as 0) to often (3) about the frequency they used each behavior in the past year. Internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and various forms of validity for the CPS are well established (Kerig, 1996). Internal consistencies for the subscales in the sample were satisfactory for mothers (.72 ≤ α ≤ .84) and fathers (.69 ≤ α ≤ .87).

Emotion socialization behaviors

The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes, Eisenberg, & Bernzweig, 1990) was used to measure parents’ emotion socialization behaviors. The CCNES questionnaire presents parents with 12 typical scenarios in which children are experiencing negative emotions (e.g., a child loses a prized possession and reacts with tears; a child becomes nervous about people watching him or her when he or she appears in a recital or other public activity). For each scenario, parents were asked to rate on a 7-point Likert scale how likely they would be to react in each of six ways, including minimizing reactions, punitive reactions, distress reactions, expressive encouragement, problem-focused responses, and emotion-focused reactions. The original CCNES scale showed satisfactory alpha reliabilities and test–retest reliabilities (Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002). The internal reliabilities for the six subscales were acceptable for mothers (.62 ≤ α ≤ .88 at Time 1, and .72 ≤ α ≤ .89 at Time 2) and fathers (.68 ≤ α ≤ .89 at Time 1, and .68 ≤ α ≤ .90 at Time 2) in the present study.

Analytical Plan

To explicate the links between marital and parent–child subsystem, we adopted the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), which is capable of assessing mutual influence in relationships. The APIM allows researchers to estimate the extent to which a parent’s independent variable (i.e., each parent’s frequency of using one marital conflict tactic) affects his or her own dependent variable (i.e., that parent’s parenting practice) as well as his or her partner’s dependent variable (i.e., the partner’s parenting practice). In the present report, the parent dyad was the unit of analysis, and cross-person as well as within-person influences in the dyadic processes involving mothers and fathers were examined. Many recent studies have adopted the APIM approach to assess the interdependent nature of different types of family relationships (e.g., Lee, Zarit, Rovine, Birditt, & Fingerman, 2016; Ponnet et al., 2013). For example, Nelson, O’Brien, Blankson, Calkins, and Keane (2009) examined the spillover, crossover, and compensatory effects of parents’ stress on their own, as well as their spouse’s, parenting behaviors. Moreover, in the present study where parenting practices were examined twice over a course of 2 years, the APIM framework enabled specification of the ways in which the relational dynamics of marital conflict and parenting practices unfolded over time.

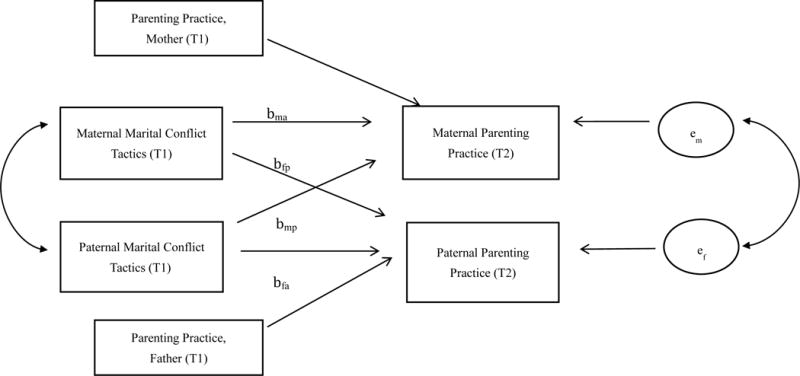

To address the research questions outlined earlier, we estimated two sets of APIM models: the two-intercept models of APIM were applied to examine the within-person effects (actor effects) and cross-person effects (partner effects) of marital conflict tactics on parenting practices for both fathers and mothers, whereas the dyadic interaction models were applied to test whether parent gender differences existed in actor and partner effects of marital conflict on parenting. The two models are statistically equivalent but provide different, yet complementary information for depicting dyadic relationships. Specifically, the two-intercept model provides estimations of actor and partner effects for both dyad members, whereas the dyadic interaction model estimates only one member’s effects (both actor and partner) but is capable of statistically assessing the difference between two members’ effects (Kenny et al., 2006). Therefore, related to our first two research questions, the two-intercept model was applied first to obtain the within-person (actor) and cross-person (partner) effects for both fathers and mothers (see Figure 1 for a visual presentation of the two-intercept APIM model). Two sets of models were estimated (one for destructive marital conflict and one for constructive marital conflict), providing parameter estimates for each of the specific links. The dyadic interaction model was then applied to examine our third research question regarding parent gender differences in the marriage–parenting transmission. Similarly, two sets of models were estimated (one for destructive marital conflict and one for constructive marital conflict), with the results indicating whether actor or partner effects were different between fathers and mothers. In each model, we controlled for parenting practices (outcome variable) at Time 1, family’s social economic status, and child gender. SPSS 17.0 was used to estimate the APIM effects.

Figure 1.

Theoretical two-intercept actor–partner interdependence model. Mother’s and father’s marital tactic and maternal and paternal parenting practice at Time 1 (T1) predict maternal and paternal parenting practice at Time (T2). Single-headed arrows indicate causal or predictive paths. Double-headed arrows indicate correlated variables.

Note. em and ef represent the error terms of parental responses. bma: the coefficient of mother’s actor effect; bmp: the coefficient of mother’s partner effect; bfa: the coefficient of father’s actor effect; bfp: the coefficient of father’s partner effect.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations of marital conflict tactics and parenting practices are presented in Table 1 (for destructive marital conflict) and Table 2 (for constructive marital conflict), along with the bivariate correlations between them. Results provided initial support for associations between parents’ marital behavior and their own (within-person), as well as their spouse’s (cross-person), parenting behaviors. With regard to within-person correlations, frequent use of destructive tactics was related to forms of nonsupportive parenting behaviors for fathers (.13 ≤ γ ≤ 23, p < .05) and mothers (.15 ≤ γ ≤.21, p < .05), and frequent use of constructive tactics was related to forms of supportive parenting behaviors for fathers (.21 ≤ γ ≤ .26, p < .05) and mothers (.13 ≤ γ ≤ .17, p < .05). As for the cross-person correlation, statistically significant positive correlations were found between mothers’ destructive marital conflict tactics and forms of their spouse’s (fathers’) nonsupportive parenting (.13 ≤ γ ≤ .19, p < .05), as well as between mothers’ constructive marital conflict tactics and forms of their spouse’s (fathers’) supportive parenting (.14 ≤ γ ≤ .21, p < .05).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations for Destructive Marital Conflict and Multiple Forms of Nonsupportive Parenting Practices for Fathers (Above Diagonal) and Mothers (Below Diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MC_stonewall | — | .66** | .46** | .23**/.17* | .13**/.11 | .05/.10 | .24**/.14 | .16*/–.04 | .17* /.07 | 13.13 | 5.46 |

| 2. MC_verbal ag | .67** | — | .50** | .21**/.19** | .10/.13* | .10/.08 | .13/.17* | .12/.02 | .15*/.10 | 23.99 | 8.44 |

| 3. MC_physical ag | .52** | .53** | — | .19**/.17* | .16*/.08 | .07/.07 | .20**/.06 | .20**/–.03 | .17*/–.00 | 3.63 | 5.11 |

| 4. PP1_distress | .16* /–.04 | .21** /.02 | .12 /.05 | — | .54** | .44** | .55** | .37** | .30** | 2.90 | 0.74 |

| 5. PP1_punitive | .18*/–.10 | .10 /.01 | .04 /.08 | .47** | — | .67** | .29** | .52** | .37** | 2.55 | 0.83 |

| 6. PP1_minimizing | .15* /.00 | .11 /.12 | .10 /.11 | .33** | .67** | — | .22** | .39** | .47** | 3.07 | 0.94 |

| 7. PP2_distress | .16* /.06 | .19** /.05 | .03 /.06 | .68** | .49** | .36** | — | .57** | .39** | 2.85 | 0.70 |

| 8. PP2_punative | .14 /.06 | .01 /.07 | –.03 /.13 | .30** | .58** | .52** | .54** | — | .68** | 2.48 | 0.77 |

| 9. PP2_minimizing | .12 /.01 | .03 /.03 | .01 /.07 | .36** | .56** | .69** | .44** | .71** | — | 2.92 | 0.83 |

|

| |||||||||||

| M | 13.27 | 24.34 | 3.31 | 2.92 | 2.24 | 2.58 | 3.03 | 2.24 | 2.48 | ||

| SD | 5.22 | 8.73 | 4.36 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.8 | 0.88 | ||

Note. Numbers before the slash are within-person correlations, which are correlation coefficients among fathers’ (above diagonal) and mothers’ (below diagonal) scores. Numbers after the slash are cross-person correlations: Correlation coefficients for fathers’ marital conflict behaviors and mothers’ parenting practices are presented below the diagonal, and coefficients for mothers’ marital conflict behaviors and fathers’ parenting practices are presented above the diagonal. ag = aggression; MC = marital conflict; PP = parenting practice at Time 1 (PP1) or Time 2 (PP2).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations for Constructive Marital Conflict and Multiple Forms of Supportive Parenting Practices for Fathers (Above Diagonal) and Mothers (Below Diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MC_love and affection | — | .39** | .18**/.11 | .241**/ .11 | .21**/ .14* | .07/ .06 | .06/ −.03 | .10/ −.02 | 26.53 | 3.31 |

| 2. MC_editing | .27** | — | .23**/ .26** | .06/ .17** | .01/ .13* | .26**/ .21** | .12/ .13 | .12/ .12 | 31.38 | 4.96 |

| 3. PP1_expressive encouragement | .17**/ .13 | .16*/ .08 | — | .49** | .50** | .67** | .34** | .38** | 4.41 | 1.02 |

| 4. PP1_emotion-focused | .14*/ .18** | .08/ .05 | .46** | — | .80** | .37** | .60** | .54** | 5.36 | 0.78 |

| 5. PP1_problem-focused | .13*/ .14* | .05/ −.05 | .58** | .70** | — | .32** | .44** | .53** | 5.46 | 0.74 |

| 6. PP2_expressive encouragement | .03/ −.03 | .18*/ .09 | .65** | .23** | .37** | — | .52** | .57** | 4.33 | 1.03 |

| 7. PP2_emotion-focused | .05/ .13 | .09/ .06 | .36** | .55** | .42** | .41** | — | .76** | 5.11 | 0.79 |

| 8. PP2_problem-focused | .04/ .05 | .12/ .03 | .48** | .45** | .62** | .55** | .65** | — | 5.34 | 0.70 |

|

| ||||||||||

| M | 27.03 | 32.14 | 5.16 | 5.73 | 5.90 | 4.98 | 5.48 | 5.90 | ||

| SD | 3.58 | 4.99 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 1.06 | 0.80 | 0.66 | ||

Note. Numbers before the slash are within-person correlations, which are correlation coefficients among fathers’ (above diagonal) and mothers’ (below diagonal) scores. Numbers after the slash are cross-person correlations: correlation coefficients for fathers’ marital conflict behaviors and mothers’ parenting practices are presented below the diagonal, and coefficients for mothers’ marital conflict behaviors and fathers’ parenting practices are presented above the diagonal. MC = marital conflict; PP = parenting practice at Time 1 (PP1) or Time 2 (PP2).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Associations Between Marital Conflict Tactics and Forms of Parenting

We first examined within-parent links between each marital conflict tactic (i.e., stonewalling, physical aggression, and verbal aggression) and forms of nonsupportive (i.e., distress, punitive, and minimizing) reactions to children’s negative emotions for fathers and mothers (i.e., actor effects for both parents). Table 3 presents parameter estimates for these links. For mothers, the frequency of stonewalling, verbal aggression, and physical aggression were each statistically and negatively related to mothers’ own self-reported punitive parenting (b = –.21, –.25, –.27, respectively, all ps < .001). That is, when mothers reported more of these destructive conflict behaviors in marriage, they were less likely to respond to their child’s negative emotions in a punitive way. Similarly, mothers’ self-reported verbal aggression and physical aggression were negatively related to their minimizing reactions in parenting (b = –.14, p = .003; b = –.17, p = .025). That is, mothers’ higher verbal aggression and physical aggression were each linked to less use of minimizing responses to child’s negative emotions 2 years later. For fathers, we did not find statistically significant associations between marital relations and paternal parenting practices in these data.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates for the Actor and Partner Effects of Destructive Marital Tactics on Nonsupportive Parenting

| Punitive reactions

|

Minimizing reactions

|

Distress reactions

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | p | b | T | p | b | t | p | |

| Stonewalling | |||||||||

| Actor: Mother (bma) | −.21 | −3.44 | < .001 | −.05 | −0.86 | .391 | − .02 | − 0.46 | .645 |

| Actor: Father (bfa) | .11 | 1.32 | .188 | −.00 | −0.03 | .977 | .05 | 0.72 | .476 |

| Partner: Mother (bmp) | .10 | 1.27 | .204 | .11 | 1.51 | .134 | .17 | 2.65 | .009 |

| Partner: Father (bmp) | −.08 | −1.33 | .184 | −.06 | −0.77 | .445 | .01 | 0.17 | .863 |

| Verbal aggression | |||||||||

| Actor: Mother (bma) | −.25 | −5.49 | < .001 | −.14 | −3.01 | .003 | .01 | 0.12 | .904 |

| Actor: Father (bfa) | −.01 | − 0.31 | .761 | .01 | 0.19 | .849 | .01 | 0.41 | .680 |

| Partner: Mother (bmp) | .05 | 1.41 | .160 | .06 | 1.78 | .077 | .04 | 1.07 | .285 |

| Partner: Father (bmp) | −.02 | −0.48 | .634 | −.05 | −0.81 | .419 | .03 | 0.74 | .458 |

| Physical aggression | |||||||||

| Actor: Mother (bma) | − .27 | −3.53 | < .001 | −.17 | −2.26 | .025 | −.08 | −1.23 | .220 |

| Actor: Father (bfa) | .05 | 1.36 | .174 | −.01 | − 0.25 | .801 | .06 | 1.67 | .096 |

| Partner: Mother (bmp) | .01 | 0.38 | .708 | −.05 | −1.43 | .154 | .02 | 0.53 | .595 |

| Partner: Father (bmp) | −.14 | −1.73 | .086 | −.15 | −1.66 | .099 | .04 | 0.53 | .598 |

With regard to the cross-person associations indicated by partner effects, paternal self-reported stonewalling behavior in marital conflict was positively associated with maternal distressed reactions (b = .17, p = .009). That is, when their husband reported more destructive stonewalling behaviors in face of conflict, mothers tended to react in more unsupportive ways to their child’s negative emotions. Finally, no statistically significant relations emerged between any destructive marital conflict behaviors displayed by mothers and unsupportive responses shown by fathers.

Additionally, we did not find statistically significant effects of constructive marital tactics on supportive parenting for either fathers or mothers. Neither of the parents’ constructive martial tactics predicted their own or their spouse’s supportive parenting 2 years later.

Differences in Marital Conflict–Parenting Links: Mothers Versus Fathers

By applying the interaction model under the APIM framework, we further tested our second research question regarding parent gender differences in the actor and partner effects of marital conflict on parenting behaviors. Statistically significant gender differences in actor effects were found between destructive tactics in marital conflict and punitive responses to distressed children (b = .16, p = .002; b = .12, p < .001; b = .16, p < .001, for stonewalling, verbal aggression, and physical aggression, respectively), indicating that the negative association (i.e., compensatory effect) between one parent’s self-reported destructive marital conflict and his or her own punitive responses in parenting was only evident for mothers. Gender differences in actor effects also existed between parents’ self-reported verbal aggression in marital conflict (b = .07, p = .028) and their own minimizing reactions in parenting. Although these data did not provide sufficient statistical confidence to conclude that there is a difference in the population from which the sample was drawn, there seemed to be a meaningful gender difference between parental self-reported physical aggression in marital conflict and their self-reported minimizing behaviors in parenting (b = .08, p = .065). Mothers’ self-reported aggressive conflict tactics were more likely to predict their own parenting difficulties in comparison to the effect of fathers’ self-reported aggressive marital behavior on fathers’ own parenting difficulties. As for cross-person effects, the interaction models did not find statistically significant gender differences for any partner effect between one parent’s destructive marital tactics and the partner’s unsupportive parenting.

Discussion

Considerable empirical and theoretical attention has been devoted to understanding the association between marital and parent–child subsystems. The direction and magnitude of these links, however, remain unclear because of the mixed findings in the literature (Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Moreover, the dyadic-level constructs, marital conflict and parenting, were typically measured by averaging reports from both spouses (Kaczynski et al., 2006; Kenny et al., 2006; Sturge-Apple, Davies, Boker, & Cummings, 2004), yet their interdependent relational nature has been overlooked. Applying the APIM to account for the dyadic nature of family relationships, the main aim of the present study was to address the aforementioned research gaps by examining constructive and destructive marital conflict tactics as predictors of parenting practices when children express negative emotions. In general, our findings indicated that parents’ destructive marital conflict tactics influenced their way of coping with children’s negative emotions 2 years later, but the influence operated differently for fathers and mothers, reflected in both the within-person and cross-person processes.

For mothers, we found that mothers’ unsupportive parenting tended to increase with more fathers’ self-reported destructive conflict behaviors. For example, higher frequencies of fathers’ stonewalling behavior predicted their wives’ increased distress reactions to their children displaying negative emotions. Although past studies have consistently found that destructive marital conflict has deleterious effects on parenting in the within-person links (e.g., Davies et al., 2009; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000), our study is among the first to show this effect from a dyadic perspective that accounts for the cross-person effects of family relationships. Results suggested that mothers’ parenting is influenced by their spouse’s (i.e., fathers’) way of destructively dealing with disagreements in marital interactions, indicating the interdependent and relational natural of family relationships. Father’s self-reported destructive marital strategies affected the mother, resulting in higher levels of negativity in the mother’s self-reported parenting behaviors. Thus, destructive conflict behaviors displayed by fathers in the marital subsystem may spillover to negativity in the mother–child subsystem, leading to mothers’ greater tendency toward engaging in unsupportive parenting practices.

Interestingly, mothers’ tendency to engage in unsupportive parenting was also predicted by their own self-reported destructive conflict tactics, but in a manner suggestive of compensatory effects. Specifically, higher levels of stonewalling, verbal aggression, and physical aggression in marital conflict reported by mothers were associated with their lower punitive reactions to child distress. Higher levels of maternal self-reported aggressive behaviors (i.e., verbal aggression and physical aggression) also predicted mothers’ less minimizing responses to distressed children 2 years later. These findings indicated that mothers were less likely to engage in undesirable parenting in association with their own destructive marital conflict behavior, supporting the compensatory hypothesis. One possible interpretation is that mothers were seeking to buffer the child from the negative impact of their own destructive conflict behaviors in the marital relationship (Brody et al., 1986; Emery, 1982; Engfer, 1988). Our study thus corroborated the findings of previous cross-sectional studies (e.g., Brody et al., 1986; Nelson et al., 2009), supporting a compensatory hypothesis in a longitudinal model tested over a 2-year period. However, the findings did not provide strong support for the compensatory hypothesis because mothers reduced their incidence of unsupportive behavior rather than increased their supportive parenting behaviors.

Collectively, the findings presented here concerning maternal parenting suggest that mothers’ own and their spouse’s (fathers’) behaviors in the face of marital conflict may have different implications for maternal parenting practices. Although mothers tended to regulate and restrain their unsupportive parenting toward the child after their own destructive reactions to marital conflict, they were more likely to engage in unsupportive parenting if their partner (i.e., fathers) used more destructive strategies in marital interactions. It could be that the parental role was more evident for mothers in the within-person link (actor effect) than the cross-person link (partner effect): Having two roles at the same time (i.e., a mother and a wife), mothers may be more aware of their role as a parent when they themselves display destructive marital conflict. As a result, mothers may be more likely to put effort into reducing their negative responses in parenting the child in the context of their own destructive marital conflict behaviors. Conversely, when the destructive behaviors are initiated by their spouse (i.e., fathers), such as refusing to openly discuss disagreements or aggressively reacting to marital conflict, mothers may be less aware of their parental role. Negativities displayed by the spouse may pose a potential threat to many aspects of mothers’ life, including their ability to provide responsive and involved parenting.

In addition, the actor versus partner differences in maternal parenting may find support from the literature of co-parenting (McHale et al., 2002). Quality of coordination with the spouse in his or her parental role is important for parents to provide qualified parenting. Compared with being the agent (i.e., actor) of destructive conflict tactics, being the target (i.e., partner) of destructive conflict may pose greater threat to mothers’ experience of co-parenting support from their spouse and, ultimately, their caregiving behaviors (Bonds & Gondoli, 2007). Following the present study’s documentation of the interdependent and mutually influencing association between marital conflict and parenting for fathers and mothers, future studies that explore the mechanisms and processes underling spillover and crossover effects are needed, examining potential accounts such as the spouse–parent role differentiation and co-parenting explanations proposed earlier.

For fathers, we did not find statistically significant associations between marital relations and paternal parenting practices. This null finding for fathers was unexpected considering past literature had found the state of the marital relationship to be a more cogent precursor of parenting role among fathers than mothers (Belsky, Gilstrap, & Rovine, 1984). In fact, in these data, mothers’ unsupportive parenting practices relative to those of fathers were more affected by destructive marital conflict strategies, which is one of the few results directly inconsistent with the fathering vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings et al., 2010). Although the hypothesis has been supported by some empirical work showing that the association between parents’ marital functioning and parenting are more evident for fathers than for mothers (Davies et al., 2009; Stroud et al., 2011), other studies did not find any difference between paternal and maternal links (Erel & Burman, 1995; Ponnet et al., 2013). Exploring circumstance under which gender differences are more evident or factors that may moderate the strength of gender effects in family relationships are important next steps for future research.

No association between constructive marital tactics and forms of supportive parenting was found in our longitudinal dataset. This may be a result of the rigor of our longitudinal autoregressive test. By taking parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions at Time 1 into account, we were able to examine changes of parents’ parenting practices that were influenced by their own and their spouse’s conflict-coping strategies. Our rigorous approach including autoregressive controls for Time 1 parenting may have contributed to the null results, considering the relative stability of parenting practices (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). Another explanation may involve differences in the conceptualization of marital relationships. Several reviews have indicated that an overt destructive conflict style, which is indicative of aggression and violence, is more strongly associated with negative parenting behaviors (e.g., Fincham, Grych, & Osborne, 1994; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000) than other aspects of marital relationships, such as the constructive marital behaviors examined in our study or a general evaluation of overall marital quality (e.g., Ponnet et al., 2013). These speculations warrant examination in future longitudinal research that tracks changes of the marriage–parenting link and encompasses different aspects of marital relationships.

Our study contributes to the current body of research using rigorous statistical methods to examine the associations of marital conflict tactics and parents’ emotion socialization practices for mothers and fathers. Utilizing the APIM, our study is one of the first to examine systemic patterns of cross-person influence between spouses as well as gender differences in the associations between marital conflict and parenting practices. In addition, we focus on specific marital conflict behaviors and their influence on caregiving behaviors (i.e., parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions), delineating the associations between marital and parent–child subsystems on a finer scale than overall ratings of marital quality and parenting.

Limitations

Despite its advantages, the present study is not without limitations. First, the results from our relatively representative community sample may not apply to at-risk or clinical families. Stronger spillover from the marital subsystem to the parent–child subsystem may exist for families with high levels of marital hostility or for parents who have difficulties in emotion regulation. In addition to the issues of generalizing our findings to higher risk samples, caution should also be exercised in generalizing the findings to other developmental periods. Although the well-defined developmental period in this study (i.e., kindergarten) holds great implications for understanding the interrelations between family relationships for children specifically at this age period, future research including a more diverse sample and wider developmental period is needed to advance the generalizability of the findings to a broader population.

Second, the reliance on self-report measures from the parents’ perspective may have also limited the generalizability of our findings. Parents’ behaviors reported in survey measures may not always be in accordance with their actual behaviors when observed. Therefore, including child report and behavioral observations when assessing constructs such as marital conflict and parenting practices may further facilitate examination of family interactions and offset additional limitations associated with the use of survey data (Margolin et al., 2004).

Third, we did not address the question as to why and how marital conflict compromises parenting. An important step toward a fine-grained understanding of different effects of constructive and destructive marital conflicts is to identify potential factors that may mediate or moderate these effects (Davies et al., 2009).

Finally, the results only concerned parenting practices regarding responses to children’s negative emotions and may not generalize to the wide range of other possible parenting behaviors. In addition, marital conflict behaviors were the only predictors of parenting examined in our study, yet other factors such as child characteristics, parental psychopathology, and contexts of emotional events (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998), as well as familial changes over the 2-year period remained unaccounted for. Future studies will benefit from incorporating assessment of different aspects of a family and changes in family characteristics as predictors of various types of parenting behaviors.

Implications

Its limitations noted, this study nonetheless has important implications both theoretically and practically. Over the developmental period of 2 years, destructive marital conflict tactics predicted subsequent unsupportive parenting for mothers. Prospective associations among marital conflict tactics and parenting practice varied across mothers and fathers: Although fathers’ destructiveness in the marital relationship predicted their spouses’ (mothers’) unsupportive parenting practices, mothers’ self-report of their marriage destructiveness was prospectively associated with their own decreased unsupportiveness in response to children’s negative emotions. In terms of the practical implications of this study, the predictive associations among marital conflict tactics and parents’ socialization practices suggest that parenting training programs may benefit from emphasizing the predictive association between marital conflict tactics and parenting behaviors. Indeed, there is evidence showing that parent training programs that focus exclusively on parenting skills are mostly likely to fail for those families who have conflicted or distressed marriages (e.g., Webster-Stratton, 1994) and that programs focused on marital conflict interactions might have positive effects (Cowan & Cowan, 2002).

In addition, the cross-person effects found in our study suggest that both fathers and mothers should be included in intervention or prevention programs. For example, mothers who have learned effective interparental problem-solving strategies themselves may continue to be susceptible to exhibiting unsupportive parenting behaviors when their spouse (i.e., the father) is unable to reduce their destructive marital tactics. Thus, integrative interventions on marital conflict and parenting practice, targeting fathers and mothers simultaneously, are strongly encouraged to promote positive parenting.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 MH57318 from the National Institutes of Health, awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings.

Contributor Information

Mengyu (Miranda) Gao, University of Notre Dame.

Han Du, University of California–Los Angeles.

Patrick T. Davies, University of Rochester

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Arellano CM, Markman HJ. The Managing Affect and Differences Scale (MADS): A self-report measure assessing conflict management in couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:319–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.9.3.319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barletta J, O’Mara B. A review of the impact of marital conflict on child adjustment. Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2006;16:91–105. doi: 10.1375/ajgc.16.1.91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Gilstrap B, Rovine M. The Pennsylvania infant and family development project, I: Stability and change in mother–infant and father–infant interaction in a family setting at one, three, and nine months. Child Development. 1984;55:692–705. doi: 10.2307/1130122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee S. The multiple determinants of parenting. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental psychopathology. 2nd. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 38–85. (Risk, disorder and adaptation). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Youngblade L, Rovine M, Volling B. Patterns of marital change and parent–child interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:487–498. doi: 10.2307/352914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Buehler C, Gerard JM. Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: Spillover via maternal acceptance, harshness, inconsistency, and intrusiveness. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:428–454. doi: 10.1177/0272431608316602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonds D, Gondoli DM. Examining the process by which marital adjustment affects maternal warmth: The role of coparenting support as a mediator. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;2:288–296. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Pellegrini AD, Sigel IE. Marital quality and mother–child and father–child interactions with school-aged children. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:291–296. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.3.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Anthony C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Gerard J, Pemberton S. Interparental conflict and youth problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Burman B, Margolin G, John RS. America’s angriest home videos: Behavioral contingencies observed in home reenactments of marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:28–39. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.61.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Zeman J. Influence of gender on parental socialization of children’s sadness regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:210–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00381.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development and psychopathology. Development and psychopathology. 2002;14:731–759. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Harter H. Interparental conflict and parent–child relationships. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Children’s responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development. 2003;74:1918–1929. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, George MW. Fathers, marriages, and families: Revisiting and updating the framework for fathering in family context. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 5th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire DH, Weinraub M. The stability of parenting behaviors over the first 6 years of life. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2005;20:201–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2005.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Does gender moderate the effects of marital conflict on children? In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 64–97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cummings EM. Interdependencies among interparental discord and parenting practices: The role of adult vulnerability and relationship perturbations. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:773–797. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Woitach MJ, Cummings EM. A process analysis of the transmission of distress from interparental conflict to parenting: Adult relationship security as an explanatory mechanism. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1761–1773. doi: 10.1037/a0016426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55376-4_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, Murphy BC. Mothers’ emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Easterbrooks MA. Assessing emotional availability in early development. In: Frankenburg WK, Emde RN, Sullivan J, editors. Early identification of children at risk: An international perspective. New York, NY: Plenum; 1985. pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:310–330. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.92.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engfer A. The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother–child relationship. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1988. pp. 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Bernzweig J. Coping with children’s negative emotions scale (CCNES): Descriptions and scoring. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University; 1990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes R, Poulin R, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich D. The Coping With Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;34:285–310. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Leonard SA, Kupanoff K, Martin CL. Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: Relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Development. 2001;72:907–920. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Understanding the association between marital conflict and child adjustment: Overview. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:123–127. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.8.2.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Grych JH, Osborne L. Does marital conflict cause child maladjustment? Directions and challenges for longitudinal research. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:128–140. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.8.2.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. The social psychophysiology of marriage. In: Noller P, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Perspectives on marital interaction. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters; 1988. pp. 182–200. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Marital relationships and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Fincham FD, Osborne LN, Conger RD. Mom and Dad are at it again: Adolescent perceptions of marital conflict and adolescent psychological distress. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:333–350. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski KJ, Lindahl KM, Mailik NM, Laurenceau JP. Marital conflict, maternal and paternal parenting, and child adjustment: A test of mediation and moderation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:199–208. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1996;1996:57–76. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. Analyzing mixed independent variables: The actor–partner interdependence model; pp. 144–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The conflicts and problem-solving scales. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:454–473. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.4.454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klausli JF, Owen MT. Exploring actor and partner effects in associations between marriage and parenting for mothers and fathers. Parenting. 2011;11:264–279. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.613723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations. 2000;49:25–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Zarit SH, Rovine MJ, Birditt K, Fingerman KL. The interdependence of relationships with adult children and spouses. Family Relations. 2016;65:342–353. doi: 10.1111/fare.12188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Boggio RM, Jouriles EN. Effects of verbal marital conflict on subsequent mother–son interactions in a child clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:262–271. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, Oliver PH. Links between marital and parent–child interactions: Moderating role of husband-to-wife aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:753–771. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Khazan I, Erera P, Rotman T, DeCourcey W, McConnell M. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Being and becoming a prent. 2nd. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 75–107. (Handbook of parenting). [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, O’Brien M, Blankson AN, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Family stress and parental responses to children’s negative emotions: Tests of the spillover, crossover, and compensatory hypotheses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:671–679. doi: 10.1037/a0015977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro MF, Ribeiro T, Shelton KH. Marital satisfaction and partners’ parenting practices: The mediating role of coparenting behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:509–522. doi: 10.1037/a0029121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Mortelmans D, Wouters E, Van Leeuwen K, Bastaits K, Pasteels I. Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal Relationships. 2013;20:259–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud CB, Durbin CE, Wilson S, Mendelsohn KA. Spillover to triadic and dyadic systems in families with young children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:919–930. doi: 10.1037/a0025443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple M, Davies PT, Boker S, Cummings EM. Interparental discord and parenting: Testing the moderating roles of child and parent gender. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:361–380. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0404_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Cummings EM. Impact of hostility and withdrawal in interparental conflict on parental emotional unavailability and children’s adjustment difficulties. Child Development. 2006;77:1623–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census 2000. 2000 [Data file]. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- Webster-Stratton C. Advancing videotape parent training: A comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:583–593. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.62.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L. Contagion in family affection: Mothers, fathers, and young adult children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:284–294. doi: 10.2307/353748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]