Abstract

Genome-wide identification of Insertion/Deletion polymorphisms (InDels) in Capsicum spp. was performed through comparing whole-genome re-sequencing data from two Capsicum accessions, C. annuum cv. G29 and C. frutescens cv. PBC688, with the reference genome sequence of C. annuum cv. CM334. In total, we identified 1,664,770 InDels between CM334 and PBC688, 533,523 between CM334 and G29, and 1,651,856 between PBC688 and G29. From these InDels, 1605 markers of 3–49 bp in length difference between PBC688 and G29 were selected for experimental validation: 1262 (78.6%) showed polymorphisms, 90 (5.6%) failed to amplify, and 298 (18.6%) were monomorphic. For further validation of these InDels, 288 markers were screened across five accessions representing five domesticated species. Of these assayed markers, 194 (67.4%) were polymorphic, 87 (30.2%) monomorphic and 7 (2.4%) failed. We developed three interspecific InDels, which associated with three genes and showed specific amplification in five domesticated species and clearly differentiated the interspecific hybrids. Thus, our novel PCR-based InDel markers provide high application value in germplasm classification, genetic research and marker-assisted breeding in Capsicum species.

Introduction

Desirable as both vegetable and spice, pepper (Capsicum spp. L.), native to South and Central America, is an economically important genus in Solanaceae family1,2. Thirty-one species in the genus Capsicum have been identified3. Among these, five have been domesticated including C. annuum, C. chinense Jacq., C. baccatum, C. pubescens Ruiz & Pavon and C. frutescens4,5. C. annuum is the predominant species planted around the world, and together with closely related C. chinense and C. frutescens, is part of what has been described known as the C. annuum complex6. A comparison of morphological traits has been the traditional approach for determining genotypes and assessing genetic diversity7. Nevertheless, phenotypic evaluation is easily affected by environmental factors and is not an accurate method for identification of closely related genotypes8,9. More recently, application of DNA markers has allowed for better discrimination among the species in existing complexes10–12. In multiple crops, DNA markers have played a vital role in DNA fingerprinting, genetic diversity analysis, as well as variety identification and marker-assisted breeding13–16.

During the last several decades, the molecular DNA markers of Capsicum have experienced three stages of development as in other organisms9. As the first and second-generation DNA markers, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), simple sequence repeats (SSR) and their derived methods have been extensively applied to a variety of genetic studies in pepper17–24. More recently, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion/deletion polymorphism (InDels), have become more commonly applied as the third-generation markers in pepper9,25–27.

Compared with the requirement of special equipment system for SNP detection28, codominant InDels technology is user-friendly and indeed advantageous in some genetic analyses, especially in marker-assisted selection (MAS) breeding9,29,30. With the development and decreasing cost of the second and third generation sequencing technology, InDels have been identified and developed extensively through re-sequencing and have become a valuable resource for the study of various organism, especially plants and animals30–33. The publication of pepper genomic date has provided an important platform for the detection and development of genome-wide InDels2,34. In Capsicum, multiple genetic maps were constructed with InDels based on intraspecific or interspecific populations9,27,33. In addition, InDels markers were used for QTL analysis in pepper, such as CMV resistance and initiation of flower primordia25,28. However, discovery efforts for InDels have lagged significantly behind those for SNPs, and relatively few InDels have been developed and applied in pepper28,35,36, nor have they been used with any frequency for pepper variety characterization or germplasm diversity assessment.

The purpose of the present study was to discover and develop stable and practical InDels based on re-sequencing data from C. annuum cv. G29 and C. frutescens cv. PBC688, as compared to a reference genome sequence, which could be detected with simple procedures based on size separation. Furthermore, identified polymorphic InDels among five domesticated species including two re-sequencing accessions and five additional ones. These reliable polymorphic InDels will become a useful resource for the Capsicum species identification, genetic relationship analysis and hybridization studies.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Two pepper lines C. annuum cv. G29 and C. frutescens cv. PBC688 were selected for re-sequencing in this study. The former is a sweet line ssceptible to CMV, but with excellent horticultural traits, while the latter represents a wild small-fruited hot accession highly resistant to CMV. Among the 176 accessions introduced by Dr. W.P Diao from the National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2015, we selected 63 accessions representing five domesticated species of Capsicum (Table 1). Five accessions each representing one domesticated species: PI 224408 (2), PI 439512 (15), PI 441620 (24), PI 441539 (46), and PI 585277 (59) were carefully chosen for InDel polymorphism validation of inter-species together with G29 and PBC688. Two C. annuum accessions, G29 and G43, together with two C. frutescens PBC688 and PI 439512 (15) were tested for InDel intra-species polymorphism. All 63 accessions were used for validation of inter-species InDel polymorphism.

Table 1.

The 63 accessions representing 5 domesticated species of Capsicum.

| Serial | Accession ID | Accession name | Origin | Source | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PI 194881 | EBONY | United States, New York | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 2 | PI 224408 | No.1546 | Mexico | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 3 | Grif 9108 | BG-639 | Mexico | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 4 | PI 368479 | GREKA PIPERKA II | Former Serbia and Montenegro | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 5 | PI 260449 | COL NO 187 | Argentina | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 6 | PI 338490 | Bulgaria | NPGS | C. annuum | |

| 7 | PI 592831 | SWEET CHOCOLATE | United States, Minnesota | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 8 | PI 203524 | No.3 | Cuba | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 9 | PI 201239 | CHILE ARCHO SAN LUIS | Mexico | NPGS | C. annuum |

| 10 | PI 634826 | GREENLEAF TABASCO | United States, Alabama | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 11 | PI 441649 | BGH 1797 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 12 | PI 631144 | chile nan | Guatemala, Jutiapa | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 13 | PI 593924 | WWT-1336 | Ecuador | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 14 | PI 487623 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. frutescens | |

| 15 | PI 439512 | Rat chili | Mexico | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 16 | PI 439521 | 834 | Solomon Islands | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 17 | PI 585251 | Ecu 2239 | Ecuador, Manabi | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 18 | PI 194260 | 1SCA | Ethiopia | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 19 | Grif 9319 | 14031 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 20 | PI 631142 | diente de perro | Guatemala, Escuintla | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 21 | PI 645561 | Chiang Mai #1 | Thailand | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 22 | PI 441652 | BGH 4179 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. frutescens |

| 23 | PI 159248 | 1SCA | United States, Georgia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 24 | PI 441620 | BGH 1719 | Brazil | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 25 | PI 224412 | No.1555 | Bolivia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 26 | PI 152222 | 1SCA | Peru | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 27 | PI 257176 | 1SCA | Peru | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 28 | PI 543208 | Aji | Bolivia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 29 | PI 224449 | No.1633 | Peru | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 30 | PI 241668 | 1SCA | Ecuador | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 31 | PI 562384 | RED SAVINA HABANERO | United States | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 32 | PI 438643 | Habanero No. 44 | Mexico, Yucatan | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 33 | PI 640902 | Yellow Squash | United States | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 34 | PI 438636 | Habanero No. 1 | Mexico, Yucatan | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 35 | PI 653672 | Peru-7209 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 36 | Grif 9238 | 13978 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 37 | Grif 9182 | Grif 9182 | Colombia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 38 | PI 159236 | 30040 | United States, Georgia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 39 | PI 656271 | 6123 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 40 | Grif 9261 | Honduras-11058 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 41 | PI 241650 | No.1236 | Peru | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 42 | PI 593612 | 30062 | United States, New Mexico | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 43 | PI 159234 | No.4658 | United States, Georgia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 44 | PI 653673 | Grif 9302 | Colombia | NPGS | C. chinense |

| 45 | PI 639649 | WWCQ-207 | Paraguay, Canendiyu | NPGS | C. baccatum var. baccatum |

| 46 | PI 441539 | BGH 1036 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 47 | PI 653670 | Peru-5391 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 48 | PI 441553 | BGH 1668 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 49 | Grif 9198 | Peru-5383 | Costa Rica | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 50 | PI 441545 | BGH 1607 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 51 | PI 497972 | Dedo de Moca | Brazil | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 52 | PI 596058 | 3015 | Bolivia, Chuquisaca | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 53 | PI 439388 | 1986 | Peru | NPGS | C. baccatum |

| 54 | PI 596055 | 3009 | Bolivia, Chuquisaca | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 55 | PI 632922 | WWMC 122 | Paraguay, Caazapa | NPGS | C. baccatum var. baccatum |

| 56 | PI 281300 | Cristal | Argentina | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 57 | PI 281320 | Aji cristal | Chile | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 58 | PI 441570 | BGH 1785 | Brazil, Minas Gerais | NPGS | C. baccatum var. pendulum |

| 59 | PI 585277 | Ecu 2243 | Ecuador, Carchi | NPGS | C. pubescens |

| 60 | Grif 1613 | Grif 1613 | - | NPGS | C. pubescens |

| 61 | PI 593623 | 80040 | Guatemala | NPGS | C. pubescens |

| 62 | PI 585274 | Ecu 6222 | Ecuador, Napo | NPGS | C. pubescens |

| 63 | PI 593632 | 80049 | Guatemala | NPGS | C. pubescens |

Library construction and sequencing

The CTAB extraction method was used to isolate genomic DNA from fresh leaves. High quality genomic DNA was confirmed through 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis for library construction37. We constructed two paired-end libraries with 10-fold depth for each pepper line. Briefly, genomic DNA was sheared using ultrasonic to yield an average size of 500 bp DNA fragments. Then Illumina paired-end adaptors were ligated to the fragmented DNA. The ligated DNA products were selected based on the fragment size on a 2% agarose gel. Amplification of the products was performed by PCR using specific primers to form the libraries. After inspection, the resulting libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiseqTM 2500 sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) in the company of Biomarker Technologies. Raw reads of 2 × 100 bp were generated for the downstream analyses.

Data filtering, alignment, variants calling

The genome sequence of C. annuum cv. CM334 (2.96 Mb) was obtained from the Pepper Genome Platform (PGP) (http://peppergenome.snu.ac.kr/download.php) to use as the reference. Low quality reads were filtered out using a custom C program based on the default parameters. The cleaned data were aligned to the reference pepper genome using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA0.7.10-r789) program38 with the default values. The alignment results in SAM format were transformed to Binary Alignment Map (BAM) format files through SAMTools39. Mark Duplicates in Picard tool (v1.102) (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was applied to remove replicate reads, and the two BAM files were used for the next analyses. To reduce the inaccurate alignments, GATK Tool Kits version 3.1 was used to conduct the local realignment around the insertions and deletions, reads base quality recalibration and variant calling40.

InDels flanking sequences extraction and primer design

For the identification of InDel polymorphisms between the re-sequenced PBC688 and G29, we explored the reference genome of CM334 as a ‘bridge’ to detect sequence polymorphisms between them. The single-end reads of G29 were aligned to the reference sequence of CM334 via SOAP with no gaps allowed. The aligned reads dataset was compared against the InDel polymorphism dataset identified between PBC688 and CM334. Only those InDels with identical sequences between G29 and CM334 were considered as real InDels between G29 and PBC688. Once the location of InDel polymorphisms between one re-sequenced accession and the reference was established, those between the two re-sequenced accessions are readily distinguished at corresponding positions where the second accession is identical to the reference31. In order to develop the InDels markers, we extracted 150-bp flanking nucleotides on two sides of an InDel to query the reference genome sequence using a simple Visual C++ script for primers design. Primer 5 (http://www.PromerBiosoft.com) was used to design PCR primers with length of 19–22 bp, Tm of 52–60 °C, and PCR products of 80–250 bp.

Chromosomal location and genomic synteny in pepper

The chromosomal localization of InDel markers was acquired from the CM334 genome database PGP (http://peppergenome.snu.ac.kr), and the InDel markers were located on chromosomes using MapDraw41. The genomic information of C. annuum, C. chinense and C. baccatum were also downloaded from PGP. The C. annuum genome was compared to C. chinense and C. baccatum genomes using the MCScan toolkit (V1.1)42. To determine synteny blocks, we used all-against-all LAST43 and fettered the LAST hits with a distance cutoff of 20 genes, also requiring at least 4 gene pairs per synteny block. Python version of MCScan was performed to construct chromosome-scale synteny blocks plots (https://github.com/tanghaibao/jcvi/wiki/ MCscan-(Python-version).

Functional annotation of genetic InDels

The genes of related InDels were identified by comparison with the reference genome of CM334. The functions of these genes were predicted through sequence alignment with NR, SwissProt, GO, COG, KEGG database by BLAST. The Functional annotation of these genes were determined based on the information of the Gene Ontology Consortium (http://geneontology.org/).

Experimental validation of DNA polymorphism

The PCR was performed in 20-μl of reaction mixture containing 2 μl genetic DNA sample (40 ng), 10 μl 2x Taq Mastermix II (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 0.5 μM of each primer and amount of ddH2O. The thermal cycles include 94 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 40 s, with an extension 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were analyzed by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized with silver staining.

Phylogenetic analysis

PCR amplifications were separated on gels and scored as absent (0) or present (1). PowerMarker version 3.25 (Liu and Muse 2005, http://statgen.ncsu.edu/powermarker/) was used to calculate the number of alleles per locus, major allele frequency, gene diversity, polymorphism information content (PIC) values, and classical F st values. PowerMarker was performed to calculate Nei’s distance (Nei et al. 1973). Then, the unrooted phylogeny was constructed using the file of Nei’s distance based on neighbor-joining method with the tree viewed using MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al. 2007, http://www.megasoftware.net/).

Results

Identification of InDel polymorphisms between C. annuum cv. G29 and C. frutecens cv. PBC688

A total of 319,522,376 and 309,682,186 clean reads were generated for PBC688 and G29, respectively. Using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA), 2.54 × 108 and 2.79 × 108 of the PBC688 and G29, respectively, obtained reads were mapped to the reference genome CM334. The mapping read depth was 11x for PBC688 and 12x for G29. The overall genome coverage was 94.0% for PBC688 and 97.5% for G29, with an average of 95.8%. For PBC688 and G29, 76.2% and 87.9% pair-end (PE) reads, and 3.2% and 2.2% single-end (SE) reads were mapped to the reference chromosomes corresponding to 2.96 Gb of CM334 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the original sequencing data of PBC688 and G29.

| Sample | Clean-reads | PE (%) | SE (%) | Map ratio (%) | Q20 (%) | Depth | Cover ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC688 | 319,522,376 | 76.2 | 3.2 | 79.4 | 94.9 | 11 | 94 |

| G29 | 309,682,186 | 87.9 | 2.2 | 90.1 | 94.9 | 12 | 97.5 |

| Average | 314,602,281 | 82.1 | 2.7 | 84.8 | 94.9 | 11.5 | 95.8 |

Genome-wide insertion/deletion polymorphisms were examined via GATK software. In total, 1,664,770 InDels were identified between PBC688 and CM334. These InDels were distributed across all the twelve chromosomes, varying from 168,460 on chromosome 09 to 88, 291 on chromosome 08. At the same time, we identified 533,523 InDels between G29 and CM334 that ranged from 82,799 on chromosome 11 to 13,647 on chromosome 08. The InDels between PBC688 and G29 included different InDels than those described above, and the number of InDels ranged from 173,195 on chromosome 11 to 86,696 on chromosome 8 (Table 3).

Table 3.

InDel polymorphisms identified on individual chromosomes of Capsicum.

| CD(MB) | PBC688 versus CM334 | G29 versus CM334 | PBC688 versus G29 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InDel number | Frequency (InDels/Mb) | InDel number | Frequency (InDels/Mb) | InDel number | Frequency (InDels/Mb) | ||

| Chr1 | 272.7 | 152473 | 559.1 | 66466 | 243.7 | 159094 | 583.4 |

| Chr2 | 171.1 | 112170 | 655.5 | 40498 | 236.7 | 110357 | 644.9 |

| Chr3 | 257.9 | 163193 | 632.8 | 44010 | 170.6 | 158889 | 616.1 |

| Chr4 | 222.6 | 129116 | 580.1 | 27962 | 125.6 | 125802 | 565.2 |

| Chr5 | 233.5 | 135960 | 582.3 | 35179 | 150.7 | 134106 | 574.4 |

| Chr6 | 236.9 | 141153 | 595.8 | 40996 | 173.0 | 137156 | 578.9 |

| Chr7 | 231.9 | 145457 | 627.2 | 57444 | 247.7 | 140859 | 607.4 |

| Chr8 | 145.1 | 88291 | 608.5 | 13647 | 94.1 | 86696 | 597.5 |

| Chr9 | 252.8 | 146724 | 580.4 | 52697 | 208.5 | 150116 | 593.9 |

| Chr10 | 233.6 | 143004 | 612.2 | 41440 | 177.4 | 138197 | 591.6 |

| Chr11 | 259.7 | 168460 | 648.6 | 82799 | 318.8 | 173795 | 669.1 |

| Chr12 | 235.7 | 138769 | 588.8 | 30385 | 128.9 | 136789 | 580.4 |

| Total | 2753.5 | 1,664,770 | 604.6 | 533,523 | 193.8 | 1,651,856 | 599.9 |

The average densities of the detected InDels between CM334 with PBC688 and G29 were 604.6 and 193.8 InDels/Mb, respectively. The InDels frequencies ranged from 655.5 InDels/Mb on chromosome 02 to 559.1 InDels/Mb on chromosome 01 between PBC688 and CM334, from 318.8 InDels/Mb on chromosome 11 to 94.1 InDels/Mb on chromosome 08 between G29 and CM334, and from 669.1 InDels/Mb on chromosome 11 to 563.2 InDels/Mb on chromosome 04 between PBC688 and G29 (Table 3).

In the present study, we detected that the largest InDel was 49 bp and the single base-pair InDels were dominant and accounted for about 65% of those analyzed. The ratios of InDels less than 10 bp were 94.4%, 92.6% and 94.3%, and those of less 6 bp was 89.1%, 86.2% and 89.1%, respectively, among the three different genomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

The number and distribution ratios of InDels identified in the Capsicum genome.

| InDel size (bp) | PBC688 versus CM334 | G29 versus CM334 | PBC688 versus G29 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InDel number | Ratio (%) | InDel number | Ratio (%) | InDel number | Ratio (%) | |

| 1 | 1133853 | 68.1 | 345796 | 64.8 | 1129627 | 68.4 |

| 2 | 193287 | 11.6 | 62199 | 11.7 | 186832 | 11.3 |

| 3 | 79302 | 4.8 | 25317 | 4.7 | 79602 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 49406 | 3.0 | 16860 | 3.2 | 49560 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 26706 | 1.6 | 9614 | 1.8 | 27140 | 1.6 |

| 6 | 25864 | 1.6 | 9431 | 1.8 | 25056 | 1.5 |

| 7 | 16295 | 1.0 | 6322 | 1.2 | 15470 | 0.9 |

| 8 | 16777 | 1.0 | 6475 | 1.2 | 16107 | 1.0 |

| 9 | 16396 | 1.0 | 6348 | 1.2 | 15547 | 0.9 |

| 10 | 13945 | 0.8 | 5459 | 1.0 | 13361 | 0.8 |

| ≥11 | 92,939 | 5.6 | 39702 | 7.4 | 93554 | 5.7 |

| Total | 1664770 | 100.0 | 533523 | 100.0 | 1651856 | 100.0 |

Genomic annotation and synteny of InDels in pepper

The use of the annotated genome of CM334 enabled the annotation of InDels, and to assign them with corresponding genes. We examined the distribution of the InDels related to genes of Capsicum and found that most of them were located within intergenic regions. Among the 1,664,770 and 533,523 InDel polymorphisms detected in CM334 compared with PBC688 and G29, 63,992 (3.8%) and 23,897 (4.5%) InDels were in gene regions, and only 2,519 and 1,019 were found in coding sequences. Among the 1,651,856 InDels identified between PBC688 and G29, 58,944 (3.6%) InDels were in genetic regions, with only 2,252 in coding sequences (Table 5).

Table 5.

Location and types of InDel polymorphisms identified in Capsicums.

| Region | Type | G108 vs CM334 | G29 vs CM334 | PBC688 vs G98 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Intergenic | 1571746 | 499518 | 1565544 |

| — | Intragenic (without transcript) | 57 | 1 | 57 |

| — | Intron | 4333 | 1547 | 4049 |

| — | Upstream (within 5 Kb) | 1540 | 561 | 1450 |

| — | Downstream (within 5 Kb) | 55535 | 20765 | 51124 |

| — | Splice Site Acceptor | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| — | Splice Site Donor | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| CDS | Start Lost | 7 | 2 | 7 |

| CDS | Frame Shift | 1685 | 663 | 1555 |

| CDS | Codon Insertion | 287 | 147 | 211 |

| CDS | Codon Deletion | 262 | 98 | 257 |

| CDS | Codon Change Plus Codon Insertion | 107 | 49 | 73 |

| CDS | Codon Change Plus Codon Deletion | 155 | 54 | 140 |

| CDS | Stop Gained | 10 | 5 | 6 |

| CDS | Stop Lost | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| — | Other | 29032 | 10108 | 27368 |

| Total | 1664770 | 533523 | 1651856 |

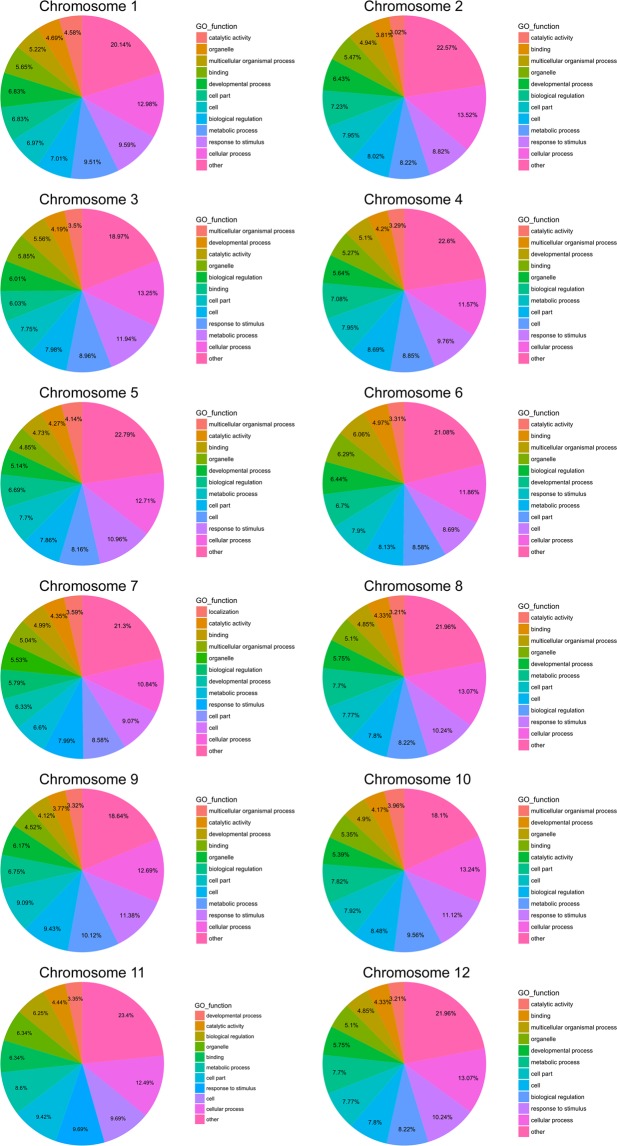

The functional characterization of genes with the polymorphic InDels were distributed across all 12 chromosomes of pepper. Overall, most of the genes widely involved in cellular process, cell, cell part, metabolic process, response to stimulus, developmental process, biological regulation, organelle, multicellular organismal process, binding, catalytic activity, location and others (Fig. 1). Specifically, cellular process related genes consisted of most polymorphic InDels in all of chromosomes. Moreover, response to stimulus genes with high polymorphic InDels consisted of numerous polymorphic InDels in chromosome 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 12. In chromosome 6, 7 and 11, the genes associated with cell (cellular component) consisted of more polymorphic InDels followed cellular process. However, in chromosome 3, genes referred to metabolic process involved in abundant InDels. In addition, most of genes have multiple functions and involve in regulation of multiple process (Supplementary Dataset 4).

Figure 1.

Chromosome annotation of polymorphic genic InDels associated with functional genes between PBC688 and G29.

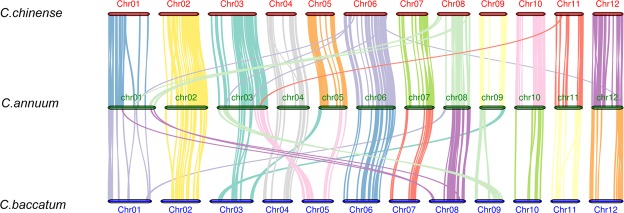

Based on the three published genomes of C. annuum, C. chinense and C. baccatum, we analyzed the genetic synteny among them. In the C. annuum genome, we identified 202 and 131 syntenic blocks, involving 7,186 and 4,666 genes compared with C. chinense and C. baccatum, respectively (Supplementary Dataset 1 and 2). We found 106 and 60 chromosomal translocations between C. annuum to C. chinense and C. baccatum, respectively. However, these translocations were distributed on different chromosomes and could be used as firm evidence for chromosomal rearrangements. We found the translocations were located on different chromosomes between C. annuum and C. chinense: Chr01/Chr06, Chr01/Chr08, Chr03/Chr06, Chr03/Chr11, and Chr12/Chr06. Compared with C. annuum and C. chinense, translocations were located on more chromosomes between C. annuum and C. baccatum: Chr01/Chr08, Chr03/Chr05, Chr03/Chr09, Chr05/Chr03, Chr08/Chr01, Chr09/Chr03 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Syntenic blocks in the C. annuum, C. chinense and C. baccatum show the genome rearrangements among the three species.

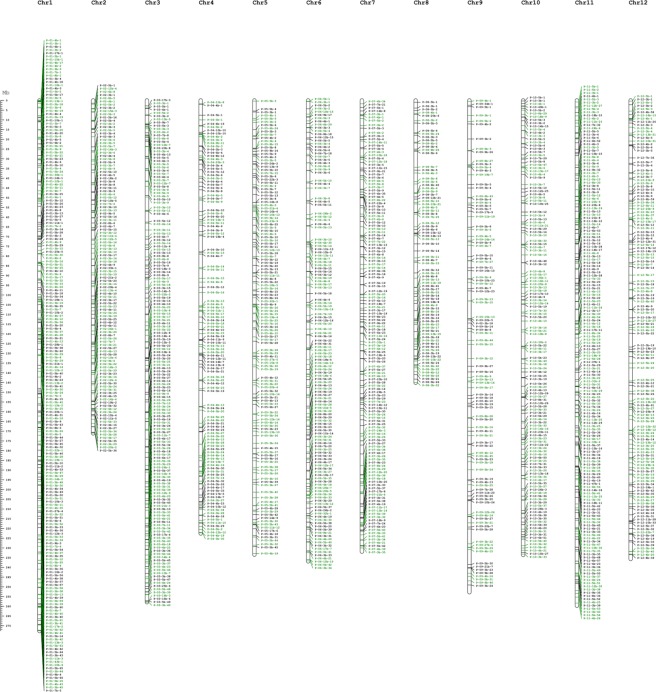

Experimental validation of short InDel polymorphisms

To validate the InDels identified between PBC688 and G29, we selected 1605 out of 1,651,856 InDels following the rule of uniform distribution and converted them to PCR-based markers. According to the chromosomal location of InDels in C. annuum cv. CM334, the 1605 markers were distributed across all 12 chromosomes of pepper (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Dataset 3). Among the 1605 InDels, 69 (4.3%) InDels located to genetic regions (Supplementary Dataset 3). This rate was consistent with that of the whole genome. Then, we analyzed the genetic synteny of the blocks including 1605 InDels among the three published genomes of Capsicum. The C. annuum InDels shared highly conserved syntenic blocks with those of C. chinense and C. baccatum (Supplementary Fig. 1) improving the stability of these InDels among the different Capsicum species. Based on this selection, we designed primer pairs to amplify fragments of 150 bp surrounding the InDels. In the PCR analysis, most markers had clear amplification in PBC688 and G29 genomes with some others generating multiple amplicons.

Figure 3.

Distribution of 1605 InDels markers on each chromosome of the C. capsicum InDels marker names are listed to the right of the chromosomes. The ruler label to the left of chromosomes represents the physical distance. The black markers indicated deletion and red markers represented insertion.

For 1605 primer pairs of InDels, 1560 (97.2%) gave reliable amplification in PBC688 and G29. Using PAGE,1262 (78.6%) showed identifiable polymorphisms between PBC688 and G29; 90 of these produced an amplicon in only one genotype and therefore were not suitable for genetic analysis; 298 (18.6%) were monomorphic and 45 (2.8%) failed. The polymorphism rate increased slightly with increase of InDel length, and the polymorphism rate varied from 65.3% on InDels of 3 bp to 79.1% on those of more than 10 bp (Table 6).

Table 6.

The distribution of polymorphic InDel markers between PBC688 and G29.

| InDel size (bp) | InDels number | PBC688 versus G29 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codominant markers | Monomorphic markers | Dominant markers | No amplification | ||

| 3 | 398 | 260 (65.3%) | 104 (26.1%) | 25 (6.3%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| 4 | 259 | 175 (67.6%) | 66 (25.5%) | 14 (5.4%) | 4 (1.5%) |

| 5 | 506 | 389 (76.9%) | 72 (14.2%) | 28 (5.5%) | 17 (3.4%) |

| 6–10 | 212 | 166 (78.3%) | 26 (12.3%) | 12 (5.7%) | 8 (3.7%) |

| ≥11 | 230 | 182 (79.1%) | 30 (13.0%) | 11 (4.8%) | 7 (3.0%) |

| Total | 1605 | 1172 (73.0%) | 298 (18.6%) | 90 (5.6%) | 45 (2.8%) |

To investigate the universal applicability of the InDel markers, we tested 288 among the inter-species and 576 between the intra-species. First, we screened five accessions representing five domesticated species for polymorphisms with 288 InDels. Polymorphisms were seen in 182 (63.2%) between PBC688 and G29 with 109 (37.8%) being monomorphic, while 194 (67.4%) and 87 (30.2%) were monomorphic among five accessions. Interestingly, twelve InDels monomorphic between PBC688 and G29 showed identifiable polymorphisms among five accessions. In addition, 7 (2.4%) produced no amplification in any accession. Together, our results suggest that these InDels may have universal applicability in the five domesticated species (Table 7). Then we selected two C. annuum accessions, G29 and G43, together with two C. frutescens accessions PBC688 and PI 439512 (16) to validate the InDel markers polymorphic between the intra-species accessions. Among 576 tested InDels (3–5 bp), 72 (12.5%) showed polymorphism between the two C. annuum accessions and 76 (13.2%) between the two C. frutescens accessions, although 488 (84.7%) were monomorphic between the two C. annuum accessions, 484 (84.0%) were monomorphic between the two C. frutescens accessions, and 16 (2.8%) failed in either species (Table 8).

Table 7.

The distribution of polymorphic InDel markers among interspecific accessions.

| InDel size (bp) | InDels number | PBC688 vs G29 | 2 vs 15 vs 24 vs 47 vs 60a | No amplification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polymorphic InDels | Monomorphic InDels | polymorphic InDels | monomorphic InDels | |||

| 3 | 96 | 53 (55.2%) | 40 (13.9%) | 62 (64.6%) | 31 (32.3%) | 3 (3.1%) |

| 4 | 96 | 61 (63.5%) | 33 (11.5%) | 66 (68.8%) | 28 (29.2%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| 5 | 96 | 58 (60.4%) | 36 (12.5%) | 66 (68.8%) | 28 (29.2%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| total | 288 | 182 (63.2%) | 109 (37.8%) | 194 (67.4%) | 87 (30.2%) | 7 (2.4%) |

a2: C. annuum cv. PI 224408, 15: C. frutescens cv. PI 439512, 24: C. chinense cv. PI 441620, 47: C. baccatum cv. PI 441539, 60: C. pubescens cv. PI 585277.

Table 8.

The distribution of polymorphic InDel markers between intraspecific accessions.

| InDel size (bp) | InDel number | C. annuum | C. frutescens | No amplification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G29 vs G43 | PBC688 vs PI 439512 | |||||

| Polymorphism (Ratio) | Monomorphic (Ratio) | Polymorphism (Ratio) | Monomorphic (Ratio) | |||

| 3 | 192 | 22 (11.5%) | 163 (84.9%) | 26 (13.5%) | 159 (82.8%) | 7 (3.6%) |

| 4 | 192 | 26 (13.5%) | 161 (83.9%) | 20 (10.4%) | 167 (87.0%) | 5 (2.6%) |

| 5 | 192 | 24 (12.5%) | 164 (85.4%) | 30 (15.6%) | 158 (82.3%) | 4 (2.1.%) |

| Total | 576 | 72 (12.5%) | 488 (84.7%) | 76 (13.2%) | 484 (84.0%) | 16 (2.8%) |

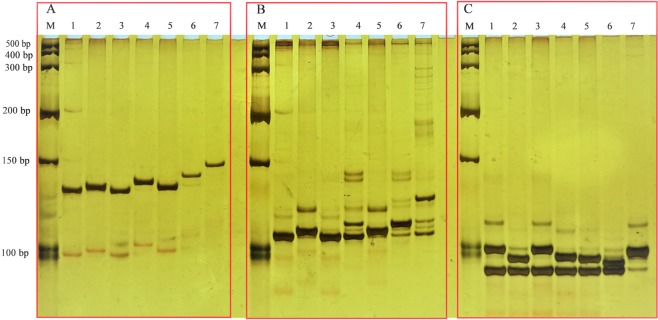

Experimental validation of the species-specific InDel markers

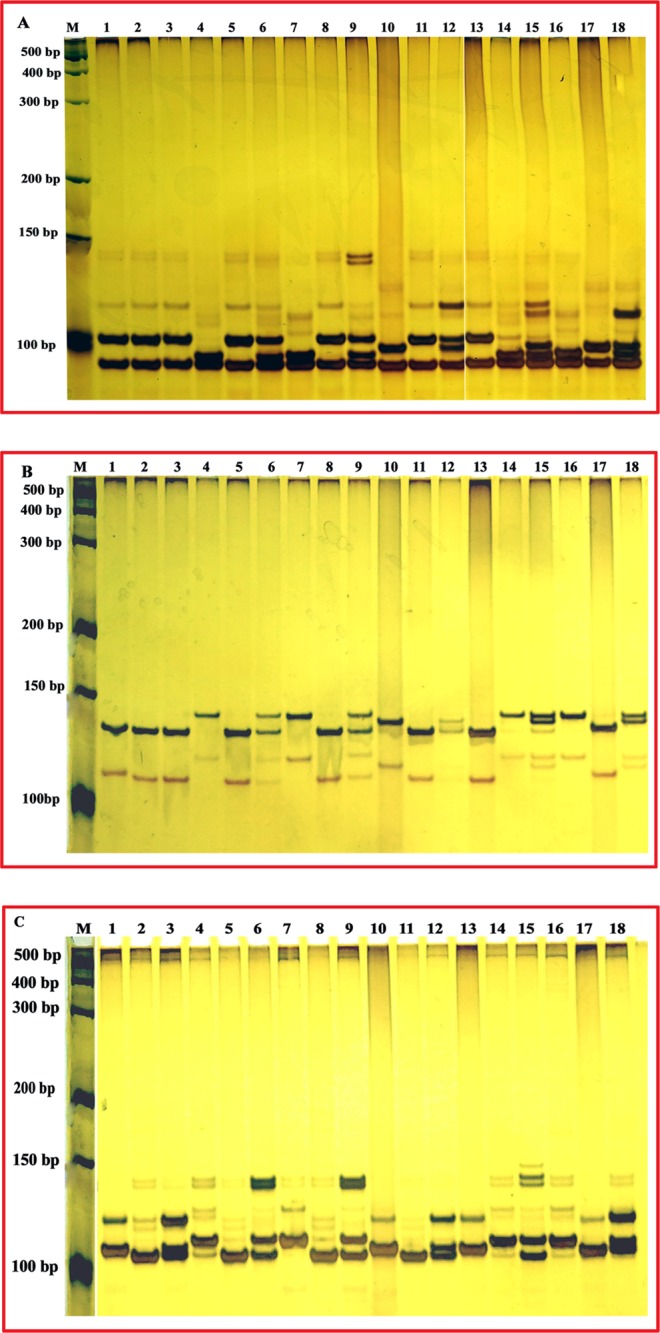

First, we found three InDel markers (InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5) each amplifying specific products in seven accessions representing five domesticated species (Fig. 4). To investigate the reliability of the result, we screened 10 accessions representing five domesticated species using these markers, and InDel-02-3b-22 and InDel-02-3b-25 revealed identifiable polymorphisms, while InDel-03-3b-5 amplified four specific products (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

The PCR profiles of InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 in 7 accessions representing 5 domesticated species (A) InDel-02-3b-25, (B) InDel-03-3b-5, (C) InDel-02-3b-22 M: Marker, 1: C. annuum cv. G29, 2: C. frutescens cv.PBC688, 3: C. annuum cv. PI 224408, 4: C. frutescens cv. PI 439512, 5: C. chinense cv. PI 441620, 6: C. baccatum var. Pendulum cv. PI 441539, 7: C. pubescens cv. PI 585277.

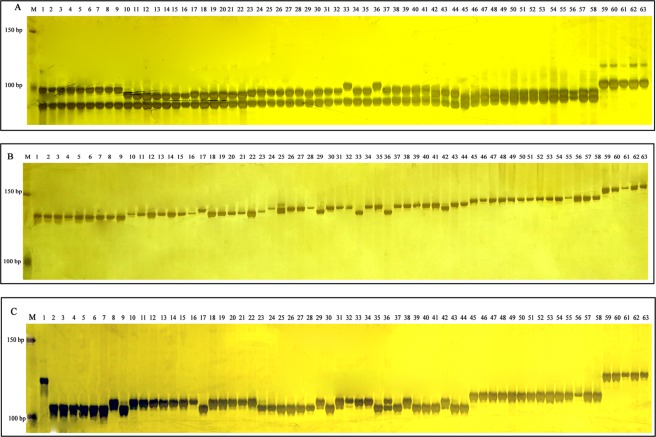

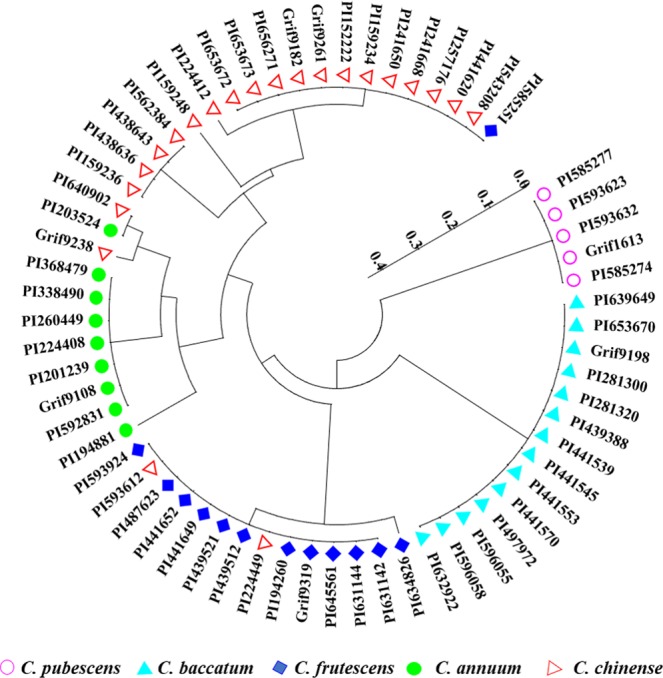

To test whether InDel-02-3b-22 or InDel-02-3b-25 could individually distinguish five domesticated species, we randomly selected 63 accessions representing five domesticated species (Table 1). We detected 16 alleles for a total of 1008 data points through InDel analysis. The number of alleles at each locus varied from 5 for InDel-02-3b-22 and InDel-03-3b-5 to 6 for InDel-02-3b-25 (Fig. 5A–C, Supplementary Dataset 4). We used the variation for the 16 alleles to derive the dendrogram which showed that the 63 accessions were classified based on the five domesticated species. Among them, 58 accessions genotyped were consistent with the past subspecies classification. Specifically, nine C.annuum, fourteen C. baccatum and five C. pubescens were grouped into three classes. However, 2 of 22 C. chinense (PI593612 and PI224449) and 2 of 22 C. chinense (PI640902 and Grif9238) were grouped into the C. frutescens and C.annuum cluster, respectively. And 1 of 13 C. frutescens (PI585251) was grouped into the C. chinense cluster (Fig. 6). It is interesting that the three InDel markers InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 associated with three genes, CA02g13520, CA02g20590 and CA03g07770, respectively. Functional analysis showed CA02g13520 encoded a protein with unknown function. CA02g20590 encoded serine/threonine-protein kinase STY17-like. CA03g07770 encoded the chloride channel protein CLC-d (Supplementary Dataset 3).

Figure 5.

The PCR profiles of InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 in 63 accessions representing 5 domesticated species (A) InDel-02-3b-22, (B) InDel-02-3b-25, (C): InDel-03-3b-5 M: Marker, 1-9: Nine accessions of C. annuum, 10–22: Thirteen accessions of C. frutescens, 23–44: Twenty-two accessions of C. chinense, 45–58: Fourteen accessions of C. baccatum, 59–63: Five accessions of C. pubescens.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree based on the three InDel markers data showing the genetic relationship among the 63 Capsicum accessions.

To test the ability to identify the interspecific hybrids with three species-specific InDel markers, we selected six parents and their interspecific hybrids. We found that the fifth hybrid was incorrectly identified because its amplification pattern was not consistent with its parents with all three InDels (Fig. 7A–C). Either InDel-02-3b-22 or InDel-02-3b-25 could distinguish four of the remaining five hybrids, and InDel-03-3b-5 worked in all the cases (Fig. 7A–C). For the that hybrid that failed with InDel-02-3b-22 or InDel-02-3b-25, we found it was because these two markers could not differentiate its male parent C. chinense cv. PI 640902 and female parent C. annuum cv. G83. Our results imply that these three species-specific InDel markers could discriminate most hybrids formed from interspecific hybridization, and molecular markers are more accurate and convincing than phenotyping for identification.

Figure 7.

The PCR profiles of InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 in 6 parents and their hybrids (A) InDel-02-3b-22, (B) InDel-02-3b-25, (C) InDel-03-3b-5 M: Marker 1–3: female parent: C. chinense cv. PI 640902, Male parent: C. annuum cv. G83, hybrid 4–6: female parent: C. baccatum cv. G568, Male parent: C. annuum cv. G83, hybrid 7–9: female parent: C. baccatum cv. PI441570, Male parent: C. annuum cv. G83, hybrid 10–12: female parent: C.frutescens cv. PI634826, Male parent: C. annuum cv. G83, hybrid 13–15: female parent: C. chinense cv. PI 159236, Male parent: female parent: C. baccatum cv. G568, hybrid 16–18: female parent: C. baccatum cv. PI441570, Male parent: female parent: C. frutescens cv. PI634826, hybrid.

Discussion

Despite the development of SNP genotyping technologies, InDel markers also have important practical value for those researchers and breeders without the instruments to test SNP markers. We identified 1,651,856 InDels between PBC688 and G29 that represent an average of 599.9 InDels/Mb across the entire Capsicum genome. A previous study showed that the number of InDels from C. annuum cv. Perennial and cv. Dempsey was 654,158 and 694,494 respectively when compared with the CM334 genome sequence. However, the wild species C. chinense has a significantly higher level of InDels (2,450,533) compared to these two cultivars34. This is consistent with our study in that the number of InDels among C. annuum intra-species is quite low; in contrast, there exists a higher level of InDels among Capsicum inter-species. However, the number of InDels from the previous study was obviously less than that in our study. Approximately 555,400 short InDels (1–5 bp) were detected in Zunla-1 relative to Chiltepin, and, 373,785 and 231,056 short InDels (1–5 bp) were detected in Zunla-1 relative to C. chinense and CM3342. There may be two main reasons for the difference. Firstly, in our study, we used CM334 genome as the reference genome, so our results are consistent with the study. Secondly, the previous study only detected short InDels (1–5 bp), so the number of InDels was significantly less than that in our study.

Chromosomal rearrangement often produces unbalanced gametes that reduce hybrid fertility and plays an important role in promoting speciation44. In our study, collinearity comparison among Capsicum species revealed that chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 8, 9 and 12 exhibit translocations that differentiate C.annuum from C.chinense and C.baccatum. Our result was similar with previous studies about Capsicum species. Kim et al. reported that chromosomal translocations among chromosomes 3, 5, and 9 were observed by comparison between C.baccatum and the two other peppers45. Wu et al. reported the cultivated C.annuum genome included two acrocentric chromosomes versus a single acrocentric chromosome detected in C. chinense, C. frutescens and wild C.annuum46. Moreover, Wu et al. revealed that between the pepper and tomato genomes there exists at least 19 inversions, 6 chromosome translocations, and numerous putative single gene transpositions as determined by collinearity comparison46. Based on the genomes of Capsicum species and two Solanum species, collinearity comparisons showed that chromosome 6 and 4 of Solanum were discovered in the terminal regions of the long and short arms of chromosomes 3 and 5 in C.annuum and C.chinense, respectively45.

In this study, the localization of InDels within the pepper genome showed more than 95% InDels were in intergenic regions. Similarly, more InDels were detected in the intron than in CDS. Previous studies about genome-wide SNP and InDel discovery revealed the similar results in multiple crops, such as tomato and Brassica rapa31,47. In pepper, 93.06% and 93.39% of intergenic SNPs were detected for varieties PRH1 and Saengryeg, respectively48.

In order to obtain in-depth knowledge in the InDels in our study associated with genes, these polymorphic InDels within genetic regions were functionally annotated in each chromosome. The current results revealed that genes involved in cellular process consisted of most polymorphic InDels in all chromosomes. Then, high polymorphic InDels with “response to stimulus” related genes InDelwere mapped in chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 12. Because of different focus, our results had some differences with a previous study by Ahn et al., who reported that most genes with high polymorphic SNPs were related with carbohydrate metabolism, followed by transcription regulation, ion binding and others. In addition, they found numerous genes with high polymorphic SNPs related to disease resistance mapped to chromosome 4, which could play a vital role in future pepper breeding47.

In this study, we confirmed InDels can be developed as potentially valuable genetic markers with a reliable high rate of polymorphism. Among 1605 InDels of 3–49 bp in length, 1262 (78.6%) showed polymorphisms. Only 45 (2.8%) of the primers yielded no amplification from either of the two sequenced accessions. This can be explained by sequence variations in the primer binding sites among Capsicum species as we designed primers based on the reference genome sequence31. In contrast to the high polymorphism rate of InDels among five accessions representing five domesticated species, two C. annuum and C. frutescens accessions showed much lower polymorphism rates. As expected, our results suggest that polymorphism rate of InDel markers within species was much lower than that among species. In a previous study on genome-wide re-sequencing inbred lines C. annuum cv. BA3 and B702, more than 90% of the InDel markers were amplified. However, only 27.2% and 12.9% markers were polymorphic between BA3 with B702 or C. frutescens cv. YNXML, respectively9,27.

Most importantly, we found three inter-species specific InDels (InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-3b-3-5) each of which could highly discriminate among most of the accessions under study and which efficiently identified interspecific hybrids, implying their potential application for new germplasm classification and interspecific hybrid identification in the future. Our results showed that InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 could individually discriminate almost all the accessions, which agrees with a previous study. Di Dato et al. (2015) showed that most accessions (among 59 accessions) were clearly differentiated with ten SSR markers except two accessions of C. chinense, which were grouped into C. frutescens cluster. He concluded that the two abnormal accessions were genetically distant from others analyzed C. chinense12. In our study, the accessions of C.annuum, C. baccatum and C. pubescens had clearly specific amplification products, although 4 accessions of C. chinense and 1 accessions of C. frutescens showed some confusing patterns. Our results confirmed previous findings based on both phenotypes and molecular markers that C. annuum was closely related to C. chinense and C. frutescens, and distant to C. baccatum and C. pubescens12,49.

The location of markers is a vital factor for the application value of markers. These markers are located in intragenic regions to implicate the phenotypic traits and have more potential applications in marker assisted selection as functional markers4. In our study, the three InDel markers InDel-02-3b-22, InDel-02-3b-25 and InDel-03-3b-5 were in intragenic regions and associated with three genes, CA02g13520, CA02g20590 and CA03g07770, respectively. CA02g20590 encoded serine/threonine-protein kinase STY17-like. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the protein kinases STY8, STY17, and STY46 played a vital role in phosphorylating of transit peptides for chloroplast-destined preproteins50. CA03g07770 encoded the chloride channel protein CLC-d. In Arabidopsis thaliana, CLCd was targeted to Golgi apparatus and could suppress the cation-sensitive phenotype of Δ gef151. Although CA02g13520 encodes a protein with unknown function, but it can be applied to marker assisted selection as a functional marker without any effect.

Together, these novel InDel markers are very valuable reference tools for classification of germplasm resource, identification of interspecific hybrids, genetic research, and marker-assisted breeding in pepper.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0101901), the Agricultural Varieties Development Project of Jiangsu (PZCZ201714) and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-23-G42).

Author Contributions

G.J.G., B.G.P. and G.L.Z. implemented all the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. W.P.D. and J.B.L. were responsible for the figures and tables. W.G. and C.Z.G. helped with material planting. Y.Z. and C.J. performed the experiment of marker verification. S.B.W. designed and supervised the whole work.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-40244-y.

References

- 1.Moscone EA, et al. Analysis of nuclear DNA content in Capsicum (Solanaceae) by flow cytometry and Feulgen densitometry. Ann. Bot. 2003;92:21–29. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of cultivated and wild peppers provides insights into Capsicum domestication and specialization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400975111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscone EA, et al. The evol87ution of chili peppers (Capsicum-Solanaceae): a cytogenetic perspective. Acta Horticulturae. 2007;745:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heiser CB, Pickersgill B. Names for the cultivated Capsicum species (Solanaceae) Taxon. 1969;18:277–283. doi: 10.2307/1218828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Board for Plant Genetic Resoueces (IBPGR). Genetic resources of Capsicum - a global plan of action.Rome: IBPGR Exective Secretariat (1983).

- 6.Dewitt, D. & Bosland, P. W. Peppers of the world: an identification guide. Ten Speed press, Berkeley (1996).

- 7.Oh SJ, et al. Evaluation of genetic diversity of red pepper landraces (Capsicum annuum L.) from Bulgaria using SSR markers. J. Korean Soc. Int. Agric. 2012;24:547–556. doi: 10.12719/KSIA.2012.24.5.547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geleta LF, Labuschagne MT, Viljoen CD. Genetic variability in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) estimated by morphological data and amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005;14:2361–2375. doi: 10.1007/s10531-004-1669-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W, et al. An InDel-based linkage map of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum) Mol. Breed. 2015;35:32–41. doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0219-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ince AG, Karaca M, Onus AN. Genetic relationships within and between Capsicum species. Biochem. Genet. 2010;48:83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10528-009-9297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaï M, Cantet M, Lefebvre V, Sagepalloix AM, Palloix A. Genotyping a large collection of pepper (Capsicum spp.) with SSR loci brings new evidence for the wild origin of cultivated C. annuum and the structuring of genetic diversity by human selection of cultivar types. Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. 2013;60:2375–2390. doi: 10.1007/s10722-013-0006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Dato F, Parisi M, Cardi T, Tripodi P. Genetic diversity and assessment of markers linked to resistance and pungency genes in Capsicum germplasm. Euphytica. 2015;204:103–119. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1345-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vos P, et al. AFLP—a new technique for DNA-fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mccouch SR, et al. Microsatellite marker development, mapping and applications in rice genetics and breeding. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997;35:89–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1005711431474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaraju J, Kathirvel M, Kumar RR, Siddiq EA, Hasnain SE. Genetic analysis of traditional and evolved Basmati and non-Basmati rice varieties by using fluorescence-based ISSR-PCR and SSR markers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5836–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042099099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones N, Ougham H, Thomas H, Pasakinskiene I. Markers and mapping revisited: finding your gene. New Phytol. 2009;183:935–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanksley SD, Bernatzky R, Lapitan NL, Prince JP. Conservation of gene repertoire but not gene order in pepper and tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6419–6423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefebvre V, Palloix A, Rives M. Nuclear RFLP between pepper cultivars (Capsicum annuum L.) Euphytica. 1993;71:189–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00040408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanteri S, Acquadro A, Quagliotti L, Portis E. RAPD and AFLP assessment of genetic variation in a landrace of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), grown in North-West Italy. Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. 2003;50:723–735. doi: 10.1023/A:1025075118200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darine T, Allagui MB, Rouaissi M, Boudabbous A. Pathogenicity and RAPD analysis of Phytophthora nicotianae pathogenic to pepper in Tunisia. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 2007;70:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2007.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JM, Nahm SH, Kim YM, Kim BD. Characterization and molecular genetic mapping of microsatellite loci in pepper. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;108:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minamiyama Y, Tsuro M, Hirai M. An SSR-based linkage map of Capsicum annuum. Mol. Breed. 2006;18:157–169. doi: 10.1007/s11032-006-9024-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min WK, Han JH, Kang WH, Lee HR, Kim BD. Reverse random amplified microsatellite polymorphism reveals enhanced polymorphisms in the 3’ end of simple sequence repeats in the pepper genome. Mol Cells. 2008;26:250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ince AG, Karaca M, Onus AN. CAPS-microsatellites: use of CAPS method to convert non-polymorphic microsatellites into useful markers. Mol. Breed. 2010;25:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9347-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo GJ, et al. Rapid identification of QTLs underlying resistance to Cucumber mosaic virus in pepper (Capsicum frutescens) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016;130:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min HE, Han JH, Yoon JB, Lee J. QTL mapping of resistance to the Cucumber mosaic virus P1 strain in pepper using a genotyping-by-sequencing analysis. Hortic. Environ. Biote. 2016;57:589–597. doi: 10.1007/s13580-016-0128-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan, S. et al. Construction of an interspecific genetic map based on InDel and SSR for mapping the QTLs affecting the initiation of flower primordia in pepper (Capsicum spp.). Plos One10, 10.1371/journal.pone.0119389 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hulse-Kemp AM, et al. A HapMap leads to a Capsicum annuum SNP infinium array: a new tool for pepper breeding. Hortic. Res. 2016;3:16036–16045. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yutaka M, Takahiro I, Yasuhiro M, Nakao K. An SSR-based genetic map of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) serves as an anchor for the alignment of major pepper maps. Breed. Sci. 2012;62:93–98. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.62.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Dang PM, Chen CY. Development and utilization of InDel markers to identify Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:988–999. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu B, et al. Development of InDel markers for Brassica rapa based on whole-genome re-sequencing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013;126:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1976-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan, Y., Yi, G., Sun, C., Qu, L. & Yang, N. Genome-wide characterization of insertion and deletion variation in chicken using next generation sequencing. Plos One9, 10.1371/journal.pone.0104652 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhang XF, et al. Development of a large number of SSR and InDel markers and construction of a high-density genetic map based on a RIL population of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Mol. Breed. 2016;36:92–101. doi: 10.1007/s11032-016-0517-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, et al. Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:270–278. doi: 10.1038/ng.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taranto F, D’Agostino N, Greco B, Cardi T, Tripodi P. Genome-wide SNP discovery and population structure analysis in pepper (Capsicum annuum) using genotyping by sequencing. BMC genomics. 2016;17:943–955. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3297-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng, J. et al. Development of a SNP array and its application to genetic mapping and diversity assessment in pepper (Capsicum spp.). Sci Rep. 6, 10.1038/srep33293 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Murray M, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4326. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu RH, Meng JL. MapDraw: a microsoft excel macro for drawing genetic linkage maps based on given genetic linkage data. Hereditas. 2003;25:317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H, et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Research. 2008;18:1944–1954. doi: 10.1101/gr.080978.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiełbasa SM, Wan R, Sato K, Horton P, Frith MC. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 2011;21:487–493. doi: 10.1101/gr.113985.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matic I. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2001;16:351–358. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim S, et al. New reference genome sequences of hot pepper reveal the massive evolution of plant disease-resistance genes by retroduplication. Genome Biology. 2017;18:210. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu F, et al. A COSII genetic map of the pepper genome provides a detailed picture of synteny with tomato and new insights into recent chromosome evolution in the genus Capsicum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;118:1279–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0980-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim JE, Oh SK, Lee JH, Lee BM, Jo SH. Genome-wide SNP calling using next generation sequencing data in tomato. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:36. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn YK, et al. Whole Genome Resequencing of Capsicum baccatum and Capsicum annuum to Discover Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5188. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mongkolporn, O. & Taylor, P. W. J. Capsicum, 1st, [Kole, C. (ed.)], Wild Crop Relatives Genomic & Breeding Resources (vegetables), 4, 43–57 (Springer, 2011).

- 50.Lamberti G, Gügel IL, Meurer J, Soll J, Schwenkert S. The cytosolic kinases STY8, STY17, and STY46 are involved in chloroplast differentiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:70–85. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lv QD, et al. Cloning and molecular analyses of the Arabidopsis thaliana chloride channel gene family. Plant Sci. 2009;176:650–661. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.