Abstract

Objective:

Thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) may result in toxicities that are associated with performance declines and poor quality of life (QOL) for patients and their family caregivers. The purpose of this randomized controlled trial was to establish feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a dyadic Yoga (DY) intervention as a supportive care strategy.

Methods:

Patients with stage I-III non-small cell lung or esophageal cancer undergoing TRT and their caregivers (N=26 dyads) were randomized to a 15-session DY or a waitlist control (WLC) group. Prior to TRT and randomization, both groups completed measures of QOL (SF-36) and depressive symptoms (CES-D). Patients also completed the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Dyads were reassessed on the last day of TRT and three months later.

Results:

A priori feasibility criteria were met regarding consent (68%), adherence (80%) and retention (81%) rates. Controlling for relevant covariates, multilevel modeling analyses revealed significant clinical improvements for patients in the DY group compared to the WLC group for the 6MWT (means: DY=473m vs. WLC=397m, d=1.19) and SF-36 physical function (means: DY=38.77 vs. WLC=30.88; d=.66) and social function (means: DY=45.24 vs. WLC=39.09; d=.44) across the follow-up period. Caregivers in the DY group reported marginally clinically significant improvements in SF-36 vitality (means: DY=53.05 vs. WLC=48.84; d=.39) and role performance (means: DY=52.78 vs. WLC=48.59; d=.51) relative to those in the WLC group.

Conclusions:

This novel supportive care program appears to be feasible and beneficial for patients undergoing TRT and their caregivers. A larger efficacy trial with a more stringent control group is warranted.

Keywords: Thoracic radiotherapy, yoga, dyadic intervention, physical function, quality of life, family caregivers, cancer, oncology

BACKGROUND

Thoracic radiotherapy (TRT), particularly when delivered concurrently with chemotherapy, may result in acute and late toxicities (e.g., dyspnea, reduced lung function).1–4 Chemoradiation is often the definitive treatment for patients with thoracic malignancies (e.g., lung and esophageal cancers) because they tend to be diagnosed with unresectable, locally advanced or even metastatic disease.5 Due to the adverse effects of aggressive multimodal cancer treatment, a generally poor prognosis, and common comorbidities, patients with thoracic cancers are at high risk of experiencing physical function declines, physical and psychological symptoms, and overall poor quality of life (QOL).3,4,6 Consequently, patients have a high need for tangible care and emotional support from their families.7 Caregiving is taxing, however, and family caregivers often report feeling helpless and overwhelmed and having low caregiving efficacy.8,9 Given the high rates of distress in both cancer patients and their family caregivers, and the interdependent nature of distress in families coping with cancer, a dyadic approach to supportive care may be advantageous over traditional, patient-oriented interventions.10–12 The psychosocial literature includes reports of a handful of dyadic randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including those with lung and esophageal cancer patients, with two of these trials providing evidence of preliminary efficacy in improved psychological distress or relationship outcomes.13,14 Of note, previously reported dyadic psychosocial interventions have not targeted physical function as a study outcome.

Considering the need to address physical decline and the mixed evidence regarding improved symptoms and QOL in thoracic cancer patients and their caregivers, a dyadic yoga (DY) intervention that integrates gentle movements with breathing exercises and relaxation techniques focusing on the needs of the patient-caregiver dyad may be a promising supportive care strategy. Although researchers have extensively studied yoga in women with breast cancer, little is known regarding the feasibility of implementing an RCT of yoga in patients undergoing TRT.15,16 In our formative research, we developed a DY intervention to improve QOL during and after TRT.17

Building on this previous study, we sought to examine the feasibility of implementing an RCT of this intervention and expand our procedures to include the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), an objective, clinically relevant measure of patients’ physical function found to predict survival in patients with lung cancer.18 Based on previous dyadic psychosocial RCTs, we hypothesized that at least 60% of eligible dyads would consent to participate, participants randomized to the DY group would attend at least 75% of the intervention sessions, and 60% of the dyads would be retained at the 3-month follow-up assessment.13,14,19 Additionally, we sought to establish the preliminary efficacy for the intervention regarding clinically significant improvements in patients’ 6MWT results and patients’ and caregivers’ depressive symptoms and overall QOL relative to those of dyads in a waitlist control (WLC) group at the end of treatment and 3 months later.

METHODS

Participants

Patients with stage I-IIIB non-small cell lung or esophageal cancer undergoing at least 5 weeks of TRT having a consenting family caregiver (e.g., spouse, sibling, adult child) were eligible to participate. Both patients and caregivers had to be at least 18 years old, proficient in English, and able to provide informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were not oriented to time, place, or person; practiced any form of yoga on a regular basis (self-defined) in the year prior to diagnosis; and had a physician-rated Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of greater than 2.

Procedure

Prior to starting the trial, the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board approved all of the procedures. Research staff identified potentially eligible patients in the institution’s electronic medical records, approached patients and caregivers during routine clinic visits, confirmed their study eligibility, and obtained their written informed consent to participate prior to data collection. If a caregiver was not present during a clinic visit, the patient’s permission to contact the caregiver was obtained. Prior to randomization, both patients and caregivers completed paper-pencil survey measures (baseline/T1) and then again on the last day of TRT (T2), and 3 months later (T3). Surveys were returned either in person during a clinic visit or via pre-postage paid return envelops. Patients also completed the 6MWT at T1–T3. Participants were enrolled for a duration of 18–20 weeks. The trial was completed between Nov 2014 and October 2016.

Randomization

Dyads were randomized to either the DY or WLC group through a form of adaptive randomization called minimization ensuring that the groups were balanced on patients’ stage, sex, age, and cancer type (non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) vs esophageal cancer) using a computerized system (Filemaker).20

DY Group

The manualized yoga program was developed in collaboration with Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana. Two certified instructors (International Association of Yoga Therapists; C-IAYT) who had also completed a 200 hours instructor course in Vivekananda yoga implemented the sessions. All sessions were delivered to individual patient-caregiver dyads either in a designated space for behavioral interventions or a family consult room in the radiation treatment area based on participants’ preference. Dyads had to attend all sessions together over the course of patients’ standard TRT (2–3 times per week for a total of 6 weeks; 60 min per session).

The program consisted of four main components: 1) joint loosening with breath synchronization; 2) postures (asanas) including partner-poses followed by relaxation techniques; 3) breath energization (pranayama) with sound resonance; and 4) guided imagery/meditation focusing on dyadic concepts (e.g., love, acceptance).17 Sessions 1–4 focused on gradually introducing the various practices. The remaining sessions (5–15) focused on practicing the components and answering questions pertaining to the techniques and participants’ experiences. Starting with session 1, instructors conveyed the notion that each practice is intended to target the needs of both members of the dyad, with a focus on their interconnectedness. Participants received printed materials and a compact disc containing the program at sessions 1 and 5, respectively, and were encouraged to practice the techniques on their own on the days when they did not meet with their instructor.

To ensure treatment fidelity, all sessions were video-recorded (with the participants’ permission obtained during the informed consent process) and reviewed on an ongoing basis using a fidelity checklist.

WLC Group

The WLC group received the usual care as provided by their health care team and were offered the intervention after they completed the T3 assessment. No additional data were collected.

Measures

Demographic and Medical Factors.

Demographic items (e.g., age, marital status) were included in the baseline questionnaires. Patients’ medical data were extracted from their electronic medical records.

Feasibility Data.

Tracking data regarding consent rates, class attendance, completion of questionnaires, and attrition were kept. Participants in the DY group completed an evaluation of the intervention to assess their satisfaction. The frequency of home yoga practice was assessed weekly with a paper-pencil practice log over the course of TRT. Instructors monitored for adverse events, and participants completed perceived exertion during the yoga session on the 0–10 Borg scale on a weekly basis to ascertain patient safety.21

Patient physical function was assessed using the 6MWT following the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (ATS).22 A research assistant who was blinded to group assignment implemented the tests on a straight, long, and flat hospital corridor. For patients with thoracic malignancies, 42 meters (m) has been identified as the cut-off value for clinically relevant differences.23 Patients were asked to indicate their level of perceived exertion during the task on the 0–10 Borg scale and their shortness of breath on the 0–10 modified Borg Scale.21,24 A 1-point between-group difference has been identified as the minimally clinically important difference.25

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item self-reported instrument focusing on the affective component of depression.26 A score of at least 16 is the cutoff for further psychological evaluation for a depressive disorder.

QOL was assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form survey (SF-36) assessing 8 distinct domains: physical functioning, physical impediments to role functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, emotional impediments to role functioning, and mental health.27 A group difference of 5 points is considered clinically significant.

Statistical Analyses

To examine feasibility, we calculated descriptive statistics of consent, class attendance, assessment completion, and program satisfaction. To establish preliminary efficacy, we used an intent-to-treat analysis when performing multilevel modeling (MLM) using PROC MIXED (SAS, 9.4 version). We used separate analyses for patients and caregivers and controlled for baseline level of the given outcome. Because age, gender, smoking status, and patients’ stage at diagnosis have been associated with outcomes in thoracic cancers,28,29 we included these factors as a priori covariates when examining group means. In the caregiver models, we controlled for age and sex as they were associated with the outcomes at P<.05. We examined each dimension of the SF-36 separately to identify which QOL domain may serve as a primary outcome in the future efficacy trial. Because the current study is a pilot trial and not adequately powered, we interpreted least square mean (LSM) differences for the 6MWT and SF-36 domains based on clinical relevance as opposed to inferential significance testing. We also calculated the effect size (Cohen’s d) associated with each between-group comparison interpreting effects as small (d = .2), medium (d = .5) and large (d =.8) and recorded 95% confidence intervals (CI).30 Because too few participants met the CES-D caseness criterion, we did not examine change in caseness to identify clinical relevance. Instead, we examined the between-group effect size to establish preliminary efficacy. We followed-up the MLM analyses with cross-sectional between group tests to examine LSM for time point. We determined sample size based on Whitehead et al’s recommendation of n=30 for a two arm-pilot trial detecting a medium effect size with 90% power and two-sided 5% significance.31 (We consented an additional two dyads because two of the consented patients became ineligible as mentioned below).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Baseline demographic and medical data are listed in Table 1. Briefly, patients mostly were male (62%), White (88%), educated with at least some college credits (69%), elderly (mean=66.7 years, range=33–88), and retired (62%); and had NSCLC (80%), and stage III disease (92%). Caregivers mostly were female (62%), educated with at least some college credits (54%), middle aged (mean age=60 years; range=24–78), fulltime employed (31%); and married (81%) to the patient. CES-D caseness was low for both patients (19%) and caregivers (15%). There were no significant group differences regarding baseline participant characteristics. See supplemental table 1 for baseline dyadic results.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient and Caregiver Characteristics (N=26 Dyads)

| Yoga Group (N=13 Dyads) | Control Group (N=13 Dyads) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patient | Caregiver | Patient | Caregiver |

| Male sex n (%) | ||||

| 8 (62) | 5 (38) | 8 (62) | 3 (17) | |

| Mean age, years ±SD, (range) | 66.15±5.48 (58–76) | 62.01±11.37 (29–75) | 65.54±12.53 (32–87) | 56.9±15.17 (24–78) |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 11 (85) | 11 (85) | 13 (100) | 13 (100) |

| Spousal caregiver | 12 (92) | 10 (77) | ||

| Highest Level of Education, n (%) | ||||

| Some college or higher | 10 (77) | 11 (85) | 10 (77) | 9 (69) |

| Household Income, n (%) | ||||

| 50,000 or more | 12 (92) | 11 (85) | 11 (85) | 9 (69) |

| Employment Status, n (%) | ||||

| Retried | 9 (69) | 7 (54) | 8 (62) | 5 (38) |

| Full-time | 2 (15) | 4 (31) | 3 (23) | 4 (31) |

| Medical leave | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 2 (15) | 1 (8) |

| Part-time/Homemakers | 1 (8) | 3 (23) | ||

| Cancer Type, n (%) | ||||

| Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | 10 (77) | 10 (77) | ||

| Stage at Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| III | 9 (69) | 8 (62) | ||

| Resection, n (%) | ||||

| Yes, | 4 (31) | 3 (23) | ||

| Chemoradiation, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (92) | 12 (92) | ||

| ECOG performance status at recruitment | ||||

| 0 | 3 (23) | 5 (38) | ||

| I | 8 (62) | 7 (54) | ||

| Time since diagnoses, weeks ±SD, (range) | 4.93±2.00 (1–12) | 8.51±8.44 (2–34) | ||

Abbreviations: SD, Standard deviation; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Feasibility Results

Recruitment and Sample Retention.

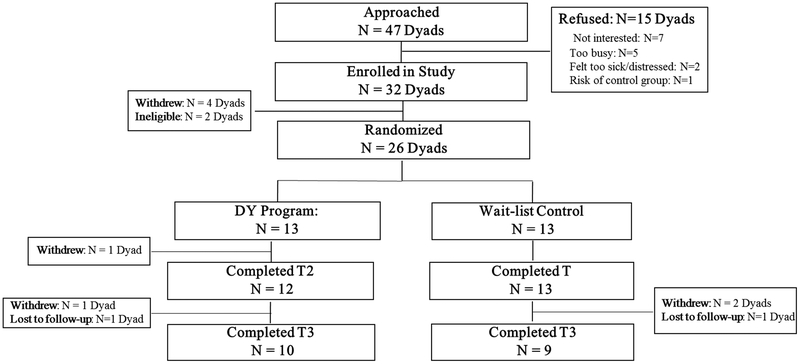

We screened 144 patients, 47 of whom were eligible for study participation. Ineligibility was mainly due to lack of a caregiver or consenting caregiver (n = 73). Of the eligible dyads, 32 (68%) consented. Refusal reasons were lack of interest (n = 7) and time (n = 5), feeling too sick or distressed to participate (n = 2), and not wanting to risk being in the control group (n = 1). Four patients withdrew prior to randomization and 2 became ineligible due to disease progression and discontinuation of treatment prior to randomization so that we randomized 26 of the 32 dyads that had consented. Regarding the questionnaires and 6MWT, 26 dyads completed the T1 assessment, 25 completed the T2 assessment, and 18 (70%) completed the T3 assessment. See Figure 1 for Consort Chart.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram.

Adherence and Acceptability.

Dyads randomized to the DY group attended a mean of 12 sessions (SD=4.0; range: 4–15; 80% of all sessions) and practiced on average 2.17 times (SD=1.63; range: 0–5 times) per week outside of class. All participants in the DY group rated each component of the intervention as either “beneficial” or “very beneficial” and the overall program as “useful” or “very useful”. The majority of patients (90%) in the DY group chose to attend the yoga sessions in the behavioral intervention center. No related adverse events were observed. Participants rated the session as “easy” on the Borg exertion scale (patients: mean= 2.17 SD=0.75, range=1–3; caregivers: mean = 2.57, SD=0.98, range=1–4).

Preliminary Efficacy Results

Patient Physical Function.

Controlling for the above mentioned covariates, MLM analyses for the 6MWT revealed a clinically significant group main effect (LSM: DY=473m, 95% CI [408, 538] vs WLC=397m, 95% CI [317, 478];, d=1.19;) so that patients in the DY group performed significantly better compared to those in the WLC group. Clinical improvements were observed at T2 (LSM: DY=480m, 95% CI [401, 560] vs WLC=402 m, 95% CI [320, 485]; d=1.07) and T3 (LSM: DY=493m, 95% CI [370, 565] vs WLC=374m, 95% CI [315, 509]; d=.94). Patients in the DY group reported clinically significantly lower levels of dyspnea (DY mean= 1.67, 95% CI [1.08, 2.39] vs WLC mean=2.69, 95% CI [1.96, 3.46]; d=0.83) and exertion (DY mean=1.47; 95% CI [0.58, 2.36] vs. WLC mean =3.69, 95% CI [2.70, 4.69]; d=.80) compared to those in the WLC group during the 6MWT.

Depressive Symptoms.

MLM analyses revealed slightly better depressive symptoms for patients in the DY group compared to those in the WLG group (LSM: DY=7.80, 95% CI [4.25, 11.71] vs. WLC=9.84, 95% CI [4.22, 15.24]; d=.26). Cross-sectional analyses found a medium effect size at T2 (DY mean=7.47, 95% CI [0.94, 13.99]; vs WLC mean =10.44, 95% CI [0.87, 13.31]; d=.50) and at T3 (DY mean=8.29, 95% CI [3.22, 13.38] vs. WLC mean =11.29, 95% CI [3.21, 19.36]; d=.39). For caregivers, we found no evidence that the intervention reduced their depressive symptoms (LSM: DY=6.98, 95% CI [4.26, 9.70] vs. WLC=5.72m, 95% CI [2.80, 8.64]; d=.12).

QOL.

MLM analyses revealed a clinically significant group main effects for physical function (LSM: DY=38.77, 95% CI [30.04, 47.94] vs. WLC=30.88, 95% CI [19.44, 42.31]; d=.66) and social function (LSM: DY=45.24, 95% CI [32.42, 58.07] vs. WLC=39.09, 95% CI [19.72, 58,45]; d=.44) so that patients in the DY group reported better QOL compared to those in the WLC group. Cross-sectional follow-up analyses revealed clinically significant differences at T2 for role performance (LSM: DY=40.99, 95% CI [31.06, 50.92] vs WLC=35.23, 95% CI [22.23, 48.22]; d=.50) and mental health (LSM: DY=56.97, 95% CI [45.64, 68.30] vs WLC=50.07, 95% CI [35.29, 64.84]; d=.94) in the expected direction. At T3, although the DY group reported improved vitality (LSM: DY=44.56, 95% CI [27.53, 61.59] vs. WLC=37.97, 95% CI [10.01, 65.93]; d=.60), they reported worse general health compared to the WLC group (LSM: DY=44.08, 95% CI [31.35, 56.81] vs WLC=49.41, 95% CI [24.37, 74.46]; d=.42). According to the results of the MLM analyses, caregivers in the DY group did not show significant improvements in any of the QOL domains. Cross-sectional follow-up analyses revealed that caregivers in the DY group reported marginally clinically significant improvements in role performance (LSM: DY=52.78, 95% CI [48.82, 56.74] vs WLC=48.59, 95% CI [43.81, 53.37]; d=.51) and vitality (LSM: DY=53.05, 95% CI [35.29, 64.84] vs WLC=48.84, 95% CI [43.81, 53.37]; d=.39) at T2 and social function (DY LSM=50.55, 95% CI [45.83, 55.27] vs WLC LSM=46.69, 95% CI [40.51, 52.87]; d=.51) at T3 relative to those in the WLC group. See supplemental table 2 for detailed results of unadjusted means for self-reported measures.

CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this pilot RCT was to demonstrate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a DY intervention for patients undergoing TRT and their family caregivers, targeting patient physical function and patient and caregiver depressive symptoms and QOL. The results revealed that the trial was feasible, as it met our a priori feasibility criteria regarding consent, retention, and adherence rates. Of note, 80% of the dyads attended all 15 DY sessions, which is remarkable considering that the majority of the patients had stage III disease and were undergoing aggressive chemoradiation. All of the patients and caregivers considered the intervention to be useful and beneficial, which they further demonstrated by their yoga practice outside of class. Based on clinically significant improvements in objective and self-reported measures, the DY program may be efficacious in improving patients’ physical function. We also observed clinically significant improvements in patients’ social function across the 3-month follow-up period and short-term clinically significant gains in the role performance and mental health domains as well depressive symptoms. The caregivers’ treatment response was less pronounced than that of the patients. Although we found no role differences at baseline regarding depressive symptoms, unlike patients, caregivers in the DY group did not show improvements across the follow-up period. Regarding QOL, effect sizes for caregivers ranged from small to medium, with marginal clinically significant improvements in vitality and role performance, two important aspects of QOL that are relevant to providing quality care and support to patients.

Based on these findings, an efficacy RCT is warranted. Although the current feasibility trial has provided an essential foundation for evaluating the effects of a dyadic supportive care approach, remaining crucial issues must be addressed in future research. For example, whether a dyadic intervention is in fact superior to a patient-only approach in general and in this particular patient population is unclear. Although caregivers’ responsiveness to the dyadic intervention was modest and thus may not appear to provide a strong rationale for a dyadic intervention, the larger intervention context must be considered. Enrolling patients and caregivers jointly may increase feasibility with regard to consent and adherence rates as demonstrated herein and in the behavior change literature.32,33 Without the support of a family caregiver, a patient may be less likely to attend yoga sessions and practice it at home, which may compromise treatment efficacy. Moreover, patients indicated that they enjoyed and preferred participating with their family members, which may account for the clinically significant improvements in social function we observed. Our next study will include qualitative interviews and pinpointed measures to examine the relationship constructs (i.e., illness communication) as a potential intervention mechanism. Also, given the interdependence of depressive symptoms and QOL, even small treatment effects on caregivers may have systemic implications and thus, optimize patients’ responses.

Nevertheless, several patients were ineligible for the present study because they lacked family caregivers who were able to participate, which may potentially limit external validity and feasibility of a larger trial. To remedy these concerns, we propose the use of videoconferencing delivery, which we are currently testing. As opposed to one primary caregiver, enrolling alternate caregivers who attend only a subset of sessions may also increase patient eligibility. Regarding the caregivers, their treatment responses may have been limited because their primary focus may have been supporting patients as opposed to practicing self-care. Although caregivers’ consent and retention rates tend to be much higher in dyadic intervention studies, they may receive greater benefit from caregiver-only interventions, possibly offering respite from their caregiving. Head-to-head comparisons of dyadic and individual-oriented supportive care are needed to address these central issues in the dyadic intervention literature.34

Future research is also needed to explore the underlying mechanisms of yoga, particularly DY, as in the present study. For patients undergoing TRT, breathing exercises targeting dyspnea, a common side effect, may be a primary mechanism by which yoga protects patients from physical function declines during and after TRT. In fact, patients in the DY group reported significantly less severe dyspnea and perceived less exertion during the 6MWT than did patients in the WLC group. Moreover, examining improvements in dyadic coping or illness communication may also be important mediators to be considered.

Study Limitations

In addition to lacking an active control group, our study is limited by the sample’s fairly homogenous characteristics. Patients and caregivers were psychologically well-adjusted based on the rather low mean CES-D scores, so how patients and caregivers with greater distress would fare with the DY intervention is unclear. Again, an efficacy trial with a larger sample is needed to facilitate subgroup analyses and identify participant characteristics associated with differential treatment responses. Lastly, the pilot RCT was not powered to examine group differences and the initial evidence for efficacy presented here must be interpreted with caution.

Clinical Implications

Clinical implications of the utility of this intervention in the clinical setting are premature at this point. However, the present pilot RCT provides strong evidence of the feasibility of the DY intervention for patients undergoing TRT and their family caregivers based on a priori criteria pertaining to DY consent, adherence, and retention ratings. Patients and caregivers rated the intervention as beneficial and useful. Using clinical cutoff scores, we demonstrated preliminary DY efficacy regarding patients’ QOL and. objectively measured physical function. Thus, the intervention has promise in protecting patients against TRT-related toxicities. Based on these findings, a large, well-controlled efficacy trial of DY is warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Department of Scientific Writing for reviewing this manuscript.

Funding: NIH/NCCIH 1 K01 AT007559, Principal Investigator: Kathrin Milbury

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any actual or potential conflict of interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deng G, Liang N, Xie J, et al. Pulmonary toxicity generated from radiotherapeutic treatment of thoracic malignancies. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(1):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simone CB 2nd. Thoracic Radiation Normal Tissue Injury. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2017;27(4):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal R, Starkschall G, Tucker SL, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on lung function in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(1):114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang XS, Fairclough DL, Liao Z, et al. Longitudinal study of the relationship between chemoradiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and patient symptoms. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4485–4491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besharat S, Jabbari A, Semnani S, Keshtkar A, Marjani J. Inoperable esophageal cancer and outcome of palliative care. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(23):3725–3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Impact of dyspnea, pain, and fatigue on daily life activities in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(5):417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakas T, Lewis RR, Parsons JE. Caregiving tasks among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(5):847–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth S, Silvester S, Todd C. Breathlessness in cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: using a qualitative approach to describe the experience of patients and carers. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1(4):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, McBride CM, Baucom D. Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: associations with symptoms and distress. Pain. 2008;137(2):306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JM, Shaffer KM, Nipp RD, et al. Distress is Interdependent in Patients and Caregivers with Newly Diagnosed Incurable Cancers. Ann Behav Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kershaw T, Ellis KR, Yoon H, Schafenacker A, Katapodi M, Northouse L. The Interdependence of Advanced Cancer Patients’ and Their Family Caregivers’ Mental Health, Physical Health, and Self-Efficacy over Time. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(6):901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmack Taylor CL, Badr H, Lee JH, et al. Lung cancer patients and their spouses: psychological and relationship functioning within 1 month of treatment initiation. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(2):129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badr H, Smith CB, Goldstein NE, Gomez JE, Redd WH. Dyadic psychosocial intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers: results of a randomized pilot trial. Cancer. 2015;121(1):150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4326–4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer H, Lange S, Klose P, Paul A, Dobos G. Yoga for breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Lange S, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ. Yoga for improving health-related quality of life, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD010802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milbury K, Mallaiah S, Lopez G, et al. Vivekananda Yoga Program for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer and Their Family Caregivers. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14(5):446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasymjanova G, Correa JA, Kreisman H, et al. Prognostic value of the six-minute walk in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosher CE, Winger JG, Hanna N, et al. Randomized Pilot Trial of a Telephone Symptom Management Intervention for Symptomatic Lung Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(4):469–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocock S Pocock SJ: Clinical trials: A practical approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granger CL, Holland AE, Gordon IR, Denehy L. Minimal important difference of the 6-minute walk distance in lung cancer. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12(2):146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahler DA, Horowitz MB. Perception of breathlessness during exercise in patients with respiratory disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(9):1078–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oxberry SG, Bland JM, Clark AL, Cleland JG, Johnson MJ. Minimally clinically important difference in chronic breathlessness: every little helps. Am Heart J. 2012;164(2):229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE, Johnston SA, Davies-Avery A, et al. Conceptualization and measurement of health for adults in the Health Insurance Study (Mental Health R-1987/3-HEW: 3). In: Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaasa S, Mastekaasa A, Lund E. Prognostic factors for patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer, limited disease. The importance of patients’ subjective experience of disease and psychosocial well-being. Radiother Oncol. 1989;15(3):235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanchon F, Grivaux M, Asselain B, et al. 4-year mortality in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: development and validation of a prognostic index. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(10):829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead AL, Julious SA, Cooper CL, Campbell MJ. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(3):1057–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace JP, Raglin JS, Jastremski CA. Twelve month adherence of adults who joined a fitness program with a spouse vs without a spouse. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1995;35(3):206–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, et al. Feasibility of a dyadic intervention for management of osteoarthritis: a pilot study with older patients and their spousal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):1036–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.