Significance Statement

Although lower extremity amputation is common among patients with ESRD and often portends a poor prognosis, little is known about end-of-life care among these patients. The authors’ analysis of a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries finds that patients with ESRD are far more likely than those without ESRD to undergo amputation during their final year of life. Among patients with ESRD, having a lower extremity amputation was associated with admission to and prolonged stays in acute and subacute care settings during their last year of life, as well as with dying in the hospital, discontinuing dialysis, and fewer days receiving hospice services. These findings likely signal unmet palliative care needs among seriously ill patients with ESRD who undergo lower extremity amputation.

Keywords: end-stage renal disease, end-of-life, amputation, surgery, vascular disease, palliative care

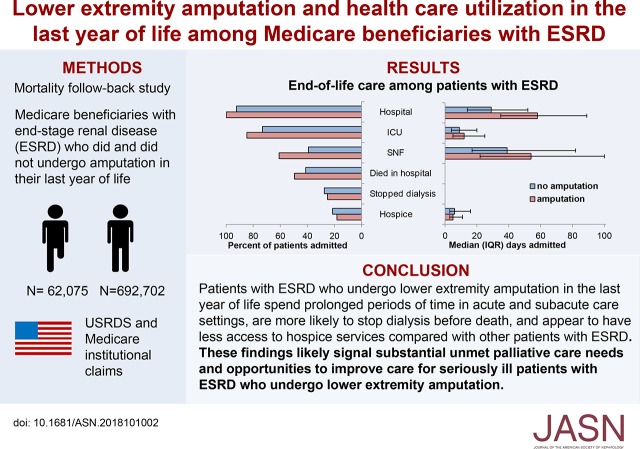

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Lower extremity amputation is common among patients with ESRD, and often portends a poor prognosis. However, little is known about end-of-life care among patients with ESRD who undergo amputation.

Methods

We conducted a mortality follow-back study of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who died in 2002 through 2014 to analyze patterns of lower extremity amputation in the last year of life compared with a parallel cohort of beneficiaries without ESRD. We also examined the relationship between amputation and end-of-life care among the patients with ESRD.

Results

Overall, 8% of 754,777 beneficiaries with ESRD underwent at least one lower extremity amputation in their last year of life compared with 1% of 958,412 beneficiaries without ESRD. Adjusted analyses of patients with ESRD showed that those who had undergone lower extremity amputation were substantially more likely than those who had not to have been admitted to—and to have had prolonged stays in—acute and subacute care settings during their final year of life. Amputation was also associated with a greater likelihood of dying in the hospital, dialysis discontinuation before death, and less time receiving hospice services.

Conclusions

Nearly one in ten patients with ESRD undergoes lower extremity amputation in their last year of life. These patients have prolonged stays in acute and subacute health care settings and appear to have limited access to hospice services. These findings likely signal unmet palliative care needs among seriously ill patients with ESRD who undergo amputation as well as opportunities to improve their care.

Patients with ESRD have an approximately ten-fold higher incidence of nontraumatic lower extremity amputation than those without ESRD, even after controlling for their higher prevalence of diabetes.1,2 Although amputation rates in patients with ESRD appear to be decreasing over time, their risk of death after amputation remains extremely high.3–8 After amputation, patients with ESRD are less likely than other patients to be able to ambulate or to use a prosthesis,9,10 are more likely to experience infection and poor wound healing,11 have higher rates of rehospitalization and reamputation,12–14 and spend more time in the hospital.9,15

Although advances in surgical and endovascular management have led to improvements in survival and limb salvage for patients with critical limb ischemia,16,17 outcomes after lower extremity revascularization remain poor among patients with CKD.18,19 Compared with other groups of patients with critical limb ischemia, lower extremity peripheral vascular disease is often more advanced by the time of surgical intervention in patients with kidney disease, and their disease tends to be more distal,1,20,21 placing them at increased risk for readmission, subsequent revascularization procedures, and future limb loss.22–25

Lower extremity peripheral vascular disease is a significant risk factor for mortality in patients with kidney disease, and has been incorporated into several prognostic models.26–28 Lower extremity amputation, in particular, is often a sentinel event for these patients, portending an extremely poor prognosis. In response, the Renal Physicians’ Association has recommended that lower extremity amputation in patients with ESRD on dialysis should trigger “discussions about end-of-life care and the benefits and burdens of ongoing dialysis.”29 However, few studies have sought to describe how commonly patients with ESRD undergo amputation near the end of life or the kind of care they receive. To address this knowledge gap, we designed a mortality follow-back study to describe: (1) the frequency and types of lower extremity amputation during the last year of life in patients with versus without ESRD; and (2) the relationship between lower extremity amputation and health care utilization during the last year of life among patients with ESRD.

Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

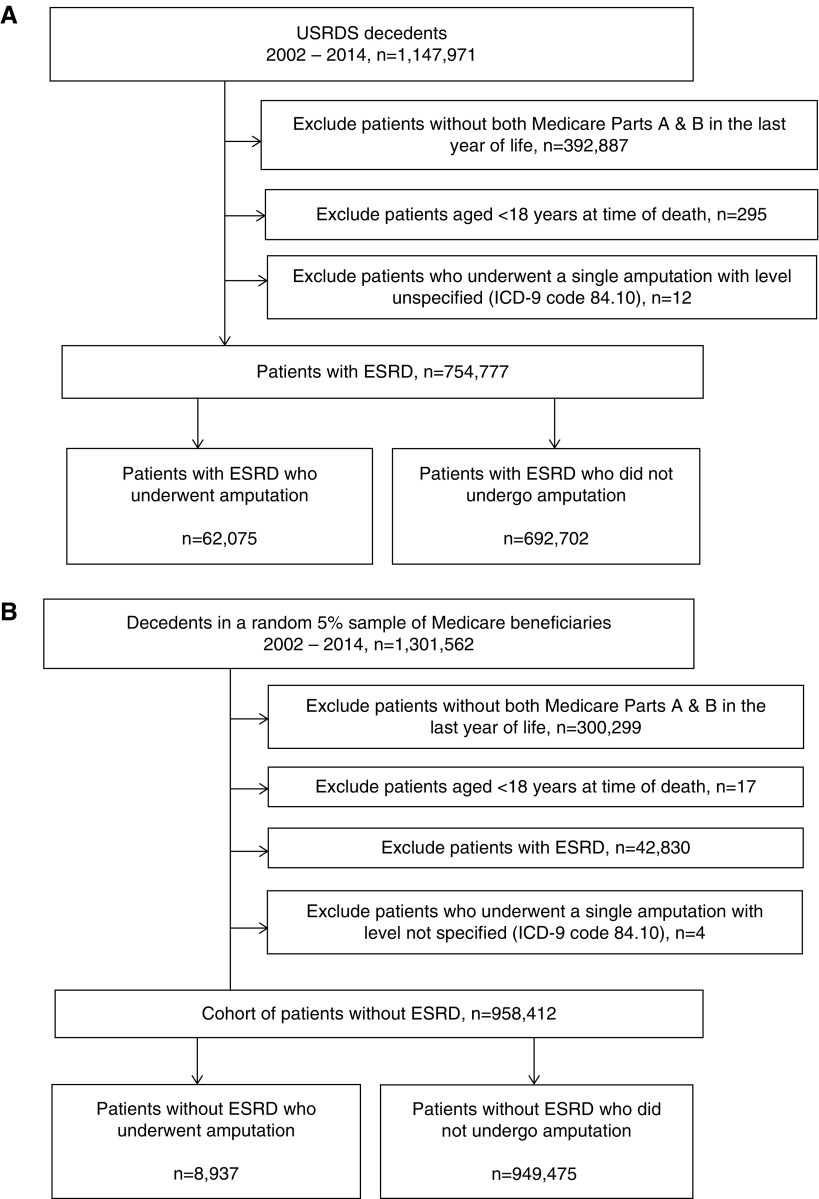

Using data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry for ESRD, we identified all patients who had been treated with maintenance dialysis or had received a kidney transplant before death, died between January of 2002 and December of 2014, were at least 18 years old at the time of death, and had Medicare Parts A and B coverage throughout their final year of life. Ninety percent of these patients were receiving in-center hemodialysis at the time of death. We defined receipt of lower extremity amputation in the last year of life using the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision procedure codes occurring during an inpatient hospital admission: 84.11, 84.12, 84.13, 84.14, 84.15, 84.16, 84.17, 84.18, or 84.19 (Supplemental Table 1).6,30 Twelve patients with a single amputation for which the level was not specified (84.10) were excluded. This yielded an analytic cohort of 62,075 Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who did, and 692,702 who did not undergo one or more lower extremity amputation in their last year of life (Figure 1A). To draw comparisons with patients without ESRD, we assembled a parallel cohort of Medicare beneficiaries without ESRD who died during the same time-period comprised of 8937 patients who did, and 949,475 who did not undergo lower extremity amputation in their last year of life (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Cohort derivation flow diagram. (A) Cohort derivation for Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD. (B) Cohort derivation for Medicare beneficiaries without ESRD. ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

To support a more detailed description of differences in patterns of amputation between beneficiaries with and without ESRD, we classified patients into seven mutually exclusive groups according to their highest level of amputation and whether they underwent more than one lower extremity amputation during the last year of life as follows: no amputation; single amputation at the level of the toe, below knee (including ankle), or above knee, respectively; or more than one amputation procedure with the highest level being toe, below knee (including ankle), or above knee, respectively (Supplemental Table 1).

Outcomes

We used a previously published approach on the basis of Medicare fee-for-service institutional claims31 to ascertain the percentage of patients with ESRD admitted to a hospital, intensive or coronary care unit (ICU), and/or skilled nursing facility (SNF) during their last year of life and the time spent in each of these settings; whether they were enrolled in hospice at the time of death and for how long; and whether they died in a hospital. We used the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Death Notification form (CMS 2746) to ascertain whether patients had discontinued dialysis before death.

Covariates

Using fee-for-service Medicare institutional claims, the Medicare Denominator File, and USRDS Standard Analysis Files, we ascertained each beneficiary’s age at the time of death, sex, race, Charlson comorbidity index (Quan score),32 and the following comorbid conditions during the year before death: cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, emphysema, and stroke.

Statistical Analyses

We described the characteristics of patients with and without ESRD who did and did not undergo a lower extremity amputation during their final year of life using percentages for categoric variables and mean values with SD or median values with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. We used logistic regression analysis to measure the association of ESRD with receipt of at least one lower extremity amputation in the last year of life. We measured this association both in the overall cohort and after stratification by age group, presence of diabetes, tertile of comorbidity index, and time-period of death. We used multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine the association of ESRD with each patient’s highest level of amputation and whether they underwent one versus more than one amputation in the last year of life. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, individual comorbid conditions, comorbidity index, and time-period of death.

Using percentages for categorical variables and median values with IQRs for continuous variables, we compared patterns of health care utilization during the last year of life among patients with ESRD on the basis of whether they had undergone amputation during this time frame. We used logistic regression analysis to examine the association of amputation with each measure of end-of-life care. Days spent in each health care setting were dichotomized at the median value for the group of all patients with ESRD admitted to that setting during their last year of life and multivariate analyses were conducted only among those admitted. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, individual comorbid conditions, comorbidity index, and time-period.

We conducted supplementary analyses to examine patterns of health care utilization stratified by each patient’s highest amputation level and whether they underwent one versus more than one amputation during their last year of life. We conducted subgroup analyses by age group (≤65, 66–80, and ≥81 years), presence of diabetes, tertile of comorbidity index, and time-period of death (2002–2005, 2006–2010, versus 2011–2014).

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata SE, Version 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Forest plots were constructed using R studio, Version 1.0.153 (RStudio, Inc.). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Results

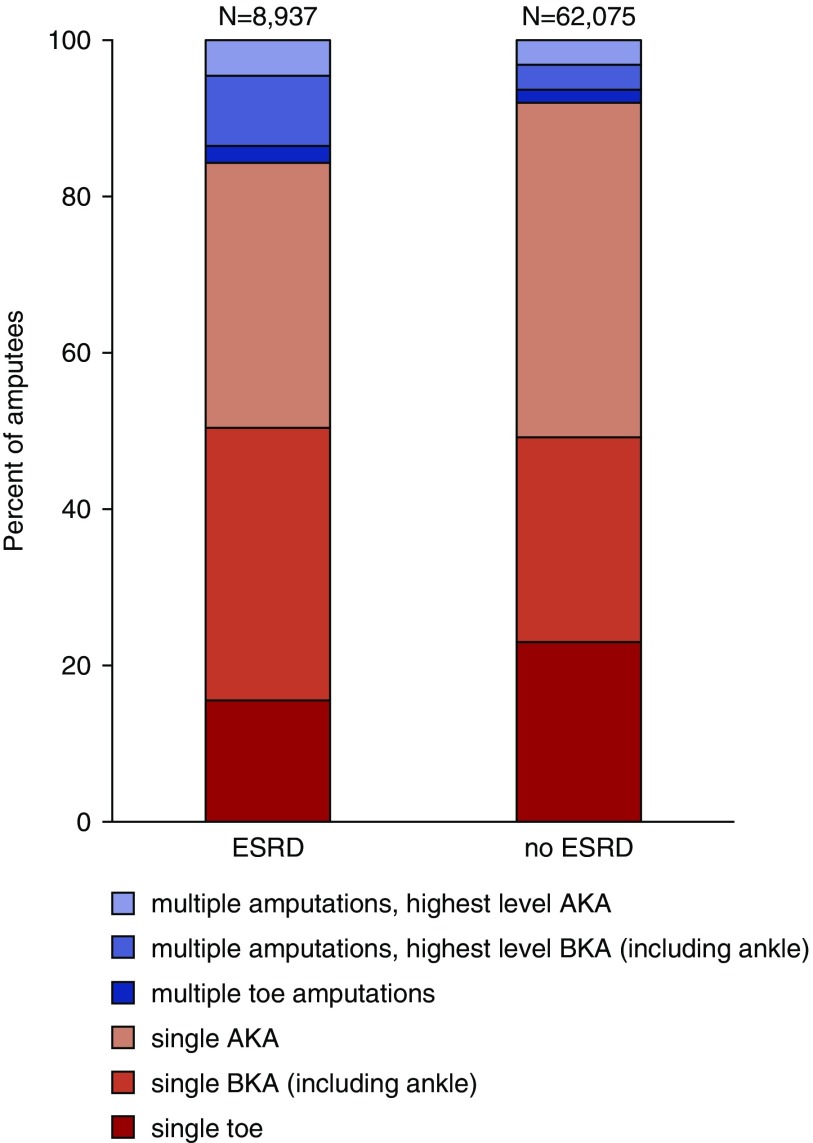

Compared with patients without ESRD, those with ESRD were younger, more likely to be male and to be black, had a higher prevalence of most comorbid conditions, and had a higher overall burden of comorbidity (Table 1). Eight-percent of patients with ESRD underwent at least one lower extremity amputation in their last year of life, compared with 1% of patients without ESRD. The most recent amputation occurred a median of 66 days before death (IQR 22–167) for patients with ESRD and a median of 60 days (IQR 13–163) before death for those without ESRD. Among beneficiaries with ESRD, those who had undergone an amputation were on average younger, more likely to be male, more likely to be black, had a higher prevalence of most comorbidities, and had a higher overall burden of comorbidity compared with those who did not undergo amputation. A relatively higher proportion of patients who had undergone amputation died in earlier years. Sixteen percent of those with ESRD who had undergone amputation in the last year of life had more than one amputation procedure during this time frame compared with 8% of those without ESRD (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by ESRD and amputation status

| Characteristic | ESRD | No ESRD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amputation | No Amputation | Amputation | No Amputation | |

| Total number of patients | 62,075 | 692,702 | 8937 | 949,475 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sex, % | ||||

| Female | 42.3 | 45.7 | 46.1 | 55.1 |

| Male | 57.7 | 54.2 | 53.9 | 44.9 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 60.4 | 68.7 | 74.2 | 87.2 |

| Black | 34.8 | 26.5 | 20.7 | 8.7 |

| Other race | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 4.1 |

| Age category, % | ||||

| ≤65 | 36.1 | 28.2 | 8.7 | 7.0 |

| 66–80 | 51.0 | 48.0 | 40.2 | 33.4 |

| ≥81 | 12.9 | 23.8 | 51.1 | 59.6 |

| Mean age (SD), yr | 67.7 (11.5) | 70.5 (13.1) | 79.0 (10.4) | 81.1 (11.1) |

| Comorbidities in the last yr of life, % | ||||

| Cancer | 18.0 | 27.3 | 22.0 | 35.0 |

| Congestive heart failure | 86.6 | 78.3 | 71.1 | 47.0 |

| Coronary heart disease | 87.2 | 74.5 | 71.4 | 45.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 95.6 | 74.6 | 72.7 | 35.0 |

| Emphysema | 49.3 | 48.8 | 48.4 | 40.1 |

| Stroke | 44.8 | 37.0 | 38.1 | 24.8 |

| Median Quan comorbidity index in the last yr (IQR) | 10 (8–11) | 9 (7–11) | 7 (5–9) | 4 (2–7) |

| Yr of death, % | ||||

| 2002–2005 | 37.2 | 30.2 | 40.8 | 32.3 |

| 2006–2010 | 37.4 | 38.7 | 36.1 | 37.8 |

| 2011–2014 | 25.4 | 31.1 | 23.2 | 29.9 |

Figure 2.

Highest level and frequency of amputation during the last year of life among patients with and without ESRD. AKA, above-knee amputation; BKA, below-knee amputation.

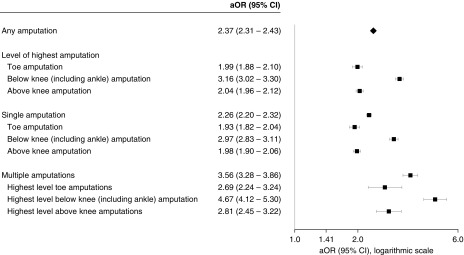

Adjusted Association of ESRD with Amputation

After adjusting for differences in measured patient characteristics and time-period of death, patients with ESRD were more than twice as likely as those without ESRD to have undergone at least one lower extremity amputation in their last year of life (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.4; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.3 to 2.4). A positive association between ESRD and amputation was noted in all subgroups examined (Supplemental Figure 1). In multinomial logistic regression analyses, ESRD was more strongly associated with receipt of multiple amputations (aOR, 3.6; 95% CI, 3.3 to 3.9) than with receipt of a single amputation (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 2.2 to 2.3) and more strongly associated with below-knee (including ankle) amputation (aOR, 3.2; 95% CI, 3.0 to 3.3) than with either toe (aOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.9 to 2.1) or above-knee (aOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 2.0 to 2.1) amputation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted association of ESRD with amputation level and frequency during the last year of life.

Association of Amputation with End-of-Life Care among Patients with ESRD

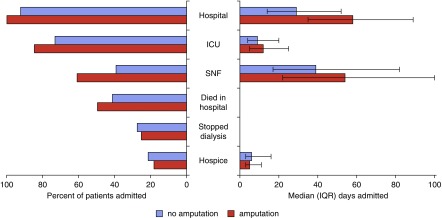

All Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who underwent at least one lower extremity amputation in their last year of life were admitted to a hospital during this time frame (versus 92% of patients with ESRD who did not undergo amputation), 85% were admitted to an ICU (versus 73%), and 61% were admitted to an SNF (versus 39%) (Figure 4). Fifty percent of patients with ESRD who underwent an amputation died in the hospital (versus 41%), 25% discontinued dialysis before death (versus 27%), and 18% were enrolled in hospice at the time of death (versus 21%). During their last year of life, beneficiaries with ESRD who underwent amputation spent a median of 58 days (IQR 35–89) in a hospital (versus 29 days for patients who did not undergo amputation, IQR 14–52), 12 days (IQR 5–25) in an ICU (versus 9 days, IQR 4–20), 54 days (IQR 22–100) in an SNF (versus 39 days, IQR 17–82), and 5 days (IQR 3–11) in hospice (versus 6 days, IQR 3–16).

Figure 4.

End-of-life care for patients with ESRD stratified by receipt of amputation. Percentage of patients with ESRD admitted to different care settings in the last year of life and percentage that died in a hospital and discontinued dialysis before death (left). Median time spent in each setting (right). Note: error bars around median days spent in each setting denote IQR.

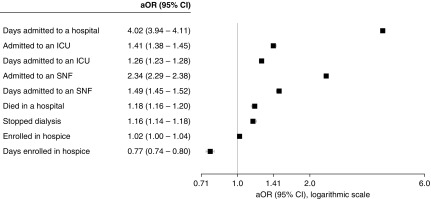

After adjusting for differences in measured patient characteristics and time-period of death, patients with ESRD who underwent amputation were more likely to be admitted to an ICU (aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.38 to 1.45) and SNF (aOR, 2.34; 95% CI, 2.29 to 2.38), more likely to die in the hospital (aOR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.20), and more likely to have discontinued dialysis before death (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.18). However, they were no more likely to have received hospice services than other patients with ESRD (aOR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.04). Among patients who underwent amputation, the number of days spent in a hospital, ICU, and SNF was more likely than for those who did not to exceed the median value for all cohort members admitted to that setting (hospital: aOR, 4.02; 95% CI, 3.94 to 4.11; ICU: aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.28; SNF: aOR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.45 to 1.52), whereas the number of days spent in hospice was less likely to exceed this value (aOR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.80) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Adjusted association of amputation with end-of-life health care utilization in patients with ESRD.

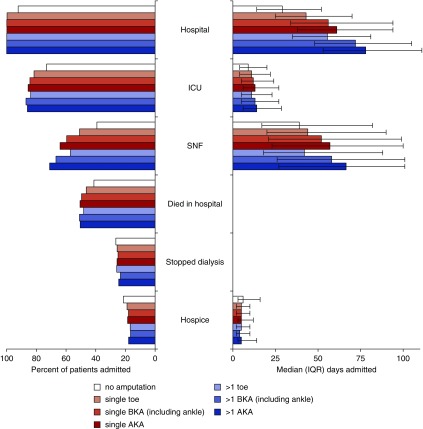

End-of-Life Care by Level and Frequency of Amputation among Patients with ESRD

Among patients with ESRD who underwent amputation, the percentage of those admitted to an SNF and the median number of days spent in a hospital, ICU, and/or SNF varied markedly by amputation level and frequency. Those who received higher level amputations and who received more than one amputation generally spent more time in acute and subacute settings than other patients. However, rates of dialysis discontinuation, hospice enrollment, and days spent in hospice varied little by level or number of amputations (Figure 6). Results were similar after adjustment for differences in measured baseline characteristics and time-period of death (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 6.

End-of-life care for patients with ESRD stratified by level and frequency of amputation. Percentage of patients with ESRD admitted to different care settings in the last year of life and percentage that died in a hospital and discontinued dialysis before death (left). Median time spent in each setting (right). Note: error bars around median days spent in each setting denote IQR. AKA, above knee-amputation; BKA, below-knee amputation.

Supplementary Analyses

The relationships between amputation status and end-of-life care were similar to the primary analysis in analyses stratified by tertile of comorbidity index, age group, presence of diabetes, and time-period of death. However, there were substantial differences across strata in patterns of end-of-life health care utilization (Supplemental Table 3). Receipt of inpatient, SNF, and hospice care was more common in patients with a higher versus lower burden of comorbidity. Younger patients spent longer periods of time in the hospital and ICU but less time in an SNF than older patients and were less likely to have enrolled in hospice. In more recent years, patients spent longer periods of time in an SNF and ICU, were less likely to die in the hospital, and were more likely to have enrolled in hospice compared with earlier years.

Discussion

Nearly one in ten Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD can expect to undergo a lower extremity amputation during their last year of life, a rate that is ten-fold higher than for Medicare beneficiaries without ESRD. Even after adjustment for differences in the prevalence of diabetes and other measured patient characteristics, beneficiaries with ESRD are more than twice as likely as those without ESRD to undergo at least one lower extremity amputation during their last year of life, and more than three times as likely to undergo multiple amputations during this time frame. Patients with ESRD who undergo amputation near the end of life spend substantially longer periods of time in acute and subacute care settings than other patients with ESRD, and are more likely to die in the hospital and to discontinue dialysis treatments before death. However, they are no more likely to receive hospice services and spend even shorter periods of time enrolled in hospice than other patients with ESRD.

Prior studies have demonstrated that patients with ESRD receive more intensive patterns of end-of-life care and less timely access to hospice services than other Medicare beneficiaries,33–37 and have substantial unmet palliative care needs compared with patients with other life-limiting chronic illnesses.34,38 Recognized barriers to receipt of hospice care in this population include difficulty identifying those who are approaching the end of life,28,39 limited patient and provider familiarity with palliative and hospice care,40–42 and restrictions on Medicare coverage for concurrent hospice and dialysis services.36,37,43 It is striking that despite widespread recognition that the presence of peripheral arterial disease and receipt of lower extremity amputation portend an exceedingly poor prognosis in this population,3–8,19,44 Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who undergo a lower extremity amputation near the end of their life receive more—not less—intensive patterns of care than other patients with ESRD. The significant amount of time that these patients spend in acute and subacute care settings during the last year of life is especially concerning because prior studies show that quality of end-of-life care for those who die in hospitals and nursing homes tends to be rated lower than for those who receive home hospice services.45–48 Similar to other populations, most patients with advanced kidney disease would prefer to die at home and would value relief of suffering over life prolongation if they were to become seriously ill.49,50

Although members of this cohort who underwent an amputation were more likely than other patients with ESRD to discontinue dialysis before death, they were no more likely to be enrolled in hospice at the time of death and spent shorter periods of time in hospice. Further, admission to hospice and time spent in hospice varied little by level or frequency of amputation despite large differences in intensity of care. There are several possible reasons why patients with ESRD who undergo lower extremity amputation may have more limited access to hospice services than other patients with ESRD regardless of the severity of their lower extremity disease. There may be a tendency to view lower extremity wounds and ischemia as isolated, fixable problems that can be treated with amputation, perhaps overlooking the broader prognostic significance of atherosclerotic disease of sufficient severity to warrant amputation in this population.34,51 A focus on recovery of lower extremity function (e.g., aggressive wound care and rehabilitation) after amputation may serve to further distract attention from the “bigger picture” of patients’ poor overall prognosis.9,10,52–54 Additionally, patients who undergo amputation spend a substantial portion of their last year of life in subacute care settings where there may be limited access to palliative care services.55

Prior qualitative work involving patients who have undergone lower extremity amputation suggests that they may experience unique kinds of physical, psychological, and sociocultural suffering as they struggle with social isolation, restricted lives, loss of control, and disruption of their core sense of self.56–58 Our findings provide the added insight that patients with ESRD are not only more likely than other Medicare beneficiaries to undergo lower extremity amputation during their last year of life, but that these patients spend a substantial portion of their final year of life in acute and subacute health care settings with limited access to hospice services.59

Limitations

Our results must be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, this study was restricted to fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Although most Medicare beneficiaries fall into this category, our findings may not be generalizable to non–fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries and to patients with other forms of health care coverage. Second, variable coding practices for planned two-stage amputations may mean that patients who received these procedures could be misclassified as having had more than one amputation. On the other hand, because we relied on inpatient institutional claims, we may have underestimated the frequency of multiple amputations occurring at the same level during the same hospitalization. Third, most patients with ESRD in this study were receiving in-center hemodialysis, thus our results may not reflect patterns of amputation and health care utilization among other segments of the ESRD population such as those receiving home hemodialysis, those receiving peritoneal dialysis, and those with a functioning kidney transplant. Although our results provide an objective measure of the frequency of amputation and patterns of end-of-life health care utilization in patients with ESRD, it is possible that differences in the frequency of amputation among patients with and without ESRD and in patterns of health care utilization among patients with ESRD who did and did not undergo amputation may reflect confounding by unmeasured factors.

Patients with ESRD are nearly ten times as likely as other Medicare beneficiaries to undergo lower extremity amputation within a year of death and are relatively more likely to undergo more than one amputation during this time frame. Although lower extremity amputation is widely recognized as a sentinel event portending a poor prognosis in patients with ESRD, these patients spend substantially longer periods of time in acute and subacute care settings during their final year of life and have more limited access to hospice services than other patients with ESRD. These findings suggest that there may be substantial unmet palliative care needs among seriously ill patients with ESRD who undergo lower extremity amputation as well as opportunities to improve their care.33–35,49,60–64

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U01DK102150 and 5T32DK007467-33).

The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or in decision to submit for publication. The interpretation of these data is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the opinion of the United States Renal Data System.

C.R.B., R.K., and A.M.O. designed the study; W.K. collected data; C.R.B., S.M.H., and A.M.O. analyzed data; C.R.B. made the figures; C.R.B., M.L.S., R.K., Y.N.H., M.E.M.R., and A.M.O. drafted and revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related perspective, “Staying the Course: Through End of Life in ESRD,” on pages 373–374.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018101002/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Subgroup analyses of the adjusted association of ESRD with lower extremity amputation.

Supplemental Table 1. Lower extremity amputation ICD-9 procedure codes.

Supplemental Table 2. Association of frequency and level of lower extremity amputation with patterns of end-of-life care in patients with ESRD.

Supplemental Table 3. Stratified analyses of the association of lower extremity amputation with patterns of end-of-life care in patients with ESRD.

References

- 1.O’Hare A, Johansen K: Lower-extremity peripheral arterial disease among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2838–2847, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Combe C, Albert JM, Bragg-Gresham JL, Andreucci VE, Disney A, Fukuhara S, et al.: The burden of amputation among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 54: 680–692, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Amos AM, Kupin WL, Reddy DJ, Elliott JP, et al.: Results of lower extremity amputations in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Vasc Surg 20: 14–19, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wukich DK, Ahn J, Raspovic KM, Gottschalk FA, La Fontaine J, Lavery LA: Comparison of transtibial amputations in diabetic patients with and without end-stage renal disease. Foot Ankle Int 38: 388–396, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathew A, Devereaux PJ, O’Hare A, Tonelli M, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Nevis IF, et al.: Chronic kidney disease and postoperative mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 73: 1069–1081, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggers PW, Gohdes D, Pugh J: Nontraumatic lower extremity amputations in the Medicare end-stage renal disease population. Kidney Int 56: 1524–1533, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aulivola B, Hile CN, Hamdan AD, Sheahan MG, Veraldi JR, Skillman JJ, et al.: Major lower extremity amputation: Outcome of a modern series. Arch Surg 139: 395–399, discussion 399, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franz D, Zheng Y, Leeper NJ, Chandra V, Montez-Rath M, Chang TI: Trends in rates of lower extremity amputation among patients with end-stage renal disease who receive dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 1025–1032, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arneja AS, Tamiji J, Hiebert BM, Tappia PS, Galimova L: Functional outcomes of patients with amputation receiving chronic dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 94: 257–268, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, Hamontree SE, Cull DL, Messich HS, et al.: Preoperative clinical factors predict postoperative functional outcomes after major lower limb amputation: An analysis of 553 consecutive patients. J Vasc Surg 42: 227–235, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landry GJ, Silverman DA, Liem TK, Mitchell EL, Moneta GL: Predictors of healing and functional outcome following transmetatarsal amputations. Arch Surg 146: 1005–1009, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien PJ, Cox MW, Shortell CK, Scarborough JE. Risk factors for early failure of surgical amputations: An analysis of 8,878 isolated lower extremity amputation procedures. J Am Coll Surg 216: 836–842, discussion 842–844, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaulieu RJ, Grimm JC, Lyu H, Abularrage CJ, Perler BA: Rates and predictors of readmission after minor lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg 62: 101–105, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masoomi R, Shah Z, Quint C, Hance K, Vamanan K, Prasad A,et al.: A nationwide analysis of 30-day readmissions related to critical limb ischemia. Vascular 26: 239–249, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry AJ, Hevelone ND, Hawkins AT, Watkins MT, Belkin M, Nguyen LL: Factors predicting resource utilization and survival after major amputation. J Vasc Surg 57: 784–790, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White CJ, Gray WA: Endovascular therapies for peripheral arterial disease: An evidence-based review. Circulation 116: 2203–2215, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss LK, et al.: American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology; Society for Vascular Medicine; Society for Vascular Surgery : 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (updating the 2005 guideline): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 79: 501–531, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallon JM, Goodney PP, Stone DH, Patel VI, Nolan BW, Kalish JA, et al.: Vascular Study Group of New England : Outcomes of lower extremity revascularization among the hemodialysis-dependent. J Vasc Surg 62: 1183–1191.e1, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie JX, Glorioso TJ, Dattilo PB, Aggarwal V, Ho PM, Barón AE, et al.: Effect of chronic kidney disease on mortality in patients who underwent lower extremity peripheral vascular intervention. Am J Cardiol 119: 669–674, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abou-Hassan N, Tantisattamo E, D’Orsi ET, O’Neill WC: The clinical significance of medial arterial calcification in end-stage renal disease in women. Kidney Int 87: 195–199, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Shlipak MG, Sen S, Chren MM: Impact of renal insufficiency on mortality in advanced lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 514–519, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao A, Baldwin M, Cornwall J, Marin M, Faries P, Vouyouka A: Contemporary outcomes of surgical revascularization of the lower extremity in patients on dialysis. J Vasc Surg 66: 167–177, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secemsky EA, Schermerhorn M, Carroll BJ, Kennedy KF, Shen C, Valsdottir LR, et al.: Readmissions after revascularization procedures for peripheral arterial disease: A nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med 168: 93–99, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal S, Sud K, Shishehbor MH: Nationwide trends of hospital admission and outcomes among critical limb ischemia patients: From 2003-2011. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 1901–1913, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolte D, Kennedy KF, Shishehbor MH, Abbott JD, Khera S, Soukas P, et al.: Thirty-day readmissions after endovascular or surgical therapy for critical limb ischemia: Analysis of the 2013 to 2014 nationwide readmissions databases. Circulation 136: 167–176, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, Allot V, Esnault V, Frimat L, et al.: French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry : A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1553–1561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couchoud CG, Beuscart JB, Aldigier JC, Brunet PJ, Moranne OP; REIN Registry : Development of a risk stratification algorithm to improve patient-centered care and decision making for incident elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 88: 1178–1186, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ: Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 72–79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renal Physicians Association : Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality : PQI #16 Rate of lower extremity amputation among patients with diabetes. 2012. Available at: https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Downloads/Modules/PQI/V44/TechSpecs/PQI%2016%20Rate%20of%20Lower-Extremity%20Amputation%20Diabetes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.USRDS: 2017 Annual Data Report: Chapter 12: End-of-life care for patients with end-stage renal disease: 2000–2014, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al.: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43: 1130–1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH: Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1248–1255, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachterman MW, Hailpern SM, Keating NL, Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM: Association between hospice length of stay, health care utilization, and Medicare costs at the end of life among patients who received maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 792–799, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Hare AM, Hailpern SM, Wachterman M, Kreuter W, Katz R, Hall YN, et al.: Hospice use and end-of-life spending trajectories in Medicare beneficiaries on hemodialysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 37: 980–987, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culp S, Lupu D, Arenella C, Armistead N, Moss AH: Unmet supportive care needs in U.S. dialysis centers and lack of knowledge of available resources to address them. J Pain Symptom Manage 51: 756–761.e2, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P: How accurate is the ‘Surprise Question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 15: 139, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Koffman J: Knowledge of and attitudes towards palliative care and hospice services among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. BMJ Support Palliat Care 6: 66–74, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson KF, Bhargava J, Bachelder R, Bova-Collis R, Moss AH. Hospice and ESRD: Knowledge deficits and underutilization of program benefits. Nephrol Nurs J. 35: 461–466, 502; quiz 467–468, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1256–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, Fischer MJ, Germain MJ, Jassal SV, et al.: Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : A palliative approach to dialysis care: A patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2203–2209, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Renal Data System : USRDS annual data report 2016, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, et al.: Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 291: 88–93, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG: Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol 28: 4457–4464, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, et al.: Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 309: 470–477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Kahn KL, Ritchie CS, et al.: Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA 315: 284–292, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, et al.: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tinetti ME, Fried T: The end of the disease era. Am J Med 116: 179–185, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilden LB, Williams BR, Tucker RO, MacLennan PA, Ritchie CS: Surgeons’ attitudes and practices in the utilization of palliative and supportive care services for patients with a sudden advanced illness. J Palliat Med 12: 1037–1042, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mosenthal AC, Weissman DE, Curtis JR, Hays RM, Lustbader DR, Mulkerin C, et al.: Integrating palliative care in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit: A report from the Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit (IPAL-ICU) project advisory board and the center to advance palliative care. Crit Care Med 40: 1199–1206, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bateni SB, Canter RJ, Meyers FJ, Galante JM, Bold RJ: Palliative care Training and decision-making for patients with advanced cancer: A comparison of surgeons and medical physicians [published online ahead of print April 27, 2018]. Surgery 10.1016/j.surg.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lester PE, Stefanacci RG, Feuerman M: Prevalence and description of palliative care in US nursing homes: A descriptive study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 33: 171–177, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charmaz K: Loss of self: A fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 5: 168–195, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu F, Williams RM, Liu HE, Chien NH: The lived experience of persons with lower extremity amputation. J Clin Nurs 19: 2152–2161, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madsen UR, Hommel A, Bååth C, Berthelsen CB: Pendulating-A grounded theory explaining patients’ behavior shortly after having a leg amputated due to vascular disease. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 11: 32739, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith J: The malady of boredom. theBMJopinion, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, McCorkle R, Bradley EH: Hospices’ enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 31: 2690–2698, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reinke LF, Meier DE: Research priorities in subspecialty palliative care: Policy initiatives. J Palliat Med 20: 813–820, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murtagh FE, Preston M, Higginson I: Patterns of dying: Palliative care for non-malignant disease. Clin Med (Lond) 4: 39–44, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holley JL: Palliative care in end-stage renal disease: Illness trajectories, communication, and hospice use. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 402–408, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holley JL: Advance care planning in CKD/ESRD: An evolving process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1033–1038, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.