Abstract

PLA2G6‐associated neurodegeneration comprises a heterogeneous spectrum of age‐related phenotypes, with three forms classically recognized, including infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD) with onset in infancy, atypical neuroaxonal dystrophy (atypical NAD) with onset in childhood, and dystonia‐parkinsonism (PARK14) with onset in early adulthood. We describe 3 cases that challenge this view, discuss the related literature, and suggest that PLA2G6 mutations cause a phenotypic continuum rather than three discrete phenotypes, further ensuing clinical implications.

Keywords: PLA2G6, NBIA, PLAN, iron accumulation, PARK14

Fueled by the advances in the field of genetics, our understanding of the clinical presentations and the underlying pathophysiology of syndromes summarized as neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) has expanded considerably.1 PLA2G6‐associated neurodegeneration (PLAN; also referred to as NBIA2) is one of the major subtypes of NBIA and comprises a heterogeneous spectrum of age‐related phenotypes (Table 1), with three forms recognized, which include infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD) with onset in infancy, atypical neuroaxonal dystrophy (atypical NAD) including Karak syndrome (e.g., slowly progressive ataxia associated with cognitive decline) with onset in childhood, and dystonia‐parkinsonism (PARK14) in the absence of prominent ataxia or sensory disturbances with onset in adulthood.1, 2, 3, 4 Infantile presentation accounts for the majority of cases (up to 85%), whereas other phenotypes, particularly atypical NAD, are much less frequently described.1, 2, 3 Although such clinical classification can be useful on practical grounds, it has been increasingly recognized that PLAN can manifest with intermediate phenotypes,1, 2, 3, 4, 5 which only partially match those classically associated with this disorder.

Table 1.

Summary of the main features of the age‐related phenotype associated with PLAN

| INAD | Atypical NAD | Atypical NAD (Karak Variant) | PARK14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | Infancy (before age 3 years) | Childhood (mean: 4–5 years; but can be as late as 20 years) | Childhood | Early adulthood |

| Main features |

–Psychomotor regression –Truncal hypotonia followed by spastic tetraparesis –Optic atrophy –Histopathological evidence of dystrophic axons |

–Psychomotor regression –Gait abnormalities –Language difficulties and autistic‐like behavior |

–Ataxia |

–l‐dopa responsive parkinsonism with development of dyskinesia –Dystonia –Cognitive decline |

| Additional clinical features |

–Nystagmus –Strabismus –Ataxia –Bulbar dysfunction –Seizures |

–Dystonia –Spasticity (without preceding hypotonia) –Nystagmus –Seizures |

–Cognitive impairment –Optic atrophy |

–Dysarthria –Autonomic involvement |

| Clinical progression | Rapid (death usually occurs in the first decade) | Fairly stable during childhood (deterioration is then usually observed between ages 7 and 12) | Slowly progressive | Progressive |

Here, we describe three cases, which suggest a phenotypic continuum rather than a discrete presentation of one form, and discuss the related literature ensuing clinical implications.

Case 1

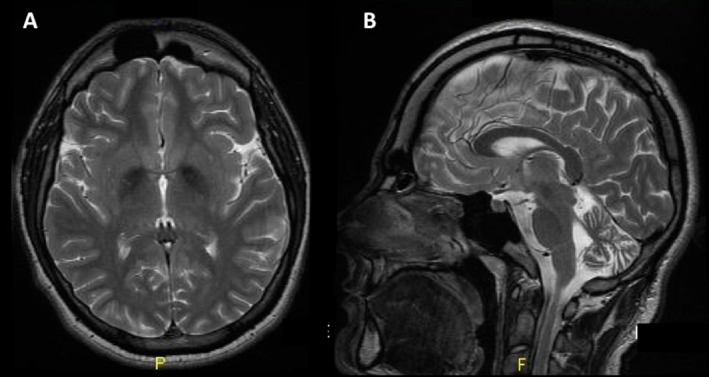

This currently 24‐year‐old man attained normal milestones during the first 2 years of life, but was noticed to be clumsy and prone to fall. By the age of 6, he also started having learning and behavioral difficulties, though he could attend normal primary schools. His gait progressively worsened and he sought medical advice at the age of 13 years. Examination revealed ataxia of gait and unsteady stance. Finger‐nose‐finger test was mildly abnormal on both sides (right>left), and reflexes were brisk bilaterally. A brain MRI showed marked atrophy of the cerebellum, with associated hypointensity of the globus pallidus bilaterally on T2‐weighted images (Fig. 1). Genetic screening for NBIAs was therefore pursued: After PANK2 testing had been revealed inconclusive, he was found to carry one previously described (c.1771C>T; p.R591W)6 and one novel mutation (c.1877C>T; p.S626L) in the PLA2G6 gene.

Figure 1.

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) MRI T2 sequences showing reduced signal in the globus pallidus bilaterally (suggesting iron accumulation) and cerebellar atrophy, respectively.

Symptoms were very slowly progressive and dominated by the neurobehavioral aspects (e.g., anxiety, isolation, and difficulty in relating to peers), but in the subsequent 2 years, he further started to slow down and complain about muscle stiffness. Examination at the age of 22 years revealed a mild parkinsonian syndrome featuring hypomimia, hypophonia, bradykinesia, and rigidity (right>left). Moreover, he had a short‐stepped gait, with unsteadiness on turning and difficulties in tandem walking (see Video 1, Segment 1). Additionally, he had mild dysdiadochokinesia and dysmetria on the index‐nose test. A dopamine transporter scan was found to be abnormal. Levodopa therapy (300 mg/day) improved his parkinsonian symptoms, without development of dyskinesia during a follow‐up period of 1.5 years.

Case 2

This 18‐year‐old patient has had walking difficulties with a lack of coordination and unsteadiness, and poor fine motor skills ever since. Her initial clinical findings and progression until age 14 have been described in detail elsewhere,7 along with radiological and genetic results (c.691G>C, p.G231R; c.2370T>G, p.Y790*). Examination at the age of 17 revealed mild hypomimia and hypophonia, and limb bradykinesia. Cerebellar signs comprised eye movements with broken pursuit, dysmetric saccades and nystagmus on lateral gaze, and dysmetria on finger‐nose testing. There was mild dystonic posturing of the arms, and a spastic paraparesis and neuropathy of the legs with absent deep tendon reflexes. The most striking feature, however, was a peculiar gait pattern, which reflected a mix of spasticity, weakness, dystonia, and ataxia.

Case 3

This 25‐year‐old woman is the second of four siblings, the third of whom suffers from PLAN characterized by parkinsonism, dystonia, pyramidal signs, and cognitive impairment.8 Her milestones and schooling were unremarkable. When we reported on her brother in 2009, she was unaffected. To date, she herself has no complaints, but was noted on examination to have difficulties with balance and walking. Indeed, the predominant features were cerebellar signs, such as a dysarthric, scanning speech, lingual and limb dysdiadochokinesia (more pronounced on the left), and very mild gait ataxia, with difficulties in tandem gait (see Video 1, Segment 2). There was only a mild lack of facial expression and mild bradykinesia on the right. Furthermore, her lower‐limb reflexes were brisk bilaterally with ankle clonus. Her MRI brain scan showed mild generalized cerebral volume loss, including cerebellar atrophy and minimal iron deposition in the SN, which, however, was deemed excessive for her age. Genetic testing confirmed the presence of the homozygous c.2239C>T (p.R747W) mutation.

Discussion

All 3 cases have features overlapping with the classical, age‐related, PLAN phenotypes. In fact, except for the early onset (i.e., 2 years), case 1 did not have the typical clinical features of INAD (i.e., optic atrophy, truncal hypotonia, strabismus, psychomotor regression, and/or speech difficulties); instead, he displayed the clinical picture of what has been termed Karak syndrome, a variant of atypical NAD, the onset of which is later in childhood (mean age: 4.4 years).1, 2, 3 Beyond mild ataxia, our patient manifested also social and behavioral difficulties, which were actually one of his main complaints. A recent case has been described with a similar neurobehavioral profile, suggesting that this might be a feature more common than previously reported.9 Moreover, he also manifested a juvenile‐onset (14‐15 years) l‐dopa responsive parkinsonism, with evidence of nigrostriatal degeneration. Similarly, case 2 had an early‐onset, slowly progressive, cerebellar syndrome with additional spasticity, and subsequent parkinsonism in her late teens. Moreover, case 3 also featured both cerebellar ataxia and (minimal) parkinsonism, despite that her symptoms developed as noticeable much later, namely, in her third decade of life, when the PARK14 phenotype is more likely to develop.

Our series contrasts with the perception that PLAN has distinct age‐related phenotypes, but rather suggests a continuous phenotypic spectrum with variable age at onset.3, 6 For instance, it is shown here that parkinsonism can occur also in early‐onset PLAN variants and much earlier than classically reported for patients with PARK14 (cases 1 and 2). Moreover, case 3 demonstrates that late‐onset variants may display ataxia as the main feature, arguably implying that PARK14 patients might have cerebellar sign on examination. It is important to remark that all our 3 patients had cerebellar involvement given that a recent appraisal of 11 PLA2G6 cases has shown that ataxia is one of the core features of PLAN, and that cerebellar atrophy is the earliest imaging feature, preceding brain iron accumulation.10 This suggests that PLAN should be considered in the differential diagnosis of early‐onset ataxia syndromes, even in the absence of iron accumulation on specific sequences (i.e., gradient echo T2* and/or susceptibility weighted images). In all our cases, iron accumulation was evident in the globus pallidus or in the SN, and this represented a crucial clue to lead the genetic analyses in cases 1 and 2 who had, in the first place, a pure cerebellar syndrome, and suggested the diagnosis in the other patient (case 3), who already had a family history of PLAN.

The phenotypic heterogeneity of PLAN is not entirely explained by the underlying genetic variants. Although missense mutations are usually associated with less‐severe NAD phenotypes, it is noteworthy that case 1 carried a mutation (c.1771C>T) previously reported in “classical” INAD.6 Besides mutation type and location, other factors (yet undetermined) are likely to influence the clinical phenotype. In fact, clinical heterogeneity was also evident between case 3 and her brother. The latter, reported in detail elsewhere,8 had, in fact, a pure PARK14 phenotype at a younger onset. Ten years into disease progression, he showed a worsening of his dystonia‐parkinsonism with loss of ambulation and further development of swallowing difficulties, but no clear signs of cerebellar involvement on examination and imaging.

In summary, we report on 3 cases displaying clinical features, which overlap with the three classic phenotypes of PLAN. This observation suggests that: (1) PLAN would comprise a continuous spectrum of phenotypes; (2) PLAN should be considered in the differential diagnosis of childhood and adulthood onset (presumably recessive) ataxic syndromes; and (3) cerebellar involvement on clinical examination and/or neuroradiology might potentially be a clue for suspecting PLAN in early‐onset dystonia‐parkinsonism syndromes.

Author Roles

(1) Clinical Project: A. Conception; B. Execution; (2) Clinical Assessment and Data; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft; B. Review and Critique.

R.E.:1A, 1B, 2, 3A

B.B.: 1B, 2, 3A

M.A.K.: 2, 3B

F.B.: 2, 3B

M.P.: 2, 3B

P.B.: 2, 3B

K.P.B.: 1A, 2, 3B

M.T.P.: 1B, 2, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: B.B. holds a grant from the Gossweiler Foundation. F.B. has received travel grants from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society; holds an ENS fellowship; and has received a restricted grant by Merz pharma Switzerland. M.P. has received honoraria from University of Salerno, Italy. P.B. has received honoraria from University of Salerno, Italy and has held consultancies and advisory board membership with Novartis, Schwarz Pharma/UCB, Merck‐Serono, Eisai, Solvay, General Electric, and Lundbeck. K.P.B. has received funding for travel from GlaxoSmithKline, Orion Corporation, Ipsen, and Merz Pharmaceuticals; holds a grant from the Gossweiler Foundation; and has received royalties from Oxford University Press.

Supporting information

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video S1. Segment 1: Case 1: Bradykinesia on finger and foot tapping (right>left). Gait is short stepped with reduced arm swing. He is unsteady especially on turning. Tandem gait is almost impossible. Segment 2: Case 3: She is hypomimic and bradykinesia is demonstrated on finger tapping with left hand. Mild bilateral dysmetria with terminal tremor on finger‐nose‐finger testing. Gait is unsteady, and tandem gait is almost impossible.

Acknowledgment

The authors are very thankful to the patients, who signed a consent form for publication of their video.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

Drs. Roberto Erro and Bettina Balint contributed equally as first authors.

Profs. Kailash P. Bhatia and Maria Teresa Pellecchia contributed equally as senior authors.

Contributor Information

Roberto Erro, Email: erro.roberto@gmail.com.

Kailash P. Bhatia, Email: k.bhatia@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1. Schneider SA, Bhatia KP. Excess iron harms the brain: the syndromes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). J Neural Transm 2013;120:695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurian MA, Hayflick SJ. Pantothenate kinase‐associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) and PLA2G6‐associated neurodegeneration (PLAN): review of two major neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) phenotypes. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013;110:49–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurian MA, Morgan NV, MacPherson L, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of neurodegeneration associated with mutations in the PLA2G6 gene (PLAN). Neurology 2008;70:1623–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karkheiran S, Shahidi GA, Walker RH, Paisán‐Ruiz C. PLA2G6‐associated dystonia‐parkinsonism: case report and literature review. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2015;5:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshino H, Tomiyama H, Tachibana N, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of patients with PLA2G6 mutation and PARK14‐linked parkinsonism. Neurology 2010;75:1356–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Illingworth MA, Meyer E, Chong WK, et al. PLA2G6‐associated neurodegeneration (PLAN): further expansion of the clinical, radiological and mutation spectrum associated with infantile and atypical childhood‐onset disease. Mol Genet Metab 2014;112:183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu Y, Jiang Y, Gao Z, et al. Clinical study and PLA2G6 mutation screening analysis in Chinese patients with infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paisan‐Ruiz C, Bhatia KP, Li A, et al. Characterization of PLA2G6 as a locus for dystonia‐parkinsonism. Ann Neurol 2009;65:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cif L, Kurian MA, Gonzalez V, et al. Atypical PLA2G6‐associated neurodegeneration: social communication impairment, dystonia and response to deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2014;1:128–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salih MA, Mundwiller E, Khan AO, et al. New findings in a global approach to dissect the whole phenotype of PLA2G6 gene mutations. PLoS One 2013;8:e76831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video S1. Segment 1: Case 1: Bradykinesia on finger and foot tapping (right>left). Gait is short stepped with reduced arm swing. He is unsteady especially on turning. Tandem gait is almost impossible. Segment 2: Case 3: She is hypomimic and bradykinesia is demonstrated on finger tapping with left hand. Mild bilateral dysmetria with terminal tremor on finger‐nose‐finger testing. Gait is unsteady, and tandem gait is almost impossible.