Abstract

Objective

To develop the first standardized definition of the patient‐centered dental home (PCDH).

Data Sources/Study Setting

Primary data from a 55‐member national expert panel and public comments.

Study Design

We used a modified Delphi process with three rounds of surveys to collect panelists’ ratings of PCDH characteristics and open‐ended comments. The process was supplemented with a 1‐month public comment period.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We calculated median ratings, analyzed consensus using the interpercentile range adjusted for symmetry, and qualitatively evaluated comments.

Principal Findings

Forty‐nine experts (89%) completed three rounds and identified eight essential PCDH characteristics, resulting in the following definition: “The patient‐centered dental home is a model of care that is accessible, comprehensive, continuous, coordinated, patient‐ and family‐centered, and focused on quality and safety as an integrated part of a health home for people throughout the life span.”

Conclusions

This PCDH definition provides the foundation for developing measures for research, care improvement, and accreditation and is aligned with the patient‐centered medical home. Consensus among a broad national expert panel—including provider, payer, and accreditation stakeholder organizations and experts in medicine, dentistry, and quality measurement—supports the definition's usability and its potential to facilitate medical‐dental primary care integration.

Keywords: coordinated‐care models, integrated care, modified Delphi process, patient‐centered dental home, patient‐centered medical home

1. INTRODUCTION

The patient‐centered medical home (PCMH) is a model of primary care service delivery designed to improve the integration, coordination, and quality of medical care for patients. Originally developed in the 1970s to improve care coordination for children with special health care needs,1 the PCMH model has since evolved considerably to be relevant to individuals regardless of age or health status, especially those with multiple chronic health conditions.2 The PCMH model of care is often seen as assisting efforts to achieve the triple aim of improving population health, patient experiences with care, and health care costs3 and, hence, has been incorporated into numerous state and federal policy initiatives to transform and improve health care delivery. This model, however, has advanced almost entirely in the medical sphere and has rarely been used to improve dental care delivery, evaluate the quality of dental care, or assist with the integration of and coordination between medical and dental care.

Currently, in the United States, the payment and delivery systems for medical and dental care are quite separate, as are the measures used for evaluating quality.4 In contrast to medical subspecialties, dental education, insurance, and care delivery lack substantive connection to the medical care delivery system. Thus, it is not surprising that the PCMH has not become the framework for researching quality in dentistry or coordinating across medical‐dental providers to improve patient‐centered care. Yet such a framework would contribute significantly to research, quality assessment within dentistry, and the integration and understanding between medicine and dentistry.

This article describes the development of a standardized definition for a dental counterpart to the PCMH, called the patient‐centered dental home (PCDH), the first step in developing a dental corollary to the PCMH. The PCDH model of care is intended to fill the current void in dentistry and create a bridge to facilitate medical‐dental integration. The PCDH development process described in this article is based on decades of research and policy development that identified ways to define and measure the PCMH model of care. To improve the likelihood of adoption by the dental community, this large, consensus panel‐driven process involved a spectrum of national experts and organizational representatives from the dental research, provider, public health, and accreditation communities. The panel also included experts and organizational representatives from outside dentistry who are familiar with health system transformation, patient‐centered care models, and accreditation to promote the applicability of the PCDH model for cross‐disciplinary coordination and integration.

In dentistry, the concept of a dental home was introduced in the early 2000s and applied mainly to pediatric dental care.5 However, since that time, patient‐centered dental home models have not experienced standardization in their definitions and measurements in the published literature or in practice.6 Quality measures specific to the needs of dental quality assessment and assurance are under development by organizations (such as the Dental Quality Alliance) that meet the standards of recognized institutions (such as the National Quality Forum).7 The PCDH can serve as the foundational framework for these ongoing measure development efforts, as it is clear that a measurement framework is critically important to enable systematic quality assessment and improvement.8 Having an established PCDH framework is therefore important for the identification and development of quality metrics at both the system and practice level to evaluate oral health care delivery and quality and to foster cross‐system communication in ways that can assist medical‐dental integration.9

The need for a PCDH model for medical‐dental integration is enhanced by the growing recognition of the importance of coordinated health care delivery, where the PCMH is often identified as a model for transforming and improving care delivery. The integration of dentistry into accountable care organization development and other value‐based purchasing arrangements could be enhanced by the development of a PCMH‐based PCDH. For example, with a standardized approach to measuring a PCDH, health systems or plans would be more confident in their ability to verify that dental practices meet a certain level of quality that they otherwise would not have been able to evaluate effectively; as a result, health plans and health care providers could be more confident about the dental providers and plans with whom they may want to integrate.

The broad involvement of nationally representative experts and organizations in the PCDH development process is an attempt to learn from the PCMH development processes that occurred in parallel with numerous organizations identifying their own PCMH definitions and measurements.10 For example, although the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the NCQA have traditionally been leaders in defining and certifying PCMHs, a proliferation of PCMH definitions and measurement and certification tools remains in use in both the published literature and in practice.11, 12, 13 In addition, multiple accrediting organizations, including the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), have developed standards to measure the extent to which medical practices meet the principles of the PCMH model and certify those that meet a minimum set of core standards.14, 15 With these varying definitions and standards, the health services research community has been challenged in establishing a cohesive body of evidence regarding the effectiveness of PCMH models in improving care quality and health outcomes.16 Thus, the value of developing a single, nationally recognized definition of a PCDH and associated measure sets, while the PCDH activities are still in a more developmental state, could produce less confusion for quality assessment and outcomes evaluation and improve the coordination and integration between dental providers and broader health systems.

Consequently, a central tenet of our PCDH effort was to learn from the evolution of the PCMH and use a consensus‐building process among a broad group of national stakeholders, both within and outside of dentistry, to establish a standard definition of a PCDH that reflects a synthesis of input by those most likely to develop, implement, or assess a dental home and that can be used in a wide range of settings and for multiple purposes (e.g., care delivery improvement, accreditation, policy development, and research). The broad stakeholder engagement also was designed to reduce the potential for parallel development or perceived competition with other patient‐centered care models for dentistry.

This paper presents the identification of the first standardized definition of a PCDH, which is first of a four‐stage PCDH model development process. The PCDH definition development included the identification of the essential characteristics of a PCDH using a large group consensus approach. This development process integrated existing medical home and dental home attributes into a single standardized definition that incorporated the essential characteristics of a PCDH to guide and support care delivery, research, performance measurement, system improvement, and medical‐dental integration. The ultimate goal of this project is to establish an accepted PCDH model of care, including a measurement framework connecting the essential characteristics with actionable tools to measure and improve quality, that can be used across various dental and medical care delivery settings (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Four‐level framework used for PCDH model development [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2. METHODS

We used a modified Delphi process to systematically obtain expert opinion through a structured group communication process to address the following question: What are the essential characteristics of a patient‐centered dental home that are central to developing a standardized definition of a PCDH? The Delphi process solicits anonymous feedback from individuals through several rounds of questionnaires, sharing responses with the panel between rounds, to arrive at group agreement.17

The key determinations that must be made when designing a Delphi process include expert panel composition, size, and recruitment process; data collection mode; questionnaire design and rating scale; number of Delphi rounds and stopping criterion; quantitative and qualitative analysis methods; and criteria for determining agreement.18, 19 A description of this process follows.

2.1. Expert panel recruitment

The national advisory committee (NAC) that served as the expert panel for this study was assembled through a purposive sampling process that included snowball sampling techniques (Table S1). Snowball sampling, sometimes referred to as chain sampling, is a non‐probability sampling technique through which we used the first NAC members, who were recruited based on areas of expertise and organizational appropriateness identified in advance by the project team, to suggest additional members who they believed had relevant expertise for the project.20

Through this process, we ended up with a large and heterogeneous group of experts representing dental care, medical care, public health, health services research, health policy, and accrediting bodies in order to achieve the relevant range of stakeholders with expertise in the development, implementation, or assessment of patient‐centered medical and dental homes. Ensuring appropriate content expertise and stakeholder representation, rather than targeting a specific sample size, guided recruitment. Delphi participants qualified based on their individual or organizational expertise21 in the following topics: PCMH development or implementation; health policy; clinical dental care across the age spectrum; public and population health; oral health services research; and quality metric development and use in medicine and dentistry for government, group practice, or accreditation purposes.

Assembling a heterogeneous group of experts for a Delphi process commonly results in a relatively large number of participants, as it did in this case.18, 19 In September 2015, we contacted 63 individuals identified as content experts or representatives of stakeholder organizations through email invitations that included a description of the study and expected time commitment. Follow‐up requests were sent up to three times during the subsequent 2 months to those who did not respond. When requested by invitees, phone discussions also occurred during the recruitment process. The resulting NAC included 55 members (Table S1).

2.2. Participant anonymity

One of the benefits of the Delphi process is that it allows individual participation to be anonymous, thereby promoting candid responses and full participation. For the purposes of transparency and credibility, it was determined a priori that participation would be “quasi‐anonymous”;18 that is, the NAC members would be known to the researchers and other participants and disclosed in publications and reports. NAC members were permitted to opt out of having their names disclosed publicly, but no member chose to do this. Individual responses to the questionnaires remained confidential with only aggregated summaries and de‐identified comments available to NAC members and in reports.

2.3. Questionnaire development and administration

The Delphi process solicited anonymous individual feedback through successive rounds of questionnaires that included Likert‐type scale ratings and open‐ended comments. Between‐round feedback was delivered to the NAC via summaries of the ratings and open‐ended comments for consideration during the next round of ratings. These steps were repeated in an iterative process to develop group consensus. The questionnaire for each round was developed by three members of the research team, implemented in Qualtrics,22 and pilot‐tested by the other members of the research team and external project advisors.

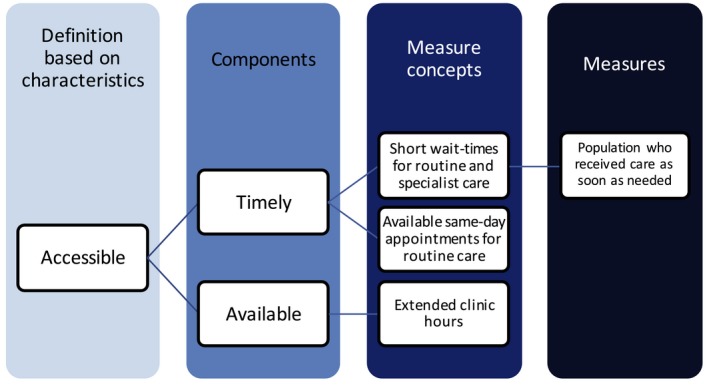

In the initial round of the Delphi process, we requested that panel members rate a set of potential characteristics that would ultimately create the basis for the definition of a PCDH. The identification of the PCDH definition is the first stage of a four‐level framework to align PCDH characteristics with existing quality metrics, as well as identifying gaps for which no metrics currently exist (Table 2).

This preliminary set of characteristics was identified through literature reviews and feedback with selected national experts.19, 23 As a starting point for the PCDH definition, we adopted the AHRQ's PCMH definition, which includes the following characteristics: (a) comprehensive, (b) patient‐centered, (c) coordinated, (d) accessible, and focused on (e) quality and (f) safety.13 We added (g) family‐centered and (h) continuous as these characteristics were included in existing dental home definitions.5 Consequently, these eight characteristics were presented in the initial Delphi round for rating by the NAC.

Prior to the first round, we emailed the participants with the project overview, a background report, and instructions for participating in the Delphi process. The NAC members were asked, via a web‐based survey, to rate how essential each of the eight characteristics was to the definition of a PCDH. For each round, NAC members had 3 weeks to respond to the questionnaire, with an advance email notification and instructions followed by two reminders. Between each round, we sent the NAC members a report that provided the quantitative results of the previous round and a summary of open‐ended comments.

2.4. Rating scale and results analysis methodology

Participants rated each of the eight characteristics on a scale of 1 to 9, where 1 was “not essential” and 9 was “definitely essential.” The rating approach was adapted from the RAND Appropriateness Method,24 and similar rating scales have been used in health and dental care quality measure development.25, 26 The questionnaire instructions included guidance regarding the factors to consider in rating the essentiality of each characteristic, including that participants should rate each characteristic on its own merits and not relative to other characteristics (Table 1). Participants were encouraged to provide their rationale for each rating through open‐ended comments; comments were shared anonymously with group members to inform participant reflection between Delphi rounds.17, 27 In the first round, we also asked participants to identify any additional, conceptually distinct characteristics that they believed should be considered for inclusion in a PCDH definition.

Table 1.

Delphi survey rating criteria for developing characteristics of a patient‐centered dental home

In determining how essential a characteristic is, please consider whether the characteristic:

|

For each rated characteristic, we tabulated the response frequency for each rating scale number and calculated the median rating. Agreement was assessed using a measure of response dispersion described by the RAND Appropriateness Method, which compares the interpercentile range (IPR) with the IPR adjusted for symmetry (IPRAS).23 This approach measures dispersion of a distribution in order to identify disagreement among responses. We used an IPR of 30% through 70%, the range for which testing of this method found the best results.23 A rating was classified as having disagreement if the IPR was greater than the IPRAS.

Taking into account both the median score and extent of agreement, characteristics were determined to be: (a) essential when the median score was 7 through 9 without disagreement, (b) uncertain if the median score was 4 through 6 without disagreement or was any median score with disagreement, or (c) not essential if the median score was 1 through 3 without disagreement. Characteristics identified as essential or not essential without disagreement were deemed to have reached consensus and were not evaluated further in subsequent rounds. Only characteristics in the uncertain category were considered for further evaluation through subsequent Delphi processes. We allowed participants to propose new characteristics in the first round; characteristics proposed by 3 or more participants were then rated in subsequent rounds.

2.5. Number of rounds and stopping criteria

Numerous approaches can be used to determine when consensus has been reached, with little consistency in the literature, and many studies do not clearly define the stopping criteria.18, 28 However, respondent fatigue has been noted as an important consideration in determining the number of rounds, with most Delphi studies using two to four rounds.18, 22 We established that the Delphi process would require at least two rounds to reassess any characteristics rated as uncertain and to allow rating of additional characteristics proposed during the first round. We identified the following a priori stopping criteria: (a) when all characteristics were rated as essential or not essential without disagreement, or (b) when characteristics rated as uncertain or with disagreement acquired stable responses over two rounds, or (c) when the targeted maximum number of rounds has been met (3 for this project). The adopted approach combines a priori criteria to reduce the likelihood of arbitrary determinations of the stopping criterion but allows for flexibility in recognition of the significant qualitative aspect of the Delphi process.

2.6. Public comment

After finalizing the PCDH definition through the Delphi process, a report describing the development process, including the finalized PCDH definition, was posted online on March 15, 2016, for a 1‐month public comment period, with email dissemination to relevant listservs of key organizational stakeholders (e.g., Dental Public Health listserv, Dental Quality Alliance listserv, and DentaQuest listserv). The public comments were carefully reviewed, and key themes were identified and evaluated by the NAC through one additional Delphi round to finalize the definition.

3. RESULTS

Three rounds of the Delphi process were completed. Response rates to each round was 98% (n = 4), 96% (n = 53), and 89% (n = 49), respectively. All eight characteristics in the Round 1 survey received a median rating of 7‐9 without disagreement (Table 2); therefore, all eight characteristics were retained as part of the PCDH definition in subsequent rounds.

Table 2.

Four‐level framework for developing a standardized definition of a patient‐centered dental home

| Level | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Definition and characteristics | What characteristics should a PCDH have that will drive improvement in health care quality and outcomes? | Accessibility |

| Components | What are the conceptual components of each characteristic? | Timeliness |

| Measure concepts | What are the measurable elements of each component? | Short wait times for routine care |

| Specified measures | How can we use data to quantify the measure concepts? | Percent of patients who receive an appointment for routine care as soon as wanted |

The following six characteristics were suggested by three or more respondents during Round 1 and were included for rating in the Round 2 survey: prevention‐focused (n = 6), integrated (n = 4), affordable (n = 3), culturally competent (n = 3), health literacy‐focused (n = 3), and evidence‐based (n = 3). Round 2 surveying resulted in none of these six characteristics meeting the rating threshold for inclusion in the definition (Table 3). In Round 2, about 70% of respondents provided open‐ended comments with their ratings (Table 4). The largest proportion of comments for each of the six new characteristics indicated that the characteristic was already conceptually encompassed within one of the original eight characteristics and would be more appropriately considered as a component of an original characteristic rather than a unique characteristic. Based on these two Delphi rating rounds, a PCDH definition and report were developed for public comment.

Table 3.

Median ratings from Delphi survey Rounds 1 (n = 54) and 2 (n = 53) for developing characteristics of a patient‐centered dental home

| Characteristic | Median rating | Without disagreement? |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | ||

| Accessible | 9 | Y |

| Patient‐centered | 9 | Y |

| Coordinated | 8 | Y |

| Quality‐focused | 8 | Y |

| Safety‐focused | 8 | Y |

| Comprehensive | 7 | Y |

| Continuous | 7 | Y |

| Family‐centered | 7 | Y |

| Round 2 | ||

| Affordable | 6 | N |

| Evidence‐based | 6 | N |

| Prevention‐focused | 4.5 | N |

| Culturally competent | 4 | N |

| Integrated | 4 | N |

| Health literacy‐focused | 3 | N |

Table 4.

Qualitative results from Delphi survey Round 2 (n = 53) for 6 additional proposed characteristics from Round 1

| Characteristic | N (%) of respondents providing comment | Median rating among respondents providing comment | Direct quote illustrating theme | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Include as characteristic | Include as component | Uncertain/Ambivalent | |||

| Affordable | 35 (66) | 4 | “Due to the high level of dental un‐ and under‐insurance, high out‐of‐pocket costs, and survey results citing cost as a barrier to dental care, I think this merits separate consideration in the patient‐centered dental home.” | “I believe ‘affordable’ is a component of ‘accessible,’ but not a stand‐alone essential characteristic.” | “For so many, the reason they are not accessing dental care is affordability. This could either be a characteristic or added to the ‘accessible’ definition.” |

| Evidence‐based | 34 (64) | 3 | “Evidence‐based care is an essential component of the PCMH Model of Care that should be applied to dental care. It is distinct from ‘quality and safety.’” | “The current definition for ‘quality‐focused’ explicitly includes evidence‐based practice.” | “I feel this is an essential piece, but it could potentially be put under ‘quality and safety’ as a component.” |

| Prevention‐focused | 34 (64) | 3 | “This is more important than ‘comprehensive.’ Should include primary and secondary prevention.” | “Prevention is already included in the description of the ‘comprehensive’ characteristic.” | “Prevention could be considered part of ‘comprehensive,’ but having it as a separate characteristic adds greater emphasis to preventive services.” |

| Culturally competent | 40 (75) | 3 | N/A | “Understanding and respecting each patient's culture is clearly a component of ‘patient/family centered.’” | “Culturally competent oral health care is important. I believe that consideration of inclusion of the term in the definition warrants more discussion. It could be that some of the current essential characteristics already cover cultural competence.” |

| Integrated | 38 (72) | 3.5 | “Integrated care is a distinct and valuable characteristic of an ideal PCDH.” | “If the dental home is comprehensive, continuous, and coordinated, it will be ‘integrated.’” | “This is analogous to coordinated but goes one step further by implying the patient‐centered dental home is not a stand‐alone that works with other health components internally and externally but is an embedded part of the health‐care system.” |

| Health literacy‐focused | 37 (70) | 3 | “Health literacy is THE KEY COMPONENT of ALL health care!!!! This is the most critical paradigm that needs to be addressed.” | “This item is included under ‘patient/family‐centered.’ While very important, the focus is addressed in another characteristic within a context of patient‐centered care.” | “Not sure whether ‘patient‐centered’ and ‘quality‐focused’ characteristics capture this idea fully. Think it merits further discussion.” |

3.1. Public comment and Round 3

Eighteen sources, including individuals and national organizations, provided feedback for the proposed PCDH definition during the month‐long public comment period. Two themes emerged:

Greater clarity was needed to emphasize that part of the goal of the PCDH is to facilitate integration of dental care within health home models of care with applicability to a wide range of settings and populations.

Concerns were raised about circularity in using the term patient‐centered as a characteristic defining a patient‐centered dental home and whether the term person would be more encompassing than patient.

Consequently, two proposed changes to the PCDH definition were evaluated in a third Delphi round by the NAC:

Adding a clause to specify that the PCDH is part of a health home and includes populations of all ages, and

Changing the characteristic patient‐centered to person‐centered.

Results from the Round 3 Delphi survey indicated that the first proposed change met the criteria for inclusion (median rating = 7, without disagreement), whereas the second proposed change did not (median rating = 6, without disagreement). Due to predefined stopping criteria designed to minimize respondent fatigue and the “without disagreement” associated with the “uncertain” rating of the second proposed change, the decision was made to finalize the definition rather than administer a fourth survey round.

The PCDH definition was thus finalized as follows: “The patient‐centered dental home is a model of care that is accessible, comprehensive, continuous, coordinated, patient‐ and family‐centered, and focused on quality and safety as an integrated part of a health home for people throughout the life span.” Integration as part of a health home was incorporated to reinforce the growing recognition of the need to incorporate oral health into the concept of the broader health home. Throughout the life span reinforces that this model of care goes beyond pediatric populations (upon which most of the previous dental home efforts have focused) and incorporates all populations including adults, people with special health care needs of all ages, and adults in geriatric care.

4. DISCUSSION

This project successfully used a modified Delphi process with a large interdisciplinary group of national experts to develop a standardized definition of a PCDH model of care. The consensus‐based process determined the characteristics that the expert panel considered most important to coordinated, high‐quality oral health care, with these characteristics forming the basis for the PCDH definition. This definition is the foundational stage of our broader project goal to connect these characteristics to an accepted set of metrics to allow researchers and others to evaluate the quality of dental care from a patient‐centered perspective and to help dental care providers and network systems demonstrate and improve care coordination and quality in a manner similar to existing PCMH models.

Recruitment of a large and diverse national advisory committee (NAC) through a snowball sampling approach reflected our goal of ensuring that the final definition represented the perspectives not only of stakeholders within dentistry but also those outside of dentistry, such as medical care providers, health services researchers, accrediting organizations, health policy experts, and medical home experts. The high acceptance rate of experts and organizations who were invited to participate on the NAC, and their continued engagement to complete the Delphi process, underscores the understanding among a broad array of researchers, policy makers, accrediting bodies, health plans, and practitioner groups that there is both a void and a need for a standardized approach to define and measure patient‐centered dental care.

While we cannot guarantee that this definition of the PCDH will become generally accepted as the standard, one specific example of the perceived usefulness of this project is that several organizations that already had existing dental home evaluation metrics or an established accreditation process still elected to support this effort by participating on our national advisory committee as a way to improve the evidence base for their own activities. For NAC members from outside dentistry, the alignment of the PCDH development efforts with the PCMH was seen as a bridge on the path to improved understanding and integration, with the goal of realizing a comprehensive person‐centered health home that is encompassing of all primary care.

Next steps for this project are to use this definition as the first and foundational stage of a four‐level framework for full development of the PCDH model of care (Table 2). This four‐level framework is adapted from existing PCMH accreditation tools that connect conceptual elements to measurable indicators that can drive quality measurement and improvement. Using this framework, we will use the same modified Delphi process with NAC members to identify components that make up each of the characteristics of the PCDH. From there, measure concepts will be identified for each of the components of the PCDH model, ultimately leading to the identification or development of quantitative metrics for each measure concept.

As the next levels of the framework are developed, a key goal is to ensure multilevel usability of all aspects of the PCDH model (i.e., practice level and system level). This flexibility of the model will allow the components and metrics identified for each of the PCDH characteristics to be useful for evaluating the spectrum from individual dental practices to large group practices to Medicaid programs to the accreditation of care delivery networks. The combination of standardization and flexibility is intended to facilitate the ability to communicate between dentistry and the rest of the health care system.

Improved communication is critical because integrating oral health within overall health is paramount for improving population health. Recent developments in both the published literature and public policy make this the right time to move forward on bold, new integrated care delivery approaches. These developments include (a) increasing evidence about the linkages between oral and general health,29, 30, 31 (b) the opportunities for integration provided by delivery system models such as ACOs and other value‐based purchasing arrangements, (c) early examples of movement toward integrated or co‐located medical and dental delivery systems, and (d) the identification of potential cost savings through collaborative medical‐dental arrangements.32

ACOs and other value‐based purchasing arrangements may provide the greatest potential for the use of a PCDH model to assist with dental integration.33 As ACOs are incentivized to improve care coordination and reduce total cost of care for their members, ACOs could benefit from cost‐reduction activities such as more effectively linking patients to primary dental care settings and thereby avoiding costly preventable emergency department dental visits.34 One specific example of the value and potential use of the results of this project is that our project team was contacted by researchers who were developing an evaluation plan for a state Medicaid program interested in applying the PCDH model in a value‐based purchasing application focused on reducing avoidable dental‐related emergency department use.

There are barriers that currently prevent or hinder integration of medical and dental care, however. These include separate medical and dental electronic health record systems; lack of physical, geographical, and organizational alignment of medical and dental providers; and separate medical and dental insurance and financing systems.35, 36 For both dental health services research and cross‐system communication, a particular challenge has been the lack of consistent use and structured recording of diagnostic codes into clinical and administrative databases in dentistry.37 Diagnostic codes are standard data elements in medical databases but not in dental databases. Diagnostic codes are integral for measuring health outcomes and identifying patients who would most benefit from care coordination, including the type of care coordination needed. Until diagnostic codes are more consistently used in dentistry, some aspects of the PCDH may be considered aspirational. Conversely, having a PCDH model of care may also help promote progress in these areas by highlighting the importance of diagnostic codes in measure development and promoting the adoption of structural supports and processes of care that are critical to improving patient care and outcomes. The intent is that the final PCDH model be applicable to the current environment yet adaptable to a future environment in which integrated care systems are more prevalent.

5. CONCLUSION

This project developed the first standardized definition of a PCDH, which can serve as a framework to measure and improve the quality of dental care in a manner aligned with the PCMH. The interest and participation of a broad national advisory committee including organizations and experts in medicine, dentistry, quality measurement, and accrediting organizations highlight the need for standardization around patient‐centered dental care. A standardized, consensus‐based PCDH definition and associated measurement framework can facilitate the involvement of dental care in achieving the broader triple aim through a more integrated delivery system by aligning with the PCMH model of care but incorporating the nuances of dental financing and delivery.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The authors would like to thank the DentaQuest Foundation for their financial support of this project. We would also like to thank Brooke McInroy, survey research manager, the University of Iowa, Public Policy Center, for her assistance with the data collection aspects of the modified Delphi process. We would also like to thank Alyssa Perry for her assistance with editing and formatting the manuscript.

Damiano P, Reynolds J, Herndon JB, McKernan S, Kuthy R. The patient‐centered dental home: A standardized definition for quality assessment, improvement, and integration. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:446‐454. 10.1111/1475-6773.13067

REFERENCES

- 1. Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1473‐1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arend J, Tsang‐Quinn J, Levine C, Thomas D. The patient‐centered medical home: history, components, and review of the evidence. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79(4):433‐450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mertz EA. The dental‐medical divide. Health Aff. 2016;35(12):2168‐2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. The dental home: a primary care oral health concept. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(1):93‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Damiano PC, Reynolds JC, McKernan SC, Mani S, Kuthy RA. The Need for Defining a Patient‐Centered Dental Home Model in the Era of the Affordable Care Act. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, Public Policy Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ojha D, Aravamudhan K. Leading the dental quality movement: a Dental Quality Alliance perspective. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016;44(4):239‐244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute of Medicine . Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glurich I, Nycz G, Acharya A. Status update on translation of integrated primary dental‐medical care delivery for management of diabetic patients. Clin Med Res. 2017;15(1–2):21‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vest JR, Bolin JN, Miller TR, Gamm LD, Siegrist TE, Martinez LE. Medical homes: “where you stand on definitions depends on where you sit”. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(4):393‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gans DN. A Comparison of the National Patient‐Centered Medical Home Accreditation and Recognition Programs. Englewood, CO: Medical Group Management Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burton RA, Devers KJ, Berenson RA. Patient‐Centered Medical Home Recognition Tools: A Comparison of Ten Surveys’ Content and Operational Details. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, Health Policy Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Published 2016. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 14. Heisey‐Grove D, Patel V. National findings regarding health IT use and participation in health care delivery reform programs among office‐based physicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):130‐139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Standards and guidelines for NCQA's Patient‐Centered Medical Home (PCMH) [news release]. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2015. www.ncqa.org/Newsroom/NewsArchive/2015NewsArchive/NewsReleaseJuly12015.aspx. Accessed February 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Helmer‐Hirschberg O. Analysis of the Future: The Delphi Method. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008‐1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Day J, Bobeva M. A generic toolkit for the successful management of Delphi studies. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2005;3(2):103‐116. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodman LA. Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1961;32(1):148‐170. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(9):979‐983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qualtrics . 2016. Qualtrics (version 2016) statistical software. Provo, UT: Qualtrics. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mangione‐Smith R, Schiff J, Dougherty D. Identifying children's health care quality measures for Medicaid and CHIP: an evidence‐informed, publicly transparent expert process. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3 Suppl):S11‐S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herndon JB, Crall JJ, Aravamudhan K, et al. Developing and testing pediatric oral healthcare quality measures. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75(3):191‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brody RA, Byham‐Gray L, Touger‐Decker R, Passannante MR, O'Sullivan Maillet J. Identifying components of advanced‐level clinical nutrition practice: a Delphi study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):859‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two‐way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):26S‐31S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zoellner H. Dental infection and vascular disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37(3):181‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simpson TC, Weldon JC, Worthington HV, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(11):CD004714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nasseh K, Greenberg B, Vujicic M, Glick M. The effect of chairside chronic disease screenings by oral health professionals on health care costs. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):744‐750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fraze T, Colla C, Harris B, Vujicic M; Health Policy Institute . Early insights on dental care services in accountable care organizations. http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/ScienceandResearch/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0415_1.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 34. Colla CH, Stachowski C, Kundu S, Harris B, Kennedy G, Vujicic M; Health Policy Institute and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice . http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/ScienceandResearch/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0316_2.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 35. Returning the mouth to the body: integrating oral health and primary care. Washington, DC: Grantmakers in Health; 2012. http://www.gih.org/Events/EventDetail.cfm?ItemNumber=5211. Accessed March 2, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kalenderian E, Halamka J, Spallek H. An EHR with teeth. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):425‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kalenderian E, Tokede B, Ramoni R, et al. Dental clinical research: an illustration of the value of standardized diagnostic terms. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76(2):152‐156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials