Abstract

Exophytic lesions of the tongue encompass a diverse spectrum of entities. These are most commonly reactive, arising in response to local trauma but can also be neoplastic of epithelial, mesenchymal or miscellaneous origin. In most cases, the microscopic examination is likely to provide a straightforward diagnosis. However, some cases can still raise microscopic diagnostic dilemmas, such as conditions that mimic malignancies, benign tumors with overlapping features and anecdotal lesions. A series of “lumps and bumps” of the tongue are presented together with suggested clues that can assist in reaching a correct diagnosis, emphasizing the importance of the clinico-pathological correlations.

Keywords: Tongue, Lumps and bumps, Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, Verrucous lesions, Neural lesion, Spindle cell tumors, Adipocytic tumors, Lymphoid-rich lesions

Introduction

Exophytic lesions of the tongue encompass a diverse spectrum. These are most commonly reactive, arising in response to local trauma (e.g., irritation fibroma, pyogenic granuloma, mucocele), but can also be neoplastic of epithelial, mesenchymal or salivary gland origin. Malignancy, most commonly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), should also be considered when manifested as an exophytic lesion [1]. Infectious conditions, such as tuberculosis or syphilis, and immunologic disorders, such as amyloidosis or sarcoidosis, may also present lumps and bumps. Variations of anatomic structures, like the lingual tonsil or ectopic thyroid should also be included in the differential diagnosis. In spite of the shared clinical appearance, the microscopic study is likely to provide a straightforward diagnosis in most instances. However, some cases can still raise microscopic diagnostic dilemmas, like benign tumors with overlapping features, conditions that mimic malignancies and anecdotal lesions.

The purpose of this manuscript is to present a series of “lumps and bumps” of the tongue with microscopic diagnostic dilemmas and to highlight the importance of clinico-pathological correlations.

Dilemmas Involving Epithelial Lesions

Dilemma #1: Epithelial Hyperplasia: Malignant or Not?

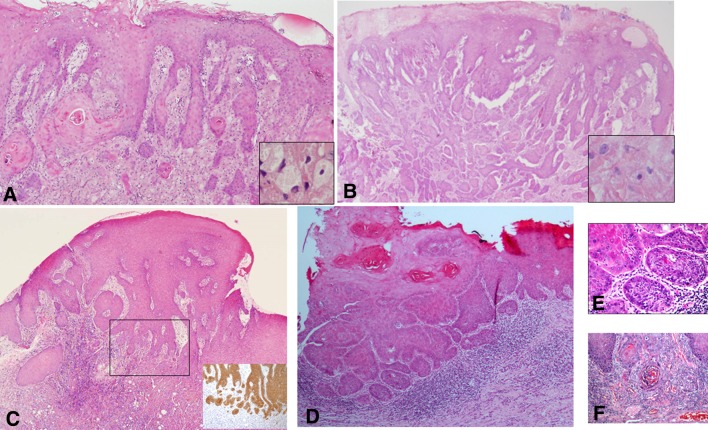

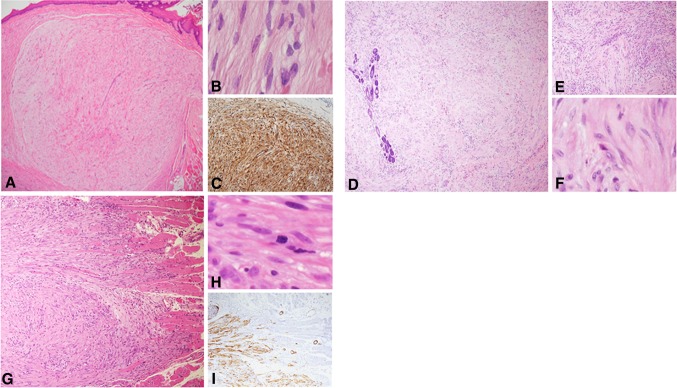

Figure 1a and b show hematoxylin and eosin stained slides from two tongue lesions that feature marked epithelial hyperplasia with an endophytic pattern of growth and apparently infiltrating islands into the connective tissue. Part of the “infiltrating” islands also display keratinization, either individual cell keratinization or keratin pearls. The emerging dilemma is to distinguish between a florid reactive epithelial hyperplasia, i.e., pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH), and frank dysplastic/neoplastic epithelial proliferation. In the tongue, PEH is most commonly associated with granular cell tumor (GCT) (Fig. 1a, b), a benign lesion with predilection for the dorsal tongue [1]. Albeit this location is rare for SCC of the tongue, cases in which the granular cells are scarce and hardly identified, or if the biopsy is too superficial, might be misdiagnosed as SCC (Fig. 1c). More confusing are epithelial proliferations on the lateral aspect of the mid-third of the tongue, which is considered as an area with high risk for SCC. A background of oral lichen planus (OLP), considered by some as a premalignant condition [2], might add further challenge in the interpretation of these lesions (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

a Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the lining oral epithelium associated with granular cell tumor. Deeply set and separate epithelial islands with keratin pearls are such a prominent feature that the adjacent granular cells may be overlooked (inset). This may lead to misdiagnosis of the case as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. However, the hyperplasia lacks cellular atypia and represents a completely benign process (H&E, original magnification × 100). b An additional example of florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia associated with granular cell tumor mimicking infiltration, which may lead to misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma. Granular cells are present but scarce (inset) (H&E, original magnification × 100). c In biopsy from the lateral aspect of the tongue, the distinction between pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma necessitated immunostaining with cytokeratin that highlighted frank infiltration in the form of small epithelial clusters and nests (inset), leading to the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. (H&E, original magnification × 40). d Another disputable lesion of the lateral tongue on the background of oral lichen planus. (H&E, original magnification × 100). e and f The malorientation of the specimen preventing accurate diagnosis was solved with serial deep sections in which true invasion was demonstrated (H&E, e original magnification × 200, f original magnification × 400)

The dilemma between a reactive and a neoplastic epithelial hyperplasia becomes even more challenging in cases of small, fragmented and maloriented biopsies. For practical purposes, in cases of sub-optimal biopsy material, repositioning the tissue within the paraffin block, serial deep sections (Fig. 1e, f) or even re-biopsy from residual lesions could help in reaching an accurate diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains for p16, p53, E-cadherin, matrix metalloproteinase1 and Ki67 may be used as an aid in diagnosis, as their expressions are expected to increase with the grade of dysplasia and to be highly expressed in SCC, while limited in PEH [3, 4].

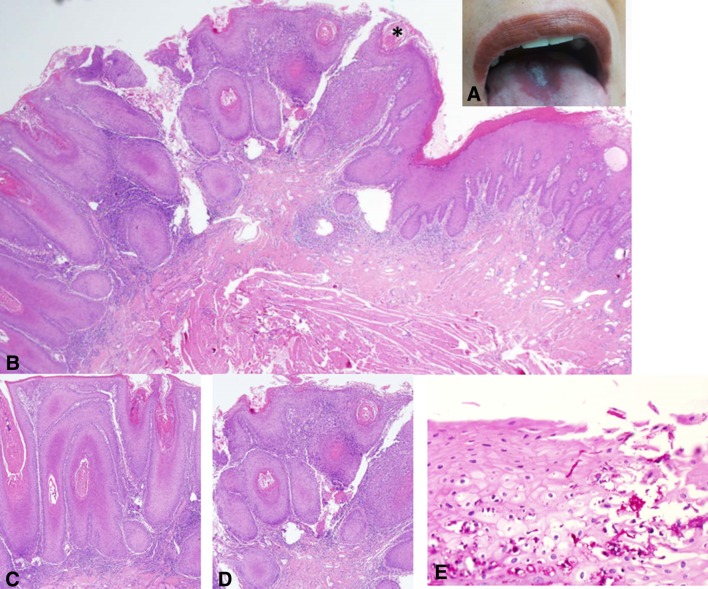

Dilemma #2: Verrucous Epithelial Hyperplasia: Confusing and Frustrating

Figure 2a shows a thick white keratotic plaque at the midline of the posterior dorsal tongue, surrounded by an erythematous rim of papillary atrophy. Microscopically, it was characterized by a verrucous pattern of epithelial hyperplasia, with minimal cellular atypia, “pushing” front, marked keratinization with keratin plugs and interface lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Fig. 2b, d). These features overlap those of verrucous carcinoma (VC) [1]. However, the illustrated case is an example of median rhomboid glossitis (MRG)- like lesion, which mimics VC. The presence of candida is a frequent finding in MRG (Fig. 2e), however it can also be superimposed on VC, therefore it cannot serve as a diagnostic clue. The mid-dorsal tongue is a characteristic location for MRG with a very low propensity for VC or SCC, and, still there are challenging cases that might be the result of inadequate or mal-orientated biopsies. In cases of VC we would expect an abrupt transition zone between normal and lesional epithelium [1]. In addition, partial or complete disappearance of the dorsal tongue lesion following antifuntal treatment would also be helpful in establishing a diagnosis of candidiasis.

Fig. 2.

a A white exophytic, nodular symmetrical lesion at the midline dorsal aspect of the tongue, middle third. An erythematous, smooth-surfaced hallow surrounds the white lesion. Although a diagnosis of median rhomboid glossitis has been clinically submitted, an incisional biopsy was taken due to the unusual appearance of this particular lesion. b Microscopically, the lesion demonstrated a nodular-to-verrucous type of epithelial proliferation, hyperkeratosis, including formation of keratin “plugs” and an associated band of chronic inflammation, all of which confer the lesion an appearance reminiscent of verrucous carcinoma (H&E, original magnification × 40). c and d A higher magnification shows no remarkable cellular atypia (H&E, original magnification × 100) a common feature to both MRG and VC. e Candidal hyphae are seen penetrating the surface (PAS, original magnification × 600). The clinical and microscopical findings favored a diagnosis of “nodular” median rhomboid glossitis over that of verrucous carcinoma

Dilemma #3: Multiple Lumps: Simultaneously Occurring or Part of a Known Entity?

A young patient presented with multiple lumps of the tongue and lips, one of the lesions was submitted for microscopic examination. Figure 3 is the microscopic slide that shows findings of fibroepithelial hyperplasia. A meticulous inspection of the epithelium revealed a few “mitosoid”-like cells, favoring the diagnosis of focal epithelial hyperplasia/Heck’s disease over that of multiple fibroepithelial hyperplasias.

Fig. 3.

A biopsy from a girl with multiple exophytic lesions on the oral mucosa including the tongue. Each lesion is about 0.5 cm in diameter. Microscopically, there is hyperplasia and acanthosis of the lining epithelium overlying an exuberant collagenous connective tissue (H&E, original magnification × 40). The differential diagnosis was between multiple lesions of reactive fibrous hyperplasia (i.e., fibrous epulis/irritation fibroma) and Heck’s disease. The identification of a mitosoid cell in the spinous layer (inset) favored a diagnosis of Heck’s disease

Fibrous hyperplasia is the result of exuberant collagen production in response to local irritation [1]. The lining epithelium may be either atrophic or hyperplasic. In the latter, and especially when multiple lesions occur in young patients, a diagnostic dilemma between multiple fibroepithelial hyperplasias and Heck’s disease can arise. This would become particularly challenging if koilocyte-like or “mitosoid” cells are scant. True koilocytes are human papilloma virus (HPV)-altered cells that appear in clusters, characteristically beneath the keratinized layer, have optically clear cytoplasm and a “raisin-like” pyknotic nucleus [1]. Mitosoid cells may resemble true koilocytes, are found in the spinous layer, and possess nuclei that mimic a mitotic process [1]. Their numbers are usually small-to-inconspicuous thus their diagnostic value is equivocal. Auxiliary tests include detection of HPV types 13 and 32 by means of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and in situ hybridization (ISH) for presence of HPV-DNA [1]. Since there is no specific treatment for Heck’s disease, and given its tendency for spontaneous regression [1], the cost of any of these tests may not be justified in the majority of cases. The clinical correlations consisting of additional affected family members and presence of lesions from early childhood, may be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis.

Dilemmas Involving Mesenchymal Lesions

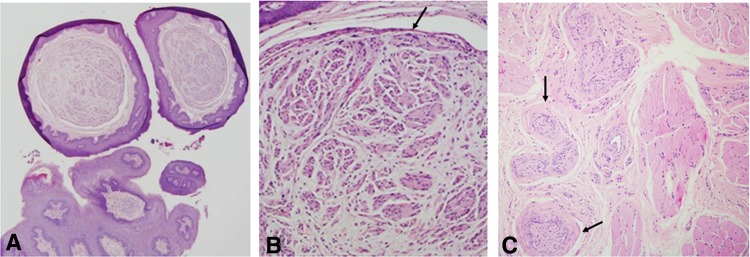

Dilemma #4: Lesions with Nerve Fibers: Non-significant or Life-Threatening?

Figure 4a is the microscopic section taken from one of multiple small-sized (about 5 mm) bumps on the anterior dorsal aspect of the tongue. It was composed of hyperplastic bands of nerve bundles surrounded by loose connective tissue (Fig. 4b). In general, these are findings seen in neuromas, which can be of a reactive/traumatic nature or true neoplasms. The latter are associated with, and usually the first sign of, multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN)-2B syndrome. MEN2B is an autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome caused by missense gain-of-function mutations in the RET proto-oncogene on chromosome 10 [6]. Oral mucosal neuromas appear as soft painless papules or nodules that mainly affect the anterior tongue and lips, but may also be seen at other oral sites. Timely diagnosis of MEN2B syndrome is crucial, due to the remarkably increased risk in these patients to develop malignant tumors at a young age, especially medullary carcinoma of the thyroid that presents a mean age of 35 years at presentation [1, 6]. Therefore, preventive thyroidectomy is recommended as early as possible. Mucosal neuromas are usually characterized by a thickened perineurium [1], however this finding may be variable (Fig. 4b). The reactive/traumatic type of neuromas, on the other hand, are not encapsulated, and show haphazardly oriented well-organized peripheral nerves that attempt to form nerve regeneration; an inflammatory component may also be present [1]. Figure 4c presents an uncommon example of a traumatic neuroma with thickened perineurium, which is usually a feature of MEN2B mucosal neuromas. Thus, the thickness of the perineurium is not a pathognomonic finding of mucosal neuromas and cannot accurately distinguish them from traumatic neuromas on a histomorphological ground. In these equivocal cases, clinico-pathological correlations are likely to help reaching a correct diagnosis. Symptoms of pain, hyperesthesia or other sensory disturbances would support a diagnosis of traumatic neuromas, while mucosal neuromas in MEN2B are asymptomatic. Furthermore, a marfanoid appearance of the body, low muscle mass, sometimes with myopathy and the development of pheochromocytoma are additional signs of MEN2B would also support the diagnosis of MEN2B, however, these features may not be obvious prior to puberty.

Fig. 4.

a This is a biopsy from a 30 years old male with multiple pale raised papules on the anterior dorsal surface of the tongue with a yet undiagnosed MEN2B. Microscopically, there are subepithelial, well-circumscribed spindle cell nodules (H&E, original magnification × 40). b At a higher magnification, the nodules contain axonal-like structures embedded in a background of loose connective tissue, with a delicate capsule at the periphery (arrow) (H&E, original magnification × 200). The diagnosis was multiple mucosal neuromas, which demands a general work-up to rule out the diagnosis of MEN2B syndrome. The capsule of the nodules represents the perineurium. This patient was diagnosed with a medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. c This is an example of a traumatic neuroma from the tongue in a 31 years old male patient. Clinically, the lesion was mildly painful and appeared following a previous biopsy in the same area. Note the unusual thickened perineurium around the nerve bundles (arrows) (H&E, original magnification × 100)

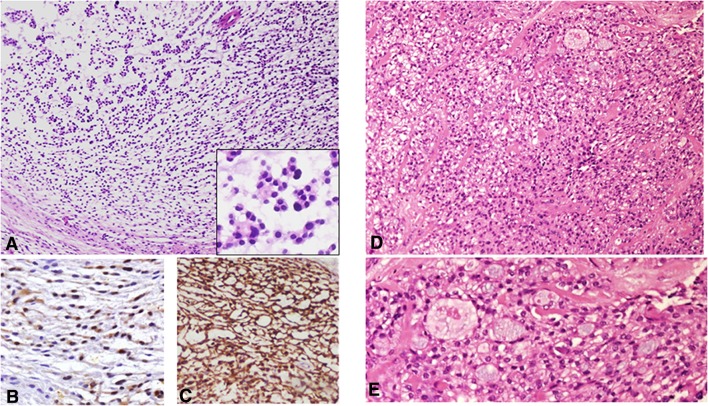

Dilemma #5: Spindle Cell Tumors with Smooth Muscle Differentiation: The Rare, the Young and the Dangerous

Figure 5 shows photomicrographs of three different spindle cell tumors of the tongue. All tumors present various degrees of positivity for myoid markers, such as smooth muscle actin, calponin, h-caldesmon and desmin. The tumor in Fig. 5a–c was well circumscribed and presented no cellular atypia. The tumor in Fig. 5d–f was less circumscribed, but had a benign morphology and presented alternating pale and dark areas (zonation phenomenon). The tumor in Fig. 5g–i infiltrated between muscle fibers and the cells showed mild atypia. In general, a well-circumscribed spindle cell tumor of the dorsal tongue with smooth muscle differentiation raises the possibility of a leiomyoma or a myofibroma, and accurate clinico-pathological correlations assists in reaching the correct diagnosis. Leiomyomas of the oral cavity are rare and appear across a wide age range with an onset in the 4th–6th decades [7]. Morphologically almost all oral leiomyomas are either solid or vascular [1, 7]. They consist of interlacing bundles of spindle shaped cells. The nuclei are elongated pale staining with blunt, “cigar-shaped” ends (Fig. 5b). Myofibromas (solitary and multicentric) occur across a wide age range, but are most common at birth or during infancy [8]. The most common location of the solitary myofibromas is the head and neck region. They are believed to arise from perivascular contractile myoid cells [8]. The proliferating cells are myofibroblasts, which are modified fibroblasts morphologically and functionally, similar to both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells [8]. The tumors usually present a zonation phenomenon on low magnification, with alternating pale and dark areas. The nuclei are plump and show sharp rather than blunt ends (Fig. 5f). Although both leiomyoma and myofiborma stains positively with myoid markers (e.g., smooth muscle and muscle specific actin and desmin), it is only the leiomyoma that presents diffuse positivity to h-caldesmon. Typically, myofibroma is strongly positive for calponin and fibronectin [9, 10].

Fig. 5.

a Leiomyoma of the tongue shows a well-circumscribed highly cellular lesion with intersecting bundles of spindle-shaped cells (H&E, original magnification × 40). b “Cigar”-shaped nuclei of the cells suggested leiomyoma (H&E, original magnification × 400). c Immunostaining with h-caldesmon shows a diffuse and strong immunoreaction (h- caldesmon, original magnification × 100). d Myofibroma of the tongue presenting a highly cellular lesion with intersecting bundles of spindle-shaped cells involving the salivary glands of the posterior tongue (H&E, original magnification × 40). e The-zonation phenomenon of interchangeable darker and lighter areas of myofibroblastic cells is typical for myofibroma (H&E, original magnification × 100). f The nuclei of myofibroblasts have crescent sharp edges (H&E, original magnification × 200). g Low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma infiltrating into the tongue striated muscles (H&E, original magnification × 40). h Cellular atypia in low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma; a mitotic figure in the center of the photomicrograph (H&E, original magnification × 400). i Calponin immunoreactivity in low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma highlights the infiltrative pattern of the tumor (Calponin, original magnification × 40)

When tumors with an immunohistochemical profile of myofibroblasts demonstrate an infiltrative pattern of growth and an increased degree of cellular atypia, a low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma (LGMS) should also be considered. This tumor is most frequently found in the head and neck, particularly in the tongue, mostly in the 5th decade of age [9]. It is a painless slow growing tumor, with a relative indolent course, but with a propensity for local recurrence. Histopathologically, it is composed of slender spindle cells showing low mitotic activity and variable nuclear pleomorphism. The nucleus may be fusiform, slender and undulated. Meticulous examination of the tumor histomorphology is mandatory for an accurate diagnosis, as the immunohistochemical profile of tumor cells is identical to their benign counterparts.

Dilemma #6: Clear Cells in Myxoid Stroma: A Rare Combination

Figure 6 presents two different tumors of the tongue that on occasion have overlapping histopathological features. Overall, both tumors are architecturally lobulated with a fibrous-to-myxoid stroma, composed of bland polygonal cells with a clear cell component, arranged in reticular and globoid patterns. The tumor in Fig. 6a–c is well circumscribed and presents immune-reactivity for S-100 stain (Fig. 6b) and glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP) (Fig. 6c), while the tumor in Fig. 6d, e is partially infiltrative with areas of hyalinization and presents positivity for keratins and p63. The diagnosis of the former is ectomesenchymal chondromyxoid tumor (EMCT) and the latter - clear cell carcinoma (CCC).

Fig. 6.

a Microscopically, ectomesenchymal chondro-myxoid tumor is usually characterized by a lobulated architecture with a myxoid stroma and bland polygonal cells arranged in a globoid pattern (H&E, original magnification × 40). Inset: tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and dark staining nuclei. b S100 is typically positive in ectomesenchymal chondro-myxoid tumor (S100, original magnification × 100). c GFAP positivity in ectomesenchymal chondro-myxoid tumor (GFAP, original magnification × 100). d Clear cell carcinoma of salivary glands can also present nests of monomorphic clear cells in a myxoid-to-hyaline stroma and a glandular-like arrangement, which occasionally could raise the differential diagnosis with ectomesenchymal chondro-myxoid tumor (H&E, original magnification × 100). e Clear cells, myxoid areas and a glandular-like pattern of clear cell carcinoma (H&E, original magnification × 200)

EMCT is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm of uncertain origin, with a striking predilection for the anterior dorsal tongue [11]. Tumors occur predominantly at early-mid adulthood and are small, long-standing masses. Excision is usually curative but a minority of the cases recur locally. Morphologically the tumors are lobulated with fibrous septae separating bland polygonal spindle cells in many cases intermixed with clear cells, arranged in reticular and globoid patterns in a myxoid stroma [11]. The immunophenotype reported is variable, but most cases express GFAP and S100 proteins with an inconsistent expression of keratin and myoid markers [11]. A subset of cases has been reported to harbor EWSR1 gene rearrangement. In addition, the RREB1–MKL2 fusion product was recently found to be expressed in most of the cases [12]. Rarely, EMCT may microscopically resemble CCC of salivary gland origin. The tongue was found as the second most common oral location of CCC [13]. This uncommon low-grade indolent neoplasm with a female predominance is morphologically characterized by nests of monomorphic clear cells within a hyaline stroma [14]. It demonstrates cords, trabeculae, and nests of monomorphic clear cells as well as cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. Mild cellular atypia is occasionally seen and mitoses are rare [14]. However, the stroma can be either hyalinized or myxoid in which cases it may raise the diagnostic dilemma of CCC versus ECMT. As the EWSR1 translocation characterizes both tumors [15, 16], it seems that it is the immunohistochemical profile that can practically differentiate between these tumors, based on the definite positivity of CCC for epithelial markers and of EMCT for GFAP and S-100 [11].

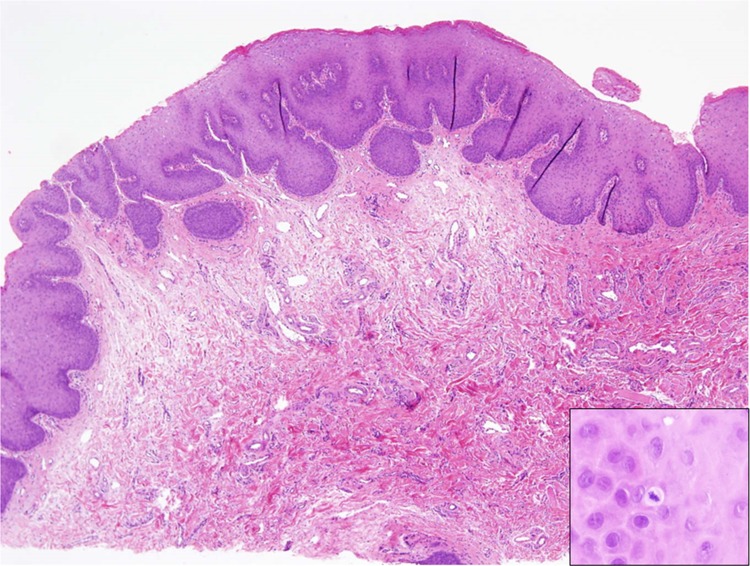

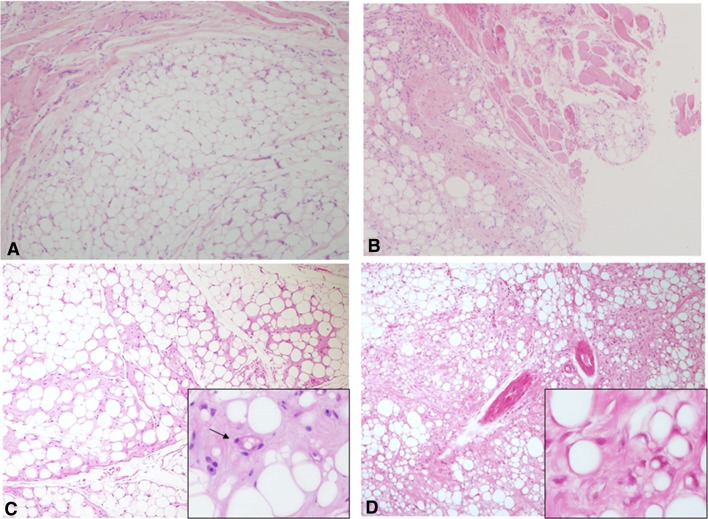

Dilemma #7: Adipocytic Tumors: Good or Bad?

Figure 7 displays four examples of lipomatous tumors of the tongue. A well-circumscribed tumor with uniformly sized adipocytes should be a straightforward diagnosis of lipoma (Fig. 7a). When the adipocytic tumor infiltrates among the muscle fibers of the tongue, but the cytology is bland, the tumor could be diagnosed as an intramuscular lipoma (IML) (Fig. 7b). However, when an adipocytic tumor contains lipoblasts, the possibility of well differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT) should be raised. It should be noted that lipoblasts can also appear in benign adipocytic tumors, so that their presence as a single feature is insufficient to render a diagnosis of ALT [17]. In a background of a well circumscribed mass of uniformly sized adipocytic cells with occasional lipoblasts, the tumor should be diagnosed as benign (Fig. 7c). A diagnosis of ALT is suggested if the mass is poorly circumscribed and in addition to the presence of lipoblasts the tumor also shows variably-sized adipocytes and a multi nodularity pattern, which is conferred by fibrous septae that harbors pleomorphic, hyperchromatic cells [18, 19] (Fig. 7d). ALT should be kept in the differential diagnoses of adipocytic lesions of the tongue, this being the most common location of ALT [19].

Fig. 7.

a Lipoma of the tongue showing a well circumscribed tumor of mature, uniformly sized adipocytes (H&E, original magnification × 40). b Intramuscular lipoma features an infiltrative growth pattern of mature adipocytes between the muscle fibers (H&E, original magnification × 40). c Lipoma with lipoblasts is essentially a lipoma same as in a, however occasional cells resembling lipoblasts can be encountered (inset) (H&E, original magnification × 40). d Atypical lipomatpus tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma of the tongue presents an infiltrative growth pattern, variably sized adipocytes and fibrous septae containing atypical neoplastic adipocytes (H&E, original magnification × 40). Inset shows some multivacuolar lipoblasts with eccentric, crescent/signet-ring-like nuclei

Lipoblasts are histologically defined as lipid-containing, mono- or multi-vacuolated cells possessing hyperchromatic, indented or often scalloped nuclei [17, 20]. They are identified in neoplastic conditions and assumed to recapitulate the differentiation process of normal fat, like their potential normal counterparts, the pre-adipocytes or pre-adipose cells. Traditionally, identification of lipoblasts has been considered as a key feature in the diagnosis of liposarcomas. However, this might be challenging due to the morphological similarity between lipoblasts to a variety of histological mimickers, such as Lochkern cells, brown fat cells and pseudo-lipoblasts (17). Currently, lipoblasts are not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of liposarcomas, in part because some benign tumors harbor lipoblasts or lipoblast-like cells [17]. Even if lipoblasts are not necessarily definite markers for adipose tissue malignancy, their presence together with fibrous septae, cytological atypia and an infiltrative growth pattern could raise the possibility of ALT, especially when the lesion is located in the tongue. Cytogenetic analysis, if available, may be of help in reaching the diagnosis, as ALT can occasionally display a t(3;8)(q28;q13) translocation. MDM2 protein encoded by a gene at 12q13–15 may distinguish well differentiated liposarcoma from benign adipose tumors (negative) [20, 21].

Dilemmas of Lesions of Miscellaneous Origins

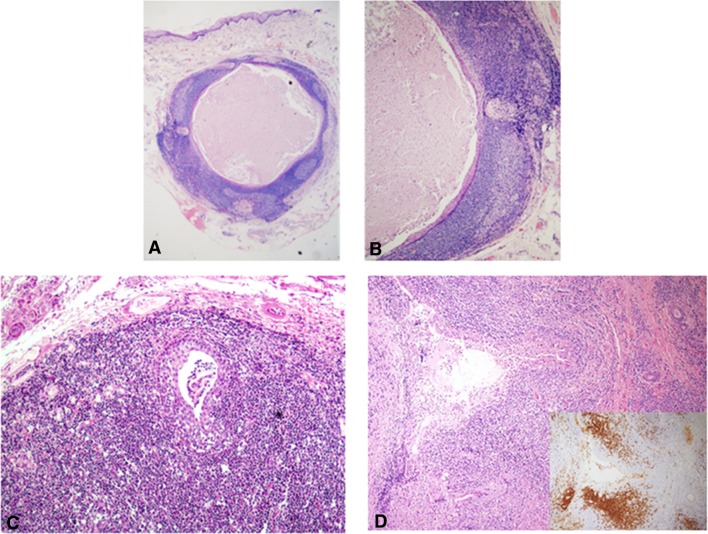

Dilemma #8: Lymphoid Tissue of the Tongue: Worrisome or Not?

Figure 8 shows sub-epithelial lesions of the ventral tongue, composed of a combination of lymphoid tissue and epithelial components. When the lining epithelium invaginates into the adjacent lymphoid tissue, it forms blind crypts. These may become obstructed by keratin debris, and thus produce a keratin filled cyst within the lymphoid tissue underneath the mucosal surface, consistent with lymphoepithelial cyst (LEC) (Fig. 8a, b). This lesion is frequently located in the floor of the mouth or at the ventro-lateral margins of the tongue and manifests clinically as a painless, soft-to-firm, yellowish-whitish nodule measuring less than 1 cm. The lymphoid tissue within the wall of LECs usually shows a follicular arrangement [1].

Fig. 8.

a A small, intramucosal cystic lesion from the ventral surface of the tongue (H&E, original magnification × 40). b The rim of lymphoid tissue, including germinal centers, is a prominent feature (H&E, original magnification × 200). This was diagnosed as a lymphoepithelial cyst. c A dilated and hyperplastic minor salivary gland duct is surrounded, and occasionally encroached, by a massive lymphocytic infiltrate. Some of the inflammatory cells have the appearance of monocytoid lymphocytes with a clear halo. These features are reminiscent of lympho-epithelial lesions (H&E, original magnification × 40). d A similar finding as in c, however, in this case the monocytoid lymphocytes invaded extensively into the salivary gland epithelium. These lymphocytes were CD20 positive (inset). Polymerase chain reaction demonstrated an IgD kappa monoclonal lymphocytic population supporting the diagnosis of extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma (H&E, original magnification × 40)

A persistent lymphocytic inflammatory process involving the oral mucosal minor salivary glands can rarely give rise to acinar atrophy and/or ductal epithelial hyperplasia (Fig. 8c). When the latter is conspicuous, the ductal lumen is no longer discerned and the ductal structures may or may not undertake an appearance of solid islands of squamous epithelium. These may appear as lympho-epithelial lesions (LELs). In those cases when the surrounding lymphocytes encroach considerably on the hyperplastic, enlarged ducts, and especially when the lymphocytes feature a monocytoid morphology, the possibility of an extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma should be suspected (Fig. 8d). Furthermore, suspicion of a MALT lymphoma is increased if the affected duct shows degenerative changes such as swelling, eosinophilia and disintegration [22]. Staining for cytokeratin or CD20 can reveal the infiltration of B lymphocytes into the ductal epithelium (Fig. 8c, inset). In addition, kappa/lambda light chain restriction on immuno-stains, would be further supportive of a diagnosis of MALT [22].

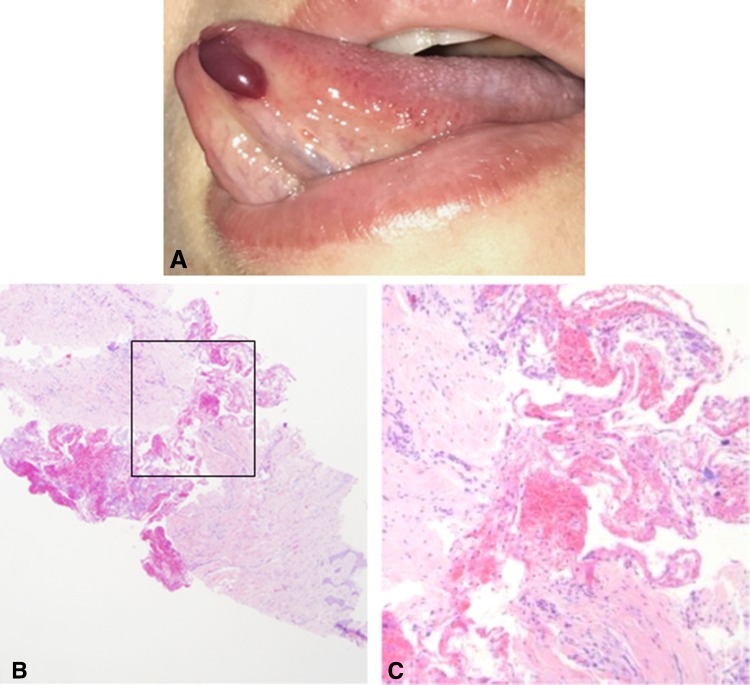

Dilemma #9: Single, Transient, Blood-Filled Vesicle: No Clinical Information—No Diagnosis

Figure 9a shows a blood-filled bulla of the tongue that upon rupturing confers a sensation of a “mouth filled with blood”. These are “hemorrhagic bulla”, also known as angina bullosa hemorrhagica (ABH) that occurs in the absence of disturbances in coagulation mechanisms or use of anti-coagulant medications [23]. The etiology is poorly understood, however a significant decrease in elastic fibers in the affected mucosae has been found, thus, suggesting the development of ABH on the background of rupture of small blood vessels due to minor trauma [23]. The diagnosis is usually based on clinical presentation and history therefore biopsy is usually unnecessary. When the diagnosis is clinically unclear and a biopsy is submitted, unless detailed clinical information is provided, microscopic findings will be nonspecific. The sub-epithelial hemorrhagic areas with some degree of inflammatory response (Fig. 9b, c) might mislead the pathologist to a diagnosis of basal-membrane-related vesiculo-bullous conditions (e.g., oral pemphigoid, linear IgA disease and others) [23]. Direct immunofluorescence, performed to examine the possibility of any of these conditions, ultimately yields no immune reactivity and ends in submitting a non-defined diagnosis. The course of ABH is self-limiting with no specific treatment [23].

Fig. 9.

a A blood-filled bulla at the anterior ventral tongue can be clinically diagnosed as angina bullosa hemorrhagica, given that there are no coagulation deficiencies or anti-coagulant medications. b Microscopically, there is lack of epithelial lining, which might lead to an erroneous diagnosis of a vesiculo-bullous disease characterized by sub-epithelial split with loss of the oral epithelium (H&E, original magnification × 40). c At a higher magnification, hemorrhagic areas can be observed (H&E, original magnification × 200)

In summary, lumps and bumps of the tongue are relatively common lesions that are usually easily diagnosed. On occasions, diagnostic dilemmas concerning these lesions can arise. We presented a series of such dilemmas; auxiliary studies, such as immunohistochemistry, PCR, direct immunofluorescence, cytogenetics can assist us in reaching an accurate diagnosis, however all these are expensive and time-consuming. There are occasions when the clinico-pathological correlations alone can help us reaching the correct diagnosis in a fast and inexpensive manner.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

Irit Allon, Marilena Vered declares, Ilana Kaplan declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Brad W, Neville DD, Chi AC, Allen CM. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, 4th edn. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. p. 34–35, 336–338, 389–391, 473–475, 497–498, 502–503, 512–514.

- 2.Awadallah M, Idle M, Patel K, Kademani D. Management update of potentially premalignant oral epithelial lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angiero F, Berenzi A, Benetti A, Rossi E, Del Sordo R, Sidoni A, Stefani M, Dessy E. Expression of p16, p53 and Ki-67 proteins in the progression of epithelial dysplasia of the oral cavity. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2535–2539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarovnaya E, Black C. Distinguishing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in mucosal biopsy specimens from the head and neck. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:e1032-6. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1032-DPHFSC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosseinpour S, Mashhadiabbas F, Ahsaie MG. Diagnostic biomarkers in oral verrucous carcinoma: a systematic review. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:19–32. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raue F, Frank-Raue K. Update on multiple endocrine neoplasia yype 2: focus on medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2:933–943. doi: 10.1210/js.2018-00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawal SY, Rawal YB. Angioleiomyoma (Vascular Leiomyoma) of the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:123–126. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0827-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vered M, Allon I, Buchner A, Dayan D. Clinico-pathologic correlations of myofibroblastic tumors of the oral cavity. II. Myofibroma and myofibromatosis of the oral soft tissues. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher C, Myofibrosarcoma Virchows Arch. 2004;445:215–223. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eyden B. The myofibroblast: a study of normal, reactive and neoplastic tissues, with an emphasis on ultrastructure. part 2—tumours and tumour-like lesions. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 2005;37:231–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato MG, Erkul E, Brewer KS, Harruff EE, Nguyen SA, Day TA. Clinical features of ectomesenchymal chondromyxoid tumors: a systematic review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2017;67:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickson BC, Antonescu CR, Argyris PP, Bilodeau EA, Bullock MJ, et al. Ectomesenchymal chondromyxoid tumor: a neoplasm characterized by recurrent RREB1-MKL2 fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1297–1305. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauzman A, Tabet JC, Stiharu TI. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e26–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Sullivan-Mejia ED, Massey HD, Faquin WC, Powers CN. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma: report of eight cases and a review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinreb I. Translocation-associated salivary gland tumors: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:367–377. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a92cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skálová A, Stenman G, Simpson RHW, Hellquist H, Slouka D, Svoboda T, Bishop JA, Hunt JL, Nibu KI, Rinaldo A, Vander Poorten V, Devaney KO, Steiner P, Ferlito A. The role of molecular testing in the differential diagnosis of salivary gland carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:e11–e27. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hisaoka M. Lipoblast: morphologic features and diagnostic value. J UOEH. 2014;1:36:115–21. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.36.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allon I, Aballo S, Dayan D, Vered M. Lipomatous tumors of the oral mucosa: histomorphological, histochemical and immunohistochemical features. Acta Histochem. 2011;113:803–809. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allon I, Vered M, Dayan D. Liposarcoma of the tongue: clinico-pathologic correlations of a possible underdiagnosed entity. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaefer IM, Hornick JL. Diagnostic immunohistochemistry for soft tissue and bone tumors: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:400–412. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Nabeshima K, Kamachi Y, Naito M. Atypical lipomatous tumor with structural rearrangements involving chromosomes 3 and 8. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3073–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacon CM, Du MQ, Dogan A. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for pathologists. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:361–372. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.031146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephenson P, Lamey PJ, Scully C, Prime SS. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica: clinical and laboratory features in 30 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:560–565. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]