Abstract

Proteases are localized throughout mitochondria and function as critical regulators of all aspects of mitochondrial biology. As such, the activities of these proteases are sensitively regulated through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms to adapt mitochondrial function to specific cellular demands. Here, we discuss the stress-responsive mechanisms responsible for regulating mitochondrial protease activity and the implications of this regulation on mitochondrial function. Furthermore, we describe how imbalances in the activity or regulation of mitochondrial proteases induced by genetic, environmental, or aging-related factors influence mitochondria in the context of disease. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which cells regulate mitochondrial function through alterations in protease activity provide insights into the contributions of these proteases in pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction and reveals new therapeutic opportunities to ameliorate this dysfunction in the context of diverse classes of human disease.

Keywords: mitochondrial proteostasis, mitochondrial quality control, AAA+ proteases

INTRODUCTION

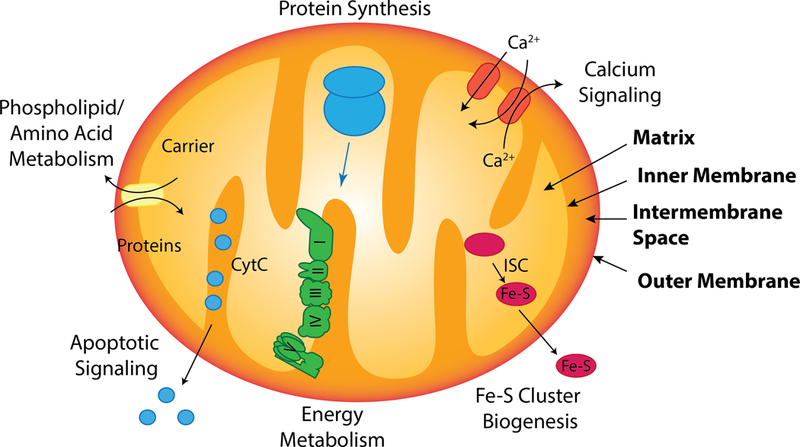

Mitochondria are responsible for essential metabolic and signaling activities within eukaryotic cells (Fig. 1). These include energy production, phospholipid metabolism, and the regulation of apoptotic signaling pathways, all of which require the maintenance of the mitochondrial proteome, also referred to as mitochondrial proteostasis, for their efficient activity. Imbalances in mitochondrial proteostasis induced by genetic, environmental, or aging-related insults are implicated in the pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction associated with diverse diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and many neurodegenerative diseases. A key factor in preventing this pathologic dysfunction is the regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis through the activity of proteases localized throughout mitochondria. These proteases act through a variety of mechanisms to regulate mitochondrial function in response to a given insult and prevent stress-induced dysregulation of mitochondrial proteostasis. The central importance of mitochondrial proteases provides an opportunity for cells to sensitively adapt mitochondrial function to specific cellular demands through the stress-responsive regulation of proteolytic activity. Here, we discuss the mechanisms by which cells regulate mitochondrial proteolytic activity in response to stress. Furthermore, we describe the functional importance of stress-responsive protease regulation and how imbalances in this regulation can promote pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction implicated in diverse diseases.

Figure 1.

Illustration showing select biologic activities localized to mitochondria. The four compartments of mitochondria are shown in bold text.

Organization and activity of the mitochondrial proteolytic network.

Mitochondria are defined by a double membrane architecture resulting in four intramitochondrial compartments: the outer membrane (OM), the intermembrane space (IMS), the inner membrane (IM) and the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 1). Except for those localized to the OM, mitochondrial proteins are not accessible to the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) for degradation. Instead, these mitochondrial proteins are regulated by proteases localized to the IMS, IM, and mitochondrial matrix that promote the maintenance of mitochondrial proteostasis and regulate specific aspects of mitochondrial function (Table 1). Mitochondrial proteases can be generally classified into three categories based on their predominant role in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis and function (Baker et al., 2011; Quiros et al., 2015). Mitochondrial processing peptidases function in the biogenesis and maturation of the mitochondrial proteome. Quality control proteases degrade damaged mitochondrial proteins and regulate specific aspects of mitochondrial biology. Finally, oligopeptidases degrade peptides derived from mitochondrial processing peptidases and quality control proteases into amino acids. Proteases in these categories are diverse in their catalytic activity, ATP dependence, and method of regulation, which reflects their unique functions in coordinating mitochondrial biology (Baker et al., 2011; Quiros et al., 2015). Below we discuss these three classes of mitochondrial proteases and their generalized roles in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis and function.

Table 1.

List of Mitochondrial Proteases and Peptidases discussed in this review.

|

Protease/Peptidase |

Catalytic Activity |

Localization |

Category |

Yeast homolog |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP15 | Cys | OM | Deubiquitinylase | Ubp12 |

| USP30 | Cys | OM | Deubiquitinylase | Ubp16 |

| MEP | Metallo | IMS | Oligopeptidase | Prd1 |

| MIP | Metallo | Matrix | ProcessingGpeptidase | Oct1 |

| PMPCB | Metallo | Matrix | ProcessingGpeptidase | Mas1 |

| PREP|PITRM1) | Metallo | Matrix | Oligopeptidase | Mop112 |

| OSGEPL1 | Metallo | Matrix | Unknown | Qri7 |

| METAP1D(MAP1D) | Metallo | Matrix | Processing peptidase | Map1 |

| XPNPEP3 | Metallo | Matrix | Processing peptidase | Icp55 |

| YME1L | Metallo | IM | Quality Control Protease | Yme1 |

| PARAPLEGIN (SPG7) | Metallo | IM | Quality Control Protease | Yta10 |

| AFG3L2 | Metallo | IM | Quality Control Protease | Yta12 |

| OMA1 | Metallo | IM | Quality Control Protease | Oma1 |

| ATP23 | Metallo | IMS | Quality Control and processing | Atp23 |

| HTRA2 | Ser | IMS | Quality Control Protease | |

| LACTB | Ser | IMS | Unknown | |

| CLPP | Ser | Matrix | Quality Control Protease | |

| LONP | Ser | Matrix | Quality Control Protease | Pim1/Lon |

| IMMP2L | Ser | IM | Processing peptidase | Imp2 |

| IMMP1L | Ser | IM | Processing peptidase | Imp1 |

| PARL | Ser | IM | Quality Control Protease | Pcp1 |

Processing peptidases facilitate establishment of the mitochondrial proteome.

The majority of mitochondrial-localized proteins (>99%) are encoded by the nuclear genome and translated on cytosolic ribosomes. These mitochondrial proteins are directed to the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex by targeting sequences localized at the N-terminus or internally within the polypeptide sequence (Chacinska et al., 2009; Harbauer et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2010). TOM facilitates translocation of these polypeptides across the OM to the IMS where they are further targeted to additional translocase and localization machinery that directs these proteins to specific mitochondrial subcompartments (e.g., the translocase of the inner membrane 23 (TIM23) translocates proteins into the IM and across the IM to the mitochondrial matrix) (Chacinska et al., 2009; Harbauer et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2010). Once localized, these polypeptides are often proteolytically processed by mitochondrial processing peptidases to release the mature polypeptide.

The matrix-localized metalloprotease mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) is a heterodimeric complex comprised of the catalytic MPPβ subunit (PMPCB) and the non-catalytic MPPα subunit (PMPCA) (Kleiber et al., 1990; Ou et al., 1989; Yang et al., 1988). MPP is responsible for removing the N-terminal targeting sequences from mitochondrial proteins targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (Gakh et al., 2002). The removal of this N-terminal targeting sequence releases the mature polypeptide to engage matrix chaperones and folding enzymes that facilitate folding to its native conformation.

MPP-dependent processing of N-terminal targeting sequences can also be the first step in the maturation of mitochondrial proteins that require multiple proteolytic steps for maturation and/or localization. Mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIP) removes an N-terminal octapeptide sequence from select polypeptides that is revealed following MPP-dependent processing of the mitochondrial targeting sequence (Vogtle et al., 2011). The removal of this octapeptide is important as it replaces a destabilizing N-terminal amino acid with a stabilizing N-terminal amino acid. This substitution can prevent degradation of the immature polypeptide through the N-end rule degradation mechanism of the mitochondrial matrix (Vogtle et al., 2011). Similarly, the mitochondrial x-prolyl aminopeptidase XPNPEP3 can cleave a single destabilizing N-terminal amino acid from MPP-processed peptides to reveal a stable N-terminal amino acid (Vogtle et al., 2009). The METAP1D aminopeptidase (also referred to as MAP1D) also regulates N-terminal amino acids of mitochondrial-encoded proteins such as CoxIII by removing the N-terminal methionine as part of an N-terminal methionine excision process (Hu et al., 2007; Serero et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2009). Alternatively, inner membrane protease subunit 1 (IMMP1L) and inner membrane protease subunit 2 (IMMP2L) remove hydrophobic sorting signals from MPP-processed proteins, releasing the mature polypeptide to the IMS (Nunnari et al., 1993). Thus, through the activities discussed above, mitochondrial processing peptidases have critical roles in regulating the maturation, stability, and localization of the mitochondrial proteome.

Mitochondrial quality control proteases regulate the integrity and function of the mitochondrial proteome

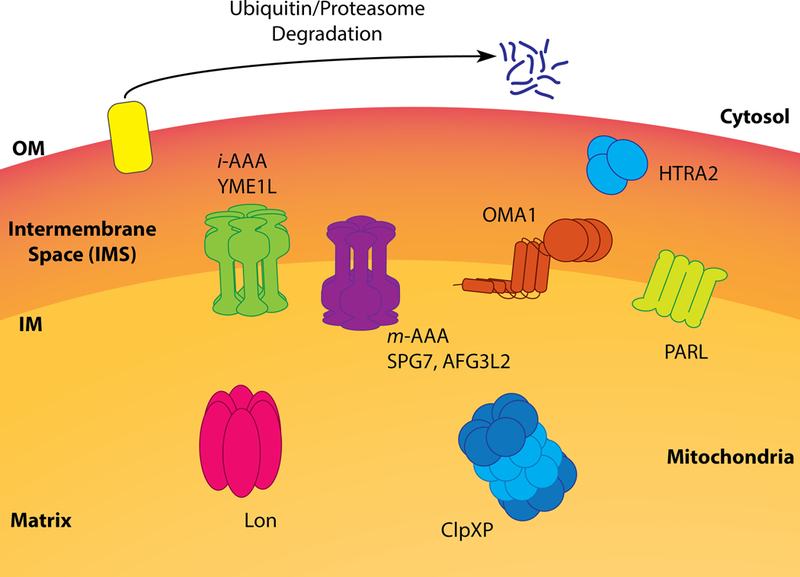

In contrast to mitochondrial processing peptidases, mitochondrial quality control proteases primarily function to remove damaged or misfolded proteins localized to intramitochondrial environments. Four AAA+ ATP-dependent proteases – the i-AAA protease, the m-AAA protease, LON, and ClpXP – are predominantly responsible for performing quality control functions within mitochondria (Fig. 2). These proteases all function through a similar biochemical mechanism that appears to be conserved from bacteria to mammals (Puchades et al., 2017; Sauer and Baker, 2011). Damaged and/or aberrantly-folded proteins are directed to the AAA+ domains of these proteases where they are unfolded through an ATP-dependent process (Puchades et al., 2017; Sauer and Baker, 2011). The unfolded proteins are then translocated to a protected proteolytic core for degradation. Within mitochondria, AAA+ proteases localize to specific intramitochondrial environments such as the IM or the mitochondrial matrix. The localization of these proteases to specific compartments is a primary determinant in dictating their substrate specificity and biologic function.

Figure 2.

The organization and localization of mitochondrial quality control proteases within mitochondria.

The i-AAA and m-AAA proteases are both mitochondrial IM proteases with active sites oriented towards different sides of the membrane. The i-AAA protease is a homooligomer comprised of six subunits of the zinc metalloprotease YME1L. The active site of the i-AAA protease, or more simply YME1L, is oriented towards the IMS, making this the only ATP-dependent protease accessing this mitochondrial subcompartment (Fig. 2). YME1L predominantly functions to degrade damaged, unassembled or misfolded proteins localized to the IM or IMS. This includes many established substrates such as complex I subunits (Stiburek et al., 2012), the core TIM23 subunit Tim17A (Rainbolt et al., 2013), small Tim proteins (Baker et al., 2012b; Spiller et al., 2015), and the phosphatidic acid transporter PRELID1 (Potting et al., 2013). As such, YME1L influences many aspects of mitochondrial biology including electron transport chain activity, mitochondrial protein import, and phospholipid metabolism. YME1L also functions to regulate mitochondrial morphology through the processing of the inner membrane GTPase optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1) in a process that is discussed in more detail below (Griparic et al., 2007; Ishihara et al., 2006; Song et al., 2007). Through these (and other) activities, YME1L has a key role in dictating mitochondrial biology both during normal physiology and in response to pathologic insults.

In contrast to YME1L, the active site of the m-AAA protease is oriented towards the mitochondrial matrix side of the IM (Fig. 2). The m-AAA protease exists in two different oligomeric conformations composed of homooligomers of the zinc metalloprotease AFG3L2 or heterooligomers of AFG3L2 and the zinc metalloprotease paraplegin (Koppen et al., 2007). Interestingly, the relative populations of AFG3L2 and paraplegin differ across mammalian tissues, suggesting that homo- and heterooligomeric m-AAA proteases have distinct functions (Koppen et al., 2007). However, few specific substrates of the m-AAA protease have been identified. It is clear that the m-AAA protease has a critical role in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis through the degradation of damaged or misfolded proteins, as deletion of m-AAA subunits leads to disruption in mitochondrial proteostasis and activation of mitochondrial stress pathways (Richter et al., 2015; Yoneda et al., 2004). Furthermore, m-AAA proteolytic activity regulates mitochondrial calcium homeostasis through the degradation of unassembled essential mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulator (EMRE) subunits of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) (Konig et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2017). Because EMRE ensures the proper association of MCU protein with MICU1 gatekeeping subunit, impaired degradation of EMRE by either protease-resistant mutants of the subunit or m-AAA protease knockout lead to calcium overload in mitochondria and sensitization to MPTP opening (Konig et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2017). The m-AAA protease is also responsible for the maturation of the mitochondrial ribosomal subunit MRPL32, required for mitochondrial ribosome assembly and mitochondrial protein translation (Almajan et al., 2012; Nolden et al., 2005).

Apart from the m-AAA, the soluble AAA+ proteases LON and CLPXP also regulate proteostasis within the mitochondrial matrix. LON is a serine protease with orthologs found in organisms from bacteria to humans (Sauer and Baker, 2011). LON assembles as a homohexamer with each subunit containing both an AAA+ ATPase domain and a protected proteolytic core (Sauer and Baker, 2011). LON has a critical role in regulating mitochondrial matrix proteostasis through the degradation of oxidatively damaged and/or misfolded proteins such as aconitase (Bota and Davies, 2002, 2016; Bota et al., 2002). Furthermore, LON regulates many other aspects of mitochondrial function such as electron transport chain (ETC) activity, steroid synthesis, heme biosynthesis and mitochondrial transcription through the degradation of specific proteins such as the complex IV subunit COX4–1, steroid acute regulatory protein, and 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase, respectively (Fukuda et al., 2007; Granot et al., 2007; Matsushima et al., 2010; Quiros et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2011). LON has also been shown to bind mtDNA in a process linked to the degradation of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) (Liu et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2007). The importance of LON for mitochondrial function is highlighted by the fact that mice lacking Lon are not viable (Quiros et al., 2014).

The CLPXP protease is a heterooligomeric protease composed of two different proteins: the AAA+ ATPase (CLPX) and the serine protease (CLPP). Like LON, the CLPXP protease can function as a general quality control protease in the mitochondrial matrix through the degradation of misfolded or non-native protein conformations. The CLPXP protease has an important role in regulating mammalian mitochondrial proteostasis. Deletion of CLPP in mice leads to increased expression of mitochondrial proteostasis factors and mitochondrial dysfunction, likely reflecting an imbalance in mitochondrial proteome integrity (Deepa et al., 2015; Gispert et al., 2013). Additionally, CLPP is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis through the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) in C. elegans (Haynes et al., 2007), although similar roles for mammalian UPRmt signaling have not been identified (Seiferling et al., 2016). Interestingly, apart from its role in proteolytic degradation, CLPX has been shown to work independent of CLPP in chaperoning the folding of specific proteins such as ALA synthase, indicating that this protein has a non-proteolytic role in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis (Kardon et al., 2015). Thus, while the substrate specificity of CLPXP remains to be established, it is clear that this protease has an important role in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis and function.

Apart from AAA+ ATP-dependent proteases, mitochondrial proteostasis is also regulated by a network of ATP-independent quality control proteases. Unlike the AAA+ proteases, these proteases generally have more specific proteolytic functions associated with aspects of mitochondrial biology such as the regulation of apoptotic signaling and mitochondrial dynamics. The presenilin associated rhomboid like (PARL) protease is an ATP-independent IM protease that can assemble into a proteolytic complex consisting of the AAA+ protease YME1L and the cardiolipin binding protein stomatin-like protein 2 (SLP2) (Wai et al., 2016). This complex regulates PARL-dependent functions including the cleavage of the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) involved in mitophagy (Jin et al., 2010) and the Ser/Thr protein phosphatase phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) linked to mitochondrial dynamics, respiration and cell survival (Sekine et al., 2012). HTRA2 is a highly conserved trimeric serine protease that localizes to the IMS (Clausen et al., 2011). Deletion of HTRA2 leads to accumulation of unfolded mitochondrial proteins suggesting that this protein has an important role in degrading misfolded, non-native, or damaged proteins within the IMS (Moisoi et al., 2009). HTRA2 activity has also been implicated in other mitochondrial functions including mtDNA regulation, mitophagy, and apoptotic signaling (Chao et al., 2008; Cilenti et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2001). Finally, OMA1 is a stress-activated ATP-independent IM zinc metalloprotease with an active site oriented to the IMS (Baker et al., 2014; Kaser et al., 2003). OMA1 is normally maintained in a quiescent state that suppresses its protease activity (Anand et al., 2014; Head et al., 2009; Rainbolt et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). In response to specific insults that induce membrane depolarization such as oxidative stress, the OMA1 protease is activated resulting in the regulated processing of the dynamin like GTPase OPA1 involved in dictating mitochondrial morphology during stress (discussed in detail below).

Oligopeptidases degrade polypeptides within mitochondria

Processing peptidases and quality control proteases both generate peptide fragments within mitochondria. The build-up of these peptides could disrupt mitochondrial proteostasis through mechanisms such as the feedback inhibition of mitochondrial proteases or binding to mitochondrial chaperones. Interestingly, mitochondrial derived peptides can also be effluxed from mitochondria and serve as stress signals involved in the activation of stress-responsive signaling pathways (Arnold et al., 2006; Haynes et al., 2010; Young et al., 2001). Thus, controlling the levels of mitochondrial peptides is an important parameter in dictating mitochondrial proteostasis. This is primarily achieved by the activity of mitochondrial-localized oligopeptidases.

The most prominent mitochondrial oligopeptidase in the mitochondrial matrix is the metalloprotease PITRM1, also known as PreP. PreP degrades N-terminal targeting sequences produced by MPP-dependent processing of precursor proteins (Alikhani et al., 2011a; Chow et al., 2009; Stahl et al., 2002). This degradation is important to prevent feedback inhibition of MPP, which can lead to mitochondrial proteotoxic stress through the accumulation of precursor proteins within the matrix. PreP has also been implicated in the degradation of mitochondrial-localized amyloid β peptides associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Brunetti et al., 2015; Falkevall et al., 2006; Mossmann et al., 2014), indicating that this peptidase has a more global role in regulating peptide levels within mitochondria. PreP has also been suggested to facilitate the maturation of frataxin, a protein involved in iron-sulfur biogenesis within mitochondria (Nabhan et al., 2015). Other peptidases including neurolysin (also known as oligopeptidase M or MEP) also function to degrade peptides within the IMS (Chow et al., 2009; Serizawa et al., 1995). These peptidases serve critical roles in regulating the levels of peptides localized to the matrix and IMS, preventing imbalances in mitochondrial proteostasis and stress-signaling.

Mitochondrial proteases are key regulators of organellar quality control

Mitochondria are structurally heterogeneous organelles that demonstrate distinct morphologies in different mammalian tissues (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016). Furthermore, mitochondrial morphology is dynamically regulated to adapt mitochondrial function in response to environmental or metabolic challenges. These different morphologies can be accessed through the regulation of biologic pathways involved mitochondrial fusion and fission. The capacity to adapt mitochondrial morphology through alterations in the relative activities of mitochondrial fusion and fission processes provides a unique opportunity to match mitochondrial function to tissue-specific or environmental challenges. For example, elongated mitochondria, which result from increased fusion or decreased fission, are associated with enhanced ETC activity and desensitization to apoptotic insult (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016). However, fragmented mitochondria, which result from increased fission or decreased fusion, show reduced ETC activity and are sensitized to stress-induced apoptosis (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016), but can promote mitochondrial proteostasis through the sequestration and degradation of damaged mitochondria by mitophagy (Youle and Narendra, 2011). Thus, the capacity to dynamically regulate mitochondrial morphology provides another level of quality control that cells utilize to sensitively regulate both mitochondrial proteostasis and function.

Mitochondrial dynamics are regulated by the activities of dynamin-like GTPases localized to the OM and IM (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; van der Bliek et al., 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016). Mitochondrial fission is largely dictated by the dynamin-like GTPase dynamin related protein 1 (DRP1). DRP1 is mainly located in the cytosol under basal condition and is recruited to the mitochondrial OM by receptors such as mitochondrial fission factor (MFF) and FIS1 for the fission process (Loson et al., 2013). This recruitment facilitates DRP1 oligomerization into ring structures that promote mitochondrial fission through the constriction of the outer membrane. Conversely, mitochondrial fusion is regulated by the outer membrane GTPases mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2) and the inner membrane GTPase OPA1. In this process, mitofusins form complexes through homo- or heterotypic interactions that drive OM fusion through a GTP-dependent process. Long isoforms of OPA1 (l-OPA1) similarly utilize GTP to drive IM fusion events. Not surprisingly, the activities of these GTPases are highly regulated through a variety of posttranslational mechanisms including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and proteolytic processing, providing a mechanism to sensitively regulate mitochondrial morphology in response to specific cues (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; van der Bliek et al., 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016). Here, we specifically focus on the role of mitochondrial proteases in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. For a more comprehensive review of other posttranslational mechanisms involved in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics see (Chan, 2012; Shutt and McBride, 2013; van der Bliek et al., 2013; Wai and Langer, 2016).

Mitochondrial morphology is regulated by the activity of mitochondrial proteases

Mitochondrial fusion/fission factors localized to the OM are regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS). E3 ubiquitin ligases such as PARKIN and MARCH5 reside on the OM and can ubiquitinate OM membrane proteins (Covill-Cooke et al., 2017). Interestingly, ubiquitination of MFN1/2 by one or both of these E3 ligases leads to the degradation of these OM fusion factors (Park and Cho, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2010). UPS-dependent degradation of MFN1/2 attenuates mitochondrial fusion and in turn promotes mitochondrial fission (Yue et al., 2014). Interestingly, the OM deubiquitinase USP15 and USP30 suppress MFN1/2 ubiquitination, inhibiting proteasomal degradation and thus promoting mitochondrial fusion (Cunningham et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2015; Yue et al., 2014). Thus, the relative activities of PARKIN and MARCH5 vs. USP15/30 regulates MFN1/2 stability, directly influencing mitochondrial morphology. DRP1 can also be ubiquitinated by MARCH5, although this modification does not appear to be associated with DRP1 degradation, but instead could be involved in promoting DRP1-dependent fission (Karbowski et al., 2007; Nakamura et al., 2006).

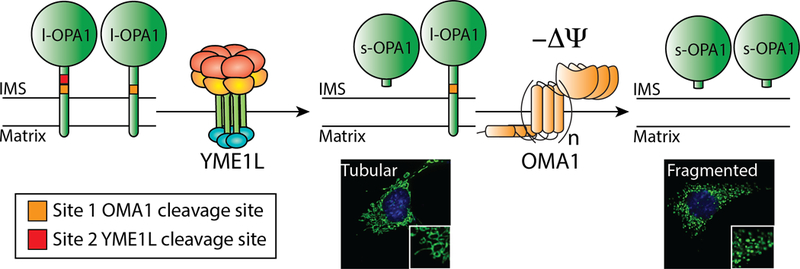

By contrast, the predominant IM dynamin like GTPase OPA1 is not accessible to the UPS. Instead, OPA1 is regulated through a highly coordinated mechanism involving the IM proteases YME1L and OMA1 (Fig. 3). OPA1 is expressed as 8 distinct mRNA transcripts that predominantly differ in the presence or absence of the S5b exon (Ishihara et al., 2006; Song et al., 2007). All of these transcripts contain an OMA1 proteolytic cleavage site referred to as Site 1. However, only a population of these transcripts contains the Site 2 cleavage site encoded by the S5b exon, which is selectively cleaved by YME1L. OPA1 exists as long (l-OPA1) and short (s-OPA1) isoforms that distinctly influence mitochondrial fusion and fission (Anand et al., 2014; Ishihara et al., 2006). l-OPA1 isoforms are full-length, membrane integrated OPA1 proteins that are generally associated with mitochondrial fusion. YME1L and OMA1 differentially cleave l-OPA1 isoforms to produce s-OPA1 (Anand et al., 2014). YME1L constitutively cleaves the subset of l-OPA1 containing the Site 2 cleavage site to produce a distinct isoform of s-OPA1. This YME1L-dependent OPA1 processing is important for establishing the distribution of l-OPA1 and s-OPA1 involved in promoting and maintaining tubular mitochondrial morphology (Anand et al., 2014; Griparic et al., 2007; Mishra et al., 2014; Song et al., 2007). Alternatively, the stress-activated OMA1 protease cleaves all l-OPA1 isoforms at the Site 1 cleavage site to produce s-OPA1 isoforms, which promotes mitochondrial fragmentation (Anand et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2014; Song et al., 2007). The recovery of tubular mitochondrial morphology from this fragmented state requires the suppression of OMA1 protease activity and de novo synthesis of l-OPA1 (Anand et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2014; Rainbolt et al., 2016; Song et al., 2007). As such, the balance of YME1L and OMA1-dependent OPA1 processing is a key determinant in dictating mitochondrial morphology, and thus mitochondrial function, in response to acute insults (discussed in detail below).

Figure 3.

Illustration showing the functional role for YME1L and OMA1 in regulating mitochondrial morphology through the regulated processing of the inner membrane GTPAse OPA1. YME1L constitutively cleaves a subset of OPA1 containing the Site 2 YME1L cleavage site to establish a distribution of long-OPA1 (l-OPA1) and short-OPA1 (s-OPA1) required for maintaining mitochondrial tubular morphology. Upon depolarization of mitochondria, OMA1 is activated resulting in the cleavage of all OPA1 at the Site 1 OMA1 cleavage site. This OMA1-dependent processing of OPA1 to s-OPA1 promoting mitochondrial fragmentation.

Proteolytic control of mitophagy

The regulation of mitochondrial dynamics also facilitates the degradation of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy. In this process, mitochondria are sequestered in autophagosomes that are then directed to the lysosome for degradation. Mitophagy can function to non-selectively degrade mitochondria in response to stress insults such as starvation that induce a global cellular autophagic response (Youle and Narendra, 2011). However, mitophagy also provides a mechanism to selectively remove damaged mitochondria in response to stresses such as mitochondrial depolarization or the accumulation of misfolded mitochondrial proteins. The ability to selectively degrade damaged mitochondria allows cells to maintain the global integrity of the mitochondrial population, preventing potential imbalances in mitochondrial function that could challenge cellular viability.

The mitochondrial proteolytic network has a central role in regulating mitophagy of damaged mitochondria in response to stress. Damaged mitochondria are predominantly identified through a mechanism involving PINK1 and the E3 ligase PARKIN (Matsuda et al., 2010). Under normal conditions, PINK1 is imported into mitochondria and incorporated into the IM as a transmembrane protein. In the IM, PINK1 is processed by MPP and then cleaved by the mitochondrial protease PARL, releasing PINK1 to the cytosol where it can be degraded by the proteasome (Greene et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2014). PINK1 degradation can also be regulated by other mitochondrial proteases including AFG3L2 and LON (Greene et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2014). This degradation of PINK1 functions to suppress its activity on the mitochondrial OM (Yamano and Youle, 2013). Conversely, mitochondrial insults that induce depolarization impair PINK1 import into the mitochondrial IM, inhibiting its degradation and facilitating PINK1 incorporation into the OM (Okatsu et al., 2013). Localization of PINK1 to the OM recruits the E3 ligase PARKIN to mitochondria, which promotes fragmentation through the ubiquitination of MFN1/2 and degradation of other OM proteins through the UPS (Chan et al., 2011; Ziviani et al., 2010). PARKIN recruitment and subsequent ubiquitination of OM proteins facilitates formation of the autophagasome required for lysosomal-dependent degradation of mitochondria through autophagy (Harper et al., 2018; Koyano et al., 2014; Okatsu et al., 2015; Okatsu et al., 2013). Apart from the PINK1/PARKIN pathway, mitophagy can be initiated through other mechanisms in involving mitochondrial receptors such as NIX, BNIP3 and FUNDC1 that interact with the microtubule associated protein LC3 directly to induce autophagasome formation (Hamacher-Brady and Brady, 2016; Novak and Dikic, 2011; Novak et al., 2010; Sandoval et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014).

Mitochondrial proteases link mitochondrial proteostasis to apoptotic signaling

Mitochondrial integrity is a key regulator of intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathways. In this process, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) leads to the release of pro-apoptotic factors including cytochrome c, Smac, and AIF from mitochondria to the cytosol. The release of these factors induces assembly of the apoptosome allowing the activation of initiator and executioner caspases that mediate the apoptotic program (Tait and Green, 2013). MOMP is regulated by the relative activities of several pro-apoptotic (e.g., Bad, Bax, Bak) and pro-survival (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl) Bcl-2 family members located on the OM. Many factors can influence intrinsic apoptotic signaling through the expression of Bcl-2 family members or altering the activity of downstream signaling mechanisms (Gillies and Kuwana, 2014). However, it is clear that mitochondrial proteases are contributors to the activation and regulation of apoptosis induced by intrinsic signals.

The IMS quality control serine protease HTRA2 has been implicated in diverse regulatory roles involved in apoptotic signaling. HTRA2 is expressed as a transmembrane protein that can be activated through proteolytic processing by PARL and/or an autocatalytic mechanism (Chao et al., 2008; Seong et al., 2004). The release of activated HTRA2 to the cytosol promotes apoptosis through the degradation of anti-apoptotic factors such as X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (Hegde et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2001). However, PARL-dependent HTRA2 activation has been proposed to suppress accumulation of pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins on the OM, suggesting an anti-apoptotic role for HTRA2 (Chao et al., 2008). These results highlight that HTRA2 appears to be mitochondrial protease that is a key regulator of apoptotic signaling pathways.

Apoptotic signaling also involves both mitochondrial fragmentation and disruption of cristae, which is thought to facilitate the release of cytochrome c during apoptosis (Cipolat et al., 2006; Frezza et al., 2006; Varanita et al., 2015). This suggests that mitochondrial proteases such as YME1L and OMA1 involved in regulating mitochondrial morphology through OPA1 processing could influence apoptotic signaling because OPA1 maintains cristae organization (Olichon et al., 2003). OMA1 deletion inhibits stress-induced OPA1 processing required for mitochondrial fragmentation and disruption of cristae integrity necessary for cytochrome c release (Anand et al., 2014; Head et al., 2009; Olichon et al., 2003). As such, OMA1-deficient cells show a reduced sensitivity to apoptotic insult (Anand et al., 2014; Head et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2014). Alternatively, YME1L-deficient cells show increased mitochondrial fragmentation and disrupted cristae morphology, resulting in increased sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli (Anand et al., 2014; Rainbolt et al., 2015; Stiburek et al., 2012). Interestingly, OMA1 deletion in YME1L-deficient cells rescues these phenotypes, indicating that the increased sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli in YME1L-deficient cells largely results from imbalances in OPA1 processing (Anand et al., 2014). PARL has also been implicated in the regulation of apoptotic signaling through OPA1 processing (Pellegrini and Scorrano, 2007) and other mechanisms involved in regulating cristae morphology and cytochrome c release (Cipolat et al., 2006; Frezza et al., 2006). In addition, PARL processes the pro-apoptotic SMAC/Diablo to release this pro-apoptotic factor to the cytosol (Saita et al., 2017).

Other mitochondrial proteases have also been implicated in the regulation of apoptotic signaling, although direct roles for these proteases in the regulation of apoptotic signaling mechanisms remain to be established. LON has been suggested to influence apoptosis through its association with the mitochondrial chaperones HSP60 and mtHSP70 (HSPA9), however the dependence of apoptosis on LON protease activity is currently undefined (Kao et al., 2015). YME1L can also influence apoptotic signaling through the degradation of PRELID1, which is involved in cardiolipin synthesis and subsequently cytochrome c release (Potting et al., 2013). While the specific contributions for these other proteases in intrinsic apoptotic signaling induced by specific stresses remains to be further defined, it is clear that the maintenance of mitochondrial proteolytic systems is important to regulate apoptotic signaling pathways in response to diverse pathologic insults.

Stress-Responsive Regulation of the Mitochondrial Proteolytic Network

Mitochondrial proteostasis and function are challenged by diverse insults including environmental toxins, metabolic stress and aging. All of these insults can increase the accumulation of misfolded or aggregated proteins within mitochondria and lead to the pathologic disruption of mitochondrial function. To protect mitochondria in response to these insults, cells evolved a network of stress-responsive signaling mechanisms that regulate the composition and activity of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways. Mitochondrial proteases and their activities are key determinants in this stress-responsive regulation. The capacity to influence mitochondrial proteostasis, organellar morphology, and apoptotic signaling through the regulation of proteolytic activity provides a mechanism to adapt mitochondrial function to the cellular or metabolic demands imposed by a specific type of stress or insult (Quiros et al., 2015; Shpilka and Haynes, 2018). Here, we describe the transcriptional and translational stress-responsive signaling mechanisms by which cells adapt mitochondrial proteostasis and function to specific cell stresses.

Mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt)-dependent regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis

The preeminent stress-responsive signaling pathway responsible for regulating mitochondrial proteostasis is the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) (Shpilka and Haynes, 2018). The UPRmt is activated in response to imbalances in mitochondrial matrix proteostasis (e.g., the accumulation of misfolded or unassembled mitochondrial proteins). Many different types of cellular insults can activate the UPRmt in eukaryotes including deletion of mitochondrial quality control proteases (Benedetti et al., 2006; Yoneda et al., 2004), overexpression of a misfolding prone mitochondrial matrix protein (e.g. ΔOTC) (Aldridge et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2002), inhibition of mitochondrial translation (Houtkooper et al., 2013), and alterations in mitochondrial co-factor levels (Baker et al., 2012a; Durieux et al., 2011). Activation of the UPRmt functions to adapt mitochondrial proteostasis through the transcriptional upregulation of mitochondrial proteostasis factors involved in protein import, folding and proteolysis. Through this upregulation, stress-induced imbalances in mitochondrial proteostasis are alleviated and mitochondrial function is adapted to match demands associated with the specific insult.

The signaling mechanism of the UPRmt has predominantly been defined in C. elegans, where it has been shown that mitochondrial proteases play a key role in regulating UPRmt signaling. The worm UPRmt can be activated by several genetic manipulations that increase protein misfolding within the mitochondrial matrix (e.g., RNAi-depletion of the m-AAA subunit spg-7) (Benedetti et al., 2006). This increase in protein misfolding is initially detected through the increased degradation of mitochondrial proteins by the CLPXP quality control protease (Haynes et al., 2007). Peptides derived from the CLPXP-dependent proteolysis are exported across the IM to the IMS through the HAF-1 ABC peptide transporter (Haynes et al., 2010). In the IMS, these peptides function to dictate the localization of the UPRmt-associated transcription factor ATFS-1. In the absence of stress, ATFS-1 is targeted to mitochondria by an N-terminal targeting sequence and imported across the OM and IM into the mitochondrial matrix (Nargund et al., 2012). In the matrix, ATFS-1 is degraded by the LON protease, suppressing its transcriptional activity. However, the increased efflux of peptides through HAF-1 induced by mitochondrial stress attenuate ATFS-1 import into mitochondria through an undefined mechanism (Nargund et al., 2012). This reduced import of ATFS-1 allows this transcription factor to be targeted to the nucleus by a nuclear localization sequence located on the C-terminus of the ATFS-1 protein. In the nucleus, ATFS-1 coordinates with other nuclear transcriptional regulators such as DVE-1 and UBL-5 to induce expression of UPRmt target genes, which includes many mitochondrial proteases (Benedetti et al., 2006; Haynes et al., 2007; Nargund et al., 2012).

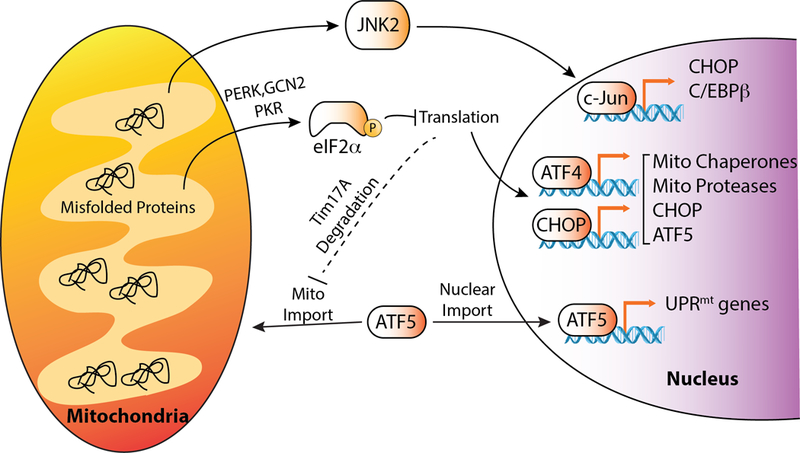

Mammals also possess a UPRmt, although the signaling mechanism(s) responsible for the mammalian UPRmt remains less well defined (Fig. 4). The mammalian UPRmt is activated by stress-insults that disrupt proteostasis within mitochondria such as overexpression of misfolding-prone proteins (Aldridge et al., 2007; Horibe and Hoogenraad, 2007; Zhao et al., 2002), inhibition of mitochondrial translation (Houtkooper et al., 2013), and the modulation of NAD+ levels (Mouchiroud et al., 2013). Interestingly, signaling through the mammalian UPRmt appears to be different than that observed in C. elegans. Recently, the mammalian homolog of ATFS-1, ATF5, was identified and shown to be regulated through mechanism similar to that shown for ATFS-1 and involving stress-dependent localization between mitochondria and the nucleus (Fiorese et al., 2016). However, the potential dependence of this regulated import on peptide-efflux through a HAF-1-dependent channel has not been defined. Furthermore, CLPP is not required for activating the UPRmt in the mammalian heart, suggesting that mammalian UPRmt signaling proceeds through a CLPP-independent mechanism at least in this tissue (Seiferling et al., 2016).

Figure 4.

Illustration showing the mechanism(s) predicted to be involved in mammalian UPRmt signaling. In the absence of stress, ATF5 transcriptional activity is suppressed through its targeting to the mitochondrial matrix. In response to proteotoxic stress within mitochondria, ATF5 import is attenuated, allowing its localization to the nucleus and subsequent activation of UPRmt-associated genes. Mitochondrial proteotoxic stress can potentially influence UPRmt signaling through multiple other mechanisms including activation of JNK2 and eIF2α phosphorylation, as discussed in the text.

In contrast, mammalian UPRmt signaling has been proposed to involve many other stress-responsive signaling mechanisms. The JNK2 signaling cascade can be activated by mitochondrial stress and lead to downstream activation of the transcription factor c-Jun (Horibe and Hoogenraad, 2007). c-Jun in turn binds to the AP-1 sites in the promoters of the stress-responsive transcription factors C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and C/EBPβ inducing their expression (Horibe and Hoogenraad, 2007)(Fig. 4). These transcription factors form homo- and/or hetero-dimers that bind to CHOP elements found in the promoters of many mitochondrial proteostasis genes (Zhao et al., 2002). However, it is unlikely that these transcription factors function alone to induce mammalian UPRmt signaling, as they are activated in response to many different types of stress (see below), making it difficult to convey selectivity of a UPRmt transcriptional response. Consistent with this, identification of mitochondrial UPR elements (MUREs), which are not bound by CHOP, in the promoter region of mitochondrial proteostasis genes suggests other transcriptional regulators are involved in dictating the selectivity associated with UPRmt activation (Aldridge et al., 2007). Interestingly, CHOP and other stress-responsive transcription factors (e.g., ATF4) can induce ATF5 in response to other types of proteotoxic stress (Fusakio et al., 2016; Kilberg et al., 2012; Teske et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2008), suggesting that an ATF5-selective UPRmt transcriptional response could be regulated downstream of these other stress-responsive transcription factor. However, this transcriptional relationship remains to be established. Other pathways including the AKT signaling pathway and estrogen receptor signaling are activated through a ROS-mediated mechanism in response to proteotoxic insults localized to the IMS in a process referred to the IMS UPRmt (Papa and Germain, 2011). This suggests that different signaling mechanisms may be utilized to adapt mammalian mitochondrial proteostasis to specific types of proteotoxic insults that challenge distinct mitochondrial subcompartments.

The lack of specific signaling factors involved in the mammalian UPRmt has challenged the ability to explicitly define the transcriptional program induced by this stress-responsive pathway. However, the transcriptional response for the worm UPRmt has been defined by identifying genes regulated by the UPRmt transcription factor ATFS-1 (Nargund et al., 2012). This analysis showed that the worm UPRmt sensitively adapts the composition and activity of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways through the selective upregulation of specific import factors (e.g., Tim-17 and Tim-23), chaperones (e.g., HSP-60) and proteases (e.g., YME-1) (Nargund et al., 2012). However, key mitochondrial proteostasis factors such as LON and CLPP were not induced by ATFS-1 in response to mitochondrial stress. This selective remodeling of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways may provide a mechanism to support adaption of mitochondrial function in response to mitochondrial proteotoxic stress. For example, ATFS-1 also regulates expression of glycolytic genes suggesting that UPRmt activation promotes a metabolic shift for ATP production from respiration to glycolysis (Nargund et al., 2012). ATFS-1 also induces expression of transcriptional programs involved in ROS detoxification and innate immunity (Nargund et al., 2012). Selective adaptation of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways could provide a mechanism to facilitate alterations in mitochondrial functions to support the increased activities of these other programs. For example, the upregulation of YME-1 could increase YME-1-dependent degradation of damaged or unassembled respiratory chain subunits, preventing the accumulation of ROS-damaged ETC subunits and promoting an energetic shift to glycolysis.

It is currently unclear whether the mammalian UPRmt also induces selective remodeling of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways. Initial experiments using a transcriptional reporter approach where mitochondrial stress was induced by overexpression of a misfolding-prone matrix protein showed that selective mitochondrial proteostasis factors including the import subunit Tim17A, the mitochondrial chaperone HSP60 and the mitochondrial proteases MPP, YME1L, AFG3L2 and CLPP were induced by the UPRmt, while other proteostasis factors such as mitochondrial HSP70 and LON were not (Aldridge et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2002). However, more recent studies using qPCR show that mtHSP70 and LON are both induced by UPRmt-activating insults in mammalian cells (Fiorese et al., 2016). These results suggest that, unlike the worm UPRmt, mammalian UPRmt signaling may not promote the same type of selective remodeling of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways. However, more experiments are required to further define the scope of mitochondrial proteostasis remodeling induced by the mammalian UPRmt.

While it is becoming increasing clear that the UPRmt is involved in regulating many aspects of mitochondria and organismal health (e.g., energy metabolism, longevity, and innate immunity), the functional importance of UPRmt-dependent adaptation of mitochondrial proteostasis pathways for mitochondrial function remain to be established. In mammals, establishing this type of relationship is hindered by our poor understanding of the signaling mechanism(s) involved in the mammalian UPRmt activation. As new, specific components of this pathway are found, the transcriptional profile of the mammalian UPRmt can be better established, revealing the scope of the transcriptional program involved in regulating mitochondrial and global cellular physiology in response to mitochondrial proteotoxic insults. This will in turn provide new opportunities to define the specific role of UPRmt-dependent proteostasis adaptation in adapting mitochondrial function to environmental or metabolic demands induced by a specific stress insult.

The Integrated Stress Response (ISR) coordinates mitochondrial proteostasis in response to diverse insults

Apart from the UPRmt, the Integrated Stress Response (ISR) has also been identified as a key stress-responsive signaling mechanism responsible for regulating mitochondrial proteostasis and function (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016; Quiros et al., 2016). The ISR is a multifaceted stress responsive signaling pathway regulated by a network of stress-responsive kinases including protein kinase R (PKR), general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI), and the PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) (Fig. 5) (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016). These kinases are activated in response to diverse cellular insults including viral infection, amino acid deprivation, oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Upon activation, these kinases phosphorylate the S51 residue of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2α subunit (eIF2α). Phosphorylation of eIF2α inhibits the activity of the eIF2B GTP exchange factor involved in translation initiation, resulting in a transient attenuation in new protein synthesis. This attenuation in synthesis functions to promote global cellular proteostasis by reducing the load of newly-synthesized proteins, freeing proteostasis factors to prevent pathologic disruptions in cellular proteome integrity.

Figure 5.

Illustration showing the signaling mechanisms associated with the integrated stress response. Four different kinases activated by distinct insults initiate ISR signaling through the phosphorylation of eIF2α. This leads to both translation attenuation and activation of ISR-associated transcription factors such as ATF4.

Apart from reducing translation, eIF2α phosphorylation also activates stress-responsive transcription factors such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016; Quiros et al., 2016; Young and Wek, 2016). ATF4 is selectively translated in response to eIF2α phosphorylation through a mechanism involving upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in its 5’ UTR (Young and Wek, 2016). In response to stresses that increase eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 is translated allowing ATF4-dependent expression of cellular proteostasis factors involved in redox homeostasis, amino acid biosynthesis, and ER proteostasis maintenance (Han et al., 2013; Harding et al., 2003). ATF4 also induces the expression of additional stress-responsive transcription factors such as CHOP – the same transcription factor involved in UPRmt signaling (Harding et al., 2000). As part of the ISR, CHOP induces expression of additional proteostasis factors including GADD34 – a regulatory phosphatase subunit that interacts with protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) to dephosphorylate eIF2α in an ISR negative feedback pathway that restores translational integrity following acute insult (Ma and Hendershot, 2003; Novoa et al., 2001). CHOP activation also promotes pro-apoptotic signaling in response to severe or sustained toxic insults through complex mechanisms involving the expression of pro-apoptotic factors and/or increasing cellular oxidative stress (Han et al., 2013; Hetz and Papa, 2018; Sano and Reed, 2013). Thus, ISR-dependent activation of stress-responsive transcription factors such a CHOP and ATF4 serve a critical role in dictating both pro-survival adaptation of cellular proteostasis and activation of pro-apoptotic signaling pathways in response to varying types and extents of cellular stress.

Mitochondrial stress has been shown to activate the ISR through multiple mechanisms. In C. elegans, mitochondrial stress induced by RNAi-depletion of the m-AAA subunit spg-7 leads to increased activation of the ISR kinase GCN2 (Baker et al., 2012a). The activation of the ISR in response to this stress is predicted to function in a parallel mechanism to the UPRmt to regulate mitochondrial proteostasis and function in response to mitochondrial proteotoxic insults. Similarly, mitochondrial stress in mammals activates eIF2α kinases such as GCN2, PKR, or HRI (Martinez-Reyes et al., 2012; Michel et al., 2015; Rath et al., 2012; Viader et al., 2013), indicating mitochondrial dysfunction can activate multiple ISR kinases in metazoans. Not surprisingly considering the link between mitochondrial stress and the ISR, ATF4 is also activated in response to diverse mitochondrial insults including membrane depolarization, disruption of protein import, imbalances in OXPHOS protein stability and inhibition of mitochondrial translation in an eIF2α phosphorylation-dependent manner (Quiros et al., 2017). Interestingly, knocking down individually the different ISR kinases failed to inhibit ATF4 activation under these conditions, likely reflecting the capacity for mitochondrial stress to signal through multiple eIF2α kinases. CHOP activity is also activated in response to mitochondrial stress through an ISR-associated mechanism (Michel et al., 2015).

The above results suggest that the ISR has an important role in regulating mitochondrial proteostasis and function in response to diverse pathologic insults that activate ISR-associated kinases. Consistent with this, ISR activation transcriptionally regulates many aspects of mitochondrial proteostasis factors. The PERK-dependent activation of ATF4 and CHOP in response to ER stress, a condition induced by accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER lumen, increases expression of mitochondrial chaperones (e.g., mtHSP70) and the quality control protease LON (Han et al., 2013; Harding et al., 2003; Hori et al., 2002; Lebeau et al., 2018). The increased expression of LON could reflects a mechanism to increase mitochondrial proteostastic capacity to degrade misfolded, non-native, or oxidatively damaged mitochondrial proteins that accumulate in response to this insult. Many insults that activate the ISR lead to increased production of ROS that could damage mitochondrial proteome. LON preferentially degrades oxidatively modified proteins (Bota and Davies, 2002), suggesting that its increased expression could serve to prevent the potentially toxic accumulation of damaged proteins during these stresses. Consistent with this, overexpression of LON protects cells from mitochondrial dysfunction induced by ER stress – a potent activator of the ISR kinase PERK (Hori et al., 2002). However, overexpression of a proteolytically inactive LON can also alleviate ER stress induced mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting LON could also promote mitochondrial function through non-degradative mechanisms in response to ER stress (Hori et al., 2002).

The yeast mtHSP70 has been shown to cooperate with the yeast LON homolog PIM1 to degrade misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix (Savel’ev et al., 1998; Wagner et al., 1994). This suggests that the coordinated regulation of LON and mtHSP70 by the ISR may provide a mechanism to selectively facilitate LON-dependent degradation of damaged mitochondrial proteins through mechanisms such as preventing stress-induced aggregation of misfolded proteins and/or altering the substrate specificity of LON (Bender et al., 2011; Savel’ev et al., 1998; Wagner et al., 1994). Interestingly, the subset of mitochondrial stress-genes regulated by ATF4 during mitochondrial stress is predicted to be distinct from those regulated by the UPRmt (Quiros et al., 2017). This suggests that the ISR and UPRmt could serve as complementary mechanisms to regulate mitochondria in response to stress, mirroring the relationship between these pathways observed in worm. However, the shared involvement of many ISR and UPRmt signaling factors including ATF4, CHOP, and ATF5, suggests that these two pathways could also be highly integrated to regulate mitochondria in response to distinct types of proteotoxic insults (Fig. 4). Thus, further experiments are necessary to define the transcriptional relationship between ISR and UPRmt signaling in mammals.

Apart from transcriptional signaling, translational attenuation induced by the ISR also leads to remodeling of mitochondrial protein import pathways through the selective degradation of the core TIM23 subunit Tim17A. In mammals, the IM TIM23 protein import complex exists in two distinct subunit compositions defined by the presence of a Tim17A or Tim17B subunit. Currently, functional differences between these two Tim17 homologs are poorly defined, although some experiments suggest that they differ in their ability to import non-traditional mitochondrial substrates (Sinha et al., 2014). In response to ISR-dependent translational attenuation, Tim17A, but not Tim17B, is rapidly degraded by the YME1L quality control protease (Rainbolt et al., 2013). YME1L-dependent Tim17A degradation decreases the population of import competent TIM23 complexes and thus reduces mitochondrial protein import into the matrix. Interestingly, depletion of Tim17A increases stress-resistance to diverse types of stresses such as As(III) and paraquat, indicating that ISR-dependent Tim17A degradation is a protective mechanism to suppress import during acute insult (Rainbolt et al., 2013). This protection could be afforded by reducing the population of newly-imported proteins entering mitochondria, which decreases the folding load in the mitochondrial matrix and frees mitochondrial chaperones and proteases to protect the conformational integrity of the established mitochondrial proteome. Alternatively, Tim17A degradation could function as a mechanism to regulate the import of specific stress-responsive transcription factors such as ATF5, facilitating their activation (Fig. 4). While RNAi-depletion of the Tim17A homolog tim-17 in C. elegans does activate the UPRmt (Rainbolt et al., 2013), further experiments are necessary to confirm this potential relationship in mammalian cells. Interestingly, the posttranslational regulation of Tim17A induced downstream of ISR-regulated translational attenuation suggests that the stability of other mitochondrial proteins could similarly be regulated through this mechanism, although other examples have not yet been identified to date.

Consistent with the above, translational attenuation induced by ER stress-dependent activation of the ISR kinase PERK also influences mitochondrial morphology during ER stress. PERK-regulated translational attenuation promotes Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Hyperfusion (SIMH) (Tondera et al., 2009) in response to ER stress through a mechanism requiring the cardiolipin binding protein SLP2 (Lebeau et al., 2018). ER stress-induced SIMH is attenuated in cells deficient in the inner membrane protease YME1L, indicating that this protease regulates both SIMH and TIM17A degradation in response to PERK-regulated translational attenuation. These results show that the PERK-YME1L signaling axis is a critical stress-signaling mechanism responsible for regulating mitochondria in response to ER stress. While the mechanism and functional implications of PERK-regulated SIMH remains to be fully established, SLP2-dependent elongation appears to protect mitochondrial metabolic capacity and prevent premature fragmentation in response to acute ER stress (Lebeau et al., 2018). Although it is currently unclear whether other ISR-activating insults similarly promote SIMH downstream of eIF2α-phosphorylation-dependent translation attenuation, these results show that PERK-dependent ISR activation integrates transcriptional and translational signaling to coordinate mitochondrial proteostasis and morphology, revealing a global role for this pathway in regulating mitochondria in response to ER insults (Lebeau et al., 2018; Rainbolt et al., 2014).

The above results show that ISR signaling is a key determinant in dictating protective remodeling of mitochondrial proteostasis and function in response to acute cellular insults. However, critical questions remain about the specific role for the ISR in regulating mitochondria. For example, what is the functional interplay between the mammalian ISR and UPRmt? Do other stress pathways integrate their signaling to modulate ISR-dependent regulation of mitochondria in response to distinct insults? What biochemical pathways are dependent on ISR-dependent regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis? As we and others continue to define the impact of ISR activation on mitochondria, these (and other) questions will be answered, further revealing ISR signaling as a core stress-responsive signaling pathway important for regulating mitochondria.

LON is also transcriptionally regulated by other stress-responsive signaling pathways

Apart from the ISR and UPRmt, the mitochondrial protease LON is also transcriptionally regulated by other stress-responsive signaling pathways (Bota and Davies, 2016). For example, hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) induces LON expression in response to hypoxic conditions (Fukuda et al., 2007). HIF-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor comprised of HIF-1α and HIF-1β subunits. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1 is targeted for proteasomal degradation through a mechanism involving the hydroxylation and ubiquitination of HIF-1α. Reductions in cellular oxygen levels inhibit HIF-1α hydroxylation, stabilizing this protein and facilitating its nuclear localization. In the nucleus, HIF-1α interacts with HIF-1β to form the active HIF-1 transcription factor. Activated HIF-1 binds to hypoxia related elements (HREs) in the promoters of genes involved in the regulation of oxygen homeostasis including angiogenesis factors and metabolic genes. LON also contains HREs in its promoter, allowing it to be efficiently induced by HIF-1 activation (Fukuda et al., 2007).

HIF-1-dependent expression of LON promotes mitochondrial proteostasis and function in response to hypoxic injury by suppressing the potentially toxic accumulation of oxidatively-damaged mitochondrial proteins that can accumulate under these conditions (Bota and Davies, 2002; Bota et al., 2002). Interestingly, HIF-1-dependent increases in LON may also be involved in the functional adaptation of complex IV during hypoxia. In response to reductions in oxygen, the complex IV subunit COXIV-1 is degraded and replaced by the stress-resistant COXIV-2 subunit, another HIF-1 transcriptional target (Fukuda et al., 2007). COXIV-2 is more efficient at electron transfer in hypoxic cells, allowing improved respiratory chain activity under these conditions. LON may facilitate this process through mechanisms such as the degradation of COXIV-1 or incorporation of COXIV-2 into complex IV, although a specific role for LON in this process remains to be established.

LON is also transcriptionally regulated by the nuclear respiratory transcription factor 2 (NRF-2) (Bahat et al., 2015; Pinti et al., 2011). NRF-2 is a stress responsive transcription factor responsible for regulating the expression of many antioxidant and proteostasis factors following acute oxidative stress. In the absence of stress, NRF-2 activity is repressed by the activity of the KEAP E3 ligase, which ubiquitinates NRF-2 and directs this protein to proteasomal degradation. Oxidative stress impairs KEAP-dependent ubiquitination of NRF-2 allowing nuclear localization and transcriptional activity. The LON gene contains two NRF-2 binding elements in its promoter region (Bahat et al., 2015; Pinti et al., 2011), suggesting that NRF-2 can regulate LON expression. NRF-2 dependent induction of LON has been shown in cell models overexpressing the mitochondrial matrix protein StAR (Granot et al., 2007). In response to the accumulation of StAR within mitochondria, cells initiate a stress-response, referred to as the StAR overload response (SOR), which activates NRF-2 signaling and increases LON expression through an unknown mechanism (Bahat et al., 2015). Interestingly, the increased expression of LON through the SOR likely reflects the need for increased cellular capacity to degrade mitochondrial StAR, which has been shown to be a LON substrate. Similarly, SOR transcriptionally induces other mitochondrial proteases involved in StAR degradation including YME1L, SPG7 and AFG3L2 (Bahat et al., 2015; Bahat et al., 2014), although the specific requirement for NRF-2 in the induction of these other proteases remains to be defined. NRF-2 activation has also been proposed to be induced downstream of the ISR kinases such as PERK (Cullinan et al., 2003), suggesting that NRF-2 could also influence LON expression during ISR-activating insults.

The capacity for cells to regulate LON through multiple stress-responsive signaling pathways highlight the importance of this protease in protecting mitochondrial proteostasis and function. A predominant function of LON is to degrade damaged proteins in the mitochondrial matrix before they misfold and/or aggregate into toxic conformations that disrupt mitochondrial function (Bota and Davies, 2016). However, alterations in LON activity could also serve to sensitively adapt mitochondrial functions during stress through mechanisms such as COXIV remodeling and StAR degradation. This suggests the intriguing possibility that cells can actively adapt mitochondrial function to specific environmental or metabolic demands through the specific stress-responsive regulation of the LON protease.

Posttranslational Regulation of Mitochondrial Proteolytic Activity

Apart from transcriptional regulation, mitochondrial proteases are also subject to posttranslational regulation. One the best characterized examples of this is the regulation of OMA1 proteolytic activity (Fig. 6). OMA1 exists in mitochondria as an inactive protease. In response to cellular insults that activate OMA1 proteolytic activity (e.g., membrane depolarization), OMA1 induces rapid processing of the inner membrane GTPase OPA1 to promote mitochondrial fission (Anand et al., 2014; Head et al., 2009; Rainbolt et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). Interestingly, the activated OMA1 protease then undergoes degradation, which serves to restrict OMA1 proteolytic activity (Baker et al., 2014; Rainbolt et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). This OMA1 degradation requires both OMA1 proteolytic activity and the ATP-dependent activity of the inner membrane protease YME1L. The dependence on the activities of these two proteases appears to result from a two step mechanism involving autocatalytic processing of OMA1 required for protease activation followed by ATP-dependent degradation of the active OMA1 protease by YME1L (Rainbolt et al., 2016). Through this mechanism, OMA1 activity is suppressed after an acute insult allowing effective recovery of mitochondrial morphology.

Figure 6.

Illustration showing the reciprocal regulation of OMA1 and YME1L induced by distinct types of cellular insults. Acute insults that depolarize mitochondria activate OMA1 protease activity, which is then repressed through a mechanism involving ATP-dependent degradation by the protease YME1L. In response to insults that depolarize mitochondria and deplete cellular ATP (e.g., oxidative stress), YME1L is degraded, suppressing protease activity through a mechanism involving activated OMA1.

Interestingly, the inner membrane protease YME1L is also susceptible to stress-induced degradation (Rainbolt et al., 2016; Rainbolt et al., 2015). Oxidative insults that reduce cellular ATP and depolarize mitochondria increase degradation of YME1L through a mechanism involving the activity of the inner membrane protease OMA1 (Fig. 6). This degradation of YME1L prevents many protective YME1L functions including Tim17A degradation and suppression of OMA1 proteolytic activity, increasing cellular sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli (Rainbolt et al., 2016; Rainbolt et al., 2015). Degradation of YME1L also defines a reciprocal relationship between the regulation of YME1L and OMA1 proteolytic activity during stresses that induce mitochondrial damage in the presence or absence of metabolic crisis (Rainbolt et al., 2016). Mitochondrial depolarization in the absence of metabolic crisis will lead to transient activation of the OMA1 protease, which is then suppressed through ATP-dependent degradation by YME1L. However, mitochondrial depolarization in the presence of a metabolic crisis that reduces cellular ATP will stabilize active OMA1 and lead to YME1L degradation. A consequence of this regulation is the inability to recover from a mitochondrial fragmented states. Thus, the reciprocal regulation between YME1L and OMA1 indicates that the sensitive regulation of these proteases provides a unique opportunity to dictate mitochondrial morphology in response to different types and extents of cellular stress.

Apart from degradation, proteases are also susceptible to regulation through posttranslational modifications. While few examples are known, there are some cases where protease stability and/or activity have been reported to be regulated through posttranslational modification. Phosphorylation of the inner membrane protease AFG3L2 at tyrosine 179 suppresses processing of paraplegin during co-assembly of the AFG3L2/paraplegin m-AAA heterooligomeric complex (Almontashiri et al., 2014). Following assembly, AFG3L2 is de-phosphorylated allowing mature paraplegin to be proteolytically processed by AFG3L2. Similarly, LON acetylation by sirtuin-3 has been proposed to regulate the stability and activity of this protease (Gibellini et al., 2014). Posttranslational modifications of substrates can also influence their susceptibility to proteolysis. For example, phosphorylation of the mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM impairs binding to DNA and promotes degradation by the quality control protease LON. Similarly, phosphorylation of cytochrome c oxidase subunits I, IVi1 and Vb increase targeting to LON for degradation upon hypoxic/ischemic insult (Lu et al., 2013; Sepuri et al., 2017).

The capacity to sensitively influence mitochondrial proteolytic activity through diverse posttranslational mechanisms provides additional levels for the stress-responsive regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis and function. While the mechanisms by which these posttranslational modifications integrate with transcriptional aspects of protease regulation remain to be established, it is clear that the regulation of these proteases is a central mechanism by which cells adapt mitochondrial function to match the specific demands required by a given insult.

Altered Mitochondrial Protease Activity in Aging and Disease

As outlined above, the diverse mechanisms of mitochondrial protease regulation provide a platform that allows cells to adapt mitochondrial function in response to diverse cellular insults. Imbalances in this regulation induced by protease mutations, alterations in stress-responsive signaling pathways, or aging predispose individuals to mitochondrial dysfunction in etiologically diverse human disorders including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders (Quiros et al., 2015; Rugarli and Langer, 2012). Below, we describe how alterations in mitochondrial protease activity could influence pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction in these types of disorders.

Mutations in mitochondrial proteases are genetically linked to diverse neurodegenerative disorders.

Mutations in mitochondrial quality control proteases have been causatively associated with the onset and pathology of numerous neurological disorders (Quiros et al., 2015; Rugarli and Langer, 2012). Most notably, mutations in the two m-AAA protease subunits AFG3L2 and paraplegin are implicated in different neurodegenerative diseases that present with varying levels of severity. Heterozygous mutations in AFG3L2 cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 28 (Di Bella et al., 2010), while homozygous mutations in the same gene cause different neurological syndromes with onset in early infancy (Eskandrani et al., 2017; Muona et al., 2015; Pierson et al., 2011). Alternatively, SPG7 mutations cause hereditary spastic paraplegia type 7 (Brugman et al., 2008; Casari et al., 1998; Elleuch et al., 2006). While the specific mechanism(s) by which these mutations influence disease pathogenesis remain to be fully elucidated, mouse models deficient in these two m-AAA subunits have provided significant insights into disease etiology associated with proteolytic dysregulation. Mice lacking either Afg3l2 or Spg7 show neurologic defects including disrupted mitochondrial morphology, impaired Ca2+ buffering, axon degeneration, and impaired axon development (Almajan et al., 2012; Ferreirinha et al., 2004; Kondadi et al., 2014; Maltecca et al., 2008; Maltecca et al., 2015; Maltecca et al., 2009) – all phenotypes also observed in patients. Loss of AFG3L2 has also been shown to impair mitochondrial axonal transport and is associated with tau hyperphosphorylation (Kondadi et al., 2014), the latter of which can promote proteotoxic tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. These results highlight the importance of the m-AAA protease in neuronal mitochondrial function and indicate that genetic mutations that disrupt m-AAA proteolytic activity cause pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction thereby impairing diverse neurologic functions.

Mutations in other mitochondrial quality control proteases have also been implicated in neurodegenerative disease. Mutations in the IMS quality control protease HTRA2 are associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Bogaerts et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2011; Strauss et al., 2005), however the strength of this association remains to be fully established (Kruger et al., 2011; Spataro et al., 2015). Regardless, a potential role for HTRA2 in PD is supported by in vivo evidence showing that HTRA2-deficient mice and mice expressing a mutant HTRA2 present parkinsonian phenotypes (Jones et al., 2003; Kruger et al., 2011; Martins et al., 2004). Furthermore, HTRA2 mutations have been suggested to impair the autophagic degradation of α-synuclein aggregates, providing a potential mechanism to explain how mutations in this gene could induce the neuromuscular phenotypes associated with PD (Li et al., 2010). HTRA2 mutations have also been suggested to influence other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (Westerlund et al., 2011) and infantile neurodegeneration (Mandel et al., 2016), although the molecular underpinnings of these relationships have not been elucidated. Rare PARL mutations have also been suggested to influence PD (Heinitz et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011; Wust et al., 2015). A potential role for PARL in PD could reflect the involvement of this protease in regulating the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy axis (Greene et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2010; Meissner et al., 2015; Yamano and Youle, 2013), which would be consistent with the link between PD and other proteins involved in this pathway (Youle and Narendra, 2011). YME1L1 mutations have also been found to be causatively associated with mitochondriopathy in familial optic atrophy (Hartmann et al., 2016). Here, mutations in the YME1L1 mitochondrial targeting sequence affect MPP-dependent maturation of the protease, decreasing YME1L proteolytic activity and disrupting mitochondrial morphology and function.

Apart from mitochondrial quality control proteases, mutations in mitochondrial processing peptidases are also associated with neuronal disease. IMMPL2 mutations are linked to many diseases including autism, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and Tourette syndrome (Elia et al., 2010; Maestrini et al., 2010; Petek et al., 2007; Petek et al., 2001). Furthermore, Immpl2 mutant mice show increased levels of oxidative stress, providing a potential mechanism to explain neuronal phenotypes associated with alterations in this protein (George et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016). Altered activity of the peptidase PreP has also been suggested to influence neurodegeneration in AD. PreP degrades the amyloidogenic peptide amyloid β in mitochondria (Falkevall et al., 2006; Mossmann et al., 2014). Thus, mutations that alter the activity of this protease could impair its function and promote mitochondrial dysfunction in association with AD (Alikhani et al., 2011b; Brunetti et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2015).

Apart from neuronal disorders, mutations in mitochondrial proteases also influence mitochondrial function in association with other types of diseases. LON mutations that disrupt the oligomerization and/or activity of this quality control protease lead to impaired mitochondrial proteostasis and function in association with cerebral, ocular, dental, auricular and skeletal (CODAS) syndrome (Strauss et al., 2015). CLPP mutations are implicated in Perrault disease, which involves ovarian failure and sensorineural hearing loss (Ahmed et al., 2015; Jenkinson et al., 2013). Interestingly, mice deficient in Clpp recapitulate many Perrault-associated phenotypes, suggesting that alteration in CLPP-dependent regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis is causative in this disease (Gispert et al., 2013). Finally, XPNPEP3 mutations are associated with the autosomal recessive kidney disease nephronophthisis, likely resulting from a mechanism involving impaired ciliary function (O’Toole et al., 2010). The genetic links between mitochondrial proteases and human disease described above clearly highlights the central importance of these proteases for regulating mitochondrial function.

Mutations in the stress-responsive signaling pathways responsible for regulating mitochondrial proteolytic activity and proteostasis could also directly contribute to pathologic mitochondrial dysfunction in association with disease. For example, mutations in the ISR-associated kinase PERK have been implicated in the onset and pathogenesis of diseases including Wolcott-Rallison Syndrome (Delepine et al., 2000; Durocher et al., 2006; Julier and Nicolino, 2010). Interestingly, the pathogenesis of these diseases has been observed to include impaired mitochondrial morphology and function (Collardeau-Frachon et al., 2015; Engelmann et al., 2008; Sovik et al., 2008). While PERK has many functions involved in the global regulation of cellular proteostasis and physiology during ER stress, it is possible that impaired PERK-dependent regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis directly contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction in association with this disease. As we continue to learn more of the integrative mechanisms by which stress-responsive signaling pathways such as the ISR and UPRmt regulate mitochondrial proteostasis, similar types of relationships can be established to demonstrate how genetic perturbations of these pathways can influence mitochondrial function by impairing stress-responsive regulation of proteostasis.

Aging dependent alterations in mitochondrial proteolytic capacity

Imbalances in mitochondrial proteostasis and function are a pathologic hallmark of the aging process in various organisms and in diverse tissues (Lopez-Otin et al., 2013). Mitochondrial proteases and their regulation are centrally implicated in the decline of mitochondrial function associated with the aging process (Quiros et al., 2015). Notably, the stress-responsive protease LON is intricately linked with organismal aging. Aging reduces the protein levels and activity of the LON protease in tissues including skeletal muscles and liver (Bakala et al., 2003; Bota et al., 2002; Lee et al., 1999). Similarly, while LON protein levels increase in the aging heart (likely reflecting stress-responsive regulation of this protease), LON activity does not, indicating that the specific activity of LON decreases with age in this tissue (Delaval et al., 2004). The importance of LON in aging is evident from studies in model organisms. Overexpression of LON in P. anserina increases organismal lifespan (Luce and Osiewacz, 2009). Alternatively, deletion of the S. cerevisiae Lon homolog, Pim1, accelerates aging in yeast (Erjavec et al., 2013). These results implicate LON activity as being an important determinant in eukaryotic aging.