Abstract

Background

“Financial toxicity” is a concern for patients, but little is known about how patients consider out‐of‐pocket cost in decisions. Sacubitril‐valsartan provides a contemporary scenario to understand financial toxicity. It is guideline recommended for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, yet out‐of‐pocket costs can be considerable.

Methods and Results

Structured interviews were conducted with 49 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction at heart failure clinics and inpatient services. Patient opinions of the drug and its value were solicited after description of benefits using graphical displays. Descriptive quantitative analysis of closed‐ended responses was conducted, and qualitative descriptive analysis of text data was performed. Of participants, 92% (45/49) said that they would definitely or probably switch to sacubitril‐valsartan if their physician recommended it and out‐of‐pocket cost was $5 more per month than their current medication. Only 43% (21/49) would do so if out‐of‐pocket cost was $100 more per month (P<0.001). At least 40% across all income categories would be unlikely to take sacubitril‐valsartan at $100 more per month. Participants exhibited heterogeneous approaches to cost in decision making and varied on their use and interpretation of probabilistic information. Few (20%) participants stated physicians had initiated a conversation about cost in the past year.

Conclusions

Out‐of‐pocket cost variation reflective of contemporary cost sharing substantially influenced stated willingness to take sacubitril‐valsartan, a guideline‐recommended therapy with mortality benefit. These findings suggest a need for cost transparency to promote shared decision making. They also demonstrate the complexity of cost discussion and need to study how to incorporate out‐of‐pocket cost into clinical decisions.

Keywords: cost, ethics, heart failure, shared decision making

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Ethics and Policy, Health Services

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This study suggests that out‐of‐pocket cost is a potentially meaningful driver of decisions for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction that may make decisions about guideline‐recommended therapies preference sensitive.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

It is important for clinicians to develop approaches to providing and discussing out‐of‐pocket costs in the setting of heart failure treatment.

Introduction

In the movement toward patient‐centered care and shared decision making, out‐of‐pocket costs are often ignored. Cost communication appears infrequent between physicians and patients. In 2 recent studies, <20% of patients reported discussing costs with physicians.1, 2 Patient decision aids also rarely incorporate cost. “Financial toxicity,” however, is a real concern.3 Higher out‐of‐pocket medical costs can lead to forgone care and adverse health outcomes.4, 5, 6 They may also negatively impact medication adherence.7 Especially for patients with low income, modest costs may affect choices outside of health care. Without addressing financial implications in clinical encounters, it is difficult to align medical decisions with patients’ global values, preferences, and financial resources.

Out‐of‐pocket cost has become particularly important for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with the introduction of sacubitril‐valsartan. With no new drugs approved in the United States for this condition between 2004 and 2015, standard of care was composed of several low‐cost generic medications. This “game‐changing” drug was demonstrated to reduce the combined end point of cardiovascular mortality and heart failure hospitalization by 4.7% (absolute reduction) over 27 months compared with enalapril.8 Replacing inexpensive angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE‐Is) or angiotensin receptor blockers with sacubitril‐valsartan received a class I recommendation in recent heart failure guidelines.9 However, the retail price of sacubitril‐valsartan is ≈$4500 a year; out‐of‐pocket costs vary widely and can exceed $100 a month for many insured patients.10 This may be a significant concern, particularly for patients with fixed or low income and those who are ineligible for drug assistance. Moreover, patients with HFrEF have, on average, >4 other diseases and take nearly 10 medications.11 Although its benefits are significant, cost may make taking sacubitril‐valsartan a preference‐sensitive decision.

There are numerous barriers to incorporating costs in medication decisions: clinicians’ time is limited; out‐of‐pocket costs are often difficult for clinicians and patients to access; and cost discussions can be uncomfortable and sensitive. In addition, little is known about how patients weigh costs against medical benefits and how to present these tradeoffs to patients. Sacubitril‐valsartan provides an excellent case for studying cost communication. The objective of this study was to explore how medication costs might impact patients’ decisions about sacubitril‐valsartan and explore patient preferences on cost discussions with clinicians.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross‐sectional interview study that mixed qualitative and quantitative elements. Structured interviews were conducted with patients with HFrEF. All interviews were conducted in person, and participants received a $25 gift card. Written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request for purposes of reproduction of results.

Setting and Participants

Potential participants were screened and recruited from heart failure clinics and inpatient services using convenience sampling. Eligibility criteria included: age ≥18 years, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%, eligibility for sacubitril‐valsartan (on the basis of guidelines), and ability to provide informed consent.9 Patients with a history of heart transplant, inotrope dependence, mechanical circulatory support, or dialysis dependence were excluded. Non–English‐speaking patients were excluded because of the interactive nature of the interviews and English‐speaking interviewers.

A provision for stratified sampling to ensure racial diversity was developed but was not necessary. Participants were approached during a clinic visit or hospitalization or by telephone in advance of their visit.

The planned sample size was 50 participants. Consistent with the hypothesis‐generating goals of this study, this sample was chosen to provide reasonable point estimates of prevalence of views about an unexplored topic.

Interview Guide

A structured, interactive interview guide was developed by the investigators. It was cognitively and functionally pretested to ensure adequate communication about the drug, clarity of graphical displays, and comprehension of questions.

The interview guide (Data S1) contained open‐ and closed‐ended questions in 4 major domains: health status; demographic and financial information; views of sacubitril‐valsartan and its costs; and experiences and views of cost discussion in clinical encounters. Health status was assessed using the Euroquol 5D‐3L and by asking participants to rate their current state of health and anticipated health in the next 5 years.12 Demographic and financial data included race, sex, age, education level, employment status, financial status, annual income, monthly medication costs, and a single‐question health literacy screen.13

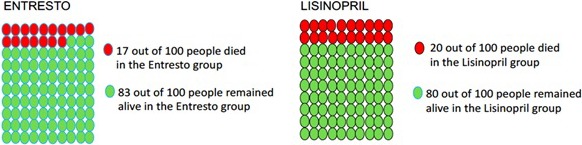

Views of the drug and its costs were solicited after description of its benefits using 3 sets of graphical displays on the basis of PARADIGM‐HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) data.14, 15 These displays demonstrated the impact of sacubitril‐valsartan on all‐cause mortality, hospitalization, and combined hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality (Figure) over a 2‐year period (described as 2 years rather than 27 months for simplicity). Participants were informed that adverse effects were similar between sacubitril‐valsartan and ACE‐Is/angiotensin receptor blockers. A standardized script with this information preceded each display. Interviewers briefly confirmed understanding of information and allowed participants to ask questions before asking further questions. Participants were then asked about their willingness to change (without reference to cost or physician recommendation) to sacubitril‐valsartan using a 5‐point Likert scale. They were then asked their willingness to change to the drug if recommended by their physician under 2 different cost scenarios: $5 more per month than their current medication; and $100 more per month than their current medication. Open‐ended probing questions were asked to reveal factors driving decision making and assess the impact of higher costs on participants’ lives. Individuals willing to switch under the $5 but not the $100 scenario were asked the maximum they would be willing to pay.

Figure 1.

Example display of all‐cause mortality benefit of sacubitril‐valsartan (Entresto).

Additional domains included views and experiences on cost discussion with clinicians (analyzed separately). Interviews generally lasted 20 to 30 minutes and were conducted by trained interviewers (G.S. and S.S.). Interviewers clarified that the study and research team members did not receive payment from any drug company related to this study.

Data Management

All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were redacted by a second study team member (A.M.). Questions with predefined response categories and demographic data were entered into Microsoft Excel. Data entry was verified during transcription review.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were tabulated for patient characteristics and questions about costs. Fisher exact tests were performed to examine potential associations between cost responses and patient characteristics. McNemar tests were performed to examine whether the proportion of participants willing to take sacubitril‐valsartan varied under different cost scenarios. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Qualitative Analysis

Transcripts of open‐ended responses were analyzed using MAXQDA. The primary analytic aim was qualitative description (ie, providing rich description of reasons for particular responses and understanding the range of views and reasons for views in key domains).16 A template analytic method was used.17 In addition to specific codes in key domains, interviews were characterized on the general approach (decider type) the participant took on sacubitril‐valsartan decisions.

A preliminary codebook was developed a priori by the research team on the basis of the guide and responses in pretesting. This codebook was expanded and refined inductively as themes emerged during transcript review (constant comparison). The codebook was considered finalized after review of the codebook and coding of a subset of interviews. All interviews were coded using the final codebook. Interviews were primarily coded by a single coder (G.S.) and double coded by at least one additional reviewer (N.D., C.S., or S.S.). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. To enhance transparency, all instances of codes of primary analytic interest were reviewed by the research team to ensure they represented a coherent theme.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Fifty‐four patients were approached; 50 were interviewed (response rate, 93%). One interview was excluded because of incomplete audiorecording. Median age was 57 years (interquartile range, 44–70 years), 43% were women, and 41% were black (Table 1). Education level and income were relatively evenly distributed, and 31% felt “somewhat” or less confident filling out medical forms. Approximately half (49%) had trouble affording discretionary items or paying bills, and median monthly medication cost was $75 (interquartile range, $25–$150). Only 4% of participants did not have insurance, 43% had Medicare, 35% had private insurance, and 18% had Medicaid. Most (80%) were not taking sacubitril‐valsartan at the time of enrollment. Only 10 (20%) participants said a provider had asked them about medication costs in the past year.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n=49)

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographic information | |

| Age, y | 57 (44–70) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 21 (43) |

| Male | 28 (57) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 20 (41) |

| White | 28 (57) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2) |

| Education | |

| High school graduate or less | 19 (39) |

| Some college | 12 (25) |

| College graduate or more | 18 (37) |

| Income, US $ | |

| <25 000 | 18 (37) |

| 25 000–100 000 | 16 (33) |

| 100 000–200 000 | 7 (14) |

| >200 000 | 3 (6) |

| Refused | 5 (10) |

| Health literacy: how confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? | |

| Extremely confident | 22 (45) |

| Quite a bit confident | 12 (25) |

| Somewhat confident | 9 (18) |

| A little confident | 3 (6) |

| Not at all confident | 3 (6) |

| Currently taking sacubitril‐valsartan | 10 (20) |

| Interview site | |

| A | 24 (49) |

| B | 25 (51) |

| Health status | |

| In general, would you say your health is: | |

| Excellent | 1 (2) |

| Very good | 3 (6) |

| Good | 20 (41) |

| Fair | 20 (41) |

| Poor | 5 (10) |

| Mobility | |

| I have no problems in walking about | 21 (43) |

| I have some problems in walking about | 27 (55) |

| I am confined to bed | 1 (2) |

| Self‐care | |

| I have no problems with self‐care | 43 (88) |

| I have some problems washing or dressing myself | 5 (10) |

| I am unable to wash or dress myself | 1 (2) |

| Usual activities | |

| I have no problems with performing my usual activities | 21 (43) |

| I have some problems with performing my usual activities | 23 (47) |

| I am unable to perform my usual activities | 5 (10) |

| Pain/discomfort | |

| I have no pain or discomfort | 22 (45) |

| I have moderate pain or discomfort | 21 (43) |

| I have extreme pain or discomfort | 6 (12) |

| Anxiety/depression | |

| I am not anxious or depressed | 26 (53) |

| I am moderately anxious or depressed | 21 (43) |

| I am extremely anxious or depressed | 2 (4) |

| Euroquol Visual Analog Scale (range, 0–100) | 70 (50–80) |

| Euroquol 5D‐3L Index score | 0.80 (0.71–0.84) |

| What do you think your health would be like in the next 5 years if you continued your current treatment with heart failure? | |

| Excellent | 7 (14) |

| Very good | 11 (23) |

| Good | 12 (25) |

| Fair | 10 (20) |

| Poor | 9 (18) |

| Financial status | |

| Financial situation | |

| After paying the bills, you still have enough money for special things that you want | 25 (51) |

| You have enough money to pay the bills, but little spare money to buy extra or special things | 14 (29) |

| You have money to pay the bills, but only because you have to cut back on things | 5 (10) |

| You are having difficulty paying the bills, no matter what you do | 3 (6) |

| Refused | 2 (4) |

| Monthly medication costs, US $ | 75 (25–150) |

Data are given as median (interquartile range) or number (percentage).

The median EQ‐5D‐3L index score of the study population was 0.80 (interquartile range, 0.71–0.84), consistent with relatively mild disease.18 However, more than half reported at least some issues with mobility, at least moderate pain, and current health as fair or poor (Table 1). Most participants (61%) believed their health would be good, very good, or excellent in the next 5 years if they continued current heart failure treatment.

Likelihood of Taking Sacubitril‐Valsartan Under Various Cost Scenarios

The first scenario asked participants about willingness to switch to sacubitril‐valsartan after scripted description of benefits and graphical displays reflecting PARADIGM‐HF results (Figure). No cost language was included, and it was not stated whether their physician recommended sacubitril‐valsartan. Thirty‐five participants (71%) said they would likely switch to sacubitril‐valsartan (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sacubitril‐Valsartan Cost Scenarios

| Scenarios | Values |

|---|---|

| Assuming you are taking a drug like lisinopril, after hearing about this medicine, would you want to change to sacubitril‐valsartan (Entresto)? | |

| 1: Definitely yes | 18 (37) |

| 2: Probably yes | 17 (35) |

| 3: Do not know | 7 (14) |

| 4: Probably no | 6 (12) |

| 5: Definitely no | 1 (2) |

| On the basis of your current health expenses and income, if sacubitril‐valsartan cost $5 a month more than your current medication, would you want to change your current medication if your physician recommended it? | |

| 1: Definitely yes | 25 (51) |

| 2: Probably yes | 20 (41) |

| 3: Do not know | 0 |

| 4: Probably no | 2 (4) |

| 5: Definitely no | 2 (4) |

| I want to imagine now that sacubitril‐valsartan cost $100 a month more than your current medication. If your physician recommended it, would you want to change to it? | |

| 1: Definitely yes | 12 (25) |

| 2: Probably yes | 9 (18) |

| 3: Do not know | 3 (6) |

| 4: Probably no | 15 (31) |

| 5: Definitely no | 10 (20) |

| If answered do not know, probably no, or definitely no to $100 more: What is the most you would decide to pay for the new medicine? (n=25, 3 did not answer) | $15 ($10–$25) |

Data are given as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

In the second scenario, participants were asked whether they would likely switch to sacubitril‐valsartan if their physician recommended it and incremental out‐of‐pocket cost was $5. Forty‐five participants (92%) said they would be likely to switch in this scenario, more than in the first scenario (P=0.0039).

In the third scenario, participants were asked whether they would likely switch if their physician recommended it and incremental out‐of‐pocket cost was $100. Twenty‐one participants (43%) said they would likely switch. This is reduced compared with the $5 scenario (P<0.001). Among those unlikely to take the medication at $100, the median amount they were willing to pay was $15 (interquartile range, $10–$25).

Reasons for Not Switching to Sacubitril‐Valsartan

Individuals unlikely to take sacubitril‐valsartan (in any scenario) were asked for their reasons. Although cost played a large role, other prevalent reasons emerged that did not center around cost but substantially affected patients’ perceptions of the drug's value. Some of these reasons focused on relative benefits (or lack thereof) of sacubitril‐valsartan or its alternatives. For example, some participants viewed the drug as only marginally better than previous heart failure therapies (ACE‐I and angiotensin receptor blocker) and regarded the benefits as insufficient to justify a switch. As one participant said, “Well I mean there really isn't much difference, variation between the 2 is a minor amount” (participant 122 734). These statements were more prevalent in the $100 scenario. Other participants did not want to change because they felt their current treatment was working well. For example, “[I'm] afraid to rock the boat or make any changes when I'm doing well” (participant 92 650).

Other non–cost‐based reasons were focused more on risk. Potential adverse effects were mentioned by some as a reason for not wanting to take sacubitril‐valsartan. This was driven by personal experience with adverse effects in the past or experiences of someone they knew with adverse effects to sacubitril‐valsartan or other medications. These concerns were typically not specific to sacubitril‐valsartan and were raised despite interviewers’ descriptions of the drug as having similar adverse effects to ACE‐I and angiotensin receptor blocker. Fewer participants were generally distrustful of new medications. They were concerned about unanticipated adverse effects or risks that might arise once a drug was available on a wider scale. They seemed to favor drugs that had been on the market for longer.

Relationship Between Willingness to Change ($100 Scenario) and Participant Characteristics

Responses to the $100 scenario were stratified by health literacy, income, education, race, and 5‐year expected health (Table 3) to provide preliminary insights into potential relationships or drivers of responses. Although there were numeric differences in willingness to switch at $100 within all categories, these differences were not statistically significant. Across all groups, a substantial number of participants said they would be unlikely to switch to sacubitril‐valsartan at the higher price. For example, 4 of 10 participants (40%) with income >$100 000 a year stated that they would be unlikely to take it at $100 more per month.

Table 3.

Willingness to Change ($100 Scenario) and Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Yes | No/Do Not Know | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health literacy (confidence filling out forms) | 0.36 | ||

| Extremely confident | 13 (59) | 9 (41) | |

| Quite a bit confident | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | |

| Somewhat confident | 3 (33) | 6 (67) | |

| A little confident | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | |

| Not at all confident | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | |

| Income, US $ | 0.40 | ||

| <25 000 | 6 (33) | 12 (67) | |

| 25 000–100 000 | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | |

| >100 000 | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | |

| Refused | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| Education | 0.27 | ||

| High school or less | 8 (42) | 11 (58) | |

| Some college | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | |

| College or more | 10 (56) | 8 (44) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.24 | ||

| Black | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | |

| White | 10 (36) | 18 (64) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

| 5‐y Health expectation | 0.21 | ||

| Excellent | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | |

| Very good | 7 (64) | 4 (36) | |

| Good | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | |

| Fair | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | |

| Poor | 1 (11) | 8 (89) |

Data are given as number (percentage).

Participants with worse 5‐year health expectations were numerically less likely to want to switch to sacubitril‐valsartan at $100 than those with better 5‐year health expectations. Only 1 of the 9 participants (11%) who said they expected their health to be poor was likely to switch.

Approaches to Decision About Sacubitril‐Valsartan

Participants reflected a range of decision‐making approaches in response to open‐ended probes about their willingness to take the drug under different scenarios. More important, most participants exhibited multiple approaches to decision making.

The most commonly used approach was cost‐benefit analysis. These decisions were driven by weighing stated benefits of the drug against its costs (Table 4). This is distinctive from “straight cost analysis,” in which participants focused simply on whether they could afford the drug without specific mention of potential benefits. Most of the participants (78%) exhibited some form of cost analysis.

Table 4.

Approaches to Decision About Sacubitril‐Valsartan

| Decider Type | Example Quotations |

|---|---|

| Cost‐benefit analysis | P: Cause $100 is just too much for medicine ain't it? It's not that much difference in the charts, 2 or 3 people out of 100. |

| Straight cost analysis |

I: Can you tell me more about how you decided on this answer? Because you told me you were not doing that well on lisinopril. P: It's strictly because of finances, and if it's that much more I can't do anything about it. |

|

I: Definitely no. Can you tell me more about how you decided about this answer? P: Just off a budget. Cause right now what I am paying is high now with my copays so to do an increase definitely wouldn't work, being on disability. | |

| Health above all | P: If it's going to strengthen my heart and save my life it wouldn't matter. |

| P: I mean if it was $1000 a month or something just outrageous, I probably would have to really think about it because, you know, in a year that's really going to add up, but at the end of the day if it's something that can save your life‐there's no price. | |

| Physician's recommendation is what matters |

P: I'm going to say I don't know because I want to discuss it further with my physician. I: Sure. P: I don't believe that mass results necessarily relate to any one given… I put more faith in the opinion of my own physician. |

| Status quo based | P: If it's working you know like I said, “If it ain't broke then don't fix it.” |

I indicates interviewer; P, participant.

Seven participants were specifically averse to cost considerations, stating their health was so important that they would not want cost to affect their decision about whether to take a recommended medication. These individuals sometimes expressed concerns about cost, acknowledged that affording the medication could involve significant sacrifice, and recognized that cost could be prohibitive. However, they stated a strong desire to avoid cost as a basis for a decision.

Other approaches, often concurrent with cost concerns, involved considerations other than probabilistic information. Some participants viewed their physician's recommendation as most important. Sometimes they considered cost‐benefit tradeoffs and other factors as well, but their physician's suggestion was the driving factor rather than their assessment of benefits as presented. For others, a priority was maintaining the status quo. These patients did not want to change medication for fear that things could get worse. Finally, some individuals stated that personal experience or others’ experience with sacubitril‐valsartan drove their assessment.

Discussion

Using the example of sacubitril‐valsartan in HFrEF, this study provides insights into the potential role of cost in shared decision making for beneficial but expensive medications. Cost discussions are infrequent in clinical encounters, there may be multiple barriers to integration of costs into decisions, and little is known about how patients view tradeoffs between out‐of‐pocket cost and medical benefit. However, because out‐of‐pocket costs matter to patients, cost is highly relevant for clinical decision making.

The most striking finding is the decrease in willingness (43% versus 92%) to take sacubitril‐valsartan in the high ($100) versus low ($5) cost scenario. Many cardiologists would argue the decision about sacubitril‐valsartan in eligible patients is not preference sensitive, because it is guideline recommended, has demonstrated superiority over ACE‐I, and is well tolerated. However, the change in willingness observed in this study demonstrates that cost may make this decision preference sensitive and appropriate for a shared decision‐making approach. Although much of the shared decision‐making literature has focused on decisions that are medical “toss‐ups,” this finding demonstrates that factors other than medical risks and benefits can make shared decision making important.

It is also notable that these data suggest cost may be relevant across a range of copayments and patients. The current distribution of copayments across payers for sacubitril‐valsartan is unknown; however, $100 is well within the range of current copayments, especially for patients ineligible for pharmaceutical assistance programs (eg, those covered by Medicare part D). Moreover, the median price most people stated they were willing to pay per month (who were not willing to pay $100) was $15. Concerns about cost are likely to be prevalent for this medication, and they do not appear to be limited to situations in which individuals have very high copayments.

Similarly, cost sensitivity was not isolated to low‐income patients. A substantial number of people in every stratum of our population stated they would be unlikely to take sacubitril‐valsartan under the $100 cost scenario. Despite the fact that there was a numeric increase in willingness to take the drug as income increased, 4 of 10 individuals with annual income >$100 000 were unlikely to take it in the $100 scenario. Price thus has special salience in populations with financial barriers but may be relevant across all patient populations. More important, more work needs to be done to explore patients’ conceptions of value for medication.

In addition to highlighting the importance of cost integration, the study provides insights into the complexities and hazards of cost discussions. First, patients approached cost‐related decisions in heterogeneous ways. Some explicitly engaged in cost‐benefit tradeoffs, whereas others rejected cost as a basis for decisions altogether. Still others made “straight‐cost” decisions about what they can afford. Cost will thus play different roles in decisions for different patients. Second, patients illustrated different uses of probabilistic information. Many patients did not explicitly use numeric data in their assessments about the drug, and a “physician's recommendation” was often highly influential. Some patients clearly saw this as a life or death situation on the basis of the data presented and did not appreciate the incremental benefit of sacubitril‐valsartan. Others dismissed the drug's important benefits as minimal or meaningless. Both interpretations are problematic. Certainly, trivializing a nearly 3% absolute risk reduction in mortality is worrisome when this reduction is as significant as (and is additive to) many other guideline‐recommended HFrEF therapies.

Together, these findings reinforce that implementing shared decision making can be difficult and that the presentation of evidence in encounters is likely to matter substantially. Numeric framing effects (eg, presentation of absolute or relative risks and survival versus mortality data), anchoring effects related to understanding of present prognosis, and whether it is mentioned that this drug is guideline recommended will likely impact patients’ decisions. Careful attention to these issues, and avoidance of frames that inappropriately accentuate or minimize risks or benefits, is essential. However, entirely neutral presentations in the context of a guideline‐recommended therapy with a demonstrated mortality benefit may also not be ideal.19

One surprising finding was that participants with a less favorable view of their future were numerically less frequently willing to switch to sacubitril‐valsartan. This finding was not statistically significant, but we had predicted that the reverse relationship would exist, that individuals with a worse outlook would be more eager to change. This phenomenon may represent a form of status quo bias that warrants further study and illustrates the psychological and emotional complexity of many decisions in serious chronic illness.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was an exploratory study with a small sample; these findings are hypothesis generating. Second, participants were from a single health system in a geographically small area, although they were diverse in age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, and income. Third, the scenarios were hypothetical. This was necessary to examine decisions under varying scenarios, but these decisions may not reflect decisions in practice. Related, there may be an order effect of the $5 and $100 cost scenarios, although this is unlikely to explain the dramatic shift we observed. Future studies should be done within actual physician‐patient encounters and can elucidate, for example, whether cost has played a role in driving slower than expected uptake of sacubitril‐valsartan.20 Fourth, some participants were already taking the drug and may have different views. Fifth, the effect of framing is unavoidable when administering interview questions and presenting probabilistic data. The interview guide was designed to be balanced (eg, presenting absolute risk rather than relative risks), but understanding of absolute risk may be limited, and ideal framing of this information is not established. Finally, selection bias is possible with small sample size and convenience sampling, although the diversity of the population and a high response rate (93%) lessen this concern.

Conclusion

Out‐of‐pocket cost may play an important, complex role in decisions about sacubitril‐valsartan and other medications with significant benefits. In this respect, the decision about whether to switch a patient with HFrEF to sacubitril‐valsartan can become preference sensitive despite a guideline recommendation and robust medical evidence.9 This study adds to growing literature suggesting the importance of integrating cost into shared decision making despite the fact that such conversations are rare. These findings also clarify that approaches to decisions about sacubitril‐valsartan and cost‐benefit tradeoffs vary among patients. Successful integration of out‐of‐pocket cost into shared decision making requires significant further research.

Disclosures

Drs Dickert, Allen, Moore, and Morris receive research funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01HS026081‐01) related to cost and shared decision making. Dr Allen has served as a consultant for Novartis (clinical events committee). The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1. Interview guide.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010635 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010635)

References

- 1. Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, Tulsky J, Ubel P, Schrag D, Nicolla J, Abernethy AP, Peppercorn J, Zafar SY. Patient‐oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290:953–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out‐of‐pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X, Abernethy AP. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out‐of‐pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richman IB, Brodie M. A national study of burdensome health care costs among non elderly Americans. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dayoub EJ, Seigerman M, Tuteja S, Kobayashi T, Kolansky DM, Giri J, Groeneveld PW. Trends in platelet adenosine diphosphate P2Y12 receptor inhibitor use and adherence among antiplatelet‐naive patients after percutaneous coronary intervention, 2008–2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:943–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos G, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;134:e282–e293. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grainger D. Is the superiority of entresto just an illusion? Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidgrainger/2015/09/14/is-the-superiority-of-entresto-just-an-illusion/#647ee2770a4f. Accessed February 10, 2017.

- 11. Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Peterson ED, Krumholz HM. Medication initiation burden required to comply with heart failure guideline recommendations and hospital quality measures. Circulation. 2015;132:1347–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Janssen B, Szende A, Cabases J, eds. Self‐Reported Population Health: An International Perspective Based on EQ‐5D. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coylewright M, Dick S, Zmolek B, Askelin J, Hawkins E, Branda M, Inselman JW, Zeballos‐Palacios C, Shah ND, Hess EP, LeBlanc A, Montori VM, Ting HH. PCI choice decision aid for stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hess EP, Knoedler MA, Shah ND, Kline JA, Breslin M, Branda ME, Pencille LJ, Asplin BR, Nestler DM, Sadosty AT, Stiell IG, Ting HH, Montori VM. The chest pain choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cassell C. Template Analysis: The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Management Research. London, England: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ‐5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorin M, Joffe S, Dickert N, Halpern S. Justifying clinical nudges. Hastings Cent Rep. 2017;47:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luo N, Fonarow GC, Lippmann SJ, Mi X, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, Hardy NC, Turner SJ, Laskey WK, Curtis LH, Hernandez AF, Mentz RJ, O'Brien EC. Early adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from get with the guidelines heart failure (GWTG‐HF). JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Interview guide.