Abstract

Non-coding genes occupy the majority of the human genome and have recently garnered increased attention for their implications in a range of diseases. This review illustrates the current scientific landscape concerning long non-coding RNA biogenesis, regulation, and degradation, as well as their functional roles in lung pathogenesis. LncRNAs share many similar biogenesis and regulatory processes with mRNA, such as capping, polyadenylation, post-transcriptional modifications, and exonuclease degradation. Evidence suggests that these lncRNAs become dysregulated in lung diseases such as Acute Lung Injury, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, COPD, Lung Cancer, and Pulmonary Arterial Fiypertension. Some lncRNAs have known functions, but the overwhelming majority requires further research to completely understand.

Keywords: Long non-coding RNA; Acute lung injury, Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; COPD; Pulmonary arterial hypertension; Non-small cell lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Discoveries made by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE] have indicated that protein-coding genes occupy less than 3% of the human genome [1]. These findings suggest that over 97% of the human genomes composed of non-coding RNA (ncRNA]. Non-coding RNAs are divided into several broad categories based on size and include miRNA, piRNA, snoRNA, and lncRNAs [2]. This review will primarily discuss long noncoding RNA (lncRNA], which are defined as transcripts longer than 200 bp in length [2]. Currently, one of the main constraints on studying lncRNAs is the low degree of sequence conservation between mammalian species, presenting challenges for studying lncRNAs in animal models [3]. However, more recent research proposes that promoters and splice sites of lncRNAs display more signs of conservation than previously thought [4,5]. Additionally, while sequence conservation throughout the complete transcript is generally required to retain function in protein-coding genes, lncRNAs can maintain function by only conserving short functional domains [6]. These findings have given credence to the concept that lncRNAs do have endogenous function, which grants the new challenge of uncovering their involvement in disease and pathogenesis.

Computational approaches have been employed to categorize lncRNAs and predict their function in disease. Models such as GENSCAN have been developed to predict exon locations within the genome, while models such as DFA7 can sort between intron-containingor intronless genes [7,8]. These models help define gene sequences, but other models have been developed to understand the underlying mechanisms. Advances in computational genetics have fostered the ability to predict lncRNA-protein, lncRNA-RNA, and lncRNA-DNA interactions [9]. In the case of lncRNA-protein interactions, genome maps of RNA binding proteins (RBPs] have been used to predict their binding locations on various lncRNA transcripts [10]. While predicting these interactions provides valuable information when lncRNA-disease associations are known, the majority of lncRNAs have unknown implications in disease. To discover new associations, other computational models, such as those summarized by Chen and colleagues, can predict novel lncRNA-disease associations and direct future research to that area [11]. The present review will attempt to summarize some of these associations in lung diseases such as Acute Lung Injury, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, COPD, lung cancer, and Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. In addition, it will outline the current knowledge on biogenesis, regulation, and degradation of lncRNAs.

Expressional control

Biogenesis of lncRNAs:

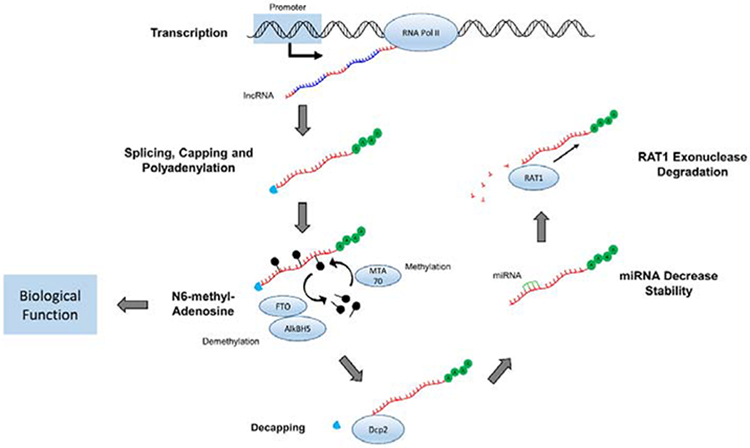

Long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs (mRNA) share related biogenesis pathways, and both of them are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Figure 1) [6,12]. To promote stability and prevent degradation, both a5’ cap and poly-A tail are added to lncRNAs during the transcriptional process [13]. Once synthesized, 98% of lncRNAs will undergo splicing [5]. Interestingly, more than 25% of lncRNAs demonstrate alternative splicing by having at least two transcripts per gene locus [5]. This is possible because lncRNA introns are bordered by AG and GU nucleotides, which guide the spliceosome to cleave at this location [5]. Additionally, lncRNAs contain longer introns and exons than protein-coding genes, but usually contain a smaller number of exons [5]. Given the fewer number of exons, splicing produces a shorter transcript compared to mRNA.

Figure 1.

Representation of sequential biogenesis, regulation, and degradation of lncRNA. LncRNA introns and exons are collectively transcribed with RNA Polymerase II. Alternative splicing then removes introns while 5’ capping and polyadenylation are occurring. Methyl groups are added to Adenosine at the N6 position for further regulation, producing the mature lncRNA transcript ready for biological function. LncRNAs are decapped by Dcp2, destabilized by various miRNAs, and ultimately degraded by RATI exonuclease.

While these processes control the lncRNA form and sequence, Dicer1 is implicated in controlling the relative amount present within the cell [14]. Dicer1, which is an RNase that cleaves pre-miRNA transcripts into mature miRNA, also appears to mediate some regulation of lncRNA expression [15]. Knockouts of DICER1 decrease lncRNA amount in murine embryonic stem cells, suggesting that the WT Dicer1 is partly responsible for the biogenesis of mature lncRNAs [9].

Regulation of lncRNAs:

Through tissue-specific regulation, lncRNAs demonstrate a relatively high level of tissue specificity. While 65% of protein-coding genes are identified in all body tissues, only 11% of lncRNAs are present in all body tissues [16]. This indicates that a much larger subset of lncRNAs are only expressed in certain tissues. Additional data suggests that as many as 78% of lncRNAs are tissue-specific compared to only 19% of coding genes being tissue-specific [16]. This cell ortissue-specific expression pattern of lncRNAs is tightly regulated by promoter sequences [17,18].

Post-transcriptional modifications have been identified to play a role in the regulation of lncRNAs. N6-methyl-Adenosine [m6A], discovered in the 1970s [19], is the most abundant modification of lncRNAs in mammalian cells (Figure 1) [20]. The modification of m6A is a dynamic process controlled by numerous enzymes, including methyltransferase (MTA70] and demethylases (FTO and AlkBH5] [21–23]. The m6Amodification may cause the alteration of lncRNA structure or recruitment of specific m6A binding proteins [20].

Degradation of lncRNAs:

The turnover rate of genetic material dictates the amount available within the cell for protein synthesis and other cellular functions. This process has been well studied in mRNA, which is synthesized in the nucleus and degraded by mechanisms in the cytoplasm. In eukaiyotes, the Dcpl and Dcp2 proteins have both been implicated in removing the 5’ cap from mRNA [24]. Recently, Dcp2 has been shown to also perform 5’ decapping on lncRNA, preparing the transcript for degradation (Figure 1) [25]. After the decapping signal, lncRNAs scan be cleaved by RATI, a prominent mRNA 5’ to 3’ exonuclease located within the nucleus [26].

In addition to decapping and exonuclease cleavage, RBPs and microRNAs (miRNAs) are also involved in the lncRNA degradation process (Figure 1) [27]. RBP can recognize specific nucleotide sequences and either increase or decrease the ability of degradative machinery to operate on lncRNAs. Specifically, RNA binding proteins HuR and A UF1 enhance lncRNA degradation, but PABPN1 and IGF2BP1 promote stability [27]. In a similar fashion, miRNAs have the ability to bind various types of RNA and cause interactions between degradative machineiy. While the ability of miRNAs to degrade mRNAs has been studied extensively, increasing evidence indicates their additional role in lncRNAs degradation [6]. Specifically, research illustrates that miR let-7b, miR-9, miR-34a, miR-211, miR-574–5p, and miR-124 have the ability to decrease lncRNA stability [28–33].

LncRNAs in lung diseases

Acute lung injury:

Acute lung injury (ALI] and its most severe form acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS] have high mortality and morbidity [34]. Recently, the work from Zhang and his colleagues showed that FOXD3-AS1 promoted oxidative stress-induced lung epithelial cell death during hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury (Table 1). Further experiments indicated that FOXD3-AS1 serves as a sponge or as a competing endogenous noncoding RNA for miR-150, leading growth inhibition and lung epithelial cell death [35]. Similarly, a study using lipopolysaccharide (LPS]-induced ALI murine model has shown lncRNA CASC2functions as a miR-144–3p decoy and plays a critical role in LPS-induced lung epithelial cell apoptosis [36]. Long non-coding RNA NANCI has been reported to be involved in the development of hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal mice [37]. These findings indicate the dysregulation of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS and potentially will help to identify novel mechanisms and/or therapeutic strategies in the future.

Table 1:

Long non-coding RNAs implicated in lung diseases.

| Lung Disease | lncRNA | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALI | FOXD3-AS1 | FOXD3-AS1 serves as sponge for miR-150, inhibiting lung epithelial cell growth | [28] |

| CASC2 | Serves as miR-144–3p decoy and plays a role in LPS-induced lung epithelial cell apoptosis | [29] | |

| NANCI | Involved in the development of hyperoxia-induced lung injury | [30] | |

| IPF | H19 | Upregulated in fibroblasts, promoting proliferation and collagen deposition | [34,35] |

| COPD | SCAL1 | Upregulated in response to cigarette smoke to serve as protective mechanism | [41] |

| Lung Cancer | MALATl | Upregulated in NSCLC and predictor of prognosis | [42] |

| UCA1 | Upregulated in NSCLC and predictor of prognosis | [43] | |

| HOTAIR | Upregulated in NSCLC and promotes metastatic breast cancer progression | [44–46] | |

| PAH | TCONS_00034812 | Downregulated in PAH patients, promoting proliferation of PASMCs and pulmonary artery thickening | [50,51] |

Abbreviations: ALI: Acute Lung Injury; IPF: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; PAH: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension; lncRNA: Long Non-Coding Rna; NSCLC: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer; PASMCs: Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis:

Experimental findings have revealed that lncRNAs are involved in lung diseases such as Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF]. IPF is categorized by excessive inflammation and fibrosis [38]. Rat models of fibrosis showed 568 differentially expressed lncRNAs between the model and normal groups [39]. Similar findings have been illustrated in human IPF patients with 9 lncRNAs showing differential expression [40]. Of these differentially regulated genes, the lncRNAH19 is highly upregulated in fibroblasts both in vitro and in vivo in bleomycin-induced fibrosis [41]. Upon inhibiting H19 expression in NIH3T3 cells, a mouse fibroblast cell line, cell proliferation decreased (Table 1) [42]. These findings suggest that H19 assists fibroblast proliferation, allowing for more collagen deposition in lung tissue and progression of IPF.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD):

LncRNAs have also been shown to induce pathogenesis in COPD, which is a common airway disease, causingrestricted airflow and inflammation [43]. Oxidative stress generated by cigarette smoke is a known risk factor for COPD, and cigarette smoke is the cause of death in 90% of COPD cases [44,45]. Certain lncRNA transcripts are upregulated while others are downregulated in response to cigarette smoke [46,47]. Smoke and cancer associated lncRNA-l (SCAL1) becomes upregulated upon exposure to cigarette smoke extract in Human Bronchial Epithelium (HBE1) cells [48]. Furthermore, knockdown of SCAL1 decreases cell viability, suggesting that it might serve as a protective mechanism against cigarette smoke-induced toxicity (Table 1) [48]. As the name suggests, SCAL1 is also implicated in lung cancer. Specifically, the lncRNA becomes upregulated in lung cancer, suggesting a connection between cigarette smoke, COPD, and lung cancer development.

Lung Cancer:

Certain other lncRNAs induce the formation of lung cancer and accelerate its progression. MALAT1 and UCA1 are both upregulated lncRNA in metastasizing non-small cell lung cancer (Table 1) [49,50]. Higher levels of MALAT1 were predictive of poor prognosis compared to lower expression [49], and elevated UCA1 levels were correlated with histological grade of the NSCLC and poorer prognosis [50]. HOTAIR is another lncRNA oncogene that is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer [51,52]. Interestingly, HOTAIR is predictive of breast cancer prognosis, attracting attention for its use as a potential biomarker and indicator of non-small cell lung cancer progression (Table 1) [53,54]. More research must be conducted to determine the roles of these lncRNAs in small cell lung cancers as well as different types of NSCLC such as squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas. Looking forward, these lncRNAs and others could prove promising for cancer staging and determine prognosis in various lung cancer types.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension:

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH] is a disease defined by mean pulmonary arterial blood pressure ≥ 25 mmHg when measured at rest [55,56]. Arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation induces thickening of pulmonary arteries (PA], contributing to the increased pressure [57]. Hypoxia-induced PAH rat models showed pulmonary artery thickening and demonstrated upregulation of 36 lncRNAs and downregulation of 111 lncRNAs when compared to non-hypoxia groups [57]. This research examined one downregulated lncRNA, TCONS_00034812, and discovered that inhibiting this transcript with siRNAs increased proliferation of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells [PASMC]. This suggests a role of TCONS_00034812 dysregulation in PA thickening (Table 1). Similar results have been shown in humans where the lncRNAMEG3 is downregulated in tissue samples from PAH patients [58]. Additionally, knockdown of MEG3 increased proliferation of PASMC [58]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate an involvement of lncRNAs in PASMC proliferation, leading to medial thickening of PAs and increased arterial pressure.

CONCLUSION

Increasing evidence demonstrates that lncRNA have larger roles within the cell than previously believed. Much can be learned about the biogenesis, regulation, and degradation of lncRNA by studying it in comparison to other more well-known processes in mRNA or miRNA. Many endogenous processes are shared because the composition of lncRNA is similar to mRNA and miRNA. With knowledge of these regulatory processes coming to light, increasing amounts of research has been published demonstrating the role of lncRNAs in lung disease and pathogenesis. While many differentially expressed lncRNAs have been identified in a range of diseases including ALI, IPF, COPD, lung cancer, and PAH, the next challenge remains to determine their specific function in pathogenesis. Computational approaches can be employed to predict these functions and guide research towards specific areas. Once functions have been identified, the future looks towards manipulating lncRNA expression for therapeutic purposes and expanding upon the potential of using lncRNAs as biomarkers in lung disease progression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01GM127596 to Y.J. R21AI121644 and R33AI121644 to Y.J. R01GM111313 to Y.J. and K99HL141685 to D.Z.]. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LncRNA

Long Non-Coding RNA

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- m6A

N6-methyl-Adenosine

- RBP

RNA Binding Proteins

- ARDS

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- ALI

Acute Lung Injury

- IPF

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- NSCLC

Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

- PAH

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

- PASMC

Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells

- PA

Pulmonary Arteries

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.J. developed the topic and outline. M.G., D.Z., and Y.J. analyzed literature and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Uchida S, Dimmeler S. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2015; 116: 737–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteller M Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011; 12: 861–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Zhang J, Zheng H, Li J, Liu D, Li H, et al. Mouse transcriptome: neutral evolution of ‘non-coding’ complementary DNAs. Nature. 2004; 431:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponjavic J, Ponting C, Lunter G. Functionality or transcriptional nose? Evidence for selection within long noncoding RNAs. Genome Research. 2007; 17: 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012; 22:1775–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009; 10:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997; 268: 78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu C, Deng M, Zheng L, He RL, Yang J, Yau SS. DFA, a new method to distinguish between intron-containing and intronless genes. PLoS One. 2014; 9:101363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalali S, Kapoor S, Sivadas A, Bhartiya D, Scaria V. Computational approaches towards understanding human long non-coding RNA biology. Bioinformatics. 2015; 31: 2241–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalali S, Gandhi S, Scaria V. Distinct and Modular Organization of Protein Interacting Sites in Long Non-coding RNAs. Front Mol Biosci. 2018; 5: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Yan CC, Zhang X, You Z. Long non-coding RNAs and complex diseases: from experiemntal results to computational models. Brief Bioinform. 2017; 18: 558–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Functional interactions among micro RNAs and long noncoding RNAs. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014; 34: 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn JJ, Chang HY. Unique features of long non-coding RNAbiogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2016; 17: 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fang Y, Fullwood MJ Roles Functions, and Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2016; 14:42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng GX, Do BT, Webster DE, Khavari PA, Chang HY. Dicer-microRNA-Myc circuit promotes transcription of hundreds of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014; 21: 585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabili M, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011; 25:1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casero D, Sandoval S, Seet CS, Scholes J, Zhu Y, Ha VL, et al. Long noncoding RNA profiling of human lymphoid progenitor cells reveals transcriptional divergence of B cell and T cell lineages. Nat Immunol. 2015; 16:1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchese FP, Raimondi I, Huarte M. The multidimensional mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function. Genome Biol. 2017; 18: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974; 71: 3971–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan T N6-methyl-adenosine modification in messenger and long noncoding RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013; 38: 204–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bokar JA, Rath-Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269: 17697–17704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi C, Pan T. Cellular dynamics of RNA modification. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1380–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013; 49:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunckley T, Parker R. The DCP2 protein is required for mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and contains a functional MutT motif. EMBO J. 1999; 18: 5411–5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisler S, Lojek L, Khalil AM, Baker KE, Coller J. Decapping of long noncoding RNAs regulates inducible genes. Mol Cell. 2012; 45: 279–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson AW. Rat1p and Xrn1p are functionally interchangeable exoribonucleases that are restricted to and required in the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively. Mol Cell Biol. 1997; 17: 6122–6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon JH, Kim J, Gorospe M. Long noncoding RNA turnover. Biochimie. 2015; 117:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Yang X, Martindale JL, De S, et al. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell. 2012; 47: 648–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leucci E, Patella F, Waage J, Holmstrom K, Lindow M, Porse B, et al. MicroRNA-9 targets the long non-coding RNA MALAT1 for degradation in the nucleus. Sci Rep. 2013; 3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao C, Sun J, Zhang D, Guo X, Xie L, Li X, et al. The long intergenic noncoding RNA UFC, a target of microRNA 34a, interacts with the mRNA stabilizing protein HuR to increase levels of β-catenin in HCC cells. Gastroenterology. 2015; 148: 415–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q, Huang J, Zhou N, Zhang Z, Zhang A, Lu Z, et al. LncRNAloc285194 is a p53-regulated tumor suppressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41: 4976–4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan M, Li X, Jiang W, Huang Y, Li J, Wang Z. A long non-coding RNA, PTCSC3, as a tumor suppressor and a target of miRNAs in thyroid cancer cells. Exp Ther Med. 2013; 5:1143–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan JY, Vance KW, Varela M a, Sirey T, Lauren M, Curtis HJ, et al. Crosstalking noncoding RNAs contribute to cell-specific neurodegeneration in SCA7. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015; 21: 955–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randolph AG. Management of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome in children. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37: 2448–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D, Lee H, Haspel JA, Jin Y. Long noncoding RNA FOXD3-AS1 regulates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via sponging microRNA-150. FASEB J. 2017; 31: 4472–4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Shi H, Gao M, Ma N, Sun R. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 improved acute lung injury by regulating miR-144–3p/AQP1 axis to reduce lung epithelial cell apoptosis. Cell Biosci. 2018; 8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Cheng HP, Bao TP, Wang XG, Tian ZF. [Expression of long noncoding RNA NANCI in lung tissues of neonatal mice with hyperoxia-induced lung injury and its regulatory effect on NKX2.1]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2017; 19: 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzenstein ALA, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998; 157:1301–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao G, Zhang J, Wang M, Song X, Liu W, Mao C, et al. Differential expression of long non-coding RNAs in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2013; 32: 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang C, Yang Y, Liu L. Interaction of long noncoding RNAs and microRNAs in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Physiol Genomics. 2015; 47: 463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu Q, Guo Z, Xie W, Jin W, Zhu D, Chen S, et al. The lncRNA H19 Mediates Pulmonary Fibrosis by Regulating the miR-196a/COL1A1 Axis. Inflammation. 2018; 41: 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang Y, He R, An J, Deng P, Huang L, Yang W. The effect of H19-miR-29b interaction on bleomycin-induced mouse model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016; 479: 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rennard SI. COPD: overview of definitions, epidemiology, and factors influencing its development. Chest. 1998; 113: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannino DM. COPD: Epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest. 2002; 121:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tashkin DP, Murray RP. Smoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009; 103: 963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Sun D, Li D, Zheng Z, Xu J, Liang X, et al. Long non-coding RNA expression patterns in lung tissues of chronic cigarette smoke induced COPD mouse model. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bi H, Zhou J, Wu D, Gao W, Li L, Yu L, et al. Microarray analysis of long non-coding RNAs in COPD lung tissue. Inflamm Res. 2015; 64: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thai P, Statt S, Chen CH, Liang E, Campbell C, Wu R. Characterization of a novel long noncoding RNA, SCAL, induced by cigarette smoke and elevated in lung cancer cell lines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013; 49: 204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Böing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM, et al. MALAT-, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin β4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003; 22: 8031–8041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang HM, Lu JH, Chen WY, Gu AQ. Upregulated lncRNA-UCA1 contributes to progression of lung cancer and is closely related to clinical diagnosis as a predictive biomarker in plasma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015; 8: 11824–11830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa T, Endo H, Yokoyama M, Abe J, Tamai K, Tanaka N, et al. Large noncoding RNA HOTAIR enhances aggressive biological behavior and is associated with short disease-free survival in human non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 436: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu XH, Liu ZL, Sun M, Liu J, Wang ZX, De W. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR indicates a poor prognosis and promotes metastasis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013; 13: 464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010; 464:1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vencken SF, Greene CM, McKiernan PJ. Non-coding RNA as lung disease biomarkers. Thorax. 2015; 70: 501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vinke P, Jansen SM, Witkamp RF, Van Norren K. Increasing quality of life in pulmonary arterial hypertension: is there a role for nutrition? Heart Fail Rev. 2018; 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramakrishnan Latha, Pedersen Sofia L., Toe Quezia K., Quinlan Gregory J., et al. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Iron Matters. Front Physiol. 2018; 9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Sun Z, Zhu J, Xiao B, Dong J, Li X. LncRNA-TCONS_00034812 in cell proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and its mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2018; 233: 4801–4814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, Sun Z, Nie X, Sun S, Dong S, Yuan C, et al. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Downregulation Triggers Human Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration via the p53 Signaling Pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017; 42: 2569–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]