Abstract

Objective

To develop claims‐based measures of comprehensiveness of primary care physicians (PCPs) and summarize their associations with health care utilization and cost.

Data Sources and Study Setting

A total of 5359 PCPs caring for over 1 million Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries from 1404 practices.

Study Design

We developed Medicare claims‐based measures of physician comprehensiveness (involvement in patient conditions and new problem management) and used a previously developed range of services measure. We analyzed the association of PCPs’ comprehensiveness in 2013 with their beneficiaries’ emergency department, hospitalizations rates, and ambulatory care‐sensitive condition (ACSC) admissions (each per 1000 beneficiaries per year), and Medicare expenditures (per beneficiary per month) in 2014, adjusting for beneficiary, physician, practice, and market characteristics, and clustering.

Principal Findings

Each measure varied across PCPs and had low correlation with the other measures—as intended, they capture different aspects of comprehensiveness. For patients whose PCPs’ comprehensiveness score was at the 75th vs 25th percentile (more vs less comprehensive), patients had lower service use (P < 0.05) in one or more measures: involvement with patient conditions: total Medicare expenditures, −$17.4 (−2.2 percent); hospitalizations, −5.5 (−1.9 percent); emergency department (ED) visits, −16.3 (−2.4 percent); new problem management: total Medicare expenditures, −$13.3 (−1.7 percent); hospitalizations, −7.0 (−2.4 percent); ED visits, −19.7 (−2.9 percent); range of services: ED visits, −17.1 (−2.5 percent). There were no significant associations between the comprehensiveness measures and ACSC admission rates.

Conclusions

These measures demonstrate strong content and predictive validity and reliability. Medicare beneficiaries of PCPs providing more comprehensive care had lower hospitalization rates, ED visits, and total Medicare expenditures.

Keywords: comprehensiveness, costs, measures, primary health care, quality of care, utilization

1. INTRODUCTION

While comprehensiveness is a key element of primary care,1, 2, 3, 4 due to the complexity of measuring its multiple dimensions, there are few ways to measure and track it.5, 6 Comprehensiveness is the extent to which the patient's primary care provider (clinician, practice, or team) recognizes and meets the large majority of the patient's physical and common mental health care needs, including prevention and wellness, and acute, chronic, and comorbid condition management.3, 7 The ability to address patients’ health care needs in the primary care setting has several dimensions, including the range of services offered, the depth and breadth of conditions managed, and the extent to which new problems can be managed by the primary care clinician.1, 3

More comprehensive care, as measured by surveys, is associated with less fragmentation of care across different specialists; fewer diagnostic tests, medications, and interventions; better health; lower costs;3, 8, 9, 10, 11 and improved equity (e.g., reduced disparities in disease severity as a result of earlier detection and prevention across different populations).12, 13, 14

To date, comprehensiveness has received less attention than other key elements of primary care, such as access or continuity, which are more easily measured, and coordination, which is now the focus of a variety of new payment models.15, 16 Without explicit measurement and support for its improvement, comprehensiveness may wither as other aspects of primary care (e.g., access, coordination) receive more resources and attention.6, 16

Survey research suggests that comprehensiveness is declining in the United States17, 18, 19, 20, 21 despite prior evidence suggesting numerous benefits. This decline is not the inevitable result of advances in modern medicine, but is largely a consequence of flawed incentives.22, 23, 24, 25 In the Netherlands, for example, comprehensiveness appears to be increasing26 and U.S. primary care is not as comprehensive as primary care in other countries.3, 27

To address these concerns, and to develop measures that are less costly and burdensome than surveys or chart abstraction, we developed two new Medicare claims‐based measures of comprehensiveness of primary care physicians (PCPs). This paper describes variations across PCPs on each of these metrics, as well as on a third, recently developed, claims‐based measure.28 We then examine associations of these measures with patient outcomes, focusing on emergency department (ED) utilization, hospitalizations, and costs of care.

2. METHODS

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), joined by thirty‐nine other private and public payers, launched the 4‐year comprehensive primary care (CPC) initiative in October 2012. CPC tested whether providing financial and technical support for particular enhanced primary care activities reduced costs and improved quality in 502 practices across seven U.S. regions. We used data that we had assembled for this larger study of the initiative on the 497 CPC practices enrolled at the end of the first quarter, and the 908 comparison group practices that we selected to have similar patient‐, practice‐, and market‐level characteristics using propensity score matching. These data provided access to a wide range of controlling variables, including practice characteristics for PCPs in these CPC and comparison practices.29, 30

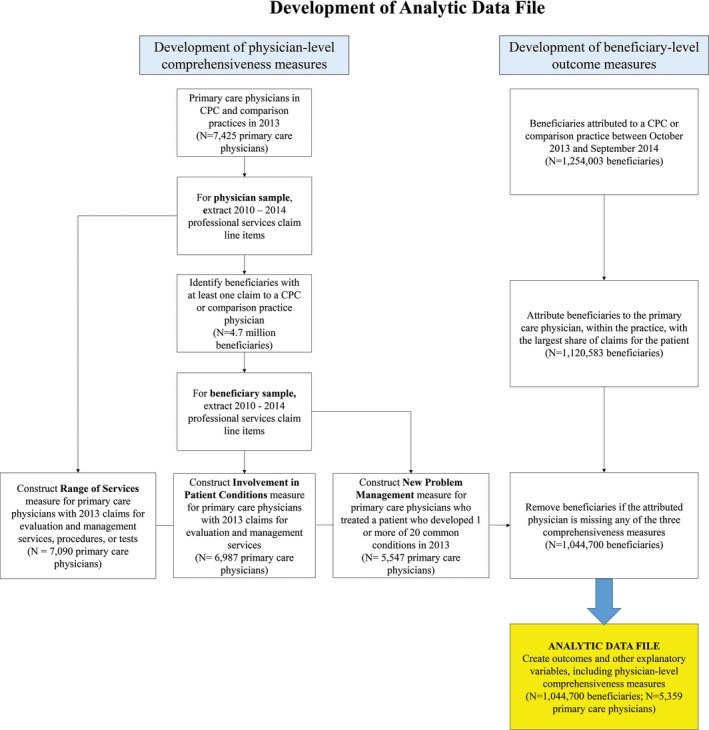

We first constructed physician‐level comprehensiveness measures for the over 7000 PCPs in CPC and comparison practices in 2013, using claims of all 4.7 million beneficiaries they had seen. In parallel, we constructed beneficiary‐level outcomes using all of these beneficiaries’ claims (for services received from all providers) (Figure 1). Beneficiary outcomes were based on claims data from 2014. We then ran regressions to examine how the physician‐level comprehensiveness measures were associated with beneficiary‐level outcomes.

Figure 1.

Creation of analytic sample of Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries treated by CPC and comparison group physicians [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.1. Data

We used Medicare fee‐for‐service (FFS) claims from the CMS Virtual Research Data Center's Research Identifiable Files for data on beneficiaries and physicians. Additional controlling variables, including data on practice and market characteristics, come from a range of sources including CPC and comparison practices’ application data to CMS, the Area Resource File, SK&A, the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty (MD‐PPAS), the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

2.2. Development of physician‐level comprehensiveness measures

2.2.1. Physician sample

Because this study measures comprehensiveness at the primary care physician level (national provider identifier [NPI]) and because comprehensiveness was not an explicit goal of the intervention, analyses combine PCPs from CPC and comparison practices. The CPC and comparison practices (as well as the CPC and comparison practices’ physicians) had similar characteristics. In addition, the comprehensiveness scores of physicians in the CPC group did not differ from those in the comparison group.

We identified PCPs in the practices in 2013 using these primary or secondary specialty codes in Medicare Data on Provider and Practice Specialty (MD‐PPAS): 11 (internal medicine), 08 (family practice), 37 (pediatric medicine), 38 (geriatric medicine), or 01 (general practice). We excluded hospitalists (category 5). We estimated the comprehensiveness of PCPs rather than nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), because of the low prevalence of NPs and PAs serving as a patients’ usual practitioner in our sample, and the difficulty of discerning all services independently provided by NPs/PAs because they commonly bill “incident to” services under a physician's NPI.

2.3. Physician‐level comprehensiveness measures

We developed two claims‐based measures (involvement in patient conditions and new problem management) and used a third, previously developed, range of services measure.28 We calculated a primary care physician‐specific score for each.

To calculate the range of services measure, we used FFS Medicare professional services claims from a CPC or comparison practice in 2013. To calculate the involvement in patient conditions and new problem management measures, we used FFS Medicare professional services claims to first identify beneficiaries who had at least one visit to a physician in a CPC or comparison practice in 2013. For these beneficiaries, we used all their FFS Medicare professional services claims (from primary care and specialists) from 2010 to 2014. We limited these claims to months where a beneficiary was alive and enrolled in Part A and Part B Medicare, not participating in managed care, and Medicare was the primary payer.

2.3.1. Involvement in patient conditions

This measure defines comprehensive clinicians as those who are involved in the care of the broad range of their patients’ health conditions (reflected in visit‐related diagnosis codes). Using claims, we identified the PCP or specialist who billed for the highest percentage of each patient's unique three‐digit International Classification of Disease (ICD‐9) diagnosis codes31 within a calendar year (2013), and designated this physician as the patient's most comprehensive physician. Focusing on the first three digits of the ICD‐9 codes minimizes potential differences in coding practices between different types of specialties.32 For each physician, we calculated the percent of patients seen that calendar year for whom the physician had the greatest involvement in the patient's conditions. (The Appendix S1 provides additional details on this and other measures.)

2.3.2. New problem management

This measure assesses the extent to which a physician manages a patient's new symptom or problem instead of referring them to (or the patient seeking) a specialist. A comprehensive primary care provider should be able to deal with the majority of health problems except those too uncommon in their practice to maintain competence.3 For each of the 20 most common reasons for visits to primary care in a population aged 65 and older (migraine, headache, urinary tract infection, gastrointestinal symptoms, skin disorders, back problems, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, depression, anxiety, arthritis and localized joint syndromes, obesity, asthma, ill‐defined conditions, upper respiratory conditions, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and thyroid disorders),31 we identified patients with an office‐based evaluation and management (E&M) claim for the problem in 2013, but no E&M claims (either office or non‐office‐based) for that same problem in the prior 24 months. For each patient identified as having a “new problem,” we designated the primary care physician who first treated the patient for the problem as the patient's index physician and that first visit as the index visit. We further limited our patient sample to those with (a) at least 20 months of Medicare FFS eligibility during the 24 months prior to the index visit and (b) at least 10 months of Medicare eligibility in the 12 months after the index visit. This ensured that all patients were observable during a substantial proportion of the periods before and after the index visit.

For each patient‐new problem combination, we calculated the proportion of new problem visits to the index physician out of all office‐based E&M visits for that new problem within 1 year of the index visit. We then calculated two numbers: (a) the average observed proportion of such new problem visits for each physician over all of his or her patient‐new problem combinations, and (b) the average predicted proportion. The predicted proportion was based on a regression model fit using data for all physicians and their patient‐new problem combinations that accounts for the effect of different new problems on the rate of visits to the index physician. We calculated the new problem management as the ratio of the observed and predicted proportions.

2.3.3. Range of services

We replicated the range of services measure originally constructed by Bazemore et al.28 This measure evaluates the breadth of services a physician provides across all patients, and defines more comprehensive physicians as those who provide a larger range of services. We restricted our claims to those with the first digit of the Berenson‐Eggers Type of Service (BETOS) code for E&M, procedures, or tests.33 For each physician, we identified their patients’ BETOS codes with line items and ranked them from most to least frequent. The final measure includes the counts of unique BETOS codes that account for 90 percent of the physician's line items in the year. For example, if Dr. Smith has 10 associated BETOS codes: M1A (x5), M1B (x4), and M2A (x1), 90 percent of her BETOS codes are accounted for by 2 line items (M1A and M1B), resulting in a range of services score of 2. See Appendix S1 for more detail.

2.4. Development of beneficiary‐level outcome measures

2.4.1 | Beneficiary sample Whereas the physician‐level comprehensiveness measures are based on how they treat all beneficiaries, we analyzed outcomes only for beneficiaries attributed to these physicians. Attribution occurred in two steps. First, we identified all beneficiaries attributed to the CPC and comparison practices based on where they received the largest share of primary care visits in the prior 2 years (see Appendix S1). We defined primary care visits as PCP's office/outpatient E&M, nursing home and home care, and Medicare and annual wellness visits, using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes. Second, we attributed each beneficiary to the attributed practice's PCP who provided the most primary care visits during a 32‐month look‐back period (October 2010 to June 2013). The total number of E&M visits to a primary care physician in a year was stable across years (mean of 5.2) and is consistent with prior literature.34 The (median) percent of E&M visits to beneficiaries’ attributed primary care physician (out of all primary care physician visits) was 75 percent.

Our final analytic dataset (Figure 1) consisted of 1 044 700 Medicare FFS beneficiaries cared for by 5359 PCPs within 497 practices participating in the CPC initiative and 907 comparison practices with similar market‐, practice‐, physician‐, and patient‐level characteristics as the CPC practices.29

2.5. Beneficiary‐level outcomes

To ascertain PCP comprehensiveness prior to measuring patient outcomes, we assessed physician‐level comprehensiveness in 2013 and beneficiary‐level outcomes in 2014. We modeled four outcome measures:

Medicare FFS expenditures for all Part A and B services per beneficiary per month, excluding third‐party and beneficiary liability payments, and Part D prescription payments.

Hospital admissions per 1000 beneficiaries per year is the annualized hospitalization rate per 1000 beneficiaries of all admissions reported in the inpatient file for the year. Transfers between facilities are counted as a single admission.

ED visits per 1000 beneficiaries per year is the annualized number of ED visits, including observation stays and visits that lead to a hospitalization, per 1000 beneficiaries.

Hospital admissions for ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions (ACSCs) per 1000 beneficiaries per year is a subset of hospital admissions based on the definition developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) of potentially avoidable hospitalizations for ACSCs, defined as conditions for which timely, high‐quality outpatient care can often prevent complications or more serious disease. We count patients as having a preventable hospitalization if the diagnosis on their claim is any of the following: diabetes related (short‐term complications, long‐term complications, uncontrolled diabetes, and rate of lower extremity amputation), congestive heart failure (CHF), COPD in asthma or older adults, coronary artery disease (including angina without procedure, hypertension, hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction [AMI], hospitalization for acute stroke, and combined AMI or stroke), dehydration, bacterial pneumonia, or urinary tract infection. (See online Appendix S1.)

2.6. Control variables

Beneficiary‐level control variables included: the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) score, race, age, sex, Medicare eligibility reason, and dual status (eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid). We controlled for the characteristics of the beneficiary's physician, including sex, age, and specialty (e.g., family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics). Control variables for the beneficiary's practice included the number of physicians in the practice, ownership type (independent physician owned vs owned by a larger entity), whether the practice was in the CPC or comparison group, prior recognition as a medical home, and whether at least one physician in the practice met meaningful use criteria. Including these practice characteristics as control variables accounts for resource availability, health care technology use, and a practice's ability to provide advanced primary care, which can affect the comprehensiveness of care and patient outcomes. The market characteristics of the beneficiary's practice included the median household income, Medicare Advantage penetration rate, urbanicity, region, and location in a medically underserved area, which can affect physician practice patterns in an area and lead to geographic variation in comprehensiveness and outcomes.

2.7. Analysis and models

We established a physician's comprehensiveness score prior to assessing patients’ outcomes. For each measure of comprehensiveness, we analyzed the association between a beneficiary's attributed PCP's comprehensiveness measure for 2013 and outcomes for 2014.

We tested for associations between each individual comprehensiveness measure (at the physician level) and beneficiary‐level outcomes. Hospitalizations, ED visits, and ACSC admissions were modeled using zero‐inflated negative binomial regression (to account for possible overdispersion in utilization counts and the large percentage of zeroes for beneficiaries with no use during a year). Total Medicare expenditures were modeled using OLS regression. All outcomes were Winsorized at the 99th percentile (values above the 99th percentile were reset to the 99th percentile) to avoid the potentially distorting effects of extreme outliers. Each regression model controlled for the same beneficiary‐level characteristics (of the beneficiary, and of their physician, practice, and market) identified in the year 2012. All models accounted for clustering of patient outcomes within practices (which included both patients seeing the same physician and those seeing different physicians within the same practice). Each observation (beneficiary) was weighted to account for the percentage of the year the beneficiary was Medicare eligible. For beneficiaries in the comparison practices only, the weights were adjusted for the practice‐level matching.

We conducted a sensitivity test by rerunning the expenditure regressions with practice fixed effects instead of the practice‐level control variables. The conclusions and general order of magnitude were similar, suggesting that omitted variable bias from unobserved practice characteristics was unlikely to be a concern. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14 Version 15.1, College Station, TX, USA.

For better interpretability of the effects of physician comprehensiveness measures on beneficiary‐level outcomes that were statistically significant (P < 0.05), we report both the magnitude and percentage difference in the adjusted mean outcomes for an increase in the comprehensiveness score from the 25th to 75th percentile among all physicians in the analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

Beneficiary characteristics are presented in Table 1. Compared to the national Medicare FFS beneficiary population in 2012, beneficiaries in our sample had a similar age distribution, but were slightly more likely to be female (58 percent vs 55 percent), and white (91 percent vs 80 percent), and less likely to be dually eligible for Medicaid (12 percent vs 22 percent) (data not shown).35

Table 1.

Beneficiary, primary care physician, and practice characteristics (percentages unless otherwise noted)

| Characteristics | CPC and comparison groups combined |

|---|---|

| Beneficiary characteristics | |

| Number of beneficiaries | 1 044 700 |

| Age | |

| Under 65 | 17.51 |

| 65‐74 | 45.02 |

| 75‐84 | 26.57 |

| 85 and over | 10.91 |

| Female | 58.28 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 91.44 |

| Black | 4.28 |

| Native American | 1.20 |

| Other | 3.08 |

| Dual eligible | 12.14 |

| Original reason for Medicare eligibility | |

| Age | 78.88 |

| Disability | 20.99 |

| ESRD | 0.12 |

| HCC score (continuous) | 0.99 (0.65) |

| Primary care physician characteristics | |

| Number of PCPs | 5359 |

| Age | |

| Under 30 | 0.39 |

| 31‐50 | 52.45 |

| Over 50 | 47.15 |

| Female | 37.30 |

| Specialty | |

| Family practice | 59.34 |

| Internal medicine | 38.48 |

| General practice | 0.95 |

| Geriatric medicine | 1.03 |

| Pediatric medicine | 0.21 |

| Practice characteristics | |

| Number of practices | 1404 |

| Recognized medical home | 38.09 |

| Any physician meeting meaningful use criteria | 78.83 |

| Multispecialty practice | 16.42 |

| Owned by a larger organization | 54.75 |

| Number of clinicians at practice site | |

| 1 | 17.00 |

| 2‐3 | 31.15 |

| 4‐5 | 23.08 |

| 6 or more | 28.77 |

| Located in a medically underserved area | 12.85 |

| Medicare Advantage penetration rate in county | 24.06 (11.37) |

| Median household income in county (Dollars) | 53 219.39 (12 389.58) |

| Percentage urban population in county | 76.39 (20.55) |

CPC, Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative; HCC, Hierarchical Condition Categories; PCP, primary care physician; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Measure properties

Each of the comprehensiveness measures had good variation across PCPs (Table 2). Regarding the first measure in the table below, if a PCP's involvement in patient conditions score is 0.80 (75th percentile), then this physician was the most involved in patient conditions (compared to all other physicians that patient saw, including specialists) for 80 percent of the patients the provider billed for in a calendar year. A PCP with a score of 0.58 (25th percentile) was only the most comprehensive physician (most involved in patient conditions) for 58 percent of all the patients that the physician billed for in the calendar year.

Table 2.

Mean and percentile distribution of the three measures of comprehensiveness

| Comprehensiveness measure | Mean | SD | Min | 5th percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 95th percentile | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement in patient conditions | 0.68 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| New problem management | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.24 |

| Range of services | 4.90 | 1.88 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 13.00 |

SD, standard deviation.

For the new problem management measure, a score of 1 means that the physician manages new conditions at the same rate as the average physician across the 20 conditions. A mean score of 0.97 (25th percentile) indicates that the physician had a lower rate of managing the new conditions herself than the condition‐specific average physician scores, and was less comprehensive at managing new conditions than 75 percent of PCPs observed. A physician with a mean score of 1.05 (75th percentile) indicates that the physician had a higher rate of managing each of the new conditions herself than the condition‐specific average physician scores, and was more comprehensive than 75 percent of other PCPs who also treated those conditions.

For the range of services measure, we contrast the PCP with a score of 6 (75th percentile) to a PCP with a score of 3 (25th percentile). A PCP with a score of 6 had 6 BETOS codes that accounted for 90 percent of the physician's line items in the preceding year, a broader range of services (as reflected by BETOS codes) than 75 percent of PCPs observed. In contrast, PCPs in the bottom 25th percentile had only three different BETOS codes that accounted for 90 percent of the physician's line item charges. (Our interquartile range and median were similar to that of Bazemore et al's most recent work using the 90 percent threshold—personal communication, August 24, 2018.)

There was little correlation between the range of services measure and either the involvement in patient conditions (+0.005) or new problem management (+0.042) measures. There was a stronger and statistically significant correlation between involvement in patient conditions and new problem management (+0.556). Generally, these findings indicate that each measure captured different aspects of comprehensiveness.

3.3. Reliability assessment of the comprehensiveness measures

We used two approaches to compute the reliability of the comprehensiveness measures. For the involvement in patient conditions measure and the new problem management measure, we computed signal‐to‐noise (SNR) reliability statistics.36 The SNR captures precision of measurement at the physician level.37 For the range of services measures, we assessed reliability using a split‐half method. Split‐half reliability captures repeatability and reproducibility for the same population at the same time.38 We split each physician's patients, computed the measure score for each physician in each split sample and then assessed correlations between measure scores (for the same physician across all physicians) in two samples. The mean SNR reliability of the involvement in patient conditions measure was high (0.94), with 97.7 percent of individual physicians having reliability scores above the conventionally acceptable level of 0.70. The mean SNR reliability of the new problem management measure is 0.69, with 60 percent of individual physicians having reliability scores above the conventionally acceptable level of 0.70. For the range of services measure, Spearman's rho was 0.93 for both the final sample and the all‐physician sample, indicating high repeatability and reproducibility of the measure result across two half‐samples. (See Appendix S1 for details.)

3.4. Associations with outcomes

We turn now to showing the association of a physician's comprehensiveness and beneficiaries’ outcomes. After adjusting for beneficiary‐, physician‐, and practice‐level characteristics, we calculated the differences in beneficiaries’ adjusted mean outcomes for patients whose physician's comprehensiveness score was at the 25th percentile and patients whose physician was at the 75th percentile, for each comprehensiveness measure separately (Table 3). The direction (sign) of the associations was in the expected direction. Having a physician at the 75th percentile on the involvement in patient conditions measure was associated with $17.4 (2.2 percent) lower total Medicare expenditures per beneficiary per month (P < 0.01), 5.5 (1.9 percent) lower hospitalizations per thousand beneficiaries per year (P < 0.05), and 16.3 (2.4 percent) fewer ED visits per thousand beneficiaries per year (P < 0.01) compared to having a physician at the 25th percentile. Having a physician at the 75th percentile on the new problem management measure was associated with $13.3 (1.7 percent) lower total Medicare expenditures per beneficiary per month (P < 0.01) compared to having a physician at the 25th percentile, 7.0 (2.4 percent) fewer hospitalizations per thousand beneficiaries per year (P < 0.001), and 19.7 (2.9 percent) fewer ED visits per thousand beneficiaries per year (P < 0.001). Having a physician at the 75th percentile on the range of services measure was associated with 17.1 (2.5 percent) fewer ED visits per thousand beneficiaries per year (P < 0.01) compared to having a physician at the 25th percentile. There were no statistically significant associations between the comprehensiveness measures and ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions hospitalization rates.

Table 3.

Associations between primary care physician comprehensiveness and patient outcomes

| Comprehensiveness measure | Outcome | Difference in outcome between 25th and 75th percentile for comprehensiveness measure | Difference in outcome between 25th and 75th percentile for comprehensiveness measure (as percentage) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement in patient conditions | Total Medicare expenditures | −17.36 | −2.18 | <0.01 |

| Number of hospitalizations | −5.49 | −1.87 | <0.05 | |

| Number of ED visits | −16.26 | −2.37 | <0.01 | |

| Number of ACSC admissions | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.899 | |

| New problem management | Total Medicare expenditures | −13.30 | −1.68 | <0.01 |

| Number of hospitalizations | −6.95 | −2.37 | <0.001 | |

| Number of ED visits | −19.75 | −2.88 | <0.001 | |

| Number of ACSC admissions | −0.36 | −0.58 | 0.67 | |

| Range of services | Total Medicare expenditures | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.911 |

| Number of hospitalizations | −4.09 | −1.40 | 0.224 | |

| Number of ED visits | −17.10 | −2.50 | <0.01 | |

| Number of ACSC admissions | −0.56 | −0.90 | 0.629 |

Each row represents a separate model, with outcomes Winsorized to the 99th percentile and adjusted for physician, practice, and patient characteristics. Each model accounts for clustering of patient outcomes within practices, for both patients seeing the same physician and those seeing different physicians within the same practice.

For each outcome, we present the numeric change and percentage difference in the adjusted mean outcome for an increase in the comprehensiveness score from the 25th to 75th percentile among all physicians in the analysis.

Medicare expenditures are expressed per beneficiary per month.

ED, hospitalization, and ACSC rates are per 1000 beneficiaries per year.

The reported P‐values are from testing the significance of the marginal effects (instantaneous rate of change). Nearly identical P‐values were found when testing the significance of the effect going from the 25th to 75th percentiles of the comprehensiveness measures.

As expected, among the control variables, older patient age, higher HCC score, Medicare eligibility based on a disability, and ESRD were associated with higher utilization on all four outcome measures. Practice ownership type and size were not consistently associated with the outcomes.

4. DISCUSSION

We described three claims‐based measures of PCP comprehensiveness (involvement in patient conditions, new problem management, and range of services) and summarized their associations with their attributed Medicare FFS beneficiaries’ utilization and cost outcomes. Each measure demonstrated considerable variation across PCPs, indicating that the comprehensiveness of PCPs caring for Medicare beneficiaries varies substantially. The three measures were not meaningfully correlated with one another, suggesting they each reflect distinct aspects of comprehensiveness. For example, a clinician may score high on the management of new problems, indicating that she uses her diagnostic acumen to manage a patient's new symptom (e.g., a new rash) instead of referring the patient immediately to a specialist (e.g., dermatologist). That same clinician, however, may not provide care in a range of settings or perform particular procedures and thus use a narrow range of BETOS codes, resulting in a lower score on the range of services measure.

These measures also have predictive validity; a higher score on each measure was associated with slightly better outcomes in the clinically and conceptually expected direction, controlling for key patient, physician, practice, and market characteristics. Medicare beneficiaries attributed to physicians who provide more comprehensive care had lower utilization of services including lower rates of ED visits for all three measures, lower hospitalization rates for two measures (new problem management and involvement in patient conditions), and lower total Medicare expenditures for two measures (new problem management and involvement in patient conditions). There were no significant associations with ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions hospitalization rates. Finally, because the measures are based on claims, they are inexpensive to collect and limit burden on clinicians and patients.

While a thoroughly comprehensive physician might do well on all three aspects of comprehensiveness, we noted considerable variability across physicians. We have yet to explore how combinations of these different comprehensiveness measures may be associated with outcomes. Nor have we addressed how these measures may interact with other features of the practice, especially core features3 like access, continuity, and coordination. More comprehensive care may result in fewer referrals to specialists, and thus improved continuity and reduced requirements for coordination with other clinicians and practices. Nonetheless, our work shows that after controlling for a variety of patient‐, physician‐, practice‐, and market‐level characteristics, PCPs vary in meaningful ways in their range of services, new problem management, and involvement in patient conditions.

These findings add to prior work which focused on comparing comprehensiveness across physician specialties (PCPs compared to other specialists; family practitioners compared to general internists), for example, using Medicare claims and visit abstraction data from the National Ambulatory Care Medical Survey (NAMCS).32, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Our findings that increased range of services (one aspect of comprehensiveness) is associated with lower ED visits are also consistent with a recent study28 examining a sample of family physicians.

We created measures of individual physician comprehensiveness, but realize that modern physicians do not work in isolation. Some features of primary care, such as accessibility and coordination, can be enhanced by well‐functioning primary care teams (with whom the physician works to provide care).44 The extent to which comprehensiveness, however, is chiefly a characteristic of the individual clinician or of the team remains both a conceptual and an empirical question. Exploring this will require other data sources (such as analysis of electronic health records [EHRs] and practice observation), since Medicare claims data do not presently support developing and testing team‐based comprehensiveness measures.

There are advantages and disadvantages to creating comprehensiveness measures using claims data.6 Advantages include claims’ availability, relatively low cost (compared to surveys, direct observation, or EHRs), and national scope. Claims include both clinical and procedural codes and site of care (outpatient, inpatient, ED, etc.), are consistent across settings, and are likely to be fairly accurate due to the potential use of audits and regulator enforcement. Thus, they are likely to capture the range of conditions recognized and treated by a practice. While EHR data can be useful within a practice, claims also capture services patients received outside of their usual provider's or health system's setting and EHR. The current lack of EHR interoperability within (much less across) communities makes it challenging to gather the data across the full range of providers seen in order to create our comprehensiveness measures.

Disadvantages to using claims data are a limitation of our study. First, the lack of clinical nuance in claims introduces challenges. In the case of the range of services measure, for example, one cannot ascertain whether all the BETOS services delivered were clinically necessary. Likewise, claims analyses cannot easily identify the failure to deliver needed services, such as in the new problem measure, where a highly comprehensive PCP might sometimes wait too long to refer a patient to a specialist. However, determining timeliness and appropriateness of real‐time clinical decisions is presently not possible with any secondary data analysis, even of EHRs.45

Another difficulty with claims is that we cannot ascertain the degree to which a PCP actively managed the diagnoses listed for a given visit. Differences in the extent to which PCPs include a patient's multiple conditions (ICD codes) on their submitted claims could be exacerbated by diagnosis‐driven risk‐adjustment methodologies where providers may be incentivized to document and code more diagnoses.46, 47 Our involvement in patient conditions measure was the most susceptible to such spurious variation in diagnosis coding, yet we did not find a difference in this measure between physicians in CPC and comparison practices (despite CPC practices receiving higher monthly per‐beneficiary, per‐month payments for the sickest patients, as measured by HCC scores). We also created other measures less likely to suffer from this limitation, such as the new problem measure. In future work, we will update the ICD‐9 code‐based comprehensiveness measures to account for ICD‐10 codes which went into effect October 1, 2015.

Finally, it is possible that better outcomes for patients whose PCPs score higher on a comprehensiveness measure are due to other unmeasured features of this provider or practice setting that are correlated with comprehensiveness. Additional work will be required to confirm that improvement in performance on these measures can result in important differences in care overall, and in subgroups of care with more complex conditions.

However helpful these findings might be to the primary care researcher community to highlight the dimensions of comprehensiveness and their relevance to patient outcomes, these claims‐based measures are not suitable for high‐stake “performance metrics” for individual primary care clinicians or practices. As noted above, these measures are susceptible to individual clinician or practice organization changes in coding practices. While some coding response to such measures (e.g., documenting awareness of a broader range of patient's conditions) might not be harmful per se, others could be problematic. One example of this risk might be PCPs delivering an unhelpfully broad range of BETOS services to enhance their range of services scores. Even more worrisome might be clinicians attempting to improve their new problem management score by not referring patients who present for problems outside their competence. Furthermore, as primary care practices adapt to new payment models, claims will not capture the substitution of E&M visits with nonbillable activities like telephone and email conversations with patients (or delivery of care by care team members who cannot bill for care). Clinically meaningful and administratively actionable measures of comprehensiveness will likely require use of aggregated EHR data encompassing all patient encounters or other emerging aggregated data sources that can reliably observe actual care (as opposed to coding approaches).

5. CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations and cautions, this work documents three different (but complimentary) claims‐based measures of comprehensiveness and offers initial evidence on their predictive value for a large sample of 5359 PCPs and over 1 million Medicare FFS beneficiaries. These comprehensiveness measures demonstrated considerable variation across PCPs and were not correlated with one another, suggesting they each reflect distinct aspects of PCP comprehensiveness. Furthermore, variations in each of these measures of PCP comprehensiveness were associated with important variations in beneficiary costs and service use. In particular, beneficiaries of PCPs that were more comprehensive on the involvement in patient conditions measure and the new problem management measure had significantly lower total Medicare expenditures and lower rates of ED visits and hospitalizations, controlling for a wide range of patient, physician, and practice characteristics. Beneficiaries of PCPs who provide a more comprehensive range of services had significantly lower rates of ED visits.

Additional research should investigate the robustness of these findings in national Medicare FFS, commercially insured, and Medicaid populations (ideally using an all‐payer database), and explore implications for other groups of patients as well as other primary care clinicians (NPs and PAs) and primary care teams. Our findings, when taken in the context of prior literature, suggest that promoting comprehensiveness of primary care could avert preventable ED visits and hospitalizations and lower overall costs.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contract HHSM‐500‐2010‐00026I/HHSM‐500‐T0006 (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02320591). We thank Barbara Carlson, Sheng Wang, Danni Tu, and Cathy Lu for their assistance with reliability testing of our comprehensiveness measures.

Disclaimer: The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies.

O'Malley AS, Rich EC, Shang L, et al. New approaches to measuring the comprehensiveness of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:356–366. 10.1111/1475-6773.13101

REFERENCES

- 1. Institute of Medicine . Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1996. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/5152/primary-care-americas-health-in-a-new-era. Accessed August 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Primary Health Care: A Joint Report by the Director‐General of the World Health Organization and the Executive Director of the United Nations Children's Fund. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4. White KL. Primary medical care for families—organization and evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1967;277:847‐852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haggerty JL, Beaulieu MD, Pineault R, et al. Comprehensiveness of care from the patient perspective: comparison of primary healthcare evaluation instruments. Healthc Policy. 2011;7(special issue):154‐166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Malley AS, Rich EC. Measuring comprehensiveness of primary care: challenges and opportunities. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):S568‐S575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . About the CAHPS® patient‐centered medical home (PCMH) item set. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality document 1314; 2011. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/cahps/surveys-guidance/survey4.0-docs/1314_About_PCMH.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2018.

- 8. Starfield B, Chang HY, Lemke KW, Weiner JP. Ambulatory specialist use by nonhospitalized patients in US health plans: correlates and consequences. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32(3):216‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(616):e742‐e750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore AW. Primary care and why it matters for U.S. health system reform. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):806‐810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sans‐Corrales M, Pujol‐Ribera E, Gené‐Badia J, Pasarin‐Rua MI, Iglesias‐Pérez B, Casajuana‐Brunet J. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):308‐316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Starfield B. State of the art in research on equity in health. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31(1):11‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee A, Kiyu A, Milman HM, Jimenez J. Improving health and building human capital through an effective primary care system. J Urban Health. 2007;84(suppl 3):i75‐i85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457‐502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saultz J. The importance of being comprehensive. Fam Med. 2012;44(3):157‐158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bitton A. The necessary return of comprehensive primary health care. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2020‐2026. 10.1111/1475-6773.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2364‐2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peterson LE, Fang B, Puffer JC, Bazemore AW. Wide gap between preparation and scope of practice of early career family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):181‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Safran DG. Defining the future of primary care: what can we learn from patients? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):248‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Stuckey HL, Chuang CH, Lehman EB, Hwang KO, et al. A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US physician weight counseling. Med Care. 2013;51(2):186‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(2):163‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edwards ST, Mafi JN, Landon BE. Trends and quality of care in outpatient visits to generalist and specialist physicians delivering primary care in the United States, 1997–2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:947‐955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morra D, Nicholson S, Levinson W, et al. US physician practices versus Canadians: spending nearly four times as much money interacting with payers. Health Aff. 2011;30(8):1443‐1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shipman SA, Sinsky CA. Expanding primary care capacity by reducing waste and improving the efficiency of care. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):1990‐1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berenson RA, Rich EC. US approaches to physician payment: the deconstruction of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:613‐618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van de Lisdonk EH, Van Weel C. New referrals, a decreasing phenomenon in 1971‐94: analysis of registry data in the Netherlands. BMJ. 1996;313(7057):602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bindman AB, Forrest CB, Britt H, Crampton P, Majeed A. Diagnostic scope of and exposure to primary care physicians in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States: cross sectional analysis of results from three national surveys. BMJ. 2007;334:1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL Jr. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dale SB, Ghosh A, Peikes DN, et al. Two‐year costs and quality in the comprehensive primary care initiative. New Eng J Med. 2016;374(24):2345‐2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Comprehensive primary care initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-primary-care-initiative/. Accessed August 25, 2018.

- 31. ICD‐9‐CM Diagnosis and Procedure Codes . https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/ICD9providerdiagnosticcodes/codes.html. Accessed August 25, 2018.

- 32. Pace WD, Dickinson LM, Staton EW. Seasonal variation in diagnoses and visits to family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):411‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Berenson Eggers type of service (BETOS). 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/downloads/betosdesccodes.pdf. Previously available at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets/BETOS.html. Accessed December 2017.

- 34. Romaire MA, Haber SG, Wensky SG, McCall N. Primary care and specialty providers: an assessment of continuity of care, utilization, and expenditures. Med Care. 2014;52(12):1042‐1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare Beneficiary Characteristics. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/Medicare_Beneficiary_Characteristics.html. Updated January 18, 2017. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 36. Adams JL. The Reliability of Provider Profiling: A Tutorial. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2009. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR653.html. Accessed April 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Quality Forum . Guidance for Measure Testing and Evaluating Scientific Acceptability of Measure Properties. 2011. https://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=70943. Accessed August 27, 2018.

- 38. Kazis LE, Rogers W, Rothendler J, et al. Outcome Performance Measure Development for Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2017. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1800/RR1844/RAND_RR1844.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279(17):1364‐1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rivo ML, Saultz JW, Wartman SA, DeWitt TG. Defining the generalist physician's training. JAMA. 1994;271(19):1499‐1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schneeweiss R, Rosenblatt RA, Cherkin DC, Kirkwood CR, Hart G. Diagnosis clusters: a new tool for analyzing the content of ambulatory medical care. Med Care. 1983;21(1):105‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hammermeister K, Bronsert M, Henderson WG, et al. Risk‐adjusted comparison of blood pressure and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) noncontrol in primary care offices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(6):658‐668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Franks P, Clancy CM, Nutting PA. Defining primary care: empirical analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Med Care. 1997;35(7):655‐668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bodenheimer T. Building Teams in Primary Care: Lessons Learned from the Field. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2007. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-BuildingTeamsInPrimaryCareLessons.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Converse L, Barrett K, Rich E, Reschovsky J. Methods of observing variations in physicians’ decisions: the opportunities of clinical vignettes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(Suppl 3):S586‐S594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Savings from the Medicare physician group practice demonstration. JAMA. 2013;309(1):30‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nelson L. Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on value‐based payment. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office working paper 2012‐01; 2012. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012-01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials