Abstract

Flaxseed cake contains cyanogenic glucosides, which can be metabolized into hydrocyanic acid in an animal's body, leading to asphyxia poisoning in cells. Beta-glucosidase is highly efficient in degrading cyanogenic glucosides. The Cattle may have β-glucosidase-producing strains in the intestinal tract after eating small amounts of flaxseed cake for a long time. This study aimed to isolate of a strain from cow dung that produces β-glucosidase with high activity and can significantly reduce the amount of cyanogenic glucosides. We used cow dung as the microflora source and an esculin agar as the selective medium. After screening with 0.05% esculin and 0.01% ferric citrate, we isolated 5 strains producing high amounts of β-glucosidase. In vitro flaxseed cake fermentation was fermented by these 5 strains, in which the strain M-2 exerted the best effect (P < 0.05). The strain M-2 was identified as Lichtheimia ramosa and used as the fermentation strain to optimize the fermentation parameters by a single factor analysis and orthogonal experimental design. The optimum condition was as follows: inoculum size 3%, water content 60%, time 144 h, and temperature 32 °C. Under this condition, the removal rate of cyanogenic glucosides reached 89%, and crude protein increment reached 44%. These results provided a theoretical basis for the removal of cyanogenic glucosides in flaxseed and the comprehensive utilization of flaxseed cake.

Keywords: Flaxseed cake, Cyanogenic glycosides, Fermentation, β-glucosidase, Crude protein, Lichtheimia

1. Introduction

Flax is an annual plant roughly divided into fiber flax, oil flax, and dual-purpose type flax (Gao et al., 2010). The residue obtained after pressing flaxseeds is flaxseed cake. It is widely used in food additives, animal feeds, and crop cultivation, because it is rich in dietary fiber, essential amino acids, and many other active components. However, it's utilization was limited due to the existence of phytic acid, aminoglycosides, and other anti-nutritional factors, especially cyanogenic glycosides (Ganorkar and Jain, 2013, Russo and Reggiani, 2014). It was only added to the ruminant feed in animal production (Sun, 2010).

Researchers worldwide have made immense efforts to degrade cyanogenic glycosides using varied methods such as poaching, squeezing, solvent-based method, and microwave-based method (Sun and Xu, 2007, Wu et al., 2008, Lan, 2012). However, these methods have certain limitations such as high cost or having chemical residue. As a result, these methods have not been used in industrial production. Studies indicate that the β-glucosidase has a notable degrading effect on cyanogenic glycosides. Hence, researchers used natural β-glucosidase-producing strains for specific degradation of cyanogenic glycosides, and the results were significant (Ivanov et al., 2012, Feng et al., 2003). Moreover, this method had the advantages of simplicity, mild reaction conditions, and low cost. The fermentation detoxification method has been successfully used for detoxification in edible plants (Russo and Reggiani, 2014, Vasconcellos et al., 2009). Previous researchers screened a number of bacteria capable of degrading gossypol in cottonseed meal and were able to meet feed quality standards after fermentation (Zhu et al., 2010).

The untreated flaxseed cake can be used as a feed supplement in the ruminant (cattle) diets without any adverse reactions. Therefore, it is inferred that cattle may have β-glucosidase-producing strains in the digest tract after they eat small amounts of flaxseed cake for a long time. Moreover, β-glucosidase can degrade esculin into escin, which gives a black color when treated with Fe3+ and can be used for screening (Pérez et al., 2011, Hyunsu et al., 2017). This study used cow dung as the microflora source and an esculin medium as the selective medium for β-glucosidase-producing strains. After separation, the cultured strains underwent molecular biological identification. The activity of β-glucosidase was determined by the para-niteophenyl β-D-glucoside (p-NPG) method, and the strain with the best effect was identified using an orthogonal experimental design.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Screening of β-glucosidase-producing stains

For primary screening, samples were collected from the Gaolan dairy farm (36°51′N, 104°14′E; Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China), August, 2014. Cow dung was collected from cows not fed flaxseed cake and cows had been fed long-term flaxseed cake from the ground. Collected cow dung was stored at 4 °C for 1 d. Then, 5 g of the samples was ten-fold serially diluted to 1/1,000 and plated on the Luria–Bertani (LB)-esculin medium (1% peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, 1.5% agar, 0.05% esculin, and 0.01% ferric citrate) and potato dextrose agar (PDA)-esculin medium (2% glucose, 2% agar, 0.05% esculin, and 0.01% ferric citrate) (Cho et al., 2005, Qin et al., 2011, Nielsen and Sørensen, 1997). The LB-esculin medium cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The PDA-esculin medium cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. Single colonies with black halos were picked and streaked onto an LB or a PDA slant (Liang et al., 2014).

2.2. Strain identification

The isolated bacteria were incubated in the LB liquid medium at 37 °C and 180 r/min for 24 h and observed under a microscope according to the classical Gram staining (Shrivastava, 2011). The isolated bacteria were identified by a series of physiological and biochemical tests according to the common bacterial system identification manual (Dong and Cai, 2001), including Voges-Proskauer test, fermentation of carbohydrates and alcohol, indole test, urease test, L-tyrosine hydrolysis test, sodium malonic acid hydrolysis test, and so on. After purification of fungi, the samples were incubated on the PDA medium for 72 h, and the characteristics of mycelia and spore were observed under the microscope according to the insert method (Archana et al., 2012). Molecular identification was performed by a ribosomal DNA (rDNA) internal spacer (16S rDNA or internal transcribed spacer [ITS]) region sequencing using 16S rDNA universal primers: Pf2, 5′-AGAGTTTG ATCATGGCTCAG-3'; Pr2, 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3' (Polz and Cavanaugh, 1998); ITS universal primers: ITS1, 5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3'; ITS4, 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3'. The 16S rDNA or ITS was amplified from genomic DNA, purified, sequenced, and analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) program from National Center for Biotechnology Information. The polymerase chain reaction procedures were performed as description by Tao et al. (2004). The phylogenetic tree was generated using the Neighbor-Joining Algorithm in the MEGA7.0 software. Then the physiological and biochemical characteristics of these strains were analyzed and compared with those of the respective model strains to further determine the kinds of bacterial species (Sun et al., 2011, Stock and Wiedemann, 1998, Brenner et al., 1978).

2.3. Beta-glucosidase enzyme activity assay

First, the standard curve of para-nitrophenol (pNP) was plotted. The pNP solution (1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 mmol/L) was prepared using acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0, 0.2 mol/L). The mixture containing 0.1 mL of pNP solution and 0.9 mL of acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0, 0.2 mol/L) was incubated at 45 °C for 30 min in a water bath. Then, 2 mL of sodium carbonate solution (0.5 mol/L) and 9 mL of distilled water were added. The different concentrations of pNP were reflected by changes in the absorbance at 400 nm.

The isolated cultures were incubated at 37 °C (bacteria) or 28 °C (fungi) and 180 r/min for 72 h. The crude enzyme extract was obtained by centrifuging the liquid mixture at 1,000× g and 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. The mixture containing 0.1 mL of crude enzyme, 0.2 mL of p-NPG solution (5 mmol/L), and 0.7 mL of acetic acid–sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0, 0.2 mol/L) was incubated at 45 °C for 30 min in a water bath. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 mL of sodium carbonate solution (0.5 mol/L) and 9 mL of distilled water to the mixture, boiling it for 3 min, and cooling in an ice bath. The pNP concentration was reflected by changes in the absorbance at 400 nm.

One unit of β-glucosidase enzyme activity was determined as the amount of enzyme needed to produce 1 μmol pNP per min using p-NPG as the substrate.

2.4. Screening of the fermentation strain

We weighed 8 g of flaxseed cake into a flask UV sterilization for 1 h fermentation. The initial aerobic fermentation condition was as follows: water content 60%, inoculum concentration 5% (wt/wt), time 6 d, and temperature 37 °C (bacteria) or 28 °C (fungi). The flaxseed cake was fermented and detoxified with the selected strains. After fermentation, the amount of residual cyanogenic glycosides was determined by silver nitrate titration (Ivanov et al., 2012). The cyanogenic glycoside removing effects of each strain were compared, and one fungus with the highest removal rate of cyanogenic glycosides was selected as the fermentation strain. Then, the optimum growth temperature and pH of this fungus was further explored. The dry weight method was used to measure the biomass content (Xu, 2005). The procedures were as follows: 1) the spore suspension (1 × 105/mL, 3 mL) was added to an Erlenmeyer flask containing 47 mL of PDA liquid medium. The mixture was incubated at different temperatures and different pH at 180 r/min for 48 h; 2) the biomass was obtained by centrifuging the cultures at 4,000× g and 4 °C for 15 min; 3) the sediment was collected, rinsed with distilled water, and centrifuged at 4,000 × g and 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was discarded. This procedure was repeated 3 times. The final sediments were dried in an oven at 80 °C and weighed twice during the drying until there was no difference between 2 times of weighing, and the weight was recorded. The temperature gradient was set to 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, and 34 °C, and the pH gradient was set to 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

2.5. Optimization of fermentation detoxification conditions

The fermentation time, temperature, water content, and inoculation quantity are considered as the key influencing factors in the microbial fermentation of flaxseed cake (Wang, 2007). These 4 factors were selected to determine the optimum process conditions, and the crude protein increment evaluation was used as the index while studying the fermentation process by a single factor analysis and an orthogonal experimental design, which was shown in Table 1 (Yin et al., 2011, Zhou, 2002). Crude protein content was determined by the direct distillation (Wang, 2008).

Table 1.

Factors and levels in orthogonal array design.

| Levels | Temperature (A), °C | Time (B), d | Water content (C), % | Inoculum concentration (D), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 6 | 50 | 1 |

| 2 | 28 | 7 | 60 | 3 |

| 3 | 32 | 8 | 70 | 5 |

3. Results

3.1. Screening of β-glucosidase-producing strains and morphological observation

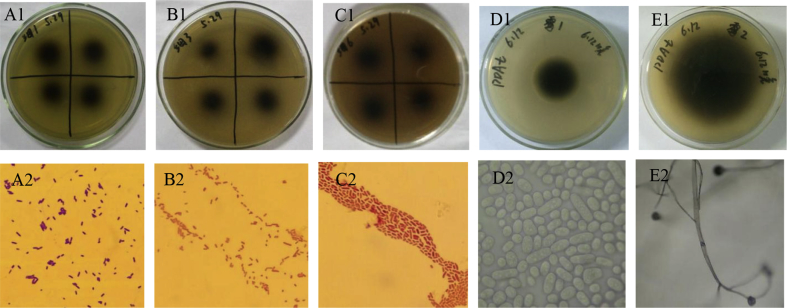

Five strains with larger ratio of black halo diameter to colony diameter (H/C) were isolated after screening using LB-esculin medium and PDA-esculin medium plates. Three strains, named X-1, X-3, X-6, were of bacteria, and 2 strains, named M-1, M-2, were of fungi. The screening results and the morphological characteristics of these strains are shown in Fig. 1: Strain X-1: the bacterium was bacilliform with negative coloring; the surface colonies on medium were circular in shape, creamy-white, moist, and uplifted; and the edge was smooth. Strain X-3: the bacterium was bacilliform with negative coloring, no spores, and no flagellum; the surface colonies on medium were circular in shape, creamy-white, moist, and uplifted; and the edge was smooth. Strain X-6: the strain was Gram negative and bacilliform with no spores or capsule; the edge was smooth; and the colony was thin, translucent, and white in the center. Strain M-1: the colony was round, white, and flat and with a white point in the center; and the hyphae were fluffy; the hyphae were fissiparous, and the spores were single or agminated under the microscope. Strain M-2: the colony was round and white with irregular edges; the hyphae were fluffy, and a black formation was found on the top of the hyphae; spore cysts were colorless or black, and mostly spherical.

Fig. 1.

Screening results and morphology of isolated strains. (A1) Strain X-1 grown on a primary screening medium plate. (A2) Cell morphology of strain X-1 (100×). (B1) Strain X-3 grown on a primary screening medium plate. (B2) Cell morphology of strain X-3 (100×). (C1) Strain X-6 grown on a primary screening medium plate. (C2) Cell morphology of strain X-6 (100×). (D1) Strain M-1 grown on a primary esculin screening medium plate. (D2) Mycelium and sporangium characteristics of M-1 (100×). (E1) Strain M-2 grown on a primary esculin screening medium plate. (E2) Mycelium and sporangium characteristics of M-2 (10×).

3.2. Identification of microbes

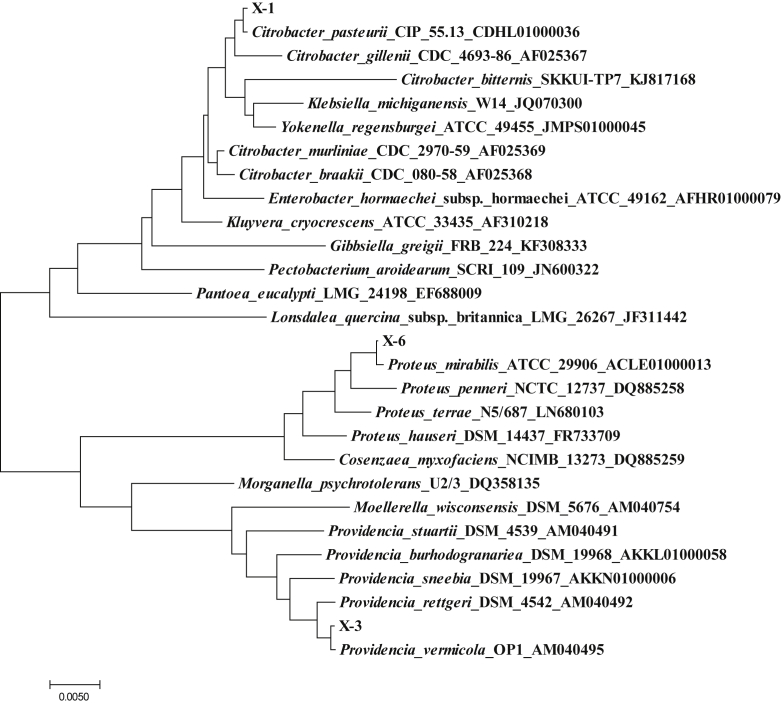

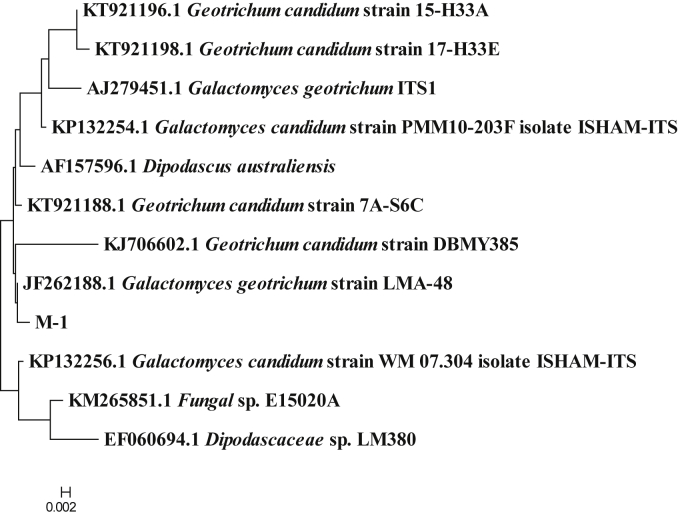

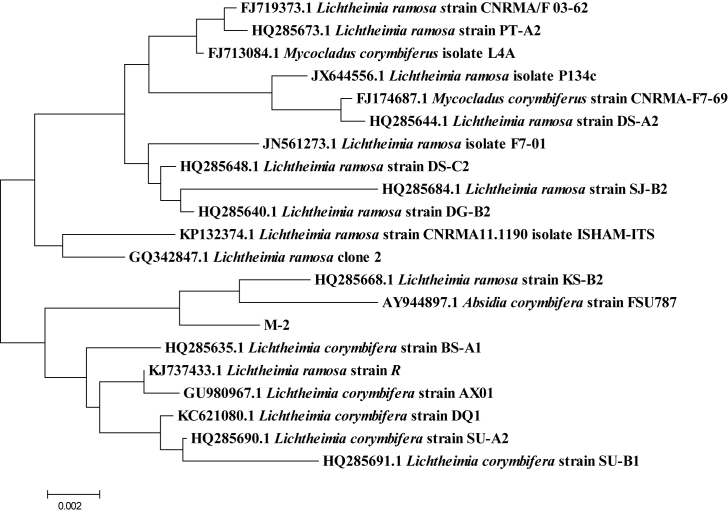

The DNA sequence analysis showed that the nucleotide sequence of X-1 had a 99% similarity with the reported sequence of Citrobacter, the nucleotide sequence of X-3 had a 99% similarity with the reported sequence of Providencia, the nucleotide sequence of X-6 had a 99% similarity with the reported sequence of Proteus, the nucleotide sequence of M-1 had a 99% similarity with the reported sequence of Geotrichum candidum, and the nucleotide sequence of M-2 had a 99% similarity with the reported sequence of Lichtheimia ramosa. All E-values of BLAST were 0.0. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining Algorithm of the MEGA7.0 software, and the results are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4. Combined with morphological observation, it was concluded that X-1 was Citrobacter, X-3 was Providencia, X-6 was Proteus, M-1 was G. candidum, and M-2 was L. ramosa. Since the aforementioned 3 bacterial genera contained different taxa, the physiological and biochemical characteristics of these 3 strains were analyzed. The results are shown in Table 2. The analysis of the results showed that X-1 was Citrobacter freundii, X-3 was Providencia rettgeri, and X-6 was Proteus vulgaris.

Fig. 2.

The phylogenetic tree of strains X-1, X-3 and X-6. It was constructed by the Neighbor-Joining method. The scale bar represents 0.005 nucleotide substitution per position.

Fig. 3.

The phylogenetic tree of strain M-1. It was constructed by the Neighbor-Joining method. The scale bar represents 0.002 nucleotide substitution per position.

Fig. 4.

The phylogenetic tree of strain M-2. It was constructed by the Neighbor-Joining method. The scale bar represents 0.002 nucleotide substitution per position.

Table 2.

Results of physiological and biochemical tests of the isolated bacteria and fungi.

| Item | X-1 | Citrobacter freundii | X-3 | Providencia rettgeri | X-6 | Proteus vulgaris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voges-Proskauer test | – | – | ||||

| Indole test | – | – | + | + | + | + |

| H2S test | + | + | ||||

| Malonic acid test | – | – | ||||

| D-adonitol test | – | – | ||||

| Urease test | + | + | ||||

| Inositol test | + | + | ||||

| Adonitol test | + | + | ||||

| Arab alcohol | + | + | ||||

| L‐rhamnose test | – | – | ||||

| Heptoside test | + | + | ||||

| Maltose test | + | + | ||||

| Salicin test | + | + | ||||

| Xylose test | + | + |

+: positivity; −: negativity.

3.3. Comparison of enzyme activities of isolated strains

The experimental results indicated that the enzyme activity of β-glucosidase in strain M-1 was 3.54 U/mL which was the highest among all strains, followed by 3.19 U/mL of strain M-2. The enzyme activities of X-1, X-3 and X-6 were 2.45, 2.42 and 2.51 U/mL respectively. Overall, the enzyme production capacity of fungi was higher than that of bacteria (Table 3).

Table 3.

Beta-glucosidase production by different strains1.

| Species | β-glucosidase enzyme activity, U/mL | Relative enzyme activity, % |

|---|---|---|

| X-1 | 2.45a | 69.2 |

| X-3 | 2.42a | 68.6 |

| X-6 | 2.51a | 70.9 |

| M-1 | 3.55ab | 100.0 |

| M-2 | 3.19b | 90.1 |

a, b Values with different letters along the column indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

The production was at 72 h of incubation and 37 °C (for strains X-1, X-3 and X6 of bacteria) or 28 °C (for striains M-1 and M2 of fungi).

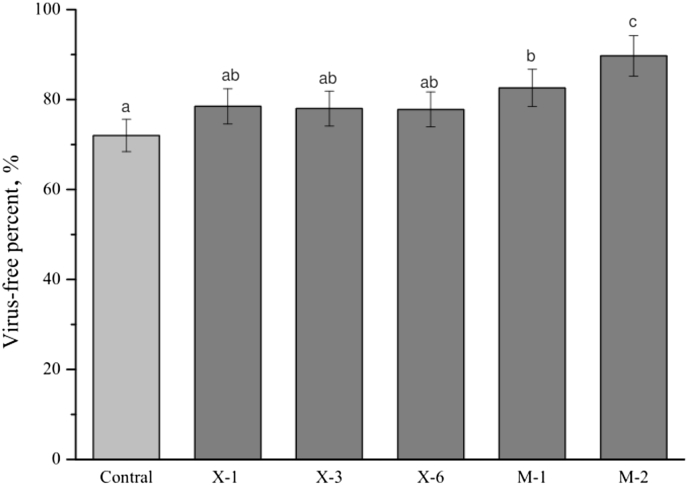

3.4. Screening of the fermentation strain

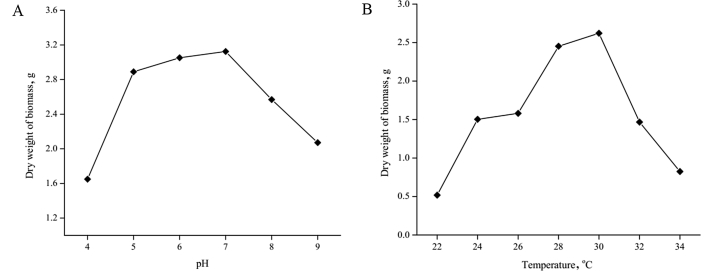

The analysis showed that the degradation rates of X-1, X-3 and X-6 for cyanogenic glycosides were almost the same as that of the control group. The cyanogenic glycoside removal rates of X-1, X-3 and X-6 were 76.668%, 75.832% and 75.687%. And, the cyanogenic glucoside removal rates of M-1 and M-2 were 81.674% and 87.783%, respectively. Virus-free rates were significantly improved compared with that of the control group (Fig. 5). It showed that the optimum growth condition of M-2 is pH 7 and 30 °C (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Virus -free percent of all strains. Results are the average of 3 replicates, and the bars indicate the standard error of 3 replicates. a, d, c Values with different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Effect of pH (A) and temperature (B) on the cell growth of stain M-2 at 180 r/min for 48 h.

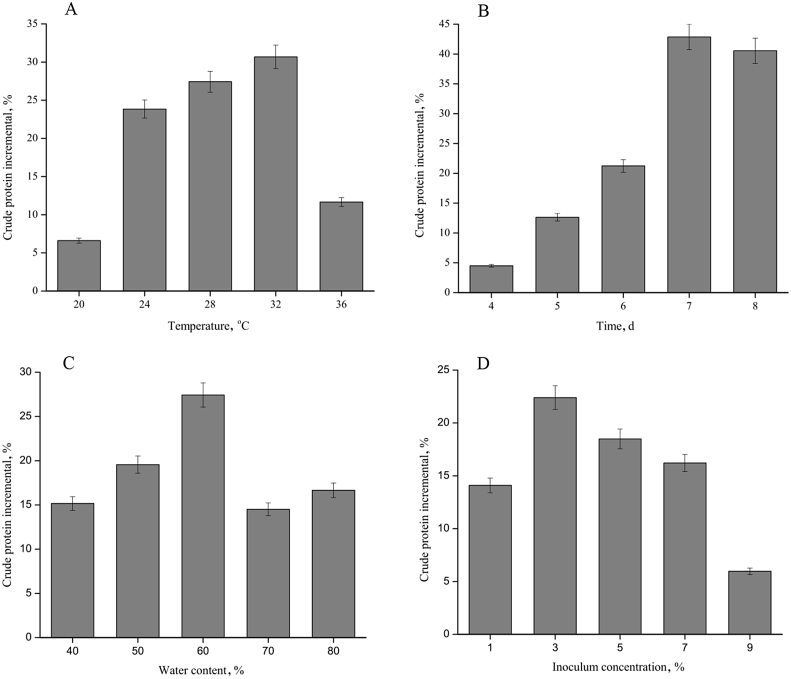

3.5. Optimization of fermentation conditions

The result of exploring the fermentation condition showed that the optimal condition for achieving the highest increase in the crude protein content after fermentation was as follows: temperature 32 °C, time 7 d, water content 60%, and inoculation amount 3%. The levels of orthogonal experimental variables were determined according to the aforementioned single factor experimental results. The 4 factors and 3 levels of orthogonal design are shown in Table 1. The results and range analysis are shown in Table 4. The analysis showed that the optimum fermentation condition was temperature 32 °C, time 144 h, water content 60%, and inoculation amount 3%. The primary and secondary order of single factors that affected the crude protein increment were inoculation amount, water content, temperature, and time (Fig. 7).

Table 4.

Orthogonal experiment design and analysis results1.

| Groups | Levels |

Crude protein increment, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, °C | B, d | C, % | D, % | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13.5 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 43.4 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 26.7 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 28.7 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 18.4 |

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 27.9 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 43.7 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 20.9 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 28.2 |

| K1 | 83.6 | 85.9 | 62.4 | 60.1 | |

| K2 | 75.1 | 82.7 | 100.3 | 114.9 | |

| K3 | 92.8 | 82.8 | 88.8 | 76.4 | |

| k1 | 27.9 | 28.6 | 20.8 | 20.0 | |

| k2 | 25.1 | 27.6 | 33.4 | 38.3 | |

| k3 | 30.9 | 27.6 | 29.6 | 25.5 | |

| R | 5.92 | 1.06 | 12.6 | 18.3 | |

A, temperature; B, time; C, water content; D, inoculum concentration; Ki, the sum of i in the current column, ki, the average of i in the current column. R, the difference between the maximum and minimum average values in the current column.

According to the K value, the optimum conditions were A3B1C2D2. According to the R value, the primary and secondary order of single factors that affected the crude protein increment was D > C > A > B.

Fig. 7.

Influence of fermentation parameters on crude protein increment by strain M-2. (A) influence of cultivation temperature, (B) influence of cultivation time (C) influence of initial substrate water content, (D) influence of initial inoculum concentration. Results are the average of 3 replicates, and the bars indicate the standard error of 3 replicates.

4. Discussion

Ruminants have a relatively stable microbial ecological balance system and contain rich microbial flora. Zhu et al. (2010) has shown that ruminants formed a tolerance mechanism to cyanogenic glycosides during long-term evolution. In addition, the content of rhodanese in ruminants was significantly higher than that in monogastric animals (Zhao and Wang, 2008). Our findings are consistent with the above studies. In this study, all of the highly productive β-glucosidase strains were isolated from the dung of cows fed flaxseed cake for a long time. This shows that β-glucosidase-producing strains in the intestine of these cows have a higher level of content than that of cows not fed flaxseed cake.

The same result was also found during in vitro fermentation. Before this study, we used dung from cows fed flaxseed cake to ferment flaxseed cake, and found that the removal rate of cyanogenic glycosides of cows fed long-term ferment flaxseed cake was higher than those not fed flaxseed cake. This also confirmed the above point that the intestinal microflora of cows are subjected to long-term domestication of flaxseed cake. In other words, it is likely that β-glucosidase producing strains are present in the gut. However, this study did not perform genomic analysis of the gut microbes of cows, so this conclusion needs further verification.

Based on these conjectures, we aimed to ferment flaxseed cake in vitro. In fact, we isolated 5 high yield strains of bacteria and fungi that produce β-glucosidase, and successfully screened the strain M-2 with a good fermentation performance. During the screening of fermentation strains, we found that the fermentation effects of M-1 and M-2 are better. It is very likely that bacteria have no advantage in solid fermentation systems. In addition, bacterial metabolism and reproduction require a more stringent nutritional ingredient ratio, and the composition of flaxseed cake is more complex and may not meet the growth requirements of bacteria (Zhai and Yang, 2014). Although X-1, X-3 and X-6 are capable of producing β-glucosidase, they cannot grow in large numbers and thus result in a low removal rate of cyanogenic glucosides. Cyanogenic glycosides are soluble in water. Therefore, even if the degrading bacteria are not added, about 70% of cyanogenic glycoside removal occurs after water invasion treatment for 6 d. Therefore, we also observed a decrease in cyanogenic glycosides in the control group.

Crude protein is one of the main nutritional indicators in feed nutrients, and it is also one of the important indicators for evaluating the nutritional value of feed. It is a general term for nitrogenous substances in feed, including pure protein and amides such as amino acids and urea. Therefore, the measurement of crude protein in feed occupies a very important position in the detection of feed (Fan, 2014). Based on this, we used the content of crude protein as a screening standard and M-2 as a fermentation strain to explore the optimal fermentation conditions. This means that flaxseed cake fermented by M-2 not only reduced the content of cyanogenic glycosides, but also increased its crude protein content. Dry matter loss occurs during the fermentation process, but there is no significant change before and after, while the increase in crude protein is significant. This shows that the increase in crude protein content may be due to that nitrogen-fixing bacteria play a major role in the fermentation process.

It has been reported that microbial fermentation of agricultural by-products containing toxic components has been progressing with the application of microorganisms, and the fermentation products can reach the standard of fodder (Vasconcellos et al., 2009). There are also reports that significant effects have been achieved by modern genetic engineering to explain the toxic components of agricultural products or agricultural by-products (Zhu et al., 2010, Wu, 2012). In comparison with the previous research achievements (Feng et al., 2003, Yamashita et al., 2007, Wu et al., 2012), the detoxification effect is even more pronounced, because our fermenting strains came from cattle fed the untreated flaxseed cake for 2 years. Since the microorganisms themselves are derived from the animal body, this ensures the safety of the non-toxic or low-toxicity feed obtained by the fermentation of this strain.

We screened strains with significant detoxification effect and high crude protein yield and explored the fermentation conditions. However, flaxseed cake contains more fat and crude fiber substances in addition to proteinaceous substances. Fat is a beneficial ingredient whereas crude fiber is an anti-nutritional ingredient for animal body. Whether or not the fat component is metabolized during the fermentation of the flaxseed cake with the microorganism, and how to use the microorganisms to degrade the crude fiber therein has become a problem to be considered. In addition, based on the high safety requirements of the feed industry, animal models are still used to evaluate safety before large-scale fermentation is explored using the methods utilized in this study.

5. Conclusion

This study isolated 5 β-glucosidase-producing strains from cow dung. The 5 strains were identified: X-1, C. freundii; X-3, P. rettgeri; X-6, P. vulgaris; M-1, G. candidum; and M-2, L. ramosa. Fermentation detoxification results showed that the strain M-2 had the best effect, and the optimum condition was inoculum size 3%, water content 60%, time 144 h, and temperature 32 °C. Under these condition, the removal rate of cyanogenic glucosides reached 89%, and crude protein increment reached 44%. This study provided a theoretical basis for removing cyanogenic glycosides and comprehensively utilizing flaxseed cake.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Jiangsu Science and Technology Major Project (BA2016036), Lanzhou Science and Technology Funds (2015-3-81) and Gansu Science and Technology Major Project (17ZD2FA009). The authors thank the Gaolan dairy farm and the College of Life Science and Technology for their assistance in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Archana N., Prajwal R., Joshi S.R. Diversity and biological activities of endophytic fungi of emblica officinalis, an ethnomedicinal plant of India. Mycobiology. 2012;40(1):8. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.1.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner D.J., Farmer J.J.I., Fanning G.R., Steigerwalt A.G., Klykken P., Wathen H.G. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness of proteus and providencia species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28(2):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cho K.H., Park J.E., Osaka T., Park S.G. The study of antimicrobial activity and preservative effects of nanosilver ingredient. Electrochim Acta. 2005;51(5):956–960. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Cai Y. 2001. Common bacterial system identification manual. [Google Scholar]

- Fan G.Z. Four key points in the determination of crude protein in feeds. Farming Feed. 2014;(4):39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Feng D., Shen Y., Chavez E.R. Effectiveness of different processing methods in reducing hydrogen cyanide content of flaxseed. J Sci Food Agric. 2003;83(8):836–841. [Google Scholar]

- Ganorkar P.M., Jain R.K. Flaxseed - a nutritional punch. Int Food Res J. 2013;20(2):519. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.S., Chen Q., Guo B.Q., Lv Z.C., Wang S.S. The development of the flax production in the Inner Mongolia Midwest. Agric Sci Tech Inner Mongolia. 2010;5:105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D., Kokić B., Brlek T., Čolović R., Vukmirović Đ., Lević J. Effect of microwave heating on content of cyanogenic glycosides in linseed. Ratarstvo I Povrtarstvo. 2012;49(1):63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lan W. Study on the technology of detoxification of rapeseed meal by acid solvent. J Chin Cereals Oils Assoc. 2012;11:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.L., Zhang Z., Wu M., Wu Y., Feng J.X. Isolation, screening, and identification of cellulolytic bacteria from natural reserves in the subtropical region of China and optimization of cellulase production by paenibacillus terrae ME27-1. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014(5):512497. doi: 10.1155/2014/512497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen P., Sørensen J. Multi-target and medium-independent fungal antagonism by hydrolytic enzymes in Paenibacillus polymyxa and Bacillus pumilus strains from barley rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22(3):183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hyunsu Park, Young-Don Park, Jaeho Cha. Optimization of glycosyl aesculin synthesis by thermotoga neapolitana β-glucosidase using response-surface methodology. J Life Sci. 2017;27(1):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez G., Fariña L., Barquet M., Boido E., Gaggero C., Dellacassa E. A quick screening method to identify β-glucosidase activity in native wine yeast strains: application of Esculin Glycerol Agar (EGA) medium. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27(1):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Polz M.F., Cavanaugh C.M. Bias in template-to-product ratios in multitemplate PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64(10):3724. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3724-3730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Zhang Y., He H., Zhu J., Chen G., Li W. Screening and identification of a fungal β-glucosidase and the enzymatic synthesis of gentiooligosaccharide. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;163(8):1012–1019. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-9105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R., Reggiani R. Variation in the content of cyanogenic glycosides in flaxseed meal from twenty-one varieties. Food Nutr Sci. 2014;5(15):1456–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava B. 2011. Experimental microbiology and instrumentation. [Google Scholar]

- Stock I., Wiedemann B. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Providencia stuartii, P. rettgeri, P. alcalifaciens and P. rustigianii strains. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47(7):629. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-7-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.Y. Research progress on application of flaxseed as feed. Plant Fiber Sci Chian. 2010;(1):23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Xu H. Research progress on flaxseed cyanogenetic glycoside. China Oils Fats. 2007;32:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sun R., Wang Y., Yang P.P. Status and prospect of citric acid fermentation. Chin Condiments. 2011;36(1):90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tao H.Q., Li X.Y., Yang J.H., Yang L. Universal primer PCR-SSCP analysis of 16Sr RNA gene characterization for rapid identification of bacteria. Med Res Mag. 2004;33(5):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos S.P., Cereda M.P., Cagnon J.R., Foglio M.A., Rodrigues R.A., Manfio G.P. In vitro degradation of linamarin by microorganisms isolated from cassava wastewater treatment lagoons. Braz J Microbiol. 2009;40(4):879. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220090004000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. Research progress of microbial fermentation of cottonseed meal. China Feed. 2007;18:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.B. Study on the effect of different assay methods on the determination of crude protein in feed. Feed Livest Husb New Feed. 2008;(12):41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.F. Zhongshan University; Guangzhou: 2012. Construction of engineered strains for efficient degradation of cyanidoside and study on fermentation of flaxseed. [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Li D., Wang L.J., Zhou Y.G., Brooks S.L., Chen X.D. Extrusion detoxification technique on flaxseed by uniform design optimization. Separ Purif Technol. 2008;61(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.F., Xu X.M., Huang S.H., Deng M.C., Feng A.J., Peng J. An efficient fermentation method for the degradation of cyanogenic glycosides in flaxseed. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Analy Contr Expos Risk Assess. 2012;29(7):1085. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2012.680202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F. Anhui Agricultural university; Hefei: 2005. Studies on biological characteristic of mold fungus and control of moulding of tobacco in storage. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T., Sano T., Hashimoto T., Kanazawa K. Development of a method to remove cyanogen glycosides from flaxseed meal. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2007;42:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.Z., Wang Q., Shao-Xiong W.U., Zhang X.H., Fang X.U., Zhang L.J. Orthogonal array optimization of wine fermentation from purple sweet potato residue after pigment extraction and sensory evaluation by fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model. J Food Sci. 2011;32(6):131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai S., Yang L. China Feed; 2014. Detoxification technology of flaxseed meal and its application in animal feed. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.L., Wang S.Z. Effects of rumen microorganisms on feed poison in ruminants. Chin Animal Health. 2008;6:64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Discussion on several methods of determining crude protein content of oil cookies. China Oils Fats. 2002;27:90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D.W., Liu Z.P., Cai G.L., Cao Y., Wang X.G., Lu J. Screening of highly degradable gossypol species and study on fermentation and detoxification of cottonseed meal. Chin oil. 2010;35(2):24–28. [Google Scholar]