Abstract

Objectives

To describe reasons for unmet need for mental health care among blacks, identify factors associated with causes of unmet need, examine racism as a context of unmet need, and construct ways to improve service use.

Data Sources

Data from the 2011‐2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health were pooled to create an analytic sample of black adults with unmet mental health need (N = 1237). Qualitative data came from focus groups (N = 30) recruited through purposive sampling.

Study Design

Using sequential mixed methods, reasons for unmet need were regressed on sociodemographic, economic, and health characteristics of respondents. Findings were further explored in focus groups.

Principal Findings

Higher education was associated with greater odds of reporting stigma and minimization of symptoms as reasons for unmet need. The fear of discrimination based on race and on mental illness was exacerbated among college‐educated blacks. Racism causes mistrust in mental health service systems. Participants expressed the importance of anti‐racism education and community‐driven practice in reducing unmet need.

Conclusion

Mental health systems should confront racism and engage the historical and contemporary racial contexts within which black people experience mental health problems. Critical self‐reflection at the individual level and racial equity analysis at the organizational level are critical.

Keywords: mental health disparities, mental health services, racism and mental health, unmet need

1. INTRODUCTION

Although blacks have similar or lower rates of common mental disorders than whites, mental disorders are more severe, persistent, and disabling among blacks.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Blacks are also less likely to utilize psychiatric services, and if they receive care, it is usually of lower quality than care provided to whites.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Consequently, unmet need for mental health care is greater among blacks than whites.

Documenting racial inequities in mental health status, access to services, utilization, and quality of care requires comparing these outcomes between marginalized and dominant racial groups. Therefore, most of the research examining inequities employs race comparative approaches. However, identifying and addressing mechanisms that underlie inequities require more in‐depth analyses of the contexts in which people who belong to racial minority groups experience poor health outcomes.11 This study describes reasons for unmet need for mental health care specifically among blacks, identifies factors that are associated with causes of unmet need, examines the racial context of unmet need, and constructs ways to improve service use.

Given that racism is implicated in inadequate access to and utilization of health services in general,12 it is necessary to explore how racism might limit the use of mental health care thereby increasing unmet need. Research that assesses the relationship between racism and a range of mental health outcomes has focused on pathways such as discrimination that limit access to resources or directly cause chronic stress, and on the internalization of racist stereotypes which induce emotional and physiological responses that take a toll on mental health.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 However, little is known about how racism inhibits utilization of mental health services, thereby creating unmet need among blacks with mental disorders.

To fill this gap, the current study investigates how racism is implicated in the reasons why blacks with mental health problems might neither seek nor receive the services they need. Specific aims are as follows: (a) To characterize unmet need by identifying characteristics of blacks that are associated with reporting different reasons for perceived unmet need for mental health care; (b) To examine the degree to which reasons for unmet need are a result of racism; and (c) To construct anti‐racism approaches to reducing unmet need.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This study uses an explanatory sequential mixed methods design, employing a second methodology to complement and explain findings from the first.18 Quantitative analysis of national survey data addresses aim 1: Identifying characteristics of blacks that are associated with reasons for perceived unmet need for mental health care. Qualitative data elaborate on the racial context of the quantitative results (aim 2) and identify ways of reducing unmet need (aim 3).

2.2. Data sources and analyses

2.2.1. Quantitative data

Quantitative data came from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The analytic sample consisted of black adults in the 2011‐2015 data who reported unmet need for mental health care (n = 1237). In the NSDUH, unmet need was established by asking respondents whether at any time in the past 12 months, they perceived a need for mental health treatment or counseling but did not receive these services.

Respondents with unmet need were further asked to specify reasons for not receiving care. These reasons were grouped into five main categories: (a) Cost (if they reported at least one of the following: could not afford costs, health insurance does not cover any mental health treatment/counseling, or health insurance does not pay enough for mental health treatment/counseling); (b) Stigma (at least one of the following: might cause neighbors/community to have a negative opinion, might have negative effect on job, did not want others to find out, concerned about confidentiality, or concerned about being committed/having to take medications); (c) Minimization (did not feel the need for treatment at the time or thought they could handle the problem without treatment); (d) Low perceived effectiveness of treatment (didn't think services would help); and (e) Accessibility barriers (at least one of the following was reported: no transportation, location was inconvenient, did not know where to go for services, or did not have time).

Quantitative analysis

Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to identify sociodemographic, health status, and health insurance characteristics that were associated with reporting each of the five reasons for unmet need (cost, stigma, minimization, low perceived effectiveness of treatment, and accessibility barriers). Pooled weights were applied to ensure that the analytic sample was representative of the national average for 2011‐2015. Parameter estimates and standard errors were also adjusted for the multistage sampling design of the NSDUH using Taylor series linearization methods. STATA 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used.

2.2.2. Qualitative data

Qualitative data were obtained from four focus groups. Two focus groups were held in the Midwest and two on the East Coast. Research ads were placed in clinics, community centers, and local businesses and via listserves to Black mental health providers in the two main cities from which participants were recruited. All focus group participants (n = 30) identified as Black and were recruited through maximum variation purposive sampling to ensure some variation in gender, age, education, and relationship with the mental health system. Two focus groups (one in the Midwest and one in the East Coast) included mental health providers. The Midwest focus group included six providers (50 percent female; age range 36‐61); the East Coast focus group included seven providers (three men, four women; age range 28‐68). Two other focus groups were conducted with community members interested in mental health. The Midwest focus group included nine community members (six men, three women; age range 22‐45). None of the participants in this group had a college degree. The second focus group of community members was on the East Coast with eight participants (four men, four women; age range 18‐54). Six of the eight participants in this group held a college degree. The study was approved by the university's institutional review board.

Qualitative analysis

Collective conversations provided contexts for understanding perspectives of providers and community members with similar racial identity. The discussions in each focus group were guided by four main questions that provided a range of experiences and perspectives about addressing unmet need in a racialized context: (a) Can you talk about a time when you or another black person you know needed professional help for a mental or emotional problem but ended up not receiving the help needed? (b) Some people say that finances prevent them from seeking care. Some cite stigma. Others think that the issue will go away on its own, or feel that it is not a big deal, or that going to a professional will not help. Some just don't know where to go, the location is inconvenient, they lack transportation, or don't have time. Has there been a time when any of these reasons prevented you or someone you know from seeking help? (c) Does racism affect your decision and ability to seek help for a mental health problem? (d) How can the mental health system better address the needs of black people? These questions elicited discussions about the racial context of unmet need, legitimized the narratives of people experiencing inequities, and privileged their perspectives about how to confront racism and to better address their mental health needs. Saturation for each question was achieved when all the participants in each focus group had shared an experience or perspective similar with that of someone else, or when at least half of the participants were repeating their own unique perspective.

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using both inductive and deductive approaches to coding. Deductively, the preliminary organizing framework for coding was based on findings from the quantitative analysis and the focus group questions. Two coders reviewed the focus group transcripts and identified portions associated with each reason for perceived unmet need and with racism. Inductively, emergent categories (neither explicit in the quantitative findings nor the focus group questions) were identified from the data and coded. Coding was done separately, after which the coders came together to compare codes. Discrepancies were resolved by merging similar codes or excluding redundant ones. Finally, all similar codes were further grouped into overarching themes that reflect the totality of experiences and opinions discussed in the focus groups. The abstraction of themes was performed independently. An initial 90 percent agreement was reached. The coders investigated the 10 percent variability and re‐conducted the abstraction of themes until complete agreement was achieved.

3. RESULTS

In the full pooled data (2011‐2015), 25 260 blacks needed mental health services. 10.2 percent (weighted) reported that they did not get the treatment or counseling they needed (unmet need), compared to only 5.1 percent of the general population with unmet need. Sample characteristics of African Americans with unmet need (N = 1237) are shown on Table 1. The sample was disproportionately female, one in five had a college education, two‐thirds lived in large metropolitan areas, one‐half were employed, and a quarter were uninsured.

Table 1.

Characteristics of non‐Latino Blacks/African Americans who reported unmet need for mental health care in the 2011‐2015 NSDUH (N = 1237)

| % (Weighted) | N (Unweighted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| 18‐25 years old | 21.65 | 625 |

| 26‐34 | 22.23 | 226 |

| 35‐49 | 3.16 | 264 |

| 50‐64 | 19.43 | 105 |

| 65 and older | 5.10 | 17 |

| Male | 28.26 | 352 |

| Single/never married | 53.70 | 881 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 23.54 | 189 |

| Married | 20.76 | 167 |

| Less than High School | 20.34 | 278 |

| Completed High School | 30.77 | 401 |

| Some college | 28.86 | 368 |

| College degree and higher | 20.02 | 190 |

| Large metro | 66.63 | 771 |

| Small metro | 22.64 | 335 |

| Non‐metro | 10.73 | 131 |

| 100% of FPL | 43.21 | 574 |

| 100%‐199% | 22.90 | 285 |

| 200% + FPL | 33.89 | 378 |

| Unemployed | 36.15 | 390 |

| Not in labor force | 13.42 | 213 |

| Employed | 50.43 | 634 |

| Health status | ||

| Excellent/Very good/Good Health | 67.43 | 924 |

| Substance abuse or dependence | 7.63 | 134 |

| Mean K6 scores (standard error) | 10.87 (0.26) | 1237 |

| Mean WHODAS (standard error) | 11.35 (0.30) | 1237 |

| Health Insurance | ||

| Uninsured | 24.68 | 314 |

| Public | 39.67 | 483 |

| Private | 35.65 | 436 |

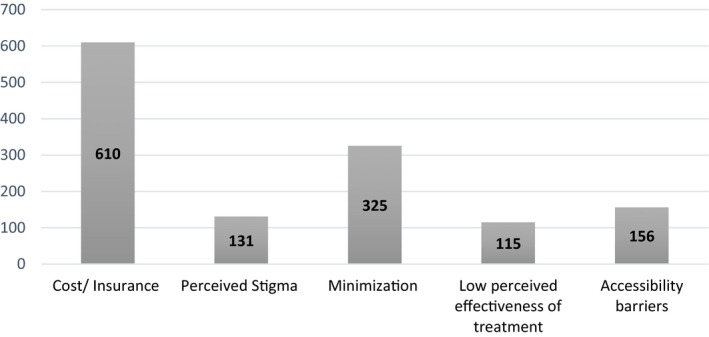

Figure 1 shows the frequency of each of the reasons for unmet need in the analytic sample—only those who reported unmet need.

Figure 1.

Frequency* of reasons for perceived unmet need [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]*Respondents could mention more than one reason for unmet need, and therefore, the sum of the frequencies is greater than the analytic sample size.

3.1. Factors associated with reasons for unmet need

Characteristics of respondents that are associated with each reason for perceived unmet need are shown on Table 2. Compared to 18‐25 year olds, black adults age 35‐49 and 50‐64 had higher odds of reporting cost as a reason for not seeking care (OR = 1.52, CI = 1.03‐2.25, and OR = 3.33, CI = 2.10‐5.31, respectively). Married persons were less likely than their single counterparts to report cost (OR = 0.59, CI = 0.38‐0.94). Not surprisingly, publicly and privately insured persons were significantly less likely than uninsured persons to report cost as a reason for unmet need (OR = 0.21, CI = 0.15‐0.31, and OR = 0.47, CI = 0.32‐0.70, respectively).

Table 2.

Logistic regressions of reasonsa for unmet need on sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and insurance

| Cost/Insurance | Stigma | Minimization | Low effectiveness | Accessibility barriers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (18‐25) | |||||

| 26‐34 | 1.20 (0.83‐1.74) | 0.39* (0.17‐0.93) | 1.19 (0.78‐1.82) | 0.92 (0.45‐1.86) | 0.78 (0.29‐2.03) |

| 35‐49 | 1.52* (1.03‐2.25) | 0.21** (0.07‐0.58) | 0.82 (0.51‐1.34) | 0.49 (0.19‐1.23) | 0.26** (0.07‐0.98) |

| 50‐64 | 3.33*** (2.10‐5.31) | 0.10** (0.02‐0.57) | 0.20** (0.07‐0.55) | 0.48 (0.12‐1.87) | 1.08 (0.28‐4.09) |

| 65 and older | 2.45 (0.78‐4.63) | 1.02 (0.94‐1.21) | 0.92 (067‐1.33) | 2.39 (0.39‐9.44) | 1.11 (0.98‐1.28) |

| Men (ref: women) | 1.05 (0.78‐1.41) | 0.51 (0.22‐1.18) | 0.55*** (0.36‐0.84) | 1.23 (0.68‐2.25) | 0.55 (0.21‐1.42) |

| Marital status (ref: single) | |||||

| Sep/Div./Wid. | 0.68 (0.43‐1.06) | 3.30** (1.30‐5.38) | 1.09 (0.63‐1.91) | 1.2 (0.47‐3.04) | 2.45** (1.85‐6.03) |

| Married | 0.59* (0.38‐0.94) | 1.24 (0.43‐3.59) | 1.27 (0.75‐2.17) | 0.46 (0.15‐1.43) | 0.63 (0.12‐2.18) |

| Education (ref: <H.S.) | |||||

| Completed H.S. | 0.97 (0.67‐1.40) | 0.44 (0.34‐2.35) | 1.6* (1.09‐2.55) | 1.31 (0.54‐3.14) | 0.47 (0.19‐1.14) |

| Some college | 1.16 (0.77‐1.74) | 0.77 (0.60‐3.13) | 1.42* (1.02‐2.45) | 2.91** (1.20‐6.05) | 0.79 (0.31‐2.02) |

| College degree and higher | 1.07 (0.64‐1.78) | 1.93* (1.13‐5.34) | 2.14** (1.13‐3.98) | 3.79** (1.35‐9.64) | 0.35* (0.09‐0.96) |

| Residence (ref: big metro) | |||||

| Small metro | 1.04 (0.76‐1.43) | 0.41 (0.55‐2.31) | 0.93 (0.63‐1.38) | 1.13 (0.59‐2.16) | 1.03 (0.46‐2.31) |

| Non‐metro | 1.11 (0.71‐1.75) | 0.75 (0.51‐4.01) | 0.87 (0.47‐1.60) | 2.19* (1.15‐5.01) | 1.30* (0.44‐3.67) |

| Poverty (ref: <100% of FPL) | |||||

| 100%‐199% | 1.22 (0.86‐1.75) | 0.21 (0.18‐1.16) | 1.2 (0.77‐1.86) | 1.49 (0.73‐3.06) | 0.66 (0.35‐2.10) |

| 200% + FPL | 0.89 (0.60‐1.31) | 0.42 (0.43‐2.30) | 1.1 (0.68‐1.79) | 1.37 (0.64‐2.92) | 0.49 (0.14‐1.75) |

| Work (ref: unemployed) | |||||

| Not in labor force | 1.72 (1.13‐2.61) | 0.40 (0.27‐2.16) | 0.85 (0.49‐1.45) | 0.82 (0.36‐1.86) | 0.59 (0.21‐1.65) |

| Employed | 1.34 (0.94‐1.91) | 0.40 (0.48‐2.23) | 1.02 (0.66‐1.58) | 0.55 (0.26‐1.13) | 0.37** (0.15‐0.90) |

| Excellent/V. good/Good health | 0.91 (0.65‐1.27) | 0.41** (0.19‐0.85) | 1.16 (0.74‐1.78) | 1.29 (0.61‐2.71) | 1.34 (0.58‐3.06) |

| Substance abuse or dependence | 0.83 (0.55‐1.28) | 1.16 (0.48‐2.75) | 1.06 (0.63‐1.78) | 2.5** (1.31‐4.81) | 1.87** (1.23‐4.66) |

| K6 scores | 1.03 (0.98‐1.16) | 0.96 (0.90‐1.07) | 0.94 (0.90‐1.88) | 1.03 (0.98‐1.10) | 1.02 (0.95‐1.10) |

| Mean WHODAS | 0.99 (0.91‐1.19) | 1.04 (0.99‐1.10) | 1.02 (0.99‐1.09) | 1.01 (0.96‐1.10) | 1.05 (0.99‐1.11) |

| Insurance (ref: uninsured) | |||||

| Public | 0.21*** (0.15‐0.31) | 2.45 (0.93‐5.45) | 2.32** (1.42‐3.79) | 1.73 (0.77‐3.88) | 1.16 (0.47‐2.84) |

| Private | 0.47*** (0.32‐0.70) | 2.3** (1.09‐6.55) | 2.14* (1.28‐3.58) | 2.13 (0.95‐4.77) | 1.24 (0.41‐3.78) |

aBecause reasons are not mutually exclusive, the odds of reporting each reason for unmet need are in comparison to odds of not reporting that reason at all. The estimates are not comparable across reasons.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Among respondents who were 64 years and younger, older age was associated with lower odds of reporting stigma. Odds of reporting stigma were higher among persons with a college degree compared to those who had less than a high school education (OR = 1.93, CI = 1.13‐5.34). Respondents with good, very good, or excellent self‐rated health had lower odds of reporting stigma than their peers who rated their general health as fair or poor (OR = 0.41, CI = 0.19‐0.85). Factors associated with minimization included age: lower odds among those ages 50‐64 compared to 18‐25 year olds (OR = 0.20, CI = 0.07‐0.55), and gender: men were less likely than women to think that they could handle the problem without treatment or to not feel the need for treatment at the time (OR = 0.55, CI = 0.36‐0.84). Higher education was also associated with greater odds of minimization, and persons who were insured (public or private insurance) had higher odds of reporting minimization than their peers who were uninsured.

Persons with at least some college education were more likely to report unmet need because of low perceived effectiveness of treatment than those who did not attend college. Compared to respondents living in large metropolitan areas, those living in non‐metro areas had greater odds of skipping care because they thought treatment or counseling would not help (OR = 2.19, CI = 1.15‐5.01). Blacks who met criteria for substance abuse or dependence were more likely to report low perceived effectiveness of treatment than peers without substance use problems (OR = 2.5, CI = 1.31‐4.81). People in non‐metro areas had higher odds of reporting accessibility barriers than those in large metro areas (OR = 1.30, CI = 0.44‐3.67). Employed persons were less likely than unemployed persons to report barriers related to access as reasons for unmet need (OR = 0.37, CI = 0.15‐0.90). Blacks who met criteria for substance abuse or dependence had greater odds of reporting accessibility barriers than their peers without substance use problems (OR = 1.87, CI = 1.23‐4.66).

3.2. Racism as the context of unmet need

The goals of the focus groups were to explore the racialized context of reasons for unmet need and to find solutions. Four inter‐related themes characterized respondents’ perceptions of racism as central to unmet need.

3.2.1. Interconnected systems of oppression

John, a focus group participant who had held minimum wage jobs for over 20 years talked about how the oppression that he faced in other institutions affected his expectation of how he would be treated in mental health settings.

They treat us bad in school, at work and on the streets. If I'm not dying I'm not going to the hospital. They'll treat us bad there too. You want them to give you medications for mental health? That stuff can mess with you real good. My pop says they'll come for you at your house, so why do you have to go to them to make it easier. John, lay resident

Having already experienced discrimination outside of the health system, John believed that by not seeking mental health care, he was reducing his exposure to additional structures that can serve as tools for racial oppression. An indicator of lack of access in the NSDUH such as not knowing where to go for treatment was described as a racialized barrier to care because it was perceived to be linked to racially unequal access to information that matters for health.

I wouldn't know where to go. They come here and make us fill all these questionnaires but we don't know what happens after. They don't say go to this place or that place if you have an emotional problem. Maybe they don't care. Truth is we are still enslaved, laboring for them. Alvin, lay resident

Other issues around interconnected systems of oppression discussed in the focus groups included homelessness and housing insecurity. Being able to receive treatment under such circumstances was challenging. Cost barriers were also mentioned in the context of hierarchy of needs for black families.

Yes I have insurance and a $25 co‐pay with each visit. But it is still $25. What if they give me pills? What if I have to go to therapy every week? I just thank God that I don't need to go. My first priority is a making sure we pay our rent, then food. My family cannot be another black family depending on welfare. Faye, lay resident

3.2.2. Double discrimination

Participants talked about how mental illnesses are stigmatized. They also talked about how blackness is devalued, and how black people experience discrimination in everyday life. The fear of experiencing double discrimination—from mental illness and from being black—was a significant barrier to care.

First off, they see a black person they think angry, lazy, complaining, and stupid. Then black person says “yeah, I also have bipolar, they'll add crazy, unfit, dangerous, and incompetent to the list. I know it's stigma but who wants that? Ben, lay resident

White person with bipolar and black person with bipolar, black person with bipolar is worst off 100 percent of the time. Clarissa, clinical social worker

Discrimination based on mental illness and on race was even more exacerbated among black women.

I agree with others but want to add that it's difficult being a black woman in today's world, carrying the weight of the world on your shoulders, putting up with all the B.S. out in the world while providing and protecting your family and giving the gentleness to those you love. I just keep my business in my house. We don't have the luxury to sit on the therapy chair. Michelle, lay resident

3.2.3. Institutional mistrust

Respondents discussed how black people have gone into the mental health system to get help but have lost things that are important to them such as their children, jobs, and their sense of control:

I didn't need no doctor putting me in an institution. You know that's one way they put us away. Then they place our children in the [foster care] system. Phyllis, lay resident

I am an addict. I am well capable of handling things and I have done it for years now. But I could not keep up. They said they will help. What if they just want me to depend on them [mental health institutions] forever? I went. Come to find out, I could've trust my gut. It was another establishment telling me I'm not good enough. I couldn't go to group if I was high. I missed group three times then they didn't clear me for work. I didn't work, the problem got worse. Mike, lay resident

Focus group participants sometimes felt that they were the subjects of an experiment or believed that they were not seen as people but as a collection of symptoms or a condition that needed to be treated.

My daddy said one thing about history is that it repeats itself. One time, my uncle was experimented on from a doctor who gave him medicine upon medicine to see whether the different medicines will work. And my family didn't know what to look for. He became paralyzed. The county hospital said the other doctor was treating him for the wrong thing. They will experiment with your health. You think they care if another one of us lives or dies? Rose, lay resident

3.2.4. Racial micro‐aggressions

Participants reported that their experiences of poor treatment impacted their decisions about whether to continue to seek treatment.

When a doctor walks in through the door, I know in like 30 seconds if they respect me or not. Some just refuse eye contact. But this is like normal health doctor not mental health. I'm sure mental health doctors are the same. I won't go back to a doctor who does not respect me. Mason, lay resident

Mason, like other male participants, felt invisible in health care settings where he was vulnerable. Black men in focus groups discussed this invisibility in contrast to the hypervisibility they experience on the streets. They also highlighted how the mental health system is filled with racist assumptions and expectations about the experiences of black people.

Instead of just asking me, she said ‘it must have been hard growing up without your dad’ but I grew up with my dad always being there. I did not return for my next appointment. Tanya, lay resident

In the emergency room, my brother heard the nurses saying that my other brother was not having psychosis from schizophrenia but that he was high on drugs. They wanted him to do a drug test first. Sandra, clinical psychologist

Sometimes, clinicians unconsciously suggested that black patients should assimilate to a dominant culture that characterizes counseling, or that black patients should only see black providers.

My colleague asked me if she should recommend me to her client because the client is loud sometimes and she doesn't know if it is a cultural thing. The client is black and I'm black. I guess she can't be bothered by anything different or anything that makes her uncomfortable. Christie, psychiatrist

3.3. Anti‐racism approaches to reducing unmet need

Two main themes were abstracted as anti‐racism strategies for reducing unmet need: anti‐racism education and centering the margins.

3.3.1. Anti‐racism education

Participants suggested that educating providers about race, privilege and oppression, and being conscious of how these issues manifest in mental health systems might make a difference.

I think in this day and age, most of us are taught to think about how our own belief systems affect our patients. But I wonder what a difference it will make if we specifically think about how white privilege affects the way we provide care. If we can identify our racial position whether as oppressor or the oppressed when it comes to values and power, we can be more inclusive. Ron, psychiatrist

If the Board of Directors and doctors are all white, they should be asking themselves why. If I don't see people who look like me there, or maybe they are cleaning, or are the ones doing security, then I think they are not making an effort. It's like they are not even trying. At that point, I already know the kind of place I am dealing with because you can't tell me that not a single black person qualified to be a professional there. You can't tell me that you don't notice that all the professionals are White. Caleb, lay resident

3.3.2. Center the margins

Narratives from the focus groups emphasized the need for mental health service systems to seek and take seriously the perspectives of people who experience unmet need.

If they felt we are equal, we too would be at the table when the decisions about us are made. They will recognize our voices, we would be recognized. Steve, lay resident

If you want to help me with re‐entry then listen to me. I am the one who was incarcerated for seven years. I am the one who came back from prison and has difficulties integrating into my community. King, lay resident

One thing I don't like is that they can use the treatment approaches developed from research on white people on black people‐ its mainstream, but if it is the other way around, it is ethnic or cultural. Janelle, counseling psychologist

4. DISCUSSION

Sociodemographic, economic, health status, and health insurance characteristics are associated with reasons why blacks report unmet need for mental health care. For example, younger black adults ages 18‐25 reported stigma which is consistent with previous work that found stigma to be a significant barrier to professional mental health services among black college students.19 A few of the results from the current study were expected: respondents who had health insurance were less likely to mention cost as a reason for unmet need, people residing in non‐metropolitan areas had higher odds of reporting accessibility barriers such as the inconvenient location of mental health providers compared to their peers in large urban areas. However, college education and employment were associated with increased odds of stigma, and the more education a person had, the greater their odds of reporting minimization and low perceived treatment effectiveness as reasons for unmet need. This was surprising.

If we rely on the quantitative findings alone, then mental health literacy and stigma campaigns might make great interventions to address stigma and minimization of symptoms as causes of unmet mental health needs among blacks who are employed or who have a college education. But participant narratives highlighting double discrimination contextualized stigma and minimization of symptoms as reasons for unmet need for mental health care among blacks reported in the NSDUH. The qualitative analysis demonstrated how racism is implicated in why blacks report these reasons for not receiving treatment for mental health problems. Specifically, the fear of double discrimination may be exacerbated among blacks in middle class positions where they work, compete, and are evaluated side‐by‐side whites. Because racial discrimination might increase with upward class mobility,20 the combination of discrimination based on race and on mental illness hinders treatment‐seeking.21 As a result, addressing stigma and not racism is unlikely to eliminate racial inequities in unmet need.

In the same way, simply focusing on minimization of symptoms among blacks would miss the need to confront broader contextual reasons such as the fear of oppression in mental health settings, exposure to racial micro‐aggressions, and mistrust in mental health systems that might cause avoidance of care. In the quantitative analysis, low perceived effectiveness of treatment was a significant reason for unmet need among persons who met criteria for substance abuse or dependence. But Mike's account in the focus group suggested that it could be more about mistrust in the ability of mental health institutions to help black people with substance use problems regain control of their lives than it is about the effectiveness of treatment in general. Indeed, mental health service systems are known to misconstrue and criminalize the behaviors of black communities, sometimes leading to involuntary hospitalization, involvement with the criminal justice system, or loss of benefits including employment.22, 23, 24

African Americans who lived in non‐metro areas were likely to report accessibility barriers such as lack of transportation and not knowing where to go to for care. They were also more likely to think that mental health treatment will not work. Because accessibility barriers prevent people from seeking care, they also limit opportunities to experience positive outcomes of care which might then strengthen perceptions about the effectiveness of treatment. Focusing upstream by addressing barriers in access to mental health services that are linked to racially inequitable distribution of resources is important for reducing unmet need among blacks.25, 26, 27

This study specifically focused on finding strategies for reducing unmet need because documenting inequities is not enough. The findings are consistent with calls for anti‐racism and critical race theory education in medical, public, and allied health schools.28, 29 Take medical education for example. Curriculum reports from the Association of American Medical Colleges show that the curriculum is highly standardized with a broad range of requirements including social determinants of health. While some medical schools have courses on racial disparities in health, critical race theory to help contextualize racial health disparities is not a requirement. In fact, in most medical school curricula, race is framed as biological or as a biological risk factor, implying that racial disparities in health are innate and can be explained without implicating racism.30, 31, 32, 33 This fosters pathologizing race rather than racism, whereas racism is the risk factor. Naming racism in medical education, health services research and policy, and how it is distinct from race as a category can advance efforts to reduce racial health inequities.34, 35, 36 Anti‐racism education can provide the tools needed to understand racial oppression, its connection to racial health inequities, and to move beyond frameworks that separate unmet need for mental health among blacks from historical and contemporary forms of racism.

Centering the margins is also important. Black people are experts of their own experiences. The narratives of participants underscored how historical and contemporary mental health delivery systems have been shaped by practices that normalize the white experience, often ignoring or relegating the experiences of blacks. Centering the margins requires privileging the perspectives and experiences of people living at the margins or those who have historically been neglected. This approach has the potential to increase engagement with care.37

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of a few caveats. First, populations with high mental health needs are not represented in the survey and in the focus groups. This includes people who are homeless or incarcerated. Stratifying the focus groups by individual mental health need might have been relevant given that perceptions of racism as central to unmet need might vary based on these factors. Second, focus group participants might be distinct from the general population of blacks in ways that might shape the mechanisms linking racism to unmet need. Third, racism is only one structure that affects unmet need for mental health care among blacks. There are other statuses and structures such as gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, education, socioeconomic position, and disability status that are linked to unmet need. How racism intersects with these structures and statuses was not rigorously explored.

4.1. Implications

Policies and programs can reduce unmet need for mental health care among blacks. For example, since cost is still a significant barrier to care and insurance is associated with lower likelihood of facing cost barriers, reducing uninsurance rates among blacks will reduce a proportion of unmet need. Similarly, there might be benefits to stigma reduction messages, programs that emphasize emotional health, and that integrate mental health with primary care and physical health services. These might reduce structural and informational barriers to mental health care as well as stigma.

Most importantly, unmet need for mental health care does not occur in vacuum and is not color‐blind. If racism shapes the lives of people of color, then racism also shapes whether they have unmet need for mental health care. Of course, other factors also cause unmet need among African Americans as they do for whites and other racial groups. Examples include insurance status and plans, geographic location, and mental health literacy.38, 39, 40, 41 However, anti‐black racism further exacerbates these issues for blacks. Acknowledging that racial inequities in unmet need for mental health care exists within a context where black people experienced significant historical trauma, yet were deprived of access to resources to ameliorate this trauma is important. To eliminate inequities, we have to address racism and the mistrust it has caused in mental health care systems.42 Organizing and delivering mental health services in ways that engage the racial context within which blacks experience mental health problems is necessary. This should include requiring anti‐racism and critical race theory education as part of the professional training of clinicians, researchers, policy makers, and administrators. Such an endeavor will foster critical self‐reflection, and racial equity analysis in research, policy, and practice at organizational and structural levels. Finally, centering the margins by doing more community‐driven health services and health policy research that is relevant to the experiences of marginalized groups, especially those experiencing poor mental health outcomes, might reduce unmet need.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was funded by the Franz/Class of ‘68 Pre Tenure Fellowship, Lehigh University. Special thanks to David Tomlinson and Hasshan Batts, D.HSc., MSW for facilitating community engagement, and Adama Shaw and Daniela Fraticelli for providing research assistance.

Alang SM. Mental health care among blacks in America: Confronting racism and constructing solutions. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:346–355. 10.1111/1475-6773.13115

REFERENCES

- 1. Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola‐Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychol Med. 2005;35(03):317‐327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12‐month DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL. Ethnicity/race and the diagnosis of depression and use of antidepressants by adults in the United States. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(2):106‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strakowski SM, Flaum M, Amador X, et al. Racial differences in the diagnosis of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 1996;21(2):117‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non‐Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alegría M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;59(11):1264‐1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cook BL, Zuvekas SH, Carson N, Wayne GF, Vesper A, McGuire TG. Assessing racial/ethnic disparities in treatment across episodes of mental health care. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):206‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jimenez DE, Cook B, Bartels SJ, Alegría M. Disparities in mental health service use of racial and ethnic minority elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):18‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roll JM, Kennedy J, Tran M, Howell D. Disparities in unmet need for mental health services in the United States, 1997‐2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(1):80‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027‐2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bediako SM, Griffith DM. Eliminating racial/ethnic health disparities: reconsidering comparative approaches. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2008;2(1):49‐62. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, Carter RT. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: a meta‐analytic review. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: the moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self‐esteem. J Couns Psychol. 1999;46(3):395‐407. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. J Black Psychol. 1996;22(2):144‐168. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sellers RM, Copeland‐Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis R. Racial identity matters: the relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16(2):187‐216. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933‐939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masuda A, Anderson PL, Edmonds J. Help‐seeking attitudes, mental health stigma, and self‐concealment among African American college students. J Black Stud. 2012;43(7):773‐786. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bowser BP. The Black Middle Class: Social Mobility–And Vulnerability. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gary FA. Stigma: barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(10):979‐999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corneau S, Stergiopoulos V. More than being against it: anti‐racism and anti‐oppression in mental health services. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012;49(2):261‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernando S. Institutional Racism in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology: Race Matters in Mental Health. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patel K, Heginbotham C. Institutional racism in mental health services does not imply racism in individual psychiatrists: commentary on… Institutional racism in psychiatry. Psychiatrist. 2007;31(10):367‐368. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alang SM. Sociodemographic disparities associated with perceived causes of unmet need for mental health care. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(4):293‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cook BL, Zuvekas SH, Chen J, Progovac A, Lincoln AK. Assessing the individual, neighborhood, and policy predictors of disparities in mental health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(4):404‐430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris KM, Edlund MJ, Larson S. Racial and ethnic differences in the mental health problems and use of mental health care. Med Care. 2005;43(8):775‐784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S30‐S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113‐2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bolnick DA. Combating racial health disparities through medical education: the need for anthropological and genetic perspectives in medical training. Hum Biol. 2015;87(4):361‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braun L. Theorizing race and racism: preliminary reflections on the medical curriculum. Am J Law Med. 2017;43(2–3):239‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martinez IL, Artze‐Vega I, Wells AL, Mora JC, Gillis M. Twelve tips for teaching social determinants of health in medicine. Med Teach. 2015;37(7):647‐652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsai J, Ucik L, Baldwin N, Hasslinger C, George P. Race matters? Examining and rethinking race portrayal in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):916‐920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feagin J. Systemic racism and “race” categorization in US medical research and practice. Am J Bioeth. 2017;17(9):54‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390‐1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hardeman RR, Burgess D, Murphy K, et al. Developing a medical school curriculum on racism: multidisciplinary, multiracial conversations informed by Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP). Ethn Dis. 2018;28(Supp 1):271‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Padgett DK, Henwood B, Abrams C, Davis A. Engagement and retention in services among formerly homeless adults with co‐occurring mental illness and substance abuse: voices from the margins. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(3):226‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bonabi H, Muller M, Ajdacic‐Gross V, et al. Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: a longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(4):321‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care, by insurance status, 1999‐2010. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1723‐1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stewart H, Jameson JP, Curtin L. The relationship between stigma and self‐reported willingness to use mental health services among rural and urban older adults. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(2):141‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Druss BG. Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):578‐584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gómez JM. Microaggressions and the enduring mental health disparity: black Americans at risk for institutional betrayal. J Black Psychol. 2013;41(2):121‐143. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials