Abstract

Objective:

We estimate associations between emergency department (ED) diagnoses and suicide among youth to guide ED care.

Method:

This ED-based case-control study used data from the Office of the Chief Coroner and all EDs in Ontario, Canada. Cases (n = 697 males and n = 327 females) were aged 10 to 25 years who died by suicide in Ontario between April 2003 and March 2014, with an ED contact in the year before their death. Same-aged ED-based controls were selected during this time frame. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results:

Among youth diagnosed with a mental health problem at their most recent ED contact (41.9% cases, 5% controls), suicide was elevated among nonfatal self-inflicted: ‘other’ injuries, including hanging, strangulation, and suffocation in both sexes (aORs > 14); cut/pierce injuries in males (aOR > 5); poisonings in both sexes (aORs > 2.2); and mood and psychotic disorders in males (aORs > 1.7). Among those remaining, ‘undetermined’ injuries and poisonings in both sexes (aORs > 5), ‘unintentional’ poisonings in males (aOR = 2.1), and assault in both sexes (aORs > 1.8) were significant. At least half of cases had ED contact within 106 days.

Conclusions:

The results highlight the need for timely identification and treatment of mental health problems. Among those with an identified mental health problem, important targets for suicide prevention efforts are youth with self-harm and males with mood and psychotic disorders. Among others, youth with unintentional poisonings, undetermined events, and assaults should raise concern.

Keywords: suicide, risk factors, diagnoses, emergency health services, adolescent, sex distribution

Abstract

Objectif :

Nous estimons les associations entre les diagnostics du service d’urgence (SU) et le suicide chez les adolescents afin de guider les soins des SU.

Méthode :

Cette étude cas-témoin, basée dans les SU, a utilisé des données du Bureau du coroner en chef et de tous les SU de l’Ontario, au Canada. Les cas (n = 697 garçons et n = 327 filles), âgés entre 10 et 25 ans, sont décédés par suicide en Ontario entre avril 2003 et mars 2014, et avaient eu un contact avec un SU dans l’année précédant leur décès. Des témoins du même âge basés dans les SU ont été sélectionnés durant la même période. Des rapports de cotes bruts et ajustés (RCa) et des intervalles de confiance à 95% ont été calculés.

Résultats :

Chez les adolescents ayant reçu un diagnostic de problème de santé mentale lors de leur visite la plus récente au SU (41,9% des cas, 5% des témoins), le suicide était élevé parmi des blessures non fatales auto-infligées: « d’autres » blessures, y compris la pendaison, la strangulation et la suffocation chez les 2 sexes (RCa > 14); des blessures par coupure/perçage chez les garçons (RCa > 5), l’empoisonnement chez les 2 sexes (RCa > 2,2) et des troubles de l’humeur et psychotiques chez les garçons (RCa > 1,7). Parmi ceux qui restent, des blessures « indéterminées » et l’empoisonnement chez les 2 sexes (RCa > 5); des empoisonnements « involontaires » chez les garçons (RCa: 2,1) et l’agression chez les 2 sexes (RCa > 1,8) étaient significatifs. Au moins la moitié des cas a eu un contact avec un SU dans les 106 jours précédents.

Conclusions :

Les résultats soulignent le besoin d’une identification et d’un traitement en temps opportun des problèmes de santé mentale. Pour ceux chez qui un problème de santé mentale a été identifié, les initiatives de prévention du suicide peuvent d’abord cibler les adolescents qui s’automutilent et les garçons souffrant de troubles de l’humeur et psychotiques. Chez les autres, les adolescents qui ont des empoisonnements involontaires, des événements indéterminés et des agressions devraient susciter des inquiétudes.

The emergency department (ED) is a focus for suicide prevention policy and research.1–4 Population-based studies confirm adults who later died by suicide were distinguished from their peers by their greater ED and inpatient mental health care contact.5–7 This was recently verified for youth aged 10 to 25 years.8 In total, 48% of youth who died by suicide were seen in the ED and/or inpatient setting (32% for mental health and 16% for other reasons), mainly the ED, in the year before their death. Increased rates of ED mental health visits among youth in the past decade make the development and piloting of ED-based preventive interventions targeting youth particularly important.9,10

Among youth diagnosed with a mental health problem in the ED, it is unclear which problems carry a higher risk for suicide. Hospital-based suicide prevention efforts have often focused on those with suicidal ideation, attempts, or self-harm (irrespective of intent), typically more frequent in females than males.11–13 While these youth are at a higher risk for suicide,14–17 the predictive value of other ED mental health problems18 merits attention to guide ED-based care.19 Furthermore, little is known about the suicide risk among the youth who account for the majority of ED contacts—those not diagnosed with a mental health problem.

To inform future suicide prevention efforts, we conducted a population-based case-control study to estimate the associations, separately for males and females, between specific ED diagnoses documented at the most recent contact and suicide among youth with or without a mental health problem.

Methods

Study Sample and Data Collection

This study builds on our prior research.8,18,20 Decedents were youth (aged 10 to 25) who died by suicide in Ontario, Canada, between April 2003 and March 2014, inclusive. Decedents were individually linked to their administrative health care records in the year prior to their death8 and cases identified as having an ED contact in the year before their death through the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS)21 after exclusion of health care contact(s), related to their death (e.g., dead or died on arrival). Live controls (ages 10 to 25) with an ED contact in NACRS during the study years were selected for comparison.

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board and the Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada’s Research Ethics Board.

Study Measures

We measured the following characteristics: age, sex, neighbourhood income, and community size.

Type of ED contact: In Ontario EDs, a physician diagnosis is a mandatory field in NACRS with up to 9 additional fields recorded. The most recent ED contact was chosen to reflect all cumulative information available up to that date to guide care and classified as follows:

A mental health problem: presence of a mental disorder and/or) self-harm: a self-inflicted injury or poisoning. Types of mental disorders were alcohol, other substance, schizophrenia/schizotypal/delusional, mood, anxiety, or all other mental disorders. Self-harm was specified by method: self-poisoning; cut/pierce, or an ‘other’ injury. Youth diagnosed with both a mental health problem and an ‘other’ (non–mental health) problem were also categorized.

An ‘other’ health problem only: where no mental health problem was recorded. The presence of injuries and poisonings that were not self-inflicted—an unintentional injury or poisoning, assault, or event of undetermined intent was specified.17

The most recent ED contact was also described by its timing, acuity, and prior medical care in the form of a recent mental health contact (past 30 days) or a prior ED contact for any reason (past year).

Days to death: Among cases, we counted the number of days from the most recent ED contact to their death.

Supplemental Table S1 provides a fuller description of study measures.

Statistical Analyses

Cases and controls were described and then stratified by type of ED contact and sex for subsequent analyses. Youth with missing data, about 1% in each subgroup, were excluded to ensure consistent comparisons. Differences between cases and controls were tabulated and tested using chi-square statistics. Among cases, we depicted the days to death by the mean, the 25th percentile, 50th percentile (median), and 75th percentile. To estimate associations between specific ED diagnoses and suicide, we conducted 4 logistic regressions stratified by type of ED contact and sex. We examined crude and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Post hoc differences by sex were identified by nonoverlapping CIs.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 1024 (n = 697 males; n = 327 females) cases and over 2 million controls (n = 1,318,145 males; n = 1,217,608 females) were identified. At the most recent ED contact, fewer than half of cases (n = 273 [39.2%] males; n = 156 [47.7%] females) were diagnosed with a mental health problem compared to an ‘other’ health problem only (424 males [60.8%]; 171 females [52.3%]). In contrast, 95% of controls (n = 1,252,102 males; n = 1,156,218 females) were diagnosed with an ‘other’ health problem only. Notably, less than 5% of subjects were diagnosed with both a mental health problem and an ‘other’ health problem: male cases (n = 28, 4.0%) and controls (n = 9645, 0.7%); female cases (n = 9, 2.8%) and controls (n = 6874, 0.6%).

With some exceptions (Tables 1 and 2), cases were older than controls and more likely to live in rural areas and lower-income neighbourhoods. For cases, the most recent ED contact was of higher acuity and preceded by more medical care but was less likely to occur in the latter 2 study years. Cases also differed from controls on the weekday and month of this contact among females with a mental health problem (Table 1) and on registration after midnight among males without a mental health problem (Table 2).

Table 1.

Youth Diagnosed with a Mental Health Problem at Most Recent Emergency Department Contact.

| Variable | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 269),a n (%) | Controls (n = 65,137),a n (%) | χ2 | P Value | Cases (n = 151),a n (%) | Controls (n = 60,527),a n (%) | χ2 | P Value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 10 to 15 | 11 (4.1) | 8254 (12.7) | 19.55 | <0.001 | 19 (12.6) | 10,921 (18.0) | 7.71 | 0.021 |

| 16 to 17 | 28 (10.4) | 7672 (11.8) | 2 df | 15 (9.9) | 9144 (15.1) | 2 df | ||

| 18 to 25 | 230 (85.5) | 49,211 (75.5) | 117 (77.5) | 40,462 (66.8) | ||||

| Community size | ||||||||

| ≥1,500,000 | 82 (30.5) | 24,156 (37.1) | 15.19 | <0.001 | 52 (34.4) | 23,390 (38.6) | 3.11 | 0.212 |

| 10,000 to 1,499,000 | 141 (52.4) | 34,279 (52.6) | 2 df | 79 (52.3) | 31,466 (52.0) | 2 df | ||

| Rural <10,000 | 46 (17.1) | 6702 (10.3) | 20 (13.2) | 5671 (9.4) | ||||

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||||||

| Lowest (Q1) | 80 (29.7) | 15,460 (23.7) | 5.33 | 0.021 | 43 (28.5) | 14,027 (23.2) | 2.38 | 0.123 |

| Higher (Q2-Q5) | 189 (70.3) | 49,677 (76.3) | 1 df | 108 (71.5) | 46,500 (76.8) | 1 df | ||

| Most recent ED contact: registration time | ||||||||

| 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. | 103 (38.3) | 23,828 (36.6) | 4.48 | 0.106 | 57 (37.7) | 23,022 (38.0) | 3.43 | 0.18 |

| 5 p.m. to midnight | 98 (36.4) | 21,074 (32.4) | 2 df | 61 (40.4) | 20,783 (34.3) | 2 df | ||

| After midnight, before 9 a.m. | 68 (25.3) | 20,235 (31.1) | 33 (21.9) | 16,722 (27.6) | ||||

| Day of week | ||||||||

| Weekday | 167 (62.1) | 38,427 (59.0) | 1.06 | 0.304 | 106 (70.2) | 37,273 (61.6) | 4.73 | 0.03 |

| Weekend | 102 (37.9) | 26,710 (41.0) | 1 df | 45 (29.8) | 23,254 (38.4) | 1 df | ||

| Month | ||||||||

| January | 23 (8.6) | 6026 (9.3) | 10.83 | 0.371 | 16 (10.6) | 5754 (9.5) | 19.58 | 0.034 |

| February | 29 (10.8) | 5803 (8.9) | 10 df | 10 (6.6) | 5929 (9.8) | 10 df | ||

| March | 23 (8.6) | 6991 (10.7) | 10 (6.6) | 7086 (11.7) | ||||

| April | 14 (5.2) | 4682 (7.2) | 16 (10.6) | 4184 (6.9) | ||||

| May | 30 (11.2) | 4905 (7.5) | 16 (10.6) | 4371 (7.2) | ||||

| June | 23 (8.6) | 4862 (7.5) | 10 (6.6) | 4381 (7.2) | ||||

| July | 23 (8.6) | 4799 (7.4) | 15 (9.9) | 4089 (6.8) | ||||

| August | 19 (7.1) | 4826 (7.4) | 13 (8.6) | 4176 (6.9) | ||||

| September | 18 (6.7) | 5303 (8.1) | 17 (11.3) | 4767 (7.9) | ||||

| October | 26 (9.7) | 5847 (9.0) | 12 (7.9) | 5322 (8.8) | ||||

| November and December | 41 (15.2) | 11,093 (17.0) | 16 (10.6) | 10,468 (17.3) | ||||

| Fiscal year | ||||||||

| 2002/2003 to 2011/2012 | 219 (81.4) | 37,165 (57.1) | 64.9 | <0.001 | 121 (80.1) | 31,518 (52.1) | 47.52 | <0.001 |

| 2012/2013 and 2013/2014 | 50 (18.6) | 27,972 (42.9) | 1 df | 30 (19.9) | 29,009 (47.9) | 1 df | ||

| Acuity | ||||||||

| Resuscitation | 45 (16.7) | 932 (1.4) | 431.69 | <0.001 | 30 (19.9) | 613 (1.0) | 511.99 | <0.001 |

| Emergent | 85 (31.6) | 19,282 (29.6) | 2 df | 43 (28.5) | 18,156 (30.0) | 2 df | ||

| Urgent, semiurgent, nonurgent | 139 (51.7) | 44,923 (69.0) | 78 (51.7) | 41,758 (69.0) | ||||

| Mental health contact past 30 days | ||||||||

| ED and/or inpatient | 55 (20.5) | 5142 (7.9) | 68.73 | <0.001 | 39 (25.8) | 4530 (7.5) | 88.12 | <0.001 |

| Outpatient only | 56 (20.8) | 10,187 (15.6) | 2 df | 40 (26.5) | 10,844 (17.9) | 2 df | ||

| None | 158 (58.7) | 49,808 (76.5) | 72 (47.7) | 45,153 (74.6) | ||||

| ED contact past year | ||||||||

| No | 84 (31.2) | 34,815 (53.4) | 53.16 | <0.001 | 38 (25.2) | 31,564 (52.1) | 43.94 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 185 (68.8) | 30,322 (46.6) | 1 df | 113 (74.8) | 28,963 (47.9) | 1 df | ||

ED, emergency department.

a Individuals with missing data (1%) are not reported on to ensure their privacy and consistent comparisons.

Table 2.

Youth Diagnosed With an ‘Other’ Health Problem Only at Most Recent Emergency Department Contact.

| Variable | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 407),a n (%) | Controls (n = 1,239,462),a n (%) | χ2 | P Value | Cases (n = 158),a n (%) | Controls (n = 1,143,219),a n (%) | χ2 | P Value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 10 to 15 | 24 (5.9) | 341,223 (27.5) | 95.8 | <0.001 | 25 (15.8) | 266,027 (23.3) | 18.08 | <0.001 |

| 16 to 17 | 50 (12.3) | 125,507 (10.1) | 2 df | 29 (18.4) | 105,527 (9.2) | 2 df | ||

| 18 to 25 | 333 (81.8) | 772,732 (62.3) | 104 (65.8) | 771,665 (67.5) | ||||

| Community size | ||||||||

| ≥1,500,000 | 105 (25.8) | 463,486 (37.4) | 50.92 | <0.001 | 45 (28.5) | 416,051 (36.4) | 14.15 | <0.001 |

| 10,000 to 1,499,000 | 201 (49.4) | 605,612 (48.9) | 2 df | 76 (48.1) | 572,121 (50.0) | 2 df | ||

| Rural <10,000 | 101 (24.8) | 170,364 (13.7) | 37 (23.4) | 155,047 (13.6) | ||||

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||||||

| Lowest (Q1) | 107 (26.3) | 249,745 (20.1) | 9.53 | 0.002 | 46 (29.1) | 249,514 (21.8) | 4.92 | 0.027 |

| Higher (Q2-Q5) | 300 (73.7) | 989,717 (79.9) | 1 df | 112 (70.9) | 893,705 (78.2) | 1 df | ||

| Most recent ED contact: registration time | ||||||||

| 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. | 170 (41.8) | 564,623 (45.6) | 8.56 | 0.014 | 79 (50.0) | 536,416 (46.9) | 3.05 | 0.217 |

| 5 p.m. to midnight | 146 (35.9) | 464,648 (37.5) | 2 df | 48 (30.4) | 419,570 (36.7) | 2 df | ||

| After midnight, before 9 a.m. | 91 (22.4) | 210,191 (17.0) | 31 (19.6) | 187,233 (16.4) | ||||

| Day of week | ||||||||

| Weekday | 255 (62.7) | 787,794 (63.6) | 0.144 | 0.704 | 96 (60.8) | 723,848 (63.3) | 0.44 | 0.505 |

| Weekend | 152 (37.3) | 451,668 (36.4) | 1 df | 62 (39.2) | 419,371 (36.7) | 1 df | ||

| Month | ||||||||

| January | 38 (9.3) | 101,745 (8.2) | 16.34 | 0.09 | 21 (13.3) | 100,824 (8.8) | 17.16 | 0.071 |

| February | 31 (7.6) | 99,808 (8.1) | 10 df | 6 (3.8) | 99,129 (8.7) | 10 df | ||

| March | 22 (5.4) | 110,725 (8.9) | 15 (9.5) | 112,507 (9.8) | ||||

| April | 40 (9.8) | 87,073 (7.0) | 11 (7.0) | 80,109 (7.0) | ||||

| May | 40 (9.8) | 105,333 (8.5) | 12 (7.6) | 90,433 (7.9) | ||||

| June | 37 (9.1) | 107,557 (8.7) | 18 (11.4) | 91,064 (8.0) | ||||

| July | 44 (10.8) | 110,915 (8.9) | 11 (7.0) | 97,465 (8.5) | ||||

| August | 26 (6.4) | 109,256 (8.8) | 18 (11.4) | 97,013 (8.5) | ||||

| September | 33 (8.1) | 105,210 (8.5) | 8 (5.1) | 91,310 (8.0) | ||||

| October | 34 (8.4) | 105,555 (8.5) | 18 (11.4) | 95,194 (8.3) | ||||

| November and December | 62 (15.2) | 196,285 (15.8) | 20 (12.7) | 188,171 (16.5) | ||||

| Fiscal year | ||||||||

| 2002/2003 to 2011/2012 | 339 (83.3) | 791,516 (63.9) | 66.58 | <0.001 | 129 (81.6) | 703,567 (61.5) | 26.98 | <0.001 |

| 2012/2013 and 2013/2014 | 68 (16.7) | 447,946 (36.1) | 1 df | 29 (18.4) | 439,652 (38.5) | 1 df | ||

| Acuity | ||||||||

| Resuscitation | 25 (6.1) | 4475 (0.4) | 386.17 | <0.001 | 11 (7.0) | 2168 (0.2) | 385.66 | <0.001 |

| Emergent | 50 (12.3) | 104,149 (8.4) | 2 df | 19 (12.0) | 90,238 (7.9) | 2 df | ||

| Urgent, semiurgent, nonurgent | 332 (81.6) | 1,130,838 (91.2) | 128 (81.0) | 1,050,813 (91.9) | ||||

| Mental health contact past 30 days | ||||||||

| ED and/or inpatient | 34 (8.3) | 3775 (0.3) | 979.61 | <0.001 | 12 (7.6) | 3668 (0.3) | 365.58 | <0.001 |

| Outpatient only | 48 (11.8) | 36,214 (2.9) | 2 df | 31 (19.6) | 45,453 (4.0) | 2 df | ||

| None | 325 (79.9) | 1,199,473 (96.8) | 115 (72.8) | 1,094,098 (95.7) | ||||

| ED contact past year | ||||||||

| No | 163 (40.0) | 780,853 (63.0) | 91.93 | <0.001 | 41 (25.9) | 672,802 (58.9) | 70.62 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 244 (60.0) | 458,609 (37.0) | 1 df | 117 (74.1) | 470,417 (41.1) | 1 df | ||

ED, emergency department.

a Individuals with missing data (1%) are not reported on to ensure their privacy and consistent comparisons.

Days to Death

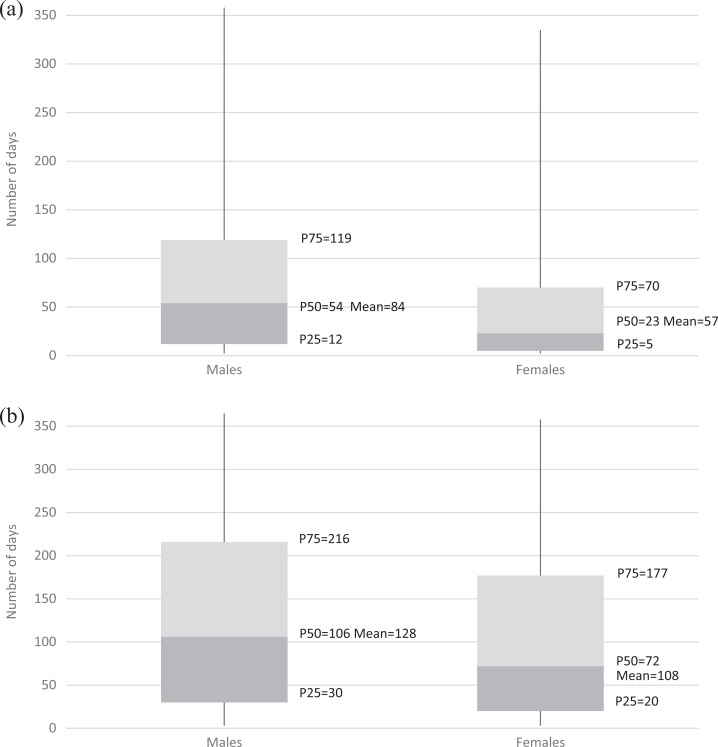

The number of days from the most recent ED contact to death among cases is illustrated by type of ED contact and sex (Figure 1). Means were higher than medians, but both were lower in females. Among male and female youth, medians were 54 and 23 among those with a mental health problem (Figure 1a) and 106 and 72 among those with no mental health problem (Figure 1b), respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Youth diagnosed with a mental health problem at most recent emergency department contact and time to death by suicide. (b) Youth diagnosed with an ‘other’ problem only at most recent emergency department contact and time to death by suicide. P = percentile.

Mental Health Problems and Suicide

The number and proportion of youth with specific mental health problems and corresponding associations with suicide are shown in Table 3. Some adjusted associations with suicide were consistent in boys and girls. Significant associations were found for ‘other’ self-inflicted injuries (aOR, 14.97 in males; aOR, 30.63 in females) and self-inflicted poisonings (aOR, 3.03 in males; aOR, 2.23 in females). ‘Other’ self-inflicted injuries were largely the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, Revision 10, Enhanced Canadian Version (ICD-10-CA) code X70 intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation. Protective associations were observed for anxiety disorders (aOR, 0.49 in males; aOR, 0.43 in females). Alcohol and other substance use disorders were not significantly associated with suicide, nor were the following categories: other mental disorders and both a mental health problem and an ‘other’ problem.

Table 3.

Types of Mental Health Problems and Suicide among Youth Diagnosed with a Mental Health Problem at Most Recent Emergency Department Contact.

| Mental Health Problem Type | Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | (n = 269) | (n = 65,137) | ||

| Alcohol disorder | 40 (14.9) | 16,987 (26.1) | 0.50 (0.35 to 0.69) | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.26) |

| Other substance disorder | 25 (9.3) | 8257 (12.7) | 0.71 (0.47 to 1.07) | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.26) |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | 57 (21.2) | 6367 (9.8) | 2.48 (1.85 to 3.33) | 2.20 (1.48 to 3.27) |

| Mood disorders | 69 (25.7) | 11,743 (18.0) | 1.57 (1.19 to 2.06) | 1.74 (1.24 to 2.45) |

| Anxiety disorders | 31 (11.5) | 20,892 (32.1) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.40) | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.76) |

| Self-inflicted self-poison | 34 (12.6) | 2278 (3.5) | 3.99 (2.78 to 5.73) | 3.03 (1.94 to 4.73) |

| Self-inflicted cut/pierce | 18 (6.7) | 757 (1.2) | 6.10 (3.76 to 9.89) | 5.54 (3.23 to 9.50) |

| Self-inflicted other | 40 (14.9) | 453 (0.7) | 24.94 (17.61 to 35.34) | 14.97 (9.23 to 24.26) |

| Other mental disorders | 14 (5.2) | 6190 (9.5) | 0.52 (0.31 to 0.90) | 0.79 (0.44 to 1.40) |

| Both mental and ‘other’ health problem | 27 (10.0) | 9517 (14.6) | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.97) | 1.15 (0.76 to 1.76) |

| Females | (n = 151) | (n = 60,527) | ||

| Alcohol disorder | 18 (11.9) | 12,008 (19.8) | 0.55 (0.33 to 0.90) | 0.89 (0.48 to 1.67) |

| Other substance disorder | 13 (8.6) | 3959 (6.5) | 1.35 (0.76 to 2.38) | 1.34 (0.71 to 2.56) |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | s | 2072 (3.4) | s | s |

| Mood disorders | 48 (31.8) | 14,520 (24.0) | 1.48 (1.05 to 2.08) | 1.44 (0.91 to 2.26) |

| Anxiety disorders | 22 (14.6) | 24,547 (40.6) | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.39) | 0.43 (0.25 to 0.75) |

| Self-inflicted self-poison | 33 (21.9) | 5214 (8.6) | 2.97 (2.02 to 4.37) | 2.23 (1.31 to 3.8) |

| Self-inflicted cut/pierce | s | 1267 (2.1) | s | s |

| Self-inflicted other | 26 (17.2) | 208 (0.3) | 60.32 (38.70 to 94.02) | 30.63 (15.89 to 59.0) |

| Other mental disorders | 11 (7.3) | 5375 (8.9) | 0.81 (0.44 to 1.49) | 0.87 (0.45 to 1.70) |

| Both mental and ‘other’ health problem | 9 (6.0) | 6790 (11.2) | 0.43 (0.20 to 0.92) | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.67) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; s, suppressed for privacy reasons.

a Adjusted for mental health problem types, age, community size, income quintile, date and time, and acuity of the most ED recent contact and prior medical care.

b Change >10% from crude OR for all adjusted ORs except in males (self-inflicted cut/pierce injury) and in females (other substance disorder, mood disorders, and other mental disorders).

Some associations varied by sex. After adjustments, schizophrenia/schizotypal/delusional disorders (aOR, 2.20), mood disorders (aOR, 1.74), and a self-inflicted cut/pierce injury (aOR, 5.54) were associated with suicide in males.

Other Health Problems and Suicide

The number and proportion of youth not diagnosed with a mental health problem but diagnosed with unintentional injuries and poisonings, assaults, or undetermined events are shown along with the corresponding associations in Table 4. After adjustments, an undetermined event was associated with suicide in both sexes (aOR, 5.68 in males; aOR, 5.18 in females) and an unintentional poisoning in males (aOR, 2.12). An assault was associated with suicide in both sexes; however, the association was stronger in females than males (aOR, 6.57 vs. 1.83). Otherwise, unintentional injuries were negatively associated with suicide in males (aOR, 0.75) and not associated with suicide in females.

Table 4.

Other Health Problems and Suicide among Youth Not Diagnosed with a Mental Health Problem at Most Recent Emergency Department Contact.

| Other only problem type | Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | (n = 407) | (n = 1,239,462) | ||

| Any unintentional injury | 158 (38.8) | 635,224 (51.2) | 0.60 (0.50 to 0.74) | 0.75 (0.61 to 0.94) |

| Any unintentional poisoning | 22 (5.4) | 7596 (0.6) | 9.27 (6.03 to 14.25) | 2.12 (1.14 to 3.95) |

| Assault | 23 (5.7) | 32,044 (2.6) | 2.28 (1.48 to 3.44) | 1.83 (1.16 to 2.89) |

| Undetermined injury or poisoning | 17 (4.2) | 2518 (0.2) | 21.41 (13.16 to 34.86) | 5.68 (2.85 to 11.35) |

| Females | n = 158 | n = 1,143,219 | ||

| Any unintentional injury | 43 (27.2) | 338,897 (29.6) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.26) | 1.08 (0.74 to 1.58) |

| Any unintentional poisoning | 8 (5.1) | 7032 (0.6) | 8.62 (4.23 to 17.56) | 1.90 (0.61 to 5.96) |

| Assault | 8 (5.1) | 7106 (0.6) | 8.53 (4.19 to 17.37) | 6.57 (3.08 to 14.03) |

| Undetermined injury or poisoning | 6 (3.8) | 1759 (0.2) | 28.68 (12.62 to 65.13) | 5.18 (1.43 to 18.77) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a Adjusted for other only problem types, age, community size, income quintile, date and time, and acuity of the most emergency department (ED) recent contact and prior medical care in the year before the most recent ED contact.

b Change >10% from crude OR.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of associations between ED-based diagnoses and a subsequent suicide among youth presenting to the ED. Among youth diagnosed with a mental health problem at their most recent ED contact, those with self-inflicted ‘other’ injuries—largely hanging/strangulation/suffocation—stood out with adjusted ORs exceeding 14 in both sexes. In males, self-inflicted cut/pierce injuries were also striking with an adjusted OR exceeding 5. Mood disorders were associated with suicide in males and females before adjustments and after adjustments in males. Schizophrenia/schizotypal/delusional disorders were associated with suicide in males. Alcohol and other substance use disorders were not associated with suicide, and anxiety disorders were negatively associated in both sexes. Among youth not diagnosed with a mental health problem, an undetermined event and an assault were associated with suicide in both sexes, with the assault association stronger in females. Unintentional poisonings were associated with suicide in both sexes and remained in males after adjustments. The time from the most recent ED contact to death for half of the cases ranged from within 3 weeks (23 days among females with a mental health problems) to within 3 months (106 days among males not diagnosed with a mental health problem).

Limitations

ED diagnoses were based on physician judgement, not validated through expert review or standardized, structured interviews. Further, ICD codes lack information on suicidal intent. Nevertheless, these diagnoses are real world and, therefore, pertinent to clinical and system-level decision making. Given almost all youth who died by suicide would have had a mental disorder15 and self-harm is underdetected in the ED among youth,22 underascertainment of mental health problems is considerable—less than half of cases were diagnosed with a mental health problem. Due to small cells, we were unable to estimate associations with suicide for certain diagnoses (e.g., child maltreatment or posttraumatic stress disorder) within broader categories or test statistical interactions between specific diagnoses and/or other correlates. Moreover, the timing of events needs refinement. Our study—spanning ages 10 to 25 with a 1-year look-back period—was not designed to examine possible mediators of diagnostic associations with suicide. Some mental health problems likely precede and contribute to the onset of others.23 Adjusting for mental health problems that occurred more distally together with more proximal ones may have attenuated associations with suicide.

Comparison with Other Studies

We found strong associations for ‘other’ injuries—largely hanging/strangulation/suffocation—in both sexes. Among Canadian youth, this is also the most common method of suicide.24 Among male youth, cut/pierce injuries were also strongly associated with suicide. Cut/pierce injuries have been found more strongly associated with suicide than self-poisonings25 and more medically serious among (all ages) males than females.26

The reduced risk of suicide for those with anxiety disorders and the lack of association between alcohol, other substance use disorders, and mood disorders (females only) deserve comment because these disorders are associated with suicide among youth in the general population.15,27,28 The prevalence of these diagnoses among controls was relatively common, especially anxiety disorders (Table 3). Accordingly, among youth who are diagnosed with a mental health problem in the ED, these diagnostic patterns, on their own, may not help hospitals and clinicians in the ED (e.g., consulting psychiatrists) identify those at more imminent risk for suicide.

This study also found that mood disorders as well as schizophrenia/schizotypal/delusional disorders were associated with suicide in males. The latter associations may reflect the younger age of onset of psychotic disorders in males29 and, for first episodes, an increased risk of self-harm30 and suicide in the year after initial hospital contact.31 Studies investigating associations between hospital presentations for self-harm, mental disorders, and suicide among youth are scarce. One previous study14 found inpatient diagnoses of nonorganic psychosis with self-harm increased the risk of suicide 7 times.

Unintentional poisonings were associated with suicide in both sexes and after adjustments in males. Given ED underdiagnosis of mental health problems and weak associations between ED-diagnosed mental and ‘other’ health problems, there is clinical value in investigating whether specific ‘other’ health problems only are associated with suicide among youth not identified with a mental health problem. Despite differences in sampling and methods,17 we too found elevated risks among youth treated in hospital for poisonings and injuries with an undetermined intent. We also found higher risks for assault in both sexes but with a stronger association in females. Unintentional injuries, quite common among ED controls (Table 4), were not associated with suicide in females and negatively associated in males. Still, it is plausible that injuries and poisonings requiring hospital admission17 confer a stronger risk. It remains uncertain, though, to what extent injuries and poisonings may be directly causal for suicide (e.g., through brain damage), in the causal pathway (e.g., a stressor), or a misclassification of self-harm.17

Conclusions

Our study provides findings directly relevant to hospitals and clinicians providing ED-based care to youth and contributes to growing evidence on how the ED can best act as a service delivery site for suicide prevention and access to mental health care more broadly.1 It identified several high-risk groups:

Among youth with a mental health problem (41.9% of cases; 5% controls): those with self-harm and males with mood or psychotic disorders

Among youth with no mental health problem, those with injuries and poisonings not identified as self-inflicted: undetermined events, unintentional poisonings, and assaults

The underdetection of mental health problems among cases is troubling with implications for the training and availability of mental health professionals to EDs. Cultural expectations of EDs may need to shift from where to send these youth to how to best treat these youth,32 and promising models of emergency mental health interventions deserve further study.1,33–35 Those assessed as suicidal in the ED typically receive a risk assessment and are then triaged to inpatient or outpatient treatment. Safety planning, including removing access to lethal means, and active outreach are brief, promising preventive interventions that can be implemented in the ED.36,37 Because the time intervals between youth being seen in the ED and their subsequent suicides are short, the opportunity to intervene is brief, demanding urgent attention from providers.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_Table_1 for Emergency Department Presentations and Youth Suicide: A Case-Control Study by Anne E. Rhodes, Mark Sinyor, Michael H. Boyle, Jeffrey A. Bridge, Laurence Y. Katz, Jennifer Bethell, Amanda S. Newton, Amy Cheung, Kathryn Bennett, Paul S. Links, Lil Tonmyr, and Robin Skinner in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario for making this research possible and Dr. Hong Lu at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) for analytic support. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Footnotes

Data Access: Access to data for this project was granted to Dr. Rhodes through a data-sharing agreement between the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. As such, the data set cannot be shared.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Funding for this project also was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) in the form of an operating grant. CIHR had no direct or indirect involvement in the completion of the study or analysis of results.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online

References

- 1. Asarnow JR, Babeva K, Hortsmann E. The emergency department: challenges and opportunities for suicide prevention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;26(4):771–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babeva K Hughes JL, Asarnow JR. Emergency department screening for suicide and mental health risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bridge JA, Horrowitz LM, Fontanella CA, et al. Prioritising research to reduce youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 suppl 2):S229–S234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larkin GL, Beautrais A. Emergency departments are underutilized sites for suicide prevention. Crisis. 2010;31(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chock MM, Bommersbach TJ, Geske JL, et al. Patterns of health care usage in the year before suicide: a population-based case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(11):1475–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kvaran RB, Gunnarsdottir OS, Kristbjornsdottier A, et al. Number of visits to the emergency department and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morrison KB, Laing L. Adults’ use of health services in the year before death by suicide in Alberta. Health Reports. 2011;22(3):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhodes AE, Boyle MH, Bridge JA, et al. The medical care of male and female youth who die by suicide: a population-based case control study. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63:161–169.29121806 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Newton AS, Ali S, Johnson DW, et al. A 4-year review of pediatric mental health emergencies. Can J Emerg Med. 2009;11(15):447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. MHASEF Research Team. The mental health of children and youth in Ontario: a baseline scorecard. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2015. [accessed 2017 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2015/Mental-Health-of-Children-and-Youth. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1303–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calear AL, Christensen H, Freeman A, et al. A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(5):467–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rotheram-Borus MJ, Piacentini J, Cantwell C, et al. The 18-month impact of an emergency room intervention for adolescent suicide attempters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(6):1081–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beckman K, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Lichenstein P, et al. Mental illness and suicide after self-harm among young adults: long term follow-up of self harm patients, admitted to hospital care, in a national cohort. Psychol Med. 2016;46(16):3397–3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):372–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawton K, Harriss L. Deliberate self-harm in young people: characteristics and subsequent mortality in a 20-year cohort of patients presenting to hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1574–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zambon F, Laflamme L, Spolaore P, et al. Youth suicide: an insight into previous hospitalisation for injury and sociodemographic conditions from a nationwide cohort study. Inj Prev. 2011;17(3):176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rhodes AE, Khan S, Boyle MH, et al. Sex differences in suicides among children and youth: the potential impact of help-seeking behaviour. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(5):274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pisani AR, Murrie DC, Silverman MM. Reformulating suicide risk formulation: from prediction to prevention. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(4):623–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rhodes AE, Khan S, Boyle MH, et al. Sex differences in suicides among children and youth: the potential impact of misclassification. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;103(3):213–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Canadian Institutes for Health Information (CIHI). Emergency and ambulatory care. Ottawa, Ontario; 2017. [accessed 2017 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/emergency-and-ambulatory-care. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bethell J, Rhodes AE. Identifying deliberate self-harm in emergency department data. Health Rep. 2009;20(2):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rhodes AE, Boyle MH, Bridge JA, et al. Antecedents and sex/gender differences in suicidal behavior. World J Psychiatry. 2014;22:120–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skinner R, McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980-2008. CMAJ. 2012;184(9):1029–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, et al. Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larkin C, Corcoran P, Perry I, et al. Severity of hospital-treated self-cutting and risk of future self-harm: a national registry study. J Mental Health. 2014;23(3):115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lesage AD, Boyer R, Grunberg F, et al. Suicide and mental disorders: a case-control study of young men. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):1063–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Page A, Morrell S, Hobbs C, et al. Suicide in young adults: psychiatric and socio-economic factors from a case-control stud. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive review. Schizophrenia Res Treatment. 2012;2012:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Challis S, Nielssen O, Harris A, et al. Systematic meta-analysis of the risk factors for deliberate self-harm before and after treatment for first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(6):442–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nordentoft M, Madsen T, Fedyszyn I. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first-episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bridge JA, Horowitz LM, Campo JV. ED-SAFE—can suicide risk screening and brief intervention initiated in the emergency department save lives? JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jabbour M, Reid S, Polihronis C, et al. Improving mental health care transitions for children and youth: a protocol to implement and evaluate an emergency department clinical pathway. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, et al. Pediatric suicide-related presentations: a systematic review of mental healthcare in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Newton AS, Hartling L, Soleimani A, et al. A systematic review of management strategies for children’s mental health care in the emergency department: update on evidence and recommendations for clinical practice and research. Emerg Med J. 2017;34(6):376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):894–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Transforming Health Systems Initiative Work Group. Recommended standard care for people with suicide risk: making health care suicide safe Washington, DC: Education Development Center; 2018. [accessed 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: http://actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/sites/actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/files/Action%20Alliance%20Recommended%20Standard%20Care%20FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_Table_1 for Emergency Department Presentations and Youth Suicide: A Case-Control Study by Anne E. Rhodes, Mark Sinyor, Michael H. Boyle, Jeffrey A. Bridge, Laurence Y. Katz, Jennifer Bethell, Amanda S. Newton, Amy Cheung, Kathryn Bennett, Paul S. Links, Lil Tonmyr, and Robin Skinner in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry