X-ray crystal structures of carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) in complex with nicotinic acid and ferulic acid are presented. Previously deposited structures of CA II in complex with carboxylic acid-based compounds are compared and the general mechanisms of CA inhibition are discussed.

Keywords: carbonic anhydrase II, carboxylic acids, structure-guided drug design

Abstract

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are molecular targets in various diseases. While many sulfonamide-based drugs are in clinical use, CA inhibitor design is moving towards the incorporation of alternative zinc-binding groups, such as carboxylic acids, to promote CA isoform-specific inhibition. Here, X-ray crystal structures of CA II in complex with nicotinic acid and ferulic acid determined to 1.70 and 1.50 Å resolution, respectively, are reported. Furthermore, the structures of these two compounds are superimposed with previously determined structures to compare the mechanisms of inhibition and the properties of carboxylic acid-based CA inhibitors. This study examines an important class of alternative, non-sulfonamide-based CA inhibitors and provides insight to facilitate the structure-guided design of CA isoform-specific inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are a family of zinc metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible hydration of CO2 to produce HCO3 − and a proton (Steiner et al., 1975 ▸; Supuran, 2016a ▸). Aberrant CA expression has been associated with disease, and multiple CA isoforms have been recognized as biomarkers and therapeutic targets (Frost & McKenna, 2013 ▸; Maren, 1967 ▸; Supuran, 2008 ▸; McDonald et al., 2012 ▸). CA has traditionally been inhibited by sulfonamide-based compounds (classical inhibitors; Keilin & Mann, 1940 ▸; Supuran, 2010 ▸). However, there are 15 isoforms expressed in humans that share high sequence and structural homology within the active site. This homology results in off-target drug binding that can cause undesired side effects and sequestration of the drug, requiring higher doses for effective treatment. The design of nonclassical CA inhibitors has therefore been proposed to deselect from interactions with zinc and to improve isoform specificity by interacting with isoform-unique residues in and around the entrance of the active site (Lomelino et al., 2016 ▸; Supuran, 2016b ▸).

Carboxylic acid-based compounds have recently been identified as one such promising class of CA inhibitors. Previous structural studies have shown that these compounds exhibit multiple binding sites. Similar to classical sulfonamide-based compounds, some inhibitors have been shown to bind directly to the active-site zinc, displacing the zinc-bound water (ZBW) that is essential for catalytic activity (Boone et al., 2014 ▸; Woods et al., 2016 ▸; Langella et al., 2016 ▸). Alternatively, a second binding mode inhibits enzymatic activity by anchoring to the ZBW (Martin & Cohen, 2012 ▸; Cadoni et al., 2017 ▸; Woods et al., 2016 ▸). Lastly, inhibitors have been observed to bind outside the active site in a pocket on the surface of the enzyme, which is hypothesized to restrict movement of the proton-shuttle residue His64 to the ‘out’ conformation and to prevent the regeneration of the nucleophilic hydroxide for catalysis (D’Ambrosio et al., 2015 ▸).

Here, we present X-ray crystal structures of CA II in complex with two carboxylic acid-based inhibitors, nicotinic acid (NA) and ferulic acid (FA), and discuss the properties of carboxylic acid-based CA inhibitors that determine the mode of binding.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

CA II was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 competent cells as described previously (Tanhauser et al., 1992 ▸; Pinard et al., 2013 ▸). The cells were grown until an OD600 of ∼0.6 was attained, and protein expression was then induced with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (Table 1 ▸). The cells were then harvested via centrifugation and lysed using a microfluidizer. The protein was purified by affinity chromatography on a p-aminomethylbenzenesulfonamide agarose column. CA II was eluted with buffer containing 0.4 M sodium azide, which was subsequently removed by buffer exchange. The final purity was verified via SDS–PAGE.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | Homo sapiens |

| Expression vector | pET31F1+ |

| Expression host | E. coli |

| Complete amino-acid sequence | HWGYGKHNGPEHWHKDFPIAKGERQSPVDIDTHTAKYDPSLKPLSVSYDQATSLRILNNGHAFNVEFDDSQDKAVLKGGPLDGTYRLIQFHFHWGSLDGQGSEHTVDKKKYAAELHLVHWNTKYGDFGKAVQQPDGLAVLGIFLKVGSAKPGLQKVVDVLDSIKTKGKSADFTNFDPRGLLPESLDYWTYPGSLTTPPLLECVTWIVLKEPISVSSEQVLKFRKLNFNGEGEPEELMVDNWRPAQPLKNRQIKASFK |

2.2. Crystallization

Purified CA II was diluted with storage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.8) to a final concentration of 10 mg ml−1. Crystal drops were set up with a 1:1 ratio of protein solution to precipitant solution (1.6 M sodium citrate, 50 mM Tris pH 7.8) with a total volume of 5 µl. CA II crystals were grown at room temperature using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method and crystal growth was observed within three days (Table 2 ▸). Crystals were soaked with stock solutions of 1 M NA or 1.2 M FA overnight. The crystals were then transferred into a cryoprotectant solution consisting of 20% glycerol prior to flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen for shipment.

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Method | Hanging-drop vapor diffusion |

| Temperature (K) | 298 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 10 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 50 mM Tris pH 7.8 |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 1.6 M sodium citrate, 50 mM Tris pH 7.8 |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 5 µl, 1:1 |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 500 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

X-ray diffraction data were collected on the F1 beamline at Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) using a PILATUS 6M detector. Data sets were collected with a crystal-to-detector distance of 270 mm, an oscillation angle of 1° and an exposure time of 4 s (FA) or 5 s (NA), with a total of 180 images. Diffraction data were indexed and integrated in XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▸) and then scaled in space group P21 using AIMLESS (Evans & Murshudov, 2013 ▸) from the CCP4 suite of programs (Winn et al., 2011 ▸; Table 3 ▸). Phases were determined via molecular replacement using the structure of CA II (PDB entry 3ks3; Avvaru et al., 2010 ▸) as a search model. Modifications to the models were performed in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸), whereas refinements were performed and ligand restraint files were generated in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸). Figures were produced using PyMOL (Schrödinger).

Table 3. Data-collection, processing and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outer resolution shell.

| CA II–NA | CA II–FA | |

|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 6mbv | 6mby |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.977 | 0.977 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 270 | 270 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 1 | 1 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 180 | 180 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 5 | 4 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 42.1, 41.1, 71.8 | 42.1, 41.3, 72.1 |

| β (°) | 104.3 | 104.3 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.25 | 0.14 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.42–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 25.29–1.50 (1.55–1.50) |

| Total No. of reflections | 88388 (8888) | 129811 (12710) |

| No. of unique reflections | 26046 (2556) | 38932 (3835) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.6 (96.0) | 99.6 (98.9) |

| Multiplicity | 3.4 (3.5) | 3.3 (3.3) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 14.2 (2.4) | 13.8 (2.6) |

| R meas | 0.071 (0.58) | 0.066 (0.53) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.785) | 0.998 (0.849) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 16.6 | 11.7 |

| Final R cryst | 0.1516 (0.2032) | 0.1518 (0.2137) |

| Final R free | 0.1770 (0.2024) | 0.1742 (0.2187) |

| No. of non-H atoms | ||

| Protein | 2055 | 2063 |

| Ligand | 16 | 25 |

| Solvent | 138 | 207 |

| Total | 2209 | 2295 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.014 | 0.008 |

| Angles (°) | 1.20 | 1.14 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 20.3 | 15.5 |

| Ligand | 20.0 | 23.8 |

| Solvent | 27.0 | 24.6 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored regions (%) | 96.1 | 97.3 |

| Allowed regions (%) | 3.9 | 2.7 |

3. Results and discussion

As carboxylic acid-based inhibitors have been observed to bind directly to the zinc, anchor to the ZBW and bind outside the active site, the crystal structures deposited in the PDB were examined to rationalize the properties that contribute to the preferred mode of binding. But-2-enoic acids and compounds containing a carboxylic acid attached to a five- or six-membered ring were observed to bind ‘indirectly’ by anchoring to the ZBW at a distance of ∼2.7 Å (Fig. 1 ▸ a). Such compounds would be unable to bind directly to the zinc owing to the steric hindrance of active-site residues such as Leu198, Thr200 and Val121. Alternatively, the inclusion of a linker between the carboxylic acid and the inhibitor tail allows rotation about the linker, preventing clashes and enabling direct binding to zinc (Fig. 1 ▸ b). Based on these observed patterns, NA was predicted to inhibit CA II activity by anchoring to the ZBW, whereas FA was expected to bind directly to the zinc, displacing the ZBW.

Figure 1.

Overlay of deposited carboxylic acid-based inhibitors. (a) Compounds that bind ‘indirectly’ by anchoring to the ZBW: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (orange; PDB entry 4e3g; Martin & Cohen, 2012 ▸), 2-hydroxybenzoic acid (blue; PDB entry 5m78; S. Gloeckner, A. Heine & G. Klebe, unpublished work), 2-sulfanylbenzoic acid (light purple; PDB entry 4e4a; Martin & Cohen, 2012 ▸), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (dark purple; PDB entry 4e3d; Martin & Cohen, 2012 ▸), 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid (dark pink; PDB entry 4e3f; Martin & Cohen, 2012 ▸), 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (light pink; PDB entry 5flt; Woods et al., 2016 ▸), (E)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)but-2-enoic acid (gold; PDB entry 5fls; Woods et al., 2016 ▸), (E)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)but-2-enoic acid (green; PDB entry 5eh8; Woods et al., 2016 ▸) and 3-(1-ethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid (yellow; PDB entry 6b4d; Cadoni et al., 2017 ▸). (b) Compounds that bind directly to zinc and displace the ZBW: [1,1-dioxido-3-oxo-1,2-benzothiazol-2(3H)-yl]acetic acid (raspberry; PDB entry 5clu; Langella et al., 2016 ▸), 2-(4-ethoxyphenyl)ethanoic acid (cyan; PDB entry 5fnj; Woods et al., 2016 ▸), 2-(4-phenylmethoxyphenyl)ethanoic acid (olive; PDB entry 5flq; Woods et al., 2016 ▸), (E)-3-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)prop-2-enoic acid (teal; PDB entry 5ehw; Woods et al., 2016 ▸), (E)-3-(3-{[3-(2-hydroxy-2-oxoethyl)phenyl]methoxy}phenyl)prop-2-enoic acid (purple; PDB entry 5ehv; Woods et al., 2016 ▸) and cholic acid (light orange; PDB entry 4n16; Boone et al., 2014 ▸).

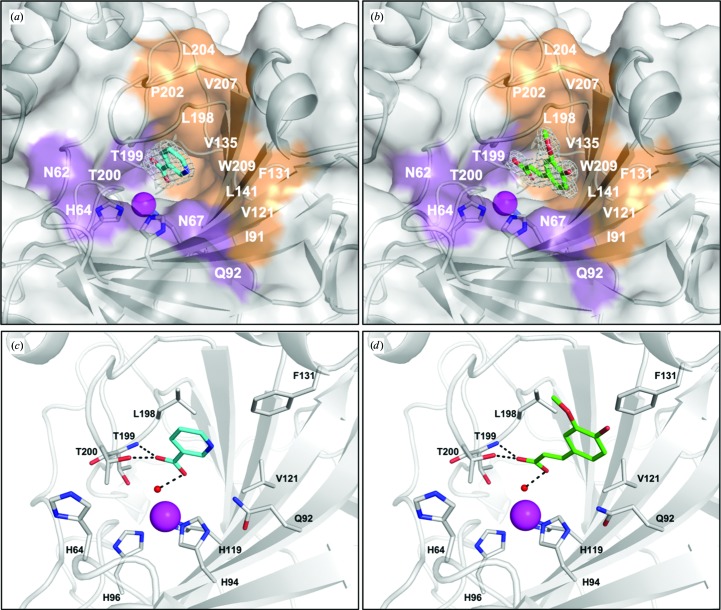

The crystal structures of CA II in complex with NA and FA were determined to resolutions of 1.7 and 1.5 Å, respectively. Unambiguous electron density in the initial F o − F c OMIT map was observed in the active site of each complex (Figs. 2 ▸ a and 2 ▸ b). Interestingly, both NA and FA were observed to anchor to the ZBW with the carboxylic acid group of both compounds oriented in a similar position as previously determined anchoring carboxylic acid-based inhibitors. The carboxyl O atom of NA and FA was shown to form hydrogen bonds to the amide of Thr199 and the hydroxyl of Thr200 (Figs. 2 ▸ c and 2 ▸ d). Additionally, the two inhibitors were further stabilized by van der Waals interactions with the active-site residues Gln92, Val121, Phe131, Leu198 and Pro202.

Figure 2.

Binding of nicotinic acid (NA) and ferulic acid (FA). Surface representation of CA II with electron density of (a) NA and (b) FA. The 2F o − F c electron-density maps are contoured at σ = 1.0. CA II active-site binding interactions with (c) NA and (d) FA. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashes.

In order to understand the unexpected binding mode of FA, a model of FA interacting directly with zinc was generated using the structure of a similar, acrylic acid-based compound (PDB entry 5ehw) as a template (Woods et al., 2016 ▸). The positions of the ligand atoms shared between ferulic acid and the template ligand were held constant, in addition to the positions of the template protein atoms. This model shows that the direct binding of FA would result in obstruction of the methoxy group by the active-site residues Pro201 (∼1.6 Å) or Phe131 (∼1.3 Å), depending on the orientation of the ring (Fig. 3 ▸). Therefore, substitutions on the tails of linker-containing carboxylic acid-based compounds must also be taken into consideration.

Figure 3.

In silico model of ferulic acid directly binding to zinc. Note that this would result in steric clashes (colored red) with CA II active-site residues Phe131 or Pro201 (FA is colored green or yellow, respectively).

Understanding the properties of carboxylic acid-based compounds that promote direct binding or ‘indirect’ binding provides guidance in the design of isoform-specific CA inhibitors. Therefore, the derivatization of aromatic compounds or the tails of linker-containing inhibitors will promote binding through the ZBW owing to steric hindrance, increasing the interactions with isoform-unique residues that more frequently extend radially outwards from the active-site zinc.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: carbonic anhydrase II, complex with nicotinic acid, 6mbv

PDB reference: complex with ferulic acid, 6mby

Tables including compound names, structures and PDB accession codes for the previously deposited structures shown in Figure 1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18018344/no5149sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

The experiment was performed on the F1 beamline of CHESS. The authors would like to acknowledge the expertise and guidance provided by the experimental staff. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grants TL1TR001428 and L1TR001427.

References

- Adams, P. D., Afonine, P. V., Bunkóczi, G., Chen, V. B., Davis, I. W., Echols, N., Headd, J. J., Hung, L.-W., Kapral, G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Oeffner, R., Read, R. J., Richardson, D. C., Richardson, J. S., Terwilliger, T. C. & Zwart, P. H. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Avvaru, B. S., Kim, C. U., Sippel, K. H., Gruner, S. M., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Silverman, D. N. & McKenna, R. (2010). Biochemistry, 49, 249–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boone, C. D., Tu, C. & McKenna, R. (2014). Acta Cryst. D70, 1758–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cadoni, R., Pala, N., Lomelino, C., Mahon, B. P., McKenna, R., Dallocchio, R., Dessì, A., Carcelli, M., Rogolino, D., Sanna, V., Rassu, M., Iaccarino, C., Vullo, D., Supuran, C. T. & Sechi, M. (2017). ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 8, 941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, K., Carradori, S., Monti, S. M., Buonanno, M., Secci, D., Vullo, D., Supuran, C. T. & De Simone, G. (2015). Chem. Commun. 51, 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frost, S. C. & McKenna, R. (2013). Carbonic Anhydrase: Mechanism, Regulation, Links to Disease, and Industrial Applications. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keilin, D. & Mann, T. (1940). Biochem. J. 34, 1163–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Langella, E., D’Ambrosio, K., D’Ascenzio, M., Carradori, S., Monti, S. M., Supuran, C. T. & De Simone, G. (2016). Chem. Eur. J. 22, 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lomelino, C. L., Supuran, C. T. & McKenna, R. (2016). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maren, T. H. (1967). Physiol. Rev. 47, 595–781. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Martin, D. P. & Cohen, S. M. (2012). Chem. Commun. 48, 5259–5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P. C., Winum, J.-Y., Supuran, C. T. & Dedhar, S. (2012). Oncotarget, 3, 84–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinard, M. A., Boone, C. D., Rife, B. D., Supuran, C. T. & McKenna, R. (2013). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 7210–7215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Steiner, H., Jonsson, B. H. & Lindskog, S. (1975). Eur. J. Biochem. 59, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C. T. (2008). Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C. T. (2010). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 3467–3474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C. T. (2016a). Biochem. J. 473, 2023–2032. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C. T. (2016b). J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31, 345–360. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tanhauser, S. M., Jewell, D. A., Tu, C. K., Silverman, D. N. & Laipis, P. J. (1992). Gene, 117, 113–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D., Ballard, C. C., Cowtan, K. D., Dodson, E. J., Emsley, P., Evans, P. R., Keegan, R. M., Krissinel, E. B., Leslie, A. G. W., McCoy, A., McNicholas, S. J., Murshudov, G. N., Pannu, N. S., Potterton, E. A., Powell, H. R., Read, R. J., Vagin, A. & Wilson, K. S. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Woods, L. A., Dolezal, O., Ren, B., Ryan, J. H., Peat, T. S. & Poulsen, S.-A. (2016). J. Med. Chem. 59, 2192–2204. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: carbonic anhydrase II, complex with nicotinic acid, 6mbv

PDB reference: complex with ferulic acid, 6mby

Tables including compound names, structures and PDB accession codes for the previously deposited structures shown in Figure 1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18018344/no5149sup1.pdf