Highlights

-

•

Lipid accumulation in the 3T3-L1 cells were inhibited by treatment with DRE.

-

•

The expression levels of SREBP1c, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FAS were decreased by DRE.

-

•

HFD induced fat mice showed lower rate of weight gain and serum TG level through DRE administration.

Keywords: Obesity, Distylium racemosum, Ethyl acetate fraction

Abstract

This study confirms the anti-obesity effect of the ethyl acetate fraction of Distylium racemosum (DRE), a member of Hamamelidaceae, that naturally grows on Jeju Island, on adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. This study further demonstrated that DRE exhibits anti-obesity effects in C57BL/6 obese mice. The degree of adipocyte differentiation was determined using Oil red O stain; results indicated a decrease in fat globules, which was dependent on DRE concentration, when pre-adipocytes were treated with differentiation-inducing agents. In addition, this significantly reduced the expression of the adipogenic transcription factor and related genes. C57BL/6 obese mice treated with DRE showed a lower rate of body weight gain than the high-fat diet (HFD) group mice. Further, the level of serum triglyceride in the DRE treatment group was lower than that in the HFD group. The findings show that DRE are capable of suppressing adipocyte accumulation; therefore, DRE may represent a promising source of functional materials for the anti-obesity.

1. Introduction

Obesity is defined as the state resulting from the excessive accumulation of fat [1]. It is measured using the body mass index (BMI), which is calculated by dividing a person's bodyweight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters. A BMI of between 25 and 30 indicates that the individual is overweight, and a BMI of 30 or more is indicative of obesity [2]. The global prevalence rate of obesity more than doubled in 2014 compared with that in 1980 [3]. Overweight and obesity are the fifth leading risk factor for deaths worldwide: at least 2.8 million adults die of obesity and being overweight every year, establishing this condition as the most serious health problem in the 21 st century [4]. An adipocyte stores and synthesizes fat, which is crucial to the development of obesity, and comprises adipose tissue. It also functions as a key component of endocrine organs to maintain homeostasis by releasing several hormones [5].

Obesity leads to histological changes, such as the formation of new adipocytes from pre-adipocytes and hypertrophic adipocytes; a variety of transcription factors and genes are involved. AMP-activated protein kinase plays an important role in the regulation of energy balance. Phosphorylated AMPK is involved in inhibiting the expression of specific genes that contribute to the adipocyte differentiation process [6]. Further, the sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), are major genes that regulate the differentiation of adipocytes; these genes encode products that are involved in the production of adipocytes through fatty acid synthase (FAS) and acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC) activity [7]. Effective control of genes involved in the accumulation and differentiation of adipocytes is one of the important strategies to prevent and treat obesity.

Existing anti-obesity drugs, which are synthetic compounds, are associated with side effects and limited effectiveness [8], resulting in an increasing demand for the development of effective drugs without side effects. Certain chemicals such as flavonoid in medicinal plants are known to facilitate the regulation of body weight and body fat by modulating the metabolic pathways in adipocytes [9].

Several medicinal plants grow naturally on Jeju island, the southernmost part of Korea, and numerous studies have been carried out using natural materials extracted from these plants. Natural extracts are sources of numerous medicines currently used in clinical therapy. Distylium racemosum (D. racemosum), a member of Hamamelidaceae, a type of non-deciduous tree that grows wild in Jeju, is widely distributed in Asia [10]. While studies of the inhibitory effects of proanthocyanidin extracted from D. racemosum on α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities [11] and the inhibitory activity of D. racemosum against ribonuclease H [12] have been conducted, there are insufficient studies regarding the associated anti-obesity effects. This study confirmed the effect of D. racemosum fractions on adipocyte differentiation and obesity in vitro and in vivo, respectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), bovine calf serum (BCS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin-streptomycin (PS) were obtained from Welgene (Daegu, Korea). Oil red O, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), dexamethasone, and insulin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and isopropanol were obtained from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). Accuzol was supplied by Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). One Step SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit was obtained from Takara (Tokyo, Japan). 3T3-L1 (ATCC: CL-173) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. Preparation of fraction from D. racemosum

D. racemosum leaves that naturally grow on Jeju island were dried in the shade for two weeks after washing with distilled water two or three times. Then, the leaves were ground into fine powder and used as specimens for extraction. Fractions of D. racemosum were extracted according to the solvent polarity of hexane, ethyl acetate, and butanol. The dried material was extracted with 70% ethanol and this procedure was repeated two times. The filtered extract was concentrated at a reduced pressure and completely dried using a freeze dryer. Then, the dried crude extract was added to distilled water and hexane, and concentrated at a reduced pressure to obtain hexane fractions. The same procedures were conducted, and the fractions of ethyl acetate, butanol, and water layer were acquired successively. All procedures were repeated twice. Fractions of D. racemosum were produced at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and used for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Cell culture and differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells

3T3-L1 cells were grown in DMEM with 10% BCS and 1% PS. At 2 days post confluence, cell differentiation was induced with 10% FBS, 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 μM IBMX, 10 μg/mL insulin, and 1% PS. After 2 days, cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS, 10 μg/mL insulin, and 1% PS for an additional 5 days. This medium was changed every 2 days. Cells were treated with this fraction was treated three times for 7 days. Cells were treated with 0, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL of fraction from D. racemosum. After treatment with extracts for 7 days, the 3T3-L1 adipocytes were stained and RNA extraction performed.

2.4. Cell viability assay

3T3-L1 cells were cultured at 37℃ and under 5% CO2. After cells were counted, cell density was adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/mL. Then, cells were pipetted into a 96-well plate, with 100 μL in each well. The plate was incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO2 for one night, and the D. racemosum fraction was diluted. It was pipetted each 100 μL. The plate was shaken at 150 rpm for 5 min and incubated at 37℃ under 5% CO2 for 48 h. MTT solution concentrated to 5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was pipetted each 20 μL. After shaking at 150 rpm for 5 min, it was incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO2 for 2 h. Media were removed completely. DMSO were pipetted each 200 μL and the 96 well-plate was shaken at 150 rpm for 5 min. Optical density (OD) was measured at 560 nm using an ELISA reader (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.5. Oil Red O staining of 3T3-L1 adipocytes

3T3-L1 cells were incubated in cell culture media containing with various concentrations of the fraction from D. racemosum, washed twice with PBS, and then fixed in 10% formaldehyde prepared for 1 h at room temperature (20℃). The cells were washed with distilled water (DW) three times, and stained with Oil red O solution for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were then washed in DW three times for 1 h each time. All photographs were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope at 400x magnification. The cells were eluted using 100% isopropanol, and OD was measured at 500 nm using a spectrophotometer (Milton Roy Company, New York, USA).

2.6. RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from 3T3-L1 cells using Accuzol. Then, 1 μg of RNA was subjected to qRT-PCR amplification using One Step SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit. The sequences of the designed primers are shown in Table 1. qRT-PCR conditions were: 42℃ for 5 min and 95℃ for 10 s followed by 40 cycles of 95℃ for 3 s and 60℃ for 30 s (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Table 1.

Primers used in the experiment.

| Gene | Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Amplicon size (bp) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| SREBP1c | F: GCG CTA CCG GTC TTC TAT CA | 176 | NM_011480.4 |

| R: TGT GTG CAC TTC GTA GGG TC | |||

| PPARγ | F: CCG TGC AAG AGA TCA CAG AG | 159 | NM_011146.3 |

| R: GGC CCT CTG AGA TGA GGA C | |||

| C/EBPα | F: GCT GGA GTT GAC CAG TGA CA | 116 | NM_007678.3 |

| R: CCT TGA CCA AGG AGC TCT CA | |||

| FAS | F: CTA CCA GGC CAT CCG TAG TG | 157 | NM_007988.3 |

| R: ACA ATA TCC ACT CCC TGA ATC | |||

| GAPDH | F: CCC CTC TGG AAA GCT GTG G | 150 | NM_008084.3 |

| R: ACA TTG GGG GTA GGA ACA CG |

SREBP1c, Sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; C/EBPα, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha; FAS, fatty acid synthase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; F, Forward; R, Reverse.

2.7. Animal experiments

Male C57BL/6 N mice were obtained from Samtako (Osan, Korea). After acclimation for 1 week, mice were divided into 4 groups—group 1, normal diet (ND); group 2, high-fat diet (HFD); group 3, HFD with DRE 50 mg/kg; group 4, HFD with orlistat 50 mg/kg. There were 8 mice in each group. Each mouse was weighed individually and then averaged, and mice were fed water and experimental diet freely. Obesity was induced via feeding HFD for 4 weeks, and the increase in weight was identified in all groups except the ND group. After this, DRE 50 mg/kg and orlistat 50 mg/kg were administered by oral gavage for 6 weeks. In addition, mice were fed with HFD during DRE or orlistat treatment period. During the experiment, the room temperature was maintained at 22℃ under a 12-hour light/dark cycle (08:00-20:00). After the experiment, mice were fasted 12 h before sacrifice and the blood samples taken were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min. Triglyceride levels in the obtained serum were examined using Cobas 8000 (Roche, Germany). All experiments were performed with the approval of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Catholic University of Pusan.

2.8. Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The liver and white adipose tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 3-μm thickness. Each section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining and examined by microscopy (Olympus BX51, Olympus Optical Co., Japan).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (n = 3). Differences between the means of the individual groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science, Chicago, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxic effects using 3T3-L1 cells

To measure the cytotoxic effects of the fraction from D. racemosum in 3T3-L1 cells, 3T3-L1 cells were treated with various concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) of the D. racemosum fraction, and their cytotoxicity was measured at 48 h. Hexane, ethyl acetate, and butanol fractions at concentration of 50 μg/mL or below did not show cytotoxicity. The water fraction did not show cytotoxicity towards the 3T3-L1 cells at 100 μg/mL or below (Fig. 1). We therefore used concentrations that do not elicit cytotoxicity.

Fig. 1.

Effects of fraction from Distylium racemosum on 3T3-L1 cell viability.

(A) Hexane fraction, (B) Ethyl acetate fraction, (C) Butanol fraction, (D) Water fraction. 3T3-L1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) of D. racemosum fraction for 48 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Significant differences from control are indicated (p < 0.05).

3.2. Inhibitory effect on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells

To examine the inhibitory effect on adipogenesis, 3T3-L1 cells were treated with the fraction from D. racemosum for 7 days, and stained with Oil red O. Lipid accumulation was inhibited by DRE (Fig. 2). Hexane, butanol, and water fractions did not exhibit inhibitory effects against adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Adipogenesis and lipid accumulation in the 3T3-L1 cells were inhibited by over 80% following treatment with 50 μg/mL DRE (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effects of ethyl acetate fraction from Distylium racemosum on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells.

Lipid accumulation was measured by Oil red O staining. All photographs were taken using a microscope. Lipid accumulation was inhibited by DRE (magnification ×400).

Fig. 3.

Effects of fraction from Distylium racemosum on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells.

(A) Hexane fraction, (B) Ethyl acetate fraction, (C) Butanol fraction, (D) Water fraction. 3T3-L1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL) of D. racemosum fraction. Lipid accumulation was measured by Oil red O stain. The cells were eluted into 100% isopropanol and OD was measured at 500 nm. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Significant differences from control are indicated (p < 0.05).

3.3. Expression of adipogenic transcription factors in 3T3-L1 cells

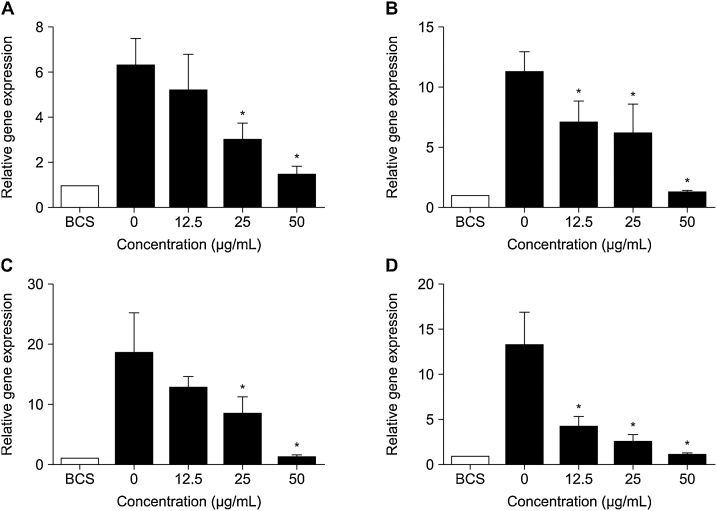

To examine whether the expression of adipogenic transcription factors is inhibited by DRE, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were treated with various concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL) of DRE and incubated for 7 days. The expression of SREBP1c, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FAS genes was inhibited by DRE. DRE inhibited adipocyte differentiation through suppression of SREBP1c, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FAS genes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of ethyl acetate fraction from Distylium racemosum on the gene expression.

(A) SREBP1c, (B) PPARγ, (C) C/EBPα, (D) FAS. Expression of adipogenic transcription factors was measured by qRT-PCR. SREBP1c, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FAS genes were inhibited by DRE in a dose-dependent manner. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Significant differences from control are indicated (p < 0.05).

3.4. Changes in body weights and food intake in mice

Changes in body weights and food intake of HFD-induced obese mice were examined after treatment with DRE. After four weeks of inducing obesity with HFD, the examination was conducted for six weeks. Ten weeks after the experiment, the average body weight increased by 8.6 g in the DRE (50 mg/kg) group and by 13.9 g in the HFD group, which implies a significantly lower rate of weight increase. The DRE group showed a similar rate of body weight gain as the positive control group, and the orlistat (50 mg/kg) group showed a body weight increase of 8.5 g. DRE treatment therefore has a significant influence on suppressing weight increase induced by the intake of an HFD. Food intake was lower in DRE and orlistat groups than in ND; however, there was no statistically significant difference (Table 2).

Table 2.

Body weight gain and food intake.

| Groups | Body weight gain (g) | Food intake (g/day) |

|---|---|---|

| ND | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 0.4 |

| HFD | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| DRE 50 mg/kg | 8.6 ± 2.2* | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| Orlistat 50 mg/kg | 8.5 ± 2.1* | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 8). Significant differences from the HFD group are indicated (p < 0.05).

3.5. Level of triglycerides in serum

The triglyceride levels in serum were 93.7 mg/dL in the ND, 114.3 mg/dL in HFD, 90.3 mg/dL in DRE (50 mg/kg), and 90.0 mg/dL orlistat (50 mg/kg) groups. The serum levels of triglyceride in the DRE and orlistat groups were significantly lower than those in the HFD group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of ethyl acetate fraction from Distylium racemosum on triglyceride level.

Levels of triglycerides were compared after a 6-week DRE treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 8). Significant differences from the HFD group are indicated (p < 0.05).

3.6. Morphological characteristics of liver and adipose tissue

Morphologic characteristics of liver and adipose tissue were observed through hematoxylin and eosin staining. The morphology in the HFD group was abnormal, with clear adipose accumulation in liver cells caused by HFD intake. In comparison, lipid accumulation was suppressed as revealed by the decrease in the number and size of lipid droplets in the DRE-treated group (Fig. 6). Adipocytes were larger in the HFD group than in the ND group, and those in the DRE-treated group were smaller than in the HFD group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Morphologic characteristics of liver tissue.

(A) ND group, (B) HFD group, (C) HFD with DRE 50 mg/kg, and (D) HFD with orlistat 50 mg/kg. Morphologic characteristics of liver tissue were observed through hematoxylin and eosin staining. Difference in liver tissue after the oral administration of DRE was confirmed compared with the HFD group (magnification ×100).

Fig. 7.

Morphologic characteristics of adipose tissue.

(A) ND group, (B) HFD group, (C) HFD with DRE 50 mg/kg, and (D) HFD with orlistat 50 mg/kg. Morphologic characteristics of adipose tissue were observed through hematoxylin and eosin staining. Difference in adipose tissue after the oral administration of DRE was confirmed compared with the HFD group (magnification ×100).

4. Discussion

Obesity, which is caused by an imbalance between energy intake and consumption, is an energy balance disorder that leads to the excessive lipid accumulation of white adipose tissue [13]. Obesity and overweight have become a serious health issue worldwide owing to the related higher risk of chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [14]. Various drugs are currently being developed to effectively control obesity, and there is an increasing interest in developing natural product-based drugs instead of using chemicals for safer long-term use [15]. In addition, as various diseases caused by obesity induce oxidative stress in the body, it is very important to develop drugs with anti-oxidative effects as well as anti-obesity effects.

The Jeju island, which is located in the southernmost part of Korea, is a native habitat for diverse plant communities. The therapeutic effects of extracts from these plants have been investigated in several studies; e.g. the radioprotective effects of Callophyllis japonica fractions, anti-obesity effects of Sasa quelpaertensis extracts, and anti-oxidative effects of Camellia japonica extracts have been reported [[16], [17], [18]].

In this study, fractions of D. racemosum were prepared according to polarity and their anti-obesity effects were verified. DRE influenced adipocyte production during the differentiation from pre-adipocytes to adipocytes at concentrations lower than 50 μg/mL, with no influence on 3T3-L1 cell survival rates; however, adipocyte production showed a concentration-dependent decrease. This result suggests that DRE inhibits lipid droplet production and suppresses lipid accumulation. In particular, at 50 μg/mL, less than 20% lipid accumulation was identified compared with that in the untreated control group, which indicates that DRE exhibits a strong ability to suppress lipid accumulation. Extracts of Plocamium telfairiae, seaweeds from Jeju Island, induced 42%, 26%, and 18% lipid accumulation at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL respectively. This is similar to the effect on lipid accumulation observed following treatment with 50 μg/mL of DRE [19].

Adipogenesis, which refers to the process by which pre-adipocytes are converted into adipocytes through reproduction and differentiation, is controlled by several genes. During this process, transcription factors, such as PPARγ, C/EBPα, and SREBP1c, play a pivotal role in controlling the adipocyte differentiation. In addition, through the expression of the SREBP1c gene, adipogenesis can be somewhat induced and is known to promote PPARγ production [20]. It was confirmed that DRE suppressed transcription factor expression in a concentration-dependent manner during adipose differentiation. The suppression of FAS expression, which contributes to lipogenesis, suggests inhibition of differentiation into adipocytes. Further, the expression ratio of adipogenic-specific proteins decreased depending on DRE concentration. Thus, the suppression of lipid accumulation was found to occur in 3T3-L1 cells as a result of the inhibition of major transcription factors and protein expression during adipose differentiation. Also, according to experiment with Panax ginseng leaf, Allium fistulosum L., and Solidago virgaurea var. gigantea extract, the extract has an effect on anti-obesity since it was noticed that the amount of gene expression that is related to adipogenesis has been decreasing [[21], [22], [23]].

HFD model has been widely used to identify anti-obesity effects. This study is to identify anti-obesity effects on HFD induced C57BL/6 mice. Experimental animals were divided into ND group, HFD group, DRE 50 mg/kg group and orlistat 50 mg/kg group. Weight increase rate was significantly decreased in DRE administered group compared with in HFD group. Also, triglyceride level was significantly decreased in DRE group compared with in HFD group. And after DRE administration, lipid accumulation in liver tissue was suppressed. Positive control group used in vivo, orlistat 50 mg/kg, revealed similar results to DRE 50 mg/kg group.

In conclusion, this study confirms that DRE exerts anti-obesity effects. DRE may therefore represent a promising source of functional materials for the prevention and treatment of obesity.

Transparency document

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grants from the Brain Busan 21 program.

References

- 1.Kang J.W., Nam D., Kim K.H., Huh J.E., Lee J.D. Effect of gambisan on the inhibition of adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Evid. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:789067. doi: 10.1155/2013/789067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhurandhar N.V. A framework for identification of infections that contribute to human obesity. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:963–969. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . 2015. Obesity and Overweight.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg A.S., Obin M.S. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83:461S–465S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Y., Li Y., Zhao T., Wang Y., Sun C. Ursolic acid inhibits adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes through LKB1/AMPK pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang S.W., Kang S.I., Shin H.S., Yoon S.A., Kim J.H., Ko H.C., Kim S.J. Sasa quelpaertensis Nakai extract and its constituent p-coumaric acid inhibit adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells through activation of the AMPK pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;59:380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo J.B., Choe S.S., Jeong H.W., Park S.W., Shin H.J., Choi S.M., Park J.Y., Choi E.W., Kim J.B., Seen D.S., Jeong J.Y., Lee T.G. Anti-obesity effects of Lysimachia foenum-graecum characterized by decreased adipogenesis and regulated lipid metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2011;43:205–215. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.4.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H.M., Yang G., Ahn T.G., Kim M.D., Nugroho A., Park H.J., Lee K.T., Park W., An H.J. Antiadipogenic effects of aster glehni extract: in vivo and in vitro effects. Evid. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:859624. doi: 10.1155/2013/859624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko R.K., Lee S.J., Hyun C.G., Lee N.H. New dibenzofurans from the branches of distylium racemosum Sieb. et Zucc. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009;30:1376–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee W.Y., Ahn J.K., Park Y.K., Park S.Y., Kim Y.M., Rhee H.I. Inhibitory effects of proanthocyanidin extracted from distylium racemosum on a-amylase and a-glucosidase activities. Kor. J. Pharmacogn. 2004;35:271–275. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J.A., Yang S.Y., Wamiru A., McMahon J.B., Le Grice S.F., Beutler J.A., Kim Y.H. New monoterpene glycosides and phenolic compounds from Distylium racemosum and their inhibitory activity against ribonuclease H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2840–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Y., Song S.J., Keum N., Park T. Olive leaf extract attenuates obesity in high-fat diet-fed mice by modulating the expression of molecules involved in adipogenesis and thermogenesis. Evid. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014;2014:971890. doi: 10.1155/2014/971890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M.R., Kim B.C., Kim R., Oh H.I., Kim H.K., Choi K.J., Sung C.K. Anti-obesity effects of black ginseng extract in high fat diet-fed mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2013;37:308–349. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baek J., Lee J., Kim K., Kim T., Kim D., Kim C., Tsutomu K., Ochir S., Lee K., Park C.H., Lee J., Choe M. Inhibitory effects of Capsicum annuum L. water extracts on lipoprotein lipase activity in 3T3-L1 cells. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2013;7:96–102. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2013.7.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J., Moon C., Kim H., Jeong J., Lee J., Hyun J.W., Park J.W., Moon M.Y., Lee N.H., Kim S.H., Jee Y., Shin T. The radioprotective effects of the hexane and ethyl acetate extracts of Callophyllis japonica in mice that undergo whole body irradiation. J. Vet. Sci. 2008;9:281–284. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang S.I., Shin H.S., Kim H.M., Hong Y.S., Yoon S.A., Kang S.W., Kim J.H., Ko H.C., Kim S.J. Anti-obesity properties of a Sasa quelpaertensis extract in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012;76:755–761. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piao M.J., Yoo E.S., Koh Y.S., Kang H.K., Kim J., Kim Y.J., Kang H.H., Hyun J.W. Antioxidant effects of the ethanol extract from flower of Camellia japonica via scavenging of reactive oxygen species and induction of antioxidant enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:2618–2630. doi: 10.3390/ijms12042618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang M.C., Kang N., Ko S.C., Kim Y.B., Jeon Y.J. Anti-obesity effects of seaweeds of Jeju Island on the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and obese mice fed a high-fat diet. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016;90:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer S.R. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S.G., Lee Y.J., Jang M.H., Kwon T.R., Nam J.O. Panax ginseng leaf extracts exert anti-obesity effects in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Nutrients. 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/nu9090999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung Y.Y., Yoon T., Kim S.J., Yang W.K., Kim H.K. Anti-obesity activity of Allium fistulosum L. extract by down-regulation of the expression of lipogenic genes in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2011;4:431–435. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z., Kim J.H., Jang Y.S., Kim C.H., Lee J.Y., Lim S.S. Anti-obesity effect of Solidago virgaurea var. gigantea extract through regulation of adipogenesis and lipogenesis pathways in high-fat diet-induced obese mice (C57BL/6N) Food Nutr. Res. 2017;61:1273479. doi: 10.1080/16546628.2016.1273479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.