Abstract

Efforts to further improve the clinical management of prostate cancer (PCa) are hindered by delays in diagnosis of tumours and treatment deficiencies, as well as inaccurate prognoses that lead to unnecessary or inefficient treatments. The quantitative and qualitative analysis of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) may address these issues and could facilitate the selection of effective treatment courses and the discovery of new therapeutic targets. Therefore, there is much interest in isolation of elusive CTCs from blood. We introduce a microfluidic platform composed of a multiorifice flow fractionation (MOFF) filter cascaded to an integrated microfluidic magnetic (IMM) chip. The MOFF filter is primarily employed to enrich immunomagnetically labeled blood samples by size-based hydrodynamic removal of free magnetic beads that must originally be added to samples at disproportionately high concentrations to ensure the efficient immunomagnetic labeling of target cancer cells. The IMM chip is then utilized to capture prostate-specific membrane antigen-immunomagnetically labeled cancer cells from enriched samples. Our preclinical studies showed that the proposed method can selectively capture up to 75% of blood-borne PCa cells at clinically-relevant low concentrations (as low as 5 cells/ml), with the IMM chip showing up to 100% magnetic capture capability.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most prevalent malignancy and one of the most fatal forms of cancer among men worldwide.1 A proportion of PCa patients initially treated for the localized disease will eventually present with the metastatic spread to distant sites, mostly to bones (e.g., ribs, pelvis, and spine). Such a condition is clinically diagnosed using various imaging modalities, typically following a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. In many cases, metastatic PCa is diagnosed too late and often continues to progress despite ongoing first-line androgen-deprivation therapy. This state is known as metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), which is a lethal form of PCa. Currently, an armamentarium of second-line therapies with proven survival benefits through tumour growth inhibition is available for mCRPC patients. Nevertheless, existing guidelines by which these treatment options are applied are almost empiric and follow a one-size-fits-all approach that is not entirely optimized to maximize the benefit and minimize the toxicity and cost for individual patients.2 Alternatively, predictive molecular biomarkers could be employed and longitudinally screened to identify particular drugs that maximally benefit each patient (i.e., precision oncology).3 However, performing multiple biopsies is either anatomically impractical (mostly due to bone tropism of PCa) or concomitantly poses a significant morbidity burden to patients (e.g., post-biopsy sepsis). Moreover, the innate molecular and cellular heterogeneity of tumours may not be captured by local biopsies.

Circulating tumour cells (CTCs), which are cancer cells that are actively or passively shed from primary or secondary tumours and enter the circulation, could be ideal specimens that can less-invasively and regularly be obtained from a blood sample and may provide the real-time single-cell level molecular data about the malignancy and its entirety in the form of a “liquid biopsy.” For example, it has been shown that mCRPC patients whose CTCs express the androgen receptor (AR) splice variant 7 develop resistance to the anti-androgen-axis agents abiraterone and enzalutamide, but benefit, for a time, from docetaxel and cabazitaxel therapies.4,5 However, resistance to these taxane-based chemotherapies also emerges in these patients at some point. While the exact mechanisms of resistance are not fully known, some molecular markers (e.g., βIII-tubulin or the upregulated expression of P-glycoprotein and MDR1) have been suggested to predict the efficacy of these compounds.6 Probing CTCs for expression of such markers would allow the physician to withdraw these highly toxic treatments and switch to another line of therapy. Thus, longitudinal screening of the molecular characteristics of CTCs can serve as both a surrogate endpoint for efficacy of current treatment and a predictive biomarker for selection of the next line of therapy. CTCs play a pivotal role in the hematogenous dissemination of malignancy and can be found in ∼75% of patients with metastatic PCa, allowing the early detection of metastatic foci before they are clinically detectable.2 Moreover, the CTC count at baseline or during therapy outperforms PSA and/or radiographic responses and correlates well with treatment efficiency and disease progression in PCa patients. Thus, while not as informative as their (epi)genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic signature, the frequency of CTCs in blood may also be used as a diagnostic marker for early detection of advanced PCa, a prognostic biomarker for overall survival, and a surrogate endpoint to evaluate the efficacy of anti-metastasis therapies.

Therefore, there is much interest in the isolation of CTCs from the peripheral blood of PCa patients. However, this is not a trivial task given the extreme scarcity of CTCs in the bloodstream [a few CTCs vs. >106 white blood cells (WBC) and >109 red blood cells (RBC) in a milliliter of cancerous blood].7 Isolation of such rare CTCs from a limited sample volume follows the Poisson distribution and therefore requires processing relatively large sample volumes (i.e., a few milliliters) with high sensitivity and selectivity at a practical throughput.8 A variety of techniques have been developed to meet these requirements.9–11 In brief, these techniques can be broadly categorized as physical properties- and molecular properties-based methods. CTC isolation using the former approach is based on differences in size, density, plasticity, or membrane capacitance of CTCs and blood cells. These approaches often require minimum sample preparation and can theoretically isolate CTCs regardless of their surface phenotype that could be altered during the disease progression exemplified by the loss of epithelial traits due to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is a defining episode of the metastatic cascade.12 Nevertheless, the efficiency of physical properties-based methods for CTC isolation could suffer, for example, from the non-specificity of size as a CTC biomarker (CTCs sometimes could be as small as WBCs) or variations in the compliance of CTCs due to alteration of the stiff cytoskeleton ironically caused by EMT.13 The increased plasticity of such purportedly more invasive CTCs would allow them to traverse through blood vessels while avoiding the sieving action of the pulmonary microvasculature and initiate secondary metastases. Thus, it is likely that such methods neglect a consequential subpopulation of CTCs with fundamental metastatic capabilities. Molecular properties-based methods are for the most part based on specific surface antigens that are expressed by CTCs and have been realized either directly on an antibody-coated capture bed or indirectly using immunomagnetic particles. However, depending on the target antigen adopted for isolation of putative CTCs, a positive selection method could be biased by isolating a certain subpopulation of CTCs. For instance, it is widely recognized that, as another consequence of EMT, the expression of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), an antigen widely targeted for CTC isolation, varies significantly among cancer cells.14 In summary, both physical properties- and molecular properties-based methods have their advantages and disadvantages, and it has been suggested that an optimal CTC isolation approach would perhaps be a combination of both.15

We report the design, fabrication, and preclinical testing of a microfluidic platform made by the cascade integration of (a) a multiorifice flow fractionation (MOFF) filter for size-based hydrodynamic enrichment of immunomagnetically labeled blood samples and (b) an integrated microfluidic magnetic (IMM) chip for isolation of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-immunomagnetically labeled prostatic CTCs from enriched samples. Rigorous examinations indicated that the proposed method can capture up to 75% of blood-borne PCa cells at clinically-relevant low concentrations (as low as 5 cells/ml), with the IMM chip showing up to 100% magnetic capture capability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PSMA-targeted microfluidic immunomagnetic isolation of CTCs

Theory

Given that all blood cells are either diamagnetic or very weakly magnetic,16 a magnetic force can be used to selectively isolate CTCs from blood provided their magnetic property is exclusively modified using immunomagnetic beads/particles that specifically bind to surface antigens on CTCs. When an immunomagnetically labeled blood sample is exposed to a non-uniform magnetic field, the field gradient forces labeled cells to migrate toward regions with the highest magnetic field density (i.e., B-field).17,18 This magnetic force depends in part on the intensity and gradient of the B-field that is produced by a magnetic source (e.g., an electromagnet, a permanent magnet, or some soft magnetic material that is itself magnetized by a primary source). The B-field intensity and its gradient drop quickly () as the distance () from the source increases, reducing the magnetic force exerted on labeled cells.18 However, taking advantage of microfluidics, the sample can be processed at a scale small enough to effectively exploit the strong magnetic force created in close vicinity (ideally several μm) of a magnetic source, thereby increasing the isolation sensitivity. Such an approach has previously been employed for CTC isolation by other researchers.19–23 In the majority of these works, the isolation is accomplished via magnetophoresis, where labeled cells are deflected within the flow in a microfluidic channel, either by an external magnetic source or a series of soft magnetic wires embedded inside the microchannel. These cells are then collected at a separate outlet for off-chip enumeration or characterization. In contrast, the approach used in this work captures CTCs at addressable locations on a chip that facilitates automated in situ analysis of cells using machine vision.

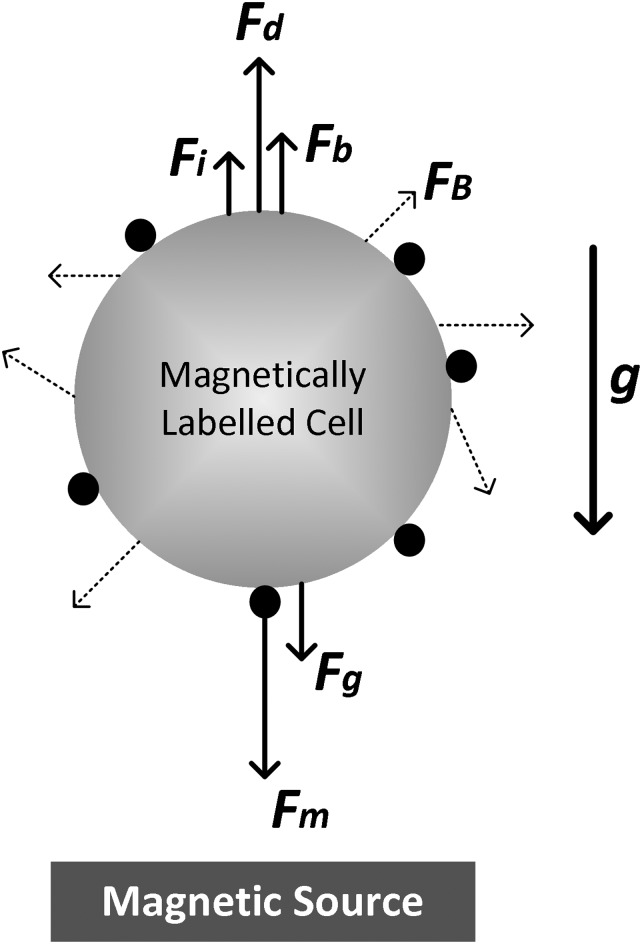

In general, immunomagnetic cell isolation is characterized by the interaction of several forces acting on labeled cells (see Fig. 1). These forces include diffusion or Brownian motion (), gravity (), buoyancy (), inertia (), Stokes’ drag (), and magnetism (). Except for and , the remaining forces normally do not significantly contribute to the dynamics of cell isolation in a microfluidic setting and can be safely ignored. The hydrodynamic drag and magnetic forces are defined, respectively, as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

FIG. 1.

A simplified 2D illustration of different forces acting on a magnetically labeled cell. Black circles represent magnetic beads/particles.

In Eq. (1), η, R, , and are the fluid viscosity, cell radius, cell velocity, and flow velocity, respectively. In Eq. (2), N is the number of magnetic beads (or particles) attached to a target cell, is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, is the difference between the volumetric magnetic susceptibility of a magnetic bead and that of the medium, is the volume of a magnetic bead, and is the B-field gradient. Considering these equations, the sensitivity and selectivity of a microfluidic immunomagnetic cell isolation approach are largely determined by the collective effect of the following:

-

(a)

the expression and specificity of target antigen and the quality of associated antibody (i.e., ),

-

(b)

the quality of immunomagnetic labeling process and beads (i.e., N, , ), and

-

(c)

the magnetic separation mechanism used to isolate labeled cells (i.e., ).

The performance of a microfluidic immunomagnetic approach is also governed by the - equilibrium. The controllable dynamics of microfluidic laminar flows and therefore the net force acting on labeled cells can be adjusted such that they are captured at a practical throughput as long as .

PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen)

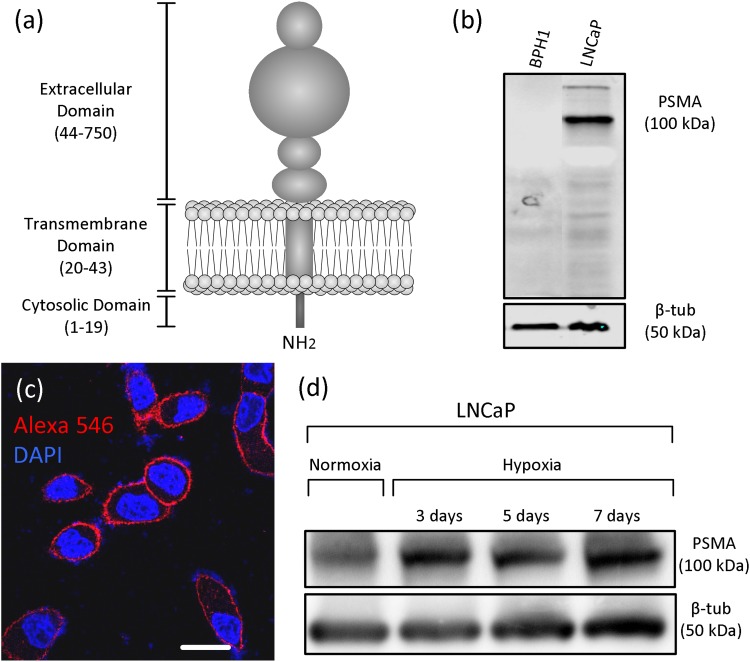

Among the key factors defining the sensitivity and selectivity of a microfluidic immunomagnetic CTC isolation approach are the expression and specificity of the target antigen and the quality of the associated antibody [i.e., N in Eq. (2)]. Ideally, a CTC antigen should specifically and exceedingly be expressed on the surface of all CTCs but almost absent on other circulating non-tumour or blood cells. PSMA (also known as folate hydrolase) has nearly such qualities for prostatic CTCs. Physiologically, PSMA contains a binuclear zinc site and acts as an enzyme [glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII)] on small molecule substrates, but its role in the function of prostate cells is not fully understood.24,25 Structurally, PSMA is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein with a large extracellular polypeptide chain [707 of 750 amino acids—see Fig. 2(a)]. PSMA is highly expressed on PCa cells and nonprostatic tumour neovasculature, and expressed at lower levels in other tissues including healthy prostate, kidney, liver, small intestine, and brain.24 It has been shown that PSMA has a role in prostate carcinogenesis and progression, and its expression increases in poorly differentiated androgen-independent PCa.24,27–31 Therefore, while its large extracellular domain and over-expression can increase the sensitivity of labeling, the fact that PSMA is dominantly observed on PCa cells and its expression level is associated with the malignancy level make it a highly specific antigen for selective isolation of prostatic CTCs [see Figs. 2(b) and 2(c)]. It should be noted that the majority of immunomagnetic CTC isolation systems, including the FDA-approved CellSearch® system, only capture CTCs that sufficiently express EpCAM. However, it has been shown that EpCAM expression is reduced in 29% of PCa samples and only 40%-70% of PSMA positive CTCs express variable levels of EpCAM.32,33 On the contrary, PSMA is upregulated in PCa cells, and its expression is not reduced by the phenotypical changes that occur due to EMT34 [see Fig. 2(d)]. Thus, in this study, PSMA was selected as the CTC antigen and was targeted using our highly efficient proprietary monoclonal antibody.

FIG. 2.

(a) The simplified molecular structure of PSMA. (b) Western blot analysis of the expression of PSMA on BPH1 cells (benign prostatic hyperplasia cell line) and LNCaP cells (PSMA positive human PCa cell line). (c) Immunocytochemistry analysis of PSMA expression (red) on LNCaP cells. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (d) Western blot analysis of the expression of PSMA on LNCaP cells under normoxia and hypoxia. PSMA expression on LNCaP cells is abundant in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Immunoblotting analyses were performed according to our previously established protocol. 26

Immunomagnetic labeling

Another major consideration in designing a microfluidic immunomagnetic CTC isolation approach is the immunomagnetic labeling method as well as the size and composition of magnetic beads [i.e., N, , and in Eq. (2)].9,17,35 In this study, two indirect labeling protocols based on the tetrameric antibody complex (TAC) technology36 and the streptavidin-biotin interaction were empirically evaluated. Detailed descriptions of each protocol are presented in Appendix 1 in the supplementary material.

IMM chip for isolation of immunomagnetically labeled cells

In addition to the target antigen, antibody, and labeling method, the performance of a microfluidic immunomagnetic CTC isolation approach heavily depends on the magnetic separation mechanism used to capture labeled cells [i.e., in Eq. (2) and the - equilibrium]. We propose a microdevice, the IMM (integrated microfluidic magnetic) chip, composed of a magnetic component and a microfluidic counterpart that are irreversibly bonded together.

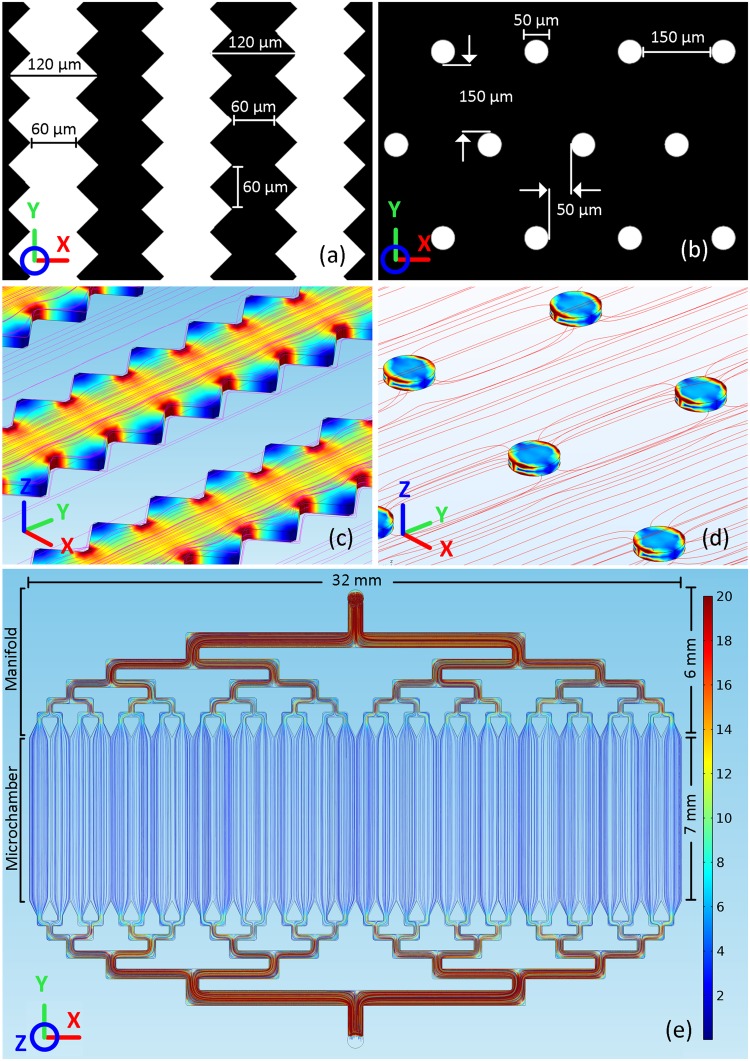

The magnetic component of the IMM chip is designed and fabricated based on the exceptional magnetic properties of Permalloy. A nickel-iron (80%-20%) alloy, Permalloy is a soft magnetic material with high permeability, allowing it to absorb field lines and become highly magnetized in the presence of a magnetic H-field. The magnetic component is composed of thousands of Permalloy-based magnetic microtraps that are fabricated on a glass substrate (see Appendix 2 in the supplementary material for the recipe). These microtraps are formed either based on our novel sawtooth design consisting of geometrically modified strips with numerous sawtooth dentations at both sides of each strip or using classical physically-separated individual micro-disks [see Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)]. The microtraps are magnetically “activated” when they are placed in an external magnetic H-field produced by a pair of permanent magnets. Consequently, the highest magnetic B-field spots will be formed either at the center of each sawtooth dentation or at opposing circular segments of each micro-disk [see Figs. 3(c) and 3(d)]. The strong field gradient produced by these B-field hot spots causes the microtraps to act almost as individual micromagnets. Therefore, a magnetically labeled cell would be pulled toward and captured on these B-field hot spots when it gets sufficiently close to the microtraps.37

FIG. 3.

(a) Sawtooth and (b) Micro-Disk microtrap designs. (c) and (d) COMSOL simulation of the external magnetic H-field lines (along the y-axis) and induced magnetic B-fields within Sawtooth and Micro-Disk microtraps. The high permeability of Permalloy structures provides a path with a lower magnetic reluctance, attracting magnetic field lines. As magnetic field lines pass through Permalloy structures, due to the narrower width of strips between sawtooth dentations or circular segments of micro-disks, magnetic field lines redirect and squeeze through these areas, causing a maximum B-field to be formed at these locations. (e) CFD simulation results showing uniform flow streamlines in the microchamber, which allows the sample to be distributed evenly over the underlying magnetic microtraps. The velocity numerical values are associated with the nominal flow rate (100 μl/min) at the chip inlet (top). The interaction between the fluid flow and microtraps located at the bottom of the microchamber were not taken into account in this model.

As illustrated in Fig. 3(e), the microfluidic component of the IMM chip is composed of a central microchamber and a flow distribution manifold and is fabricated in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (see Appendix 2 in the supplementary material for the recipe). The microchamber encloses and carries the sample over microtraps. The height of the microchamber is set to 55 ± 5 μm, as, based on finite element analysis (FEA) studies, the B-field gradient created by the microtraps can effectively manipulate labeled PCa cells (∼15-20 μm in diameter) within 35 μm. The flow distribution manifold is designed to deliver the sample across the microchamber with a uniform flow. Considering that the magnetic capture dynamics is governed by the - equilibrium, an uneven flow would translate into different values for and therefore the isolation sensitivity at different locations. The manifold uses a network of bifurcations to sequentially split the incoming flow and ultimately, through diffusers, deliver a uniform flow across the microchamber and over the microtraps. The flow uniformity primarily depends on the number and shape of diffusers. In general, increasing the number of diffusers improves the flow uniformity. However, this would increase the number of bifurcation generations, which, in turn, increases the size of the manifold and the chip along the y-axis. This dimension of the chip is, however, limited and dictated by the intensity of the external H-field that magnetizes the microtraps. A weak H-field would ultimately reduce the produced by the microtraps, decreasing the isolation sensitivity. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations concluded that for the 32 mm-wide microchamber of the IMM chip, 32 diffusers would provide an adequately uniform flow. The shape of diffusers can also affect the flow uniformity. For example, relatively longer diffusers provide better uniformity.38 The final shape of diffusers was chosen based on CFD simulations and experimental observations. More details regarding the manifold design can be found in Appendix 3 in the supplementary material.

MOFF filter for size-based hydrodynamic enrichment of immunomagnetically labeled blood samples

Experimental optimization of the immunomagnetic labeling protocols introduced earlier concluded that to ensure the efficient labeling of rare CTCs (defined, for example, as having at least one 2.8 μm bead per cell), an excessive number of magnetic beads/particles should be used (e.g., 1.5 × 107 beads/ml in case of 2.8 μm streptavidin-coated beads). Those beads that have not bound to any cells during the labeling process remain free in the sample and could be captured by the IMM chip intended to capture immunomagnetically labeled CTCs. This is because, by virtue of its working principle, the IMM chip is not magnetically selective, i.e., any magnetic entity exposed to the B-field gradient produced by the microtraps could potentially be captured. The capture and high-density accumulation of such an immense number of free magnetic beads on the rather small footprint of the IMM chip could affect its normal function and, more importantly, compromise the viability of captured CTCs and hamper their visual detection by fully burying them. Therefore, it is critical to minimize the number of free magnetic beads captured on the IMM chip. This is a crucial requirement for improving the overall performance of any microfluidic immunomagnetic cell separation system, particularly for rare cell separation, where detection of every single cell matters. One approach to address this issue is to reduce the absolute number of beads required for the efficient labeling of CTCs. This necessitates reducing the sample volume by lysing RBCs and getting rid of blood plasma (which together constitute ∼99% of blood volume) and resuspending remaining nucleated cells (including CTCs) in a much smaller volume. This approach has previously been used in some immunomagnetic methods, such as the CellSearch system. However, as shown later in the Results section, experiments using this approach proved that such an aggressive treatment of blood samples could result in a significant inadvertent target cell loss.

Alternatively, a filtration mechanism can be put in place to continuously remove free magnetic beads from whole blood samples after the immunolabeling process is completed and before labeled samples enter the IMM chip. The separation and sorting of particles is an established field of research in microfluidics, resulting in the development of a variety of techniques for this purpose over the past decade.39 In brief, continuous-flow microfluidic particle separation can be accomplished either passively based on the particle size and hydrodynamic interactions between particles, fluid flow fields, and microstructures, or actively using an external magnetic, ultrasonic, electric, or acoustic field to manipulate and specifically separate target particles. Given the definite size of the magnetic beads, MOFF, a size-based hydrodynamic method, deemed to be an effective yet inexpensive method for removing free beads from immunomagnetically labeled blood samples.

Theory

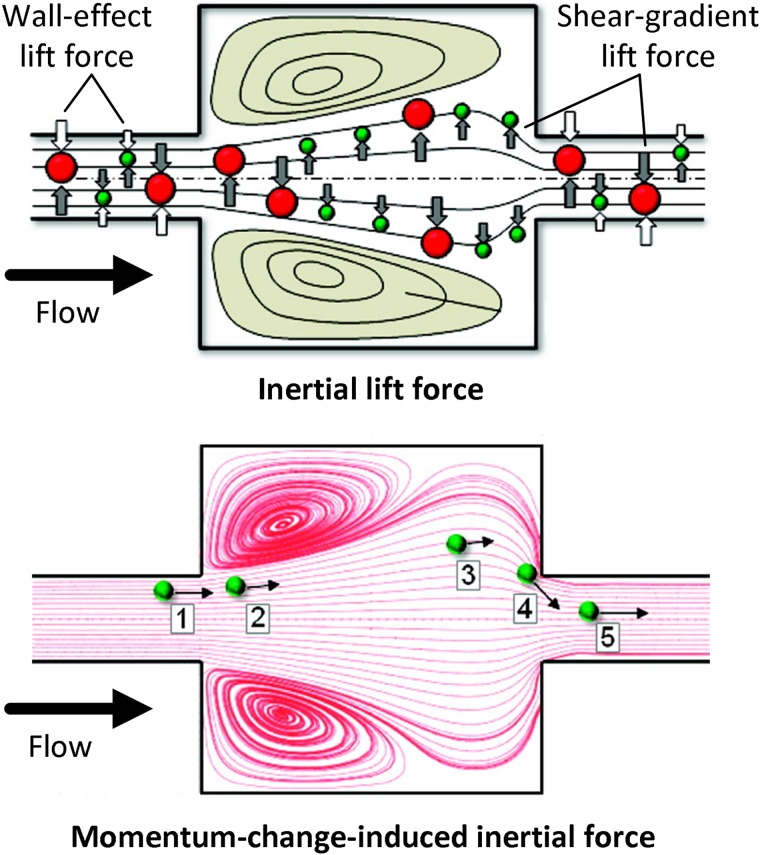

MOFF is a particle separation technique that is realized in a nonlaminar flow regimen in which the Reynolds number is large and inertial forces are dominant. Either independently or in combination with other cell separation techniques, this technique has previously been used for CTC isolation.40,41 Particle separation using MOFF results from the collective effect of two inertial forces acting on all particles in a microchannel: the inertial lift force and the momentum-change-induced inertial force (see Fig. 4).42,43 The inertial lift force itself is the net effect of two forces: a shear-gradient-induced lift force and a wall-effect-induced lift force. The former causes particles to migrate away from the center of a microchannel, while the latter repels particles away from microchannel walls. The other major inertial force responsible for particle separation via MOFF, i.e., the momentum-change-induced inertial force, is essentially caused by a mismatch between fluid and particle trajectories. Due to the nonlaminar nature of flow in MOFF, unlike the case of a laminar flow where particles follow the flow pattern due to a strong viscous drag force, the inertial force becomes the dominant factor in defining the particle migration. Therefore, the mismatch between fluid and particle trajectories can be induced by the specific geometry of a MOFF microchannel containing multiple expansion/contraction units.

FIG. 4.

An illustration of the inertial lift force (top) and the momentum-change-induced inertial force (bottom) applied on particles flowing in a MOFF microchannel. Reprinted with permission from Park and Jung, Anal. Chem. 81, 8280 (2009). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

While all particles flowing in a MOFF microchannel would be influenced by these forces, the behavior of each may be predicted by its particle Reynolds number , which, in addition to the microchannel dimensions and fluid properties, depends on the particle size and is defined as follows:

| (3) |

where is the hydraulic diameter of the microchannel, is the maximum flow velocity in the microchannel, is the fluid density, is fluid dynamic viscosity, and d is the particle diameter. Experimental studies by other researchers concluded that for , particles tend to concentrate close to the walls at both sides of the microchannel, whereas for particles with , they would focus close to the center of the microchannel.40,42

Design

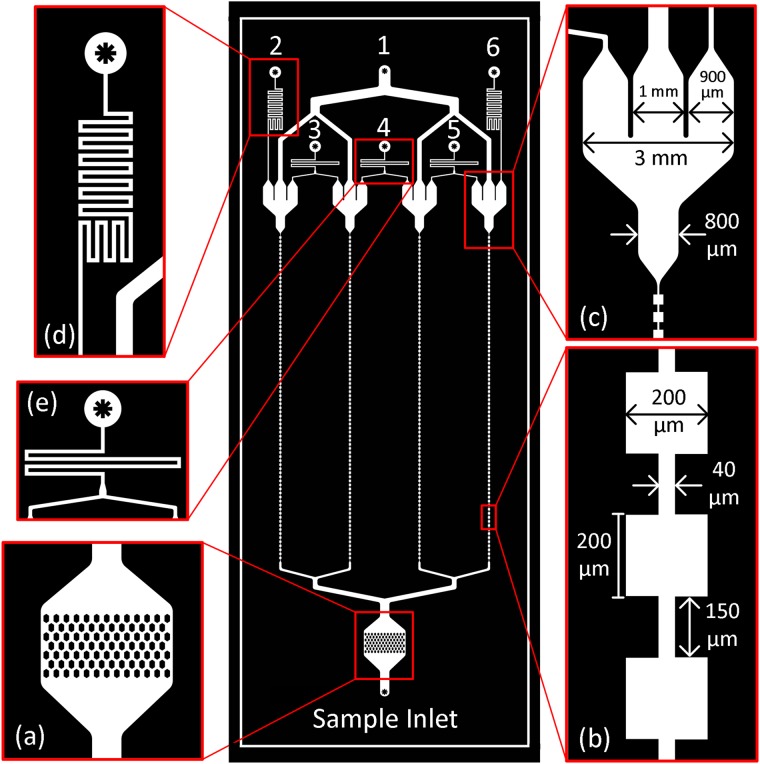

The MOFF filter designed for size-based hydrodynamic removal of free magnetic beads from immunomagnetically labeled blood samples is illustrated in Fig. 5. The filter (75 × 25 mm) is fabricated in PDMS using soft lithography and composed of four separate MOFF modules that are connected in parallel to improve the throughput and fed via a single inlet. A sieve-like structure composed of arrays of hexagon obstacles with a 100-μm clearance was designed at the inlet to prevent larger debris and blood clots from reaching and clogging the MOFF microchannels [see Fig. 5(a)]. Based on the designed parameters shown in Fig. 5(b), target CTCs and WBCs (>8 μm) would mostly be focused at the center while magnetic beads and a portion of RBCs (∼2.5-8 μm) would be concentrated close to walls of the MOFF microchannels. At the end of each microchannel is located an outlet structure with three exits [see Fig. 5(c)]. The middle exit would collect the enriched sample (including CTCs and WBCs), while the two lateral exits would collect filtered magnetic beads and RBCs. The enriched samples from all four modules converge at Outlet 1, which would be connected to the IMM chip’s inlet. Outlets 2-6 remove free magnetic beads and RBCs. The hydraulic resistance values were designed to collect set proportions of the fluid at each exit and account for the hydraulic resistance of the downstream IMM chip [see Figs. 5(d) and 5(e)]. Further details regarding the design can be found in Appendix 4 in the supplementary material.

FIG. 5.

A schematic of the MOFF filter (middle) and its different components.

RESULTS

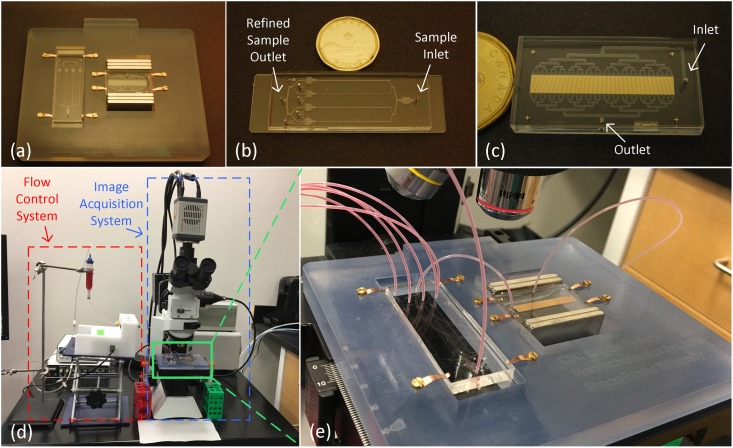

The microfluidic platform composed of the IMM chip and the MOFF filter, as well as the experimental setup, is depicted in Fig. 6. Additional details about the setup, macro-to-micro interfacing, and sample preparation is presented in Appendix 5 in the supplementary material. LNCaP cells were selected as the target PCa cell for characterization experiments. LNCaP cells are androgen-sensitive PCa cells that mimic the specific in vivo characteristics of PCa cells and are extensively used in PCa research.44 The cells were retrovirally infected prior to experiments to express green fluorescent protein (GFP), which was later utilized to detect and confirm their identity on the IMM chip.

FIG. 6.

(a) The microfluidic platform consists of (b) the MOFF filter (75 × 25 mm) and (c) the IMM chip (40 × 22 mm). (d) The experimental setup. (e) Close view of the platform. The sample first enters the MOFF filter, whose refined sample outlet is connected to the IMM chip’s inlet via a short piece of tubing. Extra magnetic beads and RBCs removed by the MOFF filter are collected at five different outlets. The two chips are placed in a custom-built 3D-printed adaptor that homes a pair of grade N52 NdFeB magnet stacks to create an external magnetic field in the desired direction that magnetically activates the microtraps within the IMM chip. The platform itself is mounted on a microscope stage for in situ visual analysis purposes.

It should be noted that for some experiments, as further clarified in the corresponding experimental procedure illustrations, LNCaP cells that had already been immunomagnetically labeled were seeded in buffer or blood samples. This allowed us to solely study the capture performance of the IMM chip or the entire platform without including another variable, i.e., the immunomagnetic labeling status of LNCaP cells.

IMM chip characterization

A series of experiments was designed and carried out to fully characterize the capture performance of the IMM chip first. The objective of the first set of these experiments was to compare the isolation sensitivity of the two microtrap designs (i.e., Micro-Disk vs. Sawtooth). LNCaP cells were immunomagnetically labeled using streptavidin-coated 2.8 μm beads and suspended in the buffer solution [1% w/v bovine serum albumin (BSA) + 3 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] at different concentrations and processed at an empirically optimized nominal flow rate of 100 μl/min [see Fig. 7(a)]. The isolation sensitivity was measured by the recovery rate defined as the ratio of the number of captured LNCaP cells on the chip to the number of LNCaP cells initially seeded in the sample. The recovery rates for the Micro-Disk and Sawtooth designs were 93.50 ± 4.44% and 98.65 ± 1.81%, respectively [see Figs. 7(b) and 7(c)]. A two-tailed T-test indicated that, compared to the classic Micro-Disk design, our novel Sawtooth design offers better isolation sensitivity (p ≤ 0.01). Therefore, it was utilized in devices used in subsequent experiments.

FIG. 7.

(a) The experimental procedure for measuring the isolation sensitivity of Sawtooth and Micro-Disk microtrap designs. (b) Isolation sensitivity of Sawtooth and Micro-Disk designs at different concentrations (n = 3 for each concentration). Error bars represent the standard deviation. (c) Regression analysis of isolation sensitivity. The plot shows the number of LNCaP cells seeded versus number of LNCaP cells recovered. (d) and (e) Bright-field and fluorescence images of two LNCaP cells captured on a Micro-Disk structure. (f) and (g) Bright-field and fluorescence images of a single LNCaP cell captured on a Sawtooth structure. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

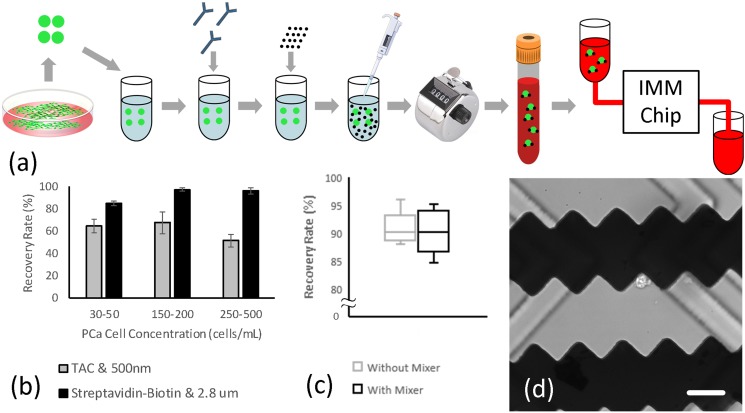

The next set of experiments was primarily performed to compare the two immunomagnetic labeling methods explained earlier. There are more than a billion blood cells in a milliliter of whole blood, and the secondary objective of these experiments was to study how blood cells would affect the isolation sensitivity. LNCaP cells were immunomagnetically labeled and seeded in blood samples from healthy rats at different concentrations. The samples were diluted (1:2) with the buffer solution and processed at the nominal flow rate. Figure 8 summarizes the experimental procedure and results. The recovery rates associated with (i) the TAC technology and 500 nm particles and (ii) the streptavidin-biotin interaction and 2.8 μm beads were 61.14 ± 9.82% and 92.69 ± 6.32%, respectively. Therefore, the latter labeling method was confirmed and used in following experiments. Using this method, the isolation sensitivity at a very low LNCaP cell concentration (5 cells/ml) was also studied (n = 5), which indicated that the IMM chip can recover 87.50 ± 9.12% of immunomagnetically labeled LNCaP cells seeded in blood samples.

FIG. 8.

(a) The experimental procedure for evaluating the effect of the immunomagnetic labeling methods, blood cells, and the embedded herringbone mixer on isolation sensitivity. (b) Isolation sensitivity associated with each immunomagnetic labeling method at different LNCaP cell concentrations (n = 3 for each concentration). Error bars represent the standard deviation. (c) Isolation sensitivity of devices with and without an embedded herringbone mixer (n = 5 for each type). (d) A bright-field image showing an LNCaP cell captured on the microtrap and embedded herringbone grooves on the inner surface of the microchamber. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

The vast number of blood cells in a sample could block the physical interaction of the target cancer cells and microtraps in the crowded microchamber environment. Moreover, given the small Reynolds number associated with the nominal flow rate by which samples are processed through the IMM chip, the flow within the microchamber is highly laminar. Cancer cells flowing within these laminar streamlines will be pulled toward the microtraps only if . Since the PSMA expression may not be equal on all target cells, some cells would not adsorb and carry enough magnetic beads to experience enough magnetic pull when they flow over the microtraps. To address this issue, the - balance can be altered in favour of by breaking the laminar flow streams and inducing an exaggerated diffusive movement of all cells inside the microchamber, allowing target cancer cells, including those with less magnetic bead load, to get closer to the microtraps and experience a larger . To this end, a passive herringbone mixer was designed and implemented in the upper surface of the microchamber to increase the diffusive movement of cells when they arrive at the magnetic microtraps bed area.45,46 See Appendix 6 in the supplementary material for more details regarding the design and fabrication of the mixer. To study how this mixer could affect the isolation sensitivity, the performance of devices with and without a mixer was experimentally evaluated, where the recovery rates were 90.27 ± 4.04% and 90.81 ± 3.03%, respectively [see Figs. 8(c) and 8(d)]. A two-tailed T-test concluded that there is no significant difference in the recovery rates of the two designs (p = 0.82). While the use of the herringbone mixer did not affect the isolation sensitivity, it caused some blood cells or LNCaP cells to be trapped inside the mixing grooves. Moreover, the grooves sometimes disturbed the visual analysis of captured cells at higher magnifications. As such, it was concluded that a herringbone mixer would not have a significant advantage and was not included in the final design.

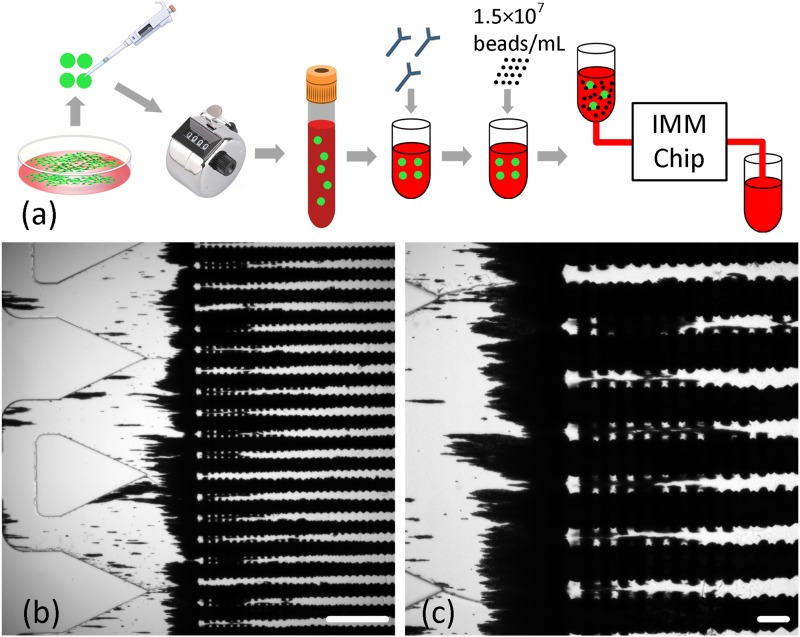

Once the microtrap design, immunomagnetic labeling method, and microchamber design were experimentally analyzed and confirmed, the next set of experiments was conducted to evaluate the independent performance of the finalized IMM chip in capturing LNCaP cells from spiked blood samples that mimic clinical blood samples [see the experimental procedure in Fig. 9(a)]. Prior to these experiments, the antibody and magnetic beads concentrations were optimized by titration to achieve efficient labeling of LNCaP cells spiked in whole blood samples using the minimum magnetic bead concentration. The labeled spiked blood samples (5-50 cells/ml) were processed through the IMM chip as explained before. In all trials (n = 5), 0%-15% of LNCaP cells were detectable under the microscope, which, as indicated earlier, was primarily due to nonspecific capture and accumulation of free magnetic beads on the chip. These extra beads completely buried the majority of captured cells, quenching their fluorescence signals and preventing visual detection under the microscope [see Figs. 9(b) and 9(c)].

FIG. 9.

(a) The experimental procedure for isolating LNCaP cells from spiked blood samples using the IMM chip in a standalone setting. Unlike previous experiments, LNCaP cells were first seeded in a blood sample and the spiked sample was then immunomagnetically labeled. (b) and (c) Nonspecific capture and accumulation of vast numbers of free unbound magnetic beads on the IMM chip prevented visualization of captured cells. Scale bars in (b) and (c) represent 500 μm and 100 μm, respectively.

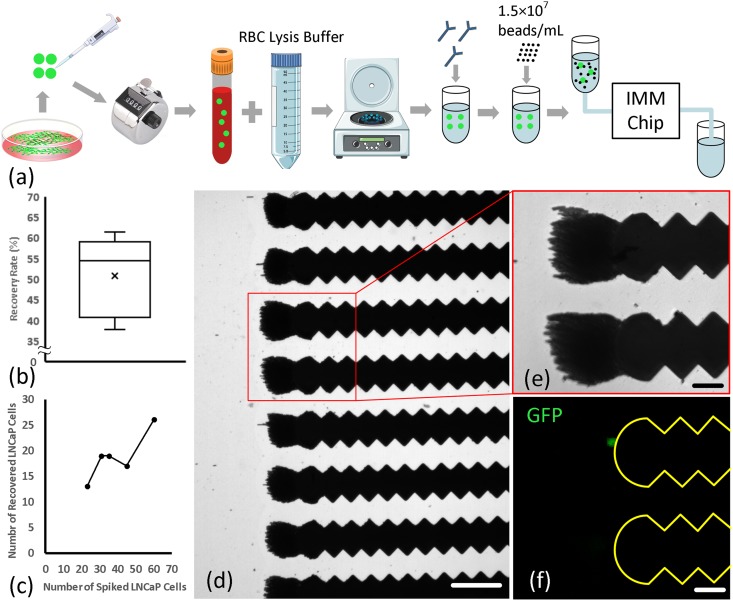

To reduce the absolute number of magnetic beads needed to efficiently label LNCaP cells, the sample volume was reduced by lysing RBCs and discarding blood plasma, and resuspending remaining nucleated cells in a smaller volume (e.g., 300 μl), as illustrated in Fig. 10(a). As expected, reducing the total number of magnetic beads enabled the visualization of captured cells under the fluorescence microscope. We assumed that the low recovery rate (51 ± 9.75%) associated with lysed blood samples might have been caused mainly by pre-processing of samples (i.e., lysing, centrifuging, and pipetting) and not the failure to visually detect the cells caused by capture and accumulation of a much smaller number of magnetic beads on the chip. To confirm this assumption, immunomagnetically labeled LNCaP cells were seeded in a solution polluted with the same number of magnetic beads used for immunomagnetic labeling of lysed blood samples, and this sample was processed under the same condition. Of the 11 LNCaP cells originally seeded in the sample, 9 (∼82%) cells were detected on the chip. This confirmed the assumption that the low recovery rate associated with lysed spiked blood samples was, for the most part, caused by inadvertent cell loss due to relatively harsh pre-processing of blood samples.

FIG. 10.

(a) The experimental procedure for isolating LNCaP cells from spiked and lysed blood samples. (b) Isolation sensitivity of the IMM chip for spiked and lysed blood samples (n = 5). (c) Number of LNCaP cells originally spiked in blood versus number of LNCaP cells captured. (d) A view of a portion of the IMM chip showing captured magnetic beads. Note the pronounced reduction in the number of beads on the chip, which allowed visualization of captured cells. Scale bar represents 150 μm. (e) and (f) Magnified views of microtraps with a captured LNCaP cell. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Platform characterization

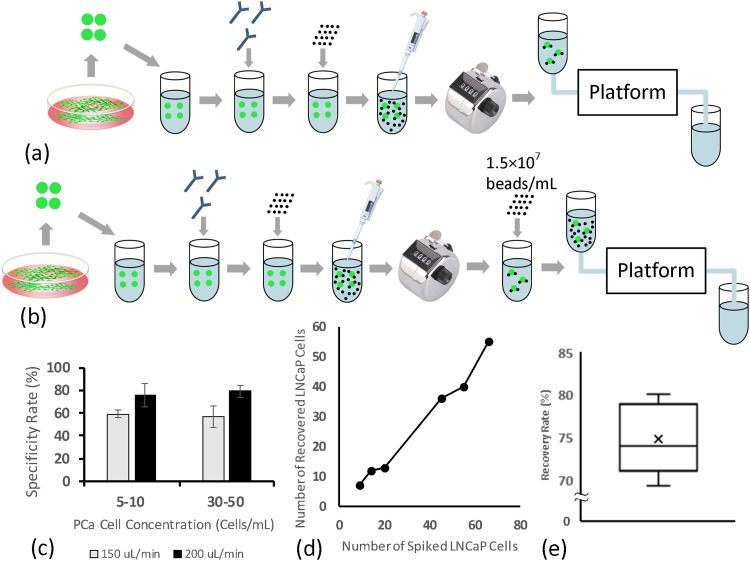

As a more practical approach to address the issue of nonspecific capture and accumulation of free magnetic beads on the IMM chip, the MOFF filter was employed upstream of the chip to refine immunomagnetically labeled blood samples by continuously removing free magnetic beads. The refined “bead-free” sample then entered the IMM chip, where LNCaP cells were captured. The specificity and sensitivity of the MOFF filter for removing free magnetic beads from labeled samples were experimentally evaluated first. The filtration specificity is defined as the ability of the MOFF filter to retain target cancer cells in the refined sample and, similar to isolation sensitivity, is quantified by the ratio of the number of captured LNCaP cells on the IMM chip to the number of LNCaP cells initially seeded in the sample. The filtration sensitivity refers to the ability of the MOFF filter to remove free beads from immunomagnetically labeled samples and can be measured as the ratio of the number of beads removed from the labeled sample to the number of beads initially added to the sample during the immunomagnetic labeling process. Figure 11 outlines the experimental procedures and summarizes the results of these experiments. To assess the filtration specificity, immunomagnetically labeled LNCaP cells were seeded in the buffer solution (5-50 cells/ml), and the samples were processed at two different flow rates (150 and 200 μl/min). The specificity rates were 58 ± 6.33% and 77 ± 7.57%, respectively. These results confirmed earlier qualitative observations that the best performance of the MOFF filter is obtained when the sample is processed at 200 μl/min. To assess the filtration sensitivity and its effect on the overall recovery rate, immunomagnetically labeled LNCaP cells were seeded in buffer solutions (5-20 cells/ml) that were then polluted with magnetic beads at an average concentration corresponding to optimized labeling protocol for streptavidin-coated 2.8 μm beads. While it was not possible to numerically measure the efficiency of the MOFF filter to remove magnetic beads, it was observed that the number of magnetic beads that had not been removed by the filter and had made it to and been captured on the IMM chip was not high enough to bury captured cells and prevent them from being visually detected. The recovery rate was 74.7 ± 4.24%, confirming that the visual detection of captured LNCaP cells was not significantly affected by the capture and accumulation of unfiltered magnetic beads.

FIG. 11.

(a) The experimental procedure for measuring the specificity of the MOFF filter. (b) Experimental procedure for measuring the sensitivity of the MOFF filter. (c) The specificity rate (as defined in the text) of the MOFF filter at different LNCaP cell concentrations and flow rates (n = 6 for each case). Error bars represent the standard deviation. (d) Number of LNCaP cells initially seeded versus number of LNCaP cells captured at 200 μl/min. (e) Recovery rate of labeled LNCaP cells from samples polluted with ∼1.5 × 107 beads/ml to assess the filtration sensitivity (n = 5).

Lastly, after studying the performance of individual components of the platform (i.e., the IMM chip and the MOFF filter), to assess the performance of the entire system and fully simulate the isolation of prostatic CTCs from clinical blood samples, a number of spiked blood experiments was conducted. As shown in Fig. 12(a), healthy rat blood samples were spiked with LNCaP cells at clinically relevant low concentrations (<20 cells/ml). The blood samples were then immunomagnetically labeled according to the optimized protocol, diluted (1:5), and processed at 200 μl/min. The results are summarized in Fig. 12. The recovery rate was 70 ± 3.34%, which is a function of several parameters, notably the immunomagnetic labeling efficiency, the sensitivity and specificity of the MOFF filter, and the magnetic capture efficiency of the IMM chip.

FIG. 12.

(a) The experimental procedure for isolating LNCaP cells from spiked blood samples using the platform. (b) Isolation sensitivity of the platform (n = 5). (c) Number of LNCaP cells originally spiked in blood versus number of LNCaP cells captured. (d) and (e) Magnified views of a captured LNCaP cell on tip of a Permalloy structure. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

We experimentally investigated and optimized three main factors governing the performance of the microfluidic immunomagnetic CTC isolation approach proposed in this study. First, PSMA, a transmembrane protein with a large extracellular domain whose expression is restricted to PCa cells in the circulation and increases with PCa aggressiveness was studied and selected as the target antigen for immunomagnetic labeling of prostatic CTCs, and was targeted using our highly efficient proprietary antibody.

Next, two common immunomagnetic labeling methods, i.e., the TAC technology and 500 nm dextran-coated particles vs. the streptavidin-biotin interaction and 2.8 μm streptavidin-coupled beads, were empirically evaluated. The results proved that the relatively smaller magnetic force associated with the overall low magnetic particle load per cell (mostly due to the small size of particles) makes the former approach suboptimal for a continuous-flow microfluidic approach. This is mainly because in such approaches, moving cells within the chip are exposed to the B-field for a short period of time (e.g., <5 s in case of the IMM chip). If they are not captured during this limited exposure, they will be missed. Thus, relatively higher magnetic forces are generally needed for continuous-flow microfluidic approaches.

Finally, we thoroughly studied the performance of the IMM chip developed to capture putative CTCs. Initial analysis of the IMM chip showed that it can capture up to 100% of immunomagnetically labeled cells at very low concentrations. This confirmed the superior performance of the IMM chip as the magnetic separation mechanism, which is the most instrumental element of any immunomagnetic cell separation approach. The proposed magnetic separation principle in the IMM chip is so effective that only a single 2.8 μm bead was needed for an LNCaP cell to be captured once it reached the magnetic microtrap bed. Comparing the isolation of LNCaP cells from buffer and blood samples showed that blood cells slightly affect the recovery rate, either physically or physiologically. Since using the herringbone mixer, which improves the physical interaction of cells and magnetic microtraps located at the bottom of the microchamber, did not significantly change the recovery rate, it can be assumed that the loss of target cancer cells in blood samples may have resulted mainly from the phagocytotic action of macrophages in healthy rat blood samples. Indeed, we occasionally observed LNCaP cell fragments or LNCaP cells being attacked by macrophages (data not shown). For blood samples, due to the high rate of shear stress experienced by all cells in the microchamber, the non-specific adhesion of blood cells on the IMM chip was generally negligible, making the proposed strategy highly selective. It was also noticed that when they are labeled with 2.8 μm magnetic beads, at least 85% of captured PCa cells on the chip were on the three first rows of microtraps nearest to the diffusers. Moreover, in some cases, PCa cells were captured on the tip of Permalloy strips. The remaining cells were distributed across the chip at different locations. Given the working principle of the IMM chip, this can be explained as follows: PSMA is highly expressed by most PCa cells. Thus, the majority of cells were labeled with a sufficiently high number of magnetic beads, rendering a strong magnetic pull that overcomes the hydrodynamic drag force on cells within a few hundred microns of their journey in the microchamber. For the remaining cells, however, the magnetic load may not be as high. As such, it takes more time for the magnetic force to gradually pull the cells downward.

The performance of the IMM chip for isolating LNCaP cells from spiked blood samples that simulate clinical blood samples from cancer patients was also evaluated in a standalone setting. Our titration studies had previously shown that the efficient immunomagnetic labeling of LNCaP cells in spiked whole blood samples requires an excessive number of magnetic beads (1.5 × 107 beads/ml in case of 2.8 μm streptavidin-coated beads). As expected, when the sample was processed through the IMM chip, not only labeled LNCaP cells but also unbonded free magnetic beads were captured on magnetic microtraps, effectively burying a majority of captured cells, preventing them from being visualized and detected (<15% of LNCaP cells were visually detectable). While reducing the sample volume and using a significantly smaller number of magnetic beads almost eliminated this issue, the relatively harsh treatment of blood samples resulted in a considerable rate of inadvertent cell loss and reduced the recovery rate up to 40%, diminishing the impressive magnetic capture capability of the IMM chip.

To fundamentally address this problem, these free extra magnetic beads should be removed from the sample after the immunomagnetic labeling process and before it is exposed to the magnetic separation mechanism. However, except for a single study,50 this issue has rarely been addressed in other works in which immunomagnetic methods have been used for CTC isolation.20,23,51–54 The MOFF filter developed in this work was able to consistently remove the majority of free magnetic beads (∼80%) while retaining ∼85% of target cancer cells (see Video S1 in the supplementary material). This degree of magnetic bead filtration was high enough to allow for visual detection of captured cancer cells on the IMM chip. Based on the designed parameters, the best performance of the MOFF filter was expected to be achieved at a flow rate of 800 μl/min (i.e., 200 μl/min per MOFF module). Nevertheless, preliminary qualitative observations using different dilution factors showed that the most efficient filtration is attained at a surprisingly lower flow rate (200 μl/min per filter or 50 μl/min per MOFF module). This discrepancy can be partly due to the microfabrication error. Moreover, the calculated particle Reynolds numbers for free magnetic beads and target PCa cells were not precisely within the range suggested by other researchers for the best performance of MOFF filters.42 However, the overall particle separation performance using the MOFF device developed in this work was analogous and comparable to those reported in previous works.40–43

CONCLUSIONS

The quality of life and longevity of PCa patients are impaired by delays in detection of metastatic tumours, inaccurate prognoses that lead to unnecessary or inefficient therapies, and failure in early diagnosis of treatment deficiencies. The quantitative and qualitative analysis of CTCs has the potential to address these issues. By fully exploiting the exceptional potential of CTCs in the context of precision oncology, the envisioned future for clinical cancer management would be a model similar to antimicrobial therapies. In such a framework, the results from a blood test would reveal the current molecular signature of the malignancy, the therapeutic targets, and possible modifications in the existing treatments based on the analysis of CTCs. Thanks to recent advances in biotechnology and clinical computational biology, comprehensive catalogs of cancer genes are becoming increasingly malleable, making this concept feasible more than ever. In addition to the potential clinical value of CTCs as early detection, diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and stratification biomarkers,34,47,48 molecular interrogation of CTCs provides researchers with valuable insights into basic mechanisms of carcinogenesis, metastatic progression, and treatment resistance. Identification of novel therapeutic targets may particularly provide treatment options for those cases with rare but highly aggressive driving mutations, such as AR-independent small cell/neuroendocrine PCa.49

To fully exploit such potential applications of CTCs, it is essential to first isolate them from blood. We reported herein the development and preclinical characterization of a novel microfluidic platform. Microfluidic immunomagnetic cell separation is one of the most sensitive and specific techniques for CTC isolation. However, a serious drawback concerning this method is the sheer number of free magnetic particles/beads that remain in the sample after the immunomagnetic labeling process. Our microfluidic platform is made of a MOFF filter and a Permalloy-based IMM chip. The former is utilized for size-based hydrodynamic enrichment of immunomagnetically labeled blood samples, and the latter is employed for isolation of PSMA-immunomagnetically labeled prostatic CTCs from the enriched samples. The proposed immunomagnetic cell isolation approach, including the labeling protocol, the micro-to-macro interfacing, and the microfluidic platform, was able to capture PCa cells at clinically relevant concentrations (5-20 cells/ml) with up to 75% efficiency.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Detailed information about the empirical optimization of immunomagnetic labeling protocols along with the design, microfabrication, and analysis of microfluidic devices presented in this work and the setup used for the experiments can be found in the supplementary material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

H. Esmaeilsabzali would like to acknowledge the support from Prostate Cancer Foundation BC (PCFBC) through a Raymond James Care Postdoctoral Fellowship Award. This work made use of the 4D LABS shared facilities supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund (BCKDF), Western Economic Diversification Canada (WD), and Simon Fraser University (SFU). This work was supported in part by a Discovery Grant (No. RGPIN/298219-2012, E. J. Park) from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and a Terry Fox New Frontiers Program Grant (No. 1062, M. E. Cox) from the Terry Fox Research Institute (TFRI).

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, Global Cancer Facts & Figures, 3rd ed. (American Cancer Society, Atlanta, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegemann M., Stenzl A., Bedke J., Chi K. N., Black P., and Todenhöfer T., BJU Int. 118, 855 (2016). 10.1111/bju.13586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzman D. L. and Antonarakis E. S., Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 6, 167 (2014). 10.1177/1758834014529176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonarakis E. S., Lu C., Wang H., Luber B., Nakazawa M., Roeser J. C., Chen Y., Mohammad T. A., Chen Y., Fedor H. L., Lotan T. L., Zheng Q., De Marzo A. M., Isaacs J. T., Isaacs W. B., Nadal R., Paller C. J., Denmeade S. R., Carducci M. A., Eisenberger M. A., and Luo J., N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1028 (2014). 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonarakis E. S., Lu C., Luber B., Wang H., Chen Y., Nakazawa M., Nadal R., Paller C. J., Denmeade S. R., Carducci M. A., Eisenberger M. A., and Luo J., JAMA Oncol. 1, 582 (2015). 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang C., Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 4, 329 (2012). 10.1177/1758834012449685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alix-Panabières C. and Pantel K., Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 623 (2014). 10.1038/nrc3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tibbe A., Miller M., and Terstappen L., Cytometry A 71, 154 (2007). 10.1002/cyto.a.20369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esmaeilsabzali H., Beischlag T. V., Cox M. E., Parameswaran A., and Park E. J., Biotechnol. Adv. 31, 1063 (2013). 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W., Yin B., Wang X., Yu P., Duan X., Liu C., Wang B., and Tao Z., Oncol. Lett. 14, 1223 (2017). 10.3892/ol.2017.6332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira M., Ramani V., and Jeffrey S., Mol. Oncol. 10, 374 (2016). 10.1016/j.molonc.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D. and Weinberg R. A., Cell 144, 646 (2011). 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khakshour S., Labrecque M. P., Esmaeilsabzali H., Lee F. J., Cox M. E., Park E. J., and Beischlag T. V., Sci. Rep. 7, 7833 (2017). 10.1038/s41598-017-07947-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalluri R. and Weinberg R. A., J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1420 (2009). 10.1172/JCI39104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murlidhar V., Rivera-Báez L., and Nagrath S., Small 12, 4450 (2016). 10.1002/smll.201601394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenck J., Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 87, 185 (2005). 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plouffe B. D., Murthy S. K., and Lewis L. H., Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 016601 (2015). 10.1088/0034-4885/78/1/016601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pamme N., Lab Chip 6, 24 (2006). 10.1039/B513005K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S., Han S. I., Park M. J., Jeon C. W., Joo Y. D., Choi I. H., and Han K. H., Anal. Chem. 85, 2779–2786 (2013). 10.1021/ac303284u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoshino K., Huang Y. Y., Lane N., Huebschman M., Uhr J. W., Frenkel E. P., and Zhang X., Lab Chip 11, 3449 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20270g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karabacak N. M., Spuhler P. S., Fachin F., Lim E. J., Pai V., Ozkumur E., Martel J. M., Kojic N., Smith K., Chen P. I., Yang J., Hwang H., Morgan B., Trautwein J., Barber T. A., Stott S. L., Maheswaran S., Kapur R., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Nat. Protoc. 9, 694 (2014). 10.1038/nprot.2014.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y. Y., Chen P., Wu C. H., Hoshino K., Sokolov K., Lane N., Liu H., Huebschman M., Frenkel E., and Zhang J. X., Sci. Rep. 5, 16047 (2015). 10.1038/srep16047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia J., Chen X., Zhou C., Li Y., and Peng Z., IET Nanobiotechnol. 5, 114 (2011). 10.1049/iet-nbt.2011.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis M. I., Bennet M. J., Thomas L. M., and Bjorkman P. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5981 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0502101102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denmeade S., in Encyclopedia of Cancer, edited by Schwab M. (Springer, 2017), Vol. 4, p. 3068. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labrecque M. P., Takhar M. K., Nason R., Santacruz S., Tam K. J., Massah S., Haegert A., Bell R. H., Altamirano-Dimas M., Collins C. C., Lee F. J., Prefontaine G. G., Cox M. E., and Beischlag T. V., Oncotarget 7, 24284 (2016). 10.18632/oncotarget.8301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang S., Rev. Urol. 6, S13 (2004). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchelouche K., Choyke P., and Capala J., Discov. Med. 9, 55 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross J. S., Sheehan C. E., Fisher H. A., Kaufman R. P., Kaur P., Gray K., Webb I., Gray G. S., Mosher R., and Kallakury B. V., Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 6357 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perner S., Hofer M. D., Kim R., Shah R. B., Li H., Möller P., Hautmann R. E., Gschwend J. E., Kuefer R., and Rubin M. A., Hum. Pathol. 38, 696 (2007). 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh A. and Heston W. D., J. Cell. Biochem. 91, 528 (2004). 10.1002/jcb.10661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Went P. T., Lugli A., Meier S., Bundi M., Mirlacher M., Sauter G., and Dirnhofer S., Hum. Pathol. 35, 122 (2004). 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirby B. J., Jodari M., Loftus M. S., Gakhar G., Pratt E. D., Chanel-Vos C., Gleghorn J. P., Santana S. M., Liu H., Smith J. P., Navarro V. N., Tagawa S. T., Bander N. H., Nanus D. M., and Giannakakou P., PLoS One 7, e35976 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0035976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galletti G., Portella L., Tagawa S. T., Kirby B. J., Giannakakou P., and Nanus D. M., Mol. Diagn. Ther. 18, 389–402 (2014). 10.1007/s40291-014-0101-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieben S., Bergemann C., Lübbe A., Brockmann B., and Rescheleit D., J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 225, 175 (2001). 10.1016/S0304-8853(00)01248-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wognum A. and Lansdorp P., Canada patent, CA2411392A1 (May 7, 2003).

- 37.Esmaeilsabzali H., Beischlag T. V., Cox M. E., Dechev N., Parameswaran A., and Park E. J., Biomed. Microdevices 18, 22 (2016). 10.1007/s10544-016-0041-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X., Mujumdar A., and Yap C., J. Appl. Phys. 102, 073530 (2007). 10.1063/1.2794379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sajeesh P. and Sen A., Microfluid Nanofluidics 17, 1 (2014). 10.1007/s10404-013-1291-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moon H. S., Kwon K., Kim S. I., Han H., Sohn J., Lee S., and Jung H. I., Lab Chip 11, 1118 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00345j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyun K., Kwon K., Han H., Kim S., and Jung H., Biosens. Bioelectron. 40, 206 (2013). 10.1016/j.bios.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park J. and Jung H., Anal. Chem. 81, 8280 (2009). 10.1021/ac9005765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park J., Song S., and Jung H., Lab Chip 9, 939 (2009). 10.1039/B813952K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horoszewicz J. S., Leong S. S., Kawinski E., Karr J. P., Rosenthal H., Chu T. M., Mirand E. A., and Murphy G. P., Cancer Res. 43, 1809 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroock A., Dertinger S., Ajdari A., Mezic I., Stone H., and Whiteside G., Science 295, 647 (2002). 10.1126/science.1066238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams M., Longmuir K., and Yager P., Lab Chip 8, 1121 (2008). 10.1039/b802562b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu B., Rochefort H., and Goldkorn A., Cancers 5, 1676 (2013). 10.3390/cancers5041676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.León-Mateos L., Vieito M., Anido U., López López R., and Muinelo Romay L., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, E1580 (2016). 10.3390/ijms17091580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beltran H., Tomlins S., Aparicio A., Arora V., Rickman D., Ayala G., Huang J., True L., Gleave M. E., Soule H., Logothetis C., and Rubin M. A., Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 2846 (2014). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozkumur E., Shah A. M., Ciciliano J. C., Emmink B. L., Miyamoto D. T., Brachtel E., Yu M., Chen P. I., Morgan B., Trautwein J., Kimura A., Sengupta S., Stott S. L., Karabacak N. M., Barber T. A., Walsh J. R., Smith K., Spuhler P. S., Sullivan J. P., Lee R. J., Ting D. T., Luo X., Shaw A. T., Bardia A., Sequist L. V., Louis D. N., Maheswaran S., Kapur R., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 179ra47 (2013). 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen P., Huang Y., Hoshino K., and Zhang J., Sci. Rep. 5, 8745 (2015). 10.1038/srep08745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun C., Hsieh Y. P., Ma S., Geng S., Cao Z., Li L., and Lu C., Sci. Rep. 7, 0632 (2017). 10.1038/srep40632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y. Y., Chen P., Wu C. H., Hoshino K., Sokolov K., Lane N., Liu H., Huebschman M., Frenkel E., and Zhang J. X., Sci. Rep. 5, 16047 (2015). 10.1038/srep16047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu C. H., Huang Y. Y., Chen P., Hoshino K., Liu H., Frenkel E. P., Zhang J. X., and Sokolov K. V., ACS Nano 7, 8816 (2013). 10.1021/nn403281e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed information about the empirical optimization of immunomagnetic labeling protocols along with the design, microfabrication, and analysis of microfluidic devices presented in this work and the setup used for the experiments can be found in the supplementary material.