Abstract

Excluding human papillomavirus (HPV)-driven conditions, oral papillary lesions consist of a variety of reactive and neoplastic conditions and, on occasion, can herald internal malignancy or be part of a syndrome. The objectives of this paper are to review the clinical and histopathological features of the most commonly encountered non-HPV papillary conditions of the oral mucosa. These include normal anatomic structures (retrocuspid papillae, lingual tonsils), reactive lesions (hairy tongue, inflammatory papillary hyperplasia), neoplastic lesions (giant cell fibroma), lesions of unknown pathogenesis (verruciform xanthoma, spongiotic gingival hyperplasia) and others associated with syndromes (for instance Cowden syndrome) or representing paraneoplastic conditions (malignant acanthosis nigricans). Common questions regarding differential diagnosis, management, and diagnostic pitfalls are addressed, stressing the importance of clinico-pathologic correlation and collaboration.

Keywords: Oral mucosa, Hairy tongue, Giant cell fibroma, Verruciform xanthoma, Malignant acanthosis nigricans, Cowden syndrome

Introduction

The oral cavity is site to various papillary mucosal entities, some of which represent normal anatomy while others are lesional. Papillary oral pathologies are a heterogenous group. Aside from human papillomavirus (HPV)-induced lesions, oral papillary lesions also consist of a variety of reactive and neoplastic conditions and, on occasion, can herald internal malignancy or be a manifestation of a syndromic condition. The objective of this article is to revisit oral conditions that appear papillary, verruciform, hairy or micronodular, while focusing uniquely on reactive and neoplastic lesions that are not associated with HPV. Common questions regarding clinical and histopathologic presentations of these lesions will be addressed. For the pathologist evaluating these lesions, the clinical information should provide key information that compliments the histopathological picture and prevents diagnostic pitfalls. From the clinician’s perspective, recognizing the causes and clinical presentations of these conditions will help guide management.

Lymphoid Hyperplasia of the Posterior-Lateral Tongue

The lateral lingual tonsils are aggregates of lymphoid tissue located bilaterally on the posterior-lateral surfaces of the tongue, related to the foliate papillae [1]. Together, the foliate papillae and these lymphoid aggregates can give a pebbly or micronodular appearance to the posterior regions of the lateral surfaces of the tongue [1]. When the lateral lingual tonsils are hypertrophic, they form clustered, nontender papules that may appear yellow or peachy when the lymphoid tissue is close to the surface; or pink-red when the tissue is deeper (Fig. 1) [2]. The cause of lingual tonsil hypertrophy (LTH) is unclear [3]. One research group found that young age, smoking and severe laryngopharyngeal acid reflux were associated with the development of LTH [3].

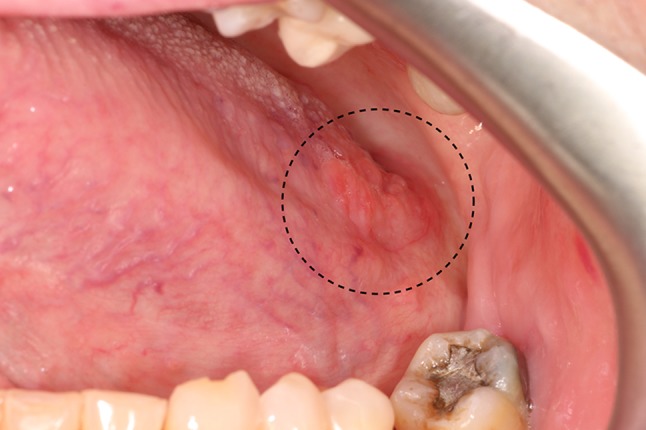

Fig. 1.

Lymphoid hyperplasia of the lateral lingual tonsils. The multinodular peach-colored tissue of the posterior lateral tongue (circle) represents hyperplastic lymphoid tissue. The color is due to the presence of lymphocytes below the surface epithelium. The tissue was soft, bilateral and symmetrical

The diagnosis of LTH can usually be made based on the clinical appearance and history. To the unexperienced examiner, the color and texture change can resemble oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [4]. However, the bilateral, symmetrical location and soft texture of this tissue should be reassuring [4]. A biopsy can be performed if there is any doubt regarding the clinical diagnosis. Histopathologically, follicular lymphoid hyperplasia is seen. This is considered a benign lymphoproliferative process [4]. Once the diagnosis of follicular lymphoid hyperplasia is confirmed, no treatment is necessary [4].

Hairy Tongue (HT)

As the name suggests, HT is a clinically hairy appearance of the dorsal surface of the tongue. The hair-like projections represent a marked elongation of the filiform papillae due to a buildup of keratin [5]. Keratin buildup can be due to decreased normal keratin desquamation or increased keratin production [6, 7]. The elongated filiform papillae are usually located on the posterior midline of the dorsal tongue. They can extend anteriorly, sparing the tip and lateral borders (Fig. 2) [4]. The filiform papillae can be white, yellow, brown, or even black, due to exogenous pigmentation from food or tobacco, pigment-producing bacteria, or certain medications [6]. Most patients are asymptomatic, however some may complain of halitosis [8], dysgeusia, the unaesthetic appearance of their tongue, or more rarely of nausea and gagging [6, 9].

Fig. 2.

The hairy appearance of the posterior dorsal surface of the tongue is caused by the elongation of the filiform papillae secondary to keratin buildup

HT is a usually transient condition associated with poor oral hygiene, a soft diet, anorexia, heavy smoking, oxidizing mouthwashes, xerostomia, antibiotics and xerostomia-inducing medications [7]. The role of Candida spp. in the pathogenesis of HT has not been conclusively demonstrated [7]. One must remember that C. albicans is part of the normal oral microflora in up to 44% of healthy individuals [10]. Some healthy carriers of Candida spp. will also present HT. In these cases, a yeast culture could render false positive results. In addition to this high rate of carriage, the antibiotics or xerostomia-causing drugs associated with development of HT can predispose the patient to developing oral candidiasis, without Candida spp. being the cause of HT [11].

Diagnosis of HT is based on the clinical appearance. In instances when a biopsy of the dorsal tongue mucosa is provided, the pathologist must remember that surgical handling of the specimen may have given it a polypoid appearance, for instance if the base of the specimen was pinched with forceps. This altered architecture of the filiform papillae-bearing mucosa could lead to the erroneous diagnosis of squamous papilloma. Attention should be taken not to confuse HT with oral hairy leukoplakia. Clinically and microscopically, both conditions appear quite different [12]. Only their names sound alike.

Treatment of HT consists of gentle debridement by regular tongue brushing complimented by tongue scraping [8], patient reassurance regarding the benign and transient nature of the condition [7] and modification of chronic predisposing factors [6]. The return to a solid food diet will also improve the appearance of the tongue for some patients.

Inflammatory Papillary Hyperplasia (IPH)

IPH is a reactive tissue overgrowth that typically develops on the denture-bearing hard palate [13, 14]. Factors implicated in the etiopathology include candidiasis, poor oral hygiene, an ill-fitting or old denture, smoking, old age, continuous and nighttime wear of a denture [14–16]. IPH has been considered part of the spectrum of denture stomatitis (Newton’s classification type III) [17]. Clinically, the hard palate mucosa appears hyperemic and covered in small, painless, nodular or papillary growths. These changes usually begin on the palatal vault but can extend to involve the entire hard palate [4]. The degree of inflammation is variable (Fig. 3a) [13]. IPF can also be seen in dentate patients with a deep palatal vault or who breathe with their mouths [4, 16]. IPH is usually asymptomatic and most patients are unaware of its presence [13].

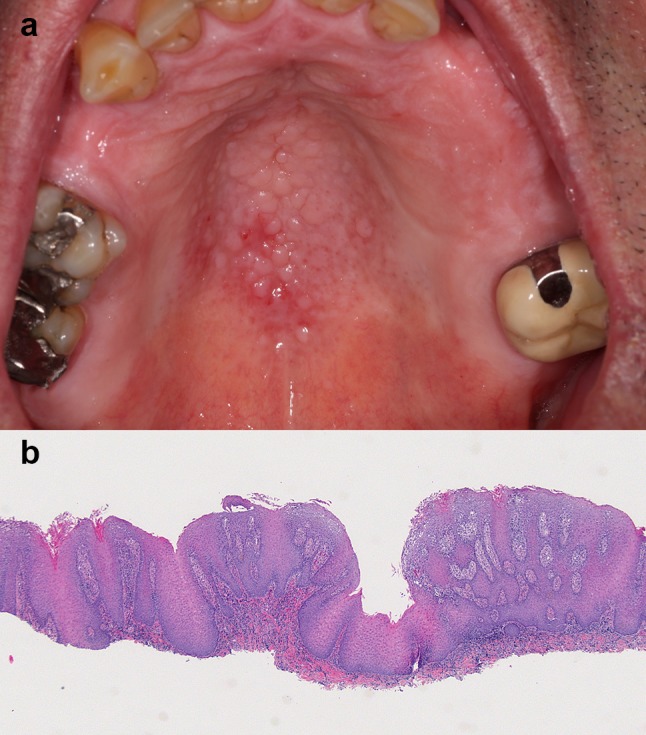

Fig. 3.

a The palatal vault is covered by small fibrous papules representing inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. b Low-power view showing fibrous and epithelial hyperplasia resulting in papillary surface projections. A chronic inflammatory infiltrate is present in the superficial connective tissue and extends into the epithelium. Periodic acid Schiff staining revealed the presence of fungal hyphae in the keratin layer, compatible with Candida spp. (original magnification × 25, Hematoxylin & eosin)

The diagnosis of IPH is based on the clinical appearance of the mucosa. A biopsy is rarely indicated. When tissue is submitted, papillary projections are seen, surfaced by nonkeratotic or parakeratotic stratified squamous epithelium [18]. The epithelium alternates between areas of atrophy and acanthosis extending deep within the lamina propria [18]. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be present, which should not be mistaken for a well-differentiated OSCC [4, 19]. The lamina propria can be edematous or fibrotic, and supports a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Fig. 3b) [4]. Candidal hyphae are seldom identified, since they are mostly located on the tissue-bearing surface of the denture [19].

Management of IPH consists of providing patient education regarding denture wear and hygiene, improving denture fit, fabricating new dentures, and treating fungal infection [17]. Once the sources of inflammation have been removed, the erythema and edema resolve, but the papillary appearance of the mucosa may not completely disappear [16]. In cases where persisting fibrous tissue obstructs the proper fitting of a maxillary denture, the excess tissue can be surgically removed [18]. In most situations, however, IPH requires no further treatment once the inflammation has reduced [13].

Giant Cell Fibroma (GCF)

GCF is a benign fibrous tumor with distinct clinical and pathological features [20]. Unlike a traumatic fibroma, it is not induced by chronic low-grade trauma. GCF represents approximately 4.7% of all oral benign fibrous growths submitted for biopsy [20]. The lesion predominantly affects Caucasians, has a slight female predilection, and a peak incidence in the second decade of life. In a study of 434 cases, 60% occurred before the age of 30 [20].

GCF presents as a small, asymptomatic, pale pink, pedunculated or sessile fibrous nodule. Most lesions measure less than 1 cm in diameter and have limited growth potential - the average size being 4 mm [20]. The gingiva, tongue, palate, buccal mucosa and lip are the sites of predilection [20]. The lesion can be present for years before being noticed by the patient. The surface of the lesion can be smooth and dome-shaped, finely bosselated or papillary (Fig. 4a). Smooth lesions will inspire a clinical differential diagnosis including traumatic fibroma, peripheral ossifying fibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and peripheral giant cell granuloma [20]. Papillary lesions often lead to a clinical diagnosis of squamous papilloma or verruca vulgaris [20].

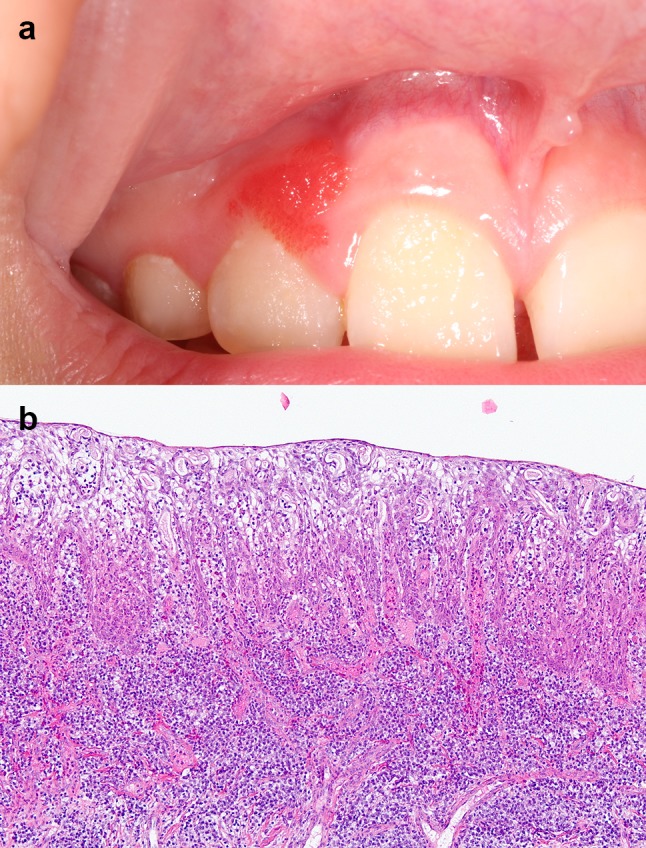

Fig. 4.

a GCF of the mandibular facial gingiva presenting as a pale pink sessile nodule with a pebbly surface. b Low-power view of a GCF. The pedunculated, bosselated, polypoid nodule is composed of fibrous connective tissue and orthokeratotic stratified squamous epithelium. Note: the elongated, pointed rete ridges (original magnification × 25, Hematoxylin & eosin). c High-power view of the papillary chorion in a GCF. Note: the presence of multiple plump, stellate-shaped multinuclated fibroblasts (original magnification × 200, Hematoxylin & eosin)

Histopathologically, GCF presents as a nodular mass with a smooth or pebbly surface [20]. The body of the nodule is composed of fibro-vascular connective tissue surfaced by a thin keratotic stratified squamous epithelium [20]. The rete ridges are often elongated and narrow (Fig. 4b). The distinguishing characteristic is the presence of multiple plump, stellate, bi- or multinucleated fibroblasts in the superficial connective tissue (Fig. 4c) [20, 21]. Melanin incontinence and melanophages are occasionally present below the basement membrane [22]. Other lesions involving the skin and mucous membranes have a similar microscopic appearance. These include the fibrous papule of the nose, ungual fibroma, acral fibrokeratoma and fibroblastoma [20]. Mucosal lesions include the retrocuspid papillae (RCP) (discussed below) and pearly penile papules [20].

A conservative excision is usually curative. Recurrences have been documented but are rare [20].

Retrocuspid Papillae (RCP)

RCP are small, sessile, pink papules, with or without a papillary surface, located on the gingiva lingual to the mandibular cuspids [23]. RCP are asymptomatic, often bilateral and measure < 5 mm in diameter (Fig. 5). They have been reported in 11%–99% of children and young adults under 20 years of age [23]. This prevalence decreases to approximately 8% by the 5th decade of life, which supports the idea that RCP represent a normal anatomic structure that regresses with age [23]. Once recognized, no treatment is indicated [24].

Fig. 5.

RCP presenting as bilateral sessile papules on the gingiva lingual to the mandibular canines (circles)

The clinical significance of RCPs is that they may mimic gingival growths, from which they must be distinguished to avoid unnecessary biopsy [23, 24]. Since they are microscopically similar to GCF, the proper diagnosis requires clinico-pathologic correlation.

Spongiotic Gingival Hyperplasia (SGH)

SGH is a distinctive subtype of gingival hyperplasia with characteristic clinical and histological features. The first cases were published in 2007 and 2008 under the names juvenile spongiotic gingivitis [25] and localized juvenile SGH [26], respectively. Recent cases have been reported in adults and with a multifocal distribution, which argues against the designations “localized” and “juvenile” [27]. The exact cause remains unknown [27]. SGH does not seem to be related to trauma, hormonal changes of puberty, accumulation of dental plaque or calculus, or foreign body integration [25–27]. Immunohistochemical studies have shown that SGH could represent exteriorized or ectopic junctional epithelium of the gingiva that has become hyperplastic in response to inflammation, thus implying a developmental etiology [25, 28].

The classic presentation is a bright red, slightly papillary/granular/velvety, well-demarcated, painless but easily-bleeding gingival overgrowth located on the facial gingiva of the anterior teeth (Fig. 6a) [25, 26]. The maxillary gingiva is affected five times more frequently than the mandible [25]. SGH can involve the marginal gingiva, attached gingiva and the interdental papillae [25, 26]. The majority of lesions are single, localized and measure less than 1 cm in diameter [25–27, 29]. They can be present several months to a few years before diagnosis [25, 27, 29]. A slight female predilection is often reported [25, 26, 29]. The mean age at presentation is approximately 12 years, but SGH can be identified anytime from childhood to adulthood [25, 26, 29]. Up to 82% of reported cases are in Caucasians [26, 29].

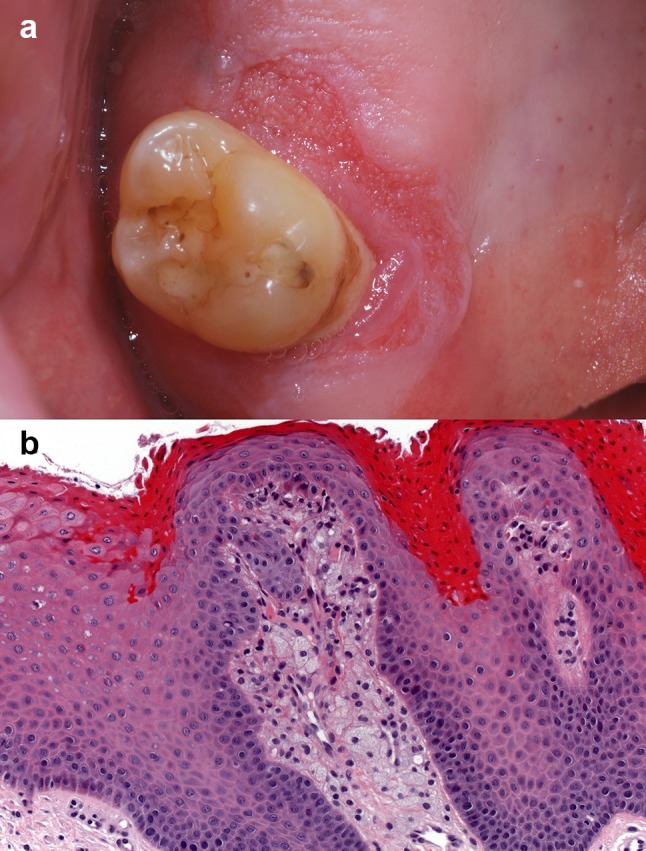

Fig. 6.

a SGH presenting as a localized bright red papillary growth of the facial maxillary gingiva in a 9-year-old female. b Medium-power view of SGH in a 33-year-old male. This lesion of recent onset lacks a papillary architecture, but shows epithelial hyperplasia, spongiosis, an absent keratin layer, neutrophilic exocytosis, and a dense chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the connective tissue (original magnification × 100, Hematoxylin & eosin)

Microscopically, well-formed SGH presents as a papillary nodule surfaced by non-keratinized, variably acanthotic, spongiotic stratified squamous epithelium with elongated rete ridges [25, 26]. Neutrophilic exocytosis within the epithelium is prominent [26]. The papillary projections are supported by loose fibro-vascular connective tissue with atrophic overlying epithelium. The connective tissue papillae show vasodilation, congestion and support a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting mostly of lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils [26]. In the initial stages, lesions appear flat and less hyperplastic, but many of the other characteristic histologic features are present (Fig. 6b) [25]. HPV is not implicated in the development of this lesion [29]. All cell layers of the lesional epithelium tend to be cytokeratin (CK) 19 and CK 8/18 positive [27, 28].

The appropriate treatment for SGH remains unknown. Since most published cases were excised, little is known on the natural history of the lesion. Recurrence rates between 6% and 28% have been reported for solitary lesions [25, 26, 29], and 38.5% for multifocal lesions [27]. Spontaneous regression after a period of 15 months has been well documented [27]. This could explain the rare occurrence in adults when compared to the significant predilection in children.

Verruciform Xanthoma (VX)

VX is an uncommon benign mucocutaneous lesion of unknown etiology [30], characterized by the presence of numerous lipid-laden histiocytes below the epithelium [31]. The oral cavity is the site of predilection, but genital lesions have also been reported [32]. Case series with more than ten patients have shown a slight male predilection and an average age at diagnosis between 45 and 53 years [30]. Several etiologic factors have been proposed, including trauma, inflammation, an altered immunological response, epithelial degeneration and lipid accumulation [30]. Contrary to other dermal xanthomas (such as xanthelasma palpebrarum) that can signalize dyslipidemia, atherothrombotic disease or type II diabetes [33], there is no such association with VX. Interestingly, VX is part of CHILD syndrome, a trait caused by mutations in the NSDHL gene involved in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway [34]. Although VX is a papillary lesion, HPV has only been detected in a few instances and no definitive viral cause has been recognized [35].

VX appears as a well-demarcated, painless, slow-growing, plaque or nodule with a verrucous or granular surface [32]. The color can range from yellow, pink, white or red (Fig. 7) [30, 32]. The size of the lesion rarely exceeds 2 cm in diameter [30, 32]. The majority of cases occur on the masticatory mucosa (attached gingiva and hard palate). Other oral mucosal sites are less commonly affected [30]. Clinically, VX is often mistaken for a squamous papilloma, verruca vulgaris, condyloma, leukoplakia and occasionally for early verrucous carcinoma or OSCC [30, 32]. Most lesions are excised and diagnosed microscopically.

Fig. 7.

a VX presenting as a red plaque with a granular surface on the gingiva mesio-palatal to a maxillary molar. (Courtesy of Dr. Benoît Lalonde). b High-power view of a VX demonstrating the collections of foamy macrophages in the connective tissue papillae, papillomatosis and orange hyperparakeratosis (original magnification × 200, Hematoxylin & eosin) (Courtesy of Dr. Adel Kauzman)

The histological features of VX are similar for all lesions [32]. They include a papillary proliferation of stratified squamous epithelium associated with hyperparakeratosis. The thick parakeratin layer tends to have a noticeable salmon or orange color when stained with hematoxylin and eosin [30] and extends into the epithelial crypts to form parakeratin plugs [30, 31]. The rete ridges are uniformly elongated [31]. The outstanding characteristic feature of VX is the presence of numerous foamy lipid-laden histiocytes (xanthoma-like cells) within the connective tissue papillae. These foamy cells do not extend below the tips of the rete ridges [31]. They show cytoplasmic immunopositivity for CD69, CD63 and CD163 [30]. A moderate chronic inflammatory infiltrate is dispersed in the underlying connective tissue [30].

VX is treated by conservative surgical excision. The prognosis is excellent [30]. There are no reports of VX undergoing malignant transformation.

Syndromes and Skin Disorders Presenting with Oral Papillary Lesions

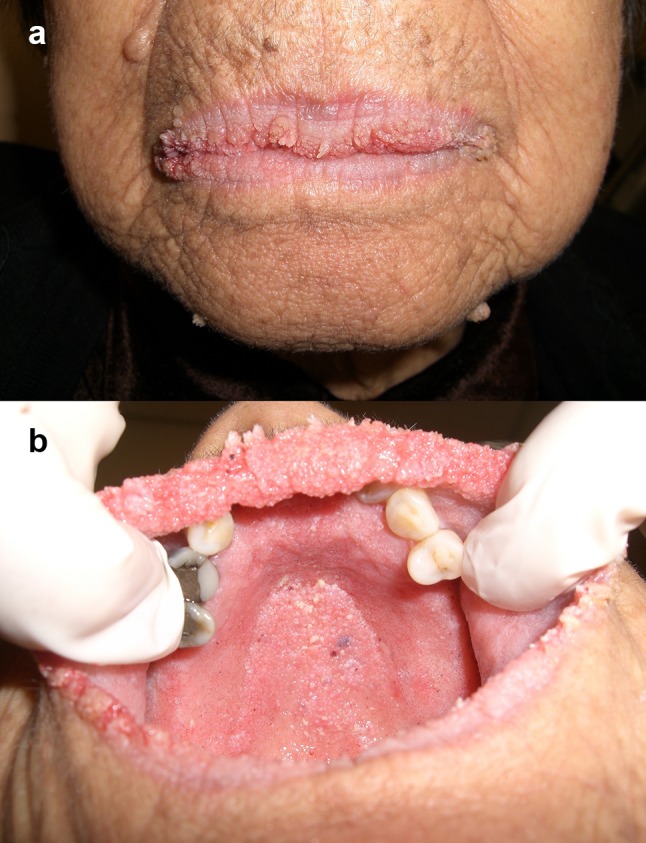

Oral papillomatosis is part of a variety of skin disorders and syndromes (Table 1). The development of multiple sessile papillomatous, white–pink, coalescent papules on the keratinized and non-keratinized oral mucosa can be an early clue toward diagnosis of multiple hamartoma syndrome [36]. The sudden onset of florid papillomatosis of the lips, labial commissures or oral mucosa is characteristic of acanthosis nigricans, a paraneoplastic condition associated with gastrointestinal malignancy (Fig. 8a, b) [37, 38]. Oral papillary lesions arranged linearly, distributed unilaterally or along the midline (following Blaschko’s lines) are a feature of linear epidermal nevus [39, 40], sebaceous nevus syndrome [41–43] and focal dermal hypoplasia [44, 45]. Perioral papillomatosis has been reported in patients with ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome [46, 47] and Costello syndrome [48]. For a complete discussion of the reported oral anomalies and other manifestations that characterize each syndrome, please refer to the references included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Syndromes and skin disorders associated with oral papillomatosis

| Name(s) | Gene mutation | Prevalence | Reported oral anomalies | Other associated manifestations | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple hamartoma syndrome (PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome, Cowden syndrome) |

PTEN gene | 1 in 2,50,000 | Multiple gingival and mucosal papillary papules | Facial trichilemmomas, acral (palmoplantar) keratosis. Cutaneous hemangiomas, xanthomas, lipomas and neuromas. Colorectal, mammary, thyroidal and genitourinary cancers | [36] |

| Linear epidermal nevus | FGFR3 and PIC3CA genes (in 40% of cases) [49] | 1 in 1000 | Unilateral/midline papules/nodules with a papillary/verrucous surface. Lesions do not cross the midline and have been found on the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate and gingiva. One or more hypoplastic or congenitally missing teeth | Tan or brown verrucous papules (keratinocytic epidermal nevi), arranged linearly following Blaschko’s lines. Present at birth or during childhood, grows slowly until adolescence Localized lesions (nevus unius lateris) = confined to one side of body Diffuse (ichthiosis hystrix) = extensive bilateral lesions |

[39, 40] |

| Sebaceous nevus syndrome (Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome) |

HRAS gene [49] | Unknown | Unilateral, focal or linear papillomatous growths of the lips, tongue, gingiva, palate or buccal mucosa, extending from the adjacent skin. Anodontia and hypoplastic teeth | Sebaceous nevus following Blaschko’s lines of the head and neck, mental retardation, seizures, hemiparesis, eyelid colobomas | [41–43] |

| Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome) |

PORCN gene | Unknown | Intraoral papilloma or papillary gingival hyperplasia. Intraoral lipoma. Vertical enamel grooving, peg shaped teeth, enamel hypoplasia. Cleft lip and cleft palate | Thinning of the skin, herniation of adipose tissue, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation following Blaschko’s lines, abnormalities of the eyes, nervous, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, reproductive and musculoskeletal systems | [44, 45] |

| Ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome | p63 gene | Unknown | Cleft lip/cleft palate, perioral papillomatosis involving lips, commissures, and occasionally the buccal mucosa, hypodontia, microdontia, enamel hypoplasia | Ectrodactyly, syndactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, tear duct anomalies, genitourinary anomalies, deafness | [46, 47] |

| Costello syndrome | HRAS gene | From 1 in 3,00,000 to 1 in 1.25 million [50] | Verrucous lesions arranged in plaques around the mouth and nares | Delayed development and delayed mental progression, distinctive facial features, short stature, redundant skin of neck, palms, soles, fingers, hyperflexible joints and curly hair | [48] |

| Acanthosis nigricans (AN) | Acquired condition | Varies with underlying cause and geographical region | Diffuse, finely papillary lesional areas most often involving the lips, labial commissures, palate, buccal mucosa, and tongue. Minimal or no melanin pigmentation | Finely papillary, keratotic, brown, asymptomatic patches affecting the flexural surfaces of the skin Malignant AN: associated with gastro-intestinal or genito-urinary carcinoma Benign AN: associated with obesity, diabetes, endocrinopathies, medications |

[37, 38] |

Fig. 8.

a Malignant acanthosis nigricans affecting the vermilion and commissures of the lips. A gastric carcinoma was discovered following the development of florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis (Courtesy of Dr. Hagen B. E. Klieb). b Same patient as a. Note: the florid papillomatous lesions on the hard palate, alveolar ridge and upper labial mucosa. This patient’s case history was published in reference [38] (Courtesy of Dr. Hagen B. E. Klieb)

Conclusion

Oral mucosal lesions with a papillary architecture readily bring to mind HPV-related conditions. However, papillary lesions also include a variety of developmental, reactive and neoplastic conditions not driven by HPV infection. In this review, attention was placed on prevalent lesions that could be encountered in everyday clinical or laboratory practice of oral pathology. Clinicians are reminded that oral papillomatosis is a component of a variety of syndromes and, on occasion, can be a paraneoplastic condition. Rare conditions (for example oral condylomata lata of secondary syphilis [51], sialadenoma papilliferum and inverted ductal papilloma) were not discussed, but may be considered in the appropriate clinical setting. In addition, dysplastic and malignant oral verrucous or papillary lesions, notably proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, verrucous carcinoma and papillary OSCC, were excluded since a lack of consensus exists on the role of HPV in these lesions [52]. As in many situations in medical care, clinico-pathologic correlation and collaboration is often essential to achieving the proper diagnosis. Clinicians and pathologists profit from each other’s complimentary knowledge, ultimately to the patient’s benefit.

Conflict of interest

Gisele N. Mainville declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Madani FM, Kuperstein AS. Normal variations of oral anatomy and common oral soft tissue lesions: evaluation and management. Med Clin N Am. 2014;98(6):1281–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoopler ET, Ojeda D, Elmuradi S, Sollecito TP. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the tongue. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(3):e155-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang MS, Salapatas AM, Yalamanchali S, Joseph NJ, Friedman M. Factors associated with hypertrophy of the lingual tonsils. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(5):851–855. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nanci A. Chapter 12 oral mucosa. Ten cate’s oral histology: development, structure, and function. 8. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2013. pp. 278–301. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonsalves WC, Chi AC, Neville BW. Common oral lesions: Part I. Superficial mucosal lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson DF, Kessler TL. Drug-induced black hairy tongue. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(6):585–593. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Sleen MI, Slot DE, Van Trijffel E, Winkel EG, Van der Weijden GA. Effectiveness of mechanical tongue cleaning on breath odour and tongue coating: a systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8(4):258–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2010.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(31):10845–10850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendorf TM, Walker DM. The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(80)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsakal A, Mangat L. Images in clinical medicine. Lingua villosa nigra. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(23):2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm065655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winzer M, Gilliar U, Ackerman AB. Hairy lesions of the oral cavity. Clinical and histopathologic differentiation of hairy leukoplakia from hairy tongue. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10(2):155–159. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198804000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger RL. The etiology of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. J Prosthet Dent. 1975;34(3):254–261. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(75)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gual-Vaques P, Jane-Salas E, Egido-Moreno S, Ayuso-Montero R, Mari-Roig A, Lopez-Lopez J. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22(1):e36–e42. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker KM, Heget HS. The incidence of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. J Am Dent Assoc. 1939;93(3):610–613. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1976.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gual-Vaques P, Jane-Salas E, Mari-Roig A, Lopez-Lopez J. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia in a non-denture-wearing patient: a case history report. Int J Prosthodont. 2017;30(1):80–82. doi: 10.11607/ijp.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arendorf TM, Walker DM. Denture stomatitis: a review. J Oral Rehabil. 1987;14(3):217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1987.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergendal T, Heimdahl A, Isacsson G. Surgery in the treatment of denture-related inflammatory papillary hyperplasia of the plate. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9(4):312–319. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan I, Vered M, Moskona D, Buchner A, Dayan D. An immunohistochemical study of p53 and PCNA in inflammatory papillary hyperplasia of the palate: a dilemma of interpretation. Oral Dis. 1998;4(3):194–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1998.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houston GD. The giant cell fibroma. A review of 464 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53(6):582–587. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souza LB, Andrade ES, Miguel MC, Freitas RA, Pinto LP. Origin of stellate giant cells in oral fibrous lesions determined by immunohistochemical expression of vimentin, HHF-35, CD68 and factor XIIIa. Pathology. 2004;36(4):316–320. doi: 10.1080/00313020410001721627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulkarni S, Chandrashekar C, Kudva R, Radhakrishnan R. Giant-cell fibroma: understanding the nature of the melanin-laden cells. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21(3):429–433. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_209_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brannon RB, Pousson RR. The retrocuspid papillae: a clinical evaluation of 51 cases. J Dent Hyg. 2003;77(3):180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Hansen LS, Leider AS. The retrocuspid papilla of the mandibular lingual gingiva. J Periodontol. 1990;61(9):585–589. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.9.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darling MR, Daley TD, Wilson A, Wysocki GP. Juvenile spongiotic gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1235–1240. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang JY, Kessler HP, Wright JM. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siamantas I, Kalogirou EM, Tosios KI, Fourmousis I, Sklavounou A. Spongiotic gingival hyperplasia synchronously involving multiple sites: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0903-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allon I, Lammert KM, Iwase R, Spears R, Wright JM, Naidu A. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia possibly originates from the junctional gingival epithelium-an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology. 2016;68(4):549–555. doi: 10.1111/his.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argyris PP, Nelson AC, Papanakou S, Merkourea S, Tosios KI, Koutlas IG. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia featuring unusual p16INK4A labeling and negative human papillomavirus status by polymerase chain reaction. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/jop.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Andrade BA, Agostini M, Pires FR, Rumayor A, Carlos R, de Almeida OP, et al. Oral verruciform xanthoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42(7):489–495. doi: 10.1111/cup.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shafer WG. Verruciform xanthoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;31(6):784–789. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(71)90134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira PT, Jaeger RG, Cabral LA, Carvalho YR, Costa AL, Jaeger MM. Verruciform xanthoma of the oral mucosa. Report of four cases and a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(3):326–331. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky. Olomouc Czechoslov. 2014;158(2):181–188. doi: 10.5507/bp.2014.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bittar M, Happle R. CHILD syndrome avant la lettre. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(2 Suppl):34-7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)01827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohwedder A, Murphy M, Carlson JA. HPV in verruciform xanthoma–sensitivity and specificity of detection methods and multiplicity of HPV types affect results. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30(3):219–220. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elo JA, Sun HH, Laudenbach JM, Singh HM. Multiple oral mucosal hamartomas in a 34-year old female. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(3):393–398. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada Y, Iwabuchi H, Yamada M, Kobayashi D, Uchiyama K, Fujibayashi T. A case of acanthosis nigricans identified by multiple oral papillomas with gastric adenocarcinoma. As J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;22(3):154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, Sade S, Enepekides D. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(13):e218-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown HM, Gorlin RJ. Oral mucosal involvement in nevus unius lateris (ichthyosis hystrix) Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:509–515. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1960.03730040013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haberland-Carrodeguas C, Allen CM, Lovas JG, Hicks J, Flaitz CM, Carlos R, et al. Review of linear epidermal nevus with oral mucosal involvement-series of five new cases. Oral Dis. 2008;14(2):131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warnke PH, Russo PA, Schimmelpenning GW, Happle R, Harle F, Hauschild A, et al. Linear intraoral lesions in the sebaceous nevus syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2 Suppl 1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warnke PH, Schimmelpenning GW, Happle R, Springer IN, Hauschild A, Wiltfang J, et al. Intraoral lesions associated with sebaceous nevus syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(2):175–180. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichart PA, Lubach D, Becker J. Gingival manifestation in linear nevus sebaceous syndrome. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12(6):437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greer RO, Jr, Reissner MW. Focal dermal hypoplasia. Current concepts and differential diagnosis. J Periodontol. 1989;60(6):330–335. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.6.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright JT, Puranik CP, Farrington F. Oral phenotype and variation in focal dermal hypoplasia. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2016;172c(1):52–58. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandes B, Ruas E, Machado A, Figueiredo A. Ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome (EEC): report of a case with perioral papillomatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19(4):330–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansur AT, Aydingoz IE, Kocaayan N. A case of EEC syndrome with peri/intraoral papillomatosis and widespread freckling. J Dermatol. 2006;33(3):225–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Der Kaloustian VM, Moroz B, McIntosh N, Watters AK, Blaichman S. Costello syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1991;41(1):69–73. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genetics Home Reference—Epidermal Nevus. NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrived from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/epidermal-nevus#. Accessed 12 Sep 2018.

- 50.Genetics Home Reference—Costello Syndrome. NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrived from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/costello-syndrome#genes. Accessed 12 Sep 2018.

- 51.de Swaan B, Tjiam KH, Vuzevski VD, Van Joost T, Stolz E. Solitary oral condylomata lata in a patient with secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1985;12(4):238–240. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198510000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stokes A, Guerra E, Bible J, Halligan E, Orchard G, Odell E, et al. Human papillomavirus detection in dysplastic and malignant oral verrucous lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(3):283–286. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]