The period of transition to academic junior faculty after postgraduate training is a challenging time to maintain scholarly productivity.(1) New faculty embarking on careers as researchers or clinician-educators often have difficulty finding time to develop their individual academic niche; this is often due to competing commitments such as clinical work, administrative responsibilities, and service obligations.(2) The requirements of working in an academic medical center (university-affiliated hospital system), coupled with a lack of protected time, threaten productivity and academic success.(3)

The difficulties of simultaneously initiating research investigations, achieving grant funding, and working clinically have led to structured programs like grant review groups, funded fellowships, junior faculty development programs and writing retreats (Table 1).(1,4,5) Participation in junior faculty development programs improves retention of academic faculty and facilitates downstream academic success.(6,7) These activities are effective at pairing junior faculty with senior-level mentors, but are dependent on the commitment and availability of senior faculty with aligning academic interests.

Table 1.

Current junior faculty support systems

| Support System | Structure |

|---|---|

| Junior Faculty Development Program | Courses over one year on aspects of faculty development with personalized projects |

| Writing Retreat | Group retreats with senior faculty and structured time to write manuscripts/grants |

| Funded Fellowships | University-funded fellowships that cover salary and provide basic faculty support |

| Training Grant Review Groups | Senior faculty review of training or foundation grants from junior faculty |

At some institutions, significant barriers exist, such as limited financial support for junior faculty, few senior faculty providing mentorship, and limited senior mentors in appropriate fields of study.(8,9) In such cases, junior academicians may experience less productivity, miss opportunities for grant funding, and ultimately turn away from academic careers. Delayed mentorship for junior faculty can lead to involvement in divergent, unfocused commitments and projects that may distract from efforts to obtain protected academic time and apply for grant funding within their area of interest.

We believe that junior faculty-initiated writing and peer mentoring groups are a sustainable method to encourage productivity among new faculty. This toolbox describes how we created a self-sustaining junior faculty writing group, the Sustaining High-level Achievement by Reinforcing Each other (SHARE) writing group It also describes the benefits of peer mentorship, and guides readers in the development of their own writing group.

An example of peer mentorship success: The SHARE writing group

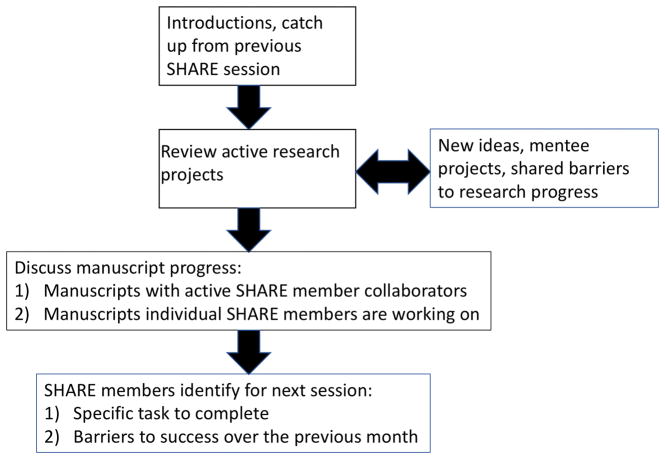

Based on the desire to create a structured writing group of peers with the common goal of developing a supportive infrastructure through the transition from trainee to junior faculty, we created the SHARE writing group. We identified key metrics of academic productivity important to ourselves and to academic advancement in general. The SHARE group met monthly and consisted of a 1–2 hour review of the past month’s progress in terms of manuscripts, research, and grants (Figure 1). To assess our development as faculty, we also discussed the SHARE group’s work in mentoring by reviewing academic success of mentees. Most importantly, we devoted the majority of time to discussing barriers in completing manuscripts, cultivating new research studies, and overseeing our mentees. This group discussion identified common barriers in research progress among SHARE members, and fostered strategies to help advance SHARE members’ academic agendas.

Figure 1.

We conducted SHARE sessions monthly from October 2016 to October 2017. The members of the SHARE writing group (PRC, SC, KLB, JC) were residency trained emergency medicine junior faculty who had completed subspecialty training in medical toxicology and were practicing clinical emergency medicine with variable protected time for research. During this time period, we significantly boosted our academic productivity while supporting each other in our academic interests (Table 2). We published more manuscripts, and successfully submitted multiple grants compared to the year prior to initiation of the SHARE writing group. Additionally, we were able to use the SHARE mechanism to collaborate on projects in which members had mutual interest. Beyond successful manuscripts and grant submissions, one of our most notable achievements was the mentoring of trainees in research investigations and academic writing. During this period, our trainees first-authored five peer-reviewed manuscripts and presented six abstracts as oral platform presentations at academic meetings.

Table 2.

Productivity of the SHARE session

| Activity | Productivity during SHARE Session | Productivity before SHARE Session | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed manuscripts accepted | 16 | 6 | |

| Abstracts presented at academic meetings | 25 | 12 | |

| Invited lectures presented at academic meetings | 12 | 4 | |

| Grants submitted | 13 | 1 | |

| Mentee Type | Productivity | ||

| First-authored Manuscripts | First-authored Posters | Presentations | |

| Premedical college student (N=1) | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Medical Student (N=6) | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Resident (N=5) | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Fellow (N=2) | 5 | 3 | 1 |

Benefits of successful peer mentorship

Mentorship in career advancement, grantsmanship and scientific writing is vital for successful junior faculty development. While structured mentorship has traditionally encouraged junior faculty to learn from senior faculty members, the SHARE sessions show us that junior faculty may also benefit from mutual peer support. Young academic trainees share similar barriers in starting careers—balancing clinical or teaching obligations with research interests, learning scientific writing, grantsmanship and mentoring trainees. Many of these barriers can be addressed by peers who although junior, share variable perspectives (Table 3).

Table 3.

Common barriers to productivity with potential solutions that can be explored in a peer mentorship group

| Barrier | Examples of solutions |

|---|---|

| Writing a manuscript |

|

| Navigating the Institutional Review Board (IRB): research ethics committee |

|

| Developing a research plan |

|

| Managing Mentors/Mentees |

|

Junior faculty-initiated writing groups also help recently graduated trainees learn time management strategies and techniques in editing manuscripts and grants through successes and failures of their peers. Additionally, junior faculty may feel more comfortable discussing daily operational issues surrounding navigating administrative duties, institutional review boards, and mentees among their peers. The experience of critiquing their peer’s writing, and brainstorming methods in which to advance research projects helps junior faculty develop as mentors.

Academic groups should consider implementing junior faculty peer support groups especially among graduating fellows who have likely forged friendships during training and are in a unique position to support each other as they embark in academic careers across different institutions. We have outlined some of the key features of writing groups that are important for implementation in Box 1. Long term friendships and partnerships can develop into productive academic collaborations under the framework of a junior faculty writing group described in this manuscript. The ability to bring junior faculty members together in these writing groups provides new graduates a feeling of comradery and allows continued productivity as they adjust to new institutions.

Box 1. Key features of a junior faculty writing group session.

Group members select a priori metrics of productivity that are important to monitor

Group and individual projects/metrics tracked on a shared spreadsheet that is accessible to all the members of the group using a cloud-based sharing utility

Each group member updates the spreadsheet prior to the monthly meeting

A dedicated 1–2 hour session is held every month with all group members at a central location with wireless internet access

Group systematically review projects and metrics on spreadsheet, then discussion opens to areas of concern and group brainstorms solutions

Next monthly meeting is scheduled

At the conclusion of each meeting, each member commits to completing a specific task (eg. submit a manuscript) by the next meeting

Developing a peer mentorship writing group

While most junior faculty groups include a senior faculty as a mentor, some barriers new junior faculty encounter may be best discussed among peers. While senior faculty can help junior faculty navigate promotions and grantsmanship, daily operational issues and nascent research concepts may be better discussed in a junior faculty writing group. The development of such a group should focus on two major goals: building a framework of peer support networks that nurture successful academic careers while forging collaborative relationships that can be used to help solve common barriers to academic productivity. Predetermining topics to discuss can help generate structured and productive dialogue during sessions.

To begin, interested junior faculty members should identify 2–3 colleagues who are committed to having a productive career in academic medicine. The members should have similar goals they hope to achieve through the peer mentorship group. Group members do not need to be at the same institution, but should be in geographic proximity to facilitate regular meetings. Additionally, all members should be at similar stages in their career to be considered “peers”. It is less important for the group members to have the same research areas of interest. While sharing interests can certainly lead to collaborations and foster productivity, it is not a requirement of the group.

Once the members of the group have been established, the group should identify what goals and scholarly achievement they wish to achieve. We recommend recording and tracking goals using a spreadsheet or document that can be edited and shared among group members. After defining agreed upon metrics to track, the group should schedule regular meetings at a location with accessible internet that is convenient to all group members.

Sessions should follow the same structure to stay focused and maximize productivity. Group members can decide what order to discuss business, but we recommend setting aside time to review each project a group member is working on, acknowledge successes and accomplishments that have occurred since the last meeting, and brainstorm about potential pitfalls or roadblocks. At the conclusion of each meeting, the participants can schedule their next session and set a goal they will accomplish by the next month.

Potential pitfalls

Although we had success in implementing the SHARE writing group, not all academic groups may share in our success. Our group of participants were junior faculty who were already committed to a career as clinician scientists with similar research interests, allowing us to discuss mutual barriers to completing research and publishing results. Peer groups maybe unable to achieve the same level of success if their participants do not share similar backgrounds, research interests and goals. Additionally, a variety of writing support group formats exist(1,7,10,11), and the format that positions faculty best for success should be selected. Some junior faculty who do not have as much experience in research or writing may benefit from closer guidance by senior faculty in individual mentoring programs or structured junior faculty development programs. However, even in these settings, an academic peer support group like the SHARE writing group may still be beneficial by serving as a supplement to existing faculty development initiatives.

Conclusion

The transition from trainee to junior faculty is a critical period where academic productivity can suffer. Implementing a junior faculty-focused writing group that provides structured time for discussion of academic advancement while providing peer support in an equitable environment can help guide new faculty through this transition. Our experience with the SHARE writing group demonstrates that junior faculty peer support is feasible and beneficial for participants as well as their mentees. We encourage clinical teachers to support and help learners develop junior faculty writing groups to support academic productivity. This practice may help individuals overcome barriers to their academic development as they become new faculty.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH KL2 UL1-TR001453 (Carreiro); NIH 5K24DA037109 (PI: Boyer)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: I and my co-authors have no conflicts of interest

This manuscript has not been presented previously in abstract form, nor currently submitted to any other journal.

References

- 1.Kohan DE. Moving from trainee to junior: faculty: a brief guide. Physiologist. 2014 Jan;57(1):3–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golper TA, Feldman HI. New challenges and paradigms for mid-career faculty in academic medical centers: key strategies for success for mid-career medical school faculty. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Nov;3(6):1870–4. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03900907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM. Nurturing passion in a time of academic climate change: the modern-day challenge of junior faculty development. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Nov;3(6):1878–83. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04240808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grzybowski SCW, Bates J, Calam B, Alred J, Martin RE, Andrew R, et al. A physician peer support writing group. Fam Med. 2003 Mar;35(3):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cable C, Colbert C, Boyer DM, Boyer EW. The Writing Retreat: A high-yield clinical faculty development opportunity in academic writing journal of graduate medical education. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2013 doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00159.1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ries A, Wingard D, Morgan C, Farrell E, Letter S, Reznik V. Retention of Junior Faculty in Academic Medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Academic Medicine. 2009 Jan;84(1):37–41. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181901174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gusic ME, Milner RJ, Tisdell EJ, Taylor EW, Quillen DA, Thorndyke LE. The essential value of projects in faculty development. Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1484–91. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eb4d17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010 Jan;25(1):72–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Entezami P, Franzblau LE, Chung KC. Mentorship in Surgical Training: A Systematic Review. Hand (N Y) 2011 Dec 30;7(1):30–6. doi: 10.1007/s11552-011-9379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorndyke LE, Gusic ME, George JH, Quillen DA, Milner RJ. Empowering junior faculty: Penn State’s faculty development and mentoring program. Academic Medicine. 2006 Jul;81(7):668–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232424.88922.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinert Y, Macdonald ME, Boillat M, Elizov M, Meterissian S, Razack S, et al. Faculty development: if you build it, they will come. Medical Education. 2010 Aug 17;44(9):900–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]