Abstract

Development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is regulated by interactive effects of genetic and environmental risk factors. The most significant genetic risk factor for AD is the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE4), which has been shown to exert greater AD risk in women. An important modifiable AD risk factor is obesity and its associated metabolic dysfunctions. Whether APOE genotype might interact with obesity in females to regulate AD pathogenesis is unclear. To investigate this issue, we studied the effects of Western diet (WD) on female EFAD mice, a transgenic mouse model of AD that includes human APOE alleles ε3 (E3FAD) and ε4 (E4FAD). EFAD mice were fed either control (10% fat, 7% sugar) or WD (45% fat, 17% sugar), and both metabolic and neuropathologic outcomes were determined. Although E4FAD mice generally exhibited poorer metabolic status at baseline, E3FAD mice showed greater diet-induced metabolic impairments. Similarly, E4FAD mice exhibited higher levels of AD-related pathology overall, but only E3FAD showed significant increases on select measures of β-amyloid pathology after exposure to WD. These data demonstrate a gene–environment interaction between APOE and obesogenic diets in females. Understanding how AD-promoting effects of obesity are modulated by genetic factors will foster the identification of at-risk populations and development of preventive interventions.—Christensen, A., Pike, C. J. APOE genotype affects metabolic and Alzheimer-related outcomes induced by Western diet in female EFAD mice.

Keywords: β-amyloid, inflammation, metabolism, microglia, obesity

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disease for which risk is affected by the interaction between several genetic and environmental factors. The most significant, widespread genetic risk factor for late-onset AD is apolipoprotein E allele ε4 (APOE4). Relative to APOE3, the most common APOE allele, APOE4 increases risk for AD up to ∼10-fold in homozygous persons (1, 2). Interestingly, deleterious effects of APOE4 appear to be more robust in women. Compared with male APOE4 carriers, women with APOE4 have been reported to exhibit greater rates of brain atrophy and cognitive decline (3–5) as well as significantly higher AD risk (1, 6, 7), though a recent meta-analysis suggests that the female bias in APOE4 risk is age-dependent (8). Parallel observations of a female bias in AD-related effects of APOE4 have been observed in rodent models. For example, in transgenic mouse models that include familial AD (FAD) transgenes and human APOE alleles, APOE4 mice exhibit a significantly higher β-amyloid (Aβ) burden than APOE3 mice do, with the highest Aβ observed in female APOE4 mice (9, 10).

In addition to genetics, environmental factors also regulate vulnerability to AD. One such factor is obesity, a particularly significant modifiable risk factor given that nearly 40% of adults in the US are obese (11). Indeed, obesity (12, 13) and the obesity-related conditions, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, are all independently associated with increased risk of AD and related dementias (14, 15). Obesity is linked with dementia risk in both men and women; it is unclear whether there are sex differences that affect the strength of this association (16). Similar relationships are evident in transgenic mouse models of AD in which experimental induction of obesity accelerates development of AD-related pathology (17–19). Although male rodents are typically more vulnerable to the metabolic consequences induced by obesity (20, 21), both sexes of AD transgenic mice exhibit obesity-related worsening of AD-related pathology (22).

Despite the significance of APOE4 risk and the high prevalence of obesity, the extent to which APOE genotype interacts with obesity to modulate development of AD is poorly understood. Obesity is a key factor in driving metabolic dysfunction that, in turn, has been identified as a central mechanism by which obesity promotes neural impairment and development of AD (23, 24). Accumulating evidence identifies roles of APOE in the regulation of obesity (25) and various aspects of metabolic function systemically and in brain (26–28). Interestingly, both APOE4 (29, 30) and obesity (31) increase inflammation, which has been implicated in AD pathogenesis (32). Given their numerous sites of functional overlap, APOE and obesity are strong candidates to exhibit gene–environment interactions relevant to the development of AD.

In the present study, we investigated whether APOE alleles affect the relationship between obesity and the development of AD pathology. We used the EFAD mouse model, which has knocked-in human APOE3 (E3FAD) or APOE4 (E4FAD) in the presence of familial AD (FAD) transgenes (33). Because APOE4 affects females more than males, we focused specifically on female EFAD mice. E3FAD and E4FAD females were maintained on either a control (Con) or obesogenic Western diet (WD), after which a range of metabolism, inflammation, behavior, and pathology measurements were compared across groups. The data indicate gene–environment interactions between APOE and obesity that are relevant to AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female EFAD mice were maintained in a colony at the University of Southern California in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12-hr light/dark schedule (lights on at 6:00 am) and ad libitum access to food and water. At 2.5 mo of age, female E3FAD and E4FAD mice were randomly assigned to either Con diet (10% calories from fat and 7% from sugar, D12450J; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or WD (45% calories from fat and 17% from sugar, D12451; Research Diets; n = 7–8/group). Eight animals were enrolled in each group at the start of the study, but 1 E3FAD + Con diet animal was removed from all the analyses when it was found to have values >2 sds from the group mean on multiple outcome measures. Body weight was monitored weekly for the 13-wk diet exposure period. All procedures were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of Southern California (USC) Institution for Animal Care and Use Committee and under the supervision of USC veterinarians.

Glucose tolerance test

A glucose tolerance test was performed 12 wk after the start of the diets. Food was withheld from animals overnight (∼16 h); subsequently, they were orally gavaged with 2 g/kg d-glucose. Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min following glucose administration by collecting 20 μl of blood on a glucose test strip, which was assayed using a Precision Xtra Glucose Monitor (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA).

Spontaneous alternation test

After 11 wk of diet treatment, all animals were tested for spontaneous alternation behavior in the Y maze, a task that is dependent upon the hippocampus and other limbic structures (34) and assesses spatial memory and attention toward novelty (35). Mice were acclimated to the behavior room for ≥30 min prior to testing. They were placed in the long arm of a Y maze and allowed to explore the arena for 5 min. Arm entries were recorded if the animal placed 2 paws into the arm. Three consecutive, nonrepeating entries were considered a correct alteration. Animals with fewer than 20 or more than 50 arm entries were excluded from analysis. These criteria resulted in the removal of 1 mouse from each of the E4FAD groups.

Tissue collection

At the end of the 13-wk treatment period, EFAD mice were euthanized following food withdrawal overnight, after which the brain was rapidly removed and hemisected midsagitally. For each animal, 1 brain half was immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M Sorenson’s phosphate buffer for 72 h at 4°C. The second brain half was immediately frozen at −80°C for subsequent soluble Aβ extraction. Blood was collected and kept on ice prior to centrifugation to collect plasma, which was stored in aliquots at −80° until assayed. The retroperitoneal and visceral (which included gonadal and uterine fat) fat pads were dissected, weighed, and frozen.

Immunohistochemistry

Fixed hemibrains were sectioned exhaustively in the horizontal plane at 40 μm using a vibratome (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were stored singly in PBS with 0.03% sodium azide at 4°C until immunohistochemistry was performed. Every eighth section (from a total of ∼100) was immunostained for Aβ as previously described (36). In brief, tissue sections containing hippocampus were pretreated with 95% formic acid for 5 min, then washed 3 times for 5 min in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), followed by a 10 min rinse with an endogenous peroxidase blocking solution. Next, sections were rinsed in TBS/0.1% Triton-X before being blocked for 30 min in TBS/2% BSA. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-Aβ antibody (1:300, 71-5800; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in the block solution. This antibody has been shown previously by our group to specifically label Aβ deposits and not C-terminal fragments of APP (amyloid precursor protein) (36). For microglial staining, the same procedure was employed except that the formic acid pretreatment was omitted and the primary antibody was Iba-1 (1:2000; Wako, Mountain View, CA, USA). After incubation in primary antibody, sections were washed and incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h. After rinsing, sections were incubated in an avidin-biotin complex using Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) then processed for diaminobenzidene staining (Vector Laboratories). Stained sections were air-dried overnight, dehydrated, and then coverslipped using Krystalon mounting medium (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA).

Microglia quantification

Activated phenotype of microglia was based on morphologic analysis of Iba-1 immunostaining in a manner consistent with prior reports (36–38). Numbers of Iba-1 immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus were estimated by 2-dimensional cell counts using random-sampling based on the optical dissector technique, which has been previously used to estimate the number of total cells in the hippocampus (39, 40). Briefly, an Olympus BX50 microscope equipped with a motorized stage and computer-guided CASTGrid software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for unbiased sampling. In every eighth section containing well-defined CA1-CA3 subregions of hippocampus (4 sections/brain), the hippocampus (excluding the dentate gyrus) was outlined from which high magnification microscopic fields were randomly sampled with an X-Y step of 150 μm × 150 μm. Within each field, cells within a counting frame (3000 μm2) were used for analysis. Microglia were classified as either type 1, (many thin, ramified processes), type 2 (short, thick processes and a rod-shaped cell body), or type 3 (no or few short nonramified processes or many filapodial processes) cells. Type 1 cells were considered resting, whereas the type 2 and 3 microglia were combined and constituted the population with an activated phenotype. In this and all other analyses, the investigator was blind to group membership.

Aβ load

For each brain, 4 sections that contained the hippocampus and had been immunostained with Aβ antibody were imaged on an Olympus BX50 microscope outfitted with an Olympus DP72 camera and CellSens software (Olympus). Brightfield images were taken with a ×20 objective and imported to ImageJ 1.50b (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) in which they were converted to grayscale. These images were measured for percent immunoreactive area, a measure of Aβ load. The measured region of interest of the hippocampus was manually outlined. Coverage of the subiculum was achieved with 2 images, and 3 images were required for CA1. Images were adjusted via thresholding to remove background staining and create a binary image of positive vs. negative immunoreactivity. The proportion of pixels with positive staining was considered the Aβ load.

Thioflavin staining and quantification

Brain sections were processed for thioflavin S stain to determine plaque number and size. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides and allowed to air-dry overnight. The slides were rehydrated and submerged in 1% thioflavin S (MilliporeSigma) for 10 min. The stained slides were dehydrated and coverslipped with Krystalon. When dry, 4 sections covering an area similar to that used for Aβ load were imaged per animal using epifluorescence instead of brightfield lighting. Images were imported into ImageJ 1.50b, converted to binary images, and reversed so that plaques showed as black and the background appeared white. After thresholding to minimize background labeling, the number of plaques and the area of each plaque were measured in the subiculum and CA1 combined.

Soluble Aβ

Brain levels of soluble Aβ species Aβx-38, Aβx-40, and Aβx-42 were determined by multiplex ELISA following serial ultracentrifugation of brain homogenates as previously described (41). Briefly, 1 hemibrain from each animal was homogenized individually in cold TBS containing protease inhibitors (Millipore protease inhibitor set I, 539131; Phosphatase inhibitor sets 2 and 3 P5726 and P0044; MilliporeSigma) using a Pyrex glass dounce tissue homogenizer. The extract was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h in an Optima XPN centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The supernatant, referred to as the TBS-soluble fraction, was aliquoted and frozen at 80°C for later quantification. The pellet was resolubilized in TBS with 1% Triton-X, mixed for 30 min at 4°C, and then centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant, referred to as the TBSX-soluble fraction, was divided into aliquots and frozen at 80°C for later quantification. Both TBS and TBSX-soluble fractions were assayed in duplicate for soluble Aβ species using the Meso Scale Diagnostics (Rockville, MD, USA) Aβ (4G8) V-Plex (K15199E) plate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. During tissue processing, sample from 1 animal in the E4FAD + WD group was destroyed, so it was omitted from analysis.

Leptin ELISA

Fasting levels of leptin in plasma collected at euthanization were determined using mouse leptin (EZML-82K; MilliporeSigma) ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One mouse from the E4FAD + WD group did not give a positive leptin concentration and was excluded from analysis.

PCR

RNA was extracted from visceral adipose tissue by lysis with Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Purified RNA (1 μg) was used for reverse transcription using the iScript synthesis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The resulting cDNA was used for quantitative PCR using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System. The amplification efficiency was estimated from the standard curve for each gene. Relative quantification of mRNA levels from various treated animal hippocampi was determined by the ΔΔCt method. All experimental primers were compared with the average expression of SDHA (succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A) and HPRT (hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase). Primer sequences (Thermo Fisher Scientific) are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Gene targets and their respective PCR primer sequences

| Primer, 5′–3′ | ||

|---|---|---|

| Target | Forward | Reverse |

| CD68 | TTCTGCTGTGGAAATGCAAG | AGAGGGGCTGGTAGGTTGAT |

| F4/80 | TGCATCTAGCAATGGACAGC | GCCTTCTGGATCCATTTGAA |

| IL-6 | AGTTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGA | TCCACGATTTCCCAGAGAAC |

| IL-1β | GGGCCTCAAAGGAAAGAATC | TACCAGTTGGGGAACTCTGC |

| ABCA1 | ATATGCGCTATGTCTGGGGC | GCGACAGAGTAGATCCAGGC |

| CD36 | TATTGGTGCAGTCCTGGCTG | CTGCTGTTCTTTGCCACGTC |

| PLIN2 | GTTATGGTCTTGCCCCAGCT | ATGAAGCCTGCTCAGACCAC |

| SDHA | ACACAGACCTGGTGGAGACC | GGATGGGCTTGGAGTAATCA |

| HPRT | AAGCTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGA | TTGCGCTCATCTTAGGCTTT |

Statistics

All data are reported as means ± sem. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Most data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s post hoc tests where applicable. Body weight and glucose tolerance data were analyzed using 2-way repeated-measure ANOVAs. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Because several comparisons yielded P values only slightly above the significance limit, outcomes with P ≤ 0.10 are also noted. All relevant statistics are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Statistical analyses for each experiment, listed by corresponding figure

| Figure | Main effect | P | Tukey’s multiple comparisons test | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | Starting weights t test; t = 4.6, df = 29 | 0.0001 | ||

| 1A | Finteraction (9, 81) = 10.1 | 0.0001 | 4 wk: E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.05 |

| E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.05 | |||

| 8 wk: E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.01 | |||

| 12 wk: E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.0001 | |||

| E4FAD Con vs. E4FAD WD | 0.001 | |||

| 1B | FAPOE (1, 27) = 9.1 | 0.01 | E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.01 |

| Fdiet (1, 27) = 26.0 | 0.0001 | E4FAD Con vs. E4FAD WD | 0.05 | |

| E3FAD WD vs. E4FAD WD | 0.05 | |||

| 1C | Fdiet (1, 27) = 8.2 | 0.01 | E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.07 |

| 1D | Fdiet (1, 27) = 7.9 | 0.01 | ||

| 2A | Ftime (4, 108) = 207.7 | 0.0001 | 15 min: E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.05 |

| E3FAD WD vs. E4FAD WD | 0.05 | |||

| 2B | Fdiet (1, 27) = 3.2 | 0.09 | ||

| 2C | FAPOE (1, 27) = 5.5 | 0.05 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.09 |

| 2D | FAPOE (1, 26) = 5.6 | 0.05 | ||

| Fdiet (1, 26) = 5.2 | 0.05 | |||

| 3 | FAPOE (1, 25) = 6.1 | 0.05 | E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.05 |

| Fdiet (1, 25) = 5.0 | 0.05 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con, | 0.05 | |

| Finteraction (1, 25) = 4.4 | 0.05 | |||

| 4B | FAPOE (1, 27) = 32.7 | 0.0001 | E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.05 |

| Finteraction (1, 27) = 5.7 | 0.05 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.0001 | |

| Fdiet (1, 27) = 3.1 | 0.09 | |||

| 4C | FAPOE (1, 27) = 14.9 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.05 | |

| 4E | FAPOE (1, 27) = 21.5 | 0.0001 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.01 |

| E3FAD WD vs. E4FAD WD | 0.10 | |||

| 4F | Fdiet (1, 27) = 8.5 | 0.01 | E3FAD Con vs. E3FAD WD | 0.05 |

| 5A | FAPOE (1, 26) = 7.6 | 0.05 | ||

| 5B | FAPOE (1, 26) = 8.9 | 0.01 | ||

| 5C | FAPOE (1, 26) = 6.3 | 0.05 | ||

| 5D | FAPOE (1, 26) = 6.6 | 0.05 | ||

| 5E | FAPOE (1, 26) = 3.0 | 0.10 | ||

| 5F | FAPOE (1, 26) = 4.6 | 0.05 | ||

| 6B | FAPOE (1, 27) = 36.0 | 0.0001 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.001 |

| E3FAD WD vs. E4FAD WD | 0.01 | |||

| 6C | FAPOE (1, 27) = 23.2 | 0.0001 | E3FAD Con vs. E4FAD Con | 0.001 |

| Finteraction (1, 27) = 4.9 | 0.05 | |||

| 7A | Fdiet (1, 26) = 5.4 | 0.05 | ||

| 7B | Fdiet (1, 26) = 11.4 | 0.01 | E4FAD Con vs. E4FAD WD | 0.01 |

| 7C | Fdiet (1, 24) = 4.6 | 0.05 | ||

| 7D | FAPOE (1, 23) = 5.4 | 0.05 | ||

| 7E | FAPOE (1, 27) = 4.2 | 0.05 | ||

| 7F | FAPOE (1, 27) = 4.0 | 0.056 | ||

| 7G | Fdiet (1, 27) = 4.9 | 0.05 |

RESULTS

Effects of APOE allele and WD on metabolic measures

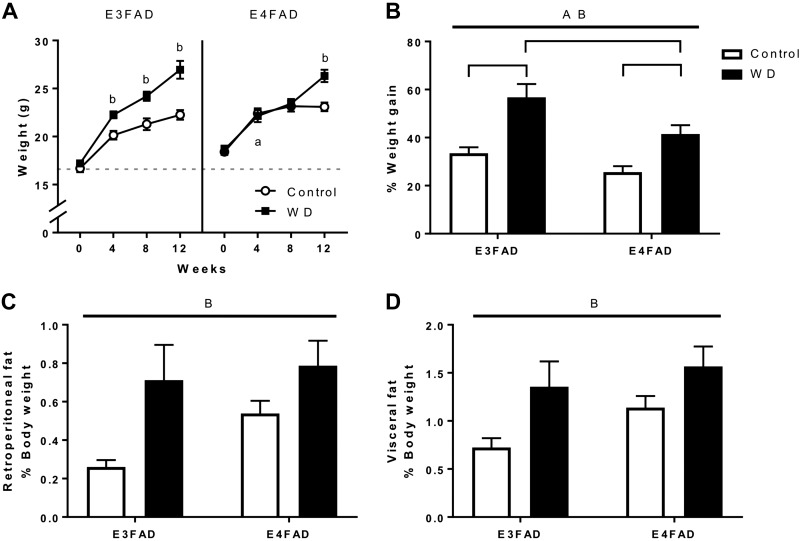

Female EFAD mice were fed Con diet or WD for 13 wk. E4FAD mice had higher baseline body weight at age 10 wk in comparison to age-matched E3FAD mice (Fig. 1A), but by the end of the experiment E3FAD and E4FAD mice fed Con diet did not significantly differ in body weight (Fig. 1A). Both E3FAD and E4FAD mice fed WD gained a significant amount of body weight, though significant weight gain was achieved after 4 wk of diet for E3FAD but not until 12 wk for E4FAD (Fig. 1A). Both diet and APOE genotype independently affected the percent weight gain across the experimental period with higher weight gain observed in E3FAD and with WD (Fig. 1B). Similar effects were observed in adiposity. Compared with mice fed Con diet, E3FAD mice fed WD showed 173 and 89% increases in retroperitoneal and visceral fat pads, respectively, whereas E4FAD mice showed 46 and 38% increases. However, statistical analyses revealed significant effects on weights of the retroperitoneal and visceral fat pads by diet but not by APOE genotype (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on body weight and adipose tissue in EFAD mice. A) Body weights of E3FAD and E4FAD females fed Con diet (white) or WD (black) were measured at initiation and at 4-wk intervals. B) The percent weight gained from the initiation of diet to the end of the experiment. C, D) The weights of retroperitoneal (C) and visceral (D) fat pads are displayed as determined at the conclusion of the study. Fat pad weights are presented as a percentage of total body weight. All data are represented as means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); main effect of diet (B); P < 0.05 vs. opposite genotype only for Con diet (a); P < 0.05 vs. same genotype fed Con diet (b). Brackets indicate significant comparisons between groups.

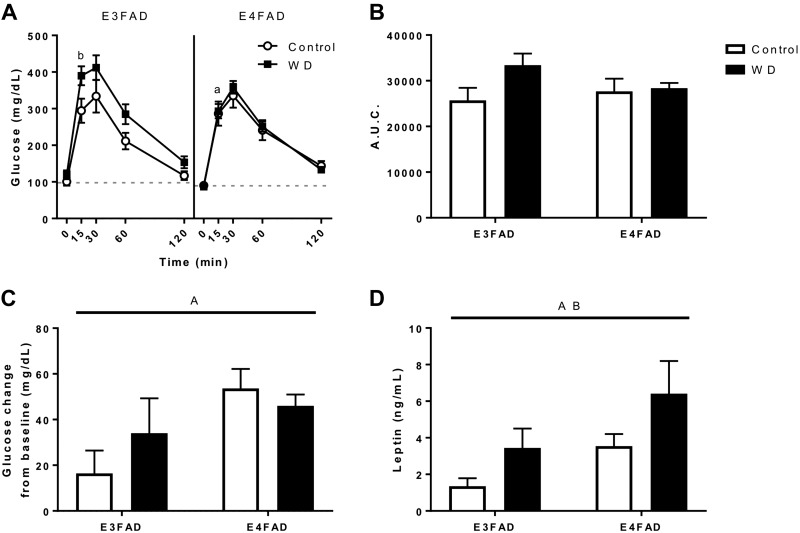

To assess the metabolic consequences of increased body weight and adiposity, we first performed an oral glucose tolerance test. E3FAD mice fed WD showed a significant increase in blood glucose at 15 and 30 min, but there was no significant change in the E4FAD glucose levels associated with WD at any time point (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the glucose data by the area under the curve showed a trend of increased glucose with WD that fell short of statistical significance (Fig. 2B). Glucose tolerance was also assessed by measuring the return of blood glucose to baseline fasting levels 120 min after the glucose bolus. E4FAD mice performed significantly worse than E3FAD mice at returning to their baseline glucose levels, but there was no significant effect caused by diet (Fig. 2C). Finally, we measured fasting leptin levels in plasma by ELISA. Leptin was significantly increased by both WD and APOE4 genotype with E4FAD mice showing increased levels compared with E3FAD mice (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on metabolic outcomes in EFAD mice. A) An oral glucose tolerance test was administered after 12 wk on Con diet (white) or WD (black). B) The area under the curve was calculated from the glucose tolerance test across all time points. C) The difference between the glucose measurement at the 120 min time point was compared with the initial glucose measurement (0 min) to determine the glucose change from baseline. D) Fasting levels of leptin were measured by ELISA from plasma collected at time of euthanasia. All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); main effect of diet (B); P < 0.05 vs. opposite genotype only for WD (a); P < 0.05 vs. same genotype fed Con diet (b). Brackets indicate significant comparisons between groups.

AD-related pathology is affected by WD only in E3FAD mice

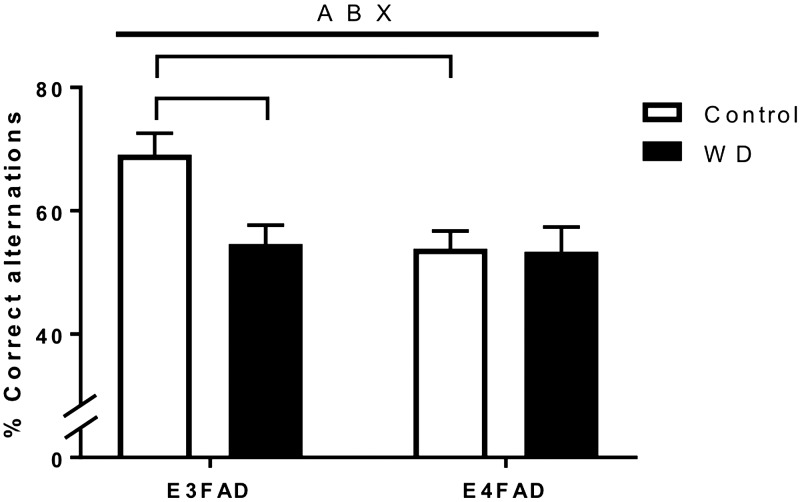

Animals were behaviorally assessed using the spontaneous alternation test, which involves working memory. There was a significant overall effect of APOE status, with the E4FAD mice performing worse on this task. There was also an interaction between diet and APOE allele such that E3FAD but not E4FAD mice showed significantly poorer performance when fed WD (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on spontaneous alternation behavior in EFAD mice. Percent correct alternations were measured in the Y maze to assess working memory in EFAD females fed Con diet (white) or WD (black). All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); main effect of diet (B); interactive effects of genotype and diet (X). Brackets indicate significant comparisons between groups.

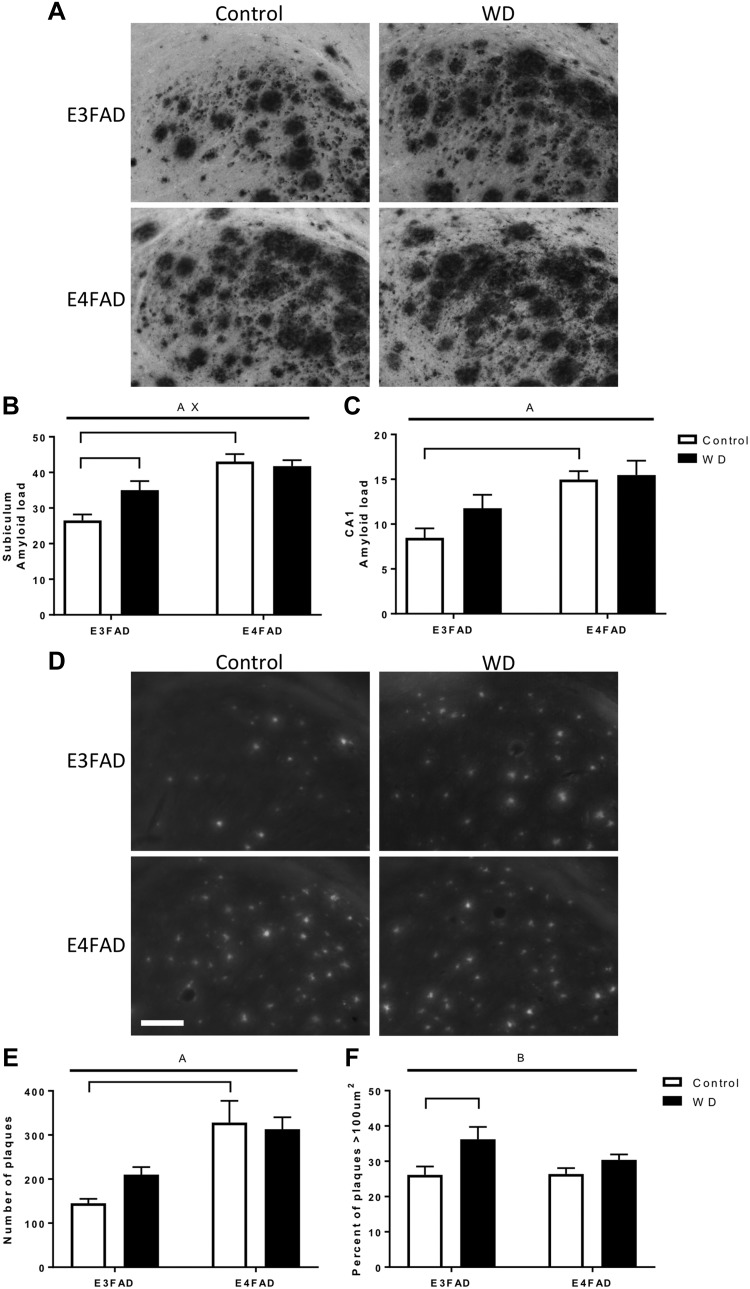

Aβ-related pathology was measured by 3 methods. First, deposition of Aβ was measured by quantitative Aβ immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4A). Aβ load in the subiculum and CA1 region of the hippocampus was significantly higher in E4FAD mice compared with E3FAD mice (Fig. 4B, C). Relative to Con diet, E3FAD mice fed WD exhibited significantly higher Aβ load in subiculum and a nonsignificant trend toward higher levels in CA1; E4FAD mice showed no evidence of diet-induced changes in Aβ load (Fig. 4B, C).

Figure 4.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on Aβ load and thioflavin plaques in EFAD mice. A) Representative images of Aβ immunostaining in the hippocampus of EFAD females fed Con diet (white) or WD (black). B, C) Aβ load was quantified in both the subiculum (B) and CA1 (C) regions of the hippocampus. D) Thioflavin-S was used to stain amyloid plaques. E) Thioflavin positive plaques in the combined subiculum and CA1 regions of the hippocampus were counted. F) Plaque sizes were measured and sorted into groups measuring <100 µm2 and >100 µm2. Scale bar, 100 µm. All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); main effect of diet (B); interactive effects of genotype and diet (X). Brackets indicate significant comparisons between groups.

Second, thioflavin S was used to determine the number and size of mature amyloidogenic plaques. The number but not the size of amyloid plaques was significantly affected by APOE status, with E4FAD mice having more plaques than E3FAD mice (Fig. 4E). WD was associated with a statistically nonsignificant trend of increased plaque number only in E3FAD mice and a significant increase in the percentage of large (>100 µm2) plaques in E3FAD but not E4FAD mice (Fig. 4F).

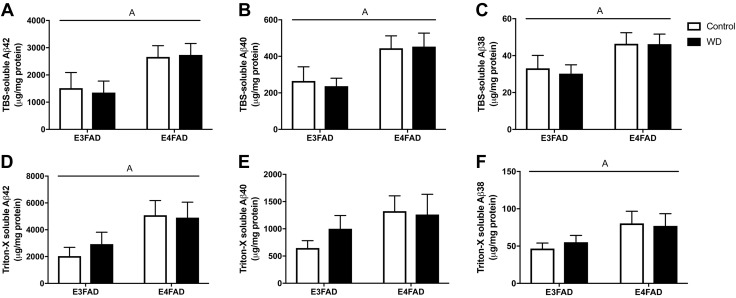

Lastly, to measure soluble forms of Aβ, TBS-soluble and detergent TBSX (TBS with Triton X-100)–soluble fractions of hemibrain were extracted and analyzed by multiplex for 3 species of Aβ: Aβ42, Aβ40, and Aβ38. There was a significant main effect of APOE genotype in the TBS-soluble fraction for all Aβ species (Fig. 5A–C). In the TBSX-soluble fraction, there was a main effect of APOE genotype for Aβ42 and Aβ38, but not in Aβ40 (Fig. 5D–F). Exposure to WD did not significantly affect levels of Aβ42, Aβ40, or Aβ38 in either the TBS-soluble or the detergent TBSX–soluble fraction regardless of APOE genotype.

Figure 5.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on levels of soluble Aβ in EFAD mice. Soluble Aβ species in EFAD mice fed Con diet (white) or WD (black) were determined from 2 serially collected fractions of brain homogenates, the TBS-soluble fraction (A–C), and the Triton-X-soluble fraction (D–F). Within each fraction, multiplex ELISA was used to simultaneously quantify levels of 3 amyloid species, Aβ42 (A, D), Aβ40 (B, E), and Aβ38 (C, F). All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A).

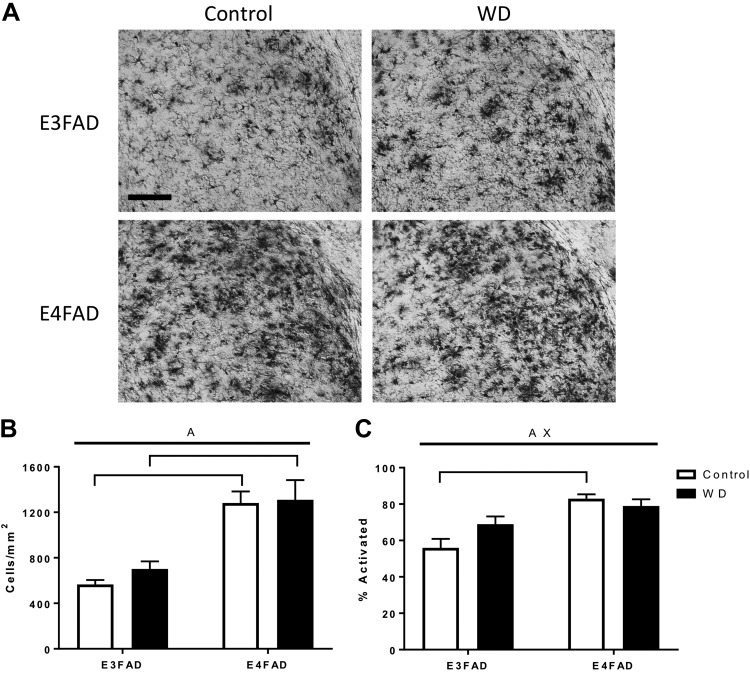

Microglia number and activation are affected by APOE status

Microglial density and activated morphologic phenotype were quantified across the hippocampus following Iba-1 immunostaining. There was a significant main effect of APOE allele on the density of microglia, with higher amounts of microglia in E4FAD mice (Fig. 6A, B); however, microglia density was not significantly affected by WD. Activated microglia phenotype showed a significant main effect of APOE and a significant APOE–diet interaction, with higher proportions of activated microglia in E4FAD regardless of diet, but a nonsignificant increase in activation after WD in E3FAD (Fig. 6A, C).

Figure 6.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on hippocampal microglia in EFAD mice. A) Following exposure of female EFAD mice to Con diet (white) or WD (black), brain sections were immunostained for microglia. Representative images of Iba-1 immunostaining in the hippocampus, with higher levels of labeled cells apparent in E4FAD mice. B) The density of Iba-1 immunolabeled microglia in hippocampus was determined across groups. C) Microglia were morphologically characterized as activated or resting phenotypes. The percent of activated microglia is shown. Scale bar, 100 µm. All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); interactive effects of genotype and diet (X). Brackets indicate significant comparisons between groups.

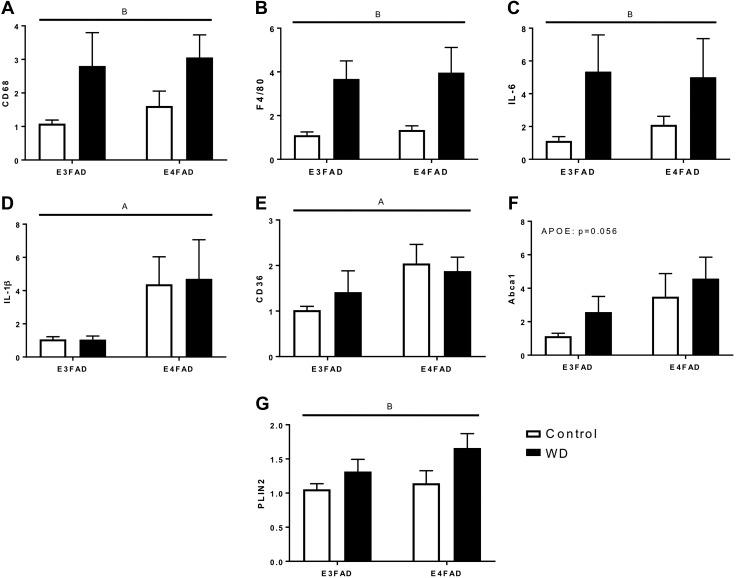

Adipose tissue inflammation is affected primarily by diet

As a measure of peripheral inflammation, we assessed gene expression of various macrophage markers and cytokines in visceral adipose tissue using quantitative PCR. Expression of both CD68 and F4/80 (EGF-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 1) mRNAs, markers of macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, were significantly increased by WD but not significantly affected by APOE allele (Fig. 7A, B). Similarly, cytokine IL-6 was increased by WD but not changed by APOE status (Fig. 7C), whereas IL-1β was significantly increased by APOE4 genotype but not WD (Fig. 7D). Because APOE4 mice showed baseline differences in some metabolic measures, we also probed for markers of metabolic macrophages to explore differences in genotype and responses to WD. Three markers have been shown to be associated with metabolic macrophages: CD36, ABCA1 (ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1), and PLIN2 (perilipin 2) (42). CD36 expression levels were significantly increased in the adipose tissue of E4FAD mice, but were not affected by diet; a similar but statistically nonsignificant trend was observed with ABCA1 (Fig. 7E, F). Expression of PLIN2 was not significantly influenced by APOE genotype but was significantly increased by WD (Fig. 7G).

Figure 7.

Effects of WD and APOE genotype on mRNA expression of macrophage markers in adipose tissue. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to quantify mRNA expression levels of genes associated with macrophages, inflammation, or both in visceral adipose tissue from female EFAD mice fed Con diet (white) or WD (black). Relative expression of general macrophage markers CD68 (A) and F4/80 (B), inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (C) and IL-1β (D) and metabolic macrophage markers ABCA1 (E), CD36 (F) and PLIN2 (G) were measured. All data are means + sem. Lines indicate significant main effects: main effect of APOE (A); main effect of diet (B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the relations among APOE genotype, obesity, and development of AD-related pathology in females using the EFAD mouse model of AD. We made several significant observations. First, in agreement with the well-established association between APOE4 and increased risk of AD (43, 44), we observed higher levels of AD-like pathology in E4FAD mice relative to E3FAD mice. This finding reinforces prior reports in EFAD mice in which APOE4 genotype has been shown to yield earlier onset and increased overall levels of neuropathology and behavioral impairment relative to APOE3 (9, 33). Perhaps most importantly, we observed a gene–environment interaction in which diet-induced obesity was associated with modest but significant increases in select components of AD-related pathology and impaired behavioral performance specifically in E3FAD mice. There were several differences between E3FAD and E4FAD mice on measures of metabolic function and inflammation that may contribute to the observed differences. Particularly compelling are the findings that the obesogenic diet induced greater weight gain and generally poorer metabolic function in E3FAD mice, although E4FAD mice exhibited greater impairment at baseline. It is important to note that the present results qualitatively differ from the APOE and diet interactions we previously reported in male EFAD mice, in which E4FAD but not E3FAD mice showed increased AD pathology following obesogenic diet (37).

Our findings provide the first experimental evidence in a rodent model that the relationship between metabolic dysfunction and increased AD risk is strongest in APOE4 noncarriers. We observed that female E3FAD mice gained more body weight and showed higher relative changes in adiposity in response to obesogenic diet than E4FAD mice, findings that are consistent with prior reports on the effects of obesogenic diets in female mice with targeted replacement of APOE (45, 46). The mechanisms underlying APOE-associated differences in weight gain remain to be fully defined but may involve a metabolic shift in APOE4 mice toward increased lipid oxidation (47). Further, it is noteworthy that APOE genotype also regulates energy metabolism in brain of female, targeted replacement APOE mice (48). We observed that the metabolic profile of E4FAD females under Con diet conditions was generally poorer than that of E3FAD mice. It is unclear whether metabolic function in E4FAD mice contributed to, resulted from, or was unrelated to their significantly poorer behavioral performance and higher pathology burden under basal conditions. In healthy postmenopausal women, relatively poorer metabolic profile is associated with significantly worse cognitive function (49), a relationship that may be exacerbated by APOE4 genotype (50). Importantly, we found that upon challenge with an obesogenic diet, E3FAD mice showed greater glucose intolerance than E4FAD mice. Consistent with our mixed findings on APOE genotype and metabolic phenotype, others have found greater hyperinsulinemia in obese APOE3 females (45) but also evidence of generally similar metabolic responses to obesogenic diet in APOE3 vs. APOE4 females (45, 46). The critical new observation here is that obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction is associated with increased AD-like changes in E3FAD but not in E4FAD mice.

Although obesity and associated metabolic impairments are established risk factors for the development of AD (16), the extent to which APOE genotype impacts this relationship continues to be determined. There are reports that obesity increases AD risk specifically in APOE4 carriers (51, 52), however most studies find that the relationship between metabolic impairments and AD risk is strongest in APOE4 noncarriers (28, 53–57). For example, risk of AD was reported as increased by either being overweight or having type 2 diabetes specifically in APOE4 noncarriers (55). Consistent with our rodent data, Hanson et al. (56) found that although women APOE4 carriers under normal conditions had poorer glucose tolerance than women APOE4 noncarriers, a significant relationship between glucose tolerance and plasma Aβ was observed only in APOE4 noncarriers. Similarly, another report showed that fasting glucose was positively correlated with cerebral Aβ burden only in APOE4 noncarriers (57). Our rodent data provide experimental support for the argument that the relationship between metabolic dysfunction, Aβ accumulation, and AD risk is strongest in APOE4 noncarriers and provides a model system to identify contributing mechanisms and intervention strategies.

Inflammation is a compelling candidate mechanism by which several genetic and environmental factors have been linked with AD risk. Systemic and neural inflammation are implicated as key components in the development and progression of AD pathogenesis (32, 58, 59). Because obesity induces elevated inflammation in brain and peripheral tissues (31, 60, 61), inflammatory pathways have been implicated in mediating obesity-related AD risk (62). Similarly, APOE4 is associated with increased inflammation, which in turn is one of several mechanisms implicated in APOE4 promotion of AD (63). However, despite the strong conceptual connections among obesity, APOE4, inflammation, and AD, our data in female EFAD mice do not provide clear support for causal relationships. In adipose tissue, we observed significant effects of both APOE genotype and diet, but no significant APOE–diet interactions. Specifically, the obesogenic diet was associated with evidence of increased macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue of both APOE genotypes, which is indicative of obesity-induced inflammation and consistent with parallel increases in IL-6 expression. Independent of diet, the APOE4 genotype showed higher levels of CD36 and a similar trend for ABCA1, 2 markers of metabolic macrophages (42), as well as increased IL-1β relative to E3FAD mice. Metabolic macrophages are activated by fatty acids and are thought to play a role in the development and progression of metabolic syndrome and lipid usage (42). The potential contributions of metabolic macrophages to our observations that E4FAD mice appear metabolically impaired in the absence of obesogenic diet and show only modest diet-induced increases in adiposity are intriguing. In comparison, our analyses of microglia, the brain’s macrophages, showed APOE genotype effects but no significant diet effects. We observed that levels of microglia density and activated phenotype were significantly higher in E4FAD mice. Microglia measures were not significantly altered by an obesogenic diet, although there was a significant interaction between APOE genotype and diet in which activated microglial phenotype differed between E3FAD and E4FAD mice only when fed Con diet. The Aβ neuropathology mirrored the microglial measures, with E4FAD mice showing the greatest Aβ burden but no further increase with WD. In summary, the lack of concordance between adipose tissue and the brain on markers of macrophage activation suggests that obesity exerts different effects on peripheral vs. CNS tissues. Further, although we do not dispute the potentially important role of inflammation in the initiation or progression of AD pathology, our observations are not consistent with these pathways as the primary mechanism by which APOE genotype and obesity interact in the regulation of AD-like pathology in female EFAD mice.

Sex likely modulates the relationships among APOE genotype, obesity, and the development of AD-related pathology. AD is characterized by numerous sex differences including prevalence, incidence, strength of risk factors, and the clinical and pathologic progression of the disease (64). One particularly relevant sex difference is that APOE4-associated AD risk exhibits a significant female bias (1, 6, 7). In AD transgenic models with human APOE knock-in, APOE4 female mice show greater levels of neuropathology than APOE4 males (9, 10). The extent to which sex affects the increased risk of AD associated with obesity is less clear. There is evidence that obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors increase dementia risk more strongly in women than men (65, 66), though the relationships between sex, obesity and dementia are complex and remain to be fully elucidated (16). Our results provide an important new addition to this literature in that they indicate a sex difference in the effects of the gene–environment interaction between APOE and diet-induced obesity on development of AD-related pathology. In the current study of female EFAD mice, we find that obesity increases select components of Aβ accumulation specifically in APOE3 mice. In a similar study of male EFAD mice, we recently reported a qualitatively different result in which obesity was associated with higher Aβ pathology only in APOE4 mice (37). Thus, although APOE4 generally yields poorer neural outcomes in females, we find that obesity interactions with APOE4 are limited to males in EFAD mice. This sex difference in APOE4 is generally consistent with recent findings by Nam and colleagues, who studied diet-induced obesity in male and female APP/PS1Δ9 (presenilin-1 Δ exon 9) mice that were homozygous for human APOE3 or APOE4 (10). They observed that obesogenic diet increased plaque burden only in APOE4 mice, though the effect was much stronger in males than females. Our finding that diet-induced worsening of AD-related pathology in female E3FAD mice was observed in only select measures of Aβ is consistent with observations that metabolic consequences of diet-induced obesity are significantly stronger in male vs. female rodents (16). Why sex impacts gene–environment interactions between APOE genotype and obesity on AD outcomes will require additional investigation. It is of interest that not only are there numerous sex differences in rodents and humans in the metabolic responses to obesity (16) but also that APOE may regulate metabolic outcomes differently based on sex.

There is a limitation of this study in that the extensive pathology and behavioral impairment in E4FAD mice may restrict the ability to detect further worsening of outcomes in response to obesogenic diet. EFAD mice were 5.5 mo of age at the conclusion of the experiment, at which point E4FAD mice exhibited robust accumulation of Aβ in subiculum, high levels of microglial activation, and significant behavioral impairment. It can be argued that the diminished potential for additional increases in both pathology and behavioral dysfunction reduces the likelihood of observing negative consequences of WD in the E4FAD mice. However, EFAD mice show age-related increases in pathology and reductions in cognition through ≥8 mo of age (reviewed in (67). Further, the EFAD model was generated from the 5xFAD mouse, which exhibits progressive worsening of pathology and behavior through ≥16 mo of age (67). Thus, although extensive, the AD-related outcomes at the age of 5.5 mo are not maximal. Nonetheless, even though the data clearly indicate negative consequences of an obesogenic diet in E3FAD females, there is a reduced ability to conclude that specific outcome measures were not adversely affected by diet in E4FAD females. One example is spontaneous alternation behavior, which was reduced in female E3FAD mice from ∼70% alternations in Con diet to ∼55% in WD but in female E4FAD mice showed no further reduction by WD from the ∼55% alternation level observed under Con diet. Our prior findings in aged 3xTg-AD mice demonstrate that alternation levels can dip to as low as ∼40% with very high levels of AD-related pathology (68). Although the E4FAD mice in this study did not reach the lower limit of performance in the spontaneous alternation task, the smaller window for behavioral decrement prevents the conclusion that WD did not impair their cognition.

In summary, we identify a gene–environment interaction in which obesity increases the severity of AD-related outcomes, specifically in APOE3 female mice. This finding extends the growing literature on the gene–environment interactions of APOE with risk factors for impaired cognition and dementia (37, 69). Although APOE4 mice are more vulnerable to AD-like pathology and exhibit generally poorer metabolic and inflammatory profiles than APOE3 mice, our observations suggest that female APOE4 mice can exhibit lesser perturbation to an environmental stressor and a corresponding resistance to further increases in pathology. This paradox of a relatively benign gene–environment interaction with APOE4 is consistent with recent observations in the forager-horticulturist Tsimane population, in which APOE4 carriers showed maintained or improved cognition relative to APOE4 noncarriers challenged with high parasite and pathogen burden (70). Because sex impacts the effects of APOE as well as responses to metabolic and inflammatory stressors, it is likely that sex significantly impacts numerous interactions among AD risk factors. Additional research in both human populations and rodent models is necessary to define further the scope of APOE interactions with environmental risk factors for AD, to elucidate key underlying mechanisms, and to understand how sex may regulate these relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging Grant AG026572 (to C.J.P.). A.C. was supported, in part, by the NIH National Institute on Aging Grant T32 AG052374. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- Con

control

- EFAD

early onset familial AD

- FAD

familial AD

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TBSX

Tris-buffered saline with Triton X-100

- WD

Western diet

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Christensen performed the research; and A. Christensen and C. J. Pike designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farrer L. A., Cupples L. A., Haines J. L., Hyman B., Kukull W. A., Mayeux R., Myers R. H., Pericak-Vance M. A., Risch N., van Duijn C. M. (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. JAMA 278, 1349–1356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward A., Crean S., Mercaldi C. J., Collins J. M., Boyd D., Cook M. N., Arrighi H. M. (2012) Prevalence of apolipoprotein E4 genotype and homozygotes (APOE e4/4) among patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 38, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley R. F., Mormino E. C., Amariglio R. E., Properzi M. J., Rabin J. S., Lim Y. Y., Papp K. V., Jacobs H. I. L., Burnham S., Hanseeuw B. J., Doré V., Dobson A., Masters C. L., Waller M., Rowe C. C., Maruff P., Donohue M. C., Rentz D. M., Kirn D., Hedden T., Chhatwal J., Schultz A. P., Johnson K. A., Villemagne V. L., Sperling R. A.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative ; Australian Imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle Study of Ageing ; Harvard Aging Brain Study (2018) Sex, amyloid, and APOE ε4 and risk of cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: findings from three well-characterized cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beydoun M. A., Boueiz A., Abougergi M. S., Kitner-Triolo M. H., Beydoun H. A., Resnick S. M., O’Brien R., Zonderman A. B. (2012) Sex differences in the association of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele with incidence of dementia, cognitive impairment, and decline. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 720–731.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Paajanen T., Westman E., Wahlund L.-O., Simmons A., Tunnard C., Sobow T., Proitsi P., Powell J., Mecocci P., Tsolaki M., Vellas B., Muehlboeck S., Evans A., Spenger C., Lovestone S., Soininen H.; AddNeuroMed Consortium (2010) Effect of APOE ε4 allele on cortical thicknesses and volumes: the AddNeuroMed study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21, 947–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altmann A., Tian L., Henderson V. W., Greicius M. D.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Investigators (2014) Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 75, 563–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payami H., Montee K. R., Kaye J. A., Bird T. D., Yu C. E., Wijsman E. M., Schellenberg G. D. (1994) Alzheimer’s disease, apolipoprotein E4, and gender. JAMA 271, 1316–1317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neu S. C., Pa J., Kukull W., Beekly D., Kuzma A., Gangadharan P., Wang L.-S., Romero K., Arneric S. P., Redolfi A., Orlandi D., Frisoni G. B., Au R., Devine S., Auerbach S., Espinosa A., Boada M., Ruiz A., Johnson S. C., Koscik R., Wang J.-J., Hsu W.-C., Chen Y.-L., Toga A. W. (2017) Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 74, 1178–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacciottolo M., Christensen A., Moser A., Liu J., Pike C. J., Smith C., LaDu M. J., Sullivan P. M., Morgan T. E., Dolzhenko E., Charidimou A., Wahlund L.-O., Wiberg M. K., Shams S., Chiang G. C.-Y., Finch C. E.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2016) The APOE4 allele shows opposite sex bias in microbleeds and Alzheimer’s disease of humans and mice. Neurobiol. Aging 37, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nam K. N., Wolfe C. M., Fitz N. F., Letronne F., Castranio E. L., Mounier A., Schug J., Lefterov I., Koldamova R. (2018) Integrated approach reveals diet, APOE genotype and sex affect immune response in APP mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1864, 152–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flegal K. M., Kruszon-Moran D., Carroll M. D., Fryar C. D., Ogden C. L. (2016) Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 315, 2284–2291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzpatrick A. L., Kuller L. H., Lopez O. L., Diehr P., O’Meara E. S., Longstreth W. T., Jr., Luchsinger J. A. (2009) Midlife and late-life obesity and the risk of dementia: cardiovascular health study. Arch. Neurol. 66, 336–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Profenno L. A., Porsteinsson A. P., Faraone S. V. (2010) Meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease risk with obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biessels G. J., and Luchsinger J. A., eds. (2010) Diabetes and the Brain, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strachan M. W. J., Reynolds R. M., Marioni R. E., Price J. F. (2011) Cognitive function, dementia and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser V. A., Pike C. J. (2016) Obesity and sex interact in the regulation of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 67, 102–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho L., Qin W., Pompl P. N., Xiang Z., Wang J., Zhao Z., Peng Y., Cambareri G., Rocher A., Mobbs C. V., Hof P. R., Pasinetti G. M. (2004) Diet-induced insulin resistance promotes amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 18, 902–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julien C., Tremblay C., Phivilay A., Berthiaume L., Emond V., Julien P., Calon F. (2010) High-fat diet aggravates amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 1516–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohjima M., Sun Y., Chan L. (2010) Increased food intake leads to obesity and insulin resistance in the Tg2576 Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Endocrinology 151, 1532–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang L.-L., Wang C.-H., Li T.-L., Chang S.-D., Lin L.-C., Chen C.-P., Chen C.-T., Liang K.-C., Ho I.-K., Yang W.-S., Chiou L.-C. (2010) Sex differences in high-fat diet-induced obesity, metabolic alterations and learning, and synaptic plasticity deficits in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18, 463–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medrikova D., Jilkova Z. M., Bardova K., Janovska P., Rossmeisl M., Kopecky J. (2012) Sex differences during the course of diet-induced obesity in mice: adipose tissue expandability and glycemic control. Int. J. Obes. 36, 262–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barron A. M., Rosario E. R., Elteriefi R., Pike C. J. (2013) Sex-specific effects of high fat diet on indices of metabolic syndrome in 3xTg-AD mice: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8, e78554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De la Monte S. M. (2014) Relationships between diabetes and cognitive impairment. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 43, 245–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien P. D., Hinder L. M., Callaghan B. C., Feldman E. L. (2017) Neurological consequences of obesity. Lancet Neurol. 16, 465–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kypreos K. E., Karavia E. A., Constantinou C., Hatziri A., Kalogeropoulou C., Xepapadaki E., Zvintzou E. (2018) Apolipoprotein E in diet-induced obesity: a paradigm shift from conventional perception. J. Biomed. Res. 32, 183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao Z., Hu B., Zheng J., Zheng W., Chen X., Gao X., Xie Y., Fang L.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2015) A FDG-PET study of metabolic networks in apolipoprotein E ε4 allele carriers. PLoS One 10, e0132300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ossenkoppele R., van der Flier W. M., Zwan M. D., Adriaanse S. F., Boellaard R., Windhorst A. D., Barkhof F., Lammertsma A. A., Scheltens P., van Berckel B. N. M. (2013) Differential effect of APOE genotype on amyloid load and glucose metabolism in AD dementia. Neurology 80, 359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris J. K., Uy R. A. Z., Vidoni E. D., Wilkins H. M., Archer A. E., Thyfault J. P., Miles J. M., Burns J. M. (2017) Effect of APOE ε4 genotype on metabolic biomarkers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 58, 1129–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch J. R., Tang W., Wang H., Vitek M. P., Bennett E. R., Sullivan P. M., Warner D. S., Laskowitz D. T. (2003) APOE genotype and an ApoE-mimetic peptide modify the systemic and central nervous system inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48529–48533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitek M. P., Brown C. M., Colton C. A. (2009) APOE genotype-specific differences in the innate immune response. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1350–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotamisligil G. S. (2006) Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heneka M. T., Carson M. J., El Khoury J., Landreth G. E., Brosseron F., Feinstein D. L., Jacobs A. H., Wyss-Coray T., Vitorica J., Ransohoff R. M., Herrup K., Frautschy S. A., Finsen B., Brown G. C., Verkhratsky A., Yamanaka K., Koistinaho J., Latz E., Halle A., Petzold G. C., Town T., Morgan D., Shinohara M. L., Perry V. H., Holmes C., Bazan N. G., Brooks D. J., Hunot S., Joseph B., Deigendesch N., Garaschuk O., Boddeke E., Dinarello C. A., Breitner J. C., Cole G. M., Golenbock D. T., Kummer M. P. (2015) Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youmans K. L., Tai L. M., Nwabuisi-Heath E., Jungbauer L., Kanekiyo T., Gan M., Kim J., Eimer W. A., Estus S., Rebeck G. W., Weeber E. J., Bu G., Yu C., Ladu M. J. (2012) APOE4-specific changes in Aβ accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41774–41786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalonde R. (2002) The neurobiological basis of spontaneous alternation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 26, 91–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes R. N. (2004) The value of spontaneous alternation behavior (SAB) as a test of retention in pharmacological investigations of memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen A., Pike C. J. (2017) Age-dependent regulation of obesity and Alzheimer-related outcomes by hormone therapy in female 3xTg-AD mice. PLoS One 12, e0178490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser V. A., Pike C. J. (2017) Obesity accelerates Alzheimer-related pathology in APOE4 but not APOE3 mice. eNeuro 4, ENEURO.0077-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekdahl C. T. (2012) Microglial activation—tuning and pruning adult neurogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 3, 41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramsden M., Shin T. M., Pike C. J. (2003) Androgens modulate neuronal vulnerability to kainate lesion. Neuroscience 122, 573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jayaraman A., Christensen A., Moser V. A., Vest R. S., Miller C. P., Hattersley G., Pike C. J. (2014) Selective androgen receptor modulator RAD140 is neuroprotective in cultured neurons and kainate-lesioned male rats. Endocrinology 155, 1398–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christensen A., Pike C. J. (2018) TSPO ligand PK11195 improves Alzheimer-related outcomes in aged female 3xTg-AD mice. Neurosci. Lett. 683, 7–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kratz M., Coats B. R., Hisert K. B., Hagman D., Mutskov V., Peris E., Schoenfelt K. Q., Kuzma J. N., Larson I., Billing P. S., Landerholm R. W., Crouthamel M., Gozal D., Hwang S., Singh P. K., Becker L. (2014) Metabolic dysfunction drives a mechanistically distinct proinflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue macrophages. Cell Metab. 20, 614–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J.-T., Tan L., Hardy J. (2014) Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 37, 79–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corder E. H., Saunders A. M., Strittmatter W. J., Schmechel D. E., Gaskell P. C., Small G. W., Roses A. D., Haines J. L., Pericak-Vance M. A. (1993) Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 261, 921–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huebbe P., Dose J., Schloesser A., Campbell G., Glüer C. C., Gupta Y., Ibrahim S., Minihane A. M., Baines J. F., Nebel A., Rimbach G. (2015) Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype regulates body weight and fatty acid utilization—studies in gene-targeted replacement mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 59, 334–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson L. A., Torres E. R. S., Impey S., Stevens J. F., Raber J. (2017) Apolipoprotein E4 and insulin resistance interact to impair cognition and alter the epigenome and metabolome. Sci. Rep. 7, 43701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arbones-Mainar J. M., Johnson L. A., Torres-Perez E., Garcia A. E., Perez-Diaz S., Raber J., Maeda N. (2016) Metabolic shifts toward fatty-acid usage and increased thermogenesis are associated with impaired adipogenesis in mice expressing human APOE4. Int. J. Obes. 40, 1574–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L., Zhang X., Zhao L. (2018) Human ApoE isoforms differentially modulate brain glucose and ketone body metabolism: implications for Alzheimer’s disease risk reduction and early intervention. J. Neurosci. 38, 6665–6681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rettberg J. R., Dang H., Hodis H. N., Henderson V. W., St. John J. A., Mack W. J., Brinton R. D. (2016) Identifying postmenopausal women at risk for cognitive decline within a healthy cohort using a panel of clinical metabolic indicators: potential for detecting an at-Alzheimer’s risk metabolic phenotype. Neurobiol. Aging 40, 155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karim R., Koc M., Rettberg J. R., Hodis H. N., Henderson V. W., St John J. A., Allayee H., Brinton R. D., Mack W. J. (2018) Apolipoprotein E4 genotype in combination with poor metabolic profile is associated with reduced cognitive performance in healthy postmenopausal women: implications for late onset Alzheimer’s disease. July 2 [E-pub ahead of print]. Menopause [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peila R., Rodriguez B. L., Launer L. J.; Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (2002) Type 2 diabetes, APOE gene, and the risk for dementia and related pathologies: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes 51, 1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghebranious N., Mukesh B., Giampietro P. F., Glurich I., Mickel S. F., Waring S. C., McCarty C. A. (2011) A pilot study of gene/gene and gene/environment interactions in Alzheimer disease. Clin. Med. Res. 9, 17–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuusisto J., Koivisto K., Mykkänen L., Helkala E. L., Vanhanen M., Hänninen T., Kervinen K., Kesäniemi Y. A., Riekkinen P. J., Laakso M. (1997) Association between features of the insulin resistance syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease independently of apolipoprotein E4 phenotype: cross sectional population based study. BMJ 315, 1045–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Craft S., Asthana S., Schellenberg G., Cherrier M., Baker L. D., Newcomer J., Plymate S., Latendresse S., Petrova A., Raskind M., Peskind E., Lofgreen C., Grimwood K. (1999) Insulin metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease differs according to apolipoprotein E genotype and gender. Neuroendocrinology 70, 146–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Profenno L. A., Faraone S. V. (2008) Diabetes and overweight associate with non-APOE4 genotype in an Alzheimer’s disease population. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 147B, 822–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanson A. J., Banks W. A., Hernandez Saucedo H., Craft S. (2016) Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex influence glucose tolerance in older adults: a cross-sectional study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 6, 78–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris J. K., Vidoni E. D., Wilkins H. M., Archer A. E., Burns N. C., Karcher R. T., Graves R. S., Swerdlow R. H., Thyfault J. P., Burns J. M. (2016) Impaired fasting glucose is associated with increased regional cerebral amyloid. Neurobiol. Aging 44, 138–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliveira B. C. L., Bellozi P. M. Q., Reis H. J., de Oliveira A. C. P. (2018) Inflammation as a possible link between dyslipidemia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 376, 127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holmes C. (2013) Review: systemic inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 39, 51–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mraz M., Haluzik M. (2014) The role of adipose tissue immune cells in obesity and low-grade inflammation. J. Endocrinol. 222, R113–R127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller A. A., Spencer S. J. (2014) Obesity and neuroinflammation: a pathway to cognitive impairment. Brain Behav. Immun. 42, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christensen A., Pike C. J. (2015) Menopause, obesity and inflammation: interactive risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tai L. M., Ghura S., Koster K. P., Liakaite V., Maienschein-Cline M., Kanabar P., Collins N., Ben-Aissa M., Lei A. Z., Bahroos N., Green S. J., Hendrickson B., Van Eldik L. J., LaDu M. J. (2015) APOE-modulated Aβ-induced neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: current landscape, novel data, and future perspective. J. Neurochem. 133, 465–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pike C. J. (2017) Sex and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 671–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dufouil C., Seshadri S., Chêne G. (2014) Cardiovascular risk profile in women and dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 42(s4, Suppl 4)S353–S363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hayden K. M., Zandi P. P., Lyketsos C. G., Khachaturian A. S., Bastian L. A., Charoonruk G., Tschanz J. T., Norton M. C., Pieper C. F., Munger R. G., Breitner J. C. S., Welsh-Bohmer K. A.; Cache County Investigators (2006) Vascular risk factors for incident Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: the Cache County study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 20, 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tai L. M., Balu D., Avila-Munoz E., Abdullah L., Thomas R., Collins N., Valencia-Olvera A. C., LaDu M. J. (2017) EFAD transgenic mice as a human APOE relevant preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Lipid Res. 58, 1733–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barron A. M., Garcia-Segura L. M., Caruso D., Jayaraman A., Lee J.-W., Melcangi R. C., Pike C. J. (2013) Ligand for translocator protein reverses pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 33, 8891–8897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cacciottolo M., Wang X., Driscoll I., Woodward N., Saffari A., Reyes J., Serre M. L., Vizuete W., Sioutas C., Morgan T. E., Gatz M., Chui H. C., Shumaker S. A., Resnick S. M., Espeland M. A., Finch C. E., Chen J. C. (2017) Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trumble B. C., Stieglitz J., Blackwell A. D., Allayee H., Beheim B., Finch C. E., Gurven M., Kaplan H. (2017) Apolipoprotein E4 is associated with improved cognitive function in Amazonian forager-horticulturalists with a high parasite burden. FASEB J. 31, 1508–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]