Abstract

The conformational and rheological properties of active filaments/polymers exposed to shear flow are studied analytically. Using the continuous Gaussian semiflexible polymer model extended by the activity, we derive analytical expressions for the dependence of the deformation, orientation, relaxation times, and viscosity on the persistence length, shear rate, and activity. The model yields a Weissenberg-number dependent shear-induced deformation, alignment, and shear thinning behavior, similarly to the passive counterpart. Thereby, the model shows an intimate coupling between activity and shear flow. As a consequence, activity enhances the shear-induced polymer deformation for flexible polymers. For semiflexible polymers/filaments, a nonmonotonic deformation is obtained because of the activity-induced shrinkage at moderate and swelling at large activities. Independent of stiffness, activity-induced swelling facilitates and enhances alignment and shear thinning compared to a passive polymer. In the asymptotic limit of large activities, a polymer length- and stiffness-independent behavior is obtained, with universal shear-rate dependencies for the conformations, dynamics, and rheology.

Keywords: semiflexible polymer, active Brownian particle, active polymer, polymer conformations, polymer dynamics, colored noise, viscosity, rheology

1. Introduction

Active matter is composed of agents which either convert internal energy or exploit energy from the environment to generate directed motion [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The associated out-of-equilibrium character of active matter is the origin of a number of fascinating phenomena, such as activity-driven phase separation or large-scale collective motion [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. On the nano- and microscale, biology provides a plethora of active agents ranging from enzymes [14,15] and the cytoskeleton in living cells [1,3,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] to sperm, algae, bacteria, and a diversity of other planktonic microorganisms [1,4,23,24]. Furthermore, artificial active particles have been synthesized utilizing various concepts [5,25,26,27,28,29]. Thereby, active agents exhibit a variety of forms and shapes—from (near) spherical (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Volvox) to cylindrical (Proteus mirabilis [30], self-assembled dinoflagellates [31,32]), and filamentous, polymer-like structures (actin filaments, microtubules, linear assemblies of Janus particles [33,34]). In fact, active systems with internal degrees of freedom, such as linear chains [7,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] or other forms of organization [33,34,55,56], denoted as “active colloidal molecules” in Ref. [34], are particularly interesting and give rise to novel conformational [39,41,47,52], dynamical [45,53,57,58,59], and collective phenomena [12,16,56,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Examples range from activity-induced polymer swelling and shrinkage [7,39,41,47,52], enhanced diffusive motion and dynamics [40,41,53,59]—as observed in microtubuli [67], actin filaments [68], chromosomal loci in simple organisms [69,70], or in the chromatin dynamics in eukaryotes [71]—to mesoscale turbulence [12,56] or streaming nematics [60,65].

In theoretical and simulation studies, filamentous, polymer-like active agents are typically described as semiflexible polymers composed of monomers, which are propelled by an active force. The properties of the active force depend on the system of interest. Actin filaments or microtubules in motility assays or motor-protein carpets [61] are driven by tangential forces with respect to the filament contour [35,43,45,66]. Alternatively, polymers comprised of active Brownian particles (ABPs) are driven by active forces, which change their propulsion direction independently in a diffusive manner [5,10,47,52,72]. So far, no polymer-like assembly of ABPs has been synthesized. However, activity can also be considered as an external random colored-noise force experienced by the polymer, as discussed in Refs. [4,6,51,52,53]. In this context, “activity” is an extension of the theoretical description toward more complex out-of-equilibrium environments, which break detailed balance and the fluctuation–dissipation theorem [73].

In this article, the conformational and rheological properties of an active polymer subject to colored noise and exposed to shear flow are studied. In particular, the interplay between activity and shear flow is investigated. The effect of propulsion on the rheology of entangled, isotropic solutions of tangentially driven semiflexible polymers has been addressed in Ref. [35], and an accelerated relaxation has be found at long times, resulting in a reduced low-frequency viscosity. Specifically, the transport of microorganisms and their assemblies, which is omnipresent in nature, e.g., plankton in aquatic environments and microfluidic devices, is strongly affected by fluid flow [74]. In such habitats, shear flow is pervasive and determines the destination of microorganisms. Our goal is to unravel the properties of semiflexible filamentous polymers in such an out-of-equilibrium environment induced by both colored noise and fluid flow. Our studies reveal an intimate coupling of activity and shear flow, which leads to distinct differences in the non-equilibrium polymer conformations, dynamics, and rheology. Specifically, shear-rate dependent power-laws are modified at large activities. It is noteworthy that polymer-length- and stiffness-independent universal dependencies on the shear rate are predicted in the asymptotic limit of large activities.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the model of the active polymer in shear flow and presents the equations of motion and their solution. In Section 3, results for the shear-rate dependence of the relaxation times and conformational properties are presented for various activities and stiffness. The viscosity of the polymer is considered in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the various findings, and Section 6 summarizes the major results of our study.

2. Model: Active Brownian Filament/Polymer

2.1. Equation of Motion

The filament/polymer is described by the Gaussian semiflexible polymer model [75,76,77,78,79,80]. Thereby, the polymer of length L is considered as a continuous, differentiable space curve , with the contour coordinate s (), and the time t. The activity is introduced by assigning an active velocity to every point (cf. Figure 1). The equation of motion of is then given by [52,53]

| (1) |

with the boundary conditions

| (2) |

Figure 1.

Illustration of the continuous semiflexible active polymer (ABPO) in shear flow. The arrows and colors indicate the orientation of the active velocity .

The terms with the second and fourth derivative in Equation (1) account for the entropy elasticity and bending stiffness, respectively, for thermal fluctuations, and for the shear flow, with the shear-rate tensor . The Lagrangian multipliers , , and are determined by constraints [81,82]. In general, this yields and for a polymer in three dimensions, where in terms of the persistence length [75,82]. The Lagrangian multiplier , denoted as stretching coefficient, is determined in a mean-field manner via the global constraint [52,75,82]:

| (3) |

As discussed in Ref. [52], the active velocity can be considered as external colored noise experienced by the respective polymer site, the picture adopted here, or as intrinsic polymer property originating from self-propulsion. For an identical mathematical formulation, the active site has then to be described by an active Ornstein–Uhlenbeck particle (AOUP) [73,83]. However, also an active Brownian particle (ABP) can be considered, as long as only second moments of the active velocity correlation function are relevant [57]. In any case, the active velocity is described by a diffusive process—Brownian motion—either for the propulsion direction only (ABPs) [4,5,6,10,84,85], or for the individual Cartesian components, i.e., the magnitude of is changing too (AOUPs) [4,52,73,83]. Independent of the details of the underlaying stochastic (active) processes, we denote our polymer as active Brownian polymer (ABPO). Hence, the active velocity, , is described by a non-Markovian, but Gaussian stochastic process with zero mean and the second moments [52,53,73]

| (4) |

i.e., the polymer is exposed to colored noise [52,53,73]. Here, is the propulsion velocity, the damping factor can be related to the rotational diffusion coefficient of a spherical colloid in three dimensions via , and . We introduce the length scale l in the continuum representation of a semiflexible polymer. Thereby, the ratio can be interpreted as the number of uniformly distributed active sites along the polymer. In the flexible limit, we set , which leads to the relation . The effect of the ratio on the conformational properties in the absence of shear has briefly been addressed in Ref. [52]. The choice is motivated by discrete bead-spring polymers, typically used in computer simulations [57,86], where every monomer is an ABP. The stochastic process of the translational motion is assumed to be stationary, Markovian, and Gaussian with zero mean and the second moments

| (5) |

where T is the temperature, the Boltzmann constant, and the translational friction coefficient per length. The latter is related with the translational, thermal diffusion coefficient via . Finally, shear is applied along the x-direction and the gradient along the y-direction of the Cartesian reference frame. Hence, the shear-rate tensor is given by , where is the shear rate.

2.2. Eigenfunction Expansion

The linear equation of motion (1) is solved by the eigenfunction expansion

| (6) |

and an analogous representation of and , in terms of the eigenfunctions of the eigenvalue equation [52,76]

| (7) |

The respective eigenfunctions are

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

with the relations between the wave numbers , , and the eigenvalues ()

| (11) |

The eigenfunction accounts for the polymer’s center of mass motion. The s are normalization coefficients, and the wave numbers are determined by the boundary conditions (2).

Insertion of Equation (6) into Equation (1) yields the equation of motion for the mode amplitudes ,

| (12) |

with respective amplitudes and of the active velocity and stochastic force, and the relaxation times

| (13) |

The stationary-state solution of Equation (12) for is

| (14) |

and for

| (15) |

2.3. Mode–Amplitude Correlation Functions

The time correlation functions of the mode amplitudes can be calculated straightforwardly by Equation (14), which yields , with (, )

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

2.4. Inextensibility and Stretching Coefficient

The inextensibility constraint (3), together with the eigenfunction expansion and the correlation functions (16)–(18), leads to the equation

| (19) |

to determine , where and

| (20) |

In general, Equation (19) has to be solved numerically. However, the sum over the mode numbers can be evaluated in the limit , or even for moderate , for larger activities [53], due to the dominance of the stretching modes in these limits, i.e., and , where is the Rouse relaxation time of the passive polymer [76,87]. Here, the Péclet number and other relevant dimensionless quantities, such as the Weissenberg number , the ratio between the translational and rotational diffusion coefficient , and the scaled stretching coefficient , in terms of the value at equilibrium, , are introduced as

| (21) |

Thereby, is the longest polymer relaxation time at zero shear but in the presence of activity. Combined with results from Refs. [52,88], we find from Equation (19)

| (22) |

where for the evaluation of the term proportional to only the first mode, , has been taken into account; the deviation to the full sum is below for all and . The last term on the left-hand side reflects the coupling between activity and shear flow.

The following asymptotic dependencies for the stretching coefficient are obtained:

-

(i)Passive semiflexible polymer in shear flow, i.e., (for details, cf. Ref. [88])

-

-For and

(23) -

-For and

(24)

-

-

- (ii)

-

(iii)Active flexible polymer in shear flow, ,

-

-For , , and (with Equation (25))

(27) -

-For , i.e.,

(28)

Hence, in the limit , exhibits a crossover from a dependence for to a dependence for . The latter characteristics are different from the passive case and are a consequence of the coupling between activity and shear flow.

-

-

The full numerical solution for the stretching coefficient is presented in Figure 2 as a function of the Weissenberg number and for various activities. We set for the number of active sites. Hence, when changing , we change the persistence length at a fixed contour length in order to maintain the active-site density. As illustrated for and , exhibits a crossover from a dependence at low to the relation for and sufficiently large , in agreement with the theoretical limits, Equations (27) and (28). We like to emphasize that approaches the asymptotic dependence

| (29) |

for . Hence, a universal, activity- and -independent behavior is predicted. For completeness, Figure 3 illustrates the dependence of on the Péclet number for the Weissenberg numbers (left) and (right). The predicted power-law dependencies (Equation (25) for , and Equation (28) for and ) and scaling with respect to are recovered. Figure 2 shows a shift of the crossover from the to the dependence towards smaller with increasing . This crossover strongly depends on , and shifts to larger with increasing . Hence, for a larger number of active sites, no crossover could be observed anymore for suitable Weissenberg numbers. On the contrary, for a smaller number , the crossover appears already at smaller . In the extreme case of , a behavior similar to an active dumbbell in shear flow appears [51].

Figure 2.

Stretching coefficient normalized by the value of the active, non-sheared system as function of the Weissenberg number for the Péclet numbers and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) (stiff) and (right) (flexible polymer). The number of active sites is and the diffusion coefficient ratio .

Figure 3.

Stretching coefficient as a function of the Péclet number for the stiffness and (bottom to top). The Weissenberg numbers are (left) [52] and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

3. Dynamics and Conformations

3.1. Relaxation Times

The relaxation times (13) depend on the shear rate (), activity (), and persistence length (p) via the stretching coefficient . In the limit of a highly flexible polymer, the relaxation time is . Hence, the mode-number dependence of is unaffected by the nonequilibrium character of the dynamics. However, the presence of indicates the fundamental importance to account for the inextensibility of the polymer. Since is a monotonically increasing function of and , activity and shear flow always accelerate the relaxation process and the relaxation times become shorter [35,53].

Figure 4 displays the numerically obtained longest relaxation time as a function of the Weissenberg number for various and the stiffness (stiff) and (flexible polymer). For and small Péclet numbers (), the relaxation time , corresponding to the rotation relaxation time of a rigid polymer, dominates over all other (bending) relaxation times [53,76]. Hence, the relaxation times of Figure 4 (left) are not simply proportional to in this limit. However, with increasing , bending contributions gradually vanish and the asymptotic dependence is assumed. According to Equation (29), the ratio is then independent of and . In Figure 4 (right) for flexible polymers, bending modes are negligibly small and the relation applies for all . Consequently, exhibits the power-law dependencies of Equations (23), (27), and (28).

Figure 4.

Longest polymer relaxation time normalized by the longest relaxation time of the active, non-sheared system () as function of the Weissenberg number for the Péclet numbers and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

We like to emphasize that the shear-rate dependency is a consequence of the activity of the polymer and emerges from the coupling of activity and shear (cf. Equation (22)). The passive polymer under shear exhibits the dependence , which we find for small also for the active polymer. A dumbbell of active monomers exhibits a similar coupling of activity and shear and, correspondingly, shows a comparable crossover of the relaxation times [88].

Figure 5 illustrates the mode-number dependence of the relaxation times for various activities and shear rates. For semiflexible polymers, activity and shear flow modify the relaxation behavior because stretching modes () dominate over bending modes () with increasing activity and flow strength. Bending stiffness remains dominant at larger mode numbers. Activity as well as flow induce a transition from semiflexible to flexible polymer behavior, which extends to smaller and smaller length scales with increasing and .

Figure 5.

Mode-number dependence of the relaxation times normalized by the longest relaxation time for the Péclet numbers , and (different colors and symbols; from left to right), and the Weissenberg numbers , and (different tone, bright to dark, for every color). The persistence length is and .

3.2. Radius of Gyration

The polymer conformations are characterized by the radius of gyration tensor G, with the components

| (30) |

where is the center-of-mass position of the polymer. Insertion of the eigenfunction expansion (6) yields

| (31) |

in terms of the mode-amplitude correlation functions (Equations (16)–(18)).

Figure 6 depicts the radius of gyration-tensor component along the flow direction for rather stiff () and highly flexible () polymers. Note that only the excess deformation due to shear is shown. Activity leads to additional conformational changes, which are included in . As for passive semiflexible polymers, shear leads to an extension and alignment along the flow direction, which saturates at large shear rates because of the finite polymer contour length [88,89]. The actual asymptotic stretching for depends on the activity. At , the asymptotic limits are for [88], and , , hence for . It is noteworthy that the latter limit is independent of , i.e., it applies for every stiffness, and the same asymptotic behavior is displayed in Figure 6 (left) and (right). Shear flow leads to an additional stretching of the active polymer, particularly for , and not simply to an orientational alignment as for a rod, where for [88], since . However, the difference of the asymptotic values for and , respectively, can be substantial, since of the passive system depends on polymer length. The polymer pre-stretching by activity reduces the possible stretching by shear. The asymptotic limits for at are and , hence, , in agreement with Figure 6 (left). Note that depends non-monotonically on the Péclet number at small . The ratio increases with increasing at small and decreases again for (cf. Figure 6 (left)). In contrast, decrease monotonically with increasing at large (cf. Figure 6 (right)). In any case, shear leads to an alignment and additional stretching even in the limit of very large activity.

Figure 6.

Radius of gyration-tensor component along the flow direction normalized by the value at zero shear as function of the Weissenberg number for the Péclet numbers and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

The radius of gyration-tensor component along the gradient direction is displayed in Figure 7. Note that . Consistent with the extension in the flow direction, a polymer shrinks in the transverse direction. We find the asymptotic dependencies for and , for , and for . In the limit , independent of . Again, the latter dependence is specific for active systems, since passive polymers typically show a weaker dependence on the Weissenberg number [88,89].

Figure 7.

Radius of gyration-tensor component along the gradient direction normalized by the value at zero shear as function of the Weissenberg number for the Péclet numbers and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

3.3. Alignment

Anisotropic objects in shear flow are preferentially aligned along the flow direction [88,89]. We characterize the extent of alignment by the angle between the eigenvector of the gyration tensor with the largest eigenvalue and the flow direction. The alignment angle is conveniently obtained from the relation

| (32) |

where

| (33) |

In the asymptotic limit , i.e., , this expression reduces to [51]

| (34) |

Hence, we obtain the asymptotic dependence for and for , respectively. The various regimes are displayed in Figure 8. For , the stretching coefficient is approximately unity and decreases as . For large Weissenberg numbers, the shear-rate dependence of becomes important and changes the dependence to for and to for .

Figure 8.

Shear-induced polymer alignment, characterized by the angle between the eigenvector of the gyration tensor with the largest eigenvalue and the flow direction, as function of the Weissenberg number . The Péclet numbers are and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

4. Rheology: Viscosity

The polymer contribution to the viscosity of a dilute solution follows from the virial expression of the stress tensor

| (35) |

via , where F is the intramolecular force of Equation (1) and the polymer concentration. The active force, , does not contribute to the stress tensor. Evaluation of the average in Equation (35) yields

| (36) |

which depends via the stretching coefficient on the shear rate.

The zero-shear viscosity follows from Equation (36) via the stretching coefficient . Its dependence on is shown in Figure 9. The viscosity at zero shear and zero Péclet number is given by for , and by for . In the latter case, the first mode, , describing the rotational motion of the rodlike polymer, dominates the sum over the relaxation times [76]. For flexible polymers, where , the zero-shear viscosity increases monotonically with increasing , and saturates at in the limit . Thereby, the viscosity increase, associated with the monotonic swelling of the polymer with increasing activity [52], is substantial because . With increasing stiffness, the activity-induced polymer shrinkage (cf. Ref. [52]) implies a decrease in , followed by an increase due to a reswelling of the polymer for , and the asymptotic value is assumed. Here, the activity dependence of is significantly smaller than for flexible polymers, and reduces to a factor below two in the rod limit.

Figure 9.

Zero-shear viscosity normalized by the zero-shear viscosity of a passive polymer as function of the Péclet number for the polymer stiffness , and (top to bottom at , dark to bright color). The number of active sites is and .

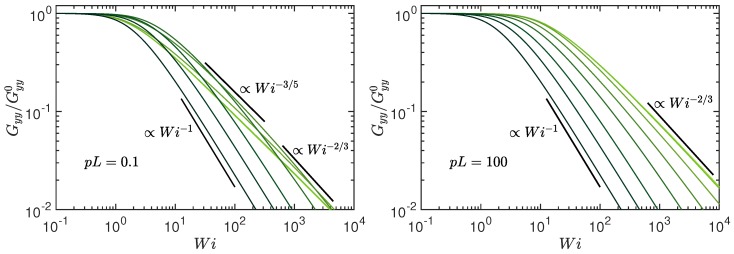

The shear-rate dependence of the viscosity , normalized by , is displayed in Figure 10 for various Péclet numbers. Independent of persistence length and activity, the polymers exhibit shear thinning. However, the dependence on the Weissenberg number is strongly affected by the activity. The behavior of passive semiflexible polymers, where = 0, has been discussed theoretically in Ref. [88]. For such polymers, the viscosity exhibits the asymptotic dependencies for : for and for . In fact, for large stiffness, , there is a cross-over regime with an approximate power-law drop of as indicated in Figure 10 (left). Here, both bending and stretching modes contribute with a Weissenberg number-dependent weight. Activity substantially changes the shear-thinning behavior, and, with increasing , the ratio decreases faster with increasing shear rate. From Equation (36), we obtain the relation

| (37) |

in the limit , which is independent of . Hence, activity enhances shear thinning considerably.

Figure 10.

Shear viscosity normalized by the viscosity of a non-sheared, active polymer as function of the Weissenberg number for the Péclet numbers and ∞ (bright to dark color); (left) and (right) . The number of active sites is and .

Shear thinning of passive polymers, where , has intensively been studied experimentally [90,91], theoretically [88], and by simulations [89,92,93,94,95,96,97]. Specifically, measurements on DNA molecules provided insight into the behavior of individual polymers [91]. These experiments and simulations often predicted a power-law decay of the viscosity in the shear-thinning regime, with exponents in the range 1/2 to 2/3. The spread is partially explained by the very broad crossover regime between the zero-shear viscosity and the asymptotic dependence for . In any case, activity is predicted to lead to a significantly stronger shear-thinning effect.

5. Discussion

The coupling between shear flow and activity, as is visible in the correlation functions (16)–(18), determines the characteristics of an ABPO in shear flow. The shear-rate dependence of all properties—conformational, dynamical, and rheological—are modified by activity. Thereby, the determining factor is the polymer inextensibility, which is reflected in the activity and shear-rate dependence of the stretching coefficient in our coarse-grained description. In particular, the asymptotic behavior for is naturally governed by inextensibility. As far as the dynamics is concerned, we find a weaker variation of the relaxation times with shear rate at large activities compared to a passive polymer, with the longest relaxation time changing from a dependence of a passive polymer to a decay for . In turn, this results in a change of the shrinkage of the radius of gyration components from a to a dependence, a similar change for the viscosity , and a change of the alignment from a to a dependence with increasing at . As has already been discussed in Ref. [52], flexible and semiflexible ABPO show the same activity-induced swelling behavior for , independent of . Consequently, a universal shear-flow behavior is obtained in that limit. For all conformational (), dynamical (), and rheological () properties, universal curves are obtained, with shear-rate dependencies differing from those of a passive system. The behavior originates from the dominance of the flexible modes () in the relaxation behavior for all stiffness caused by activity.

Active dumbbells already exhibit various of the discussed shear-induced characteristics [51]. However, the polymer nature, with the many more internal degrees of freedom, provides additional features and means of controlling active properties. Specifically, the number of active sites, , is important. As our study shows, the crossover from the power laws valid for passive polymers to those of an ABPO at depends crucially on . With increasing , the power laws for appear at much larger Weissenberg numbers only. Depending on the size of the polymer, the Weissenberg numbers of the crossover could exceed experimentally accessible values. For computer simulations of an ABPO described as bead-spring polymer [57,86], this aspect is of minor concern because typically every monomer is considered as an ABP and not too long polymers are studied.

6. Conclusions

We have presented analytical results for active semiflexible polymers under shear flow. The Gaussian semiflexible polymer model is adopted, which takes into account the polymer inextensibility in a mean-field manner by a constraint for the contour length [75,80,82]. Activity is modeled as a colored noise force with an exponential temporal correlation. The linearity of the equation of motion, even in the presence of shear flow, allows for its analytical solution.

We have calculated the relaxation times, deformation, alignment, and viscosity as a function of shear rate. Each of these quantities shows a strong dependence on shear rate. Thereby, activity affects the shear response. An important aspect of a polymer in shear flow is its stretching and alignment along the flow direction, and its shrinkage transverse to it [88,89,95]. Activity enhances these aspects for flexible polymers. Semiflexible polymers show a nonmonotonic deformation behavior as a result of an activity-induced shrinkage at moderate Péclet numbers and a swelling at larger , where the latter is similar to that of flexible polymers at the same [52]. The activity-induced preference in alignment leads to a more pronounced shear thinning of highly active polymers, i.e., activity enhances shear thinning. All polymers exhibit the same shear-rate dependence in the limit , and, consequently, a universal behavior is obtained.

The active polymer relaxation behavior is governed by two processes, namely the diffusive dynamics of the active velocity, characterized by , and the relaxation times of the polymer. It remains to be analyzed how these competing processes determine the overall relaxation dynamics, e.g., of the end-to-end vector, and diffusion of the ABPO in the presence of shear flow.

References

Author Contributions

R.G.W. and G.G. conceived and designed the theoretical study; A.M.-G. and R.G.W. performed the analytical calculations; R.G.W., A.M.-G., and G.G. wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant agreement No. 674979-NANOTRANS, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the priority program SPP 1726 “Microswimmers—from Single Particle Motion to Collective Behaviour”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Ramaswamy S. The mechanics and statistics of active matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010;1:323–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-070909-104101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romanczuk P., Bär M., Ebeling W., Lindner B., Schimansky-Geier L. Active Brownian Particles. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2012;202:1–162. doi: 10.1140/epjst/e2012-01529-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchetti M.C., Joanny J.F., Ramaswamy S., Liverpool T.B., Prost J., Rao M., Simha R.A. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013;85:1143. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.85.1143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elgeti J., Winkler R.G., Gompper G. Physics of microswimmers—Single particle motion and collective behavior: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015;78:056601. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/78/5/056601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechinger C., Di Leonardo R., Löwen H., Reichhardt C., Volpe G., Volpe G. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016;88:045006. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.88.045006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchetti M.C., Fily Y., Henkes S., Patch A., Yllanes D. Minimal model of active colloids highlights the role of mechanical interactions in controlling the emergent behavior of active matter. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;21:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2016.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler R.G., Elgeti J., Gompper G. Active Polymers—Emergent Conformational and Dynamical Properties: A Brief Review. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2017;86:101014. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.86.101014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauga E., Powers T.R. The hydrodynamics of swimming microorganisms. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009;72:096601. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/72/9/096601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vicsek T., Zafeiris A. Collective motion. Phys. Rep. 2012;517:71–140. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wysocki A., Winkler R.G., Gompper G. Cooperative motion of active Brownian spheres in three-dimensional dense suspensions. EPL. 2014;105:48004. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/105/48004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zöttl A., Stark H. Emergent behavior in active colloids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2016;28:253001. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/28/25/253001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duman O., Isele-Holder R.E., Elgeti J., Gompper G. Collective dynamics of self-propelled semiflexible filaments. Soft Matter. 2018;14:4483–4494. doi: 10.1039/C8SM00282G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin-Gomez A., Levis D., Diaz-Guilera A., Pagonabarraga I. Collective motion of active Brownian particles with polar alignment. Soft Matter. 2018;14:2610–2618. doi: 10.1039/C8SM00020D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muddana H.S., Sengupta S., Mallouk T.E., Sen A., Butler P.J. Substrate Catalysis Enhances Single-Enzyme Diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2110–2111. doi: 10.1021/ja908773a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dey K.K., Das S., Poyton M.F., Sengupta S., Butler P.J., Cremer P.S., Sen A. Chemotactic Separation of Enzymes. ACS Nano. 2014;8:11941–11949. doi: 10.1021/nn504418u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nédélec F.J., Surrey T., Maggs A.C., Leibler S. Self-organization of microtubules and motors. Nature. 1997;389:305. doi: 10.1038/38532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard J. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruse K., Joanny J.F., Jülicher F., Prost J., Sekimoto K. Asters, Vortices, and Rotating Spirals in Active Gels of Polar Filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:078101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.078101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bausch A.R., Kroy K. A bottom-up approach to cell mechanics. Nat. Phys. 2006;2:231. doi: 10.1038/nphys260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jülicher F., Kruse K., Prost J., Joanny J.F. Active behavior of the cytoskeleton. Phys. Rep. 2007;449:3–28. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaller V., Weber C., Semmrich C., Frey E., Bausch A.R. Polar patterns of driven filaments. Nature. 2010;467:73. doi: 10.1038/nature09312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prost J., Jülicher F., Joanny J.F. Active gel physics. Nat. Phys. 2015;11:111. doi: 10.1038/nphys3224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg H.C. E. Coli in Motion. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2004. (Biological and Medical Physics Series). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guasto J.S., Rusconi R., Stocker R. Fluid Mechanics of Planktonic Microorganisms. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2011;44:373–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-fluid-120710-101156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howse J.R., Jones R.A.L., Ryan A.J., Gough T., Vafabakhsh R., Golestanian R. Self-Motile Colloidal Particles: From Directed Propulsion to Random Walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:048102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.048102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volpe G., Buttinoni I., Vogt D., Kümmerer H.J., Bechinger C. Microswimmers in patterned environments. Soft Matter. 2011;7:8810–8815. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05960b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thutupalli S., Seemann R., Herminghaus S. Swarming behavior of simple model squirmers. New J. Phys. 2011;13:073021. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/13/7/073021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagen B., Kümmel F., Wittkowski R., Takagi D., Löwen H., Bechinger C. Gravitaxis of asymmetric self-propelled colloidal particles. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maass C.C., Krüger C., Herminghaus S., Bahr C. Swimming Droplets. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2016;7:171–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031115-011517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Copeland M.F., Weibel D.B. Bacterial swarming: A model system for studying dynamic self-assembly. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1174–1187. doi: 10.1039/b812146j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selander E., Jakobsen H.H., Lombard F., Kiørboe T. Grazer cues induce stealth behavior in marine dinoflagellates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4030–4034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011870108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohn M.H., Seo K.W., Choi Y.S., Lee S.J., Kang Y.S., Kang Y.S. Determination of the swimming trajectory and speed of chain-forming dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides with digital holographic particle tracking velocimetry. Mar. Biol. 2011;158:561–570. doi: 10.1007/s00227-010-1581-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan J., Han M., Zhang J., Xu C., Luijten E., Granick S. Reconfiguring active particles by electrostatic imbalance. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:1095. doi: 10.1038/nmat4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Löwen H. Active colloidal molecules. EPL. 2018;121:58001. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/121/58001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liverpool T.B., Maggs A.C., Ajdari A. Viscoelasticity of Solutions of Motile Polymers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:4171. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarkar D., Thakur S., Tao Y.G., Kapral R. Ring closure dynamics for a chemically active polymer. Soft Matter. 2014;10:9577–9584. doi: 10.1039/C4SM01941E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chelakkot R., Gopinath A., Mahadevan L., Hagan M.F. Flagellar dynamics of a connected chain of active, polar, Brownian particles. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2014;11:20130884. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loi D., Mossa S., Cugliandolo L.F. Non-conservative forces and effective temperatures in active polymers. Soft Matter. 2011;7:10193–10209. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05819c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harder J., Valeriani C., Cacciuto A. Activity-induced collapse and reexpansion of rigid polymers. Phys. Rev. E. 2014;90:062312. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.90.062312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh A., Gov N.S. Dynamics of Active Semiflexible Polymers. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin J., Cherstvy A.G., Kim W.K., Metzler R. Facilitation of polymer looping and giant polymer diffusivity in crowded solutions of active particles. New J. Phys. 2015;17:113008. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/17/11/113008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isele-Holder R.E., Elgeti J., Gompper G. Self-propelled worm-like filaments: Spontaneous spiral formation, structure, and dynamics. Soft Matter. 2015;11:7181–7190. doi: 10.1039/C5SM01683E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isele-Holder R.E., Jager J., Saggiorato G., Elgeti J., Gompper G. Dynamics of self-propelled filaments pushing a load. Soft Matter. 2016;12:8495–8505. doi: 10.1039/C6SM01094F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laskar A., Adhikari R. Brownian microhydrodynamics of active filaments. Soft Matter. 2015;11:9073–9085. doi: 10.1039/C5SM02021B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang H., Hou Z. Motion transition of active filaments: Rotation without hydrodynamic interactions. Soft Matter. 2014;10:1012–1017. doi: 10.1039/c3sm52291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babel S., Löwen H., Menzel A.M. Dynamics of a linear magnetic “microswimmer molecule”. EPL. 2016;113:58003. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/113/58003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaiser A., Löwen H. Unusual swelling of a polymer in a bacterial bath. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:044903. doi: 10.1063/1.4891095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valeriani C., Li M., Novosel J., Arlt J., Marenduzzo D. Colloids in a bacterial bath: Simulations and experiments. Soft Matter. 2011;7:5228–5238. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05260h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suma A., Gonnella G., Marenduzzo D., Orlandini E. Motility-induced phase separation in an active dumbbell fluid. EPL. 2014;108:56004. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/108/56004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cugliandolo L.F., Gonnella G., Suma A. Rotational and translational diffusion in an interacting active dumbbell system. Phys. Rev. E. 2015;91:062124. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.062124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winkler R.G. Dynamics of flexible active Brownian dumbbells in the absence and the presence of shear flow. Soft Matter. 2016;12:3737–3749. doi: 10.1039/C5SM02965A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisenstecken T., Gompper G., Winkler R.G. Conformational Properties of Active Semiflexible Polymers. Polymers. 2016;8:304. doi: 10.3390/polym8080304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisenstecken T., Gompper G., Winkler R.G. Internal dynamics of semiflexible polymers with active noise. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;146:154903. doi: 10.1063/1.4981012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siebert J.T., Letz J., Speck T., Virnau P. Phase behavior of active Brownian disks, spheres, and dimers. Soft Matter. 2017;13:1020–1026. doi: 10.1039/C6SM02622B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Küchler N., Löwen H., Menzel A.M. Getting drowned in a swirl: Deformable bead-spring model microswimmers in external flow fields. Phys. Rev. E. 2016;93:022610. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.022610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kokot G., Das S., Winkler R.G., Gompper G., Aranson I.S., Snezhko A. Active turbulence in a gas of self-assembled spinners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:12870–12875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710188114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eisenstecken T., Ghavami A., Mair A., Gompper G., Winkler R.G. Conformational and dynamical properties of semiflexible polymers in the presence of active noise. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017;1871:050001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laskar A., Singh R., Ghose S., Jayaraman G., Kumar P.B.S., Adhikari R. Hydrodynamic instabilities provide a generic route to spontaneous biomimetic oscillations in chemomechanically active filaments. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1964. doi: 10.1038/srep01964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandebroek H., Vanderzande C. Dynamics of a polymer in an active and viscoelastic bath. Phys. Rev. E. 2015;92:060601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanchez T., Chen D.T.N., DeCamp S.J., Heymann M., Dogic Z. Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature. 2012;491:431. doi: 10.1038/nature11591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaller V., Weber C., Frey E., Bausch A.R. Polar pattern formation: Hydrodynamic coupling of driven filaments. Soft Matter. 2011;7:3213–3218. doi: 10.1039/c0sm01063d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abkenar M., Marx K., Auth T., Gompper G. Collective behavior of penetrable self-propelled rods in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. E. 2013;88:062314. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.88.062314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Denk J., Huber L., Reithmann E., Frey E. Active Curved Polymers Form Vortex Patterns on Membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116:178301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.178301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peruani F. Active Brownian rods. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2016;225:2301–2317. doi: 10.1140/epjst/e2016-60062-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Needleman D., Dogic Z. Active matter at the interface between materials science and cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:201748. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prathyusha K.R., Henkes S., Sknepnek R. Dynamically generated patterns in dense suspensions of active filaments. Phys. Rev. E. 2018;97:022606. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.97.022606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brangwynne C.P., Koenderink G.H., MacKintosh F.C., Weitz D.A. Nonequilibrium Microtubule Fluctuations in a Model Cytoskeleton. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:118104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.118104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weber C.A., Suzuki R., Schaller V., Aranson I.S., Bausch A.R., Frey E. Random bursts determine dynamics of active filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10703–10707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421322112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber S.C., Spakowitz A.J., Theriot J.A. Nonthermal ATP-dependent fluctuations contribute to the in vivo motion of chromosomal loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7338–7343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119505109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Javer A., Long Z., Nugent E., Grisi M., Siriwatwetchakul K., Dorfman K.D., Cicuta P., Cosentino Lagomarsino M. Short-time movement of E. coli chromosomal loci depends on coordinate and subcellular localization. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:3003. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zidovska A., Weitz D.A., Mitchison T.J. Micron-scale coherence in interphase chromatin dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220313110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Winkler R.G., Wysocki A., Gompper G. Virial pressure in systems of spherical active Brownian particles. Soft Matter. 2015;11:6680–6691. doi: 10.1039/C5SM01412C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Das S., Gompper G., Winkler R.G. Confined active Brownian particles: Theoretical description of propulsion-induced accumulation. New J. Phys. 2018;20:015001. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/aa9d4b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barry M.T., Rusconi R., Guasto J.S., Stocker R. Shear-induced orientational dynamics and spatial heterogeneity in suspensions of motile phytoplankton. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2015;12:20150791. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Winkler R.G., Reineker P., Harnau L. Models and equilibrium properties of stiff molecular chains. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;101:8119–8129. doi: 10.1063/1.468239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harnau L., Winkler R.G., Reineker P. Dynamic properties of molecular chains with variable stiffness. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;102:7750–7757. doi: 10.1063/1.469027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harnau L., Winkler R.G., Reineker P. Dynamic Structure Factor of Semiflexible Macromolecules in Dilute Solution. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;104:6355–6368. doi: 10.1063/1.471297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bawendi M.G., Freed K.F. A Wiener integral model for stiff polymer chains. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;83:2491–2496. doi: 10.1063/1.449296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Battacharjee S.M., Muthukumar M. Statistical mechanics of solutions of semiflexible chains: A path integral formulation. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;86:411–418. doi: 10.1063/1.452579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ha B.Y., Thirumalai D. A mean-field model for semiflexible chains. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:9408–9412. doi: 10.1063/1.470001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winkler R.G., Reineker P. Finite Size Distribution and Partition Functions of Gaussian Chains: Maximum Entropy Approach. Macromolecules. 1992;25:6891–6896. doi: 10.1021/ma00051a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Winkler R.G. Deformation of Semiflexible Chains. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:2919–2928. doi: 10.1063/1.1537247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fodor É., Nardini C., Cates M.E., Tailleur J., Visco P., van Wijland F. How Far from Equilibrium Is Active Matter? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:038103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.038103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fily Y., Marchetti M.C. Athermal Phase Separation of Self-Propelled Particles with No Alignment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:235702. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.235702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bialké J., Speck T., Löwen H. Crystallization in a Dense Suspension of Self-Propelled Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:168301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.168301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaiser A., Babel S., ten Hagen B., von Ferber C., Löwen H. How does a flexible chain of active particles swell? J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:124905. doi: 10.1063/1.4916134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doi M., Edwards S.F. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Winkler R.G. Conformational and rheological properties of semiflexible polymers in shear flow. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;133:164905. doi: 10.1063/1.3497642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang C.C., Winkler R.G., Sutmann G., Gompper G. Semidilute polymer solutions at equilibrium and under shear flow. Macromolecules. 2010;43:10107. doi: 10.1021/ma101836x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bird R.B., Armstrong R.C., Hassager O. Dynamics of Polymer Liquids. Volume 1 John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY, USA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schroeder C.M., Teixeira R.E., Shaqfeh E.S.G., Chu S. Dynamics of DNA in the flow-gradient plane of steady shear flow: Observations and simulations. Macromolecules. 2005;38:1967–1978. doi: 10.1021/ma0480796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lyulin A.V., Adolf D.B., Davies G.R. Brownian dynamics simulations of linear polymers under shear flow. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;111:758–771. doi: 10.1063/1.479355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jendrejack R.M., de Pablo J.J., Graham M.D. Stochastic simulations of DNA in flow: Dynamics and the effects of hydrodynamic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:7752–7759. doi: 10.1063/1.1466831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu S., Ashok B., Muthukumar M. Brownian dynamics simulations of bead-rod-chain in simple shear flow and elongational flow. Polymer. 2004;45:1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2003.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aust C., Kröger M., Hess S. Structure and dynamics of dilute polymer solutions under shear flow via nonequilibrium molecular dynamics. Macromolecules. 1999;32:5660–5672. doi: 10.1021/ma981683u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eslami H., Müller-Plathe F. Viscosity of Nanoconfined Polyamide-6,6 Oligomers: Atomistic Reverse Nonequilibrium Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:387–395. doi: 10.1021/jp908659w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Singh S.P., Chatterji A., Gompper G., Winkler R.G. Dynamical and rheological properties of ultrasoft colloids under shear flow. Macromolecules. 2013;46:8026–8036. doi: 10.1021/ma401571k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]