Abstract

Objectives:

Cardiac involvement is a major determinate of mortality in light chain (AL) amyloidosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) feature tracking (FT) strain is a new method for measuring myocardial strain. This study retrospectively evaluated the association of MRI FT strain with all-cause mortality in AL amyloidosis.

Materials and methods:

Seventy-six patients with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis underwent cardiac MRI. 75 had images suitable for MRI FT strain analysis. MRI delayed enhancement, morphologic and functional evaluation, cardiac biomarker staging and transthoracic echocardiography were also performed. Subjects’ charts were reviewed for all-cause mortality. Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to evaluate survival in univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results:

There were 52 deaths. Median follow-up of surviving patients was 1.7 years. In univariate analysis, global radial (Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.95, p<.01), circumferential (HR=1.09, p< .01) and longitudinal (HR=1.08, p< .01) strain were associated with all-cause mortality. In separate multivariate models, radial (HR=0.96, p=.02), circumferential (HR=1.09, p=.03) and longitudinal strain (HR=1.07, p=.04) remained prognostic when combined with presence of biomarker stage 3.

Conclusions:

MRI FT strain is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with AL amyloidosis.

Keywords: Amyloid, strain, feature-tracking, prognosis, MRI, cardiac

Introduction

Amyloid light chain (AL) type amyloidosis is a rare systemic disease in which fibrils, made up of plasma cell derived immunoglobulin light chain precursor proteins, deposit in tissues leading to organ dysfunction [1]. Cardiac involvement, found in up to 60% of patients, is a major determinate of morbidity and mortality [2].

Abnormal myocardial strain as measured using Doppler ultrasound has been found to be prognostic in AL amyloidosis [3,4]. While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) strain analysis using myocardial tagging is considered as a reference standard for noninvasive strain measurement [5,6], there are many practical limitations to this technique, and it is employed infrequently in the clinical setting [7]. Recently, commercial vendors have introduced feature tracking (FT) strain analysis software, which can be used with MRI cine balanced steady-state free precession (b-SSFP) images to generate strain values in a method analogous to that used for echocardiographic speckle tracking [8].

However, while several other cardiac MRI parameters have been shown to be prognostic in amyloidosis, including delayed enhancement [9,10], native T1 mapping and extracellular volume [11], and while MRI FT strain has been shown to be prognostic in other cardiac conditions [12–15], to date the prognostic significance of MRI FT strain has not been shown in amyloidosis. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to retrospectively evaluate the prognostic value of MRI FT strain for determining all-cause mortality in AL amyloidosis.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Institutional review board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was not required for retrospective medical review. This study is a follow-up of a cohort of patients with amyloidosis originally described by Syed et al. [16], who compared cardiac MRI delayed enhancement to echocardiographic and clinical variables, and subsequently by Boynton et al. [10], who compared delayed enhancement patterns to outcomes.

Inclusion criteria for this study were (1) histologically proven AL type amyloidosis, (2) confirmatory evidence of monoclonal protein in the urine or serum, and/or a monoclonal population of plasma cells in the bone marrow, (3) cardiac MRI ordered for evaluation of cardiac amyloidosis between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2007, (4) cardiac MRI performed within 3 months of initial amyloid diagnosis, and (5) age ≥18 years.

Exclusion criteria were (1) history of myocardial infarction (MI) or myocarditis, (2) previous peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or (3) history of prior heart transplant. Of 151 patients with documented amyloidosis who underwent cardiac MRI at our institution during this time frame, 76 were included in this study. Of these patients, one patient’s images were ungated and not suitable for MRI FT strain analysis. Therefore, 75 patients were analysed for MRI FT strain and ventricular mass and volumes, while the entire cohort of 76 subjects was included for delayed enhancement and other MRI parameters.

MRI b-SSFP acquisition

All examinations were performed on a 1.5 T system (Twin Speed EXCITE, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using an 8-channel phased array cardiac coil. Following 3-plane localizer acquisition, 2-chamber balanced Steady State Free Precession (b-SSFP) scout images were acquired, which were then used to prescribe a short-axis scout sequence. A 4-chamber cine b-SSFP acquisition was prescribed using the 2-chamber and short-axis scout images, and then short-axis cine b-SSFP views were obtained using 2-chamber, 4-chamber and short-axis scout images for positioning. Additional 2-chamber, 3-chamber and 4-chamber cine b-SSFP views were acquired after the short-axis acquisition. Imaging parameters for the ECG-gated cine b-SSFP acquisitions included: Repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) 3.6/1.6 ms, flip angle 45°, receiver bandwidth 100 kHz, 16–20 views per segment, image matrix 256 × 256, 8 mm thickness with no gap, field of view 34–44 cm, phase field of view 0.8–1.0.

MRI FT strain analysis

MRI FT strain analysis was performed on short-axis and three long-axis cine b-SSFP images using commercial software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Inc., Calgary, CA), whose FT strain module has not been approved for clinical use by the Food and Drug Administration as of this writing. Endocardial and epicardial borders were manually traced on b-SSFP end-diastolic images with subsequent automatic tracking of the traces through the remainder of the cardiac cycle. Automated traces were visually inspected and manually corrected.

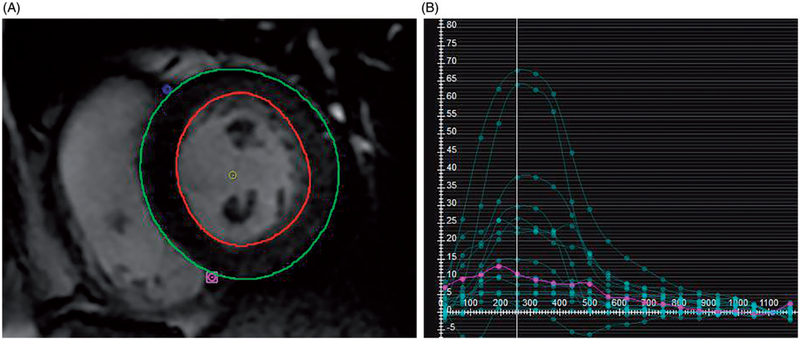

Global radial and circumferential strain was calculated from short-axis b-SSFP images. The most basal slice included constituted the first slice beyond the left ventricular outflow tract. The last apical slice included was the last slice with visible left ventricular cavity throughout the cardiac cycle. All slices between these locations were included in the analysis. Time-strain plots of radial and circumferential strain were generated for each short-axis slice, and from these, global average radial and circumferential strain were calculated by incorporating data from all included slices. Example of radial strain calculation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Radial Strain Calculation MRI Feature Tracking (FT) Strain Measurement. (A) On b-SSFP images, the left ventricular epicardial and endocardial contours are manually traced, with exclusion of the papillary muscles. After tracing multiple short axis levels at diastole, MRI FT software generates multiple regional strain curves shown in (B). The y-axis indicates the unitless strain values and the x-axis measures milliseconds after the R wave. From these regional strains a global radial strain is calculated.

Global longitudinal strain was calculated from 2-chamber, 3-chamber and 4-chamber long-axis images. For each long-axis orientation, global time-strain plots of longitudinal strain were generated, with measurement of peak systolic strain. Peak systolic strain values views were averaged to generate a peak global longitudinal strain.

MRI delayed enhancement acquisition

Delayed enhancement images were obtained between 7 and 12 min after an intravenous bolus of 0.2 mmol/kg gadodiamide (Omniscan; GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) with segmented inversion recovery fast gradient echo sequences with the following parameters: TE = 1.6 ms, TR = 3.7 ms, flip angle 20 degrees, matrix 256 × 160, field of view (FOV) = 320 mm. Multiple inversion time (TI) cine fast gradient echo sequences were obtained to determine the TI with maximal myocardial nulling for delayed enhancement images. 40 images were obtained on a single slice with varying TI with the best time selected for delayed enhancement sequences.

Delayed enhancement image interpretation

Delayed enhancement was interpreted in the manner described by Boynton et al. [10]. Delayed enhancement pattern was evaluated by two observers by consensus who categorized delayed enhancement into one of the three categories. (1) “Global”, where the inversion recovery images showed circumferential, diffuse delayed enhancement extending from the endocardium to the epicardium or where the myocardium was unable to be nulled adequately after multiple varying TI sequences or if on visual inspection of the multiple TI cine fast gradient echo sequence myocardial tissue crossed the null point (became black) prior to the blood pool. (2) “Focal Patchy”, where there were non-diffuse, discrete areas of delayed enhancement, including circumferential delayed enhancement confined to the endocardium or (3) “None”, where there were no areas of delayed enhancement and myocardial tissue did not cross the null point prior to the blood pool on the multiple TI cine fast gradient echo sequence.

MRI derived morphology and functional data

Myocardial mass, the left ventricular (LV) volumes and right ventricular (RV) volumes were evaluated by manually tracing epicardial and endocardial borders on the short-axis SSFP cine sequences on commercially available post processing software (MASS Analysis 6+; Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands). Indexed values were obtained by dividing each by the patient’s body surface area (BSA).

Additional measurements evaluated were the LV myocardial thickness, RV myocardial thickness, and the presence or absence of pericardial and pleural effusions. Myocardial thickness was measured on short-axis images during end diastole. Pericardial effusion and pleural effusion were documented as present or absent.

Cardiac biomarkers

Serum cardiac biomarkers were used to stage patients with the Mayo staging system, developed by Dispenzieri et al. [17], which is based on cardiac troponin T (cTnT) levels and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels. The staging system uses a cTnT threshold level 0.035 mg/L and NT-proBNP threshold level ≥332 ng/L. If both biomarkers were below their respective threshold levels, the patient was designated Stage I; if either cTNT or NT-proBNP were elevated they were designated Stage II, and if both cTNT and NT-proBNP were elevated they were designated Stage III. Serum biomarkers obtained within three months of the MRI were used.

Echocardiographic diastolic function data

All patients received standard transthoracic echocardiograms as part of their work-up. Diastolic data were obtained at the apical four-chamber acoustic window using 2D and Doppler color flow techniques. Mitral flow velocities included the peak mitral flow velocity of the early rapid filling wave (E velocity), the peak velocity of the late filling wave due to atrial contraction (A velocity), the ratio of the E velocity over the A velocity (E/A ratio) and the interval from the peak of the E velocity to its extrapolation to baseline (deceleration time [DT]). Mitral annulus velocities were obtained by placing a sample volume over the medial or lateral portion of the annulus and measuring excursion during diastole (e′). The ratio of the early mitral flow velocity to the mitral annulus velocity was also recorded (E/e′ ratio).

Other variables

All patients received a standard 12-lead resting electrocardiogram (ECG) during their initial assessment. Measured height and weight were used to calculate the body mass index (BMI), defined as the weight divided by the body surface area. Subjective functional status was assigned according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification criteria and was obtained from chart review.

Clinical follow-up

The outcome variable for this study was death from any cause. The medical records at our institution were reviewed for documentation of death. Documentation included a system notification of death, an electronic copy of a death certificate, a medical provider’s note of death or documentation of correspondence by a relative that the patient had died. Patients were censored if they did not have a documented date of death, were documented to be alive at the end of the study, or were lost to follow-up in which case their last clinic visit or correspondence to the institution was used, whichever came later. Abstraction of the medical records was done by a physician blind to the interpretation of MRI variables.

Statistical analysis

As stated previously, of the 76 patients, one patient’s b-SSFP images were considered suboptimal for MRI FT strain or ventricular volume measurements. Therefore, MRI FT strain, as well as ventricular mass and volumes, were assessed for 75 patients. Prognostic data for all 76 subjects were available with regard to delayed enhancement. Biochemical biomarker analysis was limited to the 69 subjects who had both cTnT and NT-proBNP data. Echocardiographic data were available for all 76 patients.

All statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (JMP version 9, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and counts/ percentages for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate overall survival. Survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed for radial, circumferential and longitudinal strain, using death as the positive outcome. Area under the curve (cTnT) was calculated. For each type of strain, the value which maximized the Youden’s index ([sensitivity – (1 – specificity)]; i.e. the difference between the true positive rate and the false positive rate) was chosen as a threshold and used to make Kaplan–Meier curves for each type of strain, comparing the survival of subjects with strain values above and below the threshold using the log-rank method.

For univariate analysis, Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to evaluate survival. For the three delayed enhancement patterns (Global, Focal Patchy, None), Cox proportional hazards was used to determine if there was any significance among any of the three patterns and for this, overall p-values was reported. A similar procedure was used for the three biochemical biomarker stages.

For multivariate analysis, Cox proportional hazards analysis was also used, and three separate multivariate models were created, in which radial, circumferential and longitudinal strain were each combined with biomarker stage 3 in separate multivariate models.

Results

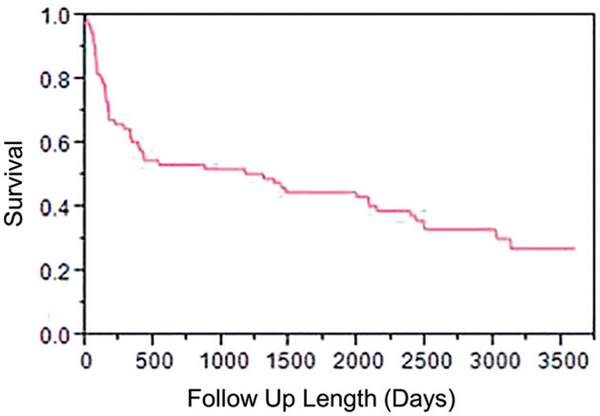

Demographic and clinical features of the patient cohort are summarized in Table 1. Median study follow-up of surviving subjects was 1.7 years (mean follow-up 3.9 years). There were 52 deaths (68%), with survival probability of 60, 52 and 45% at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and univariate analyses.

| Variable | Value (n and % or ± SD) | HR, 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (n = 76) | |||

| Age (years) | 59.7 ± 9.6 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | .10 |

| Female sex | 25 (33%) | 0.63 (0.34–1.12) | .11 |

| NYHA functional class III to IV | 22 (29%) | 2.83 (1.57–4.97) | <.001 |

| ECG limb lead voltage (mm) | 6.7 ± 3.2 | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | .001 |

| MRI straina (n = 75) | |||

| Radial strain (SAX) | 24 ± 10 | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | <.01 |

| Circumferential strain (SAX) | −14 ± 5 | 1.09 (1.02–1.16) | <.01 |

| Longitudinal strain | −14 ± 5 | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | <.01 |

| Delayed enhancement (n = 76) | |||

| Delayed enhancement - Overall | .04b | ||

| Global | 32 (42%) | 2.06 (1.19–3.59) | .01 |

| Focal Patchy | 24 (32%) | 0.65 (0.34–1.19) | .17 |

| None | 20 (26%) | 0.66 (0.34–1.21) | .18 |

| MRI massc and wall thickness (n = 75) | |||

| Indexed LVM (g/m2) | 72 ± 26 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | .02 |

| Indexed RVM (g/m2) | 24 ± 8 | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | .03 |

| Maximum LV wall thickness (mm) | 15 ± 3 | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) | <.01 |

| Maximum RV wall thickness (mm) | 6 ± 2 | 1.25 (1.09–1.43) | <.01 |

| CMR volumeb (n = 75) | |||

| Indexed LVEDV (mL/m2) | 49 ± 12 | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | .89 |

| Indexed LVESV (mL/m2) | 21 ± 9 | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | .04 |

| Indexed LVSV (mL/m2) | 28 ± 8 | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | .01 |

| LVEF (%) | 58 ± 13 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | <.01 |

| Indexed RVEDV (mL/m2) | 65 ± 18 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | .30 |

| Indexed RVESV (mL/m2) | 39 ± 16 | 1.02 (1.00 –1.05) | .02 |

| Indexed RVSV (mL/m2) | 26 ± 9 | 0.97 (0.94–1.01) | .10 |

| RVEF (%) | 41 ± 12 | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | .02 |

| Cardiac biochemical biomarkers (n = 69) | |||

| Biochemical biomarker stage - Overall | – | .01d | |

| Stage 1 | 13 (19%) | 0.52 (0.21–1.09) | .09 |

| Stage 2 | 29 (42%) | 0.69 (0.37–1.24) | .21 |

| Stage 3 | 27 (39%) | 2.44 (1.34–4.39) | <.01 |

| Log (NT-Pro BNP) | 0.42 ± 1.68 | 1.58 (1.29–1.96) | <.001 |

| Log (cTNT) | −3.52 ± 1.14 | 1.60 (1.26–2.03) | <.001 |

| TTE diastolic parameters (n = 76) | |||

| E velocity (m/s) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.02 (0.29–3.42) | .98 |

| A velocity (m/s) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.17 (0.04–0.70) | .01 |

| E/A ratio | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.57 (1.13–2.21) | <.01 |

| e′ (m*102/s) | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 0.83 (0.72–0.94) | <.01 |

| E/e′ ratio | 19.5 ± 12.0 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | .44 |

| Deceleration time (cm/s) | 189 ± 55 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | .08 |

| Other (n = 76) | |||

| Pericardial effusion-no. (%) | 42 (55) | 1.84 (1.06–3.30) | .03 |

| Pleural effusion-no. (%) | 35 (46) | 2.71 (1.55–4.80) | <.001 |

Hazard ratios for strain variables are for one strain unit.

Indicates that there is a statistically significant difference among the three delayed enhancement patterns without indicating which is most associated with adverse prognosis.

Hazard ratios for mass variables are for one gram of mass. For volumes, hazard ratios are for 1 mL/m2 of indexed volume or one percent ejection fraction.

Indicates that there is a statistically significant difference among the three biomarker stages without indicating which is most associated with adverse prognosis.

BP: blood pool; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LV: left ventricle; LVEDV: left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV: left ventricular end systolic volume; LVM: left ventricular mass; LVSV: left ventricular stroke volume; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NTproBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; RV: right ventricle; NYHA: New York Heart Association; RVEDV: right ventricular end diastolic volume; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; RVESV: right ventricular end systolic volume; RVM: right ventricular mass; RVSV: right ventricular stroke volume; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography.

Figure 2.

Overall survival curve showing the survival of the cohort as a function of time after initial diagnosis.

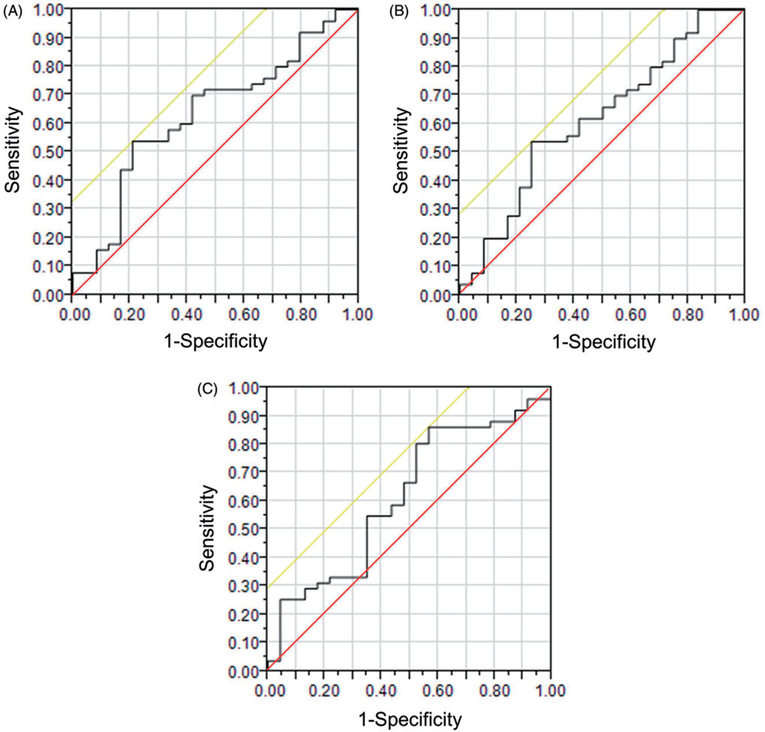

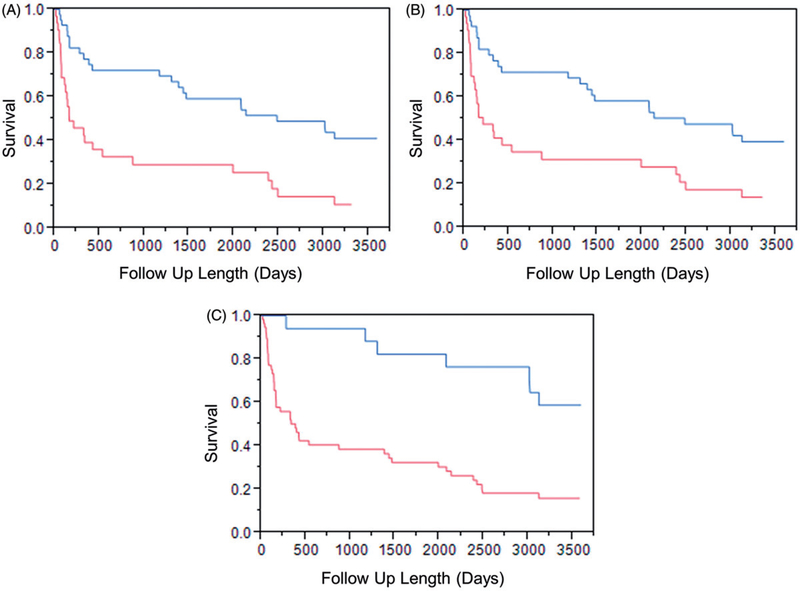

ROC curves were created for radial, circumferential and longitudinal strain and are shown in Figure 3. AUC for radial strain was 0.635, for circumferential strain was 0.619, and for longitudinal strain was 0.619. The threshold which maximized the Youden’s index for radial strain was 20.135, for circumferential strain was −13.414, and for longitudinal strain was −16.095. For radial strain, patients with strain values greater than the threshold had better survival than patients with strain lower than the threshold (p<.001). Circumferential and longitudinal strains are negative and a lower (more negative) value indicates greater displacement. For circumferential and longitudinal strain, patients with strain values lower (more negative) than the threshold had better survival (circumferential strain p=.001; longitudinal strain p<.001). Kaplan–Meier curves showing survival for patients above and below these thresholds are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves for (A). radial strain with area under the curve (AUC)=0.635, (B) circumferential strain with AUC=0.619, and (C) longitudinal strain with AUC=0.619. The diagonal line bisecting the graph (i.e. running from the point 0.00, 0.00 to the point 1.00, 1.00) is the line of nondiscrimination, which is the expected ROC curve for a test that yielded random results. The other diagonal line (running slightly superior and to the left of the ROC curve) shows the tangent through the point which maximized Youden’s index and was used as the threshold for subsequent Kaplan–Meier curves.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier Curves for (A) radial, (B) circumferential and (C) longitudinal strain with thresholds obtained from receiver operator curves. For radial strain, which is a positive, patients with strain greater than the threshold had better survival (p<.001). Circumferential and longitudinal strain are negative and for those strains, patients with strains lower (more negative) than the threshold had better survival. Circumferential strain p=.001. Longitudinal strain p<.001.

At univariate analysis radial, circumferential and longitudinal strain were each prognostic for all-cause mortality (Table 1). At multivariate analysis, radial (Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.96, p=.02), circumferential (HR=1.09, p=.03) and longitudinal (HR=1.07, p=.04) strain remained prognostic for all-cause mortality when combined with the presence of biomarker stage 3 (Tables 2–4). Hazard ratios are for an increase in one unit of strain.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis radial strain with biomarker stage 3.

| Variable | HR, 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Radial strain | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) | .02 |

| Biomarker stage 3 | 1.83 (0.96–3.46) | .07 |

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis longitudinal strain with biomarker stage 3.

| Variable | HR, 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal strain | 1.07 (1.00–1.13) | .04 |

| Biomarker stage 3 | 1.75 (0.91–3.33) | .09 |

Multiple other parameters, which were previously shown to be prognostic by Boynton et al. [10], were again shown to be prognostic in univariate analysis (Table 1). In particular, delayed enhancement pattern, MRI mass, wall thickness and volume parameters were all prognostic in univariate analysis, as well as multiple echocardiographic diastolic parameters, biochemical biomarker stage and the presence of pericardial effusion and pleural effusion.

Discussion

This study showed that MRI FT peak systolic strain was associated with worse prognosis in univariate and multivariate analysis in patients with AL amyloidosis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show MRI FT strain provides prognostic information in AL amyloidosis. To date, MRI FT strain has been used in diagnosis of AL amyloid, by showing that patients with biopsy proven cardiac amyloidosis have decreased strain compared to normal controls [18,19]. However, our study is the first to show that MRI FT strain provides prognostic information in AL amyloidosis.

Our finding suggests that MRI FT strain can be added to the numerous other cardiac MRI parameters that are prognostic in amyloidosis. Myocardial delayed enhancement [9,10], non-contrast T1 mapping and myocardial extracellular volume [11] have been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes. More traditional cardiac parameters, such as myocardial wall thickness and ventricular volumes, also add prognostic information [9], as well as non-cardiac findings such as the presence of pleural effusion. As b-SSFP images are already obtained for measurement of wall thickness and ventricular volumes, MRI FT strain can be measured without obtaining additional sequences.

This study also adds to the MRI FT strain prognostic literature, which has grown rapidly in large part due to the ability to retrospectively measure MRI FT strain from b-SSFP images. MRI FT strain parameters at baseline have been shown to predict outcomes in Tetralogy of Fallot in 372 patients with a median follow-up of 7.4 years [12], dilated cardiomyopathy in 210 patients with a median follow-up of 5.3 years [13], hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 30 patients with a median follow-up of [14], a mixed cohort of 364 patients with a variety of cardiac conditions for a median follow-up of 15 months [15]. In contrast, MRI tagging was first described in 1988 [5], but because tagging requires special prospective acquisitions, it was not until 2009 that a paper from the Multi-Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study showed the association of baseline MRI tagging strain with outcomes in a large population of 1099 subjects [20].

This study adds to the literature showing that MRI FT strain can add incremental prognostic data in multivariate analysis. In the current study, global radial, circumferential and longitudinal strain remained prognostic when separately combined with biomarker stage 3 in multivariate analysis. In 210 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, Buss et al. [13] prospectively found that global longitudinal strain remained prognostic when combined with BNP, LV ejection fraction and mass of delayed enhancement (p<.02). In 364 patients with ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, valvular heart disease and congenital heart disease, Yang et al. [15] retrospectively found that global transverse strain (radial strain measured from long axis images) remained prognostic when combined with age, sex and LV ejection fraction (p=.04).

While, MRI FT strain does have numerous advantages, issues relating to reproducibility remain in the literature. Global strain measurements (as used in this study) have been generally reported to have good interobserver variability [21,22]. Global circumferential strain in particular has been shown to have better interobserver reproducibility [21,23,24]. However, several studies have shown that regional strain measurements have worse reproducibility than global strain measurements [25–27], which may be a limitation in conditions which have regional variation in strain, such as amyloidosis in which strain is typically more abnormal in the base and spared at the apex [28]. In addition, variability between commercial software has been reported [22].

This study has several limitations. This study did not incorporate T1 mapping or extracellular volume analysis, which have recently been shown to be associated with all-cause mortality in univariate analysis [11]. Unfortunately, the image acquisition (obtained in 2006 and 2007) did not allow for retrospective T1 mapping in these patients. Also, this study did not consider patient treatment and response to treatment. As a tertiary referral institution, many patients undergo diagnostic evaluation but then return for treatment at their home institution. While mortality data are available, data on response to treatment is incomplete and was therefore not included in this study. Also, the outcome in this study was all-cause mortality. Cardiovascular mortality was not available, and that is another limitation of this study.

Conclusions

Our study showed that MRI FT strain is associated with all-cause mortality and adds incremental prognostic information over biomarker stage in patients with AL cardiac amyloidosis.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis circumferential strain with biomarker stage 3.

| Variable | HR, 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Circumferential strain | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | .03 |

| Biomarker stage 3 | 1.90 (1.00–3.58) | .05 |

Acknowledgments

Funding

This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Abbreviations:

- AL

amyloid light chain

- AUC

area under the curve

- b-SSFP

balanced steady state free precession

- BMI

body mass index

- BSA

body surface area

- cTnT

cardiac troponin

- DT

deceleration time

- ECG

electrocardiography

- FT

feature tracking

- LV

left ventricle

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- RV

right ventricular

- T

Tesla

- TE

echo time

- TR

repetition time

- TI

inversion time

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Falk RH, Comenzo L, Skinner M. The systemic amyloidoses. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:898–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koyama J, Falk RH. Prognostic significance of strain Doppler imaging in light-chain amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barros-Gomes S, Williams B, Nhola LF, et al. Prognosis of light chain amyloidosis with preserved LVEF: added value of 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography to the current prognostic staging system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zerhouni EA, Parish DM, Rogers WJ, et al. Human heart: tagging with MR imaging-a method for noninvasive assessment of myocardial motion. Radiology. 1988;169:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Young AA, Axel L, Dougherty L, et al. Validation of tagging with MR imaging to estimate material deformation. Radiology. 1993;188:101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ibrahim el SH. Myocardial tagging by cardiovascular magnetic resonance: evolution of techniques–pulse sequences, analysis algorithms, and applications. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hor KN, Gottliebson WM, Carson C, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance feature tracking for strain calculation with harmonic phase imaging analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fontana M, Pica S, Reant P, et al. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2015;132:1570–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boynton SJ, Geske JB, Dispenzieri A, et al. LGE provides incremental prognostic information over serum biomarkers in AL cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Banypersa SM, Fontana M, Maestrini V, et al. T1 mapping and survival in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2015;6:244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Orwat S, Diller GP, Kempny A, et al. Myocardial deformation parameters predict outcome in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Heart. 2016;102:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Buss SJ, Breuninger K, Lehrke S, et al. Assessment of myocardial deformation with cardiac magnetic resonance strain imaging improves risk stratification in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16: 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Smith BM, Dorfman AL, Yu S, et al. Relation of strain by feature tracking and clinical outcome in children, adolescents, and young adults with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1275–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yang LT, Yamashita E, Nagata Y, et al. Prognostic value of biventricular mechanical parameters assessed using cardiac magnetic resonance feature-tracking analysis to predict future cardiac events. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Syed IS, Glockner JF, Feng D, et al. Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, et al. Serum cardiac troponins and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: a staging system for primary systemic amyloidosis. JCO. 2004;22: 3751–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bhatti S, Vallurupalli S, Ambach S, et al. Myocardial strain pattern in patients with cardiac amyloidosis secondary to multiple myeloma: a cardiac MRI feature tracking study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pandey T, Alapati S, Wadhwa V, et al. Evaluation of myocardial strain in patients with amyloidosis using cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2017;46: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cheng S, Fernandes VR, Bluemke DA, et al. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Padiyath A, Gribben P, Abraham JR, et al. Echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance-based feature tracking in the assessment of myocardial mechanics in tetralogy of Fallot: an intermodality comparison. Echocardiography. 2013;30:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schuster A, Stahnke VC, Unterberg-Buchwald C, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature-tracking assessment of myocardial mechanics: Intervendor agreement and considerations regarding reproducibility. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:989–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Augustine D, Lewandowski AJ, Lazdam M, et al. Global and regional left ventricular myocardial deformation measures by magnetic resonance feature tracking in healthy volunteers: comparison with tagging and relevance of gender. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schuster A, Morton G, Hussain ST, et al. The intra-observer reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial feature tracking strain assessment is independent of field strength. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kempny A, Fernandez-Jimenez R, Orwat S, et al. Quantification of biventricular myocardial function using cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking, endocardial border delineation and echocardiographic speckle tracking in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot and healthy controls. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu L, Germans T, Guclu A, et al. Feature tracking compared with tissue tagging measurements of segmental strain by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Khan JN, Singh A, Nazir SA, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking and tagging for the assessment of left ventricular systolic strain in acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Phelan D, Thavendiranathan P, Popovic Z, et al. Application of a parametric display of two-dimensional speckle-tracking longitudinal strain to improve the etiologic diagnosis of mild to moderate left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]