Abstract

We present a unique case of endophthalmitis with Staphylococcus lugdunensis following dexamethasone intravitreal implant for branch retinal vein occlusion associated with cystoid macular edema. Patient did not show favorable clinical response after vitrectomy and intravitreal antibiotics; so, we decided to repeat vitrectomy, remove the steroid implant and fill the eye with silicon oil, and repeat intravitreal vancomycin. Vision has improved from hand movements at presentation to counting fingers at 1.5 m after second vitrectomy and final visual acuity 3 months later after silicon oil removal was 6/36.

Keywords: Dexamethasone implant, endophthalmitis, silicon oil, Staphylococcus lugdunensis

Ozurdex® (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA) is a 0.7-mg intravitreal biodegradable steroid (dexamethasone) implant with sustained release for up to 6 months. The implant is inserted into the vitreous cavity using a 22-ga applicator and is one of the treatment modalities for retinal vein occlusion associated with cystoid macular edema.

Case Report

We present the case of a 72-year-old patient with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) who developed endophthalmitis after an Ozurdex® intravitreal injection. The patient had been treated regularly with 11 ranibizumab (Lucentis®) and 5 dexamethasone (Ozurdex®) intravitreal injections since September 2014 when he was first diagnosed with right eye BRVO. In April 2018, patient received the sixth Ozurdex® injection without any immediate complications. The procedure was performed in theater with topical and subconjunctival anesthesia under aseptic conditions and chloramphenicol 0.5% drops were instilled at the end. Chloramphenicol 0.5% drops were also given to take at home 4 times a day for 5 days. Preinjection best-corrected visual acuity right eye was 6/36.

Patient presented 4 days later with painful right eye with counting fingers vision. Anterior segment examination did not show any inflammation in anterior chamber, right eye intraocular pressure was 38 mmHg, and fundus examination revealed vitreous haze. Patient with bilateral ocular hypertension, already under topical medication: latanoprost, timolol, and brimonidine, was started also on oral acetazolamide 250 mg 4 times/day as the increase in pressure was thought to be caused by the dexamethasone implant. As no signs of anterior segment inflammation, vitreous haze was thought to be subsequent to a small resolving vitreous hemorrhage at the time of the Ozurdex® injection.

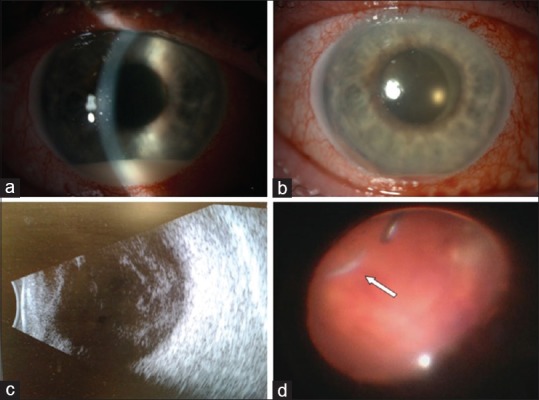

The following day when patient was seen, a clinical diagnosis of endophthalmitis was made: he had developed 1.4 mm hypopyon without fundus view, B-scan ultrasound examination revealed extensive vitreous debris, and the team decided to perform vitreous biopsy and vitrectomy as soon as possible on the same day. Meanwhile waiting for surgery, the hypopyon was seen to be rapidly growing to 1.8 mm when the slit-lamp photo was taken [Fig. 1a]. During vitrectomy, a very thick vitreous was observed and the dexamathasone implant was surrounded by fibrous reaction. We decided to leave the implant in the eye and to perform very meticulous cleaning around it. At the end of the procedure, intravitreal vancomycin 1 mg and ceftazidime 2 mg were injected. Anterior chamber washout was also performed and intracameral cefuroxim was injected. Patient was also started on oral levofloxacin 500 mg once a day and 2 hourly topical levofloxacin and prednisolone 1% drops.

Figure 1.

(a) Slit-lamp examination at presentation: conjunctival injection, 1.8 mm hypopyon; (b) slit-lamp examination 2 days after vitrectomy and intravitreal antibiotics: conjunctival injection, 0.4 mm hemorrhagic hypopyon; (c) ultrasound showing extensive vitreous inflammatory reaction; and (d) intraocular image with dexamethasone implant (arrow) mushy appearance before removal by cutter

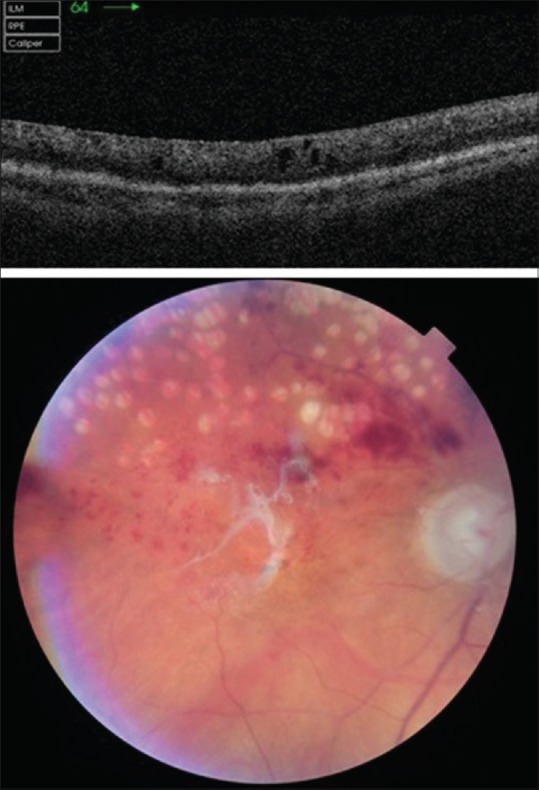

First day postvitrectomy, anterior segment examination showed a 2-mm hemorrhagic hypopion which had decreased by next day to 0.4 mm [Fig. 1b]. Vitreous biopsy was cultured on conventional media and results showed coagulase-negative Staphylococcus sensitive to ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, and flucloxacillin. Staphylococcus lugdunensis was identified using matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry technique (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight). Third-day postvitrectomy, anterior segment examination showed remission of hypopyon, but B-scan ultrasound examination revealed extensive vitreous debris building up [Fig. 1c], so the team decided to perform revision vitrectomy with removal of the dexamathasone implant (which no longer had a firm appearance) and to fill the eye with silicon oil (2000 cs) and repeat the 1 mg vancomycin intravitreal injection [Fig. 1d]. Vancomycin sensitivity was not tested, but because current protocols recommend vancomycin for all gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis, we decided to repeat the antibiotic injection. Two days after second surgery, patient was able to count fingers at 1.5 m. At 3 weeks review, eye remained comfortable, intraocular pressure controlled with topical medication, and vision was counting fingers at 1.5 m [Fig. 2]; 3 months later, we have performed silicon oil removal and ranibizumab intravitreal injection, final vision becoming 6/36, the same as before the endophthalmitis episode.

Figure 2.

Topcon OCT at 3 weeks review postvitrectomy showing small intraretinal fluid pockets; fundus photo–silicon oil interface reflex, superior branch retinal vein occlusion with previous sectorial panretinal photocoagulation laser scars

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this is the first described case of S. lugdunensis endophthalmitis following Ozurdex® injection.

Endophthalmitis appears to be a rare event as proven by Stem et al. who has described 5 cases of endophthalmitis in 3593 Ozurdex® injections’ database. Four out of five cases were culture positive for Staphylococcus species (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus schleiferi). Ozurdex® implant was removed only in one of the five endophthalmitis cases, which brings up an important question as to remove or not the implant and if that would change the course of the treatment of endophthalmitis.[1]

Coagulase-negative staphylococci are among the most frequent constituents of normal skin flora and can be common contaminants in clinical specimens, as well as agents of infection. The most common suspected source of endophthalmitis is normal conjunctival flora for Staphylococcus species or aerosolized droplet contamination from the oropharyngeal tract for streptococcus species.[2] The majority of S. lugdunensis endophthalmitis reported cases are characterized by an insidious onset – an average of 1 week after intraocular procedure: cataract surgery, intravitreal injections, or open globe repairs.[3,4] There are also S. lugdunensis endophthalmitis cases following intravitreal injections with early onset as presented by Murad-Kejbou et al. with aggressive course of disease leading to poor visual outcomes ranging from 6/30 to hand movements.[5] S. aureus and S. lugdunensis have similar clinical infection course and patients appear to have greater hypopyon height as compared to other coagulase-negative Staphylococcus endophthalmitis cases.[6] Our endophthalmitis case had similar presentation to the above description with insidious onset and rapid growing hypopyon once the endophthalmitis was in full bloom [Fig. 1a].

The particularity of this case resides in the treatment approach we have chosen. We have not removed the implant initially, though many case reports highlighted the importance of Ozurdex® removal.[7,8,9] We based our decision of not removing the implant on Stem et al. study which showed that is not necessary in all cases to perform vitrectomy or to remove the dexamethasone implant.[1] Three days postvitrectomy, ultrasound proved worsening of vitritis [Fig. 1c], so we took the decision to do revision vitrectomy with removal of implant which at that time had a mushy appearance and was eaten easily by the cutter [Fig. 1d].

Chiquet et al. has shown that postcataract surgery S. lugdunensis endophthalmitis cases are characterized by a worse final functional prognosis and have a higher risk of postvitrectomy retinal detachment compared with other coagulase-negative Staphylococcus endophthalmitis cases as the organism causes more necrozis and thereby retinal detachment.[3] Silicon oil is known to have antibacterial properties and several studies have shown the benefit of silicon oil in endophthalmitis cases without retinal detachment.[10] Taking in consideration the above facts, filling the eye with silicon oil in our case was a logical approach and the final visual acuity of 6/36 after silicon oil removal was more than we have hoped for.

Conclusion

In conclusion, primary removal of steroid implant and filling the eye with silicon oil appears to be a good approach to any severe endophthalmitis case following Ozurdex® intravitreal injection, especially if infection with S. lugdunensis. Final visual acuity of 6/36 in our case was better than all other Ozurdex® endophthalmitis cases from international literature which had a maximum gain in vision of 6/60.[1,2,7,8]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed equally to work. Each author participated in manuscript preparation and review. All authors believe that the manuscript represents honest work and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole from inception to the published article.

References

- 1.Stem MS, Todorich B, Yonekawa Y, Capone A, Jr, Williams GA, Ruby AJ. Incidence and visual outcomes of culture-proven endophthalmitis following dexamethasone intravitreal implant. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:379–82. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.5883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchino T, Vela JI, Bassaganyas F, Sánchez S, Buil JA. Acute-onset endophthalmitis caused by alloiococcus otitidis following a dexamethasone intravitreal implant. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:37–41. doi: 10.1159/000348809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garoon RB, Miller D, Flynn HW., Jr Acute-onset endophthalmitis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2017;9:28–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiquet C, Pechinot A, Creuzot-Garcher C, Benito Y, Croize J, Boisset S, et al. FRIENDS group. Acute postoperative endophthalmitis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1673–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02499-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murad-Kejbou S, Kashani AH, Capone A, Jr, Ruby A. Staphylococcus lugdunensis endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection: A case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2014;8:41–4. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182a85a4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornut PL, Thuret G, Creuzot-Garcher C, Maurin M, Pechinot A, Bron A, et al. FRIENDS group. Relationship between baseline clinical data and microbiologic spectrum in 100 patients with acute postcataract endophthalmitis. Retina. 2012;32:549–57. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182205996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahalingam P, Topiwalla TT, Ganesan G. Drug-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal endophthalmitis following dexamethasone intravitreal implant. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:634–6. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_810_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goel N. Acute bacterial endophthalmitis following intravitreal dexamethasone implant: A case report and review of literature. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2017;31:51–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arıkan Yorgun M, Mutlu M, Toklu Y, Cakmak HB, Caǧıl N. Suspected bacterial endophthalmitis following sustained-release dexamethasone intravitreal implant: A case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014;28:275–7. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2014.28.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinarci EY, Yesilirmak N, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. The results of pars plana vitrectomy and silicone oil tamponade for endophthalmitis after intravitreal injections. Int Ophthalmol. 2013;33:361–5. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]