Abstract

Disinhibited attachment behavior is related to early institutional rearing and to later social maladaptation. It is also seen among infants reared at home whose mothers have histories of child maltreatment or psychiatric hospitalization. However, little is known about the maternal psychiatric diagnoses that might be associated with disinhibited behavior or the mechanisms through which maternal diagnosis might influence infant behavior. In the current study (N = 59), 2 maternal diagnoses, borderline personality disorder (BPD; n = 13) and depression (n = 15), were compared with a no diagnosis group (n = 31) on extent of infant disinhibited behavior. Disinhibited infant behavior was assessed at infant age of 12–18 months using the validated Rating of Infant–Stranger Engagement. Mother–infant interaction was coded using the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification. Results indicated that infants of mothers with BPD were significantly more likely to be rated as disinhibited in their behavior toward the stranger compared with infants of mothers with depression and with no diagnosis. Disinhibited behavior was further related to the quality of mother–infant interaction, and maternal frightened/disoriented interaction partially mediated the effect of maternal BPD on infant disinhibited behavior. Disinhibited behavior among previously institutionally reared infants is relatively resistant to intervention after toddlerhood and is associated with maladaptation into adolescence. Therefore, high priority should be placed on understanding the developmental trajectories of home-reared infants with disinhibited behavior and on providing early assessment and early parenting support to mothers with BPD.

Keywords: attachment disorders, disinhibited social engagement disorder, borderline personality disorder, maternal depression, disrupted maternal behavior

Disinhibited attachment behavior among young children has been of great interest to clinicians and researchers (Rutter et al., 2010; Zeanah & Gleason, 2015). Both the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (World Health Organization, 1996) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) now include criteria for a “disinhibited attachment” (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) or “disinhibited social engagement” (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) disorder among young children who have experienced pathogenic care. Disinhibited attachment has been operationalized as a lack of normative reticence with strangers, limited differentiation among adults, a lack of checking back with the parent in unfamiliar situations, and the willingness of some young children to make physical contact with and/or go off with strangers (Rutter et al., 2010; Zeanah, Smyke, & Dumitrescu, 2002).

Although most research on disinhibited attachment behavior has concentrated on children who have experienced institutional care, other studies have shown that disinhibited attachment behavior also occurs among infants being cared for by their families of origin. Boris et al. (2004) compared maltreated children and children living with their mothers in homeless shelters with children recruited from Head Start classes. Compared with children from Head Start classes, maltreated children and children living in shelters were significantly more likely to exhibit disinhibited behavior, as assessed by caregiver report. Zeanah et al. (2004), also using caregiver report, found similar results among maltreated children in foster care compared with controls, particularly those children whose mothers had psychiatric histories. Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Riley, and Atlas-Corbett (2009), using direct observation of infant–stranger interaction, similarly found that disinhibited behavior was elevated among infants whose mothers had more severe psychosocial risk factors, including a history of psychiatric hospitalization or child maltreatment. In addition, maternal disoriented interaction with the infant was strongly associated with disinhibited behavior, whereas other aspects of interaction, including negative/intrusive interaction, were not associated with disinhibited behavior. It was also notable that the presence of disorganized attachment to the mother did not account for the infant’s disinhibited behavior toward the stranger.

These disinhibited behaviors are of concern because both randomized intervention data and longitudinal follow-up data of institutionally reared children underscore both the persistence and the subsequent impairment associated with such behaviors. Among children adopted out of institutions into advantaged homes and infants randomly assigned out of institutions into good foster care by 24 months of age, disinhibited behavior continued to be exhibited into adolescence (Humphreys, Nelson, Fox, & Zeanah, 2017; Rutter et al., 2010). Thus, subsequent improvement in care does not substantially ameliorate the behavior.

In addition, these persistent aberrant behaviors are associated with a variety of other impairments or maladaptive behaviors. Consistent with the clinically observed tendency to approach strangers, disinhibited behaviors among adopted institutionally reared children are associated with increased laboratory-assessed non-normative physical overtures, but not social overtures, toward strangers between 25 and 40 months of age (Lawler, Hostinar, Mliner, & Gunnar, 2014), as well as reduced adoptive mother–stranger discrimination in the amygdala on functional magnetic resonance imaging between 4 and 17 years of age (Olsavsky et al., 2013). In addition, disinhibited behavior is associated with hyperactivity by preschool age (Gleason et al., 2011; Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009; O’Connor, Rutter, & The English & Romanian Adoptees Study Team, 2000; Rutter et al., 2007), which tends to persist through age 15 (Rutter et al., 2010). It is also associated with quasiautistic features (poor eye contact, stereotyped interests, and difficulties in empathy) observed throughout follow-up to age 15 (Rutter et al., 2010), with later superficial peer relationships in middle childhood and adolescence (Gleason et al., 2011; Hodges & Tizard, 1989; Rutter et al., 2007), with continued difficulties in picking up social cues and appreciating social boundaries at age 15 (Rutter et al., 2010), and with more social service use during childhood and adolescence (Rutter et al., 2010). Finally, cognitive correlates have also been observed, with disinhibited behavior associated with diminished electroencephalography alpha power at 18 months of age (Tarullo, Garvin, & Gunnar, 2011) and with poorer inhibitory control among preschoolers (Bruce, Tarullo, & Gunnar, 2009; Gleason et al., 2011; Pears, Bruce, Fisher, & Kim, 2010). Thus, understanding the caregiving contexts that give rise to disinhibited behavior is an important priority for efforts at both primary and secondary prevention of this range of associated deficits.

Although the consequences of institutional care are of great concern, a much greater number of young children worldwide are being raised at home exposed to maltreatment or parental psychiatric disorder. Owing to the very few studies of disinhibited behavior among home-reared infants, it remains unclear whether the contexts and correlates associated with disinhibited behavior among institutionalized children should be generalized to young children reared at home. Thus, in this report, we use the term disinhibited attachment behavior throughout, rather than the diagnostic term disinhibited social engagement disorder, because it remains unclear whether a similar early behavioral pattern among home-reared infants should be viewed as a disorder. The current study aims to extend the literature on the contexts associated with disinhibited behavior among home-reared infants.

In the previous studies of disinhibited behavior among homereared infants, psychiatric status was a binary variable, labeled simply psychiatric hospitalization history or psychiatric disturbance without further specification (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009; Zeanah et al., 2004). Thus, we have little understanding of the specific types of maternal psychiatric disturbances that may increase the incidence of disinhibited behavior. In addition, there has been little exploration of the aspects of maternal behavior that might mediate any effect of maternal diagnosis on infant disinhibited behavior.

In the work cited earlier (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009), frightened/ disoriented maternal behavior was specifically associated with disinhibited behavior, whereas other forms of disrupted interaction were not, suggesting some specificity to the pattern of caregiving behavior associated with infant disinhibited behavior. In a separate study of mothers with borderline personality disorder (BPD), mothers with BPD were more likely to show frightened/disoriented behavior with their infants than mothers with depression or no diagnosis (Hobson et al., 2009). Taken together, these results point to maternal frightened/disoriented behavior as a potentially important correlate of infant disinhibited behavior and also suggest that BPD might be a salient diagnosis to investigate in relation to infant disinhibited behavior.

BPD is characterized by a cluster of features including intense and unstable relationships, lability of affect, impulsive selfdamaging behaviors, suicidality, and identity disturbances (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 1996). By retrospective self-report, individuals with BPD have also experienced deviant care in their own childhood relationships, including a high incidence of neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and role confusion with parents (Zanarini et al., 1997). Finally, violations of social boundaries have been noted to be more frequent in therapeutic interactions with patients with BPD, which further suggests a relation to disinhibited attachment behaviors also characterized by violations of normative social boundaries (Gutheil, 1989; Simon, 1992).

Based on this existing literature, we first hypothesized that infants of mothers with BPD would display higher levels of disinhibited attachment behavior than either control group. Sec-ond, given the lack of association between maternal depression and disoriented interaction (Hobson et al., 2009), we hypothesized that infants of depressed mothers would not show elevations in disinhibited behavior in comparison with no diagnosis controls. Third, we theorized that frightened/disoriented maternal behaviors in interaction with the infant would partially mediate the effect of maternal BPD on infant disinhibited behavior.

Method

Participants

Fifty-nine mothers and infants participated in the study. Given the difficulties in recruiting samples of mothers who both have a relatively rare diagnosis and a child under 2, we followed prior precedent (Hobson et al., 2009) and combined participants from two cohorts of mothers and infants for whom BPD diagnoses, depressive diagnoses, and measures of infant and parent behavior were available. The first cohort (for full details, see Hobson, Patrick, Crandell, García-Pérez, & Lee, 2005) comprised 10 mothers with BPD and a control group of 22 mothers who had no clinical features of BPD or other history of psychiatric disorder and who were similar in age, ethnicity, social class, marital status, and education to mothers in the BPD group.

The second cohort of mothers and infants consisted of three mothers with BPD, 15 mothers with depressive disorders, and nine mothers with no diagnosis. These 27 participants included all mothers who fit the abovementioned three diagnostic categories among a larger group of 65 participants in a longitudinal study of attachment among families who were at or below poverty level (for full details, see Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Grunebaum, & Botein, 1990). Table 1 gives demographic characteristics of mothers and infants in the three diagnostic groups. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Cambridge Health Alliance and the Tavistock Clinic. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Table 1:

Demographic Details of Diagnostic Groups by Cohorts

| Borderline personality disorder |

Depression |

No diagnosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | Cohort1 (n = 10) | Cohort 2 (n = 3) | Cohort 2 (n = 15) | Cohort 1 (n = 22) | Cohort 2 (n = 9) |

| Maternal age, yr: M (SD) | 32 (7.5) | 30 (3.2) | 28 (6.8) | 33 (4.6) | 26 (4.2) |

| Caucasian ethnicity, % (n) | 60 (6.0) | 100 (3.0) | 73 (11.0) | 73 (16.0) | 90 (8.0) |

| Social class I–II, % (n) | 60 (6.0) | 0 (.0) | 13 (2.0) | 73 (16.0) | 33 (3.0) |

| Married/cohabiting, % (n) | 60 (6.0) | 67 (2.0) | 67 (10.0) | 73 (16.0) | 67 (6.0) |

| Infant male, % (n) | 50 (5.0) | 67 (2.0) | 47 (7.0) | 50 (11.0) | 78 (7.0) |

| Infant age, weeks: M (SD) | 53 (2.8) | 77 (2.5) | 80 (4.0) | 55 (1.8) | 79 (2.0) |

Note. Cohort 1 is the Hobson et al. (2009) cohort; Cohort 2 consists of participants from the larger Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Riley, and Atlas-Corbett (2009) cohort.

Measures

Diagnostic assessment.

For participants from the Hobson cohort, mothers were given the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) focusing on personality disorders (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) supplemented with the interview version of the SCID overview and “module A” focusing on mood syndromes and “module B/C” (the “psychotic screen”). Only those women meeting the diagnostic criteria for BPD and no other diagnostic categories were included in the borderline group. Mothers were accepted into the control group if they showed no features of BPD and did not meet diagnostic criteria for any other Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), either current or past (complete details in Hobson et al., 2005).

For participants from the Lyons-Ruth cohort, mothers were assigned diagnoses for lifetime Axis I disorders using the semistructured Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins, Helzer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, 1981) when the infants were 12–18 months of age. Fifteen mothers met criteria for a depressive diagnosis (with or without an associated anxiety disorder). A diagnostic screen for Axis II was not available at the time of the infant study. However, when the infants were in late adolescence (20 years of age), mothers were administered the SCID-II. Three mothers met criteria for BPD on the SCID-II and were assigned to the BPD group. Nine mothers did not meet criteria for an Axis I diagnosis on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule during the child’s infancy and did not meet criteria for an Axis II disorder on the SCID-II when the child was aged 20 years, so they were assigned to the no diagnosis group. Given the delay in the assessment of BPD in this cohort, it is possible that there were mothers in the depressed group or the no diagnosis group who might have met criteria for BPD when their children were infants but not at the 20-year follow-up. However, this would introduce a conservative bias against finding the predicted group differences.

Rating of Infant–Stranger Engagement.

Rutter et al. (2010) point to the core features of disinhibited attachment behavior as,

inappropriate approach to unfamiliar adults, a lack of wariness of strangers, a failure to check back with a caregiver in unfamiliar settings, and a willingness to accompany a stranger…away from the caregiver…. In addition, there is sometimes inappropriate affectionate behavior with strangers and undue physical closeness. (p. 58; see also Lawler et al., 2014; Zeanah & Gleason, 2015)

Others have noted the lack of differentiation (absence of expected selectivity) in attachment behaviors being expressed toward the caregiver and the stranger (Chisholm, Carter, Ames, & Morison, 1995). The Rating of Infant–Stranger Engagement (RISE) coding system was developed to capture such forms of engagement with the stranger from 12 to 18 months (Riley, Atlas-Corbett, & Lyons-Ruth, 2005).

The Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978) provides one useful setting for observing selectivity in attachment behavior and the degree of non-normative physical closeness with the stranger exhibited by the infant. In this procedure, the infant is videotaped in a playroom during a series of eight structured 3-min episodes involving the baby, the mother, and a female stranger, for a total of 24 min of observation. During the observation, the mother leaves and rejoins the infant twice, first leaving the infant with the female stranger for 3 min, then leaving the infant alone for 3 min, to be rejoined by the stranger for another 3 min, before the mother enters again. Thus, the infant spends two 3-min episodes alone with the mother and two 3-min episodes alone with the stranger. The procedure is designed to be mildly stressful to increase the intensity of activation of the infant’s attachment behavior toward the mother.

On the RISE, each infant is assigned a rating of 1–9, evaluating the extent of the infant’s affective engagement with the stranger compared with the mother and the extent to which the infant displays non-normative acceptance of physical contact and comforting by the stranger, over the 24-min SSP. A score of 5 indicates equal affective engagement with the stranger and mother. Higher scores indicate greater engagement with the stranger than mother, such as brighter affect with the stranger, maintains proximity to the stranger, calms more quickly with the stranger, seeks more physical contact with the stranger. At the highest levels, the infant shows striking indicators of attachment behavior toward the stranger, such as calming quickly when distressed, cuddling into the stranger, and making sustained physical contact. Definitions for all scale points are available in the article by Lyons-Ruth et al. (2009).

RISE coding reliabilities for the two cohorts were as follows: Lyons-Ruth et al. (2009) cohort, ri = .72 (n = 41), and Hobson et al. (2005) cohort, ri = .71 (n = 12). Coders were naïve to all other data from the study, as well as the nature of the study itself. Construct validity of the RISE has been shown in relation to caregiver report on the Disorders of Attachment Interview (Oliveira et al., 2012), more severe caregiving deviations (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009), and prediction of later hyperactive behavior (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009). The RISE also shows discriminant validity in relation to infant age, gender, socioeconomic status, and cognitive scores (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009; Oliveira et al., 2012).

Disrupted maternal affective communication.

Maternal interactive behavior over the course of the SSP was rated from the videotape using the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification (AMBIANCE; Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Parsons, 1999). Using extensive itemized examples in the coding manual, the coder tallies the frequency of the following five forms of disrupted maternal communication: (a) affective communication errors, defined as contradictory affective signals to the infant (e.g., using a sweet voice with a derogatory message) or inadequate or inappropriate responses to the infant’s signals (e.g., fails to comfort a distressed infant); (b) role confusion, coded when the mother calls the infant’s attention to herself in ways that override or ignore the infant’s cues (e.g., asking the infant for a kiss when the infant is distressed); (c) frightened/disoriented behavior, shown in fearful, hesitant, or deferential behavior toward the infant (e.g., hesitating before responding to the infant or tense body postures) or as expressed in disoriented behavior (e.g., flat or odd affect in interaction or frenetic or uncoordinated overtures toward the infant); (d) negative/intrusive behavior, defined as harsh or critical behavior (e.g., pulling the infant by the wrist, mocking or teasing the infant, or attributing negative affect to the infant); and (e) withdrawing behavior, as shown by creating physical or emotional distance from the infant (e.g., standing across the room while interacting or interacting silently). Based on the frequency and seriousness of the observed forms of disrupted communication, overall level of disrupted communication is rated (1–7). Parents rated at 5 or above are classified as disrupted in interaction with the infant. Reliabilities (n = 15) were strong on all scales: affective communication errors, ri = .75; role confusion, ri = .76; negative/intrusive behavior, ri = .84; frightened/disoriented behavior, ri = .73; and withdrawal, ri = .73. Coders were naïve to all other data from the study, as well as to the nature of the study itself.

Meta-analysis has shown the AMBIANCE to have concurrent and predictive validity in relation to infant disorganization (r = .35, N = 384) and stability for periods up to 5 years (stability coefficient = .56, N = 203; Madigan et al., 2006). AMBIANCE assessed in infancy also shows predictive validity in relation to disturbed interactions in middle childhood (Easterbrooks, Bureau, & Lyons-Ruth, 2012) and to BPD features, suicidality, dissociation, and antisocial personality disorder in young adulthood (Dutra, Bureau, Holmes, Lyubchik, & Lyons-Ruth, 2009; Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Holmes, Easterbrooks, & Brooks, 2013; Shi, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Zhao, & Lyons-Ruth 2012).

Analytic Plan

The first hypothesis that infants of mothers with BPD would be at greater risk for disinhibited behavior was tested by a general linear model analysis of variance (ANOVA) on overall level of infant disinhibited behavior, using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 24.0). Maternal diagnostic grouping was the independent variable, and planned orthogonal contrasts tested whether each control group (no diagnosis group or depressed group) differed from the BPD group. This hypothesis was further explored by a follow-up logistic regression analysis on the dichotomous classification as disinhibited. The second hypothesis, that maternal depression would not be associated with an elevation in infant disinhibited behavior compared with the no diagnosis group, was also assessed by general linear model ANOVA on the continuous variable and by logistic regression on the dichotomous classification. The third hypothesis, that maternal disoriented behavior would mediate the effect of maternal BPD on disinhibited behavior, was assessed using linear regression models with bootstrapped confidence intervals (Hayes, 2013). Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS Version 24 was used to estimate the total, direct, and indirect effects of predictor variables on outcomes through the proposed mediators.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Variables were first examined for normality. Maternal communication variables were positively skewed and were transformed using a square root transformation, which succeeded in normalizing the distributions. However, results were similar with or without the transformations.

None of the demographic characteristics in Table 1 were significantly related to disinhibited behavior, with or without controlling for diagnostic group, so these variables were not analyzed further: mother’s age, F(1, 57) = 1.21, p = .28, η2 = .02, age controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 0.85, p = .36, η2 = .02, mother’s ethnicity, F(1, 57) = 0.03, p = .87, η2 = .00, ethnicity controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 0.00, p = .95, η2 = .00, social class, F(1, 57) = 0.07, p = .79, η2 = .00, social class controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 0.10, p = .75, η2 = .00, partner status, F(1, 57) = 0.94, p = .34, η2 = .02, partner status controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 0.64, p = .43, η2 = .01, infant sex, F(1, 57) = 2.73, p = .10, η2 = .05, sex controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 3.39, p = .07, η2 = .06, infant age, F(1, 57) = 3.39, p = .07, η2 = .06, and age controlled for diagnostic group, F(1, 55) = 1.47, p = .23, η2 = .03). In addition, inclusion of any of the demographic variables did not alter the robust association between diagnostic grouping and disinhibited behavior (all ps > .01), as reported next.

Maternal BPD, Maternal Depression, and Infant Disinhibited Behavior

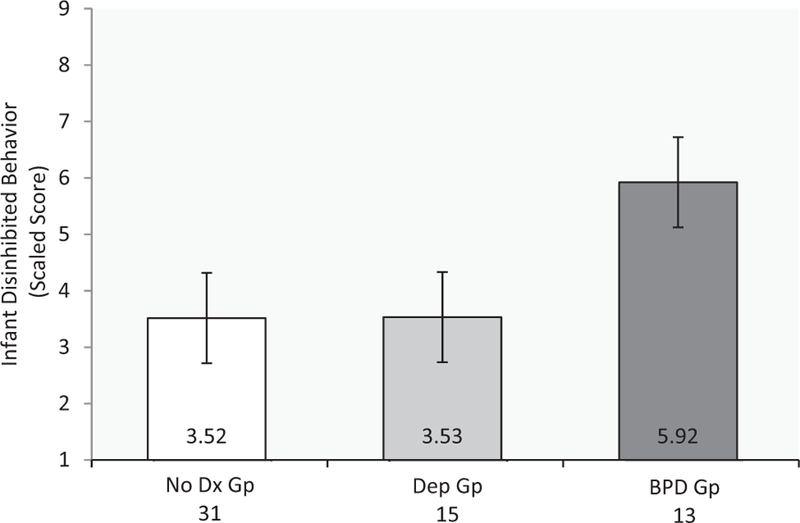

In relation to the first hypothesis, general linear model ANOVA on levels of disinhibited behavior revealed that infants in the BPD group exhibited significantly elevated levels of disinhibited behavior compared with both no diagnosis controls and depressed controls (planned orthogonal comparisons: BPD vs. no diagnosis: estimate = −2.407, p = .001; BPD vs. depressed: estimate = −2.390, p = .004; see Figure 1). The number of infants over the classification point for disinhibited behavior was also assessed by diagnostic group in a logistic regression analysis. Analysis of the classifications yielded similar differences among groups: overall χ2(2, 56) = 10.79, p = .005, R2 = .22, R = .46; BPD vs. no diagnosis Wald = 7.25, p = .007, BPD vs. depression diagnosis Wald = 6.45, p = .01. Thus, infants of mothers with BPD were more likely than infants of mothers with depression, as well as with no diagnosis, to exhibit disinhibited attachment behavior to the stranger. Among mothers with a BPD diagnosis, 84.6% of infants showed equal or greater engagement with the stranger than with the mother and were classified as disinhibited, whereas among those with no diagnosis, only 35.5% were so classified.

Figure 1.

Mean levels of disinhibited behavior by maternal diagnostic group. Bars indicate standard error.

In relation to the second hypothesis, the rate of disinhibited behavior among infants of depressed mothers (33%) was similar to that of infants of mothers with no diagnosis (35.5%). In addition, means for the two groups did not differ, estimate = .017, ns (means shown in Figure 1). The odds ratios (ORs) indicated that infants of mothers with BPD had a 10-fold relative risk for disinhibited behavior compared with the no diagnosis group (OR = 10.00), whereas infants of depressed mothers had no elevated risk compared with the no diagnosis group (OR = .90).1

Maternal Disrupted Communication and Infant Disinhibited Behavior

To assess the third hypothesis regarding which maternal behaviors might mediate the relation between maternal BPD and infant disinhibited behavior, correlations were first computed between infant disinhibited behavior and the five dimensions of maternal disrupted communication. These analyses revealed that maternal frightened/disoriented behavior was the dimension most highly correlated with infant disinhibited behavior, r = .51, p < .001. Two other aspects of maternal disrupted communication were also significantly associated, namely, maternal role confusion, r = .32, p = .05, and maternal negative/intrusive behavior, r = .36, p = .01.

Because the robust relation of frightened/disoriented behavior to disinhibited behavior was similar to previous results using the entire cohort of the Lyons-Ruth et al. (2009) study, it seemed possible that the inclusion of a subset of the Lyons-Ruth cohort in the current study might be driving these results. Therefore, we deleted all participants from the Lyons-Ruth cohort and repeated the analysis on only the 32 mothers and infants from the Hobson cohort. In the Hobson cohort alone, maternal frightened/disoriented communication remained robustly associated with infant disinhibited behavior, r = .38, p = .05, whereas no other dimension of maternal disrupted communication reached significance, rs = −.03 to .25, all ps = ns. Thus, the relation between infant disinhibited behavior and maternal frightened/disoriented behavior was not being driven by the inclusion of participants from the Lyons-Ruth cohort.2,3

Testing a Mediational Model

We then tested a mediational model in which maternal BPD was the independent variable, infant disinhibited behavior was the dependent variable, and the three dimensions of maternal disrupted interaction associated with disinhibited behavior were the proposed mediators. Those dimensions were frightened/disoriented behavior, role confusion, and negative/intrusive behavior. Because no differences had emerged between the no diagnosis and depressed groups in infant disinhibited behavior, those two groups were combined as one contrast group to the BPD group.

The results of the regression analyses again confirmed that maternal BPD versus the combined control groups had a significant total effect on infant disinhibited behavior (t = 3.65, p = .001, β = .44). Moreover, when the variance in disinhibited behavior accounted for by the three dimensions of disrupted com munication was removed, the effect of maternal BPD remained significant but dropped substantially (t = 2.10, p = .04, β = .26), which suggests mediation. Finally, when the three dimensions of maternal behavior were entered together into the regression equation, only frightened/disoriented behavior and role-confused behavior remained significantly related to disinhibited behavior. Negative/intrusive behavior did not account for additional unique variance, indicating that its contribution was explained by its overlap with the other two variables.

When bootstrapped confidence intervals were examined for each of the three maternal variables as a test of whether they should be considered mediators of the effect of diagnosis on disinhibited behavior, only maternal frightened/disoriented behavior was shown to be a significant mediator (i.e., the confidence interval did not contain zero, the accepted criterion for significant mediation; Table 2). Thus, maternal BPD had a significant indirect effect on infant disinhibited behavior through maternal frightened/ disoriented behavior (Table 2), whereas neither role confusion nor negative/intrusive behavior mediated the relation of diagnosis to infant disinhibited behavior (Table 2).

Table 2:

Indirect Effect of BPD on Infant Disinhibited Behavior Through the Mother’s Frightened/Disoriented Behavior in Interaction

| Bootstrapped |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||||

| Indirect effects evaluated | Effect (SE) | Lower | Upper | Mediation |

| Maternal frightened/disoriented | .76 (.39) | .19 | 1.79 | Yes |

| Maternal role-confused | .19 (.26) | −.21 | .92 | No |

| Maternal negative/intrusive | .04 (.21) | −.24 | .71 | No |

Note. 5,000 bootstrap samples. If the confidence intervals (CIs) do not contain zero, the null hypothesis of lack of mediation is rejected (Hayes, 2013). BPD = borderline personality disorder.

Notably, both maternal BPD and maternal frightened/disoriented behavior also made additional direct contributions to infant disinhibited behavior, with the other controlled (frightened/disoriented: Fchg = 8.38, , β = .36, p = .005; BPD vs. controls: Fchg = 5.53, , β = .29, p = .022). These residual direct effects indicate that maternal BPD acts on infant disinhibited behavior through pathways additional to maternal frightened/disoriented behavior and that maternal frightened/disoriented behavior also acts on infant disinhibited behavior through pathways additional to maternal BPD. That is, frightened/disoriented behavior also affects infants of mothers who do not have a diagnosis of BPD. Thus, the strongest predictive model for infant disinhibited behavior would include both diagnosis and maternal behavior, F(2,56) = 11.71, R2 = .30, β= .55, p = .000, compared with the earlier models that include only diagnosis or maternal behavior.

Discussion

Very few studies have examined contributors to infant disinhibited behavior outside the context of institutional rearing. However, the few existing studies clearly indicate that, across methods of assessment, disinhibited behavior occurs among home-reared infants and is associated with deviations in care (Boris et al., 2004; Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009; Zeanah et al., 2004). Given the small numbers of children reared in institutions relative to the much larger numbers reared in maltreating or disturbed households, increased understanding of the determinants of disinhibited behavior among home-reared infants is a pressing social policy issue in developmental psychopathology.

Previous studies of disinhibited behavior among home-reared infants have looked only at general indices of caregiver disturbance, such as maltreatment or psychiatric hospitalization. In the current study, we extended the study of infant disinhibited behavior to include mothers with specific psychiatric diagnoses, including BPD and depressive disorders. The first finding of the study was that infant disinhibited behavior was strongly associated with maternal BPD but was not associated with maternal depression. Specifically, a majority of infants of mothers with BPD showed as much preference and relatedness to the stranger as to the mother, with a sizable percentage accepting comfort and close physical contact with the stranger. A very large body of normative data on the SSP leads to the strong expectation that the primary caregiver will be the preferred target of the infant’s attachment behavior, including eye contact, positive affect, and play behavior when not distressed, as well as proximity- and contact-seeking when distressed. The absence of such well-documented selective behavior toward the caregiver, and the presence of non-normative physical contact-seeking toward the stranger, is cause for concern.

The second major finding was that infants of mothers in the depressed group did not show elevations in disinhibited behavior. In previous work, we also found that depressed mothers did not show elevated levels of frightened/disoriented behavior compared with no diagnosis controls (Hobson et al., 2009). Thus, as further suggested by the mediation results discussed next, this lower level of frightened/disoriented behavior among depressed mothers is likely to have contributed to their infants’ lower rates of disinhibited behavior.

The third major finding was that the caregiver’s frightened/ disoriented behavior was associated with higher levels of infant disinhibited behavior and, further, frightened/disoriented behavior partially mediated the relation between maternal BPD diagnosis and infant disinhibited behavior. This association was first reported in the Lyons-Ruth et al. (2009) cohort and was replicated independently here in the Hobson cohort, a sample with very different characteristics. The Lyons-Ruth cohort was predominately low income, with few mothers diagnosed with BPD but others having histories of psychiatric hospitalization or child maltreatment. In contrast, the Hobson cohort was predominately middle to upper class, with a sizable group of mothers with BPD but no other diagnoses.

Thus, the mediation analysis confirmed that maternal frightened/ disoriented behavior was one specific pathway through which the mother’s BPD increased the infant’s disinhibited behavior. Notably, other possible forms of disturbed maternal interaction, including hostile/intrusive, role-confused, or withdrawing behavior, did not mediate the effect of BPD on infant disinhibited behavior, though they have been related to other maladaptive child outcomes (Dutra et al., 2009; Lyons-Ruth et al., 2013; Lyons-Ruth, Easterbrooks, & Cibelli, 1997), as well as to maternal BPD (Eyden, Winsper, Wolke, Broome, & MacCallum, 2016; Hobson et al., 2005; Stepp, Whalen, Pilkonis, Hipwell, & Levine, 2012). Mothers high in frightened/disoriented communication made attempts to approach and engage their infants but appeared hesitant and awkward, with tense body postures or unusual shifts in voice tone or odd, affectless behavior. They had trouble sustaining communication and often set up a circle of toys around the infant and then withdrew. There was the sense that they did not know their infants well and were not confident in how to interact with them. Thus, the interactions were marked by odd affect, stilted interaction with the infant, and affective distancing.

We theorize that it is the particular disturbance in affective engagement reflected in maternal frightened/disoriented behavior that is one critical element that leads the infant to turn to the stranger for affective relatedness. Others have noted that caregivers working in rotating shifts in residential institutions exhibit a profound lack of affective engagement with the infant, which, in turn, may contribute to the increased rates of disinhibited behavior among institutionally reared children (St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). This accords with evidence that decreasing the number of caregivers per infant and increasing the affective responsiveness and relatedness of institutional caregivers during the first 18 months of life leads to more contact- and proximity-seeking by the infants, as well as to more organized attachment patterns (St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). However, there may be other aspects of care both by mothers with BPD and by caregivers in institutions that contribute to the infants’ disinhibited behavior, so the particulars of care in both settings need further study.

It is not clear why other deviations in maternal interaction are not similarly associated with infant disinhibited attachment behavior. However, one possibility that needs further exploration is that the other forms of maternal disrupted interaction assessed here involve more direct affective relatedness, even if the affect is hostile (negative/intrusiveness) or contradictory (affective communication errors) or draws the infant’s attention to the mother’s needs (role confusion). Even in the case of maternal withdrawal, the mother’s affect is often somewhat flat, but it is not distorted, frightened, or disoriented.

Because mothers with BPD may show more than one type of disturbance in parenting, as shown here and in other work (Eyden et al., 2016; Stepp et al., 2012), the mediation analysis is important in indicating that although mothers in this study also showed several correlated indicators of disrupted parenting, it was the particular indicator of frightened/disoriented behavior that linked BPD to disinhibited behavior in the infant. One challenge for future work will be to link particular aspects of parenting, at particular ages, to particular outcomes for children. For example, hostile parenting has been repeatedly linked to the child’s own later hostile interaction and conduct disorder (Shaw, Owens, Vondra, Keenan, & Winslow, 1996). Thus, children of mothers with BPD may be at risk for a variety of later forms of maladaptation, in addition to disinhibited attachment behavior, if mothers are exhibiting a range of parenting difficulties over time.

There is emerging interest in neurobehavioral disinhibition as a contributor to disinhibited behavior (Pears et al., 2010; Zeanah & Gleason, 2015), and prenatal drug exposure has been related to increased disinhibition (Fisher et al., 2011). Thus, it is important to note that the majority of mothers with BPD were from the Hobson cohort and had no other psychiatric diagnoses, including substance dependence. Therefore, it is unlikely that maternal substance abuse was an influential contributor to the findings (see also Rutter et al., 2010).

Although the disinhibited behaviors of infants in disturbed home care fit to the disinhibited phenotype (Zeanah et al., 2004), we have no certainty that the behaviors seen among home-reared infants indeed constitute similar forms of maladaptation to those seen among institutionally reared infants. The experience of being reared in institutional care is a very different experience from being reared by a maltreating parent or a parent with a severe psychiatric disorder, and we would expect these differences to lead to different outcomes in later developmental periods. Evaluating the seriousness of the behaviors observed here will depend on further evidence regarding whether the contextual determinants, trajectories, associated psychopathologies, and genetic or temperamental contributors are also similar. Such work is needed to evaluate whether the level of impairment over time among homereared infants warrants the application of a psychiatric diagnosis. To date, we have little data to tie these deviations in behavior during infancy to the forms of disinhibited social behavior assessed in cross-sectional studies among maltreated children at later ages (Kay & Green, 2013; Minnis et al., 2013).

As noted by Rutter et al. (2010), the need for improved measurement of disinhibited attachment behavior from infancy to adolescence is an important research need. Although caregiver reports were first relied on for diagnosis, more recent investigators have developed observational methods of assessment for both infants and older children (Gleason et al., 2014; Kay & Green, 2013; Lawler et al., 2014; Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009: Rutter et al., 2010; Scheper et al., 2016). Because these observational assessments are relatively new and are targeted for particular ages from infancy to adolescence, we do not yet have a clear picture of how these observational assessments cohere across development, though all show concurrent convergence with caregiver report. Therefore, validation of observational methods that can be used with both home-reared and institutionally reared infants across ages remains a priority of research in this area.

The current study, although the only one of its kind, has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Given the small number of women at any given time who have both a BPD diagnosis and an infant under 2, the BPD sample is small, so the need for replication in larger samples of mothers with BPD is clear. In addition, mothers in the Hobson cohort were screened for comorbid diagnoses. This has the advantage of ruling out other comorbidities as accounting for the results but also means that the results need to be replicated among the large group of mothers with both BPD and other comorbid disorders. Moreover, only the diagnoses of BPD and depression were assessed here, so we do not know what other maternal psychiatric diagnoses might be associated with disinhibited behavior in the infant. Clearly, future studies in other diagnostic groups are needed. Finally, mothers in the Lyons-Ruth cohort, but not the Hobson cohort, were assessed for personality disorders long after infancy (when the child was 20 years old). This means that some mothers might have met criteria for BPD when the child was an infant but were not meeting criteria when the child was 20, and so were mistakenly assigned to the no diagnosis or depressed groups. However, in the case that some BPD mothers were mistakenly assigned to the no diagnosis or depressed groups, this form of error would be conservative in relation to our hypotheses. That is, it should increase the possibility of disinhibited infant behavior in the control groups and would work against our finding the robust group differences reported here.

Another limitation is that both mother and infant behaviors were assessed in the same situation, which may have increased the relation between them owing to shared method variance. However, shared variance does not fully account for the specificity of these results in that only one form of maternal behavior was associated with disinhibited behavior. In addition, this specific association between disoriented behavior and disinhibited behavior has now been replicated in two very different cohorts. Finally, it should be noted that although the SSP was the common setting for the assessments, maternal frightened/disoriented behavior was assessed predominately during the reunion episodes, when the mother is present and the stranger is absent, whereas infant disinhibited behavior was assessed predominately during the separation episodes, when the mother is absent and the stranger is present, thus limiting simple dependencies between maternal frightened/ disoriented behavior and infant disinhibited behavior toward the stranger.

A countervailing strength of the SSP for observing infant behavior toward the stranger is that we have several decades of normative data on infant behavior in the SSP (Ainsworth et al., 1978; van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999). This body of work unequivocally indicates that normative infant behavior is characterized by avoidance or resistance to close physical contact with the stranger and by the display of more positive affect, proximity-seeking, contact-seeking, and calming of distress to the return of the mother than to the return of the stranger, over the age range from 12 to 18 months (Ainsworth et al., 1978). Thus, we are able to interpret the greater physical proximity- and contact-seeking observed here toward the stranger as clearly non-normative. However, more work also is needed assessing caregiving behavior outside the context of the SSP.

Finally, because two separate cohorts were being combined for analyses, we must consider whether study differences could have affected results. The Hobson cohort, which contained most mothers with BPD, as well as a number of no diagnosis controls, was of considerably higher social class than the Lyons-Ruth cohort. Therefore, we carefully analyzed potential effects of social class on our outcome data. Importantly, there was no relation between social class and disinhibited behavior. This was certainly in part owing to the matched no diagnosis controls included in the Hobson study, who were of similar higher social class.

In addition, the Hobson study was conducted in the United Kingdom and the Lyons-Ruth study in the United States. This allows for unexpected cultural differences to color the findings. To address this point, we also analyzed and reported findings from the Hobson cohort separately, which confirmed that the observed differences between mothers with BPD and no diagnosis controls were robust within social class and within the British cultural group.

Although the differences between the BPD group and no diagnosis controls were clearly robust within the British culture and higher social class, the depressed group was constituted only from the Lyons-Ruth low-income cohort, so we must consider particularly carefully whether the difference in social class of this group would have affected the pattern of findings. We assessed this possibility directly by examining social class by diagnostic group interactions on disinhibited behavior, but found no evidence that the lower rate of disinhibited behavior in the depressed group was driven by an interaction between social class and group. In addition, theoretically, we would expect that the lower social class of the depressed group (an additional risk factor) would, if anything, increase the rate of infant disinhibited behavior in that group, relative to both the no diagnosis and the BPD groups, which both contained a number of mothers of higher social class. This would be expected to work against both of the hypothesized findings related to the depressed group, namely, (a) no differences in disinhibited behavior in relation to the no diagnosis group and (b) significantly less disinhibited behavior in relation to the BPD group. Thus, the lower social class of the depressed mothers was conservative to the hypotheses advanced, and we found no evidence that social class was coloring results. All these safeguards notwithstanding, it will be important to replicate the findings regarding the lower rate of disinhibited behavior in the depressed group among homogeneously high- and low-income samples.

In conclusion, the current study adds to accumulating evidence that infants of mothers with BPD are at increased risk for early developmental problems. Thus, high priority should be placed on providing early assessment and parenting support to mothers with BPD. In addition, current research indicates that, among children who have experienced institutional rearing, early disinhibited behavior tends to persist and is predictive of maladaptive outcomes into adolescence, even when children are placed in good care by the third year of life (Humphreys et al., 2017; Rutter et al., 2010). As noted in the introduction, maladaptive outcomes include a range of deficits, including increased physical overtures toward strangers (Lawler et al., 2014), reduced adoptive mother–stranger discrimination in the amygdala (Olsavsky et al., 2013), poorer inhibitory control (Bruce et al., 2009; Gleason et al., 2011; Pears et al., 2010), increased hyperactivity (Gleason et al., 2011; Lyons-Ruth et al., 2009; O’Connor et al., 2000; Rutter et al., 2007, 2010), and quasiautistic features (poor eye contact, stereotyped interests, and difficulties in empathy; Rutter et al., 2010). In addition, peer relationships in middle childhood and adolescence are superficial, with continued difficulties picking up social cues and appreciating social boundaries (Rutter et al., 2010) and with more social service use during childhood and adolescence (Rutter et al., 2010). The appropriate negotiation of sexual boundaries in adolescence and adulthood has not been investigated in relation to disinhibited attachment but would be an important area for future work.

Given the very small proportion of infants worldwide who are reared in institutions, the prevalence of disinhibited behavior among home-reared infants in disturbed care is likely to constitute a much greater public health burden. However, relatively few studies have assessed such behaviors among home-reared infants with serious caregiving risks. The persistence of social maladaptation into early adolescence among adopted institutionally reared children with disinhibited behavior also raises serious concern for the long-term adaptation of the children of mothers with BPD who display early disinhibited behavior. Further study of the longitudinal trajectories of social adaptation among infants of mothers with BPD is greatly needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH062030 to Karlen Lyons-Ruth, by a Harvard College Research Award to Caitlin Riley, and by grants to R. Peter Hobson from the Winnicott Trust, the Hayward Foundation, the Baily Thomas Charitable Fund, and the United Kingdom National Health R&D Budget.

Footnotes

Exploratory analyses also assessed whether differences remained using higher cutoff points for disinhibited behavior. Because no differences had emerged between the no diagnosis and depressed groups, they were combined as one contrast group. With a cutoff point of 6, indicating more positive behavior toward stranger than mother, 53.8% of infants in the BPD group versus 23.9% of controls were classified disinhibited (Wald = 4.01, p = .05); with a cutoff point of 7, indicating physical attachment behavior toward stranger, 38.5% of infants in the BPD group versus 15.2% of controls were classified disinhibited (Wald = 3.15, p = .08). Thus, differences between the BPD group and controls persisted using higher cutoff scores for disinhibited behavior.

Using the Hobson cohort only, infants of mothers with BPD displayed significantly higher levels of disinhibited behavior toward the stranger, compared with no diagnosis controls, with a large effect size, F(1,30) = 13.91, η = .56, p = .001, BPD: M = 6.30 (SD = 1.34); no diagnosis: M = 3.64 (SD = 2.06).

As in the earlier Lyons-Ruth et al. (2009) study, in the Hobson cohort alone, disorganized attachment toward mother did not account for disinhibited behavior toward the stranger. With disinhibited behavior regressed simultaneously on both disorganized status and diagnostic grouping, only diagnostic grouping was significant, t = 2.74, p = .01, β = .47; disorganization status, t = 1.05, p = ns, β = .18. Means confirmed that levels of disinhibited behavior were similar within diagnostic group, regardless of concomitant disorganization, no diagnosis group: not disorganized = 3.31, disorganized = 4.50; BPD group: not disorganized = 6.50, disorganized = 6.25.

Contributor Information

Karlen Lyons-Ruth, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School.

Caitlin Riley, Department of Psychology, Harvard College.

Matthew P. H. Patrick, Department of Psychiatry, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

R. Peter Hobson, Department of Psychiatry, Tavistock Clinic and Institute of Child Health, University College London..

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MS, Waters E, & Wall S (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (DSM–III–R) Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM–5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Hinshaw-Fuselier SS, Smyke AT, Scheeringa MS, Heller SS, & Zeanah CH (2004). Comparing criteria for attachment disorders: Establishing reliability and validity in high-risk samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 568–577. 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Tarullo AR, & Gunnar MR (2009). Disinhibited social behavior among internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 157–171. 10.1017/S0954579409000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K, Carter MC, Ames E, & Morison S (1995). Attachment security and indiscriminately friendly behavior in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 283–294. 10.1017/S0954579400006507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Bureau JF, Holmes B, Lyubchik A, & Lyons-Ruth K (2009). Quality of early care and childhood trauma: A prospective study of developmental pathways to dissociation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197, 383–390. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a653b7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Bureau J-F, & Lyons-Ruth K (2012). Developmental correlates and predictors of emotional availability in motherchild Interaction: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyden J, Winsper C, Wolke D, Broome MR, & MacCallum F (2016). A systematic review of the parenting and outcomes experienced by offspring of mothers with borderline personality pathology: Potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 85–105. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Lester BM, DeGarmo DS, Lagasse LL, Lin H, Shankaran S, … Higgins R (2011). The combined effects of prenatal drug exposure and early adversity on neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 777–788. 10.1017/S0954579411000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury S, Smyke A, Egger HL, Nelson CA III,… Zeanah CH (2011). Validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: Indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 216–231.e3 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury SS, Smyke AT, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2014). Indiscriminate behaviors in previously institutionalized young children. Pediatrics, 133, e657–e665. 10.1542/peds.2013-0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutheil TG (1989). Borderline personality disorder, boundary violations, and patient-therapist sex: Medicolegal pitfalls. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 597–602. 10.1176/ajp.146.5.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson RP, Patrick M, Crandell L, García-Pérez R, & Lee A (2005). Personal relatedness and attachment in infants of mothers with BPD. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 329–347. 10.1017/S0954579405050169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson RP, Patrick MP, Hobson JA, Crandell L, Bronfman E, & Lyons-Ruth K (2009). How mothers with borderline personality disorder relate to their year-old infants. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 325–330. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges J, & Tizard B (1989). Social and family relationships of exinstitutional adolescents. Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 30, 77–97. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2017). Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: Effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 675–684. 10.1017/S0954579417000256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay C, & Green J (2013). Reactive attachment disorder following early maltreatment: Systematic evidence beyond the institution. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 41, 571–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler JM, Hostinar CE, Mliner SB, & Gunnar MR (2014). Disinhibited social engagement in postinstitutionalized children: Differentiating normal from atypical behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 451–464. 10.1017/S0954579414000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Bronfman E, & Parsons E (1999). Chapter IV. Maternal frightened, frightening, or atypical behavior and disorganized infant attachment patterns. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64, 67–96. 10.1111/1540-5834.00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Bureau JF, Holmes B, Easterbrooks A, & Brooks NH (2013). Borderline symptoms and suicidality/self-injury in late adolescence: Prospectively observed relationship correlates in infancy and childhood. Psychiatry Research, 206, 273–281. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Bureau JF, Riley CD, & Atlas-Corbett AF (2009). Socially indiscriminate attachment behavior in the strange situation: Convergent and discriminant validity in relation to caregiving risk, later behavior problems, and attachment insecurity. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 355–372. 10.1017/S0954579409000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Connell DB, Grunebaum HU, & Botein S (1990). Infants at social risk: Maternal depression and family support services as mediators of infant development and security of attachment. Child Development, 61, 85–98. 10.2307/1131049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Easterbrooks MA, & Cibelli CD (1997). Infant attachment strategies, infant mental lag, and maternal depressive symptoms: Predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7. Developmental Psychology, 33, 681–692. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Moran G, Pederson DR, & Benoit D (2006). Unresolved states of mind, anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: A review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attachment and Human Development, 8, 89–111. 10.1080/14616730600774458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis H, Macmillan S, Pritchett R, Young D, Wallace B, Butcher J, … Gillberg C (2013). Prevalence of reactive attachment disorder in a deprived population. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, 342–346. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.114074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Rutter M, & The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (2000). Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: Extension and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 703–712. 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira PS, Soares I, Martins C, Silva JR, Marques S, Baptista J, & Lyons-Ruth K (2012). Indiscriminate behavior observed in the strange situation among institutionalized toddlers: Relations to caregiver report and to early family risk. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33, 187–196. 10.1002/imhj.20336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsavsky AK, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, & Tottenham N (2013). Indiscriminate amygdala response to mothers and strangers after early maternal deprivation. Biological Psychiatry, 74, 853–860. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Bruce J, Fisher PA, & Kim HK (2010). Indiscriminate friendliness in maltreated foster children. Child Maltreatment, 15, 64–75. 10.1177/1077559509337891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley C, Atlas-Corbett A, & Lyons-Ruth K (2005). Rating of Infant-Stranger Engagement (RISE) coding system Unpublished manual, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School at the Cambridge Hospital, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, & Ratcliff KS (1981). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38, 381–389. 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Colvert E, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, … Sonuga-Barke EJ (2007). Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: Disinhibited attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 17–30. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, Bell C, Kreppner J, Kumsta R, … Stevens S (2010). Deprivation-specific psychological patterns: Effects of institutional deprivation by the English and Romanian Adoptee Study Team. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 75, 1–252. 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper FY, Abrahamse ME, Jonkman CS, Schuengel C, Lindauer RJL, de Vries AL,… Jansen LMC (2016). Inhibited attachment behaviour and disinhibited social engagement behaviour as relevant concepts in referred home reared children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42, 544–552. 10.1111/cch.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Owens E, Vondra J, Keenan K, & Winslow E (1996). Early risk factors and pathways in the development of early disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 679–700. 10.1017/S0954579400007367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Bureau JF, Easterbrooks MA, Zhao X, & Lyons-Ruth K (2012). Childhood maltreatment and prospectively observed quality of early care as predictors of antisocial personality disorder. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33, 55–96. 10.1002/imhj.20295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RI (1992). Treatment boundary violations: Clinical, ethical, and legal considerations. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 20, 269–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Whalen DJ, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, & Levine MD (2012). Children of mothers with borderline personality disorder: Identifying parenting behaviors as potential targets for intervention. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 76–91. 10.1037/a0023081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. (2008). The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young orphanage children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, vii–viii, 1–262, 294 –295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Garvin MC, & Gunnar MR (2011). Atypical EEG power correlates with indiscriminately friendly behavior in internationally adopted children. Developmental Psychology, 47, 417–431. 10.1037/a0021363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn M, Schuengel C, & Bakermans-Kranenburg M (1999). Disorganized attachment in early childhood: A meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequel. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1996). Multiaxial classification of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders in children and adolescents United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Williams AA, Lewis RE, Reich RB, Vera SC, Marino MF, … Frankenburg FR (1997). Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1101–1106. 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, & Gleason MM (2015). Annual research review: Attachment disorders in early childhood—Clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 207–222. 10.1111/jcpp.12347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Scheeringa M, Boris NW, Heller SS, Smyke AT, & Trapani J (2004). Reactive attachment disorder in maltreated toddlers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 877–888. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, & Dumitrescu A (2002). Attachment disturbances in young children. II: Indiscriminate behavior and institutional care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 983–989. 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]