Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore how individual differences in content of the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA in skeletal muscle of slaughter-sized Atlantic salmon, are associated with expression of genes involved in key metabolic processes. All experimental fish were fed the same diet throughout life and fasted for 14 days prior to slaughter. Still, there were relatively large individual variations in EPA and DHA content of skeletal muscle. Higher DHA content was concurrent with increased expression of genes of the glycolytic pathway and the production of pyruvate and lactate, whereas EPA was associated with increased expression of pentose phosphate pathway and glycogen breakdown genes. Furthermore, EPA, but not DHA, was associated with expression of genes involved in insulin signaling. Expression of genes specific for skeletal muscle function were positively associated with both EPA and DHA. EPA and DHA were also associated with expression of genes related to eicosanoid and resolvin production. EPA was negatively associated with expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism. Thus, a possible reason why some individuals have a higher level of EPA in the skeletal muscle is that they deposit - rather than oxidize - EPA for energy.

Introduction

Farmed Atlantic salmon has traditionally been very rich in the healthy long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC n-3 PUFA) eicosapentaenoic- (EPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acid, and thereby they are a valuable source of these fatty acids in the human diet. Limited availability of fishmeal and fish oil on the world market, in conjunction with a growing aquaculture industry, has led to a substantial substitution of marine ingredients with plant ingredients in feed for farmed salmon in the last few decades1. Consequently, decreased levels of EPA and DHA in farmed salmon tissues and organs are reported in Norwegian, Scottish and Tasmanian Atlantic salmon1–3. This is not only reducing the nutritional value of Atlantic salmon fillet to consumers, but may also influence fish health and quality4.

The LC n-3 PUFA content of fish tissues is a complex trait influenced by feed, life stage, and metabolic processes including digestibility and uptake of fatty acids (FA) in the gut, as well as selective transport, deposition and β-oxidation in organs and tissues4–8. In addition, endogenous omega-3 bioconversion enables salmonids to convert the shorter chain alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) to the longer chain PUFAs EPA and DHA through a series of desaturation and elongation steps, followed by peroxisomal β-oxidation9,10. In Atlantic salmon, the rate of bioconversion is inversely related to the amounts of fish oil in the diet9,11–13. The omega-3 bioconversion is also influenced by water temperature, the genetic background, and life stage of the fish14,15.

Both EPA and DHA fulfill numerous biological functions in the animal body. EPA and DHA are to some extent metabolically interchangeable making it in some cases difficult to pinpoint functions specific to each of them. However, it is known that DHA is more critical than EPA as a structural component of cell membranes including lipid rafts, while EPA is believed to play a more central role in regulation of several processes related to immunity and inflammation16,17. Atlantic salmon fed only EPA but no DHA developed abnormal intestinal morphology, while the fish fed only DHA but no EPA developed a normal intestine4, pointing to the importantce of DHA for functional intestinal cell membranes. Other studies have shown that EPA content of heart and head kidney tissues of Atlantic salmon is associated with reduced severity of the inflammatory response to the viral disease Heart and skeletal muscle inflammation18. Specific functions of EPA and DHA in production of eicosanoids and their role in inflammatory responses has been described both in fish19 and in mammals20. Further, different pro-resolving lipid mediators, resolvins and protectins, can also be generated. Resolvins are derived from both EPA and DHA, categorized as either E-series (from EPA) or D-series (from DHA), while protectins are derived from DHA21,22. Although little is known for fish, the different resolvins and protectins are shown to have potent specific immunoregulatory actions in mammals21,22.

Evidence from mammalian studies further indicates that tissue contents of EPA and DHA play important roles in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Increased contents of EPA and DHA are reported to improve glucose uptake23,24, have favorable effects on glucose utilization25, and thereby have a preventive effect on development of metabolic syndrome26,27. EPA and DHA may also improve skeletal muscle capability of switching between use of lipids, protein and glucose for production of energy28. High levels of EPA may result in downregulated lipogenesis and upregulated mitochondrial β-oxidation29. The systems that regulate lipogenesis and LC n-3 PUFA biosynthesis in mammals are largely conserved in Atlantic salmon30, and dietary LC n-3 PUFA levels have been shown to influence lipid metabolism also in Atlantic salmon31,32. With the shift in salmon diets causing major alterations in EPA and DHA content of skeletal muscle, it is especially important to gain knowledge on how these alterations influence lipid and carbohydrate metabolic pathways.

Most gene expression studies of omega-3 effects in Atlantic salmon have focused on the liver transcriptome and its responses to changed dietary levels of LC n-3 PUFAs13,33–36. Skeletal muscle is highly relevant as it constitutes the largest part of the Atlantic salmon body, and expresses desaturase and elongase genes37,38, as well as transcription factors known to regulate lipid metabolism genes8. Further, there are inherent differences in the muscle content of EPA and DHA between Atlantic salmon fed the same diet39, but the metabolic differences between individuals with high and low levels remain unknown.

The main aim of this study is to investigate how individual differences in EPA and DHA content in skeletal muscle of Atlantic salmon are associated with expression of genes involved in key physiological processes, particularly nutrient metabolism. We limit this study to the contents of EPA and DHA in the skeletal muscle and transcriptome of skeletal muscle and liver.

Methods

Fish populations and recordings

The fish studied originated from families and documentation groups from the entire 2014 year-class of the Atlantic salmon breeding population of SalmoBreed AS. The fish were transferred to sea at a mean weight of 0.1 kg, and slaughtered approximately 12 months later, at a mean weight of 3.6 kg. The fish were fed a commercial broodstock feed from Skretting (https://www.skretting.com/en/products/atlantic-salmon/?lifephase=474980) with a high fish oil content, and were fasted 13–14 days prior to slaughter. All the fish were reared under the same conditions.

Skeletal muscle and liver tissue samples for RNA-sequencing were taken from each individual fish at harvest, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently stored at −70 °C. Skeletal muscle samples for lipid and FA analysis were taken from Norwegian Quality Cut collected at harvest, frozen and stored at −20 °C. In total, 668 fish were analyzed for skeletal muscle FA composition. The ranges in bodyweight and fat content of skeletal muscle were 1.2–6.4 kg and 5.5–27.7%, respectively. In order to minimize the effects of size and lipid deposition, 59 fish were selected for RNA-sequencing based on bodyweight (3.3 to 3.9 kg) and skeletal muscle fat level (16 to 25%). The selected individuals came from 48 full sib families, originating from 39 sires and 48 dams.

Lipid and fatty acid analysis

Total lipids were extracted from homogenized liver and skeletal muscle samples of individual fish, according to the Folch method40. Using one milliliter from the chloroform-methanol phase, FA composition of total lipids was analyzed following the method described by Mason and Waller41. The extract was dried briefly under nitrogen gas and residual lipid extract was trans-methylated overnight with 2′,2′-dimethoxypropane, methanolic-HCl, and benzene at room temperature. The methyl esters formed were separated in a gas chromatograph (Hewlett Packard 6890; HP, Wilmington, DE, USA) with a split injector, using an SGE BPX70 capillary column (length 60 m, internal diameter 0.25 mm, and film thickness 0.25 μm; SGE Analytical Science, Milton Keynes, UK) and a flame ionization detector. The results were analyzed using HP Chem Station software. The carrier gas was helium, and the injector and detector temperatures were both 270 °C. The oven temperature was raised from 50 to 170 °C at the rate of 4 °C/min, and then raised to 200 °C at a rate of 0.5 °C/min and finally to 240 °C at 10 °C/min. Individual FA methyl esters were identified by reference to well-characterized standards. The content of each FA was expressed as a percentage of the total amount of FAs in the analyzed sample. Presentation of the results will focus on the most abundant LC n-3 PUFAs of the fillet: 20:5n-3 (EPA) and 22:6n-3 (DHA), and the sum of EPA and DHA (EPA + DHA).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from liver and skeletal muscle tissues of each individual fish using the PureLink Pro 96 RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. RNA was treated with PureLink On-Column DNase Digestion (Invitrogen) to remove any contaminating DNA. Samples were shipped to The Norwegian High-Throughput Sequencing Centre, where the mRNA library preparation and sequencing of transcripts were performed using standard protocols (www.illumina.com). Samples were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq platform as paired-end 151 bp reads. After final quality control, results from 48 liver- and 59 skeletal muscle samples remained for analyses.

Processing of reads, alignment and annotation was performed according to Moghadam et al.42. Expression data were normalized via the median of the geometric means of fragment counts across all sample43. Cufflinks and Cuffdiff were used to estimate the expression abundances of the assembled genes and transcripts44.

Statistical analysis

Gene expression data were normalized by calculating the aligned fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments (FPKM). Normalized gene expression data were log2 transformed prior to the statistical analysis.

Trait-associated genes were defined by using linear regression analysis, testing for an association between continuous traits and mRNA expression. The FA content was considered the response variable and each individual gene expression an explanatory variable in the model. As suggested by Seo et al.45, univariate analyses were carried out for each FA trait. The following general linear mixed model was fitted for each trait:

where Y is the skeletal muscle FA content (EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA) of one individual, μ the overall mean, sexj the fixed effect of sex (male or female), fat the percentage of fat in the tissue of the gene expression as a covariate (muscle or liver), genek gene expression level of gene k, family random effect of family (1–48), and e random residual variation.

Genes were considered significantly associated with traits when the p-value of the regression coefficient was < 0.05. Genes of interest are presented with their regression coefficients. All significant genes are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Enrichment analysis

A search for enriched GO classes and KEGG pathways in the list of trait-associated genes was performed by counting of genes among the trait-associated genes and all genes that passed quality control. Enrichment was assessed with Yates’ corrected chi square test (p < 0.05). Terms with less than five genes were not taken into consideration.

The enrichment analysis was used for an initial screening to outline the functional groups and pathways of interest. Next, we focused on individual genes, taking into account the regression coefficients as metrics of expression differences between the phenotypes.

Ethics statement

The study was based on post mortem sampling of material from fish harvested from a commercial breeding program for other purposes. The experimental plan was evaluated towards the Norwegian regulation for use of animals in experiments (FOR-2015-06-18-761, Forskrift om bruk av dyr i forsøk). The regulation states that activities related to non-experimental aquaculture activities are exempt from the regulation, and that it is legal to sample from animals post mortem without a specific license. Thus, the samples used in this study were collected in accordance with the Norwegian legislation for animal experiment.

Results and Discussion

Description of phenotypes of experimental fish

In this study, we investigated how individual differences in EPA and DHA content (% of total FAs) in skeletal muscle of Atlantic salmon were associated with muscular and hepatic expression of genes involved in key physiological processes, particularly nutrient metabolism. The fish originated from the same strain of a breeding population, were reared under the same conditions and were all fed the same diet (as described previously in Horn et al.37), and fasted for two weeks prior to slaughter.

The EPA and DHA content of skeletal muscle changes with fish size and fat content, therefore fish of approximately the same size (3.6 kg) were selected for the gene expression analyses, as shown in Table 1. The mean skeletal muscle fat content was 19.7%. The mean contents (in percentage of total FAs) of EPA and DHA were 5.8 and 6.6%, respectively (Table 1). This is approximately twice as high as the EPA and DHA content found in today’s commercially produced Atlantic salmon in Norway, which reflects the high levels of these FA in the feed used in the current study4,46. Standard diets for Atlantic salmon breeding populations are based on high levels of marine ingredients, usually a ratio of 70/30 between marine and plant ingredients, and the diets are therefore rich in EPA and DHA. Commercial diets, on the other hand, are based on 70% plant ingredients and are therefore low in EPA and DHA1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the fish material.

| Trait | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodyweight (g) | 59 | 3634 | 161 | 3330 | 3890 |

| Muscle fat (%) | 59 | 19.7 | 1.99 | 16.2 | 25.3 |

| EPA (%)* | 59 | 5.81 | 1.46 | 4.36 | 8.79 |

| DHA (%)* | 59 | 6.63 | 0.49 | 5.75 | 7.45 |

| EPA + DHA (%)* | 59 | 12.45 | 1.60 | 10.35 | 15.71 |

N: Number of observations, SD: Standard deviation, Min: Minimum value. Max: Maximum value. *% of total FAs in skeletal muscle.

Relatively large variations in EPA and DHA contents were found in the skeletal muscle of the 59 experimental fish, even though the fish were of approximately the same size, reared under the same experimental conditions and fed the same diet throughout their life. The contents of EPA varied between 4.4 to 8.8% of total FAs, while DHA varied from 5.8 to 7.5% (Table 1). This indicates that the genetic variation between individuals may cause metabolic differences in one or several of the processes; dietary uptake, deposition, utilization or bioconversion of dietary fatty acids, and thereby result in individual differences in EPA and DHA contents of muscle despite the fact that the fish has been fed the same diet. Genetic variation was expected in the current study considering the family structure (48 full-sib families and 39 half-sib families). It has previously been shown that both EPA and DHA content of skeletal muscle are heritable traits34,37.

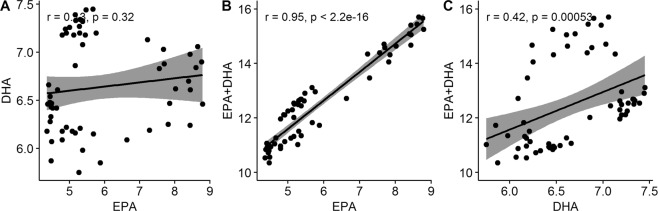

There was a low correlation between EPA and DHA percentage in skeletal muscle (Fig. 1A). A similar correlation was found in an analysis of a larger dataset of the same population (r = 0.23, n = 668)37. The fish with the highest DHA percentage had a low EPA percentage (Fig. 1A), indicating that some individuals had higher capacities for the conversion from EPA to DHA, or higher β-oxidation rate of one of the two FAs. EPA + DHA was more strongly correlated to EPA than DHA (Fig. 1B,C), because there was greater variation in EPA content (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between contents of fatty acids in skeletal muscle. (A) Correlation between EPA and DHA (% of total FAs). (B) Correlation between EPA and EPA + DHA. (C) Correlation between DHA and EPA + DHA.

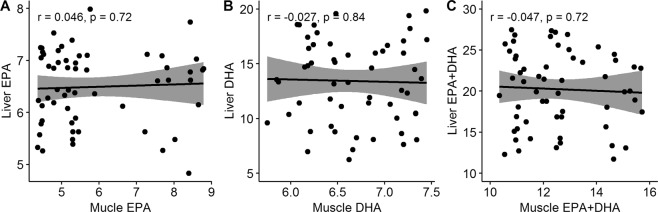

Correlations between liver and skeletal muscle EPA and DHA content were very low (Fig. 2). This is most likely due to the differences between liver and skeletal muscle lipid metabolism. Feed trials with Atlantic salmon have shown that the tissues respond differently to increased dietary levels of EPA and DHA and that the skeletal muscle FA composition is to a much higher extent than the liver influenced by dietary FA composition4.

Figure 2.

Correlation between liver and skeletal muscle content of fatty acids. Correlation between liver and skeletal muscle content of (A) EPA, (B) DHA, and (C) EPA + DHA (% of total FAs).

Gene expression differences between EPA and DHA

The number of trait-associated genes identified by the linear model association tests was more than 50% higher for the EPA trait than for the DHA trait in both skeletal muscle and liver. In skeletal muscle, the number of trait-associated genes were 3487, 1915 and 3169 for EPA, DHA and EPA + DHA, respectively. The association tests of skeletal muscle FAs with liver gene expression identified 4005 EPA-, 2519 DHA- and 4285 EPA + DHA-associated genes. EPA was not only associated with a higher number of genes, but also had stronger associations compared to DHA (Figs 3–8). This could be related to that EPA is a more bioactive FA compared to DHA, as it is a precursor for many bioactive molecules influencing for instance immunity and inflammatory responses17. The transcriptome pattern of skeletal muscle for EPA + DHA was relatively similar to the pattern found for EPA, while DHA was different, most likely because EPA + DHA was more strongly correlated with EPA than DHA (Fig. 1).

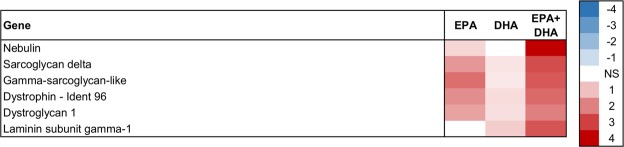

Figure 3.

Skeletal muscle tissue development. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in skeletal muscle. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association.

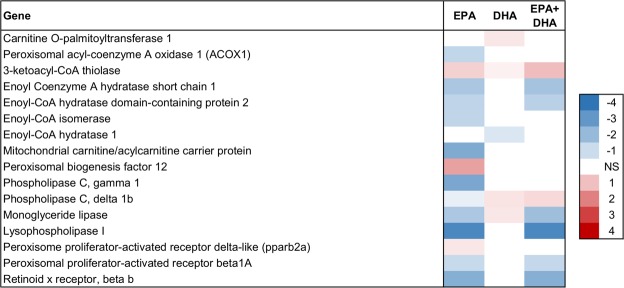

Figure 8.

Lipid catabolism in liver. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in liver. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association.

Searches for enriched functional classes of GO and KEGG pathways were performed in order to find thematic associations among the trait-associated genes. These identified in total 55 groups enriched for the trait EPA in skeletal muscle and 47 for DHA. In the liver, 62 groups were enriched for skeletal muscle content of EPA and 45 for DHA (Supplementary Table S2). From these, the functional groups considered relevant for the scope of the study were selected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Enriched functional groups.

| Muscle Gene Expression | Liver Gene Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Muscle | Vocabulary | Genes* | EPA Muscle | Vocabulary | Genes* |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | KEGG | 15/89 | Fatty acid beta-oxidation | GO | 14/53 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | KEGG | 18/109 | Lipid metabolic process | GO | 44/343 |

| Mitochondrion | GO | 266/2005 | Mitochondrion | GO | 270/2005 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | KEGG | 13/81 | Peroxisome | GO | 24/140 |

| Insulin signaling pathway | KEGG | 54/442 | Triglyceride catabolic process | GO | 8/34 |

| PPAR signaling pathway | KEGG | 21/164 | Insulin signaling pathway | KEGG | 59/442 |

| Fat cell differentiation | GO | 17/129 | PPAR signaling pathway | KEGG | 36/164 |

| Skeletal muscle tissue development | GO | 23/190 | |||

| DHA Muscle | Vocabulary | Genes* | DHA Muscle | Vocabulary | Genes* |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | KEGG | 11/89 | Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | KEGG | 8/40 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | KEGG | 10/109 | Fatty acid elongation in mitochondria | KEGG | 6/30 |

| Gluconeogenesis | GO | 10/90 | Lipid metabolic process | GO | 37/343 |

| Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | KEGG | 15/198 | Lipid particle | GO | 15/88 |

| Mitochondrion | GO | 176/2005 | Mitochondrion | GO | 207/2005 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | KEGG | 13/119 | PPAR signaling pathway | KEGG | 16/164 |

| Skeletal muscle tissue development | GO | 17/190 | |||

| Striated muscle cell development | GO | 6/39 | |||

*Number of genes corresponding to term in the list of trait associated genes/total number of genes of GO/KEGG term.

The enrichment analyses identified several functional groups related to nutrient metabolism as associated with skeletal muscle content of EPA and DHA. The following functional groups were enriched for both FAs; TCA cycle, FA metabolism, mitochondrion and skeletal muscle development (in muscle), lipid metabolic process, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) signalling and mitochondrion (in liver) (Table 2). Functional groups enriched for EPA only included pentose phosphate pathway, insulin and PPAR signalling in muscle, and insulin signalling and lipid catabolic processes in liver. Functional groups enriched for DHA only included glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in muscle, and biosynthesis of unsaturated FAs and FA elongation in liver. No associations were found with protein metabolism. In the following sections, trait-associated genes from these functional groups will be discussed.

It should be noted that the fish in this study was fed a diet rich in EPA and DHA and further fasted for two weeks prior to slaughter, both being factors known to influence nutrient metabolism. Whether the suggested associations of EPA and DHA in Atlantic salmon skeletal muscle with the different metabolic pathways applies to fish fed a commercial diet and with a shorter fasting period prior to slaughter, remains to be elucidated.

Muscle content of EPA and DHA was associated with skeletal muscle tissue development and function

Several studies on mammals suggest that EPA and DHA can influence the response of skeletal muscle to exercise and nutrient utilization, and improve muscle anabolic processes, although the underlying mechanisms are unclear (reviewed in Jeromson et al.28).

The enrichment analysis identified skeletal muscle tissue development as an overrepresented group for both EPA and DHA (Table 2). Positive associations with both EPA and DHA were found with expression of the genes sarcoglycan, dystrophin, dystroglycan and laminin - all involved in the Dystrophin-Associated Protein Complex (DAPC) in skeletal and cardiac muscle (Fig. 3). The DAPC plays a structural role in the muscle by stabilizing the sarcolemma during contraction and relaxation, and transmits force generated in the muscle sarcomeres to the extracellular matrix47.

There was a clear additive effect of EPA and DHA, as shown by the higher regression coefficients of EPA + DHA (Fig. 3). EPA + DHA had an especially strong positive association with expression of nebulin. Nebulin is a structural protein that functions in numerous cellular processes including regulation of muscle contraction, improving muscle force efficiency, Z-disc formation, and myofibril assembly48.

In conclusion, these results indicate that EPA and DHA are associated with skeletal muscle function and/or development in Atlantic salmon.

EPA and DHA were associated with carbohydrate metabolism in skeletal muscle

Carnivorous fish have a low capacity to utilize dietary digestible carbohydrates, and have slow blood glucose clearance, however, they do have an active glucose homeostatic system with the presence of almost all the essential biological elements (reviewed in49 and50).

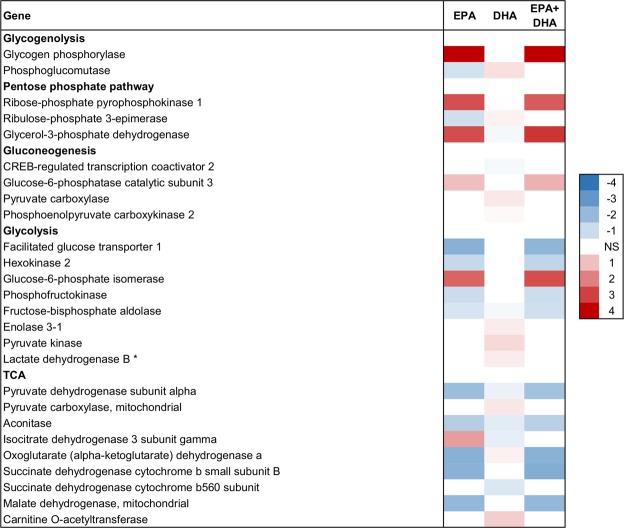

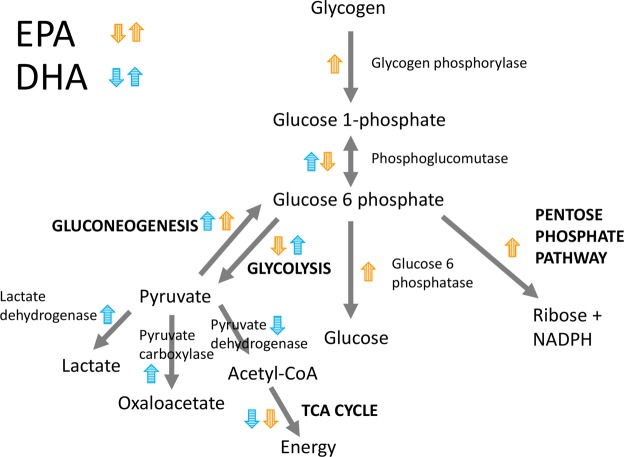

EPA and DHA were differently associated with the expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism in the skeletal muscle (Fig. 4). While increasing DHA content was concurrent with increased expression of genes in the glycolytic pathway and the production of pyruvate and lactate (anaerobic glycolysis), EPA was associated with increased expression of genes involved in the pentose phosphate pathway and nucleotide synthesis, in addition to increased glycogen breakdown (Fig. 9).

Figure 4.

Carbohydrate metabolism in skeletal muscle. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in skeletal muscle. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association. *Anaerob glycolysis.

Figure 9.

Overview of main results regarding carbohydrate metabolism in skeletal muscle. Colored arrow up and down indicate positive and negative associations, respectively.

Carbohydrates are stored as glycogen in the muscle, which can be broken down to glucose units. Gene expression of the catalyzer of the rate-limiting step of glycogen degradation to glucose, glycogen phosphorylase, was positively associated with EPA and EPA + DHA (Fig. 4). In addition, EPA was positively associated with expression of the gluconeogenesis-specific gene glucose-6-phosphatase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose, which can then be released into the blood for use in other tissues. The glucose-6-phosphate derived from the breakdown of glycogen can also be utilized as a substrate for glycolysis, or enter the pentose phosphate pathway to yield ribose derivatives and NADP, which is used in multiple anabolic pathways (Fig. 9).

The results from this study indicate that increased EPA content in skeletal muscle is concurrent with reduced glycolytic activity. Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis are opposing processes, and share several enzymes, acting in reversible reactions. There are three critical stages separating the two pathways. EPA was negatively associated with expression of two of the three glycolysis-specific genes (hexokinase and phosphofructokinase), and positively associated with expression of the gluconeogenesis-specific gene glucose-6-phosphatase that catalyzes the opposite reaction of hexokinase (Fig. 4). DHA, on the other hand, was positively associated with gene expression of the glycolysis-specific enzyme pyruvate kinase (the last step of glycolysis, forming pyruvate). However, DHA was also positively associated with pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, two gluconeogenesis-specific enzymes that catalyzes the opposite reaction of pyruvate kinase. Further, DHA was positively associated with lactate dehydrogenase, which converts pyruvate to lactate, and negatively associated with pyruvate dehydrogenase, which converts pyruvate to acetyl-coA. Hence, increased DHA content was concurrent with increased anaerobic glycolytic potential, where the pyruvate produced by glycolysis is shuttled towards lactate to a larger degree than to the TCA cycle (Fig. 9).

EPA, however, had a clear negative association with TCA cycle gene expression in muscle, possibly related to the reduced glycolytic activity to form pyruvate; expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase, plus four of the enzymes catalyzing TCA cycle, were negatively associated with EPA. The only TCA-cycle gene whose expression was positively associated with EPA content was α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (Fig. 4).

The enrichment analysis suggested an association between the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and EPA (Table 2). The regression coefficients showed that ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1 (PRPS1) expression was positively associated with EPA content in the muscle (Fig. 4). PRPS1 catalyzes the synthesis of phosphoribosylpyrophosphate (PRPP) that is essential for nucleotide synthesis. This may indicate that EPA stimulates nucleotide synthesis in muscle, although the cause-effect relationship is unknown. Nucleotides participate in nearly all biochemical processes in the body as for instance precursors for DNA and RNA, or energy, metabolic regulators, coenzymes and activated intermediates in biosynthesis51. The results therefore suggest that in a skeletal muscle rich in EPA, rather than entering glycolysis, the glucose-6-phosphate from breakdown of glycogen seems to be released as glucose, or shuttled into the PPP.

In conclusion, this study indicates that muscle EPA and DHA content has apparent links with carbohydrate metabolism in Atlantic salmon, as has previously been demonstrated in mammals.

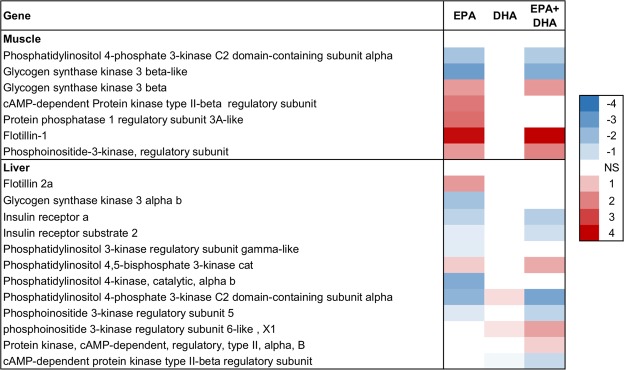

Insulin regulation in Atlantic salmon and its association with EPA and DHA

Skeletal muscle is a major site of insulin action, and muscle LC n-3 PUFA effects on insulin sensitivity has been observed in mice52, pigs53,54 and human23,24. Carnivorous fish possess an insulin-signaling system similar to mammals, although its role is not completely clarified49,50. In Atlantic salmon adipose tissue, insulin improves the differentiation capacity of preadipocytes towards mature adipocytes, similar to what happens in human adipose tissue55.

The enrichment analysis identified the insulin-signaling pathway as an enriched group for EPA, but not DHA, in both skeletal muscle and liver (Table 2), and expression of several genes related to insulin were associated with EPA content in skeletal muscle. In skeletal muscle, expression of the two genes phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 3-kinase C2 domain-containing subunit alpha-like, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit beta-like, in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) family were positively associated with EPA content (Fig. 5). PI3-kinases are known to play key roles in many signaling pathways in mammals56,57, including glucose uptake and insulin signaling58,59. Further, expression of cAMP-dependent protein kinase type II-beta regulatory subunit-like, which belongs to the protein kinase A (PKA) family of enzymes, was also positively associated with EPA. Studies in mammals have shown that a correct regulation of cAMP/PKA activity is crucial for glucose homeostasis and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity60. The gene expression of flotillins, which are considered as markers of lipid rafts and implicated in numerous signaling events, including insulin signaling61, increased in both skeletal muscle and liver with increasing content of EPA in muscle (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Insulin signaling in muscle and liver. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in skeletal muscle and liver. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association.

These results indicate that EPA is involved in insulin regulation in Atlantic salmon. This is in agreement with what was previously demonstrated in mammals25,52,62.

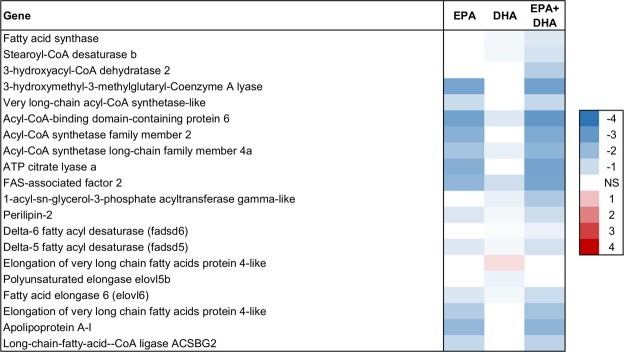

High skeletal muscle content of EPA and DHA was negatively associated with hepatic lipogenesis

Lipogenesis is the formation of lipids, and includes formation of triglycerides for storage as well as de novo lipogenesis of FAs. The crucial carbon source for de novo lipogenesis is acetyl-CoA formed in mitochondria from the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate or the oxidative degradation of some amino acids.

The analysis of the liver transcriptome showed that both EPA and DHA were associated with reduced expression of genes involved in lipogenesis (Fig. 6). For example, several acyl-CoA synthethases, fatty acid synthase (FAS), FAS-associated factor 2, as well as 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase gamma-like (GPAT1), a key enzyme for hepatic triglyceride synthesis. Several studies have shown reduced hepatic triglyceride synthesis with increasing dietary levels of EPA and/or DHA, both in mammals63,64 and salmonid fish including rainbow trout65 and Atlantic salmon66. Our study found an association between reduced lipogenesis and increased EPA in the skeletal muscle tissue of fish that received the same feed.

Figure 6.

Lipogenesis and fatty acid bioconversion in liver. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in liver. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association.

Although the cause-effect relationship cannot be determined, these results may indicate that increasing the skeletal muscle EPA and DHA content lowers the risk of developing fatty liver, which may promote health as fatty liver is recognized as a health problem in farmed Atlantic salmon67. However, this effect was not seen on the phenotype of the fish; the correlation between liver fat percentage and skeletal muscle EPA and DHA content was close to zero (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In skeletal muscle, expression of the key genes involved in lipogenesis were negatively associated with EPA, for instance 2-acylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 that catalyzes the formation of diacylglycerol, and acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC) that is involved in regulation of fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 7). These results indicate a possible inhibitory effect of EPA on lipogenesis in Atlantic salmon skeletal muscle, which has not been reported before.

Figure 7.

Lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. Association between EPA, DHA or EPA + DHA content in muscle and expression of genes in skeletal muscle. Color scale shows linear regression coefficients. NS = no significant association.

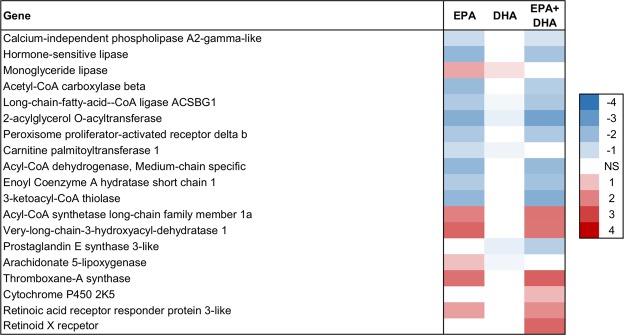

Lipid catabolism decreased with increasing EPA in skeletal muscle

Fatty acid catabolism is the major source of energy in salmonid fish. The process is termed β-oxidation, and occurs in the mitochondria and peroxisomes68. In Atlantic salmon, β-oxidation is an important source of energy in several tissues5,69,70. Increased EPA content in skeletal muscle was negatively associated with expression of lipid catabolic genes in both liver and skeletal muscle (Figs 7 and 8). DHA had weak associations compared to EPA.

In the liver, we observed that EPA was associated with reduced expression of the lipid catabolic genes monoglyceride lipase and phospholipase C (Fig. 8), as well as enoyl-CoA hydratase and Delta(3,5)-Delta(2,4)-dienoyl-CoA isomerase, which are both involved in β-oxidation. Expression of the mitochondrial β-oxidation biomarker carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), was also negatively associated with EPA.

In skeletal muscle, EPA and EPA + DHA were negatively associated with expression of three genes coding for β-oxidation enzymes: 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and enoyl Coenzyme A hydratase (Fig. 7). In addition, expression of PPAR β/δ, a central regulator of energy metabolism that stimulates genes of β-oxidation71,72, and CPT1, had negative associations with EPA.

Mitochondrial β-oxidation capacity is determined by many factors, for instance mitochondrial biogenesis and function in general. Expression of a number of mitochondrial genes were associated with EPA and DHA content in skeletal muscle, both positively and negatively, thus, the overall effect was difficult to determine, although the majority of the associations were negative (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genes classified in the GO functional group Mitochondrion that were significantly associated with the fatty acid traits.

| Trait | Total no. of associated genes | Negatively associated | Positively associated | Mean regression coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | ||||

| EPA | 268 | 154 | 114 | −0.06 |

| DHA | 176 | 128 | 48 | −0.19 |

| EPA + DHA | 192 | 116 | 76 | −0.11 |

| Liver | ||||

| EPA | 265 | 215 | 50 | −1 |

| DHA | 206 | 165 | 41 | −0.28 |

| EPA + DHA | 259 | 208 | 51 | −1.21 |

Increased EPA in the diet generally increases the content of EPA in both liver and skeletal muscle, and has been reported to result in increased FA oxidation in liver tissue in mammals73–76. In Atlantic salmon, however, there are varying results from feeding trials regarding the effect of high EPA and DHA on hepatic β-oxidation capacity77–79. Regarding skeletal muscle, Aas et al.23 reported that preincubation of human skeletal muscle cells with EPA decreased FA oxidation, which concurred with increased incorporation of EPA into complex cellular lipids. Thus, the variation in β-oxidation capacity observed in this study may reflect on the ratio between utilization of EPA for energy production and its deposition in skeletal muscle.

Overall, expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism decreased in both liver and skeletal muscle with increasing content of EPA and EPA + DHA in skeletal muscle.

Eicosanoids, resolvins and protectins

In the muscle, genes related to conversion of long chain FAS were positively associated with EPA and EPA + DHA. These included very-long-chain-3-hydroxyacyl-dehydratase 1, which catalyzes the third of the four reactions of the long-chain fatty acids elongation cycle, as well as long-chain Acyl-CoA synthetase (Fig. 7). This indicates further bio-conversion of EPA and DHA to very long chain n-3 PUFAs and possibly formation of resolvins and protectins. It has been suggested that resolvins and protectins are mediators of the beneficial effects of EPA on insulin signaling80,81. Expression of a few eicosanoid-related genes, such as Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX) and Thromboxane-A synthase, were positively associated with EPA (Fig. 7). Further, Cytochrome P450 was positively associated with EPA + DHA. ALOX metabolizes EPA to 5-hydroperoxy-EPA which is then converted to 5-series of Leukotriene products82. ALOX is also known to cooperate with other lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase cytochrome P450 enzymes in metabolic pathways that metabolize EPA to resolvins of the E series82. These results indicate that EPA and DHA contents of muscle are associated with skeletal muscle production of eicosanoids and resolvins.

What determines EPA and DHA content in skeletal muscle?

Individual differences in EPA and DHA content were observed in fish of similar size fed an identical diet. This individual variation may result from many factors, for instance individual differences in FA deposition, β-oxidation of FAs, omega-3 bioconversion in skeletal muscle, or uptake of these FAs from blood, which again can be influenced by omega-3 bioconversion in the liver and intestine, which are the major sites of omega-3 bioconversion in Atlantic salmon5.

In the current study, the hepatic expression of the fatty acid desaturase genes fadsd5 and fadsd6 was negatively associated with skeletal muscle level of EPA and DHA (Fig. 6). In the skeletal muscle, no desaturases or elongases involved in the omega-3 bioconversion pathway showed any association with either EPA or DHA (although fadsd5, fadsd6 and elovl5 were expressed in skeletal muscle tissue). This may point to factors other than omega-3 bioconversion which are more important for determining the EPA and DHA content in skeletal muscle. Albeit we cannot determine cause and effect based on the association analyses, our results point to reduced β-oxidation as a possible determining factor for EPA and the sum of EPA + DHA, since the individuals with the highest EPA and EPA + DHA content had a lower expression of β-oxidation genes. Studies in Atlantic salmon have shown that LC n-3 PUFAs given in surplus are oxidized for the production of energy83. Thus, our results suggest that the reason why some individuals have a higher level of EPA and DHA in the skeletal muscle is that these FAs are deposited rather than oxidized for energy.

Conclusions

The current study shows that there are big individual variations in EPA and DHA content of skeletal muscle between Atlantic salmon fed the same diet, and that these variations are associated with differences in expression of genes involved in nutrient metabolism. The main results are:

Correlations between liver and skeletal muscle were very low regarding both EPA and DHA content.

The correlation between EPA and DHA percentage in skeletal muscle was low, and over 50% more genes were associated with EPA than DHA. Also, the two FAs were associated with different gene expression profiles. This information is relevant for consideration of future feed production strategies, since several of new alternative feed ingredients contain either EPA or DHA, not both.

Skeletal muscle content of EPA and DHA was positively associated with muscle tissue development and function.

Skeletal muscle content of EPA and DHA was associated with carbohydrate metabolism. While increasing DHA content was concurrent with increased expression of genes in the glycolytic pathway and the production of pyruvate and lactate, EPA was associated with increased activity of the pentose phosphate pathway and nucleotide synthesis in addition to increased glycogen breakdown. Furthermore, skeletal muscle content of EPA, but not DHA, was associated with expression of genes involved in insulin signaling in both skeletal muscle and liver tissues.

EPA and DHA were associated with expression of genes involved in eicosanoid and resolvin production.

EPA was negatively associated with expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism, in both liver and muscle. Thus, a possible reason why some individuals have a higher level of EPA in the skeletal muscle is that they deposit - rather than oxidize - EPA for energy.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge SalmoBreed for providing access to data used in this study. The authors are grateful to Målfrid Tofteberg Bjerke for skillful technical assistance. This project was funded by the Norwegian research council (grant no. NFR 244200).

Author Contributions

A.K.S., B.R., T.H.E.M. conceived and designed the study. S.S.H., B.R., A.K.S., B.H. collected the data. S.S.H., A.K., H.M. analyzed the data. S.S.H., B.R., A.K.S., A.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to editing and revising the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since it contains commercially sensitive data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-40391-2.

References

- 1.Ytrestoyl T, Aas TS, Asgard T. Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway. Aquaculture. 2015;448:365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols PD, Glencross B, Petrie JR, Singh SP. Readily available sources of long-chain omega-3 oils: is farmed Australian seafood a better source of the good oil than wild-caught seafood? Nutrients. 2014;6:1063–1079. doi: 10.3390/nu6031063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprague M, Dick JR, Tocher DR. Impact of sustainable feeds on omega-3 long-chain fatty acid levels in farmed Atlantic salmon, 2006-2015. Sci Rep. 2016;6:9. doi: 10.1038/srep21892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bou M, et al. Requirements of n-3 very long-chain PUFA in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L): effects of different dietary levels of EPA and DHA on fish performance and tissue composition and integrity. Br. J. Nutr. 2017;117:30–47. doi: 10.1017/s0007114516004396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tocher DR. Metabolism and functions of lipids and fatty acids in teleost fish. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2003;11:107–184. doi: 10.1080/713610925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell JG, Henderson RJ, Tocher DR, Sargent JR. Replacement of dietary fish oil with increasing levels of linseed oil: Modification of flesh fatty acid compositions in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) using a fish oil finishing diet. Lipids. 2004;39:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodtkorb T, Rosenlund G, Lie Ø. Effects of dietary levels of 20:5n-3 and 22:6n-3 on tissue lipid composition in juvenile Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, with emphasis on brain and eye. Aquac. Nutr. 1997;3:175–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2095.1997.00085.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vegusdal A, Ostbye TK, Tran TN, Gjoen T, Ruyter B. beta-oxidation, esterification, and secretion of radiolabeled fatty acids in cultivated Atlantic salmon skeletal muscle cells. Lipids. 2004;39:649–658. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tocher DR, Bell JG, McGhee F, Dick JR, Fonseca-Madrigal J. Effects of dietary lipid level and vegetable oil on fatty acid metabolism in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) over the whole production cycle. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry. 2003;29:193–209. doi: 10.1023/B:FISH.0000045722.44186.ee. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monroig O, Tocher DR, Navarro JC. Biosynthesis of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Marine Invertebrates: Recent Advances in Molecular Mechanisms. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:3998–4018. doi: 10.3390/md11103998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruyter B, Thomassen MS. Metabolism of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in Atlantic salmon liver: stimulation by essential fatty acid deficiency. Lipids. 1999;34:1167–1176. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng XZ, Tocher DR, Dickson CA, Bell JG, Teale AJ. Effects of diets containing vegetable oil on expression of genes involved in highly unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in liver of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Aquaculture. 2004;236:467–483. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bou M, Ostbye TK, Berge GM, Ruyter B. EPA, DHA, and Lipoic Acid Differentially Modulate the n-3 Fatty Acid Biosynthetic Pathway in Atlantic Salmon Hepatocytes. Lipids. 2017;52:265–283. doi: 10.1007/s11745-017-4234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargent, J. R., Tocher, D. R. & Bell, J. G. In Fish Nutrition (eds Halver, J. E. & Hardy, R. W.) 190–193 (Academic press, 2002).

- 15.Berge, G. M. et al. Betydning av genetisk bakgrunn og ulike nivå av omega-3-fettsyrer i fôr i tidlig livsfaser for fiskehelse, fettsyresammensetning og muskelkvalitet ved slaktestørrelse. Nofima https://nofima.no/pub/1234578/ (2015).

- 16.Stillwell W, Wassall SR. Docosahexaenoic acid: membrane properties of a unique fatty acid. Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2003;126:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0009-3084(03)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calder PC. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83:1505S–1519S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Rubio L, et al. Functional Feeds Reduce Heart Inflammation and Pathology in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) following Experimental Challenge with Atlantic Salmon Reovirus (ASRV) PLoS One. 2012;7:17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowley AF, Knight J, Lloyd-Evans P, Holland JW, Vickers PJ. Eicosanoids and their role in immune modulation in fish—a brief overview. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 1995;5:549–567. doi: 10.1016/S1050-4648(95)80041-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wall R, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr. Rev. 2010;68:280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serhan CN, Chiang N. Endogenous pro-resolving and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators: a new pharmacologic genus. British journal of pharmacology. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S200–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature. 2007;447:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aas V, Rokling-Andersen MH, Kase ET, Thoresen GH, Rustan AC. Eicosapentaenoic acid (20: 5 n-3) increases fatty acid and glucose uptake in cultured human skeletal muscle cells. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:366–374. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500300-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeromson S, et al. Lipid remodeling and an altered membrane-associated proteome may drive the differential effects of EPA and DHA treatment on skeletal muscle glucose uptake and protein accretion. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2018;314:E605–E619. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00438.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hessvik NP, et al. Metabolic switching of human myotubes is improved by n-3 fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:2090–2104. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M003319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanza IR, et al. Influence of fish oil on skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics and lipid metabolites during high-fat diet. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;304:E1391–E1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00584.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens FB, et al. Fish oil omega-3 fatty acids partially prevent lipid-induced insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle without limiting acylcarnitine accumulation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;127:315–322. doi: 10.1042/cs20140031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeromson S, Gallagher IJ, Galloway SDR, Hamilton DL. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Skeletal Muscle Health. Mar. Drugs. 2015;13:6977–7004. doi: 10.3390/md13116977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Tonnac A, Labussiere E, Vincent A, Mourot J. Effect of alpha-linolenic acid and DHA intake on lipogenesis and gene expression involved in fatty acid metabolism in growing-finishing pigs. The British journal of nutrition. 2016;116:7–18. doi: 10.1017/s0007114516001392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmona-Antoñanzas G, Tocher DR, Martinez-Rubio L, Leaver MJ. Conservation of lipid metabolic gene transcriptional regulatory networks in fish and mammals. Gene. 2014;534:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell JG, et al. Replacement of fish oil with rapeseed oil in diets of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) affects tissue lipid compositions and hepatocyte fatty acid metabolism. J. Nutr. 2001;131:1535–1543. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordal AEO, et al. Dietary rapeseed oil affects the expression of genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) J. Nutr. 2005;135:2355–2361. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morais S, Taggart JB, Guy DR, Bell JG, Tocher DR. Hepatic transcriptome analysis of inter-family variability in flesh n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid content in Atlantic salmon. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leaver MJ, et al. Heritability and mechanisms of n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid deposition in the flesh of Atlantic salmon. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genomics Proteomics. 2011;6:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coccia E, et al. Fatty Acid-Specific Alterations in Leptin, PPAR alpha, and CPT-1 Gene Expression in the Rainbow Trout. Lipids. 2014;49:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11745-014-3939-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vestergren AS, et al. Sesamin Modulates Gene Expression Without Corresponding Effects on Fatty acids in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) Lipids. 2012;47:897–911. doi: 10.1007/s11745-012-3697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horn SS, Ruyter B, Meuwissen THE, Hillestad B, Sonesson AK. Genetic effects of fatty acid composition in muscle of Atlantic salmon. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2018;50:23. doi: 10.1186/s12711-018-0394-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Codabaccus BM, Bridle AR, Nichols PD, Carter CG. An extended feeding history with a stearidonic acid enriched diet from parr to smolt increases n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids biosynthesis in white muscle and liver of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Aquaculture. 2011;322–323:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng XZ, Tocher DR, Dickson CA, Bell JG, Teale AJ. Highly unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in vertebrates: New insights with the cloning and characterization of a Delta 6 desaturase of Atlantic salmon. Lipids. 2005;40:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mason ME, Waller GR. Dimethoxypropane Induced Transesterification of Fats and Oils in Preparation of Methyl Esters for Gas Chromatographic Analysis. Analytical Chemistry. 1964;36:583–586. doi: 10.1021/ac60209a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moghadam HK, et al. Impacts of Early Life Stress on the Methylome and Transcriptome of Atlantic Salmon. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5023. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05222-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seo M, et al. RNA-seq analysis for detecting quantitative trait-associated genes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:12. doi: 10.1038/srep24375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torstensen BE, Froyland L, Lie O. Replacing dietary fish oil with increasing levels of rapeseed oil and olive oil - effects on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) tissue and lipoprotein lipid composition and lipogenic enzyme activities. Aquac. Nutr. 2004;10:175–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2004.00289.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:3710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chu M, Gregorio CC, Pappas CT. Nebulin, a multi-functional giant. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2016;219:146–152. doi: 10.1242/jeb.126383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polakof S, Panserat S, Soengas JL, Moon TW. Glucose metabolism in fish: a review. Journal of comparative physiology. B, Biochemical, systemic, and environmental physiology. 2012;182:1015–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00360-012-0658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamalam BS, Medale F, Panserat S. Utilisation of dietary carbohydrates in farmed fishes: New insights on influencing factors, biological limitations and future strategies. Aquaculture. 2017;467:3–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews, C. K., Van Holde, K. E. & Ahern, K. G. Biochemistry 794–795 (Benjamin Cummings, 2000).

- 52.Storlien LH, et al. Influence of dietary-fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats – relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3-fatty-acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes. 1991;40:280–289. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.40.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardoso TF, et al. RNA-seq based detection of differentially expressed genes in the skeletal muscle of Duroc pigs with distinct lipid profiles. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9. doi: 10.1038/srep40005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puig-Oliveras A, et al. Differences in muscle transcriptome among pigs phenotypically extreme for fatty acid composition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Todorčević M, et al. Changes in fatty acids metabolism during differentiation of Atlantic salmon preadipocytes; Effects of n-3 and n-9 fatty acids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2008;1781:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cantley LC. The Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rameh LE, Cantley LC. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase lipid products in cell function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8347–8350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Falasca M, et al. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase C2alpha in insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28226–28236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katso R, et al. Cellular Function of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinases: Implications for Development, Immunity, Homeostasis, and Cancer. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2001;17:615–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang H, Yang L. Targeting cAMP/PKA pathway for glycemic control and type 2 diabetes therapy. Journal of molecular endocrinology. 2016;57:R93–r108. doi: 10.1530/jme-15-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Babuke T, Tikkanen R. Dissecting the molecular function of reggie/flotillin proteins. European journal of cell biology. 2007;86:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neschen S, et al. N-3 fatty acids preserve insulin sensitivity in vivo in a peroxisonte proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent manner. Diabetes. 2007;56:1034–1041. doi: 10.2337/db06-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lamaziere A, Wolf C, Barbe U, Bausero P, Visioli F. Lipidomics of hepatic lipogenesis inhibition by omega 3 fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2013;88:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parker HM, et al. Omega-3 supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hepatology. 2012;56:944–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvarez MJ, Diez A, Lopez-Bote C, Gallego M, Bautista JM. Short-term modulation of lipogenesis by macronutrients in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) hepatocytes. The British journal of nutrition. 2000;84:619–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leaver MJ, et al. Functional genomics reveals increases in cholesterol biosynthetic genes and highly unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis after dietary substitution of fish oil with vegetable oils in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) BMC Genomics. 2008;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sissener, N. T. B. et al. Oppdatering av utredningen: Effekter av endret fettsyresammensetning i fôr til laks relatert til fiskens helse, velferd og robusthet. 99 (NIFES and Nofima, Fiskeri og havbruksnæringens forskningsfond (FHF), 2016).

- 68.Schulz, H. In Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes (eds Vance, J. E. & Vance. D. E.) 134–147 (Elsevier Science, 2008).

- 69.Froyland L, Madsen L, Eckhoff KM, Lie O, Berge RK. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, carnitine palmitoyltransferase II, and Acyl-CoA oxidase activities in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Lipids. 1998;33:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Froyland L, Lie O, Berge RK. Mitochondrial and peroxisomal beta-oxidation capacities in various tissues from Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Aquac. Nutr. 2000;6:85–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2095.2000.00130.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leaver MJ, et al. Multiple peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta subtypes from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Journal of molecular endocrinology. 2007;38:391–400. doi: 10.1677/jme-06-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dressel U, et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta agonist, GW501516, regulates the expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism and energy uncoupling in skeletal muscle cells. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.) 2003;17:2477–2493. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flachs P, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine origin upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis and induce beta-oxidation in white fat. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2365–2375. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madsen L, et al. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid affect mitochondrial and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation in relation to substrate preference. Lipids. 1999;34:951–963. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsuzuki T, et al. Intake of conjugated eicosapentaenoic acid suppresses lipid accumulation in liver and epididymal adipose tissue in rats. Lipids. 2005;40:1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Willumsen N, Vaagenes H, Lie O, Rustan AC, Berge RK. Eicosapentaenoic acid, but not docosahexaenoic acid, increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and upregulates 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase gene expression in rats. Lipids. 1996;31:579–592. doi: 10.1007/BF02523828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kjær MA, Todorčević M, Torstensen BE, Vegusdal A, Ruyter B. Dietary n-3 HUFA Affects Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Capacity and Susceptibility to Oxidative Stress in Atlantic Salmon. Lipids. 2008;43:813–827. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stubhaug I, Froyland L, Torstensen B. E. beta-oxidation capacity of red and white muscle and liver in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) - Effects of increasing dietary rapeseed oil and olive oil to replace capelin oil. Lipids. 2005;40:39–47. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kjaer MA, Ruyter B, Berge GM, Sun YJ, Ostbye TKK. Regulation of the Omega-3 Fatty Acid Biosynthetic Pathway in Atlantic Salmon Hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2016;11:19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White PJ, Arita M, Taguchi R, Kang JX, Marette A. Transgenic restoration of long-chain n-3 fatty acids in insulin target tissues improves resolution capacity and alleviates obesity-linked inflammation and insulin resistance in high-fat-fed mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:3066–3073. doi: 10.2337/db10-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.White PJ, et al. Protectin DX alleviates insulin resistance by activating a myokine-liver glucoregulatory axis. Nature medicine. 2014;20:664–669. doi: 10.1038/nm.3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qu Q, Xuan W, Fan GH. Roles of resolvins in the resolution of acute inflammation. Cell biology international. 2015;39:3–22. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stubhaug I, Lie O, Torstensen BE. Fatty acid productive value and beta-oxidation capacity in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) fed on different lipid sources along the whole growth period. Aquac. Nutr. 2007;13:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2007.00462.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since it contains commercially sensitive data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.