Abstract

Multisystem-involved youth are children and adolescents concurrently served in the child welfare, behavioral health, and/or juvenile justice systems. These youth are a high risk and vulnerable population, often due to their experience of multiple adversities and trauma, yet little is known about their multiple needs and pathways into multisystem involvement. Multisystem-involved youth present unique challenges to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. In this article, we summarize the literature on multisystem-involved youth, including prevalence, characteristics, risk factors, and disparities for this population. We then describe a developmental cascade framework, which specifies how exposure to adverse experiences in childhood may have a “cascading” or spillover effect later in development, to depict pathways of multisystem involvement and opportunities for intervention. This framework offers a multidimensional view of involvement across service systems and illustrates the complexities of relationships between micro- and macro-level factors at various stages and domains of development. We conclude that multisystem-involved youth are an understudied population that may represent majority of youth who are already served in another service system. Many of these youth are also disproportionately from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. Currently, for multisystem-involved youth and their families, there is a lack of standardized and integrated screening procedures to identify youth with open cases across service systems; inadequate use of available instruments to assess exposure to complex trauma; inadequate clinical and family-related evidence-based practices specifically for use with this population; and poor cross-systems collaboration and coordination that align goals and targeted outcomes across systems. We make recommendations for research, practice, and systems development to address the needs of multisystem-involved youth and their families.

Keywords: multisystem involvement, child welfare, behavioral health, juvenile justice, delinquency, maltreatment

Introduction

Multisystem involved youth are children or adolescents who are concurrently served in more than one service system; specifically, the child welfare system, the juvenile justice system, or the behavioral health system. In the United States, as many as two-thirds of children under age 18 that are already in one of these systems may be multisystem-involved youth (Herz et al., 2012; Halemba & Siegel, 2011); thus, making multisystem involvement the defacto norm for service delivery. Many of these youth have complex needs that place them at risk for poor long-term health and developmental outcomes, including mental health and substance abuse problems, and delinquency (Garland, Hough, Landsverk, & Brown, 2001; Miller, Green, Fettes, & Aarons, 2011). However, this fact is rarely addressed in how services are conceptualized, structured, delivered, and studied. In theory, concurrent services from multiple systems can address these children’s complex needs. In practice, multisystem involvement often results in insufficient or inappropriate services across systems (Herz et al., 2012; Chuang & Wells, 2010); diminished, duplicative, or contradictory services (Siegel & Lord, 2005); and disparities in service access, delivery, or outcomes (Chuang & Wells, 2010; Huang, Ryan, & Herz, 2012; Ross, 2009; Ryan, Williams, & Courtney, 2013). The complex needs of multisystem-involved youth present unique challenges to practitioners as well as policymakers responsible for developing systems of care that can address those needs (Ko et al., 2008; Ungar, 2015).

In this article, we examine the literature on multisystem-involved youth and offer an integrative theory that draws on a developmental cascade framework to guide future research and practice. We summarize the prevalence of multisystem involvement among youth as well as the needs and challenges of this vulnerable population, including disparities in service access and outcomes. We also ground this work in developmental theory and illustrate multisystem pathways across development. Final sections discuss systems challenges for addressing the needs of multisystem-involved youth and implications for research, policy, and practice.

Prevalence and Characteristics of Multisystem Involvement

Before summarizing the prevalence and characteristics of multisystem-involved youth, we introduce several terms commonly used to describe youth involved in multiple service systems. Researchers have used broader definitions of multisystem involvement to emphasize characteristics of youth, including risks and needs, versus system involvement. For instance, the terms “youth with complex needs,” and “multi-problem youth” have been used to describe youth with presenting problems that are typically addressed by multiple service systems (Mitchell, 2011; Odgers, Vincent, & Corrado, 2002; Ungar, 2014). Crossover youth is also a commonly used term to describe a population of youth who experienced maltreatment and engaged in delinquency (Herz et al., 2012). Notably, system-involvement is not a defining characteristic of crossover youth as they may or may not be known to either the child welfare or juvenile justice system. The mechanisms by which crossover involvement may lead to multisystem involvement remain an empirical question, but crossover estimates suggest that there may be common pathways of multisystem involvement. As described below, our definition emphasizes system involvement in addition to youth characteristics.

An emerging term used by researchers and practitioners is dual status youth and describes children and adolescents concurrently involved in both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system (Herz et al., 2012; Siegel, 2014). Some researchers have further clarified dual status involvement by differentiating between dually-involved youth and dually-adjudicated youth (Herz et al., 2012). Dually-involved youth are youth with any kind (e.g., diversionary, formal, or a combination of both) of concurrent involvement with both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system. Dually-adjudicated youth, on the other hand, describe youth who have concurrent formal involvement with both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system through an open child welfare case and an adjudicated juvenile justice case. A number of recent studies have tracked this population of youth in order to identify their risks and needs and to provide more appropriate services (Graves, Frabutt, Shelton, 2007; Ryan et al., 2013; Herz, Ryan, & Bilchik, 2010; Huang et al., 2012).

This article focuses on both dually-involved and dually-adjudicated youth, as well as youth concurrently involved in the behavioral health system, that is, youth who receive services from a public behavioral health agency independent of the child welfare and juvenile justice agencies. We collectively refer to them as multisystem-involved youth. An active involvement in more than one service system presents unique and significant challenges to multisystem-involved youth.

Prevalence

The lack of an accepted and systematic approach for identifying multisystem-involved youth makes it difficult to determine the true prevalence of multisystem involvement. As a result, prevalence estimates of multisystem-involved youth vary widely from one study to another and across systems. Most studies rely on administrative data from multiple service systems in different jurisdictions and focus on various cohorts of youth with different starting or end points of system involvement (Graves, Frabutt, & Shelton, 2007; Herz et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2013). Different target populations and varying methods have yielded a wide range of prevalence estimates.

For example, studies of youth receiving public behavioral health services indicate that 12–47 percent of youth are also involved in the juvenile justice system (Cauffman, Scholle, Mulvey, & Keheller, 2005; Dale, Baker, Anastasio, & Purcell, 2007; Graves et al., 2007). Indeed, estimates suggest that up to 75 percent of youth in the juvenile justice system have mental health and/or substance use problems (Cauffman, Lexcen, Goldweber, Shulman, & Grisso, 2007; Cauffman et al., 2005; Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002).

Other studies of youth in the juvenile justice system and the child welfare system offer a wider range of prevalence estimates. In one study, Huang et al. (2012) utilized official records from the Department of Children and Family Services and the Department of Juvenile Probation in Los Angeles County, California. They selected a cohort of youth (n = 61,884) involved in child welfare services; child welfare records were then linked with delinquency records from juvenile probation. They identified 1,148 (2%) of youth who had active cases in both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system. In the state of Washington, Ryan et al. (2013) utilized a sample of 19,833 offending youth who completed a risk assessment instrument for juvenile courts between 2004 and 2007. They then linked the youth’s juvenile justice record with records from child protective services. Ten percent of the youth were identified as dual status youth—these youth had an open child welfare case at the time of their arrest.

A higher prevalence rate of multisystem-involved youth was reported by Halemba and Siegel (2011) for King County in the state of Washington. Of the youth referred to the juvenile justice system in 2006, two-thirds were identified as youth with active referrals in both the juvenile justice system and the child welfare system. In Arizona, Halemba et al. (2004) utilized the juvenile courts’ automated systems in four local counties to identify youth with active delinquency and dependency cases. They found that only 1 percent of youth with informal court involvement were also concurrently involved with the child welfare system; whereas, 7–42 percent of youth with formal court involvement were simultaneously involved in the juvenile justice system and the child welfare system. Among youth with formal court involvement, 7 percent were on probation, 42 percent were on probation placement (youth placed on probation and residing in group home or residential placement), 11 percent were placed in a detention center, and 12 percent were committed to a juvenile correctional facility. These diverging estimates suggest that the deeper youth are involved in the juvenile justice system, the proportion of multisystem involvement may be greater. Variation may also be attributed to differences in methods to track multisystem-involved youth across systems, or in practice, the systems lack of appropriate screening procedures to identify multisystem-involved youth.

Characteristics

Disproportionate minority contact

Most studies indicate that minority youth are more likely to be concurrently involved in multiple service systems than White youth (see Halemba & Siegel, 2011; Halemba et al., 2004; Ryan et al., 2013). These findings are consistent with research on disproportionate minority contact across different service systems. For example, Black youth are more likely to enter the foster care system than White or Hispanic youth even after accounting for a range of youth and case characteristics (Herz et al., 2012; Hill, 2007; Putnam-Hornstein, Needell, King, & Johnson-Motoyama, 2013). Black youth are also more likely to be recommended for formal processing, prosecuted for felony crimes, and found delinquent, compared to White youth, even when prior records are considered (Bishop, Leiber, & Johnson, 2010).

Research also suggests that previous system involvement is linked to differential treatment of minority youth in case processing and access to services. For example, racial and ethnic minority youth with a history of child welfare system or behavioral health system involvement are disproportionately referred to the juvenile justice system, including high rates of entry into secure correctional facilities (Vidal, Prince, Connell, Caron, Kaufman, & Tebes, 2017; Goodkind, Shook, Kim, Pohlig, & Herring, 2013; Ryan et al, 2013; Graves et al., 2007; Johnson-Reid & Barth, 2000; Vander Stoep, Evens, & Taub, 1997). These findings remain even after accounting for critical risk factors, such as history of arrest, home environment, peer association, school attendance, and receipt of mental health and substance abuse services (Goodkind et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2013). Once minority youth enter the child welfare system, they are less likely to receive mental health services than White youth (Garland, Landsverk, & Lau, 2003). Although disproportionate minority contact has been examined individually for different service systems (Davis & Sorensen, 2013; Drake, Jolley, Lanier, Fluke, Barth, & Jonson-Reid, 2011), little is known about the disproportionate involvement of racial and ethnic minority youth in multiple service systems and the mechanisms by which disparities in access to services and outcomes operate.

Gender

For girls, there is emerging evidence that multisystem involved youth are disproportionately represented among those involved in the juvenile justice system (Herz et al., 2012). Compared to boys, system-involved girls may have needs that are more complex. For example, offending girls report higher rates and different types of mental health problems than offending boys or their community counterparts (Cauffman et al., 2007). Importantly, system-involved girls experience high rates of victimization and also report high rates of mental health problems (Maschi, Schwalbe, Morgen, Gibson, & Violette, 2009; Odgers, Robins, & Russell, 2010). Girls that receive multisystem services also often experience more conflict and hostility in their interpersonal relationships, including physical and emotional abuse (Dixon, Howie, & Starling, 2004; Downey, Irwin, Ramsay, & Ayduk, 2004; Maschi et al., 2009). Because boys are disproportionately involved in most service systems with the exception of the child welfare system (Garland et al., 2001), girls in many service systems may be less likely to have their needs met (Dixon et al., 2004; Odgers et al., 2010). For example, the lack of gender-based intervention for victimized offending girls might result in lengthier stays in detention centers even when their offenses do not warrant such disposition. It is also not unusual for girls to be sent to programs designed for boys (Miller, Miller, & Broadus, 2014; Sadiq & Khan, 2014).

Academic and behavioral challenges

Multisystem-involved youth are also more likely to experience academic and behavioral health challenges than single system-involved youth. Studies have reported high rates of truancy, expulsion, and behavioral problems at school for multisystem-involved youth (Huang et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2013; Hirsch, Dierkhising, & Herz, 2018). For example, more than three-quarters (76%) of multisystem-involved youth indicated behavioral problems in school compared to 65 percent of juvenile justice system-only youth (Ryan et al., 2013). Multisystem-involved youth were also more likely to experience school dropout compared to single system-involved youth (Garcia et al., 2017). In addition, approximately one-third of multisystem-involved youth had a mental health diagnosis compared to 20 percent of juvenile justice system-only youth (Ryan et al., 2013).

Family background

Another characteristic of multisystem-involved youth is that they are more likely to come from disadvantaged family backgrounds that have less stable family relationships and lower social support compared to single system-involved youth (Herz et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2013). For instance, two-thirds of multisystem-involved youth have been reported to reside in out-of-home placement at the time of their arrest and contact with the juvenile justice system (Huang et al., 2012), two-thirds (versus 41–44 percent of single-system involved) have a history of running away (Dale et al., 2007), and up to one-third have parents with drug and alcohol problems (versus 21 percent for juvenile justice system-only youth; Ryan et al., 2013). The lack of supportive and stable relationships may exacerbate the already vulnerable situations of multisystem-involved youth. Decision-makers such as family or juvenile court judges may consider a supportive adult figure as a positive indicator of stability and well-being among youth; and thus, for youth with at least one supportive adult, they are likely to consider sanctions other than detention or out of home placement (Munson & Freundlich, 2005).

In sum, research indicates that multisystem-involved youth present more complex and intersecting needs and risks than single system-involved youth or their community counterparts. However, our understanding of the prevalence of these needs and risks is limited because of widely varying procedures to define and monitor multisystem involvement. Since multisystem-involved involvement can occur throughout childhood and adolescence, and may include different pathways to system entry, it is critical that it is understood within a developmental context. In the next section, we describe a developmental framework to illustrate how multiple risks may influence child and adolescent pathways into multisystem involvement and identify critical periods for intervention.

A Developmental Cascade Framework of Pathways to Multisystem Involvement

Empirical studies on system-involved youth have identified several key factors linked to poor developmental and health outcomes. For example, inadequate parenting, history of maltreatment and trauma, socio-emotional difficulties, poor adjustment in school, and antisocial behaviors have been associated with mental health and/or substance abuse problems and delinquency (Leve, Harold, Chamberlain, Landsverk, Fisher, & Vostanis, 2012; Miller et al., 2011; Ford, Elhai, Connor, & Freuh, 2010; Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, van der Laan, Smeenk, & Gerris, 2009; Cicchetti, 2004). However, multisystem involvement does not occur in a vacuum; the relationship between risk factors and service system involvement suggests a transactional and complex process.

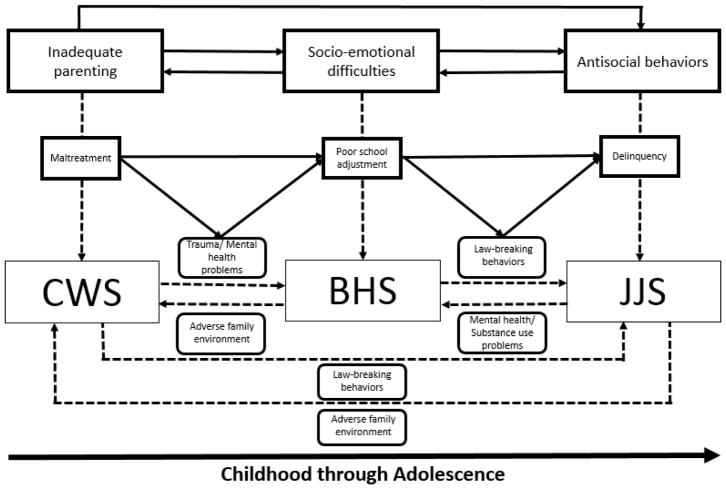

As illustrated in Figure 1, we propose a dynamic, cascading, and transactional developmental framework to describe pathways to multisystem involvement for children and adolescents. A developmental cascade framework specifies how exposure to adverse experiences in childhood may have a “cascading” or spillover effect later in development (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010; Dodge et al., 2009; Dodge, Greenberg, & Malone, 2008). Specifically, risk factors that occur at various stages and domains of development lead to trajectories of escalating problem behaviors and poor health outcomes resulting in multisystem involvement. These risk factors may describe individual and interrelated environmental systems, including the family and community, throughout development. Thus, a developmental cascade framework offers a multidimensional view of involvement across service systems and illustrates the complexities of relationships between micro- and macro-level factors at various stages and domains of development. Importantly, these developmental transactions also provide opportunities for disruption of cascading effects through timely implementation of evidence-based practices.

Figure 1.

Developmental cascade framework of multisystem involvement pathways from childhood through adolescence. The solid arrows indicate the continuity and cascade paths of risks from childhood through adolescence. The broken arrows indicate multisystem involvement pathways across different service systems. The thick-lined boxes indicate examples of sequela of events and risk factors that may lead to system involvement. The rounded boxes indicate target areas and opportunities for intervention.

CWS = Child Welfare System; BHS = Behavioral Health System; JJS = Juvenile Justice System

Although there are clearly many possible developmental cascades leading to multisystem involvement, here we highlight common pathways for illustrative purposes. In one example that illustrates a developmental cascade from early childhood through adolescence, an adverse family environment, characterized by inadequate parenting or maltreatment in early childhood may result in involvement in the child welfare system. Subsequent socio-emotional difficulties of the child, such as poor adjustment in school, may lead to the child’s involvement in the behavioral health system. Further, antisocial behaviors, such as skipping school or association with deviant peers, may lead to law-breaking behaviors that result in involvement of the juvenile justice system. The developmental cascade framework illustrates the direct and unidirectional, direct and bidirectional, and the indirect effects of the transactions among these risk factors through various pathways. The framework supports exploration of pathways to multisystem involvement within and across developmental periods and facilitates identification of critical periods for intervention.

Multisystem Involvement in Early and Middle Childhood

In early to middle childhood, the most common pathway to multisystem involvement is from the child welfare system to behavioral health system. Initial entry via the child welfare system is consistent with the developmental context of exposure to risk factors in early childhood. For example, a child may become involved in the child welfare system because of inadequate parenting, which may involve the inability of parents to care for their child due to parental abuse of illegal substances, serious mental health problems, and/or abuse and neglect of the child (McCoy & Keen, 2009; Vanderploeg, Connell, Caron, Saunders, Katz, & Tebes, 2007; Ryan & Testa. 2005). Research suggests that child maltreatment peaks at an early age around the transition from preschool to primary school and the transition from primary to secondary school (Stewart, Livingston, & Dennison, 2008).

A developmental cascade framework illustrates how the nature, timing, and duration of risk exposure can influence pathways to multisystem involvement. For example, a child with substantiated neglect due to parental substance use will likely experience a different set of cascading risks than a child with substantiated physical abuse within the context of persistent domestic violence. Further, the timing of risk exposure may also differentially effect pathways to system involvement and related outcome trajectories, with early risk exposure usually resulting in more detrimental consequences (Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2001; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001). However, the effect of timing of exposure to risk factors on trajectories of pathways to multisystem involvement and associated outcomes remains an empirical question.

A developmental cascade framework also illustrates how a risk factor may alter the course of development in multiple domains of functioning. For example, neglectful, harsh, and punitive parenting in childhood may result in child welfare system involvement, but these adversities have also been linked to child socio-emotional difficulties (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003; Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003). Such parenting practices may also undermine a child’s capacities for emotional regulation and adaptive functioning (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Chang et al., 2003). When these diminished capacities occur in school they may manifest as poor academic engagement, behavioral disruption in the classroom, and difficulty in peer relationships. This likely results in referral to the behavioral health system to address the child’s socio-emotional problems. In fact, the educational system is among the most common points of entry into the behavioral health system (Farmer, Burns, Phillips, Angold, & Costello, 2003).

A less prevalent multisystem pathway occurs when parents seek help from the child welfare system or the juvenile justice system to obtain mental health services for their child. In such cases, severe child socio-emotional difficulties may render parents unable to care for their child, such that in some cases, they relinquish custody to the child welfare system or the juvenile justice system so that their child receives essential mental health care (Grisso, 2008; Garland et al., 2001). In a survey conducted by the United States General Accounting Office (2003), child welfare and juvenile justice systems reported that over 12,700 children and youth were placed under their care for the primary purpose of receiving mental health care. Although there are several factors that influence parents to seek mental health care through other service systems, among the common reasons include: limited mental health resources in the community, stringent requirements for access to mental health services, and lack of understanding about rules and procedures for obtaining mental health care (Cummings, Wen, & Druss, 2013; U.S. GAO, 2003).

Resorting to the child welfare system or the juvenile justice system to obtain mental health care may mean that these multisystem-involved youth may not receive the services they most need because these systems are not primarily designed to deliver mental health services. This is especially true in the juvenile justice system because juvenile justice facilities often do not have the tools or treatments necessary to address the mental health needs of youth they serve (Sedlak & McPherson, 2010), needs that may have their roots in early childhood traumatic experiences (Ford & Courtois, 2009).

Multisystem Involvement in Adolescence

A developmental cascade framework also suggests that there is a continuity in risk exposure across developmental periods. Several examples illustrate this process. Inadequate parenting in childhood may persist into adolescence as low parental supervision and monitoring (Dodge et al., 2009). Socio-emotional difficulties in childhood may persist into adolescence as significant mental health problems (Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006). Poor adjustment in school during childhood may persist into adolescence and escalate as serious problem behaviors, including involvement in delinquency (Egeland, Yates, Appleyard, & van Dulmen, 2002).

Also, cascade paths reflect the multilevel effects of risk factor accumulation across development. Socio-emotional difficulties in childhood may not only persist as mental health problems in adolescence, but are also likely to affect school adjustment (Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffitt, & Silva, 1995). Although risk factors in adolescence may result in similar multisystem involvement outcomes observed in childhood, we expect that youth are more likely to be involved in the juvenile justice system prior to or in addition to the child welfare system or the behavioral health system as a result of the interaction between the accumulated risk exposures across development and the critical developmental changes that occur in adolescence.

There is also evidence that service system involvement in childhood is a significant predictor of future multisystem involvement. For example, in a study involving a community sample of youth, Kelley, Thornberry, and Smith (1997) reported that between 42 percent to 79 percent of youth with maltreatment history subsequently engaged in delinquency. Research also shows that maltreated youth have higher rates of arrests for general, violent, and substance abuse offenses than their non-maltreated counterparts (Smith, Ireland, & Thornberry, 2005). Developmental cascade models of maltreatment and antisocial behaviors suggest that the incremental effects of risk exposure within and across development contribute substantially to negative outcomes (Cicchetti, 2013; Rogosch et al., 2010; Dodge et al., 2008; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2002). Further, involvement in a service system may expose a child to new risk factors and exacerbate the progression of risk within and across development due to the child’s removal from home or experiences of multiple residential transitions (Baglivio et al.; 2016; Lamb, 2015; Leve et al., 2012; Connell, Vanderploeg, Flaspohler, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, 2006;). Such risk factors have been linked to poor outcomes, including re-maltreatment and delinquency (Connell et al., 2006; Graves et al., 2007; Ryan & Testa, 2005).

Whereas problem behaviors in childhood may result in involvement in the child welfare system or the behavioral health system, problem behaviors in adolescence may initially result in involvement in the juvenile justice system. In the latter case, persistent problem behaviors from childhood into adolescence may be perceived as threats to the safety of the youth and public, particularly when they involve law-breaking behaviors (Scott & Steinberg, 2008). Poor school adjustment in adolescence, for example, may manifest as excessive school absences, which in some jurisdictions have legal consequences under the compulsory school attendance laws (Clay, Lingwall, Stephens, 2012). Truancy is also linked to other problem behaviors, some of which are considered status offenses (e.g., running away from home, possession of alcohol) and are punishable by law (Vaughn, Maynard, Salas-Wright, Perron, & Abdon, 2013; Henry, 2007). These problem behaviors are more pronounced among adolescents with low parental supervision and monitoring (DiClemente et al., 2001) and those who associate with deviant peers (Patterson, Dishion, & Yoerger, 2000). The interaction between developmental changes and the accumulation of risks across development places adolescents with previous service system involvement at risk for continued and deeper involvement with multiple service systems.

In summary, a developmental cascade framework describes a transactional process in which accumulated risks throughout development increases a child’s likelihood for subsequent multisystem involvement. To the extent that each service system that comes into contact with the child and family is able to meet their increasingly complex needs, multisystem involvement offers an opportunity for implementation of developmentally- and culturally-appropriate interventions. Because of the complex and intersecting needs of multisystem-involved youth, service systems need to go beyond treatment-as-usual approaches and consider the bidirectional and dynamic influences between youth and social contexts. However, in the context of multisystem involvement, a youth’s needs may be overlooked either because of inadequate assessment and tracking or because of diffused sense of responsibility across multiple service systems.

Systems Challenges to Addressing the Needs of Multisystem-Involved Youth

Policies, programs, and practices concerning multisystem-involved youth vary greatly across jurisdictions in the United States (Fromknecht, 2014). The National Council for Juvenile Justice (NCJJ), through its Juvenile Justice Geography, Policy, Practice, and Statistics program, documented state-level activities and practices with regard to multisystem-involved youth, specifically those involved in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Their report shows that 18 states have adopted variations of centralized policies and practices for multisystem-involved youth. For example, in 7 states, a single agency is responsible for the administration of services for multisystem-involved youth. This approach may reduce fragmentation of services through a greater degree of oversight and encourage collaboration between agencies through data sharing and other forms of interagency agreements. In 11 states, separate centralized agencies have oversight of policies and practices for multisystem-involved youth. Although this may also reduce fragmentation of services, such approach also relies heavily on shared goals and communication between agencies. A majority of the states (n = 33), however, have decentralized systems wherein administration of policies and practices are at the local level. Operation at the local level may allow agencies to better tailor their responses to youth’s needs; however, for these states, collaboration between agencies and coordination of services may be more challenging due to a lack of structural policies and practices.

The lack of structural relationships necessary to coordinate access to and delivery of services across systems may be due to legal regulations or different organizational capacities that limit information sharing across systems (Ross, 2009). Differences in philosophy and practice across systems can also impede effective collaboration across systems. For example, balancing the interests of community safety and rehabilitation is central to the juvenile justice system, and youth in this system may be viewed as perpetrators who must be held accountable for their behaviors (Haight, Bidwell, Marshall, & Khatiwoda, 2014; Piquero & Steinberg, 2010). This philosophy may not align with that of the behavioral health system, which is primarily oriented toward promoting the well-being of the child, and the child welfare system, which seeks to ensure the child’s safety and protection (Haight et al., 2014). These conflicting philosophies and practices may disrupt coordination efforts and exacerbate diffusion of responsibility for multisystem-involved youth and their families.

Utilizing data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW), Chuang and Wells (2010) examined the role of inter-agency collaboration in acquiring behavioral health services for youth involved in the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system. Their results indicate that almost four out of five multisystem-involved youth (79%) had substance use problems, but only 10 percent received outpatient substance abuse treatment. The lack of systematic collaboration across systems can also result in unnecessary disposition for youth concurrently involved in the child welfare system and juvenile justice system. In New York City, foster care youth accounted for just 2 percent of the general youth population, yet made up 15 percent of the detained youth population (Ross, 2009). Lack of collaboration and role confusion between agencies may also lead to substantial delay in release of resources and information, such that youth are held for longer periods in detention facilities even if their offense does not warrant such disposition (Ross, 2009).

These challenges place multisystem-involved youth at greater risk for poor outcomes than youth served in a single service system or youth in the general population. Huang et al. (2012) examined recidivism rates among 1,427 youth simultaneously involved in the child welfare system and juvenile justice system in Los Angeles County. They found that 56 percent of multisystem-involved youth vs. 41 percent of juvenile justice system-only youth were charged with a new offense within a five-year period. A notable proportion (32%) of multisystem-involved youth also had subsequent maltreatment referrals. These findings are consistent with those of Ryan et al. (2013) indicating that 61 percent of multisystem-involved youth vs. 51 percent of crossover youth and 49 percent of juvenile justice system-only youth recidivated within a three-year period. Notably, Black and Hispanic multisystem-involved youth were also more likely to be rearrested even after accounting for important individual and contextual risk factors.

Systems challenges may also be more pronounced for underserved populations of multisystem-involved youth, including transitional aged and sexual and gender minority youth, or those that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender/gender non-conforming. Although approximately 3–8 percent of children in the general United States population identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual, up to 19 percent of youth in foster care identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual (Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Choi, 2016; Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Nezhad, 2014). Transgender youth represent approximately 2 percent of the general population and six percent of youth in foster care (Wilson, & Kastanis, 2015; Wilson, et al., 2014). However, estimates may be higher as few child welfare jurisdictions collect data on youth’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Nor is this information collected in most juvenile detention systems. Emerging evidence suggests that sexual and gender minority youth are also disproportionately represented in juvenile detention centers and facilities with estimates around 13 percent (Majd, Marksamer, & Reyes, 2016).

Across the foster care and juvenile justice contexts, sexual and gender minority youth face additional challenges, including greater placement instability, longer lengths of stay, and more restrictive placements settings (for example, congregate care or group home) compared to their heterosexual peers (Wilson & Kastanis, 2015; Wilson, et al., 2014; Woronoff, Estrada, Sommer, & Marzullo, 2006). These youth are also subjected to the inappropriate use of restriction or confinement; withholding of medical or mental health services for transgender youth; and unethical practices including “conversion” therapies (Majd, et al., 2016; Estrada & Marksamer, 2006).

Transitional aged youth, or those growing out of childhood and into adulthood, also face unique challenges that have important implications for systems coordination and delivery of services (Wilens & Rosenbaum, 2013). For example, transitional aged youth in the child welfare system, or those that are reaching the age of majority and may leave foster care without having attained a permanent relationship, are at an increased risk for a range of negative outcomes including criminal justice involvement (Lee, Courtney & Tajima, 2014; Kolivoski, Shook, Goodkind, & Kim, 2014); homelessness (Shah, et al., 2016; Dworsky, Napolitano, & Courtney, 2013; Fowler, Toro, & Miles, 2009), substance abuse disorders (Pilowsky & Wu, 2006; Shin, 2004; Kohlenberg, Nordlund, Lowin & Treichler, 2002) and early parenthood (King, 2017; Shpiefel, Cascardi, & Dineen, 2017; Putnam-Hornstein & King, 2014). Transitional aged youth may also face challenges in discontinuity of behavioral health services and gaps in treatment as they transition into adulthood (Wilens & Rosenbaum, 2013). Extension of care services past the age of 18 is a promising policy and practice approach in supporting a healthy transition for these youth (Courtney et al., 2007; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006). However, there is a dearth of research on addressing heterogeneity in challenges, targeting services to needs, and systems collaboration for special populations of youth involved in multiple service systems.

Research and Practice Implications for Intervention Programs and Systems Development

Green (2012) described the epistemology of clinical practice in which practice-based knowledge informs theory and research, which in turn, informs practice. This “bidirectional translational algorithm” is central to the development of evidence-based practices and the implementation of effective programs and policies for public benefit. However, when it comes to multisystem-involved youth, the lack of basic information about prevalence, characteristics, multisystem involvement pathways, and successful interventions represents a significant barrier to knowledge generation to inform theory and practice. Increasingly, clinicians and policymakers are confronted with ever-growing challenges that they are ill-equipped to address when it comes to multisystem-involved youth because there is so little systematic knowledge available. This review has sought to present the available knowledge; below we discuss research and practice implications for clinical interventions and systems development in informing a bidirectional translational algorithm to promote successful interventions for multisystem-involved youth.

Intervention Programs

Essential to effective practice for multisystem-involved youth is adoption of a standardized and integrated screening procedure to identify youth concurrently served in multiple service systems. As noted earlier, there is currently no standardized and integrated approach within or across service systems to identify and track multisystem-involved youth (Herz et al., 2012). Although some jurisdictions have implemented screening procedures to identify multisystem involvement among youth who enter their system, the wide variation in these methods (for example, self-report, questionnaire or interview at intake, manual record searches) may not accurately capture multisystem-involved involvement, which may result in youth receiving inadequate or poorly coordinated services (Siegel & Lord, 2004). The lack of reliable information about multisystem involvement complicates the development of targeted evidence-based programs for this population. Standard assessment of multisystem involvement would enable clinicians and other practitioners to determine whether intended treatments for multisystem-involved youth and their families are compatible across systems.

Standardized and integrated screening will also facilitate decision-making for use of full assessment protocols in service planning, which is especially critical for multisystem-involved youth with complex needs (Ungar, 2015). Multisystem-involved youth are more likely to have experienced complex trauma or repetitive and prolonged exposure to multiple stressors that undermine their capacities for self-regulation and interpersonal relationships (Ford & Courtois, 2009; Ko et al., 2008). However, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) does not capture the developmental impact of complex trauma in children (Ford, Connor, & Hawke, 2009). Although children exposed to trauma may meet diagnostic criteria for other disorders in addition to PTSD, their challenges are often developmental, self-regulatory, and relational which, if not treated or addressed, increase lifelong risk for substance abuse or mental health problems and other health, legal, and family problems (Cook et al., 2005). Trauma-informed assessment instruments are thus critical in informing case management and delivery of trauma-informed care for children and youth served in multiple systems.

Targeted assessment and tracking of multisystem-involved youth will also enable clinicians and researchers to gather accurate data on the quality and effectiveness of evidence-based programs for youth served in multiple systems. Currently, such information is unavailable except for studies that specifically examine the effectiveness of treatments for youth with complex needs (Ungar, 2015; Howell et al., 2004). Despite the existence of numerous evidence-based programs for children and adolescents, we do not know which treatments are most effective in addressing the complex needs of multisystem-involved youth (Mitchell, 2011).

A developmental cascade framework suggests evidence-based programs that target broader family and system involvements may be most effective at reducing negative outcomes for multisystem-involved youth. For example, Multisystemic Therapy (MST; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2009), Functional Family Therapy (FFT; Alexander, 2008), Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Adolescents (MTFC-A; Chamberlain, 2003), or Wraparound Services (Clark & Clarke, 1996) are just a few examples of evidence-based programs that may be appropriate for addressing the challenges of multisystem-involved youth. The developmental cascade framework specifies how adverse family environments may trigger pathways to multisystem involvement as well as possible points of intervention and prevention. Family-focused evidence-based programs, particularly at the onset of system involvement, are more likely to be beneficial than other modes of intervention to address these challenges (Vries, Hoeve, Assink, Stams, & Asscher, 2015; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003; Cottrell & Boston, 2002).

Whereas family-focused interventions may be most appropriate during early childhood throughout adolescence, interventions that are developmentally-informed would also focus on strengthening relationships outside the family context. For adolescents who are involved in multiple services systems, this becomes particularly important when decisions are made in relation to case disposition (for example, released to a guardian vs. congregate care or secure commitment; Munson & Freundlich, 2005). A period wherein meaningful relationships are developed and forged, supporting positive connections with adults during adolescence is a potential mechanism for preventing negative outcomes among multisystem-involved youth. Research suggests that youth turn to prominent others in their lives, for example, peers (Allen, Chango, Szwedo, Schad, & Marston, 2012) and are more susceptible to negative pressures and risky behaviors (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005) when their relationship with their parents is negative or even harmful. Fostering positive relationships with others, including professionals (for example, mentors, case workers, treatment providers), may serve as a safeguard to stressful and troublesome relationships youth may have with their families and peers (Vidal, Oudekerk, Reppucci, & Woolard, 2015; Dubois, Holloway, & Valentine, 2002). However, the extent to which these programs and approaches can be adapted and tailored to the specific needs of multisystem-involved youth and their families, including underserved populations such as racial and ethnic minority youth, lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender/gender non-conforming youth, and transitional-aged youth, remains an empirical question.

Systems Development

Interagency collaboration is critical in the successful development and implementation of screening and assessment protocols and evidence-based programs for multisystem-involved youth. Currently, however, interagency collaboration and programming for multisystem-involved youth is the exception rather than the norm (Ungar, 2015; Miller et al., 2011; Ko et al., 2008; Howell et al., 2004). As indicated above, service systems often face organizational and philosophical barriers to facilitate interagency collaboration. What is needed are practice models that take into account these complexities and incorporate structures and processes integral to collaboration and coordination across service systems.

One of the most common frameworks used to implement change strategies for children and adolescents with complex needs is the systems of care model. The underlying principles of systems of care posit that services should be child-centered, family-focused, and community based with considerations for individualized, culturally-sensitive, and comprehensive array of services (Stroul & Friedman, 1986). In theory, the systems of care model provides an ideal philosophy by which services should be delivered. In practice, however, implementation of systems of care is limited by organizational and philosophical barriers that result in services that are only loosely linked and not sustained over time (Hernandez & Hodges, 2003; Farmer & Famer, 2001). Thus, effective collaboration and coordination requires grounding in shared responsibility across systems as well as the alignment of service systems toward common goals and targeted outcomes.

Building upon the principles of systems of care, a meta-systems approach may be helpful in understanding the complex and interrelated interactions among different service systems. This approach takes into account the “contexts and environments that surround and influence a child’s adaption and development” (Kazak et al., 2010, p.86). Examples of such contexts and environments include the family, cultural norms and values, service systems, and the school. Blending the systems of care framework with the meta-systems approach in advancing interagency collaboration for multisystem-involved youth acknowledges the dynamic interactions among different systems and emphasizes the need to have shared authority, leadership, and accountability to work together as a team for children across systems.

Consistent with the systems of care and meta-systems approaches, the Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM) was developed specifically to address the complex needs of multisystem-involved youth and families (Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, Georgetown University, 2015). The CYPM provides a framework for professionals from different service systems to coordinate, align, and promote evidence-based programs for multisystem-involved youth. One key feature of the CYPM is to establish multidisciplinary workgroups of stakeholders from different service sectors such as the law enforcement, behavioral health system, child welfare system, and juvenile justice system in order to create a more comprehensive intervention and treatment plan for multisystem-involved youth. The Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice also provides resources and tools for state and local jurisdictions to inform their work on multisystem-involved youth. Other programs share similar features, including Project Confirm in New York City, which seeks to facilitate effective and efficient communication between the child welfare system and juvenile justice system in order to reduce unnecessary detention of foster care youth (Conger & Ross, 2001). In another cross-system example, a multidisciplinary panel of stakeholders, including school administrators, the chief of police, juvenile justice judge, and directors of the child welfare system and the behavioral health system in Clayton County, Georgia convene regularly to discuss and develop appropriate practices for children and adolescents at-risk for involvement in the juvenile justice system (Teske, 2011). The initial evaluations of these programs show promising system-level changes, including improved communication across service systems (Ross, 2009), better integration of intervention plans for youth and their families (Haight et al., 2014), and reduced school-to-juvenile justice referrals, particularly among racial and ethnic minority students (Teske, 2011). Future research is needed to evaluate how these programs affect youth-level indicators of well-being and outcomes among multisystem-involved youth.

Finally, these and other system development efforts may require public agencies to adopt more collaborative approaches toward information sharing to inform identification and coordinated treatment efforts for multisystem-involved youth. One such tool that is increasingly being used to foster interagency collaboration and information sharing is the development of integrated data systems that link administrative records across public agencies (for example, child welfare, behavioral health, education, or juvenile justice). Such efforts may enhance the ability to identify youth who crossover, or at risk of crossing over, multiple systems (Putnam-Hortsein, Wood, Fluke, Yoshioka-Maxwell, & Berger, 2013), as well as providing a means of identifying patterns of service utilization and treatment outcomes across various service systems (Fantuzzo & Culhane, 2015). These data systems may also be leveraged to better understand the impact of system-level interventions on downstream costs associated with multisystem-involved youth.

Limitations

We note several limitations to keep in mind when interpreting the findings of this article. First, our review was limited by the available literature on multisystem involvement, which is constrained by a lack of shared definitions of youth with multisystem involvement and of tracking systems that provide reliable estimates of this population. Clarifying the definition of multisystem involvement will allow for better identification of youth involved in multiple service systems, their needs, and appropriate responses to address those needs.

Second, our scope was limited to multisystem involvement among youth in the United States. There is wide variation in how service systems operate within and across countries. As discussed previously, even within the United States, administration of policies and practices for multisystem-involved youth greatly varies by jurisdiction (Fromknecht, 2014). Our sole focus on United States youth helps temper the complexities associated with variations in practices across different service systems. Notably, however, there are few available studies and reports documenting the significant number of youth with complex needs concurrently served in multiple systems in other nations (see United Nations, 2014; Vostanis, 2010). Third, this article did not summarize socio-cultural factors (Braverman, Egerter, & Williams, 2011) or biological and genetic factors (Raine, 2008) that clearly also affect development and functioning among children and adolescents, including multisystem-involved youth. Further examination of these factors in relation to multisystem-involved youth is warranted.

Finally, although the developmental cascade offers an adaptable framework that takes into account both micro- and macro-level factors and influences across development, it is not without methodological limitations. In general, developmental cascade models require longitudinal data to test empirically (Masten & Cicchetti, 2005). Relatedly, repeated measures of key variables may be needed to adequately test the model. Although data collection and monitoring are important aspects of supporting agency policies and practices, public welfare agencies face significant challenges in sustaining and enhancing their data collection efforts (Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2014). Availability of data in various service systems is limited by the risk and needs assessment they use or youth outcomes that are of specific interest to the agency. Restrictions to data sharing between agencies may also amplify these challenges. Some of these limitations may be tempered by conducting longitudinal primary data collection involving multisystem-involved youth and their families. We do acknowledge, however, that longitudinal studies require significant investments of time and resources. Other methods that may be less-resource intensive include conducting case studies of multisystem-involved youth, which can also help facilitate development and improvement of a theoretical framework.

Because of these limitations, we recognize that testing the full developmental cascade framework presented in this article has barriers. However, we encourage innovation and collaboration across disciplines to examine different components of the framework with available data from various service systems or other resources. Multidisciplinary collaborations are also essential to strengthen the conceptualization of the developmental cascade framework of multisystem involvement and to gain a better understanding of the processes and mechanisms by which multisystem involvement operates across development. Cross-method collaboration and multi-method work can help bridge gaps in research, policy, and practice.

Conclusion

This article offers an integrated review of the literature by summarizing current knowledge on prevalence, characteristics, risk factors, and disparities of multisystem involvement among youth, and describing a developmental pathway of multisystem involvement and opportunities for intervention. Multisystem-involved youth are a vulnerable population that requires concurrent engagement in different service systems. A significant proportion of these youth come from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, and are characterized by disparities in service access and outcomes. Currently, there is no consistent and uniform method to track multisystem involvement. However, studies that have primarily used administrative data suggest that prevalence of multisystem involvement varies greatly by pathways to multisystem involvement and the degree of youth’s involvement with the juvenile justice system.

There are multiple pathways to multisystem involvement for youth that can be conceptualized by adopting a developmental cascade framework. This framework illustrates how the cascading effects of and continuity in exposure to risk factors across developmental periods may contribute to multisystem involvement. More importantly, a developmental cascade framework also identifies critical periods for intervention. We note that multisystem involvement typically starts with the child welfare system, consistent with the developmental context of exposure to risk factors during childhood (Stewart et al., 2008). Adverse family environment, including parental abuse and neglect, may contribute to a child’s socio-emotional difficulties and disruptive behaviors (Ryan & Testa. 2005; Chang et al., 2003). These challenges may require both the involvement of the child welfare and behavioral health systems to address issues related to child safety, permanency, and mental and behavioral health.

We also posit that system involvement pathways underscore the developmental growth and maturity of a child as well as other contextual influences related to the transactional characteristics of risk factors within and across development. A confluence of developmental changes, including impulsivity, susceptibility to peer pressure and influence, and transient nature and personality contribute to increased risk-taking behaviors in adolescence (Woolard, 2011). However, enhanced cognitive capacities in adolescence may impose assumptions of maturity and accountability when identifying an appropriate response to a problem behavior, some of these responses may be more restrictive than those offered in early and middle childhood (Woolard & Scott, 2009; Scott & Steinberg, 2008). Indeed, the risk for multisystem involvement with the juvenile justice system peaks around adolescence (Vidal et al., 2017).

The unique and complex needs of multisystem-involved youth call for intervention efforts that are not only focused on the youth’s specific needs, but also developmentally and culturally appropriate and trauma-informed. Developmentally-focused interventions must take into account the unique processes that characterize different periods of development. Culturally adapted interventions incorporate appropriate tailoring to address the distinct needs and perspectives of diverse cultural groups (Kumpfer et al, 2002), and trauma-informed care adopts evidence-based practices that recognize the elevated rates of traumatic experiences among multisystem-involved youth (Ko et al., 2008). Family-focused interventions that aim to prevent subsequent maltreatment through training in parental skills and coping with family stress may be most appropriate in early childhood. In adolescence, interventions that capitalize on forging positive connections with other adults in a youth’s life may provide complementary benefits to that of family-focused interventions. For example, trusting, caring, and respectful relationships with child welfare, juvenile justice, and behavioral health service workers may serve as protective factors against negative outcomes for multisystem-involved youth. For transitional-aged youth who are aging out of a service system, these professional relationships may also be helpful in building a network of resources for supportive services (for example, housing and employment) that are necessary for a successful transition into adulthood. Effective collaboration and coordination across service systems remain a significant challenge for professionals that serve multisystem-involved youth and their families, but are feasible and essential through shared responsibility across systems as well as the alignment of service systems toward common goals and targeted outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Erin Hoffman for her assistance in literature review.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32 DA 019426; Jacob Kraemer Tebes, Principal Investigator).

Biographies

Sarah Vidal is a Senior Study Director in the Child Welfare and Justice unit at Westat. Her research interests include adolescent development and functioning in the context of various systems of care and control, including the juvenile justice, child welfare, and behavioral health systems.

Christian M. Connell is an Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Studies and Associate Director of the Child Maltreatment Solutions Network at Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on understanding the effects of individual, family, and contextual risk and protective processes on behavioral health and child welfare outcomes for children and their families following maltreatment.

Dana M. Prince is an Assistant Professor in the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University. Her research interests include pathways to health and well-being among vulnerable adolescents and young adults, including low-income and system involved youth.

Jacob Kraemer Tebes is a Professor of Psychiatry (Psychology) and Director of the Division of Prevention and Community Research at Yale University School of Medicine. His research focuses on the promotion of resilience in at risk populations; the prevention of adolescent substance use; and the integration of cultural approaches into practice, research, and policy.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

SV conceptualized the framework discussed in the article, conducted literature review, and drafted the manuscript; CM participated in conceptualization of the framework and helped draft and reviewed the manuscript; DP helped draft and reviewed the manuscript; JKT participated in conceptualization of the framework and helped draft and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Sarah Vidal, Westat

Christian M. Connell, Pennsylvania State University

Dana M. Prince, Case Western Reserve University

Jacob Kraemer Tebes, Yale University School of Medicine

References

- Alexander JF. Functional family therapy (FFT) clinical training manual. Salt Lake City, UT: FFC INC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Chango J, Szwedo D, Schad M, Marston E. Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83(1):337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, Piquero AR, Bilchik S, Jackowski K, Greenwald MA, Epps N. Maltreatment, child welfare, and recidivism in a sample of deep-end crossover youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(4):625–654. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D, Leiber M, Johnson J. Contexts of decision making in the juvenile justice system: An organizational approach to understanding minority overrepresentation. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2010;8:213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Henry B, McGee RO, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: From age three to age fifteen. Child Development. 1995;66(1):55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Lexcen A, Goldweber A, Shulman E, Grisso T. Gender differences in mental health symptoms among delinquent and community youth. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5:287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Scholle SH, Mulvey E, Kelleher KJ. Predicting first time involvement in the juvenile justice system among emotionally disturbed youth receiving mental health services. Psychological Services. 2005;2(1):28–38. [Google Scholar]

- The Crossover Youth Practice Model. An abbreviated guide. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. Georgetown University; 2015. Available at http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/CYPM-Abbreviated-Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. The Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model: Features, outcomes, and progress in dissemination. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10(4):303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge K, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;7:598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang E, Wells R. The role of inter-agency collaboration in facilitating receipt of behavioral health services for youth involved with child welfare and juvenile justice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(12):1814–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. An odyssey of discovery: lessons learned through three decades of research on child maltreatment. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):731–741. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Resilient functioning in maltreated children–past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark H, Clarke R. Research on the wraparound process and individualized services for children with multisystem needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1996;5:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Clay K, Lingwall J, Stephens M., Jr . Do Schooling Laws Matter? Evidence from the Introduction of Compulsory Attendance Laws in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w18477. [Google Scholar]

- Conger D, Ross T. Reducing the foster care bias in juvenile detention decisions. Vera Institute of Justice; 2001. http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/Foster_care_bias.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Flaspohler P, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Changes in placement among children in foster care: A longitudinal study of child and case influences. The Social Service Review. 2006;80:398. doi: 10.1086/505554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, Van der Kolk B. Complex trauma. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell D, Boston P. Practitioner review: The effectiveness of systemic family therapy for children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:573–586. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Governments Justice Center. Measuring and using juvenile recidivism data to inform policy, practice, and resource allocation. 2014 Available at https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Measuring-and-Using-Juvenile-Recidivism-Data-to-Inform-Policy-Practice-and-Resource-Allocation.pdf.

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out- of-home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work. 2006;11(3):209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky AL, Cusick GR, Havlicek J, Perez A, Keller TE. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age. 2007:21. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Wen H, Druss BG. Improving access to mental health services for youth in the United States. JAMA. 2013;309(6):553–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Baker AJ, Anastasio E, Purcell J. Characteristics of children in residential treatment in New York State. Child Welfare. 2007;86:5–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Sorensen J. Disproportionate minority confinement of juveniles: A national examination of Black-White disparity in placements, 1997–2006. Crime and Delinquency. 2013;59:115–139. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Sionean C, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Oh MK. Parental monitoring: Association with adolescents’ risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1363–1368. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A, Howie P, Starling J. Psychopathology in female juvenile offenders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1150–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79(6):1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Malone P, Lansford J, Miller S, Pettit G, Bates J. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74(3):1–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Irwin L, Ramsay M, Ayduk O. Rejection sensitivity and girls’ aggression. In: Moretti M, Odgers C, Jackson M, editors. Girls and aggression. Contributing factors and intervention principles. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic; 2004. pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, Cooper H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(2):157–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1014628810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Yates T, Appleyard K, Van Dulmen M. The long-term consequences of maltreatment in the early years: A developmental pathway model to antisocial behavior. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice. 2002;5(4):249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada R, Marksamer J. The legal rights of LGBT youth in state custody: What child welfare and juvenile justice professionals need to know. Child Welfare. 2006;85:171–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Culhane DP, editors. Actionable intelligence: Using integrated data systems to achieve a more effective, efficient, and ethical government. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Angold A, Costello EJ. Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(1):60–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Farmer EM. Developmental science, systems of care, and prevention of emotional and behavioral problems in youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(2):171–181. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Connor DF, Hawke J. Complex trauma among psychiatrically impaired children: a cross-sectional, chart-review study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):1155–1163. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Courtois CA. Defining and understanding complex trauma and complex traumatic stress disorders. In: Ford JD, Courtois CA, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromknecht A. JJGPS StateScan. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice; 2014. Systems integration: Child welfare and juvenile ustice. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AR, Metraux S, Chen CC, Park JM, Culhane DP, Furstenberg FF. Patterns of multisystem service use and school dropout among seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-grade students. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(4):625–635. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk JA, Brown SA. Multi-sector complexity of systems of care for youth with mental health needs. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice. 2001;4(3):123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Landsverk JA, Lau AS. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;25(5–6):491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind S, Shook JJ, Kim KH, Pohlig RT, Herring DJ. From child welfare to juvenile justice race, gender, and system experiences. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2013;11:249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Graves KN, Frabutt JM, Shelton TL. Factors Associated With Mental Health and Juvenile Justice Involvement Among Children With Severe Emotional Disturbance. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5(2):147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. Editorial: Science, implementation, and implementation science. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:333–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T. Adolescent offenders with mental disorders. The Future of Children. 2008:143–164. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight WL, Bidwell LN, Marshall JM, Khatiwoda P. Implementing the Crossover Youth Practice Model in diverse contexts: Child welfare and juvenile justice professionals’ experiences of multisystem collaborations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;39:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Halemba G, Siegel G. Doorways to delinquency: Multi-system involvement of delinquent youth in King County (Seattle, WA) National Center for Juvenile Justice; Pittsburgh, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halemba GJ, Siegel GC, Lord RD, Zawacki S. Arizona dual jurisdiction study. 2004 http://nc.casaforchildren.org/files/public/community/judges/March_2010/Web_Resources/AZDualJurStudy.pdf.

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic therapy for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL. Who’s skipping school: Characteristics of truants in 8th and 10th grade. Journal of School Health. 2007;77(1):29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Hodges S. Building upon the theory of change for systems of care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Herz D, Lee P, Lutz L, Stewart M, Tuell J, Wiig J, … Kelly E. Addressing the needs of multi-system youth: Strengthening the connection between child welfare and juvenile justice. 2012 http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/pdfs/msy/AddressingtheNeedsofMultiSystemYouth.pdf.

- Herz DC, Ryan JP, Bilchik S. Challenges facing crossover youth: An examination of juvenile justice decision making and recidivism. Family Court Review. 2010;48(2):305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RB. Casey-CSSP Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare. 2007. An analysis of racial/ethnic disproportionality and disparity at the national, state, and county levels. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low–Income Mexican–American and Euro–American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74(1):189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch RA, Dierkhising CB, Herz DC. Educational risk, recidivism, and service access among youth involved in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;85:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JR. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(6):749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J, Kelly M, Palmer J, Mangum RL. Integrating child welfare, juvenile justice, and other agencies in a continuum of services. Child Welfare. 2004;83:143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Ryan JP, Herz D. The journey of dually-involved youth: The description and prediction of rereporting and recidivism. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Barth RP. From placement to prison: The path to adolescent incarceration from child welfare supervised foster or group care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22(7):493–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Hoagwood K, Weisz J, Hood K, Kratochwill T, Vargas L, Banez G. A meta-systems approach to evidence-based practice for children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 2010;65:85–97. doi: 10.1037/a0017784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley BT, Thornberry TP, Smith CA. In the wake of childhood maltreatment. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B. First births to maltreated adolescent girls: Differences associated with spending time in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2017;22(2):145–157. doi: 10.1177/1077559517701856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, Berkowitz SJ, Wilson C, Wong M, … Layne CM. Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39(4):396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlenberg E, Nordlund D, Lowin A, Treichler B. Adolescent Foster Care Survey. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2002. Alcohol and substance use among adolescents in foster care in Washington State: Results from the 1998–1999. [Google Scholar]