Abstract

While organotypic approaches promise increased relevance through the inclusion of increased complexity (e.g. 3D extracellular microenvironment, structure/function relationships, presence of multiple cell types), cell source is often overlooked. iPSCs-derived cells are potentially more physiologically relevant than cell lines, while also being less variable than primary cells, and recent advances have made them commercially available at costs similar to cell lines. Here, we demonstrate the use of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelium for the generation of a functional microvessel model. High precision structural and microenvironmental control afforded by the design approach synergizes with the advantages of iPSC to produce microvessels for modeling endothelial biology in vitro. iPSC-microvessels show endothelial characteristics, exhibit barrier function, secrete angiogenic and inflammatory mediators, and respond to changes in the extracellular microenvironment by altering vessel phenotype. Importantly, when deployed in the investigation of neutrophils during innate immune recruitment, the presence of the iPSC-endothelial vessel facilitates neutrophil extravasation and migration towards a chemotactic source. Relevant cell sources, such as iPSC, combine with organotypic models to open the way for improved and increasingly accessible in vitro tissue, disease, and patient-specific models.

Keywords: Organotypic/Organ-on-a-chip, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, In Vitro Modeling, Neutrophils, Endothelial Cells

1. Introduction

‘Organotypic’ approaches greatly advance our ability to recapitulate physiologically relevant biological phenomena by taking us from mono-cultures on flat plastic surfaces to three dimensional multi-cultures containing structure, function, and microenvironmental interactions. [1] [2] Although a number of terms with subtle differences in meaning are used to refer to these approaches (‘organotypic’ and ‘organoid’ for tissue-like structures, ‘biomimetic’ for purposeful biological imitation, or ‘organ-on-a-chip’ for models striving for organ-like function), their collective purpose is clear: improving the correlation between in vitro cell culture models and in vivo phenomena while maintaining tractability. Organotypic design is more than cosmetic: the importance of cell-cell interactions and structure/function relationships is well established. [3] It has even been demonstrated that structure and geometry alone alters endothelial and epithelial cell soluble factor signaling and phenotype. [4] In the study of the innate immune response for example, it has been shown that multi-culture, cell-cell signaling, and cell-matrix interactions alter neutrophil transendothelial migration, chemotaxis behavior, and surface marker expression. [5] [6] [7] The contexts in which these differential behaviors lead to greater physiological relevance is not yet settled, but it is clear organotypic culture greatly influences biological response.

While a plethora of organotypic models now exist, most utilize cell lines, limiting potential relevance. Culture dimensionality, extracellular matrix composition, and structure all contribute, but cell source is a driver of model behavior. Ideally, primary human-derived samples would be used for model creation. However, inter- and intra- patient variability, cell availability, and sample size all limit primary culture models, especially with large numbers of experimental replicates. Thankfully, new opportunities have arisen with the advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived techniques. [8] Like embryonic stem cells, iPSC can be used to create consistent primary-like cells of various types, including endothelium, [9] and now, these advances are not limited by lab-specfic expertise, as commercial sources of iPSC, with proper characterization will facilitate widespread adoption. iPSC combined with reliable organotypic methods will offer impactful opportunities in complex cultures, patient specific recapitulation, and disease modeling. [1] [10]

One application among many others where such models have substantial potential impact is in the investigation of endothelial-neutrophil signaling during innate immune cell recruitment. Innate immunity is a critical part of host defense; neutrophils act as first responders by sensing chemotactic signals and migrating rapidly to sites of injury to combat infection. [11] Furthermore, neutrophil response is heavily regulated by the vasculature, and the endothelium in particular. [12] Neutrophils are critical for proper inflammatory response but also contribute to pathologies associated with cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. [13] As such, there is a great opportunity to target the innate immune response for therapeutic intervention, improving pathogen clearance or limiting improper inflammatory resolution. However, precise control over geometry and the microenvironment is necessary for organotypic endothelial modeling, large-scale investigation of endothelial-regulated neutrophil recruitment, and transmigration during innate inflammation.

A recently established organotypic approach, termed LumeNEXT,[14] provides just such control, facilitating reliable and robust creation of in vitro microvessel structures. Using LumeNext, size, distances, hydrogel composition, structure, and configuration (e.g. multivessel structures and branches, stromal culture) are all highly controllable using standard polydimethylsiloxane micromolding methods. When attempting to model complex systems such as immune recruitment, determining the extent to which each component contributes to a given response is difficult to quantify even in the simplest of setups. So control of cell phenotype, culture geometry, and microenvironmental conditions will need to be increasingly strict in order to single-out contributors and mechanisms associated with complex physiological phenomena. For example, how do we measure how subtle changes in extracellular matrix composition alter endothelial vessel tight junctions and neutrophil extravasation events without duplicable vessel fabrication and reliable cell phenotype? Robust control of in vitro vessel model parameters will be critical, as matrix composition and geometry has been shown to greatly influence endothelial response with self-assembled networks. [14] Thus, the advantages of LumeNEXT synergize directly with those presented by iPSC: 1) Increased tractability and reliability arises from precise culture control provided by LumeNEXT and minimal iPSC-source variability, and 2) physiological relevance is increased by organotypic design and primary-like behavior from iPSC, helping to bridge the gaps present between current in vitro methodologies and animal models.

To this end, here we characterize a repeatable, engineered endothelial vessel by coupling commercial iPSC with the robust organotypic approach with utility in a variety of biological investigations including modeling neutrophil behavior duing innate immune response. Commercial iPS-derived endothelial cells demonstrated classical markers of endothelial phenotype and proved reliable from mulitple lots, over several years of culture. When deployed in organotypic lumen culture, they formed patent, confluent structures and demonstrated primary-like vessel morphologies. iPSC endothelial cells provide barrier function, forming close cell-cell contact and tight junction expression, and also secrete inflammatory and angiogenic mediators. Importantly, the organotypic iPSC model proved responsive to changes in the extracellular matrix composition, showing leaky cancer-associated vessel-like phenotypes in collagen I matrices. Finally through robust expression of p-selectin, endothelial vessels also facilitate neutrophil capture and extravasation, enabling creation of tractable innate immune models. The data demonstrates the utility of coupling iPSC and the LumeNEXT organotypic method, moving towards the creation of more reliable, relevant, and widely adoptable microvessel models.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture:

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from Lonza (Walkersville, Maryland) and maintained in EBM-2 Basal Medium supplemented with the EGM-2 Bullet Kit (human hEGF, hydrocortisone, gentamicin, amphotericin-B, hVEGFa, hFGF-B, R3-IGF-1, ascorbic acid, heparin, and fetal bovine serum to a final serum concentration of 2%). HUVECs were passaged with 0.05% trypsin with EDTA (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) prior to confluency and used through passage 7. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells were obtained from Cellular Dynamics International (Madison, Wisconsin) and maintained in Vasculife Basal maintenance media from LifeLine Cell Technologies (Frederick, Maryland) supplemented with VEGFa, hEGF, hFGF-B, hIGF, ascorbic acid, hydrocortisone hemisuccinate, heparin sulfate, L-glutamine, and iCell Endothelial Cell Medium Supplement (Cellular Dynamics International). iPSC endothelial cells were passaged with 0.05% trypsin with EDTA (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) prior to reaching confluency and used through passage 5. Prior to seeding of endothelial cells on any culture surfaces, a 30 µg/mL bovine fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) solution was incubated for 30 minutes on the culture surface to create fibronectin coatings for improved cell adherence. Human brain vascular pericytes from Sciencell (Carlsbad, California) were cultured in pericytes medium (ScienCell) on surfaces coated with poly-L-lysine (2µg/cm2, minimum incubation of 1 hour) and passaged using 0.05% trypsin with EDTA (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts). Media was exchange on each culture every other day, and all media used was filtered using a 500 mL, 0.2 µm PES filter unit. Freezing for each cell type was performed in culture media supplemented with fetal bovine serum and dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) in a 6:3:1 ratio, respectively.

Human Primary Endothelial Cell Isolation and Culture:

Primary endothelial cells were isolated directly from human kidney tissue. After surgical resection, collected tissue samples were incubated with Lonza (Allansale, NJ) Eagle Minimal Essential Media with Earle’s BSS, L-glutamine, 5 mg/ml collagenase, 5 mg/ml hyaluronidase, 1 mg/ml DNase, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 4 hours at 36°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The dissociated tissue samples were filtered through a 100 μm filter, and cells were collected by centrifugation. Afterwards, cells were washed three times with growth media (MEM media including 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% non-essential amino-acid solution (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts), 0.4 mg/ml hydrocortisone, and 5 µg/ml EGF). Endothelial cells were isolated using an anti-CD31-conjugated magnetic microbeads separation columns per the manufacturers protocol (Miltenyi Biotech, Nycomed, Zürich, Switzerland). CD31 positive endothelial cells were cultured in growth media at 5% CO2 and expanded and assayed for up to four passages, after which senescence limited growth and expasion.

Human Primary Neutrophil Purification:

Peripheral neutrophils from human blood were purified using the Miltenyi Biotech MACSxpress Neutrophil Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nycomed, Zürich, Switzerland). All donors were healthy and informed consent was obtained at the time of the blood draw according to our IRB. For identification, tracking, and viability monitoring, neutrophils are staining with calcien AM per the manufacturer’s protocol, prior to centrifugation and resuspension.

LumeNEXT Device Fabrication:

The microfluidic organotypic culture platform was fabricated using the LumeNEXT approach previously reported in Advanced Healthcare Materials. [15] Briefly, the LumeNEXT approach allows for fabrication of lumen structures where size, organization, distance, and configuration can be controlled using standard polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) micromolding techniques and consists of two primary components: a culture chamber and a removable PDMS rod. Rods can be cast from molds or drawn from needles, with the gauge controlling lumen diameter. The chamber is formed by oxygen plasma bonding two distinct PDMS layers patterned using SU-8 on silicon master molds (SU8–100, MicroChem, Westborough, Massachusetts) onto a glass bottom MatTek dish (Ashland, Massachusetts). Each PDMS layer is patterned with 2 heights: deep (500 µm) features to form the chamber and ledge features (250 µm) to hold the rod across the middle of the culture chamber once the two layers are bonded together. PDMS layers were made using the Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit (Dow Corning, Auburn, Michigan) with a 10:1 curing agent ratio and plasma bonding was performed using a Diener Electronic Femto Plasma Surface System. While LumeNEXT provides considerable flexibility in device design and layout (e.g. branching and multi-lumen layouts), here we utilized single chamber, single lumen layouts interfaced with 3 types of ports: side ports, inlets, and outlets (Figure 1a), andwith rods formed from 24 gauge (~310 µm inner diameter),23 gauge (~340 µm inner diameter), and 17 gauge (~100 µm inner diameter) needles. Rods are placed across the chamber body, from the small inlet port to the large outlet port, creating a lumen body of 2 mm in length. These ports were designed for passive pumping for both cell loading and media exchange and delivery. [16] Side ports perpendicularly oriented facilitate hydrogel/ECM filling once the rod is in place. The final chamber size of 2 mm by 2.25 mm with a 1 mm height creates a sufficiently large culture area where the lumen will be entirely surrounded by ECM. All port openings in this chamber are 400 µm across.

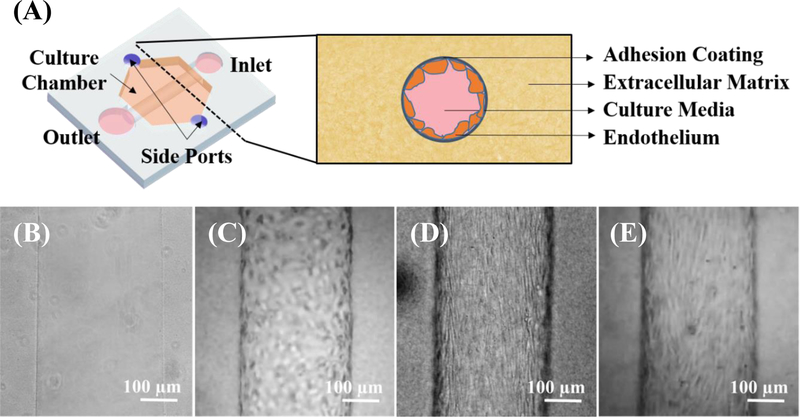

Figure 1.

LumeNEXT organotypic approach enables microvessel modeling. (A) LumeNEXT devices consist of a culture chamber interfaced with 4 ports, across which a PDMS rod is suspended. The culture chamber is filled with a hydrogel of interest via the 2 side ports, and the rod is removed from the outlet utilizing tweezers, leaving behind a lumen in the hydrogel that can be accessed from an inlet and outlet. When viewed in cross section in culture, extracellular matrix surrounds the endothelial cell lined lumen, which has been coated for cell adhesion (i.e. fibronectin) and culture media is flowed in the luminal space. Lumens can be imaged with brightfield microscopy visualizing (B) empty fibrin lumens, as well as, lumens lined with (C) human umbilical vein endothelial cells (D) human primary kidney endothelial cells and (E) iEC-derived endothelial cells, forming model microvessels.

Device and ECM Preparation:

Prior to ECM or cell loading, LumeNEXT devices were sterilized and prepped. Pre-bonded PDMS layers are soxhlet extracted in 100% ethanol and soaked over several days to clean and remove uncured PDMS oligomers. After assembly, devices are UV sterilized for 30 minutes before being moved into a biosafety cabinet. In order to improved matrix adhesion on the PDMS surface within the chamber, the chamber was filled from the side ports with 1% polyethylenimine (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) in DI water for 10 minutes, followed by a 0.1% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) DI water solution. Device were then washed 5x with DI water to remove excess glutaraldehyde. Additional sacrificial PBS is added around the sides of the MatTek dish and dishes are enclosed within Omnitrays to limit dehydration.

After surface preparation, devices are filled from the side ports with the desired matrix. Collagen I matrices were created by neutralizing Corning (Corning, New York) high concentration rat tail collagen I in a 1 to 1 ratio with 7.7 pH 2x PBS/HEPES solution (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) to create a ~4mg, 7.2 pH matrix. Once the mixed collagen solution is loaded into the chamber, devices remain at room temperature for 20 minutes to begin collagen polymerization before being moved into a cell culture incubator. When utilizing fibrin matrices, fibrinogen from bovine plasma (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) is dissolved in Hanks Buffered Solution with calcium chrolide and magnesium chloride (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) to the desired fibrongen concentration (5 mg/mL, 10 mg/mL). Immediately prior to loading into the chamber, the fibrinogen solution was mixed with an appropriate volume of 50 U/mL thrombin from bovine plasma (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) to achieve a final thrombin concentration of 1.25 U/mL. The enzymatic activity of thrombin quickly cleaves fibrinogen to facilitate formation of a fibrin matrix, so the solution must be mixed and dispensed into the chambers within 1 minute. Devices are incubated at 36°C for at least 1 hour prior to cell loading.

Cell Loading:

After incubation, devices are moved into a biosafety cabinet, and a drop of media is placed onto the inlet and outlet port over the lumen rod. Using tweezers, the rod can be easily pulled from the chamber, leaving behind a media-filled lumen within the ECM. LumeNEXT was orignally demonstrated with collagen I matrices, and the compliance of both PDMS and collagen allowed high fidelity molding. When using the technique with significantly stiffer fibrin gels (kPA) [17] for iECs, an additional 1% pluronic F127 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) 30 minute rod coating step was added to improve fidelity (Figure S1). To encourage cell adhesion, 30 µg/mL bovine fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) is incubated in the lumen for 20 minutes in both collagen I and fibrin devices. Afterward, the lumen is washed with media 3x. The cells of interested are then trypsinized and resuspended to a concentration of 15,000 cell/µL and loaded into the open lumen via passive pumping. The lumens can then be placed into the cell culture incubator. Every 45 minutes, the MatTek bonded devices are flipped (upside-down, rightside-up, and so on) to allow cells to adhere around the entire lumen surface. After 4 hours of incubation and flipping, unadhered cells can be aspirated from the lumen and replaced with fresh media.

Lumen Staining Protocol:

As a result of the 3D microenvironment and extracellular matrix, significant background nonspecific fluorescence can be expected from antibody staining. As such, an extended staining protocol is required. First, media is removed from the lumens via aspiration, and the lumen is washed with 1x PBS (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts). After washing, the lumen are fixed with 4% PFA (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, Massachusetts) for 15 minutes and then washed 3 times with 1x PBS. When non-specific binding in the 3D matrix is especially problematic, an additional room-temperature incubation with 0.01M glycine in PBS for 30 minutes can be added. Cell membranes are permeabilized with 0.2% triton X-100 (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, California) for 30 minutes followed by three 1x PBS wash steps. Subsequent blocking is performed by adding 3% bovine serum albumin, BSA, (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) to the lumens for overnight incubation. The following day, primary antibodies (e.g. CD31, P-selectin, I-CAM) can be added at a 1:50 dilution in 3% BSA and incubated for 2 nights. Afterwards, the primary is removed and the lumens are washed with 0.1% tween 20 (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) in PBS at least 3 times, leaving the wash buffer in overnight.. The secondary animal-matched antibody can then be added 1:100 in BSA for a 2 night incubation prior to a final 3 0.1% tween in PBS wash steps. At this stage, Alexa conjugated-phalloidin (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) or Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) can be added 1:50 and incubated for 30 minutes for actin cytoskeletal staining or for nuclear staining, respectively. The LIVE/DEAD Cell Viability Assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts) was used pre manufacturer’s protocol with an additional 3x wash in the evaluation of cell viability.

Image Acquisition:

Bright-field and fluorescent images were obtained using a Nikon TI Eclipse inverted microscope (Melville, New York) and processed using Nikon Elements and the National Institutes of Health ImageJ software. Time-lapse imaging was performed on a Nikeon Eclipse TE300 (Melville, New York) scope and images were taken every 2 minutes over each time period in both phase and fluorescent illumination. Confocal images were acquired using a Leica SP8 (Wetzlar, Germany) in the University of Wisconsin, Madison Optical Imaging Core.

Neutrophil Extravasation and Chemotaxis Setup:

Lumens were seeded with endothelial cells as described above and allowed to culture for 2 days with media exchange twice daily. Primary neutrophils were captured as described and, prior to loading, were dyed with calcein am (Life Technologies) at 2.5 µg/mL for 10 minutes. Neutrophils were resuspended to a concentration of 2×107 cell/mL were loaded into the lumens via passive pumping in a 1:1 mixture with culture media. Neutrophils were observed to both settle into the lumen body and attach along the side walls of the endothelium. Neutrophils were then signaled to extravasate and migrate through the addition of 3 uL a chemoattractant source (fMLP, IL-8) onto the perpendicular side port, creating a gradient of signals across the lumen body. Lumens were immediately imaged using the Nikeon Eclipse TE300 and fluorescent microscopy.

MagPix Secretion Analysis:

Multiplexed protein secretion analysis was performed on iPSC-derived in vitro vessels using the MagPix Luminex Xmap (Luminex Corporation, Austin, Texas) with the Milliplex human angiogenesis growth factor panel bead kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts) per the manufacturer protocol. Conditioned maintenance media was retrieved twice daily on days 1 and 2 from 3 replicates of iPSC-derived vessels using a p10 pipette, yielding 2 µL per lumen. Maintenance media was also extracted from empty lumen devices (i.e. no endothelium) for normalization, and the media collected from days 1 and 2 was combined to increase sample volume in each condition. Data from the MAGPIX assay were calculated using mean fluorescence intensities.

Atomic Force Microscopy:

Gel stiffness was measure utilizing atomic force microscopy (AFM). 10 mg/mL fibrin gels were prepared as described above on open well glass substrates, and measurements were take using a Bruker Catalyst Bioscope AFM at the Material Science Center at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. At least 10 force curves were generated for each of 4 fibrin samples using a 5 µm borosilicate bead tiped probe from NovaScan (Ames, IA) to determine the Young’s modulus.

3. Results

3.1. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Endothelium

Endothelial cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) are an attractive alternative cell source for organotypic models, as iPSC-derived cells can be more physiologically relevant than cell lines, while minimizing the patient-to-patient variability of primary samples. [9] However, since many labs lack the needed infrastructure or expertise for iPSC differentiation, commercially available sources are particularly important for widespread adoption of new methods. The commercially-available iPSC-ECs used herein, termed iEC (CDI, Madison, Wisconsin), were reported to express endothelial markers and functional properties of endothelium consistent with primary cells (e.g. TNF-α activation, dynamic barrier function, shear stress response, and undirected capillary-like network formation in several contexts). [18] We observed significant reproducibility in culture of iEC from several lots of cells (e.g. manufacturer #1833921, #1910001) across nearly 2 years of use. In 2D culture 3 days post-plating, cells are 95.5±2.5% CD31/CD105 double positive (PECAM-1 and endoglin, respectively) with a viability of 91%. Endoglin, a transmembrane glucoprotein, and PECAM-1, an integral membrane glycoprotein concentrated at junctions between adjacent cells, have been shown to identify vascular endothelial cells in a variety of contexts. [19] [20] [21] After 4 days in culture, cells demonstrate an average doubling time of 43.6 hours. In comparison, pooled donor human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), a well-accepted primary endothelial source, were 98% CD31/CD105 double positive with a viability of 92% and a 23-hour doubling time. Importantly, there was little observed morphological variation of different iEC lots in culture (Figure S2). Additionally, successful expansion, freezing, and subculture could be maintained through 8 passages, though decreased proliferation and viability after passage 5 constrains passage use. Sub-passaging and freezing did not observably alter resulting 2D or 3D culture phenotype.

3.2. LumeNEXT iPSC-Derived Vessel

The LumeNext approach reliably controls vessel size, distances, hydrogel composition, structure, and configuration in the creation of 3D embedded organotypic endothelial lumens using standard polydimethylsiloxane micromolding methods (Figure 1). [15] Robust control of in vitro vessel model parameters is critical, as matrix composition and geometries has been shown to greatly influence endothelial response in the context of self-assembled networks. [14] Expanding on the HUVEC vessels formed in collagen previously, [15] LumeNEXT vessels were successfully formed in 10mg/mL fibrin with HUVECs, iECs, and even primary human endothelial cells isolated from kidney tissue (Figure 1c–e), and vessels can be maintained in culture for longer than 2 weeks. iEC-derived microvessels (Figure 1e) show parallel morphological elongation down the length of the vessel, similar to primary cells (Figure 1d) and vessels in vivo, even without an external shear stress from flow. This phenotype was not observed in HUVEC-derived models (Figure 1c).

3.3. iEC Show Physiological Characteristics

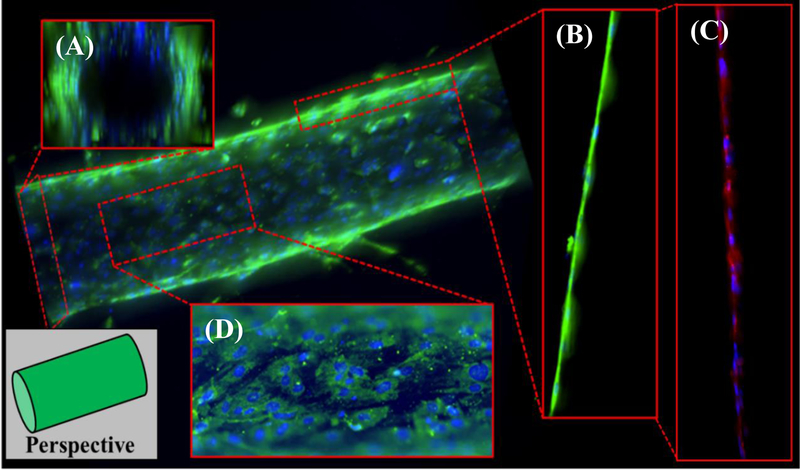

When assessing the physiological behaviors of the model, we evaluated the organotypic vessel in the context of the in vivo function of endothelial cells. Namely, endothelial cells should provide structure by forming the inner lining of a hollow lumen, regulate passage of cells and other substances, and secrete mediators that influence vascular dynamics, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Organotypic lumens of iECs were created in 10 mg/mL fibrin matrices and cultured prior to fixation, staining, and fluorescent imaging (Figure 2). iEC vessels are structurally sound, patent, confluent, and hollow, forming a lumen through which media and other fluids (such as blood) can be flowed (Figure 2a). Endothelial cells form a monolayer surrounding the lumen and show intimate cell contact (Figure 2b). This endothelial barrier along the lumen also stains positive for ZO-1 (Figure 2c, Figure S3). Positive ZO-1 staining is indicative of the formation of tight junction that can regulate the passage of signaling molecules and cells [22] and also suggests a possible mature vessel phenotype. [23] The endothelial cells must also express binding proteins such, as P-selectin (CD62P), to capture and transport cells (such as neutrophils and monocytes during the innate immune response) across these tight junctions, [24] and we observed significant expression of P-selectin across the endothelial vessel surface (Figure 2d). Vessel size is easily controllable through changes in PDMS rod diameter, with vessels of 300 µm (Figure 2) and 100 µm (Figure S4) demonstrated herein.

Figure 2.

iEC organotypic endothelial models formed using LumeNEXT approach display key characteristics of microvessels when visualized using fluorescent Z-stack microscopy (green – p-selectin, blue – hoechst 33342, red – ZO-1). (A) iEC form the inner lining of the luminal space creating patent, confluent cellular structures through which fluids can flow. (B) Cells display intimate cell-cell contact along the edge of the vessel, and (C) these contacts express moderate levels of ZO-1, suggesting tight junction formation. (D) Ubiquitous P-selectin expression along the surface of the endothelial enables leukocyte capture and regulation of cell adhesion on the endothelium surface for inflammation modeling applications.

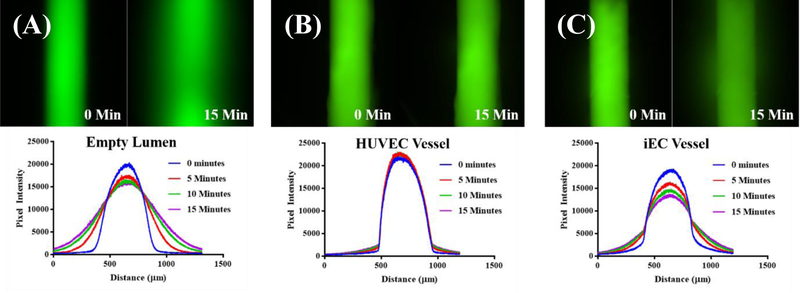

In vivo, the regulation of macromolecule transport across the endothelial vessel is controlled by vessel barrier function, and while visualization of tight junctions is suggestive of this, direct assessment via fluoresent permeability assays is a well accepted measure of barrier function in vitro. [25] FITC-conjugated 70 kDA dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) at 50 µg/mL was flowed into the lumen of the vessel, and the intensity was measured over time. As there is a linear relationship between fluorescence intensity and fluorophore concentration, we can acheive a measure of barrier function by calculating percent flux over time. [26] Using this method, the barrier function of empty, iEC, and HUVEC lumens was assessed (Figure 3). As expected, empty (i.e. no endothelial cells) fibrin lumens displayed little to no barrier function, with significant diffusion of dextran from the lumen within 15 minutes (Figure 3a). In contrast, minimal dextran (~7x less, Figure S5) diffused from HUVEC vessels, confirming HUVEC tight junction formation as is reported in the literature (Figure 3b). [27] iEC-derived vessels show an intermediate barrier phenotype (~2x less, Figure 3c, Figure S5) but restricted 70 kDA as well as 10 kDA (Figure S5) macromolecule passage.

Figure 3.

iEC-derived microvessels display barrier function. (A) Unlined (empty) 10 mg/Ml fibrin lumens permit diffusion of 70 kDa FITC-dextran (comparable to 66.5 kDa serum albumin) over the course of 15 minutes after loading a 50 µg/mL solution. (B) In contrast, HUVEC lined model vessels restrict the passage of macromolecule-sized dextran over a 15 minute time period. (C) iEC-derived microvessels also restrict diffusion of 70 kDa dextran compared to empty lumens, but display a weaker barrier function compared to HUVEC-lined structures.

Endothelial vessels are also supported by a variety of stromal cells including fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and pericytes, such as in the case of microvessels. [28] In order to show functional response to co-culture in our organotypic microvessel, we demonstrated increased vessel sprouting with pericyte co-culture. In vivo, pericytes are smooth muscle-like cells that cover the surface of microvessels and make close contacts with the endothelial cells [29], so primary human brain vascular pericytes (HBVPs) were loaded with endothelial cells during seeding at a 10:1 endothelial to pericytes ratio to create an endothelial-pericyte co-culture vessel. Vessels with and without HBVPs were exposed to 25 ng/mL VEGF/serum media from the side ports, and the resulting sprouting response was observed. By day 14, pericyte-rich vessels showed sprouting phenotypes, filling the entire culture chamber, while iECs alone did not (Figure S6). HBVPs have been seen to play a significant role in the regulation of angiogenesis and the survival of endothelial cells, [30] so these results are promising. Moving forward, reproducible in vitro endothelial vessels capable of responding to vascular pericytes activity will be useful for large scale modeling and screening of effectors of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. [31]

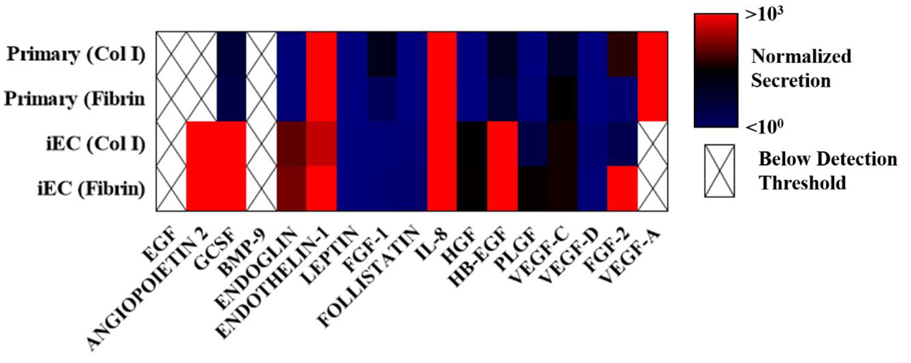

Finally, the endothelial cells within a vessel not only control permeability and facilitate blood transport but also are significant paracrine signallers, contributing to coagulation, angiogenisis, and, importantly, immune response. [32] In order to evaluate the secretion profile of our organotypic vessel, Luminex multiplexed human growth and angiogenic factor protein analysis was performed. Culture media from within primary endothelial and iEC lumens was collected and analyzed over a 2 day period (Table 1). Cytokine secretions from iECs and primary endothelial cells in 4 mg/mL collagen and 10 mg/mL fibrin were normalized lumens filled only with the corresponding culture media. We see the secretion of a number of important inflammatory and angiogenic regulators such as IL-8, FGF-2, VEGFs, G-CSF, angiopoeitin-2, endothelin-1, HGF, and endoglin. Important to note, EGF and VEGF-A, which were present in both culture media, were not detectable above media levels for several conditions. Additionally, significant levels of angiopoeitin-2 were detectable only in iEC vessels, in both collagen and fibrin matrices. Finally, extracellular matrix composition (collagen vs fibrin) was seen to alter secretion in both iEC and primary endothelial cells. This diversity in phenotype is expected considering the diversity in source, [33] but it should be considered when using this approach to engineer specific models that are designed to recapitulate particular physiological systems.

Table 1.

Magpix analysis of in vitro vessel secretion. Inflammatory and angiogenic cytokine secretion is visualized as a logarithmic heatmap (n=3, pooled samples over 2 days). Color scale represent secretion levels with the background normalized by subtracting the contributions of blank (no endothelial cells) collagen or fibrin lumens. Blanks for primary endothelial cells and iEC were filled with the growth media of primary endothelial cells or iEC, respectively. Analytes that were undetectable or below the levels present in the media were excluded and displayed as a crossed out blank. Angiopoietin-2, G-CSF, IL-8,FGF-2 with iECs exceeded 103 relative secretion.

|

3.4. ECM Composition Modulates Barrier Function

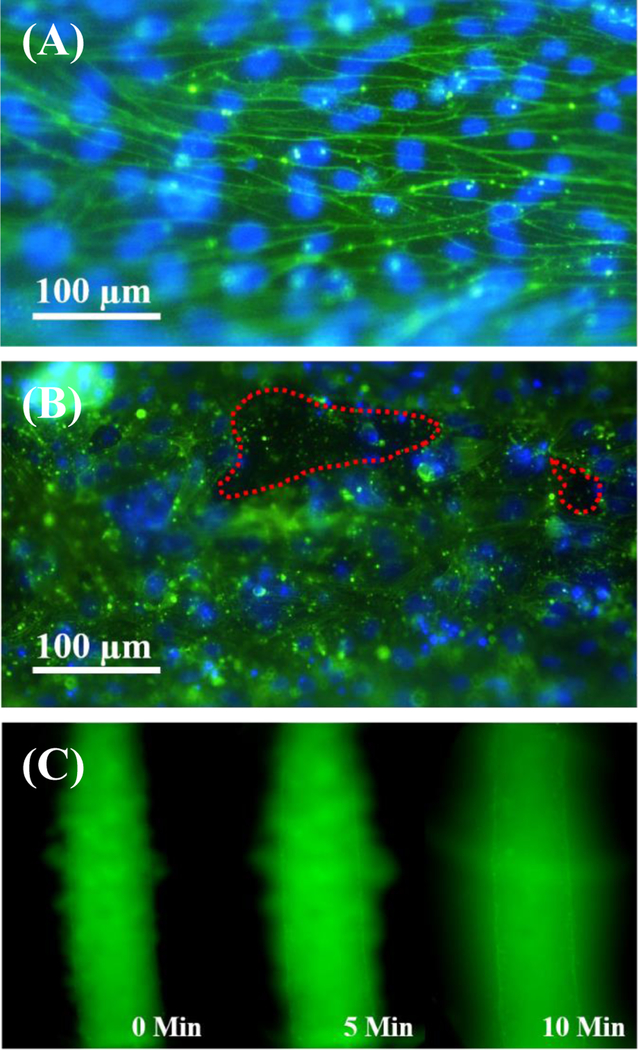

Fibrin has seen extensive use as a natural extracellular matrix in engineered vascular models and has been successful herein. [34] However, fibrin lacks the mechanical properties of native ECM, and differences in endothelial integrin-matrix binding may alter vessel behavior as seen in the MagPix results. [35] [36] As such, we also characterized iEC vessels in collagen I matrices to assess potential differences in response. iEC in fibrin ECM organotypic vessels show strong alignment parallel to the vessel length and morpohological elongation (Figure 1e, Figure 4a), as is observed with primary human endothelial cells (Figure 1d). This alignment is observed in the cytoskeletal organization as well, with cells taking on the physiological morphology of cells responding to shear stress in the lumen structure even without the presence of constant shear stress from flow. [37] The actin cytoskeletal organization of iEC vessels in fibrin supports our observation of tight junction behavior. Higher fluorescent signal around cells borders marks the cortical actin rim of the iEC. Cortical actin is attached to the cell membrane and is associated with cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix adhesions that hold cells in tight contact with each other and the matrix. [38] [39] The secretion of HGF that was observed from iEC may also contribute to this phenotype, as HGF has been shown to enchance cortical actin reorganization, improving barrier function. [40] There was initial concern that PDMS rods were imprinting micropatterns on the ECM surface during fabrication or from rod removal, as there are topographies on the rod surface (Figure S7) and pulling from the matrix may impart an aligned pattern. Yet neither fibrin nor collagen I surfaces show evidence of such alignment or patterning (Figure S8), and HUVEC cells cultured on these surfaces show no morphological differences (Figure 1c). The observed actin phenotype, however, is completely disrupted in vessels formed in collagen I extracellular matrices (Figure 4b). Cortical actin rims are less distinct, and gaps in the endothelial vessel can be easily visualized. Endothelial cells more readily migrate out of the lumen structure as individuals, and permeability testing with 70kDA FITC-dextran showed clear visualization of a leaky vessel phenotype (Figure 4c) with holes through which the macromolecules could easily diffuse. This endothelial morphology is closer to what is seen in tumor-associated endothelium [41] and may be a synergistic response to the collagen I matrix and the high levels of angiopoeitin-2 that are being secreted by the iEC (Table 1), as angiopoeitin-2 can be associated with vessel disruption and reorganization. [42] Additionally as previously noted, collagen I matrices are less mechanically stiff than those formed with fibrin at simlar concentrations, and it has been reported that endothelial cells preferentially develop more spread morphologies with stronger actin stress fibers on stiffer matrices. [43] While exact values for fibrin stiffness vary depending on preperation and source, measurements fall within the range of a few kPA for matrices in the 3 to 10 mg/mL range. [44] [45] Indeed, we obtained similar values with our own gels, measureing a stiffness of 4.7 ± 0.53 kPA for a concentration of 10mg/mL via atomic force microscopy. In contrast, collagen I stiffnesses are reported in the ranges of 10s to 100s Pa, [46] an order of magnitude lower at least. As there are likely many contributors to this differential response that could be investigated in considerably greater detail, these observations together highlight the need for additional ECM engineering: although collagen I is a major component of adult vessel ECM, endothelial cells normally must degrade basement membrane before adopting migratory and proliferative phenotypes within interstitial spaces rich with collagens. [47] Regardless, this responsiveness to changes in microenvironmental composition can be harnessed for the creation of diverse model phenotypes.

Figure 4.

Matrix composition alters iEC vessel barrier function. (A) Fluorescent microscopy (green – FITC-conjugated phalloidin, blue – hoechst 33342) for the visualization of the 10 mg/mL fibrin iEC vessel cytoskeleton reveals alignment parallel to the vessel length, morphological elongation, and strong cortical actin expression, supporting tight cell-cell contact and vessel maturity. (B) Fluorescent visualization of iEC vessels formed in 4 mg/mL collagen I matrices lack obvious cortical actin or morphological elongation and alignment, and they display observable holes in the iEC microvessel monolayer (outlined in red). (C) Permeability testing with 70 kDa FITC-dextran for collagen I ECM vessels highlights the leaky phenotype with observable dextran leakage through holes immediately after loading and significant diffusion by 10 min.

3.5. iEC Vessels Support Neutrophil Extravasation

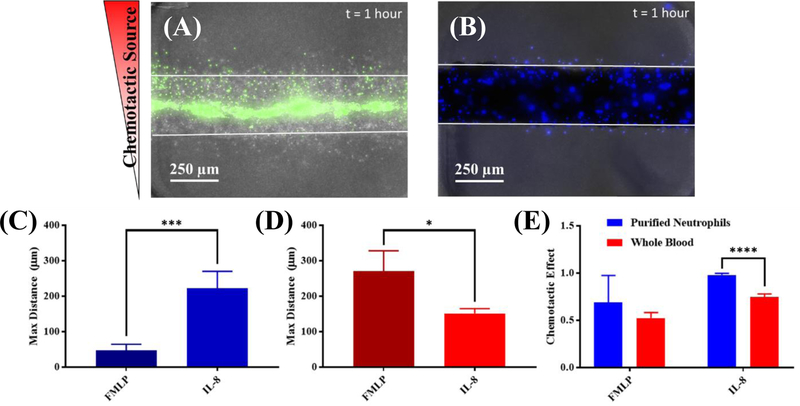

During the innate immune response, neutrophils extravasate through the endothelium, migrate to sites of infection and wounding following chemotatic gradients, release cytokines/chemokines for immune activation, and suppress invading pathogens. [48] [49] It has been long established that proper innate response requires coordinated secreted and contact mediated interactions between neutrophils and the endothelium. [12] [50] Thus, providing a vessel that can capture leukocytes, modulate barrier function, and secrete mediators to support for neutrophil extravastion and migration is critical. To this end, we tested the ability of our iEC vessels to support a tractable system to study neutrophil extravasation. Primary neutrophils were collected from healthy donors, purified, mixed 1:1 with media, and loaded into lumens formed 1 day prior in collagen I matrices. Matrices were formed from collagen I in this context as it has been reported that increasing concetrations of fibrin inhibit the ability of neutrophils to migrate through a matrix, [51] though preliminary testing indicates extravasation and migration of neutrophils from vessels in fibrin is possible over longer times of observation (Figure S9). Exogenous sources of IL-8 (11 µM) or fMLP (10 µM) were added to a side port, generating a gradient across the iEC lumen. Neutrophil chemotaxis was observed in both the presence and absence of iEC cells forming microvessels in the lumen over the course of 1 hour. Neutrophils were flowed into the lumen via passive pumping for capture, but no flow was present during extravasation and migration. In the presence of iEC, we observed increased neutrophil chemotaxis to IL-8, compared to fMLP (Figure 5a,c). Despite the finding that the vessels themselves robustly secrete IL-8, resulting in a shallower gradient when IL-8 is used as the chemoattractant, significantly more neutrophils extravasated (~8x) and migrated further (4x) under this condition (Figure 5c). When this assay was also repeated with whole blood as a neutrophil source mixed 1:1 with media, this trend appeared to reverse with a greater effects observed with fMLP (Figure 5b,d). This reversal coincided with a reduced chemotatic effect (ratio of number migrating towards vs. away) observed when using whole blood as well (Figure 5b,e). As the whole blood may contain a number of unspecified inflammatory factors as well as other non-neutrophil white blood cells, tracking of neutrophil extravasation and migration (via hoechst staining) was less specific in whole blood, though the time scale (1 hour) and migration speed suggest extravasating cells should be neutrophils.

Figure 5.

iEC microvessels support neutrophil extravasation and migration. (A) Fluorescent microscopy of iEC lumen (green – calcein am) shows successful extravasation and migration of labeled purified neutrophils towards an IL-8 source (top); individual iEC also migrate and sprout from the vessel formed in 5mg/mL collagen I, but can be differentiated due to the lack of calcein stain. Image is displayed as a maximum intensity project across a Z-stack in order to visualize neutrophil migration in multiple planes. (B) Maximum intensity project cell extravasation and migration from whole blood (blue – hoechst 33342) in the iEC lumen. Migratory cells, likely to be neutrophils on this time scale, migrate both towards and away from IL-8 source when left as whole blood. (C) Quantification of maximum migration distance shows purified neutrophils migrating significantly farther in response to 11 µM IL-8 (p=0.0005, n=4) than 10 µM fMLP. (D) A less significant, but opposite trend regarding maximum migration distance (p=0.0192, n=4) is observed when using whole blood for neutrophil extravasation, with greater total migration observed using fMLP. (E) Increased variability and decreased chemotactic effect (number of cells migrating up the gradient compared to total number of migrating cells) is observed with whole blood samples, likely contributing conflicting results. Purified neutrophils trend toward increased chemotactic effect with fMLP (p=0.2925, n.s., n=4) but significantly increase positive chemotaxis with IL-8 gradients (p ≤0.0001, n=4).

4. Conclusion

Through the use of robust organotypic design and a readily available iPSC-derived endothelial cell source, we have successfully demonstrated an in vitro model of a microvessel that displays lumen structure, barrier function, secretes angiogenic and inflammatory mediators, responds to its ECM and co-culture, and supports immune cell (neutrophil) trans-endothelial extravasation and migration. Our microscale lumen culture approach directly synergizes with the advantages provided by commercial-iPSC endothelial cells. The LumeNEXT micro-culture approach allows the fabrication of 3D embedded lumens where size, structure, distance, and configuration are all tightly and precisely controlled using standard, widely-available PDMS methods. Furthermore, devices are controlled and operated with no more than a micropipette and tweezers enabling low expertise operation and deployment in a variety of lab settings. Likewise, the iEC proved capable of physiological behaviors in organotypic culture, while also being simple to use and maintain. They require only standard culture techniques similar to those used with cell lines and were phenotypically robust over years of use with various lots. With this synergy, these iEC LumeNEXT microvessel models are accessible and amenable to large-scale integration and high throughput screening approaches, thus facilitating systemic investigations of the intrinsic regulators and potential clinically relevant compounds acting on the inflammatory recruitment of neutrophils through blood vessels. Neutrophil-endothelial interactions are critical in the regulation of neutrophil function and the innate immune response, and the demonstration of a tractable, robust, and physiologically relevant model of these interactions will prove useful as we work to unravel the complexity in neutrophil recruitment and resolution.

The increased use of organotypic culture has the potential to greatly diminish the gap that is often observed between in vivo and in vitro models, improving investigations in cell biology and tissue engineering, as well as advancing personalized medicine and disease modeling. While primary cells from clinical patients can be hard to obtain regularly and reliably and may vary over time, iPSC can be used, maintaining physiological relevance and offering the opportunity to recapitulate disease phenotypes through genetic manipulation. Disease phenotypes can be engineered using CRISPR/Cas9, overexpression of dominant gene mutations in the iPSC parent lineage, or derivation of iPSC from individuals suffering from genetic syndromes directly. With complex organotypic multi-cultures, researchers can also derive all cellular components from the same genetic lineage. Looking toward the future, patient-specific models are not far off considering the advances made in both microscale and organotypic culture and iPSC technology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through R01 CA186134 and R35 GM1 18027 01 in addition to Hematology T32 HL07899 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Karina Lugo-Cintron, Dr. Yan Wu, Dr. Moon Hee Lee, Dr. Jason Abel, Julie Last, and Wilson Hoppe to this work and the guidance provided by Drs. Jordan Miller and Gisele Calderon of Rice University and Dr. Dave Mann and Rachel Llanas at Cellular Dynamics International.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

David J. Beebe is a board member and stockowner of Tasso, Inc. and a stockowner of Bellbrook Labs, LLC. David J. Beebe is a founder, stockowner, and consultant of Salus Discovery LLC. David J. Beebe is an advisor and stockowner of Lynx Biosciences, LLC, Onexio Biosystems, LLC, and Stacks to the Future, LLC. David J. Beebe also holds equity in Bellbrook Labs, LLC, Tasso Inc., Salus Discovery LLC, Stacks to the Future, LLC and Onexio Biosystems, LLC.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- [1].Shamir E and Ewald A, “Three-dimensional organotypic culture: experimental models of mammalian biology and disease,” Nature Reviews, vol. 15, pp. 647–664, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Esch E, Bahinski A and Huh D, “Organs-on-chips at the frontiers of drug discovery.,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 14, pp. 248–260, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lelièvre S and Bissell M, Three Dimensional Cell Culture: The Importance of Microenvironment in Regulation of Function: Reviews in Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bischel L, Sung K, Jiménez-Torres J, Mader B, Keely P and Beebe D, “The importance of being a lumen.,” FASEB J, vol. 28, no. 11, pp. 4583–4590, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yamahashi Y, Cavnar P, Hind L, Berthier E, Bennin D, Beebe D and Huttenlocher A, “Integrin associated proteins differentially regulate neutrophil polarity and directed migration in 2D and 3D.,” Biomed Microdevices, vol. 17, no. 5, p. 100, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wu X, Newbold M and Haynes C, “Recapitulation of in vivo-like neutrophil transendothelial migration using a microfluidic platform,” Analyst, vol. 140, pp. 5055–5064, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kim D and Haynes C, “On-Chip Evaluation of Neutrophil Activation and Neutrophil– Endothelial Cell Interaction during Neutrophil Chemotaxis,” Anal. Chem, vol. 85, no. 22, p. 10787–10796, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yu J, Vodyanik M, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane J, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir G, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin I and Thomson J, “Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells,” Science, vol. 318, no. 5858, pp. 1917–1920, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Adams W, Zhang Y, Cloutier J, Kuchimanchi P, Newton G, Sehrawat S, Aird W, Mayadas T, Luscinskas F and García-Cardeña G, “Functional Vascular Endothelium Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells,” Stem Cell Reports, , vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 105–113, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Williamson A, Singh S, Fernekorn U and Schober A, “The future of the patient-specific Body-on-a-chip,” Lab Chip, , vol. 13, pp. 3471–3480, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes G, Metzler K and Zychlinsky A, “Neutrophil Function: from mechanisms to disease,” Annu Rev Immunol, vol. 30, pp. 459–489, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Muller W, “How endothelial cells regulate transmigration of leukocytes in the inflammatory response.,” Am J Pathol, vol. 184, no. 4, pp. 886–896, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mueller K, “ Inflammation’s Ying-Yang,” Science, vol. 339, no. 6116, p. 155, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chung S, Sudo R, Mack P, Wan C, Vickerman V and Kamm R, “Cell migration into scaffolds under co-culture conditions in a microfluidic platform.,” Lab Chip, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 269–275, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jiménez-Torres J, Peery S, Sung K and Beebe D, “LumeNEXT: A Practical Method to Pattern Luminal Structures in ECM Gels,” Advanced Healthcare Materials, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 198–204, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Walker G and Beebe D, “A passive pumping method for microfluidic devices.,” Lab Chip, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 131–134, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Duong H, Wu B and Tawil B, “Modulation of 3D Fibrin Matrix Stiffness by Intrinsic Fibrinogen–Thrombin Compositions and by Extrinsic Cellular Activity,” Tissue Engineering: Part A, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 1865–1876, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Belair D, Whisler J, Valdez J, Velazquez J, Molenda J, Vickerman V, Lewis R, Daigh C, Hansen T, Mann D, Thomson J, Griffith L, Kamm R, Schwartz M and Murphy W, “Human Vascular Tissue Models Formed from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Dervied Endothelial Cells,” Stem Cell Rev and Rep, vol. 11, pp. 511–525, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Letamendía A, Lastres P, Botella L, Raab U, Langa C and Velasco B, “Role of endoglin in cellular responses to transforming growth factor-β: A comparative study with betaglycan.,” Journal Biol Chem, vol. 273, pp. 33011–33019, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fonsatti E, Vecchio L, Altomonte M, Sigalotti L, Nicotra M and Coral S, “Endoglin: An accessory component of the TGF-β-binding receptor-complex with diagnostic, prognostic, and bioimmunotherapeutic potential in human malignancies.,” J Cell Physiol, vol. 188, pp. 1–7, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fukumitsu R, Takagi Y, Yoshida K and Miyamoto S, “Endoglin (CD105) is a more appropriate marker than CD31 for detecting microvessels in carotid artery plaques.,” Surg Neurol Int, vol. 4, p. 132, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yeon J, Ryu H, Chung M, Hu Q and Jeon N, “In vitro formation and characterization of a perfusable three-dimensional tubular capillary network in microfluidic devices.,” Lab Chip, vol. 12, pp. 2815–2822, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kim S, Lee H, Chung M and Jeon N, “ Engineering of functional, perfusable 3d microvascular networks on a chip.,” Lab Chip, vol. 13, pp. 1489–1500, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky M and Nourshargh S, “Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated.,” Nat Rev Immunol , vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 678–689, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morgan J, Delnero P, Zheng Y, Verbridge S, Chen J, Craven M, Choi N, Diaz-Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, López J, Corso T, Fischbach C and Stroock A, “Formation of microvascular networks in vitro.,” Nat Protoc, vol. 8, pp. 1820–1836, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chattopadhyay R, Dyukova E, Singh N, Ohba M, Mobley J and Rao G, “Vascular endothelial tight junctions and barrier function are disrupted by 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid partly via protein kinase C ε-mediated zona occludens-1 phosphorylation at threonine 770/772.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 289, no. 6, pp. 3148–3163, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lee J, Zeng Q, Ozaki H, Wang L, Hand A, Hla T, Wang E and Lee M, “Dual Roles of Tight Junction-associated Protein, Zonula Occludens-1, in Sphingosine 1-Phosphate-mediated Endothelial Chemotaxis and Barrier Integrity,” J Biol Chem, vol. 281, pp. 29190–29200, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hughes C, “Endothelial-stromal interactions in angiogenesis,” Curr Opin Hematol, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 204–209, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Armulik A, Abramsson A and Betsholtz C, “Endothelial/pericyte interactions.,” Circ Res, vol. 97, p. 512–523, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rucker H, Wynder H and Thomas W, “Cellular mechanisms of CNS pericytes.,” Brain Res. Bull, vol. 15, pp. 363–369, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Allt G and Lawrenson J, “Pericytes: cell biology and pathology.,” Cells Tissues Organs, vol. 169, pp. 1–11, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sumpio B, Riley J and Dardik A, “Cells in focus: endothelial cell,” Int J Biochem Cell Biol, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 1508–1512, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aird W, “Endothelial Cell Heterogeneity,” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 2, no. 1, p. a006429, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shaikh F, Callanan A, Kavanagh E, Burke P, Grace P and McGloughlin T, “Fibrin: a natural biodegradable scaffold in vascular tissue engineering.,” Cells Tissues Organs, vol. 188, pp. 333–346, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Haasa T and Madria J, “Extracellular Matrix-Driven Matrix Metalloproteinase Production in Endothelial Cells: Implications for Angiogenesis,” Trends Cardiovasc Med, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 70–77, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Madri J, Marx M, Merwin J, Basson C, Prinz C and Bell L, “Effects of soluble factors and extracellular matrix components on vascular cell behavior in vitro and in vivo: Models of de-endothelialization and repair,” J Cellular Biochem, vol. 45, no. 2, p. 123–130, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Malek A and Izumo S, “Mechanism of endothelial cell shape change and cytoskeletal remodeling in response to fluid shear stress.”,” J Cell Science, vol. 109, pp. 713–726, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky S, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D and Darnell J, 18.1 The Actin Cytoskeleton, Molecular Cell Biology 4th edition, New York: W.H. Freeman, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Prasain N and Stevens T, “The actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes.,” Microvascular Research, vol. 77, pp. 53–63, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu F, Schaphorst K, Verin A, Jacobs K, Birukova A, Day R, Bogatcheva N, Bottaro D and Garcia J, “Hepatocyte growth factor enhances endothelial cell barrier function and cortical cytoskeletal rearrangement: potential role of glycogen synthase kinase-3β,” FASEB, vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 950–962, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dudley A, “Tumor Endothelial Cells,” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med , vol. 2, no. 3, p. a006536, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fagiani E and Christofori G, “Angiopoietins in angiogenesis,” Cancer Letters, vol. 328, no. 1, pp. 18–26, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yeung T, Georges P, Flanagan L, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, Zahir N, Ming W, Weaver V and Janmey P, “Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion.,” Cell Motil Cytoskeleton, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 24–34, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu J, Tan Y, Zhang Y, Xu P, Chen J, Poh Y, Tang K, Wang N and Huang B, “Soft fibrin gels promote selection and growth of tumourigenic cells,” Nat Mater, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 734–741, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Williams C, Budina E, Stoppel WL, Sullivan KE, Emani S, Emani SM and Black LD, “Cardiac Extracellular Matrix-Fibrin Hybrid Scaffolds with Tunable Properties for Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering.,” Acta Biomater, vol. 14, pp. 84–95, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jin T, Li L, Siow R and Liu K, “Collagen matrix stiffness influences fibroblast contraction force,” Biomed Phys Eng Express, vol. 2, p. 047002, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Paku S and Paweletz N, “First steps of tumor-related angiogenesis.,” Laboratory Investigation, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 334–346, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nourshargh S, Hordijk P and Sixt M, “Breaching multiple barriers: leukocyte motility through venular walls and the interstitium.,” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 366–378, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nourshargh S and Alon R, “Leukocyte migration into inflamed tissues.,” Immunity, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 694–707, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Harlan J, “Leukocyte-endothelial interactions,” Blood, vol. 65, pp. 513–525, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hanson A and Quinn M, “Effect of fibrin sealant composition on human neutrophil chemotaxis.,” J Biomed Mater Res, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 474–481, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.