Abstract

Our aim was to evaluate whether quality of life (QOL) scores at diagnosis predict survival among patients with aggressive lymphoma. Newly diagnosed lymphoma patients were prospectively enrolled within 9 months of diagnosis in the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic SPORE and systematically followed for event-free and overall survival (OS). QOL was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment-General (FACT-G), which measures 4 domains: physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being (WB); a single item Linear Analogue Self-Assessment (LASA) measuring overall QOL; and a spiritual WB LASA. From 9/2002–12/2009, 701 patients with aggressive lymphoma who completed baseline QOL questionnaires were enrolled. At a median follow-up of 71 months (range 6–128), 316 patients (45%) had an event and 228 patients (33%) died. All baseline QOL measures but emotional WB were significantly associated with OS (all p<0.04); of which all but LASA spiritual remained significant after adjusting for IPI and NHL subtype. The strongest associations were with total FACT-G (adjusted HR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94, p=0.00062) and functional WB (adjusted HR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.83–0.93, p<.0001). QOL LASA was associated with OS (adjusted HR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97, p=0.0041). Patients with clinically deficient QOL (overall QOL ≤50) had a median OS of 92 months compared to 121 months for patients with QOL >50 (p=0.0004). In this large sample of patients with aggressive lymphoma, we found that baseline QOL is independently predictive of OS. QOL should be assessed as a prognostic factor in patients with aggressive lymphoma.

Keywords: quality of life, lymphoma, prognosis, survival, surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Aggressive lymphomas are treatable and potentially curable malignancies. Currently, the most widely used predictive model for survival in aggressive lymphoma is the International Prognostic Index [1] which includes age, stage, lactate dehydrogenase level, number of extranodal sites, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS). Performance status is a rating of patient function, assessed by the physician, and is meant to reflect the how the cancer affects the daily living activities [2]. However, current prognostic models do not fully explain the significant variation in patient outcome with 30% of patients experiencing refractory or relapsed disease, and therefore, new prognostic factors are necessary.

Patient-reported outcomes, including quality of life (QOL), are recognized as important measures of the effect of cancer and its treatment on patients. QOL, a broad concept that includes physical, emotional, social, and functional domains, may also be a prognostic marker. In fact, QOL at cancer diagnosis has been shown to be prognostic for survival in clinical trial patients with a variety of tumor types [3], including a meta-analysis of greater than 10,000 patients [4]. This has been shown in other solid tumor patients [5–7] and multiple myeloma [8, 9]. However, QOL as a prognostic factor has not been studied extensively in patients with other hematological malignancies, including lymphomas. In the Nordic Lymphoma Group study of 68 patients with aggressive lymphoma, baseline patient-reported QOL was highly predictive of overall survival (OS) with a relative risk of 7.9 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2–52.4], which was independently associated with OS after adjustment for the international prognostic index [10]. However, the conclusions were limited by the small sample size and difficulty with handling of questionnaires. Jung and colleagues reported that pretreatment QOL was prognostic for OS in a cohort of 263 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, although the effect size was small [hazard ratio (HR)=0.96, 95% CI: 0.96–1.00 for global health scale; HR=0.96, 95% CI: 0.95–1.00 for function scale; and HR=1.05, 95% CI: 0.94–1.00 for symptom/sign scale] [11]. Therefore, the current study was designed to examine whether self-reported baseline QOL, treated in the modern era and adjusted for prognostic variables, is associated with survival in a large cohort of patients with aggressive lymphomas.

Patients and Methods

Sample

Since September 2002, all newly diagnosed patients with histologically-confirmed non-Hodgkin lymphoma seen at the Mayo Clinic and the University of Iowa have been prospectively offered enrollment into the Molecular Epidemiology Resource of the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence (CA97274) [12–14]. Eligibility criteria include <9 months from diagnosis and age 18 years or older; exclusion criteria include HIV-positive, non-US residency, and inability to participate in an interview conducted in the English language. All pathology was reviewed by a lymphoma hematopathologist [15]. All patients provided informed consent. For purposes of this analysis, we considered “aggressive lymphoma” to consist of the following histological subtypes: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (including transformed, primary CNS, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, and de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), mantle cell lymphoma, grade 3A and 3B follicular lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma excluding mycosis fungoides and cutaneous types, and other (Burkitt lymphoma, highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma NOS, etc.).

Measures

QOL was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General scale (FACT-G, Version 4) [16] a general QOL assessment for cancer patients which measures four QOL domains: physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being (WB). Patients rate 27 items from 0–4, “4” reflecting items that “very much” apply to them in the past 7 days. The four subscales are added to calculate an overall QOL score, and a lower score indicates a poorer QOL. Possible FACT-G scores are: 0–24 for emotional WB, 0–28 for other WB subscales, and 0–108 for total WB. Previous evaluations of the FACT-G have reported strong reliability and validity, including in lymphoma patients [17]. In addition, patients rated their overall and spiritual QOL via a Linear Analogue Scale (LASA), a single item measurement that has been studied and validated in cancer patients [18, 19]. Patients who did not complete ≥ 80% of QOL questions were excluded. Because patients could be enrolled at any point within the first 9 months from diagnosis, the timing of initial QOL assessment was variable with respect to the start of lymphoma treatment. Patients were placed in two groups for analysis: QOL assessment prior to initiation of therapy and after the initiation of therapy.

This study was performed after approval by the institutional review boards and was in adherence with the ethical standards of the institutions. Clinical, laboratory, and treatment data were abstracted from medical records using a standard protocol. Patients were systematically contacted for outcomes including re-treatment, event-free and overall survival (EFS and OS, respectively). All treatment, progression, and death events were validated via review of medical records.

Data Analysis

Baseline QOL was modeled as a function of time-from-diagnosis (days) and treatment status (pre-treatment vs. after treatment initiation) using smoothing splines with interaction to assess the differences in QOL based on timing since diagnosis, as well as to determine the mean (predicted) QOL for patients given the timing of their QOL assessment. For ease of comparison, all QOL measures were transformed to a 0–100 scale. Consistent with validated cut-offs, clinically deficient QOL was defined as overall QOL LASA of ≤50 on the transformed scale [20]. Event free survival (EFS) was defined as time from diagnosis to the first event, where events were defined as disease progression, re-treatment of lymphoma after initial therapy, or death due to any cause. Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from disease diagnosis to death due to any cause. Patients without a death or event were censored at time of last known follow-up. Cox proportional hazards models using left truncation at time of QOL assessment were used to evaluate the association between QOL and outcome. To account for differences in QOL based on the timing of QOL assessment from diagnosis, QOL was modeled using a patient’s observed QOL minus the predicted QOL based on their treatment status and time since diagnosis (residual QOL). QOL measures were transformed to a 10-point scale for Cox models so the hazard ratio represents a per-10% increase in total QOL. Cox models were adjusted for the IPI and histological subtype. Sensitivity analyses were performed for Cox models using raw QOL, both in all patients and only in patients with pre-treatment QOL assessment within 2 months of diagnosis. Prognostic models were assessed using c-statistics and Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Bootstrapping was used to assess significance of differences in AIC and c-statistics between LASA and FACT-G prognostic models. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Rv3.0.1.

Results

Patient Characteristics

From September 2002 to December 2009, 701 patients with aggressive lymphoma who completed baseline QOL questionnaire were enrolled on the MER. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At a median follow-up of 71 months (range 6–128), 316 patients (45%) had an event and 228 patients (33%) died. QOL assessment was prior to therapy in 330 patients (47%) and after the initiation of therapy in 371 (53%). Patient characteristics were similar between pre-therapy and post-therapy initiation groups with the exception of higher performance status (57% PS=0 vs 43% PS=0, p<0.001) and higher LDH in the pre-therapy initiation group (59% elevated vs 40% elevated, p<0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Prior to Initiation of Therapy N=330 (47%) | After Initiation of Therapy N=371 (53%) | Total N=701 (100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age - median (range) | 63 (19–88) | 61 (18–92) | 62 (18–92) |

| Male | 191 (58) | 212 (57) | 403 (58) |

| Age >60 | 191 (58) | 188 (51) | 379( 54) |

| Ann Arbor Stage III-IV | 241 (74) | 256 (69) | 497 (72) |

| LDH >Normal | 126 (40) | 180 (59) | 306 (49) |

| ECOG PS ≥2 | 26 (8) | 88 (24) | 114 (16) |

| Extranodal Sites >1 | 64 (19) | 74 (20) | 138 (20) |

| B symptoms | 51 (16) | 105 (29) | 156 (22) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 170 (81) | 170 (78) | 340 (79) |

| Single | 39 (19) | 49 (22) | 88 (21) |

| Unknown/missing | 121 | 152 | 273 |

| IPI | |||

| Low (0–1) | 112 (34) | 114 (31) | 226 (32) |

| Low-intermediate (2) | 93 (28) | 101 (27) | 194 (28) |

| High-intermediate (3) | 79 (24) | 91 (24) | 170 (24) |

| High (4–5) | 46 (14) | 65 (18) | 111 (16) |

| Subtype | |||

| DiffuselargeB-celllymphoma/ Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma | 175 (53) | 249 (67) | 424 (60) |

| Follicular lymphoma–grade III | 47 (14) | 28 (8) | 75 (11) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 63 (19) | 37 (10) | 100 (14) |

| High grade lymphoma | 4 (1.2) | 5 (1.4) | 9 (1.3) |

| T-cell lymphoma | 41 (12) | 52 (14) | 93 (13) |

| Anthracycline-based treatment | 263 (80) | 324 (87) | 587 (84) |

QOL Summary

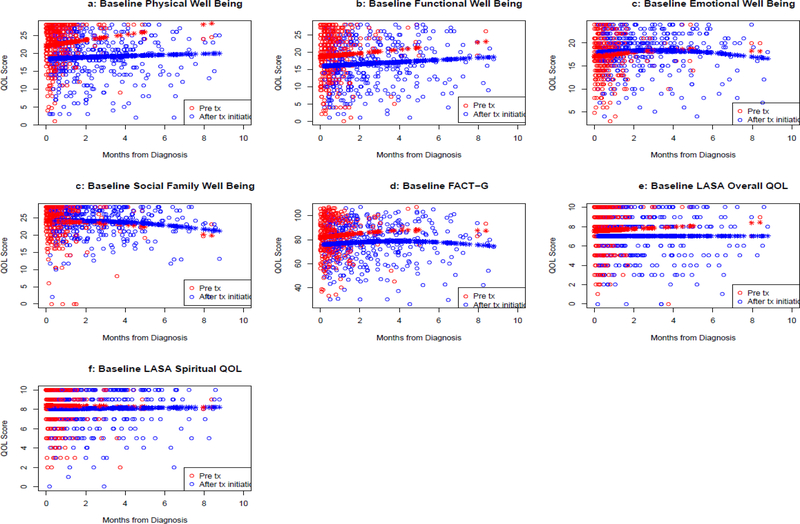

The median overall raw FACT-G total score was 83 (range 70–93), and the median (range) scores on the functional WB, physical WB, emotional WB, and social/family WB were 18 (13–23), 22 (17–26), 18 (16–21), and 25 (22–27), respectively. Twenty-three percent had clinically significant overall QOL deficits on the LASA (score ≤50 on 0–100 scale). When comparing QOL scores between those who were on active therapy versus those who were not yet treated, physical WB (p=0.0044), functional WB (p<.0001), total FACT-G (p<.0001), and QOL LASA (p=0.031) were lower in those on active treatment (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Plot of QOL on raw scale by time of QOL assessment from initial diagnosis date. Color indicates if the QOL was assessed before or after initiation of treatment. Open circles are observed values. Closed circles are fitted values from model containing variables for time from diagnosis and treatment status.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Raw QOL Scores for all Patients and Comparison of Those Who Completed QOL Questionnaires Prior to Initiation of Therapy Versus Those Who Completed QOL Questionnaires after Initiation of Therapy

| All Patients | Prior to Initiation of Therapy | After Initiation of Therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median QOL (IQR) | Median QOL (IQR) | Median QOL (IQR) | P | |

| Functional WB | 18 (13–23) | 20 (15–24) | 17 (12–22) | 0.00014 |

| Physical WB | 22 (17–26) | 24 (20–27) | 20 (15–24) | <.0001 |

| Emotional WB | 18 (16–21) | 18 (15–20) | 19 (16–21) | 0.086 |

| Social/family WB | 25 (22–27) | 25 (22–28) | 25 (22–27) | 0.93 |

| Overall FACT-G | 83 (70–93) | 85 (73–96) | 80 (68–91) | 0.0013 |

| LASA Overall | 8 (6–9) | 8 (7–9) | 7 (5–9) | 0.031 |

| LASA Spiritual | 9 (7–10) | 9 (7–10) | 8 (7–10) | 0.13 |

P-value comparing QOL by treatment status generated from generalized additive model including treatment status and time from diagnosis

QOL and Outcome

Except for the emotional WB, all QOL measures were associated with either event free (all p<0.08) or overall survival (all p<0.05); these associations remained similar after adjusting for international prognostic index and lymphoma subtype (Table 3). Associations were stronger for OS than EFS. For OS, the strongest associations were with total FACT-G (adjusted HR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94, p=0.0006) and functional WB (adjusted HR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.83–0.93, p=1.08×10−5) (Table 3). For EFS, the strongest associations were with total FACT-G (adjusted HR=0.91, 95% CI: 0.85–0.98, p=0.017) and functional WB (adjusted HR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.88–0.97, p=0.0015) (Table 3). The single-item QOL LASA was also associated with EFS (adjusted HR=0.96, 95% CI: 0.92–1.01, p=0.16 and unadjusted HR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.88–0.96, p=0.0005) and OS (adjusted HR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97, p=0.0041 and unadjusted HR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.82–0.92, p<.0001).

TABLE 3.

Summary of Cox Models for Residual QOL

| EFS | OS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Functional Well Being | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.90 | 0.86–0.95 | 2.46 ×10−5 | 0.85 | 0.81–0.90 | <.0001 |

| Adjusted* | 0.92 | 0.88–0.97 | 0.0015 | 0.88 | 0.83–0.93 | <.0001 |

| Physical Well Being | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.93 | 0.88–0.98 | 0.0044 | 0.89 | 0.83–0.94 | <.0001 |

| Adjusted* | 0.95 | 0.90–1.00 | 0.070 | 0.92 | 0.86–0.98 | 0.0061 |

| Emotional Well Being | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.34 | 0.95 | 0.88–1.02 | 0.18 |

| Adjusted* | 0.99 | 0.93–1.06 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.92–1.06 | 0.69 |

| Social / Family Well Being | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 | 0.88–1.00 | 0.071 | 0.93 | 0.86–0.99 | 0.038 |

| Adjusted* | 0.95 | 0.88–1.01 | 0.099 | 0.92 | 0.86–0.99 | 0.040 |

| Total FACT-G Well Being | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.88 | 0.82–0.94 | 0.00050 | 0.81 | 0.75–0.88 | <.0001 |

| Adjusted* | 0.91 | 0.85–0.98 | 0.017 | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | <.0001 |

| #Deficient - unadjusted | 1.76 | 1.16–2.66 | 0.0074 | 2.25 | 1.44–3.53 | <.0001 |

| #Deficient - adjusted | 1.43 | 0.94–2.16 | 0.096 | 1.65 | 1.05–2.60 | 0.030 |

| LASA Overall | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.92 | 0.88–0.96 | 0.00053 | 0.87 | 0.82–0.92 | <.00017 |

| Adjusted* | 0.96 | 0.92–1.01 | 0.16 | 0.92 | 0.87–0.97 | 0.0041 |

| #Deficient - unadjusted | 1.35 | 1.05–1.74 | 0.022 | 1.66 | 1.25–2.21 | <.00010.11 |

| #Deficient - adjusted | 1.05 | 0.81–1.36 | 0.69 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.70 | |

| LASA Spiritual | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.96 | 0.90–1.02 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.87–0.99 | 0.026 |

| Adjusted* | 0.99 | 0.93–1.05 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.90–1.03 | 0.25 |

Modeling residual QOL which represents the increase in QOL after accounting for the timing of QOL assessment and whether QOL was measured before or after treatment initiation. Positive residual QOL signifies a better than average QOL. Hazard ratio for residual QOL is per 10 point change in QOL, with QOL on a 0–100 scale. HR < 1 indicates association of better QOL with improved outcome.

Adjusted for IPI (0 vs 1 vs 2 vs 3 vs 4 vs 5) and subtype (DLBCL vs. T-cell vs. MCL vs. FL)

Deficient defined as ≤50 on 100 point scale

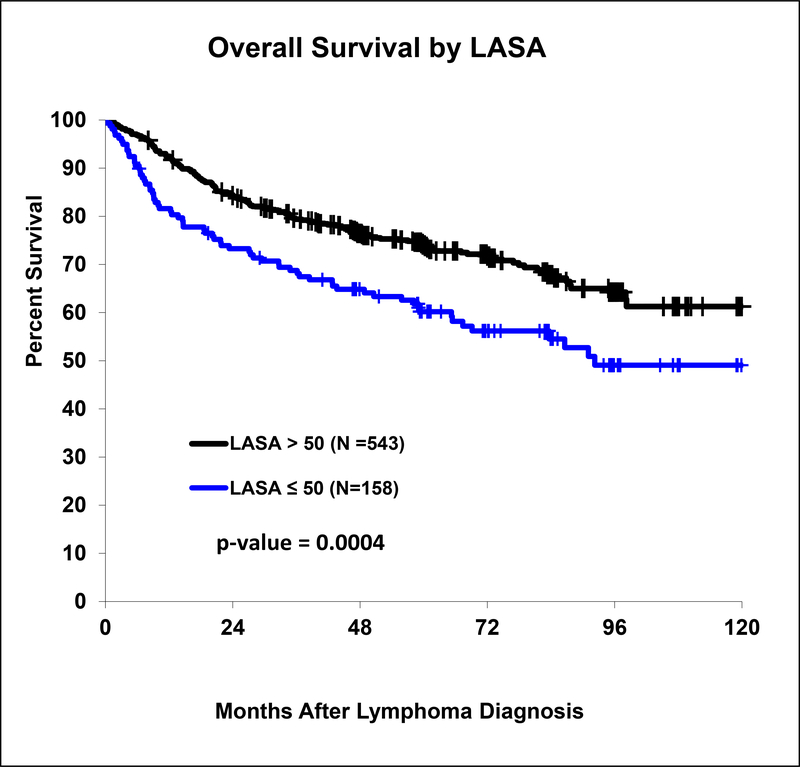

When comparing those with a baseline clinically deficient overall QOL to the others (LASA≤50 vs >50), the median overall survival was 92 months versus 121 months (p=0.0004) (Figure 2). Deficient QOL was associated with inferior unadjusted EFS (HR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.05–1.74, p=0.022) and OS (HR=1.66, 95% CI: 1.25–2.21, p=0.0005). After adjusting for the international prognostic index, results attenuated (adjusted EFS HR=1.05, 95% CI: 0.81–1.36, p=0.69); (adjusted OS HR=1.27, 95% CI: 0.95–1.70, p=0.11). In a sensitivity analysis, raw QOL (without accounting for timing of QOL and treatment status) was modeled for EFS and OS in the subset of patients with QOL assessed within 2 months of diagnosis and prior to treatment; hazard ratios were consistent with the time and treatment status-adjusted QOL hazard ratios in all patients (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Overall survival by LASA in those with clinically deficient LASA compared to those with sufficient LASA.

Comparison of FACT-G, LASA, and Performance Status

We analyzed QOL and performance status to determine if self-reported QOL provided different prognostic information compared to physician-reported performance status. For this analysis, we limited the sample to patients who completed QOL assessment within 2 months of initiation of therapy and had performance status reported at baseline (n=308). Performance status and QOL are correlated measures (Supplementary Figure 1). In Cox unadjusted univariate models, performance status=1 (HR=1.59, 95% CI: 1.01–2.50, p=0.047), performance status=2 (HR=5.07, 95% CI: 2.88–8.92, p=1.75×10−5), total FACT-G (HR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.71–0.94, p=0.004) and LASA QOL (HR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.80–0.96, p=0.003) were all associated with OS. When comparing the LASA with the FACT-G, the prognostic value of the two QOL instruments was similar as assessed via AIC and C-index (Table 4). Including both performance status and QOL (either FACT-G or LASA) in a Cox model yielded a higher C-index indicating an improvement in concordance (Table 4); however the AIC suggests that the overall information in the QOL + PS model was similar to the model of PS alone.

TABLE 4.

Summary of Cox Unadjusted Models for PS and QOL for Cohort with QOL Assessment within 2 Months from Diagnosis (N=308)

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P | C Index | AIC | −2 Log L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG Performance Status | ||||||

| OS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.59 | 1.01–2.50 | 0.047 | 0.614 | 977.19 | 973.19 |

| PS 2+ | 5.07 | 2.88–8.92 | 1.75e–08 | |||

| EFS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.33 | 0.90–1.96 | 0.147 | 0.571 | 1346.61 | 1342.61 |

| PS 2+ | 3.05 | 1.81–5.14 | 2.97e–05 | |||

| Total FACT-G Well Being | ||||||

| OS | 0.82 | 0.71–0.94 | 0.004 | 0.594 | 992.25 | 990.25 |

| EFS | 0.89 | 0.79–1.01 | 0.070 | 0.551 | 1355.85 | 1353.85 |

| LASA Overall | ||||||

| OS | 0.87 | 0.80–0.96 | 0.003 | 0.589 | 991.93 | 989.93 |

| EFS | 0.95 | 0.88–1.03 | 0.254 | 0.540 | 1357.76 | 1355.76 |

| PS + Total FACT-G | ||||||

| OS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.52 | 0.94–2.44 | 0.085 | 0.640 | 978.73 | 972.73 |

| PS 2+ | 4.54 | 2.36–8.72 | 5.55e–06 | |||

| Total FACT-G | 0.95 | 0.82–1.10 | 0.499 | |||

| EFS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.32 | 0.88–1.98 | 0.183 | 0.587 | 1348.58 | 1342.58 |

| PS 2+ | 2.98 | 1.65–5.38 | 3.05e–04 | |||

| Total FACT-G | 0.99 | 0.86–1.13 | 0.869 | |||

| PS + Overall LASA | ||||||

| OS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.52 | 0.95–2.41 | 0.078 | 0.631 | 978.09 | 972.09 |

| PS 2+ | 4.35 | 2.31–8.20 | 5.30e–06 | |||

| Overall LASA | 0.95 | 0.86–1.05 | 0.291 | |||

| EFS | ||||||

| PS 1 | 1.34 | 0.91–1.99 | 0.140 | 0.565 | 1348.54 | 1342.54 |

| PS 2+ | 3.14 | 1.77–5.57 | 9.02e–05 | |||

| Overall LASA | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 | 0.795 |

Comparison of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma and Other Aggressive Histologies

As a sensitivity analysis, we examined QOL in the subset of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who were treated with anthracycline-based immunochemotherapy (Supplementary Table 2). There was some modest attenuation in the effect sizes, but overall the results in this subset were consistent with the cohort as a whole.

Discussion

In this large sample of patients with aggressive lymphoma, baseline QOL is predictive of OS and EFS in patients with aggressive lymphoma, even after adjustment for known factors related to survival (international prognostic index and lymphoma subtype). This provides evidence that patient-reported outcomes are as important as other more objective measures, such as laboratory values and stage, and QOL should be assessed at diagnosis as a prognostic factor in patients with aggressive lymphoma. In addition, we report that functional WB, physical WB, and overall QOL is lower after initiating chemotherapy compared to prior to therapy, suggesting that therapy-related side effects significantly impact patients.

Performance status is an important prognostic factor in cancer patients, although it may not always be an accurate representation of patient function with physicians generally rating the performance status better than patients’ self-assessment [21]. Patients’ self-reported QOL provides subjective interpretation of the effect of the disease on the individual, and adds prognostic information in the models. Therefore, QOL should be used as an adjunct to performance status assessment.

These findings are of interest. QOL is a broad term and includes multiple domains. We found that functional and physical WB were lower when measured in patients on active treatment as compared to patients prior to starting therapy, possibly due to chemotherapy side effects, while emotional WB and social/family WB scores were similar. While this is a cross-sectional comparison, a longitudinal study in patients with aggressive lymphoma reported a similar decline in physical function and role function QOL domains during the time of chemotherapy as compared to pre-treatment, with improvement to above baseline levels 3 months after completion of therapy [22].

In terms of QOL as a prognostic factor, in this study, overall QOL and functional, physical, and social/family WB were predictive of survival, independent of disease characteristics. It is possible that interventions focused on symptom management and improving function during the time of chemotherapy may have an impact on patient outcomes. Integrating cancer rehabilitation and exercise programs into active cancer therapy have been reported to improve physical function and QOL in lymphoma patients, but it is not yet known if this would translate into a survival benefit [23, 24]. Temel et al randomized patients with metastatic lung cancer to early palliative care (including physical and psychosocial symptom assessment) integrated with oncological care or standard oncological care, and reported an improvement in QOL and overall survival in those who received concurrent palliative care, despite less aggressive end-of-life care [25]. Another similar study of advanced cancer patients showed improved QOL in those who received early palliative care in addition to standard oncological care, although survival data was not reported [26]. This approach has not been studied in patients with curable hematological malignancies, and it is not feasible for every cancer patient to be concurrently managed by a palliative care specialist. Future studies should focus on models of care which integrate valuable palliative care and cancer rehabilitation components into standard oncological care for patients with both curable and incurable diseases.

In addition, our findings suggest that social and family WB are important for lymphoma patients, perhaps through the mechanism of greater adherence to therapy, improved access to care, decreased distress, or other mechanisms that are not well understood such as improved immune function [27]. These findings are consistent with the observation that marital status, as a surrogate of social support, is predictive of survival in patients with a variety of malignancies [28], including lymphoma. Furthermore, psychosocial support interventions have been reported to improve survival in women with breast cancer [29, 30], and future investigations should include these types of supportive interventions across a broader range of patients.

Our findings are consistent with other investigators who have studied QOL as a prognostic factor in lymphoma patients after accounting for differences in analysis [10, 11]. Strengths of this study include the large cohort of patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma who were systematically followed for outcomes within a large epidemiology cohort, inclusion of patients with multiple histologies of “aggressive lymphoma”, treated with a variety of regimens, which enhances the generalizability of these findings, and assessment of QOL with standardized tools. This data adds to the literature on QOL in patients with hematological malignancies, as most of the previous studies are in patients with solid tumors. Our study is limited by the fact that baseline QOL assessments were completed within 9 months of diagnosis, which included time points both pre- and post-initiation of treatment, but we accounted for this with statistical modeling and a sensitivity analysis.

The use of more extensive QOL instruments such as the FACT-G can be useful to assess QOL across domains or for research purposes. However, for the treating physician, assessing patient-reported QOL in the hematology/oncology clinic can be done quickly and efficiently. Our results suggest that deficient score from a one-question QOL LASA (“How would you rate your overall well-being over the past week?”, scale 0–10, 0=as bad as it can be, 10=as good as it can be) has prognostic significance. Further in-depth inquiry regarding patient needs, followed by supportive care interventions, can then be tailored to those patients who report clinically significant deficits (score ≤5 on a 0–10 scale).

In summary, baseline self-reported QOL is predictive of OS in patients with aggressive lymphoma. Providers caring for patients with aggressive lymphoma should assess QOL at diagnosis. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism through which QOL is related to survival and whether interventions to increase QOL will also increase survival in patients with aggressive lymphoma.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Correlation between PS groups (ps.group), FACT-G overall (fact.g), functional WB (fwb), physical WB (pwb), emotional WB (ewb), social/family WB (sfwb), LASA QOL overall (ov.lasa), and spiritual LASA (sp.lasa).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (P50 CA97274) to the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence, the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, the Henry J. Predolin Foundation, and the Arnold and Kit Palmer Benefactor Award.

References

- 1.The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace F. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, et al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, Terrell JE, Gruber SB, Duffy SA. Quality of life scores predict survival among patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2754–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer F, Fortin A, Gelinas M, et al. Health-related quality of life as a survival predictor for patients with localized head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):2970–2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sloan JA, Zhao X, Novotny PJ, et al. Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and non-small-cell lung cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1498–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strasser-Weippl K, Ludwig H. Psychosocial QOL is an independent predictor of overall survival in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2008;81(5):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WislØff F, Hjorth M. Health-related quality of life assessed before and during chemotherapy predicts for survival in multiple myeloma. BrJ Haematol. 1997;97(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerkeman M, Kaasa S, Hjermstad M, Kvaloy S, Cavallin-Stahl E. Health-related quality of life and its potential prognostic implications in patients with aggressive lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group Trial. Med Oncol. 2001;18(1):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung H, Park S, Cho J, et al. Prognostic relevance of pretreatment quality of life in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP: Results from a prospective cohort study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(11):1747–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowakowski GS, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al. Statin use and prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurer MJ, Micallef IN, Cerhan JR, et al. Elevated serum free light chains are associated with event-free and overall survival in two independent cohorts of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1620–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake MT, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency and prognosis in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4191–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe E, Harris N, Stein N, Vardiman J. Hodgkin Lymphoma Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press, 2001:237–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yost KJ, Thompson CA, Eton DT, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) is valid for monitoring quality of life in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(2):290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sloan JA, Berk L, Roscoe J, et al. Integrating patient-reported outcomes into cancer symptom management clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute–Sponsored Clinical Trials Networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5070–5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh JA, Satele D, Pattabasavaiah S, Buckner JC, Sloan JA. Normative data and clinically significant effect sizes for single-item numerical linear analogue self-assessment (LASA) scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butt Z, Wagner L, Beaumont J, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(1):20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leal AD, Allmer C, Maurer MJ, et al. Variability of performance status assessment between patients with hematologic malignancies and their physicians. Leuk Lymphoma 2018;59(3):695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tholstrup D, brown PDn, Jurlander J, Bekker jeppesen P, Groenvold M. Quality of life in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with dose-dense chemotherapy is only affected temporarily. Leuk Lymphoma 2011;52(3):400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4605–4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streckmann F, Kneis S, Leifert JA, et al. Exercise program improves therapy-related side-effects and quality of life in lymphoma patients undergoing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegel D Mind matters in cancer survival. JAMA. 2011;305(5):502–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3869–3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, Gottheil E. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2(8668):888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3450–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Correlation between PS groups (ps.group), FACT-G overall (fact.g), functional WB (fwb), physical WB (pwb), emotional WB (ewb), social/family WB (sfwb), LASA QOL overall (ov.lasa), and spiritual LASA (sp.lasa).