Abstract

For decades, researchers have endeavored to develop a general automation system to synthesize oligosaccharides comparable to the preparation of oligonucleotides and oligopeptides by commercially available machines. Inspired by the success of automated oligosaccharide synthesis through chemical glycosylation, a fully machine-driven automated system is reported here for oligosaccharides synthesis through enzymatic glycosylation in aqueous solution. The designed full automation system is based on the use of a thermosensitive polymer and a commercially available peptide synthesizer. This study represents a proof-of-concept that the enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides can be achieved in an automated manner using a commercially available peptide synthesizer.

Keywords: Machine-driven, Automation, Thermosensitive Polymer, Peptide synthesizer, Enzymatic synthesis

An automation system is designed for oligosaccharide synthesis. The automation process is based on enzymatic glycosylation, and the use of a thermosensitive polymer and a commercially available peptide synthesizer.

Oligosaccharides, oligonucleotides, and oligopeptides comprise the three major classes of natural biopolymers.[1] Structurally defined glycans have many important biological and medical applications. They find use in glycan microarray studies,[2] clinical diagnostics,[3] enzymatic activity tests,[4] and the development of carbohydrate-based vaccines[5]. However, it is difficult to obtain suitable quantities of homogeneous oligosaccharides from nature by extraction for biological studies. Synthetic preparation by either chemical or enzymatic glycosylation is the only way to obtain amounts of homogeneous oligosaccharides sufficient for research applications. Chemical glycosylation can produce structurally defined glycans with diverse natural and unnatural structures,[6] while enzymatic glycosylation can produce both simple and complicated glycans with high regio- and stereo-specificity under mild reaction conditions.[7] Regardless, both chemical and enzymatic methods require skilled researchers to perform the operation, which is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process.

The advent of automated systems for the synthesis of oligonucleotides and oligopeptides allows non-specialists to rapidly produce these biopolymers and is responsible for greatly advancing the fields of biology and medicine.[8] Over the past few decades, researchers have put considerable efforts into developing a comparable automated synthesizer to produce oligosaccharides.[9] In 1999, Wong and co-workers developed a programmable one-pot solution-phase strategy for the synthesis of oligosaccharides.[10] In 2001, a landmark breakthrough from Seeberger and co-workers opened the machine-driven synthesis of oligosaccharides based on solid-phase synthesis and chemical glycosylation.[11] This work adopted the same concept of solid-phase synthesis which was demonstrated by Merrifield for peptide synthesis.[12] Subsequently, a large number of oligosaccharides have been successfully prepared by applying this platform.[13] In addition, many other automated approaches towards chemical glycosylation were also developed to produce oligosaccharides,[14] such as a HPLC-based automated system,[15] Yoshida’s electrolysis cell-based automated system, and a Fluorous-tag solid phase system.[16] Nevertheless, chemical glycosylations suffer from tedious protection/deprotection manipulations. By comparison, enzymatic reactions are advantageous in both efficiency and specificity.[17] Although automated enzymatic synthesis is conceptually possible, it is not as well developed. Here, we report an automated system for the preparation oligosaccharides (Scheme 1). This system is based on enzymatic glycosylation, a temperature-dependent polymer, and a commercially available peptide synthesizer to fully realize the automation process.

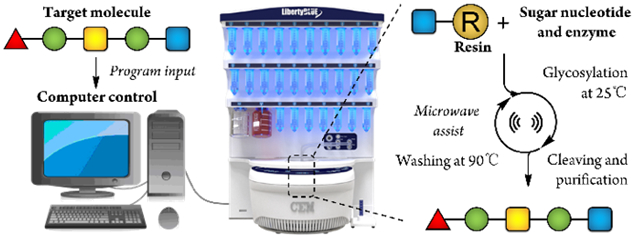

Scheme 1.

Automated enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharide.

The key steps for sugar elongation in automation process are the reaction and separation steps. Initially, we attempted Merrifield’s concept on enzymatic glycosylation. Enzymatic synthesis using solid-phase methodology was reported many years ago.[18] However, we and many other researchers found that, in general, enzymatic glycosylation on a solid-phase either does not work well or gives inadequate yields.[19] This is due to the incompatibility between enzymes and solid resin. This problem could not be solved to a satisfactory degree even after we optimized several parameters such as altering the length of linkers, utilizing different resins, and varying the particle size of the resins. At the same time, many works found that enzymatic glycosylations can be performed on solution-phase resins/polymers.[20] However, the use of solution-phase supports or polymers increases the difficulty of product purification. In 2010, Nishimura and co-workers used a globular protein-like PAMAM dendrimer for automated synthesis, which allows the product to be separated by ultrafiltration.[21] However, ultrafiltration is a difficult manipulation to be controlled by a machine. In addition, significant product loss was also observed during the purification process due to the physical properties of hollow fiber-based material.

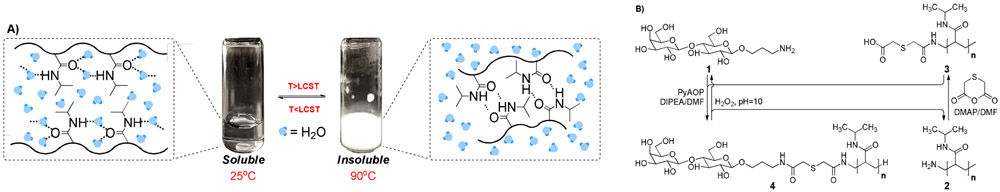

In our design, Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM),[22] a temperature-dependent polymer, is used as a support. When the environmental temperature decreases below that of the lower critical solution temperature (LCST), PNIPAM can form intermolecular hydrogen bonds with water, which allows it to be solubilized in aqueous solutions where it can be accessed by glycosyltransferases.[22] When the temperature rises, hydrogen bonds are formed intramolecularly, which causes the aggregation and precipitation of PNIPAM (Figure 1A). Consequently, a simple filtration manipulation can separate the product from other reagents such as sugar nucleotides and metal ions. The recovery yield of this polymer can reach more than 80% over ten cycles. More importantly, temperature can easily be controlled on an instrument such as a peptide synthesizer.

Figure 1.

A) thermosensitive polymer (PNIPAM). LCST, lower critical solution temperature. B) conjugation of oligosaccharide primer (lactose) with PNIPAM through a cleavable linker.

A cleavable linker is required to conjugate an oligosaccharide primer with the PNIPAM polymer. Most known cleavable linkers require strong acidic or basic conditions during cleavage. However, glycans are not stable under such conditions.[23] To avoid possible damage to the product, we used a thioether linker in this work (Figure 1B). The thioether bond is oxidized to a sulfone by hydrogen peroxide. After hydrolysis, the oligosaccharide conjugate contains a terminal NH2 in an aqueous solution. Compound 1 (lactose with aminopropyl linker) was conjugated with PNIPAM polymer in the presence of thiodiglycolic anhydride, giving product 4 in 72% yield as confirmed by NMR (Figure S2). Unreacted lactose primer can be removed through dialysis (MWCO: 1000). To test the cleavage efficiency of this linker, a standard peptide linked with lactose was treated with hydrogen peroxide (1M, pH 10). The results show that more than 80% of lactose can be released in less than 2 hours (Figure S1). In addition, we also tested the enzymatic activity of many glycotransferases with both 1 and 4. We found no significant difference between 1 and 4, indicating that enzymatic glycosylation holds almost comparable activity on the acceptor whether in solution or on soluble polymer.

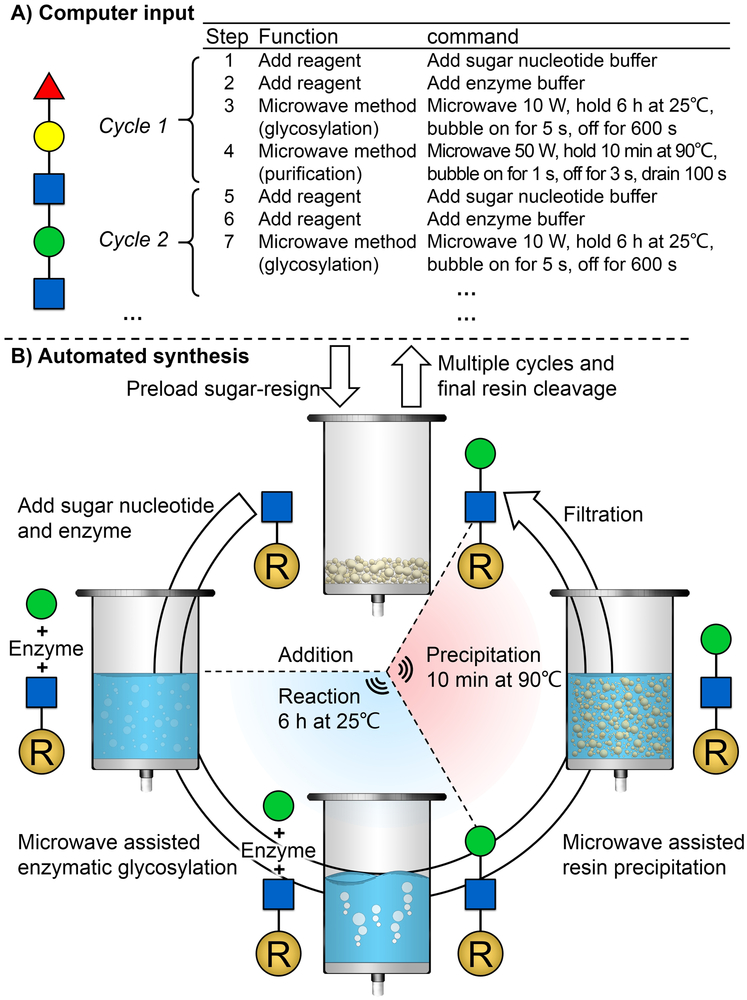

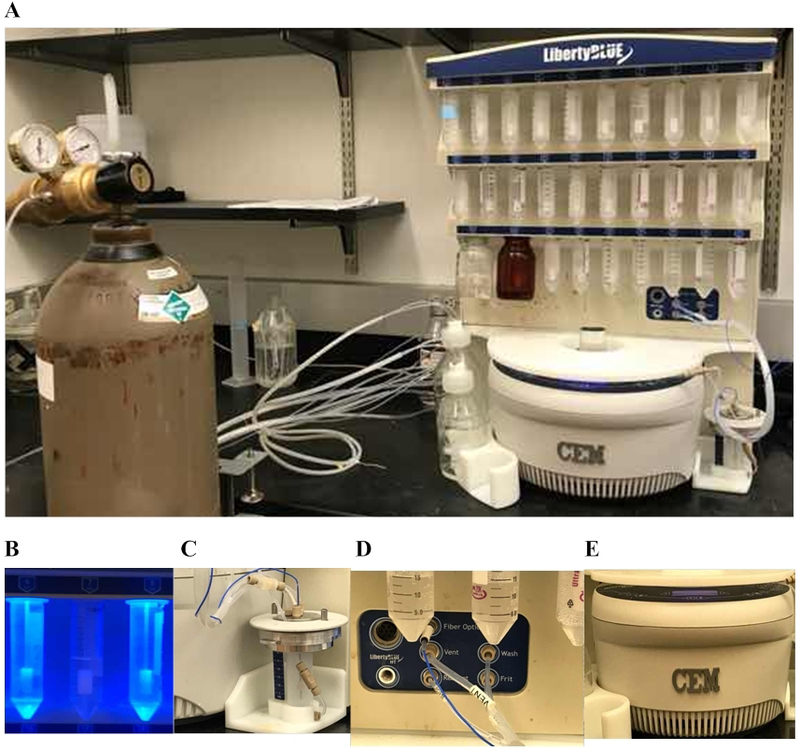

Finally, a CEM Liberty Blue peptide synthesizer was chosen to perform the designed automation process as its functional units fit our strategy well. It has a reaction vessel connected with a filter and a temperature-control system, which is controlled by a computer. The enzymes, nucleotide sugars, and reaction buffers can be stored in the preexisting tubes where amino acids would normally be stored during peptide synthesis. Reagents are automatically injected into the reaction vessel through a tubing system. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A) the peptide synthesizer (CEM Liberty Blue) used for automation synthesis in this work. B) pre-existing tubes used for enzyme and glycosylation donor storage; C) reaction vessel for enzymatic glycosylation; D) tubing system used for automation injection; E) microwave system for temperature control.

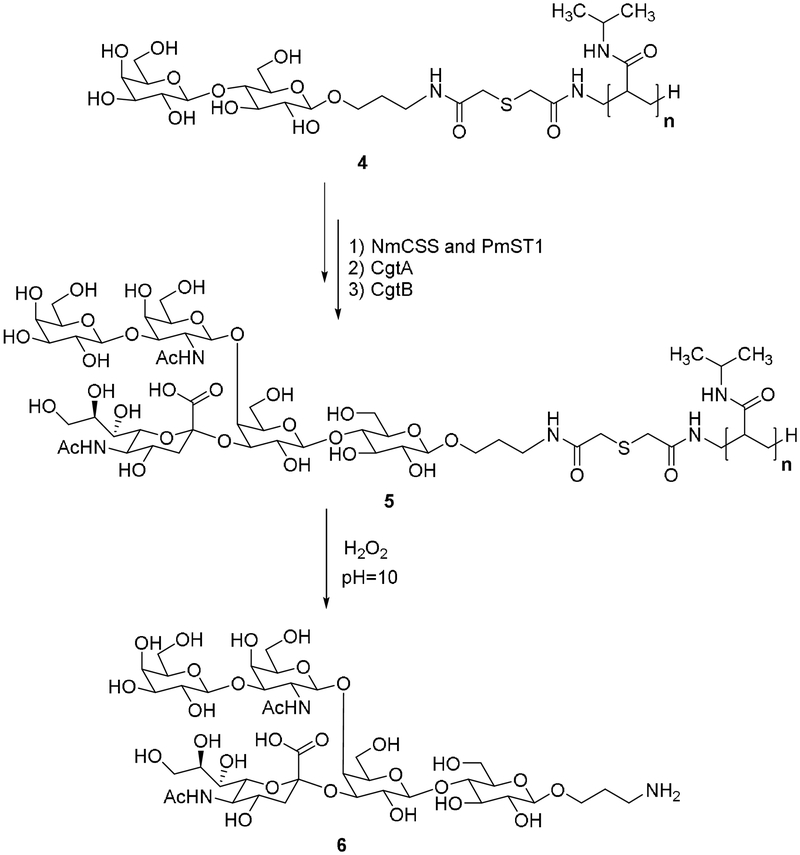

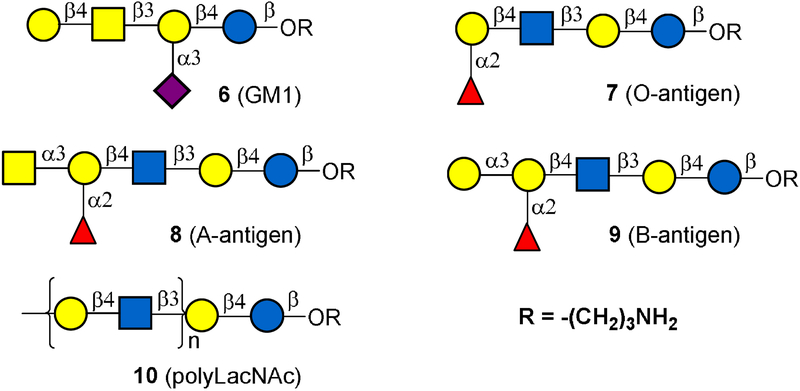

We chose compound 6 (oligosaccharides GM1) as a target to test our system (Figure 3). Ganglioside GM1 is a glycan epitope located on the cell surface and plays important roles in many biological processes such as virus-cell interactions.[24] The enzymatic synthesis of GM1 from lactose involves three glycosylation steps.[24] The enzymes used are Pasteurella multocida α2,3-sialyltransferase (PmsT1), Campylobacter jejuni β1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (CgtA) and Campylobacter jejuni β1,3-galactosyltransferase CgtB.[24] The standardized procedure contains three processes (Figure 4B): automated synthesis, product release, and product purification. In order to adapt the CEM peptide synthesizer for this purpose, several optimization procedures were required. The program protocol was first optimized for enzymatic reactions (Figure 4A). The synthetic glycosylation materials including the NmCSS (CMP-sialic acid synthetase from Neisseria meningitis), PmsT1, CgtA, CgtB, CTP, Neu5Ac, UDP-GalNAc, UDP-Gal, and reaction buffer were stored in the preexisting tubes. Compound 4, prepared as described above, was used as the glycosylation primer. To the reaction vessel of the CEM Liberty Blue, 330 mg (50 umol) of conjugated polymer (4) was loaded. The automated synthetic process was then started by automatically injecting NmCSS, PmST1, CTP (3 equiv), Neu5Ac (3 equiv), and reaction buffer (10 mL, pH 8.0). The reaction time and the amount of enzyme usage were calculated based on enzyme kinetic parameters. Once the first reaction finished (3 hours), the reaction solution temperature was increased to 90 ℃ to precipitate the glycosylation product. Unreacted materials and by-products were removed by filtration. The precipitate was washed and then CgtA, UDP-GalNAc (2 equiv), and reaction buffer (10 mL, pH 8.0) were injected into the reaction vessel to initiate the second glycosylation step. Once this reaction finished (6 hours), the glycosylation product was precipitated out and washed as described above. CgtB, UDP-Gal (2 equiv), and reaction buffer (10 mL, pH 8.0) were injected to initiate the third glycosylation step. Once this step finished (6 hours), the product was precipitated and washed. The automation process was stopped here, and the precipitate was taken out and dissolved in water. The target oligosaccharide GM1 was released by the treatment of the polymer with hydrogen peroxide (1 M, pH 10). After HPLC purification, 20 mg of GM1 oligosaccharide was obtained in 38% yield from compound 4. The product was confirmed by NMR and MS analysis (see supporting information).

Figure 3.

The principle of automation synthesis of GM1

Figure 4.

Automated enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides synthesis.

In a similar automated manner, oligosaccharides Blood O, A, and B were also successfully prepared (Table 1) using enzymes reported previously.[25] Oligosaccharides Blood O, A, and B were obtained in 27 to 38% yield (more than 10 mg scale, Table 1). The product yields obtained by the automated system are only slightly lower than the yields in in vitro synthesis. Nevertheless, the automated synthesis process can save reaction time and labor to a great extent. The products were confirmed by NMR and MS analysis (see supporting information). In addition to preparing these important oligosaccharide structures, we also tested our automation system by synthesizing Poly-N-acetyllactosamine (poly-LacNAc). Poly-LacNAc contains Galβ1,4GlcNAc repeating units, and has been identified as an important ligand for galectin-mediated cell adhesion to extra-cellular matrix (ECM) proteins.[26] Recently, it was also found Poly-LacNAc can serve as an age-specific ligand for rotavirus P[11] in neonates and infants.[27] The in vitro enzymatic synthesis of Poly-LacNAc involves two glycosylation reactions catalyzed by LgtA and LgtB.[28] Since LgtA prefers a substrate with a longer chain, trisaccharide GlcNAc β1,3Galβ1,4Glc with aminopropyl linker was conjugated with PNIPAM to serve as a primer. In a similar program and automated manner as mentioned above, 18 reaction cycles (each glycosylation reaction step was performed two times to get high conversion) were performed in seven days to produce Poly-LacNAc with 12 residues in 9% yield (8 mg). Although more glycosylation reaction steps can be performed to produce longer chain, purification is unsuccessful as the product has poor solubility in water when the sugar chain has more than 12 monosaccharide residues.

Table 1.

Oligosaccharides that prepared by automation system

| Product | Enzymes | E/Ua (mg) | Yield (%) |

Time (hours) |

Product (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | PmsT1, CgtA, CgtB | 1.6 2.1 1.8 |

38 | 27 | 20 |

| 7 | LgtB, FucT | 1.0 2.5 |

35 | 24 | 13 |

| 8 | LgtB, FucT, BgtA | 1.0 2.5 1.9 |

29 | 36 | 14 |

| 9 | LgtB, FucT, GTB | 1.0 2.5 1.8 |

27 | 36 | 13 |

| 10 | LgtA, LgtB | 1.7 1.0 |

9 | 168 | 8 |

enzyme usage

In summary, a fully machine-driven system based on enzymatic glycosylation has been developed for the automated synthesis of oligosaccharides. Several important oligosaccharides (GM1, Blood O, A, and B antigens, and Poly-LacNAc) were selected and successfully prepared in an automated manner. The use of a temperature-dependent polymer, which is soluble in water at room temperature and insoluble at elevated temperatures, overcomes limitations of solid-phase enzymatic synthesis. It allows for both aqueous-phase reactions and solid product separation.

This study represents a proof-of-concept that enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides can be achieved in an automated manner using a commercially available peptide synthesizer. This work will enable the development of an improved instrument for automated oligosaccharide synthesis in the future. Such improvements should include more storage tubes for enzymes and glycosylation donors, a temperature control system for enzyme storage, a detection system for monitoring reaction processes, more reaction vessels to perform multi-oligosaccharide syntheses simultaneously, and a larger reaction vessel to perform large-scale reactions. Moreover, a database on enzymatic reaction kinetics of glycosyltransferase enzymes should also be developed and built into the control program in future studies, which will help to improve the automation process by optimizing reaction time and enzyme usage.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

Oligosaccharides that used to test automation system in this work.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (U01GM116263) for financial support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- [1].Wen L, Edmunds G, Gibbons C, Zhang J, Gadi MR, Zhu H, Fang J, Liu X, Kong Y, Wang PG, Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 8151–8187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rillahan CD, Paulson JC, Annu. Rev. Biochem 2011, 80, 797–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Inagaki Y, Song P, Tang W, Kokudo N, Drug Discov. Ther 2015, 9, 129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Wen L, Gadi MR, Zheng Y, Gibbons C, Kondengaden SM, Zhang J, Wang PG, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7659–7666; [Google Scholar]; b) Wen L, Liu D, Zheng Y, Huang K, Cao X, Song J, Wang PG, ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4, 451–457; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wen L, Zheng Y, Jiang K, Zhang M, Kondengaden SM, Li S, Huang K, Li J, Song J, Wang PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11473–11476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Huang YL, Wu CY, Expert Rev. Vaccines 2010, 9, 1257–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Das R, Mukhopadhyay B, ChemistryOpen 2016, 5, 401–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Muthana S, Cao HZ, Chen X, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2009, 13, 573–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sears P, Wong CH, Science 2001, 291, 2344–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Hsu CH, Hung SC, Wu CY, Wong CH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11872–11923; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Seeberger PH, Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1450–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang ZY, Ollmann IR, Ye XS, Wischnat R, Baasov T, Wong CH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 734–753. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Plante OJ, Palmacci ER, Seeberger PH, Science 2001, 291, 1523–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Merrifield RB, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1963, 85, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Calin O, Eller S, Seeberger PH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 5862–5865; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hahm HS, Hurevich M, Seeberger PH, Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 12482; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Eller S, Collot M, Yin J, Hahm HS, Seeberger PH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 5858–5861; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kröck L, Esposito D, Castagner B, Wang C-C, Bindschädler P, Seeberger PH, Chem. Sci 2012, 3, 1617–1622; [Google Scholar]; e) Seeberger PH, Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37, 19–28; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Panza M, Pistorio SG, Stine KJ, Demchenko AV, Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 8105–8150; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Hsu CH, Hung SC, Wu CY, Wong CH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11872–11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nokami T, Hayashi R, Saigusa Y, Shimizu A, Liu CY, Mong KK, Yoshida J, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4520–4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pistorio aS. G., Nigudkar SS, Stine KJ, Demchenko AV, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 8796–8805; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ganesh NV, Fujikawa K, Tan YH, Stine KJ, Demchenko AV, Org. Lett 2012, 14, 3036–3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Ko KS, Park G, Yu Y, Pohl NL, Org. Lett 2008, 10, 5381–5384; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roychoudhury R, Pohl NL, Org. Lett 2014, 16, 1156–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Hanson S, Best M, Bryan MC, Wong CH, Trends Biochem. Sci 2004, 29, 656–663; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen X, Kowal P, Wang PG, Curr. Opin. Drug. Discov. Devel 2000, 3, 756–763; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Muthana S, Cao H, Chen X, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2009, 13, 573–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schuster M, Wang P, Paulson JC, Wong C-H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 1135–1136. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhu H, Wu Z, Gadi MR, Wang S, Guo Y, Edmunds G, Guan W, Fang J, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 27, 4285–4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wen L, Edmunds G, Gibbons C, Zhang J, Gadi MR, Zhu H, Fang J, Liu X, Kong Y, Wang PG, Chem. Rev 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Matsushita T, Nagashima I, Fumoto M, Ohta T, Yamada K, Shimizu H, Hinou H, Naruchi K, Ito T, Kondo H, Nishimura S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 16651–16656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Huang XF, Witte KL, Bergbreiter DE, Wong CH, Adv. Synth. Catal 2001, 343, 675–681. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Halcomb RL, Huang H, Wong C-H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 11315–11322; [Google Scholar]; b) Meldal M, Auzanneau FI, Hindsgaul O, Palcic MM, J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm 1994, 1849–1850; [Google Scholar]; c) Cai C, Dickinson DM, Li L, Masuko S, Suflita M, Schultz V, Nelson SD, Bhaskar U, Liu J, Linhardt RJ, Org. Lett 2014, 16, 2240–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yu H, Li Y, Zeng J, Thon V, Nguyen DM, Ly T, Kuang HY, Ngo A, Chen X, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 10809–10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ye JF, Liu XW, Peng P, Yi W, Chen X, Wang FS, Cao HZ, Acs Catal. 2016, 6, 8140–8144. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sauerzapfe B, Krenek K, Schmiedel J, Wakarchuk WW, Pelantova H, Kren V, Elling L, Glycoconj. J. 2009, 26, 141–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Y, Huang PW, Jiang BM, Tan M, Morrow AL, Jiang X, Plos One 2013, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Lau K, Thon V, Yu H, Ding L, Chen Y, Muthana MM, Wong D, Huang R, Chen X, Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 6066–6068; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Peng W, Pranskevich J, Nycholat C, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk W, Paulson JC, Razi N, Glycobiology 2012, 22, 1453–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.