Abstract

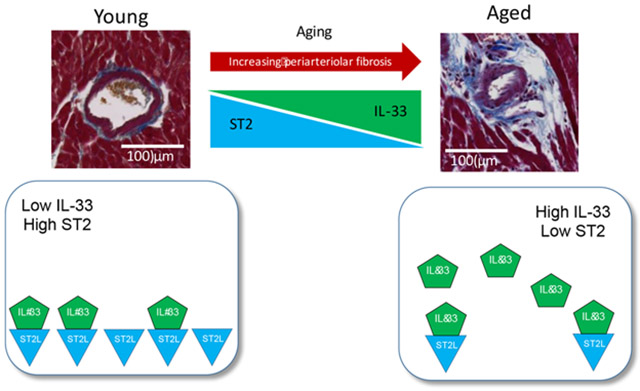

Microvascular dysfunction in the heart and its association with periarteriolar fibrosis may contribute to the diastolic dysfunction seen in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Interleukin-33 (IL-33) prevents global myocardial fibrosis in a pressure overloaded left ventricle by acting via its receptor, ST2 (encoded by the gene, Il1rl1); however, whether this cytokine can also modulate periarteriolar fibrosis remains unclear. We utilized two approaches to explore the role of IL-33/ST2 in periarteriolar fibrosis. First, we studied young and old wild type mice to test the hypothesis that IL-33 and ST2 expression change with age. Second, we produced pressure overload in mice deficient in IL-33 or ST2 by transverse aortic constriction (TAC). With age, IL- 33 expression increased and ST2 expression decreased. These alterations accompanied increased periarteriolar fibrosis in aged mice. Mice deficient in ST2 but not IL-33 had a significant increase in periarteriolar fibrosis following TAC compared to wild type mice. Thus, loss of ST2 signaling rather than changes in IL-33 expression may contribute to periarteriolar fibrosis during aging or pressure overload, but manipulating this pathway alone may not prevent or reverse fibrosis.

Keywords: interleukin-33, ST2, myocardial fibrosis, periarteriolar fibrosis, pressure overload, aging

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Numerous stimuli can cause myocardial fibrosis, including cardiac ischemia or infarction, pressure overload, aging, pathogen or drug exposure, or an underlying gene defect, all of which lead to abnormal accumulation of extracellular matrix in the heart and can promote subsequent heart failure [1]. Distinct types of myocardial fibrosis – namely, interstitial, periarteriolar, or “replacement” fibrosis – may result from different underlying pathophysiologic processes, rendering the development of therapies to treat myocardial fibrosis challenging. The role of coronary microvascular dysfunction in the pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has increased attention to understanding the mechanisms of development of periarteriolar fibrosis in the heart [2-4].

Periarteriolar fibrosis may contribute to the microvascular dysfunction seen in diastolic dysfunction, thus contributing to the considerable population of patients with HFpEF [5]. In particular, microvascular dysfunction associated with chronic systemic inflammation may promote periarteriolar fibrosis and microvascular rarefaction, yielding decreased coronary flow reserve, impaired diastolic function, and the development of heart failure symptoms and/or angina with “normal” coronary arteries [2, 6-10]. Microvascular dysfunction also contributes to ventricular impairment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [11]. While endothelial dysfunction due to chronic hypertension may impair nitric oxide bioavailability, it remains unclear if this deficiency drives periarteriolar fibrosis [12, 13]. Chronic angiotensin II-induced hypertension in mice leads to excess collagen deposition from multiple cell types, including endothelial cells, Sca-1+ bone marrow-derived cells, fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells [14], therefore multiple mechanisms may contribute microvascular dysfunction – particularly periarteriolar fibrosis – seen in hypertensive disease.

The cytokine interleukin-33 (IL-33), a member of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) superfamily, was first identified in 2005 as the ligand for the suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2) receptor (encoded by the gene, interleukin 1 receptor like 1, or Il1rl1). Our group previously demonstrated cardioprotective actions of IL-33, and that this cytokine can prevent development of global myocardial fibrosis in pressure overloaded mouse hearts [15]. Specifically, pressure overload leads to secretion of IL-33 from endothelial cells, and suppression of this signaling promotes cardiac hypertrophy and increased global myocardial fibrosis. Augmentation of IL-33 with beta blocker therapy can ameliorate ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction [16], and IL-33 administration following myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury reduces the post-injury inflammatory response and attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis [17].

Since our initial findings, others have demonstrated that IL-33 can exert pro- inflammatory and pro-fibrotic effects in other organs, such as in the lungs [18-20], liver [21], skin [22], and gastrointestinal system [23]. In addition, some have suggested that IL-33 can boost cardiac inflammation, as increased levels of IL-33 associate with worse global myocardial fibrosis in patients undergoing placement of a ventricular assist device [24]. Furthermore, higher levels of IL-33 predict in-stent restenosis following myocardial infarction [25]. To address these discrepancies, we used distinct experimental approaches in mice to challenge our prior hypothesis that IL-33 is anti-fibrotic in the heart and to investigate specifically whether IL-33 mediates periarteriolar fibrosis.

We tested the role of the IL-33/ST2 system using two independent approaches that produce periarteriolar fibrosis in the mouse myocardium – first, aging, and second, pressure overload. Given that myocardial fibrosis increases with age, we hypothesized that IL-33 decreases with age in the heart, and that impaired function of this cardioprotective cytokine contributes to age-related myocardial fibrosis. Unexpectedly, we found that IL-33 actually increases during aging but that ST2 expression decreases with age in the heart. These results raise the possibility that myocardial and periarteriolar fibrosis develop with age due to a reduction in ST2 expression in the heart. Furthermore, we utilized transverse aortic constriction (TAC) to produce pressure overload to simulate microvascular changes seen in conditions such as HFpEF. We hypothesized that periarteriolar fibrosis would increase in mice deficient in IL-33 or ST2 following TAC; however, we only observed a significant increase in periarteriolar fibrosis in mice deficient in ST2 but not IL-33 compared to wild type mice. Finally, we observed that substrains of C57Bl/6 mice from different vendors had different levels of periarteriolar fibrosis, highlighting the importance of the use of appropriate controls particularly in aging studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Wild type (WT) (C57Bl/6) mice were purchased from the National Institute on Aging (C57Bl/6JN, young and aged mice used for aging experiment, abbreviated “NIA”) or Charles River Laboratories (C57Bl/6NCrl, young mice used for TAC experiment, abbreviated “CR”). Mice deficient in IL-33 (Il33−/−) were generously provided by the Chen lab (Dr. Wei-Yu Chen, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan) [26]. Mice deficient in ST2 (Il1rl1−/−) were generously provided by the McKenzie lab (Dr. Andrew McKenzie, Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, United Kingdom) [27]. For clarification, we use the HGNC- approved gene symbol, Il1rl1, to denote the gene encoding ST2, while we use sST2 and ST2L to denote proteins by convention. In the aging study, WT (NIA and CR) hearts were harvested at 2 months (young) or 21-24 months (aged). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

2.2. Transverse aortic constriction

Young male and female mice of all three genotypes (WT (CR only), Il33−/−, Il1rl1−/−) were randomized to sham or transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery at 2 months of age. TAC and sham surgeries were performed as previously described [28]. Tissues were harvested at 5 weeks post-surgery (3 months of age) and specimens were flash frozen for subsequent extraction of mRNA or protein or fixed and processed for histological analysis.

2.3. Histological analysis

Tissues were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 24 hours then transferred to 70% ethanol prior to embedding in paraffin. Slides were stained with Masson’s trichrome stain then sections were scanned at 20x with an AxioScan.z1 (Zeiss). Periarteriolar fibrosis was analyzed by three blinded readers using Fiji (ImageJ); representative results from a single reader are shown. Periarteriolar fibrosis ratios were quantified for arterioles in the left ventricle (including the septum) from sections cut in cross-section at the level of the papillary muscles only; vessels without a visible smooth muscle layer were excluded. The periarteriolar fibrosis ratio was calculated as the fibrotic area divided by the vessel wall area (excluding the lumen) [2, 3, 29]. Global fibrosis was calculated using a Python program that quantified the number of blue pixels (representing collagen) as a percentage of the total number of pixels represented by the heart tissue cut in cross-section at the level of the papillary muscles (left and right ventricles included). Cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area was determined by measuring cardiomyocytes with a visible central nucleus in cross section with Fiji (ImageJ).

2.4. Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Heart tissues taken from the apex were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen at harvest until further processing. mRNA was extracted from heart tissue samples in Ribozol followed by the E.Z.R.N.A. Total RNA kit I (Omega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosciences). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). For SYBR reactions, the following mouse primers were used: TATA binding protein (TBP) (forward: 5’-ACCCTTCACCAATGACTCCTATG-3’, reverse: 5’-TGACTGCAGCAAATCGCTTGG-3’), IL-33 (forward: 5’-GGTGTGGATGGGAAGAAGCTG-3’, reverse: 5’-GAGGACTTTTTGTGAAGGACG-3’), total ST2 (forward: 5’-ACGCTCGACTTATCCTGTGG-3’, reverse: 5’-CAGGTCAATTGTTGGACACG-3’) [30] and ST2L (forward: 5’-GTGATAGTCTTAAAAGTGTTCTGG-3’, reverse: 5’-TCAAAAGTGTTTCAGGTCTAAGCA-3’) [30]. Expression levels of IL-33 and ST2 were normalized to levels of TBP.

2.5. Western analysis

For western analysis, heart tissue taken from the apex was homogenized, and total protein was extracted in RIPA buffer then quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). Samples were stored at −80°C or were used immediately in western analysis. Samples containing 20 μg of total protein were prepared in Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) then loaded into a Mini-Protean TGX Precast Gel (Bio-Rad). Gels were run with Tris/SDS buffer in a Mini-Protean Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis Cell (Bio-Rad) at 80-100 V. The Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Goat anti-mouse IL-33 (AF3626, R&D) or rabbit anti-vinculin (ab73412, loading control) primary antibodies were added following membrane blocking in 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature on a plate shaker. The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (Bio-Rad) or rabbit anti-goat HRP-conjugated (Bio-Rad) in 5% milk.

2.6. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Blood was collected in serum separation tubes (SST) at the time of harvest by retro-orbital collection. The tube was allowed to clot at room temperature for at least 30 minutes prior to centrifugation at 2000 g for 5 minutes. Serum was transferred to clean microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −80 deg C until further use. Serum ST2 concentration was quantified using the mouse ST2/IL-33R Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum amyloid A (SAA) concentration was quantified using the Mouse Serum Amyloid A DuoSet assay (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7. Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless noted otherwise. Individual vessels were used to evaluate statistical differences in periarteriolar fibrosis. Individual mice were used to evaluate statistical differences in global fibrosis, and morphometric parameters. Data presented that did not exhibit normal distribution by the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test (including perivascular fibrosis) or had a sample size too small to determine normality were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests as indicated. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Periarteriolar fibrosis increases with age in the heart

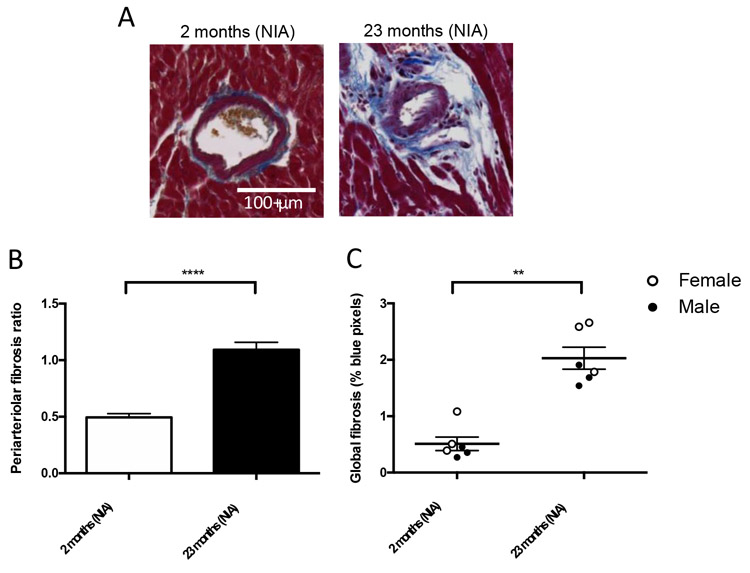

Heart tissues from male and female WT mice aged 2 and 23 months of age (NIA) were harvested for histological analysis and mRNA and protein quantification. Both periarteriolar fibrosis and global myocardial fibrosis increase with age in WT mice from the NIA (Figure 1). The fibrosis results shown combine data for males and females as we did not detect statistically different results between sexes (periarteriolar fibrosis by sex shown in Supplemental Figure 1A). Serum amyloid A (SAA) serum concentration was measured as a marker of systemic inflammation; there was no difference between groups (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Periarteriolar fibrosis increases with age in WT mice. (A) Representative histology of periarteriolar fibrosis from young (2 months, NIA) and aged (23 months, NIA) WT mice stained with Masson’s trichrome stain. (B) Periarteriolar fibrosis ratio calculated by individual vessel is significantly increased at 23 months of age compared with young (NIA): n= 58 vessels/group (in 6 mice total (3 males and 3 females), old (NIA): n=64 vessels (in 6 mice total (3 males and 3 females)), ****p<0.0001 by Mann-Whitney test. (C) Global myocardial fibrosis calculated as % blue pixels per total heart pixels is significantly increased at 23 months of age compared with 2 months of age, n=6 mice/group (combined genders), **p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney test.

3.2. IL-33 expression increases with age in the heart

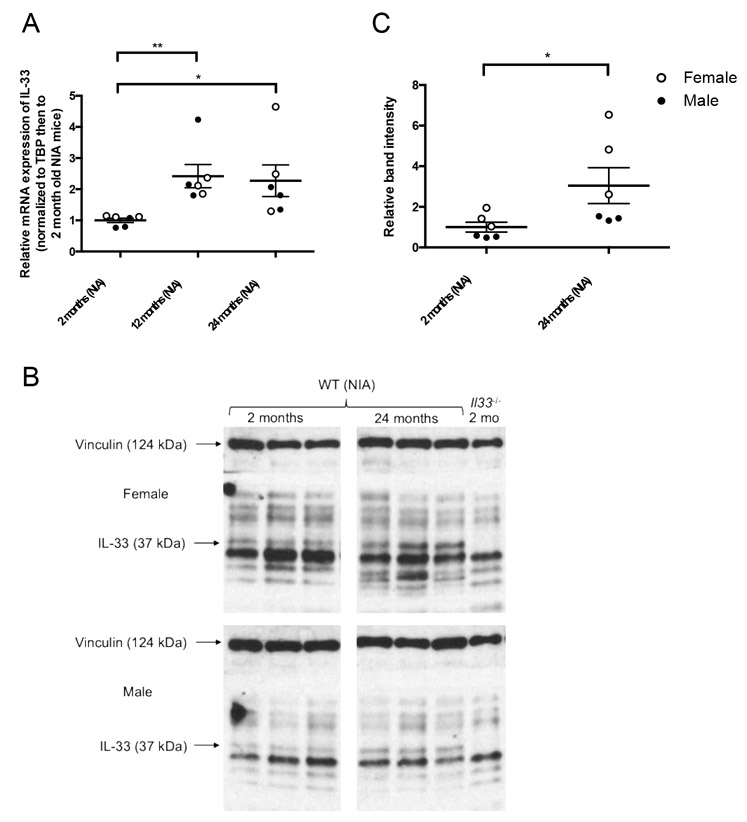

In WT C57Bl/6JN mice from the NIA, IL-33 mRNA expression increased significantly at 12 and 24 months of age compared to 2 months of age (Figure 2A). Protein expression of the full-length IL-33 (∼30 kDa but detected at ∼37 kDa according to the antibody manufacturer) in the heart increased significantly in aged 24-month-old mice compared to young 2-month-old mice by western analysis (Figure 2B and C).

Figure 2.

IL-33 expression in the heart increases with age. (A) IL-33 mRNA expression in the heart at 2, 12, and 24 months of age in WT mice from the NIA. Values are normalized to housekeeping gene TATA-binding protein (TBP) then to young hearts. N=6 (3 males, 3 females) per age. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (B) Representative image of western analysis of IL-33 protein expression in the heart at 2, 12, and 24 months of age with vinculin used as a loading control protein. Arrows indicate relevant bands, with noticeable absence of the IL-33 band in the Il33−/− mouse. Identities of the additional bands are not known. (C) Relative band intensity IL-33 by western analysis at 2 and 24 months of age in WT mice from the NIA. *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney test.

Because both periarteriolar fibrosis and IL-33 increase with age, we tested the hypothesis that IL-33 stimulates fibrosis during aging, despite our previous findings that it is anti-fibrotic in pressure overload [15]. First, we augmented circulating levels of IL-33 in young WT mice (2 months old, CR) by daily intraperitoneal injections of 2 μg of recombinant human IL-33 for six weeks. Contrary to the hypothesis, there was a non-significant trend toward decreased periarteriolar fibrosis (Supplemental Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C). Next, we attempted to decrease circulating levels of IL-33 in aged mice. In a loss of function study, aged (21-month-old) mice received 4 μg of neutralizing goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody to IL-33 (R&D; AF3626) or IgG control for 3 weeks via daily intraperitoneal injection. Periarteriolar fibrosis did not differ significantly between groups (Supplemental Figures 2D, 2E, and 2F). Finally, we supplemented circulating levels of IL-33 in aged mice. Aged (21-month-old) mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of 2 μg of recombinant human IL-33 or saline for 10 days, with no significant difference in periarteriolar fibrosis seen between groups (Supplemental Figures 2G, 2H, and 2I).

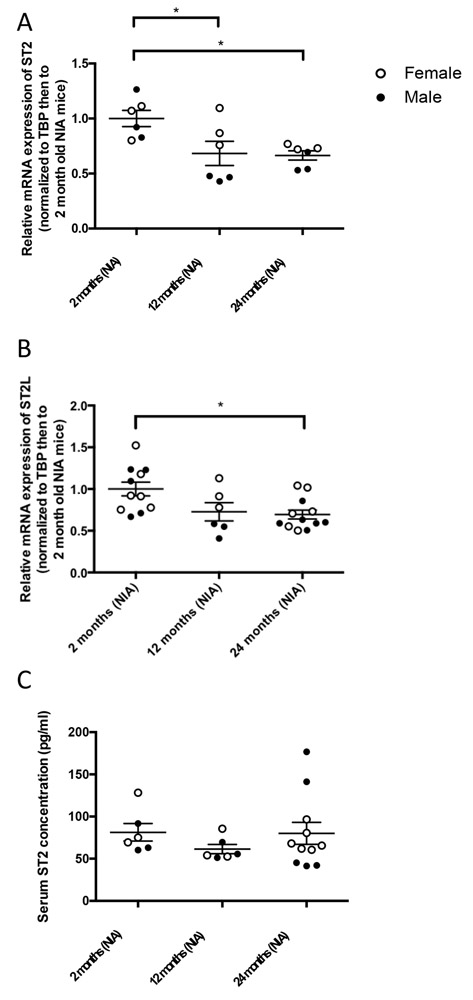

3.3. ST2 expression decreases with age in the heart

Contrary to IL-33, total ST2 expression decreased with age in the heart (Figure 3). Because the commercially available Taqman probe spans exons 3-4, common to both ST2L and sST2, distinguishing between ST2L and total ST2 used specific primer sets. Total ST2 expression decreased with age in the heart, comparing 12- and 24-month-old WT mice to 2- month-old WT mice from the NIA (Figure 3A). There was also a significant decrease in ST2L expression in 24-month-old WT mice compared to 2-month-old WT mice from the NIA, with a similar non-significant trend seen at 12 months versus 2 months (Figure 3B). Total ST2 or ST2L did not differ significantly at 12 and 24 months of age. We did not detect ST2 by western analysis, likely due to ST2 protein content below the limit of detection (with recombinant ST2, limit of detection was between 10-100 μg, data not shown). Due to opposing effects of ST2L and sST2, deficiency of one or the other might have different implications. Because the transcript for sST2 completely overlaps with ST2L, we did not quantify sST2 transcript separately, but we did measure serum levels of sST2. Serum concentrations of sST2 measured by ELISA showed no significant change with age (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

ST2 expression decreases with age. (A) mRNA expression of total ST2 in the heart at 2, 12, and 24 months of age in WT mice from the NIA. Values normalized first to TBP then to young mice. N=6/group (3 male, 3 female), *p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (B) mRNA expression of ST2L in the heart, normalized first to TBP then to young mice. N=6/group (3 male, 3 female), *p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Serum concentrations of sST2 by ELISA at 2, 16, and 24 months of age in male and female WT mice from the NIA.

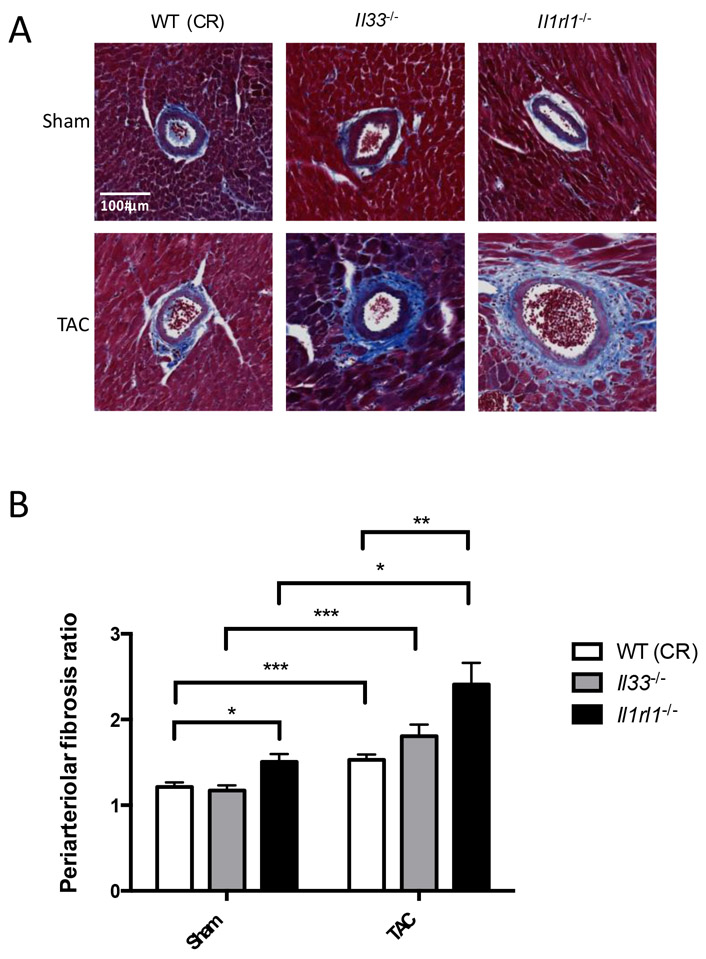

3.4. ST2 deficient mice show increased periarteriolar fibrosis in myocardial arterioles

Periarteriolar fibrosis increased significantly in Il1rl1−/− mice compared to WT (CR) mice following TAC (Figure 4). There was a non-significant trend toward increased periarteriolar fibrosis in Il33−/− mice compared to WT following TAC. SAA levels assessed systemic inflammation and did not differ significantly between groups although there was a nonsignificant trend toward increased SAA concentration after TAC in all genotypes (Supplementary Figure 3). In addition, periarteriolar fibrosis in unoperated young (2 month old) and middle aged (16 month old) Il33−/− and Il1rl1−/− mice showed significant increases with age, and there was a non-significant trend toward increased periarteriolar fibrosis in Il33−/− and Il1rl1−/− mice compared to WT (NIA) unoperated mice at 16 months of age (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Periarteriolar fibrosis increases in mice deficient in either IL-33 or ST2 following pressure overload due to transverse aortic constriction (TAC). (A) Representative photomicrographs of periarteriolar fibrosis in WT, Il33−/−, and Il1rl1−/− mice five weeks after sham versus TAC surgery. (B) Calculated periarteriolar fibrosis ratio by individual vessel, n=86-253 vessels/group from a total of 3-11 mice/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

3.5. Degree of periarteriolar fibrosis depends on C57Bl/6N substrain

Mice used in the aging study were obtained from the NIA (young and old) while mice used for TAC were obtained from Charles River. Due to concerns that mice from different vendors had a different phenotype, we also harvested tissues from young, unoperated mice from Charles River. We observed increased periarteriolar (Supplemental Figures 5A, 5C and 5D) and global myocardial fibrosis (Supplemental Figure 5B) in C57Bl/6N WT mice that originated from Charles River Laboratories (C57Bl/6NCrl) compared to those originating from the NIA (C57Bl/6JN) at 2 months, although younger animals from both sources exhibited significantly less periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis than did aged mice from the NIA (young NIA versus aged NIA: periarteriolar fibrosis p<0.0001, global fibrosis p<0.0001; young CR versus aged NIA: periarteriolar fibrosis p<0.001; global fibrosis p<0.05).

4. Discussion

Our results associate decreased ST2 signaling with the progression of microvascular changes in the pressure overload state implicated in amplifying and sustaining arteriolar remodeling and myocardial periarteriolar fibrosis. Our group previously demonstrated that mice administered IL-33 have less global myocardial fibrosis in pressure overload compared to those administered vehicle [15]. The current work builds upon this finding to evaluate the role of IL-33 and ST2 in periarteriolar fibrosis and to understand the role of IL-33 and ST2 in aging. We found that young Il1rl1−/− mice have increased periarteriolar fibrosis compared to wild type mice in response to pressure overload, supporting our prior finding that IL-33/ST2 signaling limits global ventricular fibrosis [15], and extending this observation to the myocardial arteriolar system. In addition, we found that IL-33 increases with age in the heart while ST2 expression decreases with age in the heart. This imbalance in IL-33/ST2 signaling associates with the increase with age in both periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis, although our data do not definitively demonstrate causality. The present results suggest that the mechanism of these abnormalities reflects primarily reduced ST2 expression rather than altered IL-33 levels, and future work will need to specifically test the hypothesis that decreased ST2L expression leads to increased periarteriolar fibrosis with age. These findings shed light on the pathophysiological pathways for coronary arterial medial remodeling and periarteriolar fibrosis, conditions currently lacking evidence-based specific therapies and that comprise a great area of unmet medical need.

IL-33/ST2 signaling can have either pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic effects, depending on the context. For example, in the lung, full-length IL-33 can act via an ST2-independent pathway leading to inflammation, while the cleaved, mature IL-33 acts via ST2 to signal the anti-inflammatory Th2 response [31]. We previously found that Il1rl1−/− mice had increased left ventricular hypertrophy and increased global myocardial fibrosis following pressure overload produced by TAC; however, we did not previously study Il33−/− mice and did not quantify periarteriolar fibrosis in that publication [15]. Recently, Veeraveedu et al. reported that Il33−/− mice also display increased LVH and increased global myocardial fibrosis following TAC, consistent with our hypothesis that IL-33 resists cardiac fibrosis [32]. Yet other reports suggest that IL-33/ST2 can be pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic in the heart [24, 25]. For example, expression of IL-33 and total ST2 in myocardium of patients undergoing implantation of a ventricular assist device demonstrated a correlation between increased IL-33 and total ST2 levels with increased myocardial fibrosis [24]. The multifaceted nature of IL-33/ST2 is evident in multiple organs, as IL-33/ST2 can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory depending on the context and location, with IL-33/ST2 predominantly anti-inflammatory in the brain [33, 34] but predominantly pro-inflammatory in the immune system [18, 35], lungs [18-20], liver [21], skin [22], and gastrointestinal system [23]. The inflammatory response appears to operate locally in the myocardium and coronary microvascular microenvironment as SAA levels quantified as a marker of systemic inflammation did not differ significantly between groups in this study. This may explain how IL-33/ST2 can have different roles on inflammation depending on the organ system. Furthermore, whether expression of ST2 changes with age in other organs remains unclear. We did not rigorously investigate other organs in this study, but further evaluation of how IL-33/ST2 dysregulation in aging affects other organs merits further investigation.

In the heart, multiple cell types express IL-33 including endothelial cells, fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes [36, 37]. Various cell types elaborate the alarmin, IL-33, among them fibroblasts and myocytes undergoing necrosis [37], while other cell types such as endothelial cells release IL-33 in response to stimuli such as pressure overload [36]. The primary target cell for extracellular IL-33 in the heart is unclear – cultured endothelial cells had higher expression of ST2 and also secreted sST2 [37], while in mice, ST2 deletion in cardiomyocytes but not endothelial cells exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy following pressure overload [36]. In addition to its extracellular functions, IL-33 also acts as a nuclear transcriptional regulator of NF-kappa B in endothelial cells via an ST2-independent mechanism [38].

During aging, periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis increase. Simplistically, one might have expected that IL-33 also decreases with age to explain this progressive fibrosis. Yet, IL-33 surprisingly increases with age. This observation agrees with studies in other tissues such as in the brain, where IL-33 increases with age in astrocytes, and deficiency of IL-33 in the brain leads to neurodegeneration [39]. Several mechanisms may explain why periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis increase with aging despite the increase in expression of cardioprotective IL-33, which will require future work: First, although total ST2 decreases with age in the heart, circulating sST2 might increase with age, resulting in sequestration of IL-33 by the decoy receptor, preventing interaction with the transmembrane isoform, ST2L. Soluble ST2 can serve as a clinical biomarker for heart failure: elevated levels of sST2 in acute and chronic heart failure portend poor cardiovascular outcomes [40, 41]. Although we did not find significant differences in serum levels of sST2 in the aged mice by ELISA, some reports describe increased sST2 with age [42, 43]. Second, interaction of IL-33 with sST2 may have adverse effects, as has been seen in other cytokines such as IL-6. In the classic signaling pathway, IL-6 acts via its membrane-bound receptor (IL-6R) and may exert an anti-inflammatory effect [44]. However, IL-6 can form a biologically active complex with its decoy receptor, soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R), which acts via trans-signaling through glycoprotein gp130 to exert a pro-inflammatory effect [44]. Thus, maintenance of an anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic state may depend on the balance between IL-33 and ST2. Third, IL-33 could actually diminish ST2L expression in the heart. IL-33 can facilitate degradation of ST2L in mouse lung epithelial cells by inducing polyubiquitination followed by proteasomal degradation [45]. In unoperated mice at 16 months of age, we found that Il33−/− and Il1rl1−/− mice both had non-significant trends toward increased periarteriolar fibrosis compared to WT mice, suggesting that absence of either IL-33 or ST2 can lead to increased fibrosis, perhaps by different mechanisms. Understanding the pathway by which IL-33/ST2 dysregulation leads to periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis and determining causality will require further study. Testing whether these findings in aging mice apply to humans should be a goal for further research.

Approximately twice as many women have HFpEF compared to men [46], for poorly understood reasons. Men have higher levels of sST2 plasma concentrations compared to women, although no independent association was identified between sST2 and selected sex hormones (testosterone, estradiol, sex hormone binding globulin, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone) [47]. We did not observe statistically significant differences between sexes throughout this study, although this result may arise from type 2 error as our study was powered based on analysis of total number of animals. We did not find that male mice had significantly different sST2 levels from female mice, although the two mice with the highest concentrations detected in our cohort were both males (Figure 3C). In contrast, while there were no significant differences between sexes in expression of either IL-33 or ST2, there may be a non-significant trend toward increased expression of IL-33 and ST2 with aging in females (Figures 2 and 3). Future work should explore molecular mechanisms to explain sex-related differences in HFpEF and how sex influences regulation of the IL-33/ST2 system.

We observed differences in young (2-month-old) C57Bl/6N mice obtained from two different vendors: Charles River Laboratories and the NIA. C57Bl/6NCrl (CR) mice had significantly increased periarteriolar and global myocardial fibrosis compared to C57Bl/6JN (NIA) mice. Previous reports have described differences in cardiac phenotype between substrains of C57Bl/6 mice [48]. Basal blood pressure is higher in C57Bl/6J (Jackson Laboratories) mice compared with C57Bl/6NTac (Taconic Farms) mice [49]. In addition, mice of the C57Bl/6NCrl and C57Bl/6NTac substrains had significantly lower survival and systolic function with increased left ventricular dilation and fibrosis compared with C57Bl/6J mice following TAC [50]. Furthermore, C57Bl/6NH (Harlan) mice had increased myocardial fibrosis and increased left ventricular mass/body weight ratios compared to C57Bl/6J mice following chronic angiotensin II infusion [51]. Finally, C57Bl/6N (NIA) mice resist cardiac fibrosis during aging more than C57Bl/6J mice [52]. The differences we observed between these two substrains in this study emphasize the importance of using appropriate control mice for aging experiments.

In summary, we observed that IL-33 increases with age while ST2 decreases with age in the heart, and that an increase in periarteriolar fibrosis with aging accompanies these alterations. In addition, we demonstrated that ST2 loss of function exacerbates periarteriolar fibrosis in hearts subjected to pressure overload by TAC. Taken together, these results suggest that although IL-33 prevents global myocardial fibrosis in young mice subjected to pressure overload [15], dysregulation of the IL-33/ST2 balance with aging may contribute to periarteriolar fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Periarteriolar fibrosis increases with age.

Interleukin-33 (IL-33) expression increases with age in the heart.

ST2 expression decreases with age in the heart.

Mice deficient in ST2 have increased periarteriolar fibrosis with pressure overload.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Joseph Gannon for his assistance with mouse surgeries, Catherine MacGillivray and Diane Faria from the Harvard Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology Histology Core for their assistance in processing histology samples, Douglas Richardson in the Harvard Center for Biological Imaging for his assistance in optimizing image acquisition, and Nithin Tumma for his assistance with troubleshooting the Python global fibrosis code.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01AG047131 and 1R0HL119230 to R.T.L. and HL080472 to P.L.). P.L. was supported by the RRM Charitable Fund. J.C.G. was supported by the John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship (Harvard Medical School) and NIH T32 Fellowship (5T32HL007572-33). J.W. was supported by NIH T32 Fellowship (2T32HL007604). I.R. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) post-doctoral fellowship.

Abbreviations:

- CR

Charles River Laboratories

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- Il1rl1

interleukin 1 receptor-like 1

- IL-33

interleukin-33

- NIA

National Institute on Aging

- ST2

suppression of tumorigenicity

- TAC

transverse aortic constriction

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Lee is a co-founder, scientific advisor, and holds private equity in Elevian, a company that aims to develop medicines to restore regenerative capacity. Elevian provides sponsored research support to the Lee Lab.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Liu T, Song D, Dong J, Zhu P, Liu J, Liu W, Ma X, Zhao L, Ling S, Current Understanding of the Pathophysiology of Myocardial Fibrosis and Its Quantitative Assessment in Heart Failure, Front Physiol 8 (2017) 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dai Z, Aoki T, Fukumoto Y, Shimokawa H, Coronary perivascular fibrosis is associated with impairment of coronary blood flow in patients with non-ischemic heart failure, J Cardiol 60(5) (2012) 416–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rikitake Y, Oyama N, Wang C-YC, Noma K, Satoh M, Kim H-H, Liao JK, Decreased perivascular fibrosis but not cardiac hypertrophy in ROCK1+/− haploinsufficient mice, Circulation 112(19) (2005) 2959–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Takayanagi T, Forrester SJ, Kawai T, Obama T, Tsuji T, Elliott KJ, Nuti E, Rossello A, Kwok HF, Scalia R, Rizzo V, Eguchi S, Vascular ADAM17 as a Novel Therapeutic Target in Mediating Cardiovascular Hypertrophy and Perivascular Fibrosis Induced by Angiotensin II, Hypertension 68(4) (2016) 949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Giamouzis G, Schelbert EB, Butler J, Growing Evidence Linking Microvascular Dysfunction With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction, J Am Heart Assoc 5(2) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lewis GA, Schelbert EB, Williams SG, Cunnington C, Ahmed F, McDonagh TA, Miller CA, Biological Phenotypes of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction, J Am Coll Cardiol 70(17) (2017) 2186–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Paulus WJ, Tschope C, A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation, J Am Coll Cardiol 62(4) (2013) 263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kato S, Saito N, Kirigaya H, Gyotoku D, Iinuma N, Kusakawa Y, Iguchi K, Nakachi T, Fukui K, Futaki M, Iwasawa T, Kimura K, Umemura S, Impairment of Coronary Flow Reserve Evaluated by Phase Contrast Cine-Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction, J Am Heart Assoc 5(2) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vaccarino V, Khan D, Votaw J, Faber T, Veledar E, Jones DP, Goldberg J, Raggi P, Quyyumi AA, Bremner JD, Inflammation is related to coronary flow reserve detected by positron emission tomography in asymptomatic male twins, J Am Coll Cardiol 57(11) (2011) 1271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Redfield MM, Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Circulation 131(6) (2015) 550–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Girolami F, Torricelli F, Camici PG, Relevance of coronary microvascular flow impairment to long-term remodeling and systolic dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, J Am Coll Cardiol 47(5) (2006) 1043–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Susic D, Francischetti A, Frohlich ED, Prolonged L-arginine on cardiovascular mass and myocardial hemodynamics and collagen in aged spontaneously hypertensive rats and normal rats, Hypertension 33(1 Pt 2) (1999) 451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Murdoch CE, Chaubey S, Zeng L, Yu B, Ivetic A, Walker SJ, Vanhoutte D, Heymans S, Grieve DJ, Cave AC, Brewer AC, Zhang M, Shah AM, Endothelial NADPH oxidase-2 promotes interstitial cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction through proinflammatory effects and endothelial-mesenchymal transition, J Am Coll Cardiol 63(24) (2014) 2734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wu J, Montaniel KR, Saleh MA, Xiao L, Chen W, Owens GK, Humphrey JD, Majesky MW, Paik DT, Hatzopoulos AK, Madhur MS, Harrison DG, Origin of Matrix-Producing Cells That Contribute to Aortic Fibrosis in Hypertension, Hypertension 67(2) (2016) 461–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT, IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system, J Clin Invest 117(6) (2007) 1538–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Xia J, Qu Y, Yin C, Xu D, Preliminary study of beta-blocker therapy on modulation of interleukin-33/ST2 signaling during ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction, Cardiol J 24(2) (2017) 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ruisong M, Xiaorong H, Gangying H, Chunfeng Y, Changjiang Z, Xuefei L, Yuanhong L, Hong J, The Protective Role of Interleukin-33 in Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion Is Associated with Decreased HMGB1 Expression and Up-Regulation of the P38 MAPK Signaling Pathway, PLoS One 10(11) (2015) e0143064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kearley J, Buckland KF, Mathie SA, Lloyd CM, Resolution of allergic inflammation and airway hyperreactivity is dependent upon disruption of the T1/ST2-IL-33 pathway, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179(9) (2009) 772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Khaitov MR, Gaisina AR, Shilovskiy IP, Smirnov VV, Ramenskaia GV, Nikonova AA, Khaitov RM, The Role of Interleukin-33 in Pathogenesis of Bronchial Asthma. New Experimental Data, Biochemistry (Mosc) 83(1) (2018) 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wu L, Luo Z, Zheng J, Yao P, Yuan Z, Lv X, Zhao J, Wang M, IL-33 Can Promote the Process of Pulmonary Fibrosis by Inducing the Imbalance Between MMP-9 and TIMP-1, Inflammation (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tan Z, Liu Q, Jiang R, Lv L, Shoto SS, Maillet I, Quesniaux V, Tang J, Zhang W, Sun B, Ryffel B, Interleukin-33 drives hepatic fibrosis through activation of hepatic stellate cells, Cell Mol Immunol (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rankin AL, Mumm JB, Murphy E, Turner S, Yu N, McClanahan TK, Bourne PA, Pierce RH, Kastelein R, Pflanz S, IL-33 induces IL-13-dependent cutaneous fibrosis, J Immunol 184(3) (2010) 1526–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pastorelli L, Garg RR, Hoang SB, Spina L, Mattioli B, Scarpa M, Fiocchi C, Vecchi M, Pizarro TT, Epithelial-derived IL-33 and its receptor ST2 are dysregulated in ulcerative colitis and in experimental Th1/Th2 driven enteritis, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(17) (2010) 8017–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tseng CCS, Huibers MMH, van Kuik J, de Weger RA, Vink A, de Jonge N, The Interleukin-33/ST2 Pathway Is Expressed in the Failing Human Heart and Associated with Profibrotic Remodeling of the Myocardium, J Cardiovasc Transl Res 11(1) (2018) 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Demyanets S, Tentzeris I, Jarai R, Katsaros KM, Farhan S, Wonnerth A, Weiss TW, Wojta J, Speidl WS, Huber K, An increase of interleukin-33 serum levels after coronary stent implantation is associated with coronary in-stent restenosis, Cytokine 67(2) (2014) 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chen WY, Chang YJ, Su CH, Tsai TH, Chen SD, Hsing CH, Yang JL, Upregulation of Interleukin-33 in obstructive renal injury, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 473(4) (2016) 1026–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Townsend MJ, Fallon PG, Matthews DJ, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN, T1/ST2-deficient mice demonstrate the importance of T1/ST2 in developing primary T helper cell type 2 responses, J Exp Med 191(6) (2000) 1069–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].deAlmeida AC, van Oort RJ, Wehrens XHT, Transverse Aortic Constriction in Mice, Journal of Visualized Experiments : JoVE (38) (2010) 1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Braitsch CM, Kanisicak O, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE, Differential expression of embryonic epicardial progenitor markers and localization of cardiac fibrosis in adult ischemic injury and hypertensive heart disease, J Mol Cell Cardiol 65 (2013) 108–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, De Keulenaer GW, MacGillivray C, Tominaga S, Solomon SD, Rouleau JL, Lee RT, Expression and regulation of ST2, an interleukin-1 receptor family member, in cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction, Circulation 106(23) (2002) 2961–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Luzina IG, Pickering EM, Kopach P, Kang PH, Lockatell V, Todd NW, Papadimitriou JC, McKenzie AN, Atamas SP, Full-length IL-33 promotes inflammation but not Th2 response in vivo in an ST2-independent fashion, J Immunol 189(1) (2012) 403–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Veeraveedu PT, Sanada S, Okuda K, Fu HY, Matsuzaki T, Araki R, Yamato M, Yasuda K, Sakata Y, Yoshimoto T, Minamino T, Ablation of IL-33 gene exacerbate myocardial remodeling in mice with heart failure induced by mechanical stress, Biochem Pharmacol 138 (2017) 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Korhonen P, Kanninen KM, Lehtonen S, Lemarchant S, Puttonen KA, Oksanen M, Dhungana H, Loppi S, Pollari E, Wojciechowski S, Kidin I, Garcia-Berrocoso T, Giralt D, Montaner J, Koistinaho J, Malm T, Immunomodulation by interleukin-33 is protective in stroke through modulation of inflammation, Brain Behav Immun 49 (2015) 322–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang Y, Liu H, Zhang H, Ye Q, Wang J, Yang B, Mao L, Zhu W, Leak RK, Xiao B, Lu B, Chen J, Hu X, ST2/IL-33-Dependent Microglial Response Limits Acute Ischemic Brain Injury, J Neurosci 37(18) (2017) 4692–4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Saluja R, Khan M, Church MK, Maurer M, The role of IL-33 and mast cells in allergy and inflammation, Clin Transl Allergy 5 (2015) 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chen WY, Hong J, Gannon J, Kakkar R, Lee RT, Myocardial pressure overload induces systemic inflammation through endothelial cell IL-33, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(23) (2015) 7249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Demyanets S, Kaun C, Pentz R, Krychtiuk KA, Rauscher S, Pfaffenberger S, Zuckermann A, Aliabadi A, Groger M, Maurer G, Huber K, Wojta J, Components of the interleukin-33/ST2 system are differentially expressed and regulated in human cardiac cells and in cells of the cardiac vasculature, J Mol Cell Cardiol 60 (2013) 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Choi YS, Park JA, Kim J, Rho SS, Park H, Kim YM, Kwon YG, Nuclear IL-33 is a transcriptional regulator of NF-kappaB p65 and induces endothelial cell activation, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 421(2) (2012) 305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Carlock C, Wu J, Shim J, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Pitcher MR, Hicks J, Suzuki A, Iwata J, Quevedo J, Lou Y, Interleukin33 deficiency causes tau abnormality and neurodegeneration with Alzheimer-like symptoms in aged mice, Transl Psychiatry 7(7) (2017) e1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Aimo A, Vergaro G, Passino C, Ripoli A, Ky B, Miller WL, Bayes-Genis A, Anand I, Januzzi JL, Emdin M, Prognostic Value of Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity-2 in Chronic Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis, JACC Heart Fail 5(4) (2017) 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Aimo A, Vergaro G, Ripoli A, Bayes-Genis A, Pascual Figal DA, de Boer RA, Lassus J, Mebazaa A, Gayat E, Breidthardt T, Sabti Z, Mueller C, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Tang WH, Grodin JL, Zhang Y, Bettencourt P, Maisel AS, Passino C, Januzzi JL, Emdin M, Meta-Analysis of Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity-2 and Prognosis in Acute Heart Failure, JACC Heart Fail 5(4) (2017) 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Coglianese EE, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Ho JE, Ghorbani A, McCabe EL, Cheng S, Fradley MG, Kretschman D, Gao W, O'Connor G, Wang TJ, Januzzi JL, Distribution and clinical correlates of the interleukin receptor family member soluble ST2 in the Framingham Heart Study, Clin Chem 58(12) (2012) 1673–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jenkins WS, Roger VL, Jaffe AS, Weston SA, AbouEzzeddine OF, Jiang R, Manemann SM, Enriquez-Sarano M, Prognostic Value of Soluble ST2 After Myocardial Infarction: A Community Perspective, Am J Med 130(9) (2017) 1112 e9–1112 e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S, The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6, Biochim Biophys Acta 1813(5) (2011) 878–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhao J, Wei J, Mialki RK, Mallampalli DF, Chen BB, Coon T, Zou C, Mallampalli RK, Zhao Y, F-box protein FBXL19-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of the receptor for IL-33 limits pulmonary inflammation, Nat Immunol 13(7) (2012) 651–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Scantlebury DC, Borlaug BA, Why are women more likely than men to develop heart failure with preserved ejection fraction?, Curr Opin Cardiol 26(6) (2011) 562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dieplinger B, Egger M, Poelz W, Gabriel C, Haltmayer M, Mueller T, Soluble ST2 is not independently associated with androgen and estrogen status in healthy males and females, Clin Chem Lab Med 49(9) (2011) 1515–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Simon MM, Greenaway S, White JK, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Wells S, Sorg T, Wong K, Bedu E, Cartwright EJ, Dacquin R, Djebali S, Estabel J, Graw J, Ingham NJ, Jackson IJ, Lengeling A, Mandillo S, Marvel J, Meziane H, Preitner F, Puk O, Roux M, Adams DJ, Atkins S, Ayadi A, Becker L, Blake A, Brooker D, Cater H, Champy MF, Combe R, Danecek P, di Fenza A, Gates H, Gerdin AK, Golini E, Hancock JM, Hans W, Holter SM, Hough T, Jurdic P, Keane TM, Morgan H, Muller W, Neff F, Nicholson G, Pasche B, Roberson LA, Rozman J, Sanderson M, Santos L, Selloum M, Shannon C, Southwell A, Tocchini-Valentini GP, Vancollie VE, Westerberg H, Wurst W, Zi M, Yalcin B, Ramirez-Solis R, Steel KP, Mallon AM, de Angelis MH, Herault Y, Brown SD, A comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mouse strains, Genome Biol 14(7) (2013) R82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Combe R, Mudgett J, El Fertak L, Champy MF, Ayme-Dietrich E, Petit-Demouliere B, Sorg T, Herault Y, Madwed JB, Monassier L, How Does Circadian Rhythm Impact Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure in Mice? A Study in Two Close C57Bl/6 Substrains, PLoS One 11(4)(2016)e0153472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Garcia-Menendez L, Karamanlidis G, Kolwicz S, Tian R, Substrain specific response to cardiac pressure overload in C57BL/6 mice, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305(3) (2013) H397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cardin S, Scott-Boyer MP, Praktiknjo S, Jeidane S, Picard S, Reudelhuber TL, Deschepper CF, Differences in cell-type-specific responses to angiotensin II explain cardiac remodeling differences in C57BL/6 mouse substrains, Hypertension 64(5) (2014) 1040–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Trial J, Heredia CP, Taffet GE, Entman ML, Cieslik KA, Dissecting the role of myeloid and mesenchymal fibroblasts in age-dependent cardiac fibrosis, Basic Res Cardiol 112(4) (2017) 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.