Abstract

Objective:

To describe the relationship between metabolic health parameters and depressive symptoms and perceived stress, and whether the co-occurrence of these two psychological stressors has an additive influence on metabolic dysregulation in adults at different levels of body mass index (BMI) without diabetes.

Methods:

Participants without diabetes (N=20,312) from the population-based REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study (recruited between 2003–2007) who had a body mass index (BMI) ≥18.5 kg/m2 were included in this cross-sectional analysis. Mean age of sample was 64.4 years, with 36% African American, and 56% women. Depressive symptoms and perceived stress were measured using brief versions of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D-4 item) questionnaire and Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), respectively. Metabolic health parameters included waist circumference, blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), low- and high-density lipoprotein (LDL, HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Sequentially adjusted General Linear Regression Models (GLM) for each metabolic parameter were used to assess the association between having both elevated depressive symptoms and stress, either of these psychological risk factors, or none with all analyses stratified by BMI category (i.e., normal, overweight, and obesity).

Results:

The presence of elevated depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress was generally associated with increased waist circumference, higher CRP, and lower HDL. The combination of depressive symptoms and perceived stress, compared to either alone, was typically associated with poorer metabolic health outcomes. However, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors generally attenuated the associations between psychological factors and metabolic parameters.

Conclusions:

Elevated depressive symptoms in conjunction with high levels of perceived stress were more strongly associated with several parameters of metabolic health than only one of these psychological constructs in a large, diverse cohort of adults. Findings suggest that healthy lifestyle factors may attenuate the association between psychological distress and metabolic health impairment.

Keywords: psychological health, obesity, overweight, metabolic health, adults, depressive symptoms, perceived stress

Introduction

Individuals with obesity are more likely than individuals without obesity to experience elevated blood pressure (BP), elevated triglycerides, low high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, elevated fasting glucose, high waist circumference (WC), and chronic inflammation (e.g., C-reactive protein).1, 2 These cardio-metabolic abnormalities also increase risk for the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD)3 through a variety of biological pathways, such as insulin resistance, adipocyte dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction.4–6

While the physiological mechanisms linking obesity, cardio-metabolic risk factors, diabetes, and CVD have been studied extensively, less is known about the influence of psychological factors. Both elevated levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms have been associated with excess body weight as well as other parameters of metabolic health, such as lipids, blood pressure, and glucose levels.7–13 However, many studies examining the association between psychological factors and metabolic health have focused only on depressive symptoms10, 11, 13 or stress7 but not both. Limited research has focused on both depressive symptoms and perceived stress, with findings identifying unique associations between these two psychological factors and metabolic parameters as well as related outcomes such as weight loss.8, 14 However, it remains unclear whether the co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and perceived stress differentially impacts metabolic health when compared to the presence of only one factor.

Further, previous work has generally utilized a dichotomous, composite measure of metabolic health (i.e., presence/absence of metabolic syndrome).9–12 This is particularly noteworthy given that several studies have separately examined individual parameters of metabolic health and have each demonstrated differential associations with stress and depressive symptoms.7, 8, 11, 13 For example, depressive symptoms were significantly related to elevated triglycerides and BMI but unrelated to HDL, LDL, BP, WC, or glycemia in one study.8 Yet, another study concluded that depressive symptoms were associated with WC, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL, but unrelated to hyperglycemia or high BP.11 Moreover, other findings suggest that depressive symptoms have the strongest association with HDL levels in women, but the ability to detect associations between depressive symptoms and other components of metabolic health (e.g., triglyceride levels, WC) differs based on how the metabolic components are defined.13 Specifically, the associations between depressive symptoms and these metabolic components were identified when the authors examined the metabolic components on a continuous scale rather than a dichotomous one (i.e., using cutoff values).

We propose to extend prior research by examining 1) which metabolic health parameters are associated with depressive symptoms and perceived stress, and 2) whether the co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and perceived stress has an additive influence on metabolic dysregulation across excess weight status (i.e., stratified by BMI to normal, overweight, and obesity groups). Such work may have implications for the identification of high-risk individuals as well as the prevention of CVD and diabetes among these individuals. We hypothesized that the presence of depressive symptoms and perceived stress will be independently associated with poorer metabolic health (individual measures examined continuously and dichotomously). We also hypothesized that the combined presence of elevated stress and depressive symptoms will demonstrate a stronger association with poor metabolic health than either risk factor alone. Furthermore, we hypothesized that metabolic health would be poorer with increased combined stress and depressive symptoms when examining these psychological factors using a finer categorical approach (i.e., low, moderate, high).

Methods

Study population

The REasons for Geographic And Racial Disparities in Stroke (REGARDS) study is a population-based, longitudinal cohort study that was designed to examine the incidence and causes of stroke as well as geographical and racial/ethnic disparities in stroke risk factors among North Americans. A description of the study and its methods has been published.15 Briefly, REGARDS enrolled 30,239 participants aged ≥45 years at baseline (2003–2007). In this stratified random sample, 44% were men and 64% were White; 55% were recruited from the southeastern U.S., while the remaining 45% represented other regions of the contiguous U.S. Baseline data were collected using a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) and an in-home examination. The CATI was conducted by trained research staff, and the in-home examination was conducted by trained health professionals. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of participating institutions and all participants provided written informed consent.

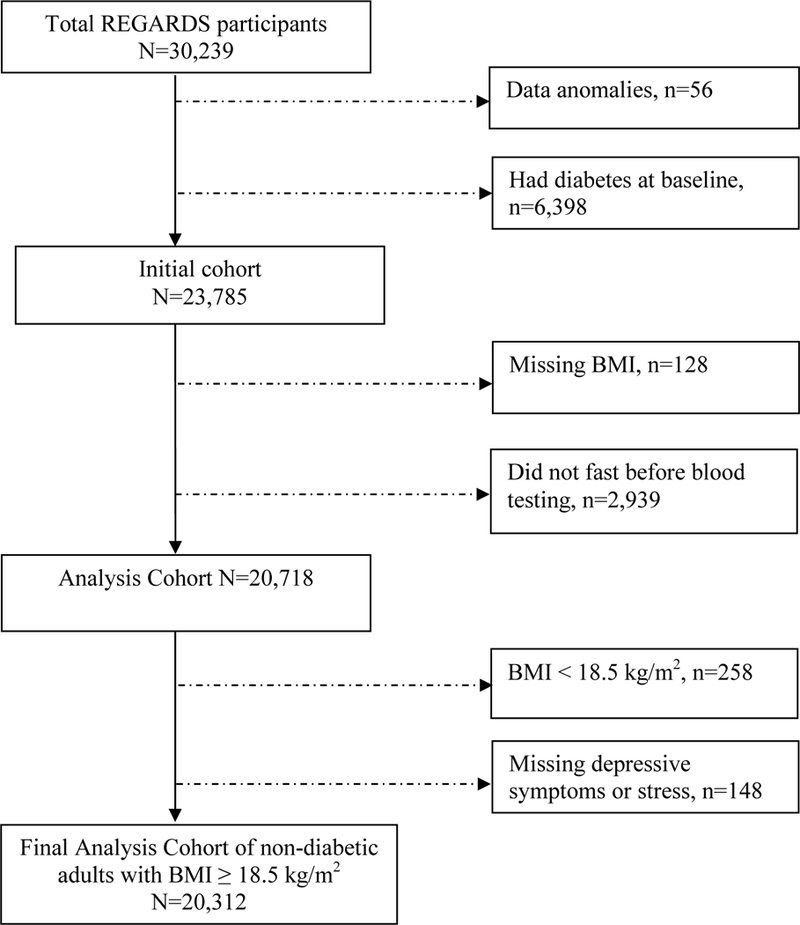

The current analyses included participants who had a BMI≥18.5 kg/m2 and did not have diabetes at baseline. Body mass index (BMI) was measured during the in-home visit and calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L, random glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or self-reported diabetes with use of oral or injectable hypoglycemic medication. After excluding those missing data for BMI, depressive symptoms, or perceived stress and those who indicated that they did not fast overnight, the final sample size for this analysis was 20,312 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exclusion cascade

Measures

Covariates.

Participants self-reported age, race, sex, household income, and education level. Current medication use, including anti-hypertensive medications, statins, insulin, oral diabetes medications, and anti-depressant medications was assessed via medication inventory review during the in-home visit. Participants self-reported smoking status, alcohol use, and physical activity. Smoking status was categorized as ‘never smokers’, ‘current smokers’, or ‘former smokers’ (smoked at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime). Current alcohol use was assessed with two questions, and participants’ consumption was categorized as ‘heavy’ (>14 drinks per week for men or > 7 drinks per week for women), ‘moderate’ (1–14 drinks per week for men or 1–7 drinks per week for women), or ‘none’, which is consistent with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines.16 Physical activity was assessed with a single item (how often per week do you exercise enough to work up a sweat), and participants were dichotomized as engaging in ‘no activity’ or ‘any activity’. Diet was assessed using the self-administered Block 98 Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), which was validated with two unannounced 24-hour recalls (weekday and weekend) as well as a second FFQ within a year. Mediterranean Diet score was constructed from these data using methods published previously, producing a continuous variable ranging from 0 (low adherence) to 9 (high adherence).17

Main predictor variables.

Depressive symptoms and perceived stress were assessed using validated questionnaires. The 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire was administered during the CATI.18 This abbreviated version of the CES-D is derived from the original, 20-item version19 and has been previously validated and demonstrated high correlations (r=0.87) with the longer, original version.18 CES-D scores on the 4-item version range from 0 to 12. When examining depressive symptoms from a dichotomous perspective (i.e., ‘no depressive symptoms’ or ‘depressive symptoms’), scores ≥4 were indicative of elevated levels of depressive symptoms.20, 21 When using a multi-categorical approach, depressive symptoms were defined as ‘low’ (0), ‘moderate’ (1–3), or ‘high’ (4+). Perceived stress was measured during the CATI with the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).22 The PSS is a validated measure of participant’s perceptions that his/her life is unpredictable, uncontrollable, and/or overcommitted.23 Scores on this measure range from 0 to 16. When examining perceived stress from a dichotomous perspective (i.e., ‘no stress’ or ‘elevated stress’), a PSS score ≥5 (upper tertile of the scores reported by all participants in REGARDS) was used to classify participants as reporting ‘elevated stress’. When using a multi-categorical approach, perceived stress categories were defined using tertiles from the current sample: ‘low’ (0–1), ‘moderate’ (2–4), or ‘high’ (5+). For analyses utilizing dichotomous scoring of responses to both psychological measures (i.e., CES-D and PSS), participants were categorized into one of three groups, i.e., the ‘3-category approach’: 1) no elevations in depressive symptoms or stress, 2) elevations in either depressive symptoms or stress, or 3) elevations in both depressive symptoms and stress. For analyses utilizing the multi-categorical scoring approach, participants were categorized into one of nine groups based on their levels of depressive symptoms and perceived stress (e.g., low depressive symptoms/moderate stress, high depressive symptoms/high stress), described later as the ‘9-category approach’.

Main outcome variables.

The metabolic health parameters assessed were WC, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP; DBP), LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). During the in-home examination, the participant’s WC and BP was measured following a standardized protocol. With the participant standing, WC was measured using a tape measure midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest. After a brief period of rest in a seated position, two blood pressure measurements were taken using an aneroid sphygmomanometer (American Diagnostic Corporation, Hauppauge, NY), and the average of these two measures was recorded. After an ≥8-hour fast, blood samples were collected during the in-home study visit following standardized protocols. Samples were analyzed at a central laboratory. Samples were used to measure LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and hs-CRP in accordance with standardized and validated procedures.24 LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose were measured by colorimetric reflectance spectrophotometry using the Ortho Clinical Vitros 950/IRC Chemistry System (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, New Brunswick, NJ), while hs-CRP was measured using particle-enhanced immunonephelometry using the BNII nephelometer (N High Sensitivity CRP; Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL). These metabolic health parameters were operationalized as continuous and categorical variables for analyses. When defined categorically, standardized guidelines were used to indicate criteria for metabolic dysregulation.25, 26 This included WC >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women; fasting glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L; Hs-CRP ≥3 mg/L; LDL ≥4.1 mmol/L; HDL <1.04 mmol/L in men and <1.3 mmol/L in women; triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L; and SBP ≥130 mmHg or DBP ≥85 mmHg.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were stratified by BMI: ‘normal’ (defined as BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), ‘overweight’ (defined as BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2) and ‘obesity’ (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Socio-demographic characteristics, health behaviors and medication use were compared for participants with elevated depressive symptoms and/or elevated stress and for those who reported neither depressive symptoms nor stress. The Chi-square tests were performed for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. Due to the skewed distribution of the CRP and triglycerides values, a natural logarithmic transformation was used in all analyses.

Sequentially adjusted General Linear Regression Models (GLM) were used to examine associations between psychological symptoms and metabolic outcomes. Two different approaches were used to evaluate these associations. First, a 3-category psychological symptom approach was used to determine the association between individuals with both elevated depressive symptoms and stress, either of these psychological risk factors but not both, or none (referent group) with metabolic parameters. Second, a more graded combination of psychological symptoms (i.e., the 9-category approach) was used to evaluate the associations between depressive symptoms and/or stress and individual metabolic outcomes. GLM models were constructed separately for each metabolic parameter, including WC, fasting glucose, hs-CRP, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, SBP, and DBP. The crude model estimated means and mean difference for each metabolic parameter across all stress-depressive symptoms groups. Model 1 adjusted for sociodemographics (self-reported age, race, sex, household income, and education level), model 2 added adjustments for health behaviors (alcohol, smoking, physical activity, and diet) to model 1 covariates and, finally, model 3 added antidepressant use to model 2 covariates. All models of SBP and DBP additionally adjusted for the use of antihypertensive medications. All adjusted GLM models estimated a difference in least square adjusted means and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each continuous metabolic parameter across all stress-depressive symptoms groups. For the 3-category approach, the ‘no depressive symptoms, no stress’ group was the referent group. For the 9-category approach, the ‘low depressive symptoms, low stress’ group was the referent group. We additionally used unadjusted Chi-square tests to compare categorical metabolic parameters across all stress-depressive symptoms groups within the BMI strata. If covariates were missing for a model, the observations were not included in the analysis; the respective sample size for each analysis is shown by n total. There were less than 0.5% missing from the parameters of WC and BP. The parameters of fasting glucose, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides had between 3–5% missing. Hs-CRP had the most missing with up to 6.5% missing across BMI groups. Mediterranean Diet score, which was a covariate in Models 2 and 3, had 23% missing among the normal BMI, 25% missing among the overweight BMI, and 29% missing among the obese BMI group. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Characteristics of the study sample (N=20,312) are summarized in Table 1. In general, participants reporting elevated psychological symptoms (i.e., depressive symptoms, perceived stress) were more likely to be younger, female, African American, have lower levels of education, less income, and not married. In addition, rates of smoking and physical inactivity were higher and adherence to a Mediterranean diet was lower among participants reporting elevated psychological symptoms. In contrast, alcohol use was inversely related to psychological stressors.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of REGARDS participants by weight status and depressive symptom/stress category, n=20,312

| Normal (BMI=18.5–24.9 kg/m2), n=5587 | Overweight (BMI=25–29.9 kg/m2), n=7961 | Obesity (BMI≥30, kg/m2), n=6764 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depressive Symptoms, |

Depressive Symptoms only or |

Depressive Symptoms AND |

No Depressive Symptoms, |

Depressive Symptoms only or |

Depressive Symptoms AND |

No Depressive Symptoms, |

Depressive Symptoms only or |

Depressive Symptoms AND |

||||

| No Stress (n =3894) |

Elevated Stress only (n=1343) |

Elevated Stress (n =350) |

No Stress (n =5810) |

Elevated Stress only (n=1714) |

Elevated Stress (n = 437) |

No Stress (n = 4426) |

Elevated Stress only (n=1759) |

Elevated Stress (n = 579) |

||||

| n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p- value |

n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p- value |

n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p- value |

|

| Socio-demographics: | ||||||||||||

| Age† | 66.2 (9.8) | 65.8 (11.0) | 63.3 (11.3) | <.001 | 65.3 (9.2) | 64.7 (9.9) | 62.3 (10.0) | <.001 | 63.0 (8.6) | 62.2 (8.9) | 60.2 (8.8) | <.001 |

| Female | 2123 (54.5) | 888 (66.1) | 229 (65.4) | <.001 | 2565 (44.1) | 990 (57.8) | 298 (68.2) | <.001 | 2597 (58.7) | 1264 (71.9) | 456 (78.8) | <.001 |

| African American | 952 (24.4) | 425 (31.6) | 149 (42.6) | <.001 | 1758 (30.3) | 671 (39.1) | 196 (44.9) | <.001 | 1968 (44.5) | 923 (52.5) | 325 (56.1) | <.001 |

| Region:* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| Stroke Buckle | 824 (21.2) | 305 (22.7) | 89 (25.4) | 1189 (20.5) | 350 (20.4) | 114 (26.1) | 949 (21.4) | 413 (23.5) | 145 (25.0) | |||

| Stroke Belt | 1330 (34.2) | 481 (35.8) | 132 (37.7) | 1896 (32.6) | 599 (34.9) | 144 (33.0) | 1452 (32.8) | 595 (33.8) | 213 (36.8) | |||

| Non-Belt | 1740 (44.7) | 557 (41.5) | 129 (36.9) | 2725 (46.9) | 765 (44.6) | 179 (41.0) | 2025 (45.8) | 751 (42.7) | 221 (38.2) | |||

| Less than high school education | 258 (6.6) | 153 (11.4) | 85 (24.3) | <.001 | 453 (7.8) | 209 (12.2) | 86 (19.7) | <.001 | 401 (9.1) | 255 (14.5) | 142 (24.5) | <.001 |

| Annual income < 35,000 | 1332 (34.2) | 584 (43.5) | 216 (61.7) | <.001 | 1911 (32.9) | 750 (43.8) | 263 (60.2) | <.001 | 1605 (36.3) | 859 (48.8) | 368 (63.6) | <.001 |

| Married | 2474 (63.5) | 728 (54.2) | 131 (37.4) | <.001 | 3926 (67.6) | 1010 (58.9) | 191 (43.7) | <.001 | 2691 (60.8) | 939 (53.4) | 231 (39.9) | <.001 |

| Behaviors: | ||||||||||||

| Smoking: | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||||

| Current | 634 (16.3) | 262 (19.6) | 151 (43.4) | 645 (11.1) | 270 (15.8) | 127 (29.2) | 487 (11.0) | 217 (12.4) | 119 (20.6) | |||

| Never | 1868 (48.1) | 628 (47.0) | 114 (32.8) | 2566 (44.3) | 786 (46.0) | 168 (38.6) | 2062 (46.8) | 877 (50.1) | 269 (46.6) | |||

| Past | 1378 (35.5) | 447 (33.4) | 83 (23.9) | 2577 (44.5) | 654 (38.2) | 140 (32.2) | 1860 (42.2) | 655 (37.4) | 189 (32.8) | |||

| Alcohol Use: | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||||

| Heavy | 236 (6.2) | 82 (6.2) | 27 (8.0) | 297 (5.2) | 61 (3.6) | 14 (3.3) | 148 (3.4) | 48 (2.8) | 14 (2.5) | |||

| Moderate | 1544 (40.3) | 460 (34.8) | 105 (31.3) | 2317 (40.5) | 591 (35.3) | 124 (29.1) | 1441 (33.2) | 512 (29.8) | 140 (24.7) | |||

| None | 2055 (53.6) | 779 (59.0) | 204 (60.7) | 3113 (54.4) | 1022 (61.1) | 288 (67.6) | 2755 (63.4) | 1159 (67.4) | 412 (72.8) | |||

| No exercise | 1049 (27.4) | 467 (35.4) | 148 (42.8) | <.001 | 1454 (25.4) | 589 (34.8) | 182 (42.5) | <.001 | 1564 (35.8) | 695 (40.0) | 286 (49.9) | <.001 |

| Mediterranean Diet Score† | 4.6 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.7) | <.001 | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.3 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.6) | <.001 | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.3 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.6) | <.001 |

| Medication Use: | ||||||||||||

| Statins | 955 (24.8) | 311 (23.4) | 84 (24.3) | 0.57 | 1864 (32.4) | 536 (31.6) | 144 (33.4) | 0.71 | 1343 (30.6) | 548 (31.6) | 188 (32.9) | 0.44 |

| Antihypertensives | 1291 (33.4) | 471 (35.5) | 146 (42.0) | 0.004 | 2486 (43.2) | 785 (46.3) | 215 (50.2) | 0.003 | 2480 (56.8) | 1005 (58.2) | 369 (64.4) | 0.002 |

| Antidepressants | 355 (9.1) | 217 (16.2) | 98 (28.0) | <.001 | 566 (9.7) | 261 (15.2) | 129 (29.5) | <.001 | 502 (11.3) | 327 (18.6) | 178 (30.7) | <.001 |

Depressive Symptoms – CES-D ≥ 4, Elevated Stress – PSS ≥ 5

Stroke Buckle includes coastal plain region of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia; Stroke Belt includes remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, plus Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana; Non-belt is represented by the other 40 contiguous states.

Mean and standard deviation given for continuous variables

Psychological Stressors and Individual Indicators of Metabolic Dysfunction

3-Category Approach.

In unadjusted models, the presence of elevated depressive symptoms and/or stress was associated with several parameters of metabolic health, including lower WC, SBP, and higher CRP, HDL, and LDL (Table 2). After adjustment for sociodemographic variables, the associations between depressive symptoms and/or stress and the following metabolic parameters were observed: higher CRP and lower SBP remained statistically significant; the direction of the associations changed to higher WC and lower HDL; a new association emerged with lower DBP; and the association with LDL was attenuated. Furthermore, with the addition of health behaviors (Model 2) and anti-depressant medication use (Model 3) to the models, the associations between depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress and higher WC and lower SBP remained significant only among the obesity group, whereas the association with lower DBP remained significant among the normal BMI and overweight groups. Ofnote, the associations between psychological symptoms and WC were most pronounced when both depressive symptoms and perceived stress were present as compared to when only one of these psychological constructs was reported, and this was more apparent across increasing BMI categories. In contrast, fasting glucose and triglycerides were generally unrelated to elevated depressive symptoms or stress in unadjusted or adjusted models (Table 2). The R2 was determined as a measure of model fit for Model 3 of the dichotomously-scored psychological predictors of metabolic health analyses (see Supplemental Table1). Model fit for Model 3 was determined as it had the maximum predictors of our models. The R2 for WC had the highest R2 ranging from 0.13 in the obesity BMI group to 0.325 in the normal BMI group (i.e., 32.5% of the variation in WC was explained by the model). Glucose had the lowest R2 ranging from 0.013 in the obesity BMI group to 0.053 in the normal BMI group.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted means for the association of depressive symptoms and perceived stress with metabolic health outcomes among adults in REGARDS (cross-sectional baseline comparisons).

| Normal (BMI=18.5–24.9 kg/m2), n=5587 | Overweight (BMI=25–29.9 kg/m2), n=7961 | Obesity (BMI≥30, kg/m2), n=6764 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress (n =3894) |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only (n=1343) |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress (n =350) |

n | No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress (n =5810) |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only (n=1714) |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress (n = 437) |

n | No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress (n = 4426) |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only (n=1759) |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress (n = 579) |

|

|

Waist Circumference, cm | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 81.9 (81.5, 82.2) | 80.5 (79.9, 81.1) | 80.8 (79.7, 81.9) | 92.6 (92.3, 92.8) | 91.8 (91.4, 92.2) | 91.7 (90.8, 92.6) | 105.7 (105.3, 106.0) | 105.7 (105.1, 106.3) | 106.6 (105.6, 107.6) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5568 | ref | −1.4 (−2.0, −0.7)*** | −1.1 (−2.2, 0.0) | 7942 | ref | −0.8 (−1.3, −0.3)** | −0.9 (−1.8, 0.01) | 6733 | ref | 0.1 (−0.6, 0.7) | 0.9 (−0.2, 2.0) |

| Model 1 | 5565 | ref | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.4) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.3) | 7939 | ref | 0.5 (0.1, 1.0)* | 1.6 (0.8, 2.4)*** | 6728 | ref | 0.8 (0.2, 1.5)* | 1.8 (0.7, 2.8)*** |

| Model 2 | 4195 | ref | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.4) | 0.1 (−1.2, 1.4) | 5893 | ref | 0.5 (0.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.1, 2.0)* | 4686 | ref | 1.1 (0.3, 1.9)** | 1.5 (0.2, 2.8)* |

| Model 3 | 4195 | ref | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.3) | −0.1 (−1.4, 1.2) | 5893 | ref | 0.5 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.9 (−0.1, 1.8) | 4686 | ref | 1.0 (0.2, 1.8)* | 1.3 (0.0, 2.6)* |

|

Fasting Serum Glucose, mmol/L | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 5.03 (4.97, 5.09) | 5.00 (4.97, 5.03) | 4.98 (4.96, 5.00) | 5.16 (5.11, 5.22) | 5.15 (5.12, 5.17) | 5.16 (5.14, 5.17) | 5.32 (5.26, 5.37) | 5.30 (5.27, 5.33) | 5.30 (5.28, 5.32) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5386 | ref | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) | 7695 | ref | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | 6467 | ref | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.04, 0.07) |

| Model 1 | 5383 | ref | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) | 0.06 (0.00, 0.12) | 7692 | ref | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.09) | 6464 | ref | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.10) |

| Model 2 | 4077 | ref | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.05 (−0.03, 0.13) | 5737 | ref | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.06) | 4528 | ref | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) |

| Model 3 | 4077 | ref | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.05 (−0.03, 0.12) | 5737 | ref | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.06) | 4528 | ref | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) |

|

Log transformed High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, mg/L | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.28 (0.24, 0.31) | 0.39 (0.33, 0.46) | 0.67 (0.55, 0.80) | 0.89 (0.78, 0.99) | 0.72 (0.66, 0.77) | 0.59 (0.56, 0.62) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.46) | 1.26 (1.21, 1.31) | 1.17 (1.13, 1.20) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5262 | ref | 0.12 (0.04, 0.19)** | 0.40 (0.27, 0.53)*** | 7541 | ref | 0.12 (0.06, 0.18)*** | 0.29 (0.19, 0.40) *** | 6324 | ref | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15)** | 0.21 (0.12, 0.30) *** |

| Model 1 | 5259 | ref | 0.06 ( −0.02, 0.13) | 0.28 (0.14, 0.41) *** | 7538 | ref | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.10) | 0.14 (0.03, 0.25)* | 6321 | ref | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.05) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) |

| Model 2 | 3978 | ref | 0.00 (−0.08, 0.09) | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.25) | 5615 | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.05) | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.13) | 4438 | ref | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.01 (0.11, 0.12) |

| Model 3 | 3978 | ref | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.10) | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.21) | 5615 | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.05) | −0.03 (−0.16, 0.11) | 4438 | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.13, 0.10) |

|

High-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 1.53 (1.48, 1.58) | 1.54 (1.52, 1.57) | 1.51 (1.50, 1.53) | 1.35 (1.31, 1.39) | 1.36 (1.34, 1.38) | 1.34 (1.33, 1.35) | 1.32 (1.29, 1.35) | 1.32 (1.31, 1.34) | 1.28 (1.27, 1.30) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5332 | ref | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.06) | 7657 | ref | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05)* | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 6452 | ref | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06)*** | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07)** |

| Model 1 | 5329 | ref | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | 7654 | ref | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.01)** | 6449 | ref | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.02) |

| Model 2 | 4032 | ref | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | 5709 | ref | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.02) | 4517 | ref | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) |

| Model 3 | 4032 | ref | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.07) | 5709 | ref | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.01) | 4517 | ref | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.03) |

|

Low-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 3.01 (2.91, 3.10) | 2.97 (2.92, 3.02) | 2.97 (2.94, 2.99) | 3.19 (3.10, 3.28) | 3.08 (3.03, 3.12) | 3.05 (3.03, 3.08) | 3.13 (3.05, 3.20) | 3.12 (3.08, 3.16) | 3.06 (3.03, 3.09) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5302 | ref | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.04 (−0.06, 0.14) | 7572 | ref | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | 0.14 (0.05, 0.23)*** | 6381 | ref | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11)* | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.15) |

| Model 1 | 5299 | ref | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.12, 0.08) | 7569 | ref | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) | 6378 | ref | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) |

| Model 2 | 4011 | ref | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.07) | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.18) | 5651 | ref | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.03) | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.05) | 4463 | ref | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.08) | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.12) |

| Model 3 | 4011 | ref | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.19) | 5651 | ref | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.03) | −0.05 (−0.16, 0.07) | 4463 | ref | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.09) | 0.05 (−0.05, 0.16) |

|

Log transformed Triglycerides, mmol/L | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.0522 (0.0517, 0.0528) | 0.0517 (0.0515, 0.0520) | 0.0517 (0.0515, 0.0519) | 0.0539 (0.0534, 0.0545) | 0.0533 (0.0530, 0.0535) | 0.0534 (0.0533, 0.0536) | 0.0541 (0.0536, 0.0545) | 0.0538 (0.0536, 0.0541) | 0.0542 (0.0540, 0.0543) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5385 | ref | 0.0001 (−0.0003, 0.0004) | 0.0005 (0.0000, 0.0011) | 7695 | ref | −0.0002 (−0.0005, 0.0001) | 0.0005 (0.0000, 0.0011) | 6467 | ref | −0.0004 (−0.0007, −0.0001)* | −0.0001 (−0.0006, 0.0004) |

| Model 1 | 5382 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0003, 0.0004) | 0.0005 (−0.0001, 0.0011) | 7692 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0003, 0.0002) | 0.0005 (0.0000, 0.0011) | 6464 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0004, 0.0002) | 0.0002 (−0.0002, 0.0007) |

| Model 2 | 4075 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0004, 0.0003) | 0.0004 (−0.0003, 0.0011) | 5736 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0004, 0.0003) | 0.0003 (−0.0004, 0.0009) | 4528 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0003, 0.0004) | 0.0003 (−0.0003, 0.0008) |

| Model 3 | 4075 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0005, 0.0002) | 0.0002 (−0.0005, 0.0009) | 5736 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0004, 0.0003) | 0.0002 (−0.0005, 0.0009) | 4528 | ref | 0.0000 (−0.0004, 0.0003) | 0.0002 (−0.0004, 0.0008) |

|

Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 123.1 (122.6, 123.7) | 122.0 (121.1, 122.9) | 124.0 (122.2, 125.8) | 126.5 (126.1, 126.9) | 125.9 (125.1, 126.6) | 127.1 (125.6, 128.6) | 129.7 (129.2, 130.2) | 129.3 (128.5, 130.0) | 128.9 (127.6, 130.2) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5585 | ref | −1.1 (−2.2, −0.1)* | 0.9 (−1.0, 2.7) | 7958 | ref | −0.6 (−1.5, 0.2) | 0.6 (−0.9, 2.2) | 6755 | ref | −0.4 (−1.3, 0.4) | −0.8 (−2.1, 0.6) |

| Model 1 | 5533 | ref | −1.3 (−2.2, −0.3)* | 0.1 (−1.6, 1.9) | 7878 | ref | −0.7 (−1.6, 0.1) | 1.0 (−0.5, 2.5) | 6655 | ref | −0.6 (−1.5, 0.2) | −1.0 (−2.4, 0.4) |

| Model 2 | 4165 | ref | −1.1 (−2.3, 0.0)* | −1.0 (−3.1, 1.1) | 5853 | ref | −0.8 (−1.8, 0.1) | −0.6 ( −2.5, 1.2) | 4642 | ref | −1.2 (−2.2, −0.2)* | −1.8 (−3.4, −0.1)* |

| Model 3 | 4165 | ref | −1.0 (−2.2, 0.1) | −0.8 (−2.9, 1.3) | 5853 | ref | −0.8 (−1.7, 0.2) | −0.4 ( −2.2, 1.5) | 4642 | ref | −1.1 (−2.1, −0.1)* | −1.4 (−3.1, 0.2) |

|

Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 74.1 (73.8, 74.4) | 73.5 (73.0, 74.0) | 74.8 (73.9, 75.8) | 76.4 (76.2, 76.7) | 76.3 (75.8, 76.7) | 77.2 (76.4, 78.1) | 79.2 (78.9, 79.5) | 79.1 (78.7, 79.5) | 79.5 (78.7, 80.3) | |||

| Differences (95% CI): | ||||||||||||

| Crude Mean | 5585 | ref | −0.6 (−1.1, 0.0) | 0.8 (−0.2, 1.8) | 7958 | ref | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) | 0.8 (−0.1, 1.7) | 6755 | ref | −0.1 (−0.6, 0.4) | 0.3 (−0.5, 1.2) |

| Model 1 | 5533 | ref | −0.7 (−1.2, −0.1)* | −0.1 (−1.2, 0.9) | 7878 | ref | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.2) | 0.4 (−0.5, 1.3) | 6655 | ref | −0.3 (−0.8, 0.3) | −0.2 (−1.1, 0.6) |

| Model 2 | 4165 | ref | −1.0 (−3.1, 1.1)** | −0.8 (−2.1, 0.4) | 5853 | ref | −0.6 (−1.2, −0.1)* | −0.5 ( −1.6, 0.6) | 4642 | ref | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.3) | −0.2 (−1.3, 0.8) |

| Model 3 | 4165 | ref | −1.0 (−1.7, −0.3)** | −0.8 (−2.0, 0.4) | 5853 | ref | −0.6 (−1.2, −0.1)* | −0.4 ( −1.5, 0.7) | 4642 | ref | −0.3 (−1.0, 0.3) | −0.1 (−1.1, 1.0) |

p-value <. 05,

p-value ≤. 01,

p-value ≤ .001

Depressive Symptoms: Score ≥ 4 on the 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire

Elevated Stress: Score ≥ 5 on the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Model 1 adjusted for socio-demographics

Model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus use of antidepressant medications

All models for SBP and DBP additionally adjusted for use of anti-hypertensive medications.

For all models Differences in LS-means

Additional analyses (Table 3) included previously-defined clinical (i.e., cut-off score) indicators of metabolic dysfunction. Across all BMI groups, there were increases in the prevalence of larger WC (>102 cm for men or >88 cm for women) and high CRP (≥3 mg/dL) when depressive symptoms or stress were elevated. For normal BMI and overweight groups, there were increases in the prevalence of low HDL (<1.04 mmol/L for men or <1.3 mmol/L for women) when depressive symptoms or stress were elevated. When depressive symptoms and elevated stress were both present, increases in the prevalence of high LDL (≥4.1 mmol/L) was observed in the normal BMI group only, whereas increases in the prevalence of high triglycerides (≥1.7 mmol/L) were observed in the obesity group only (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted association of depressive symptoms and perceived stress with individual components of metabolic health

| Normal (BMI=18.5–24.9 kg/m2), n=5587 | Overweight (BMI=25–29.9 kg/m2), n=7961 | Obesity (BMI≥30, kg/m2), n=6764 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress |

No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress |

No Depressive Symptoms, No Stress |

Depressive Symptoms only or Elevated Stress only |

Depressive Symptoms AND Elevated Stress |

|||||||

| (n =3894) | (n=1343) | (n =350) | (n =5810) | (n=1714) | (n = 437) | (n = 4426) | (n=1759) | (n = 579) | |||||||

| n | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p-value | n | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p-value | n | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | p-value | |

|

Waist circumference >102 (men) or > 88 cm (women) |

5587 | 173 (4.4) | 74 (5.5) | 26 (7.4) | 0.02 | 7942 | 1123 (19.4) | 492 (28.8) | 161 (36.9) | <.001 | 6733 | 2612 (59.3) | 1262 (72.2) | 451 (78.2) | <.001 |

| Glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L | 5587 | 518 (13.3) | 184 (13.7) | 53 (15.1) | 0.61 | 7695 | 1304 (23.2) | 394 (23.7) | 103 (24.6) | 0.75 | 6467 | 1418 (33.4) | 557 (33.4) | 193 (34.6) | 0.86 |

| Hs-CRP ≥ 3 mg/L | 5262 | 867 (23.6) | 320 (23.8) | 120 (35.7) | <.001 | 7541 | 1731 (31.4) | 586 (36.1) | 175 (42.8) | <.001 | 6324 | 2192 (52.8) | 928 (57.0) | 340 (61.9) | <.001 |

| HDL < 1.04 (men) | 5587 | 925 (23.8) | 340 (25.3) | 96 (27.4) | 0.02 | 7657 | 1776 (31.8) | 562 (34.0) | 157 (37.7) | 0.02 | 6452 | 1779 (42.0) | 687 (41.4) | 253 (45.6) | 0.21 |

| or < 1.3 mmol/L (women) | |||||||||||||||

| LDL ≥ 4.1 mmol/L | 5302 | 353 (9.5) | 113 (9.0) | 45 (13.4) | 0.05 | 7572 | 611 (11.1) | 195 (11.9) | 55 (13.5) | 0.23 | 6381 | 476 (11.4) | 216 (13.2) | 70 (12.7) | 0.14 |

| Triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L | 5385 | 603 (16.0) | 218 (17.0) | 66 (19.4) | 0.23 | 7695 | 1491 (26.5) | 419 (25.3) | 123 (29.4) | 0.21 | 6467 | 1335 (31.5) | 465 (27.9) | 179 (32.1) | 0.02 |

| Elevated BP ( SBP ≥ 130 or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg) | 5587 | 1283 (33.0) | 422 (31.4) | 127 (36.3) | 0.21 | 7958 | 2380 (41.0) | 685 (40.0) | 183 (41.9) | 0.7 | 6755 | 2231 (50.5) | 866 (49.3) | 274 (47.3) | 0.31 |

Depressive Symptoms: Score ≥ 4 on the 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire

Elevated Stress: Score ≥ 5 on the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

9-Category Approach.

Tables 4, 5, and 6 display the results of the GLM analyses examining associations between combinations of low, moderate, and high levels of depressive symptoms and stress and the metabolic outcomes. In unadjusted models, moderate to high stress levels in the absence of high depression levels were associated with lower WC in the normal BMI and obesity groups. However, these associations were attenuated with the addition of covariates to the models. Alternatively, in unadjusted models in the overweight group, moderate to high levels of stress across depressive symptom levels were associated with lower WC. Most of these associations were attenuated when covariates were added to the models, except for individuals in the overweight group who reported combined stress and depressive symptoms. These individuals had higher WC in Model 1 (with the addition of sociodemographics to the model) but the association was attenuated in Model 2 when health behaviors were added to the model.

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted means for the association of depressive symptoms and perceived stress across levels with metabolic health outcomes among adults with normal BMI in REGARDS (cross-sectional baseline comparisons).

| Depression level | Low | Moderate | High | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress level | Low (N=1629, 29.2%) |

Moderate (N=1324, 23.7%) |

High (N=592, 10.6%) |

Low (N=348, 6.2%) |

Moderate (N=593, 10.6%) |

High (N=593,10.6%) |

Low (N=48, 1.0%) |

Moderate (N=110, 2.0%) |

High (N=350, 6.3%) |

| Waist Circumference, cm | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 82.6 (82.1, 83.1) | 81.5 (80.9, 82.1) | 80.2 (79.3, 81.0) | 82.3 (81.2, 83.4) | 80.6 (79.7, 81.4) | 80.9 (80.1, 81.8) | 80.8 (77.9, 83.8) | 79.9 (77.9, 81.8) | 80.8 (79.7, 81.9) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −1.1 (−2.3, 0.1) | −2.4 (−4.0, −0.9)*** | −0.3 (−2.2, 1.6) | −2.0 (−3.6, −0.5)** | −1.7 (−3.2, −0.1)* | −1.7 (−6.5, 3.0) | −2.7 (−5.9, 0.5) | −1.8 (−3.7, 0.1) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.8) | −0.4 (−1.7, 0.9) | 0.8 (−0.8, 2.5) | −0.3 (−1.6, 1.1) | 0.1 (−1.2, 1.4) | −0.7 (−4.8, 3.3) | −0.7 (−3.4, 2.0) | 0.3 (−1.4, 2.0) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.3 (−1.5, 0.9) | −0.5 (−2.1, 1.1) | 0.4 (−1.5, 2.3) | −0.5 (−2.1, 1.0) | −0.1 (−1.7, 1.5) | −0.6 (−5.6, 4.4) | −1.3 (−4.6, 1.9) | −0.0 (−2.1, 2.1) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.3 (−1.5, 0.9) | −0.6 (−2.2, 1.0) | 0.3 (−1.6, 2.2) | −0.6 (−2.2, 1.0) | −0.2 (−1.9, 1.4) | −0.7 (−5.7, 4.2) | −1.6 (−4.9, 1.7) | −0.3 (−2.4, 1.8) |

| Fasting Serum Glucose, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 5.00 (4.97, 5.02) | 4.98 (4.95, 5.01) | 4.96 (4.91, 5.01) | 5.00 (4.94, 5.06) | 4.92 (4.87, 4.96) | 5.02 (4.97, 5.07) | 5.05 (4.88, 5.21) | 5.04 (4.94, 5.15) | 5.03 (4.97, 5.09) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.05) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.11) | −0.08 (−0.16, 0.01) | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.11) | 0.05 (−0.21, 0.31) | 0.05 (−0.13, 0.23) | 0.03 (−0.07, 0.14) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.10, 0.07) | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.12) | −0.06 (−0.14, 0.03) | 0.04 (−0.05, 0.13) | 0.06 (−0.20, 0.31) | 0.08 (−0.10, 0.25) | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.09) | −0.07 (−0.16, 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.09) | 0.07 (−0.22, 0.37) | 0.05 (−0.15, 0.25) | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.17) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) | −0.03 (−0.15, 0.09) | −0.07 (−0.17, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.09) | 0.07 (−0.23, 0.37) | 0.05 (−0.16, 0.25) | 0.03 (−0.10, 0.16) |

| Log transformed High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, mg/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.26 (0.20, 0.32) | 0.23 (0.16, 0.29) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.46) | 0.50 (0.37, 0.63) | 0.29 (0.19, 0.38) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.53) | 0.40 (0.05, 0.75) | 0.34 (0.11, 0.58) | 0.67 (0.55, 0.80) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.04 (−0.18, 0.11) | 0.10 (−0.08, 0.28) | 0.24 (0.02, 0.46)* | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.21) | 0.17 (−0.01, 0.35) | 0.13 (−0.43, 0.70) | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.46) | 0.41 (0.19, 0.63)*** |

| Model 1 † | ref | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.12) | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.24) | 0.17 (−0.05, 0.39) | −0.02 (−0.19, 0.16) | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.26) | 0.07 (−0.48, 0.62) | 0.02 (−0.35, 0.39) | 0.29 (0.06, 0.51)** |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.01 (−0.16, 0.13) | 0.05 (−0.14, 0.25) | 0.08 (−0.15, 0.32) | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.13) | −0.06 (−0.27, 0.14) | −0.06 (−0.69, 0.57) | 0.00 (−0.41, 0.41) | 0.09 (−0.17, 0.35) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.13) | 0.03 (−0.16, 0.23) | 0.07 (−0.17, 0.30) | −0.08 (−0.27, 0.12) | −0.09 (−0.29, 0.12) | −0.08 (−0.71, 0.55) | −0.05 (−0.46, 0.36) | 0.04 (−0.22, 0.30) |

| High-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 1.49 (1.47, 1.52) | 1.52 (1.50, 1.55) | 1.55 (1.51, 1.59) | 1.52 (1.47, 1.57) | 1.55 (1.52, 1.59) | 1.54 (1.50, 1.58) | 1.51 (1.37, 1.65) | 1.50 (1.41, 1.59) | 1.53 (1.48, 1.58) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.08) | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.13) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.11) | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.13) | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.20, 0.24) | 0.01 (−0.14, 0.15) | 0.04 (−0.05, 0.12) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.07) | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | 0.01 (−0.20, 0.21) | −0.04 (−0.18, 0.09) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.08) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.00 (−0.08, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.10, 0.08) | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | −0.03 (−0.26, 0.21) | −0.03 (−0.19, 0.12) | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.00 (−0.08, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.10, 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | −0.03 (−0.26, 0.21) | −0.03 (−0.19, 0.13) | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 2.95 (2.91, 2.99) | 2.97 (2.93, 3.02) | 2.96 (2.88, 3.03) | 3.00 (2.90, 3.09) | 2.97 (2.90, 3.04) | 2.99 (2.92, 3.06) | 2.87 (2.61, 3.14) | 2.97 (2.80, 3.14) | 3.01 (2.91, 3.10) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.13) | 0.01 (−0.13, 0.14) | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.21) | 0.02 (−0.11, 0.16) | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.17) | −0.08 (−0.50, 0.34) | 0.02 (−0.25, 0.30) | 0.06 (−0.11, 0.22) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.12) | −0.02 (−0.15, 0.11) | 0.03 (−0.13, 0.20) | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.14) | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.14) | −0.09 (−0.51, 0.33) | −0.01 (−0.29, 0.26) | −0.01 (−0.18, 0.16) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.18, 0.13) | −0.01 (−0.20, 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.16, 0.14) | 0.03 (−0.13, 0.19) | −0.04 (−0.52, 0.45) | 0.07 (−0.25, 0.38) | 0.06 (−0.14, 0.26) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.18, 0.13) | −0.01 (−0.19, 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.16, 0.14) | 0.03 (−0.13, 0.19) | −0.04 (−0.52, 0.45) | 0.07 (−0.25, 0.39) | 0.06 (−0.14, 0.27) |

| Log transformed Triglycerides, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.0518 (0.0516, 0.0521) | 0.0514 (0.0511, 0.0517) | 0.0514 (0.0510, 0.0518) | 0.0525 (0.0519, 0.0530) | 0.0515 (0.0511, 0.0520) | 0.0522 (0.0518, 0.0526) | 0.0503 (0.0489, 0.0518) | 0.0518 (0.0508, 0.0528) | 0.0522 (0.0517, 0.0528) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.0004 (−0.0010, 0.0002) | −0.0004 (−0.0012, 0.0004) | 0.0006 (−0.0003, 0.0016) | −0.0003 (−0.0011, 0.0005) | 0.0004 (−0.0004, 0.0012) | −0.0015 (−0.0039, 0.0009) | 0.0000 (−0.0017, 0.0016) | 0.0004 (−0.0005, 0.0014) |

| Model 1 † | ref | −0.0004 (−0.0010, 0.0002) | −0.0004 (−0.0012, 0.0003) | 0.0005 (−0.0004, 0.0015) | −0.0004 (−0.0011, 0.0004) | 0.0003 (−0.0004, 0.0011) | −0.0016 (−0.0039, 0.0007) | −0.0003 (−0.0019, 0.0013) | 0.0003 (−0.0006, 0.0013) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.0004 (−0.0011, 0.0003) | −0.0005 (−0.0014, 0.0004) | 0.0004 (−0.0007, 0.0015) | −0.0007 (−0.0015, 0.0002) | 0.0001 (−0.0008, 0.0010) | −0.0006 (−0.0033, 0.0021) | −0.0003 (−0.0021, 0.0016) | 0.0002 (−0.0009, 0.0014) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.0004 (−0.0011, 0.0002) | −0.0006 (−0.0015, 0.0003) | 0.0003 (−0.0007, 0.0014) | −0.0007 (−0.0016, 0.0002) | 0.0000 (−0.0010, 0.0009) | −0.0007 (−0.0034, 0.0020) | −0.0005 (−0.0023, 0.0014) | 0.0000 (−0.0012, 0.0012) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 123.8 (123, 124.7) | 122.1 (121.2, 123) | 121.5 ( 120.1, 122.9) | 124.0 ( 122.2, 125.8) | 123.0 (121.6, 124.3) | 122.4 (121.0, 123.7) | 122.0 (117.2, 126.8) | 123.0 (119.8, 126.2) | 124.0(122.2, 125.8) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −1.7 (−3.7, 0.2) | −2.3 (−4.9, 0.2) | 0.1 (−3.0, 3.2) | −0.9 (−3.4, 1.6) | −1.5 (−4.0, 1.1) | −1.9 (−9.5, 5.8) | −0.8 (−6.0, 4.3) | 0.2 (−2.9, 3.3) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.8 (−2.6, 1.0) | −1.7 (−4.0, 0.7) | −0.7 (−3.5, 2.2) | −1.0 (−3.3, 1.4) | −1.9 (−4.3, 0.4) | −2.0 (−9.0, 5.1) | −1.1 (−5.8, 3.7) | −0.4 (−3.3, 2.6) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.5 (−2.5, 1.4) | −1.5 (−4.1, 1.1) | −1.3 (−4.4, 1.9) | −1.2 (−3.8, 1.4) | −1.9 (−4.6, 0.8) | −0.5 (−8.7, 7.7) | −1.6 (−7.0, 3.9) | −1.5 (−5.0, 2.0) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.5 (−2.5, 1.4) | −1.4 (−4.1, 1.2) | −1.2 (−4.4, 2.0) | −1.1 (−3.7, 1.5) | −1.8 (−4.5, 1.0) | −0.4 (−8.7, 7.8) | −1.4 (−6.8, 4.1) | −1.3 (−4.8, 2.2) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 74.4 (73.9, 74.8) | 73.8 (73.3, 74.3) | 73.6 (72.8, 74.3) | 73.6 (72.8, 74.3) | 73.9 (73.2, 74.7) | 73.6 (72.8, 74.3) | 73.2 (70.5, 75.8) | 73.0 (71.2, 74.7) | 74.8 (73.9, 75.8) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −0.6 (−1.6, 0.5) | −0.8 (−2.2, 0.6) | −0.8 (−2.5, 0.9) | −0.5 (−1.8, 0.9) | −0.8 (−2.2, 0.5) | −1.2 (−5.5, 3.0) | −1.4 (−4.3, 1.4) | 0.4 (−1.3, 2.1) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.3 (−1.4, 0.7) | −0.6 (−2.0, 0.8) | −1.0 (−2.6, 0.7) | −0.4 (−1.8, 0.9) | −1.1 (−2.5, 0.3) | −1.5 (−5.6, 2.6) | −1.6 (−4.4, 1.1) | −0.4 (−2.1, 1.3) |

| Model 2 † | ref | 0.0 (−1.1, 1.2) | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.7) | −1.3 (−3.1, 0.6) | −0.3 (−1.8, 1.2) | −1.5 (−3.1, 0.1) | −0.8 (−5.6, 4.0) | −1.7 (−4.9, 1.5) | −1.0 (−3.1, 1.0) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.0 (−1.1, 1.2) | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.7) | −1.3 (−3.1, 0.6) | −0.3 (−1.8, 1.2) | −1.5 (−3.1, 0.1) | −0.8 (−5.6, 4.1) | −1.6 (−4.9, 1.6) | −1.0 (−3.1, 1.0) |

p-value <. 05,

p-value ≤. 01,

p-value ≤ .001

p-value <.05 global test for equality of all category means

Depressive Symptoms: Score ≥ 4 on the 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire

Elevated Stress: Score ≥ 5 on the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Model 1 adjusted for socio-demographics

Model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus use of antidepressant medications

All models for SBP and DBP additionally adjusted for use of anti-hypertensive medications.

For all models Difference in LS-means

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted means for the association of depressive symptoms and perceived stress across levels with metabolic health outcomes among adults with overweight BMI in REGARDS (cross-sectional baseline comparisons).

| Depression level | Low | Moderate | High | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress level | Low (N=2634, 33.1%) |

Moderate (N=1857, 23.3%) |

High (N=726, 9.1%) |

Low (N=514, 6.5%) |

Moderate (N=805, 10.1%) |

High (N=764, 9.6%) |

Low (N=75, 0.9%) |

Moderate (N=149, 1.9%) |

High (N=350, 5.5%) |

| Waist Circumference, cm | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 93.3 (92.9, 93.6) | 92.2 (91.8, 92.6) | 92.0 (91.4, 92.7) | 92.7 (91.9, 93.5) | 91.3 (90.7, 92.0) | 91.5 (90.9, 92.2) | 93.2 (91.1, 95.3) | 91.2 (89.7, 92.7) | 91.7 (90.8, 92.6) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −1.1 (−1.9, −0.2)** | −1.2 (−2.4, 0.0)* | −0.5 (−1.9, 0.8) | −1.9 (−3.1, −0.8)*** | −1.7 (−2.9, −0.5)*** | −0.1 (−3.4, 3.3) | −2.0 (−4.4, 0.4) | −1.5 (−3.0, −0.1)* |

| Model 1 † | ref | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.6) | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.6) | 0.3 (−0.9, 1.5) | −0.1 (−1.1, 0.9) | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) | 0.7 (−2.1, 3.6) | 0.2 (−1.8, 2.3) | 1.6 (0.3, 2.9)** |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.0 (−0.9, 0.8) | 0.4 (−0.8, 1.6) | 0.5 (−0.8, 1.9) | −0.4 (−1.6, 0.7) | 0.5 (−0.7, 1.8) | 0.2 (−3.0, 3.4) | 0.4 (−2.1, 2.9) | 1.0 (−0.6, 2.6) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.1 (−0.9, 0.8) | 0.4 (−0.8, 1.6) | 0.5 (−0.8, 1.8) | −0.5 (−1.6, 0.7) | 0.5 (−0.7, 1.7) | 0.1 (−3.1, 3.3) | 0.3 (−2.2, 2.8) | 0.8 (−0.8, 2.4) |

| Fasting Serum Glucose, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 5.18 (5.15, 5.20) | 5.13 (5.11, 5.16) | 5.13 (5.08, 5.17) | 5.18 (5.13, 5.23) | 5.14 (5.10, 5.18) | 5.16 (5.11, 5.20) | 5.33 (5.20, 5.47) | 5.09 (5.00, 5.19) | 5.16 (5.11, 5.22) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.01) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.06) | 0.16 (−0.06, 0.37) | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.10) | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.06) | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.08) | 0.15 (−0.06, 0.37) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.09) | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.12) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.07) | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.09) | 0.14 (−0.11, 0.38) | −0.10 (−0.29, 0.08) | −0.02 (−0.14, 0.09) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.07) | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.09) | 0.14 (−0.11, 0.38) | −0.10 (−0.29, 0.08) | −0.02 (−0.14, 0.10) |

| Log transformed High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, mg/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.58 (0.54, 0.63) | 0.55 (0.50, 0.60) | 0.66 (0.58, 0.74) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.76) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.75) | 0.75 (0.68, 0.83) | 0.69 (0.44, 0.94) | 0.81 (0.63, 0.99) | 0.89 (0.78, 0.99) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.04 (−0.14, 0.07) | 0.07 (−0.07, 0.22) | 0.08 (−0.09, 0.25) | 0.09 (−0.05, 0.23) | 0.17 (0.03, 0.31)** | 0.11 (−0.30, 0.51) | 0.23 (−0.07, 0.52) | 0.30 (0.12, 0.48)*** |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.14) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.18) | 0.00 (−0.14, 0.14) | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) | 0.01 (−0.39, 0.40) | 0.09 (−0.20, 0.37) | 0.12 (−0.06, 0.30) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.07) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.11) | −0.03 (−0.21, 0.15) | −0.01 (−0.16, 0.15) | −0.03 (−0.19, 0.14) | −0.08 (−0.52, 0.35) | 0.07 (−0.27, 0.41) | −0.02 (−0.23, 0.20) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.05 (−0.16, 0.07) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.10) | −0.04 (−0.22, 0.15) | −0.02 (−0.17, 0.14) | −0.04 (−0.20, 0.13) | −0.09 (−0.53, 0.34) | 0.05 (−0.29, 0.39) | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.17) |

| High-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 1.31 (1.30, 1.33) | 1.34 (1.32, 1.36) | 1.35 (1.32, 1.38) | 1.35 (1.32, 1.39) | 1.39 (1.36, 1.42) | 1.36 (1.33, 1.39) | 1.41 (1.32, 1.50) | 1.40 (1.33, 1.46) | 1.35 (1.31, 1.39) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.01) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.04)*** | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.06) | 0.16 (−0.06, 0.37) | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) |

| Model 1 † | ref | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.07) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.07 (−0.06, 0.21) | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.11) | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.07 (−0.08, 0.22) | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.18) | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.05) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.07 (−0.08, 0.22) | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.17) | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 3.05 (3.01, 3.08) | 3.05 (3.01, 3.09) | 3.08 (3.01, 3.15) | 3.03 (2.95, 3.11) | 3.10 (3.03, 3.16) | 3.10 (3.04, 3.17) | 2.92 (2.71, 3.12) | 3.00 (2.85, 3.14) | 3.19 (3.10, 3.28) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | 0.00 (−0.08, 0.09) | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.15) | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.12) | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.17) | −0.13 (−0.46, 0.20) | −0.05 (−0.29, 0.19) | 0.14 (0.00, 0.29) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.10) | −0.03 (−0.17, 0.10) | 0.00 (−0.11, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.13, 0.10) | −0.15 (−0.48, 0.17) | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.13, 0.17) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.03 (−0.12, 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.11) | −0.06 (−0.21, 0.10) | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.13) | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.13) | −0.28 (−0.64, 0.09) | −0.12 (−0.40, 0.16) | −0.07 (−0.25, 0.11) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.03 (−0.12, 0.07) | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.11) | −0.05 (−0.21, 0.10) | 0.01 (−0.12, 0.14) | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.13) | −0.27 (−0.64, 0.09) | −0.11 (−0.40, 0.17) | −0.06 (−0.24, 0.12) |

| Log transformed Triglycerides, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.0535 (0.0532, 0.0537) | 0.0533 (0.0531, 0.0536) | 0.0530 (0.0526, 0.0534) | 0.0536 (0.0531, 0.0541) | 0.0535 (0.0531, 0.0538) | 0.0534 (0.0530, 0.0538) | 0.0535 (0.0522, 0.0548) | 0.0535 (0.0526, 0.0544) | 0.0539 (0.0534, 0.0545) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0004) | −0.0004 (−0.0012, 0.0003) | 0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0010) | 0.0000 (−0.0007, 0.0007) | −0.0001 (−0.0008, 0.0006) | 0.0001 (−0.0020, 0.0021) | 0.0001 (−0.0014, 0.0015) | 0.0005 (−0.0004, 0.0014) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0004) | −0.0003 (−0.0011, 0.0004) | 0.0002 (−0.0006, 0.0010) | 0.0001 (−0.0006, 0.0008) | 0.0002 (−0.0005, 0.0009) | 0.0000 (−0.0020, 0.0019) | 0.0001 (−0.0013, 0.0016) | 0.0005 (−0.0004, 0.0014) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0005) | −0.0002 (−0.0010, 0.0007) | 0.0000 (−0.0009, 0.0010) | 0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0009) | 0.0001 (−0.0008, 0.0009) | −0.0003 (−0.0026, 0.0019) | 0.0000 (−0.0017, 0.0017) | 0.0003 (−0.0008, 0.0013) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0005) | −0.0002 (−0.0010, 0.0007) | 0.0000 (−0.0009, 0.0009) | 0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0008) | 0.0001 (−0.0008, 0.0009) | −0.0004 (−0.0026, 0.0019) | −0.0001 (−0.0018, 0.0016) | 0.0002 (−0.0009, 0.0013) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 126.9 (126.3, 127.5) | 125.6 (124.9, 126.3) | 125.4 (124.3, 126.6) | 127.9 (126.6, 129.3) | 126.1 (125.0, 127.2) | 126.2 (125.1, 127.3) | 126.7 (123.1, 130.3) | 125.9 (123.4, 128.4) | 127.1 (125.6, 128.6) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −1.4 (−2.8, 0.1) | −1.5 (−3.6, 0.5) | 1.0 (−1.4, 3.4) | −0.8 (−2.8, 1.2) | −0.7 (−2.8, 1.3) | −0.2 (−6.0, 5.5) | −1.0 (−5.1, 3.1) | 0.2 (−2.3, 2.7) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.8 (−2.2, 0.6) | −1.3 (−3.3, 0.7) | 0.2 (−2.0, 2.5) | −0.7 (−2.6, 1.2) | −1.0 (−3.0, 0.9) | −1.1 (−6.5, 4.3) | −1.1 (−5.0, 2.9) | 0.0 (−2.4, 2.5) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.5 (−2.1, 1.1) | −0.9 (−3.2, 1.3) | −0.5 (−3.1, 2.0) | −0.1 (−2.2, 2.1) | −1.3 (−3.6, 1.0) | 0.2 (−5.9, 6.3) | −1.1 (−5.7, 3.6) | −0.9 (−3.9, 2.1) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.5 (−2.1, 1.1) | −0.9 (−3.2, 1.3) | −0.5 (−3.0, 2.0) | 0.0 (−2.1, 2.2) | −1.2 (−3.5, 1.1) | 0.3 (−5.8, 6.4) | −0.8 (−5.5, 3.8) | −0.6 (−3.6, 2.4) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 76.5 (76.2, 76.8) | 76.3 (75.9, 76.7) | 75.9 (75.3, 76.6) | 76.9 (76.1, 77.7) | 76.2 (75.6, 76.9) | 76.7 (76.0, 77.3) | 75.6 (73.6, 77.7) | 76.1 (74.7, 77.6) | 77.2 (76.4, 78.1) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | −0.2 (−1.1, 0.6) | −0.6 (−1.8, 0.6) | 0.4 (−1.0, 1.7) | −0.3 (−1.4, 0.9) | 0.2 (−1.0, 1.3) | −0.9 (−4.2, 2.4) | −0.4 (−2.7, 2.0) | 0.7 (−0.7, 2.2) | −0.2 (−1.1, 0.6) |

| Model 1 | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.6) | −0.6 (−1.8, 0.6) | 0.4 (−0.9, 1.7) | −0.2 (−1.4, 0.9) | −0.0 (−1.2, 1.1) | −0.8 (−4.0, 2.4) | −0.3 (−2.7, 2.0) | −0.0 (−1.5, 1.5) | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.6) |

| Model 2 | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.7) | −0.7 (−2.1, 0.6) | −0.1 (−1.6, 1.4) | −0.1 (−1.4, 1.2) | −0.9 (−2.3, 0.5) | −0.8 (−4.4, 2.8) | 0.1 (−2.7, 2.8) | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.2) | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.7) |

| Model 3 | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.7) | −0.7 (−2.1, 0.6) | −0.0 (−1.6, 1.5) | −0.1 (−1.4, 1.2) | −0.9 (−2.3, 0.5) | −0.8 (−4.4, 2.9) | 0.1 (−2.7, 2.9) | −0.5 (−2.3, 1.3) | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.7) |

p-value <. 05,

p-value ≤. 01,

p-value ≤ .001

p-value <.05 global test for equality of all category means

Depressive Symptoms: Score ≥ 4 on the 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire

Elevated Stress: Score ≥ 5 on the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Model 1 adjusted for socio-demographics

Model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus use of antidepressant medications

All models for SBP and DBP additionally adjusted for use of anti-hypertensive medications.

For all models Difference in LS-means

Table 6.

Crude and adjusted means for the association of depressive symptoms and perceived stress across levels with metabolic health outcomes among adults with obese BMI in REGARDS (cross-sectional baseline comparisons)

| Depression level | Low | Moderate | High | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress level | Low (N=1806, 26.7%) |

Moderate (N=1429, 21.1%) |

High (N=691, 10.2%) |

Low (N=440, 6.5%) |

Moderate (N=751, 11.1%) |

High (N=847, 12.5%) |

Low (N=70, 1.0%) |

Moderate (N=151, 2.2%) |

High (N=579, 8.6%) |

| Waist Circumference, cm | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 106.6 (106.1, 107.2) | 105.1 (104.4, 105.7) | 105.7 (104.8, 106.6) | 104.7 (103.5, 105.8) | 105.0 (104.1, 105.9) | 105.8 (105, 106.6) | 105.5 (102.6, 108.4) | 105.3 (103.3, 107.3) | 106.6 (105.6, 107.6) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −1.6 (−2.9, −0.2)* | −0.9 (−2.6, 0.8) | −2.0 (−4.0, 0.1) | −1.6 (−3.3, 0.0) | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.8) | −1.1 (−5.8, 3.6) | −1.4 (−4.6, 1.9) | −0.1 (−1.9, 1.8) |

| Model 1 † | ref | −1.0 (−2.3, 0.3) | 0.0 (−1.7, 1.6) | −1.0 (−3.0, 0.9) | −0.6 (−2.2, 1.0) | 0.6 (−1.0, 2.1) | 0.2 (−4.2, 4.7) | 0.4 (−2.7, 3.5) | 1.2 (−0.6, 3.1) |

| Model 2 † | ref | −1.1 (−2.6, 0.3) | 0.3 (−1.7, 2.3) | −0.8 (−3.0, 1.5) | −0.4 (−2.2, 1.4) | 0.6 (−1.2, 2.5) | 0.5 (−5.0, 6.1) | 1.0 (−2.7, 4.7) | 1.0 (−1.2, 3.2) |

| Model 3 | ref | −1.1 (−2.6, 0.3) | 0.3 (−1.7, 2.3) | −0.8 (−3.0, 1.4) | −0.5 (−2.3, 1.3) | 0.5 (−1.4, 2.4) | 0.4 (−5.1, 5.9) | 0.9 (−2.8, 4.6) | 0.8 (−1.5, 3.0) |

| Fasting Serum Glucose, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 5.30 (5.27, 5.33) | 5.30 (5.26, 5.33) | 5.31 (5.26, 5.36) | 5.31 (5.25, 5.37) | 5.30 (5.25, 5.35) | 5.31 (5.27, 5.35) | 5.29 (5.13, 5.45) | 5.20 (5.09, 5.30) | 5.32 (5.26, 5.37) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.12) | 0.00 (−0.08, 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.10) | −0.01 (−0.26, 0.25) | −0.10 (−0.27, 0.07) | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.14) | 0.02 (−0.07, 0.11) | 0.04 (−0.05, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.23, 0.27) | −0.07 (−0.25, 0.10) | 0.05 (−0.05, 0.15) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.12) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.10) | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.30, 0.34) | −0.06 (−0.27, 0.15) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.11) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.12) | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.10) | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.30, 0.34) | −0.06 (−0.27, 0.15) | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.11) |

| Log transformed High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, mg/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) | 1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.27 (1.17, 1.37) | 1.22 (1.14, 1.29) | 1.29 (1.22, 1.36) | 1.05 (0.78, 1.31) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.36) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.46) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.11) | 0.11 (−0.04, 0.26) | 0.13 (−0.05, 0.31) | 0.07 (−0.07, 0.22) | 0.15 (0.01, 0.29)* | −0.10 (−0.52, 0.33) | 0.05 (−0.24, 0.33) | 0.23 (0.07, 0.39)*** |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.06 (−0.18, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.14, 0.15) | 0.03 (−0.14, 0.20) | −0.04 (−0.18, 0.10) | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.11) | −0.24 (−0.65, 0.17) | −0.16 (−0.43, 0.12) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.17) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.06 (−0.19, 0.08) | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.20) | 0.05 (−0.15, 0.25) | −0.05 (−0.21, 0.12) | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.13) | −0.27 (−0.78, 0.24) | −0.13 (−0.46, 0.20) | −0.02 (−0.21, 0.18) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.06 (−0.19, 0.08) | 0.01 (−0.16, 0.19) | 0.05 (−0.15, 0.25) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.11) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.11) | −0.29 (−0.80, 0.22) | −0.15 (−0.48, 0.19) | −0.04 (−0.24, 0.15) |

| High-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 1.27 (1.25, 1.29) | 1.29 (1.27, 1.31) | 1.29 (1.26, 1.32) | 1.30 (1.27, 1.34) | 1.30 (1.27, 1.33) | 1.33 (1.30, 1.36) | 1.37 (1.28, 1.46) | 1.43 (1.36, 1.49) | 1.32 (1.29, 1.35) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.10) | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11)** | 0.10 (−0.05, 0.25) | 0.16 (0.05, 0.26)*** | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.17) | 0.07 (−0.02, 0.16) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.10 (−0.07, 0.27) | 0.07 (−0.04, 0.17) | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.05) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.10 (−0.07, 0.26) | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.17) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.05) |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 3.03 (2.99, 3.07) | 3.07 (3.02, 3.12) | 3.09 (3.02, 3.16) | 3.06 (2.97, 3.14) | 3.12 (3.05, 3.18) | 3.15 (3.09, 3.21) | 2.95 (2.73, 3.17) | 3.15 (3.00, 3.29) | 3.13 (3.05, 3.20) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean † | ref | 0.04 (−0.06, 0.14) | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.18) | 0.03 (−0.12, 0.18) | 0.09 (−0.04, 0.21) | 0.12 (0.00, 0.24)* | −0.08 (−0.44, 0.27) | 0.11 (−0.13, 0.35) | 0.10 (−0.04, 0.23) |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.14) | 0.00 (−0.15, 0.15) | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | −0.11 (−0.46, 0.25) | 0.04 (−0.20, 0.28) | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.14) |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.12) | 0.03 (−0.12, 0.19) | 0.00 (−0.18, 0.17) | 0.02 (−0.13, 0.16) | 0.03 (−0.12, 0.18) | −0.12 (−0.56, 0.32) | −0.02 (−0.32, 0.27) | 0.02 (−0.15, 0.20) |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.00 (−0.11, 0.12) | 0.04 (−0.11, 0.20) | 0.00 (−0.18, 0.17) | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.19) | −0.10 (−0.54, 0.34) | 0.00 (−0.30, 0.29) | 0.06 (−0.11, 0.23) |

| Log transformed Triglycerides, mmol/L | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 0.0543 (0.0541, 0.0546) | 0.0540 (0.0537, 0.0543) | 0.0541 (0.0537, 0.0545) | 0.0542 (0.0537, 0.0547) | 0.0543 (0.0539, 0.0547) | 0.0536 (0.0532, 0.0540) | 0.0541 (0.0527, 0.0554) | 0.0536 (0.0527, 0.0545) | 0.0541 (0.0536, 0.0545) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −0.0003 (−0.0009, 0.0003) | −0.0002 (−0.0010, 0.0006) | −0.0001 (−0.0010, 0.0008) | −0.0001 (−0.0008, 0.0007) | −0.0007 (−0.0014, 0.0000)* | −0.0003 (−0.0024, 0.0019) | −0.0007 (−0.0022, 0.0008) | −0.0002 (−0.0011, 0.0006) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.0003 (−0.0009, 0.0003) | 0.0001 (−0.0006, 0.0008) | 0.0001 (−0.0007, 0.0010) | 0.0002 (−0.0005, 0.0009) | −0.0003 (−0.0009, 0.0004) | −0.0001 (−0.0021, 0.0019) | −0.0002 (−0.0016, 0.0011) | 0.0002 (−0.0006, 0.0010) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.0002 (−0.0008, 0.0005) | 0.0003 (−0.0006, 0.0012) | 0.0001 (−0.0009, 0.0011) | 0.0002 (−0.0006, 0.0010) | −0.0003 (−0.0011, 0.0005) | −0.0006 (−0.0031, 0.0020) | 0.0003 (−0.0013, 0.0020) | 0.0003 (−0.0007, 0.0012) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.0002 (−0.0008, 0.0005) | 0.0003 (−0.0006, 0.0012) | 0.0001 (−0.0009, 0.0011) | 0.0002 (−0.0006, 0.0010) | −0.0003 (−0.0012, 0.0005) | −0.0006 (−0.0031, 0.0019) | 0.0003 (−0.0013, 0.0020) | 0.0002 (−0.0008, 0.0012) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 130.4 (129.6, 131.1) | 128.8 (128.0, 129.6) | 129.1 (127.9, 130.3) | 129.9 (128.5, 131.4) | 129.6 (128.5, 130.7) | 129.0 (128.0, 130.1) | 128.9 (125.3, 132.6) | 131.5 (128.9, 134.0) | 128.9 (127.6, 130.2) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −1.5 (−3.3, 0.2) | −1.3 (−3.5, 0.9) | −0.4 (−3.0, 2.2) | −0.8 (−2.9, 1.4) | −1.3 (−3.4, 0.7) | −1.4 (−7.4, 4.5) | 1.1 (−3.1, 5.2) | −1.4 (−3.8, 0.9) |

| Model 1 | ref | −1.2 (−2.8, 0.5) | −1.0 (−3.2, 1.1) | −0.7 (−3.2, 1.8) | −0.7 (−2.8, 1.3) | −1.7 (−3.7, 0.4) | −2.4 (−8.2, 3.5) | 0.7 (−3.4, 4.8) | −1.9 (−4.2, 0.5) |

| Model 2 † | ref | −1.2 (−3.2, 0.7) | −2.1 (−4.6, 0.5) | −1.3 (−4.2, 1.6) | −0.7 (−3.1, 1.7) | −2.3 (−4.7, 0.2) | −2.6 (−9.8, 4.7) | 1.4 (−3.5, 6.2) | −2.4 (−5.3, 0.4) |

| Model 3 † | ref | −1.2 (−3.1, 0.7) | −2.0 (−4.6, 0.6) | −1.3 (−4.2, 1.6) | −0.5 (−2.9, 1.9) | −2.1 (−4.5, 0.4) | −2.4 (−9.6, 4.9) | 1.6 (−3.3, 6.4) | −2.1 (−5.0, 0.8) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Crude Mean (95% CI) | 79.4 (78.9, 79.8) | 78.9 (78.5, 79.4) | 78.9 (78.2, 79.6) | 79.1 (78.3, 80.0) | 79.1 (78.4, 79.8) | 79.1 (78.5, 79.7) | 77.9 (75.7, 80.1) | 80.3 (78.8, 81.8) | 79.5 (78.7, 80.3) |

| Differences (95% CI): | |||||||||

| Crude Mean | ref | −0.4 (−1.5, 0.6) | −0.4 (−1.8, 0.9) | −0.2 (−1.8, 1.3) | −0.3 (−1.5, 1.0) | −0.3 (−1.5, 1.0) | −1.5 (−5.1, 2.1) | 0.9 (−1.6, 3.4) | 0.1 (−1.3, 1.5) |

| Model 1 | ref | −0.4 (−1.4, 0.6) | −0.5 (−1.8, 0.8) | −0.2 (−1.7, 1.4) | −0.3 (−1.6, 1.0) | −0.5 (−1.7, 0.7) | −1.4 (−5.0, 2.1) | 0.9 (−1.6, 3.4) | −0.6 (−2.0, 0.9) |

| Model 2 | ref | −0.7 (−1.9, 0.5) | −0.7 (−2.3, 0.8) | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.2) | −0.2 (−1.7, 1.2) | −1.0 (−2.5, 0.5) | −1.4 (−5.8, 3.1) | 1.0 (−2.0, 4.0) | −0.6 (−2.3, 1.2) |

| Model 3 | ref | −0.7 (−1.9, 0.5) | −0.7 (−2.3, 0.9) | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.2) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.3) | −0.9 (−2.4, 0.6) | −1.2 (−5.7, 3.2) | 1.1 (−1.9, 4.0) | −0.4 (−2.2, 1.4) |

p-value <. 05,

p-value ≤. 01,

p-value ≤ .001

p-value <.05 global test for equality of all category means

Depressive Symptoms: Score ≥ 4 on the 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire

Elevated Stress: Score ≥ 5 on the 4-item version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Model 1 adjusted for socio-demographics

Model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus use of antidepressant medications

All models for SBP and DBP additionally adjusted for use of anti-hypertensive medications.

For all models Difference in LS-means

In unadjusted models, moderate to high levels of depressive symptoms with high stress were associated with higher CRP across all BMI groups. These associations are attenuated with the addition of covariates in the overweight and obesity groups, and the association with the normal BMI group also became non-significant after sociodemographics were introduced in the model. In the overweight group, moderate levels of both stress and depressive symptoms together were associated with higher levels of HDL in unadjusted analyses though this association was attenuated when covariates were added. Similarly, in the obesity group, when depressive symptoms were high and stress was moderate in combination or vice versa (i.e., high depressive symptoms-moderate stress, moderate depressive symptoms-high stress), there was an association with higher HDL and LDL in unadjusted analyses, but the associations were attenuated when covariates were included in the model.

There was generally a lack of associations between any level of perceived stress and/or depressive symptoms and fasting glucose, triglycerides, SBP, and DBP across BMI groups. In the normal BMI group, any level/combination of psychological symptoms was also unrelated to HDL and LDL, whereas only LDL was unrelated to psychological symptoms in the overweight group.

Discussion

In this cohort of adults with a diverse BMI range and without diabetes, the presence of elevated depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress were generally associated with higher WC, higher CRP, and lower HDL. The most robust and consistent associations were observed for WC, which remained significant after covariate adjustments. Additionally, CRP was also consistently associated with psychological symptoms across BMI groups. However, sociodemographic factors and health behaviors appeared to account for these relationships, suggesting that healthy lifestyle factors may attenuate the association between psychological distress and inflammation. Moreover, the aforementioned associations were generally stronger when elevations in depressive symptoms and perceived stress co-occurred compared to when only one of these psychological factors was present. The findings regarding HDL and BP differed based on analytical approach, suggesting that there may be utility in using a multi-dimensional approach to defining psychological symptoms and metabolic parameters and that each parameter/symptom may require a unique approach for interpretation. Fasting glucose, triglycerides, and LDL parameters were mostly unrelated to depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress after adjusting for sociodemographic variables.

Our results are consistent with prior research that demonstrates significant relationships between depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress and metabolic syndrome, which is a clustering of related but distinct metabolic parameters that typically includes abdominal obesity, triglycerides, blood pressure, glucose, and HDL.25 However, our results suggest that psychological stressors may have distinct associations with individual metabolic parameters and not others, and thus, examining a composite measure of metabolic health that includes all of these parameters may fail to capture some of the variability in associations. This is also consistent with previous studies that have found that individual components of metabolic health demonstrate differential associations with stress and depressive symptoms.8, 11, 13 For instance, the findings that WC were most consistently and strongly associated with psychological distress is consistent with previous literature demonstrating associations between WC, depressive symptoms27, and perceived stress28, 29. Notably, these associations remained after adjustment for sociodemographic factors, lifestyle behaviors, and antidepressant use only in the obesity group suggesting that the strength of the association between WC and psychological factors is strongest among these individuals. These findings imply that assessment and intervention efforts for obesity, and perhaps central adiposity more specifically, should include mental health components.

Furthermore, along with conventional parameters used to conceptualize metabolic syndrome, we included CRP as an additional indicator of metabolic health. CRP provides a measure of inflammation and thus is often viewed as an inflammatory biomarker. However, we have characterized CRP as a metabolic marker in the context of this study given that it may be particularly relevant for understanding metabolic dysregulation as well as related risk factors and subsequent health outcomes.26, 30 Psychological stressors may result in elevated inflammation, which also impacts metabolic parameters.31 In line with this, our data demonstrate correlations between CRP and certain metabolic parameters, as well as both perceived stress and depressive symptoms (see Supplemental Tables 2–4). While psychological symptoms were most consistently associated with higher CRP when there was high stress in combination with moderate to high depressive symptoms, lifestyle factors attenuated these associations. Thus, lifestyle factors such as healthy diet and physical activity may have a protective effect on inflammation levels in the context of psychological distress, which is consistent with previous research; however, the cross-sectional nature of the current study limits our ability to directly test this suggestion.32, 33 In addition, alternative measures of inflammation (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha; TNF-α) may contribute additional insights beyond CRP.32

The findings regarding HDL differed based on the approach to analysis, with the clearest findings suggesting that there was a consistent association across BMI groups between the presence of elevated depressive symptoms and/or perceived stress and lower HDL when using a simpler (yes-no; cut-off values) versus more complex (graded; continuous) approach to both psychological symptoms and HDL. Interestingly, BP parameters tended to be slightly lower in individuals who reported either depressive symptoms or perceived stress (only one or the other), and this association remained significant with covariate adjustment and was consistent across BMI groups. However, in general, these associations were not found when examining BP using cutoff values or viewing psychological symptoms in a more graded fashion.

This study examined the individual and combined associations of two psychological stressors with metabolic health, which has not typically been the focus of previous research.7, 11, 13 The co-occurrence of elevated depressive symptoms and elevated perceived stress was more strongly associated with several parameters of metabolic health than only one of these psychological constructs. This is consistent with another REGARDS investigation that examined the individual and combined associations of these two psychological risk factors with cardiovascular outcomes, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular-related death, among participants with and without diabetes.34 Among those with diabetes, the combination of both elevated depressive symptoms and perceived stress was associated with higher cardiovascular-related mortality than either single psychological factor alone. Therefore, including mental health care options such as cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques and stress management in the treatment plan may improve metabolic health status or prognosis for patients with/at risk for metabolic impairment who demonstrate combined stress and depressive symptoms. Moreover, past research has demonstrated that metabolic impairment and psychological symptoms uniquely predict cardiovascular mortality risk35, which underscores the importance of treating both metabolic impairment and psychological distress simultaneously when possible.

Most commonly, the associations between psychological stressors and metabolic dysfunction are conceptualized as stressors leading to impairments in metabolic health.36 If psychological stressors, including depression and perceived stress, result in metabolic dysregulation, then this could occur via several pathways. First, depressive symptoms, stress, and other psychological risk factors may produce hyperactivity of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and excess production of glucocorticoids, which can have adverse effects on a variety of metabolic processes and outcomes.37, 38

Alternatively, psychological stressors may be related to the adoption or maintenance of specific behaviors, such as smoking, inactivity, or poor dietary habits, that may have adverse effects on subsequent metabolic health.39, 40 Indeed, a previous study examining behavioral and pathophysiological contributors to CVD risk showed that behavioral factors (i.e., smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity) explained 65% of the variance in CVD events compared to 18.5% by pathophysiological factors.40 In our study, the associations of depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and most metabolic parameters were attenuated and not statistically significant after accounting for smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol intake, and diet. This is consistent with a similar study which demonstrated that psychological distress increased the risk of metabolic syndrome, but the relationship was attenuated when accounting for health behaviors.41 Together, these findings highlight the potential attenuating effect that healthy living can have on the association between psychological distress and metabolic impairment. These findings would benefit from further investigation in the form of clinical trials.