Abstract

Aim: Inflammatory arthritis (IA) diseases are relevant with subclinical atherosclerosis, but the data in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) were inconsistent. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to explore the relationship between the marker of subclinical atherosclerosis (carotid intima-media thickness (IMT)) and AS.

Methods: We performed a systematic literature review using PubMed, Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) databases up to March 2018. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the association between carotid IMT and AS. Subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and meta-regression were applied to explore the sources of heterogeneity, and publication bias was calculated to access the quality of pooled studies.

Results: A total of 24 articles were collected. The carotid IMT was significantly increased in AS compared with healthy controls (SMD = 0.725, 95% CI = 0.443–1.008, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses showed the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index (BASDAI) was the source of heterogeneity. Notably, IMT was not significantly increased in those studies that included > 50% patients treated with anti-TNF. Meta-regression revealed severe inflammation status (BASDAI and C-reactive protein (CRP)) could significantly impact carotid IMT in AS.

Conclusions: Carotid IMT was significantly increased in patients with AS compared with healthy controls, which suggested subclinical atherosclerosis is related to AS.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Atherosclerosis, Carotid intima-media thickness, Inflammation

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic autoimmune disorder primarily affecting sacroiliac joints and the axial skeleton, while radiographic structural change can be observed in X-ray1). The extra-articular manifestation of AS is involved in eye, bowel, lung, heart, skin, and kidney. In addition, cardiovascular disease (CVD), a common extra-articular manifestation, has been triggered a heated interesting in AS during recent decades due to a protracted burden of disease to patients with AS. Studies revealed the prevalence of CVD in AS was higher than age- and sex-matched controls, and CVD has been identified as the leading cause of death in AS2, 3). In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the association between carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, and CVD has been well-described4). However, the association between subclinical atherosclerosis and AS is still a matter of study.

Carotid IMT is a convenient, noninvasive marker, which usually can be used to assess subclinical atherosclerosis and the progression of CVD in clinical practice5). Based on these advantages, carotid IMT has been recognized as one of most predictive markers of the majority of cardiovascular events, including stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and coronary heart diseases (CHDs)6, 7). Many publications have indicated the link between accelerated atherosclerosis and excess mortality and morbidity in AS8, 9), and the accelerated atherosclerosis could not be fully explained by the traditional cardiovascular factors10). Besides, some studies suggested the key role of inflammation and the potential pathogenesis that led to atherosclerosis11, 12). Furthermore, Van et al. reported that treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors might improve or slow the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with AS13). Since the excess prevalence of CVD in young patients with AS and the measurement advantages of carotid IMT by high-resolution ultrasound, there were plenty of studies that investigated whether carotid IMT was increased in AS compared with matched controls, and TNF inhibitors may slow or improve this progression. Some studies reported subclinical atherosclerosis did not lead to the excess cardiovascular risk of AS14, 15), whereas an opposite viewpoint existed in other studies16, 17). Likewise, this situation also happened in the curative effect of anti-TNF therapy for subclinical atherosclerosis in AS18, 19).

Therefore, the aim of our study was to compare the subclinical atherosclerosis markers carotid IMT in AS with healthy controls to evaluate the influence of AS on carotid IMT. Moreover, we performed subgroup and meta-regression analysis to assess the effect of the treatment with anti-TNF α, and some demographic and inflammatory variables on the pooled results.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

PubMed, Web of Science (WOS), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) databases were searched to identify all relative articles up to March 2018. The following searching strategies were used: (“ankylosing spondylitis” or “AS”) and (“carotid intima-media thickness” or “carotid IMT”), and our research only concerned articles published in English or Chinese. Besides, we searched the references of these qualified articles to identify more relative literature.

Selection Criteria

We included articles that met the following criteria: (a) case-control designed studies; (b) the control group must be health controls; (c) the literature must provide relative data about carotid IMT; (d) these published in English or Chinese on account of accurately examined the quality of papers. The exclusion criteria were: (a) not meeting the above criteria; (b) unrelated study population; (c) meta-analysis, review or case report; (d) study failed to get full text.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Correlational literatures were carefully and independently scanned by two authors (Yaping Yuan and Jiajia Yang) from all searchable studies based on the selection criteria, and disagreements were settled by corresponding author (Faming Pan). For each pooled article, we collected age and sex ratio, race, language, the rate of HLA-B27 (Human Leukocyte Antigen-B27) positivity, disease duration, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index (BASDAI) score, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), the proportion of AS treated with anti-TNF α and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) of patients, and carotid IMT both of patients and controls. In addition, we also collected the name of first author, publishing year, region of study population, matched factors and measurement method of carotid IMT, including mean IMT of bilateral or right common carotid artery (CCA), blind condition, and other detailed information. All pooled studies were assessed independently by two authors according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) assessment scale20), which is a valid tool for evaluating the bias for observational study. The NOS including three dimensions: selection, comparability, and exposure. A maximum score was 9 points, and score ≥ 7 was considered high quality.

Data Analysis

Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) software was used to perform the meta-analysis. Variables were described as mean with standardized difference (SD), or median with interquartile range (IQR) or range. Differences between patients and controls were expressed as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For combining the results of all included articles, an approximation method was performed to assess mean and SD of some articles when these reported the results using median with IQR or range. In this instance, we would transform the original data into the required values21). The overall effect was accessed by Z scores and p < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference in forest plot. Chi-square Cochran's Q test and I2-statistic, which measures the percentage of total variation, was used to access the heterogeneity of pooled studies in this meta-analysis. When I2 > 50% or p < 0.01 of Q test, we recognized these studies have significant heterogeneity, which should calculate pooled SMD based on the random-effects model. Otherwise, fixed-effects model was performed to calculate pooled SMD. Subgroup analysis was performed to identify whether sample size, race, the proportion of patients treated with anti-TNF α and BASDAI could lead to heterogeneity. Besides, meta-regression analysis in terms of publishing year, age, NOS, ESR, CRP, BASDAI, disease duration, matched factors, and IMT measurement (both side or the right side of CCA) were performed to explore potential source of heterogeneity. Moreover, we performed sensitivity analysis to examine the influence of a single study on the overall SMD when high heterogeneity existed. In addition, Egger's test or Begg's test was performed to evaluate the potential publication bias. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference.

Results

Study Characters

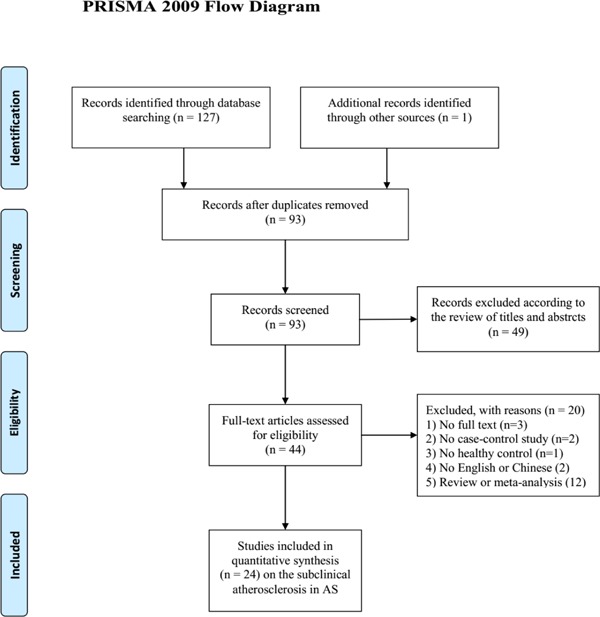

The detailed selection flow is shown in Fig. 1. We searched 127 correlative articles based on the above research strategies, and 1 article was obtained by searching the references. After excluding the duplicate citations, 93 articles still remained; after screening the titles and abstracts, 44 articles were further screened based on the full text. We excluded 1 article because it enrolled patients with AS and axis spondyloarthritis, and the exact data about carotid IMT were not accessed. Besides, publication bias existed when including the article22), so we excluded this article. Finally, 24 articles (1120 patients and 943 healthy controls) were pooled into quantitative synthesis.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies for inclusion in this meta-analysis

The information of salient demographic characteristics and clinical information of the pooled study population are shown in Table 1. This meta-analysis includes 24 articles, in which 11 were conducted in Turkey15, 17, 23, 26–29, 33, 35, 38, 40), 3 in Italy24, 25, 39), 2 in India14, 32), and 1 each in Korea16), France18), Greece19), Tunisia30), Hungary31), the Netherlands34), Spain36) and Poland37). In patients, the mean age ranged from 29.4 to 52.6 years, and the percent of male gender and B27 positivity ranged from 53% (M/F: 29/54) to 100% and 48% to 100%, respectively. Mean value of disease duration varied from 5.0 to 19.1 years, of BASDAI from 1.9 to 5.35 cm, of ESR from 9.17 to 45.19 mm/h, of CRP from 0.53 to 18.9 mg/dl. Moreover, the percent of patients treated with anti-TNF and NSAIDs both varied from 0 to 100%.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data of AS in pooled studies.

| First author (publish year) |

N | Sex ratio (M/F) |

Age (year) |

Region/Race | B27 + % | Matched factors | Disease duration (years) |

BASDI (cm) |

ESR (mm/h) |

CRP (mg/dl) |

NSAIDS treatment (%) |

Anti-TNFα treatment (%) |

NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choe (2008) | 28 | 23/5 | 31.8 | Korea/Asian | 82.1 | Age, sex, and BMI | 5.0 ± 3.9 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 8 |

| Gecene (2013) | 50 | 50/0 | 36.66 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age, sex, and BMI | 9.8 ± 4.87 | 2.39 ± 1.66 | 26.10 ± 17.70 | 1.29 ± 1.48 | 88.0 | 18.0 | 8 |

| Kucuk (2017) | 60 | 45/15 | 41.68 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age and sex | NA | 4.01 ± 2.14 | 13.31 ± 13.51 | 11.53 ± 22.23 | NA | 38.3 | 7 |

| Malesci (2007)§ | 24 | 21/3 | 51 | Italy/Caucasian | NA | Age and sex | 16.5 (3–45) | 2.13 (0.7–7.4) | NA | NA | 16.7 | 0 | 6 |

| Erre (2011)§ | 17 | 10/7 | 39 | Italy/Caucasian | 82.3 | Age, sex, and CVD risk factors | 9.5 ± 9.0 | 2.7 ± 2.8 | 7 (2.5–18) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 0 | 58.8 | 8 |

| Resorlu (2015) | 40 | 26/14 | 42.75 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | NA | NA | NA | 18.6 ± 11.2 | NA | NA | 0 | 7 |

| Beyazal (2016) | 60 | 43/17 | 40.4 | Turkey/Caucasian | 78.3 | Age and sex | 6.5 ± 5.2 | 5 ± 1.6 | 21.7 ± 15.1 | NA | 40 | 60 | 8 |

| Cure (2018)§ | 52 | 52/0 | 39.3 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age and BMI | 9.0 ± 7.1 | 4.0 ± 4.5 | 7 (1–42) | 5.5 (0.4–35.4) | 86.5 | 48.1 | 8 |

| Kucukail (2017) | 43 | 28/15 | 34.6 | Turkey/Caucasian | 81.4 | NA | 9.3 ± 7.0 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 27.3 ± 13.8 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 100 | 0 | 7 |

| Ustun (2014) | 26 | 22/4 | 43.7 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age, sex, and BMI | 11.83 ± 10.98 | 4.1 ± 2 | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 7 |

| Verma (2015) | 30 | 21/9 | 34.2 | India/Asian | NA | Age and sex | 8.7 ± 5.8 | 4.89 ± 0.61 | 29.03 ± 10.29 | 14.92 ± 12.71 | 100 | 0 | 8 |

| Hamdi (2012) | 60 | 48/12 | 36 | Tunisia/African | 48 | Age and sex | 13.1 ± 8.5 | 4.9 ± 2.7 | 42.6 ± 29.2 | 18.9 ± 22.9 | 95 | 6.6 | 7 |

| Bodnar (2011) | 43 | 31/12 | 45.4 | Hungary/Caucasian | 83.7 | Age and sex | 13.2 ± 10.6 | 5.04 ± 1.91 | 15.5 ± 15.6 | 9.00 ± 11.5 | 86 | 65 | 7 |

| Cece (2011) | 45 | 36/9 | 36.8 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age, sex, and BMI | 12.8 ± 6.3 | 4.16 ± 1.8 | 26.8 ± 10.6 | NA | 57.8 | 0 | 8 |

| Gupta (2014) | 37 | NA | 31.46 | India/Asian | 75.7 | Age and sex | 5.2 ± 4.58 | 4.11 ± 1.99 | 45.19 ± 26.04 | 7.36 ± 7.38 | NA | NA | 7 |

| Sari (2006) | 54 | 29/25 | 37 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age, sex, and BMI | 12.4 ± 9.2 | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 24 ± 17 | 14 ± 19 | NA | NA | 8 |

| Mathieu (2008)§ | 60 | 44/16 | 40.67 | France/Caucasian | 82 | Age, sex, and smoking status | 11.0 (3.0–19.0) | 2.99 (1.15–5.77) | NA | 6.6 (1.1–15.6) | 63.3 | 36.7 | 8 |

| Stanek (2017) | 48 | 48/0 | 46.06 | Poland/Caucasian | 100 | Age, BMI, and CVD risk factors | NA | 5.35 ± 1.64 | 27.13 ± 21.55 | NA | 100 | 0 | 8 |

| Peters (2010)§ | 59 | 37/22 | 38.33 | Netherland/Caucasian | 88 | Age and sex | 9 (3–13) | 6.2 ± 1.3 | NA | 8 (3–25) | 100 | 100 | 8 |

| Ercan (2012) | 66 | 50/16 | 30.9 | Turkey/Caucasian | NA | Age and sex | 5.0 ± 4.17 | NA | 17.6 ± 14.7 | 15.9 ± 20.2 | NA | 60.6 | 7 |

| Gonzalez-Juana-tey (2009) | 64 | 51/13 | 52.6 | Spain/Caucasian | 73.4 | Age, sex, race, and CVD risk factors | 19.1 ± 11.2 | 3.04 ± 1.95 | 2.53 ± 0.89 | 1.20 ± 1.27 | 100 | 32.8 | 8 |

| Perrotta (2013)§ | 20 | 12/8 | 4 | Italy/Caucasian | 75 | Age and sex | 9.7 (1–36) | 4.22 (2.36–6.01) | 14 (4–35) | 1.4 (0.1–3.4) | 30 | 0 | 8 |

| Capkin (2011) | 67 | 57/10 | 37.0 | Turkey/Caucasian | 73 | Age, sex, BMI, and CVD risk factors | 7.2 ± 3.9 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 27.0 ± 16.7 | 1.72 ± 1.1 | 49 | 51 | 7 |

| Arida (2015)§ | 67 | 55/67 | 47.54 | Greece/Caucasian | NA | Age, sex, and CVD risk factors | 12 (3–25) | 1.8 (0.4–3.6) | 21 (8–44) | 3.62 (2–10) | NA | 66 | 7 |

The value of variables was expressed as median with interquartile range or range; SD, standardized difference; M/F, male/female; NSAIDS, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; age is expressed as mean value, unless otherwise indicated; NA, not accessed.

The information of the value of carotid IMT and measurement method are displayed in Table 2. Twenty-four studies were included in our present study, in which 19 studies measured mean carotid IMT of bilateral CCAs; the others measured mean IMT of the right CCA. Moreover, 50% of the studies reported the examination of IMT performed under patients were in blind condition. Based on the criteria of NOS, we found that 11 studies15, 19, 23, 26, 29, 30–32, 35, 40) might be exposed to potential selection bias, thus the score of the above articles were 6 or 7 points. Thirteen studies scored 8 points, 8 studies scored 7 points, and only 1 study scored 6 points. The median value of NOS was 8 points.

Table 2. Results of carotid IMT and measurement method of patients and controls.

| First author (publish year) |

No. AS |

No. controls |

carotid IMT (mm) |

p | Measurement method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (mean ± SD) |

Controls (mean ± SD) |

|||||

| Choe (2008) | 28 | 27 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 0.387 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; automatic IMT measurement software; IMT ≥ 1.3 mm is defined carotid plaque; same radiologist |

| Gecene (2013) | 50 | 50 | 0.57 ± 0.13 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 0.298 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; IMT > 1.3 mm is defined carotid plaque |

| Kucuk (2017) | 60 | 54 | 0.99 ± 0.27 | 0.76 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs |

| Malesci (2007) | 24 | 19 | 0.52 ± 0.26 | 0.51 ± 0.13 | NS | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs, bulbs and ICAs; maximum IMT > 1 mm is considered abnormal; blind condition; same radiologist |

| Erre (2011) | 17 | 17 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 0.67 ± 0.10 | NS | Mean IMT at the maximum thickness (outside of plaque) of bilateral CCAs; blind condition; same radiologist |

| Resorlu (2015) | 40 | 40 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.57 ± 0.12 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; same radiologist |

| Beyazal (2016) | 60 | 50 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs |

| Cure (2018) | 52 | 52 | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 0.003 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs, bulbs and ICAs; blind condition |

| Kucukali (2017) | 43 | 41 | 0.60 ± 0.30 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | 0.501 | Mean IMT of the right CCA |

| Ustun (2014) | 26 | 26 | 0.70 ± 0.16 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 0.012 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; blind condition |

| Verma (2015) | 30 | 25 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.006 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; blind condition |

| Hamdi (2012) | 60 | 60 | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.39 ± 0.09 | 0.001 | bilateral CCAs; blind condition |

| Bodnar (2011) | 43 | 40 | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.15 | 0.010 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; same radiologist |

| Cece (2011) | 45 | 30 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 0.49 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; blind condition; same radiologist |

| Gupta (2014) | 37 | 37 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; same radiologist |

| Sari (2006) | 54 | 31 | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 0.370 | Mean IMT at maximum thickness of bilateral CCAs |

| Mathieu (2008)§ | 60 | 60 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 0.023 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; blind condition; same radiologist |

| Stanek (20170 | 48 | 48 | 1.10 ± 0.13 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | < 0.001 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; blind condition |

| Peters (2010) | 59 | 30 | 0.62 ± 0.09 | 0.57 ± 0.009 | 0.020 | Mean IMT of the right CCA (outside of plaque); blind condition |

| Ercan (2012) | 66 | 21 | 0.69 ± 0.20 | 0.63 ± 0.20 | 0.400 | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs |

| Gonzalez-Juanatey (2009) | 64 | 64 | 0.74 ± 0.21 | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.010 | Mean IMT of the right CCA; automatic IMT measurement software; IMT > 1.5 mm is considered plaque; blind condition; same radiologist |

| Perrotta (2013)§ | 20 | 20 | 0.61 ± 0.13 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | NS | Mean IMT of bilateral CCAs; IMT > 0.9 mm is considered pathological IMT; blind condition |

| Capkin (2011) | 67 | 34 | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 0.562 | Mean IMT of the right CCA |

| Arida (2015) | 67 | 67 | 0.73 ± 0.16 | 0.75 ± 0.21 | 0.421 | Mean IMT of the right CCA; automatic IMT measurement software; IMT > 1.5 mm is considered plaque; |

The value of variables was transformed by Ref. [21]; IMT, intima-media thickness; SD, standardized difference; CCA, common carotid artery.

Pooled Analysis and Sensitivity Analysis

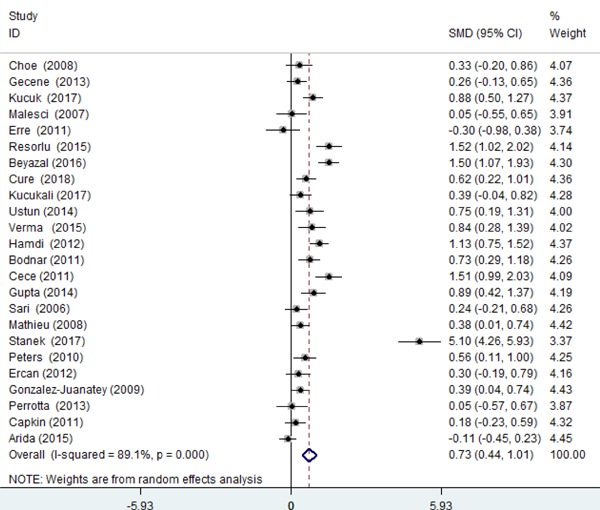

Given the significant heterogeneity among pooled studies (I2 = 89.1%, p < 0.001), we adopted random-effects model to calculate the pooled SMD. For pooled studies13–16, 19–38), carotid IMT was significantly increased in AS compared with healthy controls (pooled SMD = 0.725, 95% CI = 0.443–1.008, p < 0.001, Fig. 2). Given the high heterogeneity, we used sensitivity analysis by sequentially leaving out each single study that did not qualitatively change the pooled SMDs, indicating the result of our meta-analysis were stable (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Pooled carotid IMT in AS compared with healthy controls

Subgroup Analysis

We performed subgroup analysis stratified by sample size (< 100 and ≥ 100), race (Asian and Caucasian), the proportion of patients treat with anti-TNF α (< 50%, > 50%, and NA) and BASDAI (< 4, ≥ 4, and NA). Only 1 study population came from Africa26); therefore we left out this article to perform analysis stratified by race. The results showed sample size and race were not the source of heterogeneity (shown in Table 3). When studies were stratified by BASDAI, IMT was both increased in patients in active or inactive period (SMD = 1.167, p < 0.001, I2 = 91.0; SMD = 0.211, p = 0.002, I2 = 0.0%, respectively), but not increased in AS in an unaccessed subgroup (SMD = 0.909, p = 0.136). Moreover, subgroup results of studies stratified by the proportion of patients treated with anti-TNF therapy were inconsistent. The IMT difference between patients and controls was not significant > 50% and subgroup without reporting the percent (SMD = 0.422, p = 0.064, I2 = 85.8; SMD = 0.558, p = 0.090, I2 = 74.5, respectively), but the difference was significant in proportion ≤ 50 subgroup (SMD = 0.902, p < 0.001, I2 = 91.0). Detailed results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Subgroup-analyses. Carotid IMT in AS stratified by sample size, race, and BASDAI.

| No. pooled studies | No. patients | Effective value SMD with 95%CI; I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 24 | 1120 | SMD = 0.725; 95%CI = 0.443–1.008; p < 0.001; I2 = 89.1 |

| Stratified by sample size (N) | |||

| N < 100 | 15 | 580 | SMD = 0.834; 95%CI = 0.383–1.286; p < 0.001; I2 = 91.0 |

| N ≥ 100 | 9 | 540 | SMD = 0.575; 95%CI = 0.251–0.899; p = 0.001; I2 = 84.7 |

| Stratified by race | |||

| Asian | 3 | 95 | SMD = 0.695; 95%CI = 0.343–1.047; p < 0.001; I2 = 27.2 |

| Caucasian | 20 | 965 | SMD = 0.714; 95%CI = 0.384–1.043; p < 0.001; I2 = 90.6 |

| Stratified by BASDAI | |||

| NA | 2 | 106 | SMD = 0.909; 95%CI = −0.286–2.103; p= 0.136; I2 = 91.4 |

| BASDAI < 4 | 10 | 474 | SMD = 0.211; 95%CI = 0.078–0.345; p = 0.002; I2 = 0.0 |

| BASDAI ≥ 4 | 12 | 540 | SMD = 1.167; 95%CI = 0.707–1.626; p < 0.001; I2 = 91.0 |

| Anti-TNF α treatment | |||

| Anti-TNF ≤ 50% | 15 | 650 | SMD = 0.902; 95%CI = 0.502–1.302; p < 0.001; I2 = 91.0 |

| Anti-TNF > 50% | 7 | 379 | SMD = 0.422; 95%CI = −0.025–0.869; p = 0.064; I2 = 85.8 |

| NA | 2 | 91 | SMD = 0.558; 95%CI = −0.088–1.204; p = 0.090; I2 = 74.5 |

N, number of sample size; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence intervals; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index; NA, not accessed.

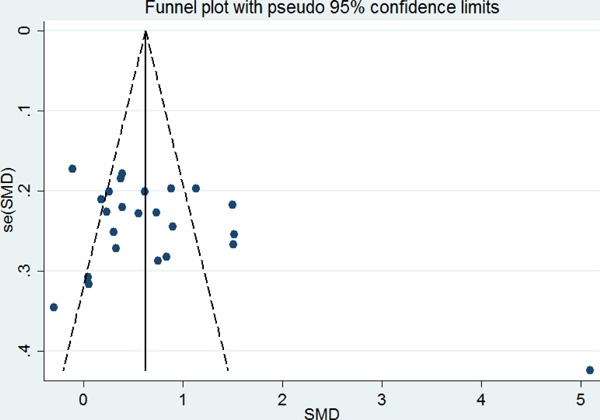

Publication Bias

Given that the existence of publication bias could influence the results of meta-analysis, we adopted a funnel graph to examine this bias in our analysis. The sharp end of the meta-funnel plot of enrolled studies seemed to be slightly unsymmetrical (Fig. 3), but the results of Begg's test (p = 0.602) and Egger's test (p = 0.061) were more than 0.05, which suggested publication bias was nonexistent.

Fig 3.

Publication bias by funnel diagram

Meta-Regression Analyses

Given the method of IMT measurement (mean IMT of bilateral CCAs or the right CCA) and number of matched factors (0, 2, and ≥ 3) difference among pooled studies, we enrolled these as categorical variables to build a regression model to explore whether these variables were the sources of high heterogeneity. In terms of age of patients, publication year, NOS, number of matched factors, IMT measurement, inflammatory markers (including ESR, CRP, and BASDAI) and disease duration to conduct a regression model, results showed that none of above factors (shown in Supplementary Table 1) impact the composite results, except for CRP and BASDAI (t = 0.039, p = 0.007; t = 0.516, p = 0.009, shown in Table 4).

Supplemental Table 1. Meta-regression analysis coefficients for carotid IMT in patients with AS.

| Variables | Coefficient (SE) | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publish year | 0.117 (0.057) | [0.001–0.235] | 0.053 |

| age | 0.016 (0.036) | [−0.058–0.091] | 0.657 |

| NOS | 0.323 (0.361) | [−0.426–1.072] | 0.381 |

| Disease duration | −0.020 (0.026) | [−0.075–0.034] | 0.449 |

| ESR | 0.024 (0.026) | [−0.029–0.079] | 0.352 |

| No. of matched factors | −0.054 (0.246) | [−0.565–0.456] | 0.827 |

| Measurement of IMT§ | −0.581 (0.495) | [−1.608–0.445] | 0.253 |

measurement including mean IMT of bilateral CCAs and of the right CCA; NOS: the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Table 4. Meta-regression analysis coefficients for carotid IMT in patients with AS.

| Variables | Coefficient (SE) | 95% Confidence Intervals | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASDAI | 0.516 (0.177) | [0.146–0.887] | 0.009 |

| CRP | 0.039 (0.012) | [0.012–0.065] | 0.007 |

BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index; CRP, C-reaction protein.

Discussion

AS is an inflammatory disorder that may involve multiple systems and organs, particularly the cardiovascular system. Two large cohort studies2, 41) demonstrated patients with AS are at increased risk of developing a cerebrovascular and CVD, which derived from accelerated atherosclerosis42). Carotid IMT is a valid and noninvasive marker for evaluating the subclinical atherosclerosis in carotid arteries6, 43). To date, more and more studies have focused on carotid IMT in AS. But, the sample size of the majority of these studies was small and the results were inconsistent. Thus, it is worthwhile for us to perform this study.

Our results indicated carotid IMT significantly increased in patients with AS compared with healthy controls, which showed AS is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis revealed by carotid IMT. Additionally, this association of subclinical atherosclerosis lies in the ability to predict CVD and further leads to the development of CVD. That was in line with previous studies displaying greater risk of cardiovascular-related mortality in AS44). However, high heterogeneity among studies was found in the present study (I2 = 89.1%).

A study among 67 AS patients, whose mean age were 47.54 years and most of whom received anti-TNF therapy, reported IMT was not increased in AS compared with controls19). In contrast, another study found greater IMT in AS14). Inconsistent results in the above studies might be derived from race, sample size, the proportion of patients treated with anti-TNF α and BASDAI30, 43). Further, results of subgroup analysis found the sources of high heterogeneity were not race, sample size, and the proportion of patients treated with anti-TNF α, but rather BASDAI. However, the difference of carotid IMT between AS and controls was not significant in the proportion of patients treated with anti-TNF α more than 50 and data not reported subgroup, but significant in the proportion ≤ 50 subgroup. This result partly suggested anti-TNF therapy might improve or slow the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Previous studies also reported reduction of carotid IMT in inflammation arthritis (RA, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and AS) patients received anti-TNF therapy while the progression was seen in control group45, 46). The underlying mechanisms of the development of IMT remained uncertain. The relationship between subclinical atherosclerosis and AS and the presence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors appear not to fully explain the accelerated atherosclerosis reported in AS. Even though some studies enrolled patients without traditional cardiovascular risk factors or CVD, carotid IMT was still increased in AS than in controls30, 31). Therefore, inflammation has been suggested to induce the development of atherosclerosis in AS11).

Inflammatory processes not only stimulate initiation and evolution of atheroma, but also lead to acute thrombotic complications of atheroma47). CRP, ESR, and BASDAI, markers of inflammation and disease activity, have demonstrated levels were significantly elevated in AS48). CRP could active complement, adhesion molecules and tissue factors, mediate LDL uptake by endothelial macrophages, active monocyte recruitment into arterial wall47). These physiological processes all contributed to the progression of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, an elevated level of CRP was associated with accelerated progression of atherosclerosis in young adults49). Likewise, disease activity and persistent inflammation were associated with vascular wall inflammation and atherosclerosis risk50). The results of the study stratified by BASDAI showed carotid IMT was both significantly increased in active or inactive patients compared with controls. Moreover, results of meta-regression analysis showed that BASDAI and CRP significantly impacted IMT and a more severe inflammation status (expressed by BASDAI and CRP) were related with higher IMT, which partly supported the hypothesis that inflammation may take an important role in the progression of atherosclerosis in AS51, 52). Based on this circumstance, inflammation or disease activity should be considered in the cardiovascular risk profile assessment of patients with AS in clinical practice. However, it was inconsistent with the previous result of a meta-analysis; Arida et al.19) reported that IMT was not increased in AS with low disease activity (BASDAI < 4), which might be due to the small number of included studies and cumulative sample size in the previous meta-analysis. Interestingly, the results of subgroup-analysis stratified by BASDAI and the percent of anti-TNF therapy in present studies seem to be inconsistent. In the present meta-analysis, 14 studies reported their patients treated with anti-TNF inhibitors, in which 7 studies reported the proportion of receiving anti-TNF inhibitors > 50%. Further, 3 studies reported the mean value of BASDAI of more than 4 cm among above 7 studies. Increase of inflammation may be considered the reasons for the greater subclinical atherosclerosis40). It should be noted that most of patients were exposed to NSAIDS, and we could not assess the impact of these drugs on IMT.

A plausible explanation for this might be that ESR levels are an indicator of the present level of disease activity and do not show the inflammatory burden which has built up over time32). Previous studies implied age and disease duration were involved into the development of atherosclerosis26). However, regression analysis showed disease duration and age did not significantly impact IMT, which could because atherosclerosis, a progressive process that begins at early ages49, 53).

Regarding matched factors that were different among studies, we took a number of matched factors as covariate to build a meta-regression model to identify its impact on pooled results. In keeping with the above results, matching or unmatched CVD risk factors have no impact on pooled results. Additionally, the majority of collected studies in this meta-analysis measured carotid IMT of both sides of CCAs, but the others measured IMT of the right side of the CCA. Besides, Loizou et al. reported it is not clear whether IMT is equal in both CCAs, as some studies have reported greater IMT in the left CCA is a predictor54), which could be explained by increased shear stress forces in the left CCA55). However, the meta-regression results suggested no significant difference between IMT on both sides, similar with the previous studies56). As reported in the above literature, differences between the left and right CCA happened to older people due to a combined effect of various CVD risk factors as well as potential differences between the shear forces between the two carotid arteries.

There are limitations in our meta-analysis that need to be discussed. First, the high heterogeneity existed among included studies. The subgroup and regression analyses suggested BASDAI and CRP led to more or less heterogeneity, but the source of high heterogeneity was not found in other potential factors. Finally, the ultrasound protocols performed to access carotid IMT were different. Among collected articles, approximate 50% of the articles reported the measurement performed in blind condition. Likewise, fewer than 50% studies reported an examination by same radiologist. A few studies reported intraobserver variability, and some studies lacked the definite definition of carotid plaques and maximum IMT. Furthermore, only a few articles provided the information on whether sites with plaques were included in IMT examination. Although these are some limitations existing in our study, the results of sensitivity analysis showed our results were robust.

In conclusion, in this meta-analysis, carotid IMT was significantly increased in patients with AS compared with healthy controls, and inflammation might be involved in this progression. However, anti-TNF therapy might minimize the increase of IMT in patients with AS. Additionally, prospective studies are needed to conduct exact models to predict the cardiovascular risk in patients with AS and verify the effect of anti-TNF therapy on carotid IMT.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank everyone who has helped us perform this study. This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30771849, 30972530, 81273169, 81573218, and 81773514) and funding for academic and technical leaders in Anhui Province, 2017D140.

COI

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1). Dubreuil M, Peloquin C, Zhang Y: Validity of ankylosing spondylitis diagnoses in The Health Improvement Network. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2016; 25: 399-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Szabo SM, Levy AR, Rao SR: Increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in individuals with ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis, 2011; 63: 3294-3304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Lehtinen K: Mortality and causes of death in 398 patients admitted to hospital with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis, 1993; 52: 174-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Liu YL, Skklo M, Davidson KW: Differential Association of Psychosocial Comorbidities with Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2015; 67: 1335-1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Katakami N, Kaneto H, Shimomura I: Carotid ultrasonography: A potent tool for better clinical practice in diagnosis of atherosclerosis in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Investig, 2014; 5: 3-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR: Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987–1993. Am J Epidemiol, 1997; 146: 483-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). O'Leary DH, Polak JF: Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med, 1999; 340: 14-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Papagoras C, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA: Atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in the spondyloarthritides, particularly ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2013; 31: 612-620 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Azevedo VF, Pecoits-Filho R: Atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int, 2010; 30: 1411-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): casecontrol study. Lancet, 2004; 364: 937-952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Frostegard J: Immunity, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. BMC med, 2013; 11: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Pant S, Deshmukh A, Gurumurthy: Inflammation and atherosclerosis--revisited. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther, 2014; 19: 170-178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Van Sijl AM, Van Eijk IC, Peters MJ: Tumour necrosis factor blocking agents and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis, 2015; 74: 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Verma I, Krishan P, Syngle A: Predictors of Atherosclerosis in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Rheumatol Ther, 2015; 2: 173-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Ustun N, Kurt M, Atci N: Increased Epicardial Fat Tissue Is a Marker of Subclinic Atherosclerosis in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Archives of Rheumatology, 2014; 29: 267-272 [Google Scholar]

- 16). Choe JY, Lee MY, Rheem I: No differences of carotid intima-media thickness between young patients with ankylosing spondylitis and healthy controls. Joint Bone Spine, 2008; 75: 548-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Gecene M, Tuncay F, Borman P: Atherosclerosis in male patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the relation with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (C677T) gene polymorphism and plasma homocysteine levels. Rheumatol Int, 2013; 33: 1519-1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Mathieu S, Joly H, Baron G: Trend towards increased arterial stiffness or intima-media thickness in ankylosing spondylitis patients without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 2008; 47: 1203-1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Arida A, Protogerou AD, Konstantonis G: Subclinical Atherosclerosis Is Not Accelerated in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis with Low Disease Activity: New Data and Metaanalysis of Published Studies. J Rheumatol, 2015; 42: 2098-2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Stang A: Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J epidemiol, 2010; 25: 603-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Wan X, Wang W, Liu J: Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2014; 14: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Verma I, Syngle A, Krishan P: Endothelial Progenitor Cells as a Marker of Endothelial Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Angiol, 2017; 26: 36-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Kucuk A, Ugur Uslu A, Icli A: The LDL/HDL ratio and atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Z Rheumatol, 2017; 76: 58-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Malesci D, Niglio A, Mennillo GA: High prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol, 2007; 26: 710-714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Erre GL, Sanna P, Zinellu A: Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels and atherosclerotic disease in ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol, 2011; 30: 21-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Resorlu H, Akbal A, Resorlu: Epicardial adipose tissue thickness in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol, 2015; 34: 295-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Beyazal MS, Erdogan T, Turkyilmaz AK: Relationship of serum osteoprotegerin with arterial stiffness, preclinical atherosclerosis, and disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol, 2016; 35: 2235-2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Cure E, Icli A, Uslu AU: Atherogenic index of plasma: a useful marker for subclinical atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis: AIP associate with cIMT in AS. Clin Rheumatol, 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Kucukali Turkyilmaz A, Devrimsel G, Serdaroglu Beyazal: The relationship between serum YKL-40 levels and arterial stiffness in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Acta Reumatol Port, 2017; 42: 183-190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Hamdi W, Bouaziz MC, Zouch I: Assessment of Preclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol, 2012; 39: 322-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Bodnar N, Kerekes G, Seres I: Assessment of subclinical vascular disease associated with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol, 2011; 38: 723-729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Gupta N, Saigal R, Goyal L: Carotid intima media thickness as a marker of atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheumatol, 2014; 2014: 839135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Sari I, Okan T, Akar S: Impaired endothelial function in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 2006; 45: 283-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Peters MJ, van Eijk IC, Smulders YM: Signs of accelerated preclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol, 2010; 37: 161-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Ercan S, Goktepe F, Kisacik B: Subclinical cardiovascular target organ damage manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis in young adult patients. Mod Rheumatol, 2013; 23: 1063-1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Miranda-Filloy JA: The high prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Medicine (Baltimore), 2009; 88: 358-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Stanek A, Cholewka A, Wielkoszynski T: Increased Levels of Oxidative Stress Markers, Soluble CD40 Ligand, and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Reflect Acceleration of Atherosclerosis in Male Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Active Phase and without the Classical Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017; 2017: 9712536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Cece H, Yazgan P, Karakas E: Carotid intima-media thickness and paraoxonase activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Invest Med, 2011; 34: E225-E231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Perrotta FM, Scarno A, Carboni A: Assessment of subclinical atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis: correlations with disease activity indices. Reumatismo, 2013; 65: 105-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Capkin E, Kiris a, Karkucak M: Investigation of effects of different treatment modalities on structural and functional vessel wall properties in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine, 2011; 78: 378-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J: Risk of subsequent ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in patients hospitalized for immune-mediated diseases: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. BMC Neurol, 2012; 12: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). John H, Kitas G: Inflammatory arthritis as a novel risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Intern Med, 2012; 23: 575-579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Katakami N, Mita T, Gosho M: Clinical Utility of Carotid Ultrasonography in The Prediction of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Diabetes: A Combined Analysis of Data Obtained in Five Longitudinal Studies. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Haroon NN, Paterson JM, Li P: Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis Have Increased Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Mortality: A Population-Based Study. Annals of internal medicine, 2015: 163: 409-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Angel K, Provan SA, Fagerhol MK: Effect of 1-year anti-TNF-alpha therapy on aortic stiffness, carotid atherosclerosis, and calprotectin in inflammatory arthropathies: a controlled study. Am J Hypertens, 2012; 25: 64450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Tam LS, Li EK, Shang Q: Tumour necrosis factor alpha blockade is associated with sustained regression of carotid intima-media thickness for patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a 2-year pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis, 2011; 70: 7056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A: Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation, 2002; 105: 1135-1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Chen CH, Chen HA, Liao HT: The clinical usefulness of ESR, CRP, and disease duration in ankylosing spondylitis: the product of these acute-phase reactants and disease duration is associated with patient's poor physical mobility. Rheumatol Int, 2015; 35: 1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Zieske AW, Tracy RP, McMahan CA: Elevated serum C-reactive protein levels and advanced atherosclerosis in youth. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2005; 25: 1237-1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Divecha H, Sattar N, Rumley A: Cardiovascular risk parameters in men with ankylosing spondylitis in comparison with non-inflammatory control subjects: relevance of systemic inflammation. Clin Sci (London), 2005; 109: 171-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Hansson GK, Robertson AK, Söderberg-Nauclér C: Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol, 2006; 1: 297-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Kubota M, Yoneda M, Watanabe H: Progression of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Two Japanese Populations with Different Lifestyles. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017; 24: 1069-1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Kähönen M: Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intimamedia thickness in adulthood. JAMA, 2003; 290: 2277-2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54). Lee SW, Hai JJ, Kong SL: Side differences of carotid intima-media thickness in predicting cardiovascular events among patients with coronary artery disease. Angiology, 2011; 62: 231-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Bots ML, de Jong PT, Hofman A: Left, right, near or far wall common carotid intima-media thickness measurements: Associations with cardiovascular disease and lower extremity arterial atherosclerosis. J Clin Epidemiol, 1997; 50: 801-807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56). Arbel Y, Maharshak N, Gal-Oz A: Lack of difference in the intimal medial thickness between the left and right carotid arteries in the young. Acta Neurol Scand, 2007; 115: 409-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]