Abstract

The Gelberg-Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations was applied to understand vulnerable Appalachian women’s (N = 400) utilization of addiction treatment. A secondary data analyses included multiple multivariate analyses. Strongest correlates of treatment utilization included ever injecting drugs (OR = 2.77), limited availability of substance abuse treatment facilities (OR = 2.03), and invalidated violence abuse claims (OR = 2.12). This study contributes theory-driven research to the greater social work addiction literature by confirming that vulnerable domains related to substance abuse treatment utilization warrant unique considerations compared to non-vulnerable domains. Findings also highlight the importance of understanding the unique role that cultural factors play in treatment utilization among Appalachian women. Inferences relevant to clinicians and policymakers are discussed.

Keywords: Rural women, substance use treatment, vulnerable populations, drug use, treatment utilization, addiction

Substance abuse has been identified as a public health crisis in the rural United States; yet, the patterns of substance abuse treatment utilization among vulnerable rural drug abusers have not been widely examined (Fortney & Booth, 2015). When comparing rural to urban settings, rural areas have greater prevalence rates of substance abuse (Jackson & Shannon, 2012; Shannon, Havens, & Hays, 2010; Small, Curran, & Booth, 2010). Along with the high prevalence of substance abuse, rural areas also have unique challenges to providing recovery services. For example, rural communities are more likely to have limited health service providers, and if recovery services are available, utilization of services can be complicated by client transportation challenges (Beardsley, Wish, Fitzelle, O’Grady, & Arria, 2003; Pullen & Oser, 2014).

In addition to the unique challenges of providing substance abuse treatment in rural communities, there are also regional (e.g., rural southeast) and demographic (e.g., vulnerable populations) differences in the prevalence of substance use disorders and the need for services (Oser et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 1997; Schoeneberger et al., 2006; Shannon, Havens, Mateyoke-Scrivner, & Walker, 2009; & Varga & Surratt, 2014). For instance, illicit use of prescription opioids is more prevalent in the Southeastern rural areas of the U.S., and rural areas have also beheld a pronounced increase in injection drug use (IDU) in recent years (Reifler et al., 2012; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015). Havens and colleagues (2006) found that the high rate of opioid prescriptions in rural Kentucky was correlated with regions that were classified as economically distressed, which was operationally defined as poverty, fewer local treatment resources, and higher rates of disability.

In rural Kentucky communities, substance abuse remains a growing public health concern, with specific emphasis placed on nonmedical opioid abuse, heroin, and co-occurring IDU (Havens et al., 2011; Keyes et al., 2014; Staton-Tindall, 2015). When compared nationally, this region ranks among the highest in the country for rates of prescription drug abuse, and rural residents have been found to be significantly more likely to abuse prescription drugs as compared to urban residents (Zhang et al., 2008; Young, Havens, & Leukefeld, 2010).

In recent years, the rise in IDU in the Appalachian region has elevated the public health risk. In Kentucky, by 2002 approximately 16% of self-reported drug abusers indicated having ever injected any drug (Leukefeld et al., 2002). Those injection prevalence rates (44.3%) have grown considerably since the mid-2000’s and are higher among Appalachian Kentucky samples of opiate abusers (Havens et al., 2007; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015). Taken together, several studies have supported the notion that drug abuse in rural regions is more prevalent and at-risk injection practices are more frequent when compared to urban drug abuse (Havens, Walker, & Leukefeld, 2007).

Women living in rural areas face unique challenges to attaining substance abuse treatment (Fortney et al., 2011; Staton-Tindall et al., 2007). For instance, rural areas have limited behavioral health services available (Gamm, Hutchinson, Dabney, & Dorsey, 2003); less resources to financially supplement treatment services (Staton-Tindall, Duvall, Leukefeld, & Oser, 2007); greater social stigma toward treatment (Browne et al., 2016); and are lacking adequate transportation to access treatment services (Beardsley et al., 2003).

However, there remains a considerable literature gap regarding the factors of treatment utilization among women from rural communities- especially studies that analyze a specific population sample, such as vulnerable Appalachian women. Also, the prevalence of substance abuse in this region of Appalachia has been identified as a public health epidemic; therefore, an understanding of the pathways to treatment utilization among a vulnerable population is of particular urgency (Abbasi, 2016; Anglin, 2016; Meldrum, 2016).

A Vulnerable Population: Rural Appalachian Women

One vulnerable demographic group that has been affected at a greater proportion by the mentioned rural drug trends are women; more specifically, economically disadvantaged rural women (Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), 2016; Browne, 2016; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015a; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015b). Economic distress increases the likelihood that individuals from this Appalachian region will have low social capital, greater health disparities, and limited environmental resources (Marmot & Bell, 2009). For drug-using women in Appalachian Kentucky, the economic and substance abuse problems in the region are compounded by co-occurring mental and physical health concerns, low health literacy regarding drug abuse, and the scarcity of treatment centers and/or resources (Havens et al., 2006; Snell-Rood, Staton-Tindall, & Victor, 2015).

Moreover, this vulnerability increases the likelihood of numerous health issues including among others, substance abuse and co-occurring related health issues (Varga & Surratt, 2014; Webster et al., 2006). With the idea that utilization of treatment services may reduce some of these significant health disparities, it is important to better understand the factors associated with substance abuse treatment utilization among this vulnerable group of women. To that end, this study applied an empirically supported theoretical framework – Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg, Andersen, & Leake, 2000) – as an analytical and conceptual guide to build upon the existing substance abuse treatment utilization literature base. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to apply this theoretical model to a sample of vulnerable women from rural Appalachia.

Theoretical Framework

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations, as first introduced by Gelberg and colleagues (2000), is a theoretical framework for understanding service utilization. This theoretical framework was built on the framework of the original Behavioral Model of Health Service Use (Andersen, 1968, 1995), which aimed to broadly explain factors relevant to individuals’ utilization of health and behavioral health services. Andersen’s (1968) original Behavioral Model has evolved over the past several decades. The original model examined individual-level factors that still function as the general model structure. These factors include: 1) Predisposing factors; 2) Enabling Factors; and 3) Need factors. Predisposing factors include individual factors that might exist prior to an illness and may influence health service behavior (Andersen, 1968, 1995). Enabling factors include factors might facilitate health service utilization (Andersen, 1968, 1995). Need factors, the third component in the model, include health and illness factors that might influence an individual to utilize health services (Andersen, 1968, 1995).

In the 1970’s Phase 2 of the Behavioral Model was developed to include the health care system as a predictor of health service utilization. Phase 3 was developed in the 1990’s to account for personal characteristics that might impact the maintenance and improvement in health status (Andersen 1995; Gelberg, 2000). Despite the advancement of the original Behavioral Model (Andersen, 1968, 1995), the model had little effectiveness in succinctly identifying factors that might make a population vulnerable, and how those vulnerable factors may affect the health status and health service utilization. These limitations provided the impetus for Gelberg and colleagues (2000) to revise and expand Andersen’s (1968, 1995) original Behavioral Model to incorporate factors to consider when examining the use of health services and health services outcomes among vulnerable populations.

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations was designed to assess whether the factors that make a population vulnerable might also impact their use of health services (Gelberg et al., 2000). Similar components of both models include identifying predictors of individuals’ utilization of health services in three domains: 1) Predisposing factors, 2) Enabling factors, and 3) Need or current illness factors (Andersen, 1968, 1995). This study will incorporate the modifications specified in the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) to understand substance abuse treatment utilization factors for rural Appalachian women. For clarity, in this study variables that are labeled “Traditional” refers to variables in the original Behavioral Model of Health Service Use, while “Vulnerable” refers to variables in the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations.

Predisposing traditional

factors in Anderson’s original model included individual demographic factors that exist prior to treatment utilization, such as age, gender, race, marital status, income, and education (Anderson, 1968, 1995). Predisposing vulnerable factors typically include past involvement in the criminal justice system, sexual orientation, religiosity, and victimization history (i.e., childhood abuse, physical abuse as an adult, and sexual abuse as an adult) – as identified in previous research (Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016; Teruya et al., 2010; Varga & Surratt, 2014). One qualitative study found that rural women reported that their lifetime experiences of emotional, sexual, and physical victimization was a barrier to treatment (Staton-Tindall, Leukefeld, & Logan, 2001). In addition, involvement in the criminal justice system has been identified as both a barrier and an access portal to treatment. For instance, Warner and Leukefeld (2001) found that a key determinate for not seeking treatment among Kentucky prisoners was because they did not feel they had a problem; however, data from the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) found that rural treatment centers were more likely to have treatment referrals made from the criminal justice system (ARC, 2016).

Enabling traditional

factors to have been found to increase the likelihood of accessing treatment (Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016; Rhoades, Winetrobe, & Rice, 2014; Varga & Surratt, 2014). Factors such as social support (Cucciare et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016), regular sources of health care (Browne et al., 2016), and other barriers not otherwise specified (e.g., stigma of treatment, and access to health insurance) (Appalachian Regional Commission, 2016; Schoeneberger, Leukefeld, Hiller, & Godlaski, 2006). In addition, researchers have found that drug-using women with more positive attitudes regarding treatment services resulted in a greater likelihood of help-seeking behavior (Segal, Coolidge, Mincic, & O’Riley, 2005).

Enabling vulnerable

factors include public benefits, disability status, and the distance needed to travel to treatment, along with the availability of adequate transportation. For rural individuals, public benefits may be limited, and treatment centers are usually located far distances where public transportation is often scarce for most individuals (Browne et al., 2016; ARC, 2016). A regional factor that is relevant to Appalachian women that may facilitate their utilization of substance abuse treatment is court ordered treatment (ARC, 2016). That is, individuals in rural treatment centers – particularly in Appalachia – were more likely to be in treatment due to a court order. There is a relatively high rate of drug related arrests (e.g., possession of illicit substance, drug trafficking) in the Appalachian region, and while these drug charges place a heavy burden on individuals, several researchers have found that a period of incarceration is a key opportunity to provide a substance abuse intervention to rural Appalachian citizens (Kubiak et al., 2006; Staton-Tindall et al., 2007; Warner & Leukefeld, 2001).

Need traditional

factors have been measured as psychological and physical heath factors, self-reported health rating (e.g., an individual’s readiness for change), the number of times an individual has a serious illness, and the presence of chronic health conditions (Andersen, 1968, 1995; Gelberg et al., 2000; Jeong, Pepler, Motz, DeMarchi, Espinet, 2015; Webster, Leukefeld, Staton-Tindall, Hiller, Garrity, & Narevic, 2005). In addition, past research has found that individuals with co-morbid health conditions actively access treatment centers more frequently (Gelberg et al., 2000).

Need vulnerable

factors include negative health factors that are more likely to afflict individuals in a vulnerable population. For instance, health issues such as mental illness (James & Glaze, 2006; Rhoades et al., 2014; Teruya et al., 2010; Webster et al., 2006), IDU (Oser et al., 2011; Varga & Surratt, 2014), and infectious diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C, sexually transmitted infections), are more prevalent among vulnerable groups (Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016). For women, previous studies have found that need vulnerable factors increase the likelihood that an individual will utilize treatment services (Teruya et al., 2010).

Current Study

This study responds to a significant gap in the literature in understanding of correlates of substance abuse treatment utilization among a high-risk, vulnerable, and understudied group of drug abusers –rural women in Appalachia. This study will utilize the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations to understand a specific health service utilization – substance abuse treatment. The conceptual foci of this study includes: 1) a descriptive profile of rural Appalachian women’s drug abuse history and within the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations; 2) a series of bivariate analyses of traditional and vulnerable variables to determine which variables within the theoretical model are significant correlates of substance abuse treatment utilization; and 3) a series of multivariate regression analyses to understand the unique contribution that vulnerable model factors had on substance abuse treatment utilization.

METHODS

Participants

This study used secondary data from a larger parent study (Staton, 01DA0338666) which focused on high risk drug abuse and risky sexual practices among a randomly selected group of 400 rural women from local rural jails in Appalachia (Staton-Tindall et al., 2015a; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015b). To enroll in the study, participants had to meet the following eligibility criteria: (1) National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) modified Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) (NIDA, 2010) scores of four or greater indicating need for substance abuse intervention; (2) engaged in at least one high risk sexual practice in the three months before jail; (3) resided in a designated Appalachian county before incarceration; and (4) indicated a voluntary willingness to participate in the study.

Procedure

All study recruitment and data collection procedures were approved by the university IRB and protected under a federal Certificate of Confidentiality. Drug-using women were recruited from three rural jail facilities located in Appalachian counties. The jails were similar regarding size, female populations, and availability of programming and resources.

Consent for participation in the project was provided by all participants before study screening procedures. During the 32-month study recruitment, 688 women were randomly selected from the target jails for study screening. Study screening took place in a large group room in the jail and included measures to assess substance abuse (NM-ASSIST, NIDA, 2009), risky sexual practices (Wechsberg, 1998), and voluntary willingness to participate. Following the screening session, eligible women (n=440) were invited to participate in a more in-depth baseline interview within a period of two weeks to assess their substance abuse history, risky sexual practices, history of substance abuse treatment, attitudes toward the health care system, and overall health. During the two-week period between the time of study screening and in-depth interviews, 40 women were released early. Interviews were conducted with 400 women by female research staff from the local Appalachian area, who were trained on human subjects protections and jail facility policies and procedures prior to study implementation. Participants were paid $25 for the baseline interview.

MEASURES

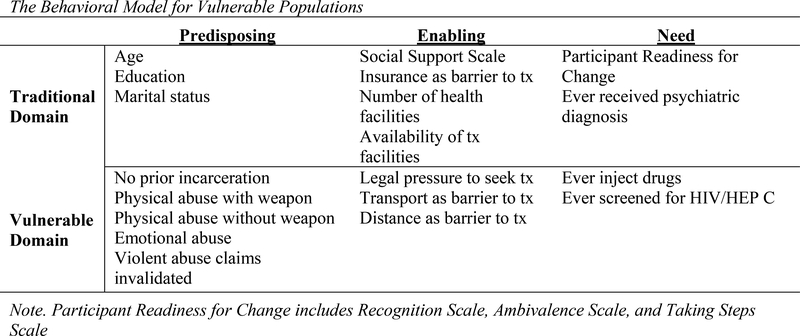

In the current study examining rural vulnerable women from Appalachia, variables are organized in the theoretical domains of the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: 1) predisposing traditional and vulnerable factors; 2) enabling traditional and vulnerable factors; and 3) need traditional and vulnerable factors. These domains do include some factors that are recognized in Andersen’s (1968, 1995) original Behavioral Model, along with additional measures that are relevant to the vulnerabilities of rural Appalachian women (Gelberg et al., 2000). Figure 1 presents a summarized breakdown of the traditional and vulnerable theoretical domains used in the present study.

Figure 1.

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations

The Global Appraisal of Individual Need–Intake version (GAIN) is a standardized instrument package administered for research purposes only, and intended to support clinical decision-making for potential diagnoses, placement, treatment planning, and service use (Dennis, 2010). This study used elect subsections of the GAIN for measurement purposes, and specific descriptions of those measures are described in the following sections.

Dependent Variable: Substance Abuse Treatment Utilization

The outcome variable was the participants’ utilization of substance abuse treatment prior to their most recent incarceration period. It was calculated as any treatment (1) compared to no treatment (0) where all treatment types were collapsed into one variable. The types of substance abuse treatment included: outpatient treatment, methadone maintenance, intensive outpatient, inpatient, correction-based/Substance Abuse Program (SAP), and peer-support recovery program (excluding Alcoholics/Narcotics Anonymous programs).

Predisposing Factors

Predisposing Traditional:

Predisposing traditional factors were measured by participant age, education, and marital status. Participant age (i.e., number of years) and education (i.e., number of years completed school) were measured continuously. Marital status was measured as a dichotomous variable, where 1 = never married/single and 0 = all other categories (i.e., married, living together as married, separated/divorced, and widowed).

Predisposing Vulnerable:

Predisposing vulnerable factors were measured by past incarceration and victimization history. Past incarceration was measured dichotomously, where 1 = previously served prison sentence and 0 = no previous prison sentence. Victimization history included four dichotomous variables: physical abuse perpetrated with a weapon (1 = Yes, 0 = No), physical abuse perpetrated without a weapon (i.e., being struck or beaten) (1 = Yes, 0 = No), emotional abuse (1 = Yes, 0 = No), and invalidated violent abuse claims (i.e., any violent acts perpetrated against the participant that were not believed to be true by others) (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Enabling Factors

Enabling Traditional:

Enabling traditional factors of substance abuse treatment utilization were measured by the accessibility to local health service facilities, availability of substance abuse treatment facilities, absence of insurance coverage as barrier to treatment, and social support. Participants were asked about the volume of local health care services in the area, with response options ranging from 0, “not available at all,” to 10, “extremely available.” Participants were asked to respond to a more specific statement about the availability of substance abuse treatment with response options included 0 = none, 1 = a few, and 2 = several or a lot. For the purposes of the analysis, dummy codes were created for the availability of substance abuse treatment variable such that “0 = none” was used as the reference category.

Absence of insurance coverage as a potential barrier to treatment was measured dichotomously (1 = No insurance coverage is a barrier, 0 = No insurance coverage is not a barrier). Social support was measured using the General Social Support Index (GSSI), which is a summative subscale of the GAIN assessment tool (Dennis, 2010). This measure assesses a range of environmental and interpersonal support, such as housing, parenting, and getting along with others among other indicators of support. The social support scale is comprised of nine items with each item response coded dichotomously (1 = Yes, 0 = No) to indicate the availability of support in this area (with scores on the overall index ranging from 0–9). Higher scores on the social support scale reflect greater occurrence of support. Previous research has found that internal consistency and validity of the GSSI is good (Cronbach’s alpha = .70 to .80) (Dennis, 2010).

Enabling Vulnerable:

Enabling vulnerable factors of substance abuse treatment utilization included mandated substance abuse treatment, transportation means as barrier to treatment, and distance to nearest treatment facilities as barrier to care. Perceived legal pressure to utilized substance abuse treatment, which was measured by asking the participant whether she endorsed the statement “You could be sent to jail or prison if you are not in treatment.” Response options included 0 = disagree and 1 = agree. Transportation means (i.e., a method to transport to facilities) and distance to nearest substance abuse treatment facilities as a barrier to seek care were both measured dichotomously (1 = Barrier present; 0 = No barrier present).

Need Factors

Need Traditional:

Ever having a lifetime mental health diagnoses and participant readiness for change represented the Traditional Need factors. Participant’s history of mental health diagnoses was measured dichotomously, such that 1 = Yes, received mental health diagnosis and 0 = No, did not receive mental health diagnosis. Participant readiness for change was assessed using the SOCRATES 8D 19-item scale to operationalize intrinsic readiness for change regarding the utilization of substance abuse treatment. The questionnaire has five response categories ranging from 1, “Strongly Disagree,” to 5, “Strongly Agree.”

The SOCRATES consists of three subscales: Recognition, Ambivalence, and Taking Steps. Higher scores on the subscales indicate a higher level of motivation and readiness for treatment. The possible ranges for each scale are as follows: Recognition (seven items) 7–35; Ambivalence (four items) 4–20; and Taking Steps (eight items) 8–40. The range for the total score is 19 to 95. High scores on Recognition indicate that the subject acknowledges having a problem related to drugs or alcohol. High scores on Ambivalence indicate uncertainty as to whether one’s substance abuse is problematic. High scores on Taking Steps indicate one is already acting to reduce his or her substance abuse. For interpretation of SOCRATES scores, Miller and Tonigan (1996) provide a table of decile rankings based on a sample of 1,672 men and women presenting for alcohol treatment in Project MATCH. Scale reliability for the social support scale and each SOCRATES subscale were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha measure for internal consistency. For this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the social support scale was 0.88. The Cronbach’s alpha for the SOCRATES subscales Recognition, Ambivalence, and Taking Steps scale were 0.76, 0.59, and 0.91 respectively.

Need Vulnerable:

Vulnerable Need factors was operationalized by using two health variables: lifetime IDU and lifetime testing for either HIV or Hepatitis C. Both health factors were measured dichotomously (1 = Yes; 0 = No).

ANALYSES

A series of descriptive and bivariate analyses were generated to profile the predisposing traditional and vulnerable factors, enabling traditional and vulnerable factors, and need traditional and vulnerable factors. Descriptive analyses were presented using simple frequencies and percentages. A series of bivariate analyses using binary logistic models were performed as a preliminary step for selecting significant independent variables for the models. The first multivariate model included only the significant Traditional domain variables, and the second model added in the significant Vulnerable domain variables. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 23 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and multicollinearity was not a concern based on the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) below 2.0.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the data on the demographic characteristics of the study participants, as well as data on each traditional and vulnerable domain variables. The sample was predominately Caucasian (99%, n=396) and had an average age of about 32-years-old (SD=8.24). Regarding marital status for the sample, 36.8% reported single or never having been married. Eighty-four percent (n=336) of the sample reported having no prior incarceration history. Much of the sample had a lifetime history of injection drug use (75.5%, n=302).

Table 1.

Summary of Sample Characteristics and Bivariate Screenings for Traditional Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors (N=400)

| Mean (SD)%(N) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Predisposing Factors | ||

| Age | 32.81 (8.24) | 18–61 |

| Education (years completed) | 11.1 (2.28) | 0–19 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| % Caucasian | 99% (396) | |

| Marital status | ||

| % Never married/single | 36.8% (126) | |

| Traditional Enabling Factors | ||

| Social Support Scale | 2.27 (2.65) | 0–9 |

| % Endorse insurance as barrier to tx | 57% (228) | |

| Number of health care facilities | 6.85 (2.58) | 1–10 |

| Availability of tx facilities | ||

| None | 47.5% (181) | |

| A few | 43% (164) | |

| Several/a lot | 9.4% (36) | |

| Traditional Need Factors | ||

| Participant Readiness for Change | ||

| Recognition Scale | 29.73 (4.38) | 14–35 |

| Ambivalence Scale | 15.49 (3.16) | 7–20 |

| Taking Steps Scale | 32.70 (5.96) | 10–40 |

| % Ever received mental health diagnosis | 54% (216) | |

| Vulnerable Predisposing Factors | ||

| No prior incarceration history | 84% (336) | |

| Physical abuse with weapon | 47% (188) | |

| Physical abuse without weapon | 64.5% (258) | |

| Emotional abuse | 73.3% (293) | |

| Violent abuse claims invalidated | 33.5% (134) | |

| Vulnerable Enabling Factors | ||

| Legal pressure to seek tx | ||

| Agree | 48.3% (193) | |

| Disagree | 43.5% (174) | |

| % Endorse transport as barrier to tx | 44.8% (179) | |

| % Endorse distance as barrier to tx | 31.5% (126) | |

| Vulnerable Need Factors | ||

| % Ever inject drugs | 75.5% (302) | |

| % Ever screened for HIV/HEP C | 63.8% (252) |

Note: tx = treatment; Number of health care facilities unit of analysis was a scale measure rather than an actual number of facilities; Bivariate comparisons for availability of tx facilities were conducted in reference to the “none” condition (1=A few, 0=None; 1=Several/a lot, 0=None)

Bivariate Analyses

Each potential explanatory variable was independently included in a binary logistic model with substance abuse treatment utilization as the dependent variable. The results indicated that the participants with a lifetime history of injection drug use (OR=2.71, CI=1.67–4.39), greater occurrence of social support (OR=1.11, CI=1.03–1.19), means of transportation to health care facility as a barrier (OR=1.50, CI=1.01–2.23), greater Recognition within the Readiness for Change scores (OR=1.09, CI=1.04–1.15), a few available substance abuse treatment facilities (as compared to no available facilities) (OR=1.74, CI=1.15–2.61), history of emotional abuse (OR=1.61, 1.03–2.52), and invalidated violent abuse claims (OR=.591, CI=.038-.093) independently contributed to the model and increased the odds of substance abuse treatment utilization. The independent variables that significantly correlated with substance abuse treatment utilization were included in the final multivariate models.

Multivariate Analyses

Model 1 included the significant traditional domain variables at the bivariate level: social support scores, Recognition within the Readiness for Change scores, and availability of a few substance abuse treatment facilities as compared to none. As seen in Table 2, the results of the traditional domain logistic model were statistically significant, χ²(3, 381)=21.04, p<.001, and the Nagelkerke R2 statistic indicated that 7.2% of the variance was explained by the equation (Cox & Snell R2 indicated 5.4% of variance explained). The variable with the strongest relation to treatment utilization was the availability of a few substance abuse treatment facilities (OR=1.68, CI=1.11–2.55). Participant’s Recognition score was also a significant correlate of treatment utilization for rural drug-using women in Appalachian (OR=1.08, CI=1.02–1.13).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of substance abuse treatment utilization by traditional predictor variables (n=381)

| Odds Ratio | CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Few substance abuse tx facilities | 1.68* | 1.11–2.55 |

| Recognition Scale | 1.08* | 1.02–1.13 |

| Social Support Scale |

1.08 |

.99–1.17 |

| Model χ2 | 21.04* | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.054 |

Note: tx = treatment; Few substance abuse tx facilities (1=Yes, 0=No)

p<.05

Model 2, comprised of traditional and vulnerable factors, was statistically significant χ²(7, 307)=36.85, p<.001 (see Table 3). Findings revealed an increase in the overall accuracy for correctly classifying cases from 51.8% to 64.2% (69.2% for participants who had previously sought substance abuse treatment and 58.8% for those who had never sought treatment). The R2 estimates showed that the model explained between 11.3% (Cox & Snell R2) to 15.1% (Nagelkerke R-Square) of the variance in participating in a substance abuse treatment program.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of substance abuse treatment utilization by traditional and vulnerable predictor variables (n=307)

| Odds Ratio | CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever inject drugs | 2.77* | 1.51–5.07 |

| Few substance abuse tx facilities | 2.03* | 1.24–3.33 |

| Invalidated violent abuse claims | 2.12* | 1.27–3.52 |

| Recognition Scale | 1.07* | 1.01–1.14 |

| Transport as barrier to tx | 1.62 | .98–2.69 |

| Emotional abuse | 1.36 | .57–3.24 |

| Social Support Scale |

1.01 |

.92–1.11 |

| Model χ2 | 36.85* | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.113 |

Note: tx = treatment; Ever inject drugs (1=Yes, 0=No); Few substance abuse tx facilities (1=Yes, 0=No); Invalidated violent abuse claims (1=Yes, 0=No); Transport as barrier to tx (1=Yes, 0=No); Emotional abuse (1=Yes, 0=No)

p<.05

As presented in Table 3 with the adjusted odds ratios, history of IDU (p=.001), recognition of drug problem (p=.028), availability of a few health care facilities providing drug treatment (p=.005), and history of invalidated violent abuse claims (p=.004) were the only independent variables that contributed significantly to substance abuse treatment utilization. The likelihood of having previously utilized substance abuse treatment was 2.77 times greater for participants who had a lifetime history of injection drug abuse. The odds of previous substance abuse treatment were 1.1 times greater for each increment increase on Recognition scores. Participants who had a few substance abuse treatment programs available nearby were 2.03 times more likely to have utilized treatment as compared to participants who had no local treatment programs available. Lastly, participants who had an invalidated claim of violence against them were 2.12 times more likely to utilize substance abuse treatment.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify predictors of substance abuse treatment utilization by applying the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations to rural Appalachian women. This study addresses a significant gap in the literature on the availability and utilization of drug treatment services in rural areas, as established by previous studies (Browne et al., 2016; Tsogia, Copello, & Orford, 2001) while also examining distinct types of health service utilization (i.e., substance abuse treatment) among vulnerable populations (Oser et al., 2016). The significant findings in this study build upon past research that have examined drug treatment utilization, especially in literature addressing rural substance abusers, and the theoretically-guided characteristics of rural substance abuser’s utilization of treatment (Edmond, Aletraris, Roman, 2015; Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016; Schoenberger et al., 2006; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015; Staton-Tindall et al., 2007; & Varga & Surratt, 2014).

By using Gelberg and colleagues’ (2000) Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations as theoretical guide for our analyses, this study identified significant social, environmental, and individual predictors of substance abuse treatment utilization. To note, the addition of the Vulnerable variables in Table 3 significantly improved the overall model fit. Thus, if researchers and practitioners fail account for the variables in the vulnerable domains – there is a risk of missing important information that explains why vulnerable groups do not utilize substance abuse treatment.

About half of the sample had utilized treatment over the course of their lifetime. Among the predisposing factors, only one Predisposing vulnerable factor – invalidated violence abuse claims – emerged as a significant correlate of treatment utilization, such that participants who had a history of invalidated violent abuse claims were just over twice as likely to have sought treatment. It may be that the experience of invalidation across a host of occurrences and types of victimization could encourage the women in this sample to seek substance abuse treatment as a means of seeking emotional support. The attritional effect of invalidation with respect to victimization could deny ownership of one’s personal experiences and perceptions; thus, a person’s reaction to this additional stress may increase her substance abuse. On the contrary, this finding might be less indicative of an increased severity of substance abuse, but rather an act of outreach for increased support and/or options to mitigate their victimization.

Chang and colleagues (2010) further this point in their qualitative study examining women who experience IPV and their motivations for seeking change. That is, women reported that interactions with healthcare providers – physicians, nurses, social workers, and behavioral health counselors – positively changed how they viewed themselves and other elements (i.e., the violent acts and their partner) of their victimization experiences (Chang et al., 2010). In other words, this finding may imply that the women in this sample had substance abuse issues they wished to treat, and their invalidated victimization put them at a greater likelihood to utilize treatment because they also sought a sense of validation from a concerned and/or supportive health care professional.

To account for this finding within the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) it is important to refer to the contextual definition of a Predisposing vulnerable factor. For instance, one Predisposing factor that is unique to vulnerable populations is a preexisting condition of victimization, which influences the individual to utilize treatment (Gelberg et al., 2000). This victimization – especially if the victimization is invalidated – may be the primary impetus for vulnerable women to seek treatment, and the general support that is supplied by interacting with an empathetic health care professional. Therefore, it is plausible to note that for vulnerable women who have had invalidated victimization claims may enter substance abuse treatment for general support, and that treating their substance abuse is a secondary or tertiary treatment goal.

This study did identify several statistically significant Need factor correlates of drug treatment utilization among our sample. First, the Need traditional factor that was found to be a statistically significant predictor of substance abuse treatment utilization related to participants’ recognition of a potential problem. The findings in this study are like other treatment-based studies examining problem recognition (Haughwout et al., 2016; Miller & Tonigan, 1996). A possible observed effect of this finding may be that those who recognized they had a substance abuse problem were more likely to utilize treatment; yet, the increased likelihood was moderate, which perhaps suggests other unmeasured motivational factors impacted this finding. It is possible that other unmeasured factors could also account for their utilization of treatment. For instance, participants’ subjective factors such as weighing of pros and cons and self-efficacy that may have shaped their utilization of treatment were not directly queried in this study, and these factors could potentially impact this finding.

The most robust correlate of treatment utilization among Need vulnerable factors was IDU, which by far exceeded the strength of explanatory power compared to other theorized Need vulnerable factors. This finding may be best interpreted by examining the unique complications associated with IDU, as well as theoretical considerations based on the model tested in this study. For instance, is IDU viewed by most as a severe type of drug use (Mathers et al., 2013). Also, it may be that individuals are more likely to seek treatment because IDU can leave visual evidence of drug use (e.g., track marks), and the potential co-morbid health risks involved with IDU (e.g., HCV or HIV) that may intensify the perceived need for treatment. Within the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations, Need factors have been found to increase the likelihood that an individual will utilize health services. In addition, Need vulnerable factors presuppose that certain health behaviors and health risks have a higher probability of producing negative effects on vulnerable populations. In past literature, IDU and the co-occurring negative health risks have been found impact vulnerable groups at a greater proportion when compared to non-vulnerable groups (Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016; Varga & Surratt, 2014). Therefore, our findings are consistent with Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations characterization of Need factors, and suggest that substance abuse treatment utilization among rural Appalachian women may be contingent on the severity of the drug use (i.e., IDU).

Moreover, this finding could also be indicative of cultural norms relative to the rural southeastern region of the United States. For instance, Browne et al. (2016) qualitatively examined barriers and facilitators of substance use treatment in the rural southeast U.S. by using a sample that was 80% female. In general, they found that stigma and lack of access to various treatment services were identified as barriers to treatment. Therefore, a negative stigma of substance use may play a meaningful role in how our sample perceives their need for treatment services, so it is conceivable that only the most severe type of drug use (i.e., IDU) is addressed for drug treatment services in certain rural areas.

If this is the case, then vital intervention points aimed at drug replacement and maintenance therapy (e.g., methadone and/or buprenorphine) are potentially missed, which may prevent the onset of IDU altogether. Future studies should investigate the quantity and quality of such reduction interventions available, or participated in by rural Appalachian women prior to their engagement with IDU. Another potential explanation for this finding is the criminality of drug use. Meaning, rural substance using women might bypass treatment due to a perceived fear of criminal punishment for their drug use, but the fear of criminal punishment may subside as the severity of their drug use increases, and their health concerns intensify; thus, increasing the likelihood they will utilize treatment. Future research should qualitatively investigate the extent to which rural women may bypass treatment due to a perceived fear of criminal prosecution, and how community-based educational resources might mitigate these concerns.

Based on the application of the theoretical model in this study, traditional and vulnerable Enabling factors played the most significant role in predicting lifetime substance use treatment utilization, and that is consistent with other studies using different vulnerable groups (Gelberg et al., 2000; Oser et al., 2016; & Varga & Surratt, 2014;). The participants’ perceptions of the availability of treatment facilities was a statistically significant predictor of utilizing substance use treatment. Specifically, the relationship between the variables suggests that having fewer treatment facilities available significantly reduces the likelihood that these individuals would utilize treatment. This finding is consistent with previous work identifying the need to increase the availability of rural treatment centers – especially centers which are specific to the complex needs of substance abuse (e.g., rather than emergency room or general care facility) (Browne et al., 2016; Harp, Oser, & Perry, 2014).

In addition, this finding may reflect regional specific conceptualizations of not only what care facilities are available, but perhaps also of the perceived utility of these health care facilities. In other words, participants may or may not be aware that certain facilities offer substance use treatment, or it may also be that the cultural norms of addressing substance use issues are addressed outside of health care facilities (e.g., family-kin networks, or religious affiliated support centers) (Snell-Rood, Staton-Tindall, & Victor, 2016; Warner & Leukefeld, 2001). One interpretation that speaks to this finding is that health literacy in rural areas has been found to be low, and this might account for the perception that substance abuse treatment services are either lacking, and/or are not needed for the treatment of substance use disorders among this sample (Denham, Meyer, Toborg, & Mande, 2004).

LIMITATIONS

This study has a few noteworthy limitations. The generalizability of this study applies primarily to rural women in the southeastern U.S. since data collection was limited to a single state, and further research is needed before the results in this study are applied to other population samples. Another limitation includes the use of secondary data and its application to the theoretical model. Due to the nature of secondary data, our ability to operationalize variables to match those found in the original theoretical model was limited as variables in the present dataset were pre-determined before this study. To that end, future studies might have greater predictive power if they collect primary data with the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations in mind. Third, the cross-sectional data does not allow for causal explanations. Future research should use longitudinal data to predict factors associated with treatment utilization.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Regarding the theoretical model, this study confirms that vulnerable domains related to health services utilization warrant unique considerations (i.e., invalidation of victimization claims, IDU, and availability of treatment resources) compared to non-vulnerable domain. To that end, public health officials, clinical social workers, and policymakers should consider the novel challenges and susceptibilities to health risks of vulnerable groups. For example, policy measures should be designed to expand the availability of substance abuse treatment services and harm reduction services for injection drug-users in rural areas, and acute treatment centers aimed at mitigating the medical harm caused by substance use. At the practice-level, intervention and screening protocol for violence-related problems should be culturally-informed (e.g., vulnerable groups) and routine in the substance abuse treatment scheme, especially for vulnerable populations, as the results in this study indicate. In conclusion, these proposed policy and practice efforts may be most effective if they are communicated to rural community leaders, so that regular community forums (e.g., town halls) can be held for all members of the community with the intention to educate and formalize community-tailored treatment plans from the policy-level down to the citizen-level.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides an important look at the health and health behaviors of vulnerable rural women and their utilization of substance use treatment in what is considered an economically distressed region (ARC, 2016). The study findings depict the adverse environmental and individual conditions that may make utilizing substance use treatment more challenging; however, the results in this study also suggest a degree of resilience among this sample to utilize substance use treatment despite the mentioned challenges.

Contributor Information

GRANT VICTOR, College of Social Work, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

ATHENA KHEIBARI, College of Social Work, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

MICHELE STATON, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

CARRIE OSER, College of Sociology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

References

- Abbasi J (2016). Opioid Epidemic in Appalachia Receives USDA Telemedicine Funding. Jama, 316(8), 808–808. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R (1968). A behavioral model of families’ use of health services Research Series, No. 25, Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin M (2016). Framing Appalachia: A New Drug in an Old Story. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 22(1), 136–150. doi: 10.5406/jappastud.22.1.0136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley K, Wish ED, Fitzelle DB, O’Grady K, & Arria AM (2003). Distance traveled to outpatient drug treatment and client retention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25(4), 279–285. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders TF, Booth BM, Stewart KE, Cheney AM, & Curran GM (2015). Rural/urban residence, access, and perceived need for treatment among African American cocaine users. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(1), 98–107. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne T, Priester MA, Clone S, Iachini A, DeHart D, & Hock R (2016). Barriers and facilitators to substance use treatment in the rural south: A qualitative study. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(1), 102–109. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Columbia University; National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (2000). The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University Annual Report National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Han X, Curran GM, & Booth BM (2016). Associations Between Religiosity, Perceived Social Support, and Stimulant Use in an Untreated Rural Sample in the USA. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(7), 823. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1155611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, & Smith JC (2010). US Census Bureau, current population reports, P60–238. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Meyer MG, Toborg MA, & Mande MJ (2004). Providing health education to Appalachia populations. Holistic Nursing Practice, 18(6), 293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML (2010). Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): A standardized biopsychosocial assessment tool. Chestnut Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Edmond MB, Aletraris L, & Roman PM (2015). Rural substance use treatment centers in the United States: An assessment of treatment quality by location. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 41(5), 449–457. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1059842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Burgess JF Jr, Bosworth HB, Booth BM, & Kaboli PJ (2011). A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(2), 639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney J, & Booth BM (2002). Access to substance abuse services in rural areas In Alcoholism (pp. 177–197). Springer, Boston, MA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaskerud JH, & Winslow BJ (1998). Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nursing Research, 47(2), 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm L, & Hutchison L (2003). Public health rural health priorities in America: where you stand depends on where you sit. The Journal of Rural Health, 19(3), 209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM, & Leake BD (2000). The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harp KL, Oser CB, & Perry B (2014). But then what? A longitudinal analysis of child custody issues and how they impact future substance-using behavior among African-American mothers. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 140, e79–e80. [Google Scholar]

- Haughwout SP, Harford TC, Castle IP, & Grant BF (2016). Treatment utilization among adolescent substance users: Findings from the 2002 to 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(8), 1717–1727. doi: 10.1111/acer.13137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Knudsen HK, Lofwall M, Stoops WW, Walsh SL, & Kral AH (2011). Individual and network factors associated with non-fatal overdose among rural Appalachian drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1–2), 107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Walker R, & Leukefeld CG (2007). Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87(1), 98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Talbert JC, Walker R, Leedham C, & Leukefeld CG (2006). Trends in controlled-release oxycodone (oxycontin®) prescribing among medicaid recipients in Kentucky, 1998–2002. The Journal of Rural Health, 22(3), 276–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, & Shannon L (2012). Barriers to receiving substance abuse treatment among rural pregnant women in Kentucky. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(9), 1762–1770. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0923-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, & Glaze LE (2006). Highlights Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Jeong JJ, Pepler DJ, Motz M, DeMarchi G, & Espinet S (2015). Readiness for Treatment: Does It Matter for Women with Substance Use Problems Who Are Parenting? Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 15(4), 394–417. doi: 10.1080/1533256X.2015.1091002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, & Galea S (2014). Understanding the rural-urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e52–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP, Arfken CL, Swartz JA, & Koch AL (2006). Treatment at the front end of the criminal justice continuum: the association between arrest and admission into specialty substance abuse treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 1, 20. doi 10.1186/1747-597X-1-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Logan TK, Farabee D, & Clayton R (2002). Drug use and AIDS: Estimating injection prevalence in a rural state. Substance Use & Misuse, 37(5–7), 767–782. doi: 10.1081/JA-120004282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Logan TK, Martin SS, Purvis RT, & Farabee D (1998). A health services use framework for drug-abusing offenders. American Behavioral Scientist, 41(8), 1123–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, & Bell R (2009). Action on health disparities in the United States: commission on social determinants of health. JAMA, 301(11), 1169–1171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, & Hickman M (2013). Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91(2), 102. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum ML (2016). The Ongoing Opioid Prescription Epidemic: Historical Context. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis: Sage university series on quantitative applications in the social sciences.

- Metsch LR, & McCoy CB (1999). Drug treatment experiences: Rural and urban comparisons. Substance Use & Misuse, 34(4–5), 763–784. doi: 10.3109/10826089909037242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Tonigan JS (1996). Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10(2), 81. [Google Scholar]

- Oser CB, Bunting AM, Pullen E, & Stevens-Watkins D (2016). African American Female Offender’s Use of Alternative and Traditional Health Services After Re-Entry: Examining the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(2), 120–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oser CB, Leukefeld CG, Staton Tindall M, Garrity TF, Carlson RG, Falck R, & ... Booth BM (2011). Rural drug users: Factors associated with substance abuse treatment utilization. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(4), 567–586. doi: 10.1177/0306624X10366012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen E, & Oser C (2014). Barriers to substance abuse treatment in rural and urban communities: Counselor perspectives. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(7), 891–901. 10.3109/10826084.2014.891615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, & Bucher Bartelson B (2012). Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse? Pain Medicine, 13(3), 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, & Rice E (2014). Prescription drug misuse among homeless youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 138, 229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneberger ML, Leukefeld CG, Hiller ML, & Godlaski T (2006). Substance abuse among rural and very rural drug users at treatment entry. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32(1), 87–110. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DL, Coolidge FL, Mincic MS, & O’riley A (2005). Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: A cross-sectional study. Aging & Mental Health, 9(4), 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon LM, Havens JR, Oser C, Crosby R, & Leukefeld C (2010). Examining gender differences in substance use andage of first use among rural Appalachian drug users in Kentucky. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(2), 98–104. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon LM, Havens JR, & Hays L (2010). Examining differences in substance use among rural and urban pregnant women. The American Journal on Addictions, 19(6), 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon LM, Havens JR, Mateyoke-Scrivner A, & Walker R (2009). Contextual differences in substance use for rural Appalachian treatment-seeking women. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35(2), 59–62. doi: 10.1080/00952990802441394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small J, Curran GM, & Booth B (2010). Barriers and facilitators for alcohol treatment for women: Are there more or less for rural women? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell-Rood C, Staton-Tindall M, & Victor G (2016). Incarcerated women’s relationship-based strategies to avoid drug use after community re-entry. Women & Health, 56(7), 843–858. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2015.1118732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Webster JM, Oser CB, Havens JR, & Leukefeld CG (2015a). Drug use, Hepatitis C, and service availability: perspectives of incarcerated rural women. Social Work in Public Health, 30(4), 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Harp KH, Minieri A, Oser C, Webster JM, Havens J, & Leukefeld C (2015b). An exploratory study of mental health and HIV risk behavior among drug-using rural women in jail. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(1), 45–54. doi: 10.1037/prj0000107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Duvall JL, Leukefeld C, & Oser CB (2007). Health, mental health, substance use, and service utilization among rural and urban incarcerated women. Women’s Health Issues, 17(4), 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Leukefeld C, & Logan TK (2001). Health services utilization and victimization among incarcerated female substance users. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(6–7), 701–716. doi: 10.1081/JA-100104086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruya C, & Hser YI (2010). Turning points in the life course: current findings and future directions in drug use research. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 3(3), 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsogia Alex Copello, Orford Jim, D. (2001). Entering treatment for substance misuse: A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 10(5), 481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Varga LM, & Surratt HL (2014). Predicting health care utilization in marginalized populations: Black, female, street-based sex workers. Women’s Health Issues, 24(3), e335–e343. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD, & Leukefeld CG (2001). Rural-urban differences in substance use and treatment utilization among prisoners. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 27(2), 265–280. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100103709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JM, Rosen PJ, Krietemeyer J, Mateyoke-Scrivner A, Staton-Tindall M, & Leukefeld C (2006). Gender, mental health, and treatment motivation in a drug court setting. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 38(4), 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JM, Leukefeld CG, Tindall MS, Hiller ML, Garrity TF, & Narevic E (2005). Lifetime Health Services Use by Male Drug-Abusing Offenders. The Prison Journal, 85(1), 50–64. doi: 10.1177/0032885504274290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Craddock SG, & Hubbard RL (1998). How are women who enter substance abuse treatment different than men? A gender comparison from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Drugs & Society, 13(1–2), 97–115. doi: 10.1300/J023v13n01.06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J, & Boedicker AE (2000). Course, severity and treatment of substance abuse among women versus men. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 26(4), 523–535. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100101893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Gupta A, Al-Ghabeish M, Calderon SN, & Khan MA (2016). Risk based in vitro performance assessment of extended release abuse deterrent formulations. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 500(1–2), 255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Havens JR, & Leukefeld CG (2010). Route of administration for illicit prescription opioids: a comparison of rural and urban drug users. Harm Reduction Journal, 7(1), 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, & Havens JR (2012). Transition from first illicit drug use to first injection drug use among rural Appalachian drug users: A cross‐sectional comparison and retrospective survival analysis. Addiction, 107(3), 587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Infante A, Meit M, English N, Dunn M, & Bowers K (2008). An analysis of mental health and substance abuse disparities & access to treatment services in the Appalachian region. Final report. Washington: Appalachian Regional Commission. [Google Scholar]