Abstract

Initially discovered in Drosophila, the Hippo (Hpo) pathway has been recognized as a conserved signaling pathway that controls organ size during development by restricting cell growth and proliferation and by promoting apoptosis. In addition, abnormal activities of several Hpo pathway components have been implicated in human cancer. Here, we review the current understanding of the molecular and cellular basis of Hpo signaling in development and tumorigenesis, and discuss how the Hpo pathway integrates spatial and temporal signals to control tissue growth and organ size.

Different organs exhibit characteristic size, which is determined by the number and size of their constituent cells.1 How the organ size is controlled during animal development has been a fascinating problem in modern biology. The control of organ size depends on a delicate balance of cell proliferation and cell death, which are properly coordinated in response to both global and local stimuli. Although tissue growth is influenced by environmental factors such as hormonal signals and nutrients, organ-intrinsic mechanisms also play important roles. By genetic screen and characterization of mutants that cause tissue overgrowth in Drosophila, several signaling pathways, including the Hpo pathway, have been unraveled as organ intrinsic mechanisms that control organ size.2

Finding Hippo---an emerging size control pathway

The imaginal discs of Drosophila, which give rise to adult structures such as wings, legs, and eyes, provide an attractive system to study size control.3 Imaginal discs are specified during embryonic development but growth occurs at larval stages during which the number of cells of each disc increases exponentially. For example, a wing disc has less than 50 cells at the beginning of first instar; however, it contains over 50,000 cells at the end of third instar. Imaginal discs appear to possess intrinsic mechanisms to determine their final size and defects in these mechanisms result in overgrowth in a disc autonomous fashion.4, 5 In the past, tumor suppressor mutants were identified by genetic screens for mutations that either result in enlarged imaginal discs in homozygous late third instar larvae or cause overgrowth of imaginal disc derivatives in mosaic flies that carry clones of homozygous tissues in otherwise heterozygous background (Fig. 1).2, 6 In particular, genetic mosaic screens have led to the identification of a number of tumor suppressor genes, including warts/large tumor suppressor (wts/lats),7, 8 salvador (sav),9 hpo/dMST,10–14 that fall into an emerging tumor suppressor pathway, the so-called Hpo pathway (Fig. 2).

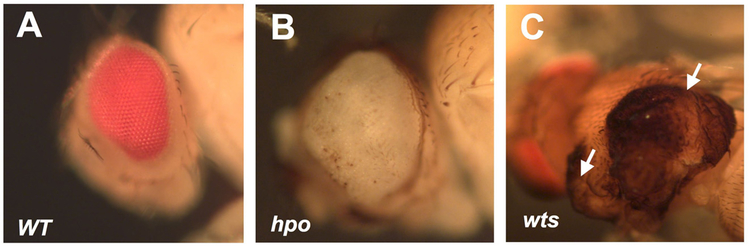

Figure 1. hop or wts mutant clones lead to tumor-like growth in mosaic flies.

Wild type eye (A) or enlarged eye carrying hpo mutant clones (B). wts mutant clones (arrows) located on the notum resulted in tumor-like growth (C). Adapted from Jia et al.10

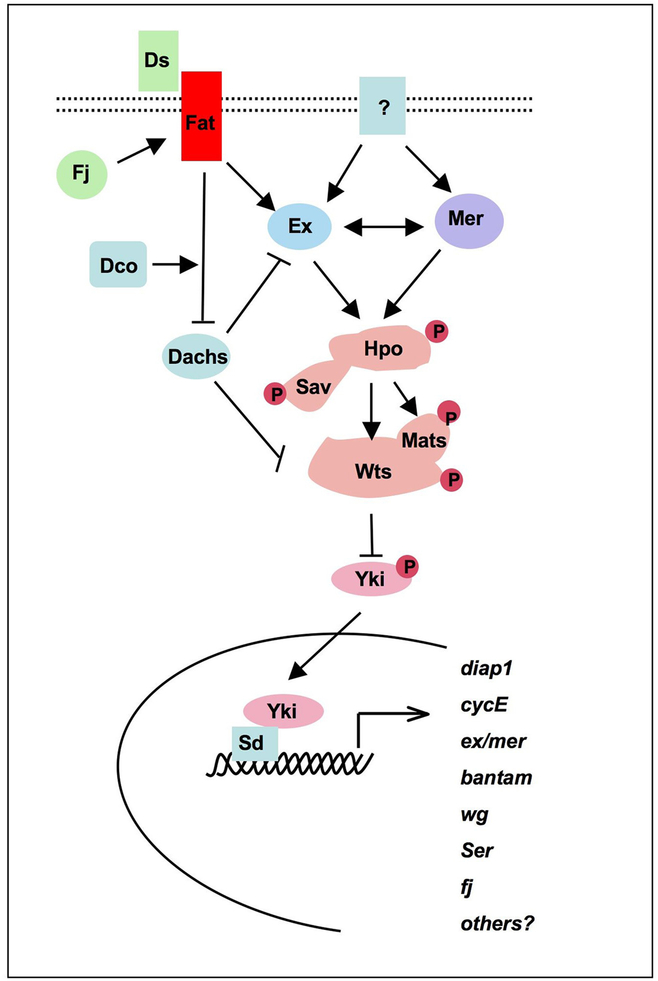

Figure 2. The Drosophila Hpo pathway.

The Hpo kinase cascade consists of four core proteins: Hpo, Sav, Wts, and Mats. Sav binds and regulates Hpo. Hpo phosphorylates and activates Wts. Hpo also phosphorylates Mats to enhance its ability to activate Wts. Wts phosphorylates Yki and restricts its nuclear localization. Yki forms a complex with Sd to activate Hpo target genes. Ex and Mer act in a partially redundant manner to regulate the Hpo kinase cascade. Fat is a candidate receptor and may regulate the Hpo pathway through Dachs and Ex. Ds is a candidate ligand for Fat. Fj modulates Ds/Fat interaction through phosphorylating Ds and Fat in the Golgi.

Central to the Hpo pathway is a kinase cascade consisting of four proteins including Hpo, Sav, Wts, and Mats (Fig.2). Hpo is the Drosophila homolog of mammalian Ste20 family kinases MST1 and MST2, and forms a complex with the WW-repeat scaffolding protein Sav to phosphorylate and activate the downstream kinase Wts, a member of the Nuclear Dbf-2-related (NDR) kinase family.7–14 Wts acts in association with a small regulatory protein called Mats (Mobs as tumor suppressor) to restrict cell growth and proliferation and promote cell death.15 Like Wts, Mats is phosphorylated by Hpo, which increases its association with Wts and its ability to upregulate Wts kinase activity.16, 17

Yki/Sd transcriptional complex mediates Hpo signaling

Hpo signaling pathway restricts cell growth and proliferation and promotes apoptosis mainly through transcriptional regulation of genes involved in these processes. Several transcriptional targets of the Hpo pathway have been identified, including cycE, diap1, and bantam, as well as two upstream Hpo pathway components: merlin (mer) and expanded (ex).9, 10, 13–15, 18–20 Hpo signaling influences gene expression by regulating Yorkie (Yki), the Drosophila homolog of mammalian transcriptional coactivator YAP, which binds to and is phosphorylated by Wts.21 Overexpression of Yki phenocopies loss of Hpo signaling activity, suggesting that Hpo signaling restricts cell growth and promotes cell death by inhibiting Yki-mediated gene expression.21 Indeed, Yki regulates all the known target genes of the Hpo pathway.19, 21

What is the DNA-binding transcription factor that associates with Yki to regulate Hpo pathway target genes? Three recent studies provided an answer by showing that the TEAD/TEF family transcription factor Scalloped (Sd) acts in a complex with Yki to promote the expression of Hpo pathway responsive genes.22–24 Overexpression of Sd enhances Hop target gene expression and tissue overgrowth caused by excessive Yki or tumor suppressor mutations in the Hpo pathway. Conversely, inactivation of Sd suppresses these effects. Moreover, a constitutively active form of Sd can promote tissue overgrowth as well as Hpo target gene expression.23 Characterization of diap1 enhancer elements suggests that Sd directly binds diap1 regulatory elements.22, 23 Sd promotes Yki nuclear localization23, 24 and recruits Yki to the diap1 promoter.23 On the other hand, phosphorylation of Yki at S168 by Wts restricts Yki nuclear localization.23, 25, 26 Thus, the Yki/Sd complex serves as a Hpo pathway transcriptional effector that is negatively regulated by Hpo signaling via phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of Yki (Fig.2).

Of note, loss of Sd has less severe phenotypes than loss of Yki.22, 23 For example, loss of Sd does not affect basal levels of diap1 expression but loss of Yki does. One possibility is that Yki can hook up with another transcription factor to regulate the basal expression of diap1. Alternatively, Sd may function as a default transcriptional repressor in the absence of Yki, as are the cases for the transcription factors of many signaling pathways.27 A prediction of the latter model is that removal of sd in yki mutant cells should restore diap1 expression.

Exploring upstream regulators of the Hpo pathway

While the regulatory events downstream of the Hpo kinase cascade have been relatively well-defined, the upstream regulatory mechanisms remain much less understood. Several studies suggested that the protocadherin Fat may function as a receptor for the Hpo pathway.28–31 fat was originally identified as a tumor suppressor gene whose mutations caused tumorous overgrowth of imaginal discs.32 fat mutant clones deregulated many Hpo target genes including cycE, diap1, and wg, and genetic epistasis study suggested that fat acts upstream of hpo, wts, and yki.28–31 Consistent with Fat acting upstream of Hpo signaling, overexpression of a truncated form of Fat (FatΔECD), which lacks the extra cellular domain and can suppress cell growth in vivo, induced Wts phosphorylation in cultured cells.31, 33 In addition, Wts levels diminished in fat mutant discs,29 and overexpression of Wts can rescue fat mutants to viability.34 Taken together, these observations suggest that Fat acts as a Hpo pathway receptor that regulates both Wts phosphorylation and turnover.

How Fat is linked to the Hpo kinase cascade is not clear but several proteins have been implicated as components acting downstream of Fat and upstream of Hpo. Two FERM domain containing proteins, Ex and Mer, were identified as partially redundant activators of Hpo.35 The mammalian orthologue of Mer is the product of tumor suppressor gene Neurofibromatosis type-2 (NF2), whose loss of function leads to the development of tumors in the central nervous system.36 In Drosophila, mer ex double mutant cells upregulate Hpo pathway target genes and deregulate both proliferation and apoptosis in a manner similar to hpo mutant cells, whereas mer or ex single mutant cells exhibit less severe phenotypes.35 Genetic and biochemical studies place Mer and Ex upstream of Hpo--overexpression of Hpo suppresses tissue overgrowth in mer ex double mutants and overexpression of Mer and Ex in S2 cells induces Warts phosphorylation and downregulates Yki activity. Interestingly, Mer and Ex are both transcriptional targets of the Hpo pathway and act in a negative feedback loop to regulate Hpo pathway activity.35

Ex and Fat colocalize at the adherens junctions and loss of Fat leads to reduced membrane localization of Ex, suggesting that Fat may regulate Ex activity by controlling its subcellular localization.30, 31 In the eye, the phenotype associated with overexpression of Ex is dominant over the phenotype caused by loss of Fat, consistent with Ex acting downstream of Fat.30, 31 In the wing, however, overexpression of Ex is not sufficient to suppress fat mutant phenotype even though high levels of Ex accumulate at normal subapical position.34 It is possible that Fat may not only regulate the subcellular localization but also control the activation of Ex so that Ex cannot function in the absence of Fat even when it localizes properly. Alternatively, or in addition to the mechanism stated above, Fat may act through a different pathway to regulate downstream signaling events. In support for the latter possibility is the observation that fat and ex mutations have additive effects on imaginal disc growth and development.34 Indeed, a previous study suggested that Fat acts through an unconventional myosin encoded by dachs.37 dachs mutations suppress tissue overgrowth as well as altered gene expression caused by fat mutations. Consistent with dachs acting downstream of fat, dachs protein levels at the membrane are negatively regulated by Fat. In addition, the normal subcellular localization and activity of Dachs require Approximated (App), a member of DHHC family of palmitoyltransferase.38 Dachs physically associates with Warts in cultured cells.29 As Fat signaling acts at least in part by stabilizing Wts,29 it would be interesting to determine whether Dachs mediates this aspect of Fat output.

Another classic tumor suppressor gene is discs overgrown (dco), which encodes a casein kinase 1 (CK1) family member, CK1ε.39 dco mutant cells exhibit deregulated expression of Fat/Hpo target genes, and epistasis analysis places dco between fat and dachs.29 However, the relevant Dco/CK1 substrate(s) in the Fat/Hpo pathway remains to be determined.

How does the Hpo pathway read the spatial and temporal signals?

The protocadherin Dachsous (Ds) functions as a ligand for Fat in the planer cell polarity (PCP) pathway.40 Several lines of evidence suggest that Ds functions as a candidate ligand for Fat in the Hpo pathway. ds mutations result in tissue overgrowth, albeit less severe than that caused by fat mutations.32, 41, 42 Ds and Fat participate in heterophilic cell adhesion in cultured cells, and stabilize each other at the cell surface in imaginal discs.33, 42 The expression of Fat and Hpo target genes is influenced by Ds in a nonautonomous manner.29, 43 Ds and another protein, Four-jointed (Fj), a Golgi protein that phosphorylates Fat and Ds to influence their interaction,44 are distributed in a graded fashion in developing imaginal discs.41, 45 Interestingly, juxtaposition of cells expressing different levels of Ds or Fj stimulates the expression of Hpo target genes and cell proliferation in a manner depending on Fat signaling,46, 47 suggesting that Fat signaling activity is modulated by discontinuities of Ds/Fj. The model implies that the steepness of Ds/Fj gradient drives disc growth by modulating the Fat/Hpo signaling activity. For example, at early stages during larval development when the discs are small, the Ds/Fj gradient is steep and disc growth is promoted. At later stages, the Ds/Fj gradient is flattened due to increased disc size; as a consequence, tissue growth is retarded. However, there is no direct evidence that Hpo pathway activity is modulated in space or over time in a manner correlating with cell proliferation during normal development. Thus, it remains possible that Hpo pathway activity could be maintained at a constant level throughout larval development.

Dpp signaling regulates the expression of both Ds and Fj.46 In addition, juxtaposition of cells transducing different levels of Dpp signaling also stimulates cell proliferation and Hpo target gene expression through Dachs.46, 48 These and other observations led to the proposal that the Fat/Hpo pathway may couple cell growth and organ size control to morphogen gradients such as Dpp gradient.46 However, a recent study provided evidence that normal growth can occur even in the absence of graded Dpp signaling.49 In addition, measurement of Dpp gradient or its activity gradient (through p-Mad staining) during disc growth did not detect any change in the steepness of these gradients at different larval stages.50 Thus, it is unclear whether the steepness of Dpp gradient is a driving force for tissue growth during normal development. It is possible that other morphogen gradients such Wg morphogen may promote disc growth in the absence of graded Dpp signaling. It is also possible that cell proliferation stimulated by Dpp signaling discontinuity may reflect a growth control mechanism utilized during wound healing and regeneration when cells exposed to different levels of Dpp are juxtaposed after injury.

Hpo signaling in mammals

The core components of the Drosophila Hpo pathway are highly conserved in mammals (see Table1).51–53 In fact, several components of the Drosophila Hpo pathway can be functionally replaced by their mammalian homologs.11, 15, 21, 22, 54, 55 Accumulating evidence has suggested that the mammalian Hpo pathway regulates cell contact inhibition, organ size, and cancer development.52, 55–60 Mice lacking Lats1, a vertebrate orthologue of Drosophila Wts, develop soft-tissue sarcomas, ovarian tumours, and pituitary dysfunction.61 Embryos deficient for Lats2, another mammalian orthologue of Wts, showed overgrowth in several mesodermal tissues, and fibroblasts derived from these embryos (MEFs) have growth advantages, exhibit a defect in contact inhibition and cytokinesis, and display centrosome amplification and genome instability.62 Complete knock-out of Lats2 resulted in an acceleration of exit from mitosis and mitotic defects including centrosome fragmentation and cytokinesis defects, followed by nuclear enlargement and multinucleation.63 Human Mst2, an orthologue of Hpo, phosphorylates and activates both Lats1 and Lats2.64 The human homolog of Sav, hWW45, is mutated in several cancer cell lines.9 Mice lacking WW45 revealed a crucial role for WW45 in cell-cycle exit and epithelial terminal differentiation, and WW45 is required for Mst1 activation for proper epithelial tissue development in mammals.65

Table 1.

Conserved Hpo pathway components between Drosophila and mammals

| Drosophila | Mouse | Human | Protein type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dachsous (Ds) | Dchs1, Dchs2 | DCHS1, DCHS2 | Protocadherin |

| Fat | Fat1-Fat3, Fat4/Fat-j | Fat1-Fat3,Fat4/Fat-j | Protocadherin |

| Four-jointed (Fj) | Fjx1 | Fjx1 | Golgi associated kinase |

| Discs overgrown (Dco) | CK1ε/δ | CK1ε/δ | Ser/Thr kinase |

| Expanded (Ex) | Ex1/Frmd6,Ex2 | Willin | FERM-domain |

| Merlin (Mer) | Merlin | NF2 (Merlin) | FERM-domain |

| Hippo(Hpo /dMst) | Mst1, Mst2 | Mst1/STK4 Mst2/STK3 |

Ser/Thr kinase |

| Salvador (Sav) | WW45/Sav1 | hWW45/SAV1 | WW domain |

| Warts (Wts) | Lats1, Lats2 | LATS1 and LATS2 | Ser/Thr kinase |

| Mob as tumor suppressor (Mats) | Mob1, Mob2 | MOBKL1A, MOBKL1B | NDR kinase family cofactor |

| Yorkie (Yki) | Yap TAZ |

YAP TAZ/WWTR1 |

WW domain, transcriptional co-activator |

| Scalloped (Sd) | Tead/Tef1-Tef4 | Tead1-Tead4 | TEA DNA binding domain |

Yap, a human orthologue of yki, is a candidate oncogene amplified in several types of tumor.57, 66 Recent studies revealed that Yap is the primary effector of the mammalian Hippo pathway.25, 58, 59, 67 Yap overexpression in cultured cells is able to overcome cell contact inhibition and Yap inactivation can restore contact inhibition in a human cancer cell line bearing deletion of hWW45/Sav.58 Yap nuclear localization is inhibited by Lats phosphorylation as well as by cell-cell contact.25, 58 Yap overexpression in mouse liver caused excessive tissue growth and reversibly increased liver size,25, 59 and long-term overexpression of Yap led to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).25 Furthermore, Yap protein levels and/or nuclear localization are elevated in many human cancers including liver cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer.25, 58, 60 Several recent studies provided evidence that TEAD family of transcription factors mediate the function of Yap to regulate cell proliferation and contact inhibition in mammals.68–70

Much less is known about the upstream signals regulating the mammalian Hpo pathway, except that Merlin has been extensively studied for its tumor suppressor function in mammalian nervous tissues.36, 71–73 A recent study showed that loss of Merlin in meningioma cells resulted in loss of contact-dependent growth inhibition, enhanced anchorage independent cell growth, and increased cell proliferation due to accelerated S-phase entry. In addition, loss of Merlin in meningioma cell lines or primary tumors resulted in increased protein level and nuclear localization of Yap.74 Fat4 is essential for vertebrate PCP, and loss of Fat4 disrupts oriented cell divisions and tubule elongation during kidney development, leading to cystic kidney disease.75 Furthermore, Fat4 is a candidate tumor suppressor whose expression is lost in a fraction of human breast tumor cell lines and primary tumors.76

Future perspective

The Hpo pathway has emerged as an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that regulates cell growth, proliferation, and cell death during normal development and its malfunction has been linked to several types of human cancer. The past several years have witnessed an explosion of information regarding various aspects of Hpo signaling cascade. However, many important questions regarding the signaling mechanism as well as the physiological and pathological roles of the Hpo pathway remain. In mammals, the upstream signal(s) that regulates Hpo signaling activity remains obscure. One intriguing observation is that cell-contact inhibition can modulate Yki activity but the molecular pathway that links the detection of cell density to Yki regulation has not been defined. It also remains to be determined whether mammalian Fat homologs participate in this process. Whether the Hpo pathway activity is modulated in space and over the time course of normal development remains a critical issue. More direct measurement of pathway activity, e.g., by measuring the phosphorylation states of Yki, Wts, or Hpo should be informative but could be challenging, not only because these reagents are difficult to develop but also because the change in Hpo pathway activity over time might be subtle. Hpo pathway reporter genes might also be useful to monitor spatial and temporal changes in Hpo pathway activity.

The Hpo signaling pathway is unlikely to be linear. There is evidence that another yet to be identified receptor may act in parallel with Fat.35 Similarly, the Hpo pathway may branch out at other levels. For example, Hpo may directly regulate the turnover of Diap1 in addition to controlling its expression.12 The biological effect of Hpo signaling is likely to be context dependent, and there is evidence that Yap can promote cell death by binding to a p53 family member, p73.77, 78 In Drosophila, Hpo pathway components also play roles in other developmental processes including retina cell patterning,79 dendrite morphogenesis,80, 81 regulation of oocyte polarity,82–84 and salivary gland degeneration.85 Furthermore, Hpo signaling regulates salivary gland cell death in a PI3K-dependent, but Yki-independent, manner.85 The specification of posterior follicle cell fate identify during oogenesis, another process that involves Hpo signaling, does not require the action of Fat.81 These observations indicate that there can be deviations from the canonical pathway depending on developmental contexts. With respect to situations in which Hpo pathway goes awry, Yap is upregulated in many cancers but the underlying mechanisms and functional significance remain largely undetermined. It is possible that other growth control pathways can feed into the Hpo pathway at different levels. Uncovering pathway crosstalk should provide better insight into the signaling network underlying the control of tissue growth and organ size during normal development and how cancer cells hijack the signaling network to favor their survival and proliferation.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar Program, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation to Jin Jiang. J.J. is a Eugene McDermott Endowed Scholar in Biomedical Science at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

References

- 1.Conlon I, Raff M. Size Control in Animal Development. Cell 1999; 96:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariharan IK, Bilder D. Regulation of imaginal disc growth by tumor-suppressor genes in Drosophila. Annual review of genetics 2006; 40:335–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant PJ, Simpson P. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of growth in developing organs. Q Rev Biol 1984; 59:387–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant PJ, Levinson P. Intrinsic growth control in the imaginal primordia of Drosophila, and the autonomous action of a lethal mutation causing overgrowth. Developmental biology 1985; 107:355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant PJ, Huettner B, Held LJ, Ryerse J, Szidonya J. Mutations at the fat locus interfere with cell proliferation control and epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila. Developmental biology 1988; 129:541–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson KL, Justice RW, Bryant PJ. Drosophila in cancer research: the first fifty tumor suppressor genes. Journal of cell science 1994; 18:19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justice RW, Zilian O, Woods DF, Noll M, Bryant PJ. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes & Development 1995; 9:534–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu T, Wang W, Zhang S, Stewart RA, Yu W. Identifying tumor suppressors in genetic mosaics: the Drosophila lats gene encodes a putative protein kinase. Development 1995; 121:1053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DCR, Schiripo TA, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. salvador Promotes Both Cell Cycle Exit and Apoptosis in Drosophila and Is Mutated in Human Cancer Cell Lines. Cell 2002; 110:467–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, Jiang J. The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes and Development 2003; 17:2514–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D. hippo Encodes a Ste-20 Family Protein Kinase that Restricts Cell Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis in Conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell 2003; 114:445–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst Ortholog, hippo, Restricts Growth and Cell Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis. Cell 2003; 114:457–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantalacci S, Tapon N, Leopold P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nature Cell Biology 2003; 5:921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Chunyao T, Halder G. Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nature Cell Biology 2003; 5:914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai Z-C, Wei X, Shimizu T, Ramos E, Rohrbaugh M, Nikolaidis N, Ho L-L, Li Y. Control of Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis by Mob as Tumor Suppressor, Mats. Cell 2005; 120:675–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei X, Shimizu T, Lai ZC. Mob as tumor suppressor is activated by Hippo kinase for growth inhibition in Drosophila. Embo J 2007; 26:1772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Praskova M, Xia F, Avruch J. MOBKL1A/MOBKL1B phosphorylation by MST1 and MST2 inhibits cell proliferation. Curr Biol 2008; 18:311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey K, Tapon N. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway [mdash] an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson BJ, Cohen SM. The Hippo Pathway Regulates the bantam microRNA to Control Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis in Drosophila. Cell 2006; 126:767–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Yamada-Mabuchi M, Morris EJ, Tanwar PS, Dobens L, Gluderer S, Khan S, Cao J, Stocker H, Hafen E, Dyson NJ, Raftery LA. The Drosophila homolog of human tumor suppressor TSC-22 promotes cellular growth, proliferation, and survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008; 105:5414–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo Signaling Pathway Coordinately Regulates Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis by Inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 2005; 122:421–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF Family Protein Scalloped Mediates燭ranscriptional Output of the Hippo Growth-Regulatory Pathway. Developmental Cell 2008; 14:388–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF Family of Transcription Factor Scalloped Mediates Hippo Signaling in Organ Size Control. Developmental Cell 2008; 14:377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goulev Y, Fauny JD, Gonzalez-Marti B, Flagiello D, Silber J, Zider A. SCALLOPED Interacts with YORKIE, the Nuclear Effector of the Hippo Tumor-Suppressor Pathway in Drosophila. Current Biology 2008; 18:435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 2007; 130:1120–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development 2008; 135:1081–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barolo S, Posakony JW. Three habits of highly effective signaling pathways: principles of transcriptional control by developmental cell signaling. Genes & development 2002; 16:1167–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett FC, Harvey KF. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol 2006; 16:2101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho E, Feng Y, Rauskolb C, Maitra S, Fehon R, Irvine KD. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat Genet 2006; 38:1142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of expanded in the hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol 2006; 16:2081–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Kango-Singh M, Udan R, Chen CL, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G. The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr Biol 2006; 16:2090–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahoney PA, Weber U, Onofrechuk P, Biessmann H, Bryant PJ, Goodman CS. The fat tumor suppressor gene in Drosophila encodes a novel member of the cadherin gene superfamily. Cell 1991; 67:853–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Separating the adhesive and signaling functions of the Fat and Dachsous protocadherins. Development 2006; 133:2315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Fat and expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through warts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007; 104:20362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, Jafar-Nejad H, Halder G. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClatchey AI, Giovannini M. Membrane organization and tumorigenesis--the NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin. Genes & development 2005; 19:2265–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao Y, Rauskolb C, Cho E, Hu WL, Hayter H, Minihan G, Katz FN, Irvine KD. Dachs: an unconventional myosin that functions downstream of Fat to regulate growth, affinity and gene expression in Drosophila. Development 2006; 133:2539–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. The DHHC palmitoyltransferase approximated regulates Fat signaling and Dachs localization and activity. Curr Biol 2008; 18:1390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zilian O, Frei E, Burke R, Brentrup D, Gutjahr T, Bryant PJ, Noll M. double-time is identical to discs overgrown, which is required for cell survival, proliferation and growth arrest in Drosophila imaginal discs. Development (Cambridge, England) 1999; 126:5409–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence PA, Struhl G, Casal J. Planar cell polarity: one or two pathways? Nat Rev Genet 2007; 8:555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark HF, Brentrup D, Schneitz K, Bieber A, Goodman C, Noll M. Dachsous encodes a member of the cadherin superfamily that controls imaginal disc morphogenesis in Drosophila. Genes & development 1995; 9:1530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development 2004; 131:3785–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho E, Irvine KD. Action of fat, four-jointed, dachsous and dachs in distal-to-proximal wing signaling. Development 2004; 131:4489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishikawa HO, Takeuchi H, Haltiwanger RS, Irvine KD. Four-jointed is a Golgi kinase that phosphorylates a subset of cadherin domains. Science (New York, NY 2008; 321:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villano JL, Katz FN. four-jointed is required for intermediate growth in the proximal-distal axis in Drosophila. Development (Cambridge, England) 1995; 121:2767–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogulja D, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Morphogen control of wing growth through the Fat signaling pathway. Dev Cell 2008; 15:309–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C, Halder G. Boundaries of Dachsous Cadherin activity modulate the Hippo signaling pathway to induce cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008; 105:14897–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rogulja D, Irvine KD. Regulation of cell proliferation by a morphogen gradient. Cell 2005; 123:449–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwartz MS, Smith GH, Medina D. The effect of parity, tumor latency and transplantation on the activation of int loci in MMTV-induced, transplanted C3H mammary pre-neoplasias and their tumors. Int J Cancer 1992; 51:805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hufnagel L, Teleman AA, Rouault H, Cohen SM, Shraiman BI. On the mechanism of wing size determination in fly development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007; 104:3835–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan D Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes and Development 2007; 21:886–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng Q, Hong W. The Emerging Role of the Hippo Pathway in Cell Contact Inhibition, Organ Size Control, and Cancer Development in Mammals. Cancer Cell 2008; 13:188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reddy BV, Irvine KD. The Fat and Warts signaling pathways: new insights into their regulation, mechanism and conservation. Development 2008; 135:2827–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tao W, Zhang S, Turenchalk GS, Stewart RA, St John MA, Chen W, Xu T. Human homologue of the Drosophila melanogaster lats tumour suppressor modulates CDC2 activity. Nat Genet 1999; 21:177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a Universal Size-Control Mechanism in Drosophila and Mammals. Cell 2007; 130:1120–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker NE, Li W. Cell Competition and Its Possible Relation to Cancer. Cancer Research 2008; 68:5505–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, Fan S-T, Luk JM, Wigler M, Hannon GJ. Identification and Validation of Oncogenes in Liver Cancer Using an Integrative Oncogenomic Approach. Cell 2006; 125:1253–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, Xie J, Ikenoue T, Yu J, Li L, Zheng P, Ye K, Chinnaiyan A, Halder G, Lai Z-C, Guan K-L. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes and Development 2007; 21:2747–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Camargo FD, Gokhale S, Johnnidis JB, Fu D, Bell GW, Jaenisch R, Brummelkamp TR. YAP1 increases organ size and expands undifferentiated progenitor cells. Curr Biol 2007; 17:2054–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinhardt AA, Gayyed MF, Klein AP, Dong J, Maitra A, Pan D, Montgomery EA, Anders RA. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Hum Pathol 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.St John MA, Tao W, Fei X, Fukumoto R, Carcangiu ML, Brownstein DG, Parlow AF, McGrath J, Xu T. Mice deficient of Lats1 develop soft-tissue sarcomas, ovarian tumours and pituitary dysfunction. Nat Genet 1999; 21:182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McPherson JP, Tamblyn L, Elia A, Migon E, Shehabeldin A, Matysiak-Zablocki E, Lemmers B, Salmena L, Hakem A, Fish J, Kassam F, Squire J, Bruneau BG, Hande MP, Hakem R. Lats2/Kpm is required for embryonic development, proliferation control and genomic integrity. Embo J 2004; 23:3677–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yabuta N, Okada N, Ito A, Hosomi T, Nishihara S, Sasayama Y, Fujimori A, Okuzaki D, Zhao H, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Nojima H. Lats2 is an essential mitotic regulator required for the coordination of cell division. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:19259–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan EH, Nousiainen M, Chalamalasetty RB, Schafer A, Nigg EA, Sillje HH. The Ste20-like kinase Mst2 activates the human large tumor suppressor kinase Lats1. Oncogene 2005; 24:2076–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JH, Kim TS, Yang TH, Koo BK, Oh SP, Lee KP, Oh HJ, Lee SH, Kong YY, Kim JM, Lim DS. A crucial role of WW45 in developing epithelial tissues in the mouse. Embo J 2008; 27:1231–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Overholtzer M, Zhang J, Smolen GA, Muir B, Li W, Sgroi DC, Deng C-X, Brugge JS, Haber DA. Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006:0605579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hao Y, Chun A, Cheung K, Rashidi B, Yang X. Tumor suppressor LATS1 is a negative regulator of oncogene YAP. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:5496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, Yu J, Lin JD, Wang CY, Chinnaiyan AM, Lai ZC, Guan KL. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev 2008; 22:1962–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao X, Pfaff SL, Gage FH. YAP regulates neural progenitor cell number via the TEA domain transcription factor. Genes Dev 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ota M, Sasaki H. Mammalian Tead proteins regulate cell proliferation and contact inhibition as transcriptional mediators of Hippo signaling. Development 2008; 135:4059–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McClatchey AI. Neurofibromatosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2007; 2:191–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Girard N [Imaging features of neurofibromatosis type 2]. J Neuroradiol 2005; 32:198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goutagny S, Bouccara D, Bozorg-Grayeli A, Sterkers O, Kalamarides M. [Neurofibromatosis type 2]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2007; 163:765–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Striedinger K, VandenBerg SR, Baia GS, McDermott MW, Gutmann DH, Lal A. The neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, regulates human meningioma cell growth by signaling through YAP. Neoplasia 2008; 10:1204–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nature genetics 2008; 40:1010–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qi C, Zhu YT, Hu L, Zhu YJ. Identification of Fat4 as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in breast cancers. International journal of cancer 2009; 124:793–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kawahara M, Hori T, Chonabayashi K, Oka T, Sudol M, Uchiyama T. Kpm/Lats2 is linked to chemo-sensitivity of leukemic cells through the stabilization of p73. Blood 2008:blood-2007-09-111773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Strano S, Monti O, Pediconi N, Baccarini A, Fontemaggi G, Lapi E, Mantovani F, Damalas A, Citro G, Sacchi A, Del Sal G, Levrero M, Blandino G. The transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein drives p73 gene-target specificity in response to DNA Damage. Molecular cell 2005; 18:447–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mikeladze-Dvali T, Wernet MF, Pistillo D, Mazzoni EO, Teleman AA, Chen Y-W, Cohen S, Desplan C. The Growth Regulators warts/lats and melted Interact in a Bistable Loop to Specify Opposite Fates in Drosophila R8 Photoreceptors. Cell 2005; 122:775–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emoto K, Parrish JZ, Jan LY, Jan YN. The tumour suppressor Hippo acts with the NDR kinases in dendritic tiling and maintenance. Nature 2006; 443:210–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parrish JZ, Emoto K, Jan LY, Jan YN. Polycomb genes interact with the tumor suppressor genes hippo and warts in the maintenance of Drosophila sensory neuron dendrites. Genes Dev 2007; 21:956–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Polesello C, Tapon N. Salvador-warts-hippo signaling promotes Drosophila posterior follicle cell maturation downstream of notch. Curr Biol 2007; 17:1864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meignin C, Alvarez-Garcia I, Davis I, Palacios IM. The salvador-warts-hippo pathway is required for epithelial proliferation and axis specification in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2007; 17:1871–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu J, Poulton J, Huang YC, Deng WM. The hippo pathway promotes Notch signaling in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, and oocyte polarity. PLoS ONE 2008; 3:e1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dutta S, Baehrecke EH. Warts Is Required for PI3K-Regulated Growth Arrest, Autophagy, and Autophagic Cell Death in Drosophila. Current Biology 2008; 18:1466–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]