Abstract

Background

The study sought to assess the prognostic impact of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with and without ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI and NSTEMI) in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) on admission.

Methods and Results

A large retrospective registry was used including all consecutive patients presenting with ventricular tachycardia (VT), fibrillation (VF), and sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) on admission from 2002 to 2016. AMI versus non‐AMI and STEMI versus NSTEMI were compared applying multivariable Cox regression models and propensity‐score matching for evaluation of the primary prognostic end point defined as long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years. Secondary end points were 30 days all‐cause mortality, cardiac death at 24 hours, in hospital death, and recurrent percutaneous coronary intervention (re‐PCI) at 2.5 years. In 2813 unmatched high‐risk patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA, AMI was present in 29% (10% STEMI, 19% NSTEMI) with higher rates of VF (54% versus 31%) and SCA (35% versus 26%), whereas VT rates were higher in non‐AMI (56% versus 30%) (P < 0.05). AMI‐related VT ≥48 hours was associated with higher mortality (log rank P = 0.001). Multivariable Cox regression models revealed non‐AMI (hazard ratio = 1.458; P = 0.001) and NSTEMI (hazard ratio = 1.460; P = 0.036) associated with increasing long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years, which was also proven after propensity‐score matching (non‐AMI versus AMI: 55% versus 43%, log rank P = 0.001, hazard ratio = 1.349; NSTEMI versus STEMI: 45% versus 34%, log rank P = 0.047, hazard ratio = 1.372). Secondary end points including 30 days and in‐hospital mortality, as well as re‐PCI were higher in non‐AMI patients.

Conclusions

In high‐risk patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA, non‐AMI revealed higher mortality than AMI, respectively NSTEMI than STEMI, alongside AMI‐related VT ≥48 hours.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, non ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac arrest, ventricular tachyarrhythmia

Subject Categories: Myocardial Infarction, Ventricular Fibrillation, Sudden Cardiac Death, Arrhythmias

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Data comparing prognostic outcomes of patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest depending on the presence or absence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is rare.

High‐risk patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest without AMI were associated with higher mortality compared with AMI, whereas non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) was associated with higher all‐cause mortality compared with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Ventricular tachyarrhythmias ≥48 hours after AMI were associated with higher long‐term all‐cause mortality.

The strongest predictors of death across all subgroups—non‐AMI, AMI, NSTEMI, STEMI—were cardiogenic shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, progressive heart failure, and concomitant chronic kidney disease.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Ventricular tachyarrhythmias in STEMI patients may more likely be attributable to the infarct itself without pre‐existing heart failure, whereas ventricular tachyarrhythmias in non‐AMI and NSTEMI patients may more often be associated with heart failure progression.

Patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest may profit from coronary angiography to exclude or treat relevant coronary artery disease, irrespective of the presence or absence of AMI.

Introduction

Ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) are usually caused by an acute coronary syndrome and associated with an adverse clinical outcome.1, 2, 3, 4 Patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) should undergo coronary angiography within 60 to 120 minutes, whereas patients with non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) no later than 72 hours, respectively.5 The risk of an irreversible myocardial ischemia, alleviating the development of focal or non‐focal arrhythmogenic sources degenerating into ventricular tachycardia (VT) or fibrillation (VF) was shown to be the highest within 72 hours.6, 7 Additionally, ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA can be caused by other etiologies beyond myocardial infarction, including cardiomyopathies, channelopathies, myocarditis, electrolyte disorders or trauma.8 These conditions may partly be associated with an increase of cardiac troponins reflecting the presence of type 2 myocardial infarction without evidence of a critical coronary artery stenosis.9, 10

Patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are characterized as high‐risk in the presence of life‐threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias, aborted cardiac arrest, hemodynamic instability, or cardiogenic shock. However, these high‐risk patients are not well represented in randomized controlled trials and reliable data about their long‐term prognosis are limited.9 Accordingly, recommendations of international guidelines are heterogeneous for AMI patients complicated by ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

Therefore, this study evaluates the differences of prognostic outcomes depending on the presence of AMI, NSTEMI and STEMI in consecutive patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on admission.

Methods

Study Patients, Design, and Data Collection

The present study retrospectively included all consecutive patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias or SCA on hospital admission from 2002 until 2016 at the First Department of Medicine, University Medical Centre Mannheim, Germany. Using the hospital information system, all relevant clinical data related to the index event was documented. The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure on reasonable personal request to the corresponding author.

Ventricular tachyarrhythmias comprised VT and VF, as defined by current international guidelines.8, 9 Sustained VT was defined by duration of >30 seconds or causing hemodynamic collapse within 30 seconds, and non‐sustained VT by duration of <30 seconds both characterized by wide QRS complexes (≥120 ms) at a rate greater than 100 beats per minute. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias were documented by 12‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG), ECG tele‐ monitoring, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or in case of unstable course or during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by external defibrillator monitoring. Documented VF was treated by external defibrillation and in case of prolonged instability with additional intravenous anti‐arrhythmic drugs during CPR. Onset of VT was stratified into VT occurring <48 hours and ≥48 hours of AMI onset. High‐risk criteria in the setting of AMI comprised the presence of life‐threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias, aborted cardiac arrest, hemodynamic instability, or cardiogenic shock.10

Further data being documented contained baseline characteristics, prior medical history, prior medical treatment, length of index stay, detailed findings of laboratory values at baseline, data derived from all non‐invasive or invasive cardiac diagnostics and device therapies, such as coronary angiography, electrophysiological examination, ICD, pacemaker or cardiac contractility modulation, as well as imaging modalities, such as echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. The overall presence of ICDs comprised the total sum of all patients with either a prior implanted ICD before admission, those undergoing new ICD implantation at index stay, as well as those with ICD implantation at the complete follow‐up period after index hospitalization, referring to conventional ICD, subcutaneous‐ICD (s‐ICD) and cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator function (CRT‐D). Pharmacological treatment was documented according to the discharge medication of patients surviving index hospitalization. Rates of overall ICDs and of pharmacological therapies are referred to the number of surviving patients being discharged from index hospitalization.

Every re‐visit at the outpatient clinic or rehospitalization was documented when related to recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias and adverse cardiac events. Adverse cardiac events comprised acute heart failure, CPR, cardiac surgery, recurrent percutaneous coronary intervention (re‐PCI), new implants or upgrades of cardiac devices, worsening or improvement of left ventricular function.

Documentation period lasted from index event until 2016. Documentation of all medical data was performed by independent cardiologists at the time of the patients′ clinical presentation at our institution, being masked to final data analyses.

The present study is derived from an analysis of the “Registry of Malignant Arrhythmias and Sudden Cardiac Death—Influence of Diagnostics and Interventions (RACE‐IT)” and represents a single‐center registry including consecutive patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA being acutely admitted to the University Medical Center Mannheim (UMM), Germany (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02982473) from 2002 until 2016. The registry was performed according to the principles of the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the medical ethics committee II of the Faculty of Medicine Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Germany, which waived the requirement for informed consent.

The medical center covers a general emergency department for emergency admission of traumatic, surgical, neurological, and cardiovascular conditions. Interdisciplinary consultation is an in‐built feature of this 24/7 service, and connects to a stroke unit, 4 intensive care units with extracorporeal life support and a chest pain unit to alleviate rapid triage of patients. The cardiologic department itself includes cardiac catheterization and electrophysiologic laboratories, a hybrid operating room, and telemetry units.

Definition of Study Groups, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For the present analysis risk‐stratification was performed according to the presence of AMI versus non‐AMI, and STEMI versus NSTEMI according to European guidelines.5, 8, 10, 12 STEMI was defined as a novel rise in the ST segment in at least two contiguous leads with ST‐segment elevation ≥2.5 mm in men <40 years, ≥2 mm in men ≥40 years, or ≥1.5 mm in women in leads V2–V3 and/or 1 mm in the other leads. Additional ECG criteria were new ST depression or inversion, T wave alterations, Q waves or new left bundle branch block. NSTEMI was defined as the presence of an acute coronary syndrome with a troponin I increase of above the 99th percentile of a healthy reference population in the absence of ST segment elevation, but persistent or transient ST segment depression, inversion or alteration of T wave, or normal ECG, in the presence of a coronary culprit lesion. The culprit lesion was defined as an acute complete thrombotic occlusion for STEMI and any relevant critical coronary stenosis for NSTEMI with the potential need for coronary revascularization either by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting. The presence of coronary culprit lesion was mandatory for both diagnoses of NSTEMI and STEMI. Evidence of regional wall motion abnormalities was also included in AMI diagnosis as far as available. Values of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were retrieved from standardized transthoracic echocardiographic examinations usually being performed before hospital discharge in survivors to assess realistic LVEF values beyond the acute phase of acute coronary ischemia during AMI. In minor part and only if available, earlier LVEF values assessed on admission or during intensive care were retrieved from patients who died already within the acute phase of AMI.

Overall exclusion criteria comprised patients without complete follow‐up data regarding mortality. Each patient was counted only once for inclusion when presenting with the first episode of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or SCA.

Study End Points

The primary prognostic end point was all‐cause mortality at long‐term follow‐up. Secondary end points were all‐cause mortality at 30 days, at index hospitalization, early cardiac death at 24 hours and first re‐PCI at long‐term follow‐up. Early cardiac death was defined as occurring <24 hours after onset of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or an assumed unstable cardiac condition on index admission.

Overall follow‐up period lasted until 2016. All‐cause mortality was documented using our electronic hospital information system and by directly contacting state resident registration offices (“bureau of mortality statistics”) across Germany. Identification of patients was verified by place of name, surname, day of birth and registered living address. Lost to follow‐up rate was 1.7% (n=48) regarding survival until the end of the follow‐up period.

Statistical Methods

Quantitative data are presented as mean±standard error of mean (SEM), median and interquartile range (IQR), and ranges depending on the distribution of the data and were compared using the Student t test for normally distributed data or the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric data. Deviations from a Gaussian distribution were tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Spearman's rank correlation for nonparametric data was used to test univariate correlations. Qualitative data are presented as absolute and relative frequencies and compared using the Chi2 test or the Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

Firstly, overall data of consecutive patients on admission are given for the entire unmatched cohort to present the real‐life character of healthcare supply at our institution in between 2002 and 2016. Here, multivariable Cox regression models were applied for the evaluation of the primary prognostic end point within the total study cohort for non‐AMI versus AMI, and in the AMI subgroup for NSTEMI versus STEMI. Then, multivariable Cox regression models were applied for the primary prognostic end point in the subgroups of non‐AMI, STEMI, and NSTEMI patients. Multivariable Cox regression models were adjusted for the following covariables: age, sex, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), prior heart failure, prior AMI, prior coronary artery disease (CAD), LVEF <35%, CPR, index AMI, overall presence of ICD, and index ventricular tachyarrhythmia (ie, VT/VF).

Secondly, propensity score matching was applied. There is a relevant and increasing demand from patients, clinicians and within the healthcare system in general for growing evidence from non‐randomized studies. There are simply too many medically relevant hypotheses, which will never be investigated within randomized controlled trials because of several reasons (ie, funding, recruitment, difficult study settings, high‐risk patients, etc). Therefore, we felt that the method of propensity matching would be a reasonable additional statistical method beside multivariable Cox regression models for the purpose of the present study evaluating the prognostic impact of non‐AMI/AMI and NSTEMI/STEMI in high‐risk patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on admission. These high‐risk patients are usually excluded from randomized controlled trials. In randomized controlled trials patients with or without a specific treatment would have a 50% chance to be treated and balanced measured and unmeasured baseline characteristics would be expected. However, patients with different disease entities may not be randomized in real‐life (such as non‐AMI versus AMI, or STEMI versus NSTEMI) because of different pathophysiologies and treatment recommendations. An observational study usually recruits consecutive real‐life patients without randomization resulting in varying chances between 0% and 100% to receive imbalances in baseline characteristics and treatments. Therefore, differences of outcomes in specific disease groups might be explained by heterogeneous distribution of baseline characteristics and applied therapies. To further reduce this selection bias, we used 1:1 propensity‐scores for AMI versus non‐AMI, respectively STEMI versus NSTEMI patients, to assemble matched and well‐balanced subgroups. One‐to‐one ratio for propensity score matching was performed including the entire study cohort and in AMI patients, applying a non‐parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model using AMI and STEMI patients as the dependent variables, respectively.13, 14

Propensity scores were created according to the presence of the following independent variables: age, sex, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), prior heart failure, prior AMI, prior CAD, LVEF, CPR, cardiogenic shock, index AMI, overall presence of ICD, and index ventricular tachyarrhythmia (ie, VT/VF). Based on the propensity score values counted by logistic regression, for each patient in the AMI group (STEMI group, respectively) one patient in the control group with a similar propensity score value was found (accepted difference of propensity score values <5%). Propensity scores were calculated for the following comparative analyses: (1) non‐AMI versus AMI (2) NSTEMI versus STEMI. Uni‐variable stratification was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method with comparisons between groups using univariable hazard ratios (HR) given together with 95% confidence intervals, according to the presence of AMI, STEMI, and NSTEMI within the propensity‐matched cohorts.

Follow‐up periods at 30 days defined short‐term and at 2.5 years defined long‐term follow‐up. Long‐term follow‐up period of 2.5 years accorded to the median survival time of AMI patients to guarantee complete follow‐up of at least 50% of patients. Patients not meeting long‐term follow‐up were censored.

The result of a statistical test was considered significant for P<0.05, P≤0.1 was defined as a statistical trend. SAS, release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS (Version 25, IBM Armonk, New York, USA) were used for statistics.

Results

Entire, Unmatched Real‐Life Cohort

In the entire, unmatched real‐life cohort including a total of 2813 high‐risk patients, the prevalence of AMI was 29%, of which 10% presented with STEMI and 19% with NSTEMI. Most patients were males. As shown in Table 1 (left columns), non‐AMI patients had higher rates of VT, were older, as well had higher rates of prior heart failure, prior ICD, dilative cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, LVEF <35% and overall ICDs (P<0.05). In contrast, AMI patients revealed higher rates of VF, early cardiac death, CPR, cardiogenic shock, CAD including multivessel CAD and prior coronary artery bypass grafting, PCI, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, statin and antiplatelet medication, whereas LVEF >55% was more common in AMI patients (P<0.05) (Table 1, left columns).Notably, patients with AMI‐related VT ≥48 hours after AMI onset (early cardiac deaths excluded) were associated with higher mortality compared with AMI‐related VT <48 hours already at 30 days (un‐matched cohort: 30 days, HR=2.289; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.028–5.047, P=0.040; 2.5 years, HR=2.661, 95% CI 1.469–4.820; P=0.001), irrespective of the presence of STEMI or NSTEMI (Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in the Unmatched Real‐Life Population

| Characteristic | AMI (n=825; 29%) | Non‐AMI (n=1986; 71%) | P Value | STEMI (n=276; 10%) | NSTEMI (n=549; 19%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria, n (%) | ||||||

| Ventricular tachycardia | 248 (30) | 1116 (56) | 0.001a | 81 (29) | 167 (30) | 0.752 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 443 (54) | 615 (31) | 0.001a | 156 (57) | 287 (52) | 0.249 |

| Early cardiac death | 286 (35) | 517 (26) | 0.001a | 84 (30) | 202 (37) | 0.070 |

| With VT | 49 (6) | 85 (4) | 0.060 | 11 (4) | 38 (7) | 0.092 |

| With VF | 108 (13) | 187 (9) | 0.004a | 35 (13) | 73 (13) | 0.805 |

| Without ventricular tachyarrhythmia | 134 (16) | 257 (13) | 0.021a | 39 (14) | 95 (17) | 0.244 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 612 (74) | 1368 (69) | 0.005a | 206 (75) | 406 (74) | 0.832 |

| Age, median (range) | 68 (19–100) | 68 (14–97) | 0.035a | 65 (25–91) | 69 (19–100) | 0.001a |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | ||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 482 (58) | 1078 (54) | 0.044a | 148 (54) | 334 (61) | 0.047a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 238 (29) | 513 (26) | 0.100 | 66 (24) | 172 (31) | 0.027a |

| Hyperlipidemia | 205 (25) | 515 (26) | 0.549 | 53 (19) | 152 (28) | 0.008a |

| Smoking | 283 (34) | 422 (21) | 0.001a | 112 (41) | 171 (31) | 0.007a |

| Cardiac family history | 75 (9) | 157 (8) | 0.298 | 26 (9) | 49 (9) | 0.815 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Prior heart failure | 113 (14) | 517 (26) | 0.001a | 22 (8) | 91 (17) | 0.001a |

| Prior CAD | 297 (36) | 792 (40) | 0.054 | 79 (29) | 218 (40) | 0.002a |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 164 (20) | 449 (23) | 0.111 | 41 (15) | 123 (22) | 0.010a |

| Preexisting ICD | 12 (1) | 256 (13) | 0.001a | 1 (0.4) | 11 (2) | 0.063 |

| Dilative cardiomyopathy | 0 (0) | 259 (13) | ··· | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· |

| Cardiogenic shock | 283 (34) | 284 (14) | 0.001a | 91 (33) | 192 (35) | 0.568 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 197 (24) | 613 (31) | 0.001a | 52 (19) | 145 (26) | 0.016a |

| Chronic kidney disease | 459 (56) | 987 (49) | 0.004a | 141 (51) | 318 (58) | 0.062 |

| Hyperkalemia | 28 (3) | 62 (3) | 0.709 | 4 (1) | 24 (4) | 0.029a |

| Hypokalemia | 36 (4) | 111 (6) | 0.184 | 10 (4) | 26 (5) | 0.460 |

| COPD/asthma | 69 (8) | 221 (12) | 0.028a | 13 (5) | 56 (10) | 0.007a |

| Stroke | 28 (3) | 55 (3) | 0.373 | 9 (3) | 19 (3) | 0.881 |

| Left ventricular function, n (%) | ||||||

| LVEF ≥55% | 169 (20) | 414 (21) | 0.830 | 61 (22) | 108 (20) | 0.415 |

| LVEF 54% to 35% | 219 (27) | 430 (22) | 0.005a | 80 (28) | 139 (25) | 0.260 |

| LVEF <35% | 165 (20) | 546 (27) | 0.001a | 48 (17) | 117 (21) | 0.184 |

| Not documented | 272 (···) | 596 (···) | 0.122 | 87 (···) | 185 (···) | 0.530 |

| Cardiac therapy at index, n (%) | ||||||

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 628 (76) | 878 (44) | 0.001a | 211 (76) | 417 (76) | 0.875 |

| In hospital | 270 (33) | 403 (20) | 0.001a | 90 (33) | 180 (33) | 0.959 |

| Out of hospital | 358 (43) | 475 (24) | 0.001a | 121 (44) | 237 (43) | 0.854 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | ||||||

| Coronary angiography, overall | 662 (80) | 882 (44) | 0.001a | 241 (87) | 421 (77) | 0.001a |

| Coronary artery disease | 652 (79) | 508 (26) | 0.001a | 238 (86) | 414 (75) | 0.001a |

| No evidence of CAD | 10 (1) | 374 (19) | 0.001a | 3 (1) | 7 (1.2) | 0.816 |

| 1‐vessel | 208 (25) | 144 (7) | 0.001a | 84 (30) | 124 (23) | 0.014a |

| 2‐vessel | 208 (25) | 148 (7) | 0.001a | 77 (28) | 131 (24) | 0.208 |

| 3‐vessel | 236 (29) | 216 (11) | 0.001a | 77 (28) | 159 (29) | 0.750 |

| CTO | 171 (19) | 154 (23) | 0.065 | 34 (14) | 120(29) | 0.001a |

| Prior CABG | 40 (5) | 156 (8) | 0.004a | 8 (3) | 32 (6) | 0.064 |

| Intracoronary thrombus | 121 (15) | 15 (0.8) | 0.001a | 62 (22) | 59 (11) | 0.001a |

| CPR during coronary angiography | 104 (13) | 38 (2) | 0.001a | 34 (12) | 70 (13) | 0.860 |

| PCI, n (%) | 549 (67) | 171 (9) | 0.001a | 223 (81) | 326 (59) | 0.001a |

| Target lesions, n (%) | ||||||

| RCA | 190 (23) | 74 (4) | 0.001a | 81 (29) | 109 (20) | 0.002a |

| LMT | 37 (4) | 16 (0.8) | 0.001a | 9 (3) | 28 (5) | 0.228 |

| LAD | 289 (35) | 72 (4) | 0.001a | 128 (46) | 161 (29) | 0.001a |

| LCX | 136 (16) | 40 (2) | 0.001a | 47 (17) | 89 (16) | 0.732 |

| RIM | 8 (1) | 7 (0.4) | 0.041a | 1 (0.4) | 7 (1) | 0.207 |

| Bypass graft | 8 (1) | 9 (0.5) | 0.108 | 2 (0.7) | 6 (1) | 0.611 |

| Sent to CABG | 27 (3) | 19 (1) | 0.001a | 4 (1) | 23 (4) | 0.037a |

| Patients discharged | 409 (50) | 1288 (65) | 0.001a | 153 (55) | 265 (48) | 0.052 |

| Overall ICDs, n (%) | 726 (56) | 112 (27) | 0.001a | 23 (15) | 89 (34) | 0.001a |

| Medication at discharge, n (%) | ||||||

| Beta‐blocker | 377 (92) | 977 (76) | 0.001a | 143 (93) | 234 (88) | 0.088 |

| ACE inhibitor | 326 (80) | 724 (56) | 0.001a | 123 (80) | 203 (77) | 0.368 |

| ARB | 22 (5) | 164 (13) | 0.001a | 8 (5) | 14 (5) | 0.981 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 31 (8) | 150 (12) | 0.020a | 13 (8) | 18 (7) | 0.522 |

| Digitalis | 27 (7) | 182 (14) | 0.001a | 4 (3) | 23 (9) | 0.015a |

| Amiodarone | 51 (12) | 208 (16) | 0.071 | 8 (5) | 43 (16) | 0.001a |

| ASA only | 55 (13) | 392 (30) | 0.001a | 9 (6) | 46 (17) | 0.001a |

| Clopidogrel only | 8 (2) | 38 (3) | 0.352 | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | 0.492 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 338 (83) | 136 (11) | 0.001a | 141 (92) | 197 (74) | 0.001a |

| Statin | 379 (93) | 643 (50) | 0.001a | 145 (95) | 234 (88) | 0.028a |

ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetyl salicylic acid; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CTO, chronic total occlusion; ICD; internal cardioverter defibrillator; LAD, left artery descending; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LCX, left circumflex; LMT, left main trunk; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; RIM, ramus intermedius; STEMI/NSTEMI, (non) ST segment myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Indicates statistical significance at P<0.05.

As shown in Table 1 (right columns) comparing STEMI with NSTEMI patients, the rates of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and early cardiac deaths were equally distributed. Cardiovascular risk profile was higher in NSTEMI patients, alongside with higher rates of prior heart failure, prior CAD, prior AMI, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, LVEF <55%, and overall ICDs (P<0.05). In contrast, STEMI patients revealed higher rates of coronary 1‐vessel disease and PCI commonly at the right coronary artery and left artery descending with higher rates of intracoronary thrombus compared with NSTEMI patients (P<0.05). Minor differences in statins and antiplatelet therapy due to modified regimens in selected patients during routine care (eg, in patients with increasing risk of bleeding or triple therapy) were present (Table 1 [right columns]).

Index PCI was only of prognostic benefit in AMI, respectively in STEMI patients (AMI: univariable HR 0.732, P=0.021; STEMI: univariable HR 0.425, P=0.003), whereas this was not seen in NSTEMI and non‐AMI patients (P>0.05) (data not shown).

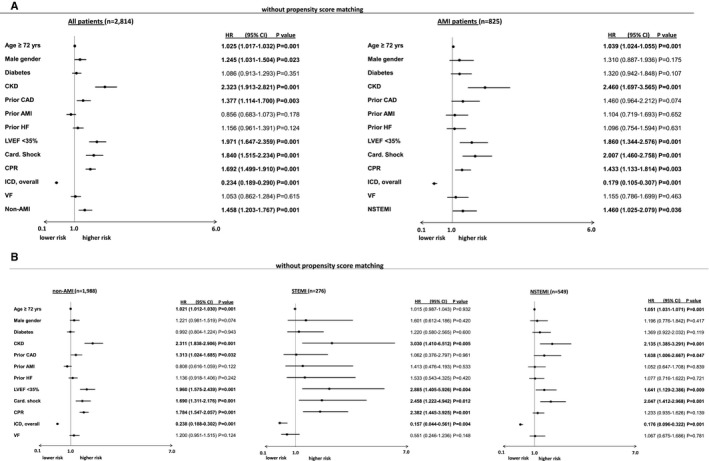

Multivariable Cox regression analyses within the entire, unmatched real‐life cohort revealed non‐AMI patients to be significantly associated with the primary end point of long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years (HR=1.458, 95% CI 1.203–1.767, P=0.001) (Figure 1A, left panel). In the AMI subgroup, the presence of NSTEMI was significantly associated with long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years (HR=1.460, 95% CI 1.025–2.079, P=0.036) (Figure 1A, right panel).

Figure 1.

A, Non‐AMI (left) as well as NSTEMI (right) were still associated with the primary end point of long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years after adjusting for several prognosis‐relevant factors within multivariable Cox regression models. B, Multivariable Cox regression analyses evaluating the prognostic impact of clinical factors on the primary end point of long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years. Left : Model in non‐AMI patients; middle: Model in STEMI patients; right: model in NSTEMI patients. NSTEMI indicates non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; AMI acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; Card. Shock, cardiogenic shock; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implanted cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Focusing on the subgroups of non‐AMI, NSTEMI, and STEMI patients (Figure 1B, left, middle, and right panels), multivariable Cox regressions revealed LVEF <35%, cardiogenic shock, and chronic kidney disease as the strongest predictors of long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years in all subgroups. Particularly in non‐AMI patients, age >72 years, prior CAD and CPR were significantly associated with the primary end point. In NSTEMI patients, age >72 years and prior CAD, but not CPR were associated with the primary end point. Contrastively in STEMI patients, additional CPR, but neither age nor prior CAD were associated with long‐term all‐cause mortality.

Propensity‐Matched Cohorts

After applying propensity‐score matching for the comparison of AMI versus non‐AMI patients (509 matched pairs) and STEMI versus NSTEMI patients (187 matched pairs) comparable subgroups with similar rates for age, sex, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, prior CAD, prior AMI, atrial fibrillation, LVEF, cardiogenic shock, CPR, and overall ICDs were achieved (Table 2, left and right columns).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics After Propensity Score Matching

| Characteristic | Non‐AMI (n=509; 50%) | AMI (n=509; 50%) | P Value | STEMI (n=187; 50%) | NSTEMI (n=187; 50%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria, n (%) | ||||||

| Ventricular tachycardia | 212 (42) | 182 (36) | 0.024a | 62 (33) | 62 (33) | 0.804 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 229 (45) | 267 (53) | 104 (56) | 110 (59) | ||

| Early cardiac death | 68 (13) | 60 (12) | 0.450 | 21 (11) | 15 (8) | 0.293 |

| With VT | 27 (5) | 20 (4) | 0.101 | 12 (6) | 3 (2) | 0.005 |

| With VF | 52 (10) | 35 (7) | 19 (10) | 7 (4) | ||

| Without VA | 68 (13) | 60 (12) | 15 (8) | 21 (11) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 391 (77) | 383 (75) | 0.345 | 149 (80) | 147 (79) | 0.799 |

| Age, median (range) | 68 (16–92) | 67 (19–100) | 0.358 | 64 (25–91) | 65 (19–100) | 0.649 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | ||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 307 (60) | 321 (63) | 0.367 | 107 (57) | 112 (60) | 0.600 |

| Diabetes | 147 (29) | 146 (29) | 0.945 | 45 (24) | 49 (26) | 0.633 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 140 (28) | 145 (29) | 0.727 | 43 (23) | 50 (27) | 0.402 |

| Smoking | 124 (24) | 203 (40) | 0.001a | 89 (48) | 80 (43) | 0.350 |

| Cardiac family history | 43 (8) | 54 (11) | 0.240 | 21 (11) | 19 (10) | 0.738 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Prior heart failure | 131 (26) | 99 (19) | 0.016a | 19 (10) | 28 (15) | 0.160 |

| Prior CAD | 221 (43) | 203 (40) | 0.252 | 52 (28) | 65 (35) | 0.147 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 127 (25) | 114 (22) | 0.338 | 27 (14) | 38 (20) | 0.133 |

| Preexisting ICD | 48 (9) | 10 (2) | 0.001a | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1) | 0.562 |

| Dilatative cardiomyopathy | 40 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.001a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· |

| Cardiogenic shock | 123 (24) | 141 (28) | 0.198 | 47 (25) | 44 (24) | 0.718 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 157 (31) | 148 (30) | 0.538 | 45 (24) | 44 (24) | 0.903 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 271 (53) | 270 (53) | 0.950 | 84 (45) | 90 (48) | 0.534 |

| Hyperkalemia | 40 (8) | 15 (3) | 0.855 | 2 (1) | 8 (4) | 0.054 |

| Hypokalemia | 29 (6) | 27 (5) | 0.783 | 5 (3) | 14 (8) | 0.034a |

| COPD/asthma | 54 (11) | 46 (9) | 0.400 | 9 (5) | 23 (12) | 0.012a |

| Stroke | 15 (3) | 22 (4) | 0.241 | 7 (4) | 7 (4) | 1.000 |

| LVEF, n (%) | ||||||

| LVEF ≥55% | 155 (31) | 155 (31) | 0.311 | 60 (32) | 66 (35) | 0.685 |

| LVEF 54% to 35% | 179 (35) | 201 (39) | 0.154 | 79 (42) | 72 (39) | 0.461 |

| LVEF <35% | 175 (34) | 153 (30) | 0.140 | 48 (26) | 49 (26) | 0.905 |

| Cardiac therapies at index, n (%) | ||||||

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 327 (64) | 346 (68) | 0.208 | 133 (71) | 136 (73) | 0.730 |

| In hospital | 149 (29) | 162 (32) | 0.376 | 58 (31) | 55 (30) | 0.735 |

| Out of hospital | 178 (35) | 184 (36) | 0.694 | 75 (40) | 81 (43) | 0.529 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | ||||||

| Coronary angiography overall | 270 (53) | 434 (85) | 0.001a | 171 (91) | 160 (86) | 0.075 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 163 (60) | 429 (99) | 0.001a | 187 (100) | 183 (98) | 0.988 |

| No evidence of CAD | 107 (40) | 5 (1) | 0.001a | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | |

| 1‐vessel | 43 (16) | 144 (33) | 0.001a | 66 (39) | 61 (38) | 0.635 |

| 2‐vessel | 50 (19) | 138 (32) | 0.001a | 59 (35) | 44 (28) | 0.119 |

| 3‐vessel | 70 (26) | 147 (34) | 0.001a | 46 (27) | 51 (32) | 0.594 |

| CTO | 56 (21) | 100 (23) | 0.475 | 23 (14) | 38 (24) | 0.016a |

| Prior CABG | 47 (17) | 30 (7) | 0.001a | 7 (4) | 12 (8) | 0.183 |

| Intracoronary thrombus | 6 (2) | 78 (18) | 0.001a | 50 (29) | 20 (13) | 0.001a |

| CPR during coronary angiography | 18 (7) | 39 (9) | 0.273 | 12 (7) | 13 (8) | 0.703 |

| PCI, n (%) | 60 (22) | 347 (80) | 0.001a | 171 (94) | 121 (76) | 0.001a |

| Target lesions | ||||||

| RCA | 26 (5) | 123 (24) | 0.001a | 59 (32) | 38 (20) | 0.013a |

| LMT | 6 (1) | 13 (3) | 0.105 | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 0.410 |

| LAD | 29 (6) | 187 (37) | 0.001a | 95 (51) | 60 (32) | 0.001a |

| RIM | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1) | 0.738 | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.082 |

| RCX | 14 (3) | 86 (17) | 0.001a | 33 (18) | 30 (16) | 0.679 |

| Bypass graft | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1) | 0.255 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Sent to CABG | 9 (2) | 23 (5) | 0.012a | 4 (2) | 9 (5) | 0.158 |

| Patients discharged | 293 (58) | 329 (65) | 0.021a | 134 (72) | 117 (63) | 0.061 |

| Overall ICDs, n (%) | 129 (44) | 98 (30) | 0.001a | 21 (16) | 29 (25) | 0.071 |

| Medication at discharge, n (%) | ||||||

| Beta‐blocker | 225 (77) | 302 (92) | 0.001a | 127 (95) | 109 (93) | 0.591 |

| ACE inhibitor | 172 (59) | 261 (79) | 0.001a | 109 (81) | 91 (78) | 0.484 |

| ARB | 31 (11) | 18 (6) | 0.017a | 8 (6) | 4 (3) | 0.388 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 16 (6) | 29 (9) | 0.107 | 11 (8) | 5 (4) | 0.203 |

| Digitalis | 44 (15) | 20 (6) | 0.001a | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 1.000 |

| Amiodarone | 45 (15) | 41 (13) | 0.296 | 6 (5) | 10 (9) | 0.188 |

| ASA only | 93 (32) | 48 (15) | 0.001a | 9 (7) | 18 (15) | 0.027a |

| Clopidogrel only | 2 (0.7) | 8 (2) | 0.083 | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 0.182 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 36 (12) | 260 (79) | 0.001a | 122 (91) | 87 (74) | 0.001a |

| Statin | 150 (51) | 299 (91) | 0.001a | 130 (97) | 108 (92) | 0.093 |

ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetyl salicylic acid; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CTO, chronic total occlusion; ICD; internal cardioverter defibrillator; LAD, left artery descending; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LCX, left circumflex; LMT, left main trunk; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; RIM, ramus intermedius; STEMI/NSTEMI, (non) ST segment myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT ventricular tachycardia.

Indicates statistical significance at P<0.05.

Specifically, in non‐AMI patients a slightly higher rate of VT remained after matching, as well as higher rates of prior heart failure, preexisting ICD, dilative cardiomyopathy, CAD, related PCI and pharmacological treatment, which were not included within the matching process (Table 2 left columns). In contrast, comparing STEMI with NSTEMI patients after matching, slightly different rates of coronary chronic total occlusions (CTO), intracoronary thrombus, PCI at the right coronary artery, and LAD and antiplatelet therapy were still seen (Table 2 right columns).

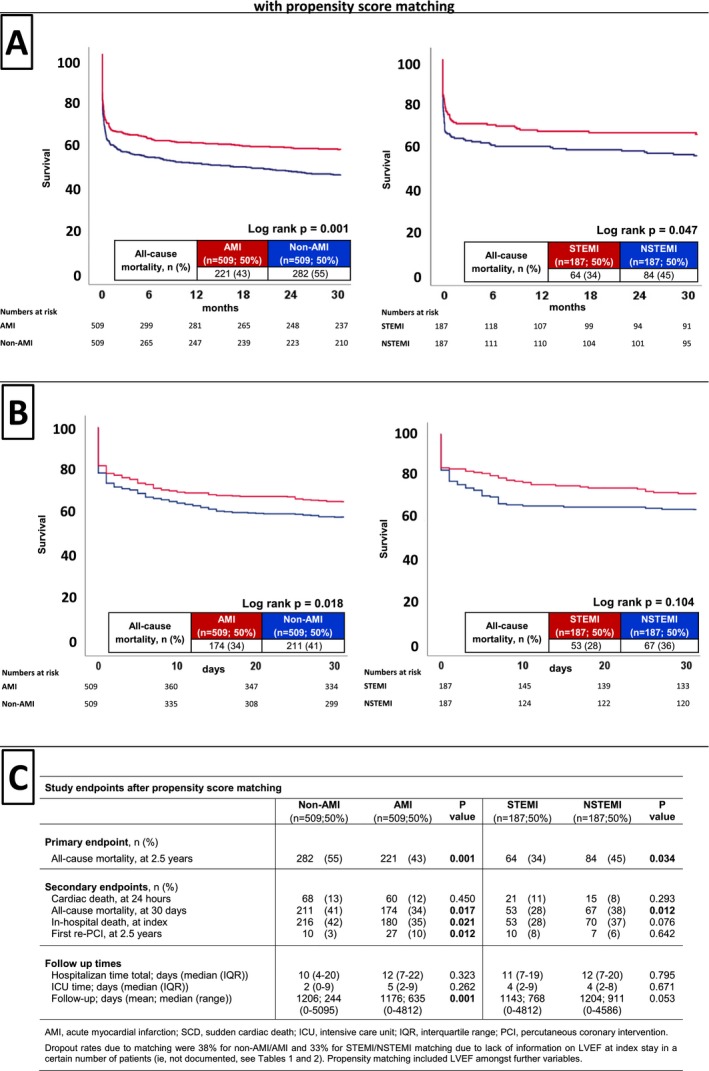

Figure 2A (left) illustrates the significantly adverse prognosis for the primary end point of long‐term all‐cause mortality in non‐AMI compared with AMI patients when presenting with concomitant ventricular tachyarrhythmias on hospital admission (primary end point, all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years: 55% versus 43%; log rank P=0.001; HR=1.349; 95% CI 1.028–1.536; P=0.026). Moreover, Figure 2B (right) illustrates adverse prognosis for the primary end point in NSTEMI compared with STEMI patients (primary end point, all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years: 45% versus 43%; log rank P=0.047; HR=1.372; 95% CI 0.991–1.900; P=0.057).

Figure 2.

After propensity score matching, Kaplan–Meier survival curves still demonstrated the association of non‐AMI (left) and NSTEMI (right) patients with the primary end point of long‐term all‐cause mortality at 2.5 years (A) and the secondary end point of all‐cause mortality at 30 days (B). C, Distribution of the primary and secondary end points after propensity score matching. NSTEMI indicates non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure 2B (left) shows significantly adverse prognosis for the secondary end point of short‐term all‐cause mortality at 30 days, which was already observed in non‐AMI compared with AMI patients (secondary end point, all‐cause mortality at 30 days: 41% versus 34%; log rank P=0.018; HR=1.257; 95% CI 1.028–1.536; P=0.026). Accordingly, in‐hospital death at index was significantly higher in non‐AMI compared with AMI patients, whereas rates of first re‐PCI were significantly higher in AMI patients (P<0.05). The latter secondary end points were not significantly different between STEMI and NSTEMI patients (Figure 2C).

Discussion

The present study evaluates the differences of prognostic outcomes depending on the presence of AMI, NSTEMI and STEMI in consecutive patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on admission.

This real‐world data suggests that high‐risk patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on admission reveal highest long‐term all‐cause mortality in the absence of AMI compared with AMI patients. Furthermore, NSTEMI patients were associated with higher long‐term all‐cause mortality compared with STEMI patients. Prognostic differences were demonstrated even within multivariable Cox regression models and after propensity‐score matching. Differences of mortality were observed at 30‐days and for in‐hospital mortality at index, especially in non‐AMI compared with AMI patients. Patients with AMI‐related VT were associated with higher mortality when occurring ≥48 hours compared with <48 hours of AMI onset.

The present study demonstrates that the strongest predictors of long‐term mortality across all analyzed subgroups (ie non‐AMI, AMI, NSTEMI, and STEMI patients) consisted in chronic kidney disease, LVEF <35%, CPR, and cardiogenic shock, whereas the presence of an ICD was consistently protective. Presumably, most patients died from progressive heart failure because of ischemic cardiomyopathy with concomitant chronic kidney disease, representing utmost impaired prognosis for patients after presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias in the presence of a cardiorenal syndrome.15, 16 Furthermore, patients presenting with cardiogenic shock are known to be at high risk and associated with adverse short‐ and long‐term prognosis.17, 18, 19 In the present study, non‐AMI patients and NSTEMI patients consisted of patients with pre‐existing heart failure with prior CAD, where index ventricular tachyarrhythmias represent disease progression and therefore may indicate the worse future outcome both at short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. In contrast, in STEMI patients the infarct itself may represent the index cause for ventricular tachyarrhythmias and heart failure was not present before. This is supported by the presented data revealing higher rates of preserved LVEF at index in STEMI patients, which may explain the better outcome of STEMI compared with NSTEMI patients. Slight differences of statin and dual antiplatelet therapies may have had further minor impact on mortality differences in STEMI versus NSTEMI patients.

Within the present study, at least 64% of patients in each subgroup underwent CPR related to ventricular tachyarrhythmias reflecting hemodynamic instability and cardiogenic shock. However, PCI rates were higher in AMI compared with non‐AMI patients (un‐matched: 83% [93% STEMI versus 77% NSTEMI] versus 19%; matched: 80% [94% STEMI versus 76% NSTEMI] versus 22%) alongside with a high rate of coronary multivessel disease in at least 50% and LVEF <35% in at least 30% of patients in each subgroup. These rates support the need for an invasive strategy by coronary angiography at index hospitalization to treat or exclude relevant CAD. Adequate timing of coronary angiography may not be drawn from the present study. However, it has recently been demonstrated that 30‐day mortality is increased by immediate multivessel PCI in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock and coronary multivessel disease compared with immediate PCI of the culprit lesion only.29, 30 The prognostic benefit of an immediate coronary angiography in patients presenting with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest and NSTEMI is currently evaluated within the prospective randomized controlled TOMAHAWK study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02750462), hypothesizing that an immediate coronary angiography may not be associated with a certain prognostic benefit in these high‐risk patients. Accordingly, within the present study index PCI was only of prognostic benefit in AMI, respectively STEMI patients, but not in NSTEMI and non‐AMI patients. Furthermore, AMI patients revealed a significantly higher rate of re‐PCI secondary to ventricular tachyarrhythmias. However, treatment of the most prognosis‐limiting comorbidities of heart failure and chronic kidney disease may take even more notice in non‐AMI and NSTEMI patients.

VF occurs mostly in the presence of acute myocardial ischemia, whereas VT represents a scar‐related substrate in the presence of prior heart failure due to ischemic cardiomyopathy, structural or inflammatory heart disease.8 Accordingly, international guidelines indicate emergency invasive coronary angiography in patients with acute heart failure or cardiogenic shock complicating AMI (class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).5, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In cardiogenic shock and STEMI, international guidelines recommend emergency coronary angiogram to revascularize acutely the potential coronary culprit lesion. However, this is almost based on consensus rather than evidence (class of recommendation I, varying level of evidence B‐C).5, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26 In NSTEMI patients with at least one high risk criterion, immediate invasive coronary angiography is recommended within 2 hours, because a poor short‐ and long‐term prognosis is assumed.7, 10, 27 In contrast, the management of patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest without ST elevation on the ECG is recommended to be individualized by differentiation of conscious from comatose survivors and a multidisciplinary approach to discriminate coronary from non‐coronary conditions.10

Presumably overall 6% of AMI patients develop VT or VF within 48 hours of acute ischemia usually before or during reperfusion therapy.8, 28 In acute STEMI non‐sustained VT may occur in 13% and VF in 3%.12 The present study revealed higher rates of VT <48 hours compared with VT ≥48 hours (24% versus 7%, excluding early cardiac deaths) in the subgroup of high‐risk AMI patients. The relationship between early VT/VF (<48 hours) and mortality remains controversial indicating increased 30‐day mortality without protracted risk at long‐term follow‐up especially for early monomorphic VT during AMI.28, 29 In contrast, the present study demonstrated significantly higher mortality for patients with AMI‐related VT ≥48 compared with <48 hours both at short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. Indication for coronary angiography in high‐risk AMI patients is based on expert consensus (class of recommendation I, level of evidence C). The present results, therefore, add knowledge to recent observational studies.12

Study Limitations

This observational and retrospective registry‐based analysis reflects a realistic picture of consecutive healthcare supply of high‐risk patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on hospital admission stratified into non‐AMI, AMI, NSTEMI, and STEMI. Lost to follow‐up rate regarding the evaluated end point of all‐cause mortality was minimal. Despite reasonable statistical evaluation implementing to balance this real‐life study population against confounding including multivariable Cox regression and propensity‐score matching results may not be overinterpreted, since propensity matching can only be performed for known patient characteristics. Absence of coronary angiography was mainly attributed to patients with prolonged hemodynamic instability and lethal outcome already at hospital admission (rate of early cardiac death: 30% in this cohort). Patients not surviving out‐of‐hospital CPR without transfer to the heart center were therefore not included in this study. The individual assessment of neurological outcomes and details towards out‐of‐hospital care in case of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest was documented incompletely and may have had further prognostic impact.

Conclusions

Non‐AMI patients were associated with higher all‐cause mortality compared with AMI patients, whereas NSTEMI was associated with higher mortality compared with STEMI in high‐risk patients presenting with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCA on admission.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the DZHK (Deutsches Zentrum fur Herz‐Kreislauf‐Forschung—German Centre for Cardiovascular Research).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Distribution of Infarct‐Related VTs, Unmatched Cohort

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010004 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010004.)

References

- 1. Anyfantakis ZA, Baron G, Aubry P, Himbert D, Feldman LJ, Juliard JM, Ricard‐Hibon A, Burnod A, Cokkinos DV, Steg PG. Acute coronary angiographic findings in survivors of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Am Heart J. 2009;157:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yousuf O, Chrispin J, Tomaselli GF, Berger RD. Clinical management and prevention of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116:2020–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001;104:2158–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Bottiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RS, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC, Kern KB, Laurent I, Longstreth WT Jr, Merchant RM, Morley P, Morrison LJ, Nadkarni V, Peberdy MA, Rivers EP, Rodriguez‐Nunez A, Sellke FW, Spaulding C, Sunde K, Vanden Hoek T. Post‐cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2008;118:2452–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neumann J‐F, Sousa‐Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet J‐P, Falk V, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ Seferović PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394/5079120. Accessed September 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Diego JM, Antzelevitch C. Ischemic ventricular arrhythmias: experimental models and their clinical relevance. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1963–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jobs A, Mehta SR, Montalescot G, Vicaut E, Van't Hof AWJ, Badings EA, Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Sciahbasi A, Reuter PG, Lapostolle F, Milosevic A, Stankovic G, Milasinovic D, Vonthein R, Desch S, Thiele H. Optimal timing of an invasive strategy in patients with non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2017;390:737–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Priori SG, Blomstrom‐Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez‐Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekval TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the Task Force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al‐Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Hlatky MA, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ, Page RL 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017. Avaialble at: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549. Accessed September 8, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction , Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasche P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferdinand D, Otto M, Weiss C. Get the most from your data: a propensity score model comparison on real‐life data. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braam B, Joles JA, Danishwar AH, Gaillard CA. Cardiorenal syndrome—current understanding and future perspectives. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Damman K, Valente MA, Voors AA, O'Connor CM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:455–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, Fuernau G, de Waha S, Meyer‐Saraei R, Nordbeck P, Geisler T, Landmesser U, Skurk C, Fach A, Lapp H, Piek JJ, Noc M, Goslar T, Felix SB, Maier LS, Stepinska J, Oldroyd K, Serpytis P, Montalescot G, Barthelemy O, Huber K, Windecker S, Savonitto S, Torremante P, Vrints C, Schneider S, Desch S, Zeymer U; Investigators C‐S . PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2419–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, Ferenc M, Olbrich HG, Hausleiter J, Richardt G, Hennersdorf M, Empen K, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, Hambrecht R, Fuhrmann J, Bohm M, Ebelt H, Schneider S, Schuler G, Werdan K; IABP‐SHOCK II Trial Investigators . Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1287–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeymer U, Vogt A, Zahn R, Weber MA, Tebbe U, Gottwik M, Bonzel T, Senges J, Neuhaus KL; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische K . Predictors of in‐hospital mortality in 1333 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); Results of the primary PCI registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Eur Heart J. 2004;25:322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Dzavik V, Buller CE, Aylward P, Col J, White HD; Investigators S . Early revascularization and long‐term survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;295:2511–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, Buller CE, Jacobs AK, Slater JN, Col J, McKinlay SM, LeJemtel TH. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, White HD, Dzavik V, Wong SC, Menon V, Webb JG, Steingart R, Picard MH, Menegus MA, Boland J, Sanborn T, Buller CE, Modur S, Forman R, Desvigne‐Nickens P, Jacobs AK, Slater JN, LeJemtel TH; SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock . One‐year survival following early revascularization for cardiogenic shock. JAMA. 2001;285:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mylotte D, Morice MC, Eltchaninoff H, Garot J, Louvard Y, Lefevre T, Garot P. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, and cardiogenic shock: the role of primary multivessel revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force M . 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gorjup V, Radsel P, Kocjancic ST, Erzen D, Noc M. Acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2007;72:379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hollenbeck RD, McPherson JA, Mooney MR, Unger BT, Patel NC, McMullan PW Jr, Hsu CH, Seder DB, Kern KB. Early cardiac catheterization is associated with improved survival in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest without STEMI. Resuscitation. 2014;85:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kern KB, Lotun K, Patel N, Mooney MR, Hollenbeck RD, McPherson JA, McMullan PW, Unger B, Hsu CH, Seder DB; INTCAR‐Cardiology Registry . Outcomes of comatose cardiac arrest survivors with and without ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: importance of coronary angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Farb A, Tang AL, Burke AP, Sessums L, Liang Y, Virmani R. Sudden coronary death. Frequency of active coronary lesions, inactive coronary lesions, and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92:1701–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhar‐Amato J, Davies W, Agarwal S. Ventricular arrhythmia after acute myocardial infarction: ‘The Perfect Storm’. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2017;6:134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hai JJ, Un KC, Wong CK, Wong KL, Zhang ZY, Chan PH, Lau CP, Siu CW, Tse HF. Prognostic implications of early monomorphic and non‐monomorphic tachyarrhythmias in patients discharged with acute coronary syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Distribution of Infarct‐Related VTs, Unmatched Cohort