Abstract

Current psycholinguistic research generally acknowledges that aspects of sentence comprehension benefit from neural preactivation of different types of information. However, despite strong support from a number of studies, routine specific word form preactivation has been challenged by Ito, Corley, Pickering, Martin, & Nieuwland (2016). They suggest that word form prediction is contingent upon having enough processing time and resources (afforded by slower input rates) to progress through unidirectional, production-like stages of comprehension to arrive at word forms via semantic feature preactivation. This conclusion is based on findings from their event-related brain potential study, which used a related anomaly paradigm and reported form preactivation at a slow (700ms) word presentation rate but not a faster one (500 ms). The present experimental design is a conceptual replication of Ito et al. (2016), testing young adults by measuring ERP amplitudes to unpredictable words related either semantically/associatively or orthographically to predictable sentence continuations, relative to unrelated continuations. Results showed that at a visual presentation rate of two words per second, both types of related words show similarly reduced N400s, as well as varying degrees of increased posterior post-N400 positivity. These findings indicate that word form preactivation during sentence comprehension is detectable along a similar time course as semantic feature preactivation, and such processing does not necessarily require additional time beyond that afforded by near normal reading rates.

1. INTRODUCTION

There is growing consensus that the brain’s language system preactivates a variety of predictable upcoming features during sentence processing; for instance, Semantic features: Federmeier & Kutas, 1999 (categories); Altmann & Kamide, 1999 (conceptual information); Szewczyk & Schriefers, 2013 (animacy); Kwon, Sturt & Liu, 2017 (semantic classifiers); Grisoni, McCormick Miller, & Pulvermüller, 2017 (verb meaning). Grammatical gender/morphophonology: Wicha, Moreno & Kutas, 2003; Wicha, Bates, Moreno & Kutas, 2003; Wicha, Moreno & Kutas, 2004; van Berkum et al., 2005; Otten & van Berkum, 2008. Syntactic structure/features: Lau, Stroud, Plesch, & Phillips, 2006; Dikker, Rabagliati & Pylkkänen, 2009; Staub & Clifton, 2006. Perceptual attributes: Rommers, Meyer, Praamstra & Huettig, 2013. See also references herein for examples of lexical form prediction. For overviews of linguistic prediction, see Kutas, DeLong & Smith, 2011; Pickering & Gambi, 2018; Federmeier, 2007; Van Petten & Luka, 2012; Kuperberg & Jaeger, 2016; Huettig, 2015; Pickering & Garrod, 2007; DeLong, Troyer & Kutas, 2014. This agreement among researchers, however, does not extend fully to word form preactivation.

There is ongoing debate about whether the brain regularly preactivates lexical forms (orthographic or phonological features, or lexemes) associated with particular semantic information during processing of continuous language input. Ito, Corley, Pickering, Martin, & Nieuwland (2016) proposed that comprehenders might only preactivate forms of likely upcoming words when input rate is slowed such that meaning/semantic features have already been preactivated. This proposal is based on theories of comprehension in which the primary mechanism for prediction is the language production network (e.g., Pickering & Garrod, 2007, 2013; Pickering & Gambi, 2018). In these models, preactivation occurs via covert imitation, with language comprehension following the same discrete, ordered processing stages as production (e.g., Levelt, 1999). Form preactivation would be most subject to time and resource constraints because it is the final stage, with semantic/conceptual and syntactic feature preactivation necessarily occurring prior to word forms, with each processing stage requiring a few hundred milliseconds (Indefrey & Levelt, 2004). This is a proposed one-way street: for both comprehenders and producers, meaning can be preactivated without form, but not vice-versa.

To test the proposal that form preactivation is constrained by available processing time due to its dependence on semantic feature preactivation, Ito et al. (2016) used the ERP methodology in conjunction with a related anomaly paradigm to contrast processing of sentences varying in constraint and continuing with 1) predictable words, 2) unpredictable form neighbors of predictable words, 3) unpredictable words semantically related to predictable words, or 4) unpredictable words unrelated on either dimension to predictable words. Related anomaly ERP paradigms are designed to probe the activation state of the processing system by examining electrophysiological activity to unpredictable words that do not fit in a sentential context but are related in some way to predictable continuations. Although some of the strongest evidence for prediction in language processing comes from studies using online methodologies that allow for detection of prediction effects prior to the presentation of predictable words themselves, related anomaly paradigms, too, have been used to argue for prediction. Similar ERP patterns (namely, reduced amplitude N400s—a component related to ease of semantic access) for the semantic- and form-related words relative to the unrelated condition would indicate that predictable form features, as well as semantic features, were activated by the time the critical word was encountered. ERP effects to related words in the related anomaly paradigm have been widely observed in the literature, revealing different aspects of semantic memory structure (e.g., category information: Federmeier & Kutas, 1999; event knowledge: Metusalem, Kutas, Urbach, Hare, McRae & Elman, 2012; and perceptuo-motor attributes: Amsel, DeLong & Kutas, 2015). Similar N400 reductions to orthographic neighbors would suggest that activation a word’s form can also occur prior to the occurrence of a predictable word. Ito et al. (2016) observed that only at a slower rate of sentence presentation (700 ms stimulus onset asynchrony, SOA), but not at a faster 500 ms SOA, was there an N400 amplitude reduction for form neighbors (in addition to semantically related words) relative to the unrelated condition. In addition, they observed this effect only for sentences with higher constraint (mean cloze probability of predictable continuation = 93.5%), and not those with lower constraint (mean cloze probability of predictable continuation = 65.1%). They thus concluded that readers can only preactivate form information for highly predictable words when there is sufficient time first to progress through stages of semantic/conceptual feature preactivation. They took these results as support for their prediction-with-implementation model; namely, that form prediction is the final stage in a series of production-like processes, and is less likely to be reached under time or other resource constraints (Ito et al., 2016).

Ito and colleagues’ failure to observe form-related prediction at the faster input rate, however, is inconsistent with several other reports in the ERP sentence processing literature. One of these relied on the phonological feature in English whereby consonant-initial words are preceded by the indefinite article “a” and vowel-sound-initial words by “an” (DeLong, Urbach & Kutas, 2005). For sentences ranging in contextual constraint, flashed at a rate of two words per second, N400 amplitude to the indefinite articles preceding more and less predictable nouns was inversely correlated with the cloze probability for those articles, via the likelihood of upcoming nouns (e.g., The day was breezy so the boy went outside to fly a kite/an airplane …). Because a and an do not differ in their semantics (a factor that N400 amplitude is sensitive to), an ERP difference at the articles is attributable to the consistency of the article with the upcoming—but crucially not yet presented—noun. These results indicate that phonological word features can be preactivated, at least under some circumstances.

Support for word form preactivation also comes from other studies using the a/an paradigm. For instance, Martin, Thierry, Kuipers, Boutonnet, Foucart & Costa (2013), a study based on DeLong et al. (2005), similarly observed an a/an article N400 prediction effect, albeit at a slower presentation rate (700 ms SOA, as confirmed in Ito, Martin & Nieuwland, 2017). Ito, Martin & Nieuwland (2017) likewise obtained a marginally significant (p = .06) prediction N400 effect at a/an articles for native English-speaking participants (see discussion in DeLong, Urbach & Kutas, 2017). An exception to these findings is a controversial multi-lab experiment by Nieuwland et al. (2017), which reported a failed replication of the DeLong et al. study (see Yan, Kuperberg & Jaeger, 2017 and a blog post by Shravan Vasishth: https://vasishth-statistics.blogspot.com/2017/04/a-comment-on-delong-et-al-2005-nine.html for elaboration).

Critically, others, using the same basic experimental paradigm as DeLong et al. (2005), have taken their data as support for morphosyntactic prediction during sentence comprehension. These studies relied on gender-marked languages such as Spanish (Wicha, Moreno, & Kutas, 2004; Wicha, Bates, Moreno & Kutas, 2003; Foucart, Martin, Moreno & Costa, 2014) and Dutch (Van Berkum et al., 2005; Otten & Van Berkum, 2008) to show that readers and listeners preactivate specific upcoming nouns, as evidenced by amplitude modulations of ERPs to prenominal grammatical-gender-marked articles or adjectives. In these studies, the authors did not argue that comprehenders were preactivating all possible feminine or male gender nouns. Nor did they argue that prediction was strictly for syntactic/semantic features of likely upcoming words. Instead, and in line with the inference from the a/an data, they argued that neural sensitivity to determiners or adjectives with gender marking that did not align with predictable nouns implies preactivation of specific upcoming words (see Van Berkum et al., 2005, p. 461).

Support for form preactivation during language comprehension comes from a variety of other studies, as well (e.g., Dambacher, Rolfs, Göllner, Kliegl & Jacobs, 2009; Dikker, Rabagliati, Farmer & Pylkkänen, 2010; Molinaro, Barraza & Carreiras, 2013). Laszlo & Federmeier (2009), for instance, used highly constraining sentence contexts to contrast predictable words, unpredictable orthographic neighbors of predictable words and unpredictable unrelated words (three of the four conditions tested by Ito et al., 2016), along with additional pseudoword and illegal letter string conditions. Unlike Ito et al. (2016), Laszlo & Federmeier did observe N400 amplitude reductions for the orthographic neighbor condition at a 500 ms SOA. In addition, Kim & Lai (2012) reported reduced amplitude N400s for pseudowords orthographically related to predictable sentence continuations, relative to orthographically unrelated pseudowords, which exhibited larger amplitude N400s (with the related condition also showing increased positivity in an early, posterior P1 time window). There were also amplitude increases in a later P600 component for the orthographically related words/pseudowords/non-words relative to those not orthographically related. Taken altogether, these findings support comprehension models in which language context serves to generate predictions at multiple levels, including form, at relatively early time points following word onset, under a variety of conditions, apparently not as limited by time and resource availability as Ito et al. (2016) would like us to believe.

The preponderance of data to date seems to favor word form preactivation even at rates approaching normal speech/reading, at least when contextual constraint is high: Ito and colleagues’ findings represent the exceptions. In the current study, we set out to adjudicate previous findings by conducting an experiment to determine whether or not word form information can be preactivated from supportive sentence context with similar timing as semantic information. To this end, we recorded ERPs as participants read highly constraining sentence contexts at a rate of two words per second (the faster rate in Experiment 1 of Ito et al., 2016) that were continued by the same four word types as in that study: predictable words, unpredictable form (orthographic) neighbors of predictable words, unpredictable words semantically/associatively related to predictable words, and unpredictable words unrelated orthographically or semantically/associatively to predictable words. Our predictions are quite straightforward: if similar N400 reductions relative to the unpredictable unrelated words obtain for both types of related words, then it would follow that additional processing time beyond that needed to preactivate semantic information is not necessarily a requirement for word form information to be preactivated. If, on the other hand, the orthographic condition does not show an N400 reduction relative to unrelated words, then this would be inconsistent with form preactivation occurring along a similar time course as semantic preactivation. Based on previous reports, we also expect unpredictable sentence continuations orthographically related to predictable words to elicit posterior post-N400 positivities (PNPs)—a finding observed at both SOAs (500 ms and 700 ms) by Ito et al. (2016); to orthographically related words, pseudowords and illegal letter strings by Laszlo & Federmeier (2009); and to misspellings of highly predictable words (orthographically related pseudowords) by Vissers, Chwilla & Kolk (2006), as well as by Kim & Lai (2012).

2. METHOD

2.1. Stimulus materials

Experimental sentence stimuli consisted of 160 highly constraining sentence contexts (e.g., The woman stashed her wallet in her…for safety.) with sentence medial real-word noun continuations from one of four possible conditions: predictable/best completion (PRED, purse), unpredictable orthographic neighbor of predictable word (ORTH, nurse), unpredictable semantically/associatively related to predictable word (SEM, snatcher), or unpredictable unrelated to predictable word (UNREL, guest). See Supplementary Materials for the complete list of experimental stimuli. All three unpredictable continuations were selected to be implausible in their given contexts. A list of sentence contexts was assembled from previously conducted ERP studies in our lab as well as from collaborations with the Federmeier lab at UIUC (used with their permission for the current study). In all cases, best sentence continuations and their cloze probabilities were determined using standard cloze probability norming tasks. Mean cloze probability for predictable words was 94% (range 87%–100%), which also determined the contextual constraint of each context up to the critical word. Because we did not have access to the original cloze norming data/responses for all the contexts used in the current study, we were unable to calculate cloze probability values for every unpredictable word continuation; however, because unpredictable words were strategically chosen not to make sense in their given contexts, cloze probabilities are assumed to be at or very near zero.

The orthographically-related (ORTH) condition was constructed by selecting orthographic neighbors of the PRED continuations that were implausible in the sentence context. All ORTH words differed from PRED words by a single letter, with all but 2 of the 160 ORTH words having the same word length as the PRED words (the two exceptions differed in length with the addition of a single letter, ice-mice, slash-splash). A majority of the ORTH words (slightly more than half) differed from the PRED words in the first letter position (see Table 1). Critical word length across the four experimental conditions ranged from 2–10 letters (mean = 5.15, SD = 1.67). To assess form similarity, we calculated Levenshtein distance (LD) from PRED items (equal to the number of single-character insertions, deletions or substitutions needed to change one word into the other) for the different conditions. By design, ORTH words had smaller LD-from-PRED than SEM and UNREL words did, while SEM and UNREL conditions did not differ statistically from each other (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Letter position differing between predictable and orthographically related words.

| Position of differing letter, PRED vs. ORTH | Number of items |

|---|---|

| 0 (indicates differing word lengths) | 2 |

| 1 | 82 |

| 2 | 11 |

| 3 | 31 |

| 4 | 21 |

| 5 | 12 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 160 |

Table 2.

Lexical factor condition means (standard deviations).

| Cloze Probability | Word Length | Orthographic Neighborhood | Word Frequency | LSA-Pairwise with PRED | Levenshtein Distance from PRED | Plausibility Rating (1–5 scale) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRED | 94% | 4.4 (1.0) | 8.7 (5.7) | 3.4 (0.9) | 4.9 (0.2) | ||

| ORTH | ≈ 0 | 4.4 (1.0) | 9.6 (5.5) | 3.0 (0.9) | 0.10 (0.09) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.7 (0.6) |

| SEM | ≈ 0 | 5.8 (2.0) | 5.6 (6.3) | 2.7 (0.8) | 0.28 (0.19) | 5.4 (1.6) | 2.1 (0.7) |

| UNREL | ≈ 0 | 6.0 (1.8) | 3.5 (4.4) | 2.8 (0.6) | 0.07 (0.07) | 5.3 (1.6) | 1.6 (0.4) |

Table 3.

Lexical factor pairwise t-tests, t-values, df = 159.

| Length | Orthographic Neighborhood | Frequency | Pairwise Latent Semantic Analysis with PRED | Levenshtein Distance from PRED | Plausibility Rating | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORTH | 0.00, ns | 1.36, ns | 4.21*** | ||||||||||||

| SEM | 7.68*** | 7.45*** | 4.47*** | 5.74*** | 9.51*** | 3.19** | 10.42*** | 34.69*** | 4.67*** | ||||||

| UNREL | 9.69*** | 9.92*** | 1.03, ns | 9.35*** | 10.82*** | 3.64*** | 8.98*** | 2.51* | 0.83, ns | 4.40*** | 13.42*** | 34.13*** | 0.21, ns | 2.71** | 7.78*** |

| PRED | ORTH | SEM | PRED | ORTH | SEM | PRED | ORTH | SEM | ORTH | SEM | ORTH | SEM | ORTH | SEM | |

ns p > 0.05,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Semantically/associatively-related (SEM) continuations were selected by consulting entries for the PRED words from a variety of word association and word relatedness resources (including the University of South Florida Free Association Norms, Nelson et al., 1998; wordassociations.net; relatedwords.org; and onelook.com/thesaurus/). The criteria were that the SEM word should share some semantic/associative relation with the PRED word, while being implausible in the sentence context. UNREL continuations shared neither semantic/associative nor orthographic relations with PRED words and were also selected to be implausible in the sentence context. Semantic similarity of the three unpredictable conditions with the PRED words (see Table 2) was assessed using pairwise Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA, General Reading up to 1st year college, Landauer & Dumais, 1997). Comparisons (see Tables 2 and 3) indicated that, by design, SEM words had a higher LSA-with-PRED than both ORTH and UNREL words. ORTH words exhibited similar though slightly higher LSA-with-PRED than UNREL words, which we determined to be acceptable, given that the tight control kept on orthographic relatedness in the current study constrained the already limited number of candidate words available to use for the ORTH condition. This relative LSA pattern was, nonetheless, similar to that for the stimuli in Ito et al. (2016).

We also assessed item plausibility by collecting ratings for each of the four versions of the 160 sentence stimuli in a separate computerized test. Twenty-four University of California, San Diego native English-speaking student volunteers participated and were compensated with experimental credit. Sentence contexts were truncated following the critical words and were divided into 4 lists, each containing a single version of each item (40 per condition). Participants rated each item’s plausibility on a scale of 1 (completely implausible) to 5 (completely plausible). Condition plausibility ratings means are shown in Table 2. To determine any differences in plausibility, we conducted pairwise t-tests, which revealed significant effects between the three unexpected conditions: SEM > ORTH > UNREL (see Table 3). Similar to Ito et al. (2016), the SEM condition in the current study was rated as more plausible than the ORTH and UNREL conditions, which also corresponds with our anecdotal observations from other studies of participants generally rating semantically related words as more contextually plausible, despite their bad fits within their contexts: due to this rater tendency, a preference for rating SEM items as more plausible seems unavoidable. With ratings for SEM items (and much less so for ORTH items) patterning in a direction that might favor an interpretation of potential N400 amplitude reductions in terms of plausibility, we elaborate in the Discussion section on why this is unlikely.

In addition, Table 2 reports several additional lexical features of critical items, including word length, orthographic neighborhood (from www.neuro.mcw.edu/mcword), and word frequency (Lg10WF from www.ugent.be/pp/experimentele-psychologie/en/research/documents/subtlexus). Although these factors can impact language ERP measures (e.g., N400) under certain circumstances, differences between conditions on these factors were determined to be unproblematic within the design of the current experiment for the following reasons. Word length has been found not to impact N400 amplitude for sentence-medial open class words, like the critical words in our study (Van Petten & Kutas, 1990). For word frequency, although N400 amplitudes for isolated words have been found to be smaller for frequent than infrequent words, Van Petten & Kutas (1990) showed that this frequency effect interacts with sentence position, disappearing as contextual constraint builds: the mean sentence position of critical words in the current study was 11.8 words. Regarding orthographic neighborhood, with respect to the ORTH condition having a larger orthographic neighborhood than the other conditions, Laszlo & Federmeier (2011) showed that having more orthographic neighbors leads to larger, not smaller, N400 amplitude relative to words with smaller neighborhood density: this factor’s potential impact on ORTH N400 amplitude therefore would be in the opposite direction of any potential facilitation.

For ERP testing, The 640 items (160 contexts x 4 conditions each) were divided into four experimental lists, with participants seeing each context only once, and with each list containing equal numbers of items (40) from each of the four experimental conditions. Lists were constructed to minimize critical word repetition within lists. Mean sentence length was 14.1 words. One quarter of the sentences in each list (40 of 160) were followed by yes/no comprehension questions. No filler sentences were used.

2.2. ERP participants

Twenty-four UCSD undergraduate volunteers participated in the ERP experiment for course credit or cash. Participants (11 females, 13 males) were all right-handed, native English speakers with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, ranging in age from 18–23 years, with a mean age of 19.9 years. Three participants reported a left-handed or ambidextrous parent or sibling.

2.3. Offline tasks and measures

We collected several offline neuropsychological measures from individual participants, administering author and magazine recognition tests, based on Stanovich & West (1989); verbal fluency tests, letter and category (Benton & Hamsher, 1978); and a word-color Stroop interference task (based on Stroop, 1935). The purpose of collecting these data was to assess potential variability in the individual ERP results; however, they are not part of our main research question and will not be discussed further.

2.4. ERP experimental procedure

ERPs were recorded in a single session in a sound-attenuating, electrically shielded chamber. Participants sat one meter in front of a CRT monitor and read sentences for comprehension. Sentences were presented one word at a time in the center of the screen, in white type on a black background, over 8 blocks of 20 sentences each, with short breaks in between. Sentences began with a central fixation cross, on screen for a duration jittered between 1000 and 1500 ms, to orient participants to the center of the screen. This cross remained on screen during sentence presentation, with participants instructed to remain focused on it throughout the sentences. Words were presented centrally, directly above the fixation cross, for a duration of 200 ms and interstimulus interval of 300 ms (500 ms SOA). Yes/no comprehension questions appeared in their entirety on screen following one quarter of the sentences, and were responded to with one of two hand-held buttons, with response hand counterbalanced across participants and lists. If there was a question, the participant’s answer via button-press served to advance to the next sentence: if there was no question, advancement was automatic. There was a 3-second interval of blank screen between sentences. There was a brief practice session before the experimental items, during which eye movements were monitored by the experimenter and feedback given to participants. Participants were asked to remain still during testing, and to avoid blinking and moving their eyes during sentence presentation.

2.5. EEG recording parameters

The electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from 26 electrodes arranged geodesically in an Electro-cap, each referenced to an electrode over the left mastoid. Blinks and eye movements were monitored from electrodes secured on the outer canthi and under each eye, also referenced to the left mastoid process. Electrode impedances were kept below 5 KΩ. The EEG was amplified with Grass amplifiers with a pass band of 0.01 to 100 Hz and was continuously digitized at a sampling rate of 250 samples/second.

2.6. Data analysis

Single trial epochs spanning 500 ms prestimulus to 1500 ms poststimulus were extracted from the continuous EEG. Mean amplitude measurements for critical words were calculated based on ERPs time locked to stimulus onset, with baseline correction performed by subtracting the mean amplitude over the 500 ms precritical word onset. Screening for artifacts was performed by computer algorithm and confirmed by visual inspection. Artifact-contaminated trials were rejected off-line before averaging. On average, 12% of trials were eliminated. The data were re-referenced off-line to the algebraic mean of the left and right mastoids and averaged for each experimental condition, time-locked to the onset of the critical words.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to test for effects of relatedness (4 levels: PRED, ORTH, SEM, UNREL) on ERP mean amplitude measures across all 24 participants. For tests with greater than 1 degree of freedom in the numerator, results are reported with the Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity applied to p-values, and the original degrees of freedom. For the N400, a canonical time window (300–500 ms) was used. To determine a time window for measuring the posterior post-N400 positivity (PNP), analyses conducted in DeLong, Urbach, Groppe & Kutas (2011) and DeLong, Quante & Kutas (2014), as well as the late positivity time window used by Ito et al. (2016), served as guides for selecting 600–1000 ms. Both effects were measured over the 15 most posterior scalp channels, where written word N400 effects (and reported PNPs to less plausible words, see Van Petten & Luka, 2012) are generally the largest. ERP follow-up comparisons were performed with additional repeated measures ANOVAs on subsets of the data. For analysis of lexical factors, pairwise t-tests between conditions of each factor were performed and results reported in Table 3.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Behavioral results

Participants correctly answered an average of 90.9% (range 87.5 to 97.5%) of the comprehension questions. This high performance indicates participants were attending to and comprehending the experimental sentences.

3.2. ERP results

N400: 300–500 ms.

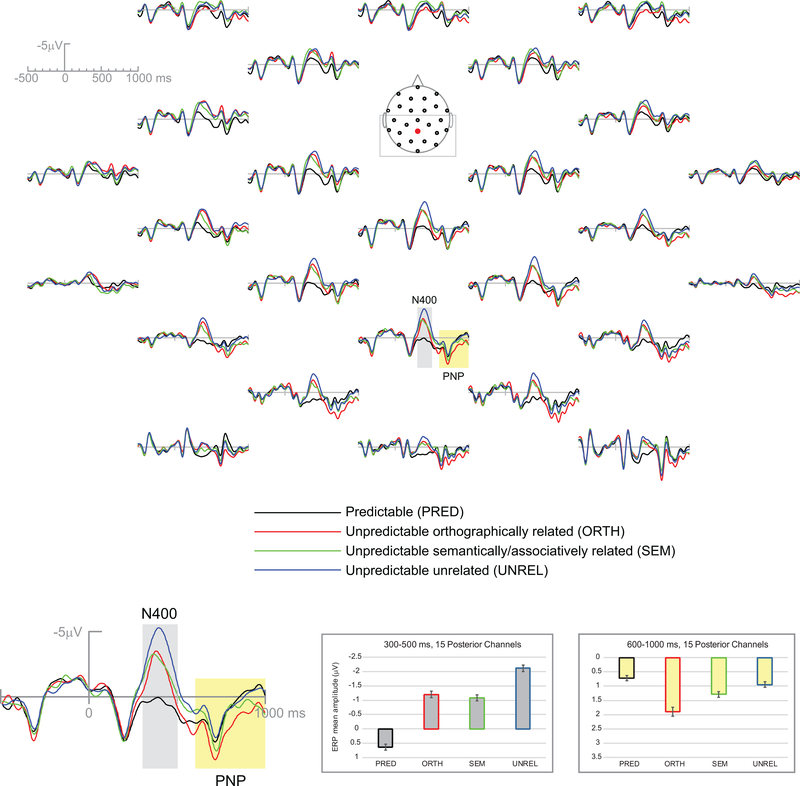

For N400 mean amplitude measures over 15 posterior channels, UNREL showed the greatest negativity (−2.12 μV) and PRED the least (0.64 μV), with ORTH (−1.20 μV) and SEM (−1.09 μV) in between. See Figure 1. ANOVAs indicated a significant effect of relatedness, [F(3, 69) = 22.47, pGG < 0.0001]. PRED elicited smaller N400s than UNREL [F(1, 23) = 43.64, p < 0.0001], replicating a standard anomaly effect. Moreover, statistical analysis revealed patterns similar to those from the literature; namely, greater negativity to SEM relative to PRED [F(1,23) = 22.99, p = 0.0001], but reduced negativity for SEM relative to UNREL [F(1, 23) = 10.94, p = 0.0031]. Of critical interest was whether the ORTH condition would exhibit a similar N400 pattern. Comparisons revealed that ORTH items indeed elicited greater negativity than PRED items [F(1, 23) = 39.10, p < 0.0001] but reduced N400 amplitude relative to UNREL items [F(1, 23) = 8.33, p = 0.0083]. The SEM and ORTH conditions did not differ significantly from each other [F(1, 23) = 0.10, p = 0.7527].

Figure 1.

Grand average (N = 24) ERPs recorded over 26 scalp channels, negative voltage plotted up. The boxed area on the schematic scalp diagram indicates the 15 posterior electrodes included in the N400 and posterior PNP statistical analyses. The midline parietal electrode is highlighted in red, and ERPs for that channel are enlarged at the bottom left panel. The N400 analysis time window (300–500 ms) is highlighted in gray and the posterior PNP time window (600–1000 ms) in yellow. Bar plots of the mean amplitude measures for the conditions in these two time windows are shown, with error bars indicating SEM.

Posterior PNP: 600–1000 ms.

The posterior PNP analysis revealed a significant effect of relatedness, [F(3,69) = 3.55, pGG = 0.0368], with ORTH showing the greatest positivity (1.89 μV), followed by SE M (1.29 μV), UNREL (0.95 μV), and then PRED (0.73 μV). See Figure 1. Pairwise testing indicated that the ORTH condition was significantly more positive than both PRED [F(1, 23) = 5.85, p = 0.0239] and UNREL [F(1, 23) = 4.81, p = 0.0386], but that ORTH and SEM conditions did not differ [F(1, 23) = 1.60, p = 0.2183]. The SEM condition was marginally more positive than PRED [F(1, 23) = 4.22, p = 0.0516] but did not differ from UNREL [F(1, 23) = 2.11, p = 0.1599]. UNREL and PRED did not differ significantly from each other [F(1, 23) = 0.48, p = 0.4947].

Summary.

For the N400 analysis, both the SEM and the ORTH conditions showed similar reductions in N400 amplitude relative to the UNREL condition. In the posterior PNP analysis, ORTH items exhibited the greatest positivity, PRED and UNREL the least, and SEM in between.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study sought to determine whether readers may preactivate word forms during sentence comprehension, in a manner and time course similar to what has been demonstrated for preactivation of semantic features. To test this, ERPs were recorded as young adults read highly constraining sentence contexts continued by highly predictable words or unpredictable words either related (semantically/associatively or orthographically) or not to predictable continuations. N400 amplitude reductions observed to both semantically/associatively- and orthographically-related words indicate that at a reading rate of two words per second, word forms as well as semantic features are preactivated, at least in highly constraining sentence contexts. These results contrast with those of Ito et al. (2016), who did not observe N400 amplitude reductions to form-related words at the same moderate presentation rate. In addition, our ERP results in a later PNP time window (600–1000 ms) revealed an enhanced positivity over posterior sites that was largest to the orthographically related condition, but also was enhanced to the semantically/associatively related condition, relative to the predictable continuations. This positivity was also observed by Ito et al. (2016) for form-related words at both their faster and slower presentation rates, as well as by Laszlo & Federmeier (2009) and Kim & Lai (2012) to orthographically-related continuations at reading rates of one word every 500 ms and 550 ms, respectively.

Our finding of N400 amplitude reduction to orthographic neighbors of predictable sentence continuations is consistent with a majority of ERP studies that have tested for form prediction at similar presentation rates. These results have obtained across different paradigms, involving both real and pseudo-words, and with varying tasks (e.g., participants in Laszlo & Federmeier, 2009, indicated after each item whether or not it was a “normal English sentence”). Ito et al. (2016) thought that such results may not generalize to studies using only real words and with no task beyond sentence comprehension. They surmised that their failure to observe N400 amplitude reduction to the form-related condition at a 500 ms SOA may have been due in part to these experimental differences. However, as the present study also used only real words and had no task beyond occasional comprehension questions, these factors cannot be the adjudicating ones for observing word form preactivation. The current results demonstrate that at a rate approaching that of normal reading, at least under conditions of high constraint, the brain can preactivate both the form and meaning of words by the time critical words are encountered. This does not imply that there is no limit on the input rate at which word form prediction can be detected; however, based on the current study, such a limit does not appear to be 2 words per second, as Ito et al. concluded.

In a recent paper investigating phonological prediction in native and non-native speakers, Ito, Pickering & Corley (p. 9, 2018) argued that “L1 speakers appear to predict specific phonological information associated with highly predictable words, but L2 speakers do not…this evidence suggests a limitation to phonological prediction, and is compatible with the suggestion that phonological prediction may not always occur.” Rather than considering phonological prediction as all-or-none, we propose that word form preactivation may be a process inherent in constructing sentence representations, akin to preactivation of semantic or syntactic features. It has been evidenced in graded measurements (DeLong et al., 2005) and can be noted on similar time scales as (and may perhaps even prove dissociable from) other forms of preactivation. Sometimes word form preactivation levels may be weak (and difficult to detect), due to any number of factors including: the language input (e.g., more or less constraining contexts, the likelihood of encountering predictable/plausible continuations within a stimulus set); the environmental context (e.g., the source of the input—a speaker’s social status, gender, or age); or based on individual comprehender differences (e.g., age, verbal fluency level, first or second language, expertise or general knowledge level, mood, attention level, etc.). We do not dispute preactivation of semantic features as a potential trigger for specific word form preactivation during sentence comprehension, but this may not be the only path (e.g., consider word co-occurrence, associations, phonological constraints). The sequenced stages of production-like comprehension advanced by the prediction-with-implementation model seem to assume a process by which a form representation is converged upon near the time point when it is most likely to be encountered (given Ito et al.’s finding that 700 ms, but not 500 ms, afforded enough time to preactivate form), but only with sufficient contextual constraint, available time, and in populations exhibiting an abundance of processing resources. Another possibility, however, is that word form preactivation occurs routinely and continuously during language comprehension, potentially for multiple word forms at a time, in some cases without “anticipatory neural commitment” to any one form, possibly depending on the nature of the context (see Molinaro, Barraza & Carreiras, 2013).

One proposal by Pickering & Gambi (2018), who have detailed a prediction-by-production model of language comprehension, is that there may be an additional prediction mechanism available to comprehenders which is not based on language production networks. This mechanism is not subject to the timing constraints and availability of cognitive resources that are required to proceed through the semantic and syntactic stages for word form prediction via production-like processing. This other form of preactivation is presumed to be resource-free and largely unconstrained by specifics of the linguistic context, and involves spreading activation. On this view, linguistic representations can activate networks of related items (semantically, associatively or phonologically, per Pickering & Gambi, 2018) and the flow of activation need not be directional. This prediction-by-association proposal is compatible with the pattern of results observed in the current study, as well as results from other related anomaly studies (e.g., Metusalem et al, 2012; Amsel et al., 2015; Laszlo & Federmeier, 2009) in which implausible but related word continuations show the kinds of processing benefits that are not readily explained on a prediction-by-production account.

In this way, words in a sentence—through their meanings and associations—activate other words. For instance, at sentence beginnings (as for isolated words) associations may be the primary means for comprehenders to preactivate likely upcoming continuations. As sentences unfold and words combine and interact with stored knowledge and experiences, various events/schemas may be activated. Preactivation for multiple not-(yet)-encountered words’ features or forms may summate or decay as context modulates the likelihood of certain information being encountered. These richer contextual-, event- or schema-based activations may be activated by single words, or they may take time to build up in a sentence, and until they do, there may potentially be more reliance on a prediction-by-association based mechanism. The interaction of prediction-by-production and prediction-by-association is outlined to some degree by Pickering & Gambi (2018). As an example, when reading ‘The day was breezy so the boy went outside to fly a kite in the park’, there may be some preactivation for kite when readers reach breezy, and an increase after boy and yet more after outside, and by fly it is highly likely that kite will soon be encountered. Between content words, it is possible that activation for kite’s features diminishes if a comprehender’s contextual representation shifts transiently to a different likelihood model (maybe breezy brings to mind sailing, or opening the windows or hanging out laundry; but a boy being involved with laundry may be unlikely; and going outside further delimits the kinds of activities that boys typically do on breezy days, etc.). The path to strong preactivation of the word form kite may therefore not be a linear one, likely varying at different time points, perhaps even peaking temporarily at other potential noun slots (e.g., …breezy so the ____). As the sentence unfolds, the prediction-by-production mechanism may (or may not) begin playing a greater role, with syntactic/phonological cues (like a/an) signaling if or when, precisely, kite may occur. But not until the article a do the syntax and conceptual-semantic representation converge to afford a slot where kite is a good fit. DeLong et al. (2005) showed that by the time the article a or an was presented, readers already seemed to expect that the word form kite would follow. The current study aligns with this interpretation by showing that even a word that makes no sense in the sentence context (bite) is easier to process when its word form overlaps with the predictable continuation (kite) than when it does not (harvest).

In the current study we have demonstrated that comprehenders are capable of preactivating word forms during continuous sentence comprehension and that this is detectable in the ERP signal to the critical words. To date, most support for form preactivation comes from studies utilizing highly constraining contexts, although DeLong et al. (2005) used a range of sentential constraint and observed graded word form preactivation. Additionally, input rates of two words per second have generally constituted the upper limit for observing such effects, although preactivation findings from prenominal grammatical gender studies (e.g., Wicha et al., 2003 and Van Berkum et al., 2005) were obtained with spoken language, which is generally faster than RSVP of written words. Results from experimental designs testing for prediction at prenominal words have generally yielded small ERP effects, indicating that such patterns may be difficult to detect, particularly across groups of comprehenders. However, this does not necessarily mean that individuals are not preactivating various kinds of information: they may just do so more weakly or with less consistency when the ERPs are being measured to closed class words such as prenominal determiners or gender-marked suffixes. We do not argue that preactivation is necessary for comprehension, but rather would frame it as one of the automatic processes that aids in meaning construction, which is used with ultimately more or less “success” under various circumstances and with greater efficiency by certain individuals. We contend that there may be instances (e.g., with L2 comprehenders), where connections in the language network are not strong enough to facilitate rapid word form activation (or maintenance over the course of a sentence) or where slower processing or diminished verbal fluency (e.g., for older adults) may not activate word forms in time to reveal evidence of successful prediction (e.g., DeLong, Groppe, Urbach & Kutas, 2012; Federmeier, Kutas & Schul, 2010). After all, once confirmatory input is received, preactivation (prediction) ceases being preactivation and simply looks like activation. In sum, prediction (preactivation) is a mechanism and not an outcome, and the current findings (among others) suggest 1) that word forms can be preactivated when sentences are processed at a rate as fast as 2 words per second, and 2) that either form preactivation can occur via a mechanism other than the language production network, or advancing to the phonology/orthography stage under a prediction-by-production model can occur more rapidly than has been argued by Ito et al. (2016).

The question remains as to why Ito et al. (2016)—a study very much like the current one—failed to observe word form preactivation at a presentation rate of two words per second. It is worth examining differences between the two studies that could play a role and potentially elucidate the limiting factors for detecting form preactivation. One observation is that Ito et al. utilized a narrower time window for N400 analysis (350–450 ms) compared to ones used in the current study (300–500 ms), by Laszlo & Federmeier (250–450 ms), by Kim & Lai (300–500 ms), and indeed more generally across language N400 studies. This measurement choice may have limited their ability to capture N400 differences between the form-related and unrelated conditions occurring before and after the peak of the N400, which is hinted at in their Figure 1 (high cloze items), but is impossible to assess given only the single channel ERP plot presented.

Another possibility could relate to the overall proportion of plausible to implausible items in the two studies. With their use of filler sentences, 46% of items read by participants in Ito et al. were continued by plausible, correctly spelled real words (although neither the constraint nor cloze probability for the filler sentences/continuations was provided, making it impossible to determine the overall proportion of predictable continuations), compared to 25% in the current study, as well as in both Kim & Lai (2012) and Laszlo & Federmeier (2009). However, it is not obvious why a higher proportion of “normal” sentences might lead to weaker word form prediction. Indeed, this would run contrary to findings from Brothers, Swaab & Traxler (2017), which suggests that a higher proportion of more predictable than nonpredictable sentence continuations would lead to stronger, not weaker, prediction. The filler sentences included in Ito et al. (2016) also led to a slightly lower proportion of ORTH items than the current study (18% v. 25%), but it is not clear that such a small difference would have made the manipulation any more or less noticeable by participants in one study than the other.

Another difference is that average sentence length is slightly longer in the current study (14.1 words) compared to Ito et al. (10.8 words), and the average critical word position slightly later (word 11.8, 9.8, respectively). It is possible that receiving more context (over a longer time interval) prior to critical words could lead to increased preactivation. As cloze probability tests rarely consider the time taken by participants to provide responses (although see Staub, Grant, Astheimer & Cohen, 2015), equivalent cloze probability values do not necessarily take into account the ease or difficulty of arriving at any given cloze response, even if an item’s cloze probability in the end turns out to be quite high (good convergence across participants).

Other differences between the two studies relate to some of the lexical properties of the experimental stimuli. For instance, All ORTH items in the current study differed by a single letter (Levenshtein Distance, LD = 1) from PRED items. In contrast, although a majority of form-related words from the Ito et al. study (80% overall and 77% of the high cloze items) similarly differed by a single letter from the predictable words, a subset did not, resulting in weaker overall form relatedness. It is unclear the degree to which this difference may have impacted form-related N400s; however, in principle, it is possible that the difference contributed to the absence of form-related N400 reduction in Ito et al.’s study, and the observation of such an effect in our study and others. Even if that is the case, the fact remains that we and others observe reliable ERP modulations at a 500 ms SOA presentation rate, consistent with form prediction when orthographic distance is controlled, as it was in the current study, in Laszlo & Federmeier (2011), and in Kim & Lai (2012).

For our own data, we can rule out contributions of other lexical factors on N400 amplitude reductions for the ORTH and SEM conditions relative to UNREL. For instance, although ORTH items were found to be slightly more semantically related to PRED items than were UNREL words (pairwise-LSA-with-PRED was 0.10 vs. 0.07, respectively)—a factor associated with N400 amplitude reduction—a single-trial analysis showed that such a small LSA difference between ORTH and UNREL with PRED would have had negligible impact on the ORTH N400. By comparison, the mean N400 reduction for the SEM condition relative to UNREL (a 1.03 μV effect, similar in amplitude to the 0.92 μV ORTH effect)—was driven by a semantic relation nearly three times larger (pairwise-LSA-with-PRED for SEM items was 0.28).

One last argument that might be raised regarding our finding of reduced N400 amplitudes for the ORTH and SEM conditions, is that these effects stemmed from somewhat higher mean plausibility ratings for those conditions relative to UNREL (See Tables 2 and 3). However, the literature does not support the idea that the N400 routinely or directly indexes an item’s plausibility in context; in fact, there is a good deal of evidence to the contrary. For instance, Federmeier & Kutas (1999) showed that N400 amplitude reductions to words semantically related to predictable sentence continuations were larger for sentences that were rated more implausible than for those rated less implausible. Urbach & Kutas (2010) also showed that in quantifier sentences (e.g., “Few farmers grow crops/worms…”), N400 amplitude did not pattern with the plausibility of more and less typical sentential objects. Along the same lines, Fischler et al. (1983) showed the same lack of a plausibility/N400 amplitude relationship in sentences employing negation. Kuperberg (2007), too, describes data in which N400 amplitudes did not differ as a function of plausibility when typically ordered sentences were contrasted to those with thematic role reversals (“For breakfast the boys would only eat…” vs. “For breakfast the eggs would only eat…”). These findings leave little reason to believe that the N400 reductions to ORTH and SEM relative to UNREL items are indexing ease of integration in terms of their plausibility, instead of preactivation based on the experimental manipulation of form and semantic information.

In addition to evidence for word form preactivation based on N400 data, there was also a finding of increased late positivity over posterior scalp sites (a posterior PNP effect) that was largest to the orthographically related condition but also present to a lesser extent to semantically/associatively-related words, relative to the predictable continuations. This, too, differed from Ito et al. (2016), who reported a similar late posterior positivity in high constraint contexts at both the 500 ms and 700 ms SOAs, but only to the form-related condition. It is worth noting then that whatever the processing being indexed by this late effect, it may not be exclusive to form/orthographic relatedness. This would rule out an interpretation relating specifically to detection of perceived misspellings, for instance. Additionally, there was no posterior PNP difference between the predictable and unrelated (implausible) unpredictable condition—a condition for which such an effect might have been predicted (see Thornhill & Van Petten, 2012), based on our observations of effects to similar anomalous conditions in previous work (in DeLong, Quante & Kutas, 2014, we distinguished a posterior PNP to implausible continuations of highly constraining contexts from a more anterior PNP to plausible, but still unpredictable, continuations). The functional significance of the posterior PNP (or P600 or late positive component, as it is sometimes known) is not clear. Once thought to be related to syntactic processing, it is now considered to reflect more generalized processing. It has been observed to vary with integration difficulty (Brouwer, Fitz & Hoeks, 2012); conflict resolution (Vissers, Chwilla & Kolk, 2006); language monitoring (Kolk, Chwilla, Van Herten & Oor, 2003); and memory retrieval (see Van Petten & Luka, 2012). It has been proposed to relate to processes such as revision and repair when unpredicted input is encountered (Kuperberg & Wlotko, 2018). The posterior PNP/P600’s proposed relation to another ERP, the P3b, has also raised the possibility that it, too, may similarly be affected by the relevance of particular stimuli depending on experimental task (explicitly specified or implicitly perceived by participants. See Van Petten & Luka, 2012, for a review). It is possible that the decreasing posterior PNP amplitudes (ORTH>SEM>UNREL> PRED) to the conditions in our experiment could correspond with decreasing amounts of conflict resolution or monitoring required to correctly detect and/or integrate the critical word into a revised sentence representation when a word other than the most likely one is encountered. Alternately, the graded nature of the posterior PNP amplitude may be reflecting processing modulated by the saliency of the conditions in our study. We note that Ito et al.’s (2016) use of plausible filler items led to a different proportion of plausible to implausible sentences over the experiment, which may have potentially led to the different ERP patterns for this late positivity.

4.1. Conclusions

The current study, including only real words and with no experimental task other than answering occasional comprehension questions, confirmed that individuals reading highly constraining sentences can preactivate not only semantic features of predictable words but also the word forms themselves. Importantly, the brain’s response to these two different types of neural prediction was evident in the same N400 time window (considered a relatively early sign of semantic processing), and occurred when sentences were presented at a rate approaching that of normal reading (as opposed to only at slower input rates or with introduced delays). Although these findings do not discount a prediction-by-production account (since comprehenders could still preactivate both the semantics and form of predictable words well before encountering a predictable word—see Pickering & Gambi, 2018) they do argue against the proposal that lexical form prediction is time constrained in the manner outlined by Ito et al. (2016). The argument they present is the following:

Ito el al. (2016), pg. 169: “If similar effects of meaning and form preactivation had been obtained at both SOAs, it would have suggested that participants pre-activated a specific lexical item (i.e., lemma) first, wherefrom the activation spread across semantically and form-related lemmas. If this were the case, the pre-activation pattern would have been incompatible with a prediction-with-implementation account.”

Under this logic, then, the current finding of form preactivation at the 500 ms SOA would be incompatible with their prediction-by-implementation account. However, this is a stronger statement than we wish to make. Although the current study offers no evidence against a prediction-by-production account, it also offers no evidence for staged, unidirectional processing laid out by prediction-by-production models. We propose that word form prediction (preactivation) is a mechanism and not an outcome, and that there are reasons why linguistic form prediction may not be easy to detect. In combination with data from a variety of experiments using pseudowords, non-words and real words, as well as paradigms designed to detect lexical prediction at time points prior to critical word presentation, the current study offers one more piece of evidence that sentential context can trigger in advance not only broad classes of feature information, but also quite detailed information; namely, specific word forms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by NICHD Grant R01HD22614 to MK.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication, and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

REFERENCES

- Altmann GT, & Kamide Y (1999). Incremental interpretation at verbs: Restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition, 73(3), 247–264. 10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00059-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsel BD, DeLong KA, & Kutas M (2015). Close, but no garlic: Perceptuomotor and event knowledge activation during language comprehension. Journal of memory and language, 82, 118–132. 10.1016/j.jml.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL & Hamsher K (1978). Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City: University of Iowa Hospitals. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers T, Swaab TY, & Traxler MJ (2017). Goals and strategies influence lexical prediction during sentence comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 93, 203–216. 10.1016/j.jml.2016.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer H, Fitz H, & Hoeks J (2012). Getting real about semantic illusions: rethinking the functional role of the P600 in language comprehension. Brain research, 1446, 127–143. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambacher M, Rolfs M, Göllner K, Kliegl R, & Jacobs AM (2009). Event-related potentials reveal rapid verification of predicted visual input. PLoS One, 4(3), e5047 10.1371/journal.pone.0005047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA (2009). Electrophysiological explorations of linguistic preactivation and its consequences during online sentence processing. University of California, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA, Groppe DM, Urbach TP, & Kutas M (2012). Thinking ahead or not? Natural aging and anticipation during reading. Brain and language, 121(3), 226–239. 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA, Quante L, & Kutas M (2014). Predictability, plausibility, and two late ERP positivities during written sentence comprehension. Neuropsychologia, 61, 150–162. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA, Troyer M, & Kutas M (2014). Pre‐processing in sentence comprehension: Sensitivity to likely upcoming meaning and structure. Language and Linguistics Compass, 8(12), 631–645. 10.1111/lnc3.12093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA, Urbach TP, & Kutas M (2005). Probabilistic word preactivation during language comprehension inferred from electrical brain activity. Nature neuroscience, 8(8), 1117 10.1038/nn1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong KA, Urbach TP, & Kutas M (2017). Is there a replication crisis? Perhaps. Is this an example? No: a commentary on Ito, Martin, and Nieuwland (2016). Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 32(8), 966–973. 10.1080/23273798.2017.1279339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delong KA, Urbach TP, Groppe DM, & Kutas M (2011). Overlapping dual ERP responses to low cloze probability sentence continuations. Psychophysiology, 48(9), 1203–1207. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01199.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikker S, Rabagliati H, & Pylkkänen L (2009). Sensitivity to syntax in visual cortex. Cognition, 110(3), 293–321. 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikker S, Rabagliati H, Farmer TA, & Pylkkänen L (2010). Early occipital sensitivity to syntactic category is based on form typicality. Psychological Science, 21(5), 629–634. 10.1177/0956797610367751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier KD (2007). Thinking ahead: The role and roots of prediction in language comprehension. Psychophysiology, 44(4), 491–505. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00531.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier KD, & Kutas M (1999). A rose by any other name: Long-term memory structure and sentence processing. Journal of memory and Language, 41(4), 469–495. 10.1006/jmla.1999.2660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier KD, Kutas M, & Schul R (2010). Age-related and individual differences in the use of prediction during language comprehension. Brain and language, 115(3), 149–161. 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischler I, Bloom PA, Childers DG, Roucos SE, & Perry NW (1983). Brain potentials related to stages of sentence verification. Psychophysiology, 20, 400–409. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1983.tb00920.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucart A, Martin CD, Moreno EM, & Costa A (2014). Can bilinguals see it coming? Word anticipation in L2 sentence reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40(5), 1461 10.1037/a0036756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisoni L, Miller TM, & Pulvermüller F (2017). Neural correlates of semantic prediction and resolution in sentence processing. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(18), 4848–4858. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2800-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettig F (2015). Four central questions about prediction in language processing. Brain Research, 1626, 118–135. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indefrey P, & Levelt WJ (2004). The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition, 92(1–2), 101–144. 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Corley M, Pickering MJ, Martin AE, & Nieuwland MS (2016). Predicting form and meaning: Evidence from brain potentials. Journal of Memory and Language, 86, 157–171. 10.1016/j.jml.2015.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Martin AE, & Nieuwland MS (2017). How robust are prediction effects in language comprehension? Failure to replicate article-elicited N400 effects. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 32(8), 954–965. 10.1080/23273798.2016.1242761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Pickering MJ, & Corley M (2018). Investigating the time-course of phonological prediction in native and non-native speakers of English: A visual world eye-tracking study. Journal of Memory and Language, 98, 1–11. 10.1016/j.jml.2017.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A, & Lai V (2012). Rapid interactions between lexical semantic and word form analysis during word recognition in context: Evidence from ERPs. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 24(5), 1104–1112. 10.1162/jocn_a_00148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolk HH, Chwilla DJ, Van Herten M, & Oor PJ (2003). Structure and limited capacity in verbal working memory: A study with event-related potentials. Brain and language, 85(1), 1–36. 10.1016/S0093-934X(02)00548-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR (2007). Neural mechanisms of language comprehension: Challenges to syntax. Brain research, 1146, 23–49. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, & Jaeger TF (2016). What do we mean by prediction in language comprehension? Language, cognition and neuroscience, 31(1), 32–59. 10.1080/23273798.2015.1102299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg G, & Wlotko E (2018). A Tale of Two Positivities (and the N400): Distinct neural signatures are evoked by confirmed and violated predictions at different levels of representation. bioRxiv, 404780 10.1101/404780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, DeLong KA, & Smith NJ (2011). A look around at what lies ahead: Prediction and predictability in language processing. Predictions in the brain: Using our past to generate a future, 190207 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195395518.003.0065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon N, Sturt P, & Liu P (2017). Predicting semantic features in Chinese: Evidence from ERPs. Cognition, 166, 433–446. 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer TK, & Dumais ST (1997). A solution to Plato’s problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychological review, 104(2), 211 10.1037/0033-295X.104.2.211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo S, & Federmeier KD (2009). A beautiful day in the neighborhood: An event-related potential study of lexical relationships and prediction in context. Journal of Memory and Language, 61(3), 326–338. 10.1016/j.jml.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo S, & Federmeier KD (2011). The N400 as a snapshot of interactive processing: Evidence from regression analyses of orthographic neighbor and lexical associate effects. Psychophysiology, 48(2), 176–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau E, Stroud C, Plesch S, & Phillips C (2006). The role of structural prediction in rapid syntactic analysis. Brain and language, 98(1), 74–88. 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJ, Roelofs A, & Meyer AS (1999). A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behavioral and brain sciences, 22(1), 1–38. 10.1017/S0140525X99001776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CD, Thierry G, Kuipers JR, Boutonnet B, Foucart A, & Costa A (2013). Bilinguals reading in their second language do not predict upcoming words as native readers do. Journal of Memory and Language, 69(4), 574–588. 10.1016/j.jml.2013.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medler DA, & Binder JR (2005). MCWord: An On-Line Orthographic Database of the English Language. http://www.neuro.mcw.edu/mcword/

- Metusalem R, Kutas M, Urbach TP, Hare M, McRae K, & Elman JL (2012). Generalized event knowledge activation during online sentence comprehension. Journal of memory and language, 66(4), 545–567. 10.1016/j.jml.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro N, Barraza P, & Carreiras M (2013). Long-range neural synchronization supports fast and efficient reading: EEG correlates of processing expected words in sentences. NeuroImage, 72, 120–132. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DL, McEvoy CL, & Schreiber TA (1998). The University of South Florida word association, rhyme, and word fragment norms. http://www.usf.edu/FreeAssociation/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nieuwland MS, Politzer-Ahles S, Heyselaar E, Segaert K, Darley E, Kazanina N, … & Mézière D (2018). Large-scale replication study reveals a limit on probabilistic prediction in language comprehension. eLife, 7, e33468 10.7554/eLife.33468.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten M, & Van Berkum JJ (2008). Discourse-based word anticipation during language processing: Prediction or priming? Discourse Processes, 45(6), 464–496. 10.1080/01638530802356463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, & Gambi C (2018). Predicting while comprehending language: A theory and review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(10), 1002–1044. 10.1037/bul0000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, & Garrod S (2007). Do people use language production to make predictions during comprehension? Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(3), 105–110. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, & Garrod S (2013). An integrated theory of language production and comprehension. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(4), 329–347. 10.1017/S0140525X12001495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommers J, Meyer AS, Praamstra P, & Huettig F (2013). The contents of predictions in sentence comprehension: Activation of the shape of objects before they are referred to. Neuropsychologia, 51(3), 437–447. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, & West RF (1989). Exposure to print and orthographic processing. Reading Research Quarterly, 402–433. 10.2307/747605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staub A, & Clifton C Jr (2006). Syntactic prediction in language comprehension: Evidence from either… or. Journal of experimental psychology: Learning, memory, and cognition, 32(2), 425 10.1037/0278-7393.32.2.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub A, Grant M, Astheimer L, & Cohen A (2015). The influence of cloze probability and item constraint on cloze task response time. Journal of Memory and Language, 82, 1–17. 10.1016/j.jml.2015.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology, 18(6), 643 10.1037/h0054651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk JM, & Schriefers H (2013). Prediction in language comprehension beyond specific words: An ERP study on sentence comprehension in Polish. Journal of Memory and Language, 68(4), 297–314. 10.1016/j.jml.2012.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill DE, & Van Petten C (2012). Lexical versus conceptual anticipation during sentence processing: Frontal positivity and N400 ERP components. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 83(3), 382–392. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach TP, & Kutas M (2010). Quantifiers more or less quantify on-line: ERP evidence for partial incremental interpretation. Journal of Memory and Language, 63(2), 158–179. 10.1016/j.jml.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkum JJ, Brown CM, Zwitserlood P, Kooijman V, & Hagoort P (2005). Anticipating upcoming words in discourse: evidence from ERPs and reading times. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31(3), 443 10.1037/0278-7393.31.3.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petten C & Kutas M (1990). Interactions between sentence context and word frequency in event-related brain potentials. Memory & Cognition, 18(4), 380–393. 10.3758/BF03197127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petten C, & Luka BJ (2012). Prediction during language comprehension: Benefits, costs, and ERP components. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 83(2), 176–190. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasishth Shravan. (2017, April 1). Nieuwland et al replication attempts of DeLong at al. 2005. Retrieved from: https://vasishth-statistics.blogspot.com/2017/04/

- Vissers CTW, Chwilla DJ, & Kolk HH (2006). Monitoring in language perception: The effect of misspellings of words in highly constrained sentences. Brain Research, 1106(1), 150–163. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NY, Bates EA, Moreno EM, & Kutas M (2003). Potato not Pope: human brain potentials to gender expectation and agreement in Spanish spoken sentences. Neuroscience letters, 346(3), 165–168. 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00599-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NY, Moreno EM, & Kutas M (2003). Expecting gender: An event related brain potential study on the role of grammatical gender in comprehending a line drawing within a written sentence in Spanish. Cortex, 39(3), 483–508. 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70260-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NY, Moreno EM, & Kutas M (2004). Anticipating words and their gender: An event-related brain potential study of semantic integration, gender expectancy, and gender agreement in Spanish sentence reading. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 16(7), 1272–1288. 10.1162/0898929041920487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M (1988). MRC psycholinguistic database: Machine-usable dictionary, version 2.00. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers, 20(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Kuperberg GR, & Jaeger TF (2017). Prediction (Or Not) During Language Processing. A Commentary On Nieuwland et al.(2017) And Delong et al.(2005). bioRxiv, 143750 10.1101/143750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.