Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a leading cause of dementia. However, the mechanisms responsible for development of AD, especially for the sporadic variant, are still not clear. In our previous study, we discovered that a small noncoding RNA (miR-188-3p) targeting β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme (BACE)-1, a key enzyme responsible for Aβ formation, plays an important role in the development of neuropathology in AD. In the present study, we identified that miR-338-5p, a new miRNA that also targets BACE1, contributes to AD neuropathology. We observed that expression of miR-338-5p was significantly down-regulated in the hippocampus of patients with AD and 5XFAD transgenic (TG) mice, an animal model of AD. Overexpression of miR-338-5p in the hippocampus of TG mice reduced BACE1 expression, Aβ formation, and neuroinflammation. Overexpression of miR-338-5p functionally prevented impairments in long-term synaptic plasticity, learning ability, and memory retention in TG mice. In addition, we provide evidence that down-regulated expression of miR-338-5p in AD is regulated through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Our results suggest that down-regulated expression of miR-338-5p plays an important role in the development of AD.—Qian, Q., Zhang, J., He, F.-P., Bao, W.-X., Zheng, T.-T., Zhou, D.-M., Pan, H.-Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, X.-Q., He, X., Sun, B.-G., Luo, B.-Y., Chen, C., Peng, G.-P. Down-regulated expression of microRNA-338-5p contributes to neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: BACE1, neuroinflammation, NF-κB, noncoding small RNA, epigenetics

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is clinically characterized by loss of memory, progressive impairment of cognition and living activities, and various neuropsychiatric disturbances. Pathologically, AD exhibits deposits of amyloid β (Aβ) as senile plaques (SPs), hyperphosphorylated aggregated tau protein as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and neurodegeneration. As a leading cause of dementia in the elderly, AD has become a common health concern. However, until recently, no effective treatments have been available to prevent development of AD or to delay progression of the disease, largely because of our limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying the neuropathogenesis of AD.

microRNAs (miRs), small noncoding RNAs (∼20–23 nt), are post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression by binding to (3′ UTR) of the targets (1). Because of their relatively small binding sequences, a single miR can interact with multiple downstream mRNAs, whereas a single mRNA can be regulated by several miRs, which enables a single miR to convey robustness to an entire gene network with shared physiologic roles (2–5). Thus, miRs represent a particularly vital group of gene network regulators. Growing evidence indicates that many miRs are specifically expressed or enriched in the brain. In particular, several miRs have been shown to regulate neurodevelopmental aspects, including neurogenesis (6), neuronal migration (7), axon and dendrite development (8–10), ultimate synapse formation (11, 12), and neuronal plasticity (13, 14). Previous studies also provide evidence that even slight aberrations in miR expression levels or activity can be detrimental to brain function (15–18). Thus, discovery of miRs provides a new perspective to study the pathogenesis and neuropathology of AD, which prompts scientists to search the relationship between miRs and AD. Indeed, several miRs have been found to be up- or down-regulated, in patients with AD and animal models, suggesting that miRs are involved in AD pathogenesis (19–23).

Previous studies have identified several miRs that target BACE1, a key enzyme responsible for Aβ formation (20–24), but only a few studies have been conducted to determine whether restoration or reversal of dysregulated miRs targeting BACE1 is capable of reducing Aβ production, which in turn, alleviates neuropathology of AD (23, 25, 26). In our previous miR microarray screening, we identified several deregulated miRs in the hippocampus of 5XFAD transgenic (TG) mice, a mouse model of AD (25). In the present study, we defined the role of miR-338-5p, a robustly deregulated miR, in the development of AD neuropathology in 5XFAD TG mice. Our results showed that expression of miR-338-5p, which represses BACE1 by functionally binding to its 3′UTR, was significantly down-regulated in the hippocampi of patients with AD and TG mice. Overexpression of miR-338-5p in the hippocampi of TG mice significantly reduced Aβ formation and deposition and neuroinflammation and improved synaptic and cognitive function, suggesting that down-regulated miR-338-5p plays an important role in the pathogenesis and neuropathology of AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA], and the care and use of the animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. 5XFAD transgenic (TG) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (006554; Bar Harbor, ME, USA) (27) and maintained by crossing hemizygous transgenic mice with B6SJL F1 mice. The genotype of the mice was identified by PCR with genomic DNA from mouse tails. The age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates were used as controls in all the experiments. All these animals were maintained in constant environmental conditions (temperature, 23 ± 2°C; humidity, 55 ± 5%; and 12:12-h light–dark cycle with food and water ad libitum). In the present study, 135 male TG and 78 male age-matched WT littermates, 4–9 mo of age, were used.

Human brain tissues

Human hippocampal samples from patients with AD and normal controls were provided by the NIH NeuroBiobank/Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA). These postmortem human hippocampal tissues were from normal controls at 82.0 ± 3.1 yr of age and from patients with AD at 80.5 ± 2.7 yr of age, with the mean postmortem interval 7.4 ± 1.4 and 6.6 ± 1.0 h, respectively.

All the AD cases were in the moderate-to-advanced stages. The use of human tissues samples was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Primary hippocampal neuron culture

Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared from mouse pups [postnatal d 0 (P0) to P1], as previously described (28, 29), and were analyzed between 10 and 15 d in vitro (DIV). BACE1 expression was analyzed in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with lentiviral vectors expressing scramble control or miR-338-5p. Imaging was taken 72 h after transfection.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Expression of miRs in the hippocampus was profiled using Mir-X miR Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Sybr Kit (638314; Takara, Tokyo, Japan) in 5XFAD TG and WT mice, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, total RNA was harvested with Trizol reagent (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), according to a standard guanidinium-phenol-chloroform extraction procedure. RNA quantity and purity were assessed with a Nanodrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and RNA integrity was assessed on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All samples had acceptable A260/A280 ratios and RNA integrity numbers >8.5. One microgram RNA was further reverse transcribed into cDNA (Mir-X miR First-Strand Synthesis Kit; Takara) for qPCR in the presence of a fluorescent dye (Sybr Advantage Premix; Takara). U6 was used as a reference gene for normalization. The miR-338-5p-specific primer used for qPCR is as follows: 5′-AACAATATCCTGGTGCTGAGTG-3′.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis

To determine the binding of NF-κB p65 in the promoter region of the miR-338-5p gene, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MilliporeSigma). In brief, the potential binding site (BS) of NF-κB in the promoter region of miR-338-5p was identified with the Genome Browser (University of California–Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; http://genome-asia.ucsc.edu). Precleared chromatin was incubated with the NF-κB p65 antibody (1:1000, 8242P; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or normal mouse IgG (MilliporeSigma) antibodies (control) overnight at 4°C. Purified DNA from the samples and the input controls were analyzed for the presence of miR-338-5p promoter sequences containing putative NF-κB response elements by using qPCR. The primers for ChIP are as follows: 5′-CACACCCCCTTTCTGCAGG-3′ and 5′-CACCTGTGCACGAAATTGTTG-3′ for BS1 and 5′-GTCCACTCCCGCAGGG-3′ and 5′-ACCAGTGGGCAGAACTCCAT-3′ for BS2.

Plasmid and lentiviral constructs

To predict the possible miRs targets, we used the TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), microRNA.org (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) and mirbase.org (http://www.mirbase.org) databases. One BS of miR-338-5p in the 3′UTR of BACE1 (nt 949–956) was computationally predicted. The sequences of premiR-338-5p were cloned into the miRSelect pEGP expression vector (Cell Biolab, San Diego, CA, USA), and the sequences of the 3′UTR of mouse BACE1 [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Accession No. BC048189] were amplified by PCR and cloned into the psiCheck vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For the luciferase activity assay, we made mutations in the BS sequences in the 3′UTR of BACE1, which were computationally predicted to be recognized by the seed region of miR-338-5p. The sequences of all constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. FUGW lentivirus (LV) was generated and packaged by Shanghai Genechem (Shanghai, China). A titer of the LV of at least 1.0 × 109 infection functional units per milliliter was used for in vivo injections.

Luciferase activity assay

To validate the recognition of miR-338-5p in the 3′UTR of BACE1, we cotransfected the luciferase reporter vector expressing 3′UTR of BACE1, or mutated BS in the 3′UTR of BACE1 with the pEGP vector expressing premiR-338 in HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cells were prepared and transfected as previously described (30). In brief, cells were grown to ∼70% confluence and transfected with 500 ng plasmid DNA on a well of a 24-well plate. Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then luciferase activities were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System; Promega). The reporter activity (light units) was detected with a microplate luminometer. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase and expressed as a percentage of the control.

Stereotaxic injection

Four-month-old WT or TG mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotactic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Two microliters LV-expressing scrambled control (LV-control) or miR-338-5p (LV-miR-338-5p) was injected (at a rate of 0.1 μl/min) into both sides in the dentate gyrus area (at the coordinate relative to the bregma: anteroposterior, −2.1 mm; mediolateral, ±1.7 mm; and dorsoventral, −2.1 mm) via a Hamilton 701 RN Syringe equipped with a Kd Scientific Adapter and a blunt-ended 30-gauge needle (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA). After completing the procedure, mice were placed on a 37°C electric blanket until they were revived. Electrophysiological recordings and behavioral tests were performed, and most brain samples were collected 8 wk after LV injections.

Immunoblot analysis

Hippocampal tissue or cell lysates were extracted and immediately homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Triton-X-100) and protease inhibitors (PMSF, 329-98-6; Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and cocktail] and incubated on ice for 30 min, then centrifuged for 30 min at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. To extract the cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, a Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Extraction Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After proteins were extracted, the concentration was determined with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Supernatants were boiled and then equally fractionated on 8–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membrane was incubated with the following: anti-BACE1 (1:3000, ab108394; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1000, 8242P; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-hAPP (1:1000, 6E10; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-glial fibrillay acidic protein (GFAP; 1:2000, Z0334; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), anti-ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule (Iba)-1 (1:1000, ab107159; Abcam), anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP; 1:1000, sc-9996; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:5000; 5174S; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-histone [H3] (1:1000, ab32356; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Blots were probed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h and developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to visualize protein bands. The signals were detected with X-ray films. The densitometry measurements of the bands were quantified by Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry and quantitation of immunoreactive structures

Every 10 free-floating brain section (30 μm/section) was washed with Tris-buffered saline, blocked with blocking buffer (10% serum, 1% nonfat milk, and 0.2% gelatin in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100). They were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 or 2 of the following antibodies: anti-Aβ42 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-GFP (1:1000, 44-344, sc9996; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-hAPP (1:1000, 6E10; BioLegend), anti-Aβ (17–24) (1:1000, 4G8; BioLegend), anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1000, catalog 8242P; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GFAP (1:1000, G3893; MilliporeSigma), anti-Iba-1 (1:3000, 019–19741; Fujifilm Wako, Osaka, Japan), and anti-BACE1 (1:500, ab108394; Abcam); incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature; washed with PBS; and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (H-1200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Digitized images were obtained with a BX-53 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY, USA). Quantifications of Aβ plaque loads in the hippocampus were performed as described with minor modifications (31, 32). Experimenters were blind to the genotypes of the mice for all immunohistochemical analyses. Total plaque load was calculated as the percent area of the hippocampus covered by 4G8, 6E10, or Aβ42-immunoreactive material. Four coronal sections per mouse were analyzed with ImageJ (NIH) software, and the average of the individual measurements was used to calculate group means.

Aβ42 ELISA

Levels of Aβ42 in hippocampal tissues of TG mice that received control or miR-338-5p LVs were detected by using a colorimetric Aβ42 ELISA kit (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA). In brief, hippocampal samples were extracted and immediately homogenized in guanidine-HCl buffer [5 M guanidine HCl, 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) and protease inhibitor cocktail (aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A)] with PMSF. We added the diluted Aβ42 standards and samples to the wells and manipulated them according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hippocampal slice preparation and electrophysiological recordings

Acute hippocampal slices were prepared from 6-mo-old TG or WT mouse brains. After decapitation, brains were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold solution containing (mM) 234 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4·2H2O, 26 NaHCO3, and 11 d-glucose equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Horizontal brain slices (350 µm) containing the hippocampus were cut on a Vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) in the above solution and incubated for 0.5–1 h in oxygenated standard artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (mM: 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4·2H2O, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 d-glucose) at 34°C. The slices were maintained at room temperature (22°C–24°C) for 40–240 min before the recordings. An individual slice was then transferred to a submerged recording chamber perfused with ACSF equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 at a rate of 2–3 ml/min at 34°C.

The stimulating electrode was placed in the medial perforant path, and the recording electrode was placed in the same path, ∼300 μm away from the stimulating electrode. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded with glass electrodes (∼3 MΩ tip resistance) filled with ACSF and were evoked every 20 s with a bipolar tungsten electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME, USA) in the presence of 10 μM SR 95531 (Gabazine; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to block inhibitory transmission. Recordings were filtered at 2 kHz, digitally sampled at 20 kHz with a multiclamp 700B amplifier, and acquired with a Digidata-1440A digitizer and pClamp 10.2 software (all from Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Synaptic transmission strengths were assessed by generating input-output (I-O) curves for fEPSPs. Stimulus intensity was adjusted to ∼40% of the maximum fEPSP response. After a 20 min stable baseline was established, long-term potentiation (LTP) was induced by high-frequency stimulation (4 trains of 100-Hz stimuli, each having 100 pulses, at 100 Hz separated by 20 s). Then, average responses (means ± sem) were expressed as the percentage of basal fEPSP amplitude. Data were analyzed offline with pClamp10.2 software and Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Morris water maze

To determine spatial learning and memory, we conducted the Morris water maze test. Animals were 6-mo-old adult male mice (8 wk after LV injection). A circular water tank (110 cm in diameter) was filled with opaque water. A hidden circular platform (10 cm in diameter) was submerged 1.5 cm beneath the surface of the water. Before testing, mice were habituated to the testing room for 1 h. A visible pretraining (4 trials) session was conducted on the first day. If the mouse failed to find the platform above the water within the 90-s trial, it would be guided to the platform and allowed to stay on it for 15 s. Invisible platform trainings were performed for the following 5 d (4 sessions consisted of 4 trials each day). For each trial, the mouse was released from the wall of the tank and given a maximum of 60 s to find the hidden platform and stay on it for 15 s. If the mouse could not find the platform within 60 s, the training was terminated, and a maximum score of 60 s was assigned. For each training session, the starting quadrant was pseudorandomly chosen and counterbalanced across all experimental groups. The swimming paths, speed, and the time spent in each quadrant of the mice were recorded by video camera with Watermaze software (version 4.07; Actimetrics, Wilimette, IL). A probe test was conducted 24 h after the completion of the learning acquisition training. For the probe trial on the seventh day of training, the platform was removed from the pool, and the mouse was subjected to a single 120-s swim.

Preparation of Aβ42 oligomers

Synthetic human Aβ1–42 peptides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were prepared as described by Kim et al. (33). Aβ1–42 peptides were dissolved into 140 μl NH4OH and then sonicated for 30 s and diluted in 1× PBS to a final 100-μM concentration, for freshly prepared Aβ peptides (Mono-Aβ42). Next, these peptides were incubated at 22°C for 16 h and 4°C for 24 h, then centrifuged at 16,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected as oligomerized Aβ peptides (Oligo-Aβ42) and confirmed by Western blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as means ± sem. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 5. Student’s t test and a 1-way ANOVA were used to determine statistical significance. A 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc tests was used for the difference between I-O curves. Results of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

MiR-338-5p is down-regulated in the hippocampi of both patients with AD and TG mice

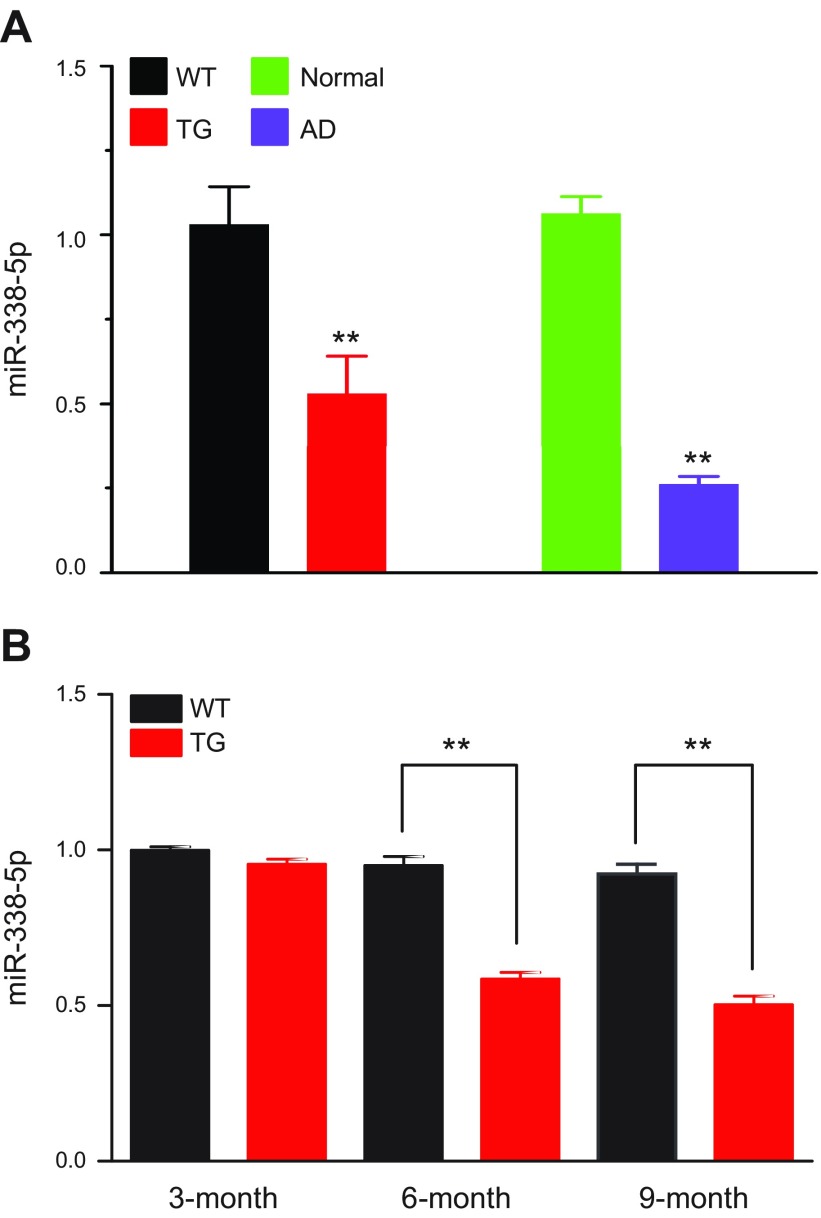

We observed that the expression of miR-338-5p in the hippocampi was significantly reduced in the 6-mo-old TG mice (Fig. 1A). To further identify whether the expression of miR-338-5p is changed in patients with AD, we measured miR-338-5p expression in hippocampal tissues from patients with AD and normal controls. The expression of miR-338-5p was also robustly down-regulated in the hippocampi of patients with AD when compared with the normal subjects. We observed that expression of miR-338-5p was reduced significantly in TG hippocampi in both the 6- and 9-mo-old groups, but not in the 3-mo-old group (Fig. 1B), suggesting that miR-338-5p is an important factor in the aging process.

Figure 1.

Expression of miR-338-5p is down-regulated in the hippocampi of patients with AD and TG mice. A) Expression of miR-338-5p is decreased in the hippocampi of both TG mice (WT: n = 8/group; TG: n = 9/group) and patients with AD (Normal subjects: n = 11/group; AD: n = 12/group) according to real-time qPCR analysis. Data are means ± sem. **P < 0.01, vs. WT or normal subjects. B) Real-time qPCR analysis of miR-338-5p expression in different age groups of TG mice. The miR-338-5p levels in other groups were all normalized to that in the 3-mo WT group: in the 3-mo-old group, n = 6 (WT) and n = 5 (TG); in the 6-mo-old group, n = 5 (WT) and n = 6 (TG); and in the 9-mo-old group, n = 6 (WT) and n = 8 (TG). Data are means ± sem. **P < 0.01.

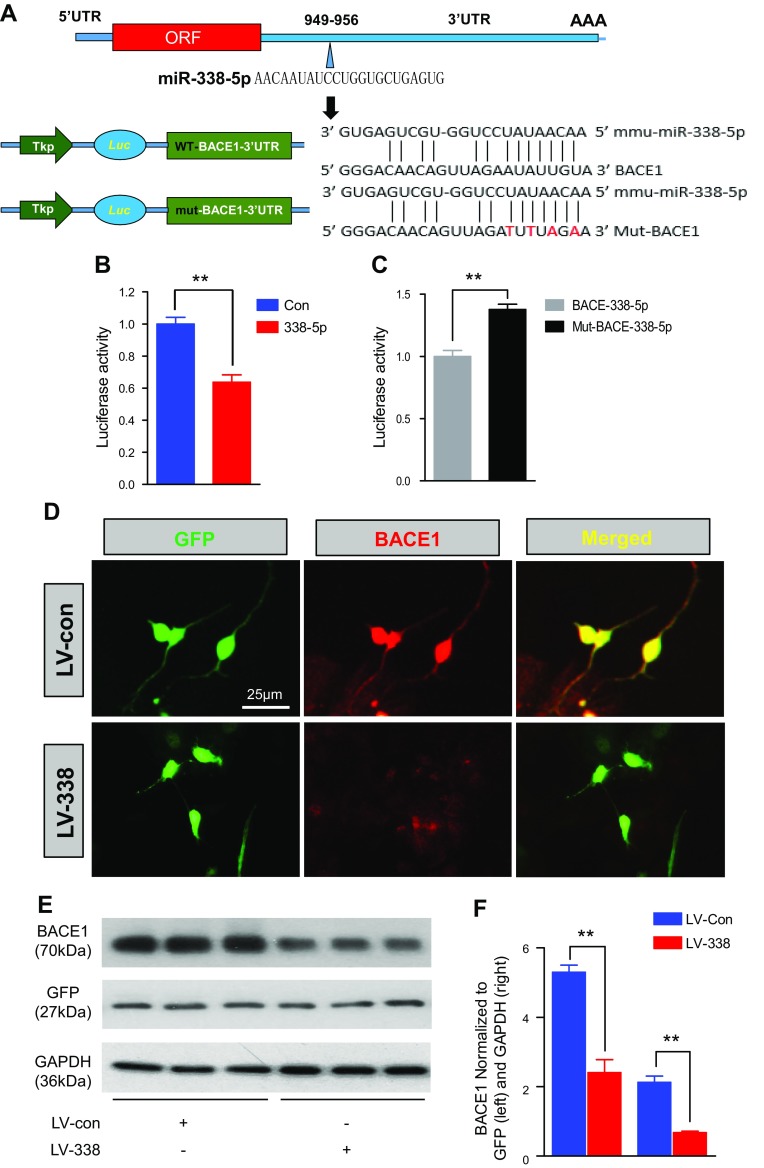

MiR-338-5p functionally binds to the 3′UTR of BACE1 and suppresses its expression

According to the computational prediction, miR-338-5p has a BS in the 3′UTR of BACE1 (Fig. 2A). To functionally validate the putative BS, we conducted the luciferase activity assay. The activity of the reporter vector cotransfected with the pEGP vector expressing premiR-338 was inhibited compared with the control vector (Fig. 2B). To further verify the binding activity, we mutated the BS sequences in the 3′UTR of BACE1 recognized by miR-338-5p. Mutation of the BS sequences resulted in a loss of the inhibition of the reporter activity (Fig. 2C), confirming that miR-338-5p functionally binds to the 3′UTR of BACE1.

Figure 2.

miR-338-5p functionally binds to the 3′UTR of BACE1 and suppresses its expression. A) Luciferase reporter construct (psiCHECK vector) of WT (normal) and mutated BS in the 3′UTR of BACE1 recognized by the seed region of miR-338-5p. B, C) Luciferase reporter activity in 293T cells cotransfecting the pEGP vector expressing premiR-338-5p with control (B) and BS-mutated reporter vectors (C); (B, n = 12; C, n = 7). Data are means ± sem. **P < 0.01, 1-way ANOVA with Fisher’s projected least significant difference (PLSD) test. D) Immunostaining analysis of BACE1 expression in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with LVs expressing scramble control or miR-338-5p. Imaging was taken 72 h after transfection. E, F) Immunoblot analysis (E) of BACE1 expression in hippocampal neurons transfected with LV expressing miR-338-5p. GAPDH and GFP (F) served as loading controls (n = 3). Data are means ± sem. **P < 0.01, vs. the scrambled control, by ANOVA with Fisher’s PLSD test.

Because miR-338-5p can functionally bind to the 3′UTR of BACE1 as shown in Fig. 2A–C, we predicated that miR-338-5p overexpression should suppress expression of BACE1. To this end, we generated LV-expressing miR-338-5p and induced overexpression of LV in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. As predicted, overexpression of miR-338-5p suppressed BACE1 expression, as confirmed by immunostaining and immunoblot analyses (Fig. 2D–F). These results indicate that miR-338-5p functionally targets BACE1, resulting in the suppression of BACE1 in vitro.

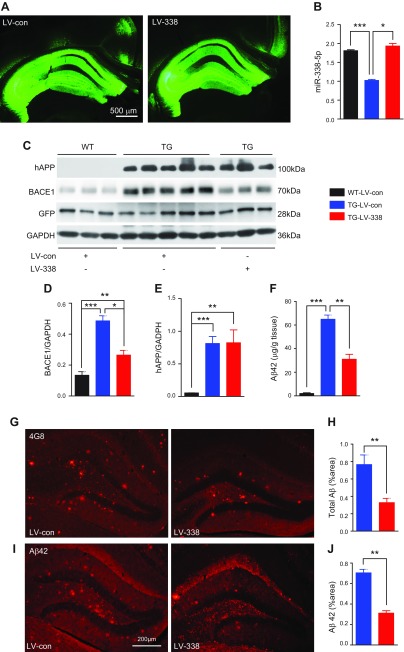

As reported by previous researchers (25, 34), 5XFAD mice exhibited much higher expression of BACE1. To further determine whether miR-338-5p suppresses BACE1 in vivo, we stereotaxically injected the LV-expressing miR-338p-5p into the hippocampus of 5XFAD mice. Both LV-expressing scrambled control (LV-con) and LV-expressing miR-338-5p (LV-miR-338-5p, LV-338) spread well in the hippocampal area 8 wk after injection (Fig. 3A). Injection of LV-miR-338 elevated expression of miR-338-5p in the hippocampus of the TG mice (Fig. 3B). We observed that overexpression of miR-338-5p by LV injection resulted in a significant reduction of BACE1 expression in the hippocampi compared with TG mice that received LV-con injections (Fig. 3C, D). The above from both in vitro and in vivo studies confirm that miR-338-5p functionally suppresses BACE1 expression.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of miR-338-5p decreases Aβ formation and accumulation in TG mice. A) Hippocampal expression of GFP after LV stereotaxic injection. Images were obtained 2 mo after the injection. B) Real-time qPCR analysis of miR-338-5p expression in the hippocampus 2 mo after LV injection (WT-LV-con, TG-LV-con, n = 6; TG-LV-338, n = 4). C–E) Immunoblot analysis of BACE1 (D) and hAPP (E) in the hippocampi of mice at 6 mo of age injected with LV-con or LV-miR-338-5p for 8 wk. GAPDH served as a loading control (n = 5/group). G, H) Total Aβ (all forms) detected by anti-4G8 antibody in the hippocampus of 6-mo-old TG mice that received LV-con or LV-miR-338-5p at 4 mo of age. n = 7 for TG-LV-con and n = 6 for TG-LV-338. F, I, J) Aβ42 was reduced in the hippocampus of TG mice that received LV-miR-338-5p using immunostaining (I, J) and ELISA (F). For immunostained sections n = 7 (TG-LV-con) and n = 6 (TG-LV-338). In ELISA, n = 8 (WT-LV-con), n = 17 (TG-LV-con) and n = 14 (TG-LV-338). Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Overexpression of miR-338-5p decreases Aβ formation and accumulation in TG mice

BACE1 is a key rate-limiting enzyme in the process of Aβ production and AD pathologic cascade (35–37). To determine whether overexpression of miR-338-5p would functionally repress BACE1 and further reduce Aβ production and deposition in TG mice, we detected BACE1, human amyloid precursor protein (hAPP), Aβ42, and plaque loads in TG animals injected with LV-con and -miR-338-5p at the age of 6 mo. BACE1 expression was significantly reduced in TG animals treated with LV-miR-338-5p, whereas hAPP did not change notably between these 2 TG groups (Fig. 3C–E). Total Aβ, and Aβ42, which is the final toxic product of hAPP, were significantly reduced in the hippocampi of TG mice injected with LV-expressing miR-338-5p by ELISA analyses and immunostaining (Fig. 3F–J and Supplemental Fig. S2). These results suggest that overexpression of miR-338-5p reduces Aβ formation and that accumulation is suppressed by repression of BACE1 in TG mice.

Overexpression of miR-338-5p reduces neuroinflammation in TG mice

Neuroinflammation, which is closely associated with increased Aβ deposits in AD, plays a critical role in development of AD neuropathology and synaptic and cognitive decline (38). miR-338-5p overexpression decreases Aβ formation in TG mice (Fig. 3). Thus, we hypothesized that overexpression of miR-338-5p would ameliorate neuroinflammation in TG mice. To test this prediction, we assessed reactive astrocytes by GFAP immunoreactivity and microglia by Iba1 immunoreactivity in TG mice injected with LV-miR-338-5p. miR-338-5p overexpression significantly reduced expression of GFAP and Iba1 in the hippocampus by immunostaining and immunoblot analyses, indicating that overexpression of miR-338-5p attenuates neuroinflammation by decreasing Aβ formation in TG mice (Fig. 4A–H).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of miR-338-5p decreases gliosis and improves basal synaptic transmission and LTP. A, C) Hippocampal GFAP (astrocytic marker) expression was suppressed by miR-338-5p. LV-control or miR-338-5p was injected into the hippocampi of mice at 4 mo of age, and immunostaining was conducted at 6 mo of age. Data are means ± sem (n = 8 mice/group). **P < 0.01, vs. the TG-LV-con group. B, D) Immunoblot analysis of GFAP expression (n = 4). E, G) Expression of Iba-1 (microglial marker) was suppressed by miR-338-5p overexpression (n = 8 mice/group). Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05 vs. the TG-LV-con group. F, H) Immunoblot analysis of Iba-1 expression (n = 5). I) I-O function recorded at hippocampal perforant synapses in 6-mo-old WT and TG mice injected with LV-con or LV-miR-338-5p for 8 wk. Data are means ± sem (n = 7 recordings from 7 mice for WT-LV-Con group, 9 recordings from 8 mice for TG-LV-Con group, and 10 recordings from 8 mice for TG-LV-338 group). A 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple-comparison post hoc test was used to determine the difference between the I-O curves. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. J) LTP curves and means ± sem of fEPSP slope averaged from the last 15 min after high-frequency stimulation in 6-mo-old WT or TG mice injected with LV-con or LV-miR-338-5p for 8 wk (WT-LV-Con group, n = 14 from 10 mice; TG-LV-Con group, n = 12 from 8 mice; in TG-LV-338 group, n = 11 from 5 mice). Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Overexpression of miR-338-5p restores the synaptic dysfunction in TG mice

Increased Aβ and neuroinflammation are major pathogenic mechanisms leading to synaptic and cognitive deficits in AD. Pathologically increased Aβ may indirectly cause a partial block of NMDA receptors and shift the activation of NMDA receptor–dependent signaling cascades toward pathways involved in synaptic plasticity and synaptic loss (39–41), which is consistent with the fact that Aβ impairs LTP (42–44). As miR-338-5p overexpression reduced Aβ and gliosis, we predicted that miR-338-5p overexpression would rescue synaptic dysfunction in TG animals. Hippocampal basal synaptic transmission and LTP were significantly improved in TG mice treated with LV expressing miR-338-5p (Fig. 4I, J). The results indicate that overexpression of miR-338-5p prevents decline in hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity in TG mice.

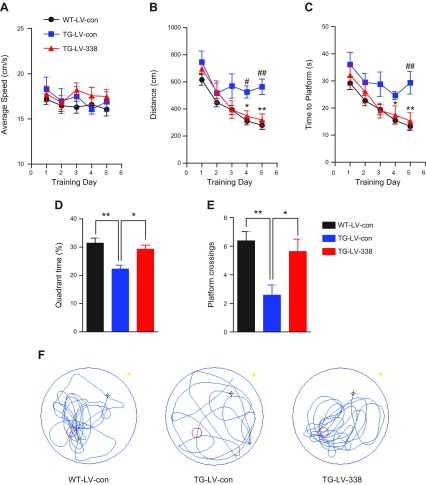

MiR-338-5p overexpression rescues cognitive deficits in TG mice

Impairments in learning and memory are the central problem in AD. To determine whether an increase in miR-338-5p expression is capable of preventing cognitive decline in TG mice, we conducted the Morris water maze test. All 3 groups of mice had similar body weights (data not shown) and swimming ability (Fig. 5A). TG mice receiving LV-miR-338-5p exhibited improved behavioral performance in learning acquisition (Fig. 5B, C). In the probe trial test on the last day, TG mice receiving LV-miR-338-5p spent much more time staying in the target quadrant and displayed an increased number of times crossing the platform when compared with those treated with LV-con (Fig. 5D–F), indicating that overexpression of miR-338-5p improves spatial memory in TG mice.

Figure 5.

miR-338-5p overexpression improves the cognitive function of TG mice. A–C) Spatial learning in TG mice is improved by overexpression of miR-338-5p. The Morris water maze test was performed in 6-mo-old mice that received LV injections for 8 wk. D–F) The probe trial test was conducted 24 h after 5 d of invisible training. Overexpression of miR-338-5p improved the spatial memory of 6-mo-old TG mice. Data are means ± sem (n = 13, TG-LV-338 group; n = 17, TG-LV-con group; n = 22, WT-LV-con group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the TG-LV-con. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. WT-LV-con.

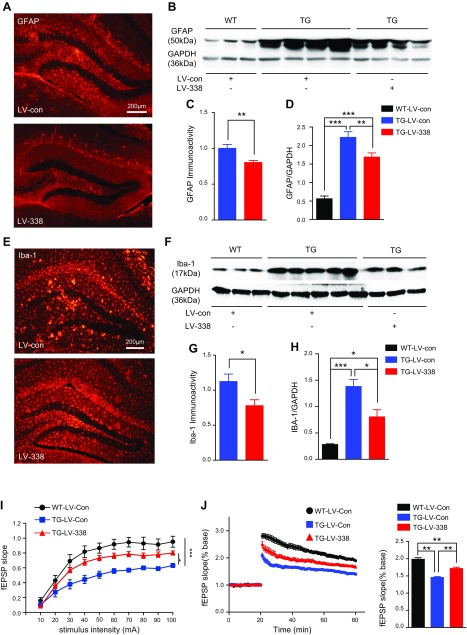

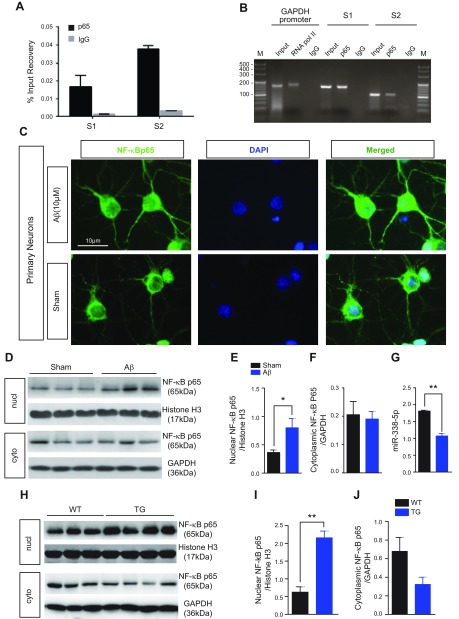

Expression miR-338-5p is regulated via NF-κB signaling

Although better known for its role in inflammation, NF-κB has more recently been implicated in learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity (45). We wondered whether NF-κB is involved in regulation of transcriptional process of miR-338-5p expression. We searched BSs of NF-κB p65 in the promoter region of the miR-338-5p gene through the Genome Browser and found that at least 2 NF-κB BSs were present in the promoter regions of the miR-338-5p gene. These BSs were further verified by both ChIP and qPCR analysis (Fig. 6A, B).

Figure 6.

NF-κB regulates miR-338-5p expression. A, B) Binding of the NF-κB p65 subunit in the promoter region of the miR-338-5p gene. ChIP analysis of promoter binding activity of NF-κB was analyzed. A 100-bp DNA ladder was used for the marker. S1 and S2 are BSs. C) Immunostaining of NF-κB p65 subunit expression in primary neurons treated with Aβ (10 µM) or HBSS (Sham). Aβ (10 µM) application activated NF-κB, presenting as nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65. D–F) Immunoblot analysis of NF-κB p65 subunit expression in primary neurons treated with Aβ (10 µM) or HBSS (Sham). Aβ (10 µM) application increased NF-κB p65 expression in the nuclear fraction. Histone [H3] served as the loading control for the nuclear fraction (nucl), and GAPDH was the control for the cytoplasmic fraction (cyto) (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05, compared with the sham-treated group. G) Expression of miR-338-5p is down-regulated in Aβ (10 µM) group using qRT-PCR analysis (n = 6/group). **P < 0.01, compared with the sham-treated group. H–J) Immunoblot analysis of NF-κB p65 in the hippocampi of mice at 6 mo of age. Histone [H3] served as the loading control for the nuclear fraction (nucl), and GAPDH was the control for the cytoplasmic fraction (cyto) [n = 3 (WT) and 4 (TG)]. Data are means ± sem. **P < 0.01, compared with the WT.

Increased NF-κB activity is associated with inflammatory and pathologic states of AD. In rat cortical and hippocampal cultured neurons, Aβ oligomer application activated NF-κB (Fig. 6C), as was indicated by translocation of a p65 NF-κB subunit into the nuclear fraction, which was further identified by Western blot (Fig. 6D–F). In particular, we measured the expression of miR-338-5p to observe whether it altered as the translocation of p65 NF-κB subunit. As expected, the expression of miR-338-5p was reduced in Aβ oligomer–treated neurons, in which the translocation of p65 NF-κB subunit occurred (Fig. 6G). Then, we used the lysates of hippocampal tissues from 6-mo-old TG to determine whether NF-κB is involved and activated in this AD animal models. The results observed in vivo were similar to those in cultured neurons in vitro (Figs. 1D and 6H–J), suggesting that miR-338-5p is regulated through NF-kB signaling.

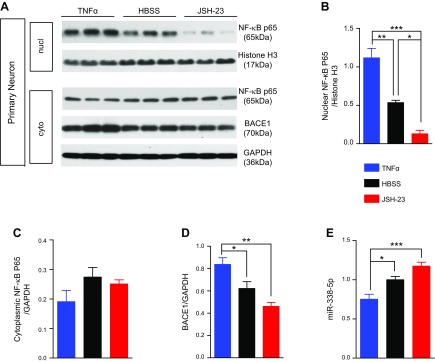

We inferred from Fig. 6 that Aβ stimulation would promote the translocation of NF-κB p65 subunit, which further binds to the promoter regions of miR-338-5p gene to reduce its expression. To further verify our prediction, we applied TNF-α (an effective activator of NF-κB) and 4-methyl-N1-(3-phenylpropyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (JSH-23) (a selective inhibitor of NF-κB) in cultured cortical and hippocampal neurons. TNF-α and JSH-23 increased and decreased NF-κB, respectively, in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 7A–C). As expected, TNF-α, the activator of NF-κB, efficiently inhibited expression of miR-338-5p and increased expression of BACE1 (Fig. 7D, E), further confirming that expression of miR-338-5p is regulated by NF-κB signaling.

Figure 7.

Expression of miR-338-5p is regulated by NF-κB signaling. A) Immunoblot analysis of NF-κB p65 and BACE1 in primary neurons treated with TNF-α (50 ng/L), HBSS (Sham), or JSH-23 (10 µM). Histone [H3] served as the loading control for nuclear fraction and GAPDH for cytoplasmic fraction. B) Quantification of NF-κB p65 from nuclear fraction (nucl). C) Quantification of NF-κB p65 from cytoplasmic fraction (cyto). D) Quantification of BACE1 from cytoplasmic fraction. Data are means ± sem (n = 6/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. E) Real-time qPCR analysis of miR-338-5p expression in primary neurons treated with TNF-α (50 ng/L), HBSS (sham), or JSH-23 (10 µM). Values are normalized to the HBSS controls (n = 6/group). Data are means ± sem. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, expression of miR-338-5p was robustly down-regulated in the hippocampi of patients with AD and TG mice. miR-338-5p overexpression significantly reduced BACE1 expression, Aβ formation, and neuroinflammation and prevented deficits in synaptic plasticity, spatial learning and memory in TG animals. Expression of miR-338-5p was found to be regulated by NF-κB signaling. Our results suggest that miR-338-5p, which targets BACE1, plays an important role in development of AD neuropathology.

BACE1 is a key enzyme in APP processing and Aβ production. It has been reported that expressions of several miRs are abnormal in patients with AD and animal models. Recent studies have provided evidence that miRs are most likely involved in Aβ production and AD neuropathology by targeting BACE1 (21, 24, 25, 46–48). However, it is still not clear whether undefined miRs that target BACE1 contribute to the development of AD neuropathology. In particular, only a few studies have been conducted to determine whether a reversal of miR(s) targeting BACE1 alleviates AD neuropathology in vivo (23, 25, 26). Our previous study demonstrated that overexpression of miR-188-3p, which also targets BACE1, ameliorates neuropathology and improves synaptic function in 5XFAD TG mice (25). In our miR microarray screening, we found that expression of miR-338-5p was down-regulated in TG mice. Indeed, our present study, expression of miR-338-5p was robustly reduced in the hippocampi of both TG mice and patients with AD. This miR also targets BACE1, which has not been recognized, suggesting that down-regulated expression of miR-338-5p is an important mechanism contributing to pathogenesis of AD. Indeed, stereotaxic injection of LV overexpressing miR-338-5p in the hippocampus results in alleviation of neuropathology and improvement in synaptic and cognitive function in TG mice. Our results provide evidence that changes in a single BACE1-targeted miR in the brain are sufficiently to trigger or curtail a cascade of AD pathogenesis.

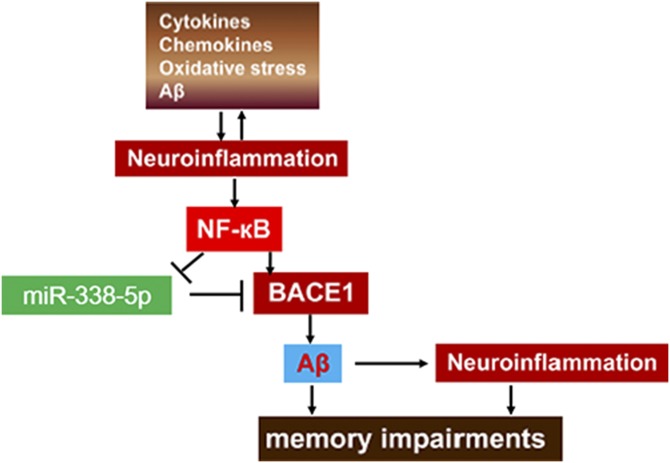

The transcription factor NF-κB, although initially recognized as a critical regulator of immune and inflammatory responses (49), has revealed its indispensable role in synaptic transmission, spatial memory formation, and plasticity in the normal brain (50). Multiple studies subsequently have confirmed that NF-κB has an expansive network of gene targets and is dysregulated in AD (45, 51). In early AD, NF-κB is activated in the neural and glial cells, with subsequent protective or detrimental effects (52–54). However, in advanced AD, NF-κB is persistently activated, which leads to axonal and neuronal injury, and finally neurodegeneration (55–58). In the present study, NF-κB translocation occurred in Aβ oligomer-treated cultured neurons or TG mouse brains, which is consistent with the results of others (51). We further identified that NF-κB has 2 BSs in the promoter region of the miR-338-5p gene, which could functionally down-regulate its expression, suggesting that NF-κB signaling regulates transcription and expression of miR-338-5p. Given the more recently identified roles for NF-κB and its miR targets in AD (59–61), a thorough understanding of the networks among them is warranted and may have important implications for uncovering the new treatments for AD (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Signaling pathways mediating the detrimental effects produced by neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation promotes activating NF-κB, which in turn enforces the inhibitory effect of NF-κB on miR-338-5p transcription. Decreased miR-338-5p expression promotes BACE1 and leads to an increase in Aβ formation, which in turn intensifies neuroinflammation and worsens synaptic and cognitive function.

Overall, the results of the present study provided evidence that overexpression of miR-338-5p in 5XFAD TG mice ameliorates neuropathology of AD by suppressing BACE1 expression, which in turn reduces Aβ formation and neuroinflammation and prevents deficits in synaptic and cognitive function. Given that miR-based therapies hold great promise for clinical applications (62–64), the results suggest that restoring expression of miR-338-5p by direct delivery of the vector expressing miR-338-5p would be a novel intervention for treatment of AD.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Xiaodong Wang for suggestions on data analysis and for providing some of the reagents, and Dr. Sanhua Fang and Qiaoling Ding (all from Zhejiang University School of Medicine) for help with the experimental process. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (81471284, to G.-P.P.), U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants (R01NS076815 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and R01AG058621 from the National Institute on Aging, to C.C.), the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1306402, to B.-Y.L.), and the Research fund of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2018ZR04 to Q.Q.). C.C. and G.-P.P. conceived the study and designed the experiments as well as analyzed the data. Dr. Benyan Luo made constructive amendments to the project. Also, the majority of the experiments were performed in Dr. Luo’s laboratory. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Aβ

amyloid β

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- BACE

β-site amyloid precursor protein–cleaving enzyme

- BS

binding site

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DIV

day in vitro

- fEPSP

field excitatory post synaptic potential

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- hAPP

human amyloid precursor protein

- Iba

ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule

- I-O

input output

- JSH-23

4-methyl-N1-(3-phenylpropyl)benzene-1,2-diamine

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LV

lentivirus

- miR

microRNA

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangle

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- SP

senile plaque

- TG

transgenic

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Q. Qian, B.-Y. Luo, C. Chen, and G.-P. Peng conceived and designed the project; Q. Qian, J. Zhang, F.-P. He, W.-X. Bao, T.-T. Zheng, D.-M. Zhou, H.-Y. Pan, X.-Q. Zhang, and X. He performed the experiments; B.-Y. Luo made available the laboratory where the majority of the experiments were performed; Q. Qian and D.-M. Zhou processed the data; Q. Qian, D.-M. Zhou, C. Chen, and G.-P. Peng analyzed the data; B.-Y. Luo made constructive amendments to the project; Q. Qian, B.-Y. Luo, C. Chen, and G.-P. Peng wrote the manuscript with input from other authors; and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shukla G. C., Singh J., Barik S. (2011) MicroRNAs: processing, maturation, target recognition and regulatory functions. Mol. Cell. Pharmacol. 3, 83–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim L. P., Lau N. C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J. M., Castle J., Bartel D. P., Linsley P. S., Johnson J. M. (2005) Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stark A., Brennecke J., Bushati N., Russell R. B., Cohen S. M. (2005) Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3'UTR evolution. Cell 123, 1133–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X., Cassidy J. J., Reinke C. A., Fischboeck S., Carthew R. W. (2009) A microRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell 137, 273–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebert M. S., Sharp P. A. (2012) Roles for microRNAs in conferring robustness to biological processes. Cell 149, 515–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rago L., Beattie R., Taylor V., Winter J. (2014) miR379-410 cluster miRNAs regulate neurogenesis and neuronal migration by fine-tuning N-cadherin. EMBO J. 33, 906–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaughwin P., Ciesla M., Yang H., Lim B., Brundin P. (2011) Stage-specific modulation of cortical neuronal development by Mmu-miR-134. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1857–1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dajas-Bailador F., Bonev B., Garcez P., Stanley P., Guillemot F., Papalopulu N. (2012) microRNA-9 regulates axon extension and branching by targeting Map1b in mouse cortical neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 697–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smrt R. D., Szulwach K. E., Pfeiffer R. L., Li X., Guo W., Pathania M., Teng Z. Q., Luo Y., Peng J., Bordey A., Jin P., Zhao X. (2010) MicroRNA miR-137 regulates neuronal maturation by targeting ubiquitin ligase mind bomb-1. Stem Cells 28, 1060–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallès A., Martens G. J., De Weerd P., Poelmans G., Aschrafi A. (2014) MicroRNA-137 regulates a glucocorticoid receptor-dependent signalling network: implications for the etiology of schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 39, 312–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schratt G. M., Tuebing F., Nigh E. A., Kane C. G., Sabatini M. E., Kiebler M., Greenberg M. E. (2006) A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature 439, 283–289; erratum: 441, 902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G., Ling S. (2017) MiR-124 promotes newborn olfactory bulb neuron dendritic morphogenesis and spine density. J. Mol. Neurosci. 61, 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellios N., Sugihara H., Castro J., Banerjee A., Le C., Kumar A., Crawford B., Strathmann J., Tropea D., Levine S. S., Edbauer D., Sur M. (2011) miR-132, an experience-dependent microRNA, is essential for visual cortex plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1240–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K., Kim J. H., Kwon O. B., An K., Ryu J., Cho K., Suh Y. H., Kim H. S. (2012) An activity-regulated microRNA, miR-188, controls dendritic plasticity and synaptic transmission by downregulating neuropilin-2. J. Neurosci. 32, 5678–5687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Im H. I., Kenny P. J. (2012) MicroRNAs in neuronal function and dysfunction. Trends Neurosci. 35, 325–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beveridge N. J., Cairns M. J. (2012) MicroRNA dysregulation in schizophrenia. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins D. O., Jeffries C. D., Jarskog L. F., Thomson J. M., Woods K., Newman M. A., Parker J. S., Jin J., Hammond S. M. (2007) microRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Genome Biol. 8, R27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong J., Duncan C. E., Beveridge N. J., Webster M. J., Cairns M. J., Weickert C. S. (2013) Expression of NPAS3 in the human cortex and evidence of its posttranscriptional regulation by miR-17 during development, with implications for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 39, 396–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delay C., Mandemakers W., Hébert S. S. (2012) MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh J. (2012) Molecular network of microRNA targets in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Exp. Neurol. 235, 436–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schonrock N., Götz J. (2012) Decoding the non-coding RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 3543–3559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iranifar E., Seresht B. M., Momeni F., Fadaei E., Mehr M. H., Ebrahimi Z., Rahmati M., Kharazinejad E., Mirzaei H. (2018) Exosomes and microRNAs: new potential therapeutic candidates in Alzheimer disease therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miya Shaik M., Tamargo I. A., Abubakar M. B., Kamal M. A., Greig N. H., Gan S. H. (2018) The role of microRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease and their therapeutic potentials. Genes (Basel) 9, 174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long J. M., Ray B., Lahiri D. K. (2014) MicroRNA-339-5p down-regulates protein expression of β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) in human primary brain cultures and is reduced in brain tissue specimens of Alzheimer disease subjects. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5184–5198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Hu M., Teng Z., Tang Y. P., Chen C. (2014) Synaptic and cognitive improvements by inhibition of 2-AG metabolism are through upregulation of microRNA-188-3p in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 34, 14919–14933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee K., Kim H., An K., Kwon O. B., Park S., Cha J. H., Kim M. H., Lee Y., Kim J. H., Cho K., Kim H. S. (2016) Replenishment of microRNA-188-5p restores the synaptic and cognitive deficits in 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 34433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oakley H., Cole S. L., Logan S., Maus E., Shao P., Craft J., Guillozet-Bongaarts A., Ohno M., Disterhoft J., Van Eldik L., Berry R., Vassar R. (2006) Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 26, 10129–10140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen R., Zhang J., Fan N., Teng Z. Q., Wu Y., Yang H., Tang Y. P., Sun H., Song Y., Chen C. (2013) Δ9-THC-caused synaptic and memory impairments are mediated through COX-2 signaling. Cell 155, 1154–1165; erratum: 156, 618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sang N., Zhang J., Marcheselli V., Bazan N. G., Chen C. (2005) Postsynaptically synthesized prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) modulates hippocampal synaptic transmission via a presynaptic PGE2 EP2 receptor. J. Neurosci. 25, 9858–9870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ly P. T., Wu Y., Zou H., Wang R., Zhou W., Kinoshita A., Zhang M., Yang Y., Cai F., Woodgett J., Song W. (2013) Inhibition of GSK3β-mediated BACE1 expression reduces Alzheimer-associated phenotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 224–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palop J. J., Jones B., Kekonius L., Chin J., Yu G. Q., Raber J., Masliah E., Mucke L. (2003) Neuronal depletion of calcium-dependent proteins in the dentate gyrus is tightly linked to Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9572–9577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun B., Zhou Y., Halabisky B., Lo I., Cho S. H., Mueller-Steiner S., Devidze N., Wang X., Grubb A., Gan L. (2008) Cystatin C-cathepsin B axis regulates amyloid beta levels and associated neuronal deficits in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 60, 247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim T., Vidal G. S., Djurisic M., William C. M., Birnbaum M. E., Garcia K. C., Hyman B. T., Shatz C. J. (2013) Human LilrB2 is a β-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer’s model. Science 341, 1399–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao J., Fu Y., Yasvoina M., Shao P., Hitt B., O’Connor T., Logan S., Maus E., Citron M., Berry R., Binder L., Vassar R. (2007) Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 levels become elevated in neurons around amyloid plaques: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 27, 3639–3649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tesco G., Koh Y. H., Kang E. L., Cameron A. N., Das S., Sena-Esteves M., Hiltunen M., Yang S. H., Zhong Z., Shen Y., Simpkins J. W., Tanzi R. E. (2007) Depletion of GGA3 stabilizes BACE and enhances beta-secretase activity. Neuron 54, 721–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole S. L., Vassar R. (2008) BACE1 structure and function in health and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 100–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santosa C., Rasche S., Barakat A., Bellingham S. A., Ho M., Tan J., Hill A. F., Masters C. L., McLean C., Evin G. (2011) Decreased expression of GGA3 protein in Alzheimer’s disease frontal cortex and increased co-distribution of BACE with the amyloid precursor protein. Neurobiol. Dis. 43, 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shadfar S., Hwang C. J., Lim M. S., Choi D. Y., Hong J. T. (2015) Involvement of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory agents. Arch. Pharm. Res. 38, 2106–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamenetz F., Tomita T., Hsieh H., Seabrook G., Borchelt D., Iwatsubo T., Sisodia S., Malinow R. (2003) APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37, 925–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh H., Boehm J., Sato C., Iwatsubo T., Tomita T., Sisodia S., Malinow R. (2006) AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron 52, 831–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shankar G. M., Bloodgood B. L., Townsend M., Walsh D. M., Selkoe D. J., Sabatini B. L. (2007) Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 27, 2866–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S., Hong S., Shepardson N. E., Walsh D. M., Shankar G. M., Selkoe D. (2009) Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron 62, 788–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J. H., Anwyl R., Suh Y. H., Djamgoz M. B., Rowan M. J. (2001) Use-dependent effects of amyloidogenic fragments of (beta)-amyloid precursor protein on synaptic plasticity in rat hippocampus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 21, 1327–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palop J. J., Mucke L. (2010) Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 812–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snow W. M., Albensi B. C. (2016) Neuronal gene targets of NF-κB and their dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9, 118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boissonneault V., Plante I., Rivest S., Provost P. (2009) MicroRNA-298 and microRNA-328 regulate expression of mouse beta-amyloid precursor protein-converting enzyme 1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1971–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hébert S. S., Horré K., Nicolaï L., Papadopoulou A. S., Mandemakers W., Silahtaroglu A. N., Kauppinen S., Delacourte A., De Strooper B. (2008) Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6415–6420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang W. X., Rajeev B. W., Stromberg A. J., Ren N., Tang G., Huang Q., Rigoutsos I., Nelson P. T. (2008) The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J. Neurosci. 28, 1213–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta S. C., Sundaram C., Reuter S., Aggarwal B. B. (2010) Inhibiting NF-κB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 775–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaltschmidt B., Ndiaye D., Korte M., Pothion S., Arbibe L., Prüllage M., Pfeiffer J., Lindecke A., Staiger V., Israël A., Kaltschmidt C., Mémet S. (2006) NF-kappaB regulates spatial memory formation and synaptic plasticity through protein kinase A/CREB signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2936–2946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srinivasan M., Lahiri D. K. (2015) Significance of NF-κB as a pivotal therapeutic target in the neurodegenerative pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 19, 471–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pizzi M., Goffi F., Boroni F., Benarese M., Perkins S. E., Liou H. C., Spano P. (2002) Opposing roles for NF-kappa B/Rel factors p65 and c-Rel in the modulation of neuron survival elicited by glutamate and interleukin-1beta. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20717–20723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qin Z. H., Tao L. Y., Chen X. (2007) Dual roles of NF-kappaB in cell survival and implications of NF-kappaB inhibitors in neuroprotective therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 28, 1859–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaeffer V., Meyer L., Patte-Mensah C., Eckert A., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2008) Dose-dependent and sequence-sensitive effects of amyloid-beta peptide on neurosteroidogenesis in human neuroblastoma cells. Neurochem. Int. 52, 948–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sierra A., Abiega O., Shahraz A., Neumann H. (2013) Janus-faced microglia: beneficial and detrimental consequences of microglial phagocytosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7, 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattson M. P., Goodman Y., Luo H., Fu W., Furukawa K. (1997) Activation of NF-kappaB protects hippocampal neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis: evidence for induction of manganese superoxide dismutase and suppression of peroxynitrite production and protein tyrosine nitration. J. Neurosci. Res. 49, 681–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emmanouil M., Taoufik E., Tseveleki V., Vamvakas S. S., Probert L. (2011) A role for neuronal NF-κB in suppressing neuroinflammation and promoting neuroprotection in the CNS. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 691, 575–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed T., Gilani A. H. (2011) A comparative study of curcuminoids to measure their effect on inflammatory and apoptotic gene expression in an Aβ plus ibotenic acid-infused rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1400, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones S. V., Kounatidis I. (2017) Nuclear factor-kappa B and Alzheimer disease, unifying genetic and environmental risk factors from cell to humans. Front. Immunol. 8, 1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lukiw W. J. (2012) NF-κB-regulated, proinflammatory miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 4, 47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prasad K. N. (2017) Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines may act as one of the signals for regulating microRNAs expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 162, 63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Rooij E., Purcell A. L., Levin A. A. (2012) Developing microRNA therapeutics. Circ. Res. 110, 496–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hydbring P., Badalian-Very G. (2013) Clinical applications of microRNAs. F1000 Res. 2, 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y., Wang Z., Gemeinhart R. A. (2013) Progress in microRNA delivery. J. Control Release 172, 962–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.